Abstract

Insulators define chromosomal domains such that an enhancer in one domain cannot activate a promoter in a different domain. We show that the Drosophila gypsy insulator behaves as a cis-stimulatory element in the larval fat body. Transcriptional stimulation by the insulator is distance dependent, as expected for a promoter element as opposed to an enhancer. Stimulation of a test alcohol dehydrogenase promoter requires a binding site for a GATA transcription factor, suggesting that the insulator may be facilitating access of this DNA binding protein to the promoter. Short-range stimulation requires both the Suppressor of Hairy-wing protein and the Mod(mdg4)-62.7 protein encoded by the trithorax group gene mod(mdg4). In the absence of interaction with Mod(mdg4)-62.7, the insulator is converted into a short-range transcriptional repressor but retains some cis-stimulatory activity over longer distances. These results indicate that insulator and promoter sequences share important characteristics and are not entirely distinct. We propose that the gypsy insulator can function as a promoter element and may be analogous to promoter-proximal regulatory modules that integrate input from multiple distal enhancer sequences.

The normal expression of eukaryotic genes requires stimulation of promoters by enhancers that often exert their effects over many kilobases of intervening DNA (3, 54). Given this ability of enhancers to function over long distances, there must be mechanisms that prevent enhancers of one gene from activating transcription of neighboring genes. Current models propose that this is accomplished by insulators, DNA sequences that define chromosomal domains such that a promoter in one domain cannot be activated by an enhancer in a different domain (23, 26). For example, the scs and scs′ sequences that flank the Drosophila hsp70 gene prevent transcriptional stimulation by the yolk protein-1 enhancer when inserted between the enhancer and an hsp 70 target promoter (32, 56). Consistently, these same sequences insulate transgenes from the chromosomal position effects characteristic of germ line transformation in Drosophila (33). Such insulators are likely to have important roles in the correct developmental regulation of many genes as exemplified by Fab-7, which separates the iab-6 and iab-7 regulatory elements of the Drosophila Bithorax complex, and the locus control region located upstream of the chicken β-globin locus (9, 28, 38).

One of the most extensively studied insulators is located in the 5′ nontranslated region of the Drosophila gypsy retrotransposon. Many of the spontaneous mutations caused by gypsy elements are due to the blocking of enhancer-promoter interactions attributable to this insulator (11, 17, 24, 25, 40). A 430-bp fragment of gypsy, termed “the gypsy insulator,” placed between an enhancer and its target promoter is sufficient to block enhancer stimulation (11, 17, 24, 45, 51, 60). As is true of other insulators, this same DNA fragment effectively insulates transgenes from chromosomal position effects (48).

The Suppressor of Hairy-wing protein [Su(Hw)] is required for this enhancer-blocking activity in vivo (40). The insulator relieves transcriptional repression mediated by polycomb group proteins, and Su(Hw) is required for this activity as well (35). Su(Hw) contains 12 zinc fingers that mediate direct binding to an octanucleotide sequence repeated 12 times in the gypsy insulator (34, 44, 50, 53). It also contains three conserved motifs that are implicated in protein-protein interactions and that contribute to blocking of distal enhancers (15, 16, 27, 29, 34).

Another gene, mod(mdg4), is also involved in the enhancer-blocking activity of the gypsy insulator. Specifically, in the presence of a mutant form of this gene [the mod(mdg4)ulallele], the insulator influences expression of nearby genes in a more general manner (7, 18, 19, 22). Disruption of the carboxy-terminal domain of Mod(mdg4)-67.2, which mediates binding to Su(Hw), apparently accounts for the diverse effects seen (15, 17, 21, 22, 27). In some cases, the insulator appears to lose its polar enhancer-blocking activity, with promoter-proximal as well as promoter-distal enhancers apparently being repressed, sometimes in a variegated pattern (18, 21, 22). In other cases, enhancer blocking by the insulator appears to be either unaffected or completely abolished in the presence of mod(mdg4)ul (6, 7, 15, 18, 27). The mod(mdg4) gene is identical to E(var)3-93D, which influences position effect variegation and whose wild-type function likely involves establishment and/or maintenance of a transcriptionally active chromatin conformation (10).

In spite of recent evidence suggesting that insulators physically interact with one another (8, 41), the biochemical mechanisms underlying insulator activity remain poorly understood. In particular, it is not clear why the promoter region of gypsy contains an insulator sequence. One possibility is that the insulator is in fact a promoter sequence that plays a direct role in transcription.

Here we critically test this hypothesis using both transient and germ line transformation methods. In the absence of an enhancer, the insulator stimulates transcription of a minimal alcohol dehydrogenase gene (Adh) promoter in a distance-dependent manner. Su(Hw) is essential for this stimulation. Mod(mdg4)-67.2 is necessary for short-range transcriptional stimulation, but lower levels of longer-range stimulation are seen without the binding of Mod(mdg4)-67.2 to the insulator. In fact, in the absence of Mod(mdg4)-67.2 binding, the insulator is converted into a short-range transcriptional repressor. We also demonstrate that transcriptional stimulation by the gypsy insulator is promoter specific. We provide evidence that this stimulation is analogous to that mediated by the GAGA factor in that it may reflect facilitated binding of a limiting transcription factor to the adjacent promoter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reporter gene construction.

Full details of all gene constructions are available upon request. Briefly, the firefly luciferase gene carried in the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega) was used as a reporter for all experimental constructs. This was fused to one of three promoters. The minimal promoter of the Drosophila affinidisjuncta Adh gene consisted of sequences between the NdeI site at position −203 and the EcoRI site at position +18 (31, 36). To assess the contribution of box A binding factor (ABF) binding, a promoter carrying a clustered point mutation removing the GATA binding site, termed MutB (31), was inserted into pGL3-Basic using the same strategy. Constructions with the white promoter carried the so-called mini-white promoter from pCaSpeR (46). Sequences from −316 to +60 were excised and inserted upstream of the firefly luciferase coding region of pGL3-Basic.

The gypsy insulator was obtained from pREP-1 (kindly provided by P. Geyer) by digestion with XmnI and BstXI and inserted into the multiple cloning site of pUC18 (42). The insulator was removed from the resulting construction by digestion with various restriction enzymes for insertion into the appropriate reporter constructions. Spacer DNAs were obtained from bacteriophage λDNA. The pCaSpeR vector was used for P element transformation (46). For all experiments shown, the orientation of the insulator was held constant. Plasmids used for injection were purified by CsCl gradient centrifugation and quantified by fluorimetry with Hoechst 33258 dye using a Hoefer DNA Quant fluorometer.

Drosophila stocks.

For transient transformation in the presence of wild-type su(Hw) and mod(mdg4) genes, the Drosophila melanogaster Adh-null stock (Adhfn6 cn; ry506) was used (60). To study the role of the Su(Hw) protein in insulator function, the y1 w1118 ct6 f1; Adhfn6 cn; su(Hw)v/su(Hw)f stock was used (60). To assess the role of mod(mdg4), the y1 w1118 ct6 f1; mod(mdg4)u1 stock was used. The ct6 and f1 alleles carry gypsy-induced mutations that allow visual verification of the su(Hw) and mod(mdg4) genotypes. For P element transformation, the w1118 strain was used, and homozygous transformed lines were produced as described previously (60).

Transformation.

Transient transformation was performed by injection of plasmid DNAs into the ventral midline of preblastoderm embryos for optimal expression in the larval fat body as described in detail elsewhere (36, 37, 60). Equimolar mixtures of an experimental plasmid encoding firefly luciferase and a control plasmid were injected. The firefly luciferase assay is extremely sensitive and is linear over at least 4 orders of magnitude. Typical basal expression for the wild-type Adh promoter ranged from 106 to 107 light units per larva per 10-s reading with a luminometer. For Adh-null stocks, the control plasmid was p11BXB2, which carries the full-length Adh gene from D. affinidisjuncta and encodes alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) (4). Measurement of firefly luciferase and ADH activities was done as described previously (60). For the analysis of mod(mdg4) effects, which required the use of a strain that was not Adh null, pWWRL1 served as an internal control. This was constructed from pRL-null (Promega), which encodes Renilla reniformis luciferase, by the insertion of the minimal promoter of the D. affinidisjuncta Adh gene as described above. In this case, the Dual Luciferase assay (Promega) was used to measure expression. In all cases, five independent groups of five larvae were analyzed for each gene.

Others have shown that supercoiled plasmids injected in this manner remain as supercoiled monomers, without detectable rearrangement or recombination until the third larval instar (49). Southern analysis confirmed that all plasmids used in the present study remained as supercoiled monomers until the third larval instar, with no detectable conversion to nicked circular forms or integration into the chromosome. However, larger plasmids did show decreased survival to the third instar. To control for this, expression levels for all experimental plasmids carrying the gypsy insulator were normalized relative to similarly sized control plasmids lacking insulator sequences.

P element transformation was performed as described previously (60). Six to seven transformed lines were analyzed for each gene. Only homozygous viable autosomal insertions were evaluated. For both transient and stably transformed stocks, levels of expression were compared statistically by the Student t test, corrected, if necessary, for unequal sample sizes (62).

DNA sequence analysis.

Genomic DNAs were purified from Oregon-R and mod(mdg4)ul flies as described previously (5). The mod(mdg4) genomic regions were amplified with Accutaq LA DNA polymerase (Sigma), using the conditions suggested by the manufacturer. Primers were designed according to published cDNA sequences (GenBank primary accession numbers U30905, U30913, and U30914). Sequencing was performed on an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer using ABI PRISM BigDye terminator cycle sequencing. Both strands were sequenced throughout.

RESULTS

The insulator influences basal transcription in a manner that depends on distance to the promoter.

Previous studies have ascribed both transcriptional stimulation and repression activities to the gypsy insulator (30, 52). However, no study has critically addressed the possibility that stimulation and repression activities may depend upon the spacing between the insulator and the promoter. To address the effects of the insulator on basal transcription, we constructed reporter genes with 20-bp to 4.9-kb spacing between the insulator and a test promoter, a minimal Adh promoter, in the absence of an enhancer and analyzed these by transient transformation of larval fat body (36, 60).

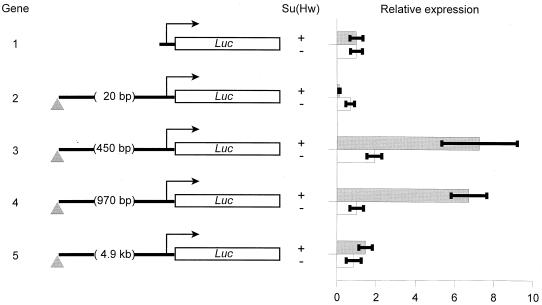

As shown in Fig. 1, the smallest spacing between the insulator and the promoter results in transcriptional repression that is mediated by Su(Hw). In a wild-type su(Hw) background, basal expression is decreased about fivefold (Fig. 1, gene 2) (P = 0.0004). However, in a strain containing low levels of Su(Hw) activity, there is no significant repression (Fig. 1, gene 2).

FIG. 1.

The gypsy insulator affects basal transcription in a distance-dependent manner. Gene 1 has the firefly luciferase reporter of the pGL3-basic vector (Luc) under the control of the minimal promoter (−203 to +18) of the D. affinidisjuncta Adh gene (arrow). Spacing between the −203 position of the minimal promoter and the point of insertion for the gypsy insulator (represented by a triangle) is shown for each gene. Gene 2 carries multiple cloning site sequences only, and other genes carry fragments of bacteriophage λ DNA ranging in size from 450 bp to 4.9 kb. Transient transformation and measurement of enzyme activities were performed as described previously by injecting plasmid mixtures containing experimental plasmids and an ADH-encoding control plasmid into the ventral midline of embryos (60). The bars represent ratios of luciferase activity to ADH activity, normalized relative to those obtained for similarly sized control plasmids (lacking the insulator) in the same genetic background. Gray bars, wild-type Su(Hw) larvae (+); open bars, su(Hw)− larvae (−). Means ± standard deviations for five independent samples are shown.

In contrast, increasing the spacing between the promoter and the insulator revealed distance-dependent transcriptional stimulation by the insulator. Significantly, increasing the spacing to 450 bp, which is equivalent to the spacing between the insulator and the transcriptional initiation site in the gypsy element, resulted in a sevenfold stimulation of expression that requires wild-type levels of Su(Hw) protein (Fig. 1, gene 3) (P = 0.00007). Similarly, a spacing of 970 bp resulted in a comparable level of Su(Hw)-dependent stimulation (Fig. 1, gene 4) (P = 0.0005). However, effects on basal transcription are abolished with a spacing of 4.9 kb (Fig. 1, gene 5). Thus, it appears that a spacing of about 5 kb is sufficient to eliminate the positive effect of the insulator on reporter gene expression.

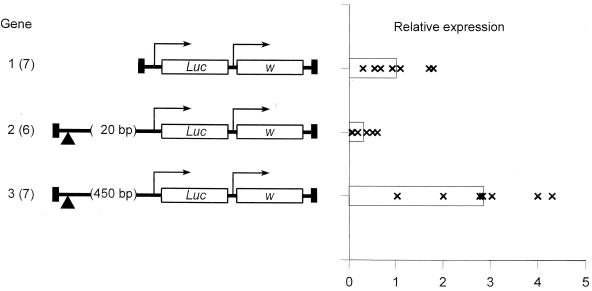

Transient transformation is faster than germ line transformation and avoids chromosomal position effects that might arise from interactions with unknown promoters, enhancers, or insulators in the chromosome. Also, functions of regulatory sequences defined by this method have been repeatedly confirmed by germ line transformation (31, 36, 37, 60). Nonetheless, since the gypsy insulator may be involved in higher-order chromatin structures requiring interaction with distant insulators in the chromosome (20), it might represent a special case. To test this, genes showing repression and stimulation were introduced into the chromosome by P element transformation. As the results in Fig. 2 confirm, though the magnitude of the response is dampened by typical chromosomal position effects, the insulator, in fact, either represses or stimulates basal transcription in a spacing-dependent manner when assayed in a chromosomal context. Expression of gene 2 is significantly lower than that of gene 1 (P = 0.006), and that of gene 3 is significantly higher than that of both gene 1 (P = 0.002) and gene 2 (P = 0.0003).

FIG. 2.

The insulator influences basal transcription in the chromosome. Gene structures are displayed as shown in Fig. 1. w, the white gene on the pCaSpeR-4 vector; vertical black rectangles, P element sequences. Each data point represents the mean result for three independent samples consisting of five third-instar larvae from a given transformed line, normalized to the mean value for gene 1. The number of transformed lines is given in parentheses following the gene name. Bars show the grand means for all transformed lines for a given gene. Previous results show that the insulator has no effect in the chromosome with a spacing of 4.9 kb (60).

Effects on basal transcription are promoter specific.

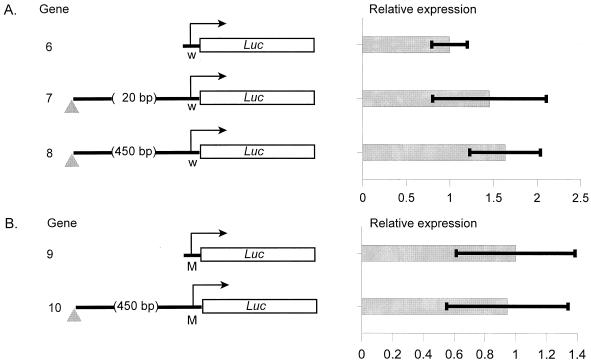

The question then arises as to why such effects on basal transcription have not been generally observed by others. One possibility is that stage-specific differences in trans-acting factors may account for this. While we have analyzed expression in a larval tissue, others have examined embryonic or adult tissues (8, 41, 45). Alternatively, effects on basal transcription may be promoter specific. Many previous studies have used the promoter from the white gene. Therefore, to test for promoter-specific effects, we performed transient transformation of the larval fat body using this promoter. The white promoter is neither repressed nor significantly stimulated with either minimal spacing or 450-bp spacing between it and the insulator (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Effects on basal transcription are promoter specific. (A) Genes driven by the white promoter are not significantly stimulated or repressed by the gypsy insulator (P > 0.1, in both cases). W, the white promoter. (B) Removal of the GATA site from the Adh promoter abolishes stimulation by the gypsy insulator. The MutB promoter (M) carries a clustered point mutation that retains the spacing between the insulator and the transcriptional start site. Transient transformation and data presentation are as for Fig. 1, with values normalized to that obtained for the corresponding gene lacking the insulator.

The white promoter is only 1% as active in the larval fat body as the Adh promoter. This is hardly surprising, given that it lacks both a TATA box in the −25 region and a binding site for the GATA transcription factor ABF, or Serpent, which is essential for high-level expression of the Adh promoter in the larval fat body in vivo and as measured directly by in vitro transcription in embryonic nuclear extracts (31). ABF binds directly to this sequence, as demonstrated by electrophoretic gel mobility shift and DNase footprinting assays, but fails to bind a mutant form of the Adh promoter (MutB) lacking this sequence (31). The fact that the insulator can reverse repression by polycomb group proteins (35, 57) suggested to us that the stimulation seen for the Adh promoter might reflect the ability of the insulator to facilitate access of ABF to the DNA template. If so, removing the ABF binding site from the Adh promoter should eliminate the stimulatory effect of the insulator. Removal of the ABF binding site located 73 bp upstream of the transcription initiation point lowers expression of the Adh promoter 50-fold to levels comparable to those seen for the white promoter (data not shown). Significantly, with this modified promoter, stimulation by the insulator is completely abolished (Fig. 3B).

Mod(mdg4)-67.2 is required for stimulation of basal transcription.

It is unlikely that Su(Hw) alone accounts for these effects. Others have provided evidence for physical interaction between the Mod(mdg4)-67.2 protein and Su(Hw) (6, 15, 22, 27). The mod(mdg4) gene is a member of the trithorax group of genes whose normal function is to mediate local opening of chromatin structure, thereby facilitating transcription (10, 21). The mod(mdg4)u1 allele, which encodes a truncated Mod(mdg4)-67.2 protein (6, 22), is known to influence enhancer blocking by the insulator (15). Our analysis of genomic DNA from wild-type and mod(mdg4)u1 flies showed that the mod(mdg4)u1 allele encodes a Mod(mdg4)-67.2 protein that is shortened by a total of 144 amino acids (GenBank accession numbers AF214648 and AF214650, respectively). This mutation removes all but eight of the amino acids of the carboxy-terminal exon and abolishes the interaction of Mod(mdg4)-67.2 with Su(Hw) (15, 27). If enhancer blocking and transcriptional stimulation are mechanistically related, we reasoned that this mutation would have a direct impact on the insulator's transcriptional stimulation activity.

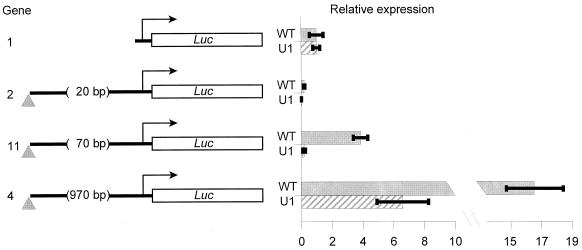

Indeed, the mod(mdg4)u1 allele dramatically alters the insulator's effects on basal transcription (Fig. 4). With minimal spacing between the promoter and the insulator (Fig. 4, gene 2), transcriptional repression is greater in the mod(mdg4)u1 background (12-fold) than in the wild type (5-fold). Increasing the spacing by just 50 bp reveals a clear distinction between the activity of the insulator in the wild-type and mod(mdg4)u1 backgrounds; there is a fourfold stimulation in wild-type larvae in contrast to a sixfold repression in mod(mdg4)u1 larvae (Fig. 4, gene 11). However, the mod(mdg4)u1 mutation does not abolish all stimulatory activity of the insulator. When the distance between the insulator and the promoter is increased to 970 bp, the insulator still stimulates transcription, but about threefold less strongly than it does in the wild type (Fig. 4, gene 4). Therefore, the Mod(mdg4)-67.2 protein is required for short-range transcriptional stimulation but is not absolutely essential for stimulation over longer distances. Moreover, in the absence of Mod(mdg4)-67.2 binding, Su(Hw) apparently actively represses basal transcription over short distances. A comparison of genes 2 and 11 in Fig. 4 demonstrates that this direct repression is distinct from the presumably nonspecific steric interference with the binding of limiting transcription factors, such as ABF, that results from the closest spacing.

FIG. 4.

Mod(mdg4)-67.2 influences basal transcription. Aliquots of the same plasmid mixtures were injected into either a stock carrying a wild-type mod(mdg4) gene (WT) or a homozygous mod(mdg4)u1 stock (U1). A plasmid encoding R. reniformis luciferase, pWWRL1, served as an internal control, and the Dual Luciferase assay (Promega) was used to measure expression. With this method, stimulation of transcription by the insulator is about twice as high as that seen using a full-length Adh gene as an internal control. Bars represent ratios of firefly luciferase to Renilla luciferase normalized to the value for the corresponding gene, lacking the insulator, in the same genetic background (mean ± standard deviation).

DISCUSSION

The distance-dependent transcriptional stimulation displayed by the gypsy insulator is what one would expect for a promoter element as opposed to an enhancer that would stimulate transcription in a distance-independent manner. These results also suggest that differences in spacing between promoter and insulator sequences account for the apparently contradictory results of others. With a spacing of several hundred base pairs between the insulator and the transcriptional start site, as found in the native gypsy element, Su(Hw) stimulates transcription (52). Yet with minimal spacing, as used previously between heat shock response elements and the Su(Hw) binding sites, Su(Hw) inhibits heat shock-induced stimulation (30). In the latter case, Su(Hw), which remains bound to the insulator during heat shock (20), presumably interferes sterically with the binding of the heat shock transcription factor.

Insulator-promoter interactions are quite sensitive to spacing. In the wild-type genetic background, a change in spacing of as little as 50 bp makes a 20-fold difference in expression (fourfold stimulation versus fivefold repression). In the absence of Mod(mdg4)-67.2 binding, the story is even more complicated. Even with the additional 50-bp spacing, the insulator represses transcription in the mod(mdg4)u1 background. In this case, there is a 24-fold difference between the wild-type and mod(mdg4)u1 backgrounds (fourfold stimulation versus sixfold repression, respectively). The direct repression in the latter case is not simple steric blocking but is likely mediated via the two acidic domains of Su(Hw) (16, 18). Over larger distances, however, the insulator still stimulates transcription, albeit somewhat less strongly, without Mod(mdg4)-67.2 binding.

In view of these findings, some earlier studies must be interpreted with caution. The spacing between the promoter and the insulator, the proteins interacting with the promoter in the particular tissue, and, in all likelihood, the proximity of DNA binding sites for key transcription factors within the enhancer could influence the outcome. Certainly, the results of others are consistent with the idea that the insulator influences transcription directly at the level of the promoter when located within about 1.5 kb of the promoter (18, 22). In contrast, enhancer blocking by the insulator is independent of spacing. In agreement with the results of others, we observed blocking of a strong enhancer in the larval fat body regardless of the spacing between the insulator and the promoter (59, 60). Thus, interpretation of some earlier studies is complicated by the possibility that the insulator might itself stimulate transcription in some cases (while at the same time blocking distal enhancers) in a wild-type mod(mdg4) background. This would explain, for example, why the wing blade and body cuticle enhancers of the yellow gene appear not to be completely blocked in the gypsy-induced y2 allele (18).

The fact that the insulator can act as a promoter element provides a biologically sound rationale for its location in the promoter region of the gypsy retrotransposon. The gypsy insulator thus resembles GAGA sites that bind GAGA factor, a protein encoded by trithorax-like. GAGA sites are found both in chromosomal boundary elements and in promoters (39). Consistently, the BTB domain encoded by mod(mdg4) can functionally substitute for the GAGA factor's BTB domain in transcriptional stimulation (2, 47, 63). The GAGA factor's BTB domain functions to remodel nucleosomal templates in conjunction with NURF (43, 55). However, at certain chromosomal sites, and in the presence of particular protein-protein interactions, GAGA factor instead binds corepressors that mediate chromatin condensation via deacetylation of histones (13). Thus, either chromatin condensation or chromatin remodeling activities could be mediated by the gypsy insulator. Our results favor the latter possibility, at least for the larval fat body.

Local remodeling of chromatin structure provides an attractive mechanistic connection between enhancer blocking and transcriptional stimulation. It is important to note that the same 430-bp insulator sequence used here effectively blocks enhancer-promoter interactions, even in the larval fat body, a tissue where we clearly see transcriptional stimulation (17, 24, 45, 60). Both enhancer blocking by the insulator (24) and the transcriptional stimulation we observed (unpublished observation) are independent of insulator orientation. Thus, the insulator is not a promoter per se, nor does it act in a manner expected for a core promoter element such as the TATA box (12).

Rather, we propose that the gypsy insulator is analogous to promoter-proximal regulatory modules that coordinate inputs from a variety of enhancer sequences and convey these to target promoters (61). The capacity of such a module to accept inputs is expected to be saturable, as is enhancer blocking by the gypsy insulator (50). The recent demonstration that the BTB domain of Mod(mdg4)-67.2 interacts with Chip, a protein involved in long-distance enhancer-promoter interactions, is also consistent with this model (15).

A similar mechanism may apply to a number of insulators. For example, evaluation of the Drosophila genomic sequence indicates that the scs insulator is located in a promoter region (1, 14). Similarly, the facet-strawberry mutation removes an insulator that maps immediately upstream of, or partially overlaps with, the promoter of the Notch gene (58). The model predicts that any such promoter-proximal regulatory module would display insulator function if assayed outside the context of the native promoter. An insulator would result when the bound proteins retained their ability to interact with enhancers but failed to interact productively with the promoter—due either to location or to particular protein-protein interactions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. Geyer for providing Drosophila stocks. We also thank P. Geyer, V. Corces, and D. Dorsett for sharing with us their unpublished results.

W.W. was supported in part by a Merit Fellowship from the University of Louisville Center for Genetics and Molecular Medicine. This work was supported by the University of Louisville and by NIH monies to M.D.B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams M D, et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albagli O, Dhordain P, Deweindt C, Lecocq G, Leprince D. The BTB/POZ domain: a new protein-protein interaction motif common to DNA- and actin-binding proteins. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:1193–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackwood E M, Kadonaga J T. Going the distance: a current view of enhancer action. Science. 1998;281:60–63. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan M D, Dickinson W J. Complex developmental regulation of the Drosophila affinidisjuncta alcohol dehydrogenase gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1988;125:64–74. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan M D, Rowan R G, Dickinson W J. Introduction of a functional P element into the germ-line of Drosophila hawaiiensis. Cell. 1984;38:147–151. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Büchner K, Roth P, Schotta G, Krauss V, Saumweber H, Reuter G, Dorn R. Genetic and molecular complexity of the position effect variegation modifier mod(mdg4) in Drosophila. Genetics. 2000;155:141–157. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai H, Levine M. The gypsy insulator can function as a promoter-specific silencer in the Drosophila embryo. EMBO J. 1997;16:1732–1741. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai H N, Shen P. Effects of cis arrangement of chromatin insulators on enhancer-blocking activity. Science. 2001;291:493–495. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5503.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung J H, Whiteley M, Felsenfeld G. A 5′ element of the chicken β-globin domain serves as an insulator in human erythroid cells and protects against position effect in Drosophila. Cell. 1993;74:505–514. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80052-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorn R, Krauss V, Reuter G, Saumweber H. The enhancer of position-effect variegation of Drosophila, E(var)3-93D, codes for a chromatin protein containing a conserved domain common to several transcriptional regulators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11376–11380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorsett D. Distance-independent inactivation of an enhancer by the suppressor of Hairy-wing DNA-binding protein of Drosophila. Genetics. 1993;134:1135–1144. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.4.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorsett D. Distant liaisons: long-range enhancer-promoter interactions in Drosophila. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:505–514. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espinas M L, Canudas S, Fanti L, Pimpinelli S, Casanova J, Azorin F. The GAGA factor of Drosophila interacts with SAP18, a Sin3-associated polypeptide. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:253–259. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farkas G, Udvardy A. Sequence of scs and scs′ Drosophila DNA fragments with boundary function in the control of gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:2604. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.10.2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gause M, Morcillo P, Dorsett D. Insulation of enhancer-promoter communication by a gypsy transposon insert in the Drosophila cut gene: cooperation between Suppressor of Hairy-wing and modifier of mdg4 proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4807–4817. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4807-4817.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gdula D A, Corces V G. Characterization of functional domains of the su(Hw) protein that mediate the silencing effect of mod(mdg4) mutations. Genetics. 1997;145:153–161. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gdula D A, Gerasimova T I, Corces V G. Genetic and molecular analysis of the gypsy chromatin insulator of Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9378–9383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Georgiev P, Kozycina M. Interaction between mutations in the suppressor of Hairy wing and modifier of mdg4 genes of Drosophila melanogaster affecting the phenotype of gypsy-induced mutations. Genetics. 1996;142:425–436. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.2.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Georgiev P G, Gerasimova T I. Novel genes influencing the expression of the yellow locus and mdg4(gypsy) in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;220:121–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00260865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerasimova T I, Byrd K, Corces V G. A chromatin insulator determines the nuclear localization of DNA. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1025–1035. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerasimova T I, Corces V G. Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins mediate the function of a chromatin insulator. Cell. 1998;92:511–521. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80944-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerasimova T I, Gdula D A, Gerasimov D V, Simonova O, Corces V G. A Drosophila protein that imparts directionality on a chromatin insulator is an enhancer of position-effect variegation. Cell. 1995;82:587–597. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerasimova T I, Corces V G. Boundary and insulator elements in chromosomes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geyer P K, Corces V G. DNA position-specific repression of transcription by a Drosophila Zinc finger protein. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1865–1873. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geyer P K, Spana C, Corces V G. On the molecular mechanism of gypsy-induced mutations at the yellow locus of Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO J. 1986;5:2657–2662. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geyer P K. The role of insulator elements in defining domains of gene expression. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:242–248. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh D, Gerasimova T I, Corces V G. Interactions between the Su(Hw) and Mod(mdg4) proteins required for gypsy insulator function. EMBO J. 2001;20:2518–2527. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hagstrom K, Müller M, Schedl P. Fab-7 functions as a chromatin domain boundary to ensure proper segment specification by the Drosophila bithorax complex. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3202–3215. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.24.3202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrison D A, Gdula D A, Coyne R S, Corces V G. A leucine zipper domain of the suppressor of Hairy-wing protein mediates its repressive effect on enhancer function. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1966–1978. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holdridge C, Dorsett D. Repression of hsp70 heat shock gene transcription by the Suppressor of Hairy-wing protein of Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1894–1900. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu J, Qazzaz H, Brennan M D. A transcriptional role of conserved footprinting sequences within the larval promoter of a Drosophila alcohol dehydrogenase gene. J Mol Biol. 1995;249:259–269. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kellum R, Schedl P. A group of scs elements function as domain boundaries in an enhancer-blocking assay. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2424–2431. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kellum R, Schedl P. A position-effect assay for boundaries of higher order chromosomal domains. Cell. 1991;64:941–950. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90318-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim J, Shen B, Rosen C, Dorsett D. The DNA-binding and enhancer-blocking domains of the Drosophila suppressor of Hairy-wing protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3381–3392. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mallin D R, Myung J S, Patton S, Geyer P K. Polycomb group repression is blocked by the Drosophila suppressor of Hairy-wing [su(Hw)] insulator. Genetics. 1998;148:331–339. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.1.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKenzie R W, Hu J, Brennan M D. Redundant cis-acting elements control expression of the Drosophila affinidisjuncta Adh gene in the larval fat body. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1257–1264. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.7.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKenzie R W, Brennan M D. cis-acting sequences contributing to expression of the Drosophila affinidisjuncta Adh gene in both larvae and adults. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;28:869–873. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(98)00072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mihaly J, Hogga I, Barges S, Galloni M, Mishra R K, Hagstrom K, Müller M, Schedl P, Sipos L, Gausz J, Gyurkovics H, Karch F. Chromatin domain boundaries in the Bithorax complex. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1998;54:60–70. doi: 10.1007/s000180050125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mishra R K, Mihaly J, Barges S, Spierer A, Karch F, Hagstrom K, Schweinsberg S E, Schedl P. The iab-7 Polycomb response element maps to a nucleosome-free region of chromatin and requires both GAGA and Pleiohomeotic for silencing activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1311–1318. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1311-1318.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Modolell J, Bender W, Meselson M. Drosophila melanogaster mutations suppressible by the suppressor of Hairy-wing are insertions of a 7.3-kilobase mobile element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:1678–1682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.6.1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muravyova E, Golovnin A, Gracheva E, Parshikov A, Belenkaya T, Pirrotta V, Georgiev P. Loss of insulator activity by paired Su(Hw) chromatin insulators. Science. 2001;291:495–498. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5503.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norrander J, Kempe T, Messing J. Construction of improved M13 vectors using oligodeoxynucleotide-directed mutagenesis. Gene. 1983;26:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okada M, Hirose S. Chromatin remodeling mediated by Drosophila GAGA factor and ISWI activates fushi tarazu gene transcription in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2455–2461. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parkhurst S M, Harrison D A, Remington M P, Spana C, Kelley R L, Coyne R S, Corces V G. The Drosophila su(Hw) gene, which controls the phenotypic effect of the gypsy transposable element, encodes a putative DNA-binding protein. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1205–1215. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.10.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parnell T J, Geyer P K. Differences in insulator properties revealed by enhancer-blocking assays on episomes. EMBO J. 2000;19:5864–5874. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pirrotta V. Vectors for P-mediated transformation in Drosophila. In: Rodrigues R L, Denhardt D T, editors. Vectors: a survey of molecular cloning vectors and their uses. Boston, Mass: Butterworths; 1988. pp. 437–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Read D, Butte M J, Dernburg A F, Frasch M, Kornberg T B. Functional studies of the BTB domain in the Drosophila GAGA and Mod(mdg4) proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3864–3870. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.20.3864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roseman R R, Pirrotta V, Geyer P K. The su(Hw) protein insulates expression of the Drosophila melanogaster white gene from chromosomal position-effects. EMBO J. 1993;12:435–442. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05675.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rothberg I, Hotaling E, Sofer W. A Drosophila Adh gene can be activated in trans by an enhancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5713–5717. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.20.5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scott K C, Taubman A D, Geyer P K. Enhancer blocking by the Drosophila gypsy insulator depends upon insulator anatomy and enhancer strength. Genetics. 1999;153:787–798. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.2.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith P A, Corces V G. The suppressor of Hairy-wing binding region is required for gypsy mutagenesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;233:65–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00587562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith P A, Corces V G. The suppressor of Hairy-wing protein regulates the tissue-specific expression of the Drosophila gypsy retrotransposon. Genetics. 1995;139:215–228. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spana C, Harrison D A, Corces V G. The Drosophila melanogaster suppressor of Hairy-wing protein binds to specific sequences of the gypsy retrotransposon. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1414–1423. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.11.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tjian R, Maniatis T. Transcriptional activation: a complex puzzle with few easy pieces. Cell. 1994;77:5–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsukiyama T, Daniel C, Tamkun J, Wu C. ISWI, a member of the SW12/SNF2 ATPase family, encodes the 140 kDa subunit of the nucleosome remodeling factor. Cell. 1995;83:1021–1026. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Udvardy A, Maine E, Schedl P. The 87A7 chromomere identification of novel chromatin structures flanking the heat shock locus that may define the boundaries of higher order domains. J Mol Biol. 1985;185:341–358. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Vlag J, den Blaauwen J L, Sewalt R G A B, van Driel R, Otte A P. Transcriptional repression mediated by polycomb group proteins and other chromatin-associated repressor is selectively blocked in insulators. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:697–704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vazquez J, Schedl P. Deletion of an insulator element by the mutation facet-strawberry in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2000;155:1297–1311. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.3.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wei W. Polarity of transcriptional enhancement and chromatin insulator function in Drosophila. Ph.D. thesis. Louisville, Ky: University of Louisville; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wei W, Brennan M D. Polarity of transcriptional enhancement revealed by an insulator element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14518–14523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011529598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yuh C-H, Bolouri H, Davidson E H. Genomic cis-regulatory logic: experimental and computational analysis of a sea urchin gene. Science. 1998;279:1896–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5358.1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zar J H. Biostatistical analysis. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zollman S, Godt D, Privé G G, Couderc J-L, Laski F A. The BTB domain, found primarily in zinc finger proteins, defines an evolutionarily conserved family that includes several developmentally regulated genes in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10717–10721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]