Abstract

Background

For older adults, falls threaten their health, independence, and quality of life. Knowing the circumstances surrounding falls is essential for understanding how behavioral and environmental factors interact in fall events. It is also important for developing and implementing interventions that are effective and acceptable to older adults. This study investigated the circumstances and injury outcomes of falls among community-dwelling older adults at high risk of falling.

Methods

In this secondary analysis, we examined the circumstances and outcomes of falls experienced by 328 participants in the Dane County (Wisconsin) Safety Assessment for Elders (SAFE) Research Study. SAFE was a randomized controlled trial of a community-based multifactorial falls intervention for older adults at high risk for falls, conducted from October 2002 to December 2007. Participants were community-dwelling adults aged ≥65 years who reported at least one fall during the year after study enrollment. Falls were collected prospectively using monthly calendars. Everyone who reported a fall was contacted by telephone to determine the circumstances surrounding the event. Injury outcomes were defined as none, mild (injury reported but no treatment sought), moderate (treatment for any injury except head injury or fracture), and severe (treatment for head injury or fracture).

Results

Data were available for 1,172 falls. A generalized linear mixed model analysis showed that being age ≥85 (OR = 2.1, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.2–3.9), female (OR = 2.1, 95% CI = 1.3–3.4), falling backward and landing flat (OR = 5.6, 95% CI = 2.9–10.5), sideways (OR = 4.6, 95% CI = 2.6–8.0) and forward (OR = 3.3, 95% CI = 2.0–5.7) were significantly associated with the likelihood of injury. Of 783 falls inside the home, falls in the bathroom were more than twice as likely to result in an injury compared to falls in the living room (OR = 2.4, 95% CI = 1.2–4.9).

Conclusions

Most falls among these high risk older adults occurred inside the home. The likelihood of injury in the bathroom supports the need for safety modifications such as grab bars, and may indicate a need for assistance with bathing. These findings will help clinicians tailor fall prevention for their patients and have practical implications for retirement and assisted living communities and community-based fall prevention programs.

Keywords: Circumstances, Elderly, Falls, Fracture, Injury

Background

For older adults, falls and associated injuries threaten their health, independence and quality of life. More than a third of people aged 65 and older living independently fall each year (Tromp et al. 2001) and falls are the leading cause of injury-related deaths and hospital emergency department visits (CDC 2013).

While numerous fall risk factors have been identified, (Rubenstein and Josephson 2002) more limited information is available about the detailed circumstances surrounding falls among community-dwelling older adults. Several studies have used retrospective survey data to analyze falls that occurred in the previous year (Morris et al. 2004, Milat et al. 2011). Other studies have used prospective data but limited their focus to falls treated in emergency departments (Bleijlevens et al. 2010), falls among older women (Nachreiner et al. 2007), or falls that resulted in fracture (Luukinen et al. 2000) or hip fracture. (Norton et al. 1997, Allander et al. 1998).

This study used prospective, self-reported information about fall circumstances among a group of high risk older adults and examined the relationships between location, activity, direction of fall and subsequent injury.

Methods

The SAFE Study

This secondary analysis examined the circumstances and outcomes of falls among participants of the previously described Dane County (Wisconsin) Safety Assessment for Elders (SAFE) Research Study (Kiehn et al. 2009). This was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a community-based multifactorial falls intervention conducted from October 2002 to December 2007. Eligible participants were aged 65 and older, lived independently, and were at high risk of falling (defined as a person who, in the year before the SAFE study, had either experienced one fall with injury, two falls without injury, or one fall without injury and had balance problems.) People who were unable to give informed consent and who had no caregiver in their home to give consent for them were excluded.

Five hundred people were enrolled in the SAFE Study over a two year period and randomized to either treatment or control. The treatment group received an intervention that consisted of a multifactorial in-home falls assessment with recommendations, referrals for further care, and monthly telephone follow-up for one year. The intervention was provided by a physical therapist who had received two days of training regarding fall risk factors and interventions including those related to medications, low vision, and home and environmental changes. The control group received home safety education booklets and usual care. Participants were followed monthly for one year and 465 participants (93%) completed the one-year study.

Before randomization, a nurse went to each participant’s home and, after obtaining informed consent, collected baseline demographic and clinical data. Demographic information included age, gender, race, education, annual income, and living arrangement (live alone, with spouse, with family, or other). Baseline clinical data included cognition using the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ) (Pfeiffer 1975), activities of daily living (ADL) using the Barthel Index (Mahoney and Barthel 1965), and balance confidence using the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale (Powell and Myers 1995).

Falls were the primary outcome measure and were assessed prospectively for one year. An unintentional fall was defined for participants as, “An event which results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground or other lower level” (Gibson et al. 1987). Participants recorded all falls on a calendar (Tinetti et al. 1988) that they mailed to the Study Coordinator each month. In addition, participants kept monthly diaries to record falls circumstances and outcomes. All participants who indicated a fall on their calendar were contacted by telephone within one month and asked a series of questions about the circumstances and outcome of the fall. If a person was injured, he or she was asked specific questions about the type of injury and if he or she had sought medical care. So that researchers could better understand the circumstances, participants were asked to describe what happened at the time they fell, where they fell, their activity right before they fell, and in what direction they fell.

Falls that resulted from a violent blow, loss of consciousness, sudden onset of paralysis as in a stroke, or an epileptic seizure were excluded from the final data set (Gibson et al. 1987). Also excluded were falls that occurred in a hospital, nursing home or community-based residential facility.

Falls circumstances analysis

We reviewed the narrative descriptions of the circumstances for each fall and created categorical variables that identified the general location (i.e., home, outdoors, in a public building), specific place within the general location (e.g., living room, bedroom, sidewalk), activity at the time of the fall (e.g., walking, standing up), direction of the fall (i.e., forward, sideways, backward to sitting, backward and landing flat, straight down), and the attributed cause as reported by the participant (e.g., lost balance, tripped.) If information about any of these variables was not available in the narrative, it was coded as “Unspecified”.

All fall outcomes were based on self-report. We categorized a fall outcome as none if the participant reported no subsequent injury; “mild” if the person reported being injured but did not seek medical care; “moderate” if the person sought medical care for an injury other than a head injury or fracture, and “severe” if the person sought medical care for a self-reported head injury or fracture. We defined an injurious fall as one that resulted in any injury.

Data were analyzed using SAS (version 9.3). Chi-square statistics were used to test differences in categorical variables. We used a generalized linear mixed model that treated injury severity as a nominal three-level variable, (i.e., no injury, mild injury, and moderate or severe injury) to determine the odds ratios (OR) for circumstances associated with sustaining an injurious fall. The model took into account correlations between the falls of repeat fallers. The full model included age, gender, number of days in the study (excluding days spent in the hospital, nursing home, or community-based residential facility) (Tinetti et al. 1988) and the falls circumstances variables. The latter included the location of the fall, activity at the time of the fall, direction of fall, and attributed cause. Statistical significance was set at p < .05.

Results

Of the 465 SAFE study participants, 328 (70.5%) reported at least one fall during the one-year follow-up period (122 fell once, 69 fell twice, 49 fell three times, and 88 fell four or more times); they provided information about the circumstances of 1,172 falls.

The baseline characteristics of the 328 fallers are shown in Table 1. About half (48.2%) were between 75 and 84 years of age, almost three-quarters (72.3%) were female and 59.5 percent lived alone. The sample was 97.2 percent white, which reflected the catchment area population. Overall, the group had little cognitive impairment, as indicated by an average score on the SPMSQ of 0.8 ± 1.8 on a scale of 0–10 (maximum impairment = 10) (Pfeiffer 1975). The participants had minor limitations in their ADLs, with an average Barthel Activities Score of 88 ± 18 on a scale of 1–100 (maximum functional score = 100). (Mahoney and Barthel 1965) However, they had only a moderate level of confidence in being able to maintain their balance during activities, as shown by an average score on the modified ABC test of 6.0 ± 2.1 on a scale of 1–10 (maximum confidence score = 10) (Powell and Myers 1995).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 328 fallers aged 65 and older

| Demographic | %* |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 65–74 | 30.2 |

| 75–84 | 48.2 |

| 85+ | 21.6 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 72.3 |

| Race | |

| White | 97.2 |

| African–American | 1.0 |

| Other | 1.8 |

| Annual income | |

| 0–9,999 | 9.5 |

| 10,000–24,999 | 35.7 |

| 25,000–49,999 | 24.7 |

| 50,000+ | 18.0 |

| DK/Refused | 12.2 |

| Living arrangement | |

| Alone | 59.5 |

| With spouse | 30.8 |

| With family | 7.0 |

| Other | 2.7 |

| Years of school completed (mean ± SD) | 14.3 ± 4.0 |

| Clinical | Mean ± SD |

| Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ). (Maximum impairment score = 10)[Pfeiffer 1975) | 0.8 ± 1.8 |

| Barthel Activities of Daily Living (ADL) score, (Maximum functional score = 100) [Mahoney and Barthel 1965] | 88 ± 18 |

| Modified Activities–Balance Confidence (ABC) score. (Maximum confidence score = 10) [Powell and Myers 1995] | 6.0 ± 2.1 |

Rounding may result in totals slightly over or under 100%.

Injury severity differed by SAFE participant status. Intervention participants sustained 44.8% of all falls (525/1172) and 56.2% of the moderate or severe injuries (50/89) while control participants sustained 55.2% of all falls and 43.8% (39/89) of moderate or severe injuries. Although these differences were statistically significant (chi square p = .01), there was no protective effect of having been in the intervention group.

The general location of the fall, (e.g., inside their or another person’s home, outdoors, in a public building) did not differ by gender (chi square p = 0.15) or by their participant status in the SAFE Study (intervention or control) (chi square p = 0.14) (data not shown). Therefore, the falls were pooled in subsequent analyses. However, the location of the fall did differ by age group. People aged 85 and older were significantly more likely to fall inside their home than were younger people (age 65–74 [62.5%]; 75–84, [67.7%]; ≥85 [73.9%]) (chi square p = .03).

Table 2 shows the outcomes of 1,172 falls by a number of demographic and fall characteristics. Falls occurred most often among people aged 75 to 84 years. The proportions of mild compared to moderate or severe injuries were similar for persons 75 to 84 (47.8% mild vs. 43.8% moderate or severe). However, for people 85 and older, the greatest proportion of injuries were moderate or severe (18.9% mild vs. 34.8% moderate or severe). Women sustained 56.3 percent of the reported falls but experienced 75.3 percent of the falls that resulted in moderate or severe fall injuries.

Table 2.

Injury severity of 1,172 falls by age, gender, location, attributed cause, activity and direction of fall

| Injury severity*

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None

|

Mild

|

Moderate or severe

|

Total

|

|||||

| N = 782 | (%)** | N = 301 | (%) | N = 89 | (%) | N = 1172 | (%) | |

| Age group | ||||||||

| 65–74 | 316 | (40.4) | 100 | (33.2) | 19 | (21.4) | 435 | (37.1) |

| 75–84 | 333 | (42.6) | 144 | (47.8) | 38 | (43.8) | 515 | (43.9) |

| ≥85 | 133 | (17.0) | 57 | (18.9) | 31 | (34.8) | 221 | (18.9) |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Men | 386 | (49.4) | 104 | (34.6) | 22 | (24.7) | 512 | (43.7) |

| Women | 396 | (50.6) | 197 | (65.5) | 67 | (75.3) | 660 | (56.3) |

| Location | ||||||||

| Outside | 197 | (25.2) | 82 | (27.2) | 30 | (33.7) | 309 | (26.4) |

| In a public building | 57 | (7.3) | 21 | (7.0) | 2 | (2.3) | 80 | (6.8) |

| Inside the home | 528 | (67.5) | 198 | (65.8) | 57 | (64.0) | 783 | (66.8) |

| Activity | ||||||||

| Walking | 214 | (27.4) | 80 | (26.6) | 27 | (30.3) | 321 | (27.4) |

| Standing up | 100 | (12.8) | 25 | (8.3) | 8 | (9.0) | 133 | (11.3) |

| Stepping up or down (stairs/step/curb/ladder/stepstool) | 55 | (7.0) | 38 | 12.6 | 7 | (7.9) | 100 | (8.5) |

| Reaching or leaning | 61 | (7.8) | 12 | (4.0) | 4 | (4.5) | 77 | (6.6) |

| Turning or changing direction | 48 | (6.1) | 20 | (6.6) | 6 | (6.7) | 74 | (6.3) |

| Bending or pushing | 37 | (4.7) | 9 | (3.0) | 3 | (3.4) | 49 | (4.2) |

| Other specified | 212 | (27.2) | 102 | (33.9) | 26 | (29.2) | 340 | (29.0) |

| Not specified | 55 | (7.0) | 15 | (5.0) | 8 | (9.0) | 78 | (6.7) |

| Direction of fall | ||||||||

| Forward | 327 | (41.8) | 133 | (44.2) | 36 | (40.5) | 496 | (42.3) |

| Sideways | 134 | (17.1) | 86 | (28.6) | 20 | (22.5) | 240 | (20.5) |

| Backward to sitting | 174 | (22.3) | 27 | (9.0) | 5 | (5.6) | 206 | (17.6) |

| Backward and landing flat | 71 | (9.1) | 39 | (13.0) | 12 | (13.5) | 122 | (10.4) |

| Straight down | 17 | (2.2) | 2 | (0.7) | 2 | (2.3) | 21 | (1.8) |

| Other specified | 12 | (1.5) | 1 | (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 13 | (1.1) |

| Not specified | 47 | (6.0) | 13 | (4.3) | 14 | (15.7) | 74 | (6.3) |

| Attributed cause | ||||||||

| Lost balance, unsteady or wobbly | 259 | (33.1) | 87 | (28.9) | 23 | (25.8) | 369 | (31.5) |

| Trip, caught foot, clumsy or tangled feet | 208 | (26.6) | 100 | (33.2) | 26 | (29.2) | 334 | (28.5) |

| Slip | 69 | (8.8) | 23 | (7.6) | 8 | (9.0) | 100 | (8.5) |

| Legs or hip gave out, rubbery legs or leg weakness | 64 | (8.2) | 17 | (5.7) | 4 | (4.5) | 85 | (7.3) |

| Other specified | 96 | (12.3) | 45 | (15.0) | 13 | (14.6) | 154 | (13.1) |

| Not specified | 86 | (11.0) | 29 | (9.6) | 15 | (16.9) | 130 | (11.1) |

Mild: Reported injury but did not seek treatment; Moderate: Sought medical care for injuries excluding head injuries and fractures; Severe: Sought medical care for head injuries and fractures.

Rounding may result in totals slightly over or under 100%.

Of 389 falls that occurred outside the home, 309 were outdoors and 80 were in public buildings. Of falls that occurred outdoors, 31.7 percent occurred in areas characterized as a garden, lawn, or woods, 19.9 percent happened on outdoor stairs or steps, and 18.8 percent on sidewalks or driveways (data not shown). Of the 80 falls that occurred inside public buildings, 15.6 percent happened in stores, 11.7 percent in recreational settings, and 10.4 percent in hotels or motels (data not shown). Falls that caused moderate or severe injuries occurred most often while people were walking (30.3%) or when standing up (9.0%). However, 29.0 percent of all falls, regardless of outcome, happened while people were engaged in diverse “Other specified” activities, (e.g., cleaning, opening or closing doors, bathing, getting into or out of a car). The direction of the fall appeared to be associated with injury outcomes. The largest proportion of moderate or severe injuries occurred when falling forward (40.5%) and sideways (22.5 %) (Table 2). Falling backward to sitting or straight down resulted in the smallest proportion of moderate or severe injuries. People most often attributed their falls to either losing their balance (31.5 %) or tripping (i.e., catching their foot on something) (28.5 %), and only 8.5 percent of falls were attributed to slipping (i.e., sliding or losing their footing). However, no cause was given for 11.1 percent of falls.

Two thirds of falls (783 or 66.8 %) occurred inside the home. For each injury outcome, (i.e., no injury, mild injury, moderate or severe injury), we examined the distribution of falls within the main rooms of the home. After excluding unspecified locations, we found no statistical difference in the distributions for mild vs, moderate or severe injuries, so these injury categories were combined.

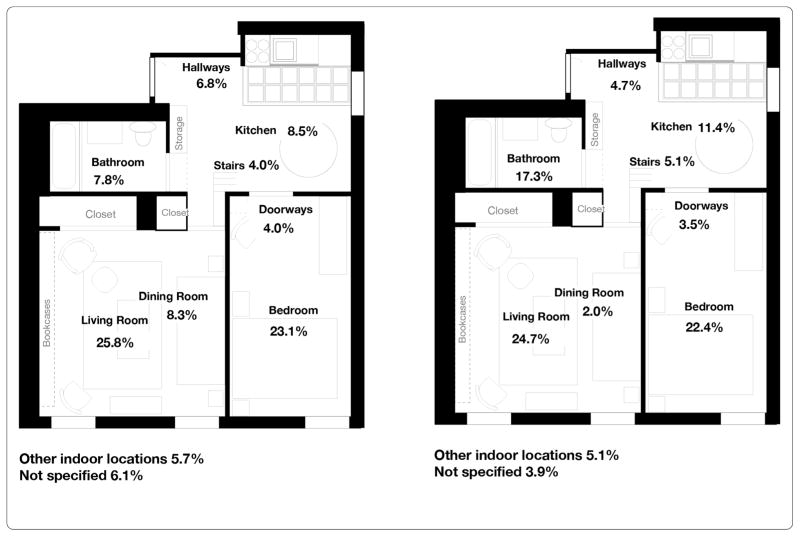

Figure 1a illustrates the distribution within the home of 5% 28 falls with no injury and Figure 1b shows the distribution of 255 falls with any (mild, moderate or severe) injury. Regardless of whether an injury occurred, the largest proportion of falls happened in the living room and bedroom. However, 41 of 528 (7.8%) of falls with no injury and 44 of 255 (17.3%) of falls with any injury occurred in the bathroom, a statistically significant difference (chi square p < .001).

Figure 1.

a. Distribution of 528 falls with no injuries that occurred inside the home. b Distribution of 255 mild, moderate, or severe fall injuries that occurred inside the home.

To assess the characteristics associated with sustaining an injurious fall, we used a generalized linear mixed model that included age-group, gender, location, number of days in the study, activity, attributed cause, and direction of fall (Table 3). Age-group, gender, and direction of fall were statistically significant. People aged 85 and older were twice as likely as people aged 65 to 74 to sustain a fall injury (p = .01) and women were twice as likely as men to be injured (p = .001).

Table 3.

Generalized linear mixed model* of characteristics significantly associated with injurious** falls among people aged 65 years and older

| Falls characteristic | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| 65–74 | Ref | ––– |

| 75–84 | 1.7 | 1.0–2.8 |

| ≥85 | 2.2 | 1.2–3.9 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | Ref | ––– |

| Female | 2.1 | 1.3–3.4 |

| Direction of fall | ||

| Backward to sitting | Ref | ––– |

| Backward and landing flat | 5.6 | 2.9–10.5 |

| Sideways | 4.6 | 2.6–8.0 |

| Forward | 3.3 | 2.0–5.7 |

| Straight down | 1.7 | 0.4–6.9 |

| Other specified | 0.6 | 0.1–6.1 |

| Not specified | 5.1 | 2.4–10.9 |

Model included age-group, gender, location, number of days in the study, activity, attributed cause, and direction of fall.

Mild: Reported injury but did not seek treatment; Moderate: Sought medical care for injuries excluding head injuries and fractures; Severe: Sought medical care for head injuries and fractures.

The likelihood of an injury was strongly associated with the direction of the fall. For example, falling backward and landing flat was about five and a half times more likely to result in an injury compared to falling backward into a sitting position (i.e., “Her leg gave out and she fell and landed on her bottom”). Similarly, an injury was about four and a half times more likely to result from falling sideways and three times more likely from falling forward. In addition, falls without a specified direction were significantly more likely to result in an injury, compared to falling backward into a sitting position.

When we limited the model to the 783 falls that occurred inside the home and included specific locations (i.e., living room, bedroom, kitchen, bathroom, all other locations combined), we saw similar results (Table 4). Older age, female gender, and direction of the fall again were significantly associated with the likelihood of sustaining an injury. In addition, compared to falls in the living room, falls in the bathroom were almost two and a half times more likely to result in an injury (OR = 2.4, 95% CI = 1.2–4.9).

Table 4.

Generalized linear mixed model* of characteristics significantly associated with injurious** falls in the home among people aged 65 years and older

| Falls characteristic | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| 65–74 | Ref | ––– |

| 75–84 | 2.1 | 1.1–3.8 |

| ≥85 | 2.1 | 1.0–4.3 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | Ref | ––– |

| Female | 2.0 | 1.1–3.5 |

| Location | ||

| Living room | Ref | ––– |

| Bedroom | 1.1 | 0.6–1.9 |

| Kitchen | 1.4 | 0.7–2.7 |

| Bathroom | 2.4 | 1.2–4.9 |

| Other specified | 0.7 | 0.4–1.3 |

| Direction of fall | ||

| Backward to sitting | Ref | ––– |

| Backward and landing flat | 4.8 | 2.2–10.5 |

| Sideways | 3.0 | 1.5–5.9 |

| Forward | 2.2 | 1.2–4.3 |

| Straight down | 1.6 | 0.3–7.9 |

| Other specified | 0.4 | 0.3–6.9 |

| Not specified | 5.0 | 2.0–12.6 |

Model included age-group, gender, room, number of days in the study, activity, attributed cause, and direction of fall.

Mild: Reported injury but did not seek treatment; Moderate: Sought medical care for injuries excluding head injuries and fractures; Severe: Sought medical care for head injuries and fractures.

Discussion

This study investigated 1,172 falls sustained by 328 community-dwelling older adults at high risk of falling, who had fallen during the course of a year, and examined the circumstances that resulted in no, mild, and moderate or severe injuries. Using a generalized linear mixed model, we identified three significant variables: age-group, gender and direction of the fall. Being age 85 or older or being female doubled the likelihood that a fall would result in an injury. Compared to falling backward into a sitting position, injuries were most likely to result from falling backward and landing flat, falling sideways and, to a somewhat lesser extent, falling forward. When we looked only at falls that occurred inside the home, falls in the bathroom were more than twice as likely to result in an injury, compared to falls in the living room.

It is well documented that women are more likely than men to sustain nonfatal fall injuries (CDC 2013). In 2011, after adjusting for age, the fall injury rate for women treated in U.S. emergency departments was 46 percent higher than for men (CDC 2013). In a population-based study of gender differences, Stevens and Sogolow (2005) found that nonfatal fall injury rates for women were 40 to 60 percent higher than for men of comparable age. For both men and women, fall injury rates increased sharply with age with the greatest increase occurring after age 80 (CDC 2013).

In this study, about 26 percent of falls occurred outdoors compared to as much as 50 percent reported in other studies (Kelsey et al. 2010, Bergland et al. 2003). Research has demonstrated that healthy active older adults are more likely to fall outdoors (Bleijlevens et al. 2010, Kelsey et al. 2012, Manty et al. 2009). Our participants were at high risk for falling, had some limitations in ADLs as well as limited self-confidence about falling, so we would expect to see a lower percentage of falls outdoors.

We identified locations within the home where fall injuries occurred, an approach recommended by Runyan et al. (2002) to improve data collection of home injuries. We found that 17 percent of injurious falls, compared to eight percent of non-injurious falls, occurred in bathrooms. The likelihood of sustaining a fall injury in the bathroom was almost two and a half times that of experiencing a fall injury in the living room. It is reasonable that falling in a small room with porcelain surfaces, metal fixtures, and hard floors would be more likely to result in an injury than falling in a larger area with upholstered furniture and/or carpeted surfaces.

In a cross-sectional study, Bleijlevens et al. (2010) assessed 333 older adults treated in emergency departments after a fall and found that about ten percent of fall-related fractures were associated with going to, going from, or being in the bathroom. These fallers also were the most inactive. Similarly, an analysis of nonfatal bathroom injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments found that about 81 percent of these injuries were caused by falls. The highest injury rate was among people aged 65 and older, and injuries occurred most frequently when people were in or getting out of the tub or shower, and when they were standing up, sitting down, or using the toilet (Stevens et al. 2011).

This is the first study to show that, among falls inside the home, those in the bathroom were most likely to result in an injury. These findings support the need for improving safety in the bathroom. This may include, 1) getting assistance from another person for bathing; 2) adopting safer methods when carrying out activities in the bathroom (e.g., wearing shoes with non-slip soles, storing toiletries on easy-to-reach shelves, using an assistive device safely), and 3) using and/or installing safety equipment (e.g., non-skid tub or shower mats, grab bars both inside and outside the tub or shower and around the toilet, and raised toilet seats).

An effective intervention, shown in a number of RCTs to reduce falls in the home, to is to have an occupational therapist (OT) conduct an in-home safety assessment. (Stevens 2010) This may be covered by Medicare if the person previously has been injured in a fall. An OT can evaluate a person’s ability to perform daily activities in their home, teach the individual how to accomplish these activities more safely, and/or make suggestions for home modifications to reduce potential fall hazards. Such behavioral and environmental changes can prevent falls and subsequent injuries. In addition, depending on a person’s level of risk, fall prevention interventions that have been shown in RCTs to effectively reduce falls include individualized exercises prescribed by a physical therapist; home-based progressive exercise programs, such as the Otago Program; and community exercise programs that improve balance and lower body strength, such as Tai Chi. (Rose 2008, Sherrington et al. 2008, Stevens 2010)

We found a strong association between the direction of the fall and the likelihood of injury. Others have not seen this relationship (Demura et al. 2012), but these researchers did not distinguish falls backward into a seated position (low risk for injury) from those backward and landing flat (higher risk for injury). In our study, falling backward and landing flat was about five and a half times as likely to result in an injury, and falling sideways was four times as likely, compared to falling backward and landing in a sitting position. Falling backward and landing flat may result in head injury while falling sideways can cause hip fracture. (Hayes et al. 1993) These severe injuries often result in long-term functional impairment, nursing home admission and increased mortality (Magaziner et al. 1990, Thompson et al. 2006, Penrod et al. 2008). Of 1,172 reported falls in the current study, only 29 (2.5%) caused fractures or head injuries. Therefore, we were not able to assess the relationship between these specific types of serious injuries and the direction of the fall.

One-third of falls in this study were attributed to tripping or slipping. Promising falls interventions include techniques for teaching individuals in laboratory settings how to regain their balance (Pai and Bhatt 2007, Mansfield et al. 2010, Wang et al. 2011), although these may not be practical on a population level. Recent work with healthy older adults showed that under laboratory conditions, training that used surface perturbations to simulate slipping and induce backwards falls improved both proactive (pre-slip) and reactive (post-slip) balance strategies. The result was fewer backward falls. (Mansfield et al. 2010, Wang et al. 2011)

Grabiner et al. (2012) explored whether task-specific training could reduce trip-related falls among 52 healthy middle-aged and older women. Using a treadmill to simulate tripping, the 22 women who had received training had significantly fewer falls (4.5%) than the 30 control women (26.6%). However, it is not known if laboratory training would benefit less healthy older adults or if it would translate into fewer falls from unexpected trips and slips in real life settings. Further research is needed to determine practical interventions that can decrease falls from tripping and slipping.

Using a multivariate model, we did not find an association between self-reported activity and likelihood of a fall injury. Falls occurred most often when a person was walking, a finding that has been reported previously. (Berg et al. 1997, Nachreiner et al. 2007, Milat et al. 2011) However, it is difficult to compare studies because the activities described often depend on the population (e.g., healthy vs. less-healthy older adults) and the location (e.g., outdoors vs. indoors) (Kelsey et al. 2010, Kelsey et al. 2012). We categorized each activity based only on what was in the person’s recorded narrative. We were unable to classify many of the “other specified” activities because it would have required making assumptions about the underlying activity, (e.g., assuming that “cleaning” was essentially the same activity as “reaching”.) Some participants described a sequence of events in which one activity lead to subsequent events that culminated in a fall, which made it difficult to establish the activity at the time of the fall. Similar issues made it difficult to classify the attributed causes of falls, (e.g., trip, slip, lost balance, legs gave out, etc.) In addition, the causes of almost one-third of falls were nonspecific and attributed only to a loss of balance.

This study has several limitations. There was inadequate detail available about the circumstances of some falls, although there had been a concerted effort to collect these data. Although the study excluded falls due to syncope, some such falls may have been included if the participant did not remember experiencing a loss of consciousness. (Shaw and Kenny 1997) The direction of six percent of falls was unspecified and these were more likely to be injurious falls. For participants who were hospitalized following a fall injury and then admitted to a rehabilitation facility, there was often a delay in obtaining information about the fall. This may have resulted in poorer recall of the fall circumstances. Also, this study included people at high risk for falls and the results cannot be generalized to all community-dwelling older adults.

A major strength of this study is that data about falls were collected prospectively using monthly calendars, a method that is considered the gold standard (Ganz et al. 2005, Hauer et al. 2006). Obtaining fall data retrospectively can result in underreporting. In one study, two-thirds of people who had sustained an injurious fall did not recall the injury when questioned six months later (Mackenzie et al. 2006). Our study used monthly calendars that were mailed each month to the study coordinator. All participants who reported a fall were contacted by telephone to ascertain the circumstances and extent of any injury. Telephone interviews for falls circumstances have demonstrated good agreement with face-to-face interviews (Mackintosh et al. 2009).

Conclusions

This study of older adults at high risk for falls found that most falls occurred at home and that women and people aged 85 and older were most likely to be injured. There was a greater likelihood of injury from falling forward, sideways, and backward and landing flat, compared to falling backward to sitting. And finally, for falls inside the home, there was a significantly greater likelihood of sustaining an injury in the bathroom compared to the living room. These results support the need to promote safety modifications such as grab bars and may indicate a need for assistance with bathing. These findings will help clinicians tailor fall prevention for their patients and have practical implications for retirement and assisted living communities as well as for community-based fall prevention programs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ronald Gangnon for organizing and managing these data, Likang Xu for his help in conducting and interpreting the statistical analyses, and Robin Lee and Tamara Haegerich for their thoughtful comments and suggestions.

This research was supported in part by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and CDC.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JS provided the study conception and design, supervised the data analysis, interpreted the results, and prepared the manuscript. JM provided the data, contributed to the analysis plan, interpreted the results, and reviewed the manuscript. HE performed the computer programming and data analysis, contributed to the manuscript, and provided critical review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Allander E, Gullberg B, Johnell O, et al. Circumstances around the fall in a multinational hip fracture risk study: a diverse pattern for prevention. Accid Anal Prev. 1998;30(5):607–16. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(98)00016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg WP, Alession HM, Mills EM, et al. Circumstances and consequences of falls in independent community-dwelling older adults. Age Ageing. 1997;26:261–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.4.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergland A, Jarnlo GB, Laake K. Predictors of falls in the elderly by location. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15:43–50. doi: 10.1007/BF03324479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleijlevens MHC, Diederiks JPM, Hendriks MRC, et al. Relationship between location and activity in injurious falls: an exploratory study. [Accessed 25 June 2013];BMC Geriatr. 2010 10:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-10-40. Available at: http:www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2318/10/40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. [Accessed 13 June];Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) 2013 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/

- Demura S, Yamada T, Kasuga K. Severity of injuries associated with falls in the community dwelling elderly are not affected by fall characteristics and physical function level. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55:186–9. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz DA, Higashi T, Rubenstein LZ. Monitoring falls in cohort studies of community–dwelling older people: effect of the recall interval. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:2190–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson MJ, Andres RO, Isaacs B, et al. The prevention of falls in later life: a report of the Kellogg International Work Group on the prevention of falls by the elderly. Dan Med Bull. 1987;34:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabiner MD, Bareither ML, Gatts S, et al. Task-specific training reduces trip-related fall risk in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(12):2410–4. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318268c89f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauer K, Lamb SE, Jorstad EC, et al. Systematic review of definitions and methods of measuring falls in randomised controlled fall prevention trials. Age Ageing. 2006;35:5–10. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes WC, Myers ER, Morris JN, et al. Impact near the hip dominates fracture risk in elderly nursing-home residents who fall. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993;52(3):192–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00298717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey JL, Berry SD, Procter-Gray E, et al. Indoor and outdoor falls in older adults are different: the maintenance of balance, independent living, intellect, and zest in the elderly of Boston study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(11):2135–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey JL, Procter-Gray E, Hannan MT, et al. Heterogeneity of falls among older adults: implications for public health prevention. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:2149–56. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn KA, Mahoney J, Jones AN, et al. Vitamin D supplement intake in elderly fallers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(1):176–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luukinen H, Herala M, Koski K, et al. Fracture risk associated with a fall according to type of fall among the elderly. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:631–4. doi: 10.1007/s001980070086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie L, Byles J, D’Este C. Validation of self–reported fall events in intervention studies. Clin Rehabil. 2006;2:331–9. doi: 10.1191/0269215506cr947oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh S, Fryer C, Hill K. Telephone and face-to-face interviews generate similar falls circumstances information from community-dwelling adults with stroke. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2009;33(3):295–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2009.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaziner J, Simonsick EM, Kashner TM, et al. Predictors of functional recovery one year following hospital discharge for hip fracture: a prospective study. J Gerontol. 1990;45:M101–7. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.3.m101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield A, Peters AL, Liu BA, et al. Effect of a perturbation-based balance training program on compensatory stepping and grasping reactions in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2010;90:476–91. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manty M, Heinonen A, Viljanen A, et al. Outdoor and indoor falls as predictors of mobility limitation in older women. Age Ageing. 2009;38:757–61. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milat AJ, Watson WL, Monger C, et al. Prevalence, circumstances and consequences of falls among community–dwelling older people: results of the 2009 NSW Falls Prevention Baseline Survey. N S W Public Health Bull. 2011;22(4):43–8. doi: 10.1071/NB10065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M, Osborne D, Hill K, et al. Predisposing factors for occasional and multiple falls in older Australians who live a home. Aust J Physiother. 2004;50:153–9. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachreiner NM, Findorff MJ, Wyman JF, et al. Circumstances and consequences of falls in community–dwelling older women. J Womens Health. 2007;16:1437–46. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton R, Campbell AJ, Lee-Joe T, et al. Circumstances of falls resulting in hip fractures among older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:1108–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai YC, Bhatt TS. Repeated-slip training: an emerging paradigm for prevention of slip-related falls among older adults. Phys Ther. 2007;87:1478–91. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrod JD, Litke A, Hawkes WG, et al. The association of race, gender, and comorbidity with mortality and function after hip fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(8):867–72. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.8.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell LE, Myers AM. The activities-specific balance confidence (ABC) scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50A:M28–34. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.1.m28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose DJ. Preventing falls among older adults: no “one size suits all” intervention strategy. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45(8):1153–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR. The epidemiology of falls and syncope. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18:141–58. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(02)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan CW, Perkis D, Marshall SW, et al. Unintentional injuries in the home in the United States– Part II: morbidity. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(1):80–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw FE, Kenny RA. The overlap between syncope and falls in the elderly. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73(864):635–9. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.73.864.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington C, Whitney JC, Lord SR, et al. Effective exercise for the prevention of falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2234–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JA, Haas EN, Haileyesus T. Nonfatal bathroom injuries among persons aged >15 years–United States, 2008. J Safety Res. 2011;42:311–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JA, Sogolow ED. Gender differences for non-fatal unintentional fall related injuries among older adults. Inj Prev. 2005;11(2):115–9. doi: 10.1136/ip.2004.005835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JA. Compendium of effective fall interventions: what works for community-dwelling older adults. 2. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson HJ, McCormick WC, Kagan SH. Traumatic brain injury in older adults: epidemiology, outcomes and future implications. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1590–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1701–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812293192604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tromp AM, Pluijm SMF, Smit JH, et al. Fall-risk screening test: a prospective study on predictors for falls in community-dwelling elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(8):837–44. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00349-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TY, Bhatt T, Yang F, et al. Generalization of motor adaptation to repeated-slip perturbation across tasks. Neuroscience. 2011;180:85–95. doi: 10.1186/2197-1714-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]