Abstract

Objectives

This study presented structural characteristics of a multiplex HIV transmission risk network of drug-using male sex workers (MSWs) and associates. The network comprised social, sexual, and drug-using relationships as well as affiliations with social venues.

Methods

Using a sample of 387 drug-using MSWs and their male and female associates, we estimated an exponential random graph model to examine the venue-mediated relationships between individuals, the structural characteristics of relationships not linked to social venues, and homophily.

Results

Individuals affiliated with the same social venues, bars, or street intersections were more likely to have one-directional ties (weak ties) with others. Sex workers, as compared to other associates, were less likely to have reciprocated ties (strong ties) to other sex workers with the same venues. Individuals tended to have reciprocated ties not linked to venues. Partner choice tended to be based on homophily.

Conclusions

Social venues may provide a milieu for forming weak ties in HIV transmission risk networks centered on MSWs, which may foster the efficient diffusion of prevention messages as diverse information is obtained and information redundancy is avoided.

Keywords: social network analysis, multiplex HIV transmission risk network, drug-using male sex workers, most-at-risk MSM, HIV risk behavior, exponential random graph models

INTRODUCTION

Sex work increases the risk of contracting and transmitting human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) through unprotected sexual behaviors and/or substance use (1). Male sex workers (MSWs) experience high rates of HIV infection, both globally and domestically (2–4). In North America, HIV prevalence among MSWs is estimated to range from 5% to 31% (4). MSWs have high rates of risky sexual behavior and substance use, including drug injection (5–7). However, public health issues related to MSWs have been understudied, and current HIV prevention programs underserve MSWs (4).

MSWs are not homogeneous nor are the contexts of male sex work uniform (4, 8). Because male sex work takes diverse forms in a variety of contexts (8, 9), HIV risks may also vary by context. MSWs who solicit sex on the streets are at the high risk of HIV infection and the context of the street may increase the risk. MSWs working in street venues are more likely to have few financial resources, be undereducated, live in unstable housing or on the streets, be unemployed or disabled, and engage in sex work as a means of survival (8). A number of MSWs and their clients self-identify as heterosexual (10). Men who have sex with men and women (MSM/W) have higher rates of both transactional sex and concurrent illicit drug use and sex, compared to men who have sex with men only, and, among MSM/W, both transactional sex and concurrent illicit drug use predict risky sexual behavior (11).

Although socio-demographic characteristics, HIV infection, and risk behaviors of MSWs have been documented (12, 13), relatively few studies have provided a relational account of HIV risk within male sex work networks. It is known, for example, that networks of MSWs are connected to other networks of other high-risk groups (2, 8, 10, 14, 15). Through these network ties, MSWs may bridge MSM, female sex workers, drug users, and other less risky groups (2, 16). MSM/W are more likely to engage in sex for drugs or money than are other MSM, and MSM/W occupy a central position in the network of HIV-infected male individuals (17). However, given the diversity of male sex work, it may be inappropriate to conceptualize MSWs as a core group (18).

Social networks are the structures within which norms are developed and implemented and social support occurs (19, 20). Most risk-potential linkages within networks are social (20), and sex ties are often formed through social circles (21). MSWs form unique social networks (9, 22), most likely involving risky drug use and sexual behaviors. The networks are often hierarchical structures in which network leaders control areas for soliciting sex, and the network structure provides mutual support for soliciting sex (9).

Rarely do studies on HIV risk networks that involve MSWs regard the network as composed of “persons, places, and the relevant links connecting them” (p. 684) (23). Social venues are an important part of the network structure, forming the setting for MSWs’ social life and facilitating the formation of “sexual affiliation networks” (24). Our prior study (25) underscored the duality of people and places (26) by focusing on affiliation networks between MSWs and social venues. We found centralized affiliation patterns around a small number of highly interdependent venues. Although interdependent, the venues presented distinct patterns of venue-based clustering (25). These findings, however, were limited because the study focused on venue affiliation. Non-venue-based direct ties also may be important because they are expected to occur within social, drug-use, and sexual relationships. These types of relationships may have different emotional and interpersonal contexts (27) that would tend to result in different patterns and types of ties.

This study defined a “multiplex transmission risk network” as composed of multifaceted social contexts that comprise a mix of social, sexual, and drug-using ties and affiliation ties to social venues. The social network perspective informs relational mechanisms of information diffusion and social influence at the entire network and personal network levels. Granovettor’s theory of “the Strength of Weak Ties (SWT)” posits that “the weak tie between ego and his acquaintance, therefore, becomes not merely a trivial acquaintance tie but rather a crucial bridge between the two densely knit clumps of close friends” (p. 202) (28). Weak ties avoid information redundancy by enabling individuals to access diverse information and to facilitate the diffusion of information throughout the entire network (29). Although weak ties facilitate information diffusion, they may not be sufficiently powerful enough to change behavior given the ties’ transient and impassive nature.

Rarely have network studies focused on the role that affiliation ties play in forming direct ties between individuals. This study defined “venue-mediated weak/strong ties” as one-mode social, sexual and drug-using ties formed through jointly affiliating with the same venue(s). One objective of this study was to examine and statistically test local relational features of venue-mediated weak/strong ties among MSWs and their associates. Based on the effect of bar-based social influence interventions led by opinion leaders on HIV risk reduction (30, 31), HIV prevention messages disseminated within venues are expected to facilitate the diffusion of information and, thus, weak ties are more likely than strong ties to be observed linked to social venues.

In personal networks, reciprocated ties suggest higher levels of trust and intimacy, and, in some cases, a strong tendency to engage in risky behaviors (32). The risk of engaging in behaviors that transmit HIV are also heightened during sex for money exchanges, particularly if there is a strong economic incentive for doing so. This suggests that risk is related to the multiple types of ties determined by context. Additionally, homophily affects network ties by influencing the information that people receive, the attitudes formed, and the social interactions experienced (33). A second objective of the study was to examine the tendency of reciprocity and the effect of homophily on HIV status and socio-demographic and behavioral factors when forming risk-potential relationships that comprise social, sexual, and/or drug-using ties but are not linked to social venues. The likelihood of engaging in risk-taking behavior is stronger in relationships with a high degree of homophily, as information flows and persuasion tend to be more frequent among like pairs (32). This study tests these relational features by taking a stochastic network modeling approach.

METHODS

Data for the study were collected between May 2003 and February 2004 as part of a study of drug-using MSWs networks in Houston, Texas. Participants were recruited using a combination of sampling methods described in greater detail elsewhere (34, 35). To construct the sample, we interviewed key informants and asked them to help contact focal participants. Focal participants were eligible for the study if they were: a self-identified male at least 17 years old, had exchanged sex for money with another man in the last seven days, and had smoked crack cocaine or injected an illicit substance in the past 48 hours before being screened. During the interview, focal participants were asked to name men and women with whom they interacted socially or with whom they used drugs or had sex. Those names were listed and apportioned into strata that consisted of sex/drug-use partners, friends, paying sex partners, and other social contacts. Names were then weighted to give preference to sex and drug-use contacts. Focal participants were asked to contact network members on the list and ask them to participate in the study. The same process was used with network members to create a list of tertiary network members. Eligibility criteria for network members were: 17 years old and linked to the focal or secondary (referring) participants. Study procedures and data collection instruments were approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Analytic Sample

A sample of 334 males (84%) and 62 females (16%) were interviewed to collect socio-demographic, HIV/STI histories, drug use, and risky sexual behavior data. In addition to personal data, respondents were asked about their network contacts’ demographic characteristics, HIV status, risky sexual behaviors, and relationship with the contact. Data on venue affiliation were collected by asking respondents the names of places and/or street intersections where they spent time. Intersections were validated using a city map, then geo-coded. Fifteen bars and 51 intersections were identified, for a total of 66 venues used for our analysis.

Data were used to generate an analytic sample consisting of 735 dyads where contacts were also respondents. This generated nine isolates who had no ties to other individuals or no affiliation with a venue and who were dropped from the analysis to avoid model divergence. Dyads were composed 325 (84%) males and 62 (16%) females, and included 28% focal respondents and 36% secondary and 36% tertiary contacts.

Measures

Network data

Social network data were created based on a directed one-mode actor-by-actor adjacency matrix, where a tie was defined based on any nominations of social/sexual/drug-use contacts. The study defined weak ties as any asymmetric ties between individuals that ran in one direction only (29), and strong ties as ties that ran in both directions. Affiliation network data were created based on a two-mode actor-by-venues matrix (row index 387 actors and column indexes 66 venues), where a tie was defined as having an affiliation with a specific venue. One- and two-mode networks were combined to form the multiplex network data.

HIV status and risk or protective sexual behaviors

HIV status was measured by respondents’ self-report of HIV testing or status: never tested, negative test, positive test, or indeterminate test. HIV risk sexual behavior measures included ever having traded sex for money, the number of paying sex partners, and the number of non-paying casual sex partners during the last 30 days (as a continuous scale). Protective sexual behavior was measured as frequency of condom use during anal intercourse with paid or casual sex partners in the last seven days, and defined as consistent condom use (i.e., always using a condom).

Socio-economic and demographic variables

Race/ethnicity was coded as Black, White, Hispanic, or other. Self-identified homeless was coded as “homeless” or “no-homeless.” Self-identified sexual orientation was coded as “gay,” “straight,” or “bisexual.” Age, years of schooling, number of lifetime arrests, and months of incarceration were measured as continuous scales. To account for the sampling strategy, dummy variables representing recruitment status of sampling design (seeds, secondary or tertiary contacts) were created.

Data Analysis

Visualization of multiplex network

A multiplex HIV transmission risk network consisting of a one-mode network and a two-mode venue affiliation network was visualized to describe the overall structural pattern in relation to self-reported HIV status, sex work status, and venue types. NetworkX (36) was used for visualization.

Exponential random graph models (ERGMs)

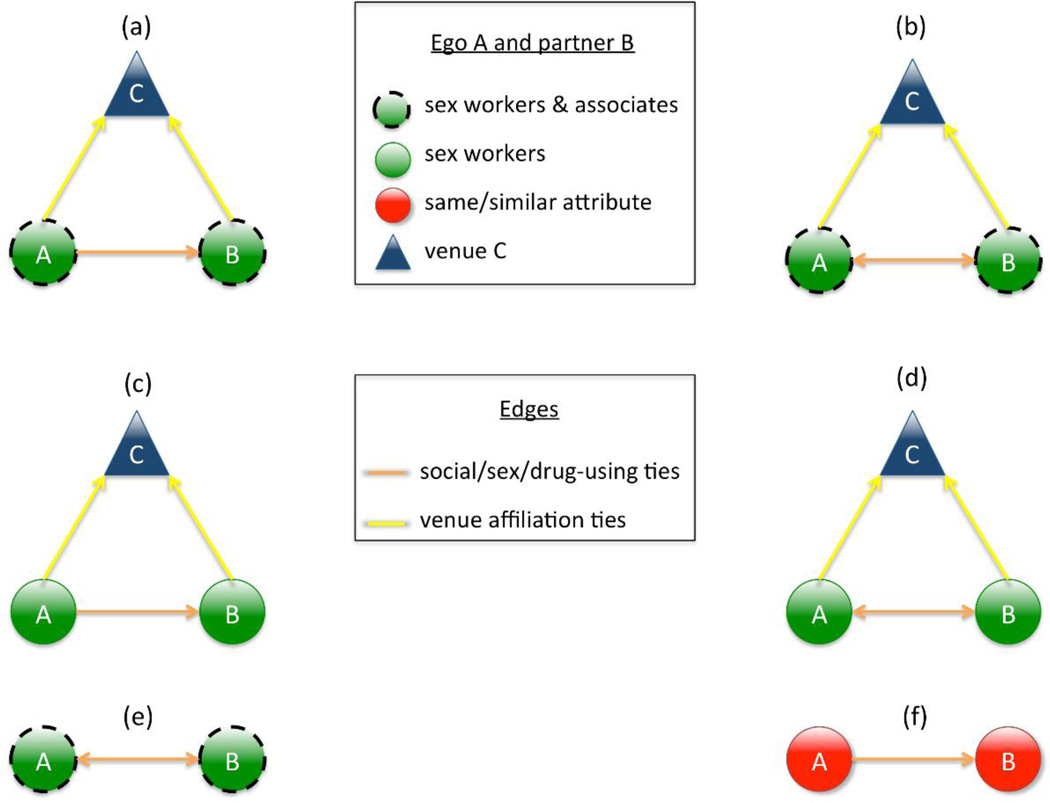

ERGMs model the observed network endogenous structure by taking into account the dependencies among network ties (37), as well as the dependencies between network ties and exogenous covariates (38, 39). A one-mode network was modeled (39) with the two-mode network and various attributes/measures of the behavior as covariates. Results were used to test how individuals’ self-reported HIV status, risk and protective behavior and attributes, and affiliated venues affect the partners of their social/sexual/drug-use relationships. Study objectives were examined by statistically testing whether the graph configurations of a venue-mediated weak tie effect (Figure 1a) by sex workers (Figure 1c), venue-mediated strong tie effect (Figure 1b) by sex workers (Figure 1d), one-mode reciprocated tie effect (Figure 1e), and homophily effect (Figure 1f) are more likely to be observed than expected by chance. The modeling results were generated using MPNet (40).

Figure 1.

Graph configurations of venue-mediated weak/strong tie effects among actors A and B and Venue C. (a) represents a venue-mediated weak tie effect, (b) represents a venue-mediated strong tie effect, (c) represents a venue-mediated weak tie effect between sex workers, (d) represents a venue-mediated strong tie effect between sex workers (e) represents one-mode reciprocated tie effect, and (f) represents one-mode relational homophily effect.

Reviews and detailed descriptions of the ERGMs that were applied (model specification, graph configurations, mathematical expressions, and interpretations) can be found in Table 1S in the Supporting Information.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

The demographic and behavioral characteristics of the 387 MSWs and their associates are shown in Table 1. Among the 735 dyads, 40% of social ties were overlapped with sex ties, 80% of social ties were overlapped with drug-using ties, and 33% of social ties were overlapped with both sex and drug-using ties. On average, the sample was affiliated with one venue (SD = .90, Min = 0, Max = 4).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for our analytic sample: Percentages with size n or means with standard deviations and min and max values for characteristics of drug-using MSWs and their associates (N=387)

| Variable | Category | Percentage (n) or Mean (SD; Min, Max) |

|---|---|---|

| HIV status | Positive | 20% (79) |

| Negative | 64% (247) | |

| Unknown (incl. indeterminate) | 16% (61) | |

| Gender | Male | 84% (325) |

| Female | 16% (62) | |

| 16–29 years old | 40% (155) | |

| 30–39 years old | 36% (138) | |

| 40+ years old | 24% (93) | |

| Race/ethnicity | White | 47% (183) |

| Black | 43% (168) | |

| Hispanic | 8% (31) | |

| Homelessness | 49% (188) | |

| Sexual orientation | Gay | 32% (122) |

| Straight | 25% (95) | |

| Bisexual | 44% (170) | |

| Years of schooling | 11.24 (2.15; 4, 19) | |

| Number of cumulative arrest | 10.71 (13.72; 0, 90) | |

| Months of incarceration | 48.39 (56.02; 0, 300) | |

| Recruitment status | Seeds | 28% (107) |

| Secondary contacts | 36% (140) | |

| Tertiary contacts | 36% (140) | |

| Ever experienced in sex work | 75% (292) | |

| Never experienced in sex work | 25% (95) | |

| Number of paid sex partners | 29.22 (38.83; 0, 150) | |

| Number of casual sex partners | 6.92 (19.43; 0, 150) | |

| Protective sex | Consistent condom use | 21% (80) |

| Non-consistent condom use | 40% (155) |

Note: Number of sex partners refers to the last 30 days; the upper limit was set to 150 to minimize recollection problems. There were 39% missing cases for the Protective sex variable, and 1% for the “Others” category for the Race/ethnicity variable.

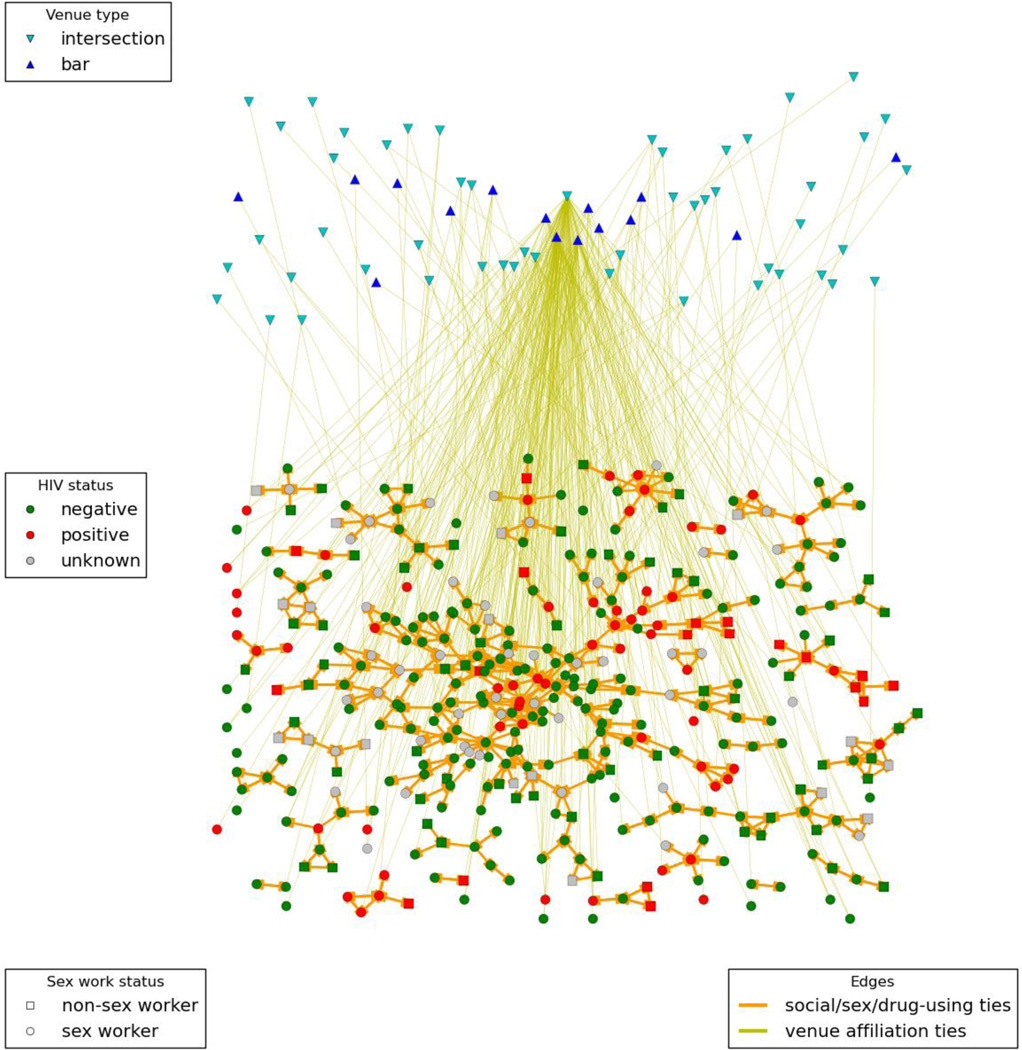

Visualization of Multiplex Transmission Risk Network

Figure 2 illustrates the multiplex HIV transmission risk network in relation to HIV status, sex work status, and venue types. Although these graphs represent overall structural patterns of the multiplex risk network, they are limited in their ability to identify some distinctive features of the observed network, which were examined by estimating ERGMs.

Figure 2.

Multiplex HIV transmission network among 378 MSWs and their associates in relation to HIV status, sex work status, and affiliation with social venues.

Results of ERGMs

Table 2 shows the results of ERGM parameter estimates and standard errors for the network effects of the one-mode network with the two-mode network and actor attributes/behavior as exogenous covariates. Statistically significant parameter estimates at α = .05 level for two-sided test are bolded.

Table 2.

ERGM effects, parameter estimates, and standard errors for the multiplex one-mode and two-mode risk network

| ERGM components | Structural effects | Parameter estimate | Standard error |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-mode structure | Arc (density) | −7.391 | 0.421 |

| Reciprocity | 7.614 | 0.249 | |

| No-receiver | −3.065 | 0.414 | |

| Isolate | −2.094 | 0.400 | |

| Alternating-in-star (AinS) | 1.395 | 0.235 | |

| Alternating-out-star (AoutS) | −0.977 | 0.188 | |

| Alternating-triangle (AT) | 1.007 | 0.054 | |

| Alternating-two-path (A2P) | −0.132 | 0.033 | |

| Sender having attributes/behavior | HIV positive | −0.615 | 0.212 |

| Race/Ethnicity: Black | −0.982 | 0.275 | |

| Race/Ethnicity: White | −0.426 | 0.289 | |

| Homeless | −0.619 | 0.159 | |

| Bisexual | −0.056 | 0.170 | |

| Sex work | −0.059 | 0.209 | |

| Consistent condom use | −0.341 | 0.180 | |

| Receiver having attributes/behavior | HIV positive | 0.158 | 0.168 |

| Race/Ethnicity: Black | −0.855 | 0.266 | |

| Race/Ethnicity: White | −0.299 | 0.243 | |

| Homeless | 0.168 | 0.133 | |

| Bisexual | −0.346 | 0.149 | |

| Sex work | −0.647 | 0.185 | |

| Consistent condom use | 0.297 | 0.141 | |

| Homophily on binary attributes/behavior | HIV positive | 0.740 | 0.141 |

| Race/Ethnicity: White | 0.507 | 0.190 | |

| Race/Ethnicity: Black | 1.648 | 0.218 | |

| Homeless | 0.415 | 0.114 | |

| Bisexual | 0.375 | 0.105 | |

| Sex work | 0.524 | 0.130 | |

| Consistent condom use | 0.278 | 0.128 | |

| Homophily on continuous attributes/behavior | Age | −0.037 | 0.005 |

| Years of schooling | 0.011 | 0.016 | |

| Number of cumulative arrest | −0.001 | 0.002 | |

| Months of incarceration | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Number of paid sex partners | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Number of casual sex partners | −0.004 | 0.002 | |

| Venue-mediated ties | Weak tie | 0.899 | 0.310 |

| Strong tie | −1.039 | 0.645 | |

| Venue-mediated ties among sex workers | Weak tie | 0.494 | 0.318 |

| Strong tie | −1.301 | 0.668 |

Note: Significant parameter estimates (p< .05) are bolded. “Hispanic” Race/ethnicity variable did not have significant effects.

Structural effects of one-mode network

The social ties in this multiplex one-mode network were highly reciprocal, meaning that individuals tended to exhibit mutual ties running in both directions. These networks are characterized by a small number of frequently nominated individuals in the center of network who received many more nominations than we would have been expected if it were at random. Four of the 387 individuals received more than 10 nominations, while 240 received one or two nominations. There also was a tendency for all network members to receive similar numbers of partner nominations. Individuals tended to form closed, but hierarchically structured ties, such that frequently nominated individuals tended to be located at the top of a triangle configuration. These individuals also tended not to share multiple sexual, social, and/or drug partners unless they were connected to each other. Given these structural effects, there are fewer individuals that were isolated or did not receive any nominations in the one-mode network.

Individuals who were HIV positive, Black, and homeless nominated fewer others, suggesting that they were less active in the network. Those who were Black, identified as bisexual, or were sex workers were nominated less frequently than others in the network. Individuals who consistently used condoms were nominated more frequently than others.

Homophily effects

HIV-positive individuals, Whites, Blacks, homeless, bisexuals, sex workers, and individuals who consistently use condoms had a tendency to choose sexual, social, and/or drug partners with the same attributes/behaviors with themselves. There also was a tendency to choose others of similar age or number of casual sex partners. Note that, for continuous attributes, a negative homophily parameter estimate suggests that there was a tendency for individuals to nominate others with similar attribute/behavior measures, as the statistic that represents homophily is defined based on the differences in attribute values of pairs of individuals.

Venue-mediated weak/strong tie effects

By treating one-directional ties as weak ties and bi-directional ties as strong ties, individuals affiliated with the same venue were more likely to have weak ties. Results also showed that sex workers were less likely to have reciprocated ties to other sex workers. Results of the recruitment status effect of sampling design and goodness-of-fit tests are reported in the Supporting Information.

DISCUSSION

This study took a social network approach to investigate the structural features that characterize a multifaceted HIV transmission risk network of drug-using male sex workers and their associates in the context of social venues and personal network not linked to venues. The study found that the one-mode risk network was characterized by reciprocated relationships, i.e., individuals mutually nominated their social, sexual, and/or drug-use partners, indicative of close relationships. Given this general structural tendency, individuals were more likely to choose their sexual, social, and/or drug partners based on homophily in HIV-positive status, age, race/ethnicity, homelessness, bisexual orientation, the number of casual sex partners, and protective sex behavior. In combination with venue affiliation, individuals had weak ties with those from the same venue. Conversely, there was an absence of reciprocated or strong ties associated with the same venues. This tendency was especially notable for sex workers affiliated with the same venues.

One of the distinguishing features of the study was that venues were examined as part of the risk network. Findings suggest that the venues named by drug-using MSWs and their associates, mostly bars and street corners, facilitate the formation of weak, but not strong, ties. The tendency to form weak ties may be stronger, perhaps in part, because the venues in which in which MSWs gather are the same as where they also may solicit paying sex partners. Findings also suggest that individuals form strong ties in their personal networks outside social venues and choose their social, sexual, and/or drug-use partners based on homophily of ties based on disease status, risk and protective behaviors, and characteristics. For example, HIV-positive men were more likely to have HIV-positive social, sexual, and/or drug-use partners. Men who self-identified as bisexual were more likely to have bisexual sexual, social, and/or drug-use partners.

The finding of homophily of ties supports the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s supposition that social network strategies for HIV testing, prevention, and engagement in care are important (41, 42). Our findings extend this supposition by suggesting that the ties within the network of at-risk groups also are important. For example, peers should not be considered based only on a single identifying characteristic, such as male sex work. Multiple characteristics, rather than a single factor such as race/ethnicity, may identify an individual as a peer. Developing more sophisticated models of peers could enhance the utility of a network-level HIV intervention by resulting in significant breadth when targeting the commercial sexual and drug networks. Interventions within personal networks should consider targeting clusters of like individuals based on a number of identifying factors.

The structural features of a network may be integral to successfully disseminating prevention messages and delivering social influence interventions. The utility of venue-based prevention interventions has been demonstrated by Kelly et al.’s bar-based opinion leader intervention among gay men (31) and among groups of male sex workers (22). However, a study of the diffusion mechanism of prevention messages through the opinion leaders inside of venues has not been undertaken in the literature. Further, although the potential utilities of venue-based HIV prevention and intervention have been suggested in the literature (24, 25, 43–46), why and how they would be used is unclear and often unspecified. In regard to network-level interventions employed in public health (47), the weak ties derived from joint venue affiliations suggest that venues could be promising settings for strategically diffusing behavior change messages. Nevertheless, weak ties are not sufficiently powerful for behavior change, only for information diffusion. However, if peers are considered role models, then this modeling may have a positive impact on both perceived norms and behavior. Our study suggests that relying on weak ties as a mechanism for the efficient diffusion of intervention messages may be more beneficial for some groups than is focusing on popular opinion leaders.

The study has certain limitations. The sample of drug-using MSWs was recruited from street or bar settings. Considering the diversity of sex workers, our results may not be generalizable to MSWs in different work circumstances, in differing policing, history, or norms, or who work in different geographic locations (4). Further, the data were collected from 2003 to 2004. Although it is very unlikely, the organization of street- or bar-based sex work has may have changed since the data were collected. It is more likely that the expansion of digital media may have led to the expansion of sex work venues. However, many drug-using men who solicit sex in street and bar settings are unlikely to have the financial wherewithal to consistently access digital media. Nonetheless, our results should be interpreted with caution as applied to digital opportunities for sex work.

Methodologically, although ERGM analysis of this study controls for recruitment status to minimize the effect of sampling design on structural features, the analysis was still subject to potential bias or artifacts of the sampling strategy. The study conceptualized the multiplex one-mode risk network as a mixture of social, sexual, and drug-using relationships and operationalized these as the types of ties investigated. Consequently, the study was limited in its ability to explore the relative contributions of the multiple types of relationships to structuring homophily. Homophily of ties may have been stronger than the results suggest if more overlapping ties had been investigated (33). Finally, the study did not consider HIV protective venue affiliation, such as HIV health center or education centers that provide HIV prevention (46). Future research should examine whether our findings apply to these different types of venues.

Despite these limitations, the findings provide a structural account of the dynamics of HIV transmission risk. Given the occupational hazards of HIV and other infections that MSWs encounter as part of their day-to-day activities, the paucity of HIV prevention interventions and treatment services that have been developed for MSWs (4), and the risks posed to associates, the structuring interventions to account for the social and venue-based affiliation network structure of male sex work is more likely to be effective than the “one-size-fits-all, off-the-shelf” interventions.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Kayo Fujimoto, Center for Health Promotion and Prevention Research, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

Peng Wang, Division of School of Behavioural Science, Department of Psychology, University of Melbourne VIC 3010

Michael W. Ross, Center for Health Promotion and Prevention Research, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

Mark L. Williams, Department of Health Policy and Management, College of Public Health & Sciences, Florida International University

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV risk among adult sex workers in the United States: report of Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexual Transmitted Diseases and Tuberculosis Prevention. [Accessed October 28, 2014];2013 Sep; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library_factsheet_HIV_among_sex_workers.pdf.

- 2.Morse EV, Simon PM, Osofsky HJ, et al. The male street prostitute: a vector for transmission of HIV infection into the heterosexual world. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:535–539. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90287-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elifson KW, Boles J, Sweat M. Risk factors associated with HIV infection among male prostitutes. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(1):79–83. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baral SD, Friedman RM, Geibel S, Rebe K, et al. Male sex workers: practices, contexts, and vulnerabilities for HIV acquisition and transmission. The Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60801-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams ML, Timpson S, Klovdahl A, Bowen A, Ross M, Keel K. HIV risk among a sample of male sex workers. AIDS. 2003;17:1402–1404. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200306130-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rietmeijer C, Wolitski RJ, Fishbein M, Corby NH, et al. Sex hustling, injection drug use, and nongay identification by men who have sex with men. Associations with high-risk sexual behaviors and condom use. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:353–360. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199808000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Mayer KH, Tinsley JP, Safren SA. Tricks of the trade: sexual health behaviors, the context of HIV risk, and potential prevention intervention strategies for male sex workers. LGBT Health Res. 2008;4(4):195–209. doi: 10.1080/15574090903114739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minichiello V, Scott J, Callander D. New pleasures and old dangers: reinventing male sex work. J Sex Res. 2013;50(3–4):263–275. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.760189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boles J, Elifson KW. The social organization of transvestite prostitution and AIDS. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:85–93. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott J, Minichiello V. Reframing male sex work. In: Scott J, Minichiello SJ, editors. Male Sex Work and Society. New York, NY: Harrington Park Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman RM, Kurtz SP, Buttram ME, Wei C, et al. HIV risk among substance-using men who have sex with men and women (MSMW): findings from South Florida. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:111–119. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0495-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belza MJ, Llácer A, Mora R, Morales M, Castilla J, de la Fuente L. Sociodemographic characteristics and HIV risk behaviour patterns of male sex workers in Madrid, Spain. AIDS Care. 2001;13(5):677–682. doi: 10.1080/09540120120063296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Timpson SC, Ross MW, Williams ML, Atkinson J. Characteristics, drug use, and sex partners of a sample of male sex workers. Am J Drug Alcohol Ab. 2007;33:63–69. doi: 10.1080/00952990601082670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Logan TD. Personal characteristics, sexual behaviors, and male sex work: a quantitative approach. Am Sociol Rev. 2010;75(5):679–704. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Tinsley JP, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Street workers and internet escorts: contextual and psychosocial factors surrounding HIV risk behavior among men who engage in sex work with other men. J Urban Health. 2008;86(1):54–66. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9316-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams ML, Bowen AM, Timpson S, Keel BK. Drug injection and sexual mixing patterns of drug-using male sex workers. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30(7):571–574. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200307000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hightow LB, Leone PA, MacDonald DM, Mccoy SI, et al. Men who have sex with men and women: a unique risk group for HIV transmission on North Carolina college campuses. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(10):585–593. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000216031.93089.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker M. Core groups and the transmission of HIV: Learning from male sex workers. J Biosoc Sci. 2006;38:117–131. doi: 10.1017/S0021932005001136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider JA, Cornwell B, Ostrow D, Michaels S, Schumm P, Laumann EO, et al. Network mixing and network influences most linked to HIV infection and risk behavior in the HIV epidemic among Black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):e28–e36. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman SR, Aral S. Social networks, risk-potential networks, health, and disease. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):411–418. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dragowski EA, Halkitis PN, Moeller RW, Siconolfi DE. Social and sexual contexts explain sexual risk taking in young gay, bisexual, and other young men who have sex with men, ages 13–29 years. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2013;12:236–255. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller RL, Klotz D, Eckholdt HM. HIV prevention with male prostitutes and patrons of hustler bars: replication of an HIV preventive intervention. Am J Commun Psychol. 1998;26(1):97–131. doi: 10.1023/a:1021886208524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klovdahl AS, Graviss EA, Yaganehdoost A, Ross MW, Wanger A, Adamse GJ, et al. Networks and tuberculosis: an undetected community outbreak involving public places. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:681–694. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frost SDW. Using sexual affiliation networks to describe the sexual structure of a population. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(Suppl I):i37–i42. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.023580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujimoto K, Williams ML, Ross MW. Venue-based affiliation network and HIV risk behavior among male sex workers. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(6):453–458. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31829186e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breiger RL. Duality of persons and groups. Soc Forces. 1974;53:181–190. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujimoto K, Williams ML, Ross MW. A network analysis of relationship dynamics in sexual dyads as correlates of HIV risk misperceptions among high-risk MSM. Sex Transm Infect. 2014 doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Granovetter MS. The strength of weak ties: a network theory revisited. Sociol Theor. 1983;1:201–233. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Granovetter MS. The strength of weak ties. Am J Sociol. 1973;78(6):1360–1380. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly JA. Popular opinion leaders and HIV prevention peer education: resolving discrepant findings, and implications for the development of effective community programmes. AIDS Care. 2004;16(2):139–150. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001640986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelly JA, St.Lawrence JS, Diaz YE, Stevenson LY, Hauth AC, Kalichman SC, et al. HIV risk behavior reduction following intervention with key opinion leaders of population: an experimental analysis. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:168–171. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valente TW. Social Networks and Health: Models, Methods, and Applications. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:415–444. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams ML, Atkinson J, Klovdahl AS, Ross MW, Timson S. Spatial bridging in a network of drug-using male sex workers. J Urban Health. 2005;82(Suppl. 1):i35–i42. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams ML, Ross M, Atkinson JA, Bowen A, Klovdahl A, Timpson S. An investigation of concurrent sex partnering in two samples having large numbers of sex partners. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17:309–314. doi: 10.1258/095646206776790123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hagberg AA, Schult DA, Swart PJ. Exploring network structure, dynamics, and function using NetworkX. In: Varoquaux G, Vaught T, Millman J, editors. Proceedings of the 7th Python in Science Conference (SciPy2008); Pasadena CA. 2008. pp. 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pattison PE, Snijders TAB. Statistical models for social networks: future directions. In: Lusher D, Koskinen J, Robins G, editors. Exponential Random Graph Models for Social Networks: Theories, Methods and Applications. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robins G, Elliott P, Pattison PE. Network models for social selection processes. Soc Networks. 2001;23:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang P, Robins G, Pattison P, Lazega E. Exponential random graph models for multilevel networks. Soc Networks. 2013;35(1):96–115. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang P, Robins G, Pattison P. PNet: A Program for the Simulation and Estimation of Exponential Random Graph Models. Australia: University of Melbourne; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kimbrough LW, Fisher HE, Jones KT, Johnson W, et al. Accessing social networks with high rates of undiagnosed HIV infection: the social networks demonstration project. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):1093–1099. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCree D, Millett G, Baytop C, Royal S, et al. Lessons learned from use of social neetwork strategy in HIV testing programs targeting African Amnerican men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1851–1099. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holloway IW, Rice E, Kipke MD. Venue-based network analysis to inform HIV prevention efforts among young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Prev Sci. 2014;15:419–427. doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0462-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee SS, Tam DK, Tan Y, Mak WL, et al. An exploratory study on the social and genotypic clustering of HIV infection in men having sex with men. AIDS. 2009;23(13):1755–1764. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832dc025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider JA. Sociostructural 2-mode network analysis: critical connections for HIV transmission elimination. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(6):459–461. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000430672.69321.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneider JA, Walsh T, Cornwell B, Ostrow D, Michaels S, Laumann EO. HIV health center affiliation networks of black men who have sex with men: disentangling fragmented patterns of HIV prevention. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(8):598–604. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182515cee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valente TW. Network interventions: a taxonomy of behavior change interventions. Science. 2012;6:49–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1217330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.