Abstract

Objective:

Psychological factors (e.g., depression, anxiety) are known to contribute to the development and maintenance of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Less is known, however, about the role of positive psychological well-being (PPWB) in IBS. Accordingly, we completed a systematic review of the literature examining relationships between PPWB and clinical characteristics in IBS.

Method:

A systematic review using search terms related to PPWB and IBS from inception through July 28, 2022, was completed. Quality was assessed with the NIH Quality Assessment Tool. A narrative synthesis of findings, rather than meta-analysis, was completed due to study heterogeneity.

Results:

22 articles with a total of 4,285 participants with IBS met inclusion criteria. Individuals with IBS had lower levels of PPWB (e.g., resilience, positive affect, self-efficacy, emotion regulation) compared to healthy populations, which in turn was associated with reduced physical and mental health and health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Limited exploration of potential biological mechanisms underlying these relationships has been described.

Conclusions:

PPWB is diminished in individuals with IBS compared to other populations, and greater PPWB is linked to superior physical, psychological, and HRQoL outcomes. Interventions to increase PPWB may have the potential to improve IBS-related outcomes.

Keywords: Psychology, Positive; Irritable Bowel Syndrome; Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders; Psychosomatic medicine

1. Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), characterized by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits, is the most common1 and widely studied2 disorder of gut-brain interaction (DGBI; also known as functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder), and is thought to arise from complex interactions between biological, psychological, and social factors.3 Relationships between IBS and psychological disorders have been extensively examined.4 It is estimated that at least half of all patients with IBS have at least one comorbid psychiatric condition.5 Of these, anxiety disorders are the most common, with prevalence estimates ranging from approximately 30-50%,3,6 followed by depressive disorders, with rates ranging from 25-30%.3,6 Not only do self-reported anxiety and depression appear to confer a two-fold increased risk for IBS onset,7 but early research suggests that DGBI and anxiety/mood disorders have shared genetic susceptibilities.8 There is also evidence that comorbid psychiatric symptoms intensify GI symptomatology, heighten visceral hypersensitivity, and worsen quality of life.6,9,10 Additionally, negative psychological constructs and other personality factors – distinct from depressive and anxiety symptoms – such as catastrophizing, symptom hypervigilance, avoidance, perceived stress, pessimism, neuroticism, and alexithymia, have also been extensively studied and shown to exacerbate and maintain IBS symptomatology.3,4,11

Less is known, however, about the role of positive psychological well-being (PPWB) in IBS. PPWB is comprised of a variety of positive psychological (PP) constructs, such as purpose in life, resilience, positive affect, optimism, and happiness, among others.12 PP constructs have been linked to better health, including lower levels of pain, fewer physical symptoms, and longer survival, in both healthy individuals and those suffering from chronic medical conditions, such as coronary artery disease and chronic pain syndromes.13-16 Importantly, PPWB is not simply the absence of psychopathology; correlations between PP constructs and symptoms of depression and anxiety are typically small to moderate.17 Additionally, PP constructs are significantly associated with both health behavior adherence and health outcomes, independent of negative psychological constructs.16,18,19 Early research also demonstrates that interventions comprised of simple exercises to cultivate PP constructs show promise in their ability to improve well-being,17,20 reduce distress/depressive symptoms,17,20 promote health behaviors,21,22 and improve targeted health outcomes, such as pain.23 Based on these findings, as well as an emerging literature suggesting that PP constructs may also be important in IBS symptom management,24 experts in the field of psychogastroenterology25 have suggested ways in which PP interventions might be integrated into routine IBS clinical care.24,26

Accordingly, in this systematic review, we aim to summarize the existing literature examining PP constructs in participant samples with IBS to identify: (1) relationships between PP constructs and presence of IBS, including comparisons to other populations; (2) whether PP constructs relate to physical health, mental health, and/or quality of life in patients with IBS; and (3) if any biological mechanisms might explain or contribute to these observed relationships.

2. Methods

2.1. Guidance and registration

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.27 It was registered on the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on March 22, 2022 (CRD42022304767).

2.2. Study eligibility

Peer-reviewed observational cohort, cross-sectional, and case-control studies assessing PP constructs in individuals with IBS were eligible for inclusion. Study protocols, pre-published or incomplete data (e.g., conference abstracts), unpublished dissertations or theses, non-empirical publications (e.g., editorials, commentaries), reviews, and texts unavailable in the English language were excluded.

2.3. Search strategy

This review included searches within the following databases: Embase; PsycINFO; PubMed; MEDLINE; Web of Science; Google Scholar (first 200 references). This combination of databases was selected to support an optimal literature search.28 Studies published from inception through July 28, 2022, were included. References of included studies were also reviewed. The search strategy aimed to identify the targeted studies by requiring at least one positive psychology-related term and one IBS-related term (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search terms

| Databases | Positive psychology terms | IBS-related terms |

|---|---|---|

| Embase | “Positive-psycho*,” OR “joy,” OR “resilience,” OR “positive-affect,” OR “optimism,” OR “happiness,” OR “happy,” OR “gratitude,” OR “kindness,” OR “forgive*,” OR "psychology, positive," “self-regulat*,” OR “grit,” OR “self-compassion,” OR “self-efficacy,” OR “mastery” | “Irritable bowel syndrome” OR “IBS” |

| Google Scholar (first 200 references) | ||

| MEDLINE | ||

| PsycINFO | ||

| PubMed | ||

| Web of Science |

2.4. Study Selection Process

Eligible studies were imported into Covidence online software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia; https://www.covidence.org) and duplicates were removed. All titles and abstracts (n=888) and all full texts (n=73) were each screened twice by two independent reviewers (E.N.M., H.B.M., M.S., L.E.H., R.M.L., H.L.A., J.J.). Disagreements were adjudicated by an independent reviewer (C.M.C.).

2.5. Data extraction

Data were extracted twice by two independent reviewers (E.N.M., M.S., L.E.H., R.M.L., H.L.A., J.Z., E.H.F., R.A.M., H.B.M.) with disagreements resolved through discussion to achieve consensus. Data extracted from each study included: sample size, study design, participant characteristics and demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, population type/medical diagnosis), IBS diagnostic criteria, PP construct examined and measurement type, statistical analysis, and PP-related findings and study results.

2.6. Risk of bias and quality assessment

Risk of bias was independently judged for each article by two reviewers (E.N.M., M.S., L.E.H., R.M.L., H.L.A., J.Z., E.H.F., R.A.M., H.B.M.) using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.29 This tool assesses risk of bias based on 14 questions examining: clarity of research question; study population definition; uniform use of inclusion/exclusion criteria; sample size justification; timing of exposure assessment (i.e., prior to outcome measurement); sufficient timeframe to see an effect; different levels of the exposure of interest; exposure measures and assessment; repeated exposure assessment; outcome measures; blinding of outcome assessors; follow-up rate; and statistical analyses. A summarized quality rating (good, fair, or poor) was then generated, consistent with prior studies.30 Disagreements were resolved by the first author (E.N.M.) with assistance from the senior author (C.M.C.) as needed.

2.7. Data analysis and synthesis

The heterogeneity of studies (in terms of study design, outcome, and measurement) and the limited number of studies in each category precluded a meta-analysis. As such, a narrative synthesis of the findings of the systematic review was performed, following the Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) guideline to improve transparency.31

3. Results

3.1. Participant and study characteristics

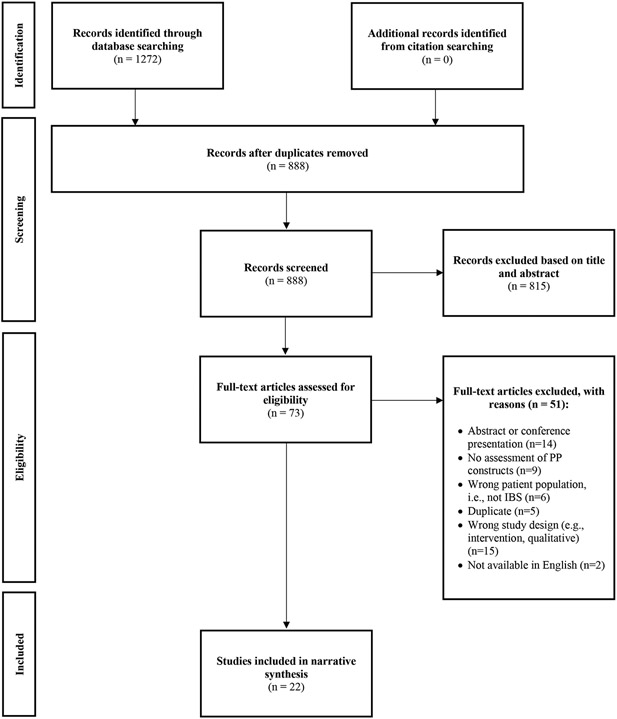

Figure 1 displays the PRISMA flow diagram for study inclusion. A total of 22 studies, published between 2008 and 2022, fulfilled the inclusion criteria for narrative synthesis (Table 2). Of the 22 studies included, all had a cross-sectional (n=21) or observational cohort (n=1) study design. Across included studies, the total number of participants was 8,837; sample sizes for IBS participants ranged from 50 to 820, and the total number of participants with IBS was 4,285. Twenty-one studies included adult participants aged 18 years or older, and one included adolescent participants between the ages of 14 and 15 years. Seventy-four percent of included participants were women, consistent with the roughly 2.5:1 female-to-male ratio among individuals with IBS.32 Among included studies, resilience was the most common PP construct examined (n=7), followed by self-efficacy (n=4), positive coping skills (n=4), positive psychological well-being (n=3), positive affect (n=2), emotion regulation (n=2), sense of coherence (n=2), optimism (n=1), self-compassion (n=1), positive cognitions regarding one’s illness (n=1), interpersonal forgiveness (n=1), humor (n=1), self-esteem (n=1), and hardiness (n=1). Most studies (n=16) utilized a version of the Rome criteria2 to confirm IBS diagnosis; the remaining studies used clinician diagnosis (n=3), self-report (n=2), or did not specify (n=1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search

Table 2.

Summary of studies examining relationships between PP constructs and IBS.

| Study | Study Design |

Sample size (N) | Sample characteristics |

Assessment of IBS |

Assessment of PP construct |

Findings | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ben Ezra et al., 201557 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 103 | IBS (all subtypes):

|

GI clinician diagnosis |

|

|

Good |

| Bhatt et al., 202250 | Observational cohort | IBS: 60 | IBS (all subtypes):

|

Rome III criteria |

|

|

Good |

| Chen et al, 202254 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 80 Note: participants with other chronic pain conditions (e.g., fibromyalgia) were excluded. |

IBS (all subtypes):

|

Healthcare provider diagnosis of IBS |

|

|

Good |

| Dabek-Drobny et al., 202035 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 94 Controls (healthy): 35 |

Overall age (mean, yrs): 30.7 +/−8.3 IBS (all subtypes):

Controls:

|

Rome IV criteria |

|

|

Fair |

| Endo et al., 201141 | Cross-sectional | IBS:

Controls (healthy):

|

IBS (all subtypes): Study 1:

Controls: Study 1:

|

Rome II criteria |

|

|

Good |

| Eriksson et al., 200863 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 80

Controls (healthy): 21 |

IBS (all subtypes):

Controls:

|

Rome II criteria and clinician diagnosis |

|

|

Good |

| Farhadi et al., 201844 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 91 Other GI symptoms: 134 Controls (no GI symptoms): 191 |

IBS (all subtypes):

GI symptoms:

Controls:

|

Rome IV criteria |

|

|

Good |

| Mazaheri et al., 201555 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 123 | IBS (all subtypes):

|

Rome III criteria |

|

|

Good |

| Melchior et al, 202262 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 314

|

IBS (all subtypes):

|

Rome II or III criteria |

|

|

Good |

| Park et al., 201833 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 154 Controls (healthy): 102 |

IBS (all subtypes):

Controls:

|

Rome III criteria |

|

|

Good |

| Parker et al., 202136 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 820 Controls (general population, including 95 individuals with other chronic GI conditions): 1026 |

IBS (all subtypes):

Controls (general population):

|

Rome III or IV criteria or physician-made diagnosis |

|

|

Good |

| Potter et al., 202056 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 144 | IBS (all subtypes):

|

Rome III criteria |

|

|

Good |

| Quek et al., 202145 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 305 Controls (without IBS): 2024 |

IBS (all subtypes):

Controls:

|

Self-report |

|

|

Fair |

| Selvi & Bozo, 202249 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 105 Controls (without IBS): 105, randomly selected from 687 |

IBS (all subtypes):

Controls:

|

Rome III criteria |

|

|

Good |

| Shahdadi et al., 201734 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 50 Controls (healthy): 50 |

IBS (all subtypes):

Controls:

|

Undergoing medical treatment for IBS |

|

|

Good |

| Sibelli et al., 201851 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 558 | IBS (all subtypes):

Note: Participants had refractory IBS, defined by IBS-SSS score of 75 or more despite being offered first-line therapies and a symptom duration of at least 12 months. |

Rome III criteria |

|

|

Good |

| Sugawara et al., 201759 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 58 | IBS (all subtypes):

|

Rome III criteria |

|

|

Good |

| Taft et al., 201142 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 269 IBD: 227 | IBS (all subtypes)

IBD:

|

Self-report |

|

|

Good |

| Torkzadeh et al., 201952 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 95 | IBS (all subtypes):

|

Rome III criteria applied by a GI or internal medicine physician |

|

|

Good |

| Voci et al., 200947 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 144

|

IBS (all subtypes):

|

Rome III criteria |

|

|

Fair |

| Wilpart et al., 201758 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 216 | IBS (all subtypes):

|

Rome II Criteria |

|

|

Fair |

| Zarpour & Besharat, 201037 | Cross-sectional | IBS: 60 Controls (healthy): 104 |

IBS (all subtypes):

Controls:

|

Not specified |

|

|

Fair |

Note: PP=positive psychological. IBS=Irritable bowel syndrome. IBS-D=diarrhea subtype. IBS-C=constipation subtype. IBS-M=mixed subtype. IBS-U=unspecified subtype. IBS-A=alternating subtype (Rome II). GI=gastrointestinal. IBS-QOL=IBS-Quality of Life. ACTH=adrenocorticotropic hormone.

3.2. Risk of bias assessment

Summarized quality ratings generated by the NIH Quality Assessment tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies29 are displayed in Table 2. Seventeen studies were rated as having good quality, five studies were rated as having fair quality, and no studies were rated as having poor quality. The most common concerns identified were: only a single exposure assessment (n=21); lack of sample size justification (n=18); unclear reporting of eligible person participation rate (n=14); lack of blinding of participants’ exposure status (n=12); lack of statistical adjustment for potential confounding variables (n=7).

3.3. Outcomes of included studies

Included study findings can be summarized into the following categories: (1) comparison of PP constructs between IBS and other populations; (2) relationships between PP constructs and outcomes of interest including physical health, mental health, and quality of life in individuals with IBS; and (3) biological mechanisms that might underlie or contribute to these observed relationships.

3.3.1. Comparison of PP constructs between IBS and other populations

Thirteen studies compared PP constructs between patients with IBS and other populations. Five studies compared resilience between individuals with IBS and other populations. Of these, four found that resilience was significantly lower in patients with IBS compared to healthy controls,33-36 and one found that average resilience scores were lower, but the difference was not significant.37 To measure resilience, four studies utilized the validated Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC),38 and of these, two additionally utilized the validated Brief Resilience Scale (BRS)39 The fifth study utilized the 25-item Resilience Coping Scale.40

Three studies compared self-efficacy between individuals with IBS and other populations. Two studies found that individuals with IBS scored significantly lower on measures of self-efficacy than healthy controls35,41 Notably, one of these studies was in adults35 and the other study looked at adolescents aged 14 and 15 years in two separate studies reported within the same paper, additionally finding no sex-related differences in self-efficacy among adolescents.41 The third study found no significant differences in self-efficacy between individuals with IBS and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but did not compare individuals with IBS to healthy controls.42 All three studies measured self-efficacy with the validated Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES).43

Three studies compared levels of well-being between IBS and other populations. The first found that the average subjective well-being score, as well as several other well-being attributes, including having adequate pleasure in life, feeling accepted by others, living in peace, believing in fairness in life, being successful, and overall happiness, were significantly lower in individuals with IBS compared to both individuals with GI symptoms but without IBS and compared to healthy controls (without any GI symptoms)44 The second study found that mean scores for some components of well-being – including positive relations with others, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and acceptance – were significantly lower in women with IBS compared to healthy women34 Lastly, the third study found that individuals with self-reported IBS had significantly worse psychological, emotional, and social well-being compared to individuals without IBS in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.45

The three final studies comparing PP constructs to other populations examined positive affect, emotion regulation, and self-esteem, respectively. The study examining levels of positive affect (measured by the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)46) found that levels of positive affect were significantly lower and levels of negative affect were significantly higher among IBS individuals than in normative samples.47 The study examining emotion regulation (measured by the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation scale48) found that participants with IBS reported significantly greater difficulty in emotion regulation than healthy controls.49 And lastly, the study examining self-esteem found that patients with IBS reported higher levels of self-esteem than patients with IBD; the self-esteem scores, however, were not compared to healthy controls.42

3.3.2. Relationships between PP constructs and other aspects of physical health, mental health, and health-related quality of life.

Physical health.

Seven studies identified relationships between PP constructs and aspects of physical health. Six studies identified relationships between PP constructs and IBS symptom severity. Of these, two studies found that lower levels of resilience (as measured by the BRS and CD-RISC), were associated with significantly higher IBS symptom severity.33,36 A third study found that patients whose IBS symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain) did not improve at 3 months had higher scores on the CD-RISC persistence subscale, while patients whose IBS symptoms improved at 3 months had higher scores on the CD-RISC adaptability subscale.50 A fourth study found that lower levels of positive affect correlated with worse IBS symptom severity, and that positive affect mediated the relationship between other negative or adverse psychological traits/conditions (i.e., negative beliefs about emotions, an impoverished emotional experience) and IBS symptom severity.51 The fifth study found that greater optimistic coping was correlated with lower IBS symptom severity in unadjusted, but not adjusted analyses, accounting for sociodemographic factors and other factors associated with IBS symptom severity (e.g., anxiety, depression, other coping strategies).52 The sixth study found that improved emotional well-being was associated with a lower likelihood of worsening IBS symptom severity (based on a single-item question) during the COVID-19 pandemic in multivariable analyses.45 Lastly, another study examined the relationship between self-efficacy and pain severity and interference, finding that reduced self-efficacy was significantly associated with greater pain interference (as measured by the Brief Pain Inventory53).54 No other measures of physical health, other than IBS symptom severity or pain severity/interference, were examined among included studies.

Mental health and other psychological characteristics.

Ten studies identified relationships between PP constructs and other aspects of mental health among individuals with IBS. Five of these studies examined relationships between different PP constructs, and seven of these studies examined relationships between PP constructs and psychopathology or maladaptive traits/conditions.

Of the five studies examining relationships between different PP constructs among individuals with IBS, there were a few key findings. First, hardiness (i.e., assessing unpleasant conditions as challenging rather than threatening) and interpersonal forgiveness were predictors of greater emotion regulation.55 Second, greater agency (i.e., a positive focus on the self, greater confidence) significantly predicted reduced negative affect and greater positive affect, while a lack of agency predicted reduced positive affect among individuals with IBS.47 Third, perceived self-efficacy and resilience were both positively correlated with task-oriented coping, and both negatively correlated with emotion-oriented coping.35 Fourth, self-esteem and self-efficacy were positively correlated with each other.42 And lastly, greater self-compassion was predicted by greater mindfulness.56

Key maladaptive or negative psychological factors examined in relationship to PP constructs included depression, anxiety, somatization, and psychological distress. Greater resilience,57 positive illness cognition,57 positive affect,51 optimistic coping,52 self-esteem,42 and self-efficacy,42 were each associated with fewer depressive symptoms. Greater positive affect,51 optimistic coping,52 self-esteem,42 and self-efficacy42 each negatively correlated with anxiety, in addition to depression. Positive affect was further found to partially mediate the relationship between both negative beliefs about emotions and impoverished emotional experience (i.e., alexithymia) and IBS interference (i.e., the extent to which IBS interferes with life roles).51 Self-esteem and self-efficacy also negatively correlated with somatization, in addition to depression and anxiety.42 Conversely, lower levels of psychological coping58 correlated with more severe somatization and greater depression, overall anxiety, and GI-specific anxiety,58 and greater use of avoidant and suppressive coping strategies was similarly associated with more depressive symptoms and reduced positive affect.59 Further, greater self-compassion was found to predict less psychological distress.56 In contrast, one study did not find any significant relationships between optimism (when measured with a single item question) and depressive symptoms or psychological distress.57

Health-related quality of life.

Five studies identified relationships between PP constructs and HRQoL among individuals with IBS. First, lower resilience (as measured by the BRS) was associated with worse HRQoL (as measured by the IBS-Quality of Life (QOL)60 survey).33 Second, self-esteem was positively correlated with physical quality of life (as measured by the Short-Form-12 (SF-12)61), but not mental quality of life.42 Third, self-efficacy was positively correlated with both physical and mental quality of life (as measured by the SF-12)42 and improved global HRQoL (as measured by the IBS-QOL).54 Fourth, positive affect was found to negatively correlate with the degree of IBS interference on life roles and the ability to work or function (as measured by The Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS)).51 Lastly, a greater sense of coherence was significantly associated with improved HRQoL (as measured by the IBS-QOL) in bivariate analyses, but only the emotional functioning and mental health dimensions of the IBS-QOL remained significant in a linear regression accounting for gender, average stool frequency, GI symptom severity, psychological distress, GI-specific anxiety, somatic symptom severity, and rectal pain threshold.62

3.3.3. Biological mechanisms

Three studies investigated potential biological mechanisms underlying relationships between PP constructs and IBS. Park and colleagues (2018) identified a significant interaction between BRS-measured resilience and IBS status for adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-stimulated cortisol response, such that less resilient controls had a lower cortisol response to ACTH stimulation, while less resilient participants with IBS had an enhanced cortisol response.33 Eriksson and colleagues (2008) found that patients with IBS-Diarrhea (IBS-D) had significantly higher C-peptide values compared to healthy controls, as well as a greater sense of coherence compared to patients with IBS-Constipation (IBS-C) and IBS-Alternating (IBS-A). Patients with IBS-C had significantly higher prolactin levels than both healthy controls and patients with IBS-D. All three subtypes (IBS-D, IBS-C, and IBS-Mixed) had significantly higher triglycerides than healthy controls. No significant differences, however, were identified between individuals with IBS and healthy controls in morning or afternoon cortisol levels.63 Lastly, Bhatt and colleagues (2022) found that patients whose IBS symptoms did not improve at three months had higher scores on the CD-RISC persistence subscale (a measure of resilience), which was associated with lower anatomical connectivity within the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, as well as greater resting-state functional connectivity in circuits related to sustained attention. They postulated this might reflect a tendency toward increased perseveration on painful stimuli. They also found that patients whose IBS symptoms improved after three months had greater scores on the CD-RISC adaptability subscale, which was associated with greater default mode resting-state connectivity and corticospinal tract integrity. They postulated this latter finding might reflect improved pain-relieving modulatory mechanisms. Bhatt and colleagues (2022) note in their limitations, however, that they did not include a control group of healthy volunteers, other GI conditions (e.g., IBD), or other chronic pain conditions, which might have provided additional insight into whether these findings are unique to IBS.50

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review investigating PPWB in individuals with IBS. This review identified key differences in PP constructs among individuals with IBS compared to healthy populations; namely, individuals with IBS have lower levels of resilience, self-efficacy, well-being, and positive affect, and greater difficulty with emotion regulation. Furthermore, among individuals with IBS, greater PPWB (as measured by specific PP constructs) correlates with improved physical health, mental health, and HRQoL. Currently, limited research has been conducted to examine potential biological mechanisms that might explain or underlie these observed relationships.

These findings extend the existing literature of what is known about PPWB in healthy populations and other chronic medical conditions.13-16 As previously noted, in both healthy individuals and those suffering from other chronic medical conditions, PP constructs have been linked to many different aspects of improved health, including reduced pain and fewer physical symptoms.13-16 We similarly found that greater resilience, positive affect, optimistic coping, and improved emotional well-being may be associated with reduced severity of IBS symptoms, and greater self-efficacy may be associated with less interference from pain in IBS individuals.

The findings of this systematic review also highlight, however, areas in need of further investigation. Optimism, for example, is the PP construct that has been most strongly associated with improved health outcomes across different populations,64,65 yet very limited examination of optimism has been conducted in the IBS population. This systematic review, for example, identified only one study that examined optimism directly (using a single item yes/no question),57 and two studies that examined optimistic coping;52,58 no studies utilized standard measures of optimism such as the Life Orientation Test.66 Similarly, few studies in this systematic review adjusted for negative psychological constructs (e.g., catastrophizing) or psychiatric conditions (e.g., depression) when examining the impact of PP constructs on outcomes of interest (e.g., physical health, mental health, HRQoL); further investigation in this area is needed to help disentangle the relative effects of positive versus negative psychological constructs on these outcomes. Additionally, most studies in this review compared PP constructs between individuals with IBS and healthy controls; greater comparison of PP constructs between individuals with IBS and other chronic medical conditions could provide improved insight into the IBS experience. Furthermore, potential underlying mechanisms such as inflammation, autonomic dysfunction, and health behavior change, among others, have been examined in other populations,64 yet very little research to date (only three studies per this systematic review) has investigated either behavioral or biological pathways that might underlie the observed relationships between PPWB and IBS. Lastly, while there is a strong prospective literature around PPWB and physical health in other chronic conditions (e.g., heart disease),18,67 this does not appear to exist yet for IBS.

Collectively, the findings of this systematic review, combined with the demonstrated prospective relationships between PP constructs and health outcomes in other populations, suggest that PP constructs have the potential to be a clinically important target in IBS. There are existing brain-gut behavior therapies (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy) for DGBI that effectively target some of the maladaptive psychological factors that contribute to IBS symptomatology.11 Though highly effective, implementation of these brain-gut behavior therapies is limited by issues of scalability (i.e., these therapies typically require behavioral health providers with specialized training)68 and acceptability (e.g., many patients with IBS resist participation in interventions focused on psychopathology, due to stigma or perceived lack of relevance to their symptoms).26,69 Additionally, existing brain-gut behavior therapies may not adequately target the aspects of PPWB (e.g., resilience, positive affect) which are linked to improved physical health, mental health, and HRQoL.26 Comprised of simple, easy-to-perform exercises to boost PP constructs, PP interventions have the potential to address limitations of other brain-gut behavior therapies in that their administration does not require specialized training,26,70 and they are typically well-accepted and perceived as non-stigmatizing.26,70 Though leaders in the field of psychogastroenterology have suggested that there may be a role for PP interventions to be integrated early into the clinical care of IBS,24,26 the use of PP interventions in individuals with IBS remains to be studied. If the early introduction of PP interventions, perhaps even by the treating gastroenterologist as part of routine care, were found to be effective for individuals with IBS, the hope is that other brain-gut behavior therapies (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy), which require specialized providers, could then be reserved for more complex or severe cases in a stepped-care approach.26 The use of PP interventions in IBS represents an area of much needed future investigation.

Potential limitations to this systematic review should be noted. First, different instruments were used to assess IBS; the vast majority (n=16), however, used a version of the Rome criteria.2 Second, different PP constructs and associated measures, measurement parameters, and methods limit the comparability of results across studies. Third, despite the rigorousness of the approach to this systematic review (i.e., PRISMA-compliant, registered in PROSPERO, following the SWiM guideline31), a meta-analysis could not be completed due to the heterogeneity of studies and limited number of studies in each category. Lastly, it should be noted that this systematic review examined primarily cross-sectional studies, which limits the ability to determine directionality of the described relationships.

In summary, PPWB represents an important future area of investigation in IBS. PP constructs are lower among individuals with IBS compared to healthy populations, and greater PPWB is associated with improved physical health, mental health, and HRQoL. Future studies are needed to evaluate the directionality of these relationships using longitudinal study design, and to evaluate whether PP interventions might be effective in building PPWB and improving health outcomes in the complex and high-comorbidity IBS population.

Funding:

Time for analysis and article preparation was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, K23DK120945 (KS), K23DK131334 (HBM), R01DK121003 (BK), and U01DK112193 (BK), and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, R01HL155301 (CMC), R01HL133149 (JCH), K23HL135277 (RAM), and K23HL148017 (EHF), National Cancer Institute, K08CA251654 (HLA), the Harvard Medical School Dupont Warren Research Fellowship (ENM), and the German Heart Foundation (MS). The study sponsors had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data or writing of the report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests: There are no conflicts of interest to declare related to this research. KS has received research support from Ironwood and Urovant and has served as a consultant to Anji, Arena, Gelesis, GI Supply, Sanofi, and Shire/Takeda. HBM receives royalties from Oxford University Press for her forthcoming book on rumination syndrome. CMC has received salary support for research from BioXcel Pharmaceuticals and honoraria for talks to Sunovion Pharmaceuticals on topics unrelated to this research. BK has received research support from Medtronic, Gelesis, Takeda, Vanda, and consulting/speaking arrangements with Arena, CinDom, Cin Rx, Medtronic, Entrega, Ironwood, Neurogastrix, Phathom, Serepta, Sigma Wasserman, and Takeda. LK receives consulting fees from Lilly, Takeda, Pfizer, Abbvie, Reckitt Health and Trellus Health, and is a co-founder/equity owner for Trellus Health. There are no other funding sources to declare.

Registration: Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews CRD42022304767.

References

- 1.Enck P, Aziz Q, Barbara G, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Oudenhove L, Crowell MD, Drossman DA, et al. Biopsychosocial Aspects of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Gastroenterology 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zia JK, Lenhart A, Yang PL, et al. Risk Factors for Abdominal Pain Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction in Adults and Children: A Systematic Review. Gastroenterology 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanchard EB, Scharff L. Psychosocial aspects of assessment and treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in adults and recurrent abdominal pain in children. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002;70:725–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Person H, Keefer L. Psychological comorbidity in gastrointestinal diseases: Update on the braingut-microbiome axis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2021;107:110209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sibelli A, Chalder T, Everitt H, Workman P, Windgassen S, Moss-Morris R. A systematic review with meta-analysis of the role of anxiety and depression in irritable bowel syndrome onset. Psychol Med 2016;46:3065–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eijsbouts C, Zheng T, Kennedy NA, et al. Genome-wide analysis of 53,400 people with irritable bowel syndrome highlights shared genetic pathways with mood and anxiety disorders. Nat Genet 2021;53:1543–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu JC. Psychological Co-morbidity in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Epidemiology, Mechanisms and Management. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012; 18:13–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elsenbruch S, Rosenberger C, Enck P, Forsting M, Schedlowski M, Gizewski ER. Affective disturbances modulate the neural processing of visceral pain stimuli in irritable bowel syndrome: an fMRI study. Gut 2010;59:489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keefer L, Ballou SK, Drossman DA, Ringstrom G, Elsenbruch S, Ljotsson B. A Rome Working Team Report on Brain-Gut Behavior Therapies for Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology 2022;162:300–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubzansky LD, Huffman JC, Boehm JK, et al. Positive Psychological Well-Being and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1382–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finan PH, Garland EL. The role of positive affect in pain and its treatment. Clin J Pain 2015;31:177–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen HN, Scheier MF, Greenhouse JB. Optimism and physical health: a meta-analytic review. Ann Behav Med 2009;37:239–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlson ME, Wells MT, Peterson JC, et al. Mediators and moderators of behavior change in patients with chronic cardiopulmonary disease: the impact of positive affect and self-affirmation. Transl Behav Med 2014;4:7–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: a quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosom Med 2008;70:741–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakhssi F, Kraiss JT, Sommers-Spijkerman M, Bohlmeijer ET. The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in clinical samples with psychiatric or somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2018;18:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DuBois CM, Lopez OV, Beale EE, Healy BC, Boehm JK, Huffman JC. Relationships between positive psychological constructs and health outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. Int J Cardiol 2015;195:265–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tindle HA, Chang YF, Kuller LH, et al. Optimism, cynical hostility, and incident coronary heart disease and mortality in the Women’s Health Initiative. Circulation 2009;120:656–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ, Riper H, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E. Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health 2013; 13:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huffman JC, Feig EH, Millstein RA, et al. Usefulness of a Positive Psychology-Motivational Interviewing Intervention to Promote Positive Affect and Physical Activity After an Acute Coronary Syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2019;123:1906–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huffman JC, Golden J, Massey CN, et al. A Positive Psychology-Motivational Interviewing Intervention to Promote Positive Affect and Physical Activity in Type 2 Diabetes: The BEHOLD-8 Controlled Clinical Trial. Psychosom Med 2020;82:641–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller R, Gertz KJ, Molton IR, et al. Effects of a Tailored Positive Psychology Intervention on Well-Being and Pain in Individuals With Chronic Pain and a Physical Disability: A Feasibility Trial. Clin J Pain 2016;32:32–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keefer L. Behavioural medicine and gastrointestinal disorders: the promise of positive psychology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;15:378–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Tilburg MAL, Drossman DA, Knowles SR. Psychogastroenterology: The brain-gut axis and its psychological applications. J Psychosom Res 2021;152:110684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feingold J, Murray HB, Keefer L. Recent Advances in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Digestive Disorders and the Role of Applied Positive Psychology Across the Spectrum of GI Care. J Clin Gastroenterol 2019;53:477–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bramer WM, Rethlefsen ML, Kleijnen J, Franco OH. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Syst Rev 2017;6:245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies - NHLBI, NIH [homepage on the Internet] [cited 6.3.22].

- 30.Maass SW, Roorda C, Berendsen AJ, Verhaak PF, de Bock GH. The prevalence of long-term symptoms of depression and anxiety after breast cancer treatment: A systematic review. Maturitas 2015;82:100–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ 2020;368:16890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim YS, Kim N. Sex-Gender Differences in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018;24:544–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park SH, Naliboff BD, Shih W, et al. Resilience is decreased in irritable bowel syndrome and associated with symptoms and cortisol response. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018;30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shahdadi H, Balouchi A, Shaykh A. Comparison of Resilience and Psychological Wellbeing in Women with Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Normal Women. Mater Sociomed 2017;29:105–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dabek-Drobny A, Mach T, Zwolinska-Wcislo M. Effect of selected personality traits and stress on symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Folia Med Cracov 2020;60:29–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker CH, Naliboff BD, Shih W, et al. The Role of Resilience in Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Other Chronic Gastrointestinal Conditions, and the General Population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:2541–50 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zarpour S, Besharat MA Comparison of personality characteristics of individuals with irritable bowel syndrome and healthy individuals. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2011;30:84–8. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety 2003;18:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med 2008;15:194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagnild GM, Young HM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. J Nurs Meas 1993;1:165–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Endo Y, Shoji T, Fukudo S, et al. The features of adolescent irritable bowel syndrome in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;26 Suppl 3:106–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taft TH, Keefer L, Artz C, Bratten J, Jones MP. Perceptions of illness stigma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Qual Life Res 2011;20:1391–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luszczynska A, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. The general self-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. J Psychol 2005;139:439–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farhadi A, Banton D, Keefer L. Connecting Our Gut Feeling and How Our Gut Feels: The Role of Well-being Attributes in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018;24:289–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quek SXZ, Loo EXL, Demutska A, et al. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;36:2187–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54:1063–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voci SC, Cramer KM. Gender-related traits, quality of life, and psychological adjustment among women with irritable bowel syndrome. Qual Life Res 2009;18:1169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gratz KL RL. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selvi K BO. Group comparison of individuals with and without irritable bowel syndrome in terms of psychological and lifestyle-related factors. Dusunen Adam The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 2022;1:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhatt RR, Gupta A, Labus JS, et al. A neuropsychosocial signature predicts longitudinal symptom changes in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Psychiatry 2022;27:1774–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sibelli A, Chalder T, Everitt H, Chilcot J, Moss-Morris R. Positive and negative affect mediate the bidirectional relationship between emotional processing and symptom severity and impact in irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res 2018;105:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Torkzadeh F, Danesh M, Mirbagher L, Daghaghzadeh H, Emami MH. Relations between Coping Skills, Symptom Severity, Psychological Symptoms, and Quality of Life in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Int J Prev Med 2019;10:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, Schein J, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Validity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. Clin J Pain 2004;20:309–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen J, Barandouzi ZA, Lee J, et al. Psychosocial and Sensory Factors Contribute to Self-Reported Pain and Quality of Life in Young Adults with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Pain Manag Nurs 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mazaheri M, Nikneshan S, Daghaghzadeh H, Afshar H. The Role of Positive Personality Traits in Emotion Regulation of Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). Iran J Public Health 2015;44:561–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Potter GK HP, Morrison TG. Dispositional Mindfulness in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: the Mediating Role of Symptom Interference and Self-Compassion. Mindfulness 2020;11:462–71. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ben-Ezra M, Hamama-Raz Y, Palgi S, Palgi Y. Cognitive appraisal and psychological distress among patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 2015;52:54–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilpart K, Tornblom H, Svedlund J, Tack JF, Simren M, Van Oudenhove L. Coping Skills Are Associated With Gastrointestinal Symptom Severity and Somatization in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:1565–71 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sugawara N, Sato K, Takahashi I, et al. Depressive Symptoms and Coping Behaviors among Individuals with Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Japan. Intern Med 2017;56:493–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Patrick DL, Drossman DA, Frederick IO, DiCesare J, Puder KL. Quality of life in persons with irritable bowel syndrome: development and validation of a new measure. Dig Dis Sci 1998;43:400–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ware J Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Melchior C, Colomier E, Trindade IA, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: Factors of importance for disease-specific quality of life. United European Gastroenterol J 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eriksson EM, Andren KI, Eriksson HT, Kurlberg GK. Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes differ in body awareness, psychological symptoms and biochemical stress markers. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:4889–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scheier MF, Carver CS. Dispositional optimism and physical health: A long look back, a quick look forward. Am Psychol 2018;73:1082–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huffman JC. Optimism and Health: Where Do We Go From Here? JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1912211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol 1994;67:1063–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rozanski A, Bavishi C, Kubzansky LD, Cohen R. Association of Optimism With Cardiovascular Events and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1912200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kazdin AE. Addressing the treatment gap: A key challenge for extending evidence-based psychosocial interventions. Behav Res Ther 2017;88:7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hutton JM. Issues to consider in cognitive-behavioural therapy for irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;20:249–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huffman JC, Millstein RA, Mastromauro CA, et al. A Positive Psychology Intervention for Patients with an Acute Coronary Syndrome: Treatment Development and Proof-of-Concept Trial. J Happiness Stud 2016;17:1985–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]