Abstract

Sirt1 has been associated with various effects of calorie restriction, including an increase in lifespan. Here we show in mice that a central regulatory component in energy metabolism, the hypothalamic melanocortin system, is affected by Sirt1, which promotes the activity and connectivity of this system resulting in negative energy balance. In adult mice, the pharmacological inhibition of brain Sirt1 activity decreased the inhibitory tone on the anorexigenic POMC neurons, as measured by the number of synaptic inputs to these neurons. When a Sirt1 inhibitor (EX-527) was injected either peripherally (i.p., 10mg/kg) or directly into the brain (i.c.v., 1.5 nmol/mouse), it decreased both food intake during the dark cycle and ghrelin-induced food intake. This effect on feeding is mediated by upstream melanocortin receptors, because the MC4R antagonist, SHU9119, reversed Sirt1’s effect on food intake. This action of Sirt1 required an appropriate shift in the mitochondrial redox state: in the absence of such an adaptation enabled by the mitochondrial protein, UCP2, Sirt1-induced cellular and behavioral responses were impaired. The selective knockout of Sirt1 in hypothalamic Agrp neurons through the use of Cre-Lox technology decreased electric responses of Agrp neurons to ghrelin and decreased food intake, leading to decreased lean mass, fat mass and body weight. The present data indicate that Sirt1 has a central mode of action by acting on the NPY/Agrp neurons to affect body metabolism.

Keywords: arcuate nucleus, mitochondria, synapses, feeding, NPY, ghrelin

Introduction

Sirtuins are NAD+-dependent class III deacetylases that are highly conserved across species (Brachmann et al., 1995). Sirt1, the mammalian ortholog of Sir2, has been implicated in caloric-restriction-induced longevity (Kaeberlein et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2000; Tissenbaum and Guarente, 2001; Cohen et al., 2004; Rogina and Helfand, 2004; Chen et al., 2005). Nutrient deprivation upregulates Sirt1 in several tissues (Cohen et al., 2004; Ramadori et al., 2008), which is crucial for the metabolic shift that occurs during negative energy balance (Liu et al., 2008), a metabolic state in which the energy expenditure is higher than the energy intake.

Evidence suggests that the effects of sirtuins mimic the beneficial effects of calorie restriction, the only known physiological intervention that promotes a longer, healthier lifespan across species (Kaeberlein et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2000; Tissenbaum and Guarente, 2001; Cohen et al., 2004; Rogina and Helfand, 2004; Chen et al., 2005; Chen and Guarente, 2007). The similarities between the action of sirtuins and calorie restriction raise the possibility that sirtuins may exert their effect, at least in part, by affecting brain circuits controlling negative energy balance, the metabolic state promoted by calorie restriction.

The central melanocortin system located in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) of the hypothalamus is involved in the regulation of energy metabolism (Cone, 2006). This system consists of two components: a neuronal population that produces neuropeptide Y (NPY), agouti-related protein (Agrp) and gamma-amino-butyric acid (GABA), which promotes feeding in response to hunger and thus, negative energy balance; and a neighboring cell population producing proopiomelanocortin (POMC)-derived peptides, such as α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH), cocaine-and-amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) peptides, which promotes satiety and thus, positive energy balance. The interaction between these two sets of neurons is such that the NPY/Agrp neurons maintain a unidirectional tonic inhibition onto the POMC neurons (Horvath et al., 1992; Cowley et al., 2001; Pinto et al., 2004). The selective elimination of the orexigenic NPY/Agrp neurons in adult mice leads to cessation of feeding (Gropp et al., 2005) and death (Luquet et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2009). The interaction and connectivity of these hypothalamic circuits are not static; they exhibit substantial plasticity depending on the metabolic environment (Pinto et al., 2004; Gao et al., 2007), a process that relies on the redox state and plasticity of the mitochondria (Andrews et al., 2008).

Sirt1 is expressed in the hypothalamus (Ramadori et al., 2008), its function is redox-dependent (Prozorovski et al., 2008), and it is induced by negative energy balance (Cohen et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2008; Ramadori et al., 2008). Therefore, Sirt1 may play a role in cellular adaptations in response to negative energy balance. In the brain, the central melanocortin system regulates energy metabolism (Cone, 2006) and its adaptive responses to a changing metabolic environment include synaptic (Pinto et al., 2004; Gao et al., 2007; Andrews et al., 2008) and mitochondrial plasticity (Coppola et al., 2007; Andrews et al., 2008). Here, we examined whether Sirt1 activity may play a role in these cellular adaptations.

Material and Methods

Animals

Adult male mice were used in the pharmacological studies. The mice were at least 2 months old when single housed for food intake measurements and they were allowed to habituate to single housing for at least 2 weeks before the start of experiments. All animals were kept in temperature and humidity controlled rooms, in a 12/12h light/dark cycle, with lights on from 7:00AM-7:00PM. Food and water were provided ad libitum, unless otherwise stated. The total number of animals used for these experiments is 247.

Transgenic mice

UCP2 knockout mice were generated as reported previously (Zhang et al., 2001) and the original breeding pairs were kindly provided by Dr. Bradford Lowell (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), and have been maintained in our laboratory on a mixed background. This transgenic mouse is available from The Jackson Laboratory: B6.129-Ucp2tm1Lowl/J, Stock number 005934). POMC-GFP and NPY-GFP mice were provided by Dr. J. Friedman (Rockefeller University, New York, NY) and have been maintained on a B6 background for more than 10 generations. Both the NPY-GFP (B6.Cg-Tg(NPY-MAPT/Sapphire)1Rck/J; stock number 008321) and the POMC-GFP (B6.Cg-Tg(Pomc-MAPT/GFP*)1Rck/J, stock number 008322) mice are available from The Jackson Laboratory. Sirt1loxP/loxP mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (B6; 129-Sirt1tm1gu/J; stock number 008041) and have been generated as published (Li et al., 2007). Tg.AgrpCre mice have been maintained in our colony on a mixed background (Kaelin et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2005b; Xu et al., 2005a) and backcrossed to the reporter line Rosa26 mice (B6.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1Sor - originally from The Jackson Laboratory). All procedures were approved by local committees (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee from Yale University and from Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul).

Generation of Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice

To evaluate the role of Sirt1 in relation to NPY/Agrp neurons and the regulation of metabolism, we used Cre/Lox technology to knockdown the catalytic domain of Sirt1 in this population of cells. Transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase selectively in the Agrp-expressing cells (Kaelin et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2005b; Xu et al., 2005a) were bred with mice harboring a targeted mutant Sirt1 allele (Sirt1loxP) (Li et al., 2007). The Sirt1loxP/loxP mice contain loxP sequences flanking the exon 4 of the Sirt1 gene, which encodes 51 amino acids of the Sirt1 catalytic domain. When bred with the AgrpCre+ mice, the deleted Sirt1 allele (Sirt1Δex4) transcribes a mutant protein that has no apparent residual Sirt1 activity or dominant negative effects (Cheng et al., 2003; Li et al., 2007). Thus, we used this knockdown model of Sirt1 in the NPY/Agrp neurons to further elucidate the role of this sirtuin in body metabolism. We describe our data by referring to “control” and “Agrp-Sirt1 KO” mice.

In order to generate Agrp-specific Sirt1 KO mice we used established breeding strategies similar for this Cre line (Xu et al., 2005b; Xu et al., 2005a); see Supplemental Figure 7. To evaluate the specificity and efficacy of the Cre deletion, we used Rosa26 reporter mice (Soriano, 1999). We found rates of ectopic expression of Cre (around 30–40%) similar to those reported previously (Xu et al., 2005b; Xu et al., 2005a). This Cre line has been validated in several previous reports (Xu et al., 2005b; Xu et al., 2005a; Kitamura et al., 2006; Könner et al., 2007).

By breeding Tg.AgrpCre+-Sirt1loxP/+ with Sirt1loxP/loxP mice, we were able to get Mendelian ratios of Cre and floxed alleles in the offspring. In the first characterization period, we found that the Cre deleted heterozygote mice for the Sirt1loxP allele (Tg.AgrpCre+-Sirt1Δex4/+) exhibited an intermediate phenotype compared to control littermates and homozygote KO mice (Tg.AgrpCre+-Sirt1Δex4/Δex4). The mice carrying the AgrpCre allele and their Cre negative controls showed no differences in phenotype (data not shown), in accordance with previous reports (Xu et al., 2005b; Xu et al., 2005a; Pierce and Xu, 2010). Thus, we pooled the Cre negative mice (control group) and Cre positive mice without the floxed allele.

Metabolic chamber recordings

Adult female mice (n=11) were acclimated in metabolic chambers (TSE Systems, Germany – Core Metabolic Phenotyping Center, Yale University) for 4 days before the start of the recordings. Mice were continuously recorded for 3 days with the following measurements being taken every 30 minutes: water intake, food intake, ambulatory activity (in X and Z axes), and gas exchange (O2 and CO2) (using the TSE LabMaster system, Germany). VO2, VCO2 and energy expenditure were calculated according to the manufacturer’s guidelines (PhenoMaster Software, TSE Systems). The respiratory exchange rate (RER) was estimated by calculating the ratio of VCO2/VO2. Values were adjusted by body weight to the power of 0.75 (kg−0.75) where mentioned.

For the fasting response study, the same mice used above were acclimated to the cages for 4 days and then food was removed from the cages 2 hours before the dark cycle. The metabolic parameters (cited above) were recorded during ZT 12–18 and the data were analyzed as above.

Body composition

Adult male (n=13) and female (n=11) control and Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice were scanned in a Lunar PIXImus Densitometer (GE Medical Systems) in the Department of Orthopedics at Yale University, and their body composition was estimated based on manufacturer’s algorithms. All mice were sedated with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine before scanning.

Food intake measurements

For nocturnal food intake, animals were weighed and injected 30–60 minutes before the beginning of the dark cycle (ZT 11). Food pellets were weighed and added to the mouse cage at the start of the dark cycle (ZT 12). Food intake was measured after 4 hours (ZT 16) and overnight (ZT 0). For ghrelin-induced feeding, mice received the first treatment (i.p., 1 µg/g body weight) in the middle of the light cycle (ZT 6) and the second injection 30–60 minutes later (ZT 7). Food pellets were then weighed and added to the mouse cages 30 minutes after the last injection, and food intake was measured every hour for 4 hours. Before the start of the experiments, the home cages were changed to avoid biased results due to mice eating food that may have been deposited in the bedding of the cages. After the experiments, all cages were inspected for food spillage, and those mice in cages with visible food deposits in the bedding were excluded from the studies. However, it is important to note that very few mice had to be excluded from our experiments due to food spillage (2 mice out of 173). We observed that giving mice fewer food pellets (but enough for ad lib feeding) in the cage during the single housing acclimatization period resulted in considerably less food spillage.

For the experiments in which food intake, water intake and locomotor activity were followed concomitantly, mice were allowed to acclimate to the metabolic chambers (TSE Systems, Germany) for 4 days before the start of the recording. Mice were recorded for 24 h before and after EX-527 treatment. For the dose-response and SHU9119 studies, mice were recorded overnight (bin size for all experiments = 30 min). All measurements were taken automatically through the use of the LabMaster Phenotyping sytem (TSE Systems, Germany).

Intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) cannulation

Mice were injected with buprenorphine administered subcutaneously (s.c., 0.05 mg/kg) 30 minutes before surgery. They were anesthetized using a mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) given intraperitoneally (i.p.). Mice were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (Kopf Instruments) and a small cut was made in the skin above the skull. A drop of a pharmaceutical H2O2 solution was placed on the skull for better visualization of bregma and lambda. A small hole was carefully drilled into the skull, enough to insert the cannula (26G, Plastics One). Coordinates were +1.0 mm (lateral), −0.5 mm (posterior), +2.0 mm (caudal) from bregma (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001). Animals were kept warm and proper postsurgical care was taken.

Drug injections

For i.p. injections, a volume of 10 ml/kg of solution was injected, and for i.c.v., 3 µl were slowly injected into the lateral ventricles, using a 5–10 µl Hamilton syringe (Hamilton Company, Nevada, USA) connected to a calibrated polyethylene tube. After the experiments, cannula placement was confirmed by injecting methylene blue. Six mice out of the 219 mice were excluded due to misplaced canulas..

Several compounds have been shown to modulate Sirt1 activity. More recently, synthetic compounds acting directly on Sirt1 have also been developed with higher affinity and specificity (Napper et al., 2005). One of these compounds, EX-527 (Napper et al., 2005) has been extensively studied (Napper et al., 2005; Solomon et al., 2006; Nie et al., 2009; Pacholec et al., 2010); EX-527 is a low molecular weight, cell permeable, biostable molecule that binds directly to the Sirt1 catalytic domain and inhibits its activity (Huhtiniemi et al., 2006; Pacholec et al., 2010). Thus, we have chosen to use this molecule to pharmacologically inhibit Sirt1 activity. EX-527 (Tocris Bioscience, MI, USA) was freshly prepared, dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) to a stock concentration of 50 mM, and was then diluted in ultra-pure water to a final concentration of between 0.3–3.0 nmol/3µl (with the DMSO final concentration between 1–2%); appropriate vehicles were used as controls. Mice were injected with 3 µl drug solution or vehicle i.c.v. For the SHU9119 experiment, SHU9119 (Sigma-Aldrich, MI, USA – 140 pmol/mouse) was injected concomitantly with EX-527 (1.5 nmol/mouse). All solutions were sterile filtered through 0.2 µm syringe filters (Pall Corporation, MI, USA).

Immunohistochemistry for GFP and c-fos

GFP and c-fos double immunohistochemistry was performed by sequential addition of primary antibodies. Coronal brain sections (50 µm) were washed several times in PB 0.1M (pH=7.4), reacted with 1% H2O2 in 0.1 M PB solution for 15 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase activity and pre-incubated with Triton X-100 for 30 min. Sections were then washed several times and blocked with 2% normal goat serum and incubated with chicken anti-GFP (1:8000, 4°C, 48h; ABCAM). After, sections were extensively washed and incubated with biotinylated donkey anti-chicken secondary antibody (1:500, 2.5 hours RT, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). After washing, sections were incubated in ABC, washed and immunoreactivity was visualized using diaminobenzidene (DAB). Sections were then washed extensively and incubated with rabbit anti-cfos (1:20,000 at 4°C for 48h; Oncogene). Following several washes, sections were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:500 2.5 hr, room temperature (RT), Vector Laboratories), then washed again and incubated in avidin-biotin complex (Vectastain, ABC elite kit, Vector laboratories) for 90 minutes at RT. Immuno-reactivity for c-fos was visualized with nickel diaminobenzidine (Ni-DAB) reaction for 5 minutes or until desired staining. This approach visualized nuclear c-fos as a black precipitate and NPY-GFP neurons as brown cytoplasmic staining, allowing for easy identification and quantification of NPY/cfos cells. Sections were then mounted and cover slipped with Depex mounting medium. Unbiased stereology methods were used to quantify NPY/cfos immunoreactive cells in the ARC. Cells were visualized by a Zeiss microscope and relayed via a MicroFibre digital camera to a computer where they were counted using the optical fractionator with the StereoInvestigator software (MicroBrightField, Williston, VT, USA). Two sections, 200 µm apart (−1.50 mm to −1.70 mm from Bregma) were collected through the ARC and all NPY, cfos and NPY/cfos cells were counted, using a 63x oil objective, in grids randomly positioned by the software in the outlined counting area through all optical planes, thus creating a 3 dimensional counting area. Cells were only counted if they touched the inclusion border or did not touch the exclusion border of the sampling grid. Data are reported as the relative number of double stained cells (c-fos positive and GFP positive) divided by the total number of GFP positive cells.

Immunohistochemistry for POMC

In these studies, adult male mice on a mixed background (B6.129) were used. Mice were injected with EX-527 or vehicle before the dark cycle (ZT11) and were perfused at ZT17. Mice were deeply anesthetized and the left ventricle of the heart was rapidly cannulated and flushed with 0.9% saline containing heparin followed by freshly prepared fixative (paraformaldehyde 4%, gluteraldehyde 0.1%, picric acid 15%, in PB 0.1M, pH=7.4). Usually, the time between opening the thoracic cavity and the heart cannulation was less than 30 seconds. Brains were then dissected out and post-fixed overnight in fixative without gluteraldehyde. After vigorous washing in cold phosphate buffer, 0.1M (PB), vibratome sections were cut (40–60µm) containing the ARC of the hypothalamus. Sections were washed in PB several times, cryo-protected and subsequently frozen and thawed 3 times in liquid nitrogen. After extensive washing in PB, slices were incubated with H2O2 (1%, 20 minutes, RT, shaking) to block endogenous peroxidase activity. After washing again with PB, sections were incubated with primary antibody (anti-POMC, 1:4000, 48 hours, 4°C, gentle shaking). Sections were extensively washed, incubated with secondary antibody (2 hours, RT), washed again, put in ABC and developed with DAB. Sections were then osmicated (15 min in 1% osmium tetroxide in PB) and dehydrated in increasing ethanol concentrations. During the dehydration, 1% uranyl acetate was added to the 70% ethanol to enhance ultrastructural membrane contrast. Dehydration was followed by flat embedding in Durcupan. Ultrathin sections were cut on a Leica ultra microtome, collected on Formvar-coated single-slot grids, and analyzed with a Tecnai 12 Biotwin (FEI) electron microscope. All investigators were blinded to the experimental groups during the entire procedure.

Quantitative synaptology and mitochondria counting

The analysis of synapse number was performed in an unbiased manner (Cowley et al., 2001; Gao et al., 2007) and is presented as number of synapses per 100 µm of cell membrane. For mitochondrial counting, random sections containing POMC cells with a visible nucleus were analyzed. Mitochondria were counted in the POMC cells and the trans-sectional area of each mitochondrion was measured. The data are expressed as number of mitochondria per cell area (in µm2) or total mitochondria trans-sectional area (µm2) per cell area (µm2). Therefore, the ratio of the total mitochondria area divided by the cell area can give a very good estimation of the percentage of the cell body occupied by mitochondria. Additionally, the trans-sectional area of each mitochondrion counted and their circularity were measured as indexes of mitochondria morphology. Macnification 1.6 and MatLab R2009a were used for analysis.

Electrophysiology

Four week old POMC-GFP male mice were kept in a room with an inverted light/dark cycle (lights on from 8:00PM-8:00AM) for at least 2 weeks before electrophysiological recordings. Mice were killed at the beginning of the dark cycle, and the ARC was sliced into 250µm slices (2/mouse), containing the POMC-GFP cells. Slices were then incubated with vehicle or EX-527 at 35°C for 4 hours before cells were transferred to recording chambers. For NPY-GFP cell recording, 4–7 week old male NPY-GFP mice were killed at the beginning of the light phase and the ARC was cut into 250 µm slices (2/mouse), containing NPY-GFP cells. After stabilization in ACSF, slices were transferred to the recording chamber and perfused with ACSF plus vehicle or EX-527. For ghrelin-induced cell activation, the basal firing rate was recorded for at least 10 minutes. The slice was then incubated with ghrelin (0.05 µM) for 8–10 minutes, followed by a washout (with no ghrelin). Either vehicle or EX-527 (50 µM) was kept in the bath solution during the entire recording period.

Six week old Agrp-Sirt1 KO-GFP and control-GFP mice were fasted overnight and killed at the beginning of the light cycle. Whole-cell current-clamp recording was performed using low-resistance (3–4 MΩ) pipettes. The composition of the pipette solution was as follows (in mM): K-gluconate125, MgCl2 2, HEPES 10, EGTA 1.1, Mg-ATP 4, and Na2-phosphocreatin 10, Na2-GTP 0.5, pH 7.3 with KOH. The composition of the bath solution was as follows (in mM): NaCl 124, KCl 3, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2, NaH2PO4 1.23, glucose 2.5, sucrose 7.5, NaHCO3 26. After a gigaohm (GΩ) seal and whole cell access were achieved, membrane potential and action potentials were recorded under current clamp at 0 pA. Ghrelin (0.05 µM) was applied to the bath solution and perfused to the slice. All data were sampled at 3–10 kHz and filtered at 1–3 kHz with an Apple Macintosh computer using Axograph 4.9 (Axon Instruments). Electrophysiological data were analyzed with Axograph 4.9 and plotted with KaleidaGraph 3.6 (Synergy Software) and Igor Pro 5.04 (WaveMetrics Inc.). Membrane potential and action potentials were detected and measured with an algorithm in Axograph 4.9. The frequency of action potential and membrane potential were expressed as mean ± SEM.

Statistical analysis

We used software packages to analyze the data (Matlab R2009a and PASW Statistics 18.0) and plot the figures. First, we tested the homogeneity of variance across the different experimental conditions using Levene’s or Barlett’s test.

When the p value was greater than 0.05 in these tests, homogeneity was assumed, and a parametric analysis of variance test was used. The student’s t test was used to compare two groups. One-, two-, or three-way ANOVA were used as the other tests unless stated otherwise. Multiple comparisons were performed as described below. For repeated measures analysis we used a mixed model ANOVA with time as a “within-subject repeated-measures” factor and treatments/genotype as a “between subject” factor. Significant effects were followed with Fisher’s PLSD post-hoc test with Bonferroni’s correction. When homogeneity was not assumed, the Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric ANOVA was used and the Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine post-hoc significant of differences between groups. Fisher’s exact test was used to find differences in the number of cells activated by ghrelin in the electrophysiology recordings. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data are showed as mean ± SEM unless stated otherwise.

Results

Sirt1 inhibition decreases the excitability of NPY/Agrp neurons

Negative energy balance is supported by the activity of ARC NPY/Agrp neurons. To test whether sirtuin action affects NPY/Agrp neurons, we evaluated whether Sirt1 inhibition changes the excitability of these cells. First, we measured the membrane potential of NPY/Agrp neurons in acute slices from 4–7 week old male NPY-GFP mice. After an initial stabilization of the slices in ACSF, they were incubated in EX-527 (50 µM) for at least 30 minutes followed by a washout with ACSF (containing vehicle). We found that Sirt1 inhibition by EX-527 hyperpolarized the neuronal membrane potential of NPY neurons (vehicle = −49.12 ± 1.40; EX-527 = −51.74 ± 1.53; Δ = −2.61±0.56 mV; n = 4 cells/4 mice, t3 = 4.66, p < 0.05 – See Supplemental Figure 1), while decreasing the firing rate of these cells (vehicle = 100 ± 31%; EX−527 = 46.6 ± 10.8%; n = 4 cells/4 mice; t3 = 4.20, p < 0.05), indicating a decreased excitability of these neurons.

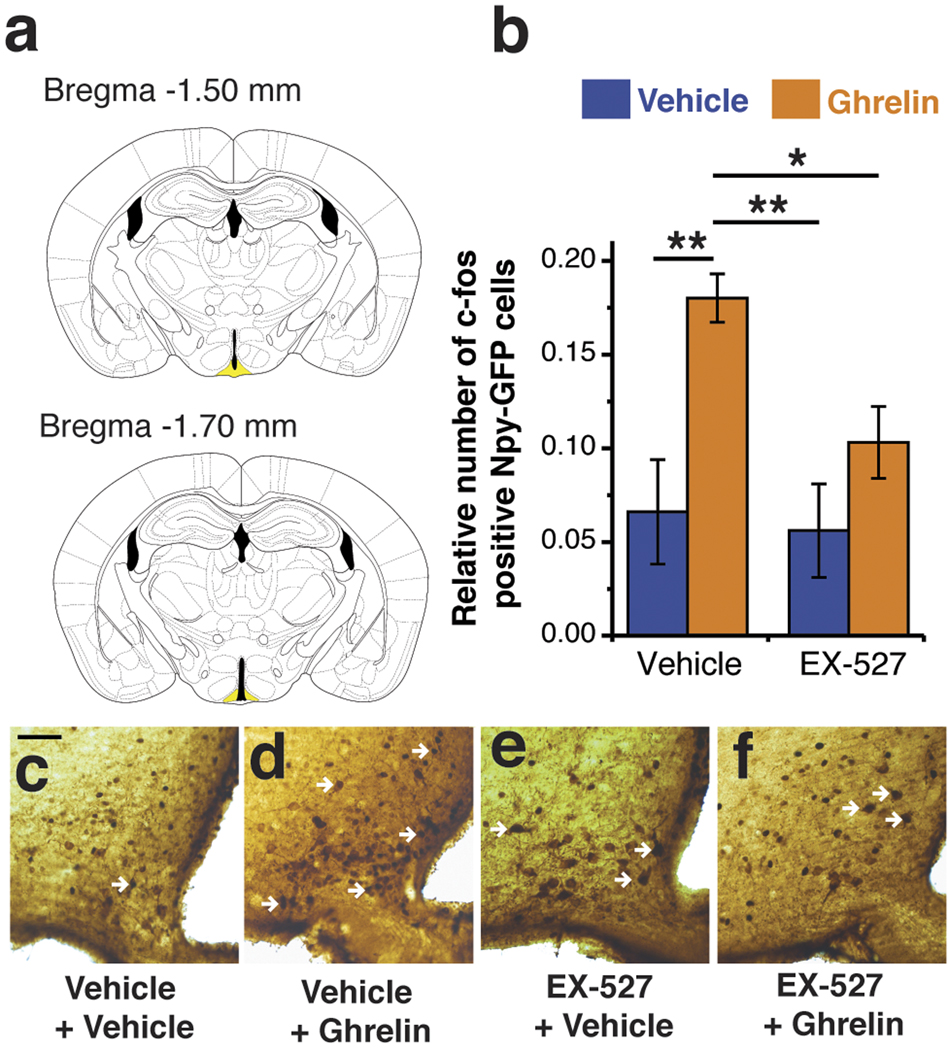

Next, we sought to determine if Sirt1 inhibition could also impair the activation of NPY/Agrp neurons induced by ghrelin, a hormone that is elevated during negative energy balance. We found that the pre-treatment of slices with EX-527 (50 µM) for 30 min impairs the ghrelin-induced NPY/Agrp cell activation: in the vehicle group, 13 out of 14 cells (7 mice) were activated by ghrelin, whereas only 1 out of 4 cells (4 mice) were activated in the EX-527 treated group (p < 0.05, Fisher’s exact test). To understand if our findings in slice preparation could translate to in vivo activation of NPY-GFP cells, we injected mice with EX-527 (i.c.v., 1.5 nmol, 3 µl, according to dose-response below) 30 min before injecting ghrelin (i.p., 1µg/g body weight). As shown in Figure 1, ghrelin induced the activation of NPY-GFP cells as measured by the number of NPY-GFP neurons that co-expressed c-fos in their nuclei (ANOVA: F3,15 = 6.79, p < 0.01; 179 ± 8.33% compared to vehicle control, post hoc test p < 0.01). EX-527 per se did not change the ratio of c-fos/NPY-GFP cells, but significantly attenuated the activation of NPY-GFP neurons by ghrelin (61 ± 16.38 % compared to ghrelin control, post hoc test p < 0.05).

Figure 1. Sirt1 inhibition decreases ghrelin-induced c-fos expression in NPY/Agrp neurons.

EX-527 (i.c.v., 1.5 nmol/mouse), a pharmacological inhibitor of Sirt1 (Napper et al., 2005; Pacholec et al., 2010), diminished the number of c-fos labeled NPY-GFP cells after ghrelin treatment (i.p.). (a) slices from the brain highlighting the arcuate nucleus (ARC; in yellow) where the NPY-GFP and c-fos cells were counted (between bregma −1.50 mm to −1.70 mm). (b) Histogram showing quantification of double labeled NPY-GFP/c-fos cells in the ARC of mice injected with vehicle/EX-527 and vehicle/ghrelin. (c–e) Representative pictures of double immunohistochemistry for GFP (DAB - brown) and c-fos (Nickel DAB – black). White arrows indicate double stained cells. n = 4–5 mice/group. * p <0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Sirt1 inhibition affects synaptic input organization of hypothalamic POMC neurons

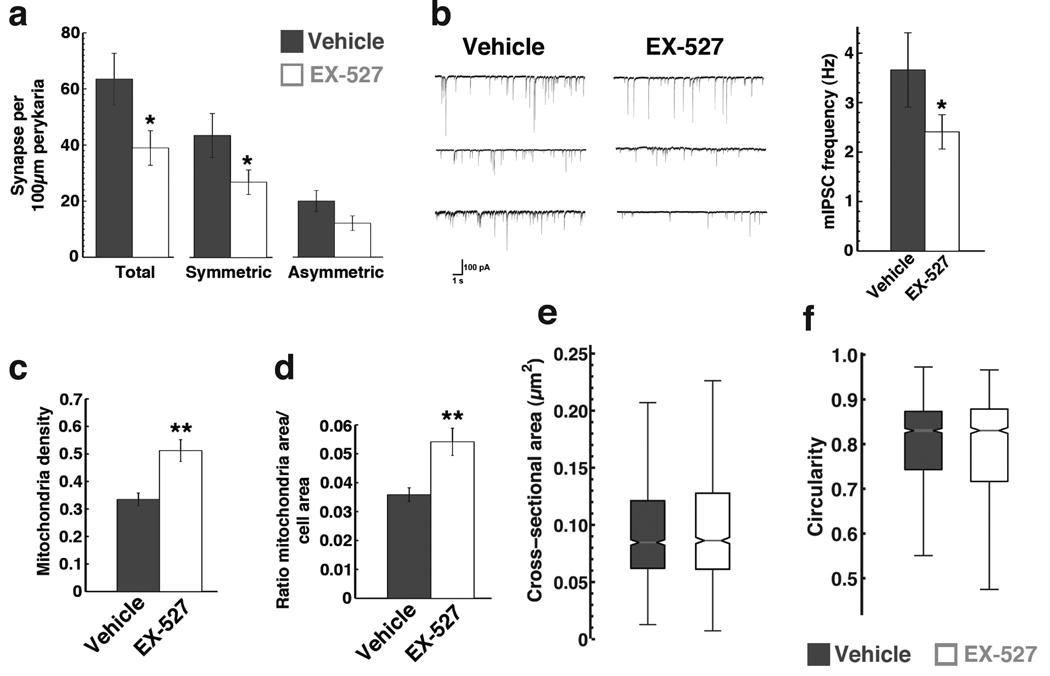

A major efferent projection exists from the Agrp neurons to their neighboring POMC cells, which is an inhibitory, GABAergic projection – See Supplemental Figure 2. Thus, next we studied the effects of EX-527 administered directly into the brain on the synaptic input organization of the POMC neurons in the ARC. Adult male wild type mice were treated with EX-527 (i.c.v., 1.5 nmol) 30–60 minutes before the dark cycle and were sacrificed 4 hours later to analyze synapses on POMC neurons (by electron microscopy). We found that EX-527 blocked the recruitment of synapses onto POMC perikarya (vehicle = 63.4 ± 9.2, EX-527 = 38.9 ± 6.1 synapses per 100 µm perikarya; Mann-Whitney U = 83.00, p < 0.05), which was predominantly the result of a decreased number of symmetric synapses (putatively inhibitory – vehicle = 43.4 ± 7.8, EX-527 = 26.8 ± 4.3 synapses per 100 µm perikarya; Mann-Whitney U = 87.00, p < 0.05) but not asymmetric synapses (putatively excitatory – vehicle = 20.0 ± 3.7, EX-527 = 12.1 ± 2.6 synapses per 100 µm perikarya ) during the first 4 hours of the dark cycle - Fig.2a - See Supplemental Figure 3. An elevated number of inhibitory synapses on POMC neurons in the vehicle control group is consistent with a synaptic arrangement that promotes the suppressed activity of these satiety-signaling cells at the time of increased feeding. To confirm that Sirt1 inhibition blocks the recruitment of inhibitory synapses onto POMC neurons, we also analyzed POMC-GFP cells from acute slices using whole cell patch electrophysiological recording after incubation with Sirt1 inhibitor (EX-527, 50 µM, 4 h). In corroboration of the morphological data, we found that Sirt1 inhibition blocked the increase in the frequency of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) of the POMC-GFP cells (vehicle = 3.6 ± 0.7, EX-527 = 2.4 ± 0.3 Hz; n = 12 cells/4 mice/group; t12 = 1.99, p < 0.05 (1-tail) - Fig.2b).

Figure 2. Sirt1 inhibition affects synaptic inputs and mitochondrial number in POMC neurons in the hypothalamus.

In (a), EX-527 (i.c.v.) was administered to wild type adult mice at the beginning of the dark cycle and synaptic inputs were measured on POMC neurons 4 hours later. EX-527 decreased the recruitment of inputs onto POMC neurons, mainly affecting symmetric, putatively inhibitory, inputs, and not asymmetric, putatively excitatory synapses. (Data are mean ± s.e.m., n = 15–21 cells). (b) Electrophysiological recordings showing decreased frequency of mIPSCs in POMC-GFP neurons treated with EX-527 (mean ± s.e.m., n = 12 cells). (c–f) Sirt1 inhibition by EX-527 affects mitochondrial density in POMC neurons. Sirt1 inhibition increased mitochondrial density (c) and relative area (d) in POMC cells (mean ± s.e.m., n = 13–20 cells), without affecting indexes of mitochondrial morphology, specifically the cross-sectional mitochondrial area (e) and circularity (f) (data are median ± interquartile range, n > 500). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Sirt1 inhibition increases mitochondrial density in POMC neurons of the hypothalamus

Since decreased inhibition of POMC neurons leads to increased melanocortin tone, an adaptation of the mitochondria machinery in these cells may be expected. Indeed, both mitochondrial density (vehicle = 0.33 ± 0.02, EX-527 = 0.51 ± 0.04 mitochondria per cell area; t31 = 3.34, p < 0.01 - Fig. 2c) and area (vehicle = 0.035 ± 0.002, EX-527 = 0.054 ± 0.005 ∑mitochondria area per cell area; t31 = 2.96, p < 0.01 - Fig. 2d) were increased in POMC cells after Sirt1 inhibition, an event consistent with increased activity of these cells. However, no changes in mitochondrial morphology were observed as evidenced by the distribution of the cross-sectional area of each mitochondria - Fig. 2e - and their circularity - Fig. 2f. Taken together, these data suggest that Sirt1 contributes to the appropriate synaptic and mitochondrial adaptations of the melanocortin system in response to negative energy balance.

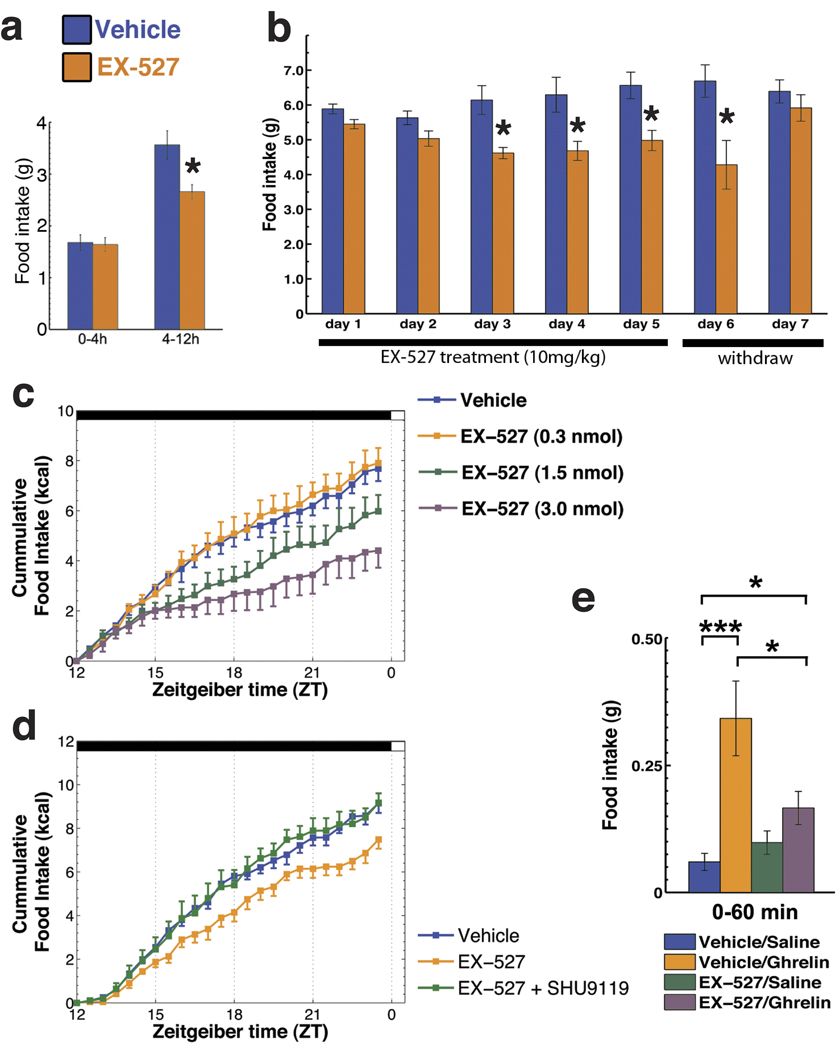

Brain Sirt1 inhibition decreases food intake

Our results indicate an acute effect of Sirt1 inhibition on the organization and activity of the melanocortin system in the ARC of the hypothalamus. Because the NPY/Agrp and POMC neurons are the core of the melanocortin system and are implicated in the regulation of food intake, we sought to determine if the effects we found in the morphological and electrophysiological adaptations due to Sirt1 inhibition could affect food intake. To this end, we first analyzed the effects of peripheral injection of EX-527 on food intake. EX-527 (i.p., 10 mg/kg) inhibited food intake during the dark phase (interaction time × treatment F1,8 = 9.33, p < 0.05 - Fig. 3a), a period of the circadian cycle during which orexigenic stimuli predominate in nocturnal animals. To further evaluate the acute effects of Sirt1 inhibition in the modulation of food intake, we injected EX-527 (10 mg/kg) daily to adult wild type mice and measured food intake. In agreement with our acute data, daily peripheral injection of EX-527 given just before the dark cycle induced a robust and consistent decrease in food intake, which persisted until the day after cessation of the treatment (treatment F1,6 = 24.53, p < 0.05; time × treatment F1,6 = 2.38, p < 0.05 - Fig. 3b). In the first 2 days, 24 hour food intake was not significantly different. When analyzed closely, it was apparent that EX-527 reduced overnight food intake (e.g., day 1: vehicle = 4.85 ± 0.26, EX-527 = 3.83 ± 0.21 g; t6 = 3.06, p < 0.05), without statistical differences in food intake during the light phase (vehicle = 1.04 ± 0.14, EX-527 = 1.61 ± 0.20). On the remaining days (e.g. day 5), EX-527 continued to reduce overnight food intake (vehicle = 5.98 ± 0.50, EX-527 = 4.45 ± 0.28; t6 = 2.67, p < 0.05) without causing rebound feeding during the light cycle (vehicle = 0.59 ± 0.17, EX-527 = 0.54 ± 0.07).

Figure 3. Inhibition of Sirt1 decreases food intake.

(a) Peripheral injection of a specific Sirt1 inhibitor, EX-527 (10 mg/kg), decreased the overnight food intake with no effect in the first 4-hours (mean ± s.e.m., n = 5). (b) Daily injection of EX-527 (10 mg/kg) just before the dark cycle produces a robust and consistent decrease in food intake (mean ± s.e.m., n = 4). (c) Injection of EX-527 into the cerebral ventricles also inhibited food intake in a dose dependent manner during the dark cycle (mean ± s.e.m., n = 4–7). (d) SHU9119 (140 pmol, i.c.v.), a potent melanocortin receptor antagonist, counteracted the inhibitory effect of EX-527 on food intake (mean ± s.e.m., n= 4–6) highlighting the importance of downstream melanocortin signaling as an effector of Sirt1 inhibition on food intake. (e) Brain Sirt1 inhibition by EX-527 (i.c.v.) blunted the orexigenic effect of the gut hormone ghrelin, which depends on redox adaptations in the NPY/Agrp neurons (Andrews et al., 2008) (mean ± s.e.m., n = 7–13 mice). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Scale bars = 50 µm.

Next, we injected EX-527 directly into the cerebral ventricles to evaluate if the effects we found were due to inhibition of brain Sirt1 activity. Indeed, EX-527 injected directly into the cerebral ventricles also inhibited food intake in a dose dependent manner (effect of time: F23,527 = 228.39, p < 0.001; effect of treatment: F3,527 = 4.36, p < 0.05; interaction time × treatment: F69,527 = 4.28, p < 0.001 - Fig.3c). We then repeated these experiments using conditions similar to the peripherally administered EX-527 experiment - Fig. 3a - injecting the intermediate dose of EX-527 (i.c.v., 1.5 nmol), and found that it inhibited food intake in a comparable manner to the peripheral treatment - Supplemental Figure 5. To further evaluate the effects of central inhibition of Sirt1, we injected mice with EX-527 (i.c.v., 1.5 nmol) and simultaneously monitored food consumption, water intake and ambulatory activity - Supplemental Figure 6. The data obtained on food intake corroborated our previous findings, while no statistical differences in water intake were found. Finally, treatment with central EX-527 did not statistically change the ambulatory activity of mice - Supplemental Figure 6. Additionally, no overt side effects were observed by central EX-527 treatment - Supplemental Table 1. In addition to EX-527, we also found similar results with peripheral and central administration of nicotinamide (data not shown), a natural end product of Sirt1 deacetylase activity, which inhibits Sirt1 in a stoichiometric manner. Taken together, these data suggest that Sirt1 coordinates neuronal circuit adaptation to negative energy balance to modulate food intake.

To further evaluate the relevance of the melanocortin system in the inhibition of Sirt1 on feeding, we analyzed the effect of the melanocortin 4-receptor antagonist, SHU9119, on EX-527’s effect on food intake. SHU9119 was able to reverse the inhibition of food intake promoted by EX-527 (effect of time: F23, 276 = 495.75, p < 0.001; effect of treatment: F2,12 = 4.15, p < 0.05; interaction time × treatment: F46,276 = 2.74, p < 0.001; post hoc: vehicle × EX-527, p < 0.05; EX-527 × EX-527+SHU9119, p < 0.05 – Fig. 3d), indicating that the effect of Sirt1 inhibition on food intake uses the melanocortin receptors as a downstream effector. In the dose used in this study, we found no changes in food intake when SHU9119 was injected alone (data not shown). These data are in agreement with the results of a recent study (Cakir et al., 2009).

If Sirt1 is intrinsically important for the excitability of NPY/Agrp neurons, then signals that are known to affect food intake via these hypothalamic neurons should have an altered effect on eating when applied concomitantly with the Sirt1 inhibitor, EX-527. Ghrelin affects feeding by activation of the NPY/Agrp neurons. Thus, we injected wild type mice with ghrelin (30 µg/mouse, i.p.) to induce food intake during the light phase of the circadian cycle, and pre-treated the mice with EX-527 (i.c.v., 1.5 nmol, 30–60 min before ghrelin). Feeding induced by the injection of ghrelin (574 ± 21 % compared to vehicle control; Mann-Whitney U = 0.00, p < 0.001) was reversed by pretreatment with the Sirt1 inhibitor EX-527 (52 ± 10 % inhibition compared to vehicle plus ghrelin; Mann-Whitney U = 99.50, p < 0.05), but did not alter normal feeding in vehicle-treated mice - Fig. 3e.

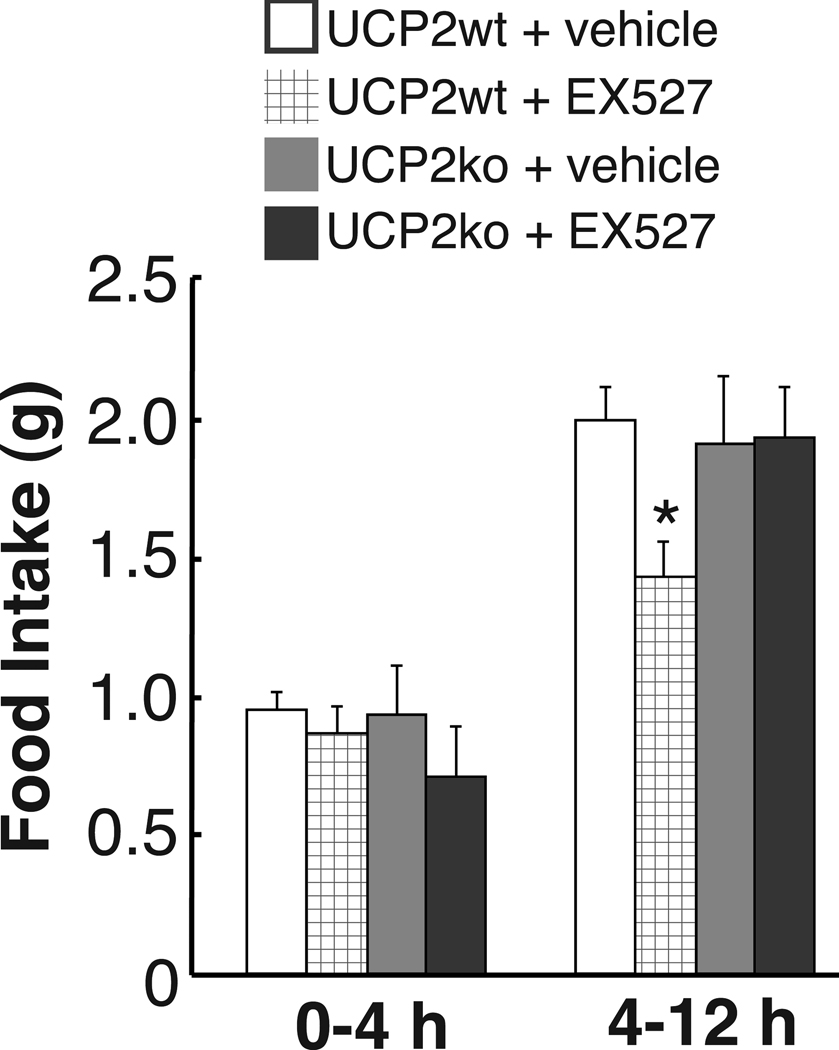

The effects of brain Sirt1 inhibition are dependent upon UCP2

Next, we evaluated whether the effects of Sirt1 inhibition on food intake may be altered in mice with an impaired mitochondrial redox adaptation (UCP2 KO mice). The Sirt1 inhibition by any of the three doses of EX-527 used above (data shown for i.c.v., 1.5 nmol dose) failed to show effects in UCP2 KO mice while it suppressed feeding in wild type animals (effect of time F1, 31 = 71.43, p < 0.001; effect of treatment F1, 31 = 9.22, p < 0.01; interaction time × treatment × genotype F1, 31 = 4.80, p < 0.05 - Fig.4). EX-527 also failed to block recruitment of inhibitory synapses onto POMC neurons (total: vehicle = 43.68 ± 5.21, EX-527 = 35.04 ± 5.43; symmetric: vehicle = 28.67 ± 3.89, EX-527 = 27.31 ± 3.64; asymmetric: vehicle = 15.01 ± 2.95, EX-527 = 7.72 ± 2.78 synapses per 100 µm perikarya) or increase mitochondrial density (vehicle = 0.57 ± 0.05, EX-527 = 0.53 ± 0.06 mitochondria per cell area) or area (vehicle = 0.050 ± 0.004, EX-527 = 0.049 ± 0.005 ∑mitochondria area per cell area) nor did it change any of the indexes of mitochondria morphology (data not shown) in these cells during negative energy balance.

Figure 4. The effect of Sirt1 inhibition on food intake is UCP2 dependent.

Inhibition of brain Sirt1 by EX-527 (30–60 min before dark cycle, 1.5 nmol, i.c.v.) decreased food intake during the dark cycle in wild type mice, but not in UCP2 KO mice (mean ± s.e.m., n = 5–12). * p < 0.05.

Sirt1 knockdown in Agrp neurons results in decreased feeding and lower body weight

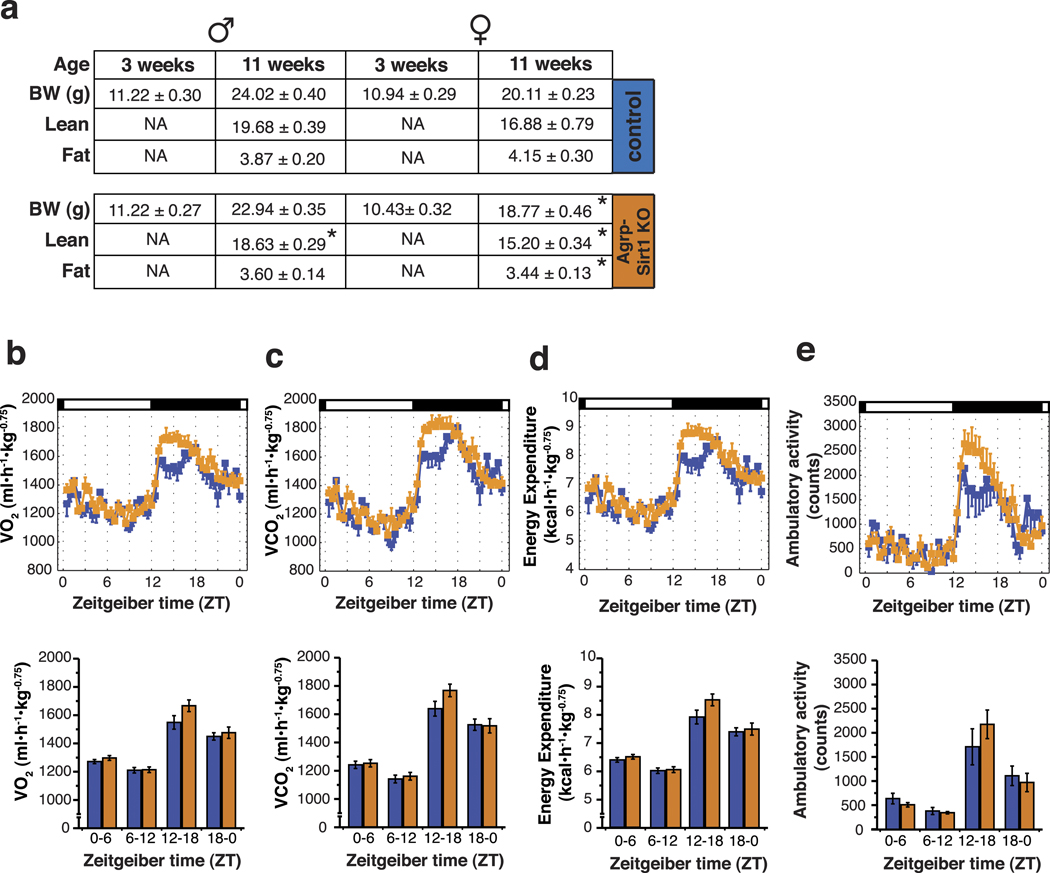

When weaned at 21-days of age, Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice showed no gross abnormalities and both males and females had similar body weight compared to their control littermates – Fig.5a. However, over time the Agrp-Sirt1 KO gained less weight compared to their control littermates, and at 11 weeks, both males and females were leaner than controls - Fig.5a. Next, we analyzed the body composition of these transgenic mice utilizing DEXA scanning to estimate lean and fat tissue weight. As presented in Figure 5a, females showed a more marked phenotype with reductions in both lean and fat tissue weights, while male Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice showed a consistent reduction in just lean, but not fat mass – Fig.5a.

Figure 5. Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice have decreased food intake without concomitant adaptation in energy expenditure.

(a) Table showing the body weight at weaning and at 11 weeks old in male and female control and Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice. The KO mice gained less weight compared to controls, which was due mostly to decreased lean mass. Female Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice also showed a diminished fat tissue mass (mean ± s.e.m., data in grams). (b–d) Data from metabolic chambers showing VO2, VCO2 and energy expenditure, respectively, adjusted for body mass (kg−0.75). There were no statistical differences at any of the time points analyzed. In (e), data on ambulatory activity of the same mice in the metabolic chambers showing no statistical differences (mean ± s.e.m., n = 4–7). * p < 0.05.

Due to the more distinct phenotype of the females, we decided to characterize the metabolic parameters of these mice in metabolic chambers. Coinciding with a decreased body weight, female Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice exhibited a marked reduction in food intake compared to controls (control = 39.85 ± 2.88, KO = 33.91 ± 0.86 kcal/72 h; t9 = 2.48, p < 0.05), which was mostly due to decreased nocturnal, and not residual diurnal food intake (data not shown). Surprisingly, over the same period of time, there was no difference in energy expenditure between control and Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice (control = 27.94 ± 1.26, KO = 26.18 ± 0.68 kcal/72 h). Upon estimation of a relative energy balance (food intake in kcal minus energy expenditure in kcal) for these mice, we found that Agrp-Sirt1 KO animals exhibited a reduced positive energy balance in relation to their littermate controls (control = 11.91 ± 1.83, KO = 7.73 ± 0.088 kcal/72 h; t9 = 2.33, p < 0.05), indicating a dys-regulation in energy balance in which decreased food intake is not associated with decreased energy expenditure.

We further analyzed the daily metabolism of the Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice by indirect calorimetry, estimating their oxygen consumption (VO2), VCO2, energy expenditure and locomotor activity. We were unable to find statistical differences in any of these parameters - Fig.5b–e. We also estimated the respiratory quotient (VCO2/VO2), and found no differences between control and Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice (data not shown).

Altogether, these data indicate that the knockdown of Sirt1 in the NPY/Agrp neurons promotes a decrease in food intake that is not accompanied by a concomitant change in energy expenditure. Moreover, these transgenic mice (Agrp-Sirt1 KO) did not display any gross alteration in any of the metabolic parameters analyzed when fed an ad libitum diet.

Agrp-Sirt1 knockout cells have diminished response to ghrelin

Our observations highlighted an important role of Sirt1 in the NPY/Agrp neuronal regulation of overall metabolism, mainly because the KO mice showed a marked decrease in food intake and body weight gain, which was not associated with reductions in energy expenditure. In an attempt to further understand the physiology of these mutant animals, we bred our Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice with NPY-GFP mice to generate animals that expressed GFP in the NPY/Agrp cells (See material and methods and Supplemental Figure 7 for details). In 6–7 week old control-GFP and Agrp-Sirt1 KO-GFP mice, utilizing whole cell current clamp recordings, we were able to register the membrane potential and firing rate of the NPY/Agrp neurons.

We administered ghrelin in the incubation chamber to induce NPY/Agrp cell activation and compared the effects in the control and Sirt1 KO cells. In the control-GFP cells, we were able to replicate the effect of ghrelin to increase the excitability of the NPY/Agrp neurons as measured by both a decrease in the membrane potential (vehicle = −52.19 ± 2.92, ghrelin = −41.40 ± 1.14 mV; n = 6 cells/6 mice; t5 = 3.26, p < 0.05) and an increase in the firing rate of these cells (vehicle = 1.84 ± 0.65, ghrelin = 5.37 ± 1.18 Hz; n = 6 cells/6 mice/group; t5 = 4.60, p < 0.01). In contrast to this, the Agrp-Sirt1 KO-GFP neurons incubated with ghrelin showed no statistical difference in either the membrane potential (vehicle = −46.62 ± 4.61, ghrelin = −40.99 ± 2.63 mV; n = 6 cells/6 mice) or firing rate (vehicle = 2.55 ± 0.62, ghrelin = 2.46 ± 0.49 Hz; n = 6 cells/6 mice). Finally, 100% of the recorded neurons in the control group responded to ghrelin, while only 16% of the cells responded in the Sirt1 KO group (p < 0.01, Fisher’s exact test).

Sirt1 knockdown in Agrp neurons results in impaired responses to fasting

Because NPY/Agrp neurons play an important role in transitioning to negative energy balance, and their excitability was impaired in Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice, we postulated that challenging these mice with food deprivation could exacerbate their phenotype. Thus, we repeated the experiments in the metabolic chambers using identical conditions as before, however we challenged the mice by fasting them 2h before the dark cycle and evaluating their response during ZT 12–18 with no food available. Strikingly, the Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice showed a marked increase in ambulatory activity compared to control mice (control = 1954 ± 65, KO = 3115 ± 336 counts; t9 = 2.53, p < 0.05), which was concurrent with increased oxygen consumption (VO2, control = 1552 ± 37, KO = 1783 ± 64 ml.h−1.kg−0.75; t9 = 2.54, p < 0.05), with no differences in energy expenditure when adjusted for body weight (control = 7.78 ± 0.23, KO = 8.77 ± 0.31 kcal.h−1.kg−0.75) or cumulative energy expenditure (control = 2.49 ± 0.04, KO = 2.53 ± 0.08 kcal/6h).

Discussion

We describe the effects of brain Sirt1 inhibition on NPY/Agrp neuronal excitability and on the synaptic and mitochondrial adaptations of POMC neurons in the ARC of the hypothalamus. Sirt1 inhibition reduced NPY/Agrp neuronal firing and the synaptic input onto the POMC neurons, mainly due to a decrease in the number of inhibitory inputs on these cells. This observation is in agreement with the finding of an increase in mitochondrial density, signifying an enhanced activity of POMC cells following brain Sirt1 inhibition. We also found that Sirt1 inhibition decreased food intake during the dark cycle and ghrelin-induced food intake in wild type mice. The decrease in food intake induced by Sirt1 inhibition was reversed by a melanocortin receptor antagonist, indicating the melanocortin hypothalamic system in the behavioral effects caused by Sirt1 inhibition. The behavioral and physiological effects of inhibition of Sirt1 were not observed in UCP2 KO mice, indicating a role of redox mechanisms involving UCP2 in Sirt1 effects.

Evidence for specificity of brain Sirt1 pharmacological inhibition

In the first set of experiments, we pharmacologically inhibited Sirt1 activity by EX-527, a specific Sirt1 inhibitor. Several lines of evidence support the idea that the effects seen in our experiments were due to Sirt1 inhibition and not due to side-effects of EX-527: (1) Sirt1 inhibition decreased food intake in a time-delayed manner only during the dark cycle and not during the light cycle (Fig. 3e); (2) Sirt1 inhibition did not decrease food intake in UCP2 KO mice (Fig. 4); Sirt1 inhibition did not change symmetric synaptic and mitochondria number in UCP2 KO mice; and (4) Sirt1 inhibition had no effect on water intake and locomotor activity. Also, we have shown that EX-527 increases acetylated forms of Sirt1 target proteins and that this effect is dependent on Sirt1 expression (Nie et al., 2009). Finally, we have also tested the effect of EX-527 on a cell line that resembles the phenotype of NPY/Agrp neurons (N-39), and found an increase in the acetylated levels of Sirt1 target proteins as well (data not shown). However, while we have tested mice injected with central EX-527 acutely in several tests to exclude possible side effects of this compound on feeding, we have not tested for side-effects after chronic treatment (Fig. 3b).

Participation of the melanocortin system in the effects of brain Sirt1

In mammals, the melanocortin system is central to appetite regulation (Cone, 2006). Negative energy balance, which can be induced by fasting, calorie restriction, or hormones that are active during these situations (e.g., ghrelin) (Ravussin et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2003) promotes the activity of NPY/Agrp neurons over POMC neurons in the ARC (Hahn et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2004). Several lines of evidence suggest the involvement of Sirt1 in the functioning of the melanocortin system in the ARC. First, Sirt1 is expressed in the ARC and its levels/activity are sensitive to negative energy balance (Ramadori et al., 2008). Recently, it was reported that Sirt1 regulates food intake in rats through the melanocortin system: inhibition of melanocortin receptor signaling by an antagonist reversed the decrease in food intake by a Sirt1 antagonist (Cakir et al., 2009). These data have been replicated in mice in the present study (Fig. 3d). A significant component of the effect of inhibition of Sirt1 on feeding was mediated by the melanocortin system: inhibition of MC4R reversed the effect of EX-527. It is important to note, however, that the overall effect of Sirt1 inhibition on feeding was not similar to acute interference with MC4R signaling. Both activation and inactivation of MC4R bring about acute changes in feeding (Cone, 2006; Wallingford et al., 2009). On the other hand, an acute inhibition of Sirt1 (present data) leads to alterations in feeding in a relatively delayed manner. We further investigated the mechanisms implicated in the role of Sirt1 in the regulation of energy metabolism, and found evidence that Sirt1 is important for the synaptic and mitochondrial plasticity that occurs in the melanocortin system. Specifically, pharmacological inhibition of Sirt1 decreases the inhibitory, but not excitatory inputs on POMC cells. The effects of Sirt1 inhibition on the synaptic plasticity of POMC neurons was consistent with the food intake data, because it relies on a mechanism that was previously proposed to have an enabling rather than an acute influence on neuronal firing (Pinto et al., 2004; Gao et al., 2007; Andrews et al., 2008). On the other hand, Sirt1 appears to be important for the maintenance of proper cellular machinery that allows the NPY/Agrp neurons to respond to acute ghrelin administration.

Participation of the redox state on the effects of Sirt1

The effect of ghrelin on the hypothalamic melanocortin system is well-established. Ghrelin promotes feeding through the activation of NPY/Agrp neurons and inhibition of POMC cells, with a consequent inhibition of MC4R in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) (Tschöp et al., 2001; Tschöp et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2004; Shaw et al., 2005). We showed that ghrelin activates mitochondria respiration and proliferation in NPY/Agrp neurons that are critical for the increase in electrical activity and subsequent increases in food intake (Andrews et al., 2008). The acute feeding response to ghrelin as well as the synaptic plasticity and mitochondrial adaptation in the hypothalamus (Coppola et al., 2007; Andrews et al., 2008) and hippocampus (Dietrich et al., 2008) rely on UCP2-regulated shifts in oxidative processes. Intriguingly, oxidative conditions (in contrast to reducing conditions) have been shown to upregulate Sirt1 activity in neurons (Prozorovski et al., 2008). The present results indicate that Sirt1 participates in the signaling involved in feeding, linking the redox state of the hypothalamic melanocortin system to the activity of Sirt1 and its participation in the mechanisms of synaptic and mitochondrial plasticity. This assumption is reinforced by the facts that Sirt1 inhibition (i) reversed the orexigenic effects of ghrelin (Fig. 3e) and (ii) did not decrease feeding UCP2 KO mice (Fig. 4).

Impaired response to food deprivation in Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice

In addition to the pharmacological data, we developed a transgenic mouse model of Sirt1 deficiency in the NPY/Agrp neurons of the hypothalamus that resembles the phenotype of wild type mice after pharmacological Sirt1 inhibition in the brain. These Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice were leaner, had reduced food intake and impaired adaptation of metabolic parameters to decreased energy intake.

Sirt1 has been linked to shifts in metabolism that occur during food deprivation (Rodgers and Puigserver, 2007). During fasted states Sirt1 maintains hepatic gluconeogenesis and fatty acid oxidation (Rodgers and Puigserver, 2007; Nie et al., 2009), and the knockdown of Sirt1 in hepatocytes diminishes beta-oxidation in this tissue (Rodgers and Puigserver, 2007; Purushotham et al., 2009). Our present data are in agreement with the notion that Sirt1 activity contributes to a shifting from positive to negative energy balance, because Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice showed an impaired response to food deprivation by demonstrating increased locomotor activity and oxygen consumption compared to their control littermates.

Additionally, the impaired excitability of the Agrp-Sirt1 KO NPY/Agrp cells in response to ghrelin supports the involvement of Sirt1 in shifting from positive to negative energy balance. The role of Sirt1 in modulating the transition to fatty acid metabolism during periods of negative energy balance (Rodgers and Puigserver, 2007; Purushotham et al., 2009) together with the fact that the Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice had impaired energy balance and adaptation to food deprivation, corroborate our previous data, indicating that beta-oxidation contributes to NPY/Agrp neuronal activation that regulates energy balance (Andrews et al., 2008).

Comparisons between Agrp-specific Sirt1 KO and whole body Sirt1 KO mice

Our results contrast those from previous studies showing that whole body Sirt1 KO mice are hyperphagic (Chen et al., 2005; Pani et al., 2006). However, the data from studies using Sirt1 KO mice are difficult to interpret, because these mice have profound developmental problems, and only a small number of pups reach adulthood (Cheng et al., 2003; McBurney et al., 2003). Once the knockout mice reach adulthood, they gain around 60% more body weight compared to their littermates (Chen et al., 2005). Thus, the hyperphagic behavior of the Sirt1 KO mice is likely caused by complex compensatory developmental mechanisms that have little to do with Sirt1 normal physiological mechanisms in the adult brain. In our studies, we used an acute inhibition of or chronic knockdown of Sirt1 specifically in the Agrp neurons (Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice). In contrast to the whole body Sirt1 KO mice, the Agrp-Sirt1 KO mice were born in Mendelian rates, had no gross developmental problems compared to their littermates, and demonstrated decreased feeding.

Concluding remarks

Our data on hypothalamic neurobiological events indicate that Sirt1 activation in NPY/Agrp neurons is a determinant of their excitability, which consequently, is important for appropriate shifts in behavioral, autonomic and endocrine processes to occur for adaptation to negative energy balance. These findings reveal a novel mechanism by which the selective activation of Sirt1 within the NPY/Agrp neurons promotes negative energy balance that is characteristic of calorie restriction, which promote a longer, healthier lifespan.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Marya Shanabrough for the comments and revisions on the manuscript. MOD and CA were partially supported by CNPq/Brazil. TLH and X-BG were supported by grants from the NIH and ADA. SD was supported by grants from the NIH, ADA and JDRF. DOS was supported by grants FINEP/MCT and INCT for Excitotoxicity and Neuroprotection. QG was supported by a grant from the ADA.

References

- Andrews Z, Liu Z, Walllingford N, Erion D, Borok E, Friedman J, Tschöp M, Shanabrough M, Cline G, Shulman G, Coppola A, Gao X, Horvath T, Diano S. UCP2 mediates ghrelin's action on NPY/AgRP neurons by lowering free radicals. Nature. 2008;454:846–851. doi: 10.1038/nature07181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann C, Sherman J, Devine S, Cameron E, Pillus L, Boeke J. The SIR2 gene family, conserved from bacteria to humans, functions in silencing, cell cycle progression, and chromosome stability. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2888–2902. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.23.2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakir I, Perello M, Lansari O, Messier N, Vaslet C, Nillni E. Hypothalamic Sirt1 regulates food intake in a rodent model system. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Guarente L. SIR2: a potential target for calorie restriction mimetics. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Steele A, Lindquist S, Guarente L. Increase in activity during calorie restriction requires Sirt1. Science. 2005;310:1641. doi: 10.1126/science.1118357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Bruno J, Easlon E, Lin S, Cheng H, Alt F, Guarente L. Tissue-specific regulation of SIRT1 by calorie restriction. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1753–1757. doi: 10.1101/gad.1650608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Trumbauer M, Chen A, Weingarth D, Adams J, Frazier E, Shen Z, Marsh D, Feighner S, Guan X, Ye Z, Nargund R, Smith R, Van der Ploeg L, Howard A, MacNeil D, Qian S. Orexigenic action of peripheral ghrelin is mediated by neuropeptide Y and agouti-related protein. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2607–2612. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Mostoslavsky R, Saito S, Manis J, Gu Y, Patel P, Bronson R, Appella E, Alt F, Chua K. Developmental defects and p53 hyperacetylation in Sir2 homolog (SIRT1)-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10794–10799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934713100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen H, Miller C, Bitterman K, Wall N, Hekking B, Kessler B, Howitz K, Gorospe M, de Cabo R, Sinclair D. Calorie restriction promotes mammalian cell survival by inducing the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;305:390–392. doi: 10.1126/science.1099196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone R. Studies on the physiological functions of the melanocortin system. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:736–749. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola A, Liu Z, Andrews Z, Paradis E, Roy M, Friedman J, Ricquier D, Richard D, Horvath T, Gao X, Diano S. A central thermogenic-like mechanism in feeding regulation: an interplay between arcuate nucleus T3 and UCP2. Cell Metab. 2007;5:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley M, Smart J, Rubinstein M, Cerdán M, Diano S, Horvath T, Cone R, Low M. Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature. 2001;411:480–484. doi: 10.1038/35078085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich M, Andrews Z, Horvath T. Exercise-induced synaptogenesis in the hippocampus is dependent on UCP2-regulated mitochondrial adaptation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10766–10771. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2744-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q, Mezei G, Nie Y, Rao Y, Choi C, Bechmann I, Leranth C, Toran-Allerand D, Priest C, Roberts J, Gao X, Mobbs C, Shulman G, Diano S, Horvath T. Anorectic estrogen mimics leptin's effect on the rewiring of melanocortin cells and Stat3 signaling in obese animals. Nat Med. 2007;13:89–94. doi: 10.1038/nm1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gropp E, Shanabrough M, Borok E, Xu A, Janoschek R, Buch T, Plum L, Balthasar N, Hampel B, Waisman A, Barsh G, Horvath T, Brüning J. Agouti-related peptide-expressing neurons are mandatory for feeding. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1289–1291. doi: 10.1038/nn1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn T, Breininger J, Baskin D, Schwartz M. Coexpression of Agrp and NPY in fasting-activated hypothalamic neurons. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:271–272. doi: 10.1038/1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath T, Naftolin F, Kalra S, Leranth C. Neuropeptide-Y innervation of beta-endorphin-containing cells in the rat mediobasal hypothalamus: a light and electron microscopic double immunostaining analysis. Endocrinology. 1992;131:2461–2467. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.5.1425443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhtiniemi T, Wittekindt C, Laitinen T, Leppänen J, Salminen A, Poso A, Lahtela-Kakkonen M. Comparative and pharmacophore model for deacetylase SIRT1. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2006;20:589–599. doi: 10.1007/s10822-006-9084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein M, McVey M, Guarente L. The SIR2/3/4 complex and SIR2 alone promote longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by two different mechanisms. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2570–2580. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin C, Xu A, Lu X, Barsh G. Transcriptional regulation of agouti-related protein (Agrp) in transgenic mice. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5798–5806. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Yoon C, Park K, Shin C, Park K, Kim S, Cho B, Lee H. Changes in ghrelin and ghrelin receptor expression according to feeding status. Neuroreport. 2003;14:1317–1320. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000078703.79393.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura T, Feng Y, Kitamura Y, Chua SJ, Xu A, Barsh G, Rossetti L, Accili D. Forkhead protein FoxO1 mediates Agrp-dependent effects of leptin on food intake. Nat Med. 2006;12:534–540. doi: 10.1038/nm1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Könner A, Janoschek R, Plum L, Jordan S, Rother E, Ma X, Xu C, Enriori P, Hampel B, Barsh G, Kahn C, Cowley M, Ashcroft F, Brüning J. Insulin action in AgRP-expressing neurons is required for suppression of hepatic glucose production. Cell Metab. 2007;5:438–449. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Rajendran G, Liu N, Ware C, Rubin B, Gu Y. SirT1 modulates the estrogen-insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling for postnatal development of mammary gland in mice. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R1. doi: 10.1186/bcr1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Defossez P, Guarente L. Requirement of NAD and SIR2 for life-span extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2000;289:2126–2128. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Dentin R, Chen D, Hedrick S, Ravnskjaer K, Schenk S, Milne J, Meyers D, Cole P, Yates, Olefsky J, Guarente L, Montminy M. A fasting inducible switch modulates gluconeogenesis via activator/coactivator exchange. Nature. 2008;456:269–273. doi: 10.1038/nature07349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luquet S, Perez F, Hnasko T, Palmiter R. NPY/AgRP neurons are essential for feeding in adult mice but can be ablated in neonates. Science. 2005;310:683–685. doi: 10.1126/science.1115524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBurney M, Yang X, Jardine K, Hixon M, Boekelheide K, Webb J, Lansdorp P, Lemieux M. The mammalian SIR2alpha protein has a role in embryogenesis and gametogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:38–54. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.38-54.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napper A, Hixon J, McDonagh T, Keavey K, Pons J, Barker J, Yau W, Amouzegh P, Flegg A, Hamelin E, Thomas R, Kates M, Jones S, Navia M, Saunders J, DiStefano P, Curtis R. Discovery of indoles as potent and selective inhibitors of the deacetylase SIRT1. J Med Chem. 2005;48:8045–8054. doi: 10.1021/jm050522v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Y, Erion D, Yuan Z, Dietrich M, Shulman G, Horvath T, Gao Q. STAT3 inhibition of gluconeogenesis is downregulated by SirT1. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:492–500. doi: 10.1038/ncb1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacholec M, Chrunyk B, Cunningham D, Flynn D, Griffith D, Griffor M, Loulakis P, Pabst B, Qiu X, Stockman B, Thanabal V, Varghese A, Ward J, Withka J, Ahn K. SRT1720, SRT2183, SRT1460, and resveratrol are not direct activators of SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pani G, Fusco S, Galeotti T. Smaller, hungrier mice. Science. 2006;311:1553–1554. doi: 10.1126/science.311.5767.1553. author reply 1553–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Second Edition 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce A, Xu A. De novo neurogenesis in adult hypothalamus as a compensatory mechanism to regulate energy balance. J Neurosci. 2010;30:723–730. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2479-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto S, Roseberry A, Liu H, Diano S, Shanabrough M, Cai X, Friedman J, Horvath T. Rapid rewiring of arcuate nucleus feeding circuits by leptin. Science. 2004;304:110–115. doi: 10.1126/science.1089459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prozorovski T, Schulze-Topphoff U, Glumm R, Baumgart J, Schröter F, Ninnemann O, Siegert E, Bendix I, Brüstle O, Nitsch R, Zipp F, Aktas O. Sirt1 contributes critically to the redox-dependent fate of neural progenitors. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:385–394. doi: 10.1038/ncb1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purushotham A, Schug T, Xu Q, Surapureddi S, Guo X, Li X. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of SIRT1 alters fatty acid metabolism and results in hepatic steatosis and inflammation. Cell Metab. 2009;9:327–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadori G, Lee C, Bookout A, Lee S, Williams K, Anderson J, Elmquist J, Coppari R. Brain SIRT1: anatomical distribution and regulation by energy availability. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9989–9996. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3257-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravussin E, Tschöp M, Morales S, Bouchard C, Heiman M. Plasma ghrelin concentration and energy balance: overfeeding and negative energy balance studies in twins. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4547–4551. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.9.8003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers J, Puigserver P. Fasting-dependent glucose and lipid metabolic response through hepatic sirtuin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12861–12866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702509104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogina B, Helfand S. Sir2 mediates longevity in the fly through a pathway related to calorie restriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15998–16003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404184101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A, Irani B, Moore M, Haskell-Luevano C, Millard W. Ghrelin-induced food intake and growth hormone secretion are altered in melanocortin 3 and 4 receptor knockout mice. Peptides. 2005;26:1720–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon J, Pasupuleti R, Xu L, McDonagh T, Curtis R, DiStefano P, Huber L. Inhibition of SIRT1 catalytic activity increases p53 acetylation but does not alter cell survival following DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:28–38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.28-38.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissenbaum H, Guarente L. Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2001;410:227–230. doi: 10.1038/35065638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschöp M, Statnick M, Suter T, Heiman M. GH-releasing peptide-2 increases fat mass in mice lacking NPY: indication for a crucial mediating role of hypothalamic agouti-related protein. Endocrinology. 2002;143:558–568. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.2.8633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschöp M, Wawarta R, Riepl R, Friedrich S, Bidlingmaier M, Landgraf R, Folwaczny C. Post-prandial decrease of circulating human ghrelin levels. J Endocrinol Invest. 2001;24:RC19–RC21. doi: 10.1007/BF03351037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Saint-Pierre D, Taché Y. Peripheral ghrelin selectively increases Fos expression in neuropeptide Y - synthesizing neurons in mouse hypothalamic arcuate nucleus. Neurosci Lett. 2002;325:47–51. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Boyle M, Palmiter R. Loss of GABAergic signaling by AgRP neurons to the parabrachial nucleus leads to starvation. Cell. 2009;137:1225–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu A, Kaelin C, Takeda K, Akira S, Schwartz M, Barsh G. PI3K integrates the action of insulin and leptin on hypothalamic neurons. J Clin Invest. 2005a;115:951–958. doi: 10.1172/JCI24301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu A, Kaelin C, Morton G, Ogimoto K, Stanhope K, Graham J, Baskin D, Havel P, Schwartz M, Barsh G. Effects of hypothalamic neurodegeneration on energy balance. PLoS Biol. 2005b;3:e415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Baffy G, Perret P, Krauss S, Peroni O, Grujic D, Hagen T, Vidal-Puig A, Boss O, Kim Y, Zheng X, Wheeler M, Shulman G, Chan C, Lowell B. Uncoupling protein-2 negatively regulates insulin secretion and is a major link between obesity, beta cell dysfunction, and type 2 diabetes. Cell. 2001;105:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.