Abstract

Background

Sulfur mustard (SM) is a chemical warfare vesicant that severely injures exposed eyes, lungs, and skin. Mechlorethamine hydrochloride (NM) is widely used as an SM surrogate. This study aimed to develop a depilatory double‐disc (DDD) NM skin burn model for investigating vesicant pharmacotherapy countermeasures.

Methods

Hair removal method (clipping only versus clipping followed by a depilatory), the effect of acetone in the vesicant administration vehicle, NM dose (0.5–20 μmol), vehicle volume (5–20 μl), and time course (0.5–21 days) were investigated using male and female CD‐1 mice. Edema, an indicator of burn response, was assessed by biopsy skin weight. The ideal NM dose to induce partial‐thickness burns was assessed by edema and histopathologic evaluation. The optimized DDD model was validated using an established reagent, NDH‐4338, a cyclooxygenase, inducible nitric oxide synthase, and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor prodrug.

Results

Clipping/depilatory resulted in a 5‐fold higher skin edematous response and was highly reproducible (18‐fold lower %CV) compared to clipping alone. Acetone did not affect edema formation. Peak edema occurred 24–48 h after NM administration using optimized dosing methods and volume. Ideal partial‐thickness burns were achieved with 5 μmol of NM and responded to treatment with NDH‐4338. No differences in burn edematous responses were observed between males and females.

Conclusion

A highly reproducible and sensitive partial‐thickness skin burn model was developed for assessing vesicant pharmacotherapy countermeasures. This model provides clinically relevant wound severity and eliminates the need for organic solvents that induce changes to the skin barrier function.

Keywords: edema, mice, skin, vesicant

Hair impedes solubilized mechlorethamine hydrochloride (NM) getting to the skin surface, but after depilation, NM delivery to the skin surface is consistent. Acetone, known to alter skin barrier function, was found to be unnecessary for NM burn development. The optimal NM dose for dermal‐epidermal separation (vesication) was determined and produced clinically significant burns that could be healed with an established prodrug.

1. INTRODUCTION

Sulfur mustard (SM) has been used as a chemical warfare vesicant to kill or injure civilians and military personnel for over a century. Most fatalities occur 4–5 weeks after exposure. 1 However, victims exposed to high doses of SM (64 mg/kg for dermal and 1500 mg min/m3 for pulmonary exposure) can die within 1 h. 1 Nitrogen mustards, also potential chemical threats, have leaked from World War II stockpiles resulting in human injuries and deaths. 2 The nitrogen mustards and SM are highly reactive bifunctional alkylating agents that injure exposed skin, eyes, and lung tissues. 3 As DNA alkylators, they form covalent bonds at the nucleophilic regions of DNA bases to create inter‐ and intra‐strand crosslinks. 4 Mechlorethamine hydrochloride (NM), a prototype nitrogen mustard, is routinely employed as a SM surrogate as it shares a similar mechanism for cytotoxicity but does not require specialized containment facilities when used in research studies. 5

Pig skin is the most clinically relevant animal model for dermal injury due to its biochemical and structural similarity to human skin. However, the cost of pigs and husbandry requirements limit their feasibility in statistically powered research. 6 , 7 , 8 The mouse ear vesicant model (MEVM) is used to evaluate histopathological changes during acute phases of SM dermal injury. 9 , 10 Casillas et al. reported that histopathological markers such as edema, dermal‐epidermal separation (vesication), and epidermal necrosis increased dose dependently. The MEVM has been successfully used in anti‐vesicant and anti‐inflammatory drug screening. 11 , 12 , 13 Unfortunately, the MEVM is unsuited for long‐term follow‐up since tissue damage extends from the inside to the outside of the ear, creating ‘through and through’ wounds that are difficult to heal. 14 , 15 These burns limit the utility of the MEVM for evaluating pharmacotherapy countermeasures.

SM wound healing research has primarily focused on deep dermal injuries. 16 Superficial partial‐thickness skin burns (SPSBs) extend through the epidermis into the papillary dermal layer and present vesication with moderate edema. 17 Deep partial‐thickness skin burns (DPSBs) extend to the reticular layer of the dermis and exhibit broken blisters with marked edema. Ideal burns for this model are defined as those resulting from the lowest dose to produce vesication, as more severe SPSBs frequently develop into DPSBs that can take longer than 3 weeks to heal and require skin grafting. 17 , 18 SPSB injuries are suitable for pharmacotherapy as they do not require surgical treatment and may have greater clinical relevance in treating humans exposed to SM. 16 Therefore, the goal is to generate SPSB wounds because they are more clinically relevant for pharmacotherapy than deeper burns that require skin grafting.

Since SM is lipophilic, it requires an organic solvent to make a solution for use in research. On the other hand, water‐soluble NM has been administered in both acetone and water‐acetone vehicles. 19 , 20 , 21 Composto et al. developed a semi‐occlusive patch model in CD‐1 mice, using filter discs to facilitate NM administration in a water‐acetone vehicle to a defined clipped area. 20 This model was used to investigate various markers associated with NM exposure and demonstrate the treatment efficacy of NDH‐4338. Upon testing this model, wound formation was inconsistent. We hypothesized the observed variability might be due to the hair impeding contact between the filter discs and mouse skin. Cuffari et al. reported that the Composto model showed no evidence of vesication and hypothesized that the water‐acetone vehicle failed to distribute NM into the skin. 22 Furthermore, they developed a MEVM using DMSO rather than an acetone or water‐acetone vehicle. Unlike the Composto model, they successfully achieved vesication. However, the vesication rates were inconsistent. 22 , 23 , 24 It has been long believed that organic solvents were required to produce NM wounds. Acetone and DMSO alter skin barrier function, potentially confounding the interpretation of results as they can increase the dermal permeability of potential therapeutic agents. 25 , 26 Low concentrations of DMSO have also been shown to stimulate wound healing in mice. 27 The purpose of this study is to develop a vesicant animal model (i.e., the depilatory double‐disc or DDD model) with a reproducible edematous response that does not use organic solvents and produces clinically relevant wound severity for assessing pharmacotherapeutic countermeasures.

2. METHODS

2.1. Animals

Male and female CD‐1 mice (8–9 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). Upon arrival, mice were allowed to acclimate for at least 3 days before the start of experimentation. Mice were maintained on a 12‐h light/dark cycle in a temperature‐controlled environment at the university animal facility, with food and water ad libitum. All animal studies were conducted under a protocol approved by the Rutgers University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), as described in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health. The sex and total number of animals used in each experiment is detailed in each figure caption. NM‐induced edema in male mice was compared to female mice to verify the stability and repeatability of the burn edematous response and rule out sex differences. No significant differences were found (Figure S1, supplementary data). Therefore, females were selected over males as they are less combative when grouped, decreasing the risk of skin injury that may occur before experimentation. Animal response was monitored by referencing grimace scales and checking for clinical signs of pain, such as hunched posture, inactivity, scruffy coat/unkempt appearance, piloerection, or reluctance to eat/anorexia. Analgesics were administered if any pain response is observed. Animals were euthanized when they met the humane endpoint criteria using the monitoring frequency and criteria established by Rutgers University IACUC policy. A total of 188 mice were used in these studies.

2.2. Reagents

Mechlorethamine hydrochloride (NM) was purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Methylene blue (MB) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). Lanolin (C10‐30 cholesterol/lanosterol esters) and polyethylene glycol 400 were gifted from Croda Inc. (Edison, NJ, USA). NDH‐4338, a cyclooxygenase, inducible nitric oxide synthase, and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor prodrug, was synthesized as described. 28 Ultrapure water (Milli‐Q® Advantage A10®, Type 1 water, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA, water) was used throughout the study.

2.3. Hair removal

Female CD‐1 mice were anesthetized with isoflurane under a fume hood. The dorsal lumbar region was then either only clipped or clipped before applying approximately 50 g/kg of Nair™ Lotion With Baby Oil (Nair, Church and Dwight, Ewing, NJ, USA), a chemical depilatory, to the skin. After 3 min, Nair was rinsed off under warm water. Mice were then gently dried and monitored until recovery from anesthesia. To compare the edematous response of clipping only and clipping before depilatory hair removal methods, parameters of Composto's patch model were used as a starting point to develop the DDD model. The reported 20 μl bolus containing 20 μmol of NM in a 20:80 water: acetone vehicle was delivered to the filter discs and covered by a ParafilmM® thermoplastic (Pechiney Plastic Packaging, Menasha, WI, USA, thermoplastic) strip for 6 min. 20

2.4. NM application

All personnel completed NM safety training approved by Rutgers Environmental Health and Safety (REHS). At 24 h post hair removal, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane under a fume hood and forceps were used to place two 6‐mm glass microfiber filter discs (GE Healthcare, Buckinghampshire, UK) on the dorsal lumbar region equidistant from the spine. NM in a vehicle was applied to the filter discs and occluded with thermoplastic in a single 1 × 3‐inch strip or two 12‐mm discs to prevent vehicle evaporation and facilitate contact between the vesicant and skin. Applying the thermoplastic strip with excessive pressure caused NM to leak outside of the intended wound region, resulting in ‘spread burns’ (Figure S2, supplementary data). After 6 min of exposure, the thermoplastic and filter discs were removed. Residual NM on the skin was then blotted dry with paper towel. Any remaining solubilized NM was disposed of as per REHS guidelines. The mice were monitored while recovering from anesthesia and kept in the fume hood for 24 h when applicable. Mice without NM treatment were used as naive controls.

2.5. Edema measurement

The NM exposed mice were euthanized with CO2 at the indicated time points. Skin punch (12‐mm, Acuderm Inc., Ft Lauderdale, FL, USA) biopsies were then extracted from the treated areas and weighed using an analytical balance. Naive mice were also euthanized in the same fashion and biopsies were obtained from the corresponding dorsal lumbar regions and weighed. Edema was determined by comparing skin weights of the NM treated and naive mice.

2.6. Optimization of NM administration volume and application method

The NM administration volume was investigated to ensure the vesicant was restricted to the filter disc regions. It is also difficult to observe leakage during administration as NM solutions are colorless. MB was used as a surrogate to visualize leakage and calculate delivery efficiency.

Maximum storage capacity, the volume required to saturate the filter disc without resulting in surface pooling or leakage beyond the disc boundaries, was determined by pipetting various volumes of MB solution onto the filter discs. A solution of MB (0.5 mg/ml) in water was prepared and 5, 9, 10, 11, 15, 20 and 25 μl aliquots were added to the filter disc (n = 3) on a polystyrene surface. Visual observation was used to determine an undersaturated, saturated, or oversaturated disc. In a separate study, 15 and 20 μl of MB solution were applied to the filter discs on the back of each mouse. To prevent NM spread burns, 12‐mm thermoplastic discs were placed on the 6‐mm filter discs applying no pressure. The maximum volume that does not result in leakage was considered optimal.

2.7. NM administration vehicle selection

2.7.1. Effect of acetone on skin burn development

The roles of acetone in the NM administration vehicle and effect on edema were evaluated in 3 groups CD‐1 mice (n = 5/group). The first group (NM in Water) received 15 μl of water containing 15 μmol of NM applied to each 6‐mm filter disc. A second group (Acetone Pretreatment + NM in Water) received acetone (25 μl) to the filter discs, which was allowed to dry for 3 min, followed by 15 μl of water containing 15 μmol of NM. The third group (NM in 20:80 Water: Acetone) was administered the same NM dose and volume in a 20:80 water:acetone vehicle to the filter discs. Thermoplastic disc covers (12 mm) were used to occlude each NM saturated filter disc. Mice were photographed at 24‐, 48‐, and 72‐h time points and edema was evaluated as described above.

2.7.2. NM administration buffer

Due to its known instability, NM degradation was controlled to minimize burn variability between groups. The administration buffer was prepared at a pH high enough that aziridinium ring formation occurs (above pH 3), but low enough to minimize degradation (as close to pH 3 as possible). 29 An acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.0) was used as a vehicle for NM administration.

2.8. Optimized DDD model parameters

Mice were clipped and depilated as described above. After hair removal, mice were housed individually for 24 h. The mice were then anesthetized, and 5 μmol of NM (or other doses where specified) in 15 μl of acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.0) was applied to two 6‐mm glass microfiber filter discs as described above. Two 12‐mm thermoplastic discs were used to occlude the filter discs without applying any pressure. The discs were removed, and the residual NM was blotted with a paper towel after 6 min of NM exposure. The mice were kept in the fume hood for 24 h. Mice were euthanized at the desired endpoints, and 12‐mm full‐thickness punch biopsies of the NM exposure site and surrounding tissue were collected and weighed.

2.9. DDD model validation

To ensure this model is useful for therapeutic evaluation, a wound healing efficacy study was performed using a formulation known to treat NM wounds in mice. 20 The DDD model was then validated using a test formulation, NDH‐4338 in 49.5% PEG400 and 49.5% lanolin, that was previously shown to treat NM burns and reduce expression of associated markers such as iNOS, COX‐2 and mast cell degranulation. 20 Optimized DDD model parameters were used for this study. One hour after NM application, mice were anesthetized and 20 μl of NDH‐4338 formulation or vehicle only were applied to the vesicant exposed regions. Mice were then kept unconscious for 5 min before being monitored while recovering from anesthesia. The treatment was administered every 6 h for 24 h (QID), at which point mice were euthanized and edema was evaluated.

2.10. Histology

Skin biopsies were flattened on filter paper, transferred to 10% neutral buffered formalin, and stored at 2–8 °C for 24 h. Biopsies were then stored in 50% ethanol and subjected to routine processing, paraffin embedding and sectioning procedures. Cross‐sections at 5‐μm thickness were stained with hematoxylin and eosin [H&E, Sigma‐Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA)]. Histological images were acquired using an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with an Olympus DP71 camera and DP controller software Ver. 3.3.1.292 (Olympus Corporation, Center Valley, PA, USA). The histopathologic evaluation was conducted by a pathologist at Rutgers Research Pathology Services.

2.11. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was determined by obtaining p < 0.05 for non‐parametric analyses using the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, Kruskal‐Wallis test, and Dunn's multiple comparisons test. All results are reported as means ± SD. The coefficient of variation (%CV), defined as the percentage of the standard deviation (SD) divided by the mean, was used to assess extent of variability.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Effect of hair removal method on NM induced edema

Nair, a depilatory, was employed after clipping (clipping‐Nair) and the results were compared to clipping only. Pathological evaluation of naive controls confirmed the absence of inflammation in skin biopsies from both hair removal methods. A decrease in edematous response %CV between hair removal method groups would indicate an increase in consistency, while an increase in edematous response between groups would signify a higher sensitivity to the same NM dose. Edema in the clipping‐Nair group (130 ± 12 mg skin weight gain) was 5‐fold higher than the clipping‐only group (25 ± 42 mg), with significantly less variability (9.36 versus 168 %CV, respectively), indicating complete hair removal is needed to induce sensitive and consistent NM burns (Figure 1). Due to this increase in sensitivity, a lower dose of NM could be used for the clipping‐Nair method to achieve the same edematous response as the clipping‐only group at the original 20 μmol dose.

FIGURE 1.

Effect of hair removal method on mechlorethamine hydrochloride (NM) induced edema. Each female CD‐1 mouse was given two wounds by applying 20 μl (20:80 water: acetone) containing 20 μmol of NM on two filter discs covered by a single thermoplastic strip. Punch biopsy weights of the NM treated area were used to assess skin edema. Naive control mouse skin weights for both conditions, clipped with and without Nair were subtracted from the respective skin weights of the NM treated groups. Representative photographs are presented of mice 72 h after NM exposure. Clipped mice (A) exhibited mild burns, while mice that were clipped and treated with Nair (B) presented more severe skin burns. Clipping‐only versus clipping‐Nair hair removal methods were assessed for NM induced skin edema in mice (C). Edema in the clipping‐Nair group was significantly higher than the clipping‐only group. Burns were also more reproducible (%CV = 9.36% versus 168%, respectively). Columns represent group mean punch biopsy values ± SD, n = 6/group, two experimental and two control groups, 24 mice total. These data indicate that clipping and depilatory elicit a more severe and reproducible edematous response than that of clipping alone. *p < 0.05 as determined by Wilcoxon matched‐pairs signed rank test.

3.2. Optimization of NM administration volume and application method

The maximum volume capacity of the disc was 10 μl, as the disc was completely saturated with no excess leakage or pooling on the surface. The 11 μl volume showed visible pooling on the surface, confirming that the maximum storage volume had been exceeded (data not shown). Further testing showed that filter discs surrounded by a 12‐mm thermoplastic disc cover could contain 15 μl of MB solution without spillage (data not shown).

Thermoplastic strips were used in Composto's model to prevent acetone evaporation. To overcome the operating effort of applying the strips with consistent pressure and to further facilitate the contact between the filter disc and NM dosing solution, 12‐mm thermoplastic discs were made to replace the strips. These discs could be easily placed on the filter discs using forceps without applying additional pressure. It was determined that the 12‐mm thermoplastic covers provided an even contact between the filter discs and mouse skin, whereas a single strip caused variable pressure that could result in spread burns. The 20 μl volume resulted in spillage outside of the filter disc region, whereas the 15 μl volume did not and was thus selected as the DDD model (data not shown).

3.3. NM administration vehicle selection

3.3.1. Effect of acetone on skin burn development

A visual inspection of skin burns from the NM in Water and Acetone Pretreatment + NM in Water groups showed relatively consistent and symmetrical burns (Figure 2A). The NM in 20:80 Water:Acetone group displayed burns with a wider surface than the other two groups, extending to the outer limits of the 6‐mm filter disc diameter. All mice developed edema in each group. At 72 h after NM exposure, there were no statistically significant differences in skin weight gain between the NM in Water (80 ± 13 mg), Acetone Pretreatment + NM in Water (88 ± 10 mg) and NM in 20:80 Water:Acetone (89 ± 25 mg) groups (Figure 2B), indicating that acetone was not needed to produce significant burns.

FIGURE 2.

Mechlorethamine hydrochloride (NM) vehicle choice exhibited minor changes in skin burn appearance. Clipped and depilated female CD‐1 mice were each given two burns by applying NM solubilized in a water vehicle, with and without acetone pretreatment, or a water‐acetone mixture vehicle. The progression of representative wounds from each group (n = 5/group, three experimental groups, two control groups, 18 mice total) was presented over 3 days. One group (NM in Water) received 15 μmol of NM in 15 μl of ultrapure water. The second group (Acetone Pre‐treatment + NM in Water) received 25 μl of acetone that was allowed to dry for 3 min before receiving 15 μmol of NM in 15 μl of ultrapure water. The third group (NM in 20:80 Water: Acetone) received 15 μmol of NM in 15 μl of 20:80 ultrapure water:acetone. The vast majority of burns in the water vehicle groups, with and without the acetone pretreatment, were identical in terms of area and symmetry. Burns in the NM in 20:80 Water:Acetone group were more spread out from the designated burn area when compared to the others (A), possibly caused by the organic solvent distributing the vesicant outside of the filter disc. Punch biopsy weights of the NM treated area were used to determine the impact of each vehicle on edema 72 h after vesicant exposure (B). Columns represent group mean punch biopsy values ± SD, n = 5/group, three experimental groups, two control groups, 18 mice total. These 18 mice were the same mice from the Figure 2A study. Naive control mouse average punch biopsy weights were subtracted from those of the NM treated groups. One‐way ANOVA with Kruskal‐Wallis test and Dunn's multiple comparisons test determined no significant difference between the three groups, suggesting that acetone was not needed to produce edema.

3.3.2. NM administration buffer

The non‐buffered 1 M NM water solution did not achieve a target pH > 3. However, the NM acetate buffer solution maintained a pH > 3.0 for 2.5 h and was selected for further studies (data not shown).

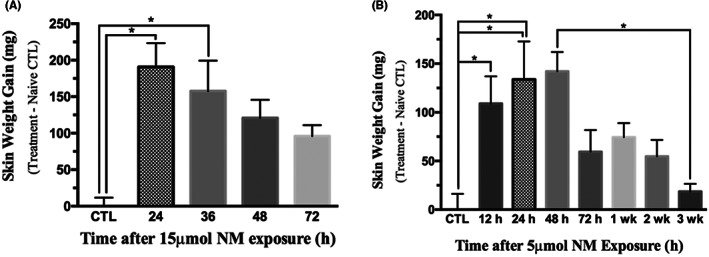

3.4. Optimal study duration determination

The 24‐h group displayed the highest skin edema, while the 36‐, 48‐, and 72‐h groups showed a decreasing trend in skin weight gain induced by 15 μmol of NM (Figure 3A). For the extended time course of the optimized 5 μmol dose, edema was significant from the naive control at 12–48 h and peaked 24–48 h following NM exposure (Figure 3B). Minimal inflammation in the hypodermis was detected after 24 h, mild inflammation in the dermis/hypodermis was apparent at 72 h, and moderate inflammation was observed throughout all skin layers after 2 weeks. Parakeratosis and hyperkeratosis were also observed at 72 h. Both necrosis and ulceration were detected in biopsies at the 72‐h and 2‐week endpoints, highlighting the need for early therapeutic intervention.

FIGURE 3.

Time course of mechlorethamine hydrochloride (NM) induced skin injury. Clipped and depilated female CD‐1 mice were euthanized at the indicated time points. Each mouse was given two wounds by 15 μl of 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.0) containing 15 (A) or 5 (B) μmol of NM. These NM administration parameters represent the finalized depilatory double‐disc (DDD) model with a modified dose. Columns represent group mean punch biopsy values ± SD, n = 5/group, eleven experimental groups, two control groups, 59 mice total. Naive control group (CTL) average punch biopsy weights were subtracted from the values. *p < 0.05 as determined by one‐way ANOVA with Kruskal‐Wallis test and Dunn's multiple comparisons test.

3.5. NM dose–response analysis

The vesicant dose–response analysis showed that an increase in dose resulted in an increased edematous response from 0.5 to 10 μmol, with a slight decrease in skin weight observed at 15 μmol (Figure 4). Edematous responses from 2.5, 5 10, and 15 μmol of NM doses were significantly different from the naive control (Figure 4). Histological analysis revealed that the 2.5, 5, 10 and 15 μmol doses caused vesication (Figure 5), confirming SPSB severity, while skin weight measurements found no significant difference in edematous response between these groups (Figure 4). A pathological evaluation confirmed that no changes in inflammation were observed between the doses 24 h after exposure, correlating with the unchanged edematous response determined by skin weight measurements. The 5 μmol dose was preferred over the 2.5 μmol dose as it resulted in two‐fold lower data variation (%CV = 23.9% versus 53.1%, respectively).

FIGURE 4.

Mechlorethamine hydrochloride (NM) dose–response evaluation showed 2.5 μmol was the lowest dose to induce significant edema. Punch biopsy weights, offset by those of the naive control group (CTL), of the NM treated area were used to assess skin edema in clipped and depilated female CD‐1 mice 24 h after NM administration. Each dose was administered in 15 μl of 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.0). These NM administration parameters represent the finalized depilatory double‐disc (DDD) model with varied doses. The lowest dose that produced significant edema formation was 2.5 μmol and was therefore selected as the lower limit of the subsequent dose–response study to confirm burn severity with histology. Columns represent group mean punch biopsy values ± SD, n = 4–16/group, six experimental groups, one control group, 54 mice total. *p < 0.05 as determined by one‐way ANOVA with Kruskal‐Wallis test and Dunn's multiple comparisons test.

FIGURE 5.

Mechlorethamine hydrochloride (NM) induced vesication. Each NM dose was administered to clipped and depilated female CD‐1 mice in 15 μl of 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.0). These NM administration parameters represent the finalized depilatory double‐disc (DDD) model with varied doses. The endpoint of the data presented was 24 h after NM administration. Hematoxylin and eosin stained skin samples were examined under a light microscope. Representative images were presented from each group (n = 4, four experimental groups, one control group, 20 mice total). These 20 mice were included in the Figure 4 studies. The 2.5 μmol, 5 μmol, 10 μmol, and 15 μmol groups showed vesication, whereby the dermal‐epidermal separation is shown by arrowheads.

3.6. DDD model validation

The 1% w/v NDH‐4338 QID treatment group demonstrated a significant reduction in skin weight gain after 24 h compared to the untreated NM burn control group (104 ± 26 mg versus 179 ± 25 mg) (Figure 6). The NM burn control and vehicle treated group showed no significant difference (179 ± 25 mg versus 187 ± 52 mg). The anti‐inflammatory effect was therefore attributable to NDH‐4338 and not the vehicle (104 ± 26 mg versus 187 ± 52 mg) (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Prodrug anti‐inflammatory efficacy in mice exposed to mechlorethamine hydrochloride (NM). Clipped and depilated female CD‐1 mice were given two wounds by 15 μl of 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.0) containing 5 μmol of NM. These NM administration parameters represent the finalized depilatory double‐disc (DDD) model. The 1% NDH‐4338 w/v group (NM + 4338) and vehicle only control group (NM + vehicle) received 20 μl of treatment, starting 1 h after vesicant administration, four times over course of 24 h. The untreated vesicant control group received NM only (NM). Punch biopsy weights of the NM treated area, offset by those of the untreated naive control group, were used to assess skin edema. Following the 24‐h treatment course, the 1% NS 4338 group yielded a significantly lower punch biopsy weight than the NM control group. There was no significant difference between the vehicle and NM control groups, indicating that the positive anti‐inflammatory effect observed in the experimental group was attributable to the prodrug and not the formulation vehicle. Columns represent group mean punch biopsy values ± SD, n = 4/group, one experimental group, three control groups, 16 mice total. *p < 0.05 as determined by one‐way ANOVA with Kruskal‐Wallis test and Dunn's multiple comparisons test.

4. DISCUSSION

Optimizing the parameters of an NM animal model is critical to establishing its consistency and usefulness for evaluating pharmacotherapy countermeasures for treating vesicant injury. The highly reproducible DDD model reported here was developed by improving NM contact with the skin surface, minimizing vesicant leakage, ensuring maximal vesicant reactivity with minimal degradation, and investigating the relationships between dose, edematous response, and vesication.

In developing the current model, hair removal methods and NM vehicle selection were investigated to minimize the potential impact on skin barrier function. Hair reduces NM contact with the skin and leads to less sensitive and more variable edematous responses. The current results demonstrate that the use of a depilatory in addition to clipping resulted in an increased edematous response, more reproducible burn wounds, and no observable change in naive control skin morphology and inflammation compared to clipping alone (Figure 1). Skin weight gain increased ~5‐fold in the clipping‐Nair group vs. the clipping‐only group (Figure 1) maintained under the same conditions as reported by Composto et al. 20 Skin weight gain induced by 5 μmol NM under the optimized DDD model conditions is ~2.5‐fold higher than that induced by 20 μmol NM in a vehicle containing 20% water and 80% acetone on a 24‐mm filter disc using clipping‐only for hair removal. 30 Depilation improved contact between the NM dosing solution and skin. Pany et al. investigated the effect of various hair removal techniques (depilatory cream, wet/dry shaving, electric epilation, waxing) on porcine skin barrier function. Dry shaving, electric epilation, and waxing resulted in a moderate reduction in barrier function, whereas depilation cream and wet shaving did not. 31 A subsequent study by the same group using model drugs with various physicochemical properties showed all hair removal methods enhanced skin permeation to varying degrees, with no discernable pattern indicating that any technique was superior to another. 32 However, depilation cream did not enhance the dermal flux of fluconazole (LogP of 0.45 ± 0.84) and thus may not improve the partitioning of hydrophilic NM into the skin. The electric clipping method used in the current studies is distinct from dry shaving as it removes most of the hair shaft without exposing the skin surface directly to the razors. Although the effect of the clipping‐depilatory hair removal treatment on barrier function was not explicitly assessed in this study, it improved contact between the skin surface and NM dosing solution, resulting in consistent burn occurrence.

Although it has been reported that organic solvents such as acetone and DMSO alter skin barrier function, it has been long believed that they were required to produce NM wounds. 25 , 26 It has also been observed that vesication occurs after using DMSO to deliver NM. 22 , 23 , 24 Cuffari et al. suggested NM dermal penetration was required to produce vesication, which could be achieved using DMSO but not acetone or water. 22 Based on this result, they concluded DMSO was required since they achieved vesication not observed in the Composto publication. 22 However, when Jain et al. applied higher doses of NM in acetone, they observed vesication. This suggested that the delivery vehicle solvent and dose of NM administered influences burn quality and vesication. 21 In the current study, no significant difference in skin weight gain was observed between the NM in Water, Acetone Pretreatment + NM in Water, and NM in 20:80 Water:Acetone vehicle groups, demonstrating adequate NM burns could be achieved without acetone. Therefore, acetone was removed from the administration vehicle, eliminating the potentially confounding factor of compromised skin barrier integrity.

5. CONCLUSION

This study presents a highly reproducible and sensitive NM skin burn model that results in vesication without the use of organic solvents that could compromise skin barrier integrity and introduce artifacts in pharmacotherapy studies. A potential limitation of the model is that the punch biopsy extraction procedure requires delicate precision. The DDD model displayed more pharmacological relevance than those published by Composto et al., which did not result in vesication, and Casillas's MEVM, which resulted in ‘through and through’ wounds that were difficult to heal. 14 , 15 , 20 Further, the model validation study showed a significant positive anti‐inflammatory effect using NDH‐4338, confirming that the burns were treatable and adequate for screening pharmacotherapeutic countermeasures.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.L.R. performed animal experiments, data analysis, and wrote manuscript. S.L. performed animal studies, tissue processing, sectioning, and histological examination. D.G. supervised experiments, conducted tissue processing/sectioning/staining, microscopic examination, supervised data analysis, and commented on manuscript revision. J.D.L. supervised the study as well as commented on and approved the manuscript. P.J.S. designed experiments and supervised data analysis and interpretation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All animal studies were conducted under a protocol approved by the Rutgers University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), as described in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health.

Supporting information

Supinfo S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Marianne Polunas and Dr. Michael Goedken for technical assistance. We also thank Dr. Ned Heindel and Dr. Christophe Guillon for providing NDH‐4338. Graphical abstract vectors obtained from Vecteezy.com.

Roldan TL, Li S, Laskin JD, Gao D, Sinko PJ. Depilatory double‐disc mouse model for evaluation of vesicant dermal injury pharmacotherapy countermeasures. Anim Models Exp Med. 2023;6:57‐65. doi: 10.1002/ame2.12304

Funding information

This research was supported by Countermeasures Against Chemical Threats, NIH grant AR055073, and the Parke‐Davis Endowed Chair in Pharmaceutics and Drug Delivery.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request. All relevant data included in supplementary file.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ghabili K, Agutter PS, Ghanei M, Ansarin K, Panahi Y, Shoja MM. Sulfur mustard toxicity: history, chemistry, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2011;41(5):384‐403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Watson AP, Griffin GD. Toxicity of vesicant agents scheduled for destruction by the chemical stockpile disposal program. Environ Health Perspect. 1992;98:259‐280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mangerich A, Debiak M, Birtel M, et al. Sulfur and nitrogen mustards induce characteristic poly(ADP‐ribosyl)ation responses in HaCaT keratinocytes with distinctive cellular consequences. Toxicol Lett. 2016;244:56‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weber GF. DNA damaging drugs. In: Molecular Therapies of Cancer. Springer; 2015:9‐112. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goswami DG, Kumar D, Tewari‐Singh N, et al. Topical nitrogen mustard exposure causes systemic toxic effects in mice. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2015;67(2):161‐170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kadar T, Fishbeine E, Meshulam Y, et al. Treatment of skin injuries induced by sulfur mustard with calmodulin antagonists, using the pig model. J Appl Toxicol. 2000;20(Suppl 1):S133‐S136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Simon GA, Maibach HI. The pig as an experimental animal model of percutaneous permeation in man: qualitative and quantitative observations‐‐an overview. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol. 2000;13(5):229‐234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sullivan TP, Eaglstein WH, Davis SC, Mertz P. The pig as a model for human wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2001;9(2):66‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brinkley FB, Mershon MM, Yaverbaum S, Doxzon BF, Wade JV. The mouse ear model as an in vivo bioassay for the assessment of topical mustard (HD) injury. In Proceedings of the 1989 Medical Defense Bioscience Review. U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense; 1989:595‐602. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Casillas RP, Mitcheltreem LW, Stemler FW. The mouse ear model of cutaneous sulfur mustard injury. Toxicol Methods. 1997;7:381‐397. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Babin MC, Ricketts K, Skvorak JP, Gazaway M, Mitcheltree LW, Casillas RP. Systemic administration of candidate antivesicants to protect against topically applied sulfur mustard in the mouse ear vesicant model (MEVM). J Appl Toxicol. 2000;20(Suppl 1):S141‐S144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Casillas RP, Kiser RC, Truxall JA, et al. Therapeutic approaches to dermatotoxicity by sulfur mustard. I. Modulaton of sulfur mustard‐induced cutaneous injury in the mouse ear vesicant model. J Appl Toxicol. 2000;20(Suppl 1):S145‐S151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Young SC, Fabio KM, Huang MT, et al. Investigation of anticholinergic and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory prodrugs which reduce chemically induced skin inflammation. J Appl Toxicol. 2012;32(2):135‐141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dachir S, Fishbeine E, Meshulam Y, Sahar R, Amir A, Kadar T. Potential anti‐inflammatory treatments against cutaneous sulfur mustard injury using the mouse ear vesicant model. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2002;21(4):197‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dachir S, Cohen M, Fishbeine E, et al. Characterization of acute and long‐term sulfur mustard‐induced skin injuries in hairless Guinea‐pigs using non‐invasive methods. Skin Res Technol. 2010;16(1):114‐124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Graham JS, Chilcott RP, Rice P, Milner SM, Hurst CG, Maliner BI. Wound healing of cutaneous sulfur mustard injuries: strategies for the development of improved therapies. J Burns Wounds. 2005;4:1‐45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johnson RM, Richard R. Partial‐thickness burns: identification and management. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2003;16(4):178‐187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singh V, Devgan L, Bhat S, Milner SM. The pathogenesis of burn wound conversion. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59(1):109‐115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Institute of Medicine Committee on the Survey of the Health Effects of Mustard, G. and Lewisite . In: Pechura CM, Rall DP, eds. Veterans at Risk: The Health Effects of Mustard Gas and Lewisite. National Academies Press (US) Copyright 1993 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Composto GM, Laskin JD, Laskin DL, et al. Mitigation of nitrogen mustard mediated skin injury by a novel indomethacin bifunctional prodrug. Exp Mol Pathol. 2016;100(3):522‐531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jain AK, Tewari‐Singh N, Inturi S, Orlicky DJ, White CW, Agarwal R. Histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation of nitrogen mustard‐induced cutaneous effects in SKH‐1 hairless and C57BL/6 mice. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2014;66(2–3):129‐138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cuffari BJ, Tumu HCR, Pino MA, Billack B. Assessment of the time‐dependent dermatotoxicity of mechlorethamine using the mouse ear vesicant model. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2018;11(4):255‐266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tumu HCR, Cuffari BJ, Pino MA, Palus J, Piętka‐Ottlik M, Billack B. Ebselen oxide attenuates mechlorethamine dermatotoxicity in the mouse ear vesicant model. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2020;43(4):335‐346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lulla A, Reznik S, Trombetta L, Billack B. Use of the mouse ear vesicant model to evaluate the effectiveness of ebselen as a countermeasure to the nitrogen mustard mechlorethamine. J Appl Toxicol. 2014;34(12):1373‐1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Notman R, den Otter WK, Noro MG, Briels WJ, Anwar J. The permeability enhancing mechanism of DMSO in ceramide bilayers simulated by molecular dynamics. Biophys J. 2007;93(6):2056‐2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rissmann R, Oudshoorn MH, Hennink WE, Ponec M, Bouwstra JA. Skin barrier disruption by acetone: observations in a hairless mouse skin model. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301(8):609‐613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guo W, Qiu W, Ao X, et al. Low‐concentration DMSO accelerates skin wound healing by Akt/mTOR‐mediated cell proliferation and migration in diabetic mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177(14):3327‐3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Young S, Fabio K, Guillon C, et al. Peripheral site acetylcholinesterase inhibitors targeting both inflammation and cholinergic dysfunction. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20(9):2987‐2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Loftsson T. Degradation pathways. Drug Stability for Pharmaceutical Scientists. Academic Press; 2014:63‐104. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wahler G, Heck DE, Heindel ND, Laskin DL, Laskin JD, Joseph LB. Antioxidant/stress response in mouse epidermis following exposure to nitrogen mustard. Exp Mol Pathol. 2020;114:104410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pany A, Klang V, Brunner M, Ruthofer J, Schwarz E, Valenta C. Effect of physical and chemical hair removal methods on skin barrier function in vitro: consequences for a hydrophilic model permeant. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2019;32(1):8‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pany A, Klang V, Peinhopf C, Zecevic A, Ruthofer J, Valenta C. Hair removal and bioavailability of chemicals: effect of physicochemical properties of drugs and surfactants on skin permeation ex vivo. Int J Pharm. 2019;567(118477):1‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supinfo S1

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request. All relevant data included in supplementary file.