Abstract

Background

Health education interventions are considered critical for the prevention and management of conditions of public health concern. Although the burden of these conditions is often greatest in socio-economically disadvantaged populations, the effectiveness of interventions that target these groups is unknown. We aimed to identify and synthesize evidence of the effectiveness of health-related educational interventions in adult disadvantaged populations.

Methods

We pre-registered the study on Open Science Framework https://osf.io/ek5yg/. We searched Medline, Embase, Emcare, and the Cochrane Register from inception to 5/04/2022 to identify studies evaluating the effectiveness of health-related educational interventions delivered to adults in socio-economically disadvantaged populations. Our primary outcome was health related behaviour and our secondary outcome was a relevant biomarker. Two reviewers screened studies, extracted data and evaluated risk of bias. Our synthesis strategy involved random-effects meta-analyses and vote-counting.

Results

We identified 8618 unique records, 96 met our criteria for inclusion – involving more than 57,000 participants from 22 countries. All studies had high or unclear risk of bias. For our primary outcome of behaviour, meta-analyses found a standardised mean effect of education on physical activity of 0.05 (95% confidence interval (CI) = -0.09–0.19), (5 studies, n = 1330) and on cancer screening of 0.29 (95% CI = 0.05–0.52), (5 studies, n = 2388). Considerable statistical heterogeneity was present. Sixty-seven of 81 studies with behavioural outcomes had point estimates favouring the intervention (83% (95% CI = 73%-90%), p < 0.001); 21 of 28 studies with biomarker outcomes showed benefit (75% (95%CI = 56%-88%), p = 0.002). When effectiveness was determined based on conclusions in the included studies, 47% of interventions were effective on behavioural outcomes, and 27% on biomarkers.

Conclusions

Evidence does not demonstrate consistent, positive impacts of educational interventions on health behaviours or biomarkers in socio-economically disadvantaged populations. Continued investment in targeted approaches, coinciding with development of greater understanding of factors determining successful implementation and evaluation, are important to reduce inequalities in health.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-023-15329-z.

Keywords: Health education, Socio-economic disadvantage, Systematic review, Social determinants of health, Health promotion

Introduction

Health promotion and the prevention of ill-health via population and individual level interventions are key recommendations of the World Health Organization for the management of communicable and non-communicable diseases [1, 2]. Specific health education interventions are considered integral to system-wide public health strategies [3, 4]. Such educational interventions commonly aim to promote understanding about how behaviours impact health, and require individuals to have the capacity to acquire, understand and operationalize the content of health education in order to improve their health status [4, 5]. These capacities are influenced by the social and economic circumstances of individuals’ lives [6, 7].

Social and economic circumstances also importantly contribute to inequalities in health. This is depicted by the ‘social gradient’ in health, [8] whereby the lower a person’s socio-economic position, the poorer their health status. ‘Unhealthy’ behaviours associated with the development of chronic disease, such as smoking, poor diet, too little physical activity, and low engagement with preventative (e.g. screening) healthcare, are more prevalent among individuals who are socially or economically disadvantaged [9, 10]. Public health interventions to promote healthy behaviours may therefore be of most importance for these populations.

Socio-economically determined disparities in health outcomes can sometimes be further increased by behavioural health promotion initiatives, particularly those that are delivered across a large population. Benefit seems to be related to individuals’ access to social and economic resources and improvement is lowest in disadvantaged groups [10, 11]. For example, peoples abilities to respond to health promotion messages by changing health behaviours (such as improving diet and exercising regularly) vary widely – but changes are less likely to be adopted amonst low-income groups [10]. Similarly, technological interventions to improve health outcomes “work better for those who are already better off”(p. 1080), for reasons that stem from discrepancies in accessibility, adoption, and adherence [12]. Intensive, small-scale interventions targeted to high risk populations may be more likely to generate benefits, but economic and practical issues commonly limit broad implementation. Even the best-intentioned interventions frequently fail to reach, and to impact, those whose health needs are greatest.

Although specific educational interventions to improve health literacy and health-related behaviours are considered integral to public health interventions, little is known about the extent to which educational interventions that target disadvantaged populations are effective, nor about the intervention characteristics that are associated with success. Our principal objective was to identify and synthesize evidence of the effectiveness of health-related educational interventions in adult disadvantaged populations. Our primary outcome was health related behaviour, and our secondary outcome was a biomarker related to the health intervention. Our secondary objective was to summarise the characteristics of effective interventions.

Methods

We registered our full protocol a priori on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/ek5yg/). Our study is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement, [13, 14] the Checklist of Items for Reporting Equity-Focused Systematic Reviews (PRISMA-E 20,212 Checklist), [15] and the Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) [16] reporting guidelines. We deviated from the registered protocol by reconsidering our approach to addressing the secondary objective of this study and undertaking an additional vote-count analysis.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We developed a comprehensive search strategy with the assistance of a health librarian and systematically searched five electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, EMCARE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)) since inception to 20th May 2020 to identify eligible studies. We updated these searches on 5th April 2022. Studies were limited to those involving human participants and available in English. Details of the search strategies are provided in Appendix 1.

We searched for studies that assessed the effectiveness of any health-related educational intervention delivered to socio-economically disadvantaged adults in any country. We defined health according to the World Health Organization definition, as: “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [17]. We defined socio-economically disadvantaged adults as belonging to a socio-economically disadvantaged population, classified as: “an area, neighbourhood or community with residents clearly defined as disadvantaged, relative to the wider national population” [18] (p. 372). Socio-economic disadvantage could be defined by factors including (but not limited to) income, educational level, living standards, and minority grouping. To be eligible for inclusion, at least 75% of participants in the included studies were required to meet this definition of belonging to a socio-economically disadvantaged population and be aged 18 years or over.

Published, peer-reviewed experimental studies investigating the effectiveness of an educational intervention on health-related outcomes were considered for inclusion. Eligible designs included (but were not limited to): randomised controlled trials, quasi-randomised and cluster-randomised trials. We excluded studies that were not published in English, pilot studies, reviews, commentaries, and case study reports, studies that did not describe the study population sufficiently to enable classification as ‘socio-economically disadvantaged’, and studies that did not report at least one outcome of interest.

Interventions and outcomes

Studies included in this review must have evaluated the effectiveness of an educational intervention. Interventions were considered to be ‘educational’ if the authors described the intervention as having intent to ‘educate’ or ‘inform’. Studies evaluating an educational intervention as their main objective or as a component of a comprehensive intervention were eligible for inclusion. Individual, group, community or population-based health education interventions, delivered through any medium (e.g. face-to-face, telephone, text, online, mass media) were considered. Included studies needed to have compared the educational intervention to any type of intervention, placebo, or no-treatment control. The primary outcome was health-related behaviour, or actions that individuals take that affect their health [19]. All behavioural outcomes that were considered to be health related and related to the study intervention were regarded as relevant. The secondary outcome was any biomarker related to the health condition the intervention was targeting (e.g. body mass index (BMI) as a biomarker of weight loss; or Haemoglobin A1C as a biomarker of diabetes control).

Screening and data extraction

Identified studies were retrieved and exported into Endnote citation management software (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia), and then imported into Covidence systematic review management system (Veritas Health Innovation Limited, Australia). Duplicates were removed. Pairs of reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts for relevance according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (AG, CP, TA, LW and RS). The full texts of potentially eligible studies were obtained, the article further screened for eligibility and reasons for exclusion recorded. Any discrepancies or disagreements between the two reviewers were discussed. If agreement was not met, a third reviewer (EK) was consulted to provide opinion and a majority decision was made.

Pairs of reviewers independently extracted the relevant data from each study using a standardised and pilot-tested spreadsheet. The results were compared, discrepancies discussed, and a third reviewer was consulted to resolve disagreements if required. The data extraction template included the fields: study design, health ‘condition’, population characteristics (including reason for classification as socio-economically disadvantaged), participant characteristics, sample size, details of study intervention(s) and comparator, assessment time points, outcomes, and results.

Risk of bias assessment

Pairs of authors independently evaluated the risk of bias (ROB) for each study using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing ROB in randomised trials [20]. Six domains were evaluated: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and ‘other’ bias. We used the guideline provided by the Cochrane Handbook to assess each item as high, low or unclear ROB. A third reviewer was consulted to resolve any disagreements between the independent evaluations if required. Overall ROB was also assigned according to the Cochrane Handbook. Low overall ROB was assigned for studies where all key domains were low risk; unclear overall ROB was assigned when key domains were either low or unclear; and high overall ROB was assigned when one or more of the key domains were assigned a high ROB.

Data analysis

To address our primary aim – to identify and synthesize evidence of the effectiveness of health-related educational interventions in disadvantaged populations – we extracted effect sizes and precision estimates from the included studies where available. If an effect size was not reported we extracted the number of participants in each condition, the means and standard deviations of the observations (at the longest follow-up timepoint). We examined the clinical and methodological heterogeneity between the included studies to determine the appropriateness of combining the effect sizes to estimate an overall effect for our primary and secondary outcomes. To determine the appropriateness of data pooling we primarily considered homogeneity of outcomes, follow-up durations and comparison groups. In cases where studies were considered to be sufficiently (clinically and methodologically) homogenous for pooling, but data were missing, we contacted study authors to request the missing data. Authors were emailed, with a follow-up email sent two weeks later. In the case of no reply a further email was sent after another week, and if there was still no reply the data were not included. Random effects meta-analysis (DerSimonian and Laird model [21]) was conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (version 3We evaluated the quality of the evidence of the included studies and rated the certainty of recommendations using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework [22]. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of a funnel plot; Egger’s test was applied if there were 10 or more studies in the meta-analysis [23].

Since meta-analysis could only be performed on a proportion of the studies, we summarised the overall effectiveness of interventions for our primary and secondary outcomes using a vote-counting approach [20]. When studies specified a single primary outcome, we determined intervention benefit from that outcome. We classified ‘intervention benefit’ using a standardised binary metric assigned according to the observed direction of effect. This classification was based on the point estimate of effect, without consideration of statistical significance or the size of the effect. Studies with a point estimate of effect in favour of the intervention were counted as [1]; studies with a point estimate of effect in favour of the control were not counted. When studies had two or more outcomes, we applied a decision rule to identify a single outcome from which to classify intervention benefit (Appendix 2). We calculated the number of effects showing benefit as a proportion of the total number of studies and determined a confidence interval using the Agresti-Coull interval method recommended for large sample sizes [24]. We undertook a subsequent calculation in which we determined the proportion of effective interventions by classifying benefit (for the outcome of interest) according to the conclusions of the individual studies, rather than using the point estimate to indicate effect. This approach minimised the risk of an inflated vote-count result.

To address our secondary objective – to summarise the characteristics of effective interventions – we tabulated details of the intervention (setting, type, dose, description) in a format to facilitate reader interpretation. Classification of intervention dose [25] (as low, moderate, or high) considered intervention duration (in months), frequency (number of contacts), and amount (in hours) (see Appendix 3 for details). We aimed to provide a summary of the features of the effective interventions.

Role of the funding source

The funder of this study played no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Results

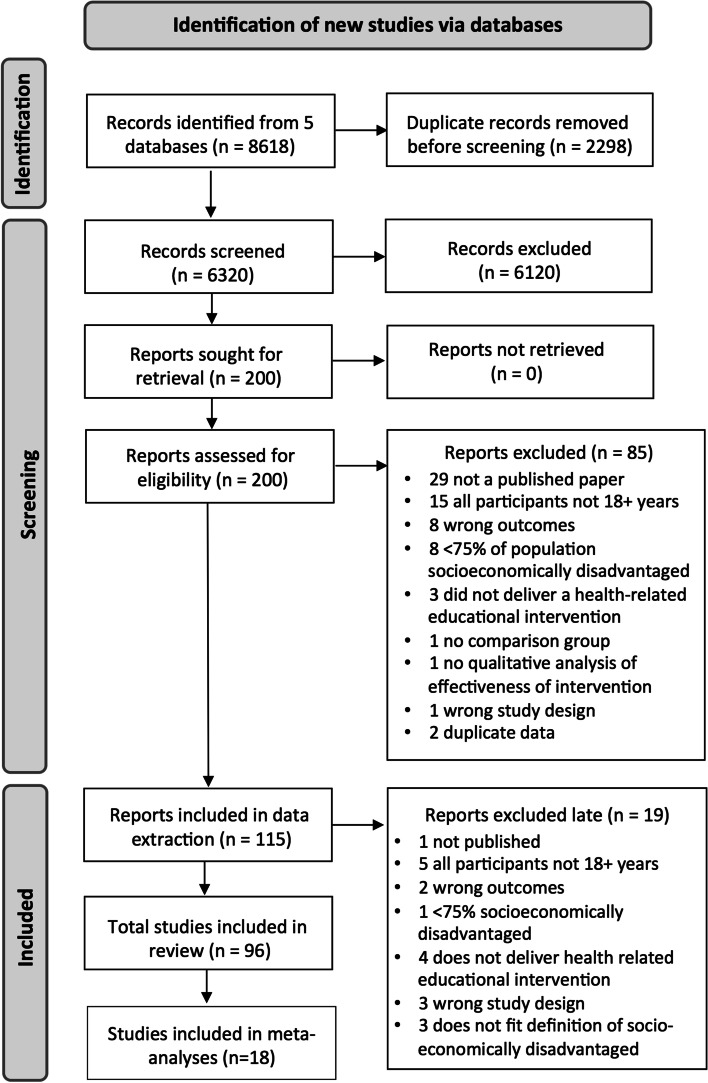

Our searches identified 8618 records; 200 full text articles were screened for eligibility; 96 studies were included (Fig. 1). Key characteristics of the included studies are provided in Tables 1 and 2. Eighty studies (83%) were undertaken in high-income countries; four studies (4%) were undertaken in upper-middle income countries; ten studies (10%) were undertaken in lower-middle income countries; and 3 studies (3%) were undertaken in low-income countries (see Tables 1 and 2). Seventy-seven (80%) of the included studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs); 12 were cluster RCTs (13%); 7 were quasi-experimental studies (7%). The educational interventions addressed a wide range of health issues. The most common education topics were parenting skills, pregnancy and newborn health, (14 studies each) cancer screening, multi-factorial healthy lifestyle interventions (11 studies each), diet (9 studies), smoking cessation (8 studies) and sexual health (5 studies). The total number of adult participants exceeded 57,000, residing in 22 different countries.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in Meta-analyses (n = 16)

| 1st Author (year), country | Study design No at baseline (No analysed) |

Country (Income level) | Population and setting | Focus of educational intervention | Comparison group | Relevant Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Brooking (2012) [53] |

RCT 84 (64) |

New Zealand (HIC) | Maori at risk of type 2 diabetes | Weight loss and nutrition education | Control group with delayed educational content | Weight, BMI, BP (2), cholesterol (2), triglycerides, blood glucose, blood insulin |

|

Byrd (2013) [32] |

RCT 613 (613) |

USA (HIC) | Women of Mexican origin from three diverse sites including a large urban centre and a rural farming community | Intervention to increase cervical cancer screening rates (3 intervention arms) | Usual care (offered intervention after completion) | Cervical cancer screening (1) |

|

Gathirua-Mwangi (2016) [33] |

RCT 244 (237) |

USA (HIC) | African American women eligible for a free mammogram | Breast cancer screening educational intervention | Usual care (may have received postcard reminder to schedule mammogram) | Mammography adherence |

|

Hovell (2008) [29] |

RCT 151 (138) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income, sedentary Latino women through a community-based clinic | Exercise and diet intervention involving education and aerobic dance | Control group—received information unrelated to exercise, diet or cardiovascular disease | Exercise (3), VO2 max, cholesterol (2) |

|

Katz (2007) [34] |

RCT 897 (775) |

USA (HIC) | White, African American and native American women living in a rural count through a rural community | Lay health advisor education program focused on mammography and the benefits of early detection of breast cancer | Control group received delayed intervention | Cervical cancer screening |

|

Keyserling (2008) [30] |

RCT 236 (212) |

USA (HIC) | Mid-life women attending a community health care centre serving low income, minority patients | Enhanced lifestyle intervention to improve physical activity and diet | Minimal intervention—single mail out of pamphlets on diet and physical activity | Physical activity (6), dietary risk assessment, carotenoid index, BP, cholesterol, weight |

|

Khare (2012) [27] |

RCT 833 (505) |

USA (HIC) | Disadvantaged, low-income, uninsured or underinsured women (English speaking) | Cardiovascular disease risk factor screening and education intervention plus a 12-week lifestyle change intervention | Minimal intervention—screening and education without lifestyle change intervention | Dietary intake (3), physical activity (2), BP, cholesterol, blood glucose, BMI |

|

Khare (2014) [28] |

RCT 180 (67) |

USA (HIC) | Disadvantaged, low-income, uninsured or underinsured women (Spanish speaking) | Cardiovascular disease risk factor screening and education intervention plus a 12-week lifestyle change intervention | Minimal intervention—screening and education without lifestyle change intervention | Physical activity (2), cholesterol (2), glucose, BMI |

|

Kim (2014) [54] |

RCT 440 (369) |

USA (HIC) | Korean American seniors with high blood pressure through community-based churches and senior centres | Community based self-help behavioural intervention to address high blood pressure | Control group—received a brochure that listed available community resources | BP (3) |

|

Kisioglu (2004) [55] |

RCT 430 (400) |

Turkey (UMIC) | Middle aged women of low socioeconomic status in the poor outskirts of the city | Blood pressure and obesity reduction intervention | Control group—no training | BMI, BP, physical activity (3) |

|

Kreuter (2005) [35] |

RCT 1227 (881) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income African American women through urban public health centres | Intervention promoting use of mammography and increased fruit and vegetable intake | Usual care | Mammogram, dietary intake |

|

Parra-Medina (2011) [31] |

RCT 266 (151) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income African American women at high risk for cardiovascular disease | Lifestyle intervention aimed to reduce dietary fat intake and increase moderate to vigorous physical activity | Standard care—behavioural counselling, assisted goal setting, educational materials | Physical activity (2), dietary intake |

|

Staten (2004) [56] |

RCT 326 (217) |

USA (HIC) | Uninsured, primarily Hispanic women over 50 in the community | General health education intervention (2 arms) | Low intensity intervention – diet and physical activity counselling, referral to education classes | BMI, waist to hip ratio, BP, blood glucose, cholesterol, triglyceride levels, physical activity |

|

Suhadi (2018) [57] |

Cluster RCT 190 (182) |

Indonesia (LMIC) | Low socioeconomic status, minority adults from 4 villages | Cardiovascular disease risk awareness and prevention intervention | Control group – monitoring of blood levels only | ASCVD risk, BP, BMI, blood sugar, cholesterol (2) |

|

Valdez (2016) [36] |

RCT 943 (727) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income, Latina women | Cervical cancer education program | Standard care – received brochure on gynaecological cancer | Cervical cancer screening |

|

Zoellner (2016) [26] |

RCT 301 (296) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income adults in 9 medically underserved rural regions | Intervention targeted decreasing sugar sweetened beverage consumption | Control—group based physical activity promotion intervention | Sugary drink intake, diet, physical activity (2), BMI, weight, cholesterol (3), triglycerides, glucose, BP (2) |

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies not included in Meta-analyses

| 1st Author (year), country | Study design No at baseline (No analysed) |

Country (Income level) | Population and setting | Focus of educational intervention | Comparison group | Relevant Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abiyu (2020) [58] |

Cluster RCT 612 mother-infant pairs (554) |

Ethiopia (LIC) | Mothers with infants < 6 months old residing in rural communities in Ethiopia | Feeding behaviour change intervention to improve infants’ feeding practices, health and growth | Usual care (routine health and nutrition services) | WHO dietary adequacy indicators (3), dietary intake (8) |

|

Acharya (2015) [59] |

Cluster RCT 12,368 (11,885) |

India (LMIC) | Community-dwelling pregnant women in Uttar Pradesh districts (high socioeconomic needs and low institutional delivery) | Pregnancy and Newborn Health – High intensity intervention | Low intensity intervention | Healthy delivery (5); breast feeding(4) |

|

Almabadi (2021) [60] |

RCT 579 (295) |

Australia (HIC) | Adults on a waiting list at an Oral Health Care Clinic in a low socio-economic community | Promoting improved oral health care via education about oral hygiene procedures, smoking and alcohol cessation, healthy diet | Routine oral health care | Smoking, alcohol, diet, BMI, blood makers (6), plaque index |

|

Alegria (2014) [61] |

RCT 724 (647) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income Latino and/or other minority patients of community mental health clinics; English and Spanish speaking | Teaching activation, self-management, engagement & retention in mental healthcare | Minimal intervention (received brochure) | Patient activation, self-management, service use, retention |

|

Alias (2021) [62] |

Quasi-experimental 390 (358) |

Spain (HIC) | Community dwelling older adults (≥ 60 years) living in urban disadvantaged areas who perceived their health as fair or poor | Aimed at promoting social support and participation, self-management and health literacy | Delayed intervention | Social participation; use of anxiolytics/antidepressants; use of health resources |

|

Alvarenga (2020) [63] |

RCT 56 (44) |

Brazil (UMIC) | Mother-infant dyads recruited from 2 health centres in 2 low-income communities | Infant development | Control intervention (monthly mailouts showing main developmental milestones) | Mother behaviours related to maternal sensitivity (6) |

|

Andrews (2016) [64] |

RCT 409 (373) |

USA (HIC) | Female smokers residing in government subsidized neighbourhoods in South Carolina | Smoking cessation intervention | Delayed intervention group | Smoking cessation (2) |

|

Annan (2017) [65] |

RCT 479 (479) |

Thailand (LMIC) | Burmese migrant parents or primary caregivers and their children residing in rural, peri-urban, or urban communities in Thailand | Parenting and family skills training program | Waiting list control condition | Child behaviour (3) |

|

Avila (1994) [37] |

RCT 44 (39) |

USA (HIC) | Obese, low-income Latina from a community medical clinic | Weight reduction program including exercise, nutrition education, behavioural modification strategies, and a buddy system | Control intervention—weekly cancer screening education sessions | Exercise frequency, BMI, cholesterol, blood glucose, BP, VO2 max |

| Bagner (2016) [66] |

RCT 60 families (46) |

USA (HIC) | Racial minority mothers and their 12–15-month-old infants living below the poverty line | Parenting intervention involving an Infant Behaviour Program | Standard paediatric care | Parent child interaction (2) |

| Baranowski (1990) [67] |

RCT 94 families (94) |

USA (HIC) | Black American families with children in 5th, 6th and 7th grade in community-based public or private school systems | Centre-based program to improve diet and increase aerobic activity | No intervention control group (no contact during the program) | Exercise (2), resting pulse rate, BP |

|

Barry (2022) [68] |

RCT 574 (364) |

USA (HIC) | English-speaking mother-infant dyads living in poverty in one of two major US cities | Positive parenting and healthy child development | Usual care | Child behaviour (4), continuous performance task |

|

Befort (2016) [69] |

RCT 172 (168) |

USA (HIC) | Postmenopausal female breast cancer survivors residing in rural areas through rural community cancer clinics | Diet and physical activity intervention (Phase 2—weight maintenance intervention) | Minimal intervention – mailout and phone calls covering the same educational content | Weight (4) |

|

Berman (1995) [70] |

Quasi-experimental 446 (118) |

USA (HIC) | Adult smokers who were parents of students or adult students from low to middle income, multi-ethnic, inner-city public-schools | Smoking cessation program | Control group—received health education material without smoking cessation information | Smoking cessation (4) |

|

Bray (2013) [71] |

Quasi-experimental 727 (727) |

USA (HIC) | Rural, low income, diabetic African Americans in rural, fee for service primary care practices | Diabetes self-management program involving education, self-management coaching and medication adjustment | Usual care—standard assessment and treatment, educational handouts offered | Haemoglobin, BP, lipid levels |

|

Brooks (2018) [72] |

Cluster RCT 331 (250) |

USA (HIC) | Smokers interested in quitting smoking from Boston public housing developments | Smoking cessation intervention | Standard care—smoking cessation materials and one visit from a Tobacco Treatment Advocate | Service use; smoking cessation (2) |

|

Brown (2013) [73] |

RCT 252 (109) |

USA (HIC) | Impoverished Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes in the community | Culturally tailored diabetes self-management education intervention | Waiting list control | Leptin, A1C, BMI |

|

Cahill (2018) [74] |

RCT 267 (240) |

USA (HIC) | Socioeconomically disadvantaged pregnant African American women, overweight/obese before pregnancy | Homebased lifestyle weight management intervention to reduce gestational weight gain | Control group – parenting skills program | Weight (2), body composition, plasma glucose (2), insulin (2), lipids, |

|

Calderon-Mora (2020) [44] |

Cluster RCT 300 (257) |

USA (HIC) | Underserved Hispanic women—uninsured or underinsured/low income/low educational attainment | Group cervical cancer screening education program | Individual counselling with identical education content | Cervical cancer screening (1) |

|

Childs (1997) [75] |

RCT 1000 (455) |

England (HIC) | Children recorded on a child health register from households in inner city areas of high socioeconomic deprivation | Dietary health education program. Families received specific health education information at key child ages | Standard care | Haemoglobin; diet (2); breast feeding (3); intro-duction of pasteurised milk |

|

Cibulka (2011) [76] |

RCT 170 (146) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income pregnant women in an inner-city hospital based prenatal clinic | Oral care education program and provision of dental supplies | Control group – education without dental supplies | Brushing & flossing, sugary drink intake, dental check up |

|

Curry (2003) [77] |

RCT 303 (ITT: 303) |

USA (HIC) | Ethnically diverse, low-income female smokers whose children received care in a paediatric clinic | Smoking cessation intervention | Usual care with no education related to smoking cessation | Smoking cessation (4) |

|

Damush (2003) [78] |

RCT 211 (139) |

USA (HIC) | Low income, inner city primary care patients with acute low back pain in an inner-city neighbourhood health centre | Acute low back pain self-management program | Usual care—referrals and analgesics as indicated, and back exercise sheets | Physical activity (4) |

|

Dawson-McClure (2014) [79] |

RCT 1050 (1050) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income families with a non-Latino Black child in a pre-k program in disadvantaged urban neighbourhoods in New York City | ParentCorps Intervention aimed to increase parent involvement in early learning and behaviour management | ParentCorps intervention not provided in control schools | Parenting practices (4) |

|

Dela Cruz (2012) [80] |

RCT 5,807 (5,807) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income families with young children enrolled in Medicaid or Basic Health Plus in Yakima County, Washington State | Dental health care education | No postcard mailings | Service use |

|

Doorenbos (2011) [43] |

RCT 5605 (5363) |

USA (HIC) | Urban, low-income American Indians and Alaska native patients through mail to patients of an urban American Indian clinic | Mail-out intervention to increase cancer screening | Mailed calendar without cancer screening messages | Smoking cessation, cancer screening (3) |

|

El-Mohandes (2003) [81] |

RCT 286 (167) |

USA (HIC) | Lo- income minority mothers from a community-based hospital | Parenting skills education program | Standard social services care | Service use (2) |

|

El-Mohandes (2010) [82] |

RCT 691 (691) |

USA (HIC) | Pregnant African American women from 6 clinics in Washington, DC | Intervention aimed at reducing environmental tobacco smoke exposure | Routine prenatal care | Environmental tobacco smoke exposure (2) |

|

Emmons (2001) [83] |

RCT 291 (279) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income smokers or recent quitters through community-based health centres | Intervention for smoking parents of young children aimed at reducing household passive smoke exposure | Self-help smoking cessation resources | Household nicotine levels |

|

Falbe (2015) [84] |

RCT 55 parent–child dyads (41) |

USA (HIC) | Overweight or obese Latino parent and child dyads using federally funded care | Obesity intervention (Active and Healthy Families Intervention) | Usual care wait list control condition | BMI (2), BP, lipids, blood glucose, insulin (2), haemoglobin A1C |

|

Fernandez-Jimenez (2020) [85] |

Cluster RCT 635 parent–child dyads (446) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income and minority parents or caregivers and their children from 15 Head Start preschools in Harlem, New York | Health promotion intervention (2 arms) to improve cardiovascular risk factor profiles (Peer-to-Peer Program) | Control group received education unrelated to cardiovascular health | Composite health score, FBS |

|

Fiks (2017) [86] |

RCT 87 (71) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income, Medicaid insured new mothers of infants at high risk of obesity | Intervention to address parenting, maternal wellbeing, feeding and infant sleep | No education—text message appointment reminders only | Infant feeding, sleep, activity; maternal well being |

|

Fitzgibbon (1996) [87] |

RCT 38 families (36) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income inner city Hispanic American families living in the community in Chicago | Dietary intervention to reduce cancer risk | Control received health related pamphlets | Parent support, diet intake (2), BP |

|

Fitzgibbon (2004) [41] |

RCT 256 (195) |

USA (HIC) | Latino women from the Erie Family Health Centre | Combined dietary and breast health intervention | Control group received health information unrelated to breast health | Breast self-examination (2) |

|

Fox (1999) [88] |

RCT 646 (566) |

USA (HIC) | Residents in 9 rural counties with a minimum of 15% of their population below the poverty line and 10% minority population | ‘In-home’ mental health screening and educational intervention | Control group—received list of local resources for health/mental health care | Rates of help seeking behaviour |

|

Gielen (1997) [89] |

RCT 467 (391) |

USA (HIC) | Low income, minority pregnant women smokers from an urban prenatal clinic | Smoking cessation and relapse prevention program (Smoke-Free Moms Project) | Usual care – routine clinic and inpatient smoking cessation education | Smoking cessation |

|

Hayashi (2010) [40] |

RCT 1093 (869) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income, uninsured/underinsured Hispanic women at risk for cardiovascular disease | Lifestyle intervention to improve health behaviours and reduce cardiovascular disease risk factors | Usual in-clinic care only with no lifestyle intervention | Eating habits (3); physical activity (3); BP; BMI; CHD risk; cholesterol; smoking |

|

Hesselink (2012) [90] |

Quasi-experimental 239 (183) |

Nether-lands (HIC) | 1st and 2nd generation Turkish women living in the Netherlands through parent–child centres providing integrated maternity and infant care | Antenatal education program | Usual care | Smoking during pregnancy, parenting behaviours (2) |

|

Hillemeier (2008) [39] |

RCT 692 (362) |

USA (HIC) | Low socioeconomic status women, pregnant or able to become pregnant in low income urban, rural and semirural locations | Health education intervention to improve health behaviours and health status of pre-conceptional and inter-conceptional women | Control group | Physical activity, reading food labels, multivitamin use, BMI, weight, BP, blood glucose, cholesterol |

|

Hoodbhoy (2021) |

Cluster RCT 32,595 |

Pakistan (LMIC) | Pregnant women and their families residing in a rural low-resource setting | Maternal and perinatal health program aimed at reducing all-cause maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality | Routine antenatal | Birth preparedness (composite score & individual items (6)) |

|

Hooper (2017) [91] |

RCT 342 (282) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income African American smokers through a university | Smoking cessation intervention | Standard CBT intervention—not culturally based | Smoking cessation |

|

Hunt (1976) [92] |

RCT 344 (200) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income pregnant women of Mexican descent from Los Angeles County prenatal clinics | Nutrition education intervention | Control group given vitamin and mineral capsules but no education | Dietary nutrients from blood samples (12) |

|

Jacobson (1999) [93] |

RCT 433 (318) |

USA (HIC) | Inner city minority patients 65 + years, presenting for routine primary care at an inner-city public hospital | One-page, low literacy patient education tool encouraging patients to ask their doctor about pneumococcal vaccination | Control group—one-page handout about nutrition | Vaccination rates, vaccination discussions with clinician |

|

Janicke (2008) [94] |

RCT 93 (71) |

USA (HIC) | Families with overweight children in underserved rural settings through Cooperative Extension Service offices | Diet and exercise intervention (two arms) | Waiting list control | Child’s BMI |

|

Jensen (2021) [95] |

Cluster RCT 149814981498149814981498149814981498149814981498(1354) |

Rwanda (LIC) | Families belonging to the most extreme level of poverty with one or more children aged 6–36 months | Early childhood development and non-violence | Usual care including social protection public works program and government support services | Violence and safety, harsh discipline |

|

Kalichman (2000) [42] |

RCT 105 (53) |

USA (HIC) | Inner city, low-income African American women who were patients of a community-based health clinic | Breast self-examination skills building workshop | Control group—sexually transmitted diseases prevention workshop | Breast self-examination skills and rate |

|

Kasari (2014) [96] |

RCT 147 (95) |

USA (HIC) | Families low income or with mothers with low educational attainment, or a primary carer who is unemployed, in low resource communities | Caregiver-mediated intervention for pre-schoolers with Autism | Two active interventions compared: individual and group | Parent–child interaction (4) |

|

Kelly (1994) [97] |

RCT 197 (93) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income, minority women in neighbour-hoods with high rates of sexually transmitted diseases, drug abuse & teenage pregnancy | HIV and AIDS risk reduction group education | Control group received sessions on health topics unrelated to AIDS | Safe sex practices (9) |

|

Kim (2021) [98] |

RCT 63 (56) |

South Korea (HIC) | Low-income women (40–60 years) residing in J Provence, South Korea | Healthy lifestyle intervention addressing nutrition, exercise, stress, psychological distress and dementia prevention | Minimal intervention (booklet with diet and exercise advice) | Health promoting behaviour, BMI, % body fat, waist-hip ratio |

|

King (2013) [38] |

RCT 40 (39) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income, inactive older adults through community centres serving primarily Latino population in San Jose, California | Physical activity intervention | Control group—received information about non-physical activity topics | Physical activity |

|

Kreuter (2010) [45] |

RCT 489 (429) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income African American women through low-income community neighbourhoods | Breast cancer screening intervention | Content equivalent video using a more explanatory and didactic approach | Mammogram |

|

Krieger (2005) [99] |

RCT 274 (214) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income, ethnically diverse urban households in their homes | High intensity intervention to decrease exposure to indoor asthma triggers | Low intensity intervention group | Asthma trigger reduction behaviour |

|

Kulathinal (2019) [100] |

Quasi-experimental 405 (380) |

India (LMIC) | Married men and women from primary health centres in rural Western India | Sexual and reproductive health intervention | Control areas received no mobile helpline | Contraceptive use (2) |

|

Lutenbacher (2018) [101] |

RCT 188 (178) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income pregnant Hispanic women in isolated community in a large metropolitan area | Home visiting program using peer mentors to improve maternal and child health outcomes | Minimal education intervention group received printed educational materials only | Breast feeding (3), prenatal care visits, reading stories, infant sleeping (2) |

| Maldonado (2020) [102] |

Quasi-experimental 379 (326) |

Kenya (LMIC) | Pregnant women attending their first antenatal care visits at a public health facility in a rural sub-county in Kenya | Education addressed antenatal care, family planning, intimate partner violence and microfinance literacy | Standard care (no structured education) | Facility-based delivery, healthy parenting practices (4), financial planning |

|

Manandhar (2004) [103] |

Cluster RCT 24 clusters (24) |

Nepal (LMIC) | Poor married women of reproductive age in a community based rural district | Childbirth and care behaviours intervention | Health service strengthening activities only | Antenatal care (10) |

|

Martin (2011) [104] |

RCT 434 (338) |

USA (HIC) | Low income, rural adults receiving medication at no charge from a public health department or a federally funded rural health centre | Adherence to hypertensive medications intervention | Control group – received cancer information | Medication adherence |

|

McClure (2020) [105] |

RCT 718 (526) |

USA (HIC) | Socioeconomically disadvantaged English- speaking adults who smoked > 5 cigarettes/day and were ready to quit smoking | A novel oral health and smoking cessation program | Standard smoking cessation program | Smoking cessation, oral health behaviours (4) |

|

McConnell (2016) [106] |

RCT 104 (59) |

Kenya (LMIC) | New mothers from a peri-urban community | Postnatal care intervention (2 arms) | Standard care group | Vaccination, family planning, breast feeding (2), index of health practices |

|

McGilloway (2014) [107] |

RCT 149 (137) |

Ireland (HIC) | Families in an urban disadvantaged area defined by their demographic profile, social class composition, and labour market situation | Parenting intervention aimed at fostering positive parent child relationships | Waiting list control | Child conduct (2), service use (2), social competence |

|

Miller (2013) [108] |

RCT 210 (82) |

USA (HIC) | Inner city, low income, minority women who had an abnormal pap smear | Colposcopy appointment adherence intervention (2 arms) | Enhanced standard care—included appointment reminders | Colposcopy (2) |

|

Murthy (2019) [109] |

Quasi-experimental 2016 (1417) |

India (LMIC) | Low-income pregnant women in urban slums (selected based on being in slums that are high proportion low income) | Healthy infant intervention | Control group | Child immunization, healthy infant nutrition (7) |

|

Pandey (2007) [110] |

Cluster RCT 1045 households (1025) |

India (LMIC) | Low socioeconomic status, resource poor, rural village clusters in Uttar Pradesh through the community | Pre-natal and infant health care utilisation | Control village clusters receiving no intervention | Prenatal care (3), tetanus injection, infant received vaccination |

|

Phillips (2014) [111] |

RCT 53 (53) |

Australia (HIC) | Australian Aboriginal children with tympanic membrane perforation through remote communities | Child ear health intervention | Usual care – received information sheet, treat-ment guidelines, advice to attend weekly clinic | Service use |

|

Pitchik (2021) [112] |

Cluster RCT 621 (568) |

Bangla-desh (LMIC) | Pregnant women or primary caregivers of a child < 15 months residing in rural villages | Child development intervention including caregiver behaviours, nutrition, caregiver mental health and lead exposure prevention | No intervention | Stimulation in the home |

|

Polomoff (2022) [113] |

RCT 188 (180) |

USA (HIC) | Cambodian Americans aged 35–75 years at high risk of developing diabetes and meeting the criteria for likely depression | A bilingual, trauma-informed, cardio-metabolic education intervention to decrease diabetes risk | Control intervention (needs assessment and support) | Medication forgetting |

|

Reijneveld (2003) [114] |

RCT 126 (92) |

Nether-lands (HIC) | Turkish immigrants aged 40 + years old recruited via welfare services | Health education and physical exercise program | Control group received the ‘Ageing in the Netherlands’ program | Physical activity |

|

Reisine (2012) [115] |

RCT 120 (93) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income pregnant women attending a community health centre | Dental caries prevention and nutrition education | Control group – received dental caries prevention education only | Mutans levels, Service use, teeth brushing |

|

Ridgeway (2022) [116] |

RCT 1377 (943) |

USA (HIC) | Women 40–74 years presenting for a screening mammogram at a health clinic serving a primarily Latina/Latino population | Education to explain the meaning and implications of mammographic breast density | Usual care (mailed mammogram results only) | Provider conversations relating to breast density |

|

Robinson (2002) [117] |

RCT 218 (122) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income African American women | HIV and sexually transmitted diseases prevention intervention combined with comprehensive sexuality education | Control group—received an HIV pamphlet and a gift card to a local beauty school | Sexual communication (3) |

|

Ryser (2004) [118] |

RCT 54 (54) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income pregnant women | Breast feeding education program | Control group—no exposure to Best Start program | Breast feeding |

|

Saleh (2018) [119] |

RCT Data from 2359 patient records |

Lebanon (UMIC) | Individuals with noncommunicable diseases in rural areas and refugee camps | Hypertension and diabetes self-management education | Control group—no intervention | BP (2), diabetes markers (3) |

|

SantaMaria (2021) [120] |

RCT 519 (397) |

USA (HIC) | Parents of caregivers of youth 11–14 years of age living in medically underserved communities | Sexual health intervention including adolescent vaccinations and HPV | Control intervention – received nutrition and exercise information | Vaccination initiation and completion |

|

Segal-Isaacson (2006) [121] |

RCT 466 (230) |

USA (HIC) | Women with HIV/AIDS | High intensity coping skills, stress management and nutrition education intervention | Low intensity intervention—education with no individualization | CD4 and CD8 cell count, viral load, lipids |

|

Seguin-Fowler (2020) [122] |

Cluster RCT 182 (182) |

USA (HIC) | Women aged ≥ 40 years who were overweight or obese and sedentary; lived rurally in medically underserved towns | Healthy lifestyle intervention to reduce risk for cardiovascular disease | Delayed intervention | smoking cessation, diet, physical activity, weight, blood pressure, cholesterol, blood glucose |

|

Simmons (2022) [123] |

RCT 1467 (1417) |

USA (HIC) | Hispanic and Latino smoking adults | Smoking cessation program | Usual care (mailed Spanish language quit smoking booklet) | Smoking cessation |

|

Smith (2021) [124] |

RCT 240 (240) |

USA (HIC) | Racially and ethnically diverse low-income families with an overweight child attending paediatric primary care | Parenting skill development, connection with community-based services, telephone/face-to-face coaching | Usual care (information about services) | Child physical activity, diet, BMI, mealtime/media/sleep routines |

|

Steptoe (2003) [125] |

RCT 271 (218) |

USA (HIC) | Low-income, minority patients in a deprived ethnically diverse inner-city area | Individualised behavioural dietary counselling intervention targeted increasing intake of fruit and vegetables | Low intensity intervention—brief nutrition counselling | Dietary intake (2), nutrition blood levels (5), body weight, BMI, BP, cholesterol |

|

Wiggins (2005) [126] |

RCT 731 (601) |

England (HIC) | Low-income, inner city, culturally diverse minority women with infants in two disadvantaged inner-city boroughs of London | New mothers support interventions (2 arms) | Low intensity intervention—routine health visiting services | Smoking, infant feeding |

|

Xu (2019) [127] |

RCT 278 (278) |

Indonesia (LMIC) | Resource poor villagers diagnosed with schizophrenia in 9 rural townships | Schizophrenia support intervention (Lay health supporters, E-platform, Aware and iNtegration (LEAN)) | Usual care – included a public health program for people with psychosis | Medication adherence |

Risk of bias

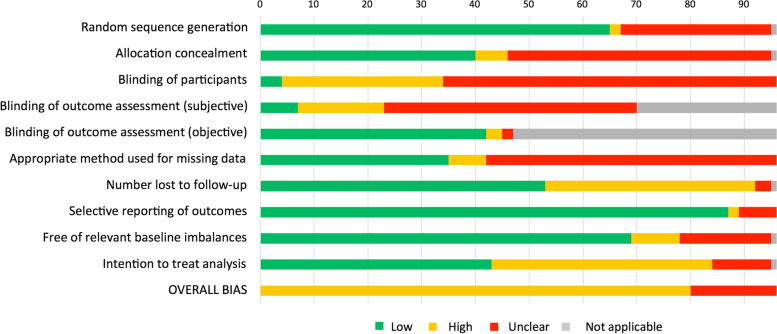

All included studies had either high or unclear overall ROB. The ‘other’ ROB domain of ‘intention to treat analysis’ was most frequently assessed as high. High ROB ratings were also common for ‘number lost to follow up’ and participant blinding (Fig. 2; see Appendix 4 for full details). Visual inspection and interpretation of the funnel plots for each main meta-analysis (to evaluate publication bias) identified no major asymmetries in the distribution of effects for any of the outcomes (Appendix 5), suggesting a low risk of publication bias. Egger’s tests were not conducted because there were < 10 studies in each analysis [23].

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias summary

Certainty in evidence

Our evaluation of certainty in the evidence for each main meta-analysis was conducted using GRADE. Our results are summarised in relation to each meta-analysis (below); detailed results are provided in Appendix 6.

Data synthesis

High clinical and methodological heterogeneity amongst the included studies precluded overall meta-analysis of effect sizes for the primary and secondary outcomes of this review. Instead, we considered outcomes that were evaluated in three or more of the included studies for meta-analysis. Pre-planned subgroup analyses (specified in the protocol) were explored for intervention complexity, the level of intervention and intervention dose.These were undertaken if there were two or more studies in a subgroup. Results of the main meta-analyses of behaviour outcomes are detailed below; results of subgroup analyses and the meta-analyses of biomarker outcomes are detailed in Appendices 7–9.

Meta-analyses: Behavioural outcomes

Fifteen studies had physical activity or exercise outcomes; nine had dietary outcomes; eight had smoking cessation outcomes; seven had cancer screening outcomes; and five had vaccination and breast-feeding outcomes. Meta-analysis was not conducted for studies involving dietary, smoking cessation, vaccination, and breast-feeding outcomes because of varied study designs, outcome measures, follow-up durations and comparison groups.

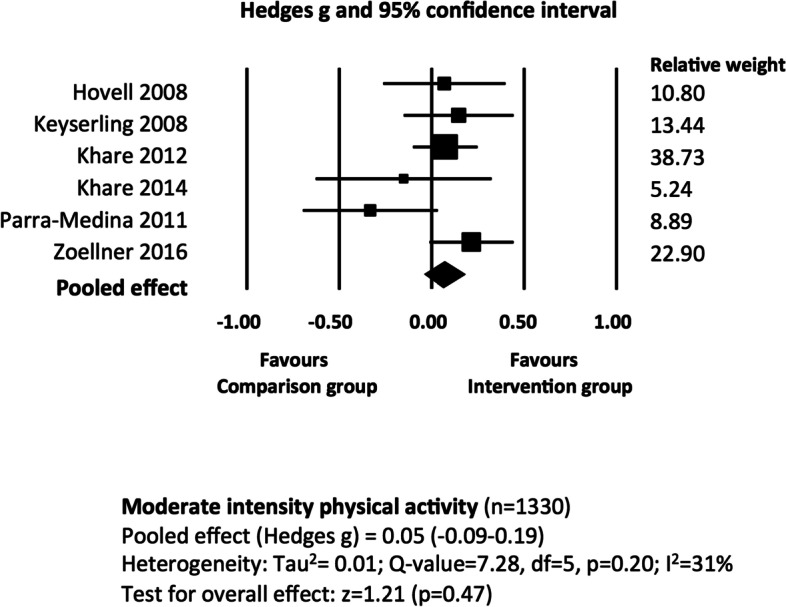

Moderate intensity physical activity

We evaluated the 15 studies with physical activity or exercise outcomes for clinical heterogeneity. Six of these studies (total n = 1330) used ‘moderate intensity physical activity’ as a primary or secondary outcome; the intervention group was compared with a minimal intervention, standard care or control group; and effectiveness was evaluated at ‘long term’ follow up [26–31]. We downgraded certainty in the evidence by one level due to high risk of bias. There is moderate certainty that the pooled effect of educational interventions, when compared to standard care, minimal intervention or control, is 0.05 (95% CI = -0.09–0.19; Tau2 = 0.01%) (Fig. 3). There was moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 31%), which we explored by removing one study that used a differing outcome measure (i.e. the percentage of participants who improved their physical activity in contrast to post-intervention physical activity measures) from the analysis (2011) [31]. This reduced I2 to 0.0% and the pooled effect increased to 0.11 (95% CI = -0.01–0.22). Subgroup analysis of studies with complex or ‘non-complex’ interventions were possible; the results are reported in Appendix 7.

Fig. 3.

The effectiveness of educational interventions at improving moderate intensity physical activity outcomes in socio-economically disadvantaged populations: random effects meta-analysis

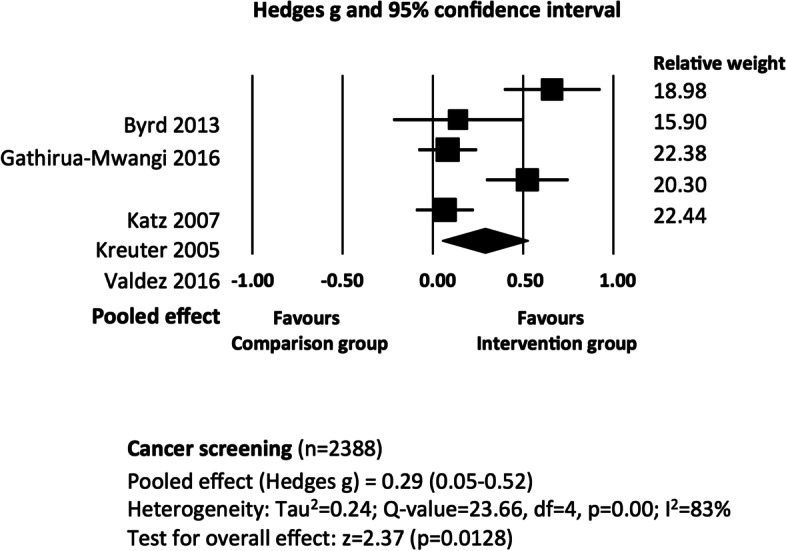

Cancer screening

We evaluated for clinical heterogeneity the ten studies that had cancer screening outcomes. Five of these studies (n = 2388) used rates of cancer screening as their primary or secondary outcome; the intervention group was compared with a minimal intervention, standard care or control group; and effectiveness was evaluated at ‘long term’ follow up [32–36]. We downgraded certainty in the evidence by four levels due to risk of bias, inconsistency (two levels), and imprecision in trial results. There is very low certainty that the pooled effect of educational interventions, when compared to standard care or minimal intervention is 0.29 (95% CI = 0.05–0.52; Tau2 = 0.24) (Fig. 4). The I2 value of 83% indicates a considerable degree of heterogeneity across trial results. We explored this heterogeneity by removing individual studies from the analysis, which had only a minor impact. Removal of one study [32] reduced statistical heterogeneity to a small degree (I2 = 75%). Subgroup analysis of studies with moderate or low-dose interventions were possible; the results are reported in Appendix 8.

Fig. 4.

The effectiveness of educational interventions at improving cancer screening outcomes in socio-economically disadvantaged populations: random effects meta-analysis

Overall synthesis: Vote-counting

We performed separate vote-counting syntheses for the behavioural outcomes and biomarker outcomes. Vote counting based on direction of effect found that 67 of the 81 studies with behavioural outcomes had point estimates that favoured the intervention (83% (95% CI 73%-90%), p < 0.001); ten studies favoured the control, and four studies demonstrated equal effects for intervention and control conditions. Twenty-one of 28 studies with biomarker outcomes had point estimates that favoured the intervention (75% (95% CI 56%-88%), p = 0.002); four studies favoured the control. Calculation of votes based on ‘effectiveness’ being determined by individual studies found 47% of interventions were effective on behavioural outcomes, and 27% were effective on biomarker outcomes. The votes assigned to each study by both vote-count methods are presented alongside the available data and/or effect estimates in Table 3.

Table 3.

Intervention characteristics and effectiveness

| 1st Author (year) | Health condition | Setting | Intervention summaryd | Intervention description |

Outcomes Bold text = behavioural Plain text = biomarker |

Available data (Italics = calculated from reported data) |

Stand. Metric b |

VCC c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alegria (2014) [61a | Mental health | Outpatient health clinics |

Education only Moderate dose Short term f/u |

DECIDE Intervention: 3 x (30–45 min) didactic presentations sessions with opportunities for participation, role-play & reflection. Delivered in person or (rarely) by telephone over 3 months | Self-management | β(SE) = 2.42 (SE 0.90), d = 0.22 | 1 | 1 |

| Fox (1999) [88] | Mental health | Home- based |

Education ± PS Low dose Short term f/u |

Single education session delivered with or without a significant other present. Involved a 1-h interview of 90 min duration (including a video) and a follow up phone call. Provided resource list of local mental health services | Rates of help seeking behaviour | (n = 566) Yates corrected χ2 (1) = 0.977, p = 0.32; favours intervention | 1 | NS |

| Xu (2019) [127] | Mental health | Home- based |

Education + rewards High dose Medium f/u |

LEAN intervention: 2 text messages (at 9am and 7 pm) per day for 6 months, send by an e-platform to the patient and to the lay health supporter, Lay health worker reviewed the patient on a 1:1 basis to ensure medication adherence and monitoring | Medication adherence | Mean difference 0.12 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.22) | 1 | 1 |

| Annan (2017) [65]a | Parenting skills | Home- based |

Education only High dose Short term f/u |

Instruction of parenting skills & social skills (children), practice of positive family interactions. 14 × weekly (in-person) education sessions, 2-h duration each, culturally adapted for non-literate participants. Integrated social learning theory | Child attention problems | Intervention 0.50 (SD 0.18); Control 0.52 (SD 0.26), ES = -0.23 | 1 | 1 |

| Bagner (2016) [66] | Parenting skills | Home- based |

Education only Moderate dose Long term f/u |

Parenting intervention program with education and problem-solving skills training. Up to 7 × weekly one-on-one sessions delivered to caregiver (until caregiver meets mastery), 1 to 1.5 h duration | Observed parent 'don't' skills | Intervention (n = 20) 0.19 (SD 0.18), Control (n = 26) 0.48 (SD 0.29); OR 5.29, p = 0.05 | 1 | 1 |

|

Barry (2022) [68] |

Parenting skills | Community centre |

Education + PS High dose Long term f/u |

Group-based educational intervention providing blocks of weekly group sessions (90–150 min duration) over a period spanning 3 to 5 years | Externalising behaviours | Intervention (Los Angeles) OR 0.38 (95% CI 0.17 to 0.84), p ≤ 0.05 | 1 | 1 |

| Dawson-McClure (2014) [79]a | Parenting skills | School + home-based |

Education + PS High dose Long term f/u |

13 × weekly (2 h) sessions for parents and concurrent sessions for children. Education included flyers and brief information sessions at school events. Delivered in person and by phone to parents. Designed to serve culturally diverse communities | Parent involvement (parent rated) | Intervention Estimate 0.78 (SE 1.55), d = 0.38 | 1 | 1 |

| El-Mohandes (2003) [81] | Parenting skills | Home- based + community centres |

Education + PS High dose Long term f/u |

32 home visits and 16 play group sessions; weekly visits for first 5 months, followed by biweekly group sessions of developmental play groups and parent support groups (45 min). Monthly support calls, total duration 1 year | Number of well infant visits at 12 months | (Total n = 167) Intervention 3.51; Control 2.68, p = 0.0098 | 1 | 1 |

| Fiks (2017) [86] | Parenting skills | Home- based |

Education + PS High dose Long term f/u |

2 educational sessions delivered in-person (1 prenatal and 1 at age 4 months), total duration 11 months (2 months prenatal and 9 months postnatal). Peer to peer Facebook group during intervention. Based on social cognitive theory | Infant feeding behaviours: Total score | Intervention 40.7; Control 38.2, ES = 0.45 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.92) | 1 | 1 |

| Hesselink (2012) [90] | Parenting skills | Community centres & home-based |

Education + PS High dose Long term f/u |

Antenatal education and parenting program involving 8 group classes (2 h each)—seven before and 1 after delivery, and 2 home visits (1 h each) after delivery. Quasi-experimental study | SIDS prevention behaviour | β = -0.024 (95% CI -2.9 to 2.4); favours control | 0 | NS |

| Jensen (2021) [95] | Parenting skills | Home-based |

Education only High dose Long term f/u |

Approximately 14 × 1 h home visits over a 9-month period. Followed an educational curriculum, included active play sessions with live feedback and linkage to government support service | Harsh discipline | ‘Difference in difference’ 0.74 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.84), p < 0.001; favours intervention | 1 | 1 |

| Kasari (2014) [96] | Parenting skills | Home- based |

Education only High dose Medium f/u |

Individualized caregiver-mediated intervention with caregivers coached in the treatment model with their child. 2 x (1 h session) weekly sessions; duration 12 weeks (24 sessions, 24 h). Written material in participants native language | Parent–child interaction: Total time in joint engagement | Cohen’s f = 0.21 (“moderate treatment effect”) | 1 | 1 |

| Luten-bacher (2018) [101] | Parenting skills | Community centre + home-based |

Education + PS Moderate dose Long term f/u |

The Maternal Infant Health Outreach Worker program. Monthly individual home visits (1 h) and periodic group gatherings. Bilingual | Breast-feeding duration (weeks) | Intervention (n = 76) median 28.0 (IQR 12–28); control (n = 70) median 28.0 (IQR 12–28); p = 0.76 | < > | NS |

| Mc Gilloway (2014) [107]a | Parenting skills | Community centre |

Education + PS High dose Long term f/u |

Incredible Years Basic parent program. 14 (2 h) sessions delivered over 12–14 week period, Education provided in groups using role plays and video material. Intervention culturally tailored, based on social cognitive theory | Child problem behavior | Mean difference 2.0 (95% CI 1.1 to 3.0), ES = 1.07 | 1 | 1 |

|

Pitchik (2021) [112] |

Parenting skills | Community centre + home based |

Education + PS High dose Long term f/u |

2 intervention arms: 18 × 45–60 min Group sessions (with 3–6 women/caregivers); or 9 × group sessions alternated with 9 × 20–25 min home visits. The material covered was equivalent across the delivery mechanisms, duration 9 months | Stimulating caregiving practices | Group 4.22 (95% CI 3.97 to 4.47); combined 4.77 (4.60 to 4.96); control 3.24 (3.05 to 3.39); in favour of intervention | 1 | 1 |

| Segal-Isaacson (2006) [121] | Diet | Community centres |

Education + skills training High dose Long term f/u |

Nutrition education and coping skills/stress management sessions. Phase 1- high intensity received group sessions of therapist guided exercises. Phase 2—high intensity received behavioural exercises led by therapist plus expert advice from relevant professionals (nutritionist, exercise trainer or pharmacist). 10 group sessions and 6 behavioural exercises | Triglycerides | Group 1 (n = 97) 188 (SD = 103), group 3 (n = 79) 178 (SD = 96); d = 0.10 (95% CI -0.20 to 0.40) | 1 | NS |

| Steptoe (2003) [125]a | Diet | Health clinics (primary care) |

Education only Moderate dose Long term f/u |

Individualised behavioural dietary counselling intervention targeted increasing intake of fruit and vegetables. 15-min consultation followed by another 15-min consultation after 2 weeks. Delivered individually face-to-face. Time matched with nutrition education counselling. Behavioral counselling integrated social learning theory and the stage of change model |

No of portions of fruit/vegetables per day Plasma β-carotene |

Adjusted difference in change 0.89 (95% CI 0.25 to 1.54) Adjusted difference in change 0.18 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.37) |

1 1 |

1 1 |

| Zoellner (2016) [26]a | Diet | Community centre & home-based |

Education + skills in self-monitoring High dose Medium f/u |

SIPsmartER intervention: 3 small-group classes (90-120 min) (delivered in week 1, week 6 and week 17) + 1 live teach back call (avg of 18.6 min duration) + 11 interactive voice response calls (weekly for the first 3 weeks and then bi-weekly for the rest of the intervention) (avg 6.9 min duration of each call). Group classes delivered face-to-face. Culturally sensitive, integrated Theory of Planned Behaviour |

Sugar sweetened beverage consumption Blood Glucose |

Relative effect between cond-itions -14 (95% CI = -23 to -6) Relative effect between cond-itions -0.8 (95% CI -3.6 to 2.0) |

1 1 |

1 NS |

| Avila (1994) [37] | Diet & exercise | Community health clinics |

Education + exercise Moderate dose Medium f/u |

Weight reduction/exercise classes including 25-min exercise (stretching and walking) component with nutritional education, self-change behavioural modification strategies, buddy system and an exercise component. 1 h per week for 8 weeks. Bilingually delivered |

Exercise fre-quency (days/wk) BMI |

Intervention (n = 21) 3 (SD 2.6), control (n = 18) 1 (SD 2) Intervention 28.7 (SD 2.2) Control 32.0 (SD 2.27) |

1 1 |

1 1 |

| Baranowski (1990) [67] | Diet & exercise | Community centre or school |

Education + counselling + exercise High dose Short term f/u |

Program to improve diet and increase aerobic activity. Sessions involved education, behavioural counselling, food/activity records, goal setting, problem solving and aerobic activity. Intervention involved 1 × 90-min education and 2 fitness sessions per week for 14 weeks |

Per week energy expenditure Resting pulse rate |

Intervention (n = 50) 247 (SD 46.6); Control (n = 48) 248 (SD 29.4); d = -0.03 (95% CI -0.42 to 0.37) NS |

0 - |

NS NS |

| Befort (2016) [69] | Diet & exercise | Community cancer centres |

Education + PS High dose Long term f/u |

Education program for breast cancer survivors Phase 2 (maintenance intervention) involving 25 biweekly conference call sessions. (Phase 1 included 25 weekly 60-min conference call sessions) | Weight change | Phone counselling (n = 85) 3.3 (SD 4.8); newsletter (n = 83) 4.9 (SD 4.9) d = -0.33 (95% CI -0.63 to -0.03); favours phone counselling intervention | 1 | 1 |

| Brooking (2012) [53] | Diet & exercise (diabetes prevention) | Community centre |

Education + PS + food High dose Long term f/u |

Involved group and individual education sessions, written resources, cooking demonstrations and shopping tours. Weekly face to face contact with both group and individual. Three 8-week phases | Weight (kg) | Intervention (n = 20) 100.6 (SD 20.4); Control (n = 21) 97.7 (SD 20.01); d = 0.14 (95% CI -0.47 to 0.76); favours control | 0 | 0 |

| Staten (2004) [56] | Diet & physical activity | Community centres |

Education only High dose Long term f/u |

Arm 1 – 1:1 counselling to increase fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity, referral to education classes. Arm 2—counselling and health education plus education classes and a monthly newsletter. Arm 3—counselling, health education and community health worker support. Bilingual, based on social cognitive theory |

Physical activity levels > / = 150 min/week High blood pressure |

Intervention (arm 2, n = 70) % difference 2.6%, control (n = 73) % difference 0% Intervention (arm 2): 11.4% difference, control 11% |

1 1 |

NS NS |

| King (2013) [38] | Physical activity | Community centres |

Education + pedometer Moderate dose Medium f/u |

4 × monthly virtual advisor sessions accessed on a computer, average 7 min each. Individually tailored walking program, physical activity education, personalised feedback, problem solving & goal setting. Culturally and linguistically tailored, bilingual intervention | Increase in walking | Between group difference 226.7 (95% CI 107.0 to 346.4), F(1,38) = 13.6, p = 0.0008, ES = 1.2 | 1 | 1 |

| Reijneveld (2003) [114] | Physical activity | Community-based |

Education + exercise High dose Short term f/u |

8 × 2-h health education sessions offered by a peer educator. Each session ended with a group exercise session | Physical activity (low score = better) | Intervention (n = 54) 9.87; control (n = 38) 9.26; Difference -0.12 (95%CI -0.67 to 0.29) ES 0.04 | 0 | NS |

|

Alias (2021) [62] |

Healthy lifestyle | Primary care clinics, community |

Education + PS High dose, Long term f/u |

12 × 2-h weekly sessions for groups of 15 people. 9 delivered in primary care centre; 3 involved local outings to public spaces (for physical activity/shopping/social activities) | Social participation | Between group data not reported. Raw data show results in favour of control group | 0 | NS |

| Fernandez-Jimenez (2020) [85] | Healthy lifestyle | Community or home- based |

Education ± activity monitor High dose Long term f/u |

Individual intervention 1: 8–12 counselling sessions with a lifestyle coach. Held every 3–4 weeks, lasting 45 min for first 8 months, 4 complimentary sessions offered over the following 4 months. Also provided with activity monitoring device. Group intervention 2: monthly group meetings for 12 months, 45 min each | Change in a composite health score | Group intervention: mean difference 0.00 (95% CI -0.50 to 0.49) | < > | NS |

| Hovell (2008) [29] | Healthy lifestyle | Community centre |

Education + exercise High dose |

Aerobic dance intervention (vigorous low impact aerobic dance sessions) plus 30 min exercise/diet education. 3 sessions per week (each 90 min) over 6 months. Culturally tailored and bilingual, developed for low literacy |

Moderate exer-cise (min/2 wk) Relative VO2max |

B = -0.184 (95% CI -0.87 to 0.497) p = 0.596; favours control B = 2.533 (95% CI 1.10 to 3.97), p < 0.001 |

0 1 |

NS 1 |

| Keyserling (2008) [30] | Healthy lifestyle | Community health centre & home-based |

Education + PS High dose Long term f/u |

Lifestyle intervention to improve physical activity and diet. 2 individual counselling sessions, 3 × 90-min group sessions and 3 phone calls from a peer counsellor over 6 months, followed by a 6-month maintenance phase with 1 individual counselling session and 7 monthly peer counsellor calls. Reinforcement mailings of pamphlet & 2 postcards | Moderate intensity physical activity (mins/day) | Difference between means 1.5 (95% CI -1.6 to 4.6) | 1 | NS |

| Khare (2012) [27] | Healthy lifestyle | Community centre & home-based |

Education only High dose Long term f/u |

Minimum intervention—received CVD risk factor screening and educational materials. Enhanced intervention—also received a 12-week lifestyle change (nutrition and physical activity) intervention: 90-min weekly sessions for 12 weeks. Bilingual, based on social Cognitive Theory and Transtheoretical Model |

All intensity physical activity (hours/week) BMI |

MI (n = 280) 9.2 (SD 6.0); EI (n = 225) 9.7 (SD 6.6), d = 0.08 (95% CI -0.10 to 0.26) MI (n = 280) 31.5 (SD 7.6); EI (n = 225) 31.8 (SD 7.7), d = 0.04 (95% CI -0.14 to 0.21) |

1 1 |

NS NS |

| Khare (2014) [28] | Healthy lifestyle | Community centre & home-based |

Education only High dose Long term f/u |

Minimum intervention—received CVD risk factor screening and educational materials. Enhanced intervention—also received a 12-week lifestyle change (nutrition and physical activity) intervention: 90-min weekly sessions for 12 weeks. Bilingual, based on social Cognitive Theory and Transtheoretical Model |

All intensity physical activity BMI |

MI (n = 37) 10.0 (SD 5.61); EI (n = 30) 8.48 (SD 5.73), d = 0.27 (96% CI -0.22 to 0.75) MI (n = 37) 32.03 (SD 8.06); EI (n = 30) 30.22 (SD 5.57), d = 0.26 (95% CI -0.23 to 0.74) |

1 1 |

NS NS |

|

Kim (2021) [98] |

Healthy lifestyle | Community centre |

Education + exercise Moderate dose Short term f/u |

8 week group-based intervention addressing nutrition, exercise, stress management psychological wellbeing and cognitive health. Involved education and physical activity components plus recommended daily exercise (> 10,000 steps or > 30 min mod exercise per day) |

Health promot-ing behaviour % body fat |

d = 1.27, p < 0.001; results favour intervention d = 0.53, p = 0.62; results equivocal for both groups |

1 (< >) |

1 (NS) |

| Parra-Medina (2011) [31] | Healthy lifestyle | Home- based |

Education only High dose Long term f/u |

Standard care plus 12 motivational, ethnically tailored newsletters over 1 year, an in-depth introductory telephone call, & up to 14 brief, motivationally tailored telephone counselling calls from research staff over 1 year. Print materials for less than 8th grade reading level, based on transtheoretical model and social cognitive theory | Improvement in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity | (n = 142) Intervention 30.7%, control 44.8%; OR 0.63 (95% CI 0.24 to 1.68); favours control | 0 | 0 |

|

Polomoff (2022) [113] |

Healthy lifestyle | Community centres |

Education + PS + medication management High dose Long term f/u |

A bilingual, trauma-informed, cardiometabolic education intervention to decrease diabetes risk. 2 intervention arms: Eat,walk sleep (EWS) (or EWS + 3 or more MTM (medication therapy management) sessions. EWS involved 3 individual sessions and 24 group sessions over a 12-month period | Medication forgetting | Results in favour of intervention but between-group differences not significant | 1 | NS |

| Seguin-Fowler (2020) [122] | Healthy lifestyle | Community-based |

Education + PS + exercise, High dose Medium term f/u |

24 weeks of hour-long, twice weekly classes held in community-based locations. Sessions included strength training, aerobic exercise and health related education, civic engagement activities and out of class assignments |

Moderate and vigorous physical activity Total cholesterol |

Intervention: 41.5% improved, control: 21.5% improved (p = 0.008) 2.8% difference, p = 0.66); favours intervention |

1 1 |

1 NS |

| Saleh (2018) [119] | Healthy lifestyle | Community centre & home-based |

Education only High dose Long term f/u |

Weekly short message service over 2 years. Messages included medical information & reminders of appointments. Information included hypertension and diabetes guidelines for management, dietary habits, body weight, smoking | Blood pressure controlled at post-test | Intervention (n = 426) 63.6%; control (n = 362) 58.4%; OR = 0.80 (95% CI 0.60 to 1.07) | 1 | NS |

| Hayashi (2010) [40] | Healthy lifestyle | Community health centres |

Education only Moderate dose Long term f/u |

WISEWOMAN Program: 3 sessions (at 1, 2, 6 months post enrolment). Initial session of 40–70 min, 3 lifestyle intervention sessions lasted 30–45 min. Delivered face-to-face. Bilingual and bicultural Intervention, outcome measures selected based on transtheoretical model |

Improvement in eating habits Total cholesterol > 240 mg/dL |

Intervention (n = 433) 71%; Control (n = 466) 48%; RR 3.3, p < 0.001; favours intervention Intervention 200.3; control 199.3, p = 0.906; favours control |

1 0 |

1 NS |

| Suhadi (2018) [57] | Healthy lifestyle | Community centres |

Education only Moderate dose Long term f/u |

Oral presentations and discussion of topics such as hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes. Participants were handed posters, activity manuals and 4 booklets with education material. 4 sessions of 90-min each done consecutively every 1–2 months | BMI | Intervention (n = 82) 24.1 (SD 4.5); control (n = 108) 24.0 (SD 4.4); d = 0.02 (95% CI -0.26 to 0.31) | 0 | NS |

|

Fitzgibbon (1996) [87] |

Healthy lifestyle (diet/breast health) | Community centre |

Education only High dose Short term f/u |

12 weeks × 1-h classes. Culture specific family-based dietary intervention to reduce cancer risk among low-literacy, low-income Hispanics by reducing fat intake, increasing fibre intake, increasing nutrition knowledge and increasing parental support for healthy eating |

Saturated fat intake Blood pressure |

Intervention (n = 18) 11.2 (SD 4.0), control (n = 18) 13.6 (3.1) NS |

1 - |

NS NS |

| Bray (2013) [71]a | Diabetes self-man-agement | Health clinics |

Education only High dose Long term f/u |

Point of care diabetes care management involved education, self-management coaching and medication adjustment. 1:1 face to face sessions. Patients seen an average of 4 times over 12 months by a nurse, pharmacist, or dietitian care manager for 30–60 min, seen every 3–6 months by a care manager for an additional 2 years. Quasi-experimental study | Haemoglobin A1C | Intervention (n = 368) 7.4 (SD 1.9); Control (n = 359) 7.8 (SD 2.0), d = -0.21 | 1 | 1 |

| Brown (2013) [73] | Diabetes self-man-agement | Community centre |

Education + PS High dose Long term f/u |

Culturally tailored diabetes self-management education including educational videos and group activities. Conducted near participants home, required to partner with a relative/friend. 1 year duration with 52 contact hours. 26 educational and group support sessions (each 2 h) | Haemoglobin A1C | Females (n = 70): Intervention 10.8 (SD 2.5), Control 11.5 (SD 3.0); NS | 1 | NS |

| Andrews (2016) [64] + a | Smoking cessation | Community centres + home-based |

Education + PS + Nicotine replacement Moderate dose Long term f/u |

6 × weekly group sessions. Community health workers provided 1:1 contact (× 16) to reinforce educational content and behavioural strategies from the group sessions & provide social/psychological support. 24-weeks duration | 7-day point prevalence abstinence | OR = 0.44 (95% CI 0.18 to 1.07), favours intervention | 1 | NS |

| Berman (1995) [70] | Smoking cessation | School- based |

Education + PS High dose Long term f/u |

Smoking cessation group class – seven sessions, 1.5 h each. Received tailored support letters and brief tailored smoking cessation booster messages at end of 3- and 6-month interviews. Quasi-experimental study | Continuous abstinence | (Total n = 132), Intervention 6.4%; Control 7.3%; χ2=0.042; RR = 0.88; favours control | 0 | NS |

| Brooks (2018) [72] | Smoking cessation | Home- based |

Education + MI Moderate dose Long term f/u |

Up to 9 education sessions from a Tobacco Treatment Advocate over 6 months, Delivered in person (at home). Involved motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural strategies and cessation counselling. Also offered community resources + educational materials. Considered racial and linguistic diversity | 30-day point prevalence abstinence | Adjusted OR 2.98 (95% CI 1.56 to 3.94) | 1 | 1 |

| Curry (2003) [77]a | Smoking cessation | Outpatient paediatric health clinics |

Education + MI Moderate dose Long term f/u |