Abstract

Purpose:

To report our experience with two cases of Capnocytophaga keratitis.

Methods:

Retrospective case reports. We present the clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment strategies of two patients who presented with Capnocytophaga keratitis.

Results:

Both patients had risk factors including systemic immune compromise and ocular trauma. Both patients had robust inflammatory keratitis with necrosis. Case 1 demonstrates identification of Capnocytophaga with traditional microbiologic techniques. Case 2 demonstrates the use of unbiased metagenomic deep sequencing (MDS) for the identification of this unusual corneal pathogen.

Conclusions:

Capnocytophaga is a rare and aggressive infection. Even when traditional culture identifies the pathogen rapidly, the keratitis can progress to perforation. In cases of severe keratitis where traditional culture methods are unrevealing, MDS has potential to provide actionable diagnoses.

Keywords: Capnocytophaga keratitis, infectious keratitis, metagenomic deep sequencing

Capnocytophaga keratitis is a rare and aggressive ocular infection1–4. The largest case series, including ten cases, was reported in 20001. Five of these cases resulted in enucleation. We report our recent experience with two cases of Capnocytophaga keratitis to remind clinicians of this unusual and destructive infection and to highlight how both diagnosis and management of this infrequent bacterial infection is often challenging.

CASE REPORTS

CASE 1:

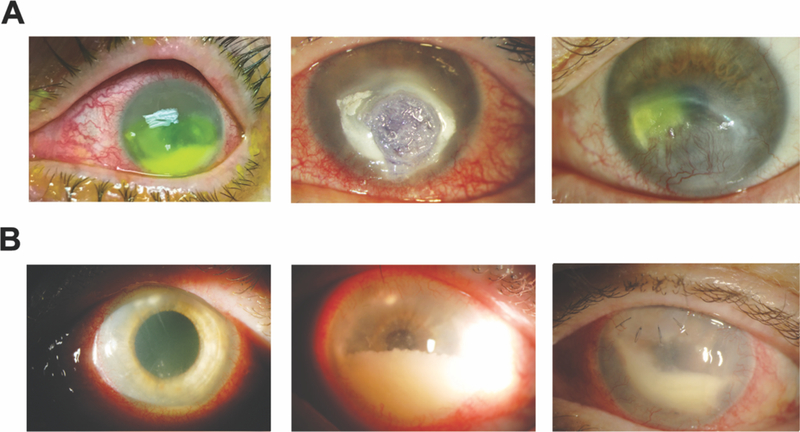

58 year-old man presents with a medical history significant for chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) status post-allogenic bone marrow transplant (BMT). Ocular history was significant for severe ocular graft versus host disease (GVHD), keratoconjunctivitis sicca, and bilateral neurotrophic keratopathy. His left eye was recently treated for a culture positive Streptococcus viridans corneal ulcer with hypopyon, and he recovered 20/60 acuity. The patient re-presented (Figure 1A, left) with a new, left large central corneal epithelial ulceration, 2 paracentral areas of corneal infiltration and a 3.5 mm hypopyon. Hourly fortified cefazolin (50 mg/ml) and topical moxifloxicin were initiated. Three days after culture, microbiology identified the growth of numerous Capnoctyophaga cynodegmi species. The patient reported, whilst celebrating his recovery from the S. viridans keratitis, he let his dog lick him all over his face, including his neurotrophic corneas. Four days after presentation, the patient developed a Seidel positive inferior paracentral perforation requiring an emergency glue procedure (Figure 1A, middle). As sensitivities for this rare pathogen require send-out evaluation, a review of prior Capnocytophaga case reports1–3 suggested treatment with topical clindamycin. Compounded clindamycin 5% was initiated hourly. The glue remained in place for 2 months and subsequently fell off. Visual acuity improved to 20/200. The globe remained intact and the area of prior perforation had vascularized (Figure 1A, right).

Figure 1: Slit lamp photographs of both cases.

(A) Case 1; left panel: presentation photo with infiltrates and hypopyon; middle panel: 4 days after presentation with perforation requiring glue; right panel: 2 months after glue. (B) Case 2; left panel: presentation photo with superior mid-stromal peripheral and paracentral subepithelial infiltrates with hypopyon; middle panel: progressive inflammation; right panel: small superonasal patch graft was performed after a diagnostic deep corneal biopsy. Robust anterior chamber inflammation remains. Fluid from an anterior chamber tap at this point was sent for metagenomic deep sequencing.

CASE 2:

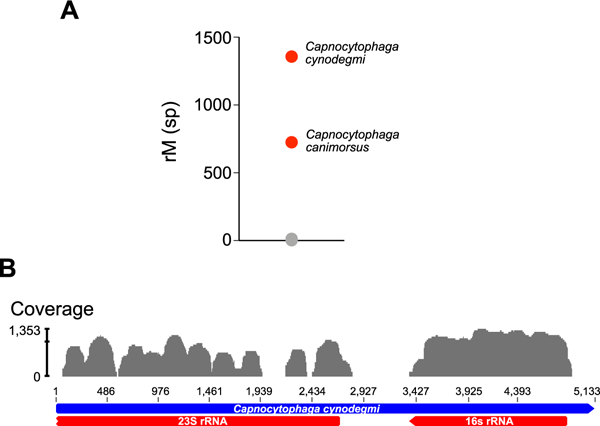

64 year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis being treated with rituximab infusions, sustained an outdoor foreign body injury after using motorized landscaping equipment. She developed ocular irritation and decreased vision and was treated at an outside facility. She presented one month into treatment for consultation after having failed therapy with topical prednisolone acetate 1% and topical ciprofloxacin. Her left cornea disclosed several superior mid stromal peripheral and tiny paracentral subepithelial infiltrates (Figure 1B, left). A 1mm hypopyon was present. Multiple gram stains, KOH stains, and cultures obtained from epithelial scrapings over the areas of subepithelial infiltrates were unrevealing. Confocal examination demonstrated non-specific inflammatory changes. The stromal lesions progressed deeper. Because the scattered superficial infiltrates were clinically concerning for satellite lesions, the patient was treated aggressively with topical, intra-stromal, and oral antifungal therapy (including amphotericin B, voriconazole and natamycin). Over the next 2 months, the patient developed progressive worsening of anterior chamber (AC) inflammation associated with deep endothelial plaques (Figure 1B, middle). Aqueous fluid from two AC washout procedures, as well as a cornea punch biopsy and patch-graft of the necrotic superior mid-stromal infiltrates (Figure IB, right) did not identify any organisms utilizing aerobic and anaerobic media. A robust inflammatory reaction persisted post patch-graft. Aqueous fluid from a third washout procedure was sent to a CLIA-certified lab for universal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for fungal genomes, and tested negative. Residual aqueous fluid was sent to the Proctor Foundation for metagenomic deep sequencing (MDS). MDS is an unbiased high-throughput sequencing approach that interrogates all potential genomes in a clinical sample. MDS was performed as previously described5. This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of the University of California, San Francisco approved the study (16–19151), and informed consent was obtained from the patient. Two species of Capnocytophaga, C. canimorsus and C. cynodegmi were identified (Figure 2A.) Orthogonal validation with partial 16S rRNA gene reverse transcription PCR and Sanger sequencing of the remaining RNA from the patient’s aqueous specimen confirmed the presence of Capnocytophaga genome (Figure 2B.) The patient was placed on topical clindamycin 5% with subsequent complete resolution of inflammation and infiltration in six weeks. After the MDS results, the patient reported she lives with numerous cats and dogs. Her acuity post resolution is hand motions from the irregular astigmatism from the patch graft as well as a dense cataract that progressed during the severe inflammatory episode. A penetrating keratoplasty with cataract surgery is planned.

Figure 2: Identification of C. canimorsus and C. cynodegmi by metagenomic deep sequencing.

(A) Organisms identified in the patient’s aqueous sample are plotted as a function of matched read pairs per million read pairs (rM) at the species level based on nucleotide alignment. Sequencing reads aligned to C. canimorsus and C. cynodegmi (red circles) predominated the sample. Grey circles indicate background sequencing reads. (B) C. cynodegmi sequences from Case 2 assembled against the reference C. cynodegmi genome (GenBank NZ_CP022378).

DISCUSSION:

Capnocytophaga is a gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium that is part of the normal oral flora of humans, dogs, and cats2,6. Human infection from Captocytophaga is rare. Ocular infection is similarly uncommon and though endophthalmitis7 and blepharoconjunctivitis8 are reported, keratitis is the most common clinical presentation. Upon review of available case reports1–4,7, the vast majority of all Capnocytophaga ocular infections occur in hosts with secondary risk factors such as immune compromise or trauma. In addition, Capnocytophaga keratitis often presents with a fairly rapid course to fulminant inflammation. Deep stromal infiltration with progression to necrosis is common and infections associated with Capnocytophaga are associated with a poor visual outcome1–4,7. Although several species of Capnocytophaga are part of the normal human oral flora, C. canimorsus and C. cynodegmi are found only in feline and canine oral flora. A recent report of seven cases of Capnocytophaga keratitis in dogs similarly demonstrates an aggressive course with keratomalacia and poor prognosis6.

Herein, we present two recent cases of Capnocytophaga keratitis, each illustrating some important aspects of this disease. Both cases demonstrated Capnocytophaga occurring in the setting of a compromised host. Both cases demonstrated robust ocular inflammation with hypopyon and stromal necrosis. Both cases gave a history of frequent contact with pet dogs and cats. Both cases improved with administration of topical clindamycin.

With Case 1, despite prompt identification of capnocytophaga, perforation still occurred within four days of presentation. Sensitivity information on unusual pathogens often takes significant time. In vitro Capnocytophaga susceptibility testing is further complicated by the relatively slow, fastidious, growth of the organism, and lack of laboratory standard guidelines for antimicrobial susceptibilities. Review of prior case reports describing the efficacy of topical clindamycin in similar cases was helpful in the management of this case.

Case 2 demonstrated the downfall of a ~60% sensitivity for the current gold standard cornea culture to identify pathogens responsible for infectious keratitis10. Cornea cultures are particularly challenging for deeper infections and infections with an intact epithelium. Additionally, with some strains of Capnocytophaga being fastidious in culture and difficult to isolate, standard culture techniques may be underestimating its occurrence. In cases where the suspicion for infection is high but conventional diagnostics are unrevealing, MDS has the potential to provide an actionable diagnosis, as shown with this case. The unbiased nature of MDS, where it can detect any viable pathogen in a clinical specimen, is particularly useful when the causative infection is rare and hence might not be on the differential diagnosis. While more validation studies are required before MDS can be routinely offered to practicing ophthalmologists, this approach holds promise as a complementary approach to conventional diagnostics for ocular surface or corneal infections.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award (T.D.); the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K08EY026986 (T.D.); Building Interdisciplinary Careers in Women’s Health of the National Institutes of Health K12HD085850 (J.S.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.Alexandrakis G, Palma LA, Miller D, et al. Capnocytophaga keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(8):1503–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chodosh J Cat’s tooth keratitis: human corneal infection with Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Cornea. 2001;20(6):661–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oshida T, Kamura Y, Sawa M. Demographic study of expulsive hemorrhages in 3 patients with infectious keratitis. Cornea. 2011;30(7):784–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghosheh FR, Ehlers JP, Ayres BD, et al. Corneal ulcers associated with aerosolized crack cocaine use. Cornea. 2007;26(8):966–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doan T, Wilson MR, Crawford ED, et al. Illuminating uveitis: metagenomic deep sequencing identifies common and rare pathogens. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ledbetter EC, Franklin-Guild RJ, Edelmann ML. Capnocytophaga keratitis in dogs: clinical, histopathologic, and microbiologic features of seven cases. Vet Ophthal 2018. doi: 10.1111/vop.12549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubsamen PE, McLeish WM, Pflugfelder S, et al. Capnocytophaga endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1993;100(4):456–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wasserman D, Asbell PA, Friedman AJ, et al. Capnocytophaga ochracea chronic blepharoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 1995;14(5):533–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Font RL, Jay V, Misra RP, et al. Capnocytophaga keratitis. A clinicopathologic study of three patients, including electron microscopic observations. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(12):1929–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLeod SD, Kolahdouz-Isfahani A, Rostamian K, et al. The role of smears, cultures, and antibiotic sensitivity testing in the management of suspected infectious keratitis. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(1):23–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]