While smoking rates have decreased (from 20.9% of US adults in 20051 to 14.0% in 20172), tobacco companies have responded by introducing alternative tobacco products, such as electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) into the global market.3

Tobacco companies claim a need for messaging that informs the public of relative risks of alternative tobacco products compared to traditional combustible cigarettes.4,5 In order to be able to market alternative tobacco products with reduced risk claims in the US, tobacco companies must submit a Modified Risk Tobacco Product (MRTP) application with evidence demonstrating that “the product will or is expected to benefit the health of the population as a whole.”6,7 As of March 2020, there have been five sets of MRTP applications accepted for review by the FDA for various tobacco products, and companies have expressed intentions to submit MRTP applications for e-cigarettes.8

In the current MRTP applications, tobacco companies allege consumers overestimate the risk of potential MRTPs.9,10 They cited previous studies by independent researchers showing that a large proportion of the population perceives potential MRTPs as equally or more harmful than cigarettes, and argue misperceptions need to be corrected using modified risk claims.11–15 However, the studies cited predominantly used one specific measurement of comparative risk referred to as the direct questioning approach, utilizing a single question to measure relative risk (e.g., “Compared to cigarettes, is product X less harmful, equally harmful, or more harmful?”). An alternative approach that uses indirect questioning (respondents answer separate questions measuring absolute risk perceptions of two products and then these ratings are compared) results in a larger proportion of respondents assessing alternative nicotine products as less harmful than cigarettes.16,17

Several studies have compared direct and indirect relative risk perceptions between cigarettes and other tobacco products.18–20 However, these studies were conducted prior to 2017, when pod-based e-cigarettes that use nicotine salts were less prevalent. The product landscape and patterns and prevalence of product use have changed significantly since then. Few studies that explored perceptions of harm related to pod-based devices are available.21,22 Therefore, up-to-date research is needed in order to elucidate whether perceptions have changed along with the emergence of novel e-cigarettes. As products continue to change, there remains a need to better understand how to accurately assess perceptions of e-cigarette harms.17 We extend the current literature comparing these two approaches for measuring risk perceptions to a more recent, representative sample of US adult smokers and non-smokers and include a category for those that responded “I don’t know” (which was rarely included in the previous studies23). The goal is to enhance understanding of the difference between direct and indirect risk perceptions in relation to cigarette and e-cigarette use.

Methods

The data come from the 2017 Tobacco Products and Risk Perceptions Survey, a national cross-sectional survey of adults aged 18 and older in the US. The survey was administered online in August – September 2017 by GfK, an independent market research group. Of the 8229 invited panelists selected with probabilities proportional to size after application of the panel demographic poststratification weight, 6033 (73.3%) were “qualified completers”. After data cleaning, 5992 participants were retained for analyses (see Nyman et al., 2018).24

Perceived comparative risk was measured in two ways: direct (single question) and indirect (separately for each product). The direct question asked: “Is using electronic vapor products less harmful, about the same, or more harmful than smoking regular cigarettes?” Answers were categorized as less harmful (“much less harmful” and “less harmful” combined), equally harmful (“about the same level of harm”), more harmful (“more harmful” and “much more harmful”) and “I don’t know”.

For the indirect measure, participants were asked the same question for cigarettes and e-cigarettes: “Imagine that you just began smoking cigarettes [using electronic vapor products] every day. What do you think your chances are of having each of the following happen to you if you continue to smoke cigarettes [use electronic vapor products] every day?: (1) Lung Cancer; (2) Lung disease other than lung cancer (such as COPD and emphysema); (3) Heart disease; (4) Early/Premature Death.” Responses ranged from ‘0 – No chance’ to ‘6 – Very good chance’ or participants could respond “I don’t know.” For each participant, we created a perceived harm of cigarettes score by averaging the items related to risk of cigarette harms and, similarly, a perceived harm of e-cigarettes score. We then subtracted the perceived harm of e-cigarettes from perceived harm of cigarettes to get an indirect comparative harm score. We recoded the scores into three categories: e-cigarettes as “less harmful”, “equally harmful” and “more harmful” than cigarettes. Only participants who answered “I don’t know” to all four questions related to cigarette harms and/or all four e-cigarette harms were categorized as “Don’t Know”. Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS with the Complex Samples module (V.25).25

Results

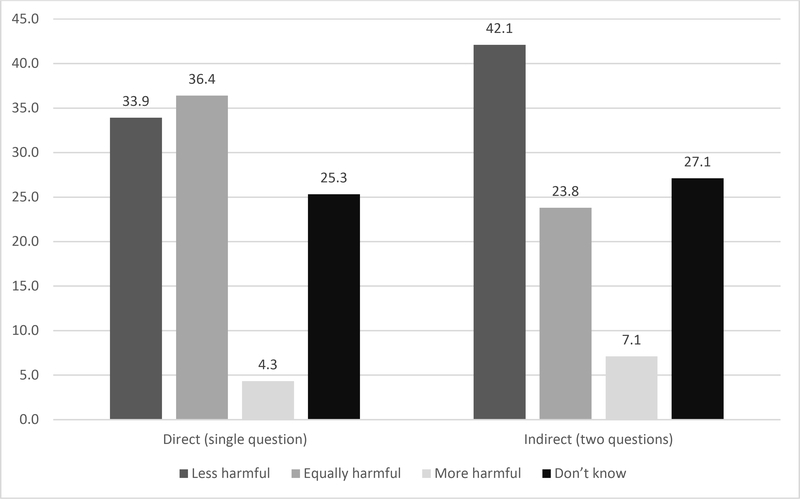

When asked to compare harms of e-cigarettes and cigarettes directly (one question), 33.9% (95% CI 32.5% to 35.5%) of participants identified e-cigarettes as less harmful than cigarettes, 36.4% (95% CI 34.9% to 38.0%) reported equal harm, 4.3% (95% CI 3.7% to 5.0%) said e-cigarettes were more harmful, and 25.3% (95% CI 24.0% to 26.7%) didn’t know (Figure 1). When asked indirectly (separate questions), 42.1% (95% CI 40.4% to 43.7%) identified e-cigarettes as less harmful than cigarettes, 23.8% (95% CI 22.4% to 25.3%) reported equal harm, 7.1% (95% CI 6.2% to 8.0%) perceived e-cigarettes to be more harmful and 27.1% (95% CI 25.7% to 28.6%) didn’t know. The mean indirect score for all participants was −0.95 (95% CI −1.0 to −0.89) indicating that on average, smokers and non-smokers in the U.S. perceive e-cigarettes as less harmful than cigarettes. The correlation between the indirect and direct comparative risk scores was 0.4 (Spearman’s rho, p<0.001).

Figure 1:

Direct Comparative Risk (one-question) compared to Indirect Comparative Risk (twoquestions) of e-cigarette harms compared to cigarettes among all participants (current smokers, former smokers, and never smokers)

When examined by smoking status (self-reported as current smoker [smoked ≥100 cigarettes in his/her lifetime and currently smokes some days or every day], former smoker, or never smoker) the results are similar for all groups (see Supplemental Materials), suggesting that adults, regardless of tobacco use history, are more likely to assess e-cigarettes as less harmful than cigarettes when asked indirectly than when asked to make a direct comparison in a single question.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess whether this finding changed when we increased the range of difference values classified “equally harmful” for the indirect approach from exactly zero to a range from −0.5 to 0.5. This re-classification altered the results: 35.4% (95% CI 33.9% to 37.0%) identified e-cigarettes as less harmful than cigarettes, 33.7% (95% CI 32.2% to 35.3%) said they were of equal harm, and 3.7% (95% CI 3.1% to 4.4%) perceived e-cigarettes to be more harmful (see Supplemental Materials).

Discussion

We found that the estimated proportion of US adults that perceive using e-cigarettes as less harmful than smoking cigarettes depended on whether an indirect measure (42.1%) or direct measure (33.9%) was used and that the two measures were only moderated correlated. This finding supports that public knowledge of the potential harms of e-cigarettes is limited. This is also consistent with the current state of the literature, which is lacking evidence on the long-term health impacts.26–28

The discrepancy we found between the direct and indirect measures was less pronounced than in other studies.19,20 The greater discrepancies found in or inferred by prior research might be due less to inherent differences between indirect and direct approaches and more to whether studies allowed a “don’t know” response or how they implemented the indirect approach (e.g., the scale for the absolute harm/risk measures). Recent research has shown that, even when asked indirectly, the percentage of US adults who perceive e-cigarettes as less harmful than cigarettes is smaller than in previous studies, suggesting the public’s perceptions of e-cigarette harms may be changing over time.29

The differences in how the questions used to measure direct and indirect perceptions could have changed how the participants interpreted and responded to the questions, as demonstrated by the moderate correlation in both the main analysis (Spearman’s rho = 0.42) and the sensitivity analysis (Spearman’s rho = 0.43).

Limitations

We were limited by the direct and indirect questions used in the survey. We calculated the indirect risk score using an average of the four health risks to increase comparability with the direct risk question. The categorization for indirect questions could be done differently and we conducted sensitivity analyses for one alternative way for calculating the “equally harmful” category and presented the raw indirect scores in the Supplement for transparency.

Conclusion

Our study, combined with the previous literature, suggests the need to utilize both direct and indirect risk questions when assessing the public’s perceptions of harms of novel tobacco products. Tobacco companies and researchers that maintain the position that adults do not understand the reduced harm of e-cigarettes should consider reporting on both on the indirect and direct responses to comparative harms questions. This is particularly pertinent to the MRTP applications; those that only provide one type of comparative risk measurement may not capture the full picture of risk perceptions and may hinder regulators from properly evaluating the population-level impact of the modified risk tobacco products.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Victoria Churchill, Georgia State University School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA USA.

Amy L. Nyman, Georgia State University School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA USA.

Scott Weaver, Georgia State University School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA USA.

Bo Yang, University of Arizona Department of Communication, Tucson, AZ USA.

Jidong Huang, Georgia State University School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA USA.

Lucy Popova, Georgia State University School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA USA.

References

- 1.Jamal A, King BA, Neff LJ, Whitmill J, et al. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2005–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(44):1205–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang TW, Asman K, Gentzke AS, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(44):1225–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamin CK, Bitton A, Bates DW. E-cigarettes: a rapidly growing Internet phenomenon. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(9):607–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altria Client Services LLC. Effect of marketing on consumer understanding and perceptions. USSTC MRTP Application for Copenhagen® Snuff Fne Cut. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philip Morris Products S.A. Consumer understanding and perceptions. Modified Risk Tobacco Product Application for Tobacco Heating Systems (THS) - IQOS with Marlboro HeatSticks. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Food and Drug Administration. Vaporizers, E-Cigarettes, and other Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS). 2019; https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/ProductsIngredientsComponents/ucm456610.htm (Accessed April 2019).

- 7.US Food and Drug Administration. Modified Risk Tobacco Products. 2019; https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/MarketingandAdvertising/ucm304465.htm. (Accessed April 2019).

- 8.Donahue TS. At the forefront. Tobacco Reporter 2017; https://www.tobaccoreporter.com/2017/12/at-the-forefront/ (Accessed April 2019).

- 9.US Smokless Tobacco Company LLC. Application for Copenhagen® Snuff Fine Cut, a Loose Moist Snuff Tobacco Product. Modified Risk Tobacco Product Application. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. Applications for Six Camel Snus Smokeless Tobacco Products. Modified Risk Tobacco Product Application. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Connor RJ, Hyland A, Giovino GA, et al. Smoker awareness of and beliefs about supposedly less-harmful tobacco products. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(2):85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connor RJ, McNeill A, Borland R, et al. Smokers’ beliefs about the relative safety of other tobacco products: findings from the ITC collaboration. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(10):1033–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith SY, Curbow B, Stillman FA. Harm perception of nicotine products in college freshmen. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(9):977–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomar SL, Hatsukami DK. Perceived risk of harm from cigarettes or smokeless tobacco among U.S. high school seniors. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(11):1191–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haddock CK, Lando H, Klesges RC, et al. Modified tobacco use and lifestyle change in risk-reducing beliefs about smoking. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(1):35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czoli CD, Fong GT, Mays D, et al. How do consumers perceive differences in risk across nicotine products? A review of relative risk perceptions across smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, nicotine replacement therapy and combustible cigarettes. Tob Control. 2017;26(e1):e49–e58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson LA, Creamer MR, Breland AB, et al. Measuring perceptions related to e-cigarettes: Important principles and next steps to enhance study validity. Addict Behav. 2018;79:219–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Popova L, Ling PM. Perceptions of Relative Risk of Snus and Cigarettes Among US Smokers. Am J Pub Health. 2013;103(11):e21–e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wackowski OA, Bover Manderski MT, Delnevo CD. Comparison of Direct and Indirect Measures of E-cigarette Risk Perceptions. Tob Regul Sci. 2016;2(1):38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Persoskie A, O’Brien EK, Nguyen AB, et al. Measuring youth beliefs about the harms of e-cigarettes and smokeless tobacco compared to cigarettes. Addict Behavs. 2017;70:7–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vallone DM, Bennett M, Xiao H, et al. EC. Prevalence and correlates of JUUL use among a national sample of youth and young adults. Tob Control. 2019;28(6):603–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKelvey K, Baiocchi M, Halpern-Felsher B. Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Use and Perceptions of Pod-Based Electronic Cigarettes. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183535–e183535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Persoskie A, O’Brien EK, Poonai K. Perceived relative harm of using e-cigarettes predicts future product switching among US adult cigarette and e-cigarette dual users. Addiction. 2019;114(12):2197–2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyman AL, Weaver SR, Popova L, et al. Awareness and use of heated tobacco products among US adults, 2016–2017. Tob Control. 2018;27(Suppl 1):s55–s61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. E-Cigarettes: a scientific review. Circulation. 2014;129(19):1972–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhatnagar A Cardiovascular Perspective of the Promises and Perils of E-Cigarettes. Circulation. 2016;118(12):1872–1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Cancer Society. What Do We Know About E-cigarettes? 2018; https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/tobacco-and-cancer/e-cigarettes.html. Accessed April 2019.

- 29.Huang J, Feng B, Weaver SR, et al. Changing Perceptions of Harm of e-Cigarette vs Cigarette Use Among Adults in 2 US National Surveys From 2012 to 2017Changing Perceptions of Harm of e-Cigarette Use Among Adults in 2 US National Surveys, 2012–2017Changing Perceptions of Harm of e-Cigarette Use Among Adults in 2 US National Surveys, 2012–2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e191047–e191047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.