Abstract

The FOP-fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) fusion protein is expressed as a consequence of a t(6;8) (q27;p12) translocation associated with a stem cell myeloproliferative disorder with lymphoma, myeloid hyperplasia and eosinophilia. In the present report, we show that the fusion of the leucine-rich N-terminal region of FOP to the catalytic domain of FGFR1 results in conversion of murine hematopoietic cell line Ba/F3 to factor-independent cell survival via an antiapoptotic effect. This survival effect is dependent upon the constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of FOP-FGFR1. Phosphorylation of STAT1 and of STAT3, but not STAT5, is observed in cells expressing FOP-FGFR1. The survival function of FOP-FGFR1 is abrogated by mutation of the phospholipase C gamma binding site. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) is also activated in FOP-FGFR1-expressing cells and confers cytokine-independent survival to hematopoietic cells. These results demonstrate that FOP-FGFR1 is capable of protecting cells from apoptosis by using the same effectors as the wild-type FGFR1. Furthermore, we show that FOP-FGFR1 phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3)-kinase and AKT and that specific inhibitors of PI3-kinase impair its ability to promote cell survival. In addition, FOP-FGFR1-expressing cells show constitutive phosphorylation of the positive regulator of translation p70S6 kinase; this phosphorylation is inhibited by PI3-kinase and mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitors. These results indicate that translation control is important to mediate the cell survival effect induced by FOP-FGFR1. Finally, FOP-FGFR1 protects cells from apoptosis by survival signals including BCL2 overexpression and inactivation of caspase-9 activity. Elucidation of signaling events downstream of FOP-FGFR1 constitutive activation provides insight into the mechanism of leukemogenesis mediated by this oncogenic fusion protein.

The consequence of a translocation involving fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) at chromosomal region 8p12 and either one of five unrelated partner genes (16, 55, 73) is the expression of an aberrant tyrosine kinase leading to a distinctive stem cell leukemia-lymphoma syndrome. FGFR1 belongs to a family of structurally related tyrosine kinase receptors encoded by four different genes. These receptors are glycoproteins composed of two to three extracellular immunoglobulin-like domains, a transmembrane domain, and a split tyrosine kinase domain. Activation of FGFRs results in the stimulation of multiple signaling pathways, which are not completely defined yet. The FGFR family has been linked to the activation of phospholipase C gamma (PLC-γ) (11, 52) and two other pathways that both activate the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases (MAPKs) through different adaptors, i.e., SHC and FRS2/SNT (44, 58, 80).

Numerous skeletal and developmental disorders result from mutations in the FGFR genes (12, 82). Activation of FGFRs have also been involved in cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. FGFR1 has been implicated in breast cancers (77), and FGFR2 has been implicated in T-lymphocytic tumors (37). Activating mutations in FGFR3 are frequent in bladder and cervix carcinomas (14). The t(4;14) translocation associated with multiple myeloma results in increased FGFR3 expression or selective expression of mutated alleles of FGFR3 (17, 68) that contribute to tumor progression (18).

In the stem cell myeloproliferative disorder linked to the chromosomal 8p12 region, three FGFR1 partners have been cloned, FOP at 6q27 (65), CEP110 at 9q33 (33), and FIM/ZNF 198 at 13q12 (64, 67, 72, 84). In each case, the N-terminal region of the partner, which contains protein-protein interaction motif domain, is fused to the tyrosine kinase domain of FGFR1 (33, 64, 65, 67, 72, 73, 84). The aberrant fusion proteins have constitutive kinase activity (33, 64) triggered by dimerization mediated by FGFR1 protein partner (57, 85).

Identifying the function of FGFR1 fusion proteins is essential to understanding how the aberrant receptors are involved in malignant disease. One approach is to unveil the signal transduction pathways activated by the translocations. We recently reported that FIM/ZNF198-FGFR1, the fusion product of the myeloproliferative disorder associated with the t(8;13) translocation, promotes survival of Ba/F3 cells after interleukin 3 (IL-3) withdrawal, whereas ligand-activated FGFR1 induced not only cell survival but also IL-3-independent growth (57). In this report, we have characterized the signal transduction pathways and the transforming properties of FOP-FGFR1, the fusion protein resulting from the t(6;8) translocation associated with the 8p12 myeloproliferative disorder. Our results demonstrate that the fusion protein is constitutively activated and promotes ligand-independent cell survival of Ba/F3 cells via an antiapoptotic effect. Mutational analysis shows that this survival effect is dependent upon constitutive FGFR1 tyrosine kinase activity. We show that the constitutively activated FGFR1 kinase is able to phosphorylate STAT1 and STAT3, but not STAT5. We also show that FOP-FGFR1 can utilize the same effector proteins, including PLC-γ and MAPK, as the wild-type FGFR1 to promote signal transduction. Experiments reported here also strongly suggest a major role of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway in maintaining the cell survival induced by FOP-FGFR1. The cell survival effect of FOP-FGFR1 via PI3K and AKT signaling pathways is dependent on targets that eventually control translation, i.e., mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)/p70S6 kinase (p70S6K).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and culture conditions.

Ba/F3 cells were grown in RPMI plus 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and IL-3. Cos-1 and NIH 3T3 (parental and FGFR1-expressing cell line NFIg26) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% new born calf serum.

DNA constructs.

Full-length FOP cDNA was inserted in pcDNA3 expression vector (Invitrogen) and Myc epitope tagged at its 5′ end. FOP-FGFR1 cDNA was constructed in two steps. A 5′ BclI fragment of FOP containing the Myc epitope was subcloned into pcDNA3 containing a partial BclI-digested FOP-FGFR1 cDNA (65). The complete FOP-FGFR1 was then obtained by subcloning the partial BamHI-Nhel-digested FOP-FGFR1 and inserted in the BamHI-Nhel-digested pCHIM construct containing the 3′ FGFR1 part (57). The Quickchange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was used to introduce point mutations within the FGFR1 portion of the FOP-FGFR1 fusion cDNA in pcDNA3 vector according to the manufacturer's recommendations: a kinase-defective (pFOP-FGFR1K259 to A [K259/A]) and PLC-γ-binding-defective (pFOP-FGFR1 Y511/F) FOP-FGFR1 mutants were made by changing lysine 259 (lysine 514 in the FGFR1 sequence [5]) to alanine and tyrosine 511 (tyrosine 766 in the FGFR1 sequence [52]) to phenylalanine, respectively (Fig. 1). Each construct was verified by sequencing. pFGFR1A, the full-length FGFR1 cDNA was excised from pFlg16 (23) by digestion with ApaI and NcoI and was inserted in the Apal-EcoRV sites of pcDNA3 by blunt-end ligation. TEL-JAK2 cDNA inserted in pcDNA3 (45), a kind gift of O. Bernard, was used as a control. The plasmids which direct the expression of glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-tagged SH2-PI3-kinase (GST-SH2 N-terminal p85α and GST-SH2 C-terminal p85α, kindly provided by M. Waterfield), GST-PLC-γ and GST-SHC (gift from B. Margolis), and GST-GRB2 (gift from R. Rottapel), were used. rCD2p110 plasmid which contains the p110 catalytic subunit of PI3-kinase (66), and pSG5-PKBTAG containing full-length protein kinase/AKT cDNA N-terminally tagged with hemagglutinin (10) were kindly provided by D. A. Cantrell and B. M. Burgering, respectively.

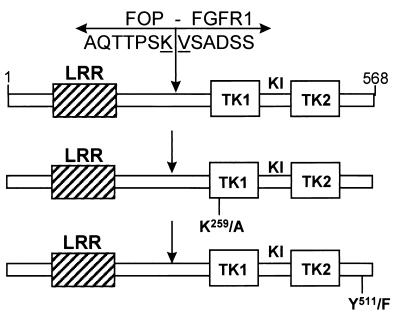

FIG. 1.

FOP-FGFR1 fusion constructs. FOP-FGFR1 encodes a protein of 568 amino acid residues containing the FOP N terminus leucine-rich region (LRR) fused to the catalytic domain of FGFR1 composed of part of the juxtamembrane domain, the tyrosine kinase domain comprising the two tyrosine kinase subdomains TK1 and TK2 interrupted by a short kinase insert (KI), and the C-terminal tail. K259/A is a single mutation in FOP-FGFR1 which inactivates the kinase activity (K259 corresponds to K514 in the FGFR1 sequence and is an ATP binding site). Y511/F is a single mutation that abolishes the PLC-γ binding site (Y766) in the context of the native FGFR1 (52, 63). Arrows indicate the t(6;8) breakpoint. FOP and FGFR1 amino acid sequences around the breakpoint are indicated.

Transient and stable transfections.

Cos-1 cells were transiently transfected using 2 μg of plasmid DNA and 3 μl of FuGENE6 transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Meyland, France) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Stable Ba/F3 cell lines were generated by electroporation of the different expression constructs or empty vector and selected in IL-3 medium plus G418 (1 mg/ml) as previously described (57). FGFR1-positive cells were selected in G418 medium containing FGF1 (10 ng/ml) plus heparin (10 μg/ml) (23) and refed every 2 days. Stable TEL-JAK2 clones were selected as described (40). For reporter assays, NIH3 T3 cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of pKH165(4×StRE-luciferase) reporter plasmid containing four copies of the m67 high-affinity binding site for STAT1 and STAT3 (a kind gift of D. Donoghue [36]), 4 μg of plasmid containing full-length cDNA of either FOP-FGFR1 or FOP-FGFR1 mutants or FGFR1 wild type, and 0.1 μg of pRL-TK Renilla luciferase control reporter vector (from the Promega [Madison, Wis.] kit) were used for normalization of values. Twenty-four hours after transfection (FuGENE6 transfection reagent), cells were starved for 40 h in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium plus 0.2% new born calf serum.

Antibodies, immunoprecipitations, immunoblotting, and GST pull-downs.

The mouse monoclonal anti-Myc (9E10) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology was used for immunofluorescence studies. The following polyclonal antibodies were used for immunoblotting: anti-C-FGFR1 (C-15), anti-C-JAK2 (C-20), anti-ERK2 (C-14), anti-PLC-γ1 (1249), anti-STAT1 (E-23), and anti-p70 S6 kinase (p70S6K; C-18) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; anti-SHC (06–203), anti-phospho-STAT1 (Y701), anti-phospho-STAT5 (Tyr694), and antiphosphotyrosine (4G10); anti-phospho-AKT/PKB (Ser473) and anti-AKT (PhosphoPlus AKT [Ser473] antibody kit; New England Biolabs); anti-BCL2 and anti-STAT3 (Transduction Laboratories); anti-P-MAPK (V677A; Promega); anti-phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705) and anti-phospho-p70S6K (Thr389) (Cell Signaling Technology); and anti-STAT5B (R&D systems). For immunoprecipitation assays, protein extracts in lysis buffer from 2 × 107 cells were incubated with either anti-PI3K (06-195; Upstate Biotechnology Inc.), anti-phospho-STAT5, or anti-C-FGFR1 antiphosphotyrosine antibodies. Total or immunoprecipitated protein extracts (50 to 100 μg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), blotted onto membranes (Hybond-C; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and probed with the antibodies described above. For GST pull-down experiments, 5 to 20 μg of bacterially produced GST fusion proteins were prebound to glutathione-Sepharose beads and incubated with 500 μg of total protein extracts. After 2 h of rotating at 4°C, the beads were processed for SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Autokinase activity and tyrosine phosphorylation analysis of FOP-FGFR1 fusion proteins.

NIH 3T3 cells were transiently transfected with wild-type and mutant FOP-FGFR1 cDNAs or with the empty vector for 24 h and then serum starved for 2 h. An FGFR1-expressing cell line (NFIg26 [23]) was used as a positive control. Cells were then stimulated or not with FGF1 plus heparin. Cell lysates and C-FGFR1 immunoprecipitations were done as described (79). Immunoprecipitates were challenged as described in a previous work (64).

Biological assays.

Ba/F3 cells were washed three times and plated in medium without IL-3 for all IL-3 withdrawal experiments. The number of viable cells was measured by trypan blue exclusion. For PI3K inhibitor experiments, 1 and 10 μM concentrations of wortmannin and LY294002 (Sigma-Aldrich) respectively, and 0 μM (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] alone for both the inhibitors) (78) were used. For MAPK inhibitor experiments, 50 to 100 μM concentrations of PD98059 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (54) and 5 μM U0126 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (28) were used. For mTOR experiments, 10 nM rapamycin (Sigma) (40) was used.

Apoptosis was documented on cell suspensions and cytospin preparations by the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) method by using an in situ cell death detection fluorescein kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Analysis was done by flow cytometry (FACScan; Becton Dickinson) or by confocal laser system microscopy. The apoptotic index was determined by counting more than 200 cells within four different and not adjacent fields (number of apoptotic cells/total number of cells).

NIH 3T3 cells were subjected to a dual luciferase reporter assay according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). The efficiency of the transfection was corrected by the activity of firefly luciferase normalized by that of Renilla luciferase. The Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad) was used to quantify protein concentrations. The fold induction was obtained by the fold induction of each corrected value over that obtained in the absence of any treatment with pcDNA3 empty vector condition.

The caspase-9 colorimetric assay from R&D systems (catalogue number BF10100) was used according to the manufacturer's suggestions. At various time points over a 48-h period without IL-3, 2 × 106 Ba/F3 cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in 50 μl of cell lysis buffer of the kit. The enzymatic reaction for caspase activity was carried out in a 96-well flat-bottom microplate. Caspase assays were done as outlined by the manufacturer, and the cleavage of the substrate was monitored on a microtiter plate reader at 405 nm. Results were plotted as (percent) activity of caspase-9 versus the incubation time after IL-3 removal.

Studies described below on the signaling pathways and biological responses of FOP-FGFR1 fusion protein were done using the IL-3-dependent Ba/F3 cell line, except for the autophosphorylation and reporter assays, and GST pull-down experiments which were done on NIH 3T3 and Cos-1 cells, respectively. Ba/F3 cells were stably transfected with the vector alone or with the fusion FOP-FGFR1 cDNAs (native or mutants). Ba/F3 cells expressing either FGFR1 or TEL-JAK2, which both sustain cell proliferation after IL-3 withdrawal (see references 79 and 45, respectively), were used as controls. The level of protein expression was checked in all the transformed cell lines by Western blot analysis (data not shown). Cells expressing FOP-FGFR1 (wild-type and mutants) and TEL-JAK2 were cultured in the presence or absence of IL-3. FGFR1-expressing cells were cultured in the presence or absence of FGF1 and heparin (57).

RESULTS

FOP-FGFR1 has a constitutive tyrosine kinase activity.

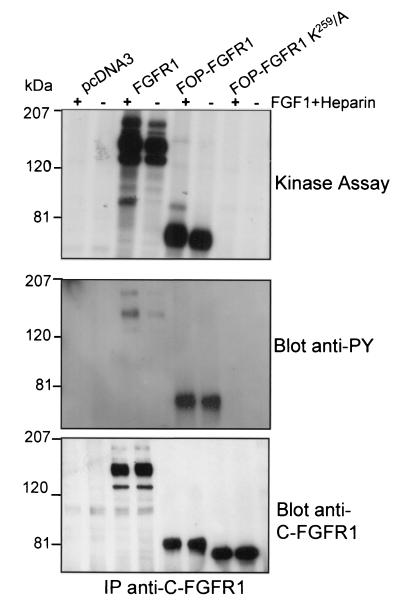

NIH 3T3 cells were transiently transfected with the FOP-FGFR1 construct (Fig. 1). Cells were lysed and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-C-FGFR1. Immune complexes were tested for autophosphorylation activity in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Part of the anti-C-FGFR1 immunoprecipitates was also immunoblotted with anti-C-FGFR1 and antiphosphotyrosine antibodies to verify for proper expression of the fusion construct and to measure the tyrosine phosphorylation level of the kinase, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2, the FOP-FGFR1 fusion protein was detectable as a band of approximately 74 kDa and was autophosphorylated. We constructed a FOP-FGFR1 mutant in the ATP binding site, K259 to A (K259/A), corresponding to the K514/A substitution in the FGFR1 portion (Fig. 1). The K259/A construct was transfected into NIH 3T3 cells as described above. No autophosphorylation activity was found (Fig. 2). Western blot analysis confirmed the expression of FOP-FGFR1 K259/A and demonstrated that the K259/A mutation abrogated FOP-FGFR1 tyrosine kinase activity (Fig. 2). These results indicate that FOP-FGFR1 has a constitutively activated tyrosine kinase.

FIG. 2.

Autokinase activity and phosphorylation on tyrosine of FOP-FGFR1 fusion protein. The FGFR1 overexpressing cell line, and NIH 3T3 cells transiently transfected with either the empty vector (pcDNA3) or two FOP-FGFR1 cDNAs (wild-type and kinase dead mutant) were treated with (+) or without (−) FGF1 plus heparin. Immunoprecipitates using anti-C-FGFR1 antibody were analyzed for autokinase assay (upper panel), phosphorylation on tyrosine after Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibody (4G10) (medium panel), and expression level by Western blotting with anti-C-FGFR1 antibody (lower panel). The position of molecular mass standards is indicated at left.

PLC-γ1 is associated with FOP-FGFR1 and is constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated.

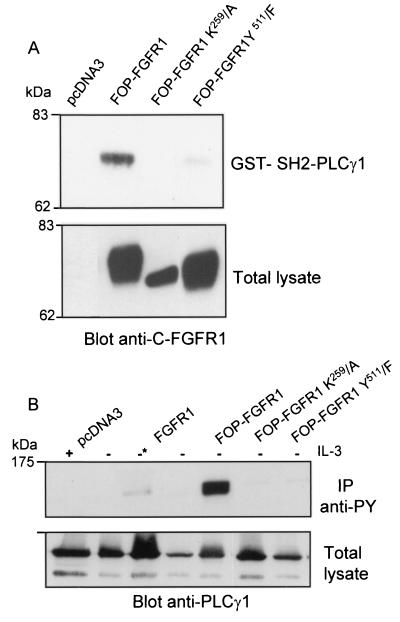

PLC-γ is phosphorylated by activation of the FGFR1 receptor (11) and binds to the Y766 residue in FGFR1 through an SH2 domain interaction (52). To investigate if FOP-FGFR1 activated PLC-γ, we studied PLC-γ association with the fusion protein and the subsequent status of PLC-γ phosphorylation. Cos-1 cell lysates were precipitated with GST-SH2-PLC-γ1, and bound proteins were revealed by immunoblotting with anti-C-FGFR1. As shown in Fig. 3A, the 74-kDa FOP-FGFR1 protein was pulled down from transfected cells, indicating that FOP-FGFR1, like FGFR1, also interacts with PLC-γ through its SH2 domain. A tyrosine-to-phenylalanine substitution at the analogous PLC-γ binding site in the context of FOP-FGFR1 fusion protein (Y511/F) (Fig. 1) dramatically inhibited this interaction. The interaction requires the tyrosine kinase activity since it was completely abolished in the kinase-inactive FOP-FGFR1 mutant (K259/A) (Fig. 3A). PLC-γ was strongly tyrosine phosphorylated in murine Ba/F3 cells transfected by FOP-FGFR1 and cultured without IL-3, as revealed by immunoprecipitation with antiphosphotyrosine and immunoblotting with anti-PLC-γ1 (Fig. 3B). The constitutive PLC-γ phosphorylation was abrogated in the two FOP-FGFR1 mutants despite levels of protein expression comparable to those of FOP-FGFR1. As expected, PLC-γ was phosphorylated in a faint manner with the wild-type FGFR1 upon stimulation with FGF1 (Fig. 3B). These data demonstrated that PLC-γ is associated through its SH2 domain to the constitutively activated FOP-FGFR1. The constitutively phosphorylated tyrosine 511 in FOP-FGFR1 represents the major binding site of PLC-γ.

FIG. 3.

PLC-γ1 binds via its SH2 domain to Y511 site on FOP-FGFR1 fusion receptor in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. (A) Cos-1 cells were transiently transfected with FOP-FGFR1 and its mutants. A pull-down assay was performed on FOP-FGFR1 expressing lysates with the GST-SH2-PLC-γ1. The interaction with FOP-FGFR1 was revealed by anti-C-FGFR1. Proteins in the total cell lysates were detected by Western blotting with anti-C-FGFR1. (B) Ba/F3 cells stably transfected with FGFR1 and FOP-FGFR1 and its mutants were IL-3 starved overnight in medium containing 1% FCS and then stimulated with medium alone with (+) or without (−) IL-3 or in the presence of FGF1 plus heparin (−*) for 10 min at 37°C. The lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitations with antiphosphotyrosine (IP anti-Py). The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with anti-PLC-γ1. The position of molecular mass standards is indicated at left.

FOP-FGFR1 promotes ligand-independent cell survival of Ba/F3 cells via an antiapoptotic effect.

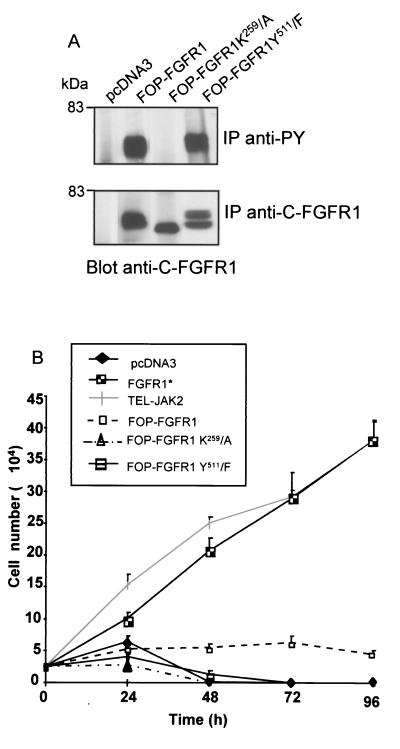

The biological effects of FOP-FGFR1 in transfected Ba/F3 cells were next examined. All FOP-FGFR1 fusion proteins were expressed at similar levels. They were all tyrosine phosphorylated except for the kinase-defective mutant (K259/A) (Fig. 4A). Cells expressing the different constructs were starved of IL-3, and cell survival was monitored over 96 h using the trypan blue dye exclusion assay. The results are shown in Fig. 4B. As expected, FGFR1 and TEL-JAK2, used as controls, were able to promote cell growth (see references 79 and 46, respectively). All (100%) of the cells expressing the vector alone had died by 48 h. In contrast, expression of FOP-FGFR1 prevented cell death, as demonstrated by a constant number of viable cells retrieved within the 96 h of cell culture. Transfectants expressing FOP-FGFR1 K259/A and Y511/F were unable to sustain cell survival in medium lacking IL-3. These results show that constitutive tyrosine kinase activation and interaction with phosphorylated Y511, the binding site of PLC-γ, are both necessary for Ba/F3 cell survival induced by FOP-FGFR1.

FIG. 4.

FOP-FGFR1 promotes ligand-independent cell survival. (A) Mutation of lysine 259 in the ATP binding site abolishes kinase activity of FOP-FGFR1. Antiphosphotyrosine or anti-C-FGFR1 immunoprecipitates from cells expressing FOP-FGFR1 and mutant receptors FOP-FGFR1 K259/A (kinase-defective mutant) and FOP-FGFR1 Y511/F (PLC-γ binding-defective mutant) were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-C-FGFR1 antibody. (B) Ba/F3 cells expressing the various proteins were washed free of IL-3, and 2.5 × 104 cells were plated in triplicate in IL-3-free medium, and viable cells were counted daily (means ± standard deviations [error bars]). Note that Ba/F3 expressing FGFR1 (*) were grown in the presence of FGF1 (10 ng/ml) plus heparin (10 μg/ml).

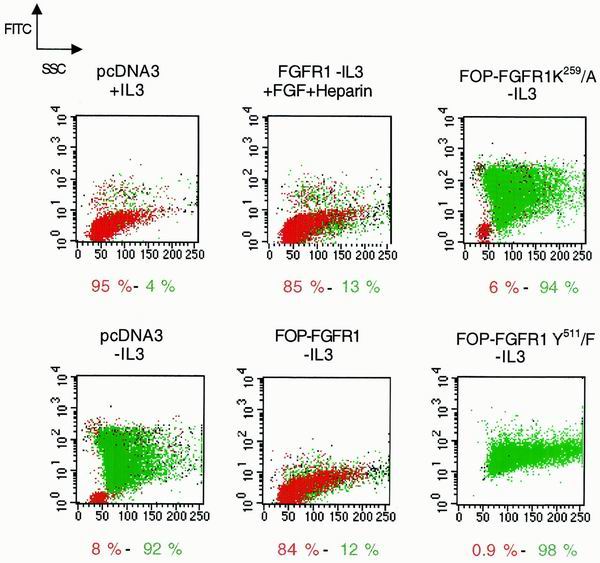

To test whether FOP-FGFR1 can mediate cell survival via an antiapoptotic mechanism, apoptosis was evaluated by TUNEL method. The stably transfected Ba/F3 cell lines were cultured in the presence or absence of IL-3. Cytospins were prepared and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Apoptotic Ba/F3 cells exhibited characteristic morphological changes, including cell shrinkage, presence of apoptotic bodies, and condensation and fragmentation of nuclei. In the presence of IL-3, very rare apoptotic cells were seen, and no variation was found between the different transfected cell lines (data not shown). In contrast, after IL-3 withdrawal, apoptotic cells were more frequent in clones transfected with either vector alone or FOP-FGFR1 mutants compared to FOP-FGFR1-transfected cells. Table 1 shows data of the apoptotic indices after a 24-h culture. A low apoptotic level was found in FOP-FGFR1-transfected cells (13%) compared to the vector alone (58.8%), and to the kinase- and PLC-γ-binding-defective mutants (63.5 and 56.8%, respectively). We did a cell sorter analysis after a 48-h culture and IL-3 withdrawal. As shown in Fig. 5, Ba/F3 cells transfected with the vector alone and deprived of IL-3 lost viability (8% compared to the 95% observed in the presence of IL-3). In contrast, Ba/F3 cells expressing FOP-FGFR1 efficiently resisted the process, with 84% of cells remaining viable, a percentage similar to that observed for FGFR1 cells cultured in the presence of FGF1 plus heparin (85%). Interestingly, neither the K259/A nor the Y511/F FOP-FGFR1 mutant was able to sustain cell survival (6 and 0.9% of viable cells, respectively). These data indicate that the activated FOP-FGFR1 kinase protects Ba/F3 cells from apoptosis upon removal of IL-3 and that the Y511 PLC-γ binding site is necessary for this process.

TABLE 1.

Apoptotic indices in Ba/F3 cells cultured for 24 h

| Construct | Presence of IL-3 | Mean (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| pcDNA 3 | + | 1.33 |

| pcDNA3 | − | 58.8 |

| FOP-FGFR1 | − | 13 |

| FOP-FGFR1 K259/A | − | 63.5 |

| FOP-FGFR1 Y511/F | − | 56.8 |

Indices were calculated after TUNEL apoptotic cell labeling and detection as described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 5.

Antiapoptotic effect of FOP-FGFR1 in Ba/F3-transfected cells as assessed by flow cytometry. Cells were cultured for 48 h in the presence or absence of IL-3 as indicated. Subsequently, DNA of 2 × 106 fixed cells was labeled by the addition of fluorescein dUTP at strand breaks by terminal transferase by using the in situ cell death detection kit as recommended. The percentage of viable (in red) and apoptotic (in green) cells are mentioned.

STAT1 and STAT3 but not STAT5 are activated by FOP-FGFR1.

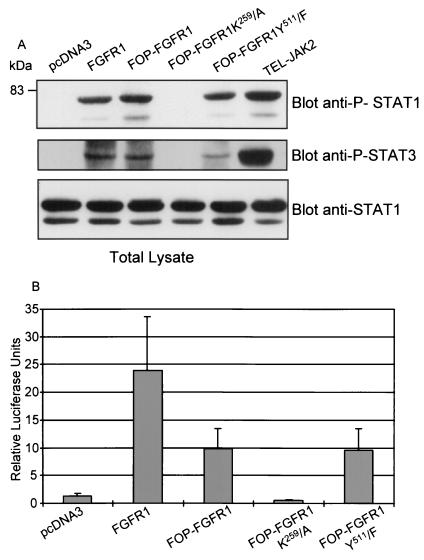

Transient activation of STATs is critical for transmission of cytokine-induced proliferative, differentiation, and survival signals in hematopoietic cell types (see reference 7 for a review). Recently, it was shown that STAT activation by FGFRs is important for the ability of receptors to act as oncogenes (36). To examine whether FOP-FGFR1 is able to activate STAT proteins, lysates of Cos-1 cells expressing FOP-FGFR1 or its mutants were analyzed for the presence of phosphorylated STATs proteins. Expression of FOP-FGFR1 led to phosphorylation of both STAT1 and STAT3 (Fig. 6A). This phosphorylation was abrogated when kinase-defective FOP-FGFR1 was expressed. In contrast, no phosphorylation of STAT5 was observed in Cos-1 cells expressing either FGFR1 or FOP-FGFR1 wild-type and mutants while a strong phosphorylation was observed in TEL-JAK2 cells used as controls (data not shown). Similar results were obtained in Ba/F3 cells. This demonstrates that FOP-FGFR1 activates STAT1 and STAT3 but not STAT5. Consistent with the activation of STAT1 and STAT3 by FOP-FGFR1 and FGFR1, we observed an induction of a STAT1/3-responsive reporter construct following cotransfections in NIH 3T3 cells (Fig. 6B): about 20-fold induction by FGFR1 and 8-fold induction by FOP-FGFR1 or its PLC-γ-binding-defective mutant. As expected, FOP-FGFR1 K259/A did not induce a STAT-responsive luciferase activity.

FIG. 6.

Activation of STAT1 and STAT3 by FOP-FGFR1 and its PLC-γ-binding-defective mutant. (A) Lysates of Cos-1 cells expressing various proteins as indicated were analyzed by Western blotting using phospho-STAT1 or Phospho-STAT3 antisera. Stripping and reprobing the blot with anti-STAT1 antibody confirmed that the protein amounts are equivalent in each sample. (B) NIH 3T3 cells were cotransfected with the STAT-responsive reporter construct 4×StRE-luciferase, pRL-TK Renilla luciferase control reporter vector, and either FOP-FGFR1 or its mutants or FGFR1 wild-type, or the empty (pcDNA3) vectors and subjected to a dual luciferase reporter assay. Luciferase activity was determined as described in Materials and Methods. The values were normalized with respect to that of pRL-TK Renilla luciferase in each cell line. Each column represents the average of three independent experiments, with the positive standard deviation indicated as an error bar.

FOP-FGFR1 constitutively activates the MAPK pathway.

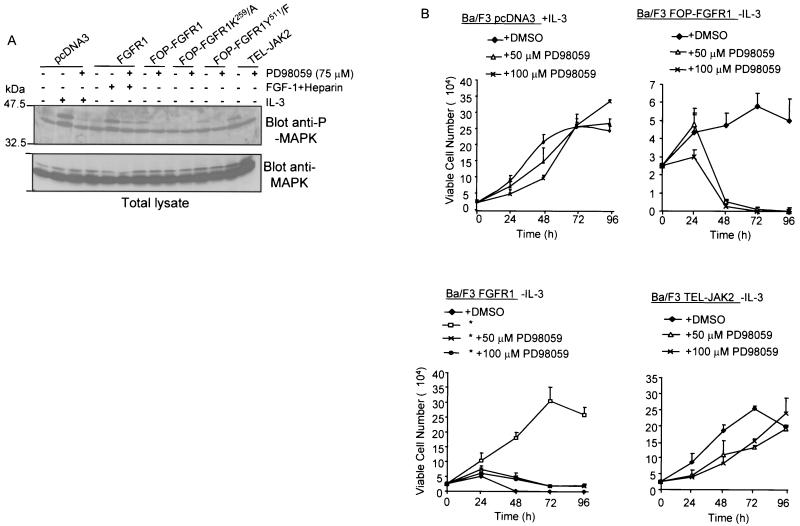

FGFRs are known to couple the MAPK pathway via the adaptor molecule GRB2 (42, 44). FGFR stimulation leads to the association of the GRB2-SOS complex with either FRS2/SNT (whose binding sites are absent in the FOP-FGFR1 fusion protein), or the adaptor protein SHC. We thus explored the possibility that FOP-FGFR1 might cause cell survival through constitutive activation of the MAP kinase pathway. MAPK is phosphorylated in FOP-FGFR1 cells after IL-3 withdrawal. This effect requires the tyrosine kinase activity of FOP-FGFR1 since the kinase-inactive mutant (K259/A) failed to induce the phosphorylation of MAPK (Fig. 7A). Of note, FOP-FGFR1 appeared to be a less potent activator of the MAPK pathway than either FGFR1 or TEL-JAK2 used as controls. Immunoblot analysis revealed equivalent amounts of MAPK in all samples (Fig. 7A, bottom panel). MAPK activation was inhibited after addition of the MAPK kinase (MEK) specific inhibitor PD98059.

FIG. 7.

Effect of PD98059 treatment on the MAPK signaling and survival of Ba/F3 cells transfected with FGFR1 or FOP-FGFR1 and its mutants. (A) After IL-3 starvation and culture in medium containing 1% FCS, cells expressing the various proteins were incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of PD98059 as indicated for 30 min (cells transfected with the vector alone or with FGFR1 were stimulated for 5 min with IL-3 or FGF1 plus heparin, respectively). Cell extracts were then prepared and analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-phospho-MAPK (upper panel) or with an anti-MAPK, the latter demonstrating equivalent loading in each row. (B) PD98059 completely abolishes the cell survival induced by FOP-FGFR1. Ba/F3 cells expressing the various proteins were washed free of IL-3, and 2.5 × 104 cells were plated in triplicate in IL-3 free medium (except for cells transfected with the vector alone) in the absence (DMSO) or presence of PD98059 (50 or 100 μM), and viable cells were counted over a 96-h period (means ± standard deviations [error bars]) of three independent experiments. Note that Ba/F3 expressing FGFR1 (∗) were grown in the presence of FGF1 (10 ng/ml) plus heparin (10 μg/ml). Ba/F3 cells expressing TEL-JAK2 were used as a control.

We then analyzed the effects of PD98059 on the viability of transfected Ba/F3 monitored over 96 h using the trypan blue dye exclusion assay. In the presence of IL-3, incubation of Ba/F3 cells with PD98059 (50 to 100 μM) did not show any cytotoxicity (Fig. 7B, upper left panel). This inhibitor dramatically reduced the viability of FOP-FGFR1 Ba/F3 cells since no viable cells were observed in cultures treated for 72 h (Fig. 7B, upper right panel). Similarly, a low number of viable cells were obtained in the FGFR1-transfected cells treated with PD98059 (Fig. 7B, lower left panel). On the contrary, PD98059 had no effect on the viability of TEL-JAK2 Ba/F3 used as a control (Fig. 7B, lower right panel). Similar results were obtained with U0126, another specific inhibitor of MEK1 and MEK2, two members of the MEK family (25) (data not shown).

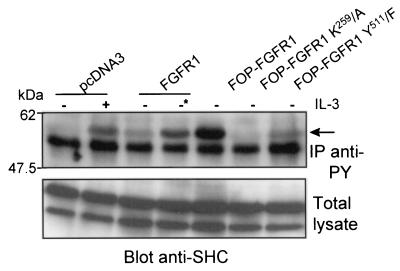

A pull-down assay with GST-PTB-SHC on total lysates derived from transfected Cos-1 cells and detected by immunoblotting with anti-C-FGFR1 antibody precipitated FOP-FGFR1, PLC-γ-defective FOP-FGFR1, and wild-type FGFR1 but not kinase-defective FOP-FGFR1 mutant (see Fig. 9A, lower panel). Similar results were obtained from a pull-down assay with a GST-GRB2 (data not shown). In Ba/F3 cell line expressing FOP-FGFR1, SHC was tyrosine phosphorylated (Fig. 8). SHC was only activated in Ba/F3 cells transfected with either the vector alone or with the wild-type FGFR1 upon stimulation with IL-3 or FGF1 plus heparin, respectively. No SHC activation was observed for the two FOP-FGFR1 (K259/A and Y511/F) mutants. Taken together, these data suggest that the activation of MEK/MAPK, which is known to be relevant to the mitogenic pathway for wild-type FGFR1, is also required to promote survival of FOP-FGFR1 Ba/F3 cells.

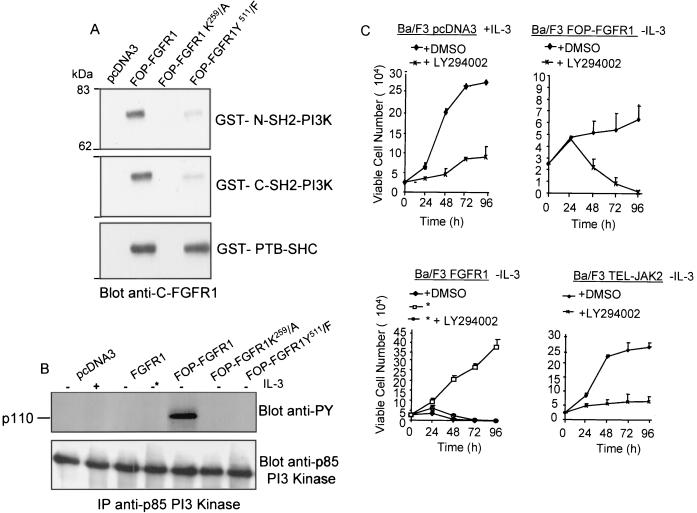

FIG. 9.

FOP-FGFR1 confers a survival signal to Ba/F3 cells in a Pl3K dependent manner. (A) FOP-FGFR1 interacts with Pl3K and SHC; the kinase-defective mutant (K259) abolishes these interactions whereas interaction with SHC is not affected by the PLC-γ-binding-defective (Y511) FOP-FGFR1 mutant. Pull-down assays were performed on Cos-1 cells expressing FOP-FGFR1 and its mutants with GST-Pl3K (GST p85-SH2 Pl3K [C or N-terminal]) or GST-PTB-SHC. The interactions were revealed by anti-C-FGFR1. (B) p110 subunit of Pl3K is tyrosine phosphorylated in FOP-FGFR1-expressing Ba/F3 cells. After lysis, proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-p85 Pl3K, and the phosphorylated catalytic p110 subunit of Pl3K was revealed with the 4G10 antiphosphotyrosine (anti-Py) antibody. Equivalent amount of proteins were evidenced by reprobing the blot with anti-p85 Pl3K antibody. (C) The Pl3K inhibitor LY294002 abolishes the cytokine-independent cell survival of FOP-FGFR1 expressing cells. Ba/F3 cells (2.5 × 106) were seeded in triplicate and cultured with the LY294002 inhibitor at a concentration of 0.0 (DMSO alone) or 10 μM in the absence of IL-3 (except for Ba/F3 cells transfected with the empty vector, pcDNA3). The number of viable cells was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion at over 96 h. Note that FGFR1-expressing cells were cultured in the presence of FGF1 plus heparin (∗).

FIG. 8.

SHC phosphorylation induced by FOP-FGFR1 expressing cells. Ba/F3 cells were grown overnight in medium without IL-3 and with 1% FCS. Cell lysates were then immunoprecipitated with the 4G10 antiphosphotyrosine antibody (IP anti-Py), and SHC phosphorylation was visualized with anti-SHC antibody (arrow). As a control, starved Ba/F3 cells transfected with the vector alone stimulated with IL-3 for 5 min restored phosphorylation of SHC. Anti-SHC immunoblotting of total lysates showed similar amounts of proteins loaded in each sample. Ba/F3 cells expressing FGFR1 (∗) were grown in the presence of FGF1 (10 ng/ml) plus heparin (10 μg/ml).

FOP-FGFR1 activates the PI3K signaling cascade.

The majority of tyrosine kinase receptors can activate PI3K (83). This activation has been shown to promote cytokine-dependent cell proliferation through its own cascade and specific downstream targets such as AKT (19, 56). We hypothesized that FOP-FGFR1 might cause cell survival in part through PI3K constitutive activation. We demonstrated that PI3K is associated with the activated FOP-FGFR1 as shown in pull-down assays using the GST-p85-SH2 domain and immunoblotting with anti-C-FGFR1 antibody (Fig. 9A). In IL-3-dependent Ba/F3 cells, the regulatory p85 subunit of class IA PI3K interacts with the p110α catalytic subunit (22, 35). The p110 subunit of PI3K was assayed for tyrosine phosphorylation in transformed Ba/F3 cells. For this purpose, immunoprecipitations were done with anti-p85 PI3K and revealed using antiphosphotyrosine antibody. Figure 9B (upper panel) shows tyrosine phosphorylation of the catalytic subunit p110 exclusively in FOP-FGFR1-transformed cells despite levels of protein expression comparable in all immunoprecipitates (Fig. 9B, lower panel).

Survival of Ba/F3 cells transfected with FOP-FGFR1 and cultured in the absence of IL-3 was completely inhibited by the PI3K inhibitors LY294002 (10 μM [Fig. 9C, upper right panel]) and wortmannin (1 μM [data not shown]). Similar results were obtained with FGFR1-transfected cells, even in the presence of FGF1 and heparin (Fig. 9C, lower left panel). As expected, LY294002 and wortmannin impaired the IL-3-dependent proliferation of Ba/F3 cells transfected with either the vector alone or TEL-JAK2 (Fig. 9C, upper left and lower right panels, respectively).

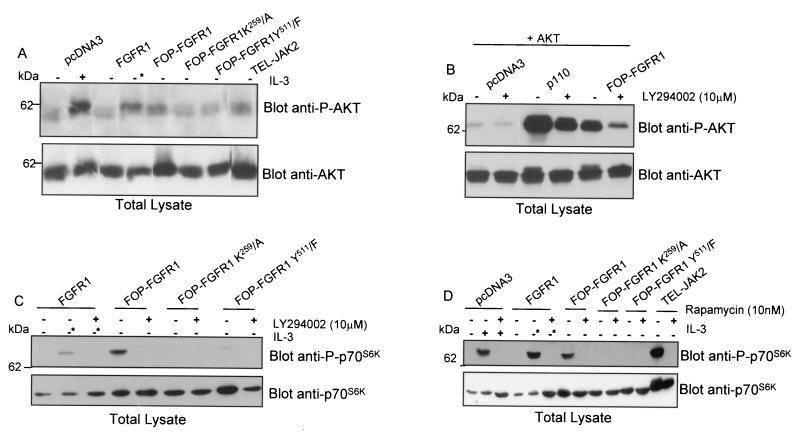

AKT proteins are general mediators of survival signals and downstream components of the PI3K signaling pathway. The phosphorylation of AKT is tightly associated with its activation (10, 20). We therefore examined whether PI3K activation by FOP-FGFR1 was followed by activation of AKT by immunoblotting with an antibody specific for AKT phosphorylated at Ser473 (P-AKT), which represents the activated state of AKT (1, 24). Indeed, AKT was found activated by FOP-FGFR1, whereas the kinase-defective and the PLC-γ-binding-defective FOP-FGFR1 mutants failed to stimulate the phosphorylation of AKT (Fig. 10A). These data clearly show that AKT is constitutively activated in FOP-FGFR1-transfected cells. A marked difference in AKT phosphorylation was also detected in control vector and FGFR1-transfected cells cultured in the presence of growth factors. Activation of AKT was dramatically reduced by PI3K inhibitors; similar results were obtained in Cos-1 cells cotransfected with a hemagglutinin-AKT plasmid (Fig. 10B). AKT phosphorylation shift is clearly observed in FOP-FGFR1 expressing cells as well as in p110-transfected cells used as a control (Fig. 10B, lower panel). This result is consistent with the finding that LY294002 abolished cell viability as demonstrated in Fig. 9C. Taken together, these results demonstrate that FOP-FGFR1 is capable of protecting cells from apoptosis by signaling mainly through the PI3K/AKT pathway.

FIG. 10.

Antiapoptotic effect of FOP-FGFR1 via AKT and p70s6k. (A) AKT is constitutively phosphorylated in Ba/F3 cells expressing FOP-FGFR1. Cells transfected as indicated were deprived of IL-3 overnight in the presence of FCS 1%, lysed, and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phosphorylated AKT (anti-P-AKT) (upper panel) or anti-AKT (lower panel). AKT phosphorylation is increased in cells expressing FOP-FGFR1 as well as in cells expressing FGFR1 (cultured in the presence of FGF1 plus heparin [*]) and TEL-JAK2 used as controls. IL-3-starved Ba/F3 cells transfected with the vector alone and stimulated with IL-3 for 5 min showed increased phosphorylation of AKT. Equivalent amounts of proteins in each sample were revealed using anti-AKT antibody. (B) Cos-1 cells were transiently cotransfected with pSG5-PKB (containing the full-length AKT cDNA) and either FOP-FGFR1 or rCD2p110 (p110 catalytic subunit of Pl3K) used as a control. Cells were cultured in the presence (+) or absence (−) of LY294002 for 30 min and analyzed by western blotting with anti-phosphorylated AKT (upper panel) or anti-AKT (lower panel). (C) and (D) Ba/F3 cells were cultured under the same conditions as described in (A) in the presence or absence of LY294002 (C) and rapamycin (D), and analyzed by western blotting with phosphorylated p70S6K (Thr389) (upper panel) or p70s6k antibodies.

Recently, it has become clear that some of the transforming effects induced by PI3K and AKT activation are relayed by the downstream mTOR/p70S6K pathway (3). We thus examined the phosphorylation of p70S6K in Western blots using a phospho-p70S6K (Thr389)-specific antibody (Fig. 10C and D). Addition of IL-3 and FGF1 induced a stimulation of p70S6K phosphorylation in Ba/F3 cells transfected by either the empty vector or FGFR1. In contrast, FOP-FGFR1-expressing cells showed phosphorylation of threonine 389 in the absence of stimulation, suggesting that p70S6K is constitutively activated in the transformed cells. On the contrary, both the kinase-defective and the PLC-γ-binding-defective FOP-FGFR1 mutants failed to stimulate the phosphorylation of p70S6K. p70S6K phosphorylation was PI3K dependent as it was completely abolished by the addition of LY294002 (Fig. 10C). The phosphorylation of p70S6K is known to be rapamycin sensitive (40, 60, 63). As shown in Fig. 10D, rapamycin also completely abolished the phosphorylation of p70S6K. In addition, FOP-FGFR1-induced survival of Ba/F3 cells was completely inhibited by rapamycin (data not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrate that FOP-FGFR1 is capable of protecting cells from apoptosis in a PI3K/mTOR-dependent manner.

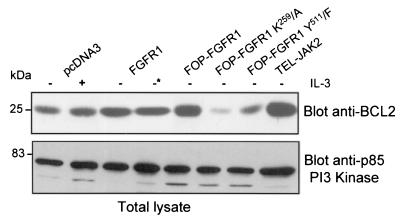

FOP-FGFR1 protects cells from apoptosis via BCL2 activation and caspase-9 inactivation.

Since FOP-FGFR1 can replace the IL-3 requirement for survival of Ba/F3 cells through an antiapoptotic effect, we asked if FOP-FGFR1 led to deregulation of BCL2 expression, which has been shown to extend the survival of IL-3-dependent hematopoietic cell line (34, 39). For this purpose, immunoblot analysis was used. There was a significant increase of the amount of BCL2 in FOP-FGFR1-expressing cells compared to Ba/F3 expressing the vector alone or FGFR1 wild-type and cultured in the presence of IL-3, and FGF1 plus heparin, respectively (Fig. 11). This overexpression of BCL2 requires the tyrosine kinase and the Y511 PLC-γ binding activities of FOP-FGFR1 since only a basal amount of BCL2 was observed in both mutants. These results suggest that the antiapoptotic effects of FOP-FGFR1 involve the up-regulation of BCL2.

FIG. 11.

Antiapoptotic effect of FOP-FGFR1 via BCL2 activation. Ba/F3 cells were cultured as described in the legend to Fig. 10A. Western blots were successively probed with anti-BCL2 and anti-p85-Pl3K, the latter for controlling protein amounts.

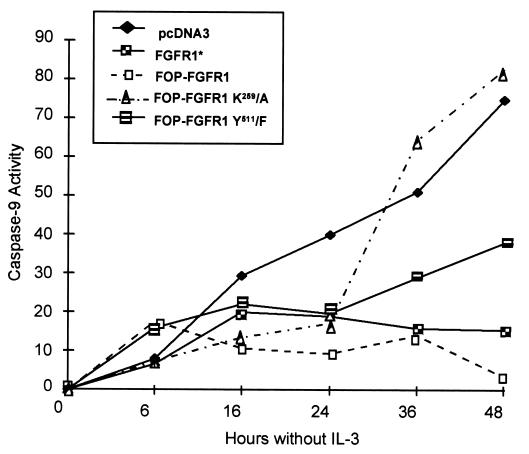

A central effect in the apoptotic process is the activation of a specific set of caspases. They are intracellular proteases that function as initiators or effectors of apoptosis. We have examined the activity of caspase-9, an upstream proenzyme in the cascade of enzymatic reactions required to induce cellular apoptosis (25, 74). For this purpose, the enzymatic activity of caspase-9 was measured by a colorimetric assay over a 48-h period after IL-3 withdrawal. As seen in Fig. 12, the cells expressing FOP-FGFR1 had a very low enzymatic activity compared to the control Ba/F3 cells and the kinase-defective FOP-FGFR1 (a 22- and 24-fold decrease, respectively). Conversely, in PLC-γ-binding-defective FOP-FGFR1, there was at least an 11-fold increase of caspase-9 activity compared to FOP-FGFR1. Cells expressing FGFR1 and cultured in the presence of FGF1 showed a weak impaired caspase-9 activity (fivefold decrease compared to pcDNA3). Taken together, these results confirm and extend the finding that, in hematopoietic cells, the constitutively activated fusion protein FOP-FGFR1 promotes cell survival via a caspase-dependent antiapoptotic effect.

FIG. 12.

Inactivation of caspase-9 in Ba/F3 cells expressing FOP-FGFR1 after IL-3 withdrawal. Cells stably transfected as indicated were cultured in the absence of IL-3 for 0 to 48 h. At 0, 6, 16, 24, 36, and 48 h, cells were harvested and lysed, and an enzymatic reaction for caspase-9 activity using a colorimetric assay was carried out. Caspase-9 activity of total cellular protein is plotted versus the incubation time after IL-3 withdrawal. This is a representative experiment of two experiments.

DISCUSSION

Tyrosine kinase serves as a growth factor receptor or intracellular signal transducer and can be aberrantly activated through a variety of mechanisms (70). In hematopoietic cells, a common mechanism for activation of tyrosine kinase is the occurrence of fusion products as a consequence of balanced translocations (51). Similarly, activated and overexpressed tyrosine kinases have been reported in association with solid cancers, especially FGFRs and their ligands, which play a major role in cancers of the stomach, breast, thyroid, prostate, and pancreas. We recently found FGFR1 amplified and overexpressed in breast cancers (77).

FOP-FGFR1 is the fusion product of the t(6;8) translocation associated with a stem cell leukemia-lymphoma syndrome in which both lymphoblastic lymphoma and acute myelogenous leukemia develop in patients (65). Understanding the mechanisms leading to this syndrome could provide information on the biology of the hematopoietic stem cell itself. In this study we have shown that the FGFR1 aberrant tyrosine kinase is constitutively phosphorylated and transforms Ba/F3 cells to IL-3-independent cell survival via an antiapoptotic effect. Mutation of the ATP binding site in the catalytic domain of the fusion protein abrogates activation and cell survival. Cell survival induced by FOP-FGFR1 is also abrogated by mutation of the PLC-γ-binding site. Experiments described here also show that the constitutively activated FOP-FGFR1 tyrosine kinase utilizes cooperation between effector proteins, including STAT1 and STAT3, PLC-γ, MAPK, PI3K, and mTOR/p70S6K, to facilitate signal transduction and promote cell survival.

In addition to the roles of STAT proteins in normal cell signaling, recent studies have demonstrated that diverse oncoproteins can activate specific STATs and that constitutively activated STAT signaling directly contributes to oncogenesis (7, 8). While STAT activation is a common characteristic of leukemias, the specific patterns of activated STATs and the manner by which STAT activation occurs vary with each disease (49). FOP-FGFR1 stimulates phosphorylation and activation of STAT1 and STAT3. Recently, Hart et al. (36) showed that FGFR derivatives which contain the same deletion of the extracellular domain of FGFR1 as FOP-FGFR1 were capable of inducing morphological transformation and differentiation of PC12 cells and stimulating phosphorylation and activation of STAT1 and STAT3. Constitutive activation of STAT1 and STAT3 are also found in Epstein-Barr virus-related lymphoma cells (81), in Burkitt lymphomas, and in multiple myeloma (8). STAT3 activation plays an important role in preventing apoptosis (26, 31). Ectopic expression of FGFR3 as a result of the t(4;14) translocation promotes myeloma cell proliferation and prevents apoptosis via increased phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT3 and higher levels of BCLXI (62). These observations are relevant given the fact that STAT1 and STAT3 are constitutively activated by FOP-FGFR1, which induces an antiapoptotic effect. In striking contrast to a broad spectrum of tyrosine kinase fusions associated with hematological malignancy, including BCR-ABL, TEL-JAK2, and TEL-PDGFRβ, we found that FOP-FGFR1 did not activate STAT5. Thus, FOP-FGFR1 represents the second evidence of nonactivation of STAT5 by a tyrosine kinase fusion protein. Indeed, a recent study showed that TEL-TRKC-mediated transformation of Ba/F3 and development of myeloproliferative disorder do not require activation of STAT5 (50). Most significantly, STAT5 activation does not play a necessary role in spite of its activation in the disease induction caused by BCR-ABL or v-ABL (48). The significance of activation of specific STAT awaits the elucidation of target genes specific to FOP-FGFR1-mediated survival. In particular STAT3, whose activation is controlled by mTOR (71, 87), is persistently activated in many human cancers and causes cellular transformation (9).

Our results establish that the MAPK pathway is critical for the transformation of the bone marrow-derived Ba/F3 cell line by FOP-FGFR1. In normal and transfected cells, FGF-mediated FGFR activation results in a strong activation of the MAPK cascade by means of the recruitment of the GRB2-SOS complex to the plasma membrane via phosphorylation of the docking proteins SHC and FRS2/SNT (44, 47, 58, 69, 86). The specific sites for FRS2 binding within the FGFR juxtamembrane portion are deleted in the fusion protein FOP-FGFR1, and we have shown that FOP-FGFR1 is associated with SHC that is tyrosine phosphorylated. This resulted in reduced MAPK phosphorylation. As a consequence, FOP-FGFR1 is a less potent activator of MAPK than FGFR1. In addition, we showed that the MEK specific inhibitors induced complete inhibition of MAP kinase activation as well as cell survival triggered by FOP-FGFR1 in the absence of ligand, contrary to the wild-type FGFR1 for which an incomplete inhibition was found in response to FGF1 stimulation (this work and reference 58). In agreement with other studies (52, 53) on the FGFR1 autophosphorylation roles in signaling, we have shown that tyrosine 511 of FOP-FGFR1, the binding site for the SH2 domain of PLC-γ (Y766 in the wild-type FGFR1), is not required for the activation of MAPK pathway.

In addition to the MAPK cascade, the PI3K pathway must also be active for FOP-FGFR1 to exert its survival effect. The involvement of PI3K in cell transformation has been demonstrated in several cell lines (2, 4, 54). PI3K plays an important role in regulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis. In addition, constitutive PI3K activity has been observed in cancerous cells and, therefore, may contribute to the malignant transformation of cells. PI3K is involved in signal transduction downstream of most tyrosine kinases (38). The FGFRs lack optimal binding motifs for the PI3K and FGF-induced PI3K activity is difficult to detect in vitro (43). PI3K is constitutively activated through an unknown mechanism in FOP-FGFR1-expressing Ba/F3 cells. LY294002 and wortmannin completely abolished the survival of FOP-FGFR1-expressing Ba/F3 cells. Moreover, recent studies showed that cytokine receptors lacking direct PI3 kinase binding sites activate AKT via PI3K pathway, thereby regulating cell survival/or proliferation (32). Several studies have recently established a link between the PI3K/AKT pathway and human cancers via defects in PTEN (reviewed in reference 13). In addition, SHC, which is recruited by the fusion protein, might be required for PI3K activation in FOP-FGFR1 as well.

PI3K, AKT, and their downstream effectors mTOR and p70S6K have recently emerged as components of a major signaling pathway that is dedicated to cell growth and survival via protein translation (6, 76). mTOR appears to be an obligatory mediator of the oncogenic signal issued by PI3K or AKT (3). Although the complete target spectrum of mTOR remains to be determined, it is clear that mTOR functions as an important regulator of translation (3, 30). For the first time the data presented here point to a deregulated PI3K/AKT and mTOR/p70S6K signaling induced by an aberrant tyrosine kinase fusion protein.

Mutation in the binding site of PLC-γ of FOP-FGFR1 (Y511 equivalent of Y766 in the FGFR1 sequence) abrogates the phosphorylation of PLC-γ, PI3K, and p70S6K. This observation shows the importance of this autophosphorylating site, which may constitute a multidocking site for effector proteins in FOP-FGFR1 mediated cell survival. The importance of the multifunctional docking site of the MET receptor tyrosine kinase in mediating several cellular responses has been demonstrated (29, 75). Signaling via growth factor frequently results in the concomitant activation of PLC-γ and PI3K. A cross talk scenario between PLC-γ and PI3K was described recently to activate growth factor receptors following stimulation (27), thus revealing intricated signaling pathways. It has been suggested that PI3K may act as an intermediate in the activation of the MAPK cascade in erythroid progenitors (41). Finally, the ability of different kinase cascades to independently protect hematopoietic cells from apoptosis was recently demonstrated (61). With regards to antiapoptotic signaling via the IL-3 receptor, both PI3K and activation of the MAP signaling pathway appear to be important in Ba/F3 cells (16). Our results strongly suggest that FOP-FGFR1 activates the same signaling pathways as IL-3 in generating antiapoptotic signals.

In hematopoietic cells, multiple receptors are able to prevent apoptosis via the activation of PI3K. AKT is a downstream component of the PI3K pathway, and its phosphorylation is tightly associated with its activation (10, 20). We showed that activation of the antiapoptotic mediator AKT by FOP-FGFR1 was abrogated by wortmannin and LY294002, indicating that FOP-FGFR1 activates AKT in a PI3K-dependent manner. Recently, AKT was found to phosphorylate procaspase-9 and to inhibit its protease activity, thus promoting cell survival (15). Our results show that caspase-9 is inactivated in FOP-FGFR1-expressing cells, strongly suggesting that the antiapoptotic effect elicited by FOP-FGFR1 is related to the caspase cascade. In addition, the analysis of a more general indicator of cell viability, i.e., BCL2, showed higher expression in FOP-FGFR1-expressing cells than in other transfectants. Suppression of apoptosis induced by growth factor withdrawal was recently reported by an oncogenic form of c-CBL by a mechanism that involves the overexpression of BCL2 (34). Overexpression of BCL2 has also been associated with late myelodysplastic syndrome types or progression to overt leukemia (21). It will be interesting to see whether the BCL2 overexpression response is under the control of the PI3K/mTOR pathway.

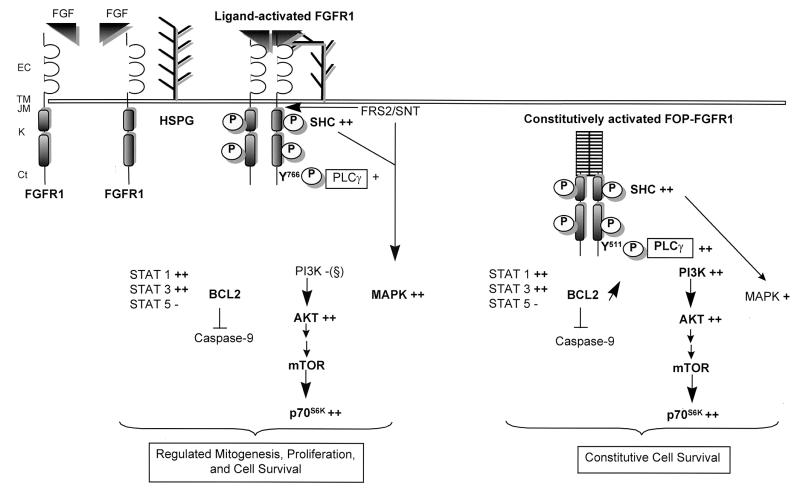

In conclusion, FOP-FGFR1 main activity is the promotion of cell survival through connection with intricated signaling pathways (Fig. 13). Importantly, our results with FOP-FGFR1 establish that constitutive activation of the MAPK and PI3K pathways can contribute to the neoplastic state. The characterization of the effects of FOP-FGFR1 on murine hematopoietic stem cells should illuminate the critical signaling pathways and should orientate the development of drugs for the myeloproliferative disorder treatment.

FIG. 13.

Schematic representation of signal transduction molecules interacting with FOP-FGFR1 compared to wild-type FGFR1. Both PLC-γ and MAPK are recruited to activated FGFR1 following FGF stimulation. In addition, whereas Pl3K was not detected, AKT was activated. The downstream effector of AKT, i.e., mTOR that controls the mammalian translation machinery via activation of the p70s6k protein kinase, is also activated in response to growth factor. This leads to a regulated mitogenesis, proliferation, and cell survival. In contrast, FOP-FGFR1 utilizes cooperation between PLC-γ and Pl3K, and to a lesser extent, MAPK, leading to constitutive cell survival. In bold face type are indicated the major changes between FGFR1 and FOP-FGFR1 signalling pathways. Y511 in the FOP-FGFR1 sequence correspond to Y766 in the FGFR1 sequence. Symbols for phosphorylation status of different components: −, no phosphorylation; +, weak phosphorylation; ++, strong phosphorylation. Abbreviations: EC, extracellular domain; TM, transmembrane domain; JM, juxtamembrane domain; K, kinase domain; Ct, C-terminal tail. (§), FGFR1 lacking optimal binding motifs for Pl3K and no phosphorylation of Pl3K was detected, in agreement with other works (43).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to V. Lacronique and O. Bernard for the kind gift of the TEL-JAK2 construct and for helpful discussions. We thank B. M. Burgering, D. A. Cantrell, D. Donoghue, B. Margolis, R. Rottapel, and M. Waterfield for providing reagents and J. Nunès, C. Popovici, and P. De Sepulveda for helpful discussions and comments. We gratefully acknowledge R. Galindo, D. Isnardon, and R. Castellano for kind help in flow cytometry, confocal, and luciferase analyses, respectively.

This work was supported in part by INSERM and grants from the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, the Ligue National contre le Cancer, and the Fondation de France (comité contre la Leucémie). G.G. was a recipient of a fellowship from the MESR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alessi D R, Andjelkovic M, Caudwell B, Cron P, Morrice N, Cohen P, Hemmings B A. Mechanism of activation of protein kinase B by insulin and IGF-1. EMBO J. 1996;15:6541–6551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amundadottir L T, Leder P. Signal transduction pathways activated and required for mammary carcinogenesis in response to specific oncogenes. Oncogene. 1998;16:737–746. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aoki M, Blazek K, Vogt P K. A role of the kinase mTOR in cellular transformation induced by the oncoproteins P3k and Akt. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:136–141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011528498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bao H, Jacobs-Helber S M, Lawson A E, Penta K, Wickrema A, Sawyer S T. Protein kinase B (c-Akt), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and STAT5 are activated by erythropoietin (EPO) in HCD57 erythroid cells but are constitutively active in an EPO-independent, apoptosis-resistant subclone (HCD57-SREI cells) Blood. 1999;93:3757–3773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellot F, Crumley G, Kaplow J M, Schlessinger J, Jaye M, Dionne C A. Ligand induced transphosphorylation between different FGF receptors. EMBO J. 1991;10:2849–2854. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blume-Jensen P, Hunter T. Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature. 2001;411:355–365. doi: 10.1038/35077225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowman T, Garcia R, Turkson J, Jove R. STATs in oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2000;19:2474–2488. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bromberg J. Signal transducers and activators of transcription as regulators of growth, apoptosis and breast development. Breast Cancer Res. 2001;2:86–90. doi: 10.1186/bcr38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bromberg J F, Wrzeszczynska M H, Devgan G, Zhao Y, Pestell R G, Albanese C, Darnell J E., Jr Stat3 as an oncogene. Cell. 1999;98:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burgering B M, Coffer P J. Protein kinase B (c-Akt) in phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase signal transduction. Nature. 1995;376:599–602. doi: 10.1038/376599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgess W H, Dionne C A, Kaplow J, Mudd R, Friesel R, Zilberstein A, Schlessinger J, Jaye M. Characterization and cDNA cloning of phospholipase C-gamma, a major substrate for heparin-binding growth factor 1 (acidic fibroblast growth factor)-activated tyrosine kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4770–4777. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.9.4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke D, Wilkes D, Blundell T L, Malcolm S. Fibroblast growth factor receptors: lessons from the genes. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:59–62. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantley L C, Neel B G. New insights into tumor suppression: PTEN suppresses tumor formation by restraining the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4240–4245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cappellen D, De Oliveira C, Ricol D, de Medina S, Bourdin J, Sastre-Garau X, Chopin D, Thiery J P, Radvanyi F. Frequent activating mutations of FGFR3 in human bladder and cervix carcinomas. Nat Genet. 1999;23:18–20. doi: 10.1038/12615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cardone M H, Roy N, Stennicke H R, Salvesen G S, Franke T F, Stanbridge E, Frisch S, Reed J C. Regulation of cell death protease caspase-9 by phosphorylation. Science. 1998;282:1318–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaffanet M, Popovici C, Leroux D, Jacrot M, Adélaïde J, Dastugue N, Grégoire M-J, Hagemeijer A, Lafage-Pochitaloff M, Birnbaum D, Pébusque M-J. t(6;8), t(8;9) and t(8;13) translocations associated with stem cell myeloproliferative disorders have close or identical breakpoints in chromosome region 8p11–12. Oncogene. 1998;19:945–949. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chesi M, Nardini E, Brents L A, Schrock E, Ried T, Kuehl W M, Bergsagel P L. Frequent translocation t(4;14)(p16.3;q32.3) in multiple myeloma is associated with increased expression and activating mutations of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Nat Genet. 1997;16:260–264. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chesi M, Brents L A, Ely S A, Bais C, Robbiani D F, Mesri E A, Kuehl W M, Bergsagel P L. Activated fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 is an oncogene that contributes to tumor progression in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2001;97:729–736. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Craddock B L, Orchiston E A, Hinton H J, Welham M J. Dissociation of apoptosis from proliferation, protein kinase B activation, and BAD phosphorylation in interleukin-3-mediated phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10633–10640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Datta S R, Brunet A, Greenberg M E. Cellular survival: a play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2905–2927. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis R E, Greenberg P L. Bcl-2 expression by myeloid precursors in myelodysplastic syndromes: relation to disease progression. Leuk Res. 1998;22:767–777. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(98)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhand R, Hara K, Hiles I, Bax B, Gout I, Panayotou G, Fry M J, Yonezawa K, Kasuga M, Waterfield M D. Pl 3-kinase: structural and functional analysis of intersubunit interactions. EMBO J. 1994;13:511–521. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dionne C A, Crumley G, Bellot F, Kaplow J M, Searfoss G, Ruta M, Burgess W H, Jaye M, Schlessinger J. Cloning and expression of two distinct high-affinity receptors cross-reacting with acidic and basic fibroblast growth factors. EMBO J. 1990;9:2685–2692. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07454.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Downward J. Mechanisms and consequences of activation of protein kinase B/Akt. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:262–267. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duan H, Orth K, Chinnaiyan A M, Poirier G G, Froelich C J, He W W, Dixit V M. ICE-LAP6, a novel member of the ICE/Ced-3 gene family, is activated by the cytotoxic T cell protease granzyme B. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16720–16724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epling-Burnette P K, Liu J H, Catlett-Falcone R, Turkson J, Oshiro M, Kothapalli R, Li Y, Wang J M, Yang-Yen H F, Karras J, Jove R, Loughran T P. Inhibition of STAT3 signaling leads to apoptosis of leukemic large granular lymphocytes and decreased Mcl-1 expression. J Clin Investig. 2001;107:351–362. doi: 10.1172/JCI9940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falasca M, Logan S K, Lehto V P, Baccante G, Lemmon M A, Schlessinger J. Activation of phospholipase C gamma by Pl 3-kinase-induced PH domain-mediated membrane targeting. EMBO J. 1998;17:414–422. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Favata M F, Horiuchi K Y, Manos E J, Daulerio A J, Stradley D A, Feeser W S, Van Dyk D E, Pitts W J, Earl R A, Hobbs F, Copeland R A, Magolda R L, Scherle P A, Trzaskos J M. Identification of a novel inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18623–18632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furge K A, Zhang Y W, Vande Woude G F. Met receptor tyrosine kinase: enhanced signaling through adapter proteins. Oncogene. 2000;19:5582–5589. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gingras A C, Raught B, Sonenberg N. Regulation of translation initiation by FRAP/mTOR. Genes Dev. 2001;15:807–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.887201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grandis J R, Drenning S D, Zeng Q, Watkins S C, Melhem M F, Endo S, Johnson D E, Huang L, He Y, Kim J D. Constitutive activation of Stat3 signaling abrogates apoptosis in squamous cell carcinogenesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4227–4232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gu H, Maeda H, Moon J J, Lord J D, Yoakim M, Nelson B H, Neel B G. New role for Shc in activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7109–7120. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.19.7109-7120.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guasch G, Mack G J, Popovici C, Dastugue N, Birnbaum D, Rattner J B, Pébusque M-J. FGFR1 is fused to the centrosome-associated protein CEP110 in the 8p12 stem cell myeloproliferative disorder with t(8;9)(p12;q33) Blood. 2000;95:1788–1796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamilton E, Miller K M, Helm K M, Langdon W Y, Anderson S M. Suppression of apoptosis induced by growth factor-withdrawal by an oncogenic form of c-CBL. J Biol Chem. 2001;275:9028–9037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hara K, Yonezawa K, Sakaue H, Ando A, Kotani K, Kitamura T, Kitamura Y, Ueda H, Stephens L, Jackson T R, et al. 1-Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity is required for insulin-stimulated glucose transport but not for RAS activation in CHO cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7415–7419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hart K C, Robertson S C, Kanemitsu M Y, Meyer A N, Tynan J A, Donoghue D J. Transformation and Stat activation by derivatives of FGFR1, FGFR3, and FGFR4. Oncogene. 2000;19:3309–3320. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hattori Y, Odagiri H, Katoh O, Sakamoto H, Morita T, Shimotohno K, Tobinai K, Sugimura T, Terada M. K-sam-related gene, N-sam, encodes fibroblast growth factor receptor and is expressed in T-lymphocytic tumors. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3367–3371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hawkins P T, Welch H, McGregor A, Eguinoa A, Gobert S, Krugmann S, Anderson K, Stokoe D, Stephens L. Signalling via phosphoinositide 3OH kinases. Biochem Soc Trans. 1997;25:1147–1151. doi: 10.1042/bst0251147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hockenbery D, Nunez G, Milliman C, Schreiber R D, Korsmeyer S J. Bcl-2 is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein that blocks programmed cell death. Nature. 1990;348:334–336. doi: 10.1038/348334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jefferies H B, Fumagall S, Dennis P B, Reinhard C, Pearson R B, Thomas G. Rapamycin suppresses 5′TOP mRNA translation through inhibition of p70s6k. EMBO J. 1997;16:3693–3704. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klingmuller U. The role of tyrosine phosphorylation in proliferation and maturation of erythroid progenitor cells-signals emanating from the erythropoietin receptor. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:637–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klint P, Kanda S, Claesson-Welsh L. Shc and a novel 89-kDa component couple to the Grb2-Sos complex in fibroblast growth factor-2-stimulated cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23337–23344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klint P, Claesson-Welsh L. Signal transduction by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Front Biosci. 1999;4:D165–177. doi: 10.2741/klint. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kouhara H, Hadari Y R, Spivak-Kroizman T, Schilling J, Bar-Sagi D, Lax I, Schlessinger J. A lipid-anchored Grb2-binding protein that links FGF-receptor activation to the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway. Cell. 1997;89:693–702. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80252-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lacronique V, Boureux A, Valle V D, Poirel H, Quang C T, Mauchauffé M, Berthou C, Lessard M, Berger R, Ghysdael J, Bernard O A. A TEL-JAK2 fusion protein with constitutive kinase activity in human leukemia. Science. 1997;278:1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lacronique V, Boureux A, Monni R, Dumon S, Mauchauffe M, Mayeux P, Gouilleux F, Berger R, Gisselbrecht S, Ghysdael J, Bernard O A. Transforming properties of chimeric TEL-JAK proteins in Ba/F3 cells. Blood. 2000;95:2076–2083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lange-Carter C A, Johnson G L. Ras-dependent growth factor regulation of MEK kinase in PC12 cells. Science. 1994;265:1458–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.8073291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levy D E, Gilliland D G. Divergent roles of STAT1 and STAT5 in malignancy as revealed by gene disruptions in mice. Oncogene. 2000;19:2505–2510. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin J X, Leonard W J. The role of Stat5a and Stat5b in signaling by IL-2 family cytokines. Oncogene. 2000;19:2566–2576. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Q, Schwaller J, Kutok J, Cain D, Aster J C, Williams I R, Gilliland D G. Signal transduction and transforming properties of the TEL-TRKC fusions associated with t(12;15)(p13;q25) in congenital fibrosarcoma and acute myelogenous leukemia. EMBO J. 2000;19:1827–1838. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Look A T. Genes altered by chromosomal translocations in leukemias and lymphomas. In: Vogelstein B, Kinzler K W, editors. The genetic basis of human cancer. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill Health Professions Division; 1998. pp. 109–141. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mohammadi M, Honegger A M, Rotin D, Fischer R, Bellot F, Li W, Dionne C A, Jaye M, Rubinstein M, Schlessinger J. A tyrosine-phosphorylated carboxy-terminal peptide of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (Fig) is a binding site for the SH2 domain of phospholipase C-γ1. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5068–5078. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.5068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mohammadi M, Dikic I, Sorokin A, Burgess W H, Jaye M, Schlessinger J. Identification of six novel autophosphorylation sites on fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 and elucidation of their importance in receptor activation and signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:977–989. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moscatello D K, Holgado-Madruga M, Emlet D R, Montgomery R B, Wong A J. Constitutive activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase by a naturally occurring mutant epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:200–206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mugneret F, Chaffanet M, Maynadié M, Guasch G, Favre B, Casasnovas O, Birnbaum D, Pébusque M-J. The 8p12 myeloproliferative disorder. t(8;19)(p12;q13.3): a novel translocation involving the FGFR1 gene. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:647–649. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neshat M S, Raitano A B, Wang H G, Reed J C, Sawyers C L. The survival function of the Bcr-Abl oncogene is mediated by Bad-dependent and-independent pathways: roles for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Raf. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1179–1186. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1179-1186.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ollendorff V, Guasch G, Isnardon D, Galindo R, Birnbaum D, Pébusque M-J. Characterization of FIM-FGFR1, the fusion product of the myeloproliferative disorder-associated t(8;13) translocation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26922–26930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ong S H, Guy G R, Hadari Y R, Laks S, Gotoh N, Schlessinger J, Lax I. FRS2 proteins recruit intracellular signaling pathways by binding to diverse targets on fibroblast growth factor and nerve growth factor receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:979–989. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.979-989.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pang L, Sawada T, Decker S J, Saltiel A R. Inhibition of MAP kinase kinase blocks the differentiation of PC-12 cells induced by nerve growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13585–13588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.13585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pearson R B, Dennis P B, Han J W, Williamson N A, Kozma S C, Wettenhall R E, Thomas G. The principal target of rapamycin-induced p70s6k inactivation is a novel phosphorylation site within a conserved hydrophobic domain. EMBO J. 1995;14:5279–5287. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peruzzi F, Prisco M, Dews M, Salomoni P, Grassilli E, Romano G, Calabretta B, Baserga R. Multiple signaling pathways of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor in protection from apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7203–7215. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Plowright E E, Li Z, Bergsagel P L, Chesi M, Barber D L, Branch D R, Hawley R G, Stewart A K. Ectopic expression of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 promotes myeloma cell proliferation and prevents apoptosis. Blood. 2000;95:992–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Polakiewicz R D, Schieferl S M, Dorner L F, Kansra V, Comb M J. A mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is required for mu-opioid receptor desensitization. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12402–12406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Popovici C, Adélaïde J, Ollendorff V, Chaffanet M, Guasch G, Jacrot M, Leroux D, Birnbaum D, Pébusque M-J. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is fused to FIM in stem-cell myeloproliferative disorder with t(8;13)(p12q12) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5712–5717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Popovici C, Zhang B, Grégoire M-J, Jonveaux P, Lafage-Pochitaloff M, Birnbaum D, Pébusque M-J. The t(6;8)(q27;p11) translocation in a stem cell myeloproliferative disorder fuses a novel gene, FOP, to fibroblast growth factor 1. Blood. 1999;93:1381–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reif K, Nobes C D, Thomas G, Hall A, Cantrell C A. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signals activate a selective subset of Rac/Rho-dependent effector pathways. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1445–1455. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(96)00749-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reiter A, Sohal J, Kulkarni S, Chase A, Macdonald D H, Aguiar R C, Goncalves C, Hernandez J M, Jennings B A, Goldman J M, Cross N C. Consistent fusion of ZNF198 to the fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 in thet(8;13)(p11;q12) myeloproliferative syndrome. Blood. 1998;92:1735–1742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Richelda R, Ronchetti D, Baldini L, Cro L, Viggiano L, Marzella R, Rocchi M, Otsuki T, Lombardi L, Maiolo A T, Neri A. A novel chromosomal translocation t(4;14)(p16.3;q32) in multiple myeloma involves the fibroblast growth-factor receptor 3 gene. Blood. 1997;90:4062–4070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schlessinger J. How receptor tyrosine kinases activate Ras. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:273–275. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90031-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schlessinger J, Ullrich A. Growth factor signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Neuron. 1992;9:383–391. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90177-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmelzle T, Hall M N. TOR, a central controller of cell growth. Cell. 2000;103:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smedley D, Hamoudi R, Clark J, Warren W, Abdul-Rauf M, Somers G, Venter D, Fagan K, Cooper C, Shipley J. The t(8;13)(p11;q11–12) rearrangement associated with an atypical myeloproliferative disorder fuses the fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 gene to a novel gene RAMP. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:637–642. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sohal J, Chase A, Iqbal S, Parker S, Goldman J M, Cross N C P. Two color FISH to detect FGFR1 rearrangements in myeloproliferative disorders: identification of the t(8;17)(p11;q25) as a new cytogenetic variant. Blood. 1999;94:180b. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Srinivasula S M, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Zangrilli J, Robertson N, Armstrong R C, Wang L, Trapani J A, Tomaselli K J, Litwack G, Alnemri E S. The Ced-3/interleukin 1 beta converting enzyme-like homolog Mch6 and the lamin-cleaving enzyme Mch2alpha are substrates for the apoptotic mediator CPP32. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27099–27106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.27099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stefan M, Koch A, Mancini A, Mohr A, Weidner K M, Niemann H, Tamura T. Src homology 2-containing inositol 5-phosphatase 1 binds to the multifunctional docking site of c-Met and potentiates hepatocyte growth factor-induced branching tubulogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3017–3023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009333200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thomas G, Hall M N. TOR signalling and control of cell growth. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:782–787. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ugolini F, Adélaïde J, Charafe-Jauffret E, Nguyen C, Jacquemier J, Jordan B, Birnbaum D, Pébusque M-J. Differential expression assay of chromosome arm 8p genes identifies Frizzied-related (FRP1/FRZB) and fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) as candidate breast cancer genes. Oncogene. 1999;18:1903–1910. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Walker E H, Pacold M E, Perisic O, Stephens L, Hawkins P T, Wymann M P, Williams R L. Structural determinants of phosphoinisitide 3-kinase by wortmannin, LY294002, quercetin, myricetin, and staurosporine. Mol Cell. 2000;6:909–919. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang J K, Gao G, Goldfarb M. Fibroblast growth factor receptors have different signaling and mitogenic potentials. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:181–188. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang J K, Xu H, Li L C, Goldfarb M. Broadly expressed SNT-like proteins link FGF receptor stimulation to activators of Ras. Oncogene. 1996;13:721–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weber-Nordt R M, Egen C, Wehinger J, Ludwig W, Gouilleux-Gruart V, Mertelsmann R, Finke J. Constitutive activation of STAT proteins in primary lymphoid and myeloid leukemia cells and in Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-related lymphoma cell lines. Blood. 1996;88:809–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Webster M K, Donoghue D J. FGFR activation in skeletal disorders: too much of a good thing. Trends Genet. 1997;13:178–182. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wymann M P, Pirola L. Structure and function of phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1436:127–150. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xiao S, Nalabolu S R, Aster J C, Ma J, Abruzzo L, Jaffe E S, Stone R, Weissman S M, Hudson T J, Fletcher J A. FGFR1 is fused with a novel zinc-finger gene, ZNF198, in the t(8;13) leukaemia/lymphoma syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;18:84–87. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xiao S, McCarthy J G, Aster J C, Fletcher J A. ZNF198-FGFR1 transforming activity depends on a novel proline-rich ZNF198 oligomerization domain. Blood. 2000;96:699–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu H, Lee K W, Goldfarb M. Novel recognition motif on fibroblast growth factor receptor mediates direct association and activation of SNT adapter proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17987–17990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.17987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yokogami K, Wakisaka S, Avruch J, Reeves S A. Serine phosphorylation and maximal activation of STAT3 during CNTF signaling is mediated by the rapamycin target mTOR. Curr Biol. 2000;10:47–50. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)00268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]