Abstract

Wound healing is a complex and dynamic physiological process consisting of a series of cellular and molecular events that initiate immediately after a tissue lesion, to reconstruct the skin layer. It is indubitable that patients with chronic wounds, severely infected wounds, or any metabolic disorder of the wound microenvironment always endure severe pain and discomfort that affect their quality of life. It is essential to treat chronic wounds for conserving the physical as well as mental well-being of affected patients and for convalescing to improve their quality of life. For supporting and augmenting the healing process, the selection of pertinent wound dressing is essential. A substantial reduction in healing duration, disability, associated cost, and risk of recurrent infections can be achieved via engineering wound dressings. Hydrogels play a leading role in the path of engineering ideal wound dressings. Hydrogels, comprising water to a large extent, providing a moist environment, being comfortable to patients, and having biocompatible and biodegradable properties, have found their success as suitable wound dressings in the market. The exploitation of hydrogels is increasing perpetually after substantiation of their broader therapeutic actions owing to their resemblance to dermal tissues, their capability to stimulate partial skin regeneration, and their ability to incorporate therapeutic moieties promoting wound healing. This review entails properties of hydrogel supporting wound healing, types of hydrogels, cross-linking mechanisms, design considerations, and formulation strategies of hydrogel engineering. Various categories of hydrogel wound dressing fabricated recently are discussed based on their gel network composition, degradability, and physical and chemical cross-linking mechanisms, which provide an outlook regarding the importance of tailoring the physicochemical properties of hydrogels. The examples of marketed hydrogel wound dressings are also incorporated along with the future perspectives and challenges associated with them.

1. Introduction

Skin injuries exemplify a perilous health threat to the human body, as body fluid retention, thermal insulation, and fortification from exogenous pathogens rely on integral skin barrier function. The endogenous healing process initiates instantaneously after an injury. The wound healing process encompasses a series of discrete events occurring in specific order and time frame. Acute wounds heal completely, both functionally and anatomically, within 8 to 12 weeks after an injury.1,2 If the wound healing process is disturbed by any factors, then it fails to heal within the standard time duration. Such wounds are termed as chronic wounds or nonhealing wounds. The prevalance of chronic wounds is also increasing globally because of changes in lifestyle, age factor, and the presence of diseases such as diabetes, cardiac disorders, cancer, etc.3 It has been estimated that, by 2026, chronic wounds will affect about 20–60 million people globally.4 Long-term hospitalization is associated with chronic wounds, which imparts a high burden on the medical system owing to the costs related to surgeries, advanced wound care products, and physician and nursing resources. However, despite the medical assistance, serious complications such as severe infection leading to foot amputation, morbidity, and mortality have increased as effective therapies have not been developed. The 5 year mortality rate of chronic wounds is reported to be worse than some common cancer types that include colon cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancer.5,6

The traditional therapies for chronic wound management are dependent on daily wound management: application of wound dressings to provide a moist environment or absorb wound exudate, and debridement to remove infected and/or necrotic tissue. Advanced wound therapies involve microbicidal dressings, application of growth factors, and skin substitutes.7,8 Nowadays, modern dressings such as foam, films, hydrogels, hydrocolloids, and nanofibers have attracted more attention as they provide ideal wound healing conditions, provide a moist environment and an antibacterial healing environment and actively promote the wound healing process.9 Among these dressings, hydrogels offer numerous advantages owing to high porosity, biocompatibility, modifiable degradation rate, interconnected microporous network, ability to maintain a moist microenvironment, and absorbtion of tissue exudates and providing a suitable condition to promote cellular functions such as proliferation and migration. They are three-dimensional hydrophilic gels that swell rapidly in water and form a semisolid matrix. The hydrogels’ water content exceeds 90% that provides better conditions to maintain a moist environment at the wound interface.10,11 The moist environment provides a cooling sensation and reduces the risk of scar formation. Also, owing to the high porosity of the hydrogel, the transmission of oxygen is facilitated, which allows tissue to “breathe”. They exhibit unique properties such as good elasticity, nonadhesion, and structural similarity to the extracellular matrix (ECM). Furthermore, hydrogels proffer several benefits as wound dressing owing to their mild processing conditions as well as their capacity to incorporate bioactive agents. The advancement in hydrogel wound dressing encompasses the development of active dressings, wherein hydrogels comprising agents that augment the wound healing process are designed. Different bioactive agents such as anti-inflammatory molecules, antibiotics, antioxidants, stem cells, growth factors, etc. can be incorporated into the hydrogel to promote wound healing. A thorough understanding of biochemical cues of the wound healing process and the hydrogel fabrication will be beneficial to attain optimal wound healing outcomes.

The architecture and structure of the hydrogel should be engineered in such a way that it fosters proper skin regeneration. For cell attachment, proliferation, and spreading, the mechanical strength of hydrogel should match with the native tissue. The morphological characteristics should mimic the ECM, and it should have suitable porosity for supporting cell infiltration and nutrient transport. Other factors such as degradability and water retention capability are also necessary to be optimized. The structural properties of the hydrogel are influenced by the type of polymer (natural, synthetic, or semisynthetic) used, the cross-linking method, the concentration of the polymer, and the fabrication method.12 This review provides an outlook regarding the hydrogels’ current research status as wound dressings and highlights the types of hydrogels, cross-linking techniques, and novel hydrogel structures. It provides brief information on novel hydrogel-based approaches investigated for the treatment of chronic wounds. The key hydrogel properties that facilitate the wound healing process and make them a suitable candidate for wound healing are also discussed herein. Moreover, the marketed hydrogel products for chronic wound treatment and the future perspective of hydrogels as a wound dressing are also discussed in this review.

2. Pathophysiology of Wounds

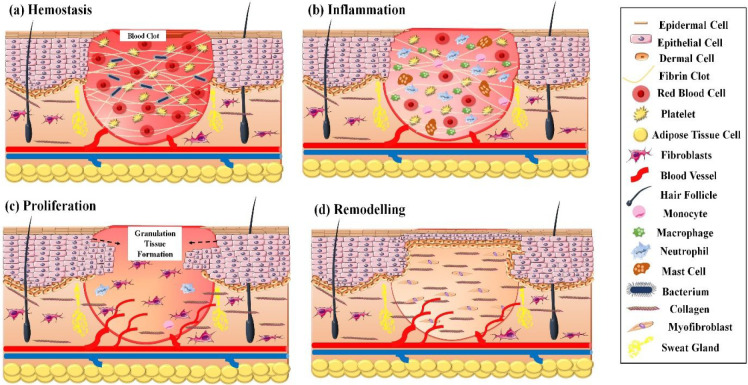

The wound healing process comprises four key phases, namely, (a) hemostasis, (b) inflammation, (c) proliferation, and (d) remodeling. A series of closely regulated events involving phagocytosis, chemotaxis, collagen degradation, nucleogenesis, and collagen remodeling exists within these key phases of wound healing. Moreover, a coordinated proliferation and migration of fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and other cell types are required to synthesize granulation tissue and thereby restore the epithelial layer.13

2.1. Hemostasis

The hemostasis phase initiates immediately after an injury due to the activation of platelets and the release of numerous molecules at the injury site. The extrinsic clotting cascade gets activated owing to the release of clotting factors from the injured skin. Further, the intrinsic clotting factors also get activated after the thrombocytes adhere to the subendothelium surface. The thrombus formation and vasoconstriction help to stop bleeding from the wound. The thrombus clot formation acts as a scaffold for various cells required in later stages of wound healing. Furthermore, the release of growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and transforming growth factor-β (TGF- β), and a group of cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and IL-10 also occurs in this early phase that initiates the preliminary stages of wound healing.14,15

2.2. Inflammation

The release of VEGF leads to the initiation of the inflammatory phase. In this phase, an influx of several enzymes, growth factors, nutrients, leucocytes, and antibodies occur at the wound site. The inflammatory response is arbitrated via the monocytes (that differentiates into macrophages) and neutrophils. The key role of neutrophils is to control infection while macrophages are involved in removal of cellular debris and providing signals for activating myofibroblasts and fibroblasts.16 The TGF-β and cytokines release stimulates neutrophil infiltration, promoting early defense against microbial invasion. A high amount of neutrophils remains in the inflamed tissue for up to 48 h. Along with neutrophils, the proteinases also release, which provides phagocytic activity and clears debris and pathogens from the wound bed. The macrophages reach their highest concentration within 48 to 72 h postinjury. Thereafter the release of epidermal growth factor (EGF) occurs, which helps in the regulation of the inflammation process, initiates angiogenesis, and aids granulation tissue formation. After 3 days of injury, heparin-binding EGF and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) releases in the wound bed. Their release aids the formation of ECM and collagen remodeling. An excessive infiltration of leucocytes occurs in chronic wounds which leads to increased concentration of proteases, radicals, and cytokines.17

2.3. Proliferation

The proliferation phase initiates 3–5 days postinjury. This phase accelerates the angiogenesis process, granulation tissue formation, epithelialization, and collagen deposition. The neovascularization begins due to hypoxia in the wound bed. A complex of leaky capillaries is formed during granulation tissue formation that leads to increased wound fluid volume. Numerous cytokines and chemokines released in the inflammatory phase attract fibroblasts, lymphocytes, endothelial cells, myofibroblasts, and keratinocytes in the wound bed. Also, there is a key role of growth factors in stimulation of epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and promotion of cell migration into the wound site. Growth factors like FGF and VEGF stimulate growth and migration of endothelial cells and thereby promote vascularization at the wound site. Keratinocytes migration from the edge of the wound toward the wound bed helps to restore skin functions. Proteolytic enzymes (metalloproteases) get secreted from fibroblasts that secrete cellular fibronectin and digest plasma fibronectin. The proliferation of fibroblasts helps in the formation of granulation tissue which in turn replaces the initially formed clot. Five days postinjury, the collagen formation reaches the maximum, which helps in the bridging of wound bed edges. The myofibroblasts function to reduce the volume of tissue required for wound healing and also reduce scar formation.18

2.4. Remodeling

Remodeling, also known as the maturation phase, is the fourth phase of wound healing. Generally, it initiates 3 weeks after the injury and continues for up to 2 years. In this phase, the type-III soft and gelatinous collagen, formed in the proliferation phase, gets replaced by well-structured type-I collagen. Throughout this phase, the tensile strength of the tissue increases. The tensile strength increases gradually up to 50% over 3 months and reaches about 80% over a year.19 The clinical representation of wound maturation comprises several events such as contraction, decrease in thickness, redness, and enhanced strength. The wound maturation phase involves key players such as MMPs, collagen, fibroblasts, and blood vessels. The production and functioning of tissue inhibitor of MMP (TIMP) and MMP are responsible for breakdown of collagen. An increased expression of mRNA levels of TIMP-2, MMP-2, and MMP-7, while reduced expressions of TIMP-1, MMP-1 and MMP-9, and mRNA levels are observed before ECM remodeling. Thus, a synchronized expression of different MMPs and TIMPs is essential for proper wound maturation.14 A schematic representation of phases of wound healing is elucidated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the distinct phase of normal wound healing process: (a) hemostasis, (b) inflammation, (c) proliferation, and (d) remodelling.

2.5. Acute vs Chronic wounds

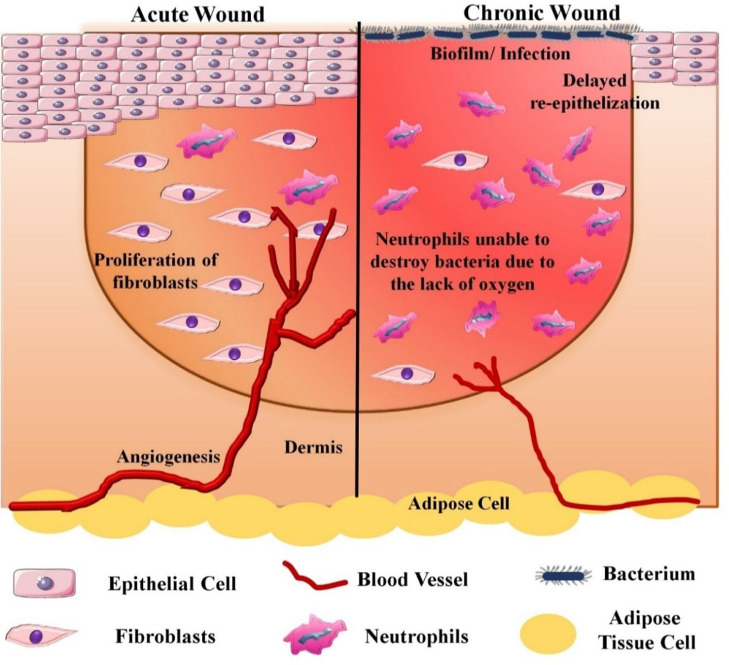

As described above, several factors and regulating molecules are involved in the wound healing process, which anticipates that even minor deviations could affect and delay the healing. Numerous aspects affect the healing process, such as age, nutrition, genetics, chronic diseases, hypoxia, infection, immunosuppression, etc. Acute wounds heal within 8 to 12 weeks postinjury. However, any change in the normal wound healing process leads to chronic wound formation. Chronic wounds involve venous ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers, arterial ulcers, ischemic ulcers, and pressure ulcers. Wound management is also affected by the extent and severity of wound infection.20 In diabetic patients, alterations are observed in all four phases of wound healing. The inflammatory phase gets prolonged due to the effect of long-term hyperglycemia. Also, peripheral neuropathy lowers the limbs sensitivity, which hinders the detection of ulcers in the initial stages. The expression of regulatory molecules involved in the inflammatory phase gets reduced due to the changes in neuroimmune interactions in diabetes. The tissue regeneration also gets affected owing to reduced blood flow.21 Also, the ATP generation, fibroblast migration, keratinocytes migration, and oxygen availability to the wound bed reduce. Hyperglycemia also leads to enhanced activity of NADPH oxidases which in turn increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Increased ROS production leads to lipid peroxidation, DNA damage, and protein modification and also changes the fibroblasts and keratinocytes functioning. Further, due to increased pro-inflammatory molecules (MMP-9, TNF-α, and IL-1β), and anti-inflammatory cytokines shortage (IL-10, and TGF-β), a delay in tissue regeneration occurs. The chances of secondary infections also increase due to a compromised immune system. Due to high levels of glucose, the advanced glycation end products (AGEs) generation increases, which leads to a delay in wound healing.22 A schematic representation of acute vs chronic wounds is represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic elucidation of acute vs chronic wounds. In acute wounds, optimum angiogenesis promotes fibroblasts proliferation, neutrophils anti-infective activities, and re-epithelialization. With chronic wounds, prolonged local bacterial infections hinder angiogenesis, fibroblasts proliferation, and anti-infective activity of neutrophils.

3. Properties of Hydrogel

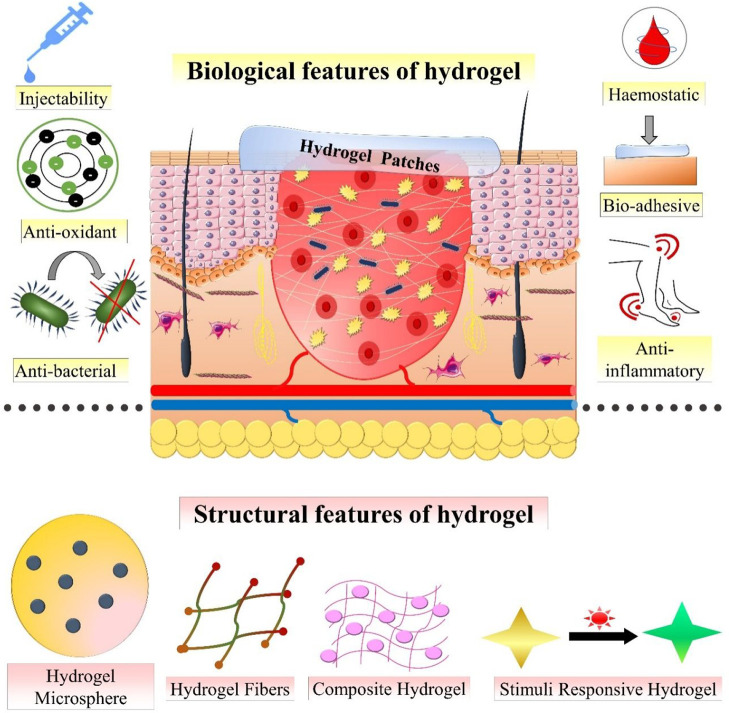

Hydrogels are designed by using hydrophilic/hydrophobic polymers and cross-linking agents that have a strong affinity for aqueous media. Due to the hydrophilic nature of polymer and the porous and three-dimensional structure of hydrogel, it expresses a high rate of water absorption at the site of application.23 The cross-linking ability of the polar functional groups like amide, amino, carboxyl, and hydroxyl groups in the structure of the polymer is associated with the hydrophilic properties of hydrogels. Hydrogel is an ideal dressing candidate for wound healing owing to its properties such as high water content, bio-adhesiveness, biocompatibility, and malleability. Hydrogel demonstrates the swelling and deswelling property in aqueous solution; therefore, they are utilized in various fields such as regenerative medicine and drug delivery systems for the treatment of wounds.24 The moisture exchanging activities demonstrated by hydrogels help to attain an optimum microclimate between the dressing and the wound bed. This results in the promotion of the wound healing process in a more effective manner. The hydrogel dressings also provide a soothing, cooling effect and also lessen the pain allied with dressing changes, owing to their high moisture content.25 Furthermore, hydrogel dressings can be easily removed from the site of the wound without producing any type of additional damage to the healing tissue. The transparency of some hydrogels permits clinical evaluation of the wound healing process without removing it from the site of application. Recently, stimuli responsive hydrogels have been widely used for wound management as they provide controlled release and diffusion of the loaded bioactives.26 Some of the key properties of hydrogels making them an ideal wound dressing are described below and schematically represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Biological and structural features of hydrogels to enhance wound healing.

3.1. Biocompatibility

It is a prerequisite that the hydrogel must be nontoxic and should not initiate foreign body response, as they have to be applied directly on the wounds. Hence, it is essential that the hydrogel should be biocompatible. For evaluating the biocompatibility, in vitro and/or in vivo toxicity studies and hemolysis testing are performed. A simple and easy way to ensure the biocompatibility of a hydrogel is to use biocompatible components during formulation. Furthermore, to prevent unexpected toxicities, the hydrogel can be designed by using highly pure polymer and biocompatible methods like safe UV exposure. Hydrogel dressings should be changed routinely until complete wound healing, to maintain its efficiency and protect the wound from infections.27

3.2. Adhesiveness and Shape Adaptability

For wound dressing applications, the hydrogels must adhere properly to cover the wound and thereby protect the wound microenvironment from external factors. The firm adherence of hydrogel prevents gas or fluid leakage from the wound as well as protects the wound from bacterial infections. Furthermore, proper adherence is also necessary at the initial wound healing phase, i.e., hemostasis, to rapidly stop the bleeding. Due to the uneven and irregular shape of the wound, incomplete coverage of the wound dressing may result in bacterial infections or delayed healing. So, the hydrogel dressings must ensure complete wound coverage via quickly adapting to the wound shape.28

3.3. Injectability

Injectable hydrogels are injected as liquid to the wound site, which thereafter forms an in situ solid hydrogel (i.e., polymerize) via a cross-linking reaction. The polymerization occurs usually via several external stimuli such as pH, temperature, light, enzyme, or electromagnetic field. The injectable hydrogels possess better fluidity compared to traditional hydrogels. After injecting it onto the wound, it spreads in three dimensions that in turn allows a proper reach to the irregular and deep wounds. The injectable hydrogels can also be utilized as a temporary scaffold or drug delivery carrier for cell differentiation and proliferation. Bioactive molecules, drugs, and stem cells can be injected into the wound site via their addition in the injectable hydrogel.29,30

3.4. Self-Healing Property

Self-healing hydrogels are a type of hydrogel that possess the capability to self-heal. Recently, they have attained more attention in chronic wound repair owing to their intrinsic high structural stability due to their capacity to maintain their shape integrity even after mechanical destruction. They offer the benefits of increased life of the dressings, prevention from secondary injury, and the ability to retain their shape via various self-repair mechanisms. Several researchers have fabricated various self-healing hydrogels for chronic wound management.31

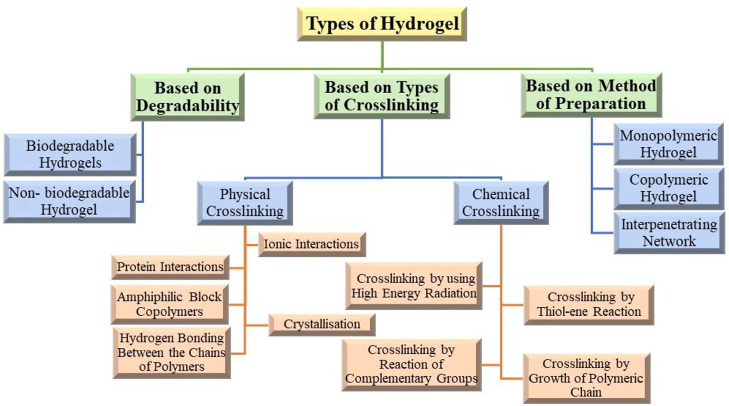

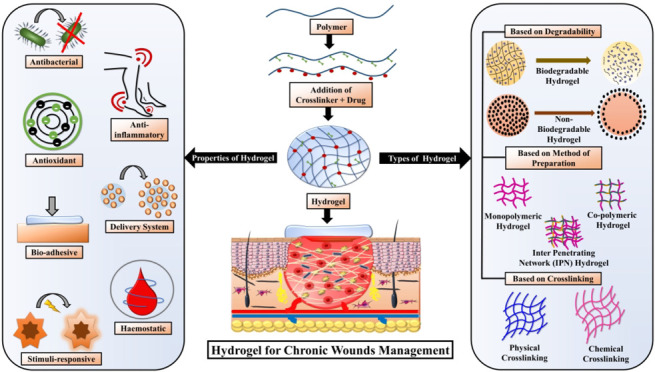

4. Types of Hydrogels

Various types of hydrogels are described in this section based on their properties. A schematic representation of the classification of the types of hydrogels is represented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Classification of various types of hydrogels based on degradability, method of preparation, and types of cross-linking.

4.1. Types of Hydrogels Based on Degradability

The hydrogels are divided into two different categories based on their mode of degradation: (1) biodegradable hydrogels; (2) non-biodegradable hydrogels.

4.1.1. Biodegradable Hydrogels

The term “biodegradable” implies that the material can be degraded by biological mechanisms like enzymatic degradation and/or microbial degradation. The biodegradable polymers are significantly utilized in the biomedical field for the development of drug delivery systems. Management of a wound by using undegradable material results in low mechanical strength, less binding capacity, less biocompatibility and less bio-adhesiveness. To overcome such difficulties, biodegradable polymers incorporated hydrogels (biodegradable hydrogels) are designed and utilized. The fundamental qualities of biodegradable hydrogel, such as biocompatibility, nontoxicity, swelling properties, bioeffectiveness, and bio-adhesiveness, have been described by many researchers in numerous studies.32 A strong three-dimensional network is created during the formation of hydrogel that covers the entire wound, mimics cell proliferation, and restores the tissue at the site of wound. Numerous polymers, both natural and synthetic, are extensively utilized in hydrogel preparation, due to their nature of biodegradation. Natural polysaccharides such as chitosan, starch, cellulose, chitin, etc. and protein and peptides such as keratin, collagen, fibrin, and albumin are extensively utilized to design hydrogels, due to their biocompatible and biodegradable characteristics. These natural polymers have the ability to provide physicochemical integrity to the newly growing cells during the wound healing process. Synthetic polymers, such as, poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly-ε-caprolactone, poly(vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP), poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA), and poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) are extensively utilized due to their considerable mechanical strengths at the site of wound. This leads to the appropriate functioning of ECM at the site of the wound, proper release of various autocoids as well as growth factors, and formation and deposition of collagen.33 Several research studies involving fabrication and evaluation of biodegradable hydrogels for chronic wound treatment are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Recently Developed Biodegradable Polymeric Hydrogel for Chronic Wound Management.

| Name of Polymer | Name of Drug/Wound Healing Agents | Description | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Honey | A honey, chitosan, poly(vinyl alcohol), and gelatin containing hydrogel was designed by implementing freeze–thawing method and physical cross-linking approach. While designing the hydrogel, different concentrations of honey were used, while the ratio of chitosan, poly(vinyl alcohol), and gelatin was kept in the proportion of 2:1:1 (v/v), respectively. An in vivo study of the designed hydrogel demonstrated no toxicity and similarity in microstructure of the hydrogel with the structure of ECM. The result of the MTT assay confirmed the growth of the cell and reduction in the area of zone of inhibition. An in vivo study of the formulation displayed the maturation of collagen and re-epithelialization on the 20th day after treatment in the groups treated with the formulation as compared to the group treated with gauze (control group). | (34) |

| Metal ions (silver, zinc, and copper) | Metal ions such as silver, zinc, and copper were combined with chitosan to prepare a hydrogel using a freeze–thaw method. The hydrogel was further coated on the surface of ordinary gauze for the management of chronic wounds. An in vivo study of the formulation demonstrated significant antibacterial effect due to the release of the metal ions from ordinary gauze. The release of metal ions was effective in killing S. aureus and also improved the keratinocytes migration. The in vivo results displayed the formation of tissue, deposition of collagen, and maturation. Additionally, immunochemistry and immunofluorescence staining of newly grown tissue confirmed the angiogenesis, re-epithelization, and reduction in inflammation. | (35) | |

| Silver nanoparticles | A silver nanoparticles impregnated chitosan–PEG hydrogel was formulated by using glutaraldehyde as a cross-linking agent for the management of wound in a type-2 diabetic rabbit model. The optimized formulation displayed significant antioxidant and antibacterial effects in in vitro analysis. An in vivo experiment in type-2 diabetes induced rabbit model exhibited shrinkage of the wound, better re-epithelialization, and significant keratinocytes migration. | (36) | |

| Tannic acid | Tannic acid incorporated methacrylate chitosan hydrogel and methacrylate silk fibroin hydrogel were formulated by using the cross-linking process for the treatment of full-thickness wounds. The results of the in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated no toxicity for fibroblast cells (NIH–3T3 cells) and promoted re-epithelization and granulation tissue re-formation in the mice model, respectively. | (37) | |

| Recombinant human collagen peptide | The recombinant human collagen peptide conjugated chitosan hydrogel was formulated for the treatment of second-degree burns. The exhibited results of the in vivo study were promotion of cell infiltration, vessel formation, and complete wound healing in the rat model. | (38) | |

| Cellulose | Silver nanoparticles, curcumin, cyclodextrin, bacterial cellulose | A silver nanoparticles, curcumin, cyclodextrins, and bacterial cellulose containing hydrogel was prepared by implementing a green synthesis and microencapsulation approach. The optimized formulation displayed broad spectrum antimicrobial activity against S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and C. auris (MTT assay). Moreover, the hydrogel also exhibited optimum antioxidant properties and cytocompatibility with various cell lines. | (39) |

| Bacterial cellulose and acrylic acid | A bacterial cellulose and acrylic acid impregnated hydrogel was designed by applying an irradiation approach followed by freeze–drying. The formulation depicted excellent cell attachment and cell viability during in vitro analysis. The in vivo experiment results depicted that the formulation acted as a carrier for the delivery and growth of keratinocytes and fibroblasts in a full-thickness wound model. | (40) | |

| Nonwoven cotton | A cellulose containing hydrogel was designed by sol–gel method with reinforcement of nonwoven cotton as a sustainable wound dressing application. For the improvement of antibacterial properties of the formulation, titania particles were embedded. Antibacterial analysis of the formulation by agar disk diffusion technique displayed the inhibition of the bacterial growth. Additionally, the hydrogel also displayed optimum biodegradability and sustainability and was found to be environmentally friendly. | (41) | |

| Fenugreek gum | A fenugreek gum containing hydrogel was prepared by forming a hydrogen bond with cellulose. The hydrogel had characteristics like sufficient mechanical strength, porous structure, thermal stability, and improved water absorption rate. The formulation expressed sufficient biocompatibility, prevention of hemostasis (in vitro), and the process of neovascularization (in vivo). | (42) | |

| Platelet rich plasma | A platelet rich plasma incorporated carboxymethyl cellulose containing hydrogel was designed by implementing the concept of 3D printing technology wherein citric acid was used as a cross-linking agent. The formulation promoted angiogenesis, stem cell migration, dermis formation, and rapid cell proliferation in the diabetic rat model. | (43) | |

| Starch | Crocus sativus | A C. sativus petals extract loaded starch-based hydrogel was designed for atraumatic wound application. The in vitro study confirmed the growth of keratinocytes, antioxidant effect, and self-preserving capacity. Furthermore, the formulation also depicted the antimicrobial effect against S. epidermidis and its utility for the atraumatic wound. | (44) |

| Gelatin | The oxidized starch-gelatin-based hydrogel was prepared as a wound dressing for self-contraction of the non-invasive wound by implementing the Schiff-based reaction concept. The resulting formulation revealed high potential and tissue reconstruction at the site of the wound in the rabbit model as compared to the wound treated with sutures. | (45) | |

| Starch | The starch containing hydrogel was prepared by using calcium nitrate tetrahydrate and neodymium(III) nitrate as a cross-linking agent (ionic cross-linking approach). The formulation depicted maximum adhesiveness, good stretchability, sufficient self-healing, degradability, and significant improvement in viscoelastic properties. The in vitro study of the formulation demonstrated sufficient cytocompatibility to fibroblast cells and human vascular endothelial cells, less hemolysis risk, and antibacterial effect. During the in vivo study, the formulation displayed reduced blood loss at the site of the wound in the rat model. | (46) | |

| Alginate | Naringenin | Naringenin impregnated alginate-based hydrogel was prepared by using the freeze–drying method. The resultant formulation depicted good porosity, no toxicity (in vitro), and re-epithelialization (in vivo) as compared to the wound treated with gauze. | (47) |

| Nitric oxide | A nitric oxide releasing hydrogel was fabricated and characterized to evaluate its effectiveness against methicillin resistant S. aureus infected wounds. Diethylenetriamine/diazeniumdiolate (DETA/NONOate) was utilized as NO donor, and alginate was employed for hydrogel synthesis. The resultant formulation displayed sustained release of nitric oxide for 4 days. The hydrogel demonstrated significant antibacterial action against MRSA. The in vivo experimental results for optimized formulation displayed healed skin structure, increased fibroblasts, and improved angiogenesis. | (48) | |

| α-tocopherol | α-Tocopherol impregnated alginate-based hydrogel was designed by cross-linking approach for wound healing. The designed composition demonstrated a significant increase in granulation tissue formation in the full-thickness wound rat model as compared to the wound treated with gauze. | (49) | |

| Zinc alginate, RL QN15 peptide, polydopamine nanoparticles | Hollow dopamine nanoparticles (pro-regenerative agent) with RL-QN15 peptide (pro-healing peptide) impregnated zinc alginate hydrogel was formulated for the management of diabetic wound healing. The hydrogel reduced inflammation, enhanced angiogenesis, increased collagen deposition, and augmented the wound repair in diabetic mouse full-thickness wound and in vitro skin wound models. | (50) | |

| Hyaluronic acid | Collagen-I | A collagen-I and hyaluronic acid containing hydrogel was formulated by in situ coupling of phenol moieties of collagen-I hydroxybenzoic acid and hyaluronic acid tyramine via horseradish peroxidase. The in vitro study depicted the prominent proliferation of human microvascular endothelial cells and fibroblast cells. Furthermore, an enhancement in the level of VEGF was observed in human microvascular endothelial cell cultured hydrogel. An in vivo experiment in full-thickness wound model demonstrated an anti-inflammatory effect, formation of a new epithelial cell layer on the 7th day of treatment, generation of fibroblasts cells, and collagen content on the 14th day of treatment. | (51) |

| Dopamine hydrochloride | A dopamine hydrochloride containing hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel was formulated by combining the carbodiimide conjugation approach and horseradish peroxidase and hydrogen peroxide cross-linking approach. The in vitro experiment of the MTT assay depicted significant biocompatibility and zero toxicity after 24 and 48 h, respectively. The in vivo experiments on a rat model with liver defect and artery defect demonstrated collagen metabolism, formation of granulation tissue, and prevention of excessive bleeding at the site of the wound. | (52) | |

| Gellan gum | Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells | A gellan gum and collagen comprising full-IPN hydrogel housing adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) was fabricated to promote burn wound regeneration. Successful incorporation of ADSCs into the gellan gum–collagen IPN hydrogel promoted the fibroblast migration, and also improved its anti-inflammatory potential. Moreover, early wound closure, complete skin regeneration, and reduced inflammation were observed after application of the fabricated hydrogel on murine full-thickness burn wounds. | (53) |

| Tetracycline chloride, silver sulfadiazine | Drugs (tetracycline chloride and silver sulfadiazine) containing gellan gum microspheres were impregnated a in double cross-linked, Schiff-based oxidized gellan gum and carboxy methyl chitosan containing hydrogel designed as a drug delivery system for effective wound healing. The formulation displayed a significant antibacterial effect on E. coli and S. aureus during the in vitro experiment. | (54) | |

| Ofloxacin, tea tree oil, lavender oil | Co-encapsulated active therapeutic agents (like ofloxacin, tea tree oil, and lavender oil) containing gellan gum-based hydrogels were prepared by using solvent casting ionotropic gelation method for the treatment of full-thickness wounds. The in vitro experiment of the formulation displayed an antibacterial effect; the initial burst release of the therapeutic agent (first 24 h) and then controlled release of the therapeutic agent were observed for the next 48 h. The in vivo experiments depicted wound contraction after 10 days of treatment. Furthermore, histopathological analysis confirmed the complete healing of the epidermal layer. | (55) | |

| Collagen | Succinyl chitosan, curcumin, collagen | Nanoencapsulated curcumin comprising fish collagen–succinylchitosan composite hydrogel was fabricated for enhancing wound healing. By employing the ionic gelation method, curcumin was incorporated into succinylchitosan nanoparticles. The wound healing potential of the developed hydrogel was evaluated on Wistar albino rats (subcutaneous wound model). The hydrogel enhanced the hydroxyproline content and collagen deposition in the wound tissue. | (56) |

| Collagen | A three-dimensional collagen-based hydrogel was designed for rapid recovery of the wound. For in vivo experiments, a 10 mm excisional wound was created on the dorsum of diabetic rats. After application of the formulation at the site of the wound, it was observed that the wound healing rate was faster than in the group of rats treated with an occlusive dressing. In addition to this, histological analysis confirmed the re-epithelization and dermal structure regeneration. | (57) | |

| EGF | EGF receptor conjugated collagen-based hydrogel was prepared to check its effectiveness in burn and gastric ulcers. The in vitro study of hydrogel exhibited noteworthy biocompatibility as an appropriate extracellular matrix for targeted cells and regenerative cells. During the in vivo experiment, the hydrogel represented an improvement in ulcer healing capacity and less scar formation at the site of the wound as compared to hydrogel alone and controls. | (58) | |

| Elastin | QK peptide (proangiogenic peptide) | QK peptide (pro-angiogenic peptide) and recombinant VEGF containing hydrogels were formulated by implementing the chemical cross-linking approach. The in vitro study of formulation displayed the pro-angiogenic activity of QK peptide because of its binding with VEGF receptor, and new capillary formation. The result of the in vivo experiment confirmed the stimulation of the angiogenesis process, enhancement in cellular migration, and subsequent formation of the capillary structure. | (59) |

| Elastin-derived peptide | An elastin-based hydrogel was designed by implementing visible light cross-linking approach. Cross-linking of methacrylated gelatin and acryloyl-(polyethylene glycol)-N-hydroxysuccinimide modified elastin was done. The resultant formulation expressed optimum mechanical properties, swelling properties, and enzymatic degradation, i.e., biodegradation. The developed hydrogel attracted neutrophils and macrophages to the wound site in mice wound model. The elastin-based hydrogel depicted enhanced angiogenesis, dermal regeneration, and collagen deposition. | (60) | |

| Keratin | Human hair keratin | Human hair keratin containing hydrogel was prepared by implementing a lyophilization process. In vitro evaluation of formulation confirmed the proliferation and migration of keratinocytes and fibroblasts. The result of in vivo experiments confirmed increased re-epithelialization, remodeling, and repairing of dead tissue at the site of the wound in full-thickness wound mouse model. | (61) |

| Albumin | Glycidyl methacrylate, bovine serum albumin | Glycidyl methacrylate and modified bovine serum albumin containing hydrogels were designed by using a photo-cross-linking approach. The result of the in vitro study depicted the 3D encapsulation of a NIH 3T3 fibroblast cell, improvement in levels of cell viability, and cell spreading. The in vivo experiment demonstrated the biocompatible and biodegradable nature of the hydrogel. Moreover, it was also confirmed that the designed formulation can deliver the growth factor at the site of the wound in a controlled manner. | (62) |

| Bovine serum albumin | Bovine serum albumin containing pectin–zeolite hydrogels were formulated by using the ionotropic gelation method (calcium chloride–cross-linking agent; glycerol–plasticizer) to get controlled release of the albumin at the site of the wound. In vitro wound healing assay demonstrated a significant cell growth and migration of fibroblast cells at 48 and 72 h, respectively. | (63) | |

| Fibrin | Stromal vascular fraction cells | A stromal vascular fraction cells impregnated fibrin–collagen hydrogel was prepared by using the chemical cross-linking approach for the treatment of diabetic wounds. During the in vitro study, the cell migration assay confirmed the capability of hydrogel for cell migration at low concentrations. The result of the in vivo study confirmed significant improvement in the process of angiogenesis. | (64) |

| Nitric oxide | Nitric oxide loaded fibrin microparticles impregnated with poly(ethylene glycol)–fibrinogen containing hydrogel were designed by using the cross-linking approach. The in vitro study exhibited good biocompatibility and bio-adhesiveness and confirmed the controlled release of nitric oxide. | (65) |

Furthermore, synthetic polymers provide a platform to deliver the drug in a controlled manner and offer a microenvironment for cell proliferation and maturation. Thus, with the advantages of giving different porosities, required mechanical strengths, and the benefits of biodegradability, it can be concluded that biodegradable hydrogels can be beneficial for treating various types of wounds.66 The chemical structures of various biodegradable polymers are represented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Chemical structures of various biodegradable polymers such as chitosan, cellulose, starch, alginate, hyaluronic acid, gellan gum, collagen, elastin, keratin, fibrin, and albumin.

4.1.2. Non-biodegradable Hydrogels

The term non-biodegradable signifies that the material cannot be degraded by any biological mechanisms like enzymatic degradation and/or microbial degradation. If the material is degraded by any kind of biological mechanisms, then the rate of degradation is very slow. The examples of non-biodegradable materials are plastics, polyethylene materials, and other synthetic materials. Some non-biodegradable materials are utilized for the preparation of pharmaceutical dosage forms like films, hydrogels, foams, topical formulations, wafers, transdermal patches, etc. The polymers like acrylic acid derivatives (eudragit), silicones derivatives, and poloxamers are used for formulating non-biodegradable hydrogel.67 However, non-biodegradable polymers have drawbacks like weak mechanical strength, low bio-adhesiveness, and inability to reduce external microbial infection at the site of wound. While designing non-biodegradable hydrogels, non-biodegradable polymers are coupled with biodegradable polymers to improve the bio-adhesiveness and mechanical strength. Such combination has displayed greater effectiveness and reduced allergic reaction at the site of the wound. Non-biodegradable hydrogels are advantageous in terms of the controlled release of the drug by acting as a supportive carrier at the site of the wound.68 Additionally, the non-biodegradable hydrogels change their porosity and mechanical strength after the addition of a release-specific chemical with the polymeric supporting carrier. The main mechanism of release-specific agent is to convert nonporous non-biodegradable polymer to porous non-biodegradable polymer and trigger the release of the drug at the site of action.69 Several research studies involving fabrication and evaluation of non-biodegradable hydrogels for chronic wound treatment are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Recently Developed Non-biodegradable Polymeric Hydrogel for Chronic Wound Management.

| Name of Polymer | Name of Drug/Wound Healing Agents | Description | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) | Gabapentin | A composite of soy protein isolate (SPI) and poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) hydrogel incorporated with gabapentin was formulated. SPI was attached covalently on PET fabric, for which graft polymerization of acrylic acid was done and then the carboxyl groups on acrylic acid were activated via EDAC; thereafter SPI was coated on the PET surface. In vitro cell culture performed on NIH 3T3 mouse fibroblasts revealed the composite to be biocompatible with no cell cytotoxicity. | (70) |

| Bacterial nanocellulose/acrylic acid | Human dermal fibroblasts | A nonbiodegradable hydrogel comprising bacterial cellulose and acrylic acid (BNC/AA) loaded with human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) was developed. It was established that >50% HDFs could be transferred successfully within 24 h onto the wound site. The hydrogel with HDFs unveiled faster wound healing in the gene and protein study. | (71) |

| Polyurethane (PU) | Curcumin | A hybrid hydrogel using polyethylene glycol-based Fmoc-FF peptide and polyurethane was synthesized in which curcumin was encapsulated via self-assembly with Fmoc-FF peptide by π–π stacking. This approach improved the loading of curcumin to as high as 3.3 wt % and also provided its sustained release. Further, curcumin loading into the hydrogel also improved its mechanical properties from 4 to 10 kPa, which is similar to natural tissues. Also, the hydrogel was injectable and had self-healing property. The in vivo results represented improved cutaneous wound healing in full-thickness skin defected model. | (72) |

| Poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(propylene sulfide) | Vemurafenib | A star-shaped amphiphilic block copolymer comprising poly(propylene sulfide) and poly(ethylene glycol) was utilized to develop vemurafenib loaded hydrogel. The amphiphilic polymer forms a physically stable hydrogel and efficiently dissolve the hydrophobic drug (vemurafenib) at therapeutic doses. The star-shaped polymer delivered the hydrophobic drug and also supported cell growth at the wound site, reduced inflammation, and promoted the wound closure. | (73) |

| Polyurethane-poly(acrylamide) (PU–PAAm) | A self-adhesive and mechanically flexible PU–PAAm hydrogel was developed to overcome the drawbacks of commercial hydrogel dressings such as lack of flexibility and adhesiveness. The PU plays a bridging role, which enhances IPN formation between physically cross-linked PU with chemically cross-linked PAAm network. A superior ductility and stretchability were endowed by the IPN hydrogel. The animal study confirmed high biocompatibility and tissue regeneration capacity of the developed hydrogel. | (74) | |

| Polyurethane-poly(vinyl alcohol) (PU–PVA)/layered double-hydroxide nanocomposite hydrogel | Enoxacin | A stretchable and biocompatible double-carrier drug delivery system for wound healing was developed. Mg–Al layered double hydroxide (LDH) was loaded with enoxacin, and then the LDH–enoxacin nanoparticles were prepared and incorporated into a PU–PVA network to fabricate a double-carrier drug delivery system. The mechanical properties and biocompatibility of PU–PVA hydrogel significantly improved due to incorporation of LDH–enoxacin nanoparticles in the hydrogel. | (75) |

4.2. Types of Hydrogels Based on Hydrogel Network Composition

Based on the gel network composition, hydrogels can be categorized into three different categories: (1) monopolymeric hydrogel; (2) copolymeric hydrogel; (3) interpenetrating network (IPN).

4.2.1. Monopolymeric Hydrogel

Monopolymeric hydrogel is a polymeric network derived from cross-linking of a single species of monomer. The hydrogels structural framework is generally dependent on the monomer type, polymerization method, and cross-linking agent utilized for hydrogel synthesis. Pectin, a natural heterosaccharide found in a plant cell wall, has been utilized for several biomedical applications such as scaffolding, delivery of active moieties, and skin protection. Thus, utilizing positive wound healing properties of pectin with procaine as a local anesthetic agent, Rodoplu et al. formulated the procaine impregnated pectin hydrogel for augmenting wound healing. The hydrogel was designed by employing the cross-linking approach (calcium chloride–cross-linking agent and glycerol–plasticizer). The optimized formulation displayed the release of procaine because of optimum swelling of pectin-based hydrogels. Also, the controlled release of procaine was observed due to the electrostatic interaction between the negatively charged groups present in the pectin chain and positively charged amine groups present in procaine. In vitro analysis of the formulation represented the wound healing ability on PCS-202-012 human dermal fibroblasts cells.76 Synthetic polymer, poly(vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP) is extensively utilized for the designing of various formulations as it has various applications in terms of cosmetics, biomedicine, and pharmaceuticals. Several studies have reported that the addition of PVP during formulation of hydrogel improved its swelling properties, gelling properties, and water absorption capacity. Singh and Kumar formulated dietary fibers moringa impregnated poly(vinylpyrrolidone) containing hydrogel by using chemically induced free radical polymerization using ammonium persulfate as an initiator and N,N′-MBA as cross-linking agent. The characterization of the formulation confirmed the formation of a three-dimensional network at the site of application. The in vitro analysis of the formulation confirmed the optimum biocompatibility, antioxidant effect, and mucoadhesive.77 Generally, single-monomer-based hydrogels (i.e., monopolymeric hydrogels) are unable to fulfill the necessities such as desired mechanical strength and good swelling properties for wound healing applications. Hence, multicomponent hydrogels are required for attaining the desired characteristics required for promoting wound healing.

4.2.2. Copolymeric Hydrogel

Copolymeric hydrogel comprises two different monomers where at least one monomer is hydrophilic. The hydrophilic monomer is necessary for providing hydrogels with optimum swelling. The synthesis of hydrogel is usually done by cross-linking of the monomers or polymerization technique. Block copolymer hydrogel, graft copolymer hydrogel, and random or alternating copolymer hydrogel are the types of copolymeric hydrogels divided on the basis of their structures. Marroquin-Garcia et al. developed lidocaine hydrochloride monohydrate and diclofenac sodium containing polyphosphate-based hydrogel as a wound dressing. The hydrogel was designed by implementing a free radical polymerization approach between bis[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl]phosphate and (3-acrylamidopropyl) trimethylammonium chloride solution or 2-acrylamido-2-methyl-1-propanesulfonic acid. The optimized formulation displayed 1000-fold increase in mechanical properties in comparison to previously reported materials. In vitro cytocompatibility testing of the hydrogel displayed more than 70% cell viability, which fulfilled the need of “ISO-10993-5” cytotoxicity cutoff guidelines. Furthermore, the in vitro drug release test also confirmed the controlled and prolonged release of both anti-inflammatory drugs. The hydrogel represented good enzymatic and hydrolytic stability, drug release, and cytocompatibility with bovine fibroblasts in wound-like pH conditions.78

4.2.3. Interpenetrating Network (IPN)

The IPN hydrogels are fabricated by addition of monomers and initiators to a prepolymerized hydrogel. A full-IPN comprises intertwined two polymer networks fabricated via addition of a cross-linking agent. As compared to conventional hydrogel, an IPN hydrogel provides benefits of controlled swelling, high mechanical strength, higher control over physical characteristics, and improved drug loading. By optimizing the surface chemistry and the pore size of the IPN, the release of an active moiety can be modified. Ng. et al. designed gellan gum–collagen IPN hydrogel as a dressing for wound healing. The gellan gum–collagen-based IPN hydrogel was fabricated to deliver adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) at the site of the wound for enhancing cell migration, regulating inflammation, and promoting wound closure. The optimized hydrogel expressed optimum mechanical strength and bio-adhesiveness at the site of the wound. The result of the SEM study confirmed the formation of a strong interpenetrating network (IPN) of gellan gum–collagen. The results of the 2D scratch assay and ELISA test demonstrated promotion of human dermal fibroblast migration and secretion of anti-inflammatory paracrine factor, i.e., TSG-6 proteins. In vivo application of the designed dosage form on full-thickness burn wound confirmed the complete wound closure and regeneration of tissue.53 By utilizing a chemical cross-linking approach and using both natural and synthetic polymers, such as tragacanth gum, poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate, and poly(vinyl alcohol) for the therapy of wounds, Hemmatgir et al. produced a unique interpenetrating hydrogel network. The in vitro characterization of the formulation demonstrated the optimum water retention, improvement in swelling, biocompatibility, bio-adhesiveness, and antimicrobial effect.80

4.3. Types of Hydrogels Based on Cross-Linking

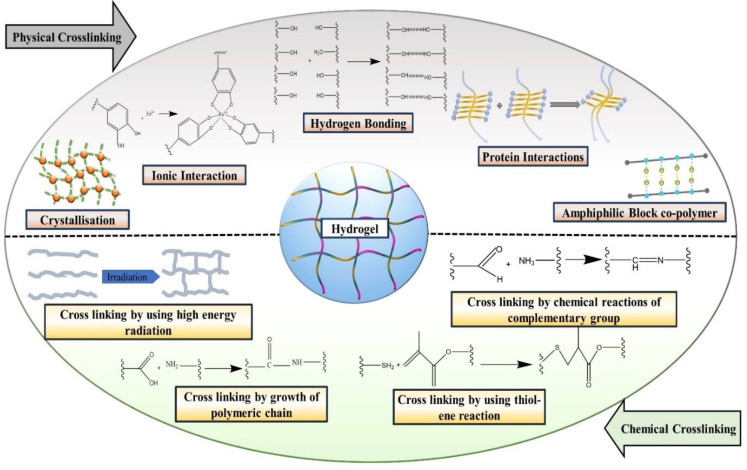

Based on the types of cross-linking, hydrogels are categorized into two distinct categories: (1) physical cross-linking and (2) chemical cross-linking. Various physical and chemical cross-linking mechanisms involved in hydrogel formation are schematically represented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of various physical and chemical cross-linking mechanisms for formation of hydrogel.

4.3.1. Physical Cross-Linking

Utilizing a physical cross-linking approach, the hydrogel can be designed by implementing various mechanisms, such as hydrogen bonding, molecular entanglement, ionic interactions between polymeric chains, etc.81 The physical cross-linkings between distinct polymers and polymeric chains have been proposed by a number of thermodynamical changes, including heating and/or cooling of the polymeric solution, lyophilization, lowering and/or increasing of pH, and appropriate choice of anionic and cationic polymers.82 Designing of the physically cross-linked hydrogel includes the simple procedure of purification as there is no involvement of any kind of chemically toxic cross-linking agents. Thus, these hydrogels are a very good platform for wound healing due to their biocompatibility and nontoxicity. It also becomes an ideal matrix for sustained release of a therapeutic agent at the site of the wound.83 ur Rehman et al. formulated reduced graphene oxide laden gelatin–methacryloyl (GeIMA) hydrogel for the management of nonhealing wounds. Hydrogels having different concentrations of reduced graphene oxide were formulated by implementing an ultraviolet (UV) cross-linking approach. The resultant formulation depicted optimum porosity and exudate absorbing capability. In vitro analysis of optimized formulation displayed optimum biocompatibility on three different cell lines, viz., EA. Hy926 endothelial cells, 3T3 fibroblasts, and HaCaT keratinocytes. The results of MTT assay and wound healing scratch assay also confirmed the migration and proliferation of cells. In vivo experiment on chick embryo model exhibited significant enhancement of the angiogenesis process during wound healing.84

Hydrogels prepared by the physical cross-linking method are further categorized into five different categories: (1) ionic interaction; (2) crystallization; (3) hydrogen bonding between the chains of polymers; (4) amphiphilic block copolymers; (5) protein interaction.

4.3.1.1. Ionic Interaction

The hydrogels are designed by using ionic polymers, cross-linked with their charged functional group. Anionic polymers are mixed with cationic polymers by the electrolyte complexation process to form hydrogels. This step is also known as the “complex coacervation”. Polymers such as alginate and pectin were utilized for the preparation of hydrogel by using this method.85

Liu et al. developed an ionic liquid-based hydrogel combined with an electrical stimulation approach for the management of diabetic wound. Over many years, it has been observed that the electrical stimulation is widely utilized for the skin regeneration as an attractive and important emerging therapy. A group of scientists designed a conductive multifunctional hydrogel composed of an ionic liquid (1-vinyl-3-butylimidazolium bromide) polymeric network and a polyvinyl alcohol–borax dynamic borate network) combined with an exogeneous electrical stimulation. The resultant optimized formulation displayed optimum mechanical properties which triggered the hydrogel to cover the entire wound without causing any damage. With the presence of ionic liquid and electrical stimulation, the formulation was able to promote cell proliferation, migration, angiogenesis, and collagen deposition. Due to this, the healing period of the wound and the rate of inflammation were significantly increased and decreased, respectively.86

4.3.1.2. Crystallization

Hydrogels are designed by the freeze–thaw process to deliver the medicament in crystal form (hydrophobic drugs). In brief, freezing water of an aqueous polymeric solution results in phase separation and formation of microcrystals during the freeze–thawing process. The repeated cycles of freeze–thawing trigger the reinforcement of preformed crystals with their structure and give extremely high stability and crystallinity.87 Poly(vinyl alcohol)/dextran aldehyde-based hydrogel was designed by Zheng et al. for efficient wound healing. Poly(vinyl alcohol)/dextran aldehyde-based hydrogel was prepared by mixing the solution of both polymers followed by freeze–thawing and freeze–drying. The hydrogel was evaluated and found to have a three-dimensional network, porous structure, strong tensile strength, maximum biocompatibility, and the ability to maintain a moist environment at the wound site. In vivo study of a prepared dosage form displayed no cytotoxicity and healed the wound within a week. The histopathological examination of the wound resulted in no significant difference in the groups. But the group treated with cotton gauze contained more inflammatory cells as compared to the groups treated with prepared dosage form and reference product (marketed product). The group treated with hydrogel displayed a consistent arrangement of epithelial cells and connective tissue with fibroblast cells.88

4.3.1.3. Hydrogen Bonding between the Chains of Polymers

The hydrogels in this category are developed by decreasing the pH of the polymeric solution and creating the hydrogen between the chains of two different polymers. It becomes relatively simple to lower the pH of the solution if the structure of polymer contains a carboxylic group. Low solubility of the polymer at acidic pH improves hydrogen bonding between the chains of polymer during hydrogel formulation.89 Hydrogel having qualities including self-healing, injectablity, and pH-sensitivity was studied by Ding et al. for the treatment of wounds. Briefly stated, a group of authors formulated a hydrogel using the dynamic bonds found in the amino groups of collagens, chitosan, and dialdehyde terminated poly(ethylene glycol). The optimized hydrogel exhibited better thermal stability, injectability, pH-sensitivity, hemostatic capacity, and wound healing. The hemostatic capacity of the hydrogel was determined by producing the hemorrhage in the liver of the mouse.90

4.3.1.4. Amphiphilic Block Copolymers

Under this category, the hydrogels are designed by using two blocks of homopolymer but chemically different, in which one polymer is hydrophobic and another one is hydrophilic in nature. Because of the thermodynamic incompatibility of individual polymer, it has the ability to self-assemble with another polymer in aqueous conditions during the formulation of hydrogels. This approach is most suitable for both types of drugs, i.e., lipophilic and hydrophilic. Moreover, the sustained release of the drug is also possible with this approach. An injectable thermosensitive penta-block copolymer and star-shaped copolymer hydrogels were designed by using the ring-opening polymerization method. In the biocompatible and biodegradable penta-block copolymer poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone)-b-poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm-PCL-PEG-PCL-PNIPAAm) is formulated by following three different steps: (1) formation of PCL-PEG-PCL triblock copolymer by bulk-ring-opening polymerization; (2) macroinitiator (Br-PCL-PEG-PCL-Br) for atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP), produced by esterification of the terminal hydroxyl groups of PCL with 2-bromoisobutyryl bromide; (3) ATRP, employing N-isopropylacrylamide, using difunctional PEG-(PCL-Br)2, as macroinitiator. The star-shaped hydrogel was also formulated by following three different steps: (1) designing of C-[P(CL-CO-LA)OH] by implementing the ring-opening polymerization method; (2) formation of PEG(CO2H)2; (3) coupling of steps 1 and 2. Both formulations depicted the greater biocompatibility, thermosensitivity, injectability, and porous three-dimensional structure to trigger the functioning of ECM. The result of in vivo experiment demonstrated the significant difference of cell proliferation phase between both formulations and control group after 11 days of treatment. Furthermore, the in vitro phase contrast microscopy analysis confirmed the upregulation of collagen types-I and -III.91

4.3.1.5. Protein Interaction

In this category, the designing of hydrogel is possible by doing some modifications in the chemical structure of recombinant protein and peptide molecules. In addition to obtaining the desired physical, chemical, and biological properties of the protein molecule containing hydrogel, the protein molecule must be cross-linked with the chain of polymer present in the hydrogel. Furthermore, the hydrogels are also prepared by the interaction of the protein molecule and/or accumulation of polypeptides by implementing a phase transition approach. Such types of hydrogels have enough potential for the management of the wound healing process. The diabetic wound ulcer is a quite challenging condition in the diabetic patient. Factors like polymicrobial infections and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are responsible for delayed wound healing in diabetic patients. Hence, to manage the diabetic wound, Sonamuthu et al. created MMP-9 sensitive dipeptide tempted natural protein hydrogel-based dressings by using dipeptides like l-carnosine. curcumin loaded silk protein hydrogel was prepared by the cross-linking method. The in vitro study of the prepared formulation resulted in significant human cell compatibility and acceleration of diabetic wound healing. The activation of the designed dosage form resulted in the inactivation of MMP-9 via its chelating effect of zinc ions present in the MMP-9 active center. The in vivo study on the mice model confirmed the inactivation of MMP-9 and inhibition of bacterial growth.92

4.3.2. Chemical Cross-Linking

Utilizing hydrogel for its biomedical applications, the chemical reaction between the components of the hydrogel must be unreactive in nature toward the cell and/or other biological moieties. Various chemical cross-linking reaction-based approaches, such as high energy radiations, growth of polymeric chain, and addition of polymers are utilized for the designing of chemically cross-linked hydrogel.

4.3.2.1. Cross-Linking by Growth of Polymeric Chain

The growth of the polymeric chain comprises three various points, i.e., initiation, progression, and termination. The previously formed free radicals in the reaction begin the polymerization followed by the progression of the chain due to the addition of a low molecular weight monomer. The progressed chains are intermittently cross-linked by the suitable cross-linking agent to form hydrogel.93 Wang et al. developed H2O2 activated in situ polymerization of aniline derivative hydrogel for the management and real-time monitoring of wound bacterial infection. In brief, a polymerizable aniline dimer derivative (N-(3-sulfopropyl) p-aminodiphenylamine) was polymerized in situ into polySPA in calcium alginate hydrogel. This step was initiated by the catalysis of hydrogen peroxide to produce hydroxyl radical by preloaded horseradish peroxidase. The NIR absorption of polySPA provides the benefit of real-time monitoring of H2O2 via photoacoustic signal and naked eye. It also provides the advantage of photothermal inhibition of bacteria via NIR light. Evaluation of the formulation represented more than 95% of the wound healing rate after the 11th day of treatment.94

4.3.2.2. Cross-Linking by Chemical Reaction of Complementary Groups

The presence of functional groups like COOH, OH, and NH2 in hydrophilic polymers is specially utilized for the formation of a hydrogel. These functional groups have the capacity to generate covalent linkage between the polymer chains involved in the production of hydrogel through reactions such as amine–carboxylic acid, isocyanate–OH/NH2 reaction, or Schiff base creation.95 Ou et al. developed graphene oxide containing conductive hydrogel having immunomodulatory action for the management of chronic infected diabetic wound. The hydrogel was formulated by employing Schiff base reaction and electrostatic interaction between oxidized hyaluronic acid, N-carboxyethyl chitosan, graphene oxide, and polymyxin B. In vivo analysis of optimized formulation exhibited significant anti-inflammatory effect, advancement of neovascularization process, and thereby acceleration of the healing of a diabetic wound. Moreover, it was also found that the optimized hydrogel formulation elevated the transformation of macrophages form pro-inflammatory phenotype (M1) to anti-inflammatory phenotype (M2). This resulted in the improvement of the local inflammatory microenvironment (downregulation of inflammatory cytokines) and upregulated the anti-inflammatory cytokines, which accelerated the diabetic wound healing process.96 A dual-dynamic-bond cross-linking of ferric iron, protocatechualdehyde, quaternized chitosan, and Schiff’s reaction based smart hydrogel was designed and evaluated by Liang et al., which had a range of useful properties including injectability, self-healing, biocompatibility, excellent antibacterial activity, antioxidant capacity, and the ability to be removed on demand. The formulation was demonstrated to be effective in the closing of a wound and speeding up of the healing process of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus, MRSA) infected full-thickness wound. In vivo study of NIR responsive hydrogel on skin incision model and MRSA infected full-thickness skin wound model displayed that the formulation was highly effective in closing wounds and provided postwound care. The histopathological study confirmed the low infiltration of inflammatory cells and further migration of fibroblasts after the 7th day of treatment. On the 21st day, it was confirmed that the process of re-epithelialization and healing of wound had completed. This result also indicated that the formulation had great potential to deal with various chronic wounds.97 Schiff’s base and phenylboronate ester were cross-linked to formulate insulin and live cells (fibroblasts-L929 cells) encapsulated as well as pH and glucose dual-responsive injectable hydrogel by Zhao et al. In detail, a group of researchers designed hydrogel by using phenylboronic modified chitosan, poly(vinyl alcohol), and benzaldehyde-capped poly(ethylene glycol), which can cohold insulin and live cells and release them in a sustained manner in response to changes in pH and glucose levels. The in vivo result of the optimized formulation exhibited the optimum support for the growth of new blood vessels, collagen formation, and healing of diabetic wound in streptozotocin induced diabetic rat model.98

4.3.2.3. Cross-Linking by Using High-Energy Radiations

This approach is widely utilized for the formation of hydrogels as there is no requirement for toxic chemicals for cross-linking and separate sterilization. When polymers are exposed to high-energy radiation, radicals are generated. These radicals are generated on the polymeric chain in the aqueous solution of polymers which mimics the free radical polymerization. Recombination of these free radicals on various chains of polymers results in the formation of covalently cross-linked hydrogels.99 Pang et al. developed an in situ photo-cross-linked hydrogel for diabetic wound healing. In brief, a formulation containing methacryloxylated silk fibroin (SF-MA) and methacyloxylated borosilicate (BS-MA) was synthesized initially. Thereafter, via covalent bonding among methacryloyloxy (MA) groups, under UV radiation, SF-MA-BS hydrogel was formed. The optimized formulation exhibited optimum adhesiveness, improved mechanical properties, and excellent bioactivity. The hydrogel had an in situ photo-cross-linking potential that resulted in formation of an SF-MA-BS hydrogel, which bonded with the wound and thereby inhibited bacterial growth and adhesion via release of copper ions. It also stabilized the hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α (HIF-1a) via SF-MA-BS and wound tissue interaction and thereby enhanced angiogenesis. The formulation also reduced the rate of inflammation by depleting the expression of inflammation related factors and enhancing anti-inflammatory agents secretion.100

4.3.2.4. Cross-Linking by Thiol–Ene Click Reaction

The reaction of thiols (nucleophile) is the fundamental prerequisite for designing a hydrogel in order to obtain the required biological characteristics, quick action, and controlled release of the medication. The mechanism of the reaction can either be the radical-mediated thiol–ene reaction or the thiol Michael click reaction by determining the functional groups and reaction conditions. Park et al. developed a blue light induced thiol–ene reaction based hyaluronic acid containing hydrogel for the treatment of a corneal alkali burn wound. The optimized formulation exhibited optimum mechanical strength and transparency at the site of application. The in vivo study of the formulation demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effects and proliferation and migration of epithelial cells and fibroblasts in a corneal burn wound rabbit model. Histopathological analysis of the healed area confirmed the optimum thickness of collagen, reduction in inflammatory cells, and neovascularization.101

5. Marketed Products

The complex process of healing a wound includes the regeneration of tissue layers. A variety of cell populations, growth factors, and varied regulating molecules and pathways are involved to achieve complete wound healing. Due to various properties, like maintaining a high moisture content at the site of the wound; parallelly allowing gas exchange between the wound and the external environment, significant biocompatibility, and quick biological fluid absorption (wound exudate); and providing a cooling effect that lowers the temperature at the site of the wound, the hydrogel has attracted commercial interest in wound management. To choose the material efficient for wound care and healing, it is crucial to ascertain the particular needs of the injured portion. Some of the marketed hydrogels widely utilized for wound management will be briefly discussed in this section. NU-GEL–hydrogel is a sodium alginate containing hydroactive amorphous gel developed by 3M KCI. It functions by effectively desloughing and debriding the wounds. It creates a moist environment and also provides autolytic debridement. The alginate improves its absorption capacity. 3M Tegaderm is a hydrogel wound filler that is preservative-free, sterile, amorphous, and easy to apply. It is beneficial for minimally or nondraining, full- or partial-thickness wounds including pressure ulcers, arterial ulcers, venous ulcers, diabetic ulcers, cavity wounds, etc. It is composed of guar gum, propylene glycol, sodium tetraborate, and water. Eurocell hydro, developed by Eurofarm Advanced Medical Devices, is a comfortable, wet, and highly absorbent wound dressing composed of carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC). A crystal-clear gel is formed when CMC comes in contact with the wound exudates, also provides a moist environment, and also aids in removing nonviable tissues from the wound. It is beneficial to heal traumatic wounds, leg ulcers, diabetic ulcers, partial- and superficial-thickness burns, cavity wounds, etc. Several other marketed hydrogels widely employed to treat different types of wounds are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Hydrogels Marketed for the Management of Chronic Wounds.

| Name of Marketed Products | Name of Manufacturer | Composition | Product Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suprasorb G | Lohmann & Rauscher | Polyethylene, acrylic polymer derivatives, phenoxyethanol | • Dry wounds, wounds with less exudate, pressure ulcers, first- and second-degree burn wound management |

| • Easy to mold according to shape and size of the wound | |||

| AquaDerm | DermaRite | Acrylic polymer derivatives, propylene glycol, 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone | • Suitable for nontraumatic wounds |

| • Ability to absorb exudates and provide a moist environment at the site of wound | |||

| DermaGauze | DermaRite | Polyethylene, Vitamin E | • Utilized as a primary dressing for partial and/or full-thickness wound |

| • Removes necrotic tissue and makes eschar soft | |||

| DermaSyn Ag | DermaRite | Silver, poly(propylene glycol) | • Management of first- and second-degree burns |

| • Pressure ulcers | |||

| • Diabetic ulcers | |||

| DermaSyn | DermaRite | Vitamin E, poly(propylene glycol) | • Provides moisture to dry wounds |

| • Promotes development of cell and autolytic debridement | |||

| Neoheal | Kikgel | Poly(vinylpyrrolidone), poly(ethylene glycol), agar | • Ability to absorb exudates along with bacteria |

| • Exhibit optimum moist environment at the site of wound | |||

| Restore Hydrogel | Hollister Wound Care | Hyaluronic acid | • Ability to cover secondary dressing |

| • Provide moist environment at the site of wound for 24–72 h | |||

| ActivHeal Hydrogel | ActivHeal | Water | • Provides moisture environment internally at the site of wound and removes debridement. |

| • Utilized as primary dressing for dry wounds, pressure ulcers, and diabetic ulcers. | |||

| Purilon | Coloplast | Sodium carboxy methyl cellulose, sodium alginate | • Management of dry wounds |

| • Combinedly used with secondary dressing for the management of first- and second-degree burns | |||

| INTRASITE Gel | Smith and Nephew | Purified water | • Rehydration of wound |

| • Triggers the migration of epithelial cell | |||

| • Prevents scar formation | |||

| SOLOSITE Gel | Smith and Nephew | • Utilized for the management of burns, cuts, venous ulcers, pressure ulcers (Stage-IV) | |

| • Cost-effective | |||

| • Exhibit moist environment to fragile granulation tissue | |||

| Wound’Dres | Coloplast | Collagen | • Ability to improve the rate of moisture permeation at the site of wound |

| • Require secondary dressing for infected wounds | |||

| Kendall Amorphous Hydrogel | Cardinal Health | Glycerin | • Extensively utilized for the management of Stage II–IV pressure ulcers, first- and second-degree burns |

| Cardinal Health Hydrogel | Cardinal Health | Silver | • Create effective barrier for the penetration of bacteria which produces the inhibitory action of microorganisms, encounters the gel |

| • Utilized for the management of pressure ulcers, postoperative incisions, first- and second-degree burns, abrasions, skin irritations | |||

| Kendall Hydrogel Impregnated Gauze | Cardinal Health | • Contains gauze sponge | |

| • Having longer dressing wear times | |||

| Kendall Hydrogel Wound Dressings | Cardinal Health | • Unique disc-shaped product: i.e., covers the whole wound and helps to fill the void cavities | |

| • Translucent appearance | |||

| • Easy to visualize the wound and improvement in wound healing process | |||

| Tegagel Hydrogel Wound Filler— Sterile | Flagship Medical | • Fills the voids in wound | |

| • Provides moist environment at the site of wound | |||

| • Stimulates autolytic debridement | |||

| Algosteril | Laboratories BROTHEIR | • Expresses the exchange of calcium ions with sodium ions in the blood and absorb exudate | |

| • Releases calcium ions, activating the cell involved in hemostasis and ensuring rapid wound healing | |||

| Stimulen collagen gel | Southwest Technologies | Collagen | • Used to fill voids in wound cavity |

| • Nontoxic and nonirritant |

6. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Chronic wounds inflict an enormous socio-economic burden and, if they fail to respond to the available therapeutic interventions, may result in amputation, leading to serious physical trauma and emotional suffering to the patients. Although a plethora of wound dressings are available in market, there is a dire need to develop improved advanced wound dressings due to increased incidences of chronic diseases and an aging population. Hydrogels’ integral characteristics such as their excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, good water retention capabilities, tunable functionalities, ability to provide a cooling effect on a wound surface, and capacity to absorb excess exudates makes them a suitable dressing to accelerate wound healing. Hydrogels have been extensively utilized as wound dressings as they are easy to fabricate, functionalize, and modify. Hydrogels are formulated by employing natural or synthetic polymers, and they can be loaded with discrete bioactives that could facilitate wound healing. Numerous stages are involved in the dynamic process of wound healing, wherein an individual stage includes a combined action of multiple factors and cells for promoting tissue regeneration.102 This review gave an outlook regarding the types of hydrogels based on different criteria and their influence on the hydrogel’s characteristics such as its mechanical properties, swelling properties, rheological properties, etc. Recently, there have been novel attempts of integrating electronic components to hydrogels for capturing the changes at a wound site and permitting a more comprehensive and accurate monitoring of the wound healing process.103,3 Hydrogels having integrated therapeutic and monitoring functions will be an emerging arena in the future. Moreover, to meet the requirements of different wound types, microneedle-like hydrogels are also an emerging category that renders a varied topological surface profile.104 Hydrogels are available in the market in different forms, such as injectable gels, films, sprayable gels, etc. Several studies have indicated growing interest in fabricating in situ nanocomposite hydrogels for wound healing applications. Hydrogels offer stimuli-responsive or sustained delivery of antibiotics, antimicrobials, or anti-inflammatory agents, signifying a promising approach for targeting highly infected wounds with greater efficacy.105

However, involving several activities in a single wound dressing makes the regulatory and validation process more complex. Also, before smart hydrogels can be adopted routinely as delivery platforms for pharmacological agents, their clinical investigations are essential. Recent techniques of physical and chemical cross-linking such as amphiphilic block copolymers, crystallization, click chemistry, enzymatic reactions, etc. have expanded the scope of hydrogels’ applicability. The hydrogel’s future will move toward more specificity and lower costs. Attaining more effect on each phase of chronic wounds remains the key focus for forthcoming research. Some of the factors that are necessary to be optimized during hydrogel production are polymers solubility, stability, processability, and cross-linking materials. Bringing expertise from different fields, such as materials and biomedical engineering, chemistry, pharmacy, physics, etc., together to solve the current issues can be beneficial to improvise hydrogel as wound dressings.106

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Nirma University, Ahmedabad, India for providing the required assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. Ms. Dhruvi Solanki is also grateful to the Government of Gujarat for providing a fellowship under the SHODH scheme.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Zeng D.; Shen S.; Fan D. Molecular design, synthesis strategies and recent advances of hydrogels for wound dressing applications. Chinese J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 30, 308–20. 10.1016/j.cjche.2020.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]