Abstract

Introduction

The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) implemented a new Kidney Allocation System (KAS) in December 2014 that is expected to substantially reduce racial disparities in kidney transplantation among waitlisted patients. However, not all dialysis facility clinical providers and end stage renal disease (ESRD) patients are aware of how the policy change could improve access to transplant.

Methods

We describe the ASCENT (Allocation System Changes for Equity in KidNey Transplantation) study, a randomized controlled effectiveness-implementation study designed to test the effectiveness of a multicomponent intervention to improve access to the early steps of kidney transplantation among dialysis facilities across the United States. The multicomponent intervention consists of an educational webinar for dialysis medical directors, an educational video for patients and an educational video for dialysis staff, and a dialysis-facility specific transplant performance feedback report. Materials will be developed by a multidisciplinary dissemination advisory board and will undergo formative testing in dialysis facilities across the United States.

Results

This study is estimated to enroll ~600 U.S. dialysis facilities with low waitlisting in all 18 ESRD Networks. The co-primary outcomes include change in waitlisting, and waitlist disparity at 1 year; secondary outcomes include changes in facility medical director knowledge about KAS, staff training regarding KAS, patient education regarding transplant, and a medical director’s intent to refer patients for transplant evaluation.

Conclusion

The results from the ASCENT study will demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of a multicomponent intervention designed to increase access to the deceased-donor kidney waitlist and reduce racial disparities in waitlisting.

Keywords: Kidney Allocation System, multicomponent intervention, kidney transplant, waitlisting, education, ESRD Networks

Background

Current literature documents substantial disparities in access to kidney transplant waitlisting, including variation in waitlisting across the United States. 1–6 To address some of the disparities in transplant access, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) implemented a new kidney allocation system (KAS) in December 2014 that changed how kidneys are allocated to potential recipients across the United States7. Under the prior KAS, the most important determinant of receiving a new organ was time spent on the waiting list, with the clock starting when the transplant center placed the patient on the waitlist, rather than when the patient started dialysis treatment. Under the new allocation system, the waiting time reverts back to the time of dialysis treatment initiation for all dialysis patients. Because African Americans on average spend a longer time on dialysis before referral for for transplantation evaluation compared to white patients,8 this is one major aspect of the policy that is expected to reduce racial disparities in access to multiple transplant steps. However, nephrologists and other dialysis staff may not be aware that patients with longer time on dialysis who are not yet on the waitlist may receive a kidney transplant more quickly under the new KAS9. Because most U.S. ESRD patients are initially treated at a dialysis facility9, these facilities play a key role in educating patients, and referring them to a transplant center to undergo a transplant evaluation.

Prior research has suggested that multicomponent, dialysis facility-based interventions conducted with the support of government agencies such as CMS and/or ESRD Networks may be effective in improving dialysis access10, increasing vascular access11, and increasing referral for transplantation. Audit and feedback reports, otherwise known as performance feedback reports,14 have been utilized in poorly performing dialysis facilities. Furthermore, research has shown that when clinical interventions have a substantial evidence base and there is need for expediency in ensuring the intervention is rapidly translated from research into practice, an effectiveness-implementation hybrid study design may be particularly useful to increase the usefulness and policy relevance of clinical research15. Such a hybrid model allows for evaluating the effectiveness of a multicomponent intervention in a real-life setting while also assessing the intervention’s implementation and potential sustainability.

In our planned Allocation System for Changes in Equity in kidNey Transplantation (ASCENT) study, we will test the effectiveness of educating dialysis physicians, staff, and patients on this recent KAS policy change on waitlisting using this effectiveness-implementation study framework in order to more quickly implement the intervention into practice if deemed effective. We will create a multicomponent intervention consisting of a webinar for dialysis facility medical directors, educational video for patients, educational video for dialysis facility staff, and a dialysis-facility specific, transplant performance feedback report for medical directors detailing the facility’s transplant performance and communicating key relevant aspects of the new KAS in context with the facility’s data. An estimated 600 dialysis facilities across the United States with low kidney transplant waitlisting in all 18 ESRD Networks will be randomized to receive either the multicomponent intervention (intervention) or a UNOS brochure describing the recent KAS change (control). We will use a randomized effectiveness-implementation study design to test the effectiveness of the multicomponent intervention among dialysis facilities with low waitlisting, in increasing access to the deceased-donor kidney waitlist as well as reducing racial disparities in waitlisting.

Study Design and Methods

Study Overview

A Dissemination Advisory Board (DAB), including relevant stakeholders within the kidney health care system, will be convened to develop, finalize, and disseminate intervention materials among an estimated national sample of ~600 dialysis facilities with low waitlisting. Co-primary outcomes will include: 1) change in proportion of patients waitlisted, and 2) disparity reduction in proportion of patients waitlisted in a dialysis facility after 1 year. Secondary outcomes include changes from baseline to three months in medical director knowledge about transplant and KAS and medical director’s intent to refer patients for transplant.

Eligibility Criteria and Description of Potential Study Population

All 18 ESRD Networks will be contacted and invited to participate in this study. To encourage participation of ESRD Networks across the nation, we will develop annual transplant performance reports with tailored feedback detailing each participating Network’s performance in waitlisting and transplantation compared to other ESRD Networks across the U.S., as well as some of the key features that will be included in the dialysis facility-specific reports. These Network-level feedback reports will be shared only with ESRD Network staff, rather than the dialysis facilities within their respective Network.

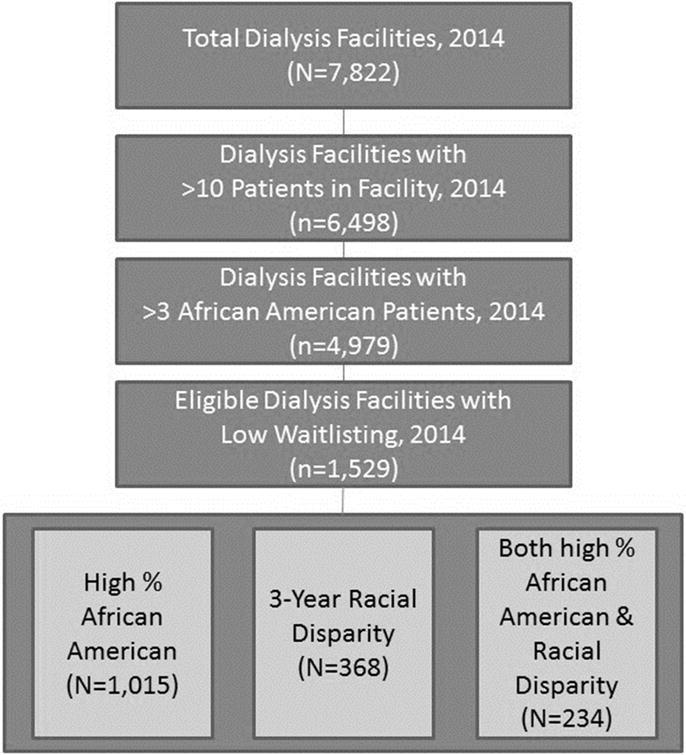

Facilities with low waitlisting, which have at least 11 patients overall and at least 4 African American patients, will be eligible for participation, since measured outcomes focus on disparity reduction and facilities with small proportions of African American or a small number of patients may be difficult to classify as a facility with a disparity. Low waitlisting will be defined as the lowest national tertile for 2014 (most recent data available) at time of randomization. Of the 1,529 dialysis facilities meeting eligibility criteria across the US, we estimate roughly ~40% of those invited (600 facilities) will agree to participate (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Selection Criteria for Dialysis Facilities Eligible to Participate among 18 End-Stage Renal Disease Networks Invited to ASCENT Study

Study Procedures

Dissemination Advisory Board

The Dissemination Advisory Board (DAB) of partnering stakeholders will be created among study co-investigators and national partners, including the National Kidney Foundation and the American Association of Kidney Patients, dialysis facility medical directors, nephrologists, social workers, ESRD patients, researchers, key policy partners, including ESRD Network 6 leadership and staff, UNOS, and regional members of the Southeastern Kidney Transplant Coalition (an academic-community collaboration among partners in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia committed to eliminating health disparities in kidney transplantation). Stakeholder feedback regarding patient barriers to kidney transplantation and development of educational materials will ensure that these intervention materials are appropriate for dialysis facilities to understand the recently changed KAS and to help communicate information to facility staff and ESRD patients in order to encourage improved access to kidney transplantation. The volunteer DAB will meet via conference phone calls monthly for ~6 months to develop the multicomponent intervention and finalize surveys. After materials are created, the DAB will review materials and provide feedback for improvement. Detailed information about each intervention material, and the role of the DAB in developing these, is described below.

Intervention Materials

Transplant Performance Feedback Reports

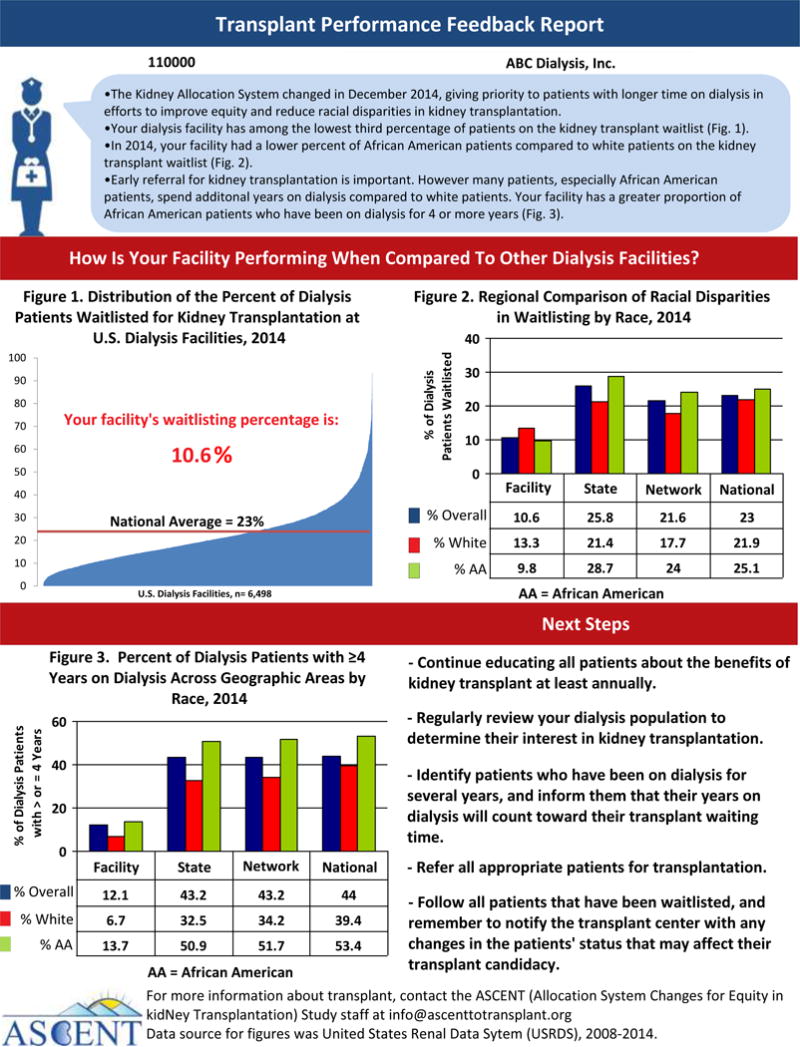

The transplant performance feedback report will reflect a dialysis facility’s performance with respect to kidney transplant waitlisting and racial disparities in waitlisting and will be provided to facility medical directors. The report will note information about recent changes in KAS most relevant for the dialysis facility and will display facility-specific transplant access performance measures, such as facility-specific waitlisting and racial disparity in waitlisting data, comparing the facility’s performance to the national average. An example potential feedback report is provided in Figure 1. The DAB will review several versions of the feedback report and discuss which layouts, content, and messages are best tailored to dialysis facilities with low waitisting. Individualized reports will be emailed to intervention-assigned dialysis facility staff by their respective ESRD Networks.

Figure 1.

Example ASCENT Feedback Report for Dialysis Facility Medical Directors

Educational Video for ESRD Patients

A ~10-minute educational video will be produced for dialysis patients, highlighting the benefits of kidney transplantation, disputing common misconceptions about transplant, and motivating patients through real patient stories on overcoming barriers to transplant. The video is intended to educate and encourage patients to talk to their providers about being referred for kidney transplantation. The DAB will help recruit patients for this video and provide input on the video script, length, content, and format as well as feedback on future revisions of the video.

Educational Video for Dialysis Facility Staff

A ~10-minute educational video targeted to dialysis facility staff (nephrologists, nurses, and social workers) will be created that describes racial disparities in transplant, recent changes in the KAS and its effort to reduce disparities, and the important role of dialysis staff in educating patients about kidney transplant and being involved with patients throughout the entire transplant process. The video will feature clinical staff, such as a social worker, nurse, and nephrologist, as well as patient testimonials to emphasize the great impact that proactive dialysis staff have on their patients’ transplant journeys. The DAB will help create the video script content, select graphics, provide feedback on video length, and review the video to provide feedback for future edits.

Educational Webinar for Medical Directors and Facility Staff

The DAB will work with a UNOS physician representative to create and present a ~30-minute webinar targeted to dialysis facility medical directors, physicians, and other staff involved in transplant education at the dialysis units. The webinar will discuss benefits of kidney transplantation, recent changes in KAS, implications of KAS on reducing racial disparities in waitlisting, and how dialysis facility staff can assist patients throughout the transplant process. The webinar will be presented live with a question-and-answer session, and will also be recorded for those who cannot attend the live session and hosted on the study website for ASCENT intervention facilities to access. Attendees who view the webinar will have an opportunity to receive continuing medical education credit. Many members of the DAB have experience with developing educational webinars and will ensure content is appropriate for dialysis facility medical directors and staff.

Formative Evaluation

To study the implementation of the intervention, we will conduct in-person and online formative testing of intervention materials in three geographically diverse dialysis facilities to ensure that these materials are appropriate for their target populations (dialysis facility medical directors, staff, and patients). Medical directors will review and provide feedback on: 1) the transplant performance feedback report 2) the webinar, and 3) a baseline survey (Appendix A) for medical directors for use in the clinical effectiveness study. A structured interview will be conducted to receive feedback on these materials and assess whether there were any missing educational domains from the transplant performance feedback report or webinar, and if the survey contains items relevant to medical directors and other clinicians involved in transplant education within the dialysis facility. During formative testing, we will also discuss with dialysis facility medical directors how long they believe it will take to educate staff and patients about the KAS to ensure that we select an appropriate time for follow-up to measure outcomes, using three months as an estimate based on previous conversations with members of the DAB.

For formative testing of the educational patient and staff videos, research staff will conduct structured interviews either in person or will administer surveys via email using a HIPAA-compliant SurveyMonkey link. Medical directors will identify staff who will be asked to view the ~10-minute staff educational video in person (either on an iPad or in a lunch-and-learn setting) or via the ASCENT website video link, followed by a structured, in-person interview or SurveyMonkey survey, depending on study site, to assess overall content and style, as well as any missing educational pieces or points of concern.

Dialysis patients will be identified by dialysis facility medical directors or staff and will be asked to watch the patient education video on an iPad or computer during their regularly scheduled dialysis appointment. After viewing videos, structured interviews will be conducted to assess patients’ satisfaction and understanding of the video, the impact of the video on patient intent to discuss transplant with providers, and other ways to improve the video.

Randomized Effectiveness-Implementation Study

We will test the effectiveness and implementation of the intervention materials16 among approximately half of the estimated 600 randomized dialysis facilities in U.S. ESRD Networks to examine whether this intervention improves dialysis facility waitlisting and reduces racial disparity in waitlisting. Because there may be significant heterogeneity in dialysis facilities and patient and staff populations across the participating ESRD Networks, we will randomize dialysis facilities that were not included in formative testing within each ESRD Network region 1:1 to either the multicomponent intervention (transplant performance feedback report, webinar, and educational videos) or control group (UNOS educational brochure) (Appendix B). At baseline, all eligible dialysis facility medical directors in both the intervention and control group will receive an email from their ESRD Network with a link to a web-based survey (HIPAA-compliant SurveyMonkey) with informed consent as the first page. We will randomize facilities to either control or intervention group, and in cases where one dialysis facility medical director or nurse manager oversees multiple facilities that are included in the study, we will assign these facilities to the same study group to avoid cross-contamination. Within one week of completing the baseline survey, all facility medical directors and/or nurse managers from participating facilities will be emailed and mailedmaterials associated with their study group assignment: and instructed to share with staff. Intervention dialysis facilities will receive an email containing all intervention materials (transplant performance feedback report, link to webinar, patient educational video, and staff educational video) and will also be mailed hard-copies of the educational videos in DVD format and performance feedback reports. Control facilities will receive the UNOS pamphlet by e-mail and mail. After approximately three months following the baseline survey, all participating facility medical directors and/or nurse managers will be emailed follow-up surveys by their respective ESRD Network contacts to assess secondary outcomes. Staff will be offered the option of a $10 gift card as incentive for participation for each survey.

Surveys

Dialysis Facility Medical Director Baseline Survey

The medical director will answer items regarding their kidney transplant knowledge and knowledge of KAS, staff training and patient education activities, and intent to refer patients for kidney transplant evaluation (Table 1; Appendix A).

Table 1.

Description of Baseline Dialysis Facility Medical Director Survey for ASCENT Study

| Scales | Description | Number of Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Dialysis Facility Characteristics | Assess dialysis facility characteristics, such as size, number of patients and staff, and amenities for patients | 14 |

| Perceived Staff Knowledge and KAS Training | Assess staff knowledge of transplant education and training provided, including proportion of staff trained on KAS and delivery of training | 4 |

| Perceived Patient Knowledge, Transplant Education, and Barriers to transplant | Assess patient knowledge of transplant, education provided, including proportion of patients educated about transplant delivery of education, and patient barriers | 4 |

| Medical Director Knowledge of Transplant, KAS, and Racial Disparity in Transplant | Assess medical director knowledge of transplantation; knowledge of KAS; and awareness about racial disparities and waitlisting performance at their own facility and nationally | 9 |

| Medical Director Referral Practices | Assess medical director’s perceived referral practices (demographics of patients referred by race and time on dialysis, and estimates of proportion of patients eligible for, interested in, referred for, and waitlisted for kidney transplantation. | 10 |

KAS=Kidney Allocation System

Dialysis Facility Medical Director Follow-Up Survey

Approximately three months after receiving educational materials, medical directors of both intervention and control facilities will receive a follow-up survey with similar questions to the baseline survey to assess knowledge about kidney transplantation and KAS, staff training on the allocation policy, patient education of transplant, intent to refer patients for kidney transplant, and uptake of intervention and control materials. Intervention and control facilities will also be asked several questions related to implementation (e.g. whether they utilized each intervention material) corresponding to their study group. The time frame of three months for a follow-up of secondary outcomes will be finalized by DAB members and medical directors during formative testing.

Co-Primary Outcome Measures and Statistical Analyses

Change in Waitlisting and Waitlisting Disparity

We will calculate change in the proportion of patients waitlisted at facilities at 1 year pre- and 1 year post-intervention to determine if intervention facilities had higher waitlisting post-study compared to control facilities. We will calculate facility racial disparity in waitlisting 1 year pre- and 1 year post-intervention as the difference between the proportions of African American vs. white patients who were waitlisted within a facility. We chose the time period of one year for two major reasons. First, national surveillance data on waitlisting is only available on an annual basis. Second, we expect the impact of the intervention to be strongest within a timeframe closest to the delivery of the intervention, i.e. within a year of the intervention.

To determine if there is a difference in either of these two co-primary outcomes among the intervention vs. control facilities we will use generalized linear models17 to account for potential correlation of facilities within Networks and two sample t-tests.

Secondary Outcome Measures

Change in Knowledge about Kidney Transplantation and KAS

At baseline and three months, we will assess change in transplant and KAS knowledge among medical directors to determine the degree of knowledge improvement among medical directors pre vs post study. Items will include general transplant knowledge, knowledge of KAS, and knowledge about racial disparities and waitlisting performance at their own facility and nationally (Table 1). The knowledge items will be summed and each dialysis provider will receive a score between 0 and 9. We will calculate average change in knowledge from pre- to post-intervention by study group, using t-tests to determine if medical directors from intervention facilities were more likely to improve in knowledge compared to providers from control facilities after receiving the intervention.

Change in Staff Training about Kidney Transplantation and KAS

We will assess at baseline and at three months what percent of staff medical directors have trained about kidney transplantation and KAS, as well as how the training was delivered (e.g., did they hold a training session, send an email, watch video presentations, etc.). We will evaluate change in how knowledgeable medical providers perceived their staff were (on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely)) on KAS pre to post-intervention. We will conduct paired t-tests to determine if differences in the proportion of items correct were greater for intervention vs. control facilities.

Change in Patient Education about Kidney Transplantation

We will ask providers at baseline and at three month follow-up whether they educated patients on kidney transplant and how this information was delivered. We will also track visits to the educational video website to determine intervention dose and usage statistics. We will conduct similar analyses to determine if there was a change in the proportion of patients educated about KAS.

Change in Intent to Refer Patients to Kidney Transplantation

We will assess current referral practices of facilities by surveying the facility medical director about the estimated proportion of patients interested, eligible, and referred for transplant in their facility at baseline and at three months post-intervention. We will also ask questions about the estimated percentage of patients referred for transplant by race/ethnicity and time on dialysis. We will conduct paired t-tests to determine if differences in the proportion of referred patients was greater for intervention vs. control facilities.

Other Covariates

To explore potential modifiers of the effectiveness of this system-level intervention, we will examine facility characteristics (region, facility size, profit status, etc.), characteristics of patients in facilities (e.g., race, insurance status, comorbid conditions, etc.), and contextual neighborhood characteristics such as poverty, education, or income level. We will include process measures for the intervention (receipt of intervention and self-report) to evaluate the potential for future dissemination of interventions to other US dialysis facilities.

Sample Size and Power

Based on 2014 data, if all 18 ESRD Networks participated in the ASCENT study, a total of 1,529 dialysis facilities would be potentially eligible for participation, of which 368 have a waitlisting racial disparity (Figure 2). For the primary outcome of overall waitlisting proportion, an estimated 600 facilities (300 facilities in each study group with an average of 70 pateints per facility) respond, we will be adequately powered (80% at α =0.05) to detect a small difference of 1.9% in the intervention versus control group based on a common waitlisting proportion of 10% at baseline (i.e. a waitlisting difference of 10% in the control group and 11.9% in the intervention group). A two-sided Z-Test (Pooled) statistic and an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.06 were used.

For our other outcome of waitlisting disparity reduction among facilities with a racial disparity at baseline, our sample of 300 in each control and intervention group (total N=600), will achieve 80% power (at α=0.05) to detect a minimum difference of 11% in the waitlisting disparity proportion (% facilities with AA racial disparity) between the intervention vs. control group after 1 year (i.e. A disparity proportion of 21.4% in the intervention group vs. 24.0% in the control group). This calculation assumes a common baseline disparity proportion of 0.24 (24% of facilities had a disparity) at baseline and an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.06 among patients in a facility. The test statistic used is the two-sided Likelihood Score Test (Farrington & Manning) and the significance level of the test is 0.05.

Implementation effect measures

We will use an adaptation of the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) framework18 for evaluating the public health impact of this health policy change.19 This framework builds upon the conceptual models of Rogers20 and Green and Krueter21 in this hybrid effectiveness-implementation study. Adoption will be assessed by participation and use of any intervention materials. Implementation will be assessed by calculating a composite measure, or ‘crude implementation index’ for each facility as the sum of each secondary outcome (dichotomized at the median) of receipt/use of the feedback report and conduct of staff and patient education. We will explore barriers and facilitators to the use of the reports and education. We will conduct qualitative analyses of select medical directors that were successful intervention implementers (n=3) and non-implementers (n=3) at 1 year via phone interviews and online surveys with medical directors from implementers and non-implementers to assess RE-AIM measures.

Discussion

Prior research has documented substantial decreased access to kidney transplant waitlisting and racial disparities in access to kidney transplantation6. A major policy change in the national kidney transplant allocation system in December of 2014 aimed in part at reducing racial disparities among patients waitlisted for transplant7. Preliminary results suggest that racial disparities may have been reduced in transplant rates following the implementation of KAS22. However, due to substantial disparities that exist prior to waitlisting2,4,23, there are numerous more dialysis patients who could potentially benefit from the changes in KAS by increased access to the deceased-donor kidney waitlist.

Prior ESRD Network-led quality improvement interventions have been successful in helping to improve ESRD patient outcomes, including increasing influenza and pneumococcal vaccination rates24, fistula placement through the Fistula First initiative11, and kidney transplant referrals25. While the support of ESRD Networks is a strength for this study, there are several potential limitations of the study design. Network leadership will send both the baseline and follow-up surveys to medical directors to help with study recruitment and data collection, but it is possible that some medical directors will have lower than expected response rates due to differential Network responsiveness and because the project is not mandatory, unlike other previous dialysis-facility based projects we have conducted with success10,13,24. To address this issue, the ASCENT research staff will follow up with dialysis facilities who are unresponsive after the initial and reminder emails from their Network with additional emails and phone calls to achieve maximum participation. It is also possible that medical directors may forward surveys to nurse managers. We will capture role/title within the survey to address this possibility. In addition, because ESRD Network leadership is sending surveys to medical directors, a positive response bias where facilities report that they improve but may not actually change practice may occur. To minimize this bias, we will ensure that medical directors know that facility-identifiable data are blinded to Networks.

An additional limitation could be difficulty to accurately measure uptake of the intervention, given the large-scale nature of the study. For example, dialysis facility staff may report sharing patient videos with patients, but we have no way to track whether patients watched the video and/or were educated by clinicians about transplantation other than through the medical director survey. However, this study is designed to be an effectiveness-implementation study, with the goal of real-world, pragmatic implementation rather than measuring efficacy of the intervention in a controlled setting in which all participants were confirmed to have received the intervention. A strength of this approach is that we will have an estimate of the effectiveness of this intervention approach in the “real world,” which will provide insight into whether the intervention should be disseminated to all U.S. dialysis facilities through the support of their ESRD Networks. An additional potential pitfall of our study is the possibility that knowledge about KAS may increase among medical directors, but that this will not translate into changes in referral and waitlisting for the patient population. Using our process and evaluation measures, we hope to be able to hypothesize reasons for any limits to the success of the intervention.

Despite these limitations, we consider delivery of information about transplant and the new KAS as a first step toward increasing waitlisting overall and reducing disparities in access to transplantation in the United States. Additionally, we will gain essential information from our analyses and implementation measures from surveys and interviews to inform future implementation of the intervention materials to other dialysis facilities across the country. For example, some components of the intervention, such as the patient and staff videos and the medical director webinar, will be made publically available on a website following study end. If the intervention is effective in improving waitlisting or reducing disparity in waitlisting, ESRD Networks could implement the intervention among control dialysis facilities and/or other dialysis facilities not selected for participation in the study.

In conclusion, if effective, the ASCENT study interventions could help extend the reach of a national kidney allocation policy by educating dialysis facility medical directors, staff, and patients about transplantation about the new KAS and thereby increasing the potential impact of KAS on disparity reduction. Conducting this research among dialysis facilities with low waitlisting across the U.S. could help to ensure equitability by reducing racial disparities in and increasing access to kidney transplant waitlisting.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A: ASCENT Baseline Survey for Medical Directors.

Appendix B : United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) Brochure for Control Facilities.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities for funding this project.

Funding Source: National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities

Financial Disclosures

Stephen O. Pastan is a minority shareholder in Fresenius Dialysis College Park, GA.

List of Abbreviations

- U.S.

United States

- ESRD

End-Stage Renal Disease

- ASCENT

Allocation System Changes for Equity in kidNey Transplant

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- CMS

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

- RE-AIM

Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance

- RaDIANT

Reducing Disparities in Access to kidNey Transplantation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

R.E.P participated in study design, intervention development, planning for data collection, helped draft the manuscript and is principal investigator.

K.D.S. participated in intervention development, planning for data collection, and helped draft the manuscript.

M.B. participated in intervention development, planning for data collection, study design, and helped draft the manuscript.

J.G. participated in intervention development, study design and planning for data collection. S.M. participated in study design and intervention development.

C.E. participated in study design and intervention development.

L.P. participated in study design, intervention development and planning for data collection.

T.M. participated in intervention development.

S.K. participated in study design and intervention development.

G.G. participated in intervention development.

A.B. participated in intervention development.

G.R. participated in intervention development.

T.B. participated in intervention development.

N.T. participated in intervention development.

S.C. participated in study design.

S.P. participated in study design and intervention development.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT02879812

References

- 1.USRDS. US Renal Data System 2010Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Hyland SS, McCabe MS, Schenk EA, Liu J. Modifiable patient characteristics and racial disparities in evaluation completion and living donor transplant. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2013 Jun;8(6):995–1002. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08880812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg PP, Frick KD, Diener-West M, Powe NR. Effect of the ownership of dialysis facilities on patients’ survival and referral for transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999 Nov 25;341(22):1653–1660. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911253412205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weng FL, Joffe MM, Feldman HI, Mange KC. Rates of completion of the medical evaluation for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005 Oct;46(4):734–745. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patzer RE, Amaral S, Wasse H, Volkova N, Kleinbaum D, McClellan WM. Neighborhood poverty and racial disparities in kidney transplant waitlisting. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 Jun;20(6):1333–1340. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patzer RE, McClellan WM. Influence of race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status on kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012 Jun 26;8(9):533–541. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resourcs UDoHaH, editor. Network OPaT. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) Policies. Richmond, VA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joshi S, Gaynor JJ, Bayers S, et al. Disparities among Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites in time from starting dialysis to kidney transplant waitlisting. Transplantation. 2013 Jan 27;95(2):309–318. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31827191d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.USRDS. United States Renal Data System, 2015 Annual Data Report: Annual Data Report. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McClellan WM, Hodgin E, Pastan S, McAdams L, Soucie M. A randomized evaluation of two health care quality improvement program (HCQIP) interventions to improve the adequacy of hemodialysis care of ESRD patients: feedback alone versus intensive intervention. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004 Mar;15(3):754–760. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000115701.51613.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch JR, Mohan S, McClellan WM. Achieving the goal: results from the Fistula First Breakthrough Initiative. Current opinion in nephrology and hypertension. 2011 Nov;20(6):583–592. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32834b33c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patzer REPS, Plantinga L, Gander J, Sauls L, Krisher J, Mulloy L, Gibney EM, Browne T, Zayas C, McClellan WM, Jacob Arriola K, Pastan SO. A Randomized Trial to Reduce Disparities in Referral for Transplant Evaluation. Journal of American Society of Nephrology. 2016 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016030320. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patzer RE, Paul S, Plantinga L, et al. A Randomized Trial to Reduce Disparities in Referral for Transplant Evaluation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 Oct 13; doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016030320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foy R, Eccles MP, Jamtvedt G, Young J, Grimshaw JM, Baker R. What do we know about how to do audit and feedback? Pitfalls in applying evidence from a systematic review. BMC health services research. 2005;5:50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curran GMBM, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation Hybrid Designs: Combining Elements of Clinical Effectiveness and Implementation Research to Enhance Public Health Impact. Medical care. 2012;50(3):217–226. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jilcott SAA, Sommers J, Glasgow RE. Applying the RE-AIM framework to assess the public health impact of policy change. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;34(2):105–114. doi: 10.1007/BF02872666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang JaZS. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. American journal of public health. 1999 Sep;89(9):1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jilcott S, Ammerman A, Sommers J, Glasgow RE. Applying the RE-AIM framework to assess the public health impact of policy change. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2007 Oct;34(2):105–114. doi: 10.1007/BF02872666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.EM R. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th. New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green LWKM. Health Promotion Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Massie AB, Luo X, Lonze BE, et al. Early Changes in Kidney Distribution under the New Allocation System. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 Aug;27(8):2495–2501. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015080934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johansen KL, Zhang R, Huang Y, Patzer RE, Kutner NG. Association of race and insurance type with delayed assessment for kidney transplantation among patients initiating dialysis in the United States. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2012 Sep;7(9):1490–1497. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13151211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bond TC, Patel PR, Krisher J, et al. A group-randomized evaluation of a quality improvement intervention to improve influenza vaccination rates in dialysis centers. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011 Feb;57(2):283–290. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patzer RE, Gander J, Sauls L, et al. The RaDIANT community study protocol: community-based participatory research for reducing disparities in access to kidney transplantation. BMC nephrology. 2014;15:171. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-15-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A: ASCENT Baseline Survey for Medical Directors.

Appendix B : United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) Brochure for Control Facilities.