Abstract

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are tissue-resident effectors poised to activate rapidly in response to local signals such as cytokines. To preserve homeostasis, ILCs must employ multiple pathways, including tonic suppressive mechanisms, to regulate their primed state and prevent inappropriate activation and immunopathology. Such mechanisms remain incompletely characterized. Here we show that cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein (CISH), a suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) family member, is highly and constitutively expressed in type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s). Mice that lack CISH either globally or conditionally in ILC2s show increased ILC2 expansion and activation, in association with reduced expression of genes inhibiting cell cycle progression. Augmented proliferation and activation of CISH-deficient ILC2s increases basal and inflammation-induced numbers of intestinal tuft cells and accelerates clearance of the model helminth, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, but compromises innate control of Salmonella typhimurium. Thus, CISH constrains ILC2 activity both tonically and after perturbation, and contributes to the regulation of immunity in mucosal tissue.

Introduction:

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are poised effectors that are seeded into peripheral tissues during fetal development, where they can subsequently activate rapidly in response to local perturbations. Three major subsets of ILCs have been identified, classified according to their cytokine outputs and their similarity to the major subsets of helper T cells: type 1 innate lymphoid cells (ILC1s) which share features and function with type 1 helper T cells (Th1); type 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3s) which resemble Th17 cells; and type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), which share similarities with Th2 cells1. ILC2s are activated by diverse signals, including eicosanoids, neuropeptides, and hormones, as well as cytokines like interleukin (IL)-25, IL-33, IL-18, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), to rapidly secrete type 2 cytokines like IL-13, IL-9, GM-CSF, and IL-51, 2.

The differentiation and positioning of ILCs in peripheral tissues enables them to respond quickly to local perturbations by recruiting other immune cells and inducing coordinated responses among stromal and epithelial cells. Lacking the antigen-specific receptors used by adaptive lymphocytes, ILCs require alternative mechanisms to ensure activation is limited to appropriate contexts. Natural killer (NK) cells, ILC1s, and NK cell receptor (NCR)+ ILC3s utilize a well-characterized array of activating and inhibitory surface receptors that provide antigen-independent checkpoints to activation3, 4. Similarly, ILC2s are inhibited by a variety of exogenous cues, such as ligation of KLRG11, cytokines such as IL-12, IL-27, or type I or II interferons5, 6, and neurotransmitters such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)7 and adrenergics8. However, apart from A20, which negatively regulates IL-25 signaling9, endogenous mechanisms that regulate ILC2 activity are less well characterized.

The SOCS proteins include 8 members (SOCS1–7 and CISH) that are upregulated in response to cytokines or other activating signals to negatively regulate the magnitude and duration of such signals. SOCS proteins inhibit cytokine signaling through various mechanisms, including inactivation of Janus kinases (JAKs) downstream of cytokine receptors, interfering with binding of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) to cytokine receptors, and ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation of signaling intermediates10. CISH, also called CIS, was first identified as an early response gene induced by growth factors such as erythropoietin, thrombopoietin, IL-2, and IL-3 that signal through STAT511. CISH blunts signaling downstream of these receptors in part by blocking STAT5 binding to the relevant cytokine receptors, and by promoting receptor complex ubiquitination and degradation11–13. Subsequent investigations have also identified non-STAT5-dependent stimuli that induce CISH expression in diverse cell types10, including following T cell receptor (TCR) ligation where CISH is thought to dampen TCR signaling through interactions with phospholipase C (PLC)-γ114.

Consistent with the general inhibitory functions of SOCS proteins, studies of mice that are completely or selectively deficient in CISH have shown increased activation of targeted cell types. Conditional knockout of CISH led to increased interferon-γ production and augmented anti-tumor responses in CD8+ T cells14 or NK cells15. In the case of NK cells, this related to enhanced metabolic fitness that favored survival and proliferation under conditions of limiting cytokines like IL-2 and IL-1516. In addition to generalized inhibition, some reports suggest that CISH imparts differential control across activation programs in the same cells. For instance, selective knockout of CISH in dendritic cells augmented their proliferation but reduced their ability to activate cytotoxic T lymphocytes17. Curiously, mice with global CISH deficiency developed spontaneous allergic pulmonary disease as they age, and selective knockout of CISH in CD4+ T cells led to T cell hyperactivation with a bias towards Th2/Th9 differentiation18. Thus, CISH appears to regulate many outputs, but may be particularly important in vivo in constraining type 2 polarization. With this background, we sought to characterize the role of CISH in ILC2s.

Results:

Cish is highly and constitutively expressed in tissue-resident ILC2s.

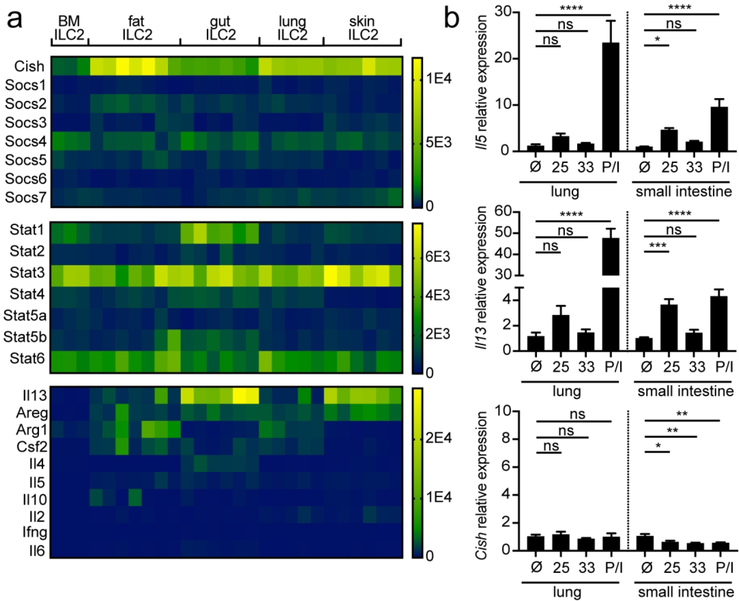

Analysis of datasets at ImmGen19 revealed that Cish is highly expressed in ILC2s as compared to other tissue-resident lymphocytes (Supplementary Figure 1a). To validate and further explore this observation, we mined bulk RNA sequencing of sorted ILC2s and other lymphocytes previously performed in our lab20. Cish was the most highly expressed SOCS family member in ILC2s in all tissues examined (Figure 1a). Cish was also highly expressed in ILC2s as compared to CD4+ T cells or Tregs (Supplementary Figure 1b–c), independently corroborating the ImmGen data. Expression of Cish was higher in ILC2s from peripheral tissues than in ILC2s from bone marrow and accompanied the increased expression of canonical ILC2 effector genes (Figure 1a). Because CISH and other SOCS family proteins interfere with JAK-STAT signaling in multiple cell types, we also examined STAT family transcripts in ILC2s. Stat1 transcripts correlated inversely with Cish transcripts across tissue ILC2s (Figure 1a).

Figure 1: CISH is highly and constitutively expressed in tissue resident ILC2s.

a. RNA sequencing of purified ILC2s from indicated tissues. Legend colors indicate counts per million reads.

b. Induction of Il5 and Il13 but not Cish in cultured ILC2s from lung or SI treated with 10 ng/mL of IL-25 or IL-33, or PMA/ionomycin.*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 for one-way ANOVA with Dunnett testing for multiple comparisons. n = 3 wells/stimulation, each derived from a single pool of ILC2s isolated from 6 mice.

Because Cish was initially discovered as an early inducible transcript in stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells, we considered whether CISH might be induced in ILC2s during stimulation. ILC2s can be activated by multiple cytokines, including TSLP, IL-25, and IL-33, which have been shown to coordinately regulate the basal output of ILC2s in vivo20. However, Cish expression in tissue ILC2s isolated from mice lacking signaling from these three cytokines (“TKO”) was not consistently decreased compared to ILC2s from WT mice (Supplementary Figure 1d). Consistent with this finding, when we stimulated ILC2s from lung or small intestine with IL-25, IL-33, or PMA/ionomycin ex vivo, transcripts for prototypical ILC2 effector cytokines such as IL-5 and IL-13 were readily induced by activation, whereas Cish mRNA was not (Figure 1b). Thus, CISH is highly and constitutively expressed in tissue ILC2s and not further induced following activation by tissue cytokines under these conditions.

CISH deficiency in ILC2s augments ILC2 responses and accelerates helminth clearance

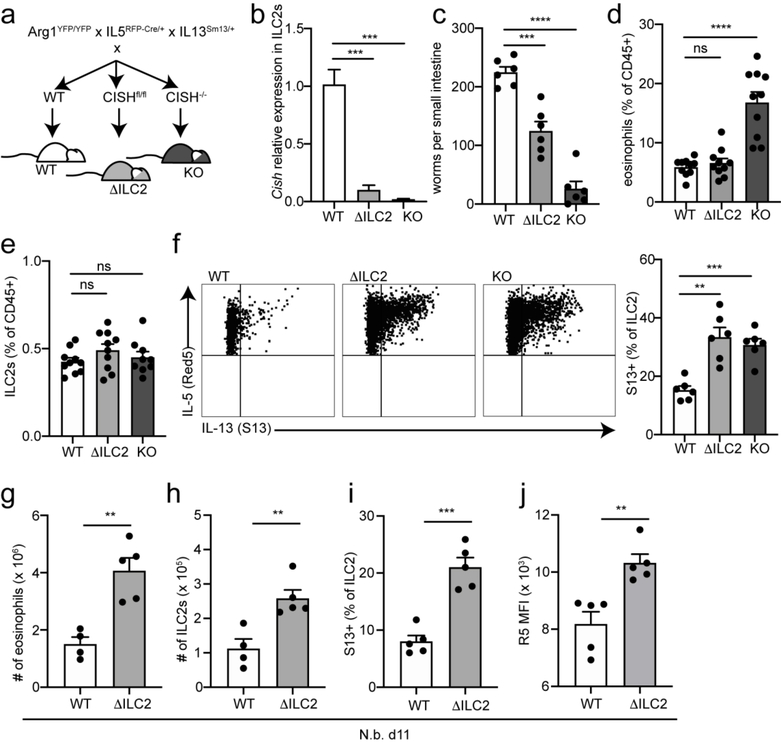

To examine the role for CISH in modulating ILC2 responses, we examined cells from tissues with global CISH deficiency, or with CISH-deficiency in IL-5+ cells, which largely consist of ILC2s in uninfected mice (Figure 2a). Deletion of CISH in ILC2s using IL-5-Cre was efficient (Figure 2b, Supplementary Figure 2a), and did not result in compensatory upregulation of other SOCS family members (Supplementary Figure 2b). We challenged ILC2 conditional CISH knockout mice (“ΔILC2”) or global CISH knockout mice (“KO”) with the parasitic helminth Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (N.b.) to activate ILC2s21. As assessed 5 days after infection, KO mice had almost completely cleared intestinal organisms, while wildtype (WT) mice had ~200 remaining worms (Figure 2c). ΔILC2 mice exhibited accelerated worm clearance that was intermediate between WT and KO mice at this timepoint (Figure 2c). Eosinophils, which are recruited and activated by ILC2s22–24, were significantly increased in lungs from infected KO mice as compared to WT mice, although this did not occur in ΔILC2 mice at this time point (Figure 2d).

Figure 2: Knockdown of CISH in ILC2s leads to augmented ILC2 responses and accelerated helminth clearance.

a. Breeding strategy using IL5RFP-Cre (R5) to report on IL-5 expression and conditionally knockout CISH on ILC2s.

b. Efficient R5-mediated deletion of Cish mRNA on sorted lung ILC2s. ***p<0.001 for one-way ANOVA with Dunnett testing for multiple comparisons. n=3 mice/group.

c. Number of small intestinal N.b. worms counted on day 5 of infection with N.b. ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 for one-way ANOVA with Dunnett testing for multiple comparisons. n=6 mice/group. Representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

d. Eosinophils from lungs of N.b.-infected mice of indicated genotypes on day 5. Eosinophils were gated as CD45+, SigF+, CD11b+, live cells. ***p<0.001 for Brown-Forsythe and Welch ANOVA with Dunnett correction for multiple comparison. “ns”= non-significant. n = 8–10 mice/group. Represents combined data from 2 of 3 similar experiments.

e. ILC2s from lungs of N.b.-infected mice on day 5 as in (d). n = 8–10 mice/group; represents combined data from 2 of 3 similar experiments.

f. Representative flow cytometry plots (left panels) and corresponding quantification (bar graph, right panel) of S13 expression on ILC2s from mice in (c-e). ILC2s were gated as lin−, Thy1.2+, Arg1YFP+, R5+. ***p<0.001, **p<0.01 for Brown-Forsythe and Welch ANOVA with Dunnett correction for multiple comparison. “ns”= non-significant. n = 6 mice/group. Representative of at least 3 similar experiments.

g. Number of eosinophils from lungs of N.b.-infected mice on day 11.

h. Number of ILC2s from lungs of N.b.-infected mice on day 11.

i. S13 expression on ILC2s from lungs of N.b.-infected mice on day 11.

j. R5 MFI from d11 N.b.-infected mice. For (g-j), **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by 2-tailed t-test. n=5 mice/group.

The frequency of lung ILC2s in infected mice was not yet increased in CISH-deficient mice by day 5 (Figure 2e), and similar to that in infected WT mice21, 25. However, ILC2s from both ΔILC2 and KO mice had increased production of IL-13 (Figure 2f) and ΔILC2 and KO mice had increased plasma IL-5 at day 5 as compared to WT mice (Supplementary Figure 2c). By day 11 of infection, a timepoint that approaches peak ILC2 activation in the lung of WT mice26, infected ΔILC2 mice had increased lung eosinophils, increased ILC2 numbers, and increased IL-5 and IL-13 expression by lung ILC2s as compared to WT mice, consistent with a role for CISH in restraining ILC2 activity in response to tissue perturbation (Figure 2g–j).

Because conditional knockout of CISH in ILC2s only partially recapitulated the accelerated N.b. larval clearance observed in global KOs (Figure 2c), and because T cells are also known to be important for clearance of N.b.21, we examined a role for T cells as targets of regulation by CISH. Mice with CD4-Cre-driven conditional knockout of CISH in T cells (“ΔCD4”) also had an intermediate reduction in the level of intestinal worms at day 5 (Supplementary Figure 2d), resembling that seen in the infected ΔILC2 mice. Like deletion of CISH in ILC2s, deletion of CISH in T cells did not lead to the increase in early pulmonary eosinophils observed in infected CISH KO mice (Supplementary Figure 2e). In contrast to CISH-deficient ILC2s, neither ILC2s nor CD4+ T cells from infected ΔCD4 mice exhibited increased IL-13 expression (Supplementary Figure 2f).

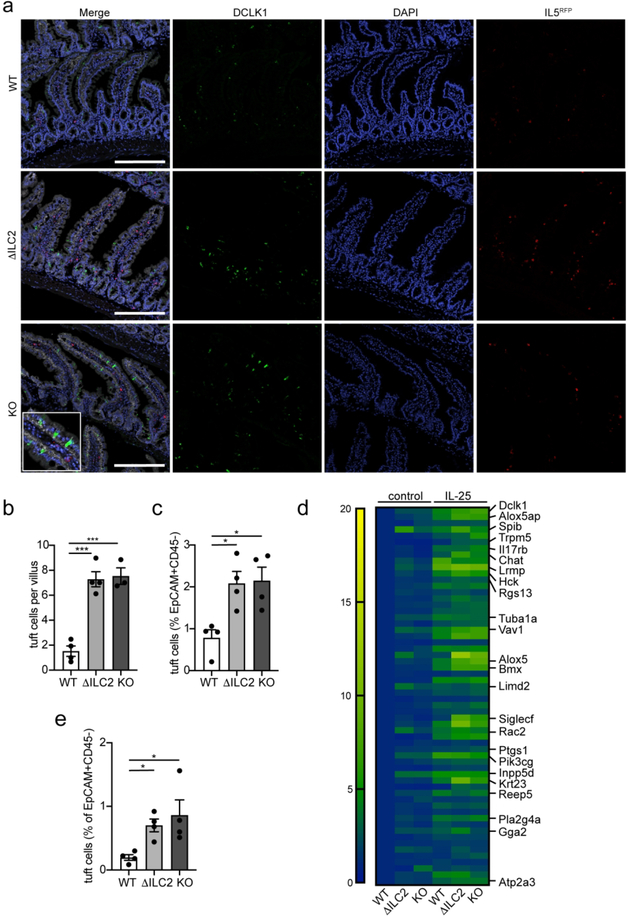

Deficiency of CISH in ILC2s leads to an increase in intestinal tuft cells

Intestinal expulsion of N.b. is accomplished through coordinated cross-talk between epithelial tuft cells and ILC2s, which together form an amplifying immune circuit27–29. In this circuit, ILC2-derived IL-13 drives the intestinal epithelium towards secretory lineages, increasing the number of tuft and goblet cells, and resulting in the “weep and sweep” response that accompanies parasite clearance. We hypothesized that CISH deficiency in ILC2s may contribute to accelerated helminth clearance by augmenting tuft cell activity or numbers in the small intestine. Quantifying tuft cells from the proximal intestine of N.b.-infected ΔILC2 mice revealed a trend towards increased tuft cell numbers at the early phase (day 3) of the infection that was lost at the peak of tuft cell accumulation (day 11) (Supplementary Figure 3a). Since small intestinal tuft cell numbers reflect the activation of ILC2s by IL-25 from tuft cells themselves27, 30, we directly assessed the effects of CISH deficiency after treatment with exogenous IL-25, as previously described26, 31. Indeed, ΔILC2 or global KO mice treated with 3 daily doses of IL-25 had increased numbers of jejunal tuft cells compared to WT mice (Figure 3a–c). Corroborating this finding, we observed that genes associated with a consensus tuft cell signature32 were increased in whole jejunal tissue of IL-25-treated ΔILC2 or global KO mice when compared to WT mice (Figure 3d, Supplementary Table 3). Additionally, we observed that tuft cell-associated genes were already elevated in untreated ΔILC2 or KO mice compared to WT mice (Figure 3d), and were further augmented after IL-25 treatment. Indeed, tuft cells were increased 3-fold in untreated ΔILC2 or KO mice compared to WT mice (Figure 3e). A similar increase in goblet cells and associated transcripts was also evident in ΔILC2. conditional or KO mice (Supplementary Figure 3b–c, Supplementary Table 3). Collectively, these data suggest that small intestinal epithelial secretory lineages influenced by ILC2-derived IL-13 are enhanced in ILC2- or globally CISH-deficient mice.

Figure 3: Loss of CISH in ILC2s leads to an increase in intestinal tuft cells.

a. Representative images of small intestine from indicated strains of mice sacrificed on day 4 following 3 daily doses of i.p. IL-25 treatment. EpCAM (white), DCLK1 (green), IL5RFP+ ILC2s (red), DAPI (blue). Scale bars represent 200 μm.

b. Quantification of tuft cell numbers per villus as shown by immunofluorescence in (a). ***p<0.001 for one-way ANOVA with Dunnett testing for multiple comparisons. n=3–4 mice/group.

c. Flow cytometric quantification of tuft cells (DCLK1+, EpCAM+, CD44−, CD45−, live cells) in epithelial fraction of jejunum of IL-25-treated mice. *p<0.05 for one-way ANOVA with Dunnett testing for multiple comparisons. n=4 mice/group.

d. Heatmap of tuft cell consensus signature in untreated or IL-25-treated mice of indicated genotypes. Each block represents row-normalized mean expression of 3 mice/group.

e. Flow cytometric quantification of tuft cells (DCLK1+, EpCAM+, CD44−, CD45−, live cells) in epithelial fraction of jejunum of untreated mice by flow cytometry. *p<0.05 for one-way ANOVA with Dunnett testing for multiple comparisons. n=4 mice/group. Representative of 3 similar experiments.

Deficiency of CISH in ILC2s leads to increased ILC2 activity during homeostatic conditions

Having found direct evidence of increased ILC2 activation following perturbation and indirect evidence of increased ILC2 activation at rest (as indicated by the augmented numbers of tuft cells) in the absence of CISH, we examined ILC2s under basal conditions for evidence of increased activity. We observed no differences in the frequency of ILC2s in the unperturbed state in any of the tissues examined (Supplementary Figure 4a). Additionally, neither conditional nor global CISH knockout mice had altered percentages of IL-13+ resident ILC2s (Supplementary Figure 4b), suggesting a similar degree of activation in CISH-deficient and - sufficient ILC2s across tissues in situ. Corroborating this, sorted lung ILC2s from conditional CISH knockout mice had unaltered mRNA expression of prototypical ILC2 effector genes, such as Il13, Il5, Csf2, and Areg (Supplementary Figure 4c). Despite these similarities in numbers and cytokine outputs, however, we found that CISH-deficient ILC2s were more proliferative (Supplementary Figure 4d). The numbers of other tissue immune cells that may be influenced by ILC2s, including alveolar macrophages, eosinophils, and CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, were unaltered in conditional or global CISH knockout mice (Supplementary Figure 4e).

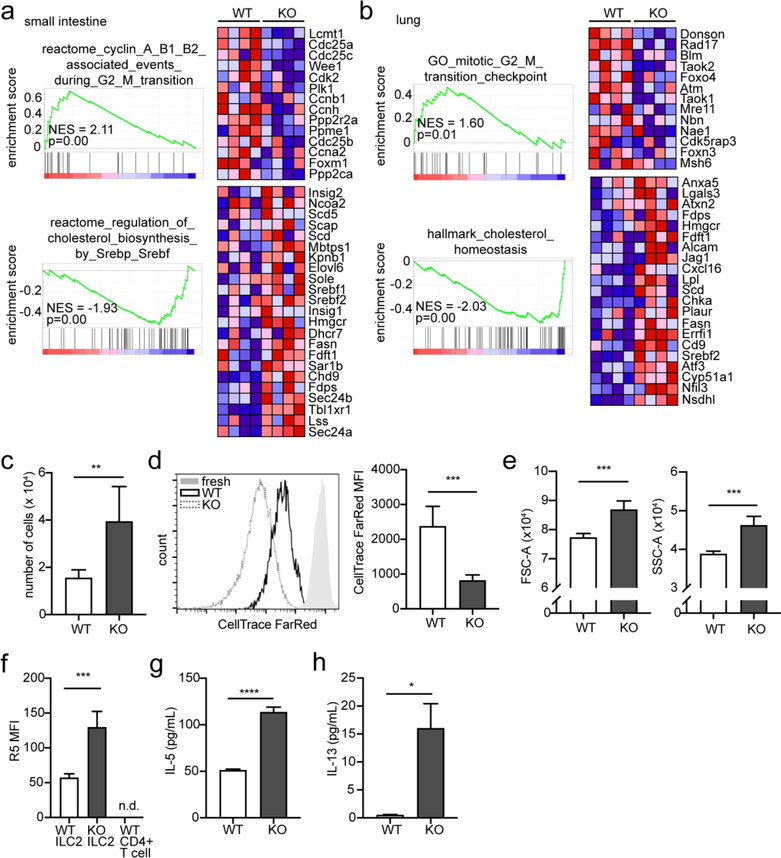

To address the difference between CISH-sufficient and -deficient ILC2s more granularly, we performed RNA sequencing of sorted WT or CISH-deficient ILC2s from small intestine and lung. Pathway analysis revealed shared perturbations among ILC2s between tissues, including an enrichment of cell-cycle control genes (e.g. Cdc25a, Cdc25c) in WT compared to KO cells (Figure 4a–b, Supplementary Table 4). Upregulated pathways in KO ILC2s included those associated with cholesterol biosynthesis, such as Hmgcr, which encodes the rate-limiting enzyme 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, and the transcriptional regulators Srebf1 and Srebf2 (Figure 4a–b). These changes are in line with the essential need for cholesterol production for cell cycle progression, including in lymphocytes33–37. To test the proliferative capacity of CISH-deficient ILC2s, we cultured purified ILC2s in vitro for 1 week with IL-2 and IL-7. Under these conditions, KO ILC2s proliferated more (Figure 4c–d), grew larger and more granular (Figure 4e), and produced more IL-5 (Figure 4f–g) and IL-13 (Figure 4h). Cumulatively, these data suggest that CISH intrinsically restricts proliferation and activation of ILC2s in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 4: CISH constrains proliferation and cytokine production in ILC2s.

a. Gene set enrichment analysis of small intestinal ILC2s from WT or CISH KO mice.

b. Gene set enrichment analysis of lung ILC2s from WT or CISH KO mice. For (a-b), each column represents sequenced cells from an individual mouse. Color blocks indicate row normalized expression. n = 4 mice/group.

c. Number of live ILC2s after 1 week of culture in 10 ng/mL IL-2 and IL-7. **p<0.01 by unpaired t-test. for (c-f), n = 5 wells/group with each well derived from a single mouse.

d. Histogram (left) and graphical quantitation (right) of CellTrace Far Red dye dilution in cultured ILC2s. “fresh” indicates cells immediately after staining, without subsequent culture. ***p<0.001 by unpaired t-test.

e. Forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) of cultured ILC2s after 1 week of culture. ***p<0.001 by unpaired t-test.

f. R5 MFI in cultured ILC2s. ***p<0.001 by unpaired t-test.

g. IL-5 from culture supernatant of cells cultured for 4d in IL-2 and IL-7. ****p<0.0001 by unpaired t-test. n =4 wells/group, derived from a split pooled collection of ILC2s from 8 mice/genotype.

h. IL-13 from culture supernatant of cells cultured for 4d. *p<0.05 by unpaired t-test. n=4 wells/group.

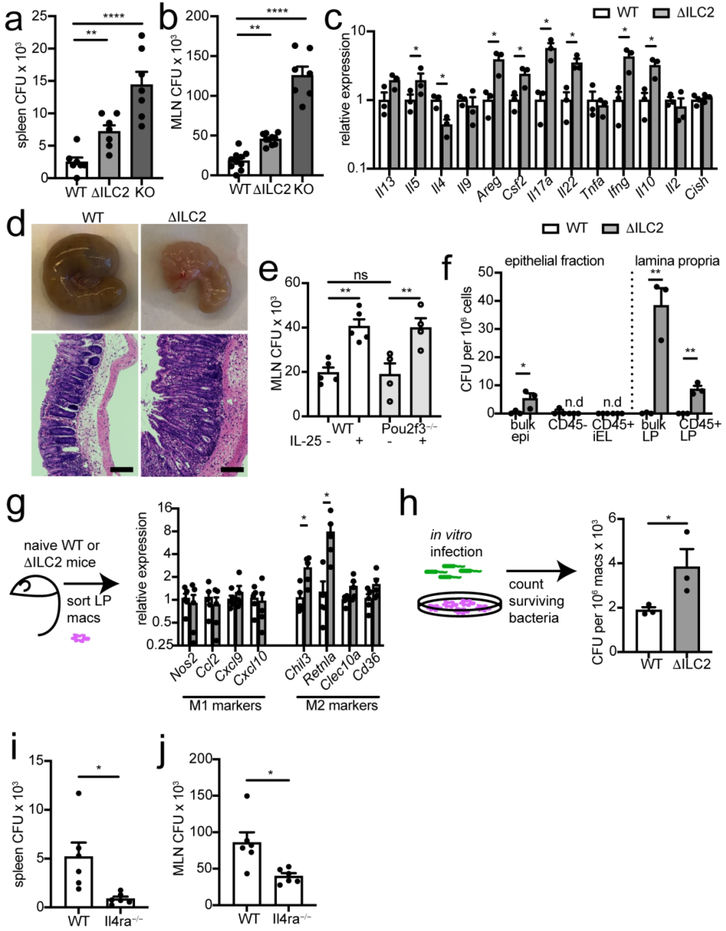

Loss of CISH in ILC2s leads to dysregulated immune responses to diverse pathogens

To optimize overall fitness, the canonical effector outputs of the immune system exist in careful balance2. Persistent perturbation of one output—in this case, a propensity towards type 2 activation—is likely to impact the function of the others38. To examine the effects of augmented ILC2 activity induced by CISH deficiency, we challenged WT, ΔILC2 conditional, or KO mice with oral Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium (S. typhimurium) infection, a model of lethal foodborne illness that induces secretion if IFN-γ, IL-22, and IL-17, among other cytokines, to control early infection39. Three days after infection, KO mice had a significantly increased bacterial burden in spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) compared to WT mice, whereas ΔILC2 mice exhibited bacterial burdens that were intermediate between WT and KO mice (Figure 5a–b). No significant differences were observed in major immune cell types—such as monocytes, CD8+ T cells, NK cells, CD4+ T cells, granulocytes, or ILC2s—within the lamina propria (Supplementary Figure 5a), MLN, or spleen (not shown). However, when we cultured bulk MLN cells from Salmonella-infected WT or ΔILC2 mice ex vivo, we found that cells from ΔILC2 mice expressed higher levels of transcripts for a diverse array of cytokine outputs (Figure 5c). These outputs were not limited to any single canonical class, suggesting global dysregulation of cytokine production. Because Cish transcripts were not decreased among bulk MLN cells in ΔILC2 mice compared to WT, observed changes in cytokine production were unlikely to be explained by off-target deletion of CISH in non-ILC2s or by enrichment of ILC2s in the MLN cultures (Figure 5c). When we further examined ΔILC2 or WT mice, we found that the ceca of ΔILC2 mice were grossly shrunken and contracted, with crypt lengthening and prominent lamina propria inflammatory infiltrates evident on histopathology (Figure 5d).

Figure 5: Loss of CISH in ILC2s impairs control of Salmonella infection.

a. Colony forming units (CFU) of S. typhimurium in spleens of indicated mice on day 3 of infection.

b. CFU from mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) of indicated mice at day 3. for (a-b), *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 for one-way ANOVA with Dunnett testing for multiple comparisons. n = 7–10 mice/group, pooled from 2 of 3 independent experiments.

c. Cytokine transcripts from dissociated MLNs of indicated genotype collected on day 3 of infection and cultured overnight. *p<0.05 by t-test. unannotated comparisons not significant. n = 3 mice/group.

d. Representative gross appearance and H&E-stained histologic appearance of ceca from indicated strains. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

e. CFU from MLN of WT (closed circles, white bars) or Pou2f3−/− (open circles, grey bars) mice treated with PBS or IL-25 to activate ILC2s. **p<0.01 by t-test. n = 4–5 mice/group.

f. CFU from epithelial-enriched fraction (bulk epi) or sorted CD45− (predominantly epithelial cells) or CD45+ (intraepithelial leukocytes, “iEL”) populations from the epithelial-enriched fraction (left of dotted line); or from the bulk lamina propria-enriched fraction or FACS-sorted CD45+ lamina propria (LP) cells (right of dotted line) of WT or ΔILC2 mice. n.d. = not detected. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 by t-test. n = 3 mice/group.

g. mRNA expression of M1 and M2 markers in FACS-sorted lamina propria macrophages from uninfected (naïve) WT (clear bars) or ΔILC2 (grey bars) mice. *p<0.05. unannotated comparisons not significant. n = 4 mice/group.

h. FACS-sorted lamina propria macrophages from uninfected (naïve) WT (clear bars) or ΔILC2 (grey bars) were infected in vitro with S. typhimurium, cleared of extracellular bacteria, and lysed to quantify surviving/intracellular bacterial CFUs. *p<0.05 by t-test. n = 3 mice/group.

i. CFU of S. typhimurium in spleens of indicated genotypes of mice on day 3 of infection.

j. CFU from MLN of indicated mice at day 3. for (i-j), *p<0.05 by t-test. n = 6 mice/group.

ILC2s may impact the dissemination of and immune response to Salmonella by altering the polarization, differentiation, or behavior of other cell types in the intestine, such as hematopoietic or epithelial cells, including tuft cells. However, we observed no differences in Salmonella burden in the MLN of tuft cell-deficient Pou2f3−/− mice compared to WT mice (Figure 5e). Because Pou2f3−/− mice have reduced tonic intestinal ILC2 activation as a consequence of the loss of tuft cells, we dissociated the role of tuft cells from that of ILC2s by treating Pou2f3−/− or WT mice with IL-25 to activate intestinal ILC2s and mimic the ILC2 hyperactivation observed in ΔILC2 mice. This treatment recapitulated the increased MLN bacterial burden imparted by CISH deletion in ILC2s, but as expected, was not dependent on the presence of tuft cells (Figure 5e). When we quantified intracellular bacterial burdens from fractionated intestinal cells of Salmonella-infected mice, we found that the majority of live, intracellular bacteria were associated with the lamina propria (LP) fraction—specifically from CD45+ cells in the LP—rather than from the epithelial fraction (Figure 5f). Together, these data suggested that the heightened bacterial burder in ΔILC2 mice was likely attributable to alterations in CD45+ lamina propria populations rather than to the direct infection of epithelial populations.

S. typhimurium is a facultative intracellular organism that can disseminate or establish persistent infection by infecting macrophages and dendritic cells40. ILC2s can promote the alternative activation of macrophages41, 42: a state in which those macrophages are impaired in their ability to kill intracellular bacteria, thereby increasing the risk of bacterial dissemination and/or persistence40, 43. Indeed, sorted LP macrophages from uninfected (naïve) ΔILC2 mice showed significantly increased expression of Chil3 and Retnla and a trend towards increased expression of Clec10a and CD36, genes associated with “alternative” or “M2” polarization, when compared to macrophages from WT mice (Figure 5g), while expression of “M1” markers such as Nos2, Ccl2, Cxcl9 and Cxcl10 did not differ (Figure 5g). Consistent with the previously described impairment in Salmonella killing by M2-polarized macrophages, LP macrophages derived from naive ΔILC2 mice also retained more live, intracellular bacteria after in vitro infection than did those from WT mice (Figure 5h), indicating an intrinsic defect in LP macrophages in ΔILC2 mice. M2 macrophage polarization by ILC2s is promoted through the secretion of IL-13, which acts through a heterodimeric receptor made up of IL4Rα and IL13Rα144. Therefore, we hypothesized that mice lacking IL-13 signaling through IL4Rα would have decreased M2 polarization among resting LP macrophages, and be better suited to kill and contain Salmonella at the mucosal barrier. Indeed, Salmonella-infected Il4ra−/− mice had reduced bacterial burden in the MLN and spleen (Figure 5i–j). Cumulatively, these data are consistent with a model in which CISH constrains ILC2 activity in the intestine, reduces tonic type 2 tone at this critical barrier, and modulates the resistence to potential mucosal pathogenic challenges.

To examine further the role of CISH in modulating ILC2 activity in diverse inflammatory settings, we challenged WT or Cish-deficient mice using a model of severe influenza pneumonia. ΔILC2 and KO mice exhibited improved survival after infection when compared to WT mice (Supplementary Figure 6a). Clinical examination of ΔILC2 and WT mice after infection revealed that ΔILC2 mice lost less body weight, exhibited less hypothermia, and had less severe oxygen desaturation during the peak of infection (Supplementary Figure 6b–d). As expected, ΔILC2 mice showed evidence of increased ILC2 activity as reflected by IL-13 expression by lung ILC2s and by IL-5 expression in whole lung tissue at the peak of infection (day 7), as well as by ILC2 expansion during the resolution phase (day 14), as compared to WT mice (Supplementary Figure 6e–i). This data is broadly consistent with prior data suggesting that IL-33-activated ILC2s may promote tissue repair45 and blunt influenza-induced immunopathology.

Discussion:

Here, we report that CISH is highly and constitutively expressed in tissue ILC2s and constrains their proliferation, activation and cytokine production. Rather than accompanying activation, CISH expression in ILC2s appears associated with maturation in tissues, as it is increased during development from lymphoid progenitors in bone marrow46 and further augmented in peripheral tissue compared to the bone marrow, and coincident with the initiation of effector outputs such as IL-13 and IL-5. Notably, CISH does not prevent these cells from maintaining their poised state. Deficiency of CISH in ILC2s leads to augmented numbers of intestinal tuft cells and fosters heightened epithelial immune tone that facilitates immunity during challenge with intestinal helminths. The increased type 2 immune tone conferred by deficiency of CISH in ILC2s has tradeoffs, however, impacting both antimicrobial resistance and disease tolerance to pathogen challenges that require dominant type 1 or type 17 outputs.

All of the mice used in these experiments were colonized with Tritrichomonas muris (Tm), an anaerobic, cecal-dwelling protist symbiont that colonizes many mouse SPF research colonies47. Tm activates the tuft cell – ILC2 circuit through succinate, a metabolic end-product which binds the G protein-coupled receptor, Sucnr1, on tuft cells, causing them to release IL-25 and activate lamina propria ILC2s, which constituitively express the IL-25 receptor, IL17RB30, 48. In this context, tuft and goblet cells were increased in CISH-deficient as compared to WT mice, revealing a role for CISH in restricting IL-25-dependent ILC2 activation. We further confirmed enhanced activation of this pathway by administration of exogenous IL-25 in vivo. Whereas basal survival cytokines like IL-2 and IL-7 are known to activate STAT5 and are therefore anticipated to be enhanced by the loss of feedback inhibition from CISH, IL-25 itself might also activate STAT549 and be similarly subject to CISH-mediated inhibition. Such modulation of IL-25 signaling in the setting of high constitutive expression of IL17RB on intestinal as compared to other tissue ILC2s20 would be consistent with the prominent effects of CISH deficiency seen in the small intestine in situ. As such, CISH may play a particularly important role in IL17RB-expressing ILC2s—which include not only those in small intestine, but potentially bone marrow and inflammatory ILC2s that are driven into the blood in response to tissue perturbation20, 26, 31. Of note, observed changes in ILC2 function in the absence of CISH are unlikely to be entirely dependent on Tm-induced IL-25 secretion, since CISH-deficient lung ILC2s cultured in vitro had augmented proliferation and cytokine production in the absence of such stimulation.

In addition to the role we describe for CISH in ILC2s, our data suggests a role for CISH in controlling other diverse cell types, consistent with prior reports14, 15, 17, 18. Specifically, ILC2-intrinsic loss of CISH (ΔILC2) was sufficient to augment ILC2 cytokine production and increase the number of intestinal tuft cells, but neither conditional deficiency of CISH in ILC2s or T cells could recapitulate the early pulmonary hypereosinophilia or degree of reduced worm burden seen in N.b.-infected KO mice. Prior reports have identified complementary roles for tissue resident and circulating immune cells in recruitment and activation of pulmonary eosinophilia, as well as in epithelial remodeling50, and CISH activity in T cells and ILC2s could coordinately control these roles. Additionally, CISH is known to restrict eosinophil activity, both by modulating production of eosinophil chemoattractants by stromal cells51 and through actions in eosinophils themselves52. Thus, CISH likely functions broadly across diverse cell types to limit coordinated type 2 immune responses during N.b. infection.

Many existing data have demonstrated that CISH acts across cell types including NK cells, T cells, dendritic cells, and others14, 15, 17, 18 to broadly suppress inflammatory outputs. However, a remaining unresolved issue is why animals that lack CISH globally across all of these cell types demonstrate a type 2 bias18. Humans with single nucleotide polymorphisms conferring reduced function of CISH show increased susceptibility to hepatitis B virus (HBV), bacteremia, tuberculosis (TB), and malaria53–55—observations consistent with our finding that CISH-deficient mice have increased susceptibility to Salmonella infection—but to our knowledge have not been reported to have allergic predilections. One proposed hypothesis for suppressed immunity in humans with CISH polymorphisms is over-stimulation of regulatory T cells, though this hypothesis has not been completely explored. Our data showing alterations in model bacterial and viral infections in both mice that are globally deficient in CISH and ΔILC2 mice suggests that augmented tissue tone established by resident ILC2s contributes to impaired type 1 and type 17 immunity, though this also has not been explored in humans. Additionally, the different microorganisms to which humans versus laboratory rodents under SPF conditions are exposed (such as Tritrichomonas muris) might substantially impact how CISH shapes global immune tone. Towards that end, an examination of CISH polypmorphisms among humans who live in regions where TB, malaria, and HBV are not endemic would also be informative.

In sum, we demonstrate that CISH is highly and constitutively expressed in mature tissue ILC2s, where it restrains the activity of these potent effector cells during homeostasis and during immune challenge. The alterations imposed by CISH deficiency in ILC2s are particularly evident in the small intestine in laboratory mice, where loss of CISH in ILC2 shifts the epithelial composition and augments defense against intestinal helminths. However, augmented type 2 immunity comes with tradeoffs, as loss of CISH in ILC2 affects immunity and tolerance to diverse pathogen challenges.

Methods:

Mice:

Arg1YFP 56, IL5RFP-Cre (“R5”)23, IL13Sm13 (“S13”)57, Il4ra−/−27, Pou2f3−/−30, and Il25−/−/Crlf2−/−/Il1rl1−/− (“TKO”)20 mice on a C57BL/6J background have been described. Cishtm1a(KOMP)Wtsi mice were obtained from the knockout mouse project produced by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute58. These were crossed to either a CMV-Cre (Jax 006054) to knockout CISH in all tissues (KO), or Flippase (Jax 009086) to create a conditional knockout (“CISHfl/fl”). After Cre and Flippase were bred out of the lines, subsequent crossing to R5 and CD4-Cre59 generated conditional knockouts (“ΔILC2” and “ΔCD4”) in IL-5-expressing cells including ILC2s, or in T cells, respectively. As in Figure 2a, all mice used to compare WT with ΔILC2 or KO were heterozygous for the IL5RFP-Cre allele to allow for identification of ILC2s and control for the loss of IL-5 expression from the knockin/knockout allele. Concurrent homozygous expression of the Arg1YFP allele (which is expressed by all lung ILC2s but few intestinal ILC2s) aided in identification of ILC2s, while heterozygous expression of the IL13Sm13 allele allowed for quantification of IL-13 expression. WT, CISHfl/fl and KO mice used for CD4-Cre-driven conditional deletion were all on Arg1YFP/YFP x IL13Sm13/Sm13 dual reporter background. Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in individually ventilated cages with autoclaved bedding on 12 hr light/day cycles and ad libitum access to irradiated food (PicoLab Mouse Diet 20, 5058M) and autoclaved water. All animals were manipulated using standard procedures including filtered air exchange stations, chlorine-based disinfection of gloves and work surfaces within manipulations with animals; personnel protection equipment (PPE) (disposable gowns, gloves, head caps, and shoe covers) is required to enter the facility. Experiments were performed on age- and sex-matched male and female mice between 6–12 weeks of age.

Mouse infections and treatments:

Infectious third-stage Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (N.b.) larvae (L3) were maintained as described57. Mice were infected subcutaneously with 500 N.b. L3 and sacrificed on day 5 or 11 of infection to collect tissues for staining or to count intestinal worm burden, as described57. To assess lung injury attributable to migratory worms, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed by intratracheal instillation and recovery of 1.5 mL of saline at day 3 of infection. IL-25-treated mice were injected intraperitoneally with 200 ng of carrier-free recombinant mouse IL-25 (BioLegend) on days 0, 1, and 2, and sacrificed on day 3 for analysis. For Salmonella infection followed by quantification of CFU from fractionated small intestinal cells, mice were fasted for 4 hours, pretreated with streptomycin by oral gavage 24h prior to inoculation with 107 CFU of Salmonella typhimurium L1344 by oral gavage, and then sacrified on day 2. In comparison to the standard infection model, this dose and timing was chosen to maximize both cell viability during the sort, and bacterial recovery. For all other Salmonella infections, mice were fasted for 4 hours, pretreated with streptomycin by oral gavage 24h prior to inoculation with 106 CFU of Salmonella typhimurium L1344 by oral gavage, and then sacrified on day 3. Titered PR8 influenza was generously provided by Dr. Jeff Gotts at UCSF. Mice were infected intranasally under isofluorane anesthesia with 800 focus forming units (FFU) of influenza virus. Body weight, rectal temperature, and oxygen saturation were measured using the MouseOx oximeter and software (Starr Life Sciences) at the indicated timepoints.

Cell isolation & flow cytometry:

After removal of Peyer’s patches, single cell suspensions from small intestine were prepared by serial washing in neutral buffer containing EDTA and DTT to remove epithelial cells, followed by digestion with 0.1 Wunsch/mL LiberaseTM (Roche) and 30 μg/mL DNAse I (Roche) to isolate lamina propria cells. Single cell suspensions from the skin were made by incubating equal-sized patches of minced, shaved skin from the animals’s back in 1.25 mg/mL LiberaseTL (Roche) and 100 μg/mL DNAse I. Lung single cell suspensions were obtained by tissue digestion with 50 μg/mL LiberaseTM and 25 μg/mL DNAse I. All suspensions were depleted of red blood cells using PharmLyse (BD) and passed through a 40 μM strainer prior to staining. ILC2s were gated as lin−, Thy1.2+, Arg1YFP+, R5+. A representative gating strategy for ILC2s is shown in Supplementary Figure 2a. Tuft cells were defined as DCLK1+, CD44−, EpCAM+, CD45−. Lineage cocktail and other antibodies used for flow cytometry are listed in Supplementary Table 1. After antibody staining, flow cytometry was performed on a LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences) using BD FACSDiva software and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). Dead cells were excluded from analysis based on staining with LIVE/DEAD Viability (Thermo) or 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

For CFU from fractionated intestinal cells as in Figure 5f, the cells isolated during the EDTA/DTT wash and the cells isolated after the Liberase/DNAse digestion (as described in the preceding paragraph) were separately stained, cleared of extracellular bacteria by treatment with ampicillin, and then sorted on a MoFlo Cell Sorter (Beckman Coulter) according to CD45 expression. Lamina propria macrophages (used for expression analysis or in vitro infection) were defined as CD45+, CD64+, CD11b+.

Cell culture:

ILC2s were isolated from lung single cell suspensions on a MoFlo Cell Sorter (Beckman Coulter). For in vitro stimulation in Figure 1b, lung ILC2s were gated as CD45+, lineage (“lin”; CD4, CD8, CD3, CD11b, CD11c, CD19, NK1.1, NKp46, Gr-1, F4/80, Ter119, DX5) negative, Thy1.2+, Sca1+, Arg1YFP+ and intestinal ILC2s were gated as CD45+, lin−, KLRG1+, Sca1+. For all other experiments, ILC2s were gated as lin−, Thy1.2+, Arg1YFP+, R5+. This sorting method routinely yields a purity of ≥88–98% (from a pre-sort frequency of ~0.5%). Purified cells were cultured at a density of 5×103 (for short-term culture) or 9×103 (for multi-day culture) per well in 200 μL of RPMI media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 10 mM HEPES (Sigma), pH 7.4, penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco), 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco), and IL-2 and IL-7 at 10 ng/mL each (R&D Systems). Stimulations were performed with addition of 10 ng/mL IL-25 (BioLegend), 10 ng/mL IL-33 (BioLegend), or 40 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Cayman) and 500 ng/mL ionomycin (Sigma) for 4h at 37°C. For MLN cultures, equal numbers of dissociated cells were restimulated in supplemented RPMI containing IL-2 at 10 ng/mL, PMA/ionomycin, and ampicillin overnight before lysis in RLT-plus buffer (Qiagen). For proliferation studies, cells were stained with 100 nM CellTrace Far Red dye (Thermo) for 10 minutes prior to cultures. Supernatants were collected after centrifugation for protein analysis, and cell pellets were either lysed in RLT-plus for later RNA isolation, or resuspended and stained for flow cytometric analysis. IL-5 and IL-13 protein were quantified in supernatants using Cytometric Bead Array Flex Sets, acquired with a LSR Fortessa, and analyzed using Flow Cytometric Analysis Program (FCAP) Array software (BD Biosciences).

For in vitro macrophage infections, 2.5 × 105 lamina propria macrophages (as described in “cell isolation & flow cytometry”) were separately isolated from 3 mice of each genotype and allowed to adhere to 24 well plates for 2h prior to inoculation with S. typhimurium at MOI = 100 in RPMI media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 10 mM HEPES (Sigma), pH 7.4, penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco), 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco). Extracellular bacteria were killed by addition of gentamicin 1 hour after infection, after which macrophages were cultured overnight, then lifted from TC plates, washed twice to remove any remaining extracellular bacteria, and plated for CFU quantification.

Histology & immunofluorescence:

The most proximal 2 cm of small intestine (SI) were discarded and the next 6 cm were cleared of luminal content, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 4h at 4°C followed by PBS wash. Tissues were cryoprotected overnight in 30% (w/v) sucrose before embedding in OCT media (Sakura). 8 μm frozen sections were prepared on a cryostat (Leica), stained with antibodies as listed in Supplemental Table 1, counterstained with DAPI, mounted, and analyzed on a Nikon A1R confocal microscope using NIS Elements (Nikon) and Fiji (ImageJ) software. For histologic sections of small intestine or cecum, SI samples (harvested and fixed as above) or whole PFA-fixed cecum were embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Alcian blue - Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAB) at the UCSF Histology and Biomarker Core, and imaged on a Nikon A1R microscope.

RNA expression analysis:

Comparative expression of Cish in multiple lymphoid subsets was investigated through the publicly available browser created and sourced by the Immunological Genome Project (ImmGen)19. Gene expression of Cish and related transcripts in ILC2s or comparator lymphocyte populations from various tissues of wild type mice was performed as described20, and previously made available at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession code GSE117568.

For RT-PCR, ILC2s or CD4+ T cells from lung (~10,000–20,000 cells per mouse) of 3 mice per group were sorted individually into RLT Plus lysis buffer (Qiagen) and stored at −80 °C, then processed using the RNeasy Micro Plus kit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was reverse transcribed using the SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (ThermoFisher) and amplified using Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (ThermoFisher) using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 2. Expression was quantified using the delta-delta Ct method normalized to housekeeping genes (Rpl13a and Hprt).

For RNA sequencing experiments, lung and SI ILC2s were purified from tissue as described above and collected directly into lysis buffer provided in the DynaBead Direct mRNA Micro Kit (ThermoFisher). Poly-adenylated mRNA was purified according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and sequenced by Tag-Seq method on HiSeq 4000 (Illumina) at the UC Davis Genomics Core. For whole tissue RNA sequencing, 1 cm of intact small intestine, cleared of mesentery and luminal content, was homogenized in RNAzol (Sigma), isolated by 4-bromoanisole phase separation according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and then cleaned up using an RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) before submission for Tag-Seq at the UC Davis Genomics Core. Reads were aligned to the mouse genome and quantified using the STAR aligner software version 2.7.2b. Differential expression analysis was performed in the R computing environment version 3.6.1 using the software DESeq2 version 1.26. Significance thresholds used were FDR<0.05 and log fold change >1 or < −1. Pathway analysis was performed using the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis software (Broad Institute)60, 61. Sequencing datasets will be made publically available through the NCBI Gene Expression Ombibus (GEO).

Statistical analysis:

All graphical representations and statistical analyses were performed with Graphpad Prism 8 or 9 using the appropriate statistical tests with posthoc testing as specified in figure legends. Figures display means +/− SEM as indicated.

Study Approval:

All experimental procedures on mice were approved by the UCSF Animal Care and Use Committee.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank members of the Locksley lab, Jesse Nussbaum, Erin Gordon, and Jelena Bezbradica for discussion and critical feedback, Zhien Wang for assistance with flow cytometric sorting, Beatrice Herrmann and Igor Brodsky for advice on Salmonella experiments, and Jeff Gotts for providing PR8 influenza. We are grateful for financial support from the NIH (AI026918 to R.M.L., F32HL140868 and T32HL007185 for M.E.K, and T32AI007334 for N.M.M.), HHMI, the A.P. Giannini Foundation, the SABRE Center at UCSF, and the UCSF Diabetes Research Center. C.S. is supported by the Peter Hans Hofschneider Professorship for Molecular Medicine.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement:

The authors declare no competing interests.

References:

- 1.Klose CS, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells as regulators of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis. Nat Immunol 2016; 17(7): 765–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotas ME, Locksley RM. Why Innate Lymphoid Cells? Immunity 2018; 48(6): 1081–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sivori S, Vacca P, Del Zotto G, Munari E, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Human NK cells: surface receptors, inhibitory checkpoints, and translational applications. Cell Mol Immunol 2019; 16(5): 430–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerwenka A, Lanier LL. Natural killer cell memory in infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 2016; 16(2): 112–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duerr CU, McCarthy CD, Mindt BC, Rubio M, Meli AP, Pothlichet J et al. Type I interferon restricts type 2 immunopathology through the regulation of group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol 2016; 17(1): 65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moro K, Kabata H, Tanabe M, Koga S, Takeno N, Mochizuki M et al. Interferon and IL-27 antagonize the function of group 2 innate lymphoid cells and type 2 innate immune responses. Nat Immunol 2016; 17(1): 76–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagashima H, Mahlakoiv T, Shih HY, Davis FP, Meylan F, Huang Y et al. Neuropeptide CGRP Limits Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell Responses and Constrains Type 2 Inflammation. Immunity 2019; 51(4): 682–695 e686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moriyama S, Brestoff JR, Flamar AL, Moeller JB, Klose CSN, Rankin LC et al. Beta2-adrenergic receptor-mediated negative regulation of group 2 innate lymphoid cell responses. Science 2018; 359(6379): 1056–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg AV, Ahmed M, Vallejo AN, Ma A, Gaffen SL. The deubiquitinase A20 mediates feedback inhibition of interleukin-17 receptor signaling. Sci Signal 2013; 6(278): ra44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trengove MC, Ward AC. SOCS proteins in development and disease. Am J Clin Exp Immunol 2013; 2(1): 1–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshimura A, Ohkubo T, Kiguchi T, Jenkins NA, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG et al. A Novel Cytokine-Inducible Gene Cis Encodes an Sh2-Containing Protein That Binds to Tyrosine-Phosphorylated Interleukin-3 and Erythropoietin Receptors. Embo Journal 1995; 14(12): 2816–2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsumoto A, Seki Y, Kubo M, Ohtsuka S, Suzuki A, Hayashi I et al. Suppression of STAT5 functions in liver, mammary glands, and T cells in cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein 1 transgenic mice. Mol Cell Biol 1999; 19(9): 6396–6407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumoto A, Masuhara M, Mitsui K, Yokouchi M, Ohtsubo M, Misawa H et al. CIS, a cytokine inducible SH2 protein, is a target of the JAK-STAT5 pathway and modulates STAT5 activation. Blood 1997; 89(9): 3148–3154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer DC, Guittard GC, Franco Z, Crompton JG, Eil RL, Patel SJ et al. Cish actively silences TCR signaling in CD8+ T cells to maintain tumor tolerance. J Exp Med 2015; 212(12): 2095–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delconte RB, Kolesnik TB, Dagley LF, Rautela J, Shi W, Putz EM et al. CIS is a potent checkpoint in NK cell-mediated tumor immunity. Nat Immunol 2016; 17(7): 816–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu H, Blum RH, Bernareggi D, Ask EH, Wu Z, Hoel HJ et al. Metabolic Reprograming via Deletion of CISH in Human iPSC-Derived NK Cells Promotes In Vivo Persistence and Enhances Anti-tumor Activity. Cell Stem Cell 2020; 27(2): 224–237 e226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miah MA, Yoon CH, Kim J, Jang J, Seong YR, Bae YS. CISH is induced during DC development and regulates DC-mediated CTL activation. Eur J Immunol 2012; 42(1): 58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang XO, Zhang H, Kim BS, Niu X, Peng J, Chen Y et al. The signaling suppressor CIS controls proallergic T cell development and allergic airway inflammation. Nat Immunol 2013; 14(7): 732–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heng TS, Painter MW, Immunological Genome Project C. The Immunological Genome Project: networks of gene expression in immune cells. Nat Immunol 2008; 9(10): 1091–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Van Dyken SJ, Schneider C, Lee J, Nussbaum JC, Liang HE et al. Tissue signals imprint ILC2 identity with anticipatory function. Nat Immunol 2018; 19(10): 1093–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price AE, Liang HE, Sullivan BM, Reinhardt RL, Eisley CJ, Erle DJ et al. Systemically dispersed innate IL-13-expressing cells in type 2 immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107(25): 11489–11494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molofsky AB, Nussbaum JC, Liang HE, Van Dyken SJ, Cheng LE, Mohapatra A et al. Innate lymphoid type 2 cells sustain visceral adipose tissue eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages. J Exp Med 2013; 210(3): 535–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nussbaum JC, Van Dyken SJ, von Moltke J, Cheng LE, Mohapatra A, Molofsky AB et al. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. Nature 2013; 502(7470): 245–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halim TY, Krauss RH, Sun AC, Takei F. Lung natural helper cells are a critical source of Th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. Immunity 2012; 36(3): 451–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Schneider C, Liao C, Lee J, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Tissue-specific pathways extrude activated ILC2s to disseminate type 2 immunity. J Exp Med 2020; 217(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Y, Guo L, Qiu J, Chen X, Hu-Li J, Siebenlist U et al. IL-25-responsive, lineage-negative KLRG1(hi) cells are multipotential ‘inflammatory’ type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol 2015; 16(2): 161–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Moltke J, Ji M, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Tuft-cell-derived IL-25 regulates an intestinal ILC2-epithelial response circuit. Nature 2016; 529(7585): 221–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerbe F, Sidot E, Smyth DJ, Ohmoto M, Matsumoto I, Dardalhon V et al. Intestinal epithelial tuft cells initiate type 2 mucosal immunity to helminth parasites. Nature 2016; 529(7585): 226–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howitt MR, Lavoie S, Michaud M, Blum AM, Tran SV, Weinstock JV et al. Tuft cells, taste-chemosensory cells, orchestrate parasite type 2 immunity in the gut. Science 2016; 351(6279): 1329–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider C, O’Leary CE, von Moltke J, Liang HE, Ang QY, Turnbaugh PJ et al. A Metabolite-Triggered Tuft Cell-ILC2 Circuit Drives Small Intestinal Remodeling. Cell 2018; 174(2): 271–284 e214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang Y, Mao K, Chen X, Sun MA, Kawabe T, Li W et al. S1P-dependent interorgan trafficking of group 2 innate lymphoid cells supports host defense. Science 2018; 359(6371): 114–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haber AL, Biton M, Rogel N, Herbst RH, Shekhar K, Smillie C et al. A single-cell survey of the small intestinal epithelium. Nature 2017; 551(7680): 333–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen HW, Heiniger HJ, Kandutsch AA. Relationship between sterol synthesis and DNA synthesis in phytohemagglutinin-stimulated mouse lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1975; 72(5): 1950–1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russell DW. Cholesterol biosynthesis and metabolism. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1992; 6(2): 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bietz A, Zhu H, Xue M, Xu C. Cholesterol Metabolism in T Cells. Front Immunol 2017; 8: 1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacIver NJ, Michalek RD, Rathmell JC. Metabolic regulation of T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol 2013; 31: 259–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kidani Y, Elsaesser H, Hock MB, Vergnes L, Williams KJ, Argus JP et al. Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins are essential for the metabolic programming of effector T cells and adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol 2013; 14(5): 489–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Desai P, Janova H, White JP, Reynoso GV, Hickman HD, Baldridge MT et al. Enteric helminth coinfection enhances host susceptibility to neurotropic flaviviruses via a tuft cell-IL-4 receptor signaling axis. Cell 2021; 184(5): 1214–1231 e1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Broz P, Ohlson MB, Monack DM. Innate immune response to Salmonella typhimurium, a model enteric pathogen. Gut Microbes 2012; 3(2): 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eisele NA, Ruby T, Jacobson A, Manzanillo PS, Cox JS, Lam L et al. Salmonella require the fatty acid regulator PPARdelta for the establishment of a metabolic environment essential for long-term persistence. Cell Host Microbe 2013; 14(2): 171–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bouchery T, Kyle R, Camberis M, Shepherd A, Filbey K, Smith A et al. ILC2s and T cells cooperate to ensure maintenance of M2 macrophages for lung immunity against hookworms. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 6970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Besnard AG, Guabiraba R, Niedbala W, Palomo J, Reverchon F, Shaw TN et al. IL-33-mediated protection against experimental cerebral malaria is linked to induction of type 2 innate lymphoid cells, M2 macrophages and regulatory T cells. PLoS Pathog 2015; 11(2): e1004607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pham THM, Brewer SM, Thurston T, Massis LM, Honeycutt J, Lugo K et al. Salmonella-Driven Polarization of Granuloma Macrophages Antagonizes TNF-Mediated Pathogen Restriction during Persistent Infection. Cell Host Microbe 2020; 27(1): 54–67 e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity 2010; 32(5): 593–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Abt MC, Alenghat T, Ziegler CG, Doering TA et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat Immunol 2011; 12(11): 1045–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seillet C, Mielke LA, Amann-Zalcenstein DB, Su S, Gao J, Almeida FF et al. Deciphering the Innate Lymphoid Cell Transcriptional Program. Cell Rep 2016; 17(2): 436–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chudnovskiy A, Mortha A, Kana V, Kennard A, Ramirez JD, Rahman A et al. Host-Protozoan Interactions Protect from Mucosal Infections through Activation of the Inflammasome. Cell 2016; 167(2): 444–456 e414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nadjsombati MS, McGinty JW, Lyons-Cohen MR, Jaffe JB, DiPeso L, Schneider C et al. Detection of Succinate by Intestinal Tuft Cells Triggers a Type 2 Innate Immune Circuit. Immunity 2018; 49(1): 33–41 e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu L, Zepp JA, Qian W, Martin BN, Ouyang W, Yin W et al. A novel IL-25 signaling pathway through STAT5. J Immunol 2015; 194(9): 4528–4534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rahimi RA, Nepal K, Cetinbas M, Sadreyev RI, Luster AD. Distinct functions of tissue-resident and circulating memory Th2 cells in allergic airway disease. J Exp Med 2020; 217(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takeshima H, Horie M, Mikami Y, Makita K, Miyashita N, Matsuzaki H et al. CISH is a negative regulator of IL-13-induced CCL26 production in lung fibroblasts. Allergol Int 2019; 68(1): 101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burnham ME, Koziol-White CJ, Esnault S, Bates ME, Evans MD, Bertics PJ et al. Human airway eosinophils exhibit preferential reduction in STAT signaling capacity and increased CISH expression. J Immunol 2013; 191(6): 2900–2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khor CC, Vannberg FO, Chapman SJ, Guo H, Wong SH, Walley AJ et al. CISH and susceptibility to infectious diseases. N Engl J Med 2010; 362(22): 2092–2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tong HV, Toan NL, Song LH, Kremsner PG, Kun JFJ, Tp V. Association of CISH - 292A/T genetic variant with hepatitis B virus infection. Immunogenetics 2011; 64(4): 261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun L, Jin YQ, Shen C, Qi H, Chu P, Yin QQ et al. Genetic contribution of CISH promoter polymorphisms to susceptibility to tuberculosis in Chinese children. PLoS One 2014; 9(3): e92020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reese TA, Liang HE, Tager AM, Luster AD, Van Rooijen N, Voehringer D et al. Chitin induces accumulation in tissue of innate immune cells associated with allergy. Nature 2007; 447(7140): 92–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liang HE, Reinhardt RL, Bando JK, Sullivan BM, Ho IC, Locksley RM. Divergent expression patterns of IL-4 and IL-13 define unique functions in allergic immunity. Nat Immunol 2011; 13(1): 58–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skarnes WC, Rosen B, West AP, Koutsourakis M, Bushell W, Iyer V et al. A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function. Nature 2011; 474(7351): 337–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee PP, Fitzpatrick DR, Beard C, Jessup HK, Lehar S, Makar KW et al. A critical role for Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in T cell development, function, and survival. Immunity 2001; 15(5): 763–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Subramanian A, Kuehn H, Gould J, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. GSEA-P: a desktop application for Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. Bioinformatics 2007; 23(23): 3251–3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102(43): 15545–15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.