Abstract

Objective

To determine whether the LINC strengths-based case management intervention was more effective than usual care for linking people who inject drugs (PWID) to HIV care and improving HIV outcomes.

Design

Two-armed randomized controlled trial.

Setting

Participants recruited from a narcology hospital in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Participants

349 HIV-positive PWID not on antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Intervention

Strengths-based case management over 6 months.

Main outcome measures

Primary outcomes were linkage to HIV care and improved CD4 count. We performed adjusted logistic and linear regression analyses controlling for past HIV care using the intention-to-treat approach.

Results

Participants (N=349) had the following baseline characteristics: 73% male, 12% any past ART use, and median values of 34.0 years of age and CD4 count 311. Within 6 months of enrollment 51% of the intervention group and 31% of controls linked to HIV care (AOR 2.34; 95% CI: 1.49–3.67; p< 0.001). Mean CD4 count at 12 months was 343 and 354 in the intervention and control groups, respectively (adjusted ratio of means 1.14; 95% CI: 0.91, 1.42, p=0.25).

Conclusion

The LINC strengths-based case management intervention was more effective than usual care in linking Russian PWID to HIV care, but did not improve CD4 count, likely due to low overall ART initiation. While case management can improve linkage to HIV care, specific approaches to initiate and adhere to ART are needed to improve clinical outcomes (e.g., increased CD4 cell count) in this population.

Keywords: HIV treatment, substance use, Russia, HIV, peer case managers, linkage to care

Introduction

Russia and Eastern Europe have rapidly expanding HIV epidemics, where transmission risk has been dominated by injection drug use [1–4]. Estimates of the total number of people living with HIV in Russia are between 900,000 and 2,000,000 [5, 6], with 47% of new HIV cases with a known mode of transmission registered among people who inject drugs (PWID) [5]. Yet, PWID do not comprise a majority of those receiving HIV care [7, 8], with one study from 2017 reporting that only 10% of HIV-positive PWID in St. Petersburg were receiving ART [9]. In 2013 it was estimated that viral load suppression was achieved only among 19% of all HIV-positive individuals in Russia [10].

A strategy to seek, test, treat and retain (STTR) HIV-positive individuals in care can advance progress along the HIV care continuum [11, 12]. Russia and other countries in the region have struggled to effectively link HIV-positive patients to HIV care [2, 13, 14].

Case management is one strategy used to improve access and care delivery as it focuses on removing systemic and individual barriers to care [15]. One model of this kind of strategy used to affect treatment and engagement of marginalized individuals is strengths-based case management. Brief strengths-based case management was effectively adapted for the Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study (ARTAS) intervention [16], designed to support linkage to care among persons with HIV in the United States. The ARTAS intervention, focusing on linkage of recently diagnosed HIV-positive patients to HIV care, demonstrated increased linkage (78% vs. 60% with at least one visit within 6 months and 64% vs. 48% with at least two visits within 12 months) compared to usual care [16]. This model has been operationalized across diverse settings in the USA as part of a CDC demonstration project, facilitating its adaptation for use in other national contexts [17]. Notably, ARTAS in its original demonstration of efficacy did not address PWID’s needs specifically, and in fact, found less effectiveness for those injecting drugs, suggesting the need for modifications to give support to PWID.

PWID’s poor linkage to HIV care in Russia [9, 18] may in part be attributable both to the individual’s addiction struggles and a fear of stigmatization [19, 20]. Russia also has the barrier of siloed addiction and infectious disease care settings [14, 21, 22], despite evidence of benefit from coordinated care for HIV-positive PWID [23, 24]. The Russian AIDS treatment system includes case managers (CMs) for patient care, but their efforts focus on retention in HIV care [25] and not linkage. CMs also work in narcology treatment, which interfaces with PWID, but these CMs do not focus on HIV care or the unique challenges faced by Russian PWID (e.g., stigma, limited medications for opioid use disorder [OUD]) [26–30]. The unavailability of opioid agonist therapy for treatment of OUD in Russia limits options for effective medical care of this problem. One observational study in St. Petersburg, Russia found that not only was intensive case management feasible, but it improved the retention and adherence of PWID to antiretroviral treatment [31].

Hence, in this randomized controlled trial (RCT), Linking Infectious and Narcology Care (LINC), we adapted the ARTAS intervention for the Russian setting by implementing peer-led strengths-based case management to support and motivate HIV-positive PWID in a narcology hospital in St. Petersburg, Russia to link with HIV medical care.

Methods

Objective and Study Design

The LINC study was an RCT designed to assess the effectiveness of a strengths-based case management intervention among HIV-positive Russian PWID compared to standard of care treatment in Russia on the following outcomes: 1) linkage to HIV care (i.e., 1 or more visits to HIV medical care) within 6 months of enrollment; 2) retention in HIV care (i.e., 1 or more visits to HIV medical care in 2 consecutive 6 month periods) within 12 months of enrollment; 3) appropriate HIV care in Russia at the time of the study (i.e., prescribed ART or having a second CD4 count if CD4 >350) within 12 months of enrollment; and 4) improved HIV health outcomes (i.e., CD4 count) and self-reported hospitalizations 12 months after enrollment. The following two outcomes were designated as the overall primary outcomes of the trial: linkage to HIV care and CD4 count at 12 months.

Participants

A total of 349 participants were recruited from inpatient wards at the City Addiction Hospital in St. Petersburg, Russia from July 2012 through May 2014. The St. Petersburg City Addiction Hospital is a government-funded 500-bed hospital, providing free addiction care to residents of St. Petersburg, who are registered as having a substance use disorder (drug or alcohol). One to five days after admission to the narcology hospital and treatment of withdrawal symptoms, patients were screened for study eligibility. Research Assessors (RAs), who were City Addiction Hospital physicians with narcology subspecialty training (i.e., narcologists), but who were not part of the patient’s medical care, conducted the screening. The RA offered eligible patients enrollment into the study and administered and documented the informed consent.

Eligibility criteria included the following: 1) age 18–70 years; 2) HIV-positive; 3) hospitalized at the narcology hospital; 4) history of injection drug use; 5) agree to CD4 count testing; 6) have 2 contacts to assist with follow-up; 7) live within 100 km of St. Petersburg; 8) have a telephone; 9) willing to receive HIV care at Botkin Infectious Disease Hospital. The following served as exclusion criteria for study enrollment: 1) currently on ART; 2) not fluent in Russian; 3) cognitive impairment precluding informed consent. Although original eligibility criteria stipulated that participants should be willing to receive care from Botkin Infectious Disease Hospital, given the evolving process of local HIV care delivery, this original eligibility criterion was abandoned upon actual enrollment.

The LINC study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Boston University Medical Campus and First St. Petersburg Pavlov State Medical University. A more extensive study protocol [32] has been published and the study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00483483.)

Participant Assessment

Baseline study interviews were conducted at the narcology hospital by trained research staff and at 6 and 12 months post-enrollment at First St. Petersburg Pavlov State Medical University. At baseline and 12-month assessments, blood was collected for CD4 count testing. At 6- and 12-month time points, medical chart reviews were conducted to obtain data on clinic visit dates, CD4 testing dates, and ART information [32]. Chart review was conducted of records at both Botkin Infectious Disease Hospital and the St Petersburg City AIDS Center, which together comprise the venues providing HIV care for St. Petersburg residents.

Assessment data collected at baseline included participant demographics [33]; HIV testing and HCV diagnosis [34]; previous HIV care, depressive symptoms [35, 36]; and drug use [37–40]. At follow-up, additional sections included ART use and adherence [41–43] and case manager-related questions.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were linkage to HIV care and CD4 count at 12 months. Secondary outcomes were retention in HIV care within 12 months of enrollment, appropriate HIV care in Russia at the time of the study, and self-reported hospitalizations at 12 months. Given that information obtained from chart review determined linkage, retention, and appropriate HIV care (i.e., ART receipt or CD4 testing), minimal loss to follow-up occurred for these primary and secondary outcomes (i.e., absence of chart information was defined as no linkage, retention, or appropriate care). Loss to follow up only occurred in the event of participant death or incarceration.

LINC Intervention

A collaborative cross-cultural team of investigators in Russia and the United States developed the LINC intervention based on an adaptation of the ARTAS intervention for use in the Russian setting and specifically with PWID [16]. The LINC intervention used a strengths-based case management approach to help motivate participants to engage in HIV medical care. Peer case managers (CMs) met with participants individually to facilitate recognition of participants’ own strengths to reduce barriers to HIV care and ultimately improve HIV outcomes. Peer CMs were HIV-positive PWID in stable remission receiving HIV care. The LINC approach was based on the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) and Psychological Empowerment Theory (PET) frameworks [44, 45].

CMs delivered the intervention via five one-on-one sessions over a 6-month period. The first session took place at the City Addiction Hospital and sessions 2 – 5 were held anywhere in the community, or via phone if necessary (less than 2% of all sessions were conducted by phone). The first session also included CM sharing CD4 results with the participant. The intervention is described in detail in our published protocol paper [32]. CM activities are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

LINC Intervention Session Components

| Session 1 | Brainstorm client strengths Develop goals related to obtaining HIV and addiction care Show informational video about HIV and ART Provide a map of location of HIV clinics and clinic phone numbers Discuss barriers to receiving HIV care and how to overcome them Discuss the concept of case management Discuss options for addiction care Discuss the client’s most recent CD4 count |

| Sessions 2–5 | Focus on meeting previously identified goals and creating goals Reinforce previously identified strengths |

Control Group

Participants in the control arm received the narcology hospital’s standard of care. All participants received a resource card containing harm reduction information and contact information for HIV care.

Process Evaluation

To ensure high quality implementation of the intervention and control conditions, we provided structured trainings and regular supervision and monitoring of the case management sessions [46]. We also obtained survey feedback from both CMs and participants to assess their satisfaction with the LINC intervention. Of the intervention group participants who completed the Participant Satisfaction Survey (n=84), 91% reported being very much or somewhat satisfied with the LINC intervention. In regards to linkage to care, 60% of participants surveyed agreed that CMs helped them link to HIV care, while 82% of participants surveyed thought the CMs would help others link to HIV care. Case managers (n=4) were interviewed quarterly and 75% of those interviewed thought the program was helping participants “very much”.

Randomization & Blinding

Randomization was stratified on two self-reported factors: 1) whether an outpatient appointment with an infectious disease physician occurred in the 12 months prior to enrollment; and 2) whether the participant had ever been hospitalized for his or her HIV infection. Stratified randomization was used to ensure balance with respect to these potential confounding factors. Blocked randomization using random block sizes was used within each stratum. Randomization occurred via a custom web-application utilizing a computer-generated randomization table.

Participants and case managers could not be blinded to group assignment due to the nature of the intervention. However, to minimize measurement bias, the baseline assessment was administered prior to randomization and follow up assessors were not alerted of randomization assignment.

Statistical Analysis

The primary analyses were conducted according to the intention-to-treat principle where all randomized participants were analyzed according to their randomized group. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study sample and to assess potential differences in baseline characteristics by intervention arm. The primary outcome, linkage to HIV care, and other binary outcomes were analyzed using logistic regression models adjusting for the randomization stratification variables. The primary outcome CD4 count at 12 months was natural log transformed due to a skewed distribution and then analyzed using multiple linear regression. Results were back transformed for ease of interpretation, the measure of effect reported is a ratio of means for the LINC intervention relative to the control group. We used multiple imputation (using 20 generated complete datasets) to account for missing data in the following outcomes: linkage to HIV care (n=20), CD4 count at 12 months (n=116), retention in HIV care (n=43), appropriate HIV care (n=18) and self-reported hospitalizations at 12 months (n=81). Variables used for imputation were gender, age, marital status, education, ART use, outpatient HIV visit, ever hospitalized for HIV, CD4 count, years since HIV diagnosis, CES-D score, randomization group, and baseline value of the outcome. Secondary per protocol analyses were conducted by first limiting the intervention group to participants who completed two or more case management sessions and then additionally limiting to those who completed all five sessions. Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted removing the stratification factor of past year outpatient HIV visit from primary intention-to-treat analyses given the concern that this variable was compromised by one assessor at baseline. We calculated that a sample size of 350 participants would provide 80% power to detect an absolute difference of 15% in the proportions linking to HIV care based on a chi-square test with continuity correction. This assumed a 2-sided test, a significance level of 0.05, 20% linking to HIV care in the control group, and 10% loss to follow-up. We determined the study would also have 80% power to detect a difference as small as 90 cells/μL in CD4 count at 12 months between the two study groups, assuming a standard deviation of 269 cells/μL, and 20% loss to follow-up. Assumptions of loss to follow-up differ between the two primary outcomes due to utilization of chart review to assess linkage to HIV care versus relying on participants attending their final study visit to receive a test for CD4 count. We performed all analyses using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

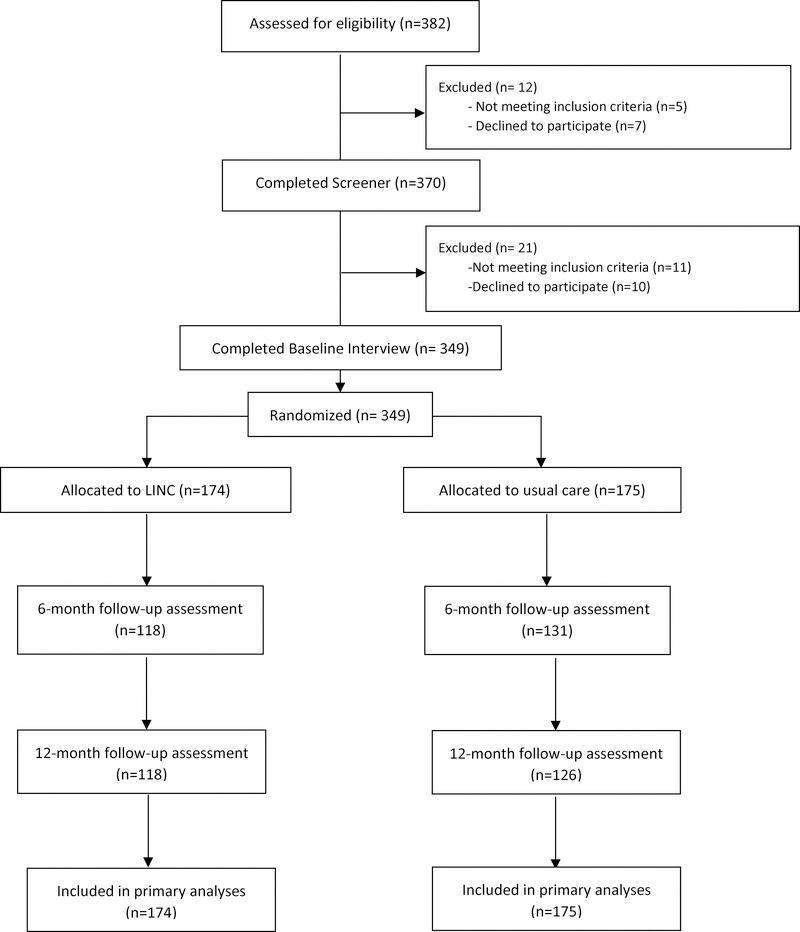

Of 382 narcology hospital patients whose charts were reviewed as part of the pre-screening process, 370 (97%) were eligible and agreed to be screened. Of those, 359/370 (97%) met eligibility criteria to participate in the study. The main reason for ineligibility was having taken ART in the past 30 days (4/11). Of those who were eligible, 349/359 (97%) were enrolled and randomized (Fig. 1). The participants’ baseline characteristics are in Table 2. The usual care (control) and LINC intervention groups appeared balanced on demographic and clinical variables. Follow-up interview rates for the intervention and control groups were 118/174 (68%) and 131/175 (75%) at 6 months, and 118/174 (68%) and 126/175 (72%) at 12 months, respectively. Deaths occurred in 10% of the participants over the course of this 12-month study, 21/174 (12%) intervention and 12/175 (7%) control group. A total of 25 participants were incarcerated over the course of the study, 12/174 (7%) intervention and 13/175 (7%) control group.

Figure 1.

LINC CONSORT Diagram

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of LINC study Participants – HIV-positive PWID not in HIV Care (n=349)

| Overall | Usual Care (n=175) | LINC Intervention (n=174) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 34.0 (4.8) | 33.9 (4.6) | 34.1 (5.0) |

| Male | 256 (73.4%) | 125 (71.4%) | 131 (75.3%) |

| Education 11 grades or higher | 243 (69.6%) | 123 (70.3%) | 120 (69.0%) |

| Married or with long-term partner | 113 (32.4%) | 52 (29.7%) | 61 (35.1%) |

| Unemployed | 190 (54.4%) | 93 (53.1%) | 97 (55.7%) |

| Mean years since HIV diagnosisa (SD) | 7.3 (4.3) | 7.5 (4.1) | 7.0 (4.5) |

| Mean CD4 count b (SD) Median CD4 count b (IQR) |

365 (270) 311 (163–492) |

375 (267) 329 (155–522) |

354 (275) 297 (177–458) |

| CD4 count < 350b | 187 (56.8%) | 85 (51.5%) | 102 (62.2%) |

| Depressive symptoms c (CES-D >= 16) | 292 (89.3%) | 150 (89.8%) | 142 (88.8%) |

| Ever ART use | 43 (12.3%) | 20 (11.4%) | 23 (13.2%) |

| Hospitalized for HIV in past year | 20 (5.7%) | 8 (4.6%) | 12 (6.9%) |

control n=163; intervention n=160

control n= 165; intervention n=164

control n= 167; intervention n=160

Primary Outcomes

At 6 months post-enrollment, 51% of the LINC intervention group and 31% of controls linked to HIV care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.34; 95% CI: 1.49, 3.67; p = <0.001). No significant differences were observed between groups in CD4 count at 12 months (343 vs. 354 for intervention and control groups, respectively; adjusted ratio of means 1.14; 95% CI: 0.91, 1.42, p = 0.25). (Table 3)

Table 3.

Intention-to-treat Analyses: Effect of LINC intervention compared to usual care on HIV outcomes

| Usual Care (n=175) | LINC Intervention (n=174) | AORa (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | ||||

| Linkage to HIV care (%) | 31% | 51% | 2.34 (1.49, 3.67) | < 0.001 |

| CD4 count at 12 months, mean (SD) | 354 (341) | 343 (257) | 1.14b (0.91, 1.42) | 0.25 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Retention in HIV care (%) | 22% | 27% | 1.30 (0.78, 2.17) | 0.31 |

| Appropriate HIV care (%)c | 23% | 33% | 1.69 (1.02, 2.82) | 0.04 |

| Self-reported hospitalizations at 12 months (%) | 9% | 15% | 1.77 (0.84, 3.74) | 0.14 |

Comparing LINC intervention vs. Usual care, adjusting for randomization stratification factors, i.e. outpatient HIV visit past year and ever hospitalized for HIV

Represents ratio of means after back transformation from log scale

Composite of prescribed ART or having 2nd CD4 count if initial CD4 >350.

Usual care: 10% prescribed ART, 9% had 2nd CD4 count

LINC intervention: 17% prescribed ART, 12% had 2nd CD4 count

In both arms, 4% had no initial CD4 count but were imputed as appropriate care based on other participant characteristics.

Secondary Outcomes

Differences were not statistically significant between the LINC intervention and control groups with respect to retention in HIV care as determined by medical record review (AOR 1.30; 95% CI: 0.78, 2.17; p = 0.31); or self-reported hospitalizations at 12 months (AOR 1.77; 95% CI: 0.84, 3.74; p= 0.14). (Table 3) Those assigned to the LINC intervention had higher odds of receiving appropriate HIV care within 12 months of enrollment compared to those receiving usual care (33% vs 23% for intervention and control groups, respectively; AOR 1.69; 95% CI: 1.02, 2.82; p=0.04). Of note, 17% of the intervention group and 10% of the control group participants received ART within 12 months of study enrollment; 12% of intervention participants and 9% of controls received a second CD4 count if the first was above 350. Post hoc sensitivity analyses that did not adjust for past year outpatient HIV visit suggested that this potentially compromised variable did not impact study results.

Secondary per protocol analyses were conducted on two subgroups of intervention participants, those completing two or more case management sessions (n=131) and those completing all five sessions (n=85). (Table 4) The subgroups did not differ in their characteristics, with the exception of age, where participants who completed all five sessions tended to be older (mean age 35.4 vs 32.9 years, p=0.003). The conclusions were similar to the main study findings (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of LINC intervention on HIV outcomes among participants attending 2 or more (N=131) or all 5 case management sessions (N=85) vs. Usual care (N=175)

| 2 or more CM sessions vs. Usual Care | All 5 CM sessions vs. Usual Care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR a (95% CI) | p-value | AOR a (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Primary outcomes | ||||

| Linkage to HIV care | 2.57 (1.59, 4.16) | 0.0001 | 2.91 (1.68, 5.07) | 0.0002 |

| CD4 count at 12 months | 1.12 b (0.89, 1.43) | 0.33 | 1.09b (0.82, 1.44) | 0.55 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Retention in HIV care | 1.31 (0.76, 2.28) | 0.33 | 1.63 (0.89, 2.98) | 0.91 |

| Appropriate HIV care | 2.11 (1.10, 4.04) | 0.03 | 2.54 (1.25, 5.18) | 0.01 |

| Self-reported hospitalizations at 12 months | 1.52 (0.83, 4.28) | 0.13 | 1.85 (0.73, 4.72) | 0.28 |

Comparing LINC intervention vs. Usual care, adjusting for outpatient HIV visit past year and ever hospitalized for HIV

Adjusted ratio of means

Discussion

The LINC strengths-based peer-led case management intervention, comprised of five sessions delivered over a 6-month period, was more effective than usual care in linking Russian HIV-positive PWID to HIV care within 6 months of enrollment (51% vs. 31%), and helping participants receive appropriate HIV care (33% vs 23%) within 12 months of enrollment. Yet, differences between groups with respect to CD4 count and retention in care at 12 months were not statistically significant.

The attributes of the intervention included utilizing a strengths-based approach to motivate participants to engage in care, providing and explaining CD4 count results, and use of peers to serve as case managers (i.e., HIV-positive individuals in recovery from opioid use disorder). The novelty of the intervention was that these modalities were adapted for use with PWID. Peer support and peer-led interventions have been successful in improving risky sex behaviors [47, 48] adherence to ART [49], HIV knowledge [48], enrollment in HIV care [50] and initiation of ART [51]. Some interventions used point-of-care CD4 testing and strengths-based care facilitation, however these studies were not among PWID [51, 52]. Consistency of findings for intention-to-treat and per protocol analyses suggest that intensity of contacts may not be critical to achieve these outcomes; however, further research is needed to determine if intensity of contacts over an extended period may be helpful to achieve clinical outcomes not seen in this study’s findings.

Participants randomized to the intervention had higher odds of linking to HIV care and receiving appropriate HIV care, but they were not retained in care, nor were their CD4 counts significantly improved compared to controls. Despite progress addressing the Russian HIV care continuum, the overall engagement in HIV care and initiation of ART was low. Thus, broader dissemination of this intervention is not warranted in Russia until it is enhanced with features to further increase engagement in HIV care and ART uptake. These goals may not be amenable to a case management intervention alone. Nonetheless, importantly, the model did yield benefits and if enhanced over time, has potential for sustainability and scalability given the current employment of case managers in the Russian health system, albeit in a different capacity.

At 12 months, differences in CD4 count and retention in HIV care were not statistically significant. It is possible that the limited extent and duration (i.e., 6 months) of participants’ receiving support from the case managers impacted these long-term outcomes. This is consistent with results from the Project Hope study, which did not detect differences in 12-month HIV viral suppression following a 6-month patient navigation intervention with and without financial incentives vs usual care [53]. The LINC study findings indicate both, the need to improve overall linkage from addiction treatment to HIV care and to improve engagement with HIV services after initial linkage.

While the LINC intervention was designed to address participant barriers, it did not affect system changes, which may be needed to impact barriers. Such barriers include the requirement for multiple visits prior to initiating ART [20, 29], ongoing substance use [19], and stigma by HIV providers related to ongoing substance use [54, 55]. Organizing services so as to be able to initiate ART at first visit in the narcology hospital context or on first appointment to the HIV center might yield benefits for engagement as has been shown in other country settings [50, 56].

One obvious explanation for the inability to detect significant differences in improved CD4 counts is the very low overall uptake of ART (14%). With the current universal ART recommendations in Russia, new since the study’s implementation, the goal for the patient is more clear and straightforward - pursue effective ART regardless of CD4 count.

Active injection drug use is a documented barrier to achieving desired HIV care continuum outcomes [9]. In focus groups and interviews with PWID and providers in St. Petersburg, active injection drug use was found to exacerbate challenges faced by PWID in linking to HIV care [19]. These findings were confirmed in focus groups with LINC participants and interviews with LINC case managers [54]. Given that almost half of the study participants reported past 30-day injection drug use at their final study visit, consideration of early use of pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder is indicated and of great importance both for linkage to HIV care and avoidance of opioid overdose injury and death [57].

The limitations of this study include potential modest generalizability. This intervention will not reach people who do not receive treatment within the narcology hospital. However, narcology hospitals are a common mode of addiction treatment in Russia and Eastern Europe [58]. In Russia, engaging both HIV-positive PWID within narcology treatment and those not engaged in such care is needed. The study’s implications are uniquely applicable in Russia in that opioid agonist treatment is unavailable. Such pharmacotherapy, a standard clinical approach for this population outside of Russia, is not bundled with case management in the LINC intervention, and thus the impact of that strategy is unclear.

Conclusion

The LINC intervention, strengths-based peer-delivered case management embedded in narcology treatment, can support HIV-positive PWID to link to HIV care in Russia and receive more appropriate care. Importantly, however, the benefits of the LINC intervention need to be bolstered to substantially advance down the HIV care continuum. Use of a more extended period of LINC case management together with active pharmacological narcology treatment and ART at first encounter may serve to support HIV-positive PWID to improve the pursuit of the UNAIDS goal of 90–90-90. Such an approach may benefit both those living with HIV, as well as reduce HIV transmission by achievement of viral suppression with effective ART.

Acknowledgements

JHS designed the study and secured funding. JHS and NG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. DMC participated in study design and led statistical analyses. EQ carried out statistical analyses. AR led development and adaptation of the intervention. NG and CB participated in study design and study implementation. EB, EK, OT, and DL led study implementation in the field. AG led the formative evaluation to inform the development of the intervention. All authors participated in weekly study meetings and critically reviewed and provided feedback on the manuscript. The project described was supported by grant R01DA032082 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and by the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research (P30AI042853). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding: The project described was supported by grant R01DA032082 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and by the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research (P30AI042853). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Debbie Cheng serves on Data Safety and Monitoring Boards for Janssen. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Data sharing: Data collected for the study are available to interested investigators in the URBAN ARCH Repository: www.urbanarch.org. The data are also available through the data coordinating center for the STTR project (https://www.uwchscc.org/ and https://sttr-hiv.org/cms). All data requests must be approved by the STTR publications and presentations committee due to the sensitive nature of the project involving participants with substance use, HIV infection, and/or criminal justice involvement.

Clinical trial registration details: This study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov through the National Institutes of Health - Linking Infectious and Narcology Care in Russia (LINC), NCT00483483.

References

- [1].Federal AIDS Center. Recent epidemiological data on HIV infection in the Russian Federation (2016). http://www.positivenet.ru/uploads/2/4/2/9/24296840/hiv-2016.pdf. [Accessed 14 June 2018].

- [2].Cohen J Late for the epidemic: HIV/AIDS in Eastern Europe. Science 2010; 329:160,162–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].World Health Organization. Key facts on HIV epidemic in Russian Federation and progress in 2011. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/188761/Russian-Federation-HIVAIDS-Country-Profile-2011-revision-2012-final.pdf. [Accessed 14 June 2018].

- [4].Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Together we will end AIDS.Geneva: UNAIDS (2012). http://files.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/JC2296_UNAIDS_TogetherReport_2012_en.pdf. [Accessed 14 June 2018].

- [5].Federal Scientific Center for the Prevention and Combat of AIDS of the Public Office of the Central Scientific Research Institute Rospotrebnadzor. Reference on HIV infection in the Russian Federation as of June 30, 2017. http://www.webcitation.org/70AqWiRvy. [Accessed 14 June 2018].

- [6].Beyrer C, Wirtz AL, O’Hara G, Leon N, Kazatchkine M. The expanding epidemic of HIV-1 in the Russian Federation. PLoS Med 2017; 14:e1002462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/ WHO Regional Office for Europe. HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Europe (2015). http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/324370/HIV-AIDS-surveillance-Europe-2015.pdf. [Accessed 14 June 2018].

- [8].Sarang A, Rhodes T, Sheon N. Systemic barriers accessing HIV treatment among people who inject drugs in Russia: a qualitative study. Health Policy Plan 2012; 28:681–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Heimer R, Usacheva N, Barbour R, Niccolai LM, Uusküla A, Levina OS. Engagement in HIV care and its correlates among people who inject drugs in St Petersburg, Russian Federation and Kohtla-Järve, Estonia. Addiction 2017; 112:1421–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pokrovskaya A, Popova A, Ladnaya N, Yurin O. The cascade of HIV care in Russia, 2011–2013. J Int AIDS Soc 2014; 17:19506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Samet JH, Freedberg KA, Savetsky JB, Sullivan LM, Stein MD. Understanding delay to medical care for HIV infection: the long-term non-presenter. AIDS 2001; 15:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States: Stages of Care (2012). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/research_mmp_stagesofcare.pdf. [Accessed 14 June 2018]/

- [13].Rhodes T, Sarang A, Bobrik A, Bobkov E, Platt L. HIV transmission and HIV prevention associated with injecting drug use in the Russian Federation. Int J Drug Policy 2004; 15:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tkatchenko-Schmidt E, Atun R, Wall M, Tobi P, Schmidt J, Renton A. Why do health systems matter? Exploring links between health systems and HIV response: a case study from Russia. Health Policy Plan 2010; 25:283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brooks DM. HIV-Related Case Management In: Handbook of HIV and Social Work: Principles, Practice, and Populations. Poindexter CC, (editor). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 2010. pp.77–88. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, Loughlin AM, del Rio C, Strathdee S, et al. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS 2005; 19:423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Craw J, Gardner L, Rossman A, Gruber D, Noreen O, Jordan D, et al. Structural factors and best practices in implementing a linkage to HIV care program using the ARTAS model. BMC Health Serv Res 2010; 10:246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Belyakov N, Konovalova NV, Ogurtsova SV, Svetlichnaya YS, Bobreshova AS, Gezey MA, et al. Is a New Wave of HIV Spread in the Northwest of the Russian Federation a Threat or the Fact? HIV Infection and Immunosuppressive Disorders 2016; 8:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kiriazova T, Lunze K, Raj A, Bushara N, Blokhina E, Krupitsky E, et al. “It is easier for me to shoot up”: stigma, abandonment, and why HIV-positive drug users in Russia fail to link to HIV care. AIDS Care 2017; 29:559–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wolfe D, Carrieri MP, Shepard D. Treatment and care for injecting drug users with HIV infection: a review of barriers and ways forward. Lancet 2010; 376:355–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Elovich R, Drucker E. On drug treatment and social control: Russian narcology’s great leap backwards. Harm Reduct J 2008; 5:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Volik MV, Karmanova GA, Berezina EB, Kresina TF, Sadykova RG, Khalabuda LN, et al. Development of Combination HIV Prevention Programs for People Who Inject Drugs through Government and Civil Society Collaboration in the Russian Federation. Adv Prev Med 2012; 2012:874615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Haldane V, Cervero-Liceras F, Chuah FL, Ong SE, Murphy G, Sigfrid L, et al. Integrating HIV and substance use services: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2017; 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Simeone C, Shapiro B, Lum PJ. Integrated HIV care is associated with improved engagement in treatment in an urban methadone clinic. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2017; 12:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. FY2008 Country Profile: Russia: 2009;2–2. [Google Scholar]

- [26].World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, Management of Substance Abuse. Treatment of injecting drug users with HIV/AIDS: promoting access and optimizing service delivery (2006). http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/treatment_idus_hiv_aids.pdf. [Accessed 14 June 2018].

- [27].Jurgens R, Csete J, Amon JJ, Baral S, Beyrer C. People who use drugs, HIV, and human rights. Lancet 2010; 376:475–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Amirkhanian YA, Kelly JA, Kuznetsova AV, DiFranceisco WJ, Musatov VB, Pirogov DG. People with HIV in HAART-era Russia: transmission risk behavior prevalence, antiretroviral medication-taking, and psychosocial distress. AIDS Behav 2011; 15:767–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kelly J, Amirkhanian Y, Yakovlev A, Musatov V, Meylakhs A, Kuznetsova A, et al. Stigma reduces and social support increases engagement in medical care among persons with HIV infection in St. Petersburg, Russia. J Int AIDS Soc 2014; 17:19618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Pecoraro A, Mimiaga MJ, O’Cleirigh C, Safren SA, Blokhina E, Verbitskaya E, et al. Lost-to-care and engaged-in-care HIV patients in Leningrad Oblast, Russian Federation: barriers and facilitators to medical visit retention. AIDS Care 2014; 26:1249–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Shaboltas AV, Skochilov RV, Brown LB, Elharrar VN, Kozlov AP, Hoffman IF. The feasibility of an intensive case management program for injection drug users on antiretroviral therapy in St. Petersburg, Russia. Harm Reduct J 2013; 10:15–7517-10–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gnatienko N, Han SC, Krupitsky E, Blokhina E, Bridden C, Chaisson CE, et al. Linking Infectious and Narcology Care (LINC) in Russia: design, intervention and implementation protocol. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2016; 11:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr HL, et al. New data from the Addiction Severity Index. Reliability and validity in three centers. J Nerv Ment Dis 1985; 173:412–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].National Institute on Drug Abuse: Seek, Test, Treat and Retain Initiative. HIV/HCV/STI testing status and organizational testing practices questionnaire (2011). http://www.drugabuse.gov/researchers/research-resources/data-harmonization-projects/seek-test-treat-retain/addressing-hiv-among-vulnerable-populations. [Accessed 14 June 2018].

- [35].Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977; 1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Chishinga N, Kinyanda E, Weiss HA, Patel V, Ayles H, Seedat S. Validation of brief screening tools for depressive and alcohol use disorders among TB and HIV patients in primary care in Zambia. BMC Psychiatry 2011; 11:75–244X-11–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Broome K, Knight K, Joe G, Simpson D. Evaluating the drug-abusing probationer: Clinical interview versus self-administered assessment. Criminal Justice and Behavior 1996; 23:593–606. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Knight K, Simpson D, Morey J. An evaluation of the TCU drug screen. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, US Department of Justice; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Weatherby N, Needle R, Cesar H, Booth R, McCoy C, Watters J, et al. Validity of self-reported drug use among injection drug users and crack smokers recruited through street outreach. Eval Program Plann 1994; 17:347–347-355. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Needle R, Fisher DG, Weatherby N, Chitwood D, Brown B, Cesari H, et al. The reliability of self-reported HIV risk behaviors of drug users. Psychol Addict Behav 1995; 9:242–250. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Walsh JC, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Responses to a 1 month self-report on adherence to antiretroviral therapy are consistent with electronic data and virological treatment outcome. AIDS 2002; 16:269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Giordano TP, Guzman D, Clark R, Charlebois ED, Bangsberg DR. Measuring adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a diverse population using a visual analogue scale. HIV Clin Trials 2004; 5:74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG). AIDS Care 2000; 12:255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bandura A Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zimmerman MA. Psychological empowerment: issues and illustrations. Am J Community Psychol 1995; 23:581–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychol 2004; 23:443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Davey-Rothwell MA, Tobin K, Yang C, Sun CJ, Latkin CA. Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial of a Peer Mentor HIV/STI Prevention Intervention for Women Over an 18 Month Follow-Up. AIDS Behav 2011; 15:1654–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Simoni JM, Nelson KM, Franks JC, Yard SS, Lehavot K. Are peer interventions for HIV efficacious? A systematic review. AIDS Behav 2011; 15:1589–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Malta M, Carneiro-da-Cunha C, Kerrigan D, Strathdee SA, Monteiro M, Bastos FI. Case management of human immunodeficiency virus-infected injection drug users: a case study in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 37 (Suppl 5):S386–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Govindasamy D, Meghij J, Kebede Negussi E, Clare Baggaley R, Ford N, Kranzer K. Interventions to improve or facilitate linkage to or retention in pre-ART (HIV) care and initiation of ART in low- and middle-income settings--a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2014; 17:19032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hoffmann C, Maubto T, Ginindza S, Fielding KL, Kubeka G, Dowdy DW, et al. Strategies to accelerate HIV care and antiretroviral therapy initiation after HIV diagnoses: a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 75:540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Amanyire G, Semitala FC, Namusobya J, Katuramu R, Kampiire L, Wallenta J, et al. Effects of a multicomponent intervention to streamline initiation of antiretroviral therapy in Africa: a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial. Lancet HIV 2016; 3:539–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Metsch LR, Feaster DJ, Gooden L, Matheson T, Stitzer M, Das M, et al. Effect of Patient Navigation With or Without Financial Incentives on Viral Suppression Among Hospitalized Patients With HIV Infection and Substance Use: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016; 316:156–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Lunze K, Kiriazova TK, Blokhina E, Gnatienko N, Wulach LA, Curnyn C, et al. Implementation of case management to link HIV-infected Russian addiction patients to HIV service. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015; 156:e136–e137. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ekstrand ML, Ramakrishna J, Bharat S, Heylen E. Prevalence and drivers of HIV stigma among health providers in urban India: implications for interventions. J Int AIDS Soc 2013; 16: 18717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Rosen S, Maskew M, Fox MP, Nyoni C, Mongwenyana C, Malete G, et al. Initiating antiretroviral therapy for HIV at a patient’s first clinic visit: the RapIT randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2016; 13:1002015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Walley AY, Cheng DM, Quinn EK, Blokhina E, Gnatienko N, Chaisson CE, et al. Fatal and non-fatal overdose after narcology hospital discharge among Russians living with HIV/AIDS who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy 2017; 39:114–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kimenko T, Kozlov A. Current state, achievements, problem aspects and prospects for developing a system of providing medical care in the field of Addiction Psychiatry. Journal of Addiction Problems 2018; 9:5–17. [Google Scholar]