Synopsis

Accurately measuring the complex motor behaviors of the gastrointestinal tract has tremendous value for the understanding, diagnosis and treatment of digestive diseases. This review synthesizes the literature regarding current tests that are used in both humans and animals. There remains further opportunity to enhance such tests, especially when such tests are able to provide value in both the preclinical and the clinical settings.

Introduction

The ability to assess accurately the complex motor functions of the gastrointestinal tract has been of tremendous value to understanding and treating digestive diseases. Unlike other smooth or cardiac muscle organ systems with relatively more rhythmic and patterned motor behavior, the complexity of the diverse motor behaviors of the alimentary canal have made the development and use of clinical and preclinical tests of gastrointestinal motor function a great challenge. It is perhaps this complexity, as well as the importance of gastrointestinal function to overall health and well-being, that have fascinated early physiologists and continue to push modern physiologists and clinical diagnosticians to develop new and more accurate measurements of motility. It is also because of this complexity that the standardization of these measures presents hurdles to broad adoption and that the measurements of the more complex motility functions remain restricted mainly to tertiary referral centers.

Assessing motility in humans has three obvious values. First, standardized clinical tests have diagnostic value in stratifying patients who present with a relatively limited repertoire of symptoms in the complex multifactorial digestive diseases into more manageable subsets and in the identification of underlying pathophysiology. Second, these clinical tests provide measures that can be used to objectively determine the efficacy of therapies for digestive diseases in the clinic and during drug and device development in clinical trials. Third, motility measurements in humans have value in broadening our understanding of the physiology and pathophysiology of the gastrointestinal tract in order to generate new hypotheses and new drug targets to understand and treat digestive diseases.

Motility tests in non-human animals also have value that parallels the value of tests for humans. First, animals serving as companions, or in labor, sports and food production industries benefit from the diagnostic value of accurate motility tests in veterinary medicine. Second, motility tests provide the basis for objective measures to assess the efficacy and dosing guidelines of new therapies in preclinical drug and device development. Third, animal models provide the basis for understanding the physiology and pathophysiology of the gastrointestinal tract. This latter value has historically been greater in non-human animals because of the ability to conduct terminal or ex-vivo experiments followed by anatomical or biochemical assessments that are not possible in humans.

The purpose of this review is to critically assess the current state of motility tests (listed in Table 1, and examples given in Figure 1), based on these values in both humans and non-humans. It is organized by region of the alimentary canal in an oral to anal direction, followed by measures of whole gut transit. The hope is that such juxtaposition of human and non-human tests will enlighten both the benefit and deficiencies in each in order to aid in the de novo or cross-development of new motility tests.

Table 1.

Listing of tests currently available for measuring gastrointestinal and colonic motility

| FUNCTION | Tests Available |

|---|---|

| Gastric Capacity or Accommodation | Barostat balloon measurements Nutrient drink test SPECT Ultrasonography MRI High resolution intra-gastric manometry |

| Gastric Emptying |

Scintigraphy Wireless pH and motility capsule Stable Isotope Breath Tests |

| Gastric Transit in Preclinical Studies | Analysis of gastric contents Stable isotope breath tests Scintigraphy |

| Small Bowel Transit | Breath hydrogen tests Stable isotope breath tests Scintigraphy Wireless pH and motility capsule |

| Whole Gut Transit in Preclinical Studies | Non-absorbable marker such as carmine red Scintigraphy using steel beads and barium in mice |

| Colonic Transit |

Radiopaque markers Scintigraphy Wireless pH and motility capsule |

| Gastrointestinal, Colonic and Anorectal Contractility |

Antropyloroduodenal manometry Wireless pH and motility capsule Colonic phasic contractility (including high resolution manometry) and tone Anorectal manometry |

| Colonic Motility and Transit in Preclinical Studies | Bead expulsion Colonic manometry (including high resolution manometry) Scintigraphy |

| New MRI applications | All the above functions as well as anorectal and pelvic floor motion and anatomical integrity |

Tests with strongest validation or most widely available and used are indicated in italics.

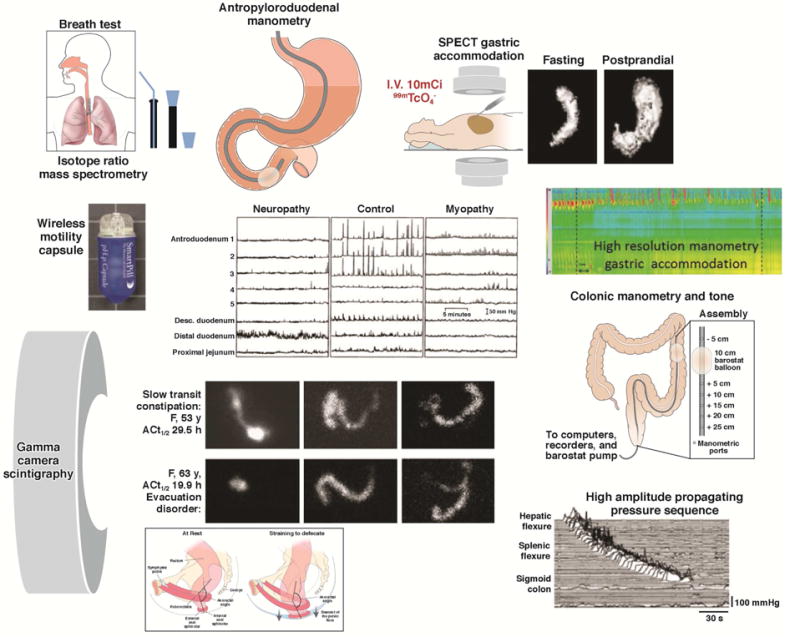

Figure 1.

Examples of the wide range of motility measurements available for human studies: stable isotope breath test; scintigraphic transit; intraluminal manometry by perfused manometers or strain gauges on tubes or wireless capsules; measurement of gastric capacity and accommodation by SPECT or high resolution manometry.

In the interest of brevity, we do not describe tests of esophageal motility here. High resolution manometry has become the diagnostic tool of choice, about which many recent reviews have been published.1–3

Tests to Evaluate Gastric Capacity and Accommodation

One of the principal functions of the proximal stomach is the storage of ingested food. The gastric fundus and body are able to accommodate large volume changes, while maintaining a relatively low intragastric pressure. Altered gastric tone and distensibility may occur in several disease states including tumor infiltration, vagal dysfunction, and post-gastric surgery status, and in up to 40% of patients with functional dyspepsia.4

Barostat Balloon Measurements

The gold standard for the measurement of tone in hollow organs was the barostat,5 which estimates changes in tone by the change of volume of air in an infinitely (typically polyethylene) compliant balloon maintained at a constant pressure to maintain the balloon in apposition with the stomach lining. The barostat maintains the constant pressure by infusion or aspiration of air in response to relaxation or contraction of stomach tone. This method is not used extensively in clinical practice, as it requires intubation and results in stress and discomfort during the tests, which may last 3 hours or longer.6

Development and validation studies of the barostat to measure compliance, tone, and postprandial accommodation in the dog were performed by Azpiroz and Malagelada.5 Since then, the barostat has been used extensively in animals including cats,7 rabbits,8 pigs,9 horses,10 rats8,11 and mice.12

Satiation or Nutrient Drink Test

The nutrient drink test has been proposed as a surrogate method for estimating gastric volumes. In this test, a standardized liquid nutrient drink, such as Ensure® (Ross Products, Division of Abbott Laboratories, Columbus, OH; 1kcal/mL), is ingested at a standard rate of 30mL per minute, and the volume to normal fullness and the maximum tolerated volume are recorded as measures of satiation. Postprandial symptoms of nausea, fullness, bloating, and pain are measured 30 minutes after the meal.13 Tack et al. suggested that a high-caloric, slowly administered drinking test compared favorably with the barostat in predicting impaired gastric accommodation, especially in patients with maximum tolerated volume <750kcal.14 Because of the obvious limitations of feedback regarding sensory experiences, there are no reports of the use of nutrient drink tests in non-human animals.

Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT)

SPECT imaging has been extensively validated in vitro and in vivo for the measurement of gastric volumes during fasting and postprandially in humans, including comparison to the barostat.15–17 After intravenous administration of 10mCi 99mTc-pertechnetate, a substrate for the sodium/iodide symporter (NIS) that is accumulated and secreted into the lumen by parietal and mucin-secreting cells of the gastric mucosa, tomographic images of the stomach are acquired with the patient supine using a large field-of-view, dual-headed gamma camera. From the transaxial images of the stomach, 3-dimensional images are reconstructed using a commercially available software analysis program that is used for other 3-dimensional volume rendering with transaxial imaging (e.g. CT, MRI) and total gastric volume measured during fasting and during the first 10 minutes following a standard liquid nutrient meal (300mL Ensure®). This allows reconstruction of the stomach based on the location of the mucosal layer, and the estimated volume serves as a surrogate for the internal volume of the stomach. SPECT demonstrates effects of disease on post-meal gastric accommodation and effects of medications such as nitrates, erythromycin, GLP-1, and octreotide18,19 in health and diseases such as diabetes, fundoplication, and functional dyspepsia.20,21

Intra- and inter-individual coefficients of variance in postprandial and accommodation volumes by SPECT were not significantly different and ranged from 16 to 22%.22 The effects of liquid and solid equicaloric meals on gastric volumes have been described, and measurements of gastric volume with the same caloric liquid meal an average of 9 months apart showed a coefficient of variation of 10%.23

It is also possible to simultaneously measure gastric emptying and volume.24,25 The noninvasive nature of the method is attractive and is used extensively at Mayo Clinic in research and practice, especially in suspected disorders of gastric accommodation such as dyspepsia. However, the test involves radiation exposure, and SPECT equipment and the 3-dimensional reconstruction and volume rendering are not widely available. Another potential pitfall is that the resolution of the imaging does not equal that of CT or MRI.

Application in animal studies

While NanoSPECT-CT of gavaged technetium-labeled activated charcoal diethylene triaminepentaacetic acid (99mTc-Ch-DTPA) has been used to assess gastrointestinal transit in mice26 to our knowledge SPECT imaging has not been used to assess gastric accommodation specifically in non-human animals. Given the rapidly advancing use of 99mTc-pertechnetate and other NIS substrates in numerous animal models27,28 as well as descriptions of methods to circumvent the high stomach signal that confounds such studies,29 it is reasonable to assume that this well-validated approach to assess gastric accommodation in humans can easily be reverse translated for use in preclinical studies.

Ultrasonography

Imaging-based methods to measure gastric volume include 3-dimensional reconstruction of images acquired by ordinary ultrasonography assisted by magnetic scan-head tracking.30,31 Thus, an outline of the total stomach volume visualized after ingestion of a liquid meal (that serves as a contrast medium)32 has been applied in adolescents and compared with simultaneously measured gastric volumes by SPECT.33

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

The first application of MRI utilizing Spin Echo T1-weighted imaging sequence addressed the volume of the stomach during fasting, but not in the postprandial period.34 Volumes measured with MRI and barostat differ significantly, as the barostat measures only the proximal stomach, whereas MRI records entire stomach volume; however, there was a statistically significant correlation between the two methods, and MRI was also able to demonstrate volume effects induced by glucagon (increase) and erythromycin (decrease).

MRI, using 3-dimensional gradient echo and 2-dimensional half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin echo (HASTE) sequences,35 has been used to measure postprandial gastric volume change, which exceeded the ingested meal volume by 106±12mL (SEM). The advantage of MRI over SPECT is the ability to distinguish air from fluid under fasting and postprandial conditions respectively. MRI also showed that the postprandial volume excess mainly comprised air (61±5mL), which was not significantly different when the volume ingested was ingested in 30 or 150mL aliquots. Fasting and postprandial gastric volumes measured by MRI were generally reproducible within subjects. Gastric volumes measured by SPECT were higher than MRI, reflecting the fact that SPECT reconstruction includes the volume occupied by the imaged gastric wall. While MRI has many advantages, including lack of radiation exposure, it is not widely used to measure gastric accommodation in clinical practice or research.

High Resolution Intra-gastric Manometry

Using a high resolution manometry catheter, which is typically used for esophageal motility measurements, Janssen et al. showed that, during nutrient drink ingestion, there is a reduction in intraluminal pressure that provides a less invasive alternative to the barostat for the assessment of gastric accommodation.36 The method has also been used to demonstrate pharmacological effects, such as with peppermint oil37 and liraglutide.38

Gastrointestinal and Colonic Transit

Gastric Emptying

Scintigraphy

Gamma camera scintigraphy is the most widely used test for the assessment of gastric motility; it provides a direct, noninvasive quantification of gastric emptying.39 A simplified protocol with imaging at 1, 2, and 4 hours with a standard meal was first proposed at Mayo Clinic,40 and a variation was subsequently validated in a large multinational study in 123 subjects41 and was adopted by the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine.42 A standard, 2% fat meal consists of 4 ounces of Eggbeaters® or equivalent egg white substitute, 2 slices of bread, strawberry jam (30g), and 120mL water (total 240kcal) and is radiolabeled with 0.5–1mCi 99mTc-sulfur colloid. This is a relatively small meal which may not reliably induce symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia, though it is useful for diagnosing gastroparesis.

The Mayo Clinic method uses two natural eggs and contains 30% of the calories as fat (total 320kcal). The test meal determines the rate of emptying,43 and normal values are essential for interpretation of the test when performed clinically; thus, Mayo Clinic published data from 319 healthy controls.44 There is significant intra-individual variation in gastric emptying rates of 12–15%, even in healthy individuals.44,45 The performance characteristics of the 30% fat, 320kcal meal have been documented.44

The main indications for use of this test are the investigation of unexplained nausea, vomiting, and dyspeptic symptoms; screening for impaired gastric emptying in diabetic patients being considered for incretin treatment to enhance glycemic control (e.g., pramlintide and GLP-1 agonists); and assessment of patients with suspected diffuse gastrointestinal motility disorder in combination with small bowel and colonic transit.

In human research, the gastric emptying test is used to understand the pathophysiology of symptoms or in the development of pharmacological agents. There is a vast literature on the use of radioscintigraphy to measure gastric emptying in large animals. The first application documented the effects of vagotomy and carbachol on gastric emptying in dogs.46

Wireless pH and motility capsule

These non-digestible wireless capsules can measure pH, pressure, and temperature throughout the gastrointestinal tract. The abrupt change in pH from the gastric acidic milieu to the almost alkaline duodenum is usually associated with antral phasic contractions of the migrating motor complex (MMC), and it signals that the capsule has left the stomach.47 When taken with a meal, the capsule generally empties from the stomach after liquids and triturable solids have emptied, usually with the phase III of the MMC or, in about one-third of cases, with high amplitude, antral contractions.48

Patients ingest the capsule with a standard meal and, from 6 hours after capsule ingestion, patients can engage in normal daily activity, including ad libitum feeding. The wireless capsule acquires data continuously for up to 5 days, and this permits calculation of gastric, small bowel, colon, and whole gut transit. These wireless capsules also measure intraluminal pressure. In validation studies conducted with simultaneous gastric emptying by scintigraphy in healthy subjects and patients with gastroparesis,49 the gastric emptying time for the capsule and the scintigraphic gastric emptying time at 4 hours were significantly correlated (r=0.73), and the capsule discriminates between normal or delayed gastric emptying with a sensitivity of 0.87 at a specificity of 0.92.49 The advantages of the motility capsule are that the study can be conducted anywhere, lack of radioactivity, and ability to determine small bowel, colon, and whole gut transit times, as well as contractility.50–52 The wireless motility capsule is also capable of identifying effects of pharmacological agents on gastric contractility.53

Stable isotope breath tests

These tests evaluate gastric emptying noninvasively and without radiation hazard. 13C-isotope can be incorporated into components of a solid meal (e.g. the medium-chain fatty acid, octanoic acid, or the blue-green algae, Spirulina platensis) or in a liquid meal (13C-acetate) to assess gastric emptying of liquids. After ingestion, the solid meal is triturated and emptied by the stomach, digested, and absorbed in the proximal small intestine, metabolized by the liver and 13C02 excreted by the lungs, resulting in a rise in expired 13CO2 over baseline. The test and breath sample collection can occur at the point of care. The rate limiting step in 13CO2 excretion is gastric emptying of the meal.

In studies comparing 13C gastric emptying breath test (GEBT) performed simultaneously with scintigraphy, the GEBT provided accurate assessment of the gastric emptying of solids with coefficient of variation comparable to scintigraphy.45 In addition, 13C-spirulina GEBT documented accelerated or delayed gastric emptying induced with erythromycin or atropine respectively.54 The 13C-spirulina GEBT was approved by the FDA in 201555 based on a clinical study using data from 115 participants who would typically undergo a gastric emptying test showing that GEBT results agreed with scintigraphy results 73–97% of the time when measured at various time points during the test.56 Pitfalls include potential loss of accuracy in patients with diseases involving the intestinal mucosa, pancreas, liver, and respiratory system.

Gastric Emptying Studies in Non-Human Animals

Acute gastric emptying study by analysis of gastric contents

The long history and vast number of physiological and preclinical drug development studies using timed endpoint analysis of gastric contents following gavage or ingestion of a labeled or visually detectable and quantifiable meal to study gastric emptying are too numerous to reproduce in this short review. The approach is precise and inexpensive because, rather than relying on indirect measurements, the percentage of the meal remaining in the stomach can be directly calculated. Therefore, the approach remains the standard by which preclinical validation studies of novel tests of gastric emptying are compared. Relatively recent advancements in this approach have been the development of new tracers to increase the sensitivity of labeled meal detection as well as the detection of the labeled meal throughout the gastrointestinal tract to assess overall transit as measured by geometrical center,57,58 rather than percent emptied or leading edge. These new tests that define the geometric center and segment distribution can also be used to study whole gut transit.

Longitudinal gastric emptying studies

The advent of longitudinal studies in mice that required repeated measures of gastric emptying during disease development or therapy has led to the use of gastric emptying tests developed for humans in preclinical models. In these studies, the need for noninvasive, repeatable measures outweighs the relatively low inter-individual variability and cost of endpoint studies. These tests include scintigraphy59,60 and the 13C-octanoic acid GEBT.61,62 The 13C-octanoic acid GEBT has also been validated for measurement of gastric emptying in horses,63,64 cattle,65 dogs,66,67 and rats.68 In addition, in non-obese diabetic LtJ mice, a model of type 1 diabetes, the expected effects of bethanechol and atropine were demonstrated.62 These gastric emptying tests developed in humans and now used routinely in preclinical studies that can be directly translated into clinical trials are the clearest example of the benefit of bedside-to-bench-to-bedside approach, and should serve as a model for other motility tests that are presented in this review.

Gamma camera scintigraphy has been validated for use in small animals; thus, awake mice were accustomed to light restraint and to eating cooked, egg white (0g fat), whole egg (0.10g fat/g), or egg yolk (0.31g fat/g). Gastric emptying of each diet was measured by labeling the test meals with 99mTc-mebrofenin and using a conventional gamma camera equipped with a high-resolution, parallel-hole collimator. This method has been used to document the effects of devazepide (a CCK-A receptor antagonist)60 botulinum toxin injection into the antral wall in knockout animals and in pharmacological modulation,69,70 and the role of inflammation and novel therapies for postoperative ileus in animal models.71,72

Recent advances in ultrasound research in non-human animals have suggested that clinical tests using this noninvasive approach may soon be in development.73,74

Orocecal or Small Bowel Transit

Breath Hydrogen Tests

The breath test is based on the presumption that the hydrogen excreted in the breath is the product of colonic bacterial fermentation of unabsorbed carbohydrates ingested orally. Lactulose is the most widely used carbohydrate substrate for orocecal transit time determination, as the time lag between ingestion of lactulose and the rise in breath hydrogen of at least 3, 5, or 10 parts per million (ppm) above baseline. There is a high degree of correlation with simultaneous liquid transit by scintigraphy,75–78 and the test documents pharmacological effects on gut motility.79–83 Unfortunately, lactulose itself markedly accelerates transit, presumably owing to its osmotic activity. In addition, these tests are usually conducted during fasting, and this may not accurately reflect postprandial small bowel transit, and, usually, symptoms occur postprandially.

Stable Isotope Breath Test

A stable isotope (lactose 13C-ureide) was proposed with a very small dose of the substrate (0.5–1.2 g) which cannot be cleaved at the human intestinal brush border and requires the colonic bacterial flora to free 13C-ureide, which subsequently undergoes hydrolysis with release of 13CO2 and excretion by the lungs. The ratio of breath 13CO2/12CO2 is determined by isotope ratio mass spectrometry, and the first increase in breath at 2.5 standard deviations above the running average indicates the orocecal transit time.84 The lactose 13C-ureide test has been validated by comparison with scintigraphy84 and has been used to evaluate effects of pharmacological agents.85–87

Small Intestine Scintigraphy

Small bowel scintigraphy is not commonly used outside of research as part of whole-gut transit tests.88 Small bowel transit time can be calculated as the time for 10% or 50% of the radiolabel to arrive at the terminal ileum or cecum, after correcting for gastric emptying by subtracting the time for the equivalent proportion emptied from the stomach.89 A valid surrogate for the 10% scintigraphic small bowel transit time is the percent of the meal filling the colon at 6 hours (CF6), which reflects orocecal transit.40 Since the radiolabel is ingested with the meal, the result is significantly impacted by the rate of gastric emptying. The range of normal values for colonic filling at 6 hours is 11%–70% with radiolabeled nondigestible particles90,91 or 43%–95% for radiolabeled digestible solids.92 However, more recent studies conducted in >200 healthy controls have shown variation in CF6 in healthy subjects is 0–100% and, therefore, it is not possible to definitely diagnose abnormal small bowel motility using CF6 (Camilleri M, unpublished observation). In clinical practice, a low value (e.g. <20%) of CF6 is often associated with slow colonic transit, particularly in the right colon, and it is unclear whether this is a reflection of significant pathology in the small intestine or is simply a consequence of failed ascending colon emptying preventing flow of ileal content into the colon.

In research, these measurements of small bowel transit time have demonstrated the effects of treatment, such as cisapride in gastroparesis and chronic intestinal dysmotility93,94 and tegaserod in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation95 or prucalopride and YKP10811 in functional constipation.96,97

First CT enterography and now MR enterography have become routine diagnostic tools for inflammatory bowel disease,98,99 and it is of great interest that these tests include dynamic image sets to assess motility in affected bowel segments.100 Perhaps the routine collection large data sets can be used to develop better automated image analyses and more robust small bowel imaging for motility disorders independent of organic disease. Indeed, a very recent study used the automated motility assessment of MR enterography developed for patients with Crohn’s disease to assess small bowel motility in patients with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction,101 demonstrating the potential of such an approach.

Use of Wireless pH and Motility Capsule to Measure Small Bowel Transit

Small bowel transit time can also be measured with a wireless motility capsule (WMC).49 The transit of the large indigestible solids depends on phase II and phase III activity of the interdigestive motor complex,102 as well as fed intestinal motility, but the evidence is limited. The procedure is similar to that for WMC measurement of gastric emptying. The WMC small bowel transit time is defined as the interval between this rise in pH and the time when the pH suddenly falls by more than 1 U for at least 5 minutes as the WMC enters the cecum.

In separate studies in 9 healthy subjects, the median WMC small bowel transit time was 350 minutes (IQR: 169–676 minutes),103 276 minutes (IQR: 240–354 minutes),104 and 234 minutes (IQR: 201–293 minutes).105 A practical disadvantage of the test is occasional difficulty in identifying the 1 U pH drop signifying passage into the cecum, especially in patients with post-surgical changes (e.g. right hemicolectomy) or incompetent ileocecal valve resulting in bacterial colonization of the distal ileum. The nondigestible, 26*13mm WMC may become impacted in the gastrointestinal tract; therefore, contraindications include suspected mechanical obstruction, recent gastrointestinal surgery (within 3 months), and Crohn’s disease.

Whole Gut Transit in Preclinical Models

Whole gut transit in mice is typically studied by the oral administration of non-absorbable marker such as carmine red and subsequent monitoring for the first appearance of the marker in stool.106,107 Obviously, this test is a ‘leading edge’ assay that may simplify or misrepresent the overall motility of the gastrointestinal tract. Terminal experiments, where the orally administered tracers are assayed in numerous segments of the gastrointestinal tract to assess overall transit as measured by geometrical center,57,58 improve the limitations of ‘leading edge’ experiments such as carmine red, but reintroduce the requirement for terminal, rather than repeatable tests of whole gut transit.

A recent study described scintigraphy using steel beads and barium in mice to measure intestinal transit in a non-terminal manner.108 This is an intriguing development that may lead to better noninvasive preclinical studies; however, the relatively poor accuracy of clinical scintigraphy for intestinal transit, as presented above, may limit the translational potential of the method.

WMC for use in whole gut transit was validated using dogs109 and has been used in several studies in dogs,110–112 pigs,113 rabbits,114 and horses.115 To our knowledge, valid technologies have not been developed for use in small animals.

Evaluation of Colon Transit

Radiopaque Markers

Radiopaque markers can be used to evaluate total and segmental colonic transit times. Several different methods to measure colonic transit with radiopaque markers have been described.116–120 The minimum number of markers to be ingested daily should be at least 10 to 12 for reporting colonic transit time in days or hours.121

Localization of retained markers in the rectosigmoid area suggests functional outlet obstruction, whereas diffuse distribution of the retained markers is suggestive of slow transit constipation. However, this is not diagnostic, as delayed rectosigmoid transit due to pelvic floor dyssynergia may inhibit proximal colonic transit and result in widespread distribution of markers.

Segmental transit times are measured in the right colon to the right of the vertebral spinous processes and above a line from the fifth lumbar vertebra to the pelvic outlet. The left colon is the area to the left of the vertebral spinous processes and the line above the fifth lumbar vertebra and the left anterior superior iliac crest. The rectosigmoid is the area under the line from the pelvic brim on the right to the superior iliac crest on the left. The advantages of the radiopaque marker method are the well-established normal values and standardization of methods; it is also readily available and reasonably inexpensive. Sadik et al. have quantitated rapid colonic transit using radiopaque markers.120 Radiopaque markers are the reference standard for colon transit evaluation in clinical practice.122

Colonic Scintigraphy

Measurement of colonic transit by scintigraphy is safe, noninvasive, correlates with radiopaque markers, and provides information on ascending colon (AC) emptying and overall colon transit.123 In the most widely published method, subjects ingest a pH-sensitive methacrylate-coated capsule containing 111In-labeled activated charcoal particles after fasting overnight; the coated capsule dissolves in the neutral pH in the terminal ileum, releasing the radioisotope into the lumen.91 The alternative method follows the transit of radiolabeled liquid in a whole gut transit test for solid–liquid meal including colonic transit.124 Repeated anterior and posterior abdominal scans of 2 minutes’ duration acquired with a gamma camera at 4, 6, 8, 24, and 48 hours post-ingestion to appraise colonic transit125 were summarized as a geometric center (weighted average) of radioactivity based on 5125 or 7 regions.124 The times of greatest interest for overall colonic transit are at 24, 48, and 72 hours. The delayed-release capsule facilitates the measurement of AC emptying as the time for emptying half of the radioactivity from the AC (T1/2), which is calculated by linear interpolation of values on the AC emptying curve.126 Thus, by delivering radiolabeled charcoal particles to the ileocolonic region upon capsule dissolution, the particles empty from the ileum into the colon by bolus movements.127

Normal values, performance characteristics, coefficients of variation, application in patients with diarrhea or constipation, differences in transit profile between slow colonic transit constipation and defecation disorders, and relationship between colonic transit summaries at 24 and 48 hours and bowel function symptoms have been extensively documented.126,128–130

The intra-individual coefficients of variation were 31% at 24 hours and 27% at 48 hours over a period of less than 3 weeks, and 38% at 24 hours and 30% at 48 hours over a median interval of 2 years.126 The degree of variation is similar across different mean values of colonic transit, and the vast majority of individuals have replicate values within 1 geometric center unit of measurement. This variation reflects the physiological, natural variation in stool frequency and consistency.

Whole colonic scintigraphic transit and AC emptying have been reported to be abnormal in several diseases of colonic motility, including idiopathic constipation, functional diarrhea, carcinoid diarrhea,131 and different subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)132 and bile acid diarrhea. It is, therefore, plausible that colonic transit measurement may serve as a biological marker of colonic function in disease and as a surrogate endpoint in the evaluation of drug therapy.133 For example, scintigraphic colonic transit has correctly predicted clinical efficacy with medications targeting different mechanisms, including prokinetics such as 5-HT4 agonists, bisacodyl, and neurotrophin-3; medications retarding transit such as 5-HT3 antagonists and cholecystokinin (CCK1) antagonist; and secretagogues such as linaclotide and lubiprostone. Equally important, colonic transit measurement has correctly predicted lack of efficacy of medications to alter bowel dysfunction in IBS in clinical trials when there were no significant effects of the drug on colonic transit, such as pexacerafont (corticotropin releasing factor-1 antagonist) and solabegron (β3 adrenergic agonist).

Use of Wireless pH and Motility Capsule to Measure Colonic Transit

The passage of the WMC into the cecum is determined by the sudden fall of pH by more than 1 U, which lasts for at least 5 minutes; colonic transit time is the time from entry into the cecum to the time the WMC passes out of the colon with the sudden drop in the temperature and loss of pressure recordings. Colonic transit time in 78 constipated and 87 healthy subjects demonstrated a median value of 21.7 hours (IQR: 15.5–37.3 hours, 95th percentile 59 hours) in healthy subjects and 46.7 hours (IQR: 24.0–91.9 hours) in constipated patients.134 The correlation of the WMC to percent of radiopaque markers retained on day 5 was significant (r=0.69) in constipated patients studied simultaneously with both methods.134

In a large multicenter study of 158 patients with constipation, there was overall agreement of 87% for classifying subjects as having slow or normal colonic transit.105 The WMC has also been used to characterize pressure activity in colon of healthy controls and in constipated patients.52

The advantages of the WMC assessment of colonic transit are performance in the patients’ usual surroundings, appraisal of whole gut and regional transit, and no radiation exposure. Sometimes, discerning the 1 U decrease in pH (entry into the cecum) may be difficult. The method is more expensive than other methods (radiopaque markers, scintigraphy) to measure colonic or whole gut transit.

Tests to Evaluate Gastrointestinal, Colonic and Anorectal Contractility

Antropyloroduodenal Manometry

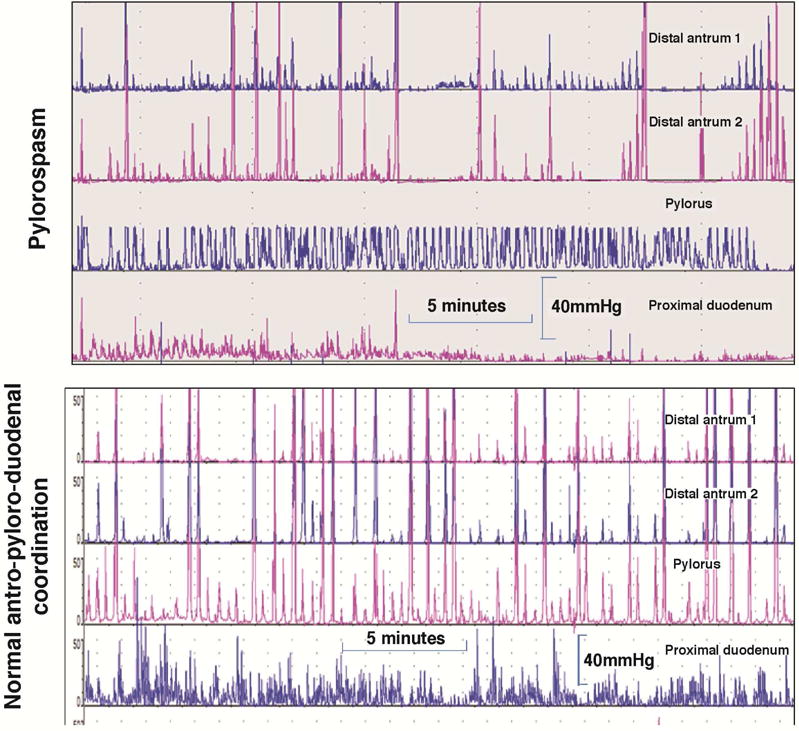

The distal stomach, pylorus, and duodenum, with their relatively small diameters and ability to generate high-amplitude pressure activity, are suitable for manometric recordings (Figure 2). Antroduodenal manometry is available mainly at a few tertiary referral centers; the test is invasive, typically requiring tube placement with the aid of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, time consuming, and requires skilled technical support. An alternative, a wireless motility capsule, detects the frequency and amplitude of phasic contractions during the process of capsule emptying from the stomach and its passage through the small intestine (and colon, see below).

Figure 2.

Antroduodenal motility tracings in the postprandial period with sensors 1cm apart. Note in the upper example the consistent phasic and tonic contractions at the pylorus with intermittent loss of distal antral contractions 1 and 2cm proximal to the pylorus. In contrast, note the consistent antropyloric coordination in the normal example in the lower tracings. Reproduced from ref. 185, Camilleri M. Review: Novel diet, drugs and gastric interventions for gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016 Jan 4. pii: S1542–3565(15)01724-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.033. [Epub ahead of print]

The main indications for antroduodenal manometry are: evaluation of the cause of documented gastric or small bowel transit (neuropathy or myopathy) and clarification of whether there is a generalized or localized dysmotility in patients with suspected colonic inertia. The method typically uses water-perfused manometric catheters or solid-state sensors mounted on motility catheters. The tube is positioned with the aid of fluoroscopy. The intragastric sensors should be 1cm or less apart to ensure optimal measurements of distal antral contractile activity proximal to the pylorus, which can be identified manometrically by a combination of distal antral and duodenal peaks and the presence of a high pressure zone (“tone”). A solid-liquid meal is ingested during the test which appraises predominantly the amplitude of contractions and the physiological responses in the fasting and postprandial periods. Thus, normal gastroduodenal motility consists of at least 1 MMC per 24 hours, conversion to the fed pattern with ingestion of a meal without return of MMC for at least 2 hours after a >400kcal meal, and consistent distal postprandial antral (>40mmHg, with an average frequency of 1 contraction per minute during the first postprandial hour) and small intestinal contractions (>20mmHg).135

Myopathic disorders (e.g., scleroderma, amyloidosis, hollow visceral myopathy) are characterized by low-amplitude contractions (consistently <20mmHg in small bowel and <40mmHg in distal antrum).136 In neuropathic disorders, there is increased frequency (e.g. 3 during 3 hours) of fasting MMCs in the duodenum while awake, postprandial antral hypomotility (average frequency of contractions in distal antrum <1/minute during the first postprandial hour) and a return of phase III MMC-like activity within 2 hours of the ingestion of a >400kcal meal.137

Correlations of findings on manometry with histopathology are poor, but they are based on a few detailed reports138 of cases of pseudo-obstruction. Manometry has to be interpreted with caution, as abnormal motor patterns do not necessarily imply causation of the patient’s symptoms. Stress related to the intubation and procedure may delay gastric emptying, impair antral contractility, suppress MMC cycling, and induce intestinal “irregularity”.

The greatest use of gastroduodenal manometry in research is in drug development, that is in demonstrating prokinetic effects of novel medications in addition to effects on gastric emptying, such as with the 5-HT4 receptor agonist, cisapride,93 and the ghrelin receptor pentapeptide agonist, relamorelin.139

Colonic Phasic Contractility and Tone

Tone is measured by the barostat; phasic contractions can be measured by manometry or wireless pressure capsule. Stationary laboratory-based studies to assess motility are usually conducted for 6 hours, during which colonic compliance, fasting, and 2-hour postprandial recordings of contractions and tone are conducted. Ambulatory studies are usually conducted over 24 hours and involve measurement of phasic contractions.140 There is evidence that increased number of solid-state sensors on the colonic tube or a fiberoptic manometry catheter, pioneered by thorough and systematic research conducted predominantly by Australian groups,141 results in high resolution measurements of antegrade and retrograde contractions, as well as definition of the locus of origination of high amplitude propagated contractions (HAPCs).

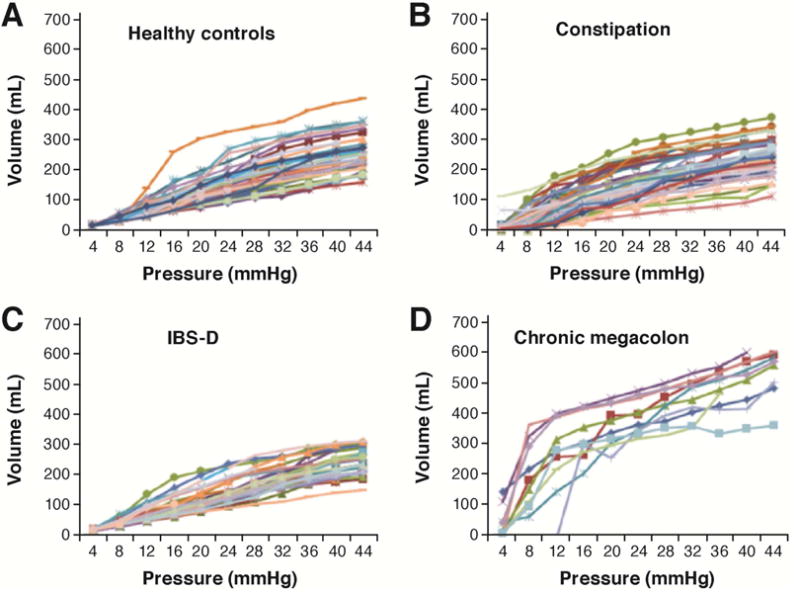

In clinical practice, the main indications for colonic manometry (usually with barostat assessment of compliance and tone) are: severe constipation with slow colonic transit and no evidence of an evacuation disorder in patients who are unresponsive to medical therapy142 and confirmation of chronic megacolon or megarectum (Figure 3) when viscus diameters exceed 10 and 15cm respectively.143 The most useful measurements in research and clinical practice are compliance142,143 and HAPCs,144 and the responses to intravenous neostigmine.145 The reproducibility and performance characteristics of compliance and tone measurements are documented in the literature.146

Figure 3.

Colonic compliance in (A) healthy, (B) functional constipation/constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome, (C) diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) groups; and (D) patients with chronic megacolon. Note the markedly increased volume of the intracolonic balloon (10cm long) in patients with megacolon compared to controls. Reproduced from ref. 143, O’Dwyer RH, et al. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:2398–2407.

Colonic motility and tone or compliance have been used to demonstrate effects of biological agents (e.g. bile acids),147 pharmacological agents (e.g. cholinergic modulation as with neostigmine),148 adrenergic agents,149 cannabinoid receptor agonist,150 ghrelin receptor agonist,151 and 5-HT4 receptor agonist.152

Colonic measurement of contractions has been used in several preclinical models recorded by surgically implanted strain-gauge transducers. For example, Briejer demonstrated induction of giant migrating contractions by prucalopride in the dog,153 and Sarna et al. examined several neurotransmitter substances that modulate contractile activity of the rat colon.154 High resolution manometry has advanced rapidly and may become a preclinical model of choice.155

Similarly, measurement of colonic tone, compliance and reflexes, and responses to meals and pharmacological agents have been measured in canine colon into which a barostat device was inserted typically through a cecal cannula.156–158 More recently, barostat studies of the colon have been performed in the horse159 and pig.160

Anorectal Manometry

Anorectal manometry is essential for the evaluation of patients with constipation (to exclude evacuation disorders) or fecal incontinence.155 Two technologies that currently dominate in practice and research161–163 are:

High-resolution anorectal manometry (HRAM) with flexible catheters, typically with 8 to 12 longitudinal sensors spaced approximately 0.6–1cm apart, and the most proximal 1 or 2 sensors within a balloon attached to the uppermost part of the catheter for rectal distension/sensory testing, and the most distal sensor, left outside of the anal canal, recording atmospheric pressure. Other configurations use 12 to 36 circumferential sensors or 4 radially arranged sensors at each level, from which pressures can be averaged to provide a mean pressure.

Three-dimensional high-definition anorectal pressure manometry/topography (3-D HDAM), which utilizes a rigid probe (100mm length and 10.75mm diameter) housing 256 pressure sensors arranged in 16 rows spaced 4mm apart, each containing 16 circumferentially oriented sensors 2.1mm apart). The area of measurement is 6.4cm long and provides detailed anal morphology by linear interpolation through dedicated software to provide 2-D or 3-D cylindrical topography of the anal canal, which can be viewed from all sides.

Normal values that are influenced by age, gender, and body mass index have been published. In general, there is reasonable concordance between studies of average values reported for anal resting tone, though resting tone and squeeze pressures are generally higher when measured with HRAM/3-D HDAM techniques, possibly due to reduced fidelity of traditional water-perfused systems. Further studies are required to validate the utility of HRAM/3-D HDAM techniques for evaluating and diagnosing dyssynergia in patients with defecatory disorders and fecal incontinence.155,164

Anorectal manometry studies are less often applied in research studies other than for the assessment of different methods for normalizing functions in defecatory disorders or fecal incontinence.165

Colonic Motility and Transit in Preclinical Studies

Bead expulsion assays in mice have become the preclinical model of choice to understand effects on colonic motility.166,167 The assay involves the intrarectal insertion of a 2–3cm glass bead within the colon in awake mice and measurement of the time it takes for the bead to leave the anus. There is tremendous variability in the assay both between and within individual animals. This variability is likely due to stress-induced defecation in mice where five to six fecal pellets, the entire content of the mouse colon, are expelled at once.

Colonic motor activity in mice has also been assessed using water-based168 and solid-state manometers.169 While these measures of pressure improve the ability to assess colonic motility beyond the limits of bead expulsion assays, they remain isolated measures of contractility. The development of dual-sensor manometric probes170 to assess propulsive and retropulsive contractions in mouse colon gives hope that more advanced technologies for mouse colonic motility are forthcoming.

Scintigraphy and manometry have been used to study colonic motility in rats.170–174 In addition, the defecation reflex has been well characterized in rats, making this animal model suitable to replace dogs for preclinical testing.175 Fluoroscopic analysis of colonic motility has been extensively studied in the pig.176 While pigs are typically not used in drug discovery, the pig has been developed as a preclinical model of electrical stimulation for evacuation dysfunction and manometry to assess contractility.177 Colonic motility in the rabbit has also been characterized radiographically,178 and recent advances in high resolution colonic manometry are being validated using rabbit colon,179 which may make rabbits a preclinical animal of choice in the near future.

New MRI Parameters of Gastrointestinal Function

MRI applications have been proposed to measure several gastrointestinal functions: gastric volumes and emptying, small bowel water content, colonic volumes, bowel gas volumes, esophageal, gastric, small bowel and colonic motility, anorectal and pelvic floor motion and anatomical integrity, and whole gut transit measured using MRI capsule markers filled with watery gel pellets or water doped with an MRI contrast agent. These methods are reviewed in detail elsewhere.180 It is interesting to note that software-quantified bowel motility using cine MRI has potential as a future tool to investigate enteric dysmotility, using a validated motility assessment technique based on motion capture MRI.101 Another application of MRI to measure colonic motility involves challenge with a laxative preparation (PEG3350-electrolyte solution) and use of MRI marker pills.181

Conclusion

There have been numerous recent advances in measurement of gastrointestinal motility in both human and preclinical models. Imaging technologies especially have advanced rapidly, and it is encouraging to recognize that digestive disease researchers appear to be keeping pace with these advances. It is instructive to understand that, just as the invention of the Roentgen tube in 1895 was rapidly adapted by Walter B. Cannon to make the first seminal observations of modern gastrointestinal motility182,183 and formed the basis for the modern scintigraphic tests presented here,184 modern neurogastroenterologists are rapidly adapting other medical imaging technologies and high resolution or fiberoptic measurements of intraluminal pressures into novel clinical tests. It is also important to recognize the value of reverse translating new clinical tests for use in preclinical studies. Nowhere is this idea better demonstrated than the reverse translation of gastric emptying tests for use in mice. It is the sincere hope of the authors that the juxtaposition of state-of-art motility tests for both humans and animals will inform researchers of the great potential of this bedside-to-bench-to-bedside approach for the future of neurogastroenterology.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mrs. Cindy Stanislav for secretarial assistance.

Funding: This work was supported by grants R56-DK67071 (MC), R01-DK92179 (MC), R01-DK106011 (DRL), and P01-DK68055 (MC and DRL) from National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions: Both authors contributed equally to the writing of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Savarino E, Zentilin P, Savarino V, Tenca A, Penagini R, Clarke JO, Bravi I, Zerbib F, Yüksel ES. Functional testing: pharyngeal pH monitoring and high-resolution manometry. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1300:226–35. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlson DA, Pandolfino JE. High-resolution manometry and esophageal pressure topography: filling the gaps of convention manometry. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zerbib F, Roman S. Current therapeutic options for esophageal motor disorders as defined by the Chicago Classification. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:451–60. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt RH, Camilleri M, Crowe SE, El-Omar EM, Fox JG, Kuipers EJ, Malfertheiner P, McColl KE, Pritchard DM, Rugge M, Sonnenberg A, Sugano K, Tack J. The stomach in health and disease. Gut. 2015;64:1650–68. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. Physiological variations in canine gastric tone measured by an electronic barostat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1985;248:G229–37. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1985.248.2.G229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tutuian R, Vos R, Karamanolis G, Tack J. An audit of technical pitfalls of gastric barostat testing in dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:113–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulie B, Tack J, Sifrim D, Andrioli A, Janssens J. Role of nitric oxide in fasting gastric fundus tone and in 5-HT1 receptor-mediated relaxation of gastric fundus. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G373–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.2.G373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao J, Liao D, Gregersen H. Tension and stress in the rat and rabbit stomach are location-and direction-dependent. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:388–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tournadre JP, Allaouchiche B, Malbert CH, Chassard D. Metabolic acidosis and respiratory acidosis impair gastro-pyloric motility in anesthetized pigs. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2000;90:74–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200001000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorenzo-Figueras M, Jones G, Merritt AM. Effects of various diets on gastric tone in the proximal portion of the stomach of horses. Am J Vet Res. 2002;63:1275–8. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2002.63.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rouzade ML, Fioramonti J, Bueno L. Decrease in gastric sensitivity to distension by 5-HT1A receptor agonists in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2048–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1018859214758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monroe MJ, Hornby PJ, Partosoedarso ER. Central vagal stimulation evokes gastric volume changes in mice: a novel technique using a miniaturized barostat. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:5–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2003.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chial HJ, Camilleri C, Delgado-Aros S, Burton D, Thomforde G, Ferber I, Camilleri M. A nutrient drink test to assess maximum tolerated volume and postprandial symptoms: effects of gender, body mass index and age in health. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14:249–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2002.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tack J, Caenepeel P, Piessevaux H, Cuomo R, Janssens J. Assessment of meal induced gastric accommodation by a satiety drinking test in health and in severe functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2003;52:1271–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.9.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouras EP, Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M, Castillo EJ, Burton DD, Thomforde GM, Chial HJ. SPECT imaging of the stomach: comparison with barostat and effects of sex, age, body mass index, and fundoplication. Gut. 2002;51:781–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Schepper HU, Cremonini F, Chitkara D, Camilleri M. Assessment of gastric accommodation: overview and evaluation of current methods. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:275–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delgado-Aros S, Vella A, Camilleri M, Low PA, Burton DD, Thomforde GM, DeSchepper H, Camilleri M, Cremonini F, Foxx-Orenstein A, Burton D. Comparison of gastric volumes in response to isocaloric liquid and mixed meals in humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:567–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delgado-Aros S, Kim DY, Burton DD, Thomforde GM, Stephens D, Brinkmann BH, Vella A, Camilleri M. Effect of GLP-1 on gastric volume, emptying, maximum volume ingested and postprandial symptoms in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G424–31. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2002.282.3.G424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liau SS, Camilleri M, Kim DY, Stephens D, Burton DD, O’Connor MK. Pharmacological modulation of human gastric volumes demonstrated noninvasively using SPECT imaging. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2001;13:533–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2001.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delgado-Aros S, Vella A, Camilleri M, Low PA, Burton DD, Thomforde GM, Stephens D. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 and feeding on gastric volumes in diabetes mellitus with cardio-vagal dysfunction. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2003;15:435–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2003.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bredenoord AJ, Chial HJ, Camilleri M, Mullan BP, Murray JA. Gastric accommodation and emptying in evaluation of patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:264–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breen M, Camilleri M, Burton D, Zinsmeister AR. Performance characteristics of the measurement of gastric volume using single photon emission computed tomography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:308–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01660.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Schepper H, Camilleri M, Cremonini F, Foxx-Orenstein A, Burton D. Comparison of gastric volumes in response to isocaloric liquid and mixed meals in humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:567–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simonian HP, Maurer AH, Knight LC, Kantor S, Kontos D, Megalooikonomou V, Fisher RS, Parkman HP. Simultaneous assessment of gastric accommodation and emptying: studies with liquid and solid meals. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1155–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton DD, Kim HJ, Camilleri M, Stephens DA, Mullan BP, O’Connor MK, Talley NJ. Relationship of gastric emptying and volume changes after a solid meal in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G261–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00052.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padmanabhan P, Grosse J, Asad AB, Radda GK, Golay X. Gastrointestinal transit measurements in mice with 99mTc-DTPA-labeled activated charcoal using NanoSPECT-CT. EJNMMI Res. 2013;3:60. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-3-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dadachova E, Carrasco N. The Na/I symporter (NIS): imaging and therapeutic applications. Semin Nucl Med. 2004;34(1):23–31. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Portulano C, Paroder-Belenitsky M, Carrasco N. The Na+/I- symporter (NIS): mechanism and medical impact. Endocr Rev. 2014;35:106–49. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suksanpaisan L, Pham L, McIvor S, Russell SJ, Peng KW. Oral contrast enhances the resolution of in-life NIS reporter gene imaging. Cancer Gene Ther. 2013;20:638–41. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2013.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilja OH, Hausken T, Odegaard S, Berstad A. Monitoring postprandial size of the proximal stomach by ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med. 1995;14:81–9. doi: 10.7863/jum.1995.14.2.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao D, Gregersen H, Hausken T, Gilja OH, Mundt M, Kassab G. Analysis of surface geometry of the human stomach using real-time 3D ultrasonography in vivo. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:315–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilja OH, Hausken T, Odegaard S, Berstad A. Ultrasonography and three-dimensional methods of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:277–82. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200503000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manini ML, Burton DD, Meixner DD, Eckert DJ, Callstrom M, Schmit G, El-Youssef M, Camilleri M. Feasibility and application of 3-dimensional ultrasound for measurement of gastric volumes in healthy adults and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:1–7. doi: 10.1097/mpg.0b013e318189694f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Zwart IM, Mearadji B, Lamb HJ, Eilers PH, Masclee AA, de Roos A, Kunz P. Gastric motility: comparison of assessment with real-time MR imaging or barostat measurement initial experience. Radiology. 2002;224:592–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2242011412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fidler J, Bharucha AE, Camilleri M, Camp J, Burton D, Grimm R, Riederer SJ, Robb RA, Zinsmeister AR. Application of magnetic resonance imaging to measure fasting and postprandial volumes in humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:42–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janssen P, Verschueren S, Ly HG, Vos R, Van Oudenhove L, Tack J. Intragastric pressure during food intake: a physiological and minimally invasive method to assess gastric accommodation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:316–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papathanasopoulos A, Rotondo A, Janssen P, Boesmans W, Farré R, Vanden Berghe P, Tack J. Effect of acute peppermint oil administration on gastric sensorimotor function and nutrient tolerance in health. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:e263–71. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rotondo A, Janssen P, Mulè F, Tack J. Effect of the GLP-1 analog liraglutide on satiation and gastric sensorimotor function during nutrient-drink ingestion. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:693–8. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Camilleri M, Hasler W, Parkman HP, Quigley EMM, Soffer E. Measurement of gastrointestinal motility in the GI laboratory. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:747–62. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, Greydanus MP, Brown ML, Proano M. Towards a less costly but accurate test of gastric emptying and small bowel transit. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:609–15. doi: 10.1007/BF01297027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tougas G, Eaker EY, Abell TL, Abrahamsson H, Boivin M, Chen J, Hocking MP, Quigley EM, Koch KL, Tokayer AZ, Stanghellini V, Chen Y, Huizinga JD, Rydén J, Bourgeois I, McCallum RW. Assessment of gastric emptying using a low-fat meal: establishment of international control values. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1456–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abell TL, Camilleri M, Donohoe K, Hasler WL, Lin HC, McCallum RW, Nowak T, Nusynowitz ML, Parkman HP, Shreve P, Szarka LA, Snape WJ, Jr, Ziessman HA. Consensus recommendations for gastric emptying scintigraphy: a joint report of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:753–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Camilleri M, Shin A. Editorial: Novel and validated approaches for gastric emptying scintigraphy in patients with suspected gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1813–5. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2715-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Camilleri M, Iturrino J, Bharucha AE, Burton D, Shin A, Jeong I-D, Zinsmeister AR. Performance characteristics of scintigraphic measurement of gastric emptying of solids in healthy participants. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:1076–e562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choi MG, Camilleri M, Burton DD, Zinsmeister AR, Forstrom LA, Nair KS. [13C]octanoic acid breath test for gastric emptying of solids: accuracy, reproducibility, and comparison with scintigraphy. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1155–62. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tinker J, Kocak N, Jones T, Glass HI, Cox AG. Supersensitivity and gastric emptying after vagotomy. Gut. 1970;11:502–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.11.6.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuo B, Viazis N, Bahadur S. Noninvasive simultaneous measurement of intra-liminal pH and pressure: assessment of gastric emptying and upper GI manometry in healthy subjects. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:666. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cassilly D, Kantor S, Knight LC, Maurer AH, Fisher RS, Semler J, Parkman HP. Gastric emptying of a non-digestible solid: assessment with simultaneous SmartPill pH and pressure capsule, antroduodenal manometry, gastric emptying scintigraphy. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:311–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuo B, McCallum RW, Koch KL, Sitrin MD, Wo JM, Chey WD, Hasler WL, Lackner JM, Katz LA, Semler JR, Wilding GE, Parkman HP. Comparison of gastric emptying of a non-digestible capsule to a radio-labeled meal in healthy and gastroparetic subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:186–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kloetzer L, Chey WD, McCallum RW, Koch KL, Wo JM, Sitrin M, Katz LA, Lackner JM, Parkman HP, Wilding GE, Semler JR, Hasler WL, Kuo B. Motility of the antroduodenum in healthy and gastroparetics characterized by wireless motility capsule. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:527–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brun R, Michalek W, Surjanhata BC, Parkman HP, Semler JR, Kuo B. Comparative analysis of phase III migrating motor complexes in stomach and small bowel using wireless motility capsule and antroduodenal manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:332–e165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hasler WL, Saad RJ, Rao SS, Wilding GE, Parkman HP, Koch KL, McCallum RW, Kuo B, Sarosiek I, Sitrin MD, Semler JR, Chey WD. Heightened colon motor activity measured by a wireless capsule in patients with constipation: relation to colon transit and IBS. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G1107–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00136.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rozov-Ung I, Mreyoud A, Moore J, Wilding GE, Khawam E, Lackner JM, Semler JR, Sitrin MD. Detection of drug effects on gastric emptying and contractility using a wireless motility capsule. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Viramontes BE, Kim DY, Camilleri M, Lee JS, Stephens D, Burton DD, Thomforde GM, Klein PD, Zinsmeister AR. Validation of a stable isotope gastric emptying test for normal accelerated or delayed gastric emptying. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2001;13:567–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2001.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.FDA approves breath test to aid in diagnosis of delayed gastric emptying. 2015 Apr 5; http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm441370.htm. Accessed March 9, 2016.

- 56.Szarka LA, Camilleri M, Vella A, Burton D, Baxter K, Simonson J, Zinsmeister AR. A stable isotope breath test with a standard meal for abnormal gastric emptying of solids in the clinic and in research. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:635–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miller MS, Galligan JJ, Burks TF. Accurate measurement of intestinal transit in the rat. J Pharmacol Methods. 1981;6:211–7. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(81)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moore BA, Otterbein LE, Türler A, Choi AM, Bauer AJ. Inhaled carbon monoxide suppresses the development of postoperative ileus in the murine small intestine. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:377–91. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bennink RJ, De Jonge WJ, Symonds EL, van den Wijngaard RM, Spijkerboer AL, Benninga MA, Boeckxstaens GE. Validation of gastric-emptying scintigraphy of solids and liquids in mice using dedicated animal pinhole scintigraphy. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1099–1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Whited KL, Hornof WJ, Garcia T, Bohan DC, Larson RF, Raybould HE. A non-invasive method for measurement of gastric emptying in mice: effects of altering fat content and CCK A receptor blockade. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:421–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Symonds EL, Butler RN, Omari TI. Assessment of gastric emptying in the mouse using the [13C]-octanoic acid breath test. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2000;27:671–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Choi KM, Zhu J, Stoltz GJ, Vernino S, Camilleri M, Szurszewski JH, Gibbons SJ, Farrugia G. Determination of gastric emptying in nonobese diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G1039–45. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00317.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sutton DG, Bahr A, Preston T, Christley RM, Love S, Roussel AJ. Validation of the [13C]octanoic acid breath test for measurement of equine gastric emptying rate of solids using radioscintigraphy. Equine Vet J. 2003;35:27–33. doi: 10.2746/042516403775467423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wyse CA, Murphy DM, Preston T, Morrison DJ, Love S. Assessment of the rate of solid-phase gastric emptying in ponies by means of the [13C]octanoic acid breath test: a preliminary study. Equine Vet J. 2001;33:197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2001.tb00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McLeay LM, Carruthers VR, Neil PG. Use of a breath test to determine the fate of swallowed fluids in cattle. Am J Vet Res. 1997;58:1314–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McLellan J, Wyse CA, Dickie A, Preston T, Yam PS. Comparison of the carbon 13-labeled octanoic acid breath test and ultrasonography for assessment of gastric emptying of a semisolid meal in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2004;65:1557–62. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2004.65.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tsukamoto A, Ohno K, Maeda S, Nakashima K, Fukushima K, Fujino Y, Hori M, Tsujimoto H. Effect of mosapride on prednisolone-induced gastric mucosal injury and gastric-emptying disorder in dog. J Vet Med Sci. 2012;74:1103–8. doi: 10.1292/jvms.12-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schoonjans R, Van Vlem B, Van Heddeghem N, Vandamme W, Vanholder R, Lameire N, Lefebvre R, De Vos M. The 13C-octanoic acid breath test: validation of a new noninvasive method of measuring gastric emptying in rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14:287–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2002.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Whited KL, Lu D, Tso P, Kent Lloyd KC, Raybould HE. Apolipoprotein A-IV is involved in detection of lipid in the rat intestine. J Physiol. 2005;569:949–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.097634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Whited KL, Thao D, Lloyd KC, Kopin AS, Raybould HE. Targeted disruption of the murine CCK1 receptor gene reduces intestinal lipid-induced feedback inhibition of gastric function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G156–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00569.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.The FO. Boeckxstaens GE, Snoek SA, Cash JL, Bennink R, Larosa GJ, van den Wijngaard RM, Greaves DR, de Jonge WJ. Activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway ameliorates postoperative ileus in mice. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1219–28. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.The FO. de Jonge WJ, Bennink RJ, van den Wijngaard RM, Boeckxstaens GE. The ICAM-1 antisense oligonucleotide ISIS-3082 prevents the development of postoperative ileus in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:252–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morscher S, Driessen WH, Claussen J, Burton NC. Semi-quantitative Multispectral Optoacoustic Tomography (MSOT) for volumetric PK imaging of gastric emptying. Photoacoustics. 2014;2:103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tsukamoto A, Ohno K, Tsukagoshi T, Maeda S, Nakashima K, Fukushima K, Fujino Y, Tsujimoto H. Real-time ultrasonographic evaluation of canine gastric motility in the postprandial state. J Vet Med Sci. 2011;73:1133–8. doi: 10.1292/jvms.11-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu D, Cheeseman F, Vanner S. Combined oro-caecal scintigraphy and lactulose hydrogen breath testing demonstrate that breath testing detects oro-caecal transit, not small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with IBS. Gut. 2011;60:334–40. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.205476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sciarretta G, Furno A, Mazzoni M, Garagnani B, Malaguti P. Lactulose hydrogen breath test in orocecal transit assessment. Critical evaluation by means of scintigraphic method. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:1505–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02088056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.van Nieuwenhoven MA, Kovacs EM, Brummer RJ, Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Brouns F. The effect of different dosages of guar gum on gastric emptying and small intestinal transit of a consumed semisolid meal. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20:87–91. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2001.10719019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ternent CA, Thorson AG, Blatchford GJ, Christensen MA, Thompson JS, Lanspa SJ, Adrian TE. Mouth to pouch transit after restorative proctocolectomy: hydrogen breath analysis correlates with scintigraphy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1460–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Staniforth DH. Effect of drugs on oro-caecal transit time assessed by the lactulose/breath hydrogen method. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;33:55–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00610380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yuan CS, Foss JF, O’Connor M, Moss J, Roizen MF. Gut motility and transit changes in patients receiving long-term methadone maintenance. J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;38:931–5. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1998.tb04389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yuan CS, Foss JF, Osinski J, Toledano A, Roizen MF, Moss J. The safety and efficacy of oral methylnaltrexone in preventing morphine-induced delay in oral-cecal transit time. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;61:467–75. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gorard DA, Libby GW, Farthing MJ. Effect of a tricyclic antidepressant on small intestinal motility in health and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:86–95. doi: 10.1007/BF02063948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morali GA, Braverman DZ, Lissi J, Goldstein R, Jacobsohn WZ. Effect of clonidine on gallbladder contraction and small bowel transit time in insulin-treated diabetics. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:995–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Geypens B, Bennink R, Peeters M, Evenepoel P, Mortelmans L, Maes B, Ghoos Y, Rutgeerts P. Validation of the lactose-[13C]ureide breath test for determination of orocecal transit time by scintigraphy. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1451–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Coremans G, Vos R, Margaritis V, Ghoos Y, Janssens J. Small doses of the unabsorbable substance polyethylene glycol 3350 accelerate oro-caecal transit, but slow gastric emptying in healthy subjects. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Priebe MG, Wachters-Hagedoorn RE, Landman K, Heimweg J, Elzinga H, Vonk RJ. Influence of a subsequent meal on the oro-cecal transit time of a solid test meal. Eur J Clin Invest. 2006;36:123–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cloetens L, De Preter V, Swennen K, Broekaert WF, Courtin CM, Delcour JA, Rutgeerts P, Verbeke K. Dose-response effect of arabinoxylooligosaccharides on gastrointestinal motility and on colonic bacterial metabolism in healthy volunteers. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27:512–8. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lin HC, Prather C, Fisher RS, Meyer JH, Summers RW, Pimentel M, McCallum RW, Akkermans LM, Loening-Baucke V, AMS Task Force Committee on Gastrointestinal Transit Measurement of gastrointestinal transit. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:989–1004. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2694-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Maurer AH, Krevsky B. Whole-gut transit scintigraphy in the evaluation of small-bowel and colonic transit disorders. Semin Nucl Med. 1995;25:326–38. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(95)80006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Charles F, Camilleri M, Phillips SF, Thomforde GM, Forstrom LA. Scintigraphy of the whole gut: Clinical evaluation of transit disorders. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:113–8. doi: 10.4065/70.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR. Towards a relatively inexpensive, noninvasive, accurate test for colonic motility disorders. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:36–42. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91092-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cremonini F, Mullan BP, Camilleri M, Burton DD, Rank MR. Performance characteristics of scintigraphic transit measurements for studies of experimental therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1781–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Camilleri M, Malagelada JR, Abell TL, Brown ML, Hench V, Zinsmeister AR. Effect of six weeks of treatment with cisapride in gastroparesis and intestinal pseudoobstruction. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:704–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Camilleri M, Brown ML, Malagelada JR. Impaired transit of chyme in chronic intestinal pseudoobstruction. Correction by cisapride. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:619–26. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90631-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Prather CM, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, McKinzie S, Thomforde G. Tegaserod accelerates orocecal transit in patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:463–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bouras EP, Camilleri M, Burton DD, Thomforde G, McKinzie S, Zinsmeister AR. Prucalopride accelerates gastrointestinal and colonic transit in patients with constipation without a rectal evacuation disorder. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:354–60. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shin A, Acosta A, Camilleri M, Boldingh A, Burton D, Ryks M, Rhoten D, Zinsmeister AR. A randomized trial of 5-hydroxytryptamine4-receptor agonist, YKP10811, on colonic transit and bowel function in functional constipation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:701–8. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li Y, Hauenstein K. New imaging techniques in the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel diseases. Viszeralmedizin. 2015;31:227–34. doi: 10.1159/000435864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yacoub JH1, Obara P, Oto A. Evolving role of MRI in Crohn’s disease. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;37:1277–89. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hahnemann ML, Nensa F, Kinner S, Köhler J, Gerken G, Umutlu L, Lauenstein TC. Quantitative assessment of small bowel motility in patients with Crohn’s disease using dynamic MRI. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:841–8. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Menys A, Butt S, Emmanuel A, Plumb AA, Fikree A, Knowles C, et al. Comparative quantitative assessment of global small bowel motility using magnetic resonance imaging in chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction and healthy controls. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:376–83. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sarr MG, Kelly KA. Patterns of movement of liquids and solids through canine jejunum. Am J Physiol. 1980;239:G497–503. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1980.239.6.G497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zarate N, Mohammed SD, O’Shaughnessy E, Newell M, Yazaki E, Williams NS, Lunniss PJ, Semler JR, Scott SM. Accurate localization of a fall in pH within the ileocecal region: validation using a dual-scintigraphic technique. Am J Physiol. 2010;299:G1276–86. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00127.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sarosiek I, Selover KH, Katz LA, Semler JR, Wilding GE, Lackner JM, Sitrin MD, Kuo B, Chey WD, Hasler WL, Koch KL, Parkman HP, Sarosiek J, McCallum RW. The assessment of regional gut transit times in healthy controls and patients with gastroparesis using wireless motility technology. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:313–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]