Abstract

Significance:

An estimated 700 million people globally suffer from chronic kidney disease (CKD). In addition to increasing cardiovascular disease risk, CKD is a catabolic disease that results in a loss of muscle mass and function, which are strongly associated with mortality and a reduced quality of life. Despite the importance of muscle health and function, there are no treatments available to prevent or attenuate the myopathy associated with CKD.

Recent Advances:

Recent studies have begun to unravel the changes in mitochondrial and redox homeostasis within skeletal muscle during CKD. Impairments in mitochondrial metabolism, characterized by reduced oxidative phosphorylation, are found in both rodents and patients with CKD. Associated with aberrant mitochondrial function, clinical and preclinical findings have documented signs of oxidative stress, although the molecular source and species are ill-defined.

Critical Issues:

First, we review the pathobiology of CKD and its associated myopathy, and we review muscle cell bioenergetics and redox biology. Second, we discuss evidence from clinical and preclinical studies that have implicated the involvement of mitochondrial and redox alterations in CKD-associated myopathy and review the underlying mechanisms reported. Third, we discuss gaps in knowledge related to mitochondrial and redox alterations on muscle health and function in CKD.

Future Directions:

Despite what has been learned, effective treatments to improve muscle health in CKD remain elusive. Further studies are needed to uncover the complex mitochondrial and redox alterations, including post-transcriptional protein alterations, in patients with CKD and how these changes interact with known or unknown catabolic pathways contributing to poor muscle health and function. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 38, 318–337.

Keywords: skeletal muscle, cachexia, uremia, renal, metabolism

Introduction

Recent epidemiological studies have estimated that ∼700 million people worldwide suffer from chronic kidney disease (CKD), a global prevalence that equates to roughly 9% of the population (Glassock et al, 2017). CKD is defined by a functional deficit of the kidneys, typically measured by glomerular filtration rate, that lasts for more than 3 months (Levey et al, 2007). Because of the gradual decline in kidney function, symptoms of CKD often remain undetected until it reaches the advanced stages of the disease where there are limited treatment options (dialysis or transplantation) (Kopyt, 2006; Provenzano et al, 2019); thus, CKD is often described as a “silent killer.”

In addition to aging and an unhealthy lifestyle, diabetes and hypertension are among the leading factors contributing to kidney damage (Levey et al, 2007). For instance, hyperglycemia stimulates mesangial cell growth and accumulation of glycosylated proteins in the glomerular basement membrane, which contribute to glomerulosclerosis (Ohshiro et al, 2005; Pyram et al, 2012; Thomas et al, 2005). Chronic high blood pressure stimulates afferent wall thickening and endothelial dysfunction, which are linked with poor kidney capillary networking and ischemic injury on the glomeruli and tubulointerstitial structures (Mennuni et al, 2014; Neuhofer and Pittrow, 2006).

Although the primary role of the kidneys is to remove the waste products and regulate body fluid, CKD dramatically increases the incidence of vascular dysfunction, dyslipidemia, anemia, and bone metabolic disorder (Thomas et al, 2008). Notably, the extensive and serious impact of these complications on the cardiovascular and neuromuscular systems are closely associated with high risks of morbidity and mortality in patients with CKD (James et al, 2018; Thomas et al, 2008). As the disease progresses to the most severe manifestation of CKD known as end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), treatment requires either organ transplant or renal replacement therapies such as hemodialysis.

Unfortunately, the patients receiving hemodialysis have significantly higher mortality rates than the general population (Bello et al, 2022; Nordio et al, 2012). Accumulating evidence from human and animal studies indicates that, in addition to cardiovascular disease (reviewed in Patel et al, 2022; Ravid et al, 2021), CKD patients suffer from progressively debilitating neuromuscular complications (muscle wasting, weakness, fatigue, and exercise intolerance) that are associated with poor clinical outcomes and patient quality of life (Abramowitz et al, 2018; Androga et al, 2017; Hellberg et al, 2017; John et al, 2013; Kestenbaum et al, 2020; Stenvinkel et al, 2004; Wang et al, 2022; Watson et al, 2020; Zhou et al, 2018).

Emerging evidence suggests that the CKD milieu potentiates metabolic derangements and oxidative stress across numerous tissues/organs, contributing to disease progression and its complications. This review is focused on the role of mitochondrial and redox alterations in the debilitating skeletal myopathy associated with CKD.

The Myopathic Phenotype of the CKD Patient

Patients with CKD experience a progressive loss of muscle mass and strength, increasing fatigability, exercise intolerance, and impaired tissue regeneration and these phenotypic consequences become severe in patients with ESKD (Ikizler et al, 2002; Lam and Jassal, 2015; Rao et al, 2018; Roshanravan and Patel, 2019; Schardong et al, 2018; Takemura et al, 2020). Symptoms of fatigue are commonly reported among patients with CKD, with an estimated 70% of patients suffering from this debilitating symptom that diminishes quality of life and is strongly linked to health outcomes (Gregg et al, 2021). Undoubtedly, fatigue is a complex symptom stemming from multiple systemic effects of poor renal function. In this regard, cardiovascular alterations in CKD such as endothelial dysfunction and vascular calcification coupled with anemia dimmish convective oxygen delivery to working skeletal muscles (Schiffrin et al, 2007).

In addition, CKD is a catabolic disease that results in loss of muscle mass and diminished function, which has been strongly associated with mortality (Gracia-Iguacel et al, 2013). It has been established that muscle catabolism, but not malnutrition, is primarily responsible for this increased mortality risk in CKD (Stenvinkel et al, 2004). Over the past several decades, multiple catabolic pathways including the ubiquitin proteasome system, caspase 3, autophagy, myostatin, and inflammation have been demonstrated to be active in skeletal muscle of animals and patients with CKD. In addition, key anabolic pathways, such as the insulin/IGF-1 and mTOR, are diminished in CKD muscle, further contributing to the catabolic state (Wang and Mitch, 2014; Wang et al, 2022).

Unfortunately, hemodialysis treatments do not correct these catabolic conditions, but instead accelerate muscle protein degradation (Ikizler et al, 2002). On the other hand, prospective and retrospective observational studies have reported that kidney transplantation promotes increases in both muscle and total body mass in ESKD patients (Adachi et al, 2020; Han et al, 2012; Kosoku et al, 2022; Nielens et al, 2001). However, it is important to note that the incidence of ESKD far outpaces the available kidney donor pool, leading to lengthy transplant waiting times and only a small fraction of the patient population receiving a matching organ (Andre et al, 2014; Wolfe et al, 1999).

Beyond the cardiovascular and skeletal muscle effects, CKD has also been linked to peripheral nerve impairments (Doshi et al, 2020) that likely contribute to the weakness, fatigue, and exercise intolerance phenotypes. As a result of these pathologies, the prevalence of frailty (or pre-frailty) is high in CKD (Mei et al, 2021; Reese et al, 2013) and is closely linked to poor clinical outcomes and increased risks of morbidity and mortality rate in CKD patients (Jhamb and Weiner, 2014; Lam and Jassal, 2015; Roshanravan and Patel, 2019; Roshanravan et al, 2017; Schardong et al, 2018).

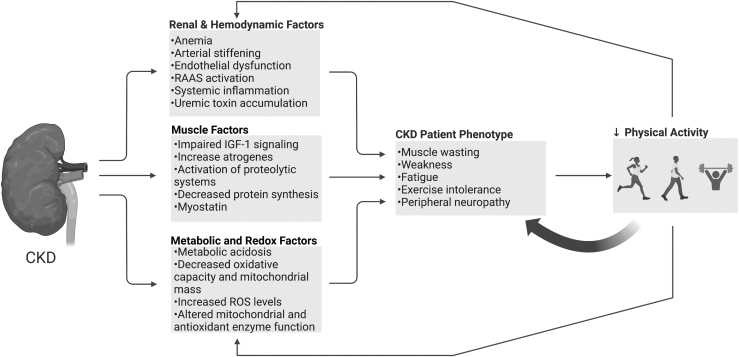

Unfortunately, this myopathic phenotype cultivates a sedentary lifestyle with reduced physical activity levels (Bruinius et al, 2022; Schrauben et al, 2022) that create a vicious cycle, further amplifying the CKD myopathy (Fig. 1). An active area of research is targeted toward developing nutritional and lifestyle (i.e., exercise) interventions that can counteract the systemic, cardiovascular, and neuromuscular defects in CKD (Manfredini et al, 2017; Roshanravan et al, 2017; Wilkinson et al, 2020). However, an incomplete understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the CKD-associated skeletal myopathy is a barrier that hinders the development of effective interventions. Later, we review and discuss evidence suggesting that impaired muscle mitochondrial function and oxidative stress play important roles in the myopathy of CKD (Chalupsky et al, 2021; Gamboa et al, 2020; Kestenbaum et al, 2020).

FIG. 1.

Mechanisms involved in the myopathic phenotype of the CKD patient. CKD patients commonly suffering from a debilitating myopathic phenotype consisting of muscle weakness, fatigue, and exercise intolerance. Impaired renal function drives pathological adaptations systemically and locally in skeletal muscle that contribute to the development and progression of this myopathy. Collectively, these pathological alterations contribute to low physical activity levels and a sedentary lifestyle, which further exacerbate the myopathy symptoms. CKD, chronic kidney disease. Illustration created using BioRender.com

Review of Muscle Cell Bioenergetics and Redox Homeostasis

Before embarking on a discussion of the role of mitochondrial and redox alterations in the CKD-associated myopathy, a review of muscle cell bioenergetics and redox homeostasis is necessary.

Overview of skeletal muscle energy transduction

Skeletal muscle cells are somewhat unique in that they have relatively low levels of energy demand at rest, but this demand increases tremendously with contractile activity/movement. Thus, there must be both a constant transformation of energy from the fuel we consume (carbohydrates, fats, proteins) to a more biologically accessible form of currency (i.e., adenosine triphosphate, ATP), as well as a reserve capacity to meet the demands of muscular activity. To do this, cells are equipped with biochemical pathways that enable energy production through both anaerobic (glycolysis) and aerobic processes (oxidative phosphorylation [OXPHOS] within the mitochondria).

It is well established that the primary energy intermediate that supports most cellular functions (contraction and ion transport) is ATP (Cain and Davies, 1962; Cain et al, 1962). However, the concentration of ATP in muscle rarely changes except during extreme exhaustion (Balaban, 2006; Glancy and Balaban, 2021). Generally during an increase in muscular work, a modest decrease in phosphocreatine (PCr), increase in inorganic phosphate (Pi), and increase in adenosine diphosphate (ADP) occur, which results in a modest decrease in the free energy for ATP hydrolysis (ΔGATP) (Funk et al, 1989; Glancy and Balaban, 2021).

The PCr and creatine kinase (CK) reaction can transiently maintain ATP supply using PCr to sustain muscle work for several seconds. However, ATP must be regenerated via a combination of glycolysis and OXPHOS to sustain continuous muscular work. Non-aerobic production of ATP and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) in glycolysis provides a source of potential energy for cellular work, whereas the oxidative metabolism of its end-product (pyruvate) within the mitochondria has a greater capacity for ATP generation. Therefore, skeletal muscle contraction relies heavily on efficient mitochondrial energy transduction.

In 1961, Peter Mitchell published a hypothesis on cellular bioenergetic transformation that he termed the “chemiosmotic theory of oxidative phosphorylation” (Mitchell, 1961). The basis of his hypothesis was the production of a proton gradient (H+) across an energy conserving membrane that could be utilized to drive the coupling of H+ translocation and phosphorylation of ADP to ATP (Mitchell, 1961). As depicted in Figure 2, subsequent research has proved that mitochondrial energy transduction includes a series interconnected metabolic reactions that collectively transform potential energy derived from fuel we consume to the ΔGATP through this chemiosmotic process.

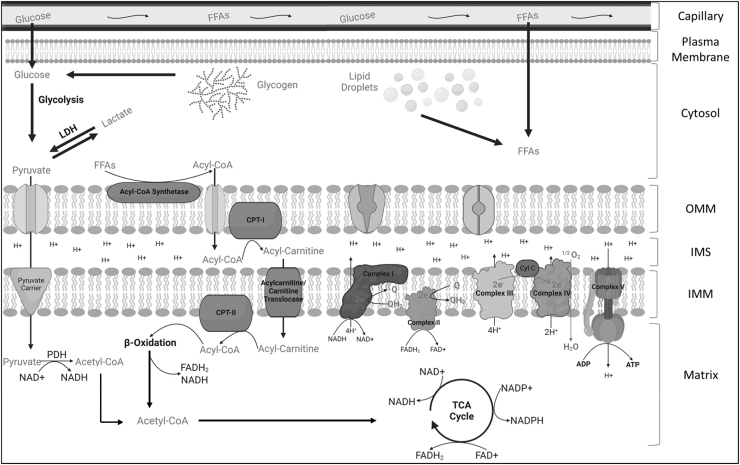

FIG. 2.

An overview of mitochondrial energy transduction. In skeletal muscle, the mitochondrion plays a crucial role in converting the fuel consumed (glucose, fats, proteins) into a useable energy source (ATP) that is necessary to sustain the activities of the myofiber. Through a series of biochemical redox reactions, electrons are transferred from carbon fuels into the ETS via electron carriers (NAD+ and FAD+). The movement of electrons through the ETS powers the translocation of protons from the matrix to the IMS, creating the proton motive force that subsequently drives ATP synthesis. ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CoA, coenzyme A; CPT, carnitine palmitoyltransferase; Cyt C, cytochrome c; ETS, electron transport system; FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide; FFAs, free fatty acids; H+, proton; IMM, inner mitochondrial membrane; IMS, intermembrane space; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; OMM, outer mitochondrial membrane; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; TCA, tricarboxylic acid. Illustration created using BioRender.com

Pyruvate and free fatty acids (FFAs) can be transported across the mitochondrial membranes via transporter proteins that mediate electroneutral or electrogenic ion transfer as potential substrates for β-oxidation and the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle). Dehydrogenase enzymes within the mitochondrial matrix function to transfer hydrogens and electrons from carbon substrates to oxidized electron carriers such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) or flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD+). This generation of a redox potential serves two main purposes: (1) to provide electrons to the electron transport system (ETS) that are embedded within the inner mitochondrial membrane (NADH/FADH2), and (2) to provide reducing power to support antioxidant systems (NADPH).

The ETS is made up of four respiratory multi-subunit enzymes (Complex I—NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase, Complex II—succinate dehydrogenase, Complex III—ubiquinone cytochrome C oxidoreductase, and Complex IV—cytochrome C oxidase) that are organized based on their reduction potentials. For instance, starting with a highly negative reduction potential (indicating species with high tendency to donate electrons) such as NADH, the reduction potential progressively becomes more positive as electrons pass through complexes I–IV where O2 serves as the final electron acceptor, ultimately reducing 1/2 O2 to H2O.

In complexes I, III, and IV, the change in reduction potential across the enzyme provides enough potential energy to drive the translocation of H+ from the mitochondrial matrix to the inner membrane space. The translocation of H+ creates the proton gradient consisting of both a concentration (ΔpH) and an electrical membrane potential (ΔΨ). Together, ΔpH and ΔΨ comprise the total proton motive force (Δp) that is subsequently used to drive the phosphorylation of ADP to ATP as protons are moved back into the matrix through the ATP synthase (complex V) (Fisher-Wellman and Neufer, 2012).

To better understand the regulation of cellular energy balance and bioenergetic components related to redox signaling, several intrinsically programmed features of mitochondria must be considered. To start, the transfer of electrons through the ETS occurs automatically. This refers to the natural tendency of electron carriers (NADH and FADH2) to donate their electrons to the ETS with a subsequent flow of electrons down the reduction potential to the final electron acceptor, O2.

Because electron flow is coupled to proton translocation within the ETS, an oversupply of fuel (i.e., electrons) causes the Δp and ΔΨ to build up, resulting in a “back pressure” that constrains the ETS enzyme activity and thus regulates the rate of O2 consumption. Importantly, the mitochondrial inner membrane is inherently “leaky” to protons and thus, never reaches “static equilibrium” where the redox potential counterbalances the high ΔΨ produced and electron flow comes to a halt (Fisher-Wellman and Neufer, 2012).

Proton leak allows the system to work at a basal rate allowing continuous electron flow and partially determines the basal O2 consumption. The Δp is used to convert ADP to ATP by powering the ATP synthase enzyme that drives the displacement of the ATP hydrolysis reaction far from equilibrium (Fisher-Wellman et al, 2018; Glancy et al, 2015; Nicholls and Ferguson, 2013; Schmidt et al, 2021). Based on these features, the rate of oxygen consumption is regulated via a “pull” mechanism, not a “push,” and that proton conductance across the mitochondrial inner membrane regulates the rate of electron flow, demand for reducing equivalents, an ultimately substrate uptake and flux through catabolic pathways (Fisher-Wellman and Neufer, 2012).

In other words, the greater the energy demand, the greater the rate of fuel catabolism and OXPHOS. Importantly, because of the interconnected nature of mitochondrial energy transformation, aberrant function of any step (fuel supply and transport, matrix dehydrogenase, ETS, ATP synthase) can manifest as impaired OXPHOS and potentially produce an energetic ‘crises. Further to this, oversupply of fuel (electrons) coupled with impaired enzyme function can manifest as the electron leak required to drive oxidative stress conditions as discussed below.

Species and sources of reactive oxygen species

The study of redox biology in skeletal muscle has made major headway since the discovery of free radicals in biological processes in 1954 (Commoner et al, 1954). Currently, oxidative stress is critically defined as a disturbance in the homeostatic balance between the production and removal of reactive oxygen species (ROS)/reactive nitrogen species (RNS), resulting in “macromolecular oxidative damage along with a disruption of redox signaling and control” (Azzi et al, 2004; Jones, 2006; Powers and Jackson, 2008).

ROS is the general term used to describe O2-derived radicals, whereas RNS refers to nitrogen-derived radicals. Forms of ROS/RNS are produced during normal cellular metabolism and can be formed by the process of either losing or gaining electrons (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 2007; Powers and Jackson, 2008). The primary radical species produced in cells include superoxide (O2•−) and nitric oxide (NO•) (Andrade et al, 1998; Powers and Jackson, 2008; Reid et al, 1992). O2•− is formed as an intermediate byproduct of biochemical reactions intracellularly and extracellularly from various sources and can undergo oxidation/reduction reactions with biological components within the cell. O2•− is negatively charged, membrane impermeable, and relatively unreactive compared with other radicals despite its namesake.

Under physiological conditions, O2•− is rapidly converted to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) spontaneously or catalyzed by superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzymes. Moreover, the rate constant at which O2•− oxidizes thiols is quite slow nearing 103 M−1 s−1, whereas the rate constant at which O2•− is reduced to H2O2 by SOD is >109 M−1 s−1 (Fisher-Wellman and Neufer, 2012; Fridovich, 1995). Although H2O2 is a more stable molecule, H2O2 is membrane permeable and can diffuse to other compartments within the cell, and at high levels is toxic to cells (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 2007; Powers and Jackson, 2008; Powers et al, 2011).

H2O2 toxicity stems from the ability to undergo chemical reactions with transition metals (iron [Fe2+] or copper [Cu1+]), resulting in the highly reactive hydroxyl radical (OH•−), which possesses a strong oxidizing potential and is highly reactive (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 2007; Powers and Jackson, 2008). Under pathological circumstances, O2•−, H2O2, and OH•− can react with proteins, lipids, and DNA (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 2007). NO• is synthesized from the amino acid L-arginine by the enzyme nitric oxide synthase (NOS). Three isoforms have been identified: (1) neuronal (NOS1), (2) endothelial (NOS3), and (3) inducible NOS (NOS2), and all isoforms convert L-arginine into NO• and L-citrulline utilizing NADPH.

NO• is a weak reducing agent; however, in the presence of O2•−, peroxynitrite (ONOO−), a highly reactive free radical, can be produced. Formation of ONOO− can lead to oxidation of thiol groups, DNA oxidation, and nitration of proteins (Powers and Jackson, 2008; Powers et al, 2011). There are numerous sources of ROS/RNS, including membrane-bound NADPH-dependent oxidases (NOXs), xanthine oxidase (XO), cytochrome p450 enzymes (CYPs), monoamine oxidases (MAOs), and several mitochondrial enzymes. For the scope of this review, we will briefly discuss these major sites involved in radical formation in skeletal muscle.

Mitochondrial sources

Historically, it was believed that 1%–4% of O2 consumed during mitochondrial respiration underwent a one-electron reduction, resulting in the generation of O2•− (Boveris and Chance, 1973; Jackson et al, 2007; Loschen et al, 1974). This estimation was based on the maximum rate of O2•− production from complex III of the ETS in the presence of antimycin A (AMA) and saturating substrates (Brand, 2010). Brand and colleagues later reassessed this estimation of ROS production from mitochondria, indicating an upper estimate of ∼0.15% using palmitoyl carnitine, a fatty acid, as fuel (St-Pierre et al, 2002).

Thus far, 11 sites within the mitochondrion have been identified to produce ROS directly (Bleier et al, 2015; Brand, 2010; Brand and Nicholls, 2011; Fisher-Wellman and Neufer, 2012; Quinlan et al, 2013; St-Pierre et al, 2002; Tahara et al, 2009; Wong et al, 2017). These sites include respiratory complexes I (two sites), complex II, III, and IV within the ETS, 2-oxoacid dehydrogenase complexes (2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, pyruvate dehydrogenase, and branched chain 2-oxoacid dehydrogenase), glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH), β-oxidation (electron transferring flavoprotein Q oxidoreductase), and dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH). Complex I and III of the ETS are the sites with the highest capacity for ROS production within mitochondria.

In complex I, NADH produced by matrix dehydrogenases provides electrons to the redox centers flavin mononucleotide (FMN), 8-Fe-S clusters, and ubiquinone (Q). When the flavin site of complex I is fully reduced (IF site), as in the presence of a complex I inhibitor (blocking the Q binding site), site IF dominates O2•− production. However, under physiological conditions, site IF is relatively oxidized and rather limited in its rate of producing O2•−. The quinone binding site of Complex I (site IQ) can produce a greater amount of O2•− compared with the IF site. Reverse electron flow from the oxidation of substrates succinate or glycerol-3-phosphate, which occurs in conditions such as ischemia-reperfusion, can drive electrons thermodynamically uphill hyper-reducing the IQ site fostering electron leak.

Complex III contains cytochromes b566, b562, c1, and Rieske Fe-S center, and quinones at centers “i” and “o” (Zhang et al, 2000). When electron transfer is hindered from b566 to the quinone at center i, this can cause a buildup of semiquinone at center o that can readily reduce O2 to O2•− (Boveris and Chance, 1973; Cadenas et al, 1977; Cape et al, 2007; Turrens et al, 1985). The ROS production from complex II is considered negligible relative to complex I and III because the enzyme suppresses formation of radical in the flavin active site.

The 2-Oxoacid dehydrogenase complexes have more recently been described to play a role in O2•− formation too. These sites contain the redox active flavin that can reduce O2 to O2•− or H2O2. Site GQ of the mitochondrial G3PDH also feeds reducing equivalents from cytosolic lipid and carbohydrate metabolism to Q. It generates mostly O2•− at its ubiquinone binding site. Lastly, site EF of the electron transferring flavoprotein ubiquinone oxidoreductase system transfers reducing equivalents from β-oxidation and other pathways to the Q-pool.

Further evaluation of sites of radical formation and its contribution to redox signaling are underway and essential for a full comprehensive understanding of the physiological roles and potential pathological consequences of mitochondrial ROS.

The MAO family (MAO A and B) members are enzymes localized to the outer mitochondrial membrane responsible for the oxidative deamination of endogenous and exogenous monoamines (catecholamines and other biogenic amines). The MAOs employ a FAD cofactor to catalyze the deamination of monoamines (i.e., norepinephrine and dopamine) to aldehydes while producing H2O2 concomitantly (Maggiorani et al, 2017; Manoli et al, 2005). The two isoforms are distinguished by their affinity for substrates and sensitivity to inhibitors (Youdim et al, 1972). The MAOs have recently gained notoriety as relevant sources of redox signaling and homeostasis in skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle, specifically in pathological occurrences such as muscle denervation, type 2 diabetes, and aging (Murgia et al, 2017; Pollock et al, 2017; Scalabrin et al, 2019; Youdim et al, 1972).

For example, the reactive aldehydes produced by MAO were found to modify cardiac mitochondrial proteins, contributing to the suppression of mitochondrial ATP production in diabetes patients (Nelson et al, 2021). Although two prominent risk factors for CKD, diabetes and hypertension, are associated with dysregulated catecholamines, the contribution of MAO to the skeletal myopathy in CKD has not been explored to date.

Membrane-bound NOXs

The NOX enzymes are a unique subset of membrane-bound enzymes in multiple cell types, with its only known function to produce ROS. The NOXs were first characterized in skeletal muscle in 2002 (Ferreira and Laitano, 2016; Javeshghani et al, 2002), and have emerged as a major source of ROS in skeletal muscle cells. Five NOX isoforms have been described (NOX1–5); however, only NOX2 and NOX4 are believed to contribute significantly to redox signaling in skeletal muscle (NOX1 has been described to be upregulated in differentiating myotubes, but a physiological role for NOX1 remains to be known) (Ferreira and Laitano, 2016; Lambeth, 2004).

NOX2 and NOX4 are membrane-bound enzymes that utilize NAD(P)H to catalyze the conversion of O2 to O2•−. NOX2 is localized to the sarcoplasmic membrane and the t-tubules and produces O2•− extracellularly, which is then converted to H2O2 via SOD3 and can diffuse intracellularly to exert its redox signaling effects (Ferreira and Laitano, 2016; Hidalgo, 2005; Hidalgo et al, 2006). NOX4 is constitutively active and localized to the sarcoplasmic reticulum and inner mitochondrial mitochondria with the capability to produce O2•− or H2O2 (Ferreira and Laitano, 2016; Nisimoto et al, 2014).

There is emerging evidence that mitochondrial targeted NOX4 plays a role in mitochondrial-derived ROS and energy sensing (Shanmugasundaram et al, 2017) through redox crosstalk. The NOXs and mitochondria are primary sources of ROS in skeletal muscle and naturally due to proximity, a redox-mediated crosstalk between the two sources could disrupt homeostatic redox signaling. Crosstalk can be initiated by mitochondria in states of impaired metabolism and increased ROS, which activate redox-sensitive kinases and subsequently NOXs; however, on the other hand, NOX-derived ROS can oxidize and promote mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channel opening and influx of K+ into the matrix as well as increasing intracellular calcium concentrations, ultimately causing mitochondrial swelling, opening of permeability transition pores, and elevated ROS production (Brandes, 2005; Daiber, 2010; Ferreira and Laitano, 2016).

Cytosolic sources

The CYPs are a diverse group of heme monooxygenases best known for their role in xenobiotic metabolism (Veith and Moorthy, 2018). The CYPs are capable of directly producing O2•− and H2O2 (White and Coon, 1980), and among the 57 putative isoforms, 5 main CYPs perform most of the identified reactions (Veith and Moorthy, 2018). Two shunts are believed to exist within the CYP catalytic cycle that can generate ROS without completion of substrate oxidation and is known as “reaction uncoupling” (Veith and Moorthy, 2018).

The first site releases O2•− and the second site occurs after the addition of a proton to the reduced oxygen complex, leading to direct formation of H2O2 (Veith and Moorthy, 2018). The ROS generated by CYPs through the course of their reactive cycle can then go on to modify cellular components, which, in turn, can lead to oxidative stress. In conditions such as CKD, metabolites that accumulate in the blood have been described to activate transcriptional pathways to elevate CYP activity and ultimately the removal of endogenous or exogenous toxins (Brito et al, 2019). However, the extent to which CYPs play a role in redox imbalance in CKD in muscle is unknown.

Other sources

The XOs are redox active enzymes that play a role in redox signaling and ROS production specifically in the endothelium and extracellular environment of skeletal muscle (Gomez-Cabrera et al, 2005; Hellsten et al, 1997). It has been reported that this enzyme exists as two separate forms, originally as xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH), but can be converted to XO reversibly by the oxidation of sulfhydryl residues or irreversibly by proteolysis (Chung et al, 1997; Della Corte and Stirpe, 1968). XDH acts on the same substrates (hypoxanthine or xanthine) but utilizes NAD as a cofactor producing NADH and uric acid, whereas XO utilizes O2 as an electron donor and produces O2•− and uric acid. Interestingly, Derbre et al (2012) demonstrated that the inhibition of XO using allopurinol prevents XO-mediated oxidative damage and prevents skeletal muscle atrophy through activation of the p38 MAP Kinase pathway and subsequent activation of E3 muscle-specific ligases Atrogin-1 and MURF-1.

Antioxidant systems

Skeletal muscle contains an intricate antioxidant network that plays a crucial role in the maintenance of redox balance (Fig. 3). SOD was discovered in 1969 by McCord and Fridovich (1969) and forms the first line of defense against O2•−. SOD catalyzes the reaction of O2•− → H2O2 + O2. SOD exists as three isoforms (SOD1–3) with the requirement of a redox active transition metal in the active site to accomplish the catalytic breakdown of O2•− (Powers et al, 2012; Powers et al, 2011). Isoforms SOD1 and SOD3 contain a copper-zinc transition metal within the catalytic site and are primarily located within the cytosol and extracellular space, respectively.

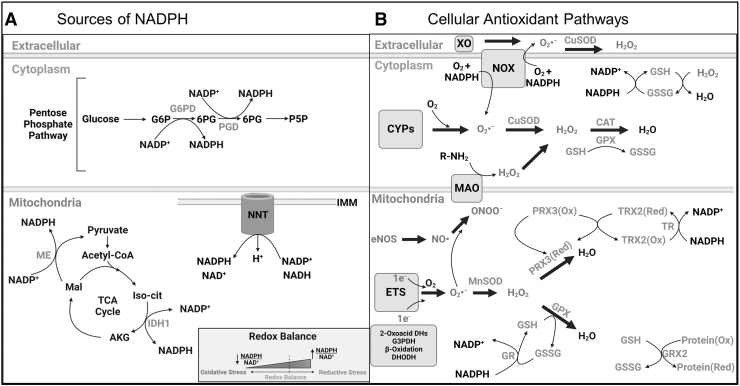

FIG. 3.

An overview of redox homeostasis in skeletal muscle. (A) The major sources of reducing power (NADPH) in the cytosol and mitochondria that support antioxidant enzymes. (B) Major sources of ROS production and scavenging pathways in the cytosol and mitochondrion. AKG, alpha ketoglutarate; CAT, catalase; CYPs, cytochrome P450 enzymes; DHODH, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase; GPX, glutathione peroxidase; GR, glutathione reductase; GRX, glutaredoxin; GSH, reduced glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; Mal, malate; MAO, monoamine oxidase; ME, malic enzyme; NADP, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NO, nitric oxide; NOX, NADPH oxidase; ONOO−, peroxynitrite; PRX, peroxiredoxin; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TR, thioredoxin reductase; TRX, thioredoxin; XO, xanthine oxidase. Illustration created using BioRender.com

SOD2 contains a manganese (Mn) catalytic core and is found within the mitochondrial matrix. Being the first line of defense with a high catalytic rate, most O2•− produced is rapidly converted to H2O2 near the site of production. However, excess levels of H2O2 can be toxic to the cell and removal is necessary. Glutathione peroxidase (GPX) is a major antioxidant enzyme found in mammals with five known isoforms (GPX1–5) (Brigelius-Flohé, 2006). Glutathione is the non-enzymatic tripeptide that serves as a substrate for GPX, and most GPX isoforms require reduced glutathione (GSH) to provide electrons to reduce H2O2 and lipid hydroperoxides (isoforms have different substrate preferences), resulting in the formation of oxidized glutathione (GSSG) during this process.

Glutathione reductase (GR) is a flavin-containing enzyme that is capable of regenerating GSH through the consumption of NADPH (McKenna et al, 2006). Importantly, GPX enzymes are present in several cellular compartments, including the cytosol, mitochondria, and nucleus. Glutaredoxin (GRX) is a thiodisulfide involved in the protection and repair of protein and non-protein thiols during periods of increased oxidative stress. This process is coupled with glutathione and GR activity (Gladyshev et al, 2001). Peroxiredoxins (PRX) are another antioxidant pathway that plays an essential role in reducing hydroperoxides and ONOO− (Chae et al, 1999; Powers and Jackson, 2008).

There are six identified PRX isoforms: PRX1, 2, and 6 are located within the cytosol, whereas PRX3 is found in the mitochondria, PRX4 in the extracellular space, and PRX5 can be found within mitochondria and peroxisomes (Powers and Jackson, 2008). PRXs derive their reducing power through coupling with Thioredoxin (TRX) and thioredoxin reductase (TR). TRX is a major ubiquitous disulfide reductase responsible for maintaining proteins in their reduced state and can be found in the cytosol (TRX1) and mitochondria (TRX2) (Berndt et al, 2007; Lillig and Holmgren, 2007). Once oxidized, TRX is reduced via TR using NADPH.

Finally, catalase (CAT) is expressed ubiquitously in most tissues and can catalyze the breakdown H2O2 into H2O and O2 (Luck, 1954). CAT proteins are abundant in oxidative muscle fibers, but they are also expressed at lower levels in fast/oxidative muscle fibers (Boveris and Chance, 1973; Powers and Jackson, 2008). However, unlike some cell types, catalase is not found in skeletal muscle mitochondria (Rath et al, 2021). For a comprehensive review of antioxidant enzymes and pathways, readers are encouraged to review the following references: Halliwell and Gutteridge (2007), Powers and Jackson (2008), Powers et al (2012), and Powers et al (2011).

Muscle Mitochondrial and Redox Alterations in CKD

As highlighted earlier, skeletal muscle mitochondrial and redox abnormalities have emerged as central factors believed to be causally involved in the myopathic phenotype in CKD (Fig. 4). Work published in the 1990s sparked interest in the involvement of mitochondria in CKD when a few groups demonstrated that patients with renal insufficiency exhibited deficits in skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism when compared with healthy individuals (Conjard et al, 1995; Durozard et al, 1993; Kemp et al, 2004; Pastoris et al, 1997; Thompson et al, 1993).

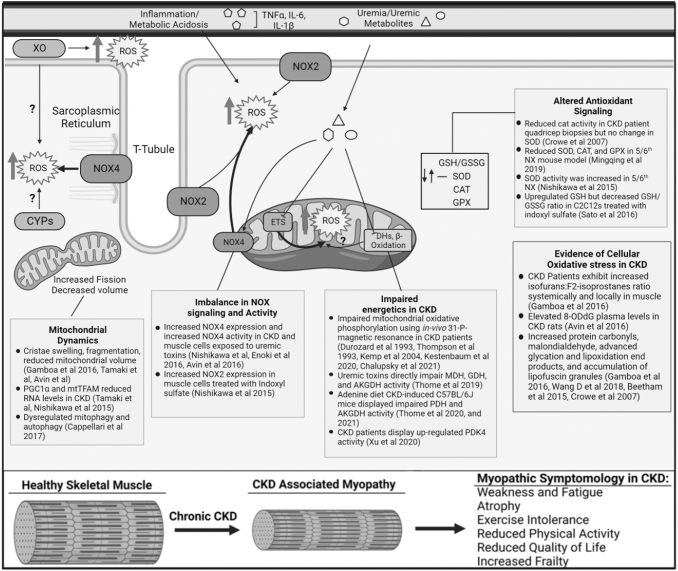

FIG. 4.

Altered mitochondrial metabolism and redox homeostasis in CKD. Muscle from patients or animals with CKD display histological signs of mitochondrial pathology (cristae swelling, fragmentation, mitophagosome accumulation), reduced mitochondrial mass, enzyme activity, and oxygen consumption. Uremic toxin accumulation is associated with impaired mitochondrial metabolism through reductions in dehydrogenase enzyme activity. Biomarkers of oxidative stress are commonly reported in CKD muscle; however, the sources are not fully understood. NADPH (NOX) enzymes display increased abundance and activity in CKD muscle, whereas a few studies have thoroughly evaluated the mitochondria as a source contributing to muscle oxidative stress in CKD. The biochemical alterations in mitochondrial metabolism and redox homeostasis are consistent with the observed myopathic phenotype, including muscle atrophy, weakness, and increased fatiguability—all features that have been directly linked to muscle pathologies in non-CKD conditions. Illustration created using BioRender.com

For example, Durozard et al (1993) and Thompson et al (1993) examined skeletal muscle metabolism during and after exercise in patients with CKD using 31Phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P-MRS). These in vivo studies reported greater depletion of ATP and decrease in pH during muscular exercise, as well as slower recovery times for both PCr and intracellular pH levels in patients with CKD, observations that are suggestive of impaired mitochondrial oxidative metabolism (Durozard et al, 1993; Thompson et al, 1993). A subsequent 31P-MRS study on male CKD patients undergoing hemodialysis also reported slowed PCr resynthesis after exercise, which occurred independent of a microvascular defect (assessed by near-infrared spectroscopy)—a finding that indicated an intrinsic mitochondrial defect may have been present in CKD muscle (Kemp et al, 2004).

Since these initial studies, there has been an insurgence of reports linking mitochondrial function to the CKD-associated myopathy present in patients. Gamboa et al performed several clinical studies documenting mitochondrial abnormalities found in CKD patient muscle biopsies, including morphological changes (cristae swelling, autophagosomes surrounding mitochondria), reduced mitochondrial volume using stereological methods, and prolonged PCr recovery after exercise (Gamboa et al, 2020; Gamboa et al, 2016). Further, prolonged PCr recovery times were present before initiation of hemodialysis treatment, could distinguish CKD patients in the lowest and highest estimated glomerular filtration rate tertiles, and were significantly associated with walking performance (Gamboa et al, 2020).

These findings were confirmed by another recent study from Kestenbaum et al (2020) that measured maximal rates of ATP synthesis and oxygen consumption in the leg muscle of 53 CKD patients and 24 non-CKD volunteers. In ESKD patients on long-term hemodialysis awaiting kidney transplantation, alterations in mitochondrial structure, elevated mitophagy, and a shift toward fast/glycolytic fiber type were observed and linked to lower muscle endurance (Souweine et al, 2021). Importantly, these deficits in muscle oxidative metabolism could explain the symptoms of fatigue and exercise intolerance commonly reported by CKD patients.

Unfortunately, a recent randomized clinical exercise trial was unsuccessful at stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis or increasing muscle mitochondrial mass, suggesting that the adaptive capacity of CKD muscle may be limited (Watson et al, 2020).

In the pursuit of uncovering the molecular/biochemical mechanisms underlying impaired mitochondrial oxidative metabolism, preclinical models of CKD including surgical removal of 5/6th of the renal tissue (5/6th Nx), diet-induced kidney injury (adenine or oxalate supplementation), ischemia perfusion injury, and genetically engineered rodents with a predisposition to develop renal insufficiency have been employed (Engle et al, 1996; Enoki et al, 2016; Khattri et al, 2021; Kim et al, 2021; Stockelman et al, 1998; Strauch and Gretz, 1988; Wang et al, 2018; Wang et al, 2009). Like patients with CKD, rodents with CKD also exhibit reduced running capacity, lower muscle mitochondrial content, decreased enzymatic activity of ETS respiratory complexes, and lower rates of maximal respiration (stimulated by saturating ADP concentrations) (Berru et al, 2019; Gortan Cappellari et al, 2017; Nishikawa et al, 2015; Tamaki et al, 2014; Yazdi et al, 2013). Further to this, uremic toxins, including indoxyl sulfate (IS), have been linked to muscle mitochondrial metabolic alterations using both rodent models of CKD and in vitro culture systems (Nishikawa et al, 2015; Sato et al, 2016; Thome et al, 2019).

In male mice subjected to 5/6 Nx, Tamaki et al (2014) reported lower mitochondrial mass, as well as cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV of the ETS) and pyruvate dehydrogenase enzyme activities compared with sham controls with normal renal function. Further, Tamaki et al observed that the altered mitochondrial function occurred before the onset of muscle atrophy or functional declines, raising the intriguing hypothesis that mitochondria may be a driver the muscle wasting in CKD. Interestingly, these mitochondrial alterations were worsened by consumption of a high protein diet, but treatment with dichloroacetate to increase pyruvate dehydrogenase activity rescued exercise capacity in CKD mice.

Using an adenine-diet model to induce CKD, two recent studies employed a bioenergetic phenotyping analysis to further investigate the biochemical underpinnings of impaired muscle OXPHOS in CKD. Consistent with the studies discussed earlier, reduced activity of matrix dehydrogenases (pyruvate dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase), but not alterations in mitochondrial ETS enzyme function, were reported to explain the deficit in muscle mitochondrial OXPHOS (Thome et al, 2021; Thome et al, 2020).

Taken together, these findings from animal models of CKD are consistent with a recent study in patients with ESKD that reported an upregulation pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-4 activation, which phosphorylates the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex leading to reduced enzyme activity (Xu et al, 2020). Beyond phosphorylation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase enzyme, an untapped area of research in CKD surrounds the investigation of the role of post-transcriptional control of mitochondrial metabolism (i.e., acetylation, malonylation, succinylation, glutarylation, and phosphorylation of mitochondrial proteins) in disease pathobiology (Karwi et al, 2019).

As reviewed later, several components of muscle atrophy signaling pathways have been shown to be redox sensitive and thus activated under conditions of oxidative stress. Based on this knowledge, it has been hypothesized that muscle oxidative stress may be an important contributor to the muscle wasting phenotype in CKD. In support of this hypothesis, a growing body of evidence has documented elevated biomarkers of oxidative stress (F2-isoprostanes, 8-ODdG, protein carbonylation, malondialdehydes) in both the plasma and skeletal muscle of patients with CKD (Beetham et al, 2015; Crowe et al, 2007; Daschner et al, 1996; Gamboa et al, 2020; Gamboa et al, 2016).

Importantly, the presence of elevated oxidative stress has been reported to occur before initiation of dialysis treatment (Gamboa et al, 2020; Gamboa et al, 2016). However, not all studies in CKD muscle have observed equivalent increases in certain biomarkers of oxidative stress (Crowe et al, 2007). Several of these oxidative stress biomarkers have also been shown to be elevated in muscle from animal models of CKD (Avin et al, 2016; Enoki et al, 2017; Enoki et al, 2016; Wang et al, 2018). Although many studies support the presence of elevated oxidative stress in CKD muscle, the topology of ROS production is not fully understood.

The accumulation of uremic toxins has recently become of interest as a mechanism stimulating oxidative stress. Specifically, the metabolites p-cresol sulfate, IS, kynurenines, indole-3-acetic acid, and methyl-guanidine have been shown to increase mitochondrial and NOX-derived ROS production (Berru et al, 2019; Changchien et al, 2019; Enoki et al, 2016; Nishikawa et al, 2015; Sato et al, 2016; Thome et al, 2019). Sato et al (2016) reported that C2C12 myotubes treated with IS increased total glutathione levels but decreased GSH/GSSG ratio (an indicator of oxidative stress) and increased OH•− detected by electron spin resonance.

Another study reported that C2C12 myotubes treated with IS increased NOX gene expression and activity (Nishikawa et al, 2015). In CKD mice treated with AST-120, or oral adsorbent that reduces IS levels, lower rates of muscle-derived superoxide production were reported (Nishikawa et al, 2015). Considering the multitude of sites and capacity for ROS production, the mitochondrion has been implicated as a contributor to the oxidative stress conditions in CKD muscle. However, only a few studies have performed direct measurements of mitochondrial ROS production in CKD muscle.

Gortan Cappellari et al (2017) recently reported increased mitochondrial H2O2 production in muscle from rats with CKD, an alteration that was prevented by treatment with unacylated ghrelin. An important consideration from this study is that mitochondrial H2O2 production levels were measured under conditions with maximal fuel and a complete absence of energetic demand, a scenario that is never present in living muscle cells. Notably, when muscle mitochondria were assayed under conditions mimicking a resting energetic demand, mice with CKD did not display increased ROS production compared with controls (Thome et al, 2021; Thome et al, 2020).

These findings raise questions regarding the role of mitochondrial ROS in the observed oxidative stress condition in CKD muscle. However, to our knowledge, accurate and specific analyses of mitochondrial-derived ROS have not been reported in CKD patient muscle. Thus, a comprehensive and rigorous analysis of skeletal muscle energetics and identification of ROS sources in CKD patients is necessary. Studies of such as nature could provide a platform for testing the effectiveness of mitochondrial-targeted therapies, a field that has been rapidly growing (Andreux et al, 2013; Murphy and Hartley, 2018; Wallace et al, 2010), at improving muscle health and function in CKD.

Redox Signaling and Muscle Atrophy

Over the past several decades, several processes regulating skeletal muscle protein synthesis and degradation have been identified as being responsive to redox alterations (for detailed reviews on this topic the readers are directed to the following review articles: Gomez-Cabrera et al, 2020; Powers et al, 2020; Powers et al, 2016). For example, increasing the level of ROS inside skeletal muscle has been shown to inhibit the anabolic IGF-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway (Fig. 5), a key pathway governing protein synthesis (Bonaldo and Sandri, 2013; Schiaffino et al, 2013).

FIG. 5.

A review of redox signaling and muscle atrophy. There is an abundance of literature documenting that key catabolic and anabolic pathways in skeletal muscle are altered through redox mechanisms. Increase in ROS contributes to a variety of catabolic pathways, including activation of calpains, caspase 3, autophagy, E3-ubiquitin ligases, NF-kappa B (NF-κB), and atrogene expression (FOXOs). Moreover, elevated ROS levels impair protein synthesis via the IGF1-mTORC1 pathway. Overall, these conditions precipitate an imbalance of protein synthesis and degradation rates, resulting in loss of muscle proteins and atrophy. Illustration created using BioRender.com

Several studies have demonstrated that ROS (H2O2) modifies insulin-regulated protein synthesis through the PI3K-Akt-mTOR axis (Berdichevsky et al, 2010; Durgadoss et al, 2012; Gardner et al, 2003; Konishi et al, 1997; Murata et al, 2003; Sadidi et al, 2009; Shaw et al, 1998; Tan et al, 2015; Ushio-Fukai et al, 1999; Wu et al, 2013). However, some studies suggest that ROS inhibit the activation of the PI3K-Akt signaling in skeletal muscle (Berdichevsky et al, 2010; Tan et al, 2015), whereas others indicate that ROS promotes the activation of PI3K-Akt signaling cascade (Konishi et al, 1997; Sadidi et al, 2009; Shaw et al, 1998; Ushio-Fukai et al, 1999; Wu et al, 2013).

The apparent contradictions are likely reflective of subtle experimental differences, including the model of ROS generation, concentrations of ROS, model system (cell culture vs. animal), and species. Downstream of AKT, increased ROS levels have been shown to interfere with phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and S6K1 and diminish protein synthesis (Feng et al, 2005). Taken together, this body of work suggests that elevated oxidative stress reduces muscle protein synthesis.

There is also abundant evidence indicating that the proteolytic systems are also redox sensitive and that oxidative stress conditions elevate muscle proteolysis. Numerous in vivo and in vitro studies have provided compelling evidence indicating that elevated ROS stimulate autophagy via the activation of AMPK, which suppresses mTORC1 activation leading to increased activation of ULK1 (Navarro-Yepes et al, 2014; Powers et al, 2020; Rodney et al, 2016). In skeletal muscle, increasing ROS (i.e., H2O2 exposure) raises autophagy-related gene expression (ULK1, LC3, beclin 1, cathepsin) and autophagosome formation (reviewed by Navarro-Yepes et al, 2014; Powers et al, 2020).

In addition, the Forkhead Box O family (FoxO1, FoxO3, FoxO4) of transcription factors, which coordinates expression of both the autophagy and ubiquitin-proteasome systems, are also redox sensitive (Cheng, 2019; Dodd et al, 2010). Triple knockout of FoxO1, 3, and 4 in skeletal muscle is sufficient to prevent atrophy and the induction of autophagy and ubiquitin-proteasome system (Milan et al, 2015). Reducing H2O2 levels via catalase expression was shown to prevent FoxO activation and attenuate disuse atrophy (Dodd et al, 2010).

Oxidative stress has been shown to alter intracellular calcium handling (Kourie, 1998; Qaisar et al, 2018) and increase calcium-mediated calpain activation (Dargelos et al, 2010; Dargelos et al, 2008). Calpains are non-lysosomal calcium-activated cysteine proteases that are involved in protein selective cleavage (Campbell and Davies, 2012). Several studies using cell and animal models have demonstrated that calpains are involved in ROS-induced muscle atrophy (Dargelos et al, 2010; McClung et al, 2009), and that inhibition of calpains confers some level of protection against atrophy (Hyatt et al, 2022; Hyatt et al, 2021; Zeng et al, 2021).

Caspase-3, which is known to cleave skeletal muscle actin and contribute to atrophy (Du et al, 2004; McClung et al, 2007; Nelson et al, 2012), can also be activated by calpains (Nelson et al, 2012) or by high intracellular calcium concentrations (via caspase-12 activation and caspase-9 activation) (Powers et al, 2007; Powers et al, 2005). Further, a recent in vitro study provided evidence suggesting that mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT), driven by the formation of a multi-protein pore that can form in the inner mitochondrial membrane, is a key event driving muscle atrophy through an increased mitochondrial ROS emission and caspase-3 activation via cytochrome c release (Burke et al, 2021).

Mitochondrial and Redox Homeostasis in Muscle Stem Cell Biology: An Untapped Resource in CKD

It is now well known that skeletal muscle contains stem cells, often defined as satellite cells, that are crucial for myogenesis and muscle regeneration (Collins and Kardon, 2021; Dumont et al, 2015; Lepper et al, 2011; Lepper et al, 2009; Mauro, 1961). Since their initial discovery (Mauro, 1961), the subsequent generation of Pax7CreER mouse models has provided a platform for researchers to investigate muscle stem cell biology in a variety of physiological and pathological conditions. Satellite cells reside beneath the basal lamina, outside the sarcolemma, where a large proportion of them are thought to be quiescent.

Following various stimuli (contraction, stretch, injury, etc.), a portion of these satellite cells become activated, proliferate, and differentiate into myocytes that can fuse with myofibers, resulting in nuclear accretion. Much has been learned about how genes, particularly of myogenic factors (MYOD, MYOG, Myf5), control muscle stem cell function/fate, although the development of single-cell RNA-sequencing and mass cytometry have raised the intriguing possibility of greater heterogeneity in the muscle stem population (Barruet et al, 2020; De Micheli et al, 2020; McKellar et al, 2021). Moreover, there is an incomplete understanding of how cellular processes, such as those that control as bioenergetic and redox tone, govern muscle stem cell behavior.

Transitions between the heterogenous satellite cell states (quiescence, proliferation, differentiation) require unique metabolic programming (Pala et al, 2018). For example, proliferating and differentiating satellite cells must upregulate anabolic pathways for protein, nucleotide, and phospholipid biosynthesis to support mitosis and cell growth (Fig. 6). Quiescent and self-renewing satellite cells appear to rely heavily on fatty acid oxidation to support their relatively low energetic demands (Pala et al, 2018).

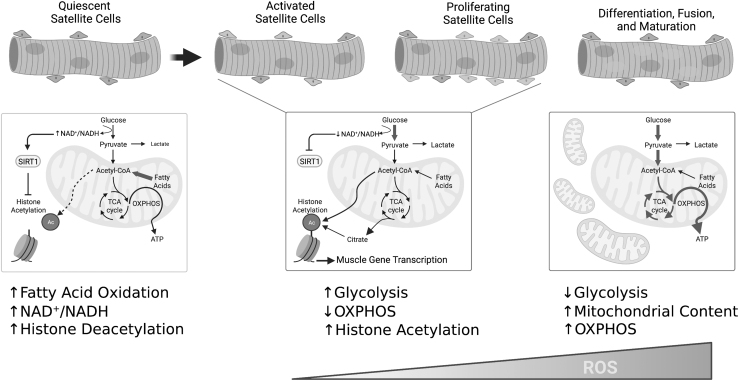

FIG. 6.

Mitochondrial and redox control of muscle stem function. Emerging evidence has shed light on the importance of metabolic and redox changes in the biology of resident muscle stem cells. Quiescent satellite cells rely heavily on fatty acid oxidation and drive suppression of myogenic gene transcription via histone deacetylation. In contrast, activated/proliferating satellite cells activate glycolysis and decrease mitochondrial OXPHOS leading to histone acetylation and expression of key myogenic transcription factors. Finally, a robust increase in mitochondrial mass and OXPHOS are required for differentiation and maturation. Coincidently, ROS levels increase through the course of differentiation/maturation. The impact of CKD on muscle stem energetics and redox homeostasis represents an unexplored area of research. OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation. Illustration created using BioRender.com

During activation and subsequent proliferation of satellite cells, there is a robust upregulation of glycolytic metabolism (Repele et al, 2013; Yucel et al, 2019), which provides not only ATP for energetically costly cellular processes, but also intermediate substrates for biomass production. Several groups have demonstrated that hypoxia and HIF2α activation promote satellite cell stemness or self-renewal (Abreu and Kowaltowski, 2020; Liu et al, 2012; Xie et al, 2018), whereas hyperoxia impairs proliferation (Duguez et al, 2012). Chen et al (2019) identified the transcription factor Yin Yang1 (YY1) as both a promoter of glycolytic metabolism and a repressor of mitochondrial metabolism in satellite cells.

Deletion of YY1 in satellite cells resulted in a defect in activation and proliferation that prevented injury-induced muscle regeneration. Further, endurance exercise training was also recently shown to promote satellite cell self-renewal and activation via a suppression in mitochondrial metabolism, a feature that was observed to improve muscle regeneration (Abreu and Kowaltowski, 2020). Additional in vitro evidence from the Partridge lab (Duguez et al, 2012) showed that treatment with oligomycin A (an ATP synthase inhibitor) or the ETS protonophore CCCP (carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone) enhanced myoblast proliferation.

In contrast to quiescence, self-renewal, and activation/proliferation, satellite cell differentiation, fusion, and maturation coincide with robust mitochondrial biogenesis (Fortini et al, 2016) and a switch toward oxidative metabolism, a process that is at least partially regulated by MyoD expression (Shintaku et al, 2016). Further, glucose restriction has been shown to impair myoblast differentiation (Fulco et al, 2008). The metabolic reprogramming necessary to support differentiation/myogenesis has been partially attributed to altered cellular NAD+/NADH redox charge and SIRT1 activation (Fulco et al, 2008; Ryall et al, 2015).

Oxidative stress and redox homeostasis have also emerged as key regulators of stem cell function (reviewed by Tan and Suda, 2018). Early evidence in satellite cells uncovered a role for NADPH oxidase-derived ROS as a promoter of proliferation, whereas inhibition with apocynin attenuated proliferation in vitro (Mofarrahi et al, 2008). A subsequent study further demonstrated that overexpression of PRX2 or treatment with N-acetylcysteine resulted in impaired myogenesis in cultured myoblasts (Won et al, 2012).

However, it is important to carefully interpret these results in the context of redox homeostasis where the “optimal” cell function requires a delicate balance between oxidative and reductive stress. For example, knockout of transcription factors Pitx2/3 resulted in abnormally high levels of ROS that impaired myogenesis (L'honore et al, 2016). Notably, the defect in differentiation following ablation of Pitx2/3 could be rescued with N-acetylcysteine treatment. In an elegant study, L'honore et al (2018) demonstrated that a physiological increase in ROS levels promotes satellite cells to exit the cycle and progress toward terminal differentiation, a process regulated by redox activation of p38α MAP kinase. Physiological levels of ROS enhanced myogenesis, whereas high ROS levels were reported to cause satellite cell senescence.

Despite the wealth of literature investigating skeletal myopathy in CKD, information on the function of satellite cells is relatively sparse, and in some instances findings from animal models and humans with CKD are inconsistent. It was recently reported that CKD patients exhibited a lower abundance of satellite cells compared with non-CKD controls (Brightwell et al, 2021). Similarly, mice subjected to subtotal nephrectomy have been shown to exhibit lower numbers of muscle progenitor cells compared with sham mice (Wang et al, 2009).

Interestingly, compared with CKD Stage 4/5 patients, patients on maintenance hemodialysis displayed significantly more satellite cells per myofiber (Brightwell et al, 2021), an observation that implicates a systemic factor (uremic solute/metabolite) as a possible regulator of satellite cell homeostasis in CKD. A recent in vitro study using CKD patient-derived muscle progenitor cells reported normal levels of proliferation markers (Ki-67, Myf5) and myotube fusion index and size (a marker of differentiation) (Baker et al, 2022).

Further to this, the messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of myogenic regulatory factors (Myf5, MyoD, myogenin) in CKD-derived muscle progenitor cells were either normal or slightly increased compared with non-CKD donors. However, despite normal proliferation and fusion phenotypes, muscle progenitor cells from CKD patients exhibited elevated levels of atrogene expression (Fbxo32 and Trim63) and protein degradation rates coupled with reduced protein synthesis rates following stimulation with IGF-1 when compared with those obtained from non-CKD controls.

In contrast, Zhang et al (2010) found that satellite cells isolated from mice with CKD expressed lower levels of MyoD and myogenin and did not form myotubes well following serum deprivation in vitro. The CKD mice also displayed impaired muscle regeneration from cardiotoxin injury compared with non-CKD control mice. Mechanistically, one study has linked increased angiotensin II levels to the depletion of satellite cells and their impaired myogenic progression (Yoshida et al, 2013).

The inconsistencies between human and animal studies on satellite cells in CKD likely stem from the different analytical approaches and cell isolation methods, as well as potential biological differences in muscle stem cells across species. Considering the technical advancements in the stem cell biology field, there is a dire need for new studies aimed at elucidating the impact of CKD in satellite cell biology and their respective contribution to the skeletal myopathy.

Summary and Perspectives

Skeletal muscle health and function are strong predictors of all-cause mortality in humans. Unfortunately, reduced skeletal muscle function is a common consequence of numerous acquired diseases, including CKDs. The CKD leads to a progressive and debilitating myopathy characterized by muscle weakness, fatigue, and atrophy/wasting that negatively impact functional independence and quality of life. Future work is needed to rigorously assess how this myopathy is related to physical activity levels in CKD as a healthy lifestyle is often promoted as the best strategy for managing CKD. Unfortunately, available treatments such as hemodialysis do not appear to correct all aspects of the myopathy (Ikizler et al, 2002).

The physiological milieu created by renal dysfunction creates a toxic environment characterized by uremic toxin accumulation and a chronic inflammatory state that disrupt mitochondrial energetics and potentiate oxidative stress conditions manifesting as symptoms of muscle fatigue, weakness, and frailty. Despite what has been learned about the myopathy associated with CKD, no readily available treatments to prevent or attenuate muscle impairment in CKD exist for patients. A greater understanding of the pathobiological mechanisms that drive bioenergetic and redox alterations underlying myopathic symptoms of CKD patients is essential for creating targeted treatments.

The number of therapeutic strategies capable of modulating energy and redox charges continues to grow (Murphy and Hartley, 2018) but a continued effort is required to enhance the precision of these agents. Finally, the emergence of technologies to support personalized medicine approaches can facilitate the understanding of patient-specific genome and metabolome alterations in CKD. When combined with symptomatic, pharmacological, and physiological characteristics, this information is both a daunting challenge and an exciting therapeutic opportunity to improve quality of life in the CKD patient.

Abbreviations Used

- ΔGATP

free energy for ATP hydrolysis

- 31P-MRS

31phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- AKG

alpha ketoglutarate

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- CAT

catalase

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- CoA

coenzyme A

- CPT

carnitine palmitoyltransferase

- CYPs

cytochrome p450 enzymes

- Cyt C

cytochrome c

- DHODH

dihydroorotate dehydrogenase

- ESKD

end-stage kidney disease

- ETS

electron transport system

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- FFAs

free fatty acids

- G3PDH

glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GPX

glutathione peroxidase

- GR

glutathione reductase

- GRX

glutaredoxin

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione

- H+

proton

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- IDH

isocitrate dehydrogenase

- IMM

inner mitochondrial membrane

- IMS

intermembrane space

- IS

indoxyl sulfate

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- Mal

malate

- MAO

monoamine oxidase

- ME

malic enzyme

- NAD

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NADH

reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NADP

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- NOX

NADPH oxidases

- O2•−

superoxide

- OH•−

hydroxyl radical

- OMM

outer mitochondrial membrane

- ONOO−

peroxynitrite

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

- PCr

phosphocreatine

- PDH

pyruvate dehydrogenase

- PRX

peroxiredoxin

- Q

ubiquinone

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

- TR

thioredoxin reductase

- TRX

thioredoxin

- XDH

xanthine dehydrogenase

- XO

xanthine oxidase

- YY1

Yin Yang1

Authors' Contributions

T.T.: Conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization, funding acquisition. K.K.: Writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization, funding acquisition. G.D.: Writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization. T.E.R.: Conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization, funding acquisition, supervision, project administration.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts, financial or otherwise, to report.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01HL149704 (T.E.R.). T.T. was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Fellowship from the NIH/NIDDK, grant number F31-DK128920. K.K. was supported by the American Heart Association grant POST903198.

References

- Abramowitz MK, Paredes W, Zhang K, et al. Skeletal muscle fibrosis is associated with decreased muscle inflammation and weakness in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2018;315(6):F1658–F1669; doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00314.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abreu P, Kowaltowski AJ. Satellite cell self-renewal in endurance exercise is mediated by inhibition of mitochondrial oxygen consumption. J Cachexia Sarcopeni 2020;11(6):1661–1676; doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi H, Fujimoto K, Fujii A, et al. Long-term retrospective observation study to evaluate effects of adiponectin on skeletal muscle in renal transplant recipients. Sci Rep 2020;10(1):10723; doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67711-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade FH, Reid MB, Allen DG, et al. Effect of hydrogen peroxide and dithiothreitol on contractile function of single skeletal muscle fibres from the mouse. J Physiol 1998;509 (Pt 2):565–575; doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.565bn.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre M, Huang E, Everly M, et al. The UNOS renal transplant registry: Review of the last decade. Clin Transpl 2014:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreux PA, Houtkooper RH, Auwerx J. Pharmacological approaches to restore mitochondrial function. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2013;12(6):465–483; doi: 10.1038/nrd4023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Androga L, Sharma D, Amodu A, et al. Sarcopenia, obesity, and mortality in US adults with and without chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Rep 2017;2(2):201–211; doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2016.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avin KG, Chen NX, Organ JM, et al. Skeletal muscle regeneration and oxidative stress are altered in chronic kidney disease. PLoS One 2016;11(8):e0159411; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzi A, Davies KJ, Kelly F. Free radical biology—Terminology and critical thinking. FEBS Lett 2004;558(1–3):3–6; doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01526-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LA, O'Sullivan TF, Robinson KA, et al. Primary skeletal muscle cells from chronic kidney disease patients retain hallmarks of cachexia in vitro. J Cachexia Sarcopeni 2022;13(2):1238–1249; doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban RS. Maintenance of the metabolic homeostasis of the heart: Developing a systems analysis approach. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006;1080:140–153; doi: 10.1196/annals.1380.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barruet E, Garcia SM, Striedinger K, et al. Functionally heterogeneous human satellite cells identified by single cell RNA sequencing. Elife 2020;9:e51576; doi: 10.7554/eLife.51576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beetham KS, Howden EJ, Small DM, et al. Oxidative stress contributes to muscle atrophy in chronic kidney disease patients. Redox Rep 2015;20(3):126–132; doi: 10.1179/1351000214Y.0000000114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello AK, Okpechi IG, Osman MA, et al. Epidemiology of haemodialysis outcomes. Nat Rev Nephrol 2022;18(6):378–395; doi: 10.1038/s41581-022-00542-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdichevsky A, Guarente L, Bose A. Acute oxidative stress can reverse insulin resistance by inactivation of cytoplasmic JNK. J Biol Chem 2010;285(28):21581–21589; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.093633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt C, Lillig CH, Holmgren A. Thiol-based mechanisms of the thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems: Implications for diseases in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007;292(3):H1227–H1236; doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01162.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berru FN, Gray SE, Thome T, et al. Chronic kidney disease exacerbates ischemic limb myopathy in mice via altered mitochondrial energetics. Sci Rep 2019;9(1):15547; doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52107-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleier L, Wittig I, Heide H, et al. Generator-specific targets of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med 2015;78:1–10; doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.10.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaldo P, Sandri M. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of muscle atrophy. Dis Model Mech 2013;6(1):25–39; doi: 10.1242/dmm.010389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveris A, Chance B. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem J 1973;134(3):707–716; doi: 10.1042/bj1340707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand MD. The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp Gerontol 2010;45(7–8):466–472; doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand MD, Nicholls DG. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem J 2011;435(2):297–312; doi: 10.1042/BJ20110162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes RP. Triggering mitochondrial radical release: A new function for NADPH oxidases. Hypertension 2005;45(5):847–848; doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000165019.32059.b2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigelius-Flohé R. Glutathione peroxidases and redox-regulated transcription factors. Biol Chem 2006;387(10–11):1329–1335; doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brightwell CR, Kulkarni AS, Paredes W, et al. Muscle fibrosis and maladaptation occur progressively in CKD and are rescued by dialysis. JCI Insight 2021;6(24):e150112; doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.150112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito JS, Borges NA, Anjos JSD, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor and uremic toxins from the gut microbiota in chronic kidney disease patients: Is there a relationship between them? Biochemistry 2019;58(15):2054–2060; doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b01305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruinius JW, Hannan M, Chen J, et al. Self-reported physical activity and cardiovascular events in adults with CKD: Findings from the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) study. Am J Kidney Dis 2022;80(6):751–761.e1; doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SK, Solania A, Wolan DW, et al. Mitochondrial permeability transition causes mitochondrial reactive oxygen species- and caspase 3-dependent atrophy of single adult mouse skeletal muscle fibers. Cells 2021;10(10):2586; doi: 10.3390/cells10102586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenas E, Boveris A, Ragan CI, et al. Production of superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide by NADH-ubiquinone reductase and ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase from beef-heart mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys 1977;180(2):248–257; doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90035-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain DF, Davies RE. Breakdown of adenosine triphosphate during a single contraction of working muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1962;8:361–366; doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(62)90008-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain DF, Infante AA, Davies RE. Chemistry of muscle contraction. Adenosine triphosphate and phosphorylcreatine as energy supplies for single contractions of working muscle. Nature 1962;196:214–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell RL, Davies PL. Structure-function relationships in calpains. Biochem J 2012;447(3):335–351; doi: 10.1042/BJ20120921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cape JL, Bowman MK, Kramer DM. A semiquinone intermediate generated at the Qo site of the cytochrome bc1 complex: Importance for the Q-cycle and superoxide production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104(19):7887–7892; doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702621104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae HZ, Kim HJ, Kang SW, et al. Characterization of three isoforms of mammalian peroxiredoxin that reduce peroxides in the presence of thioredoxin. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1999;45(2–3):101–112; doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(99)00037-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalupsky M, Goodson DA, Gamboa JL, et al. New insights into muscle function in chronic kidney disease and metabolic acidosis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2021;30(3):369–376; doi: 10.1097/Mnh.0000000000000700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changchien CY, Lin YH, Cheng YC, et al. Indoxyl sulfate induces myotube atrophy by ROS-ERK and JNK-MAFbx cascades. Chem Biol Interact 2019;304:43–51; doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen FY, Zhou JJ, Li YY, et al. YY1 regulates skeletal muscle regeneration through controlling metabolic reprogramming of satellite cells. EMBO J 2019;38(10):e99727; doi: 10.15252/embj.201899727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z. The FoxO-autophagy axis in health and disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2019;30(9):658–671; doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2019.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HY, Baek BS, Song SH, et al. Xanthine dehydrogenase/xanthine oxidase and oxidative stress. Age (Omaha) 1997;20(3):127–140; doi: 10.1007/s11357-997-0012-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins BC, Kardon G. It takes all kinds: Heterogeneity among satellite cells and fibro-adipogenic progenitors during skeletal muscle regeneration. Development 2021;148(21):dev199861; doi: 10.1242/dev.199861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commoner B, Townsend J, Pake GE. Free radicals in biological materials. Nature 1954;174(4432):689–691; doi: 10.1038/174689a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conjard A, Ferrier B, Martin M, et al. Effects of chronic renal failure on enzymes of energy metabolism in individual human muscle fibers. J Am Soc Nephrol 1995;6(1):68–74; doi: 10.1681/ASN.V6168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe AV, McArdle A, McArdle F, et al. Markers of oxidative stress in the skeletal muscle of patients on haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007;22(4):1177–1183; doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daiber A. Redox signaling (cross-talk) from and to mitochondria involves mitochondrial pores and reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010;1797(6–7):897–906; doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargelos E, Brulé C, Stuelsatz P, et al. Up-regulation of calcium-dependent proteolysis in human myoblasts under acute oxidative stress. Exp Cell Res 2010;316(1):115–125; doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargelos E, Poussard S, Brulé C, et al. Calcium-dependent proteolytic system and muscle dysfunctions: A possible role of calpains in sarcopenia. Biochimie 2008;90(2):359–368; doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daschner M, Lenhartz H, Bötticher D, et al. Influence of dialysis on plasma lipid peroxidation products and antioxidant levels. Kidney Int 1996;50(4):1268–1272; doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Micheli AJ, Laurilliard EJ, Heinke CL, et al. Single-cell analysis of the muscle stem cell hierarchy identifies heterotypic communication signals involved in skeletal muscle regeneration. Cell Rep 2020;30(10):3583.e5–3595.e5; doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Corte E, Stirpe F. The regulation of rat-liver xanthine oxidase: Activation by proteolytic enzymes. FEBS Lett 1968;2(2):83–84; doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(68)80107-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbre F, Ferrando B, Gomez-Cabrera MC, et al. Inhibition of xanthine oxidase by allopurinol prevents skeletal muscle atrophy: Role of p38 MAPKinase and E3 ubiquitin ligases. PLoS One 2012;7(10):e46668; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd SL, Gagnon BJ, Senf SM, et al. ROS-mediated activation of NF-kappa B and FOXO during muscle disuse. Muscle Nerve 2010;41(1):110–113; doi: 10.1002/mus.21526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doshi S, Moorthi RN, Fried LF, et al. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for peripheral nerve impairment in older adults: A longitudinal analysis of Health, Aging and Body Composition (Health ABC) study. PLoS One 2020;15(12):e0242406; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Wang XN, Miereles C, et al. Activation of caspase-3 is an initial step triggering accelerated muscle proteolysis in catabolic conditions. J Clin Invest 2004;113(1):115–123; doi: 10.1172/Jci200418330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguez S, Duddy WJ, Gnocchi V, et al. Atmospheric oxygen tension slows myoblast proliferation via mitochondrial activation. PLoS One 2012;7(8):e43853; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont NA, Bentzinger CF, Sincennes MC, et al. Satellite cells and skeletal muscle regeneration. Compr Physiol 2015;5(3):1027–1059; doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durgadoss L, Nidadavolu P, Valli RK, et al. Redox modification of Akt mediated by the dopaminergic neurotoxin MPTP, in mouse midbrain, leads to down-regulation of pAkt. FASEB J 2012;26(4):1473–1483; doi: 10.1096/fj.11-194100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durozard D, Pimmel P, Baretto S, et al. 31P NMR spectroscopy investigation of muscle metabolism in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 1993;43(4):885–892; doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle SJ, Stockelman MG, Chen J, et al. Adenine phosphoribosyltransferase-deficient mice develop 2,8-dihydroxyadenine nephrolithiasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93(11):5307–5312; doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoki Y, Watanabe H, Arake R, et al. Indoxyl sulfate potentiates skeletal muscle atrophy by inducing the oxidative stress-mediated expression of myostatin and atrogin-1. Sci Rep 2016;6:32084; doi: 10.1038/srep32084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]