Abstract

Helicobacter pylori has developed several strategies using its diverse virulence factors to trigger and, at the same time, limit the host’s inflammatory responses in order to establish a chronic infection in the human stomach. One of the virulence factors that has recently received more attention is a member of the Helicobacter outer membrane protein family, the adhesin HopQ, which binds to the human Carcinoembryonic Antigen-related Cell Adhesion Molecules (CEACAMs) on the host cell surface. The HopQ-CEACAM interaction facilitates the translocation of the cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA), an important effector protein of H. pylori, into host cells via the Type IV secretion system (T4SS). Both the T4SS itself and CagA are important virulence factors that are linked to many aberrant host signaling cascades. In the last few years, many studies have emphasized the prerequisite role of the HopQ-CEACAM interaction not only for the adhesion of this pathogen to host cells but also for the regulation of cellular processes. This review summarizes recent findings about the structural characteristics of the HopQ-CEACAM complex and the consequences of this interaction in gastric epithelial cells as well as immune cells. Given that the upregulation of CEACAMs is associated with many H. pylori-induced gastric diseases including gastritis and gastric cancer, these data may enable us to better understand the mechanisms of H. pylori’s pathogenicity.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, CEACAMs, HopQ, CagA translocation, T4SS, NF-κB, gastric, inflammation

1. Introduction

Discovered in 1982 in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration (1), Helicobacter pylori – with its sophisticated mechanisms of pathogenesis – has gained much attention from many research groups over the past decades. Ten years later, in 1994, H. pylori was categorized by the World Health Organization as a class I carcinogen (2). This gram-negative, microaerophilic bacterium infects more than half of the world’s population at different rates depending on geographic location, with developing countries being the most affected regions with an H. pylori prevalence of up to over 80% (3, 4). According to many studies, the main routes of infection are thought to be oral-oral, fecal-oral, and gastro-oral via water or food consumption. Nevertheless, the exact mode of H. pylori transmission is not yet fully understood (5).

In 1992, Pelayo Correa demonstrated the progression of gastric pathologies that can develop as a result of a chronic H. pylori infection of the gastric mucosa. First, chronic gastritis and atrophy are induced, which can later progress to intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and finally gastric adenocarcinoma (6). While all H. pylori individuals develop chronic gastritis, gastric adenocarcinoma only occurs in 1-3% of cases (7). However, H. pylori was estimated to be responsible for 89% of non-cardia gastric cancer cases worldwide (8) and, according to GLOBOCAN 2020, gastric cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality for both sexes combined, accounting for around 1.08 million new cases and 769 000 deaths per year (9).

Over many thousands of years of colonizing the human stomach, H. pylori has diversified into numerous strains possessing various virulence factors (10). These have granted the bacterium the ability not only to directly affect the physiological and molecular processes of gastric epithelial cells but also to interact with the host’s immune cells to promote a strong inflammatory response (11) ( Figure 1 ). One of H. pylori’s best-known virulence factors is the cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA), which is injected by the bacterium into the host cells, leading to the activation of the host immune response and alteration of the host’s cellular processes (12–15). In addition, several bacterial adhesins of the Helicobacter outer membrane protein (Hop) family, including HopZ, BabA, SabA, and OipA, are also found to play a pivotal role in the colonization and pathogenesis of H. pylori (16, 17). Recently, another member of the Hop family, the HopQ adhesin, was reported not only to be involved in bacterial adhesion but also to be essential for the translocation of the effector protein CagA into the host cells by the Type IV secretion system (T4SS), which can aberrantly modify host cell signaling resulting in inflammatory responses. In 2016, HopQ was discovered by Javaheri et al. and Königer et al. to interact with the human Carcinoembryonic Antigen-related Cell Adhesion Molecules (CEACAMs) expressed on the host’s cell surface to facilitate the CagA translocation (14, 18). Since then, the HopQ-CEACAM interaction has been reported to act in a virulence-enhancing manner, possibly contributing to the development of many gastric pathologies. Due to the rising importance of the HopQ-CEACAM interaction, this minireview aims to summarize recent and novel findings of the molecular characterization, function, and consequence of this interaction.

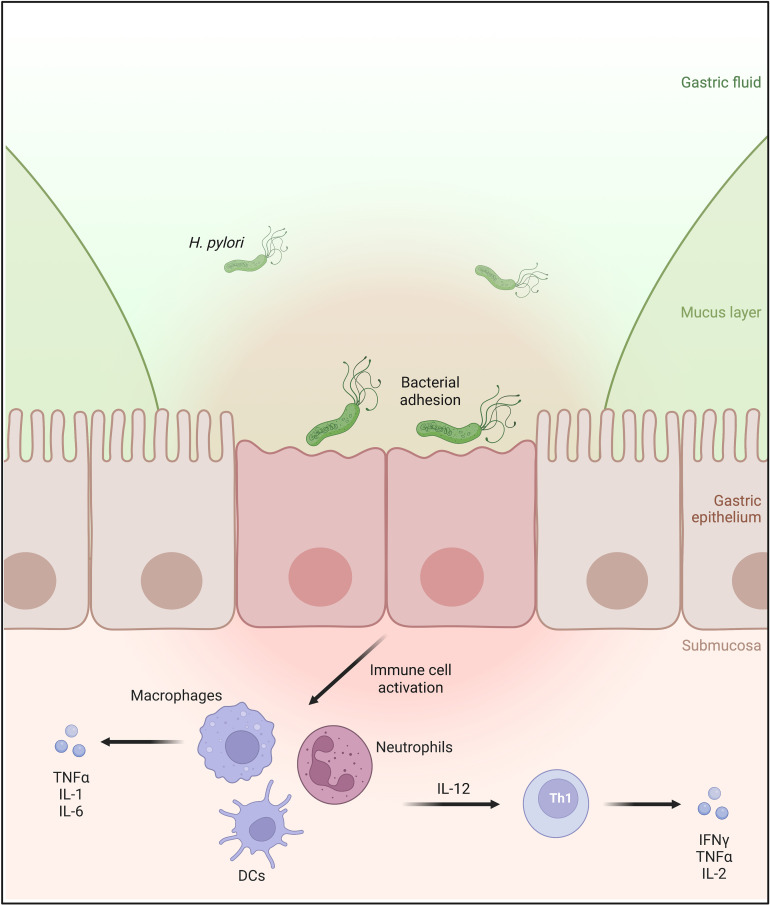

Figure 1.

H. pylori infects the human stomach mucosa by binding to the apical side of the gastric epithelial cells. The infection causes immune cell infiltration of the gastric mucosa. Activated macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils produce interleukin 12 (IL-12), which is involved in the differentiation of naïve T cells into Th1 lymphocytes, leading to the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines IFNγ and TNFα.

2. Helicobacter pylori virulence factors: Type IV secretion system, CagA, HopQ

As a pathogen that colonizes and persists in the human stomach, H. pylori possesses numerous virulence factors. Among those, the T4SS, CagA, and HopQ play a critical role in the bacterium’s pathogenicity. HopQ binds human CEACAM receptors with high affinity and specificity, an interaction necessary for the translocation of CagA into infected cells via the T4SS (14, 18). Importantly, apart from enabling this translocation, the T4SS also seems to regulate the activation of the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling pathway, resulting in the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-8 in host cells (19–22). This is in line with the fact that other bacterial factors such as peptidoglycan, bacterial nucleic acids, heptose-1,7-biphosphate (HBP), and ADP-glycero-β-D-manno-heptose, delivered by the T4SS into host cells, activate the NF-κB signaling (23–26). Similarly, HopQ binding to CEACAMs also acts as an essential regulator of the NF-κB pathway in a T4SS-dependent manner (21, 22) ( Figure 2 ).

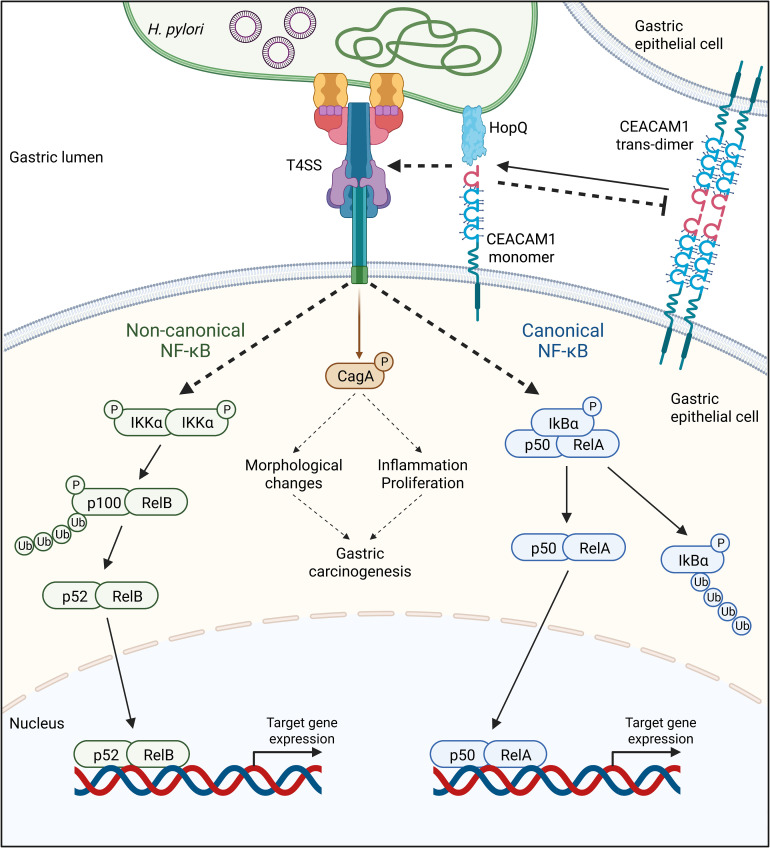

Figure 2.

The adhesin HopQ binds to the N-terminal domain of CEACAM1, disrupting the trans-dimerization of the receptor. The HopQ-CEACAM1 interaction enables the translocation and phosphorylation of CagA and the activation of canonical and non-canonical NF-κB signaling in a Type IV secretion system (T4SS)-dependent fashion. Once activated, the transcription factor complexes p52/RelA of the canonical, as well as p52/RelB of the non-canonical NF-κB pathway, are translocated into the nucleus, activating the expression of target genes.

2.1. Type IV secretion system

Like several other bacteria, H. pylori possesses a T4SS, a pilus-like protein complex spanning both bacterial membranes and reaching into the extracellular space (27). The T4SS in H. pylori is encoded by the cag pathogenicity island (cagPAI), a DNA stretch of approximately 40 kb containing about 30 genes (28) originally derived from a bacteriophage. The core complex of the T4SS is located between H. pylori’s inner and outer membranes and comprises CagM, CagT, CagX, CagY, and Cag3 (29). It is connected to the extracellular pilus, made up of several proteins, including CagI, CagL, CagY, and CagA, which can target integrin α5β1 receptors on gastric epithelial cells (15). Once in contact with the host cell, the T4SS can fulfill its syringe-like function: the injection of H. pylori effector molecules into the host cell. Although also the translocation of peptidoglycan (23) and microbial DNA (24) through the T4SS have been discussed, the translocation of CagA (30) has received most attention (31). While the exact mechanism of this molecular injection remains unclear and goes beyond the scope of this review, its downstream effects in the host cells have been studied in depth.

2.2. Cytotoxin-associated gene A

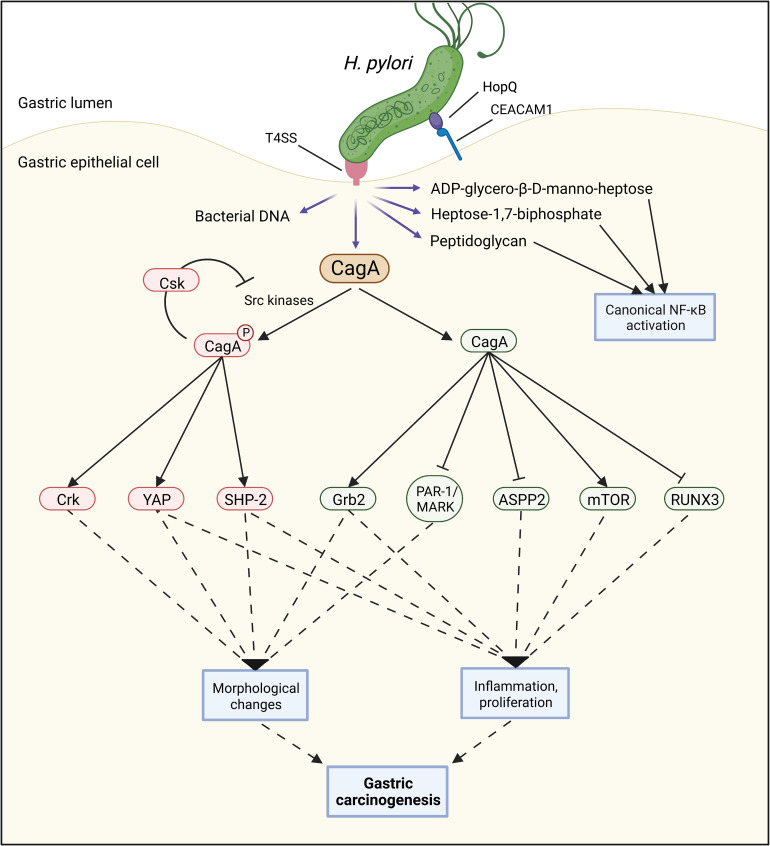

CagA is a protein of 120–140 kDa (32) that is also encoded by the cagPAI (28, 32). After its translocation into the host cell cytoplasm via the T4SS, host kinases of the Src family phosphorylate tyrosine residues located within CagA’s Glu-Pro-Ile-Tyr-Ala (EPIYA) motifs (33). Both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated CagA then interact with a multitude of host proteins, including the Src homology 2 (SH2)-containing tyrosine phosphatase 1 and 2 (SHP-1 and SHP-2) (34, 35), growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2) (36), CT10 regulator of kinase (Crk) (37), and partitioning-defective 1 microtubule affinity-regulating kinase (PAR1/MARK) (38). This triggers numerous cellular pathways, leading to changes in cell morphology, signaling, and function. For instance, the dysregulation of the host cell’s actin cytoskeleton causes cells to elongate and adopt the aberrant so-called “hummingbird” phenotype (30). The cell’s polarity and interaction with adjacent cells are disrupted. At the same time, pro-proliferative, pro-inflammatory, and pro-oncogenic pathways are activated (39) ( Figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

A functional Type 4 secretion system (T4SS) can facilitate the injection of several bacterial components such as bacterial DNA, peptidoglycan, heptose-1,7-biphosphate, ADP-glycero-β-D-manno-heptose, and CagA into the host cell. Once CagA is inside the host cell, both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated CagA can interact with numerous proteins, contributing to several carcinogenic processes including morphological changes, inflammation, and cell proliferation.

In 1995, Blaser et al. reported that patients infected with CagA-proficient H. pylori strains had a higher risk of developing gastric cancer compared to patients infected with CagA-negative strains (40). These findings have since been confirmed and reviewed by Cover (41). It was not until 2008 that Ohnishi et al. were able to causally show that CagA, by aberrantly activating the oncogene SHP-2 in a phosphorylation-dependent manner, promotes gastric adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma development and can therefore be classified as an oncoprotein (42).

Many molecular mechanisms by which CagA contributes to gastric carcinogenesis are now known (43), with more being discovered every year, such as the activation of the oncogenic Yes-Associated Protein (YAP) pathway (44) or the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway (45, 46). Furthermore, CagA inhibits several tumor suppressor proteins, including the runt-related transcription factor 3 (RUNX3) (47) and the apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53-2 (ASPP2) (48). In addition to these direct effects on cancer-promoting signaling pathways, CagA causes inflammation, which is known to be associated with cancer development (49).

CagA is highly imunogenic and induces an inflammatory response in the host organism that goes beyond the effects of H. pylori itself. As early as in 1997, Yamaoka showed a correlation between infection of CagA-proficient H. pylori strains and increased levels of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα (50). Interestingly, at the same time, CagA seems to limit H. pylori’s inflammatory effects. Via an interaction with the C-terminal Src kinase (Csk), CagA inactivates the kinases responsible for its own phosphorylation. As a consequence, CagA-SHP-2 signaling and the subsequent inflammatory pathways are downregulated (51). CagA also downregulates cathepsin C (CtsC), impairing neutrophil activation (52), and induces tolerogenic, i.e., immune-suppressive, dendritic cells (DCs) (53, 54). By reducing the immune response against H. pylori, these mechanisms might support the bacterium’s viability and contribute to its long-term persistence in the human stomach.

In summary, CagA interferes with a multitude of cellular pathways, triggering a number of cellular responses that contribute to inflammation and gastric carcinogenesis. Hence, it is important to understand what enables its translocation via the T4SS.

2.3. HopQ

The H. pylori genome contains about 30 different hop genes, which encode outer membrane proteins (OMPs), some of these serving as bacterial adhesins, such as HopS (named BabA), HopZ, HopE or HopQ (55). This review will focus on HopQ. Two families of hopQ alleles exist: type I hopQ alleles are found more commonly in cag-positive H. pylori strains from patients with peptic ulcer disease, while type II hopQ alleles are found more commonly in cag-negative H. pylori strains from patients without ulcer disease (56).

Nowadays, it is known that HopQ is necessary for the translocation of CagA into host cells (57) and that this is achieved by the binding of HopQ to the human Carcinoembryonic Antigen-related Cell Adhesion Molecules (CEACAMs) 1, 3, 5, and 6 (14, 18). Interestingly, HopQ does not show homology to CEACAM-binding adhesins from other Gram-negative bacteria (14).

3. HopQ-CEACAM interaction

After its identification as a tumor-specific marker for colorectal cancer in 1965 by Gold and Freedman, the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), later classified as CEACAM5, was the first of a wide family of CEACAMs to be discovered as important regulators in carcinogenesis (58). They are mostly expressed on the surface of different cell types such as epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and immune cells (59). Besides their ability to mediate intercellular cell-cell adhesion and communication by forming homophilic and heterophilic cis- or trans-interactions on the cell surface (60, 61), CEACAMs are also important modulators for differentiation (62–64), proliferation (65), apoptosis (66), migration (67, 68), invasion (68), tumor development (69), and immune response (70, 71). Indeed, deregulation of CEACAMs was observed in many cancers such as of CEACAM6 in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemias and early colorectal adenomas, or of CEACAM1 in colorectal and prostate cancer, as well as in melanoma (72–76). CEACAM1, -5, and -6 were also detected to be highly expressed in H. pylori-induced gastritis, precancerous lesions, and gastric cancer, while in a healthy stomach, they were only found at low expression levels, if at all (14, 22). In the human stomach, H. pylori was reported to induce the expression of CEACAMs at the apical side of epithelial cells, although the exact mechanism through which H. pylori modulates the expression of CEACAMs is still unclear. Then, H. pylori employs CEACAMs as receptors for its persistent binding.

Depending on the strain, H. pylori can bind specifically to CEACAM1, -3, -5, and -6 with different affinities, but no binding of the bacterium to CEACAM4, -7, or -8 could be observed (14). Importantly, both Javaheri et al. and Königer et al. showed that the N-terminal domain of CEACAM1 or CEACAM5 was the binding site for H. pylori HopQ. The binding of the bacterium is highly specific to human CEACAMs since no interaction with murine, bovine, or canine CEACAMs was observed. Interestingly, none of H. pylori’s known adhesins such as BabA, SabA, HopZ, and AlpA/B was involved in the binding of the bacterium to CEACAM1 and CEACAM5, but the outer membrane HopQ, which hence is the bona fide adhesin interacting with these receptors (14, 18). Indeed, the HopQ-deficient H. pylori strain P12ΔhopQ was incapable of binding to CEACAM1 and CEACAM5, and gastric cancer cells MKN28 lacking CEACAM did not bind recombinant HopQ (14). The bacterial adhesin was determined to form a strong, dose-dependent complex with CEACAM1 with a 1:1 stoichiometry in solution and in crystals, and a dissociation constant of KD = 296 ± 40 nM (14, 77, 78).

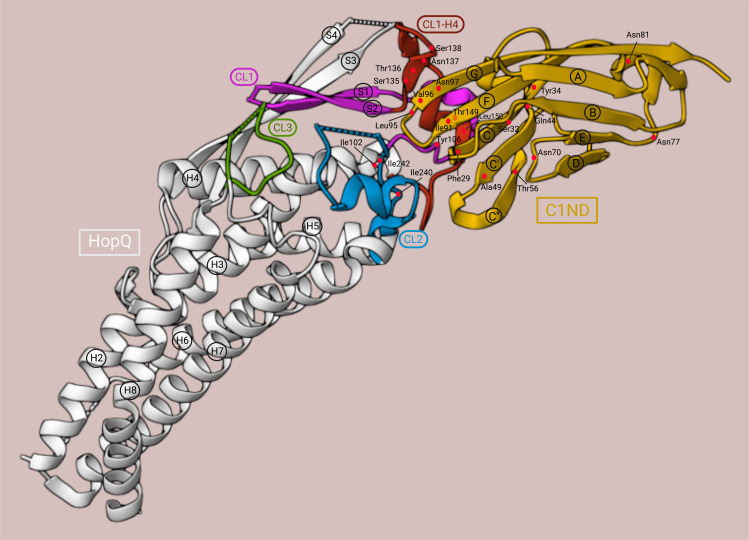

Recently, the X-ray structure of the extracellular domain of HopQ type I (HopQAD-I), which provides the interaction surface with the N-terminal domain of human CEACAM1 (C1ND), was revealed. A conserved 3 + 4-helix bundle topology with four β-strands (S1, S2, S3, and S4) and three disulfide-clasped loops (CL1, CL2, and CL3) was demonstrated as a high-resolution structure, of which each element was proven to contribute to the stability of the HopQ-CEACAM1 interaction (14, 78) ( Figure 4 ). Two of the β-strands, S3 and S4, form the insertion domain (HopQ-ID), which contains binding sites for glycans. HopQ-ID was reported by Javaheri et al. to be crucial for the binding of HopQ to C1ND since the absence of this domain caused a tenfold decrease in binding affinity. However, the insertion domain was later shown to be located quite distantly from the binding interface and to contribute only indirectly to the C1ND binding by interacting with S1 and S2 to support the ordering of the CL1 and CL1-H4 (the loop connecting CL1 to Helix 4) loops into their binding conformation (77, 78). Clustering together, the CL1, CL1-H4, and CL2 loops establish protein-protein contact with the GFCC’C” interaction surface of the immunoglobulin-like (IgV) domain of C1ND in a glycan-independent manner (14, 78). Three N-linked glycosylation sites are anticipated to be present in the CEACAM1IgV domain: Asn70CEACAM1, Asn77CEACAM1, and Asn81CEACAM1. They were found to point away from HopQ-ID, and thus have no significant impact on the interaction surface (77, 78). In fact, under enzymatic deglycosylation conditions, both CEACAM1IgV and CEACAM1IgC2 exhibited no major difference in binding affinity compared to the glycosylated CEACAM1IgV (14, 77).

Figure 4.

3D structure of the HopQAD-I-C1ND interaction. C1ND, yellow; HopQAD-I, white; CL1, magenta; CL1-H4, red; CL2, blue; CL3, green. The residues are depicted as red dots. This illustration was adapted from the crystal structure representation generated by Moonens et al. (78) using RCSB Protein Data Bank (79) (PDB ID: 6GBG, www.rcsb.org) and Mol* (80) (www.molstar.org).

In contrast to the mechanism observed for other bacterial proteins interacting with CEACAM receptors, HopQ-CEACAM1 binding is driven by a protein-protein interaction featuring three H-bonds between Gln44CEACAM1, Tyr34CEACAM1, and Ser32CEACAM1 with Thr149HopQ in the CL1-H4 helix; five H-bonds between the strand G of C1ND and Ser135HopQ, Thr136HopQ, Asn137HopQ, and Ser138HopQ in the CL1-H4 loop; and one H-bond between Thr56CEACAM1 in the strand C” and Tyr106HopQ in the CL1. Additionally, the protein-protein contact is supported by hydrophobic bonds between the hydrophobic amino acids Phe29CEACAM1, Ile91CEACAM1, and Leu95CEACAM1 and the hydrophobic platform created by Ile102HopQ in CL1-H3, Ile240HopQ, and Ile242HopQ in CL2, and Leu150HopQ in CL1-H4 (78). Notably, in a directed point mutation analysis, the mutation of Leu150HopQ to Arg abolished the binding of HopQAD-I to C1ND completely. Moreover, the steric clashes in the interaction surface created by the mutation of Thr56CEACAM1 to Lys and Ala49CEACAM1 to Leu reduced the binding either only by 20% or in the same manner as the ΔhopQ mutant strain, respectively. This showed the importance of Leu150HopQ and Ala49CEACAM1 for the interaction between C1ND and CL1 (78).

CL1, anchored by Cys103HopQ and Cys132HopQ, was also proven to be a substantial component of the CEACAM1 binding site since Cys103Ser and Cys132Ser mutant strains did not show binding to CEACAM1 at the level observed for ΔhopQ mutant strains. Of note, the HopQ expression was maintained at the same level in the Cys103Ser mutant strain as in the wild-type strain, indicating that the lack of binding was not the result of a reduced expression of the adhesin but the loss of interaction with CEACAM1 on the interaction surface. In contrast, CL2 (anchored by Cys238HopQ and Cys270HopQ) and CL3 (anchored by Cys362HopQ and Cys385HopQ) mutants had no defects on CEACAM1 binding. As observed with the HopQAD-I-CEACAM1 interaction, the loss of the disulfide bond of CL1 was also demonstrated to be crucial in HopQAD-I binding to CEACAM5 (81). CL1 and CL1-H4 loops were also reported to be disordered in the unbound HopQAD-I; these loops were rearranged and became ordered only until they bound to C1ND through a coupled folding and binding mechanism (77, 78).

Using differential scanning fluorimetry, HopQ alone was measured to have a melting temperature (Tm) of approximately 45°C between pH 5.5 and pH 7.0, and thus to be less stable than the HopQ-CEACAM1 complex, which not only had a Tm of about 50°C over the same pH range but also remained intact even at pH 3.0 (77). These results provide evidence, that, by binding to the N-terminal IgV domain of CEACAM1, HopQ type I enters a more stable structure than its unbound state. The X-ray structure of the extracellular domain of HopQ type II (HopQAD-II) revealed that HopQAD-I and HopQAD-II target the same epitope on the GFCC’C” sheet of C1ND. Although HopQAD-II provides seven H-bonds less than HopQAD-I to the interaction surface with C1ND, it can bind C1ND with a sixfold higher affinity than that of the HopQAD-I-C1ND interaction. Thus, HopQAD-II binding to CEACAM1 is rather hydrophobic and entropically driven, while the HopQAD-I-C1ND interaction is enthalpically driven and entropically disfavored (78).

In C1ND, a β-sandwich fold with nine anti-parallel β-sheets is arranged in two opposing β-sheets: ABED, which is used by CEACAM1 to form cis-oligomerization on the same cell, and GFCC’C”, which is involved in the cross-cell trans-dimerization interface (82, 83). As discussed before, the non-glycosylated GFCC’C” surface is also in direct contact with HopQAD-I, assembling H-bonds and hydrophobic bonds with CL1, CL1-H4 and CL2 (78). Indeed, a total of 26 residues were found to be shared by the interface that C1ND uses for HopQAD-I binding and trans-dimerization, including Phe29CEACAM1, Gln44CEACAM1, Ile91CEACAM1, Leu95CEACAM1, Val96CEACAM1, Asn97CEACAM1 (77). While the mutation of Phe29CEACAM1, Gln44CEACAM1, Val96CEACAM1, and especially Asn97CEACAM1 to Ala influenced the dimerization of CEACAM1 remarkably – in the case of Asn97Ala, dimeric CEACAM1 was even converted into monomers –, these mutations only caused a modest decrease in the binding energy with HopQ. This indicates that the binding energy with HopQ is distributed over many residues (77). Moreover, H. pylori can not only exploit the GFCC’C” interface of CEACAMs but also disrupt its trans-dimerization upon binding (77, 78). CEACAM1 was shown to be present as trans-dimer in solution, yet upon infection with H. pylori wild-type but not ΔhopQ mutant strain, the cross-linking efficiency of CEACAM1 is attenuated. Thus, in the presence of H. pylori, the equilibrium between dimeric and monomeric CEACAM1 is shifted to monomeric CEACAM1 to favor the formation of the HopQ-CEACAM1 complex (78).

4. Downstream effects of HopQ-CEACAM binding

An important consequence of the HopQ-CEACAM interaction is the T4SS-mediated CagA translocation and phosphorylation in the host cells. Nearly a decade ago, CagA translocation was for the first time reported to be HopQ-dependent by Belogolova et al. Out of 19 genes, which were found by screening transposon mutant library to alter T4SS-dependent activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway and secretion of IL-8, HopQ was identified as an important factor supporting the pro-inflammatory response and the CagA translocation (57). Nevertheless, it was not until 2016 that the binding partners of HopQ, CEACAMs, and the dependence of the CagA translocation and phosphorylation on the HopQ-CEACAM interaction were described by Javaheri et al. and Königer et al. This shed light on how H. pylori can utilize different virulence factors to interact with the host cells and thereby enhance its pathogenicity.

While the lack of HopQ leads to an alteration of cagPAI-dependent CagA translocation and a reduction of IL-8 secretion (14, 57), the impact on these events appeared to depend on different CEACAMs and cell lines. In gastric cell lines expressing high levels of CEACAM1, -5, and -6 such as AGS, KatoIII, and MKN45, CagA can be translocated into the host cells and successfully phosphorylated. Of note, the elevated expression levels of CEACAM5 and -6 were reported to foster CagA translocation even to a larger extent. In contrast, in cell lines expressing little or none of these CEACAMs, including MKN28, Hela, and HEK293, no CagA translocation could be observed (18). However, while the single knockdown of one of CEACAM1, -5, and -6 in AGS cells was not able to revoke CagA translocation, the simultaneous knockdown of all present CEACAMs in this cell line abolished CagA translocation to a similar extent as is observed when using the H. pylori ΔhopQ mutant strain for infection. This indicates a functional redundancy of CEACAMs in AGS cells. Moreover, the fact that the altered HopQ-CEACAM interaction only reduces the CagA translocation into AGS cells by 50% suggests that another receptor on AGS cells aside from CEACAMs or another H. pylori adhesin aside from HopQ might also be involved in CagA translocation (18). Conversely, in KatoIII cells, the triple knockdown of CEACAM1, -5, and -6, like the lack of HopQ, completely abrogated CagA translocation, indicating that in these cells, CagA translocation seems to be enabled mostly by the HopQ-CEACAM interaction (84).

Integrin is one of the alternative receptors expressed on gastric epithelial cells reported to be engaged for the T4SS-mediated CagA translocation (85). Previously, many studies on different cell lines have been focusing on the functional role of integrin in CagA translocation and signal transduction upon H. pylori binding. Like CEACAMs, integrin acts in different manners depending on the cell line. In AGS and KatoIII cells, the single knockout of integrin β1, the double knockout of integrin β1β4 and αvβ4, and the triple knockout of all αβ integrins had no major impact on CagA translocation and the induction of IL-8 expression, in contrast to the abrogation of CEACAMs expression (84). Additionally, the absence of integrin-linked kinase (ILK), which interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of integrin β1 to mediate signaling from the extracellular matrix to the intracellular compartment (86), was also not essential for CagA translocation (21, 84). Thus, it was concluded that neither integrin interaction with the T4SS nor integrin signaling but HopQ-CEACAM interaction is required for CagA translocation into AGS and KatoIII cells (84). In another study using AZ-521 cells infected with a T4SS-defective strain, the overexpression of CEACAM1 and -5, but not CEACAM6 or integrin, was able to compensate for the insufficiency of the T4SS for CagA translocation (87). However, the fact that this cell line was reported to be a misidentified duodenal cancer cell line raises questions about the usefulness of using AZ-521 cells for studying the effects of H. pylori in the stomach.

Upon H. pylori-induced inflammation, several signaling pathways are activated including the canonical and non-canonical NF-κB (19–21, 88). While the activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway involves the phosphorylation and proteasomal degradation of IκBα, leading to the translocation of the heterodimer p50/RelA into the nucleus (89, 90), the activation of the non-canonical NF-κB pathway leads to the phosphorylation of IKKα, the phosphorylation and degradation of p100 to p52, and the translocation of the heterodimer p52/RelB into the nucleus (91–93) ( Figure 2 ). Various studies have shown that both NF-κB pathways are mainly T4SS-dependent and CagA-independent (19–22). Indeed, in NCI-N87 and AGS cells infected with H. pylori lacking a functional T4SS, the phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα did not occur, in contrast to cells infected with the ΔcagA mutant strain (21). Similarly, the absence of CagE, a protein important for the T4SS pilus formation (94), but not CagA strongly reduced the processing of p100 to p52 in the non-canonical NF-κB pathway (22, 88).

Furthermore, the single knockdown, as well as the double knockdown of integrin α5 and/or β1, and the knockdown of ILK did not influence the activation of the canonical NF-κB signaling, showing that integrin-mediated pathway is dispensable for NF-κB activation during H. pylori infection (21, 84). In contrast, the HopQ-CEACAM interaction is a prerequisite for the activation of canonical and non-canonical NF-κB pathways. In gastric cells expressing high levels of CEACAMs, infection with the ΔhopQ mutant strain induced the activation of both pathways less effectively than wild-type H. pylori strains (21, 22, 95). However, NUGC-4 and SNU1 or Hela cells, expressing low levels of CEACAM1 or no CEACAMs, respectively, showed no significant changes in IL-8 secretion as well as the processing of p100 to p52 upon infection with HopQ-deficient H. pylori, indicating that efficient binding of HopQ to CEACAMs is necessary for the activation of these carcinogenic pathways (21, 22). Notably, a correlation between the upregulation of CEACAM1 and the activation of the non-canonical NF-κB pathway in H. pylori-induced gastritis, intestinal-type, and diffuse-type gastric tumors was also reported (22), strongly indicating a vital contribution of CEACAM1 to the pathogenic hallmarks of H. pylori infection.

Interestingly, the HopQ-CEACAM interaction is not only pivotal for the regulation of the epithelial cell response but also appears to modulate the immune response. During infection, H. pylori induces the infiltration of several immune cells including macrophages, DCs, neutrophils, and T cells (1, 96–99) ( Figure 1 ). In human neutrophils expressing CEACAM1 and CEACAM6, CagA translocation and phosphorylation are facilitated effectively in a HopQ-dependent manner, whereas macrophages and DCs with low expression levels of these CEACAMs only allow low levels of CagA translocation and phosphorylation in a HopQ-independent manner (100). In addition, in murine neutrophils expressing human CEACAMs, thus exhibiting a functional HopQ-CEACAM interaction, infection with H. pylori infection increases the production of the proinflammatory chemokine MIP-1α compared to wild-type murine neutrophils. Conversely, upon infection, murine macrophages expressing human CEACAMs show significantly lower expression levels of CXCL1 and CCL2 than wild-type murine macrophages. This indicates the critical role of functional HopQ-CEACAM interaction in modulating chemokine secretion in different myeloid cells. In addition, by exploiting different CEACAMs, H. pylori can also regulate the oxidative burst of neutrophils and phagocytosis to support its intracellular survival in a HopQ-dependent fashion (100). The HopQ-CEACAM interaction can not only influence the activity of distinct myeloid cells in different ways but also affect the functions of natural killer (NK) cells and T cells. In activated CD4+ T cells expressing high levels of CEACAM1, IFNγ secretion is inhibited during infection with wild-type H. pylori in a HopQ-dependent manner. Similarly, the cytotoxic activity of activated CD8+ T cells and NK cells with high levels of CEACAM1 is also impeded during infection with the wild-type strain compared to ΔhopQ strain (101). These data suggest that H. pylori, and specifically HopQ, might be able to limit the inflammation caused by the bacterium’s infection, thereby possibly supporting lifelong persistence in the human stomach. The details of the bacterium’s immune evasion strategies have been reviewed before (102).

5. Discussion and outlook

Causing hundreds of thousands of premature deaths each year, H. pylori-associated diseases are a relevant factor for morbidity and mortality around the globe. However, given that about half of the world’s population is infected (3) and only relatively few individuals develop severe pathologies (103), it is clear that not all infections are equal. It is known that H. pylori’s oncoprotein CagA is one of the most important virulence factors contributing to the bacterium’s pathogenicity. The translocation of CagA via the T4SS and its subsequent interference with cellular processes are detrimental to gastric epithelial cells and explains a substantial part of H. pylori’s effects on inflammation and carcinogenesis (41, 104). CagA translocation requires the binding of H. pylori’s outer membrane protein HopQ to CEACAM receptors expressed on human gastric cells, and this interaction leads to different molecular changes, discussed in detail above. Although research is emerging on this matter, some questions are still unanswered.

As mentioned before, by binding to the trans-dimerization interface in the N-terminal domain of CEACAM1, HopQ can interfere with its monomer/dimer equilibrium (78). While many studies reported that the binding of SHP-1/2 to the tyrosine-phosphorylated Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) of the CEACAM1-L variant supports the inhibitory effects of the ITIM on colon, prostate, and breast tumor cell growth (105–109), the role of ITIM and SHP-1/2 upon H. pylori infection of the gastric epithelial cells has not yet been studied intensively. Since the trans- or cis-dimerization of CEACAM1-L and the clustering of ITIM are required for SHP-1/2 to be sequestered to the ITIM domain (110), the disruption of the trans-dimerization of CEACAM1 in the presence of H. pylori HopQ leads to the release of SHP-1/2 from ITIM, possibly altering the downstream signaling transduction of CEACAM1, as proposed by Moonens et al. (78). However, ITIM seems to be dispensable for CagA translocation and phosphorylation, as the overexpression of CEACAM1-4S or CEACAM1-4L in MKN28 cells infected with H. pylori results in similar levels of phosphorylated CagA (78). Still, this needs to be confirmed in independent models and non-cancer cells. The fact that CagA also interacts with SHP-2 (34, 42) contributes even further to the complexity of this protein interaction network. Moreover, not only downstream but also upstream signaling of CEACAM1 upon H. pylori infection remains unknown. Considering the correlation between H. pylori infection and the upregulation of CEACAM1 in gastritis, pre-cancerous, and gastric cancer tissues (14, 22), the mechanisms through which H. pylori regulates CEACAM1 expression and signaling represent an interesting topic for future research.

Although integrin α5β1 was suggested by Kwok et al. to be a receptor required for T4SS to inject CagA into host cells (85), more recent studies have shown that integrins and their downstream signaling are not essential for the translocation and phosphorylation of CagA, in contrast to CEACAMs binding to HopQ (21, 84). It needs to be clarified whether the interaction between integrins and T4SS is compulsory for CagA translocation into host cells and, if at all, whether integrins and CEACAM receptors work in cooperation to support the tethering of T4SS onto host cells and the subsequent CagA translocation. It is also important to mention that the binding of H. pylori to CEACAMs during infection occurs mostly on the apical side of gastric epithelial cells (14, 18), while integrins, as receptors for cell-cell adhesion and cell attachment to the extracellular matrix (111, 112), are located at the basolateral side. The spatial difference between these two receptors raises questions about if and how H. pylori can interact with both receptors, and how they may interact with each other. In KatoIII cells, the triple knockout of CEACAM1, -5, and -6 was reported to have no significant influence on the intrinsic expression of αv and β integrin. However, the triple knockdown of αvβ1, αvβ4, and β1β4 integrins in these cells resulted in a lower expression and recruitment of CEACAM5 to the binding surface with H. pylori compared to wild-types cells (84). Furthermore, Wessler and Backert suggested a new model, in which integrin-dependent T4SS activation for CagA translocation is facilitated through another virulence factor, the serine protease HtrA, which hijacks the tight junctions and adherence junctions between cells, enabling H. pylori’s transmigration to the basolateral side of polarized epithelial cells (113). Nevertheless, given the importance of CEACAM receptors, there are still unclarities about the role of integrin and the correlation between this receptor and CEACAMs in CagA translocation.

A recent study showed that recombinant HopQ coupled with fluorochromes was able to detect CEACAM-expressing colorectal tumors and metastases in a mouse model (114), hinting that this interaction might be exploitable for diagnostic purposes. Apart from that, impairing the HopQ-CEACAM interaction might represent a new approach for H. pylori prevention and treatment. Besides hygiene measures, no effective H. pylori prevention strategies exist. Moreover, while antibiotic treatment is still mostly efficacious, it has several limitations including costs, low compliance due to side effects and relatively long duration (10-14 days according to recent guidelines), and, most importantly, the risk of antimicrobial resistance. The inhibition of CEACAMs binding to H. pylori’s HopQ might impair the mechanism which makes the infection so hazardous. This could be achieved either by inhibiting the upregulation of CEACAMs, or by blocking the interaction of H. pylori to CEACAM receptors expressed on the host’s cell surface with, for example, competitive CEACAM-binders. Another strategy is to target the essential structural components of the HopQ-CEACAM complex. This offers new possibilities for prevention and treatment options targeted especially at those H. pylori infections with the greatest risk for gastric pathologies.

Author contributions

QN and LS wrote the manuscript and conducted experimental work on the topic. RM-L and MG supervised the work and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

Prof. Bernhard Singer, UKE Essen, provided numerous CEACAM-related tools and reagents for ongoing research projects. To our great dismay, Bernhard Singer passed away suddenly and unexpectedly in January 2023. With him, we lost a wonderful person and a great scientist and colleague, who has shaped the CEACAM field over the past decades like no other. Much of our work would not have been possible without his generous support and enthusiasm. We would like to dedicate this review to Bernhard’s memory and hope that many of his students and colleagues will continue his work.

Funding Statement

DFG GE 2042-17-1 to MG.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet (1984) 1:1311–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cancer, I.A.f.R.o . Schistosomes, liver flukes and helicobacter pylori (IARC Lyon). IARC Monographs on the Evalutaion of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (1994) 61:1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, et al. Global prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology (2017) 153:420–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zamani M, Ebrahimtabar F, Zamani V, Miller WH, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Shokri-Shirvani J, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the worldwide prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther (2018) 47:868–76. doi: 10.1111/apt.14561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown LM. Helicobacter pylori: epidemiology and routes of transmission. Epidemiol Rev (2000) 22:283–97. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process–first American cancer society award lecture on cancer epidemiology and prevention. Cancer Res (1992) 52:6735–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wroblewski LE, Peek RM, Jr. Targeted disruption of the epithelial-barrier by helicobacter pylori. Cell Commun Signal (2011) 9:29. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-9-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Plummer M, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Forman D, de Martel C. Global burden of gastric cancer attributable to helicobacter pylori. Int J Cancer (2015) 136:487–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Parkin DM, Pineros M, Znaor A, et al. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int J Cancer (2021) 149(4):778–89. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Linz B, Balloux F, Moodley Y, Manica A, Liu H, Roumagnac P, et al. An African origin for the intimate association between humans and helicobacter pylori. Nature (2007) 445:915–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ishaq S, Nunn L. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: a state of the art review. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench (2015) 8:S6–S14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Odenbreit S, Puls J, Sedlmaier B, Gerland E, Fischer W, Haas R. Translocation of helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science (2000) 287:1497–500. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Palframan SL, Kwok T, Gabriel K. Vacuolating cytotoxin a (VacA), a key toxin for helicobacter pylori pathogenesis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol (2012) 2:92. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Javaheri A, Kruse T, Moonens K, Mejias-Luque R, Debraekeleer A, Asche CI, et al. Helicobacter pylori adhesin HopQ engages in a virulence-enhancing interaction with human CEACAMs. Nat Microbiol (2016) 2:16189. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Backert S, Tegtmeyer N. Type IV secretion and signal transduction of helicobacter pylori CagA through interactions with host cell receptors. . Toxins (Basel) (2017) 9(4):115. doi: 10.3390/toxins9040115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Salama NR, Hartung ML, Muller A. Life in the human stomach: persistence strategies of the bacterial pathogen helicobacter pylori. Nat Rev Microbiol (2013) 11:385–99. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kalali B, Mejias-Luque R, Javaheri A, Gerhard M. H. pylori virulence factors: influence on immune system and pathology. Mediators Inflammation (2014) 426309. doi: 10.1155/2014/426309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koniger V, Holsten L, Harrison U, Busch B, Loell E, Zhao Q, et al. Helicobacter pylori exploits human CEACAMs via HopQ for adherence and translocation of CagA. Nat Microbiol (2016) 2:16188. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schweitzer K, Sokolova O, Bozko PM, Naumann M. Helicobacter pylori induces NF-kappaB independent of CagA. EMBO Rep (2010) 11:10–1. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sokolova O, Borgmann M, Rieke C, Schweitzer K, Rothkotter HJ, Naumann M. Helicobacter pylori induces type 4 secretion system-dependent, but CagA-independent activation of IkappaBs and NF-kappaB/RelA at early time points. Int J Med Microbiol (2013) 303:548–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Feige MH, Sokolova O, Pickenhahn A, Maubach G, Naumann M. HopQ impacts the integrin alpha5beta1-independent NF-kappaB activation by helicobacter pylori in CEACAM expressing cells. Int J Med Microbiol (2018) 308:527–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Taxauer K, Hamway Y, Ralser A, Dietl A, Mink K, Vieth M, et al. Engagement of CEACAM1 by helicobacterpylori HopQ is important for the activation of non-canonical NF-kappaB in gastric epithelial cells. Microorganisms (2021) 9(8):1748. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9081748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Viala J, Chaput C, Boneca IG, Cardona A, Girardin SE, Moran AP, et al. Nod1 responds to peptidoglycan delivered by the helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island. Nat Immunol (2004) 5:1166–74. doi: 10.1038/ni1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Varga MG, Shaffer CL, Sierra JC, Suarez G, Piazuelo MB, Whitaker ME, et al. Pathogenic helicobacter pylori strains translocate DNA and activate TLR9 via the cancer-associated cag type IV secretion system. Oncogene (2016) 35:6262–9. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gall A, Gaudet RG, Gray-Owen SD, Salama NR. TIFA signaling in gastric epithelial cells initiates the cag type 4 secretion system-dependent innate immune response to helicobacter pylori infection. mBio (2017) 8(4):e01168–17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01168-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pfannkuch L, Hurwitz R, Traulsen J, Sigulla J, Poeschke M, Matzner L, et al. ADP heptose, a novel pathogen-associated molecular pattern identified in helicobacter pylori. FASEB J (2019) 33:9087–99. doi: 10.1096/fj.201802555R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Backert S, Tegtmeyer N, Fischer W. Composition, structure and function of the helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island encoded type IV secretion system. Future Microbiol (2015) 10:955–65. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Censini S, Lange C, Xiang Z, Crabtree JE, Ghiara P, Borodovsky M, et al. Cag, a pathogenicity island of helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (1996) 93:14648–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Frick-Cheng AE, Pyburn TM, Voss BJ, McDonald WH, Ohi MD, Cover TL. Molecular and structural analysis of the helicobacter pylori cag type IV secretion system core complex. mBio (2016) 7:e02001–02015. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02001-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Segal ED, Cha J, Lo J, Falkow S, Tompkins LS. Altered states: involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (1999) 96:14559–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Backert S, Blaser MJ. The role of CagA in the gastric biology of helicobacter pylori. Cancer Res (2016) 76:4028–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cover TL, Glupczynski Y, Lage AP, Burette A, Tummuru MK, Perez-Perez GI, et al. Serologic detection of infection with cagA+ helicobacter pylori strains. J Clin Microbiol (1995) 33:1496–500. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1496-1500.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stein M, Bagnoli F, Halenbeck R, Rappuoli R, Fantl WJ, Covacci A. C-Src/Lyn kinases activate helicobacter pylori CagA through tyrosine phosphorylation of the EPIYA motifs. Mol Microbiol (2002) 43:971–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02781.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Higashi H, Tsutsumi R, Muto S, Sugiyama T, Azuma T, Asaka M, et al. SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase as an intracellular target of helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Science (2002) 295:683–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1067147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Selbach M, Paul FE, Brandt S, Guye P, Daumke O, Backert S, et al. Host cell interactome of tyrosine-phosphorylated bacterial proteins. Cell Host Microbe (2009) 5:397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mimuro H, Suzuki T, Tanaka J, Asahi M, Haas R, Sasakawa C. Grb2 is a key mediator of helicobacter pylori CagA protein activities. Mol Cell (2002) 10:745–55. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00681-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Suzuki M, Mimuro H, Suzuki T, Park M, Yamamoto T, Sasakawa C. Interaction of CagA with crk plays an important role in helicobacter pylori-induced loss of gastric epithelial cell adhesion. J Exp Med (2005) 202:1235–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nesic D, Miller MC, Quinkert ZT, Stein M, Chait BT, Stebbins CE. Helicobacter pylori CagA inhibits PAR1-MARK family kinases by mimicking host substrates. Nat Struct Mol Biol (2010) 17:130–2. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Backert S, Tegtmeyer N, Selbach M. The versatility of helicobacter pylori CagA effector protein functions: The master key hypothesis. Helicobacter (2010) 15:163–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00759.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez GI, Kleanthous H, Cover TL, Peek RM, Chyou PH, et al. Infection with helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res (1995) 55:2111–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cover TL. Helicobacter pylori diversity and gastric cancer risk. mBio (2016) 7:e01869–01815. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01869-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ohnishi N, Yuasa H, Tanaka S, Sawa H, Miura M, Matsui A, et al. Transgenic expression of helicobacter pylori CagA induces gastrointestinal and hematopoietic neoplasms in mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2008) 105:1003–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711183105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hatakeyama M. Helicobacter pylori CagA and gastric cancer: a paradigm for hit-and-run carcinogenesis. Cell Host Microbe (2014) 15:306–16. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li N, Feng Y, Hu Y, He C, Xie C, Ouyang Y, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA promotes epithelial mesenchymal transition in gastric carcinogenesis via triggering oncogenic YAP pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res (2018) 37:280. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0962-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li N, Tang B, Jia YP, Zhu P, Zhuang Y, Fang Y, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein negatively regulates autophagy and promotes inflammatory response via c-Met-PI3K/Akt-mTOR signaling pathway. Front Cell Infect Microbiol (2017) 7:417. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Feng GJ, Chen Y, Li K. Helicobacter pylori promote inflammation and host defense through the cagA-dependent activation of mTORC1. J Cell Physiol (2020) 235:10094–108. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tsang YH, Lamb A, Romero-Gallo J, Huang B, Ito K, Peek RM, Jr., et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA targets gastric tumor suppressor RUNX3 for proteasome-mediated degradation. Oncogene (2010) 29:5643–50. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Buti L, Spooner E, van der Veen AG, Rappuoli R, Covacci A, Ploegh HL. Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin-associated gene a (CagA) subverts the apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53 (ASPP2) tumor suppressor pathway of the host. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2011) 108:9238–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106200108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature (2002) 420:860–7. doi: 10.1038/nature01322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yamaoka Y. Mechanisms of disease: Helicobacter pylori virulence factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2010) 7:629–41. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tsutsumi R, Higashi H, Higuchi M, Okada M, Hatakeyama M. Attenuation of helicobacter pylori CagA x SHP-2 signaling by interaction between CagA and c-terminal src kinase. J Biol Chem (2003) 278:3664–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208155200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liu YG, Teng YS, Cheng P, Kong H, Lv YP, Mao FY, et al. Abrogation of cathepsin c by helicobacter pylori impairs neutrophil activation to promote gastric infection. FASEB J (2019) 33:5018–33. doi: 10.1096/fj.201802016RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tanaka H, Yoshida M, Nishiumi S, Ohnishi N, Kobayashi K, Yamamoto K, et al. The CagA protein of helicobacter pylori suppresses the functions of dendritic cell in mice. Arch Biochem Biophys (2010) 498:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kaebisch R, Mejias-Luque R, Prinz C, Gerhard M. Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin-associated gene a impairs human dendritic cell maturation and function through IL-10-mediated activation of STAT3. J Immunol (2014) 192:316–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Alm RA, Bina J, Andrews BM, Doig P, Hancock RE, Trust TJ. Comparative genomics of helicobacter pylori: analysis of the outer membrane protein families. Infect Immun (2000) 68:4155–68. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.7.4155-4168.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cao P, Cover TL. Two different families of hopQ alleles in helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol (2002) 40:4504–11. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4504-4511.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Belogolova E, Bauer B, Pompaiah M, Asakura H, Brinkman V, Ertl C, et al. Helicobacter pylori outer membrane protein HopQ identified as a novel T4SS-associated virulence factor. Cell Microbiol (2013) 15:1896–912. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gold P, Freedman SO. Specific carcinoembryonic antigens of the human digestive system. . J Exp Med (1965) 122:467–81. doi: 10.1084/jem.122.3.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Prall F, Nollau P, Neumaier M, Haubeck HD, Drzeniek Z, Helmchen U, et al. CD66a (BGP), an adhesion molecule of the carcinoembryonic antigen family, is expressed in epithelium, endothelium, and myeloid cells in a wide range of normal human tissues. J Histochem Cytochem (1996) 44:35–41. doi: 10.1177/44.1.8543780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Oikawa S, Inuzuka C, Kuroki M, Arakawa F, Matsuoka Y, Kosaki G, et al. A specific heterotypic cell adhesion activity between members of carcinoembryonic antigen family, W272 and NCA, is mediated by n-domains. J Biol Chem (1991) 266:7995–8001. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)92930-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Teixeira AM, Fawcett J, Simmons DL, Watt SM. The n-domain of the biliary glycoprotein (BGP) adhesion molecule mediates homotypic binding: domain interactions and epitope analysis of BGPc. Blood (1994) 84:211–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.V84.1.211.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Eidelman FJ, Fuks A, DeMarte L, Taheri M, Stanners CP. Human carcinoembryonic antigen, an intercellular adhesion molecule, blocks fusion and differentiation of rat myoblasts. J Cell Biol (1993) 123:467–75. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.2.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ordonez C, Screaton RA, Ilantzis C, Stanners CP. Human carcinoembryonic antigen functions as a general inhibitor of anoikis. Cancer Res (2000) 60:3419–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ilantzis C, DeMarte L, Screaton RA, Stanners CP. Deregulated expression of the human tumor marker CEA and CEA family member CEACAM6 disrupts tissue architecture and blocks colonocyte differentiation. Neoplasia (2002) 4:151–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Scheffrahn I, Singer BB, Sigmundsson K, Lucka L, Obrink B. Control of density-dependent, cell state-specific signal transduction by the cell adhesion molecule CEACAM1, and its influence on cell cycle regulation. Exp Cell Res (2005) 307:427–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kirshner J, Chen CJ, Liu P, Huang J, Shively JE. CEACAM1-4S, a cell-cell adhesion molecule, mediates apoptosis and reverts mammary carcinoma cells to a normal morphogenic phenotype in a 3D culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2003) 100:521–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232711199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Muller MM, Singer BB, Klaile E, Obrink B, Lucka L. Transmembrane CEACAM1 affects integrin-dependent signaling and regulates extracellular matrix protein-specific morphology and migration of endothelial cells. Blood (2005) 105:3925–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Liu W, Wei W, Winer D, Bamberger AM, Bamberger C, Wagener C, et al. CEACAM1 impedes thyroid cancer growth but promotes invasiveness: a putative mechanism for early metastases. Oncogene (2007) 26:2747–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fournes B, Sadekova S, Turbide C, Letourneau S, Beauchemin N. The CEACAM1-l Ser503 residue is crucial for inhibition of colon cancer cell tumorigenicity. Oncogene (2001) 20:219–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kammerer R, Hahn S, Singer BB, Luo JS, von Kleist S. Biliary glycoprotein (CD66a), a cell adhesion molecule of the immunoglobulin superfamily, on human lymphocytes: structure, expression and involvement in T cell activation. Eur J Immunol (1998) 28:3664–74. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Morales VM, Christ A, Watt SM, Kim HS, Johnson KW, Utku N, et al. Regulation of human intestinal intraepithelial lymphocyte cytolytic function by biliary glycoprotein (CD66a). J Immunol (1999) 163:1363–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.163.3.1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hanenberg H, Baumann M, Quentin I, Nagel G, Grosse-Wilde H, von Kleist S, et al. Expression of the CEA gene family members NCA-50/90 and NCA-160 (CD66) in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemias (ALLs) and in cell lines of b-cell origin. Leukemia (1994) 8:2127–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Scholzel S, Zimmermann W, Schwarzkopf G, Grunert F, Rogaczewski B, Thompson J. Carcinoembryonic antigen family members CEACAM6 and CEACAM7 are differentially expressed in normal tissues and oppositely deregulated in hyperplastic colorectal polyps and early adenomas. Am J Pathol (2000) 156:595–605. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64764-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Busch C, Hanssen TA, Wagener C, O.Brink B. Down-regulation of CEACAM1 in human prostate cancer: correlation with loss of cell polarity, increased proliferation rate, and Gleason grade 3 to 4 transition. Hum Pathol (2002) 33:290–8. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.32218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Thies A, Moll I, Berger J, Wagener C, Brummer J, Schulze HJ, et al. CEACAM1 expression in cutaneous malignant melanoma predicts the development of metastatic disease. J Clin Oncol (2002) 20:2530–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ieda J, Yokoyama S, Tamura K, Takifuji K, Hotta T, Matsuda K, et al. Re-expression of CEACAM1 long cytoplasmic domain isoform is associated with invasion and migration of colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer (2011) 129:1351–61. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bonsor DA, Zhao Q, Schmidinger B, Weiss E, Wang J, Deredge D, et al. The helicobacter pylori adhesin protein HopQ exploits the dimer interface of human CEACAMs to facilitate translocation of the oncoprotein CagA. EMBO J (2018) 37(13):e98664. doi: 10.15252/embj.201798664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Moonens K, Hamway Y, Neddermann M, Reschke M, Tegtmeyer N, Kruse T, et al. Helicobacter pylori adhesin HopQ disrupts trans dimerization in human CEACAMs. EMBO J (2018) 37(13):e98665. doi: 10.15252/embj.201798665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res (2000) 28:235–42. doi: 10.2210/pdb6GBG/pdb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sehnal D, Bittrich S, Deshpande M, Svobodová R, Berka K, Bazgier Václav, et al. Mol* viewer: modern web app for 3D visualization and analysis of large biomolecular structures. Nucleic Acids Res (2021) 49(W1):W431–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hamway Y, Taxauer K, Moonens K, Neumeyer V, Fischer W, Schmitt V, et al. Cysteine residues in helicobacter pylori adhesin HopQ are required for CEACAM-HopQ interaction and subsequent CagA translocation. Microorganisms (2020) 8(4):465. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8040465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Watt SM, Teixeira AM, Zhou GQ, Doyonnas R, Zhang Y, Grunert F, et al. Homophilic adhesion of human CEACAM1 involves n-terminal domain interactions: structural analysis of the binding site. Blood (2001) 98:1469–79. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Klaile E, Vorontsova O, Sigmundsson K, Muller MM, Singer BB, Ofverstedt LG, et al. The CEACAM1 n-terminal ig domain mediates cis- and trans-binding and is essential for allosteric rearrangements of CEACAM1 microclusters. J Cell Biol (2009) 187:553–67. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zhao Q, Busch B, Jimenez-Soto LF, Ishikawa-Ankerhold H, Massberg S, Terradot L, et al. Integrin but not CEACAM receptors are dispensable for helicobacter pylori CagA translocation. PLoS Pathog (2018) 14:e1007359. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kwok T, Zabler D, Urman S, Rohde M, Hartig R, Wessler S, et al. Helicobacter exploits integrin for type IV secretion and kinase activation. Nature (2007) 449:862–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Cabodi S, del Pilar Camacho-Leal M, Di Stefano P, Defilippi P. Integrin signalling adaptors: not only figurants in the cancer story. Nat Rev Cancer (2010) 10:858–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc2967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Tegtmeyer N, Harrer A, Schmitt V, Singer BB, Backert S. Expression of CEACAM1 or CEACAM5 in AZ-521 cells restores the type IV secretion deficiency for translocation of CagA by helicobacter pylori. Cell Microbiol (2019) 21:e12965. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Mejias-Luque R, Zoller J, Anderl F, Loew-Gil E, Vieth M, Adler T, et al. Lymphotoxin beta receptor signalling executes helicobacter pylori-driven gastric inflammation in a T4SS-dependent manner. Gut (2017) 66:1369–81. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev (2004) 18:2195–224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Gilmore TD. Introduction to NF-kappaB: players, pathways, perspectives. Oncogene (2006) 25:6680–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Coope HJ, Atkinson PG, Huhse B, Belich M, Janzen J, Holman MJ, et al. CD40 regulates the processing of NF-kappaB2 p100 to p52. EMBO J (2002) 21:5375–85. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Solan NJ, Miyoshi H, Carmona EM, Bren GD, Paya CV. RelB cellular regulation and transcriptional activity are regulated by p100. J Biol Chem (2002) 277:1405–18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109619200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Derudder E, Dejardin E, Pritchard LL, Green DR, Korner M, Baud V. RelB/p50 dimers are differentially regulated by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and lymphotoxin-beta receptor activation: critical roles for p100. J Biol Chem (2003) 278:23278–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300106200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Shariq M, Kumar N, Kumari R, Kumar A, Subbarao N, Mukhopadhyay G. Biochemical analysis of CagE: A VirB4 homologue of helicobacter pylori cag-T4SS. PLoS One (2015) 10:e0142606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Maubach G, Sokolova O, Tager C, Naumann M. CEACAMs interaction with helicobacter pylori HopQ supports the type 4 secretion system-dependent activation of non-canonical NF-kappaB. Int J Med Microbiol (2020) 310:151444. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2020.151444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Harris PR, Mobley HL, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ, Smith PD. Helicobacter pylori urease is a potent stimulus of mononuclear phagocyte activation and inflammatory cytokine production. Gastroenterology (1996) 111:419–25. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Sarsfield P, Jones DB, Wotherspoon AC, Harvard T, Wright DH. A study of accessory cells in the acquired lymphoid tissue of helicobacter gastritis. J Pathol (1996) 180:18–25. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Bamford KB, Fan X, Crowe SE, Leary JF, Gourley WK, Luthra GK, et al. Lymphocytes in the human gastric mucosa during helicobacter pylori have a T helper cell 1 phenotype. Gastroenterology (1998) 114:482–92. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70531-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Wilson KT, Crabtree JE. Immunology of helicobacter pylori: insights into the failure of the immune response and perspectives on vaccine studies. Gastroenterology (2007) 133:288–308. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Behrens IK, Busch B, Ishikawa-Ankerhold H, Palamides P, Shively JE, Stanners C, et al. The HopQ-CEACAM interaction controls CagA translocation, phosphorylation, and phagocytosis of helicobacter pylori in neutrophils. mBio (2020) 11(1):e03256–19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03256-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Gur C, Maalouf N, Gerhard M, Singer BB, Emgard J, Temper V, et al. The helicobacter pylori HopQ outermembrane protein inhibits immune cell activities. Oncoimmunology (2019) 8:e1553487. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1553487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Mejias-Luque R, Gerhard M. Immune evasion strategies and persistence of helicobacter pylori. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol (2017) 400:53–71. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-50520-6_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Peek RM, Jr., Crabtree JE. Helicobacter infection and gastric neoplasia. J Pathol (2006) 208:233–48. doi: 10.1002/path.1868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Amieva M, Peek RM, Jr. Pathobiology of helicobacter pylori-induced gastric cancer. Gastroenterology (2016) 150:64–78. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Hsieh JT, Luo W, Song W, Wang Y, Kleinerman DI, Van NT, et al. Tumor suppressive role of an androgen-regulated epithelial cell adhesion molecule (C-CAM) in prostate carcinoma cell revealed by sense and antisense approaches. Cancer Res (1995) 55:190–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Kunath T, Ordonez-Garcia C, Turbide C, Beauchemin N. Inhibition of colonic tumor cell growth by biliary glycoprotein. Oncogene (1995) 11:2375–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Beauchemin N, Kunath T, Robitaille J, Chow B, Turbide C, Daniels E, et al. Association of biliary glycoprotein with protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in malignant colon epithelial cells. Oncogene (1997) 14:783–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Luo W, Wood CG, Earley K, Hung MC, Lin SH. Suppression of tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells by an epithelial cell adhesion molecule (C-CAM1): the adhesion and growth suppression are mediated by different domains. Oncogene (1997) 14:1697–704. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Huber M, Izzi L, Grondin P, Houde C, Kunath T, Veillette A, et al. The carboxyl-terminal region of biliary glycoprotein controls its tyrosine phosphorylation and association with protein-tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem (1999) 274:335–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Muller MM, Klaile E, Vorontsova O, Singer BB, Obrink B. Homophilic adhesion and CEACAM1-s regulate dimerization of CEACAM1-l and recruitment of SHP-2 and c-src. J Cell Biol (2009) 187:569–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Hynes RO. Integrins: a family of cell surface receptors. Cell (1987) 48:549–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90233-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell (2002) 110:673–87. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Wessler S, Backert S. A novel basolateral type IV secretion model for the CagA oncoprotein of helicobacter pylori. Microb Cell (2017) 5:60–2. doi: 10.15698/mic2018.01.611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Hollandsworth HM, Schmitt V, Amirfakhri S, Filemoni F, Schmidt A, Landstrom M, et al. Fluorophore-conjugated helicobacter pylori recombinant membrane protein (HopQ) labels primary colon cancer and metastases in orthotopic mouse models by binding CEA-related cell adhesion molecules. Transl Oncol (2020) 13:100857. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]