Abstract

The immune system plays critical roles in both autoimmunity and cancer, diseases at opposite ends of the immune spectrum. Autoimmunity arises from loss of T cell tolerance against self, while in cancer, poor immunity against transformed self fails to control tumor growth. Blockade of pathways that preserve self-tolerance is being leveraged to unleash immunity against many tumors; however, widespread success is hindered by the autoimmune-like toxicities that arise in treated patients. Knowledge gained from the treatment of autoimmunity can be leveraged to treat these toxicities in patients. Further, the understanding of how T cell dysfunction arises in cancer can be leveraged to induce a similar state in autoreactive T cells. Here, we review what is known about the T cell response in autoimmunity and cancer and highlight ways in which we can learn from the nexus of these two diseases to improve the application, efficacy, and management of immunotherapies.

Introduction

The immune system plays a key role in the pathogenesis and progression of both autoimmunity and cancer, diseases that lie at opposite ends of the immune spectrum. While autoimmunity ensues from the loss of self-tolerance and subsequent immune responses directed against normal tissues, cancer ensues from the failure to break self-tolerance and poor immune responses directed against cells that have undergone malignant transformation. At the center of both of these diseases are T cells, where in autoimmunity their aberrant activation drives autoimmune tissue damage and in cancer their suppressed responses fail to control tumor growth. Accordingly, T cells are the primary targets of therapeutic strategies to either dampen (autoimmunity) or elicit (cancer) immunity in these diseases. Although B cells also have an important role in both autoimmunity and cancer, this review will focus on the T cell response in these diseases.

Although at opposite ends of the immune spectrum, autoimmunity and cancer are linked. The role of immune checkpoint receptors in self-tolerance was discovered and first studied in autoimmunity, but now the blockade of immune checkpoint receptors (Immune checkpoint blockade; ICB) has been harnessed to invigorate the immune response against cancer, achieving unprecedented results in multiple tumor indications. However, ICB can lead to immune-related adverse events (irAEs) in a significant portion of patients through mechanisms of tolerance disruption that closely resemble those observed during autoimmunity. In cancer, immune checkpoint receptors are highly expressed on T cells and contribute to the development of T cell dysfunction, a dampened T cell state that arises in the face of chronic antigen stimulation. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underpinning the acquisition of dysfunctional phenotype in tumor-specific T cells can inform strategies to induce such a state in auto-reactive T cells and thereby limit their ability to drive autoimmune pathology. Here, we will review the main features of the T cell response in autoimmunity and cancer and propose ways by which we can learn from the nexus of these fields to improve the application, efficacy, and management of immunotherapies.

Disruption of T cell tolerance in autoimmunity and cancer

Because of their ability to drive tissue pathology, T cell specificity and activation is controlled by mechanisms of central and peripheral tolerance. Central tolerance occurs during T cell development in the thymus, where T cells whose T cell receptors (TCRs) bind self-Major Histocompatibility Complexes (MHC) too strongly undergo apoptosis. This process is instrumental in eliminating potentially auto-reactive T cell clones. However, the efficiency of central tolerance is estimated to be only 60-70% (1, 2). Indeed, the frequency of some self-reactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (against antigens such as keratin and pre-proinsulin) has been estimated to be in the same range (between 1:104 and 1:106) observed for T cells recognizing viral epitopes (3). The presence of such potentially auto-reactive T cells necessitates the existence of mechanisms of peripheral tolerance, such as, active suppression, anergy, and ignorance, meant to control these self-reactive “escapees”.

A key mechanism of peripheral tolerance is active suppression of self-reactive T cells by CD4+ regulatory T (Treg) cells that are marked by expression of the master transcription factor FOXP3. Treg cells harbor a TCR repertoire skewed toward self-antigen recognition (4), which, to a certain extent, overlaps with the repertoire of auto-reactive conventional CD4+ T cells (5). Treg cells actively suppress autoimmune responses in the periphery as demonstrated by the fatal multiorgan pathology unleashed by the germline or transient deletion of FOXP3+ Treg cells in mice (6, 7), and the development of IPEX (immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked) syndrome in humans harboring mutations in the FOXP3 gene (8). Notably, defective Treg cells have been described in several autoimmune diseases (9–11). Conversely, Treg predominate in cancer where they present a major barrier to the generation of proficient anti-tumor immunity by suppressing effector CD8+ T cell responses and promoting the development of CD8+ T cell dysfunction (discussed further below) (12, 13).

Similar to Treg cells, several studies have demonstrated the existence of a subpopulation of CD8+ T cells that have regulatory features (CD8reg) and are able to suppress autoreactive CD4+ T cells in several autoimmunity models (14–16) and anti-tumor CD8+ effector T cells in cancer (17, 18). Interestingly, CD8reg do not express Foxp3 but share with Treg cells the expression of Helios, which is indispensable for the suppressive activity of both CD4+ Treg and CD8reg (16). Another notable feature of CD8reg is that they have been shown in multiple models of autoimmune disease to be restricted by non-classical MHC (Qa-1 in mouse; Hl_A-E in human) (19–25). However, a study examining the antigen-specificity of CD8+ T cells in human multiple sclerosis (MS) and in a murine model of central nervous system (CNS) autoimmunity found that clonally expanded CD8reg recognize peptides derived from non-myelin antigens presented on classical MHC-I molecules (26). Further research is needed to define the contribution of classically versus non-classically MHC-restricted CD8reg in autoimmunity. Whether the CD8reg present in tumors are restricted by classical or non-classical MHC, as well as their antigen specificity, has not been investigated.

Another mechanism of peripheral tolerance is the requirement for secondary signals in the form of co-stimulation. To elicit a proficient effector response, T cells must encounter their cognate antigen in an inflammatory context in which antigen-presenting cells (APCs) are stimulated to provide a second positive signal via co-stimulatory molecules (e.g. CD80, CD86) that bind to co-stimulatory receptors (e.g.CD28) on T cells. The concomitant activation of the TCR and CD28 leads to an intracellular cascade culminating in the activation of several transcription factors including nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), FOS/JUN dimers (AP-1) and the NF-κB complex (27, 28). These factors cooperatively drive T cell expansion and initiate effector differentiation. T cells that encounter their antigen in the absence of co-stimulation become anergic; a hyporesponsive cell state marked by poor activation of the AP-1 pathway (29, 30), early arrest in the G1 to S cell cycle phase (31), and inability to exert effector functions (pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and cytolytic activity). In the context of suboptimal AP-1 activation, NFAT binds the DNA in a monomeric form and drives the expression of a gene program that shares features with T cell dysfunction (32–34), a T cell state that arises in the face of chronic antigen triggering and is characterized by dampened effector functions and high expression of immune checkpoint receptors (35–38). Interestingly, as dysfunction-associated regulatory regions in CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are enriched for NFAT binding motifs (34), and dysfunction-associated features are established early during tumor progression in tumor-specific CD8+ T cells (39), it is conceivable that a fraction of CD8+ TILs persist in an anergic rather than dysfunctional state. In regards to autoimmunity, Treg cells have been shown to actively keep the auto-reactive T cells present in healthy individuals in an anergic state (40).

Another mechanism of peripheral tolerance is clonal ignorance whereby self-reactive T cells are maintained in a naïve or hyporesponsive state either because the self-antigen is expressed in “immune privileged” anatomical sites that are not accessible to the immune system (e.g. eye, brain, testes) or because the antigen is expressed at low levels and/or is recognized by low affinity TCRs. T cell ignorance has been exploited in the context of T cell-based immunotherapies for cancer as neoplastic cells can aberrantly express antigens that are normally confined to immune privileged organs or that are expressed only during embryonic development. Immune responses against such antigens can be elicited through vaccination strategies. Alternatively, T cells that recognize such antigens can be expanded ex vivo prior to adoptive transfer in cancer patients (41, 42). A notable example of such an antigen is the cancer testis antigen NY-ESO-1, which is expressed by several tumors and has been exploited therapeutically (43). While all of these mechanisms of tolerance are in place to ensure specific and timely activation of T cells, failure or overactivity of any of these tolerance mechanisms can result in autoimmune pathology or hyporesponsiveness against nascent tumors, respectively (latter reviewed in (38)).

Impact of MHC on T cell responses in autoimmunity and cancer

Antigens are presented to T cells via either MHC-I or MHC-II molecules. MHC-I molecules are expressed by all nucleated cells and present intracellular antigens of 8 to 10 amino acids, while MHC-II molecules are expressed by professional APCs, such as dendritic cells, B cells, and macrophages, that present extracellular antigens of 13-25 amino acids. Accordingly, T cell responses are modulated by the strength and affinity of TCR-peptide MHC interactions. Thus, genetic variance in MHC genes (also known as human leukocyte antigens; HLA) within the human population can modify the quantity and quality of such interactions, thereby resulting in diversified T cell responses. Indeed, MHC genes are highly polymorphic within the human population (44), especially in the peptide-binding regions, thus generating peptide-MHC binding biases across individuals, which have been linked to differential susceptibility to autoimmunity, infection, and cancer (45–47).

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in several autoimmune diseases, such as MS, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Type 1 diabetes (T1D), and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), showed that MHC-II alleles are strongly associated with risk (48, 49). The strong association with MHC-II alleles is in line with the critical role played by effector CD4+ T cell responses in propagating and maintaining autoimmunity. In cancer, genetic associations between MHC and non-MHC genes involved in immune processes have been found for cancers associated with infections (e.g. cervical cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, head and neck cancer), hematologic cancers (50–52), and other solid tumors (53–55). In contrast to autoimmunity, risk loci appear to be equally spread amongst MCH-I and MHC-II alleles, suggesting equal roles for CD8+ T cytotoxic and CD4+ T helper processes, although more studies will be required to address this (50). Despite this, basic and translational cancer research has focused predominantly on the role of MHC-I-restricted CD8+ T cell responses. As discussed, a major barrier toward eliciting proficient anti-tumor responses against neoplastic cells is the inability of T cells to overcome the hurdles presented by self-tolerance. In this regard, epidemiological as well as preclinical studies provide evidence for MHC-II restricted responses to elicit strong and long-lasting responses against self (56–62), suggesting that leveraging CD4+ T cell responses in cancer may be essential for the development of long-lasting anti-tumor responses. Indeed, a recent study evaluating immune responses after immunotherapy, correlated the presence of a CD4+ T cell subset in animal models and in the blood of melanoma ICB-responder patients with significantly longer protection against tumor outgrowth (63). CD4+ T cells can: (i) provide help to CD8+ T cells through both licensing of DCs for CD8+ T cell priming and secretion of cytokines (64, 65), (ii) exert cytotoxicity toward cancer cells (66), and (iii) promote tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS), which have been positively associated with ICB responses (67, 68). Thus, future immunotherapies tailored to unleash anti-tumor CD4+ T cell responses may be instrumental for achieving long-lasting anti-tumor immunity (69–71).

Regulation of T cell responses by immune checkpoint receptors

Control of effector T cell differentiation is achieved by the progressive expression of checkpoint receptors, also referred to as co-inhibitory receptors (72), during T cell activation. Immune checkpoints were first discovered and studied in the context of autoimmunity. Loss of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) in mice was shown to lead to lethal lymphoproliferative autoimmunity in early-life (73, 74). The importance of CTLA-4 for controlling effector T cell responses was confirmed in humans where germline heterozygous CTLA-4 mutations were associated with grave immune pathology caused by dysregulation of Treg cells and hyperactivation of effector T cells (75). Although CTLA-4 expression progressively increases in conventional T cells upon activation (76), it is important to note that the highest levels of CTLA-4 are found in Treg and its conditional deletion in this subset phenocopies the autoimmune phenotype displayed by Treg deficiency (77). Another immune checkpoint increased during T cell activation is programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), whose germline deletion can lead to autoimmunity in susceptible genetic backgrounds (78). Notably, CTLA-4 and PD-1 differ in that PD-1 blockade was shown to reverse the maintenance of antigen-specific T cell tolerance toward pancreatic islets, while CTLA-4 blockade could hinder the establishment but not reverse the maintenance of tolerance, in a preclinical model of diabetes (78, 79). In humans, the key role of PD-1 in regulating immunity has been recently supported by a case report of a child with inherited PD-1 deficiency exhibiting impaired immunity against TB followed by fatal pulmonary autoimmunity (80). Altogether, the CTLA-4 and PD-1 axes exemplify the role of immune checkpoints in controlling auto-aggressive T cell responses at different stages.

Continued and repeated T cell stimulation leads to the expression of a second wave of immune checkpoint expression. To date, the receptors that are being heavily studied in both the autoimmunity and cancer contexts are T cell immunoglobulin-3 (TIM-3), lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3), and T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT), whose expression patterns and pleiotropic functions have been reviewed elsewhere (72, 81). These receptors are of great interest as they are expressed later in the trajectory of T cell differentiation, and thus their antagonism in cancer or agonism in autoimmunity may result in a lower probability of therapy-related adverse events. In particular, high expression of these receptors is characteristic of dysfunctional CD8+ T cells that exhibit reduced self-renewal capacity and dampened effector functions (pro-inflammatory cytokine production, proliferation, cytotoxic capacity) (35). Dysfunction represents an important peripheral tolerance mechanism as it curbs effector T cell responses and thus, the development of immune-driven pathology in settings of antigen persistence, such as in chronic viral infection or cancer. In cancer, dysfunction is considered an obstacle to effective anti-tumor immunity. Accordingly, ICB therapies were developed with the goal of interfering with dysfunctional phenotype. While undesirable in cancer, the engagement of dysfunction in the context of autoimmunity could be beneficial. Evidence from animal models shows that immune checkpoints are lowly expressed on self-reactive CD4+ T cells and that presence of a transcriptional signature of CD8+ T cell dysfunction is associated with better prognosis in various autoimmune diseases (72, 82). In humans, defects in immune checkpoints have also been noted in patients with autoimmunity. For example, the immune checkpoint TIM-3 has been found to be defective in both expression and function in patients with MS (83, 84). Further, in both MS and RA, positive response to therapy has been associated with restoration of TIM-3 expression (83, 85). These observations underscore that increased understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying dysfunction are required to tailor disease-specific therapeutic interventions for both cancer and autoimmunity.

In addition to effector T cells, immune checkpoint receptors are also expressed on Treg cells and, thus, their phenotype can be altered by ICB. Although there are still uncertainties as to the role of these receptors in Treg, some studies suggest that ICB may backfire by augmenting Treg suppressive capacity and proliferation. For example, rapid cancer progression after anti-PD1 was observed in a subset of gastric cancer patients and was associated with the expansion of intra-tumoral Treg cells (86). In line with this, PD-1-deficient Treg cells have been shown to have heightened suppressive function and be protective in models of autoimmunity (87). Similarly, LAG-3 was shown to restrain Treg proliferation and suppressive activity in autoimmune diabetes (88). Lastly, the efficacy of anti-CTLA-4 in treating cancer has been ascribed by different investigations to the depletion of intra-tumoral Treg (89–91), leading to the manufacturing and investigation of a new generation of anti-CTLA-4 antibodies that deplete Treg cells via antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) (92).

Interestingly, suppressive features, akin to those of CD4+ Treg and CD8reg, have been ascribed to late dysfunctional CD8+ TIL. In this regard, their suppressive activity has been shown to be dependent on the expression of the checkpoint receptor CD39 (18, 93). Whether these cells are a distinct subset or are dysfunctional cells that have adopted heightened expression of a suppressive gene program remains to be determined. As these cells also express other checkpoint receptors, including CTLA-4, LAG-3, TIM-3, and TIGIT, it will be important to determine whether their suppressive properties are affected by ICB.

Overall, in autoimmunity and cancer, the expression and function of immune checkpoint receptors varies on T cells. It is also conceivable, that the expression and function of distinct checkpoint receptors may predominate in different organs and tissues. In this regard, we are just beginning to decipher the regulation of immune checkpoint receptor and ligand expression in different tissues, which may inform how specific organs may either benefit or be at risk of adverse events from immune checkpoint targeting (81).

Steroid hormone regulation of T cell responses

Steroid hormones, which comprise corticosteroids (glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids) and sex steroids (androgens, estrogens, and progestogens) are known to have important roles in regulating the immune response in autoimmunity and cancer. Recent data shed light on the molecular mechanisms used by steroid hormones to achieve their effects on immune cells and how this information can be leveraged for improving therapy for these diseases.

Glucocorticoids bind to the glucocorticoid receptor (GR, encoded by Nr3c1), a ligand-activated transcription factor. The GR can suppress T cell responses by binding to and interfering with the activity of NF-kB (94, 95) and AP-1 (96) in inducing pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFNγ, TNFα) or by inducing the expression of IL-10, checkpoint receptors, and the expression of genes associated with T cell dysfunction (97). The GR can also induce the glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ, encoded by Tsc22d3), which promotes induced Treg (iTreg) cells (98–102). Because of its potent immune suppressive properties, administration of exogenous glucocorticoid has been the gold standard therapy for autoimmune disease exacerbations for decades and has been leveraged in recent years to treat irAEs that develop in cancer patients treated with ICB (discussed further below).

Glucocorticoids are mainly produced in the adrenal gland under the control of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. However, extra-adrenal production of GCs has been reported in multiple types of immune cells including monocyte-macrophages (97), CD4+ T cells (103, 104), CD8+ T cells (105), and DCs (106). We have previously shown that tumor associated monocyte-macrophage lineage cells can produce glucocorticoids locally to enhance checkpoint receptor expression and promote acquisition of gene programs associated with T cell dysfunction in the tumor microenvironment (TME) (97). Others have shown that CD4-derived glucocorticoid can also suppress anti-tumor immunity (103). The endogenous production of glucocorticoids in tumor tissue together with the role of glucocorticoids in promoting checkpoint receptor expression and T cell dysfunction raise important considerations for the use of glucocorticoids in cancer patients, particularly those treated with ICB (discussed below).

Although, a role for extra-adrenal production of glucocorticoids has not been investigated in autoimmunity, the putative locus control region of Cyp11a1, the rate-limiting enzyme catalyzing the production of the steroid precursor pregnenolone, has been reported to be open in CD4+ IL-17-producing (Th17) cells that are main mediators of autoimmune tissue inflammation (103). Further, Th17 cells have been described to be steroid resistant (107, 108). Thus, uncovering means to harness steroid production in Th17 cells and improve their glucocorticoid responsiveness may be therapeutically beneficial for treating autoimmunity and ICB-induced irAEs.

Sex steroids are primarily synthesized in the gonads and are regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. As all steroid hormones are derived from the same steroid precursor (pregnenolone), it is possible that the same immune cells described to produce glucocorticoids also produce sex hormones. Similar to glucocorticoids, sex hormones bind to ligand-activated transcription factors and the male sex steroid, androgen, has been described to be immune suppressive (109). This property of androgen may underlie why most autoimmune diseases are more prevalent in females compared to males, who have higher circulating androgen levels. Moreover, it is reported that the thymic autoimmune regulator (Aire), which prevents autoimmunity by promoting self-tolerance during T cell development, is higher in males compared females. In this regard, ligand-bound androgen receptor (AR) has been shown to enhance Aire transcription while ligand-bound ER (estrogen receptor) downregulates Aire (110, 111). In contrast to autoimmunity, males have higher incidence and mortality of many human cancers compared to females, and recent studies suggest that androgen may contribute to this sex bias (112, 113). These studies reported that ablation of the AR enhanced effector T cell differentiation and function and, thereby, improved responses to T cell-directed cancer immunotherapy in pre-clinical cancer models. Notably, one study showed that the AR mediated these effects via promotion of stem-like CD8+ T cells that give rise to effectors that eventually become dysfunctional (112). Stem-like CD8+ T cells rely on the transcription factor TCF-1 for their maintenance (114, 115). In this regard, the AR was shown to bind to the Tcf7 locus and directly transactivate transcription of TCF-1 (112). Importantly, the advantage of combining anti-androgen therapy with ICB has been demonstrated in clinical trials in prostate cancer and bladder cancer (116, 117). Future studies should investigate whether AR-driven effects on TCF1 and T cell differentiation also underlie sex bias in autoimmunity.

Disease cycles in autoimmunity and cancer

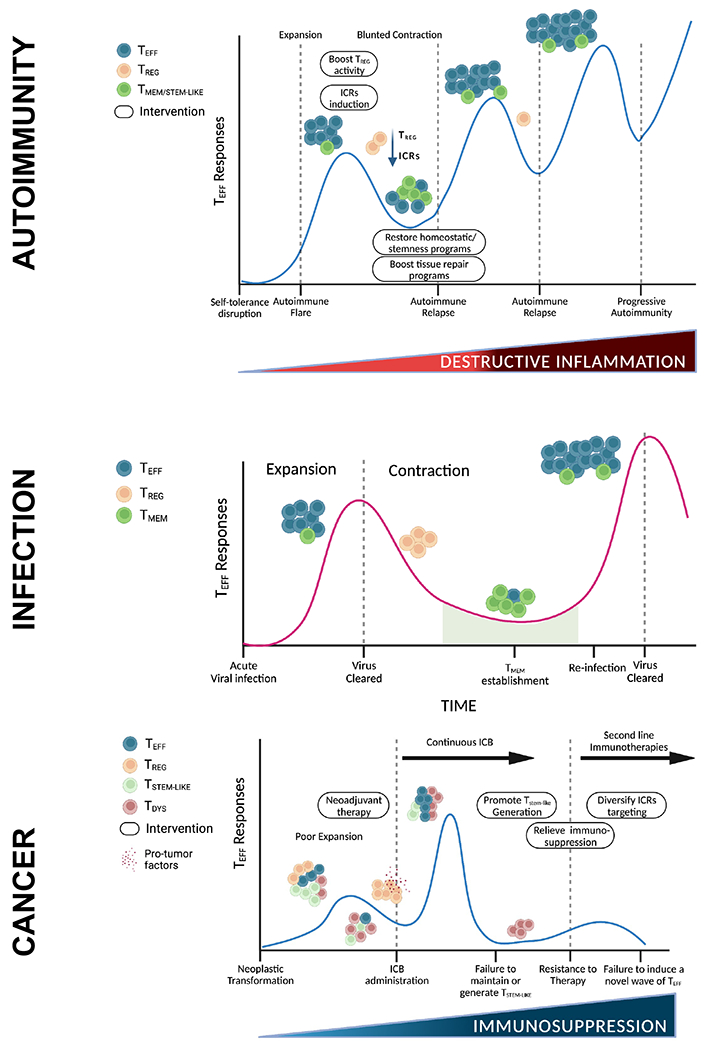

The clinical course of most autoimmune diseases is characterized by an initial disease flare followed by cycles of remission and relapse (Figure 1). With each disease cycle, the autoimmune response often grows stronger, ultimately transitioning to a chronic progressive response that is highly resistant to therapeutic interventions. Similarly, in acute viral infections, antigen re-encounter unleashes a faster and stronger immune response by T memory cells (Tmem) leading to prompt pathogen clearance. In contrast, immune responses against tumors have been proposed to more closely resemble those observed in the context of chronic viral infections where the initial effort of the immune system to clear the transformed cells (or infectious pathogens) is unsuccessful, thereby leading to a prolonged immune response of lesser magnitude in which T cells become progressively dysfunctional (38, 118). However, a cyclic disease course can be triggered in the cancer context either by surgical removal of the tumor or by therapy (ICB, chemotherapy, radiotherapy)-induced tumor regression. Unfortunately, the majority of cancer patients eventually relapse, which marks the beginning of a new disease cycle. Thus, any therapeutic strategy aimed at modulating immune responses in the context of autoimmunity or cancer, should take into account that immune responses are cyclic and different phases of the disease course need to be approached differently (Figure 1).

Figure 1. T cell response cycles in autoimmunity, infection, and cancer.

Upper panel, autoimmunity: Disruption of self-tolerance initiates the expansion of self-reactive effector T cells that comprise the first autoimmune flare. The inflammatory state is further accentuated by reduced regulatory T cell suppressive capacity and low immune checkpoint expression by self-reactive effector T cells. At the peak of the flare, therapeutic strategies should be aimed at boosting Treg activity and immune checkpoint expression in self-reactive T cells. Eventually, the effector T cell response undergoes contraction; however, this is blunted compared to acute infection because of the continued presence of the triggering antigen and/or persistence of tissue inflammation. In this phase, restoration of T cell homeostasis programs and tissue repair programs may provide a viable strategy to tone down overall inflammation. Even though current therapeutic strategies are able to keep autoimmune responses at bay for extended periods of time, eventually autoimmune TMEM/STEM-LIKE cells from the periphery expand again, leading to autoimmune relapses and development of progressive autoimmunity. Middle panel, infection: Acute viral infections trigger a swift effector T cell expansion. Upon virus clearance, the effector T cell pool contracts because of the reduced presence of viral antigens and the activity of Tregs, leading to re-establishment of homeostasis. A small population of T memory (TMEM) cells is established and persists long term. Additional encounters with the same pathogen trigger a response that is faster and of a higher magnitude, leading to prompt viral clearance. Lower panel, cancer: Upon neoplastic transformation, tumor antigens are presented within a poorly inflamed environment, leading to poor expansion of tumor-reactive effector T cells. Tregs further dampen effector T cell responses and secrete pro-tumor factors (e.g. TGFβ, IL-10, IL-35, amphiregulin), promoting tumor outgrowth. Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) re-invigorates anti-tumor responses by eliciting a wave of T effector cells, which is sustained by a small pool of stem-like precursor cells. Neoadjuvant therapies elicit such immune responses prior to surgical resection of the primary tumor. However, continuous ICB post-surgery may hinder the establishment of long-term memory and lead to the reduction of the stem-like pool, which in turn may result in a sharp decline in the effector T cell population and hinder the generation of novel waves of effector T cells upon second-line immunotherapies, such as therapies targeting different immune checkpoint receptors (ICRs). The remaining T cells are in a terminal dysfunctional state, unable to control tumor growth. Therapeutic interventions should aim at the re-establishment of a cyclic T cell response by promoting the maintenance and generation of the T stem-like pool (e.g. implement a period of time in which patients are off ICB treatment). Also, dysfunction is induced by chronic antigen stimulation within the immunosuppressive TME. Thus, concomitant strategies to relieve local immunosuppression (e.g. co-stimulatory agonists, TGFβ pathway blockade, steroid blockade, reduced hypoxia) should be leveraged to promote anti-tumor immunity.

Abbreviations: TMEM-STEM-LIKE, T memory/stem-like; TREG, T regulatory cells; TEFF, T effector cells; TDYS, T dysfunctional cells; ICRs, immune checkpoint receptors.

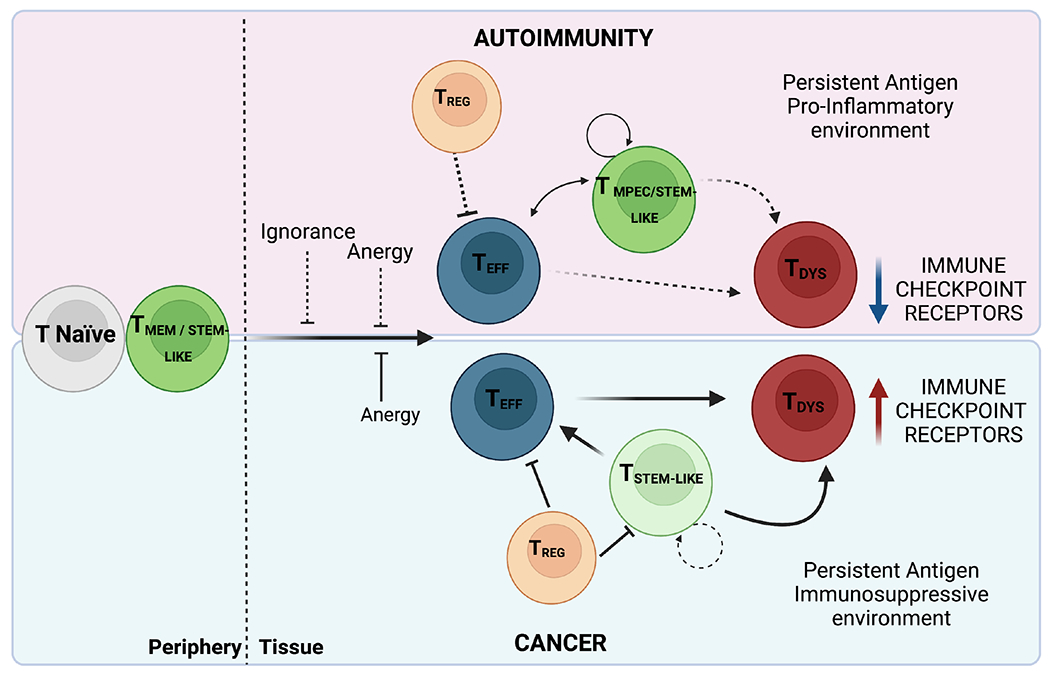

Differences in the T cell activation trajectory underlie the observed disease cycles in autoimmunity and cancer (Figure 2). In autoimmunity, self-tolerance is broken, resulting in the activation of auto-reactive naïve T or memory T cells. Their low expression and/or defective function of immune checkpoints prevents their development of dysfunctional phenotype. Defective Treg suppression further prevents their control. In cancer, differentiation of naïve T or stem-like T cells into effector T cells is dampened by the poor co-stimulatory environment, which early on may promote T cell anergy. T cells that successfully undergo effector differentiation are exposed to chronic antigen stimulation and progressively become dysfunctional. In contrast to the autoimmune context, Treg cells retain their suppressive capacity and hinder anti-tumor immunity. Notably, despite being perpetually exposed to self-antigens, auto-reactive T cells do not develop the dysfunctional phenotype displayed by chronically activated T cells in the cancer context. This is likely due to the different environmental conditions present in the highly immune-suppressive TME compared to the pro-inflammatory tissue environment in autoimmunity.

Figure 2. T cell trajectory in autoimmunity and cancer.

Upper panel, autoimmunity: Self-reactive naïve T or memory T cells overcome the barrier posed by ignorance and anergy (dashed lines) and differentiate into pro-inflammatory effector T cells. These effector T cells are efficiently maintained and replaced at each disease flare by a pool of T memory precursor/stem-like cells that can self-renew. Persistent self-antigen within a highly pro-inflammatory tissue environment reduces Treg capacity (dashed lines) to contain effector T cell responses. Low expression or defective function of immune checkpoint receptors on effector T cells prevents their acquisition of dysfunctional T cell phenotype (dashed lines). Lower panel, cancer: Differentiation of naïve T or stem-like T cells into effector T cells is dampened by the poor co-stimulatory environment in which antigens are presented early on during tumorigenesis, promoting T cell anergy. Stem-like T cells that have limited self-renewal potential compared to long-lived memory cells can differentiate into effector T cells but chronic antigen stimulation in the context of a highly immunosuppressive environment will push the differentiation trajectory toward dysfunction, resulting in failure to control tumor growth. The immunosuppressive environment is further heightened by the activity of Treg, which inhibit tumor-specific CD8+ effector T cells and stem-like T cells.

Abbreviations: TMPEC: T memory precursors; TREG: T regulatory cells; TEFF: T effector cells; TDYS: T dysfunctional cells

Such environmental differences further affect the generation of T cells endowed with memory/stem-like features. In cancer, stem-like precursors or T precursor exhausted (Tpex) that are marked by the expression of the transcription factor TCF1 and, thus, retain some self-renewal capacity have been identified as the T cell subset responsible for the proliferative burst upon ICB (119, 120). Importantly, their presence has been associated in several studies with response and progression free survival (PFS) upon ICB in patients (115, 121, 122). However, whether prolonged administration of ICB may deplete this pool, ultimately compromising anti-tumor immunity, is not known (118). Prolonged ICB may further interfere with long-term memory formation. Indeed, the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, a major target of current immunotherapies, has been shown to have a crucial role in promoting T cell memory (123). In the context of viral infections, absence or blockade of PD-1 leads to a re-invigoration of CD8+ T cytotoxic responses but failure to generate productive memory (124, 125). Further, the timing of the anti-PD-1 treatment seems to play an important role as early blockade was shown to have less impact on memory formation (123). Finally, tracking of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells in patients with refractory tumors revealed that PD-1-deficient cells persisted less than their PD-1-proficient counterpart (126). Thus, the continuous administration of ICB disrupts the natural cycle of T cell responses, ultimately resulting in loss of therapeutic efficacy. Accordingly, therapeutic regimens should take into consideration the totality of the T cell response and not simply target only one part of it. In autoimmunity, the observed remission-relapse pattern suggests the presence of periodic cycling of Tmem- or stem-like T cell-driven inflammatory responses, followed by reactivation of Treg-mediated suppressive activity (Figure 1). Thus, a better understanding of the timing, re-activation triggers, and anatomic location of self-reactive Tmem- or stem-like cells may be extremely helpful in guiding immunotherapy regimens. At present, surprisingly little is known about stem-like T cell subsets in autoimmunity, except for a gut reservoir of stem-like myelin-reactive CD4+ T cells that has been identified in mice (127). More studies are urgently needed to deepen our understanding of the molecular and functional features of CD4+ stem-like T cells in autoimmunity, as they could shed light on specific gene programs that can be exploited in anti-tumor CD4+ T cells to promote persistent anti-tumor CD8+ T cell responses.

Therapeutic strategies for autoimmunity and cancer

One of the major questions in the field of tolerance and autoimmunity is why mechanisms of central tolerance allow for the escape of potentially self-reactive T cell clones. In recent years it has become increasingly appreciated that self-reactive T cells are not to be viewed as circulating “ticking bombs” ready to trigger autoimmunity, but rather as cells that perform important homeostatic functions within tissues (128). For example, T cells have been linked with the acquisition of cognitive function, as mice lacking T cells display impaired learning as well as spatial and social skills (129–131). These effects may be antigen-dependent as transgenic mice bearing a myelin-specific TCR exhibit heightened adult neurogenesis compared to wild type mice and transgenic mice bearing an ovalbumin-specific TCR, which showed impaired neurogenesis (130). Antigen specificity appears to be key also in murine models of CNS injury where T cells specific for CNS antigens, but not for unrelated antigens, have been shown to improve axonal repair and neuronal survival (132, 133). These data support a model whereby self-antigen-specific T cells are retained to exert physiological functions needed to maintain and/or re-establish homeostasis within tissues (134). However, auto-reactive effector T cells have the intrinsic danger of going awry and driving autoimmune manifestations. As previously highlighted, Treg cells are a major barrier against autoimmunity. They may also play a key role in helping to restore and/or sustain the homeostatic functions of self-reactive T cells (Figure 1). At the other end of the spectrum, Treg cells have been shown to strongly hinder anti-tumor responses and even activate tissue repair mechanisms that supply tumor cells with pro-survival growth factors (135–137). Therefore, it is desirable to elicit a strong Treg-mediated immune suppression in the case of autoimmunity to restore homeostatic functions and, conversely, to dampen Treg-mediated suppression to enable “beneficial autoimmunity” to eradicate tumor cells. Beneficial autoimmunity against cancer is supported by a recent report demonstrating that patients responding to ICB had expansion in the peripheral blood of a CD8+ T population reactive against normal melanocyte antigens compared to non-responders (138).

Currently, patients with autoimmunity are continuously treated during disease remission in an attempt to prevent relapses, while during relapses patients are treated with glucocorticoids. For example, patients with MS are commonly treated with Ocrelizumab (anti-CD20) during remission and with methylprednisolone (glucocorticoid) during relapses. Despite treatment, relapses will become more frequent, of higher magnitude, and refractory to glucocorticoid administration over time. It has been proposed that relapses are driven by the periodic re-activation of a peripheral pool of memory or stem-like auto-reactive T cells (139). Myelin-reactive CD4+ T cells that display T memory features have been shown to be present in the blood of healthy individuals (140). Characterization of these myelin-reactive CD4+ T cells revealed that while those isolated from healthy individuals readily produced the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 upon re-activation, those derived from patients with MS were poised to produce the highly pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-17A and GM-CSF. The IL-10-producing myelin-reactive CD4+ T cells in normal healthy individuals likely serve important homeostatic functions that could benefit patients with MS if they could be restored. Thus, while current therapeutic strategies in autoimmunity aim at preventing further attacks, novel strategies should consider re-establishment of homeostasis as a goal by: (i) inducing a quiescence program in auto-reactive T cells, (ii) enhancing Treg function to suppress inflammation, or (iii) boosting innate and stromal programs to repair tissue damage (Figure 1). However, it can also be argued that elimination of self-reactive cells with homeostatic/stem-like properties may represent the better approach as they are an important source of destructive effector T cells. As an example, in diabetes preclinical models it has been identified an auto-reactive CD8+ stem-like population that resides in the pancreatic draining lymph nodes and sustains a continuous output of CD8+ effector mediators that actively destroy pancreatic β-cells (141). Future studies are required to identify whether such CD8+ stem-like population exists in humans and whether its targeting may be beneficial. Considering that homeostatic functions have been primarily ascribed to CD4+ T cell populations, therapeutic strategies aimed at either re-establish homeostatic properties or deplete the stem-like pool may depend on the type of T cell lineage.

Another therapeutic option is represented by neoadjuvant therapies, which refer to strategies aimed at boosting immune responses against tumors, and potentially micrometastases, prior to surgical resection of the primary tumor. Framed within the cyclic nature of immune responses, neoadjuvant therapies aim to boost effector T cell responses while the ensuing tumor resection reduces the tumor antigenic burden, thereby promoting establishment of T memory precursors that can sustain long-term immunity (Figure 1). An initial study of neoadjuvant anti-PD1 (Nivolumab) blockade in resectable non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) showed few side-effects and induced a major pathologic response in 9 out of 20 treated patients (142). Therapeutic response was correlated with tumor mutation burden and the expansion of neoantigen-reactive T cell clones in the peripheral blood. A similar study in stage III/IV melanomas showed a detectable immune response to neoadjuvant anti-PD1 in 8 out of 27 patients, which remained disease-free throughout a 25-month follow-up period (143). Higher response rates were found when combining anti-PD1 with anti-CTLA-4, but at the cost of severe irAEs (144, 145).

A possible mechanism by which neoadjuvant strategies enhance anti-tumor responses is by promoting the priming of tumor-antigen specific stem-like CD8+ T cells in the tumor-draining lymph nodes (tdLNs), which are often removed during surgical resection of the primary tumor. Indeed, it has been shown that tdLNs contain a reservoir of stable tumor antigen-specific CD8+ stem-like population that sustains the output of anti-tumor effector CD8+ T cells in preclinical models (146). This CD8+ stem-like population was not found at appreciable levels in other secondary lymphoid organs. Thus, the efficacy of neoadjuvant therapies may improve if the tdLNs are preserved. In this regard, it is important to note a recent study showing that lymph node colonization by tumor cells favors distal metastatic seeding through the promotion of suppressive, tumor-specific Treg cells (147). Although these observations advocate for a prompt removal of tdLNs, the metastatic potential in this context appeared to be mainly driven by PD-L1 expression in the tumor cells. Thus, neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade may still bear more benefits than risks by eliciting the differentiation of CD8+ stem-like T cells, lowering the activation threshold needed to expand sub-optimally activated neoantigen-specific T cell clones, and reducing the metastatic potential of tumor cells present in the tdLNs. Considering the cyclic nature of immune responses, the timing of neoadjuvant therapy may be a critical determinant of therapeutic outcome. Indeed, the time interval between neoadjuvant treatment and surgery has been shown to be critical for therapeutic success (148). The timing of neoadjuvant therapy and duration before surgery will need to be carefully tested in human clinical trials to identify the type of regimen needed to achieve the best therapeutic success, while reducing the possibility of irAEs.

Leveraging biomarkers, pharmacogenomics, and GWAS to predict therapy response and irAEs

Leveraging the data accumulated in the autoimmunity field, ICB has come to the forefront of cancer treatment, achieving unprecedented responses in several cancer indications (149). Unfortunately, despite the great success, a significant fraction of patients with ICB-responsive cancers fails to respond (primary resistance) or will develop resistance (secondary resistance) (150). Because of the importance of immune checkpoints in preserving tolerance, administration of these therapies often result in the development of irAEs (149, 151, 152). Combinatorial therapeutic strategies, as exemplified by the administration of anti-CTLA-4 + anti-PD1, can increase the number of responder patients, however, at the expense of heightened irAEs, which significantly limit their widespread application (153). Here, we will discuss some potential strategies that leverage knowledge gained from the study of autoimmunity to maximize the efficacy of immunotherapies while minimizing immune-related toxicities.

Response to immunotherapies is not universal, and insights are clearly needed to identify optimal biomarkers of response and mechanisms to combat therapeutic resistance. Biomarkers are indicators that can objectively measure biological and pathological processes and that can also be utilized to evaluate response to immunotherapies. Biomarkers can effectively improve therapeutic decision-making and reduce the risk of drug failure by identifying lack of response early during treatment (154, 155). Biomarkers can also be leveraged to identify patients at risk for developing autoimmune-like toxicities. For example, auto-antibodies (e.g. against insulin or GAD65) can be detected in pre-symptomatic subjects at risk of developing T1D (156). This raises the possibility that detection of such circulating auto-antibodies associated with autoimmune pathologies could be informative as to whether a patient undergoing ICB is developing a potential irAE in a specific organ or tissue.

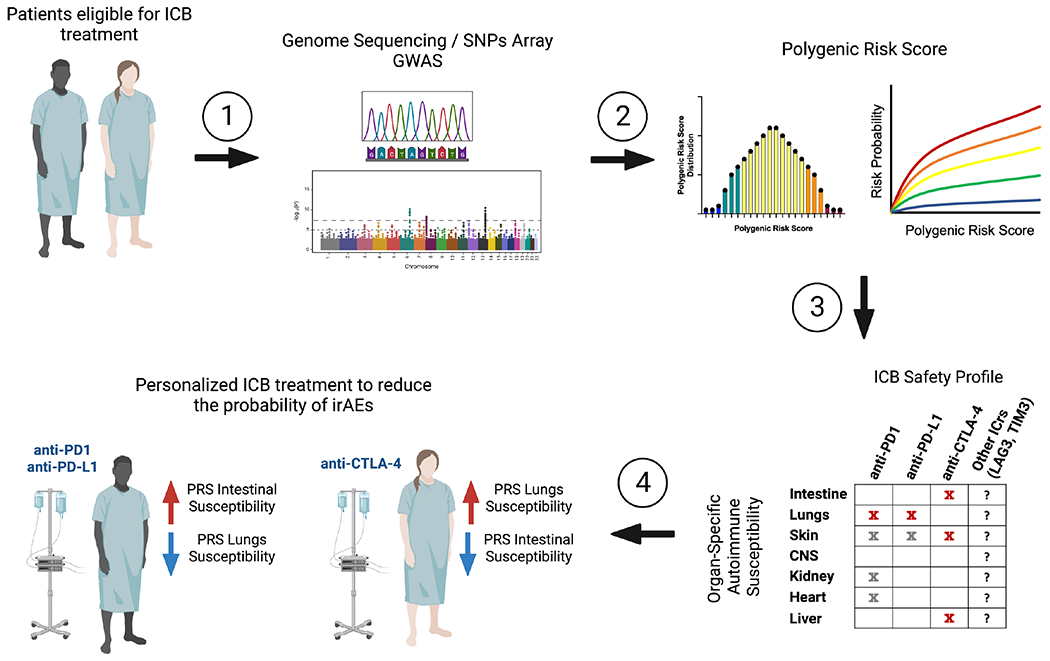

Pharmacogenetics is the study of the genetic factors that determine individual response differences when taking drugs (157). It focuses on the impact of a single candidate gene on drug metabolism and drug response, and recent research has proven that the occurrence of serious adverse drug reactions or treatment failures in some populations have a significant genetic component (158). Similarly, GWAS studies that have been instrumental in discovering genetic associations with autoimmune diseases could be leveraged to identify individuals that are more likely to develop severe irAEs after immunotherapy. Recent investigations have evaluated the feasibility of using GWAS data to make informed therapeutic decisions. GWAS studies were successfully used to identify subjects at high risk for developing cardiotoxicity following treatment with anthracyclines (159) or development of late radiotherapy-induced damage (160). Similar studies are warranted to identify individuals at high risk to develop ICB-induced irAEs, and in addition, to associate genetic variations previously linked with organ-specific or systemic autoimmune diseases with the tissues affected upon ICB (Figure 3). Of note, a considerable hurdle to implement such strategies is the fact that single genetic variants have relatively low predictive power, thus impeding routine use for prevention and screening purposes. It may be possible to overcome this obstacle by computing a polygenic risk score (PRS); a parameter that compiles the estimated effect of many disease-associated alleles to predict genetic predisposition for a given trait (47). A study using this approach to calculate a personalized colorectal cancer (CRC) risk found that a PRS (top 1% score, 2.9-fold increase in CRC risk) performed significantly better than the current age-based screening for CRC (161). Thus, calculation of a PRS for the development of irAEs based on patient genome sequencing data or arrays that detect single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) known to be associated with major autoimmune diseases could be envisioned (Figure 3). In conclusion, improved genomic approaches to predict irAEs and/or improved management strategies for irAEs may allow for a more widespread administration of combinatorial immunotherapies.

Figure 3. Pipeline to identify patients at high-risk to develop immune-related adverse events.

(1) Genome sequencing or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) arrays of patients eligible for immune checkpoint blockade (ICB). (2) The sequenced genome or SNPs arrays are compared to available GWAS for different autoimmune diseases and a polygenic risk score for each autoimmune condition is calculated. (3) The susceptibility of an individual patient to organ-specific autoimmunity is compared with the available data regarding the safety profile of the different ICB therapies. (4) The individual’s genetic susceptibilities guides the choice of ICB therapy with the goal of significantly lowering the incidence of irAEs, thereby maximizing treatment duration and potentially increasing the feasibility of applying combinatorial strategies.

Re-purposing autoimmune interventions to treat irAEs

Immunotherapies can cause irAEs due to non-specific activation of the immune system, and while any organ system can potentially be affected, the most commonly affected organs are the gastrointestinal tract, endocrine glands, skin, joints and liver. irAEs can occur at any time during treatment, and, although rare, even after completion. As the underlying pathophysiology of irAEs is similar to autoimmune processes, some therapeutic interventions utilized to treat autoimmunity can be re-purposed to blunt irAEs (162).

Steroids, specifically glucocorticoids, have been used widely to suppress autoimmune diseases, including RA, MS, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (163). As discussed above, a major effect of glucocorticoids is inhibition of pro-inflammatory genes and induction of immune regulatory genes. Accordingly, glucocorticoids have been the primary treatment to manage irAEs (164). Although low-grade irAEs, such as hypothyroidism, and other endocrine irAEs can be treated with hormone supplementation without glucocorticoid therapy, high-grade irAEs require moderate to high doses of glucocorticoids and possibly other additional immunosuppressants, such as tocilizumab (anti-IL-6) and cyclophosphamide (162, 165). However, the application of glucocorticoids should be carefully managed because of its multiple side effects, including osteoporosis, muscle wasting, gastritis, hypertension, new-onset hyperglycemia, infectious complications, and metabolic disturbances, especially when used at high-doses or administered long-term (166–170). Further, the promotion of T cell dysfunction by glucocorticoids and the association of glucocorticoid response signatures with failure to respond to ICB (97) should be accounted for in their clinical application for patients being treated with ICB. Of note, high-dose glucocorticoid is widely used in glioblastoma (GBM) therapy to reduce tumor-associated vasogenic edema and to prevent or treat increased intracranial pressure. However, the overall survival (OS) and PFS were reduced in GBM patients taking steroids during chemoradiotherapy treatment (171). Thus, the dose and duration of steroid use should be strictly controlled to achieve therapeutic goals while minimizing unwanted effects. Indeed, one study comparing patients receiving either low- or high-dose glucocorticoid for the treatment of irAEs showed that patients who received high-dose glucocorticoid had both reduced survival and time to treatment failure (172).

Inflammatory cytokines are required for immune responses against microbial, viral, and parasitic infections, and cancer; however, they can also be harmful to self-tissue during abnormal immune responses such as in autoimmunity and during irAEs in cancer patients. Both in autoimmune diseases and in some life-threatening steroid-refractory irAEs, biologics directed against inflammatory cytokines have been used to shut down inflammation (173, 174). Biologics can be in the form of an antibody which neutralizes an inflammatory cytokine or blocks its receptors, decoy receptors targeting the cytokine, or a recombinant protein, which can either be a receptor agonist or, alternatively, an antagonist that occupies and prevents receptor binding (175). Biologics targeting TNFα, IL-1, IL-6, IL-17 and IL-23/IL-12 are the most recent approaches (175). Anti-TNFα agents have been successfully used in the treatment of many autoimmune diseases and ICB-related inflammation. For instance, infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal anti-TNFα antibody, has been used widely to induce and maintain remission in patients with IBD, and these agents are also shown to be highly effective for ICB-related glucocorticoid-refractory colitis (176, 177). Similarly, biologics targeting IL-1 and IL-6 have also been used for treatment of both autoimmune diseases and irAEs (166, 178). Biologics interfering with the functions of IFNγ-producing CD4+ T helper 1 (Th1) cells that are induced by IL12 and of Th17 cells that are induced by IL-23 may also be a promising option. In this regard, the anti-IL-23/IL-12 agent, Ustekinumab, which blocks the common p40 subunit of IL-23 and IL-12, is effective for the treatment of psoriasis and arthritis and, thus, may be harnessed to treat patients with cutaneous and rheumatic irAEs (179). Additionally, multiple anti-IL-17 agents, which are expected to be useful in therapy of immune-mediated diseases, are undergoing clinical studies (166, 180). Future approaches should consider tailoring the treatment of irAEs based on the knowledge gathered from the treatment of organ-specific autoimmune diseases while also curbing steroid use, which may limit the efficacy of immunotherapies.

Genetics and environmental triggers

Above, we have focused our attention on the main features of the immune response during cancer and autoimmunity from a T cell perspective. Here, we will briefly highlight recent evidence suggesting how environmental triggers, such as infections, and diet and lifestyle choices, can predispose or protect the host from developing these diseases.

Studies in animal models and humans strongly suggest a correlation between infections and development of autoimmunity or cancer, although through different mechanisms. The strong association of infections with autoimmune diseases, such as MS, RA, and SLE (181), has been linked with a biological phenomenon termed heterologous immunity, which refers to the ability of the immune system to mount a response against one pathogen after exposure to a different pathogen. While this mechanism can be protective by generating a swift cross-reacting response against a new infection, in some instances it can induce severe immunopathology by breaking tolerance to self-antigens (181, 182). For example, EBV-specific CD4+ T cells from MS patients have been shown to cross-react with myelin antigens, but not with non-myelin self-antigens (183). Indeed, a recent large-scale study supports a causal relationship between EBV infection and MS development (184, 185).

Viral infections can also trigger cancer by multiple mechanisms; (i) induction of neoplastic transformation through the activation of oncogenic pathways (186, 187), (ii) establishment of a chronic inflammatory state that predisposes to malignant transformation (188, 189), and (iii) induction of an immune-suppressive state that hinders cancer immunosurveillance (190). However, some virus-specific responses can be beneficial to boost antitumor responses as presence of viral antigens or tumor-specific activation of endogenous retroviruses has been associated with heightened anti-tumor T and NK cell-mediated cytolytic activity (191). Of note, anti-viral immunity plays a role in cancer that goes beyond cross-reactivity; bystander virus-specific memory T cells can be found in the TME and can participate in anti-tumor responses when re-activated upon immunotherapeutic interventions to produce pro-inflammatory factors and/or kill tumor cells in an antigen-independent manner (192–195). Thus, novel strategies can be devised to leverage both virus-specific (for virus-associated cancers) and tumor antigen-independent T cell responses to eradicate tumors. Altogether, more work is needed to better understand the molecular mechanisms underlying heterologous immunity and T cell cross-reactivity to shed light on autoimmune etiopathology and inform novel anti-cancer therapies.

Accumulating evidence supports a critical role of diet on the development of autoimmunity and cancer. The so-called Western diet and lack of physical activity are the main causes of the ongoing obesity pandemic. Obesity has a profound impact on the development of several autoimmune diseases and cancer (196–198), and severely impairs the efficacy of therapeutic strategies. High-sugar, high-fat diets generate systemic hormonal and metabolic dysregulation, which strongly affect the homeostatic activities of different immune populations. Such dysregulation can lead to a persistent inflammatory state which can paradoxically predispose to development of both autoimmunity, by disrupting the physiological mechanisms that keep self-reactive T cells in check, and cancer, by generating mutagenic oxidative stress and impairing tissue immunosurveillance mechanisms (199–203). Dietary regimens also affect the commensal microbiome, which has been suggested to play a prominent role in susceptibility to autoimmunity (139). Microbial molecular mimicry can trigger autoimmune reactions and, moreover, microbial-derived metabolites can modulate autoimmune disease course (204). At the other end of the immune spectrum, the microbiota can predispose to cancer development (205), and determine response to ICB (206). Antibiotic use has been associated with a loss of microbial diversity and impairment of ICB efficacy in humans. Indeed, studies in preclinical models have shown that the presence of certain bacterial species increased the recruitment of Th1-like CD4+ T cells to the tumor bed from the small intestine and increased antigen-presentation by DCs, leading to heightened priming and intra-tumoral accumulation of CD8+ T cells (207, 208).

Concluding remarks

Therapies targeting T cells in both autoimmunity and cancer have shown much success. However, we propose that to design more effective therapeutic approaches, we need to leverage information gleaned from the study of both these diseases. Although T cell responses in autoimmunity and cancer are seemingly opposing, we have discussed some unifying threads that can be exploited to improve the therapeutic efficacy of immunotherapies and their clinical management. We propose that future studies need to account for how the natural cycle of T cell responses is disrupted in order to mitigate the inability to re-establish homeostasis and generate memory. Wholistic approaches that take into account diet and lifestyle choices are also critical. The wealth of knowledge coming from large GWAS studies should be used not only to understand the molecular pathways involved in autoimmunity and cancer, but also to inform personalized strategies to maximize therapeutic efficacy while reducing the risk of irAEs. Lastly, organism-wide studies will be required to potentially identify organ-specific checkpoints which may be leveraged to break the paradigm and elicit antitumor responses without autoimmunity. We are just at the beginning of the immunotherapy revolution and studying the convergence of discoveries in the autoimmunity and cancer fields can endow us with novel means to exploit the immune system intelligently to improve the life of all patients suffering from these devastating diseases.

Acknowledgments

Work in the author’s laboratory (A.C.A.) is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01CA187975; R01CA229400; PO1CA236749; CA246653) and the Melanoma Research Alliance (824733). A.C.A. is a recipient of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital President’s Scholar Award. D.M. is supported by SNSF postdoc mobility (P400PB_183910). Figures were created with BioRender.com.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

A.C.A. is a member of the SAB for Tizona Therapeutics, Trishula Therapeutics, Compass Therapeutics, Zumutor Biologics, ImmuneOncia, and Nekonal Sarl. A.C.A. is also a paid consultant for iTeos Therapeutics, Larkspur Biosciences, and Excepgen. A.C.A.’s interests were reviewed and managed by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Partners Healthcare in accordance with their conflict-of-interest policies.

T cells are critical mediators of autoimmunity and cancer. Mangani, Yang, and Anderson review the current knowledge of the T cell response in autoimmunity and cancer and discuss how a better understanding of the nexus of these two fields can improve the application and efficacy of immunotherapies.

References

- 1.Bouneaud C, Kourilsky P, Bousso P. Impact of negative selection on the T cell repertoire reactive to a self-peptide: a large fraction of T cell clones escapes clonal deletion. Immunity. 2000;13(6):829–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ElTanbouly MA, Noelle RJ. Rethinking peripheral T cell tolerance: checkpoints across a T cell’s journey. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(4):257–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu W, Jiang N, Ebert PJ, Kidd BA, Muller S, Lund PJ, et al. Clonal Deletion Prunes but Does Not Eliminate Self-Specific alphabeta CD8(+) T Lymphocytes. Immunity. 2015;42(5):929–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsieh CS, Liang Y, Tyznik AJ, Self SG, Liggitt D, Rudensky AY. Recognition of the peripheral self by naturally arising CD25+ CD4+ T cell receptors. Immunity. 2004;21(2):267–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsieh CS, Zheng Y, Liang Y, Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY. An intersection between the self-reactive regulatory and nonregulatory T cell receptor repertoires. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(4):401–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunkow ME, Jeffery EW, Hjerrild KA, Paeper B, Clark LB, Yasayko SA, et al. Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat Genet. 2001;27(1):68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(2):191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F, Brunkow ME, Ferguson PJ, Whitesell L, et al. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet. 2001;27(1):20–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viglietta V, Baecher-Allan C, Weiner HL, Hafler DA. Loss of functional suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2004;199(7):971–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugiyama H, Gyulai R, Toichi E, Garaczi E, Shimada S, Stevens SR, et al. Dysfunctional blood and target tissue CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells in psoriasis: mechanism underlying unrestrained pathogenic effector T cell proliferation. J Immunol. 2005;174(1):164–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindley S, Dayan CM, Bishop A, Roep BO, Peakman M, Tree TI. Defective suppressor function in CD4(+)CD25(+) T-cells from patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54(1):92–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen ML, Pittet MJ, Gorelik L, Flavell RA, Weissleder R, von Boehmer H, et al. Regulatory T cells suppress tumor-specific CD8 T cell cytotoxicity through TGF-beta signals in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(2):419–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakuishi K, Ngiow SF, Sullivan JM, Teng MW, Kuchroo VK, Smyth MJ, et al. TIM3(+)FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells are tissue-specific promoters of T-cell dysfunction in cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(4):e23849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu L, Cantor H. Generation and regulation of CD8(+) regulatory T cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2008;5(6):401–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Zaslavsky M, Su Y, Guo J, Sikora MJ, van Unen V, et al. KIR(+)CD8(+) T cells suppress pathogenic T cells and are active in autoimmune diseases and COVID-19. Science. 2022;376(6590):eabi9591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HJ, Barnitz RA, Kreslavsky T, Brown FD, Moffett H, Lemieux ME, et al. Stable inhibitory activity of regulatory T cells requires the transcription factor Helios. Science. 2015;350(6258):334–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filaci G, Fenoglio D, Fravega M, Ansaldo G, Borgonovo G, Traverso P, et al. CD8+ CD28− T regulatory lymphocytes inhibiting T cell proliferative and cytotoxic functions infiltrate human cancers. J Immunol. 2007;179(7):4323–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vignali PDA, DePeaux K, Watson MJ, Ye C, Ford BR, Lontos K, et al. Hypoxia drives CD39-dependent suppressor function in exhausted T cells to limit antitumor immunity. Nat Immunol. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim HJ, Cantor H. Regulation of self-tolerance by Qa-1-restricted CD8(+) regulatory T cells. Semin Immunol. 2011;23(6):446–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang H, Kashleva H, Xu LX, Forman J, Flaherty L, Pernis B, et al. T cell vaccination induces T cell receptor Vbeta-specific Qa-1-restricted regulatory CD8(+) T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(8):4533–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang H, Curran S, Ruiz-Vazquez E, Liang B, Winchester R, Chess L. Regulatory CD8+ T cells fine-tune the myelin basic protein-reactive T cell receptor V beta repertoire during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(14):8378–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Panoutsakopoulou V, Huster KM, McCarty N, Feinberg E, Wang R, Wucherpfennig KW, et al. Suppression of autoimmune disease after vaccination with autoreactive T cells that express Qa-1 peptide complexes. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(8):1218–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu D, Ikizawa K, Lu L, Sanchirico ME, Shinohara ML, Cantor H. Analysis of regulatory CD8 T cells in Qa-1-deficient mice. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(5):516–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang H, Canfield SM, Gallagher MP, Jiang HH, Jiang Y, Zheng Z, et al. HLA-E-restricted regulatory CD8(+) T cells are involved in development and control of human autoimmune type 1 diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(10):3641–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Correale J, Villa A. Isolation and characterization of CD8+ regulatory T cells in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;195(1–2):121–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saligrama N, Zhao F, Sikora MJ, Serratelli WS, Fernandes RA, Louis DM, et al. Opposing T cell responses in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nature. 2019;572(7770):481–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller MR, Rao A. NFAT, immunity and cancer: a transcription factor comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(9):645–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vallabhapurapu S, Karin M. Regulation and function of NF-kappaB transcription factors in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:693–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeSilva DR, Feeser WS, Tancula EJ, Scherle PA. Anergic T cells are defective in both jun NH2-terminal kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. J Exp Med. 1996;183(5):2017–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li W, Whaley CD, Mondino A, Mueller DL. Blocked signal transduction to the ERK and JNK protein kinases in anergic CD4+ T cells. Science. 1996;271(5253):1272–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, Iwamoto Y, Berezovskaya A, Boussiotis VA. A pathway regulated by cell cycle inhibitor p27Kip1 and checkpoint inhibitor Smad3 is involved in the induction of T cell tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(11):1157–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez GJ, Pereira rM, Aijo T, Kim EY, Marangoni F, Pipkin ME, et al. The transcription factor NFAT promotes exhaustion of activated CD8(+) T cells. Immunity. 2015;42(2):265–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abe BT, Shin DS, Mocholi E, Macian F. NFAT1 supports tumor-induced anergy of CD4(+) T cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72(18):4642–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mognol GP, Spreafico R, Wong V, Scott-Browne JP, Togher S, Hoffmann A, et al. Exhaustion-associated regulatory regions in CD8(+) tumor-infiltrating T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(13):E2776–E85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Leun AM, Thommen DS, Schumacher TN. CD8(+) T cell states in human cancer: insights from single-cell analysis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(4):218–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thommen DS, Schumacher TN. T Cell Dysfunction in Cancer. Cancer cell. 2018;33(4):547–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Escobar G, Mangani D, Anderson AC. T cell factor 1: A master regulator of the T cell response in disease. Sci Immunol. 2020;5(53). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Philip M, Schietinger A. CD8(+) T cell differentiation and dysfunction in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22(4):209–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schietinger A, Philip M, Krisnawan VE, Chiu EY, Delrow JJ, Basom RS, et al. Tumor-Specific T Cell Dysfunction Is a Dynamic Antigen-Driven Differentiation Program Initiated Early during Tumorigenesis. Immunity. 2016;45(2):389–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maeda Y, Nishikawa H, Sugiyama D, Ha D, Hamaguchi M, Saito T, et al. Detection of self-reactive CD8(+) T cells with an anergic phenotype in healthy individuals. Science. 2014;346(6216): 1536–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zitvogel L, Perreault C, Finn OJ, Kroemer G. Beneficial autoimmunity improves cancer prognosis. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(9):591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei X, Chen F, Xin K, Wang Q, Yu L, Liu B, et al. Cancer-Testis Antigen Peptide Vaccine for Cancer Immunotherapy: Progress and Prospects. Transl Oncol. 2019;12(5):733–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas R, Al-Khadairi G, Roelands J, Hendrickx W, Dermime S, Bedognetti D, et al. NY-ESO-1 Based Immunotherapy of Cancer: Current Perspectives. Front Immunol. 2018;9:947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borghans JAM, Keşmir C, De Boer RJ. MHC diversity in Individuals and Populations. In: Flower D, Timmis J, editors. In Silico Immunology. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2007. p. 177–95. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernando MM, Stevens CR, Walsh EC, De Jager PL, Goyette P, Plenge RM, et al. Defining the role of the MHC in autoimmunity: a review and pooled analysis. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(4):e1000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matzaraki V, Kumar V, Wijmenga C, Zhernakova A. The MHC locus and genetic susceptibility to autoimmune and infectious diseases. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sud A, Kinnersley B, Houlston RS. Genome-wide association studies of cancer: current insights and future perspectives. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017; 17(11):692–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gough SC, Simmonds MJ. The HLA Region and Autoimmune Disease: Associations and Mechanisms of Action. Curr Genomics. 2007;8(7):453–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krovi SH, Kuchroo VK. Activation pathways that drive CD4(+) T cells to break tolerance in autoimmune diseases(). Immunol Rev. 2022;307(1):161–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Z, Derkach A, Yu KJ, Yeager M, Chang YS, Chen CJ, et al. Patterns of Human Leukocyte Antigen Class I and Class II Associations and Cancer. Cancer Res. 2021;81 (4): 1148–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sawai H, Nishida N, Khor SS, Honda M, Sugiyama M, Baba N, et al. Genome-wide association study identified new susceptible genetic variants in HLA class I region for hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):7958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sud A, Thomsen H, Law PJ, Forsti A, Filho M, Holroyd A, et al. Genome-wide association study of classical Hodgkin lymphoma identifies key regulators of disease susceptibility. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Timofeeva MN, Hung RJ, Rafnar T, Christiani DC, Field JK, Bickeboller H, et al. Influence of common genetic variation on lung cancer risk: meta-analysis of 14 900 cases and 29 485 controls. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(22):4980–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu L, Wang J, Cai Q, Cavazos TB, Emami NC, Long J, et al. Identification of Novel Susceptibility Loci and Genes for Prostate Cancer Risk: A Transcriptome-Wide Association Study in Over 140,000 European Descendants. Cancer Res. 2019;79(13):3192–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Law PJ, Timofeeva M, Fernandez-Rozadilla C, Broderick P, Studd J, Fernandez-Tajes J, et al. Association analyses identify 31 new risk loci for colorectal cancer susceptibility. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pociot F, Lernmark A. Genetic risk factors for type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2016;387(10035):2331–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waldner H, Whitters MJ, Sobel RA, Collins M, Kuchroo VK. Fulminant spontaneous autoimmunity of the central nervous system in mice transgenic for the myelin proteolipid protein-specific T cell receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(7):3412–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jager A, Dardalhon V, Sobel RA, Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK. Th1, Th17, and Th9 effector cells induce experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with different pathological phenotypes. J Immunol. 2009;183(11):7169–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kouskoff V, Korganow AS, Duchatelle V, Degott C, Benoist C, Mathis D. Organ-specific disease provoked by systemic autoimmunity. Cell. 1996;87(5):811–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taneja V, Taneja N, Paisansinsup T, Behrens M, Griffiths M, Luthra H, et al. CD4 and CD8 T cells in susceptibility/protection to collagen-induced arthritis in HLA-DQ8-transgenic mice: implications for rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 2002;168(11):5867–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hill JA, Bell Da, Brintnell W, Yue D, Wehrli B, Jevnikar AM, et al. Arthritis induced by posttranslationally modified (citrullinated) fibrinogen in DR4-IE transgenic mice. J Exp Med. 2008;205(4):967–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alzabin S, Williams RO. Effector T cells in rheumatoid arthritis: lessons from animal models. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(23):3649–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spitzer MH, Carmi Y, Reticker-Flynn NE, Kwek SS, Madhireddy D, Martins MM, et al. Systemic Immunity Is Required for Effective Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;168(3):487–502 e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zander R, Schauder D, Xin G, Nguyen C, Wu X, Zajac A, et al. CD4(+) T Cell Help Is Required for the Formation of a Cytolytic CD8(+) T Cell Subset that Protects against Chronic Infection and Cancer. Immunity. 2019;51(6):1028–42 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ferris ST, Durai V, Wu R, Theisen DJ, Ward JP, Bern MD, et al. cDC1 prime and are licensed by CD4(+) T cells to induce anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2020;584(7822):624–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cachot A, Bilous M, Liu YC, Li X, Saillard M, Cenerenti M, et al. Tumor-specific cytolytic CD4 T cells mediate immunity against human cancer. Sci Adv. 2021;7(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Garaud S, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Willard-Gallo K. T follicular helper and B cell crosstalk in tertiary lymphoid structures and cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tooley KA, Escobar G, Anderson AC. Spatial determinants of CD8(+) T cell differentiation in cancer. Trends Cancer. 2022;8(8):642–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tay RE, Richardson EK, Toh HC. Revisiting the role of CD4(+) T cells in cancer immunotherapy-new insights into old paradigms. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021;28(1-2):5–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Borst J, Ahrends T, Babala N, Melief CJM, Kastenmuller W. CD4(+) T cell help in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(10):635–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oh DY, Fong L. Cytotoxic CD4(+) T cells in cancer: Expanding the immune effector toolbox. Immunity. 2021;54(12):2701–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schnell A, Bod L, Madi A, Kuchroo VK. The yin and yang of co-inhibitory receptors: toward anti-tumor immunity without autoimmunity. Cell Res. 2020;30(4):285–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tivol EA, Borriello F, Schweitzer AN, Lynch WP, Bluestone JA, Sharpe AH. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity. 1995;3(5):541–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Waterhouse P, Penninger JM, Timms E, Wakeham A, Shahinian A, Lee KP, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in Ctla-4. Science. 1995;270(5238):985–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kuehn HS, Ouyang W, Lo B, Deenick EK, Niemela JE, Avery DT, et al. Immune dysregulation in human subjects with heterozygous germline mutations in CTLA4. Science. 2014;345(6204):1623–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Krummel MF, Allison JP. CD28 and CTLA-4 have opposing effects on the response of T cells to stimulation. J Exp Med. 1995;182(2):459–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wing K, Onishi Y, Prieto-Martin P, Yamaguchi T, Miyara M, Fehervari Z, et al. CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science. 2008;322(5899):271–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:677–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fife BT, Guleria I, Gubbels Bupp M, Eagar TN, Tang Q, Bour-Jordan H, et al. Insulin-induced remission in new-onset NOD mice is maintained by the PD-1-PD-L1 pathway. J Exp Med. 2006;203(12):2737–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ogishi M, Yang R, Aytekin C, Langlais D, Bourgey M, Khan T, et al. Inherited PD-1 deficiency underlies tuberculosis and autoimmunity in a child. Nat Med. 2021;27(9):1646–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anderson AC, Joller N, Kuchroo VK. Lag-3, Tim-3, and TIGIT: Co-inhibitory Receptors with Specialized Functions in Immune Regulation. Immunity. 2016;44(5):989–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]