Abstract

Objective

To determine the utility of biomarkers of immune activation, systemic inflammation, and coagulopathy prior to antiretroviral therapy to predict mortality during the first year of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in sub-Saharan Africa

Design

Prospective, observational cohort

Methods

We measured soluble CD14, interleukin-6, and D-dimer in non-pregnant individuals initiating ART in South Africa and Uganda in the Measuring Early Treatment Adherence (META) Study. We used survival analysis methods to estimate their association with 12-month mortality, and fit receiver operator curves (ROC) to assess the prognostic value of each biomarker.

Results

Six-hundred sixty individuals were enrolled and had pre-treatment biomarkers measured. Approximately 60% were female, with a median CD4 of 187 (IQR 111–425) and approximately half were enrolled each from South Africa and Uganda. We observed 34 deaths for a crude mortality of 5.3 deaths/100 person-years (95%CI 3.8–7.4), which ranged from 0/100py to 13.7/100py in the lowest and highest tertile of pre-treatment sCD14, respectively. In Cox models, all three biomarkers were strongly predictive of the hazard of death (AHR 3–6, all P<0.01). In multivariable models including biomarkers, both pre-treatment CD4 count and pre-treatment viral load became borderline or non-significantly associated with mortality. The c-statistic for area under ROC was higher for all three biomarkers than for CD4 count (P<0.01).

Conclusions

Biomarkers of immune activation, systemic inflammation, and coagulopathy prior to ART initiation are strongly predictive of early death on treatment after adjustment for CD4 count. Such biomarkers might serve as important prognostic indicators for patient triage in this population.

Keywords: HIV, inflammation, mortality, antiretroviral therapy, Uganda, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

Presentation to care with advanced HIV persists in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA),[1–3] despite efforts to start antiretroviral therapy (ART) regardless of disease stage.[4] Indeed, although AIDS mortality is declining in the region, approximately 25% of people continue to present with a CD4 count<200 cells/μL, and mortality rates remain between 5–10% early during treatment.[5, 6]

In the face of persistently high mortality, and in the context of expanding ART programs with limited resources, many treatment programs are adopting differentiated models of care.[7–9] These programs prioritize human and financial resources for patients at highest risk of mortality and loss from care, while simultaneously permitting stable patients to have less frequent interface with the health system. To be successful, this strategy requires development of simple and scalable tools to differentiate between these patient populations.

Biomarkers of immune activation, systemic inflammation, and coagulopathy have been previously associated with future risk of opportunistic infections, non-communicable disease, and all-cause mortality.[10–14] We sought to assess the utility of potentially scalable blood tests of systemic inflammation, immune activation, and coagulopathy for prediction of mortality in a prospectively observed longitudinal cohort of individuals in routine programmatic care in South Africa and Uganda in the current era of ART.

METHODS

Study Setting and Participants

Study participants were enrolled in the Monitoring Early Treatment Adherence Study during March 2015 – September 2016 (META, NCT02419066). The study had a primary goal to determine whether disease stage (early [CD4 >350/μL] versus late [CD4 <200/μL]) or pregnancy at the time of ART initiation impacted ART adherence or virologic suppression during the first year of therapy.[15] ART-naïve individuals over 18 years old were enrolled from publicly-operated HIV clinics in Cape Town, South Africa and southwestern Uganda at the time of ART initiation, and observed at study visits again at 6 and 12 months. To investigate causes of missed study visits, study staff performed phone calls and, if participants were not reachable, home visits. Use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), which is recommended for all individuals on ART in Uganda and for those with a CD4<200 cells/μL in South Africa, was collected via self-report in Uganda and extracted from available pharmacy databases in two of three study clinics in South Africa. Deaths were confirmed by verbal autopsy from household members, or when available, from review of medical records. Those missing from follow-up without a confirmed death were defined as lost from observation.

Laboratory Methods

At each study visit, blood was collected into EDTA tubes and tested for CD4 count (PIMA, Alere) and HIV-1 RNA viral load (Cobas Taqman platform in Uganda and the Roche CAP/CTM HIV-1 v2 assay in South Africa). Additional blood was centrifuged for plasma separation, and frozen at −80oC. Due to resource constraints that prevented us from testing the entire cohort, only non-pregnant individuals underwent additional testing of cryopreserved plasma for: 1) IL-6 (MesoScale Discovery, Rockville, MD); 2) soluble CD14 (sCD14, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); and 3) D-dimer (Diagnostica Stago, Parsippany, NY. Biomarker assays were performed at the Laboratory for Clinical Biochemistry Research at the University of Vermont.

Statistical Methods

We used survival analysis methods with a primary outcome of all-cause mortality and a secondary outcome of a composite of mortality or loss from observation. Participants were censored on their 12-month visit, their date of death (for mortality) or on their last contact with study staff (for those lost from observation). We first used Kaplan-Meier methods to graphically depict mortality and mortality/loss over observation time by tertiles of each biomarker. We then estimated crude mortality per 100 person-years by tertile of each biomarker. After noting minimal differences in mortality rates between the lowest and middle tertiles of biomarkers, we combined these two groups in regression models. We fit Cox proportional hazards models for both outcomes, both with and without additional predictors of mortality in the model, including age, sex, active smoking, pre-treatment CD4 count and pre-treatment log10 HIV-1 RNA viral load. We fit univariable models stratified by sex, CD4 count (>350 versus <200 cells μ/L), and recorded use (or not) of TMP-SMX for opportunistic infection prophylaxis among those who met criteria, and tested for an interaction term between these sub-groups and biomarker category sub-groups. We graphed log-log plots of survival versus observation time to assess for the proportional hazards assumption in both the mortality and the mortality/loss from observation models. Finally, we fit receiver operator curves for each biomarker and CD4 count as predictors of mortality in the first 12 months of observation, and compared the area under the receiver operator curve (AUROC) of each the biomarkers to CD4 count using chi-squared testing.

Ethical Considerations

Study procedures were approved by Partners Healthcare, the Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, University of Cape Town, and Western Cape province in South Africa. All participants provided written informed consent.

RESULTS

Six hundred and sixty out of 699 (95%) individuals were enrolled in the META study, completed pre-treatment biomarker testing and had a detectable VL at baseline. Approximately 60% of participants were female, with a median age of 33, a median CD4 count of 187 cells/μL, and the cohort was nearly evenly split between individuals from Uganda and South Africa (Supplemental Table 1). When divided between individuals in the lower two tertiles and the highest tertile of pre-treatment sCD14, those in the highest tertile had higher pre-treatment HIV-1 RNA viral load and lower median CD4 cell count.

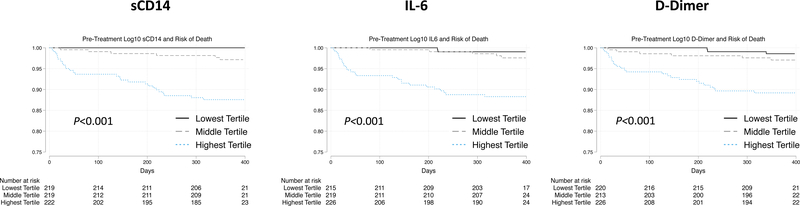

A total of 34 people (5.2%) died during observation for a crude mortality incidence of 5.3 per 100 person-years (py) (95%CI 3.8 – 7.4). An additional 12 participants (1.8%) were lost from observation. We found significant differences in mortality by tertile of pre-treatment biomarkers (all P≤0.001, Supplemental Table 2, Figure 1). For example, the mortality rates were 0/100py and 13.7/100py (9.4–20.0/100py) comparing the low with the highest tertiles of sCD14 (Supplemental Table 2). The survival curves were similar when selecting a composite of death or loss from observation as the outcome of interest (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pre-Treatment inflammatory markers and risk of mortality

In unadjusted cox proportional hazards models, pre-treatment HIV-1 RNA viral load (hazard ratio [HR] 2.05, 95%CI 1.35–3.12, P =0.001) and CD4 count (HR 0.57 for each 100 cells/μL, 95%CI 0.44–0.75, P <0.001), and each of the three biomarkers were associated with hazard of mortality (Supplemental Table 3). These patterns were similar when selecting mortality or loss from observation as the outcome of interest (Supplemental Table 4). In adjusted models, those with the highest versus the two lowest tertiles of all three biomarkers prior to treatment remained significantly associated with hazard of mortality (sCD14: AHR 5.83, 95%CI 2.19–15.34, P<0.001; IL6: AHR 4.65, 95%CI 1.90–11.36, P=0.001; D-dimer: AHR 2.87, 95%CI 1.32–6.29, P=0.01). In contrast, the effect size of both pre-treatment viral load and CD4 count diminished after addition of biomarkers to multivariable models, and all lost significance, aside from CD4 count in the D-dimer model. Moreover, the hazard of mortality for the lower two versus the highest tertile biomarkers was similar in those with low and high CD4 counts (<200 versus >350 cells/μL) and in both men and women, with interaction terms for all sub-group effects (P>0.20, Supplemental Figure 2). This finding was particularly notable for sCD14, in whom the hazard of mortality for those in the highest tertile was similar for those with a CD4 <200 and >350 cells/μL (6.28, 95%CI 2.19–18.01 versus 7.06, 95%CI 1.00–50.2, P-value for interaction term=0.95). Seventy-eight percent (354/453) of those meeting criteria had recorded use of TMP-SMX at enrollment. The crude mortality rate was significantly higher in those who did not receive TMP-SMX (15.8 deaths/100py versus 3.2 deaths/100py, P-value < 0.001). Although the predictive nature of the biomarkers was somewhat diminished, we found no significant differences in the prognostic value of the biomarkers in those who did versus did not have TMP-SMX use recorded (Supplemental Table 5, Supplemental Figure 2).

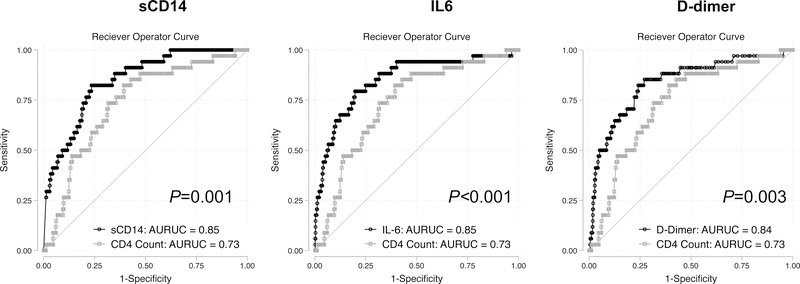

Log-log plots of the inflammatory markers demonstrated largely parallel plots consistent with the proportional hazard assumption (Supplemental Figure 3). Finally, we found that the AUROC for prediction of 12-month mortality was higher for each of the three biomarkers than for CD4 count (sCD14: 0.85 [0.7–0.91]; IL6: 0.85 [0.78–0.92]; D-dimer: 0.84 [0.76–0.91]; CD4 count: 0.74 [0.66–0.81]; P-value for all comparisons versus CD4 count <0.01, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Receiver operator curves for prediction of all-cause mortality in first 12-months of therapy for pre-treatment soluble biomarkers of inflammation, immune activation and coagulation versus pre-treatment CD4 count

DISCUSSION

Herein we demonstrate that biomarkers of immune activation, systemic inflammation, and coagulopathy are highly predictive of mortality in the first 12 months of HIV therapy in South Africa and Uganda, and might serve as efficient prognostic indicators for patients initiating therapy. All three biomarkers evaluated had higher discriminatory prediction of 12-month mortality than CD4 count based on AUROC and each remained significantly predictive of mortality in people with low CD4 counts. For example, those in the highest tertile of sCD14 prior to ART had approximately a 7-fold increase in mortality than those in the two lowest tertiles, irrespective of CD4 count, and the mortality rate in the lowest versus high tertile was 0/100py versus 13.7/100py. Moreover, in adjusted models, the biomarkers remained predictive of mortality, whereas both pre-treatment CD4 count and pre-treatment viral load had much lower and largely non-significant effect sizes.

There has been strong interest in scalable strategies to differentiate HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa, where there are goals to retain over 25 million people in chronic care.[9] Because such programs focus on “stepped-down care” for stable and low-risk care, a critical element of their success is an ability to accurately identify patients at greatest risk for opportunistic infections and early mortality. In practice, most programs rely upon CD4 count to make determinations about risk of opportunistic infections. Yet, our data suggest that certain biomarkers, such as D-dimer and sCD14, might better discriminate between those with the highest risk of mortality. A critical next step will be to determine if such biomarkers can also triage high-risk patients for additional testing and/or closer observation to ultimately improve outcomes.

Multiple prior studies have investigated the use of a variety of other prognostic indicators, such as albumin and blood indices, for identifying those at risk of early mortality.[17, 18] Although many of these studies have found markers associated with death, they largely demonstrate adjusted effect sizes for increased odds or hazard of mortality in the range of 10–30%. In contrast, both in this analysis and in prior studies in the region,[11] pre-treatment biomarkers of inflammation and systemic inflammation appear to predict a 300–500% increased risk of early mortality. These effect sizes are similar or larger than other frequently used biomarkers for disease prognostication. For example, similar differences in mortality of 2–4 fold and AUROC in the range of 0.6–0.8 are characteristic of scores to predict in-hospital mortality with sepsis.[19] Importantly, point-of-care assays for D-dimer and sCD14 have been developed and validated, and thus could be potentially adopted as scalable and clinically implementable assays if their prognostic value can be corroborated.[20, 21]

Our study was limited by the use of retrospective testing of cryopreserved plasma for biomarkers in a central laboratory, which prevents us from extrapolating our results into clinical practice. We also lacked data on incident opportunistic infections or adjudicated causes of death, which were not within the scope of the parent study, so we could not directly determine if the biomarkers examined were efficient surrogates of preventable causes of death. A strength of our study was near complete assessment of survival, with only 12 (2%) of participants lost from observation, and models which allocated these individuals as failures did not substantially affect our results. Future work should evaluate the use of biomarkers to triage patients at high-risk for adverse clinical outcomes in early treatment. A particularly important question is whether identification of such patients, and providing them with enhanced clinical oversight, can result in lower mortality rates. If so, and if such biomarkers can be made available at cost and scale, they could serve a key role in promotion of differentiated models of care to optimize use of scarce resources as HIV treatment programs scale in sub-Saharan Africa.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all study participants for the involvement in the study, and the study staff including: Research Assistants: Nomakhaya April (RN), Alienah Mpahleni, Vivie Situlo, Speech Mzamo, Nomsa Ngwenya, Khosi Tshangela Regina Panda, Teboho Linda, Christine Atwiine, Sheila Moonight, Edna Tindimwebwa, Nicholas Mugisha, Peace Atwogeire, Dr. Vian Namana, Catherine Kyampaire, Gabriel Nuwagaba; Program Managers: Annet Kembabazi, Stephen Mugisha, Victoria Nanfuka, Anna Cross, Nicky Kelly, Daphne Moralie, Kate Bell; Statistician: Nicholas Musinguzi; Data Managers: Dolphina Cogill, Justus Ashaba, Zoleka Xapa, Mathias Orimwesiga, Elly Tuhanamagyezi, Catherine Kyampaire; Lab Managers: Don Bosco Mpanga, Leonia Kyarisima, Simone Kigozi

Funding

This work was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP113634). The authors acknowledge the following additional sources of support: K23 MH099916.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors report no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Siedner MJ, Ng CK, Bassett IV, Katz IT, Bangsberg DR, Tsai AC. Trends in CD4 count at presentation to care and treatment initiation in sub-Saharan Africa, 2002–2013: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60(7):1120–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collaborations IaARTC, Avila D, Althoff KN, Mugglin C, Wools-Kaloustian K, Koller M, et al. Immunodeficiency at the start of combination antiretroviral therapy in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 65(1):e8–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osler M, Hilderbrand K, Goemaere E, Ford N, Smith M, Meintjes G, et al. The Continuing Burden of Advanced HIV Disease Over 10 Years of Increasing Antiretroviral Therapy Coverage in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(suppl_2):S118–S125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization; Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. 2nd ed. 2016. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/arv-2016/en/ Accessed 13 January 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan AT, Long L, Useem J, Garrison L, Fox MP. Mortality in the First 3 Months on Antiretroviral Therapy Among HIV-Positive Adults in Low- and Middle-income Countries: A Meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 73(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farahani M, Price N, El-Halabi S, Mlaudzi N, Keapoletswe K, Lebelonyane R, et al. Trends and determinants of survival for over 200 000 patients on antiretroviral treatment in the Botswana National Program: 2002–2013. AIDS 2016; 30(3):477–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker C, Dutta A, Klein K. Can differentiated care models solve the crisis in HIV treatment financing? Analysis of prospects for 38 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society 2017; 20(Suppl 4):21648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes CB, Sanne I. Changing models of care to improve progression through the HIV treatment cascade in different populations. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS 2015; 10(6):447–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grimsrud A, Bygrave H, Doherty M, Ehrenkranz P, Ellman T, Ferris R, et al. Reimagining HIV service delivery: the role of differentiated care from prevention to suppression. Journal of the International AIDS Society 2016; 19(1):21484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuller LH, Tracy R, Belloso W, De Wit S, Drummond F, Lane HC, et al. Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers and mortality in patients with HIV infection. PLoS Med 2008; 5(10):e203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ledwaba L, Tavel JA, Khabo P, Maja P, Qin J, Sangweni P, et al. Pre-ART levels of inflammation and coagulation markers are strong predictors of death in a South African cohort with advanced HIV disease. PLoS One 2012; 7(3):e24243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunt PW, Lee SA, Siedner MJ. Immunologic Biomarkers, Morbidity, and Mortality in Treated HIV Infection. J Infect Dis 2016; 214 Suppl 2:S44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S, Byakwaga H, Boum Y, Burdo TH, Williams KC, Lederman MM, et al. Immunologic Pathways that Predict Mortality in HIV-Infected Ugandans Initiating ART. J Infect Dis 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byakwaga H, Boum Y, 2nd, Huang Y, Muzoora C, Kembabazi A, Weiser SD, et al. The kynurenine pathway of tryptophan catabolism, CD4+ T-cell recovery, and mortality among HIV-infected Ugandans initiating antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2014; 210(3):383–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haberer JE, Bwana BM, Orrell C, Asiimwe S, Amanyire G, Musinguzi N, et al. ART adherence and viral suppression are high among most non-pregnant individuals with early-stage, asymptomatic HIV infection: an observational study from Uganda and South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society 2019; 22(2):e25232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peeling RW, Ford N. Reprising the role of CD4 cell count in HIV programmes. Lancet HIV 2017; 4(9):e377–e378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siika A, McCabe L, Bwakura-Dangarembizi M, Kityo C, Mallewa J, Berkley J, et al. Late Presentation With HIV in Africa: Phenotypes, Risk, and Risk Stratification in the REALITY Trial. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(suppl_2):S140–S146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bisson GP, Ramchandani R, Miyahara S, Mngqibisa R, Matoga M, Ngongondo M, et al. Risk factors for early mortality on antiretroviral therapy in advanced HIV-infected adults. AIDS 2017; 31(16):2217–2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raith EP, Udy AA, Bailey M, McGloughlin S, MacIsaac C, Bellomo R, et al. Prognostic Accuracy of the SOFA Score, SIRS Criteria, and qSOFA Score for In-Hospital Mortality Among Adults With Suspected Infection Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. JAMA 2017; 317(3):290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato M, Takahashi G, Shibata S, Onodera M, Suzuki Y, Inoue Y, et al. Clinical Performance of a New Soluble CD14-Subtype Immunochromatographic Test for Whole Blood Compared with Chemiluminescent Enzyme Immunoassay: Use of Quantitative Soluble CD14-Subtype Immunochromatographic Tests for the Diagnosis of Sepsis. PLoS One 2015; 10(12):e0143971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geersing GJ, Janssen KJ, Oudega R, Bax L, Hoes AW, Reitsma JB, et al. Excluding venous thromboembolism using point of care D-dimer tests in outpatients: a diagnostic meta-analysis. BMJ 2009; 339:b2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.