Abstract

The transcription factor ATF2 was previously shown to be an ATM substrate. Upon phosphorylation by ATM, ATF2 exhibits a transcription-independent function in the DNA damage response through localization to DNA repair foci and control of cell cycle arrest. To assess the physiological significance of this phosphorylation, we generated ATF2 mutant mice in which the ATM phosphoacceptor sites (S472/S480) were mutated (ATF2KI). ATF2KI mice are more sensitive to ionizing radiation (IR) than wild-type (ATF2 WT) mice: following IR, ATF2KI mice exhibited higher levels of apoptosis in the intestinal crypt cells and impaired hepatic steatosis. Molecular analysis identified impaired activation of the cell cycle regulatory protein p21Cip/Waf1 in cells and tissues of IR-treated ATF2KI mice, which was p53 independent. Analysis of tumor development in p53KO crossed with ATF2KI mice indicated a marked decrease in amount of time required for tumor development. Further, when subjected to two-stage skin carcinogenesis process, ATF2KI mice developed skin tumors faster and with higher incidence, which also progressed to the more malignant carcinomas, compared with the control mice. Using 3 mouse models, we establish the importance of ATF2 phosphorylation by ATM in the acute cellular response to DNA damage and maintenance of genomic stability.

Keywords: ATF2, tumorigenesis, p53, radiation, DNA damage

Introduction

The cellular response to DNA damage engages numerous signal transduction pathways that rapidly affect downstream processes, including transcription, DNA replication, and cell cycle status, to enable either DNA repair or cell death.1,2 Central to the DNA damage response are members of the phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase-like kinase (PIKK) family,3,4 which are activated in response to double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) promoted by genotoxic insult.5 Among the PIKK family members are ATM (ataxia-telangiectasia mutated), ATR (ataxia-telangiectasia and Rad-3-related), and DNA PK (DNA protein kinase catalytic subunit).2,6 ATM substrates functioning in the DNA damage response are the checkpoint signaling kinases Chk2 and Chk17,8; checkpoint mediators ATF2, BRCA1, 53BP1, and MDC19-12; the histone variant H2AX; and the diverse effectors that function in DNA repair, cell cycle, and cell death control, such as RAD9, RAD17, SMC1, FANCD2, and p53.13-19 Mutation or loss of ATM impairs DNA damage-induced p53 activation.20 Consistent with its key role in the DNA damage response, impaired activation of ATM results in higher sensitivity to ionizing radiation (IR), spontaneous lymphomagenesis, infertility, and neurologic abnormalities.2,21,22

DNA damage also activates the Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), which augments PIKK function. Impaired activation of JNK or its substrates, such as c-Jun, ATF2, or p53, affects cell cycle control that is integral to a cell's ability to initiate proper repair processes. Hence, concerted activity of ATM, JNK, and their substrates is a prerequisite for an intact cellular response to DNA damage and repair. Intriguingly, some JNK substrates are also ATM substrates, although the phosphoacceptor sites for the two kinases are distinct, and modification by either can confer a distinct functional outcome. Among the shared substrates are p53, c-Jun, and ATF2. p53 phosphorylation on Ser15 is ATM dependent and implicated in its transcriptional activities and stability.17,23 Similarly, JNK phosphorylation of p53 on Thr81 contributes to p53 stability and activity.24 In contrast, phosphorylation of ATF2 by JNK is required for its transcriptional activities, whereas phosphorylation by ATM results in localization of ATF2 to DNA repair foci, independent of its transcriptional function.10,25,26 Notably, c-Jun can be also found within DNA repair foci following IR.27

Our previous studies revealed that in addition to its transcriptional activity (reviewed in Lopez-Bergami et al., 201028), ATF2 also functions in the DNA damage response that requires phosphorylation by ATM on serines 490/498 of the human protein (corresponding to mouse residues 472/480).10,25 ATF2 phosphorylation by ATM is required for ATF2 to localize with the MRN complex proteins in DNA repair foci and to contribute to the intra-S-phase checkpoint. Furthermore, inhibition of ATF2 expression attenuates the degree of ATM activation after IR10 through ATF2's association with and control of the histone acetyltransferase.

Here we assessed the physiological significance of ATF2 phosphorylation by ATM using mice in which both the ATM phosphoacceptor sites on ATF2 (serines 472/480) were mutated to alanine (ATF2KI mice). We show that these mice were more sensitive to IR and, when crossed with p53 knockout (KO) mice, developed similar tumor types more rapidly than either ATF2KI or p53KO mice. Notably, the cell cycle regulatory protein p21 did not accumulate in IR-treated ATF2KI-derived cells and tissues, suggesting a mechanism underlying the impaired response to DNA damage. Lastly, induction of skin carcinogenesis in ATF2KI mice was faster and resulted in a higher number of low-grade skin tumors. Our data establish the role of ATF2 phosphorylation by ATM in acute cellular response to DNA damage and tumor susceptibility.

Results

Generation of ATF2KI mice

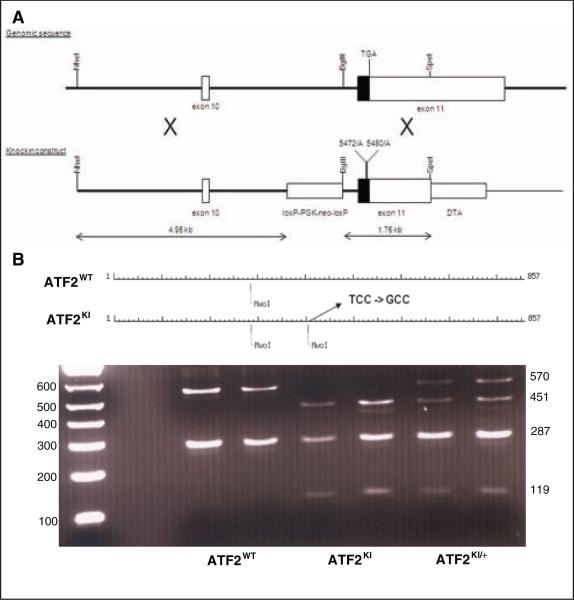

The vector used for gene targeting in mouse ES cells contained ATF2 sequences mutated on Ser472/480 (corresponding to human residues 490/498; Fig. 1A) and was based on a construct used previously to generate an ATF2 conditional mouse line.29 Proper homologous recombination in AMK6 ES cells (129S7 background) generated a knock-in allele of ATF2 bearing the Ser472/480 mutations. Founder mice were derived from blastocyst injection experiments and breeding of the chimeric mice. The resulting F1 generation mice that were heterozygous for the targeted ATF2 allele were crossed with Protamine-Cre transgenic mice30 to delete the floxed drug selection marker in the sperm cells of mice inheriting both the Cre transgene and the ATF2KI allele. The ATF2KI/+, Pr-Cre mice were bred to wild-type (WT) C57Bl/6 mice to generate the ATF2KI model, which was subsequently back-crossed with C57Bl/6 mice for 9 generations. This resulted in the recovery of the ATF2KI allele on an inbred C57Bl/6 background. A restriction fragment-based PCR reaction was established and utilized for rapid genotyping (Fig. 1B). ATF2KI mice were born exhibiting the expected Mendelian frequency and were indistinguishable from ATF2WT littermates.

Figure 1.

Generation of ATF2KI mice. (A) Scheme outlines strategy used to replace serines 472/480 with alanines on a genomic clone used for homologous recombination. Location of the loxP-PGK-neo-loxP cassette is indicated. DTA is a negative selection marker. (B) Restriction fragment-based genotyping of ATF2KI mice. Noted is one of the two MwoI sites lost upon S472A substitution. Representative ethidium bromide–stained gel depicts the different PCR garments obtained following MwoI digestion for each of the possible genotypes.

ATF2KI mice are more sensitive to IR

Given the role of ATF2 in the DNA damage response and the crosstalk between ATF2 and ATM signaling, we first assessed phenotypes seen in ATM mutant mice or mice carrying mutation in ATM substrates. Phenotypes common to these mice are an impaired DNA damage response, coupled with improper repair and higher IR sensitivity.20,21 Mice homozygous for loss of ATM often develop spontaneous lymphomagenesis at the age of 2 to 4 months.21,22 Unlike ATM mutant mice, ATF2KI mice did not develop spontaneous tumors (data not shown; see Fig. 5A). To assess abnormalities in the hematopoietic system, lymphocytes from thymus, spleen, bone marrow, and the peritoneal cavity were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), but no differences in B and T cell development or distribution of distinct lymphocyte subpopulations were seen between the ATF2WT and ATF2KI mice (data not shown).

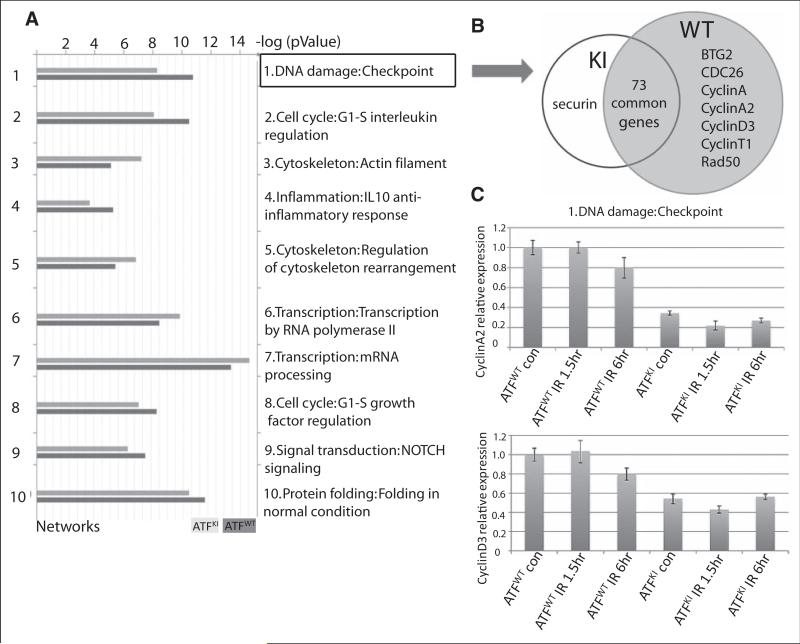

Figure 5.

GeneGo analysis identified DNA damage checkpoint networks that topped the list of changes between wild-type (ATF2WT) and ATF2KI groups. (A) ATF2WT and ATF2KI murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were subjected to 10Gy ionizing radiation (IR), and RNA samples were prepared 1 hour later to determine gene expression levels using the illumina array platform (see Materials and Methods for details). The array data were analyzed using the GeneGo enrichment software package. Shown are the top 10 clusters of gene networks that exhibit significant changes in gene expression between the ATF2KI and ATF2WT samples. (B) Genes that belong to DNA damage checkpoint are grouped in knock-in (ATF2KI) and ATF2WT. Uniquely expressed genes are listed in the circle. (C) qPCR analysis of cyclin A2 and cyclin D3 transcript levels performed on MEF from ATF2WT and ATF2KI mice following the indicated.

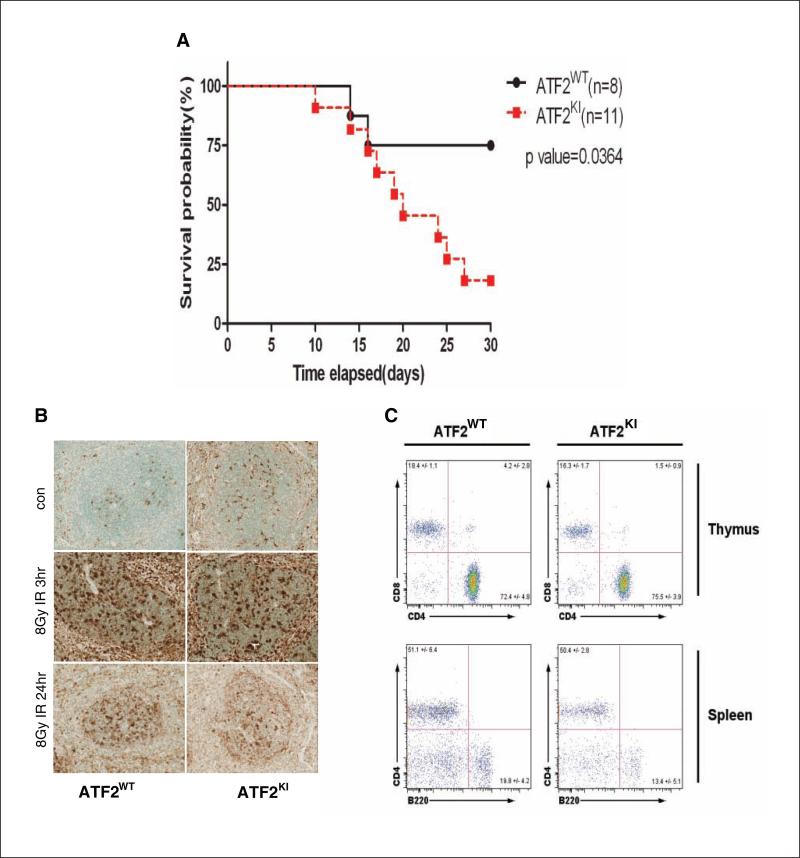

To determine whether ATF2KI mice are sensitive to IR, we exposed them to 8Gy of IR. While >70% of ATF2WT littermates (n = 8) survived beyond 30 days, over 75% of the ATF2KI animals (n = 11) died within 30 days, indicating that ATF2KI mice are more sensitive to IR than ATF2WT mice (Fig. 2A). A lethal dose in which 50% of mice died (LD50) following IR was calculated to be >30 days for the ATF2WT mice, compared with 20 days for the ATF2KI mice (Fig. 2A). Thus, ATF2 phosphorylation by ATM contributes to IR resistance.

Figure 2.

ATF2KI mice are more sensitive to ionizing radiation (IR). (A) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. Age-comparable adult wild-type (ATF2WT) and knock-in (KI) animals received 8Gy whole-body irradiation. Thirty days after irradiation, 75% of the ATF2KI group died, while 70% of the animals in the ATF2WT group survived the irradiation using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. (B) Terminal transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) analysis of spleen from ATF2WT and ATF2KI animals obtained 3 or 24 hours after 8Gy IR or corresponding controls. (C) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of thymus and spleen from ATF2WT and ATF2KI animals performed 48 hours after exposure to 5Gy IR. Shown are representative data (n = 4 for ATF2WT, n = 5 for ATF2KI).

Terminal transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) analysis of spleen tissues at 3 hours, 24 hours, and 6 days after IR (8Gy) showed increased cell death 3 hours after IR in both ATF2WT and ATF2KI mice (Fig. 2B and data not shown). Significantly, CD4 and CD8 double-positive thymocytes underwent apoptosis following IR (Fig. 2C). Although a significant loss of thymocytes was observed 48 hours after 5Gy IR, no difference was observed in the distribution of double-positive thymocytes (Fig. 2C). The two groups also showed no difference in apoptosis of lymphocytes from spleen, bone marrow, and the peritoneal cavity (data not shown).

Since IR targets hematopoietic stem cells and causes anemia in mice,31 we performed whole-blood analysis of hematocrit (HCT), hemoglobin, red blood cells, and white blood cells in ATF2WT and ATF2KI mice. In both groups, we observed immediate leucopenia 24 hours after IR and anemia 6 days after IR, yet no difference was observed between the two groups (data not shown).

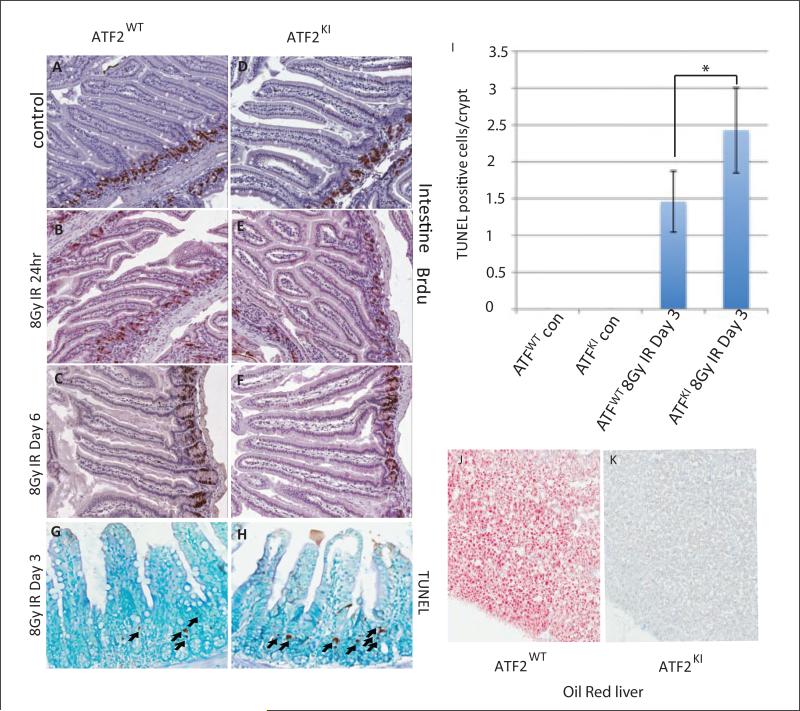

ATF2KI mice exhibit increased intestinal cell apoptosis and more severe liver damage after IR

Proliferating clonogenic crypt cells in the intestine are sensitive to IR, and apoptosis of these cells leads to depletion of villus cells, organ failure, and eventually cell death.32-35 BrdU staining performed on intestine sections from control and irradiated mice was collected at 24 hours and at 6 days after IR (8Gy). Analysis revealed a temporary reduction in the number of BrdU-positive crypt cells 24 hours after IR (Fig. 3A-B, D-E), which was restored 6 days after IR in both ATF2WT and ATF2KI mice (Fig. 3C,F). However, different from the response seen in control mice, we observed increased apoptosis in intestinal crypt cells of irradiated ATF2KI mice (Fig. 3G-I). Therefore, although the rate of proliferation of crypt cells was unchanged in ATF2KI mice, increased apoptosis seen in crypt cells likely resulted in depletion of this critical cell population and could account, in part, for the greater sensitivity of ATF2KI mice to IR. Previous studies showed that IR can also induce hepatic steatosis.36 Hepatic steatosis is a physiological response of liver to damage and often is reversible.37 Conditional knockout of ATF2 showed that ATF2 is essential for early liver development.29 We therefore evaluated pathology of liver from both ATF2WT and ATF2KI mice before and after IR. We found increased oil red staining in ATF2WT animal (2/3) 6 days after IR (Fig. 3J); however, all the ATF2KI livers (6/6) stained negative (Fig. 3K). With the data that ATF2KI mice suffer from more apoptosis in multiple organs, it seems that ATF2KI mice also suffer from more severe liver damage, and the damage is more severe than the reversible hepatic steatosis. These results suggest that ATM-dependent phosphorylation of ATF may be essential to maintain liver homeostasis under both normal and stressed conditions.

Figure 3.

ATF2KI mice exhibit increased intestinal cell apoptosis and more severe liver damage after ionizing radiation (IR). (A-F) BrdU staining of intestine of wild-type (ATF2WT) and ATF2KI animals was performed on nonirradiated (control a and b) and irradiated mice at 24 hours and 6 days after IR. Note decrease in BrdU-positive cells that reside in the crypt at the 24-hour time point, which restores at the day 6 time point. (G, H) Terminal transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) staining (right panels) reveals marked increase (P < 0.05) in apoptosis in the crypt cells of the intestine in the ATF2KI compared with the ATF2WT animals. (I) Summary of the increased apoptosis in the crypt cell. (J, K) Oil red staining of the liver showed that IR increases hepatic steatosis in ATF2WT, while ATF2KI liver stained negative for oil red.

Though ATF2KI mice showed greater sensitivity to IR, it seems that these mice suffered more severe damage in multiple organs (i.e., intestine, liver). Thus, the acute lethality could be attributed to the failure of multiple organs combined with anemia.

Attenuated expression of p21 following IR of in ATF2KI mice

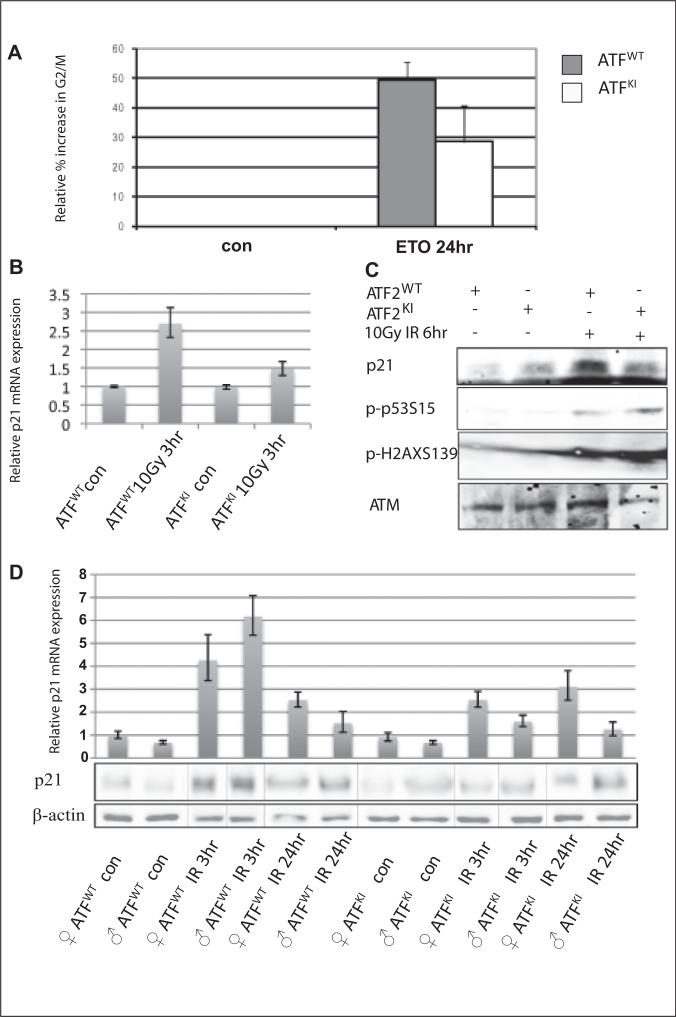

To determine the cellular and molecular basis of increased sensitivity of ATF2KI mice to IR, we isolated primary murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from both ATF2WT and ATF2KI embryos and subjected them to genotoxic stress in culture using the genotoxic drug etoposide (ETO).38,39 Cells were then analyzed for changes in cell cycle distribution. Compared with ATF2WT MEFs, ATF2KI MEFs exhibited impaired ability to undergo ETO-induced cell cycle arrest (Fig. 4A). Prolonged exposure to ETO (5 μM) resulted in a notably lower increase in G2/M in the ATF2KI MEFs (20%), compared with ATF2WT cells (40%; Fig. 4A). These findings point to the role of ATF2 phosphorylation by ATM in cellular response to DNA damage and the control of cell cycle progression.

Figure 4.

Expression of p21 is attenuated in ATF2KI cells and tissues subjected to genotoxic stress. (A) Murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) prepared from wild-type (ATF2WT) and ATF2KI animals were subjected to treatment with etoposide (ETO), and cells were harvested 8 or 24 hours later for assessment of cell cycle distribution using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Shown is the relative increase in the percentage of cells found to be in G2/M following ETO treatment. (B) Analysis of p21 transcripts was performed using qPCR analysis of cDNA prepared from RNA of the ATF2WT and ATF2KI MEFs at the indicated time points and doses of ionizing radiation (IR). (C) Western blot analysis of proteins prepared from ATF2WT or ATF2KI MEFs following IR (10Gy) or nonirradiated controls. Level of Ser15 on p53 and serine 139 on γH2AX (S139) served as controls for the cellular response to IR. Level of p21 proteins are shown (upper panel). (D) Real-time qPCR was performed on cDNA prepared from brain of ATF2WT or ATF2KI animals 3 and 24 hours after 8Gy IR. Representative experiment shown (out of 3 experiments, each using triplicates; error bars represent standard deviation). Western blots were performed with the same samples as the qPCR to determine the relative level of p21 protein.

Among proteins that mediate cell cycle arrest, including G2/M arrest following DNA damage, is p21, which is induced following genotoxic stimuli.40-42 Consistent with the impaired ability of ATF2KI MEFs to undergo genotoxic stress-dependent cell cycle arrest, these cells failed to induce p21 following exposure to IR (Fig. 4B,C), compared to ATF2WT cells that had a 3-fold induction of p21 expression 3 hours after exposure to DNA damage (10Gy IR; Fig. 4B,C). Notably, neither p21 mRNA or protein levels increased in ATF2KI MEFs (Fig. 4B,C). Importantly, this impaired activation of p21 following DNA damage was also seen in vivo. Comparison of the levels of p21 RNA and protein extracted from the brains (in which ATF2 expression is higher compared to other tissues) of ATF2WT and ATF2KI animals before and after IR revealed impaired induction of p21 expression in ATF2KI mice (Fig. 4D). ATM activity, as indicated by ATM phosphorylation at residue 1981 and the degree of p53 phosphorylation on Ser15, did not differ between the ATF2WT and ATF2KI MEFs (data not shown). These findings suggest that mutant ATF2 did not affect ATM activity. Impaired p21 activation and a corresponding G2/M arrest following DNA damage are likely to provide a molecular mechanism for the increased sensitivity of ATF2KI mice to IR. Consistent with this possibility, p21 mutant mice are more sensitive to IR.33

Regulation of p21 is subject to a complex set of regulatory cues at the level of transcription translation and post-translational modifications. Among key regulators of p21 transcription is p53, which is unaltered in ATF2KI cells, consistent with earlier studies demonstrating that ATF2 phosphorylation by ATM does not affect its transcriptional activity.21 Thus, a p53-independent mechanism is likely to contribute to impaired IR-induced p21 transcription seen in the ATF2KI cells and tissues.

GeneGo enrichment analysis identifies preferential changes in DNA damage/checkpoint networks in irradiated ATF2KI cells

To further elucidate the molecular differences in DNA damage response between ATF2WT and ATF2KI mice, we used microarray analysis to assess global transcription programs in ATF2WT and ATF2KI MEFs before and after IR. To do so, the ontology enrichment analysis workflow was employed in MetaCore to determine which networks in the GeneGo process may be altered when comparing data sets obtained from irradiated ATF2KI versus ATF2WT cells. Notably, the MetaCore analysis revealed that the processes associated with the DNA damage checkpoint are those that exhibit the most significant difference among the two groups (Fig. 5A). The number of genes involved in DNA damage checkpoint remained largely similar in both groups (80 in ATF2WT and 74 in AFT2KI samples), with cyclins (A, A2, D3) found to express following IR in the ATF2WT but not in the AFT2KI MEFs (Fig. 5B). Notably, the expression level of genes recorded in both samples was lower in AFT2KI versus ATF2WT samples. This statistically significant difference was shown to be 10.3 [-log (P value)] in ATF2WT versus 8.3 in the group (Fig. 5A). Real-time qPCR analysis confirmed that cyclin A and cyclin D3 have higher expression in ATF2WT MEFs than knock-in (ATF2KI) MEFs (Fig. 5C). As these cyclins are implicated in cell cycle checkpoint transition, the lack of their expression in the ATF2KI MEFs is consistent with the impaired cell cycle arrest phenotype identified for the ATF2KI MEFs and upon expression of ATF2, which is mutated in the ATM phosphorylation site.10 These findings also point to a more global change in checkpoint control genes whose expression is attenuated in AFT2KI cells.

ATF2KI mutations accelerate tumor progression in the p53 mutant mice

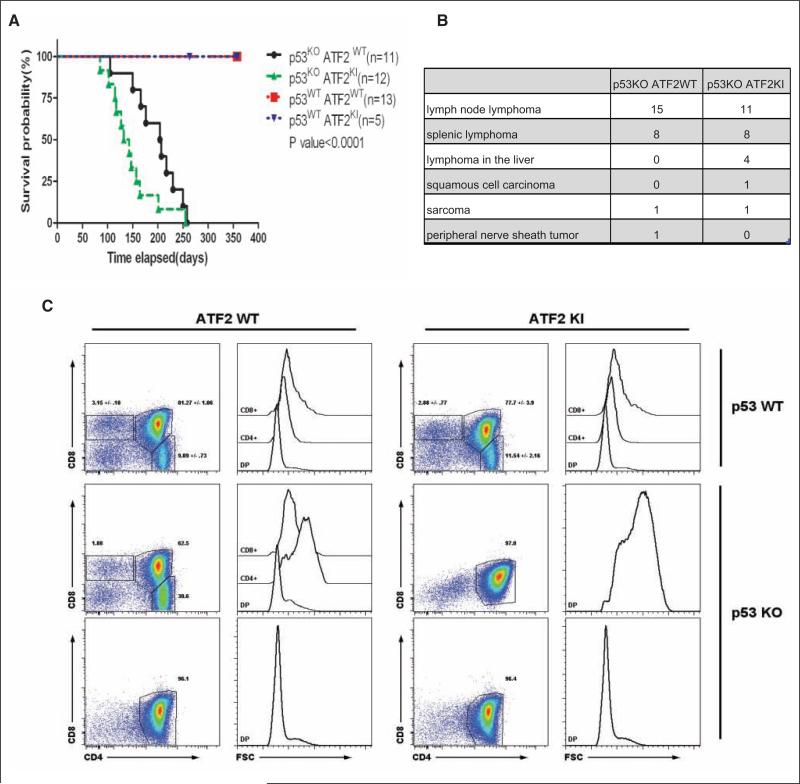

p53 mutant (p53KO) mice die of tumors prematurely through accumulation of somatic mutations resulting from genomic instability.43-46 Heterozygous loss of p53, combined with oncogene activation or loss of tumor suppressors, can also accelerate tumorigenesis due to the increased burden of mutations.47 Given the p53-independent role of ATF2 in the DNA damage response and impaired p21 seen in ATF2KI mice, we assessed changes in tumorigenesis in p53KOxATF2KI mice. To do so, we compared the following 4 groups: p53WTxATF2WT, p53WTxATF2KI, p53KOxATF2WT, and p53KOxATF2KI; p53WTxATF2WT and p53WTxATF2KI groups survived up to 1 year without tumors, whereas the p53KOxATF2WT and p53KOxATF2KI groups died of tumors within 280 days of birth (Fig. 6A). The median survival for p53KO mice was 207 days compared with 132 days for the p53KOxATF2KI group (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

ATF2KI accelerates tumor formation in p53KO animals. ATF2KI animals were crossed with p53KO animals, and the following genotypes were monitored for tumor development and survival: p53WTxATF2WT, p53WTxATF2KI, p53KOxATF2WT, and p53KOxATF2KI. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed p53KOATF2KI mice died of tumors earlier than p53KOATF2WT mice, with a median survival difference of 75 days (P < 0.0001). The p53WTATF2WT and p53WTATF2KI animals survived and showed no sign of tumors or sickness up to 1 year. (B) Summary of tumor types among the two genotypes. (C) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of thymic cells from 3- to 4-month-old mice of the wild-type (ATF2WT) and ATF2KI genotypes for frequency and size (FSC) of double-positive (DP), CD4 and CD8 single-positive (CD4+ or CD8+) positive cells. Values indicate the percentage and standard deviation (where noted, n = 3) of live cells.

Histological analysis of tumor types in the p53KO versus p53KOxATF2KI groups revealed that the majority of tumors were histologically similar, with the predominant tumor in both groups being T cell lymphoma found in the lymph nodes, spleen, and liver (Suppl. Fig. S5). The lymphoma in both groups was stained positive with the T cell marker CD3 (Suppl. Fig. S1) and appeared histologically identical in representative sections from all tissues in both genotypes. Interestingly, in addition to the T cell lymphomas, ATF2KI groups were found to have two skin tumors that were also reported in the p53KO animals (not shown). The table in Figure 6B summarizes the incidence and type of tumors identified in the two mouse groups.

These findings prompted us to assess changes in lymphocyte or thymocytes prior to the overt appearance of disease among the ATF2WT, ATF2KI, p53KO, and ATF2KIxp53KO animals. Flow cytometry of lymphocyte populations performed on 4- to 5-month-old animals showed no apparent alterations in lymphocyte or myeloid cell numbers, nor did it reveal any phenotype in the blood, spleen, or lymph node (data not shown). However, analysis of the thymus revealed severe alterations in the thymocyte populations in both p53KO and ATF2KIxp53KO animals but not in ATF2WT or ATF2KI genotypes. A 3- to 5-fold increase in total thymic cell numbers, which was associated with a loss of CD4 and CD8 single-positive cells and expansion of CD4/CD8 double positives, was found in p53KO (1/3) and ATF2KIxp53KO (2/3) animals (Fig. 6C). Other changes identified in these groups included a marked increase (~2.5-fold) in cell size, associated with reduced expression of CD3ε and a modest increase of CD25 levels (ATF2KIxp53KO) and a 3-fold increase toward CD4 single-positive cells, associated with increased cell size (p53KO). These data are consistent with the finding of T cell lymphoma as the major tumor type seen in both ATF2KIxp53KO and p53KO genotypes (Fig. 6B, Suppl. Fig. S1). Together these data suggest that ATF2 KI mutation reduces the age of disease onset and possibly affects its severity, but not the type of tumor formed.

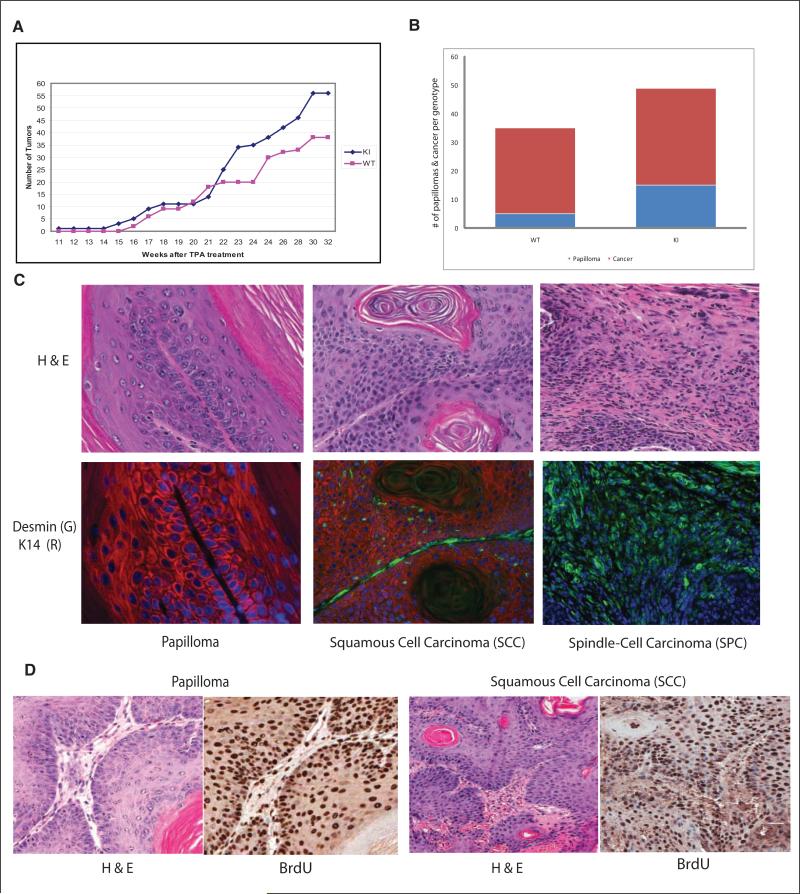

ATF2KI mice develop faster and a higher number of low-grade skin tumors

As an independent model to assess the possible role of ATF2KI in tumorigenesis, we subjected the ATF2KI and control group to the two-stage skin carcinogenesis protocol in which a single treatment with DMBA as the tumor initiator is followed by weekly topical application of the tumor promoter TPA to the skin, resulting in the formation of skin papillomas.48 In the C57/B6 strain, this protocol results in papillomas as early as 15 weeks following DMBA/TPA treatment, with subsequent development to squamous skin carcinomas by 20 weeks.49,50 Consistent with reported studies, skin tumors were observed in the control group 16 weeks after initiating the study50 (Fig. 7A). Notably, these lesions were observed as early as 11 weeks following DMBA/TPA administration in the ATF2KI mice (Fig. 7, Suppl. Fig. S2). Further, both the percentage of animals bearing tumors and the average tumor number per animal are higher in the ATF2KI group (Figs. 7a, 7b, Suppl. Fig. S2). Markedly, the ATF2KI group exhibited 15 papillomas compared with 5 papillomas in the ATF2WT control group (15 animals per group; Fig. 7B), indicating a higher incidence and multiple papillomas per animal in the ATF2KI group. These data indicate that latency period and incidence of skin tumor development are shorter in the ATF2KI animals.

Figure 7.

Low-grade skin tumors develop faster and at higher incidence in ATF2KI mice subjected to skin carcinogenesis protocol. Mice of the ATF2WT and ATF2KI genotypes were subjected to single application of DMBA followed by weekly topical application of TPA (see Materials and Methods for details). Measurement of lesions was performed at the indicated time points. (A) Number of tumors over time for each of the two groups is outlined. (B) The number of papillomas and tumors found in ATF2WT and ATF2KI animals is shown, based on histological and immunological analysis. (C) Tumors were subjected to H&E, K14, desmin, or BrdU staining as indicated. Shown are representative images (magnification 20x). Histopathological and immunological analysis identified the tumor types as papilloma, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), or spindle cell carcinoma (SPC). (D) Papillomas and SCC were subjected to BrdU analysis. Also shown is corresponding H&E staining.

Histological and pathological analysis of the tumors developed in both of the genotypes was complemented by immunostainings using antibodies to desmin and keratin markers, which distinguish (see Materials and Methods for details) squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) from the most advanced tumor type, spindle cell carcinomas (SPC; Fig. 7C, Suppl. Fig. S4). This analysis, performed 20 weeks following DMBA treatment, revealed that the ATF2KI group developed more cancerous lesions and at earlier time points compared to the control animals (Fig. 7A-C, Suppl. Fig. S4).

Papilloma conversion to SCC was overall comparable between the two groups (85% in the ATF2KI vs. 93% in the ATF2WT group; Fig. 7B,C, Suppl. Figs. S3, S4), suggesting that progression to carcinoma did not differ among the two groups. Notably, however, further progression to the more malignant stage, SPC, which is characterized by expression of EMT markers, was more pronounced in the ATF2KI compared with the ATF2WT group (15% vs. 7%, respectively; Suppl. Fig. S3). BrdU staining confirmed a highly proliferative state in papillomas and SCC forms (Fig. 7D, Suppl. Fig. S5). These findings suggest that ATF2 phosphorylation by ATM is important in the prevention of early stages of skin tumor formation, as reflected by the higher number and shorter latency. Further, ATM phosphorylation of ATF2 is also important in the progression of SCC to SPC, the more advanced form of skin tumors, as noted by the higher incidence of EMT-bearing SPC tumors identified in ATF2KI animals, compared with the ATF2WT group.

Discussion

The present study provides genetic evidence for the role of ATF2 in the DNA damage response and demonstrates the importance of ATF2 phosphorylation by ATM in radiation resistance as in tumorigenesis, using three different experimental models. Mice carrying ATF2 mutated in ATM phosphoacceptor sites exhibited greater sensitivity to IR and were more prone to develop tumors when crossed with p53 mutant mice or when subjected to skin carcinogenesis protocols. These findings underscore the physiological significance of our initial studies identifying ATF2 as an ATM substrate. Those studies provided biochemical evidence for ATF2 phosphorylation by ATM on residues 490/498 (of the human protein) and showed that such phosphorylation in response to DNA damage localized ATF2 to repair foci along with members of the MRN complex, as in the intra-S-phase checkpoint.10,25,26 Here, we reveal the significance of ATF2 as an ATM substrate in susceptibility to tumorigenesis as to DNA damage, pointing to its role in maintaining genomic stability.

Significantly, ATF2's role in the DNA damage response can be separated from its function as a transcription factor. In agreement, mice carrying a transcriptionally inactive form of ATF2 exhibit a lethal phenotype,29 unlike the ATF2KI mice studied here. In the present study, mutation of the ATF2 ATM phosphoacceptor sites did not appear to cause any overt phenotypes in nonirradiated animals but heightens sensitivity in response to genotoxic stress. This observation indicates the importance of ATF2 in the cellular response to exogenous DNA damage. ATF2 was also found to play an important role in tumor susceptibility, given the shorter latency of tumor development seen when the mutation was crossed to p53 mutant mice. Thus, in the absence of a p53 protective mechanism,51,52 ATF2 appears to augment mechanisms underlying genomic stability. This function appears to be p53 independent, as revealed from our mouse genetic studies.

Consistent with these findings, ATF2KI mice subjected to a two-stage skin carcinogenesis protocol developed a greater number of cancerous lesions more rapidly than non-mutated mice, augmenting changes induced by Ras oncogene mutation and tumor promotion, which in this protocol constitutes the underlying mechanism of tumor formation. Notably, ATF2KI mice were prone to develop tumors that also progressed to more advanced stages compared with ATF2WT animals. These findings point to the roles of ATM phosphorylation of ATF2 in both initiation and progression phases of skin tumor development. A possible explanation for the role of ATM-phosphorylated ATF2 in tumor progression may lie in its ability to affect expression of proteins that play a central role in cell cycle and mitosis.

The results in both tumor models—skin carcinogenesis and p53KO mice—revealed that in the absence of ATM phosphorylation of ATF2, there is greater susceptibility to develop cancerous lesions, pointing to a tumor suppressor function. The DNA damage function of ATF2, acquired upon its phosphorylation by ATM, augments its reported role as a tumor suppressor, which requires its transcriptional activity, at least in context of skin carcinogenesis and tumors carrying mutant p53.

Of note, localization of ATF2 phosphorylated by ATM in DNA repair foci could not be assessed in mouse cells or tissues since available phospho-antibodies raised against the human protein fail to recognize the phosphorylated mouse protein (sequences flanking the phosphoacceptor sites differ among the two species). Also, tissue or species differences may be attributed to the lack of ATF2-dependent changes in ATM activity, which were observed in human transformed cells but not in nontransformed mouse cells used in the present study.

Intriguingly, ATF2KI mice phenocopy p21–/– mice in IR sensitivity.33 Consistent with these observations is the striking difference between the p53 and p21 mutant mice; p53 knockout confers IR resistance, while p21–/– mice are more IR sensitive. Thus, despite the fact that p21 is a major target of p53 activation in response to DNA damage,40-42 p21-dependent radiosensitivity is p53 independent. Our findings support these differences, as ATF2 phosphorylation by ATM was required for p21 activation following DNA damage.

To address the question of how ATM phosphorylation of ATF2 contributes to the activation of p21 transcription, we analyzed a gene expression array and identified a cluster of genes involved in DNA damage checkpoint control as those most altered in expression by ATM phosphorylation of ATF2, consistent with our earlier finding of ATM-phosphorylated ATF2 role in intra-S-phase checkpoint control.10 Since earlier studies revealed that ATM phosphorylation of ATF2 does not affect its transcriptional activity per se, it is possible that such modification affects a more global gene expression program, possibly mediated by recruitment of histone-modifying enzymes. In agreement, ATF2 associates with TIP60 HAT and with SUV39a HDMET26 (unpublished findings). Furthermore, mass spectrometry analysis of ATF2KI-bound proteins identified a different class of histone tails bound to ATF2WT versus ATF2KI proteins (Ronai et al., unpublished data), implying that diverse recognition of modified histones may underlie ATF2's ability to contribute to specific patterns of gene expression.

In all, this study provides genetic evidence for the role of ATF2 in the control of response to DNA damage and susceptibility to develop tumors, implying a role in maintenance of genomic stability. Impaired phosphorylation of ATF2 by ATM resulted in higher sensitivity to IR, accelerated tumorigenesis in p53KO background, and higher incidence of early appearing papillomas in the skin carcinogenesis model. The present studies reveal that while inactivating ATF2 phosphorylation by ATM is not sufficient for spontaneous tumor formation, it effectively enhances genomic instability induced by mutant oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes. The latter is consistent with the reported tumor suppressor function associated with expression of a transcriptionally inactive form of ATF2, in mammary and nonmalignant skin tumors.53,54 In both cases, the transcriptionally dead ATF2 selectively expressed in mammary or keratinocyte cells was not sufficient to render a tumor phenotype. Yet, when combined with inactivated p53 or activated Ras, it accelerated the formation of mammary or nonmalignant skin tumors, respectively.28,53,54 How much of the latter phenotype can be attributed to the role of ATF2 in DNA damage response, as opposed to its transcriptional activities, will require further studies. Available data suggest that the two functions of ATF2 regulate distinct cellular mechanisms that complement each other in cellular response to stress and DNA damage.

Materials and Methods

Cells

MEFs were isolated from 13.5-day-old embryos according to standard protocol (http://discovery.wisc.edu/media/MIR_Images/RegBioPDFs/harvesting_MEF.pdf). All the MEFs cells used in this study have undergone fewer than 5 passages in culture and the MEFs used for cell cycle profiling fewer than 3 passages. Etoposide (cat. no. 341205, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) was dissolved in DMSO and used at the working concentration of 5 μM for the indicated time.

Engineering ATF2KI mice

ATF2 genomic sequences were isolated by screening a 129/ola mouse cosmid library (RZPD, Berlin, Germany). ATF2KI mutant clones (Ser to Ala substitutions corresponding to human residues 490 and 498, respectively) were generated by in vitro mutagenesis (Promega, Madison, WI) and insertion of genomic sequences into vector pPGKneobpAlox2PGKDTA (kindly received from Frank Gertler, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA). The ATF2KI targeting vector was electroporated into AMK6 mouse (129S7-based) ES cells, and the cells were placed under G418 selection. Surviving clones were arrayed in a 96-well format, and DNA was prepared by Proteinase K treatment and ethanol precipitation of the genomic DNA. The DNA was resuspended in 20 μL TE, and 3 μL was used in a nested PCR assay employing primers to the Neomycin drug selection gene and to ATF2 sequences that were 3′ of exon 11 and not included within the targeting vector. Proper targeting of ATF2 in the ES cells was indicated by the presence of a 2-kb PCR fragment in these reactions. Two independent clones were identified in these experiments and expanded for use in blastocyst microinjections. Both clones gave rise to high-degree chimeric mice, which were subsequently bred to C57Bl/6 mice. Germline transmission of the targeted allele as assessed by coat color was obtained using both ES clones, which was confirmed by genotyping of select agouti F1 offspring. These mice were then crossed with Protamine-Cre transgenic mice to obtain ATF2KI/+, Pr-Cre male mice, which were bred with C57Bl/6 wild-type mice. Mice were identified by PCR analysis in the F2 litter that correctly deleted the drug selection marker within the ATF2KI targeted allele, resulting in the ATF2KI model. The ATF2KI mice were utilized in a congenic back-crossed with C57Bl/6 inbred mice for 9 additional generations, then intercrossed in order to obtain ATF2KI homozygous mice on a pure C57Bl/6 genetic background.

Mouse genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from tail tissue with protocol reported before.53 DNA was subjected to PCR reaction, resulting in amplification of an 857-bp DNA fragment spanning exon 11 and mutant phosphoacceptor sites. Digestion of the amplified fragment with the restriction enzyme MwoI resulted in the formation of 2 fragments, with MW of 287 and 570 bp (Fig. 1B). The presence of the point mutation, which displaces the phosphoacceptor site at aa 472/480, results in the formation of an additional site for MwoI cleavage. As a result, mutant allele exhibits 3 fragments of 119, 287, and 451 bp in the case of the homozygous allele. A heterozygous form will exhibit all 4 fragments (Fig. 1B). The integrity of this analysis was confirmed by sequencing reactions performed when the method was set up and later in 10% of samples subjected to confirmation analysis.

Whole-body irradiation

All the animals from both ATF2WT and KI group were between 2 and 3 months old. These animals were fed with neomycin (Fisher Bioreagents CAT. No. BP266925; 2 g/L in drinking water) a week before γ-irradiation and were kept on neomycin after irradiation. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve and statistics were created with GraphPad Prism 5.

Cell sorting

Cell cycle and death analysis: 106 MEFs were fixed in 70% ethanol in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at –20°C. Before FACS analysis, MEFs were washed and resuspended in PBS with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 50 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI; cat. no. P4170, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 50 μg/mL RNAse A (cat. no. R4875, Sigma-Aldrich) for staining for 30 minutes in the dark. FACS analysis was performed at the flow cytometry core facility in the Burnham Institute. Flow cytometry—B/T cell analysis: Single-cell suspensions were prepared from spleen, inguinal lymph node, and thymus by physical dissociation between glass slides and from peritoneal cavity by lavage with 10 mL PBS. Cells were manually counted using a hemacytometer. Cells were stained as follows according to the manufacturer's instructions; all antibodies were from eBisocience. Thymus and lymph node: anti-CD4 FITC, -CD25 PE, -CD8a PerCP, -CD11b PE-Cy7, -CD3ε APC, and -B220 APC-Cy7. Peritoneal cavity: anti-CD5 biotin followed with anti-IgD FITC, -CD23 PE, sAv PerCP-Cy5.5, -CD1b PE-Cy7, -IgM APC, and -B220 APC-Cy7. Bone marrow: anti-IgD FITC, -CD43 PE, -B220 PerCP-Cy5.5, -CD1b PE-Cy7, -IgM APC, and -CD19 APC-Cy7. Spleen: anti-CD5 biotin followed with anti-CD21 FITC, -CD23 PE, -sAv PerCP-Cy5.5, -CD1b PE-Cy7, -IgM APC, and -B220 APC-Cy7. Flow cytometric data were acquired on a FACSCanto 6-color flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

Pathological evaluation of skin tumors

All tumor samples (94) were stained with H&E and scored for the following: invasion of the basement membrane, presence/absence of atypical squamous cells, high nuclear to cytoplasmic diameter ratio, intercellular bridges, inflammation, hyperchromasia, keratinous pearls, the appearance of the stroma, nuclei shape, and if any clusters of tumor cells were present. Samples were then taken and immunohistopathology was performed. Using desmin as an indicator, samples were first categorized by the presence or absence of desmin; samples were then analyzed for keratin markers. Using the following criteria, all samples were categorized into the following tumor types:

Squamous cell papilloma (SCP): The subjacent vessels and connective tissue (fibrovascular core) grow to sustain and feed the tumor. The tumor cells resemble normal squamous cells, but there is an increase of the layer number: hyperkeratosis; the basement membrane is intact. Negative for desmin and K10 and positive for K14. Diminished to absent K14 signal with strong desmin and K10 signal in the core.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC): intraepidermal proliferation of atypical keratinocytes. Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and confluent parakeratosis are seen within the epidermis, and the keratinocytes lie in complete disorder, resulting in the classic “wind-blown” appearance. Cellular atypia, including pleomorphism, hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitoses, is prominent. Tumor cells transform into keratinized squames and form round nodules with concentric, laminated layers, called “cell nests” or “epithelial/keratinous pearls.” The surrounding stroma is reduced and contains inflammatory infiltrate (lymphocytes). Diminished to absent K14 signal with sporadic desmin signal localized in linear tube-like structures and high K10 signal with sporadic K8 detection. 3. Spindle-cell carcinoma (SPC): elongated cells with central, elongated nuclei that are arranged in entangled fascicles and intertwining bundles that exhibit hyperchromasia, enlarged nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, and no keratinization. Undetectable K14 with a widespread desmin signal and persistent K10 signal and strong but scattered K8.

Westerns and antibodies

Western blots were performed as described.26 Phospho-ATM (ser 1981) antibody (cat. no. ab36810, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was used at 1:2000. ATM antibody (cat. no. 2873, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) was used at 1:2000. Phospho-H2AX (ser 139) antibody (05-636, Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used at 1:1000. Phospho-p53 (ser 15) antibody (cat. no. 9284, Cell Signaling Technology) was used at 1:2000. p21 antibody (BD Biosciences) was used at 1:1000.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNAs were prepared with the GenElute Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep Kit (cat. no. MRN70, Sigma-Aldrich) and reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (cat. no. 4368814, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). qPCR was performed with the SYBR® GreenER™ Reagent System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The p21 and β-actin rimers were synthesized as published previously.55,56

Gene ontology analysis

Illumina Microarray data were obtained (mouse chip MouseRef-8_V2_0_R0_11278551_A) from control or irradiated (10Gy) MEF of ATF2WT (control) or ATF2KI mice. Raw array data were analyzed first in BeadStudio 3.0 (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA). Gene expression data were first corrected to background and normalized by the cubic spline method. Changes in the level of expression and significance (P values) values for all genes (18133) were submitted for pathways and networks analysis in MetaCore (GeneGO, Inc., Saint Joseph, MI). We used ontology enrichment analysis workflow in MetaCore to determine which GeneGo process networks are differentially affected in two data sets (ATF2WT vs. ATF2KI). In this analysis, we used two cutoffs: threshold for gene expression was defined as 10 (genes that normalized gene expression level less than 10 were not included in the analysis), and P value cutoff used was P < 0.001 (genes with a P value for expression level more or equal to 0.001 were not included in the analysis).

Two-stage skin carcinogenesis protocol

For mouse skin carcinogenesis, the dorsal skin of each mouse (15 ATF2KI and 15 ATF2WT mice) was shaved, using an electric shaver, 2 days before it was treated with a single topical application of 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA; 10 μg in 100 μL of acetone).57 One week later, the same area was shaved, and the mice were treated topically with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 10 μg in 200 μL of acetone; Sigma) once a week for 32 weeks. At the termination of the experiment (32 weeks after first application of TPA), mice were euthanized.

Tissue harvest and histology

Representative biopsies from all skin tumors were collected, fixed in Z-fix (Anatech Ltd., Battle Creek, MI) for 24 hours, washed 3 times with PBS, and stored in PBS for less than 24 hours before embedding in paraffin. Deparaffinized sections (5 μm thick) were stained with H&E for pathological evaluation (IDEXX, Irvine, CA).

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

All sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, washed in PBS, and blocked with Dako protein block for 30 minutes at room temperature. Antigen retrieval was performed in a pressure cooker (Deni electric pressure cooker) in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 15 minutes at 15 psi, pressure was released slowly, and samples were allowed to cool for 1 hour at room temperature and used for anti–cytokeratin 10, biotinylated anti–cytokeratin 14, anti–cytokeratin 8, antidesmin, and BrdU immunostaining. Antibodies/dilutions for the following markers were used in Dako antibody diluent and applied overnight at 4°C: rabbit anti–cytokeratin 10 and 14 (1:50, 1:2000; Covance, Princeton, NJ), biotinylated anti–cytokeratin 14 (1:1250; Lab Vision, Fremont, CA), rabbit antidesmin (1:250; Thermo, Waltham, MA), and cytokeratin 8 antibody (TROMA-1; 1:1000, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). Secondary antibodies labeled with Alexa Fluor 488, Alexa Fluor 594, or Alexa Fluor 594 streptavidin conjugate were placed on tissue sections for 1 hour at room temperature (1:400; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Nuclei were counterstained using SlowFade Gold Anti-fade reagent with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector, Burlingame, CA). BrdU staining (BrdU antibodies 1:2000; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was followed as above, but Dako secondary rabbit was used for 2 hours at room temperature in a humidified chamber washed in PBS and incubated with diaminobenzidine substrate (DAB) and counterstained with hematoxylin. TUNEL staining was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (cat. no. s7101, Millipore).

BrdU incorporation

DMBA/TPA–treated mice were injected i.p. with BrdU (0.1 mg/g of body weight; Sigma) 1 hour before the mice were euthanized. Dorsal skins or intestines were removed, fixed as stated, and processed for paraffin embedding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Shelley for help with IHC staining of lymphoma samples and Charis Tjoeng for help with qPCR analyses.

Funding

Support by NCI grant (CA117927 to ZR) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supplementary material for this article is available on the Genes & Cancer Web site at http://ganc.sagepub.com/supplemental.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Jackson SP, Bartek J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature. 2009;461:1071–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavin MF. Ataxia-telangiectasia: from a rare disorder to a paradigm for cell signalling and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:759–69. doi: 10.1038/nrm2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiloh Y. ATM and related protein kinases: safeguarding genome integrity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:155–68. doi: 10.1038/nrc1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. Initiating cellular stress responses. Cell. 2004;118:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature. 2003;421:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cimprich KA, Cortez D. ATR: an essential regulator of genome integrity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:616–27. doi: 10.1038/nrm2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuoka S, Huang M, Elledge SJ. Linkage of ATM to cell cycle regulation by the Chk2 protein kinase. Science. 1998;282:1893–7. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sorensen CS, Syljuasen RG, Falck J, Schroeder T, Ronnstrand L, Khanna KK, et al. Chk1 regulates the S phase checkpoint by coupling the physiological turnover and ionizing radiation-induced accelerated proteolysis of Cdc25A. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:247–58. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson L, Henderson C, Adachi Y. Phosphorylation and rapid relocalization of 53BP1 to nuclear foci upon DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1719–29. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.5.1719-1729.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhoumik A, Takahashi S, Breitweiser W, Shiloh Y, Jones N, Ronai Z. ATM-dependent phosphorylation of ATF2 is required for the DNA damage response. Mol Cell. 2005;18:577–87. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S, Ting NS, Zheng L, Chen PL, Ziv Y, Shiloh Y, et al. Functional link of BRCA1 and ataxia telangiectasia gene product in DNA damage response. Nature. 2000;406:210–5. doi: 10.1038/35018134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lou Z, Minter-Dykhouse K, Wu X, Chen J. MDC1 is coupled to activated CHK2 in mammalian DNA damage response pathways. Nature. 2003;421:957–61. doi: 10.1038/nature01447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bao S, Tibbetts RS, Brumbaugh KM, Fang Y, Richardson DA, Ali A, et al. ATR/ATM-mediated phosphorylation of human Rad17 is required for genotoxic stress responses. Nature. 2001;411:969–74. doi: 10.1038/35082110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen MJ, Lin YT, Lieberman HB, Chen G, Lee EY. ATM-dependent phosphorylation of human Rad9 is required for ionizing radiation-induced checkpoint activation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16580–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakanishi K, Taniguchi T, Ranganathan V, New HV, Moreau LA, Stotsky M, et al. Interaction of FANCD2 and NBS1 in the DNA damage response. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:913–20. doi: 10.1038/ncb879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siliciano JD, Canman CE, Taya Y, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Kastan MB. DNA damage induces phosphorylation of the amino terminus of p53. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3471–81. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canman CE, Lim DS, Cimprich KA, Taya Y, Tamai K, Sakaguchi K, et al. Activation of the ATM kinase by ionizing radiation and phosphorylation of p53. Science. 1998;281:1677–9. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khanna KK, Keating KE, Kozlov S, Scott S, Gatei M, Hobson K, et al. ATM associates with and phosphorylates p53: mapping the region of interaction. Nat Genet. 1998;20:398–400. doi: 10.1038/3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waterman MJ, Stavridi ES, Waterman JL, Halazonetis TD. ATM-dependent activation of p53 involves dephosphorylation and association with 14-3-3 proteins. Nat Genet. 1998;19:175–8. doi: 10.1038/542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu Y, Baltimore D. Dual roles of ATM in the cellular response to radiation and in cell growth control. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2401–10. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barlow C, Hirotsune S, Paylor R, Liyanage M, Eckhaus M, Collins F, et al. Atm-deficient mice: a paradigm of ataxia telangiectasia. Cell. 1996;86:159–71. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu Y, Ashley T, Brainerd EE, Bronson RT, Meyn MS, Baltimore D. Targeted disruption of ATM leads to growth retardation, chromosomal fragmentation during meiosis, immune defects, and thymic lymphoma. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2411–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakagawa K, Taya Y, Tamai K, Yamaizumi M. Requirement of ATM in phosphorylation of the human p53 protein at serine 15 following DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2828–34. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buschmann T, Potapova O, Bar-Shira A, Ivanov VN, Fuchs SY, Henderson S, et al. Jun NH2-terminal kinase phosphorylation of p53 on Thr-81 is important for p53 stabilization and transcriptional activities in response to stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2743–54. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2743-2754.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhoumik A, Lopez-Bergami P, Ronai Z. ATF2 on the double-activating transcription factor and DNA damage response protein. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2007;20:498–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2007.00414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhoumik A, Singha N, O'Connell MJ, Ronai ZA. Regulation of TIP60 by ATF2 modulates ATM activation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17605–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802030200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacLaren A, Black EJ, Clark W, Gillespie DA. c-Jun-deficient cells undergo premature senescence as a result of spontaneous DNA damage accumulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9006–18. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.9006-9018.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez-Bergami P, Lau E, Ronai Z. Emerging roles of ATF2 and the dynamic AP1 network in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(1):65–76. doi: 10.1038/nrc2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Breitwieser W, Lyons S, Flenniken AM, Ashton G, Bruder G, Willing-ton M, et al. Feedback regulation of p38 activity via ATF2 is essential for survival of embryonic liver cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2069–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.430207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Gorman S, Dagenais NA, Qian M, Marchuk Y. Protamine-Cre recombinase transgenes efficiently recombine target sequences in the male germ line of mice, but not in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14602–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Risitano AM, Maciejewski JP, Selleri C, Rotoli B. Function and malfunction of hematopoietic stem cells in primary bone marrow failure syndromes. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2007;2:39–52. doi: 10.2174/157488807779316982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Komarova EA, Christov K, Faerman AI, Gudkov AV. Different impact of p53 and p21 on the radiation response of mouse tissues. Oncogene. 2000;19:3791–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Komarova EA, Kondratov RV, Wang K, Christov K, Golovkina TV, Goldblum JR, et al. Dual effect of p53 on radiation sensitivity in vivo: p53 promotes hematopoietic injury, but protects from gastro-intestinal syndrome in mice. Oncogene. 2004;23:3265–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng W, Viar MJ, Johnson LR. Polyamine depletion inhibits irradiation-induced apoptosis in intestinal epithelia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G599–606. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00564.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan WB, Shui C, Ning S, Knox SJ. Enhancement of murine intestinal stem cell survival after irradiation by keratinocyte growth factor. Radiat Res. 1997;148:248–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christiansen H, Batusic D, Saile B, Hermann RM, Dudas J, Rave-Frank M, et al. Identification of genes responsive to gamma radiation in rat hepatocytes and rat liver by cDNA array gene expression analysis. Radiat Res. 2006;165:318–25. doi: 10.1667/rr3503.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Angulo P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1221–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra011775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soubeyrand S, Pope L, Hache RJ. Topoisomerase IIalpha-dependent induction of a persistent DNA damage response in response to transient etoposide exposure. Mol Oncol. 2010;4:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bansal P, Lazo JS. Induction of Cdc25B regulates cell cycle resumption after genotoxic stress. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3356–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiong Y, Hannon GJ, Zhang H, Casso D, Kobayashi R, Beach D. p21 is a universal inhibitor of cyclin kinases. Nature. 1993;366:701–4. doi: 10.1038/366701a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harper JW, Adami GR, Wei N, Keyomarsi K, Elledge SJ. The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell. 1993;75:805–16. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.el-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, Levy DB, Parsons R, Trent JM, et al. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75:817–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harvey M, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA, Jr, Butel JS, Bradley A, Donehower LA. Spontaneous and carcinogen-induced tumorigenesis in p53-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 1993;5:225–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1193-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA, Jr, Butel JS, et al. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–21. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kemp CJ, Wheldon T, Balmain A. p53-deficient mice are extremely susceptible to radiation-induced tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 1994;8:66–9. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, Schmitt EM, Halachmi S, Bronson RT, et al. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr Biol. 1994;4:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang RH, Sengupta K, Li C, Kim HS, Cao L, Xiao C, et al. Impaired DNA damage response, genome instability, and tumorigenesis in SIRT1 mutant mice. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:312–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuspa SH. The pathogenesis of squamous cell cancer: lessons learned from studies of skin carcinogenesis—thirty-third G. H. A. Clowes Memorial Award Lecture. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1178–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bremner R, Kemp CJ, Balmain A. Induction of different genetic changes by different classes of chemical carcinogens during progression of mouse skin tumors. Mol Carcinog. 1994;11:90–7. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940110206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reiners JJ, Jr, Nesnow S, Slaga TJ. Murine susceptibility to two-stage skin carcinogenesis is influenced by the agent used for promotion. Carcinogenesis. 1984;5:301–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/5.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Efeyan A, Serrano M. p53: guardian of the genome and policeman of the oncogenes. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1006–10. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.9.4211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lane DP. Cancer: p53, guardian of the genome. Nature. 1992;358:15–6. doi: 10.1038/358015a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhoumik A, Fichtman B, Derossi C, Breitwieser W, Kluger HM, Davis S, et al. Suppressor role of activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2) in skin cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1674–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706057105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maekawa T, Shinagawa T, Sano Y, Sakuma T, Nomura S, Nagasaki K, et al. Reduced levels of ATF-2 predispose mice to mammary tumors. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1730–44. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01579-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu R, Wang L, Chen G, Katoh H, Chen C, Liu Y, et al. FOXP3 up-regulates p21 expression by site-specific inhibition of histone deacetylase 2/histone deacetylase 4 association to the locus. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2252–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu AW, Kaelin CB, Morton GJ, Ogimoto K, Stanhope K, Graham J, et al. Effects of hypothalamic neurodegeneration on energy balance. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ewing MW, Conti CJ, Phillips JL, Slaga TJ, DiGiovanni J. Further characterization of skin tumor promotion and progression by mezerein in SENCAR mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:676–82. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.9.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.