Abstract

Background and Purpose

Brain iron-deposition has been implicated as a major culprit in the pathophysiology of neurodegeneration. However, the quantitative assessment of iron in behavioralvariant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD and primary progressive aphasia (PPA) brains has not been performed. The aim of our study was to investigate the characteristic iron levels in the FTD subtypes using susceptibility weighted imaging, and report its association with behavioural profiles.

Materials and Methods

This prospective study included 46 FTD patients (34 bvFTD and 12 PPA) and 34 age-matched normal controls. We performed behavioural and neuropsychological assessment in all the subjects. The quantitative iron load was determined on SWI in the superior frontal gyrus and temporal pole, precentral gyrus, basal ganglia, anterior cingulate, frontal white matter, head and body of hippocampus, red nucleus, substantia nigra, insula and dendate nucleus. A linear regression analysis was performed to correlate between iron content and behavioural scores in patients.

Results

The iron content of bilateral superior frontal and temporal gyrus, anterior cingulate, putamen, right hemispheric precentral gyrus, insula, hippocampus and red nucleus was higher in bvFTD than controls. PPA patients had increased iron levels in the left superior temporal gyrus. In addition, right superior frontal gyrus iron deposition discriminated bvFTD from PPA. A significant correlation was found between apathy and iron content in superior frontal gyrus, and disinhibition and iron content in putamen.

Conclusion

Quantitative assessment of iron deposition using SWI may serve as a new biomarker in the diagnostic work up of FTD and help distinguish FTD subtypes.

INTRODUCTION

Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) is an early onset dementia characterized by changes in behavior, personality, and language abilities. The major clinical presentations are frontal or behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD) with personality and behavioral changes and the language variant known as primary progressive aphasia (PPA) with either prominent isolated expressive language deficit, Progressive Non-fluent Aphasia (PNFA), or with prominent language comprehension and semantics deficits, Semantic dementia (SD).1 Since standard neuropsychological testing often fails to detect the disease in the early stages of the disease course, and the behavioral changes predate neuropsychological deficits,2 a major clinical challenge is to develop a biomarker for the early and accurate diagnosis of FTD.

Several neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD)3, Parkinson’s disease (PD)4, Multiple sclerosis (MS)5, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)6’7, neuroferrinopathy, panthothenate-kinase-2-associated neurodegeneration (NBIA-1), and aceruloplasminemia have been found to be associated with excessive iron accumulation. Also, our previous study in ALS demonstrated abnormal brain iron deposition in the posterior bank of motor cortex, and this could be a potential biomarker for ALS.9 Recently, there has been an increasing interest in vivo quantitative estimation of non-heme iron in the pathophysiology of AD.10,11 Postmortem studies indicate neurodegeneration with brain iron deposition in FTD-ALS12, and Pick disease.13 A recent study in the post-mortem brains suggested that iron-impaired homeostasis possibly plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD).14

The neuropathological basis of neurodegeneration in FTLD is highly linked with different proteinopathies such as TDP-43 and FUS proteins6,15, which has been found to be responsible for the focal atrophy in fronto-temporal and subcortical areas.17 De Reuck et al, found a significantly higher iron load in FUS and TDP subgroups than those with tau-FTLD. Although it is widely accepted that the excessive iron accumulation contributes to neurodegeneration, it is not yet clear whether this is a primary or secondary event of disease process. Iron is an important element for normal brain function due to its critical role in oxidative metabolism, DNA synthesis and other enzymatic cellular processes. The metabolism of iron depends on human haemochromatosis protein (HFE) located on the cell membrane which regulates uptake of iron by modulating the binding affinity of the transferrin receptor for iron-loaded transferrin.18 Also the line of evidence indicates that the genetic variant of HFE protein, namely H63D polymorphism in FTLD can foster the increased iron deposition in the basal ganglia regions.19 In the light of these new findings, search for a biomarker capable of detecting cell death in anatomically specific patterns could be useful, similar to FDG PET imaging in dementia, but at a lower cost and without any ionizing radiation exposure.

In recent years, susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) has been confirmed as a tool to quantify iron deposition in the brain which exploits magnetic susceptibility differences between tissues.20,21 SWI is a 3D gradient technique which utilizes both magnitude and phase data separately and together, to enhance the susceptibility differences between tissues. SWI has been shown to be more sensitive to non-heme iron (ferritin) than other conventional techniques.22 The present study was conducted to unravel the regional changes in the iron concentration in the brains of patients with FTD. This in vivo measurement could potentially offer a good diagnostic tool for identifying the disease and studying the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. The goal of the present study was to quantify iron deposition in bvFTD and PPA in comparison with age-matched controls using SWI and to correlate these with behavioral test measures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

A total of 46 FTD (34 bvFTD, 12 PPA (7 SD and 5 PNFA) patients and 34 controls were included in the study after getting signed informed consent from the participants and their caregivers. The study had approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC). The patients were recruited from the Memory and Neurobehavioral clinic at a tertiary referral centre in Trivandrum city, Kerala, India. The initial clinical diagnosis of FTD was established by an experienced cognitive neurologist (P.S.M) as per the published FTD consensus criteria1, and subsequently confirmed by neuropsychological, and neuroimaging examinations. All bvFTD patients met with recently published criteria by Rascovsky et al23 and PPA with Mesulam criteria.24 We excluded patients who had a past history of cerebral ischemic infraction or hemorrhage, head trauma, alcohol abuse, cardio vascular and major psychiatric diseases, past history of depressive illness and epilepsy or other neurological disorders. The age matched controls with no past history of major neurological or psychiatric illnesses and no contraindications for MRI were recruited from the local community and subjected to the same assessment as for FTD.

The cognitive assessment was performed using a neuropsychological battery that was validated for the local elderly population as described previously.26 Test battery included the brief cognitive test of the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), and the detailed global cognitive test of the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (ACE). Furthermore, patients underwent a behavioral assessment test using the Frontal System Behavioral Scale (FrSBe), which investigates behaviors associated with frontal system damage such as apathy, disinhibition and executive dysfunction.

Image acquisition

All images were acquired on a 1.5 Tesla (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) whole body scanner equipped with an eight channel phase array head coil. In all the subjects sagittal T1-weighted images were acquired to locate the prescribed positions of the anterior-posterior commissures (AC-PC). Conventional T1W, T2W images were acquired with MRI slices aligned parallel to the AC-PC line to screen the subjects for other cerebral anatomical abnormalities such as traumatic brain injury and old hemorrhagic infarcts etc. SWI imaging was performed with a 3D spoiled gradient recalled echo sequence with the following parameters: TR/TE: 49/40 ms, flip angle: 20°, slice thickness: 2.1mm, no of slices: 56, FOV: 250×203 mm, matrix size: 260x 320. For the analysis, the images were high-pass filtered by using a low spatial frequency kernel of central matrix size 64×64. The resulting image is the SWI filtered phase image. The filtered phase image served as an indicator of phase variations and hence the concentration of iron. The details of the measurement of iron in the order of μg Fe/g tissue is described elsewhere.9,20,21. The 3-D FLASH volumetric scans were also acquired for the anatomical localization based on surface landmarks.

Image analysis

All the SWI images were visually examined by two certified and experienced neuroradiologists (C.K) and (B.T). The high-pass filtered images were analyzed using SPIN (Signal processing In NMR, MRI Institute for Biomedical Research Detroit, MI, USA) software. Both the SWI and Phase images were used for the analysis. Initially, the brightness and contrast of the images were adjusted and magnified two times to obtain the anatomical landmark of each structure. Secondly, ROIs were determined and drawn manually on respective SWI image slices with extreme care to minimize partial volume effects. The regions were selected based on known functions of different parts of the brain and the published structural MRI studies which had objectives comparable to our study. Many of these studies have described significant GM volume loss in frontal, insula, anterior cingulate, caudate, putamen, thalamus and temporal polar regions in bvFTD(27,28,29) and predominant temporal (temporal pole, anterior hippocampus) and extra temporal (ventromedial prefrontal cortex, insula, anterior cingulate, caudate) regions in PPA.(28,30,31) Hence, the ROIs drawn on both hemispheres taking the help of e-anatomy of IMAIOS (https://www.imaios.com/en/e-Anatomy/Head-and-Neck/Brain-MRI-3D) and included: the GM at the precentral gyrus (PCG) just anterior to central sulcus, adjacent subcortical WM and CSF in the central sulcus, superior frontal gyrus (SFG) medial to superior frontal sulcus, temporal pole (TP), Insula (IN), basal ganglia regions(caudate(CAU), putamine (PUT), globus pallidus (GP), substantia nigra (SN), red nucleus (RN), frontal WM (FWM), anterior cingulate (AC), defined by the grey matter abutting and posterior to the cingulate sulcus along with adjacent medial frontal lobe, hippocampus (HP) that included its head and body, and finally, dentate nucleus (DN) (Supplementary Figure 1). Inferior and middle fronto-temporal regions were avoided in the analysis specifically to reduce the contribution of susceptibility artifacts of skull-base. Finally, each ROI were copied to phase images for measuring the mean phase values. In order to ensure, the consistency in measurement, phase values were measured independently by the two observers (S.R and R.M.S).

In order to compare data across patients, the CSF in each patient was assumed to contain zero iron.32 Hence, the iron content in an ROI is directly proportional to the shift in phase between the CSF and the particular ROI.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York). The age and sex distribution between subjects were compared by student t test and χ2 test respectively. The inter rater agreement between the two observers on iron measurement was calculated using kappa statistics. The comparison between mean values of neuropsychological scores, behavioural scores and iron in each ROI between groups was performed by One Way ANOVA analysis with Posthoc Bonferroni procedure. All statistical test was set at a significance of p<0.05. Finally, a linear regression analysis was performed to assess the correlation between iron content and behavioural scores.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics

The demographic, neuropsychological and behavioral data are summarized in Table1. The patients and controls were comparable on age (p=0.5), and gender (P=0.33). The bvFTD patients were significantly worse than PPA on FrSBe scores of apathy, disinhibition and executive dysfunction. Furthermore, bvFTD and PPA demonstrated pathological scores in ACE and MMSE compared to controls. The direct comparison between patient groups revealed significantly greater behavioural scores of disinhibition and executive dysfunction in bvFTD compared to PPA.

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinical and behavioral data comparison

| Controls | bvFTD | PPA | P value (Group effect) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(Yrs)a | 61.07±6.15 | 61.18±11.96 | 64.64±3.98 | 0.55 |

| Sexb | 18/16 | 23/11 | 8/4 | 0.33 |

| FrSBe | ||||

| Apathy | 19.36±10.55 | 30.26±11.72 | 27.58±13.16 | 0.003 |

| Disinhibition | 15.86±2.12 | 33.74±9.27 | 24±8.07 | <0.001 |

| Executive Dysfunction | 20.41±5.68 | 56.65±16.93 | 34±9.73 | <0.001 |

| Neuropsychological Test | ||||

| Scores | ||||

| MMSE | 28.66±1.11 | 18.9±7.71 | 22.82±5.51 | <0.001 |

| ACE | 92.45±7.03 | 53.29±24.9 | 55.9±20.59 | <0.001 |

Students t test

Chisquare test

Posthoc Oneway ANOVA

Bonferroni posthoc tests compare differences between groups

bvFTD -frontal variant frontotemporal Dementia, PPA- primary progressive aphasia, MMSE- Mini-Mental State Examination, ACE- Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination, both MMSE and ACE was absent in 8 fvFTD patients and 2 PPA patients.

FrSBe- frontal System Behavioural Scale

Quantitative measurement of brain iron content in patient with FTD

We observed a very good inter- rater agreement (k= 0.88) between the two raters in the quantitative measurement of iron values.

The quantitative assessment of brain iron deposition (μg Fe/gm of tissue) in the various regions in FTD patients demonstrated significantly increased iron levels in bilateral SFG (p<0.001), bilateral TP (P<0.001), bilateral AC (p=0.001 for right and p=0.034 for left), bilateral PUT (p=0.003 for right and p=0.037 for left), RPCG (p=0.011), RIN (p=0.01), RHP (p=0.024), and RRN (p=0.02), in bvFTD compared to controls (Table 2).

Table 2.

Iron content (μg Fe/g of tissue) of each region in bvFTD, PPA and control group

| Region | Controls | bvFTD | PPA | Bonferroni corrected P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bvFTD vs Controls | PPA vs Controls | bvFTD vs PPA | ||||

| LSFG | 13.17±5.78 | 24.35±10.02 | 18.61±4.23 | <0.001 | 0.123 | 0.09 |

| RSFG | 12.55±5.51 | 25.36±9.82 | 18.45±5.11 | <0.001 | 0.75 | 0.03 |

| LPCG | 35.16±10.03 | 40.17±7.39 | 37.14±8.28 | 0.064 | 1.00 | 0.914 |

| RPCG | 33.46±14.29 | 41.74±7.1 | 39.2±12.11 | 0.012 | 0.416 | 1.00 |

| LAC | 17.21±7.71 | 21.31±5.72 | 18.57±4.21 | 0.034 | 1.00 | 0.634 |

| RAC | 16.72±5.7 | 22.15±6.1 | 17.97±3.79 | 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.092 |

| LIN | 12.44±5.4 | 15.91±7.09 | 15.33±5.33 | 0.074 | 0.512 | 1.00 |

| RIN | 11.86±5.59 | 16.55±7.83 | 14.14±2.78 | 0.01 | 0.883 | 0.793 |

| LCAU | 25.76±12.05 | 29.00±12.46 | 27.19±4.88 | 0.756 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| RCAU | 24.96±13.46 | 31.43±13.79 | 25.87±7.32 | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.609 |

| LPUT | 20.96±11.23 | 26.98±8.95 | 21.18±5.33 | 0.037 | 1.00 | 0.227 |

| RPUT | 20.61±9.5 | 27.84±8.12 | 21.13±6.49 | 0.003 | 0.06 | 0.066 |

| LGP | 27.58±10.25 | 30.66±9.08 | 28.39±7.58 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| RGP | 26.65±7.27 | 32.3±11.51 | 28.11±8.68 | 0.053 | 1.00 | 0.585 |

| LFWM | 13.96±6.61 | 14.67±5.91 | 15.21±3.17 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| RFWM | 13.65±5.98 | 17.08±6.77 | 13.30±4.64 | 0.078 | 1.00 | 0.217 |

| LHP | 12.28±7.60 | 15.64±7.07 | 15.58±4.09 | 0.156 | 0.493 | 1.000 |

| RHP | 11.95±6.6 | 17.01±8.82 | 14.89±4.21 | 0.024 | 0.671 | 1.00 |

| LTP | 13.72±5.44 | 21.90±8.69 | 19.67±5.16 | <0.001 | 0.041 | 1.00 |

| RTP | 13.25±5.9 | 23.41±8.71 | 18.77±4.35 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.166 |

| LRN | 27.29±11.07 | 30.39±10.99 | 27.90±7.99 | 0.709 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| RRN | 24.21±9.13 | 31.58±12.66 | 24.69±9.05 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 0.177 |

| LSN | 26.78±11.63 | 30.90±9.90 | 28.05±10.64 | 0.365 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| RSN | 26.64±12.49 | 31.0±11.25 | 27.85±11.09 | 0.403 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| LDN | 20.71±8.84 | 23.26±7.86 | 21.41±7.47 | 0.633 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| RDN | 19.93±6.5 | 24.03±8.41 | 20.47±3.96 | 0.064 | 1.00 | 0.424 |

Bonferroni posthoc tests compare differences between groups

R-right, L-left, bvFTD –frontal variant frontotemporal Dementia, PPA- primary progressive aphasia

SFG- superior frontal gyrus, PCG- precentral gyrus just anterior to central sulcus, AC- grey matter abutting and posterior to the cingulate sulcus along with adjacent medial frontal lobe, IN-insula, CAU-caudate, PUT-putamen, GP-globus pallidus, FWM-frontal white matter, HP-head and body of hippocampus, TP-temporal pole, RN-red nucleus, SN-substantia nigra, DN-dentate nucleus.

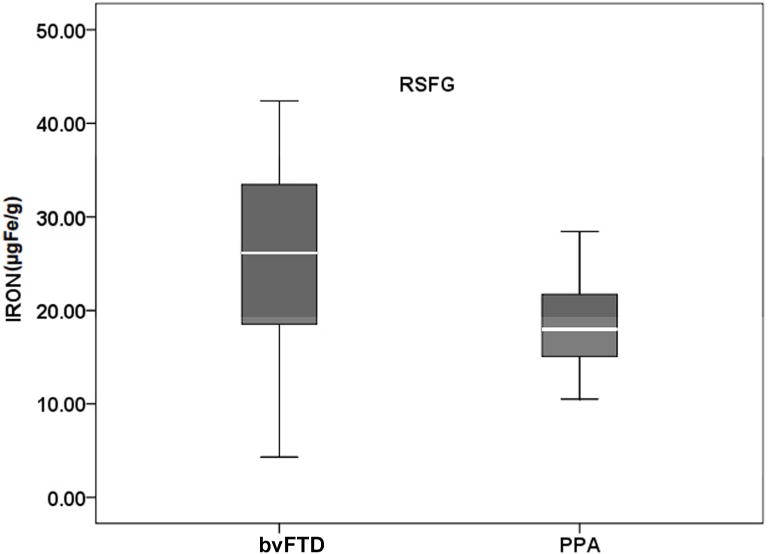

While in patients with PPA, significant iron level was noted in LTP (p=0.041) and trend for significance in RTP (p= 0.073). A direct comparison between bvFTD and PPA showed an increased iron deposition in RSFG (p = 0.03) in bvFTD (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Boxplot showing iron content in the superior frontal gyrus in the direct comparison between patients. bvFTD indicates frontal variant FTD and PPA indicates primary progressive aphasia.

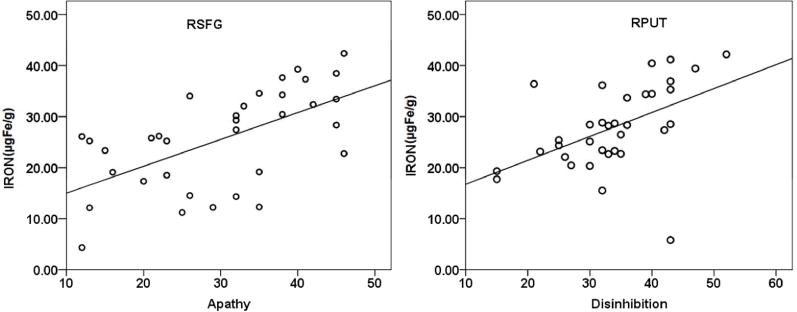

Relationship between cortical brain iron deposition and Behavioural scores

Linear regression analysis examining the relationship between cortical iron deposition and FrSBe subscores, found significant positive association between the iron content in RSFG with the apathy score (r2 =0.36, p<0.001) and RPUT with disinhibition scores (r2=0.25, p=0.003) (Figure 2). No association was found between the iron content of any of the examined regions and executive dysfunction scores. The patients with PPA did not show any correlation with iron content and any of the behavioural scores.

Figure 2.

Correlation between iron concentration (μg Fe/gm of tissue) in (a) RSFG and Apathy (b) RPUT and Disinhibition scores in bvFTD patients.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we quantified the extent of brain iron deposition in the cortical and subcortical regions of FTD patients in comparison with controls and correlated this with behavioural measures. To our knowledge, no other previous studies have performed a quantitative in vivo assessment of brain iron deposition in FTD patients.

Pathological accumulation of brain iron is shown in various neurodegenerative diseases including AD.33 A previous autopsy study using 7.0T MRI on the detection of micro bleeds in FTD demonstrated an iron overload in the basal ganglia.34 The investigators also found a large number of microbleeds in the frontal cerebral cortex using gradient-echo T2*-weighted MRI sections. Also a recent autopsy study confirmed the presence of Fe in deep gray nuclei in FTD brains.14 Activated microglial cells and iron are known to accumulate at the neurodegenerative sites in AD and PD.35 These microglial cells have been implicated in maintaining the iron homeostasis in brain by scavenging excess iron.36 It has been reported that chronic microglial activation in FTD can cause the expression of progranulin and the production of pro-inflammatory mediators by phosphor-tau-positive neurons which may contribute to neuronal death and disease progression.37

Prior studies proved the efficacy of SWI in the quantitative assessment of cerebral iron content in dementia subjects.3’4’10 Wang et al identified increased iron content in the HP, head of CAU, lenticular nucleus and thalamus in amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment and AD compared to controls. Further, Zhou et al demonstrated that SWI phase values of bilateral HP, GP, CAU, SN, and PUT were significantly different between AD and controls, which had a higher correlation coefficient with MMSE scores. Recently, Wu et al suggested that a quantitative assessment of iron in SN and GP using SWI may be useful for the early diagnosis and evaluation of degree of disease in PD.

The strength of the present study is the quantitative assessment of brain iron deposition in the frontal, temporal and basal ganglia regions in FTD subtypes in comparison to non-demented controls using SWI. We found significantly increased levels of iron in the bilateral SFG, TP, AC and PUT along with right hemispheric insula, PCG, HP, and RN of bvFTD patients in comparison to controls. The patients with PPA only showed significant iron levels in the left TP in comparison with controls. A direct comparison revealed significant iron deposition in the RSFG in bvFTD patients.

Earlier studies proved significant GM and WM degeneration in fronto-insular-striatial-temporal regions in bvFTD27,38,39 and more severe temporal atrophy in PPA.39,40 Recently, De Reuck et al analysed the post-mortem brains of patients with neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular disease and observed most significant iron deposition in the claustrum, caudate and putamen and comparatively lesser significant deposition in GP, thalamus and subthalamic nucleus in FTD compared with controls. These findings support our observation of increased iron deposition in basal ganglia regions. Moreover, our volumetric results in the same patient group showed characteristic atrophy patterns in the basal ganglia (unpublished data), which corroborate previous findings.41 Notably, a prior tractography analysis in human brain demonstrated well-established connections within the fronto-striatial networks.42 The significant iron deposition in the RN of bvFTD may be due to its strong functional coherence with prefrontal, insula, temporal, parietal, thalamic and hypothalamic regions.43 In fact, the amount of iron deposition in SFG and PUT correlated with the behavioural manifestations, as measured by FrSBe, which has been implicated in the behavioural studies in FTD.44,45 The role of PUT in disinhibition may be due to its afferent connections to the medial, orbital and dorsolateral prefrontal regions as well as its link with prefrontal and motor circuits.46 Therefore the regional iron deposition, as measured by SWI, may be used as a novel biomarker in the diagnosis of FTD subtypes.

There are some limitations in this study. Our sample size in PPA is relatively small. Also, some of the subjects were unable to complete the neuropsychological tests due to more advanced stage of the disease. Although, our patient group had characteristic symptomatology, and conformed to the diagnostic criteria, pathological confirmation of FTD was not established for all subjects. Hence, future longitudinal studies on larger samples with neuropathological data and higher resolution scanners (3Tesla or 7Tesla) can help verify and consolidate our conclusions. Nevertheless, this study provides an insight into an angle for pursuing the search for biomarkers in FTD.

In summary, the results of the study showed that SWI could be a potential biomarker to measure iron deposition in the FTD brain and iron increases in the frontal and temporal regions of the patients. The study also demonstrated a significant correlation between regional iron content and behavioural profiles.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Representative slice in bvFTD subject showing regions of interest where phase is measured in a) superior frontal gyrus medial to superior frontal sulcus (SFG) b) the precentral gyrus just anterior to central sulcus GM, and central sulcus CSF(PCG) c) the globus pallidus(GP:1,2), putamen(PUT:3,4) and caudate nucleus(CAU: 5,6), insula (IN:7,8), and frontal white matter(FWM:9,10) d) anterior cingulate with adjacent medial frontal lobe (AC) e) temporal pole (TP) f) dentate nucleus(DN) g) red nucleus (RN: 1,2), substantia nigra (SN:3,4) and h) head and body of hippocampus(HP).

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by grants from National Institute on Aging (NIA), USA (grant no. R21AG029799 and R01AG039330-01) to PSM.

ABBREVIATIONS

- bvFTD

behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia

- FrSBe

frontal system behavioural scale

- ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- MMSE

Mini Mental State Examination

- ACE

Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination

- SFG

superior frontal gyrus

- TP

temporal pole

- AC

anterior cingulate

- IN

insula

- CAU

caudate

- PUT

putamen

- GP

globus pallidus

- FWM

frontal white matter

- HP

hippocampus

- RN

red nucleus

- SN

substantia nigra

- DN

dentate nucleus

References

- 1.Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546–54. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perry RJ, Graham A, Williams G, Rosen, et al. Patterns of frontal lobe atrophy in frontotemporal dementia: a volumetric MRI study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22:278–87. doi: 10.1159/000095128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou B, Li S, Huijin H, et al. The evaluation of iron content in Alzheimer’s disease by magnetic resonance imaging: Phase and R2* methods. Advances in Alzheimer’s Disease. 2013;2:51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu S-F, Zhu Z-F, Kong Y, et al. Assessment of cerebral iron content in patients with Parkinson’s disease by the susceptibility-weighted MRI. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:2605–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ropele S, de Graaf W, Khalil M, et al. MRI assessment of iron deposition in multiple sclerosis. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI. 2011;34:13–21. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adachi Y, Sato N, Saito Y, et al. Usefulness of SWI for the Detection of Iron in the Motor Cortex in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Neuroimaging Off J Am Soc Neuroimaging. 2015;25:443–51. doi: 10.1111/jon.12127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwan JY, Jeong SY, Van Gelderen P, et al. Iron accumulation in deep cortical layers accounts for MRI signal abnormalities in ALS: correlating 7 tesla MRI and pathology. PloS One. 2012;7:e35241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batista-Nascimento L, Pimentel C, Andrade Menezes R, et al. Iron and Neurodegeneration: From Cellular Homeostasis to Disease, Iron and Neurodegeneration: From Cellular Homeostasis to Disease. Oxidative Med Cell Longev Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2012;30:e128647. doi: 10.1155/2012/128647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheelakumari R, Madhusoodanan M, Radhakrishnan A, et al. A Potential Biomarker in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Can Assessment of Brain Iron Deposition with SWI and Corticospinal Tract Degeneration with DTI Help? Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;37:252–8. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang D, Zhu D, Wei X-E, et al. Using susceptibility-weighted images to quantify iron deposition differences in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol India. 2013;61:26–34. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.107924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raven EP, Lu PH, Tishler TA, et al. Increased iron levels and decreased tissue integrity in hippocampus of Alzheimer’s disease detected in vivo with magnetic resonance imaging. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2013;37:127–36. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santillo AF, Skoglund L, Lindau M, et al. Frontotemporal dementia-amyotrophic lateral sclerosis complex is simulated by neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:298–300. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181a2b76b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehmann WD, Alauddin M, Hossain TI, et al. Brain trace elements in Pick’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1984;15:102–4. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Reuck JL, Deramecourt V, Auger F, et al. Iron deposits in post-mortem brains of patients with neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular diseases: a semi-quantitative 7.0 T magnetic resonance imaging study. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:1026–31. doi: 10.1111/ene.12432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackenzie IA, Neumann M, Bigio EH, et al. Nomenclature and nosology for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: an update. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2010;119:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0612-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neumann M, Rademakers R, Roeber S, et al. A new subtype of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with FUS pathology. Brain J Neurol. 2009;132:2922–31. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garibotto V, Borroni B, Agosti C, Premi E, et al. Subcortical and deep cortical atrophy in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:875–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feder JN, Penny DM, Irrinki A, et al. The hemochromatosis gene product complexes with the transferrin receptor and lowers its affinity for ligand binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:1472–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gazzina S, Premi E, Zanella I, et al. Iron in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration: A New Subcortical Pathological Pathway? Neurodegener Dis. 2016;16:172–8. doi: 10.1159/000440843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haacke EM, Ayaz M, Khan A, et al. Establishing a baseline phase behavior in magnetic resonance imaging to determine normal vs. abnormal iron content in the brain. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI. 2007;26:256–64. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haacke EM, Makki M, Ge Y, et al. Characterizing iron deposition in multiple sclerosis lesions using susceptibility weighted imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI. 2009;29:537–44. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas B, Somasundaram S, Thamburaj K, et al. Clinical applications of susceptibility weighted MR imaging of the brain – a pictorial review. Neuroradiology. 2007;50:105–16. doi: 10.1007/s00234-007-0316-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134:2456–77. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mesulam MM. Primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:425–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76:1006–14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathuranath PS, Cherian JP, Mathew R, et al. Mini mental state examination and the Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination: effect of education and norms for a multicultural population. Neurol India. 2007;55:106–10. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.32779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertoux M, O’Callaghan C, Flanagan E, et al. Fronto-Striatal Atrophy in Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Neurol. 2015;6:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen T, Bertoux M, O’Callaghan C, et al. Grey and white matter brain network changes in frontotemporal dementia subtypes. Transl Neurosci. 2013;4:410–418. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whitwell JL, Przybelski SA, Weigand SD, et al. Distinct anatomical subtypes of the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia: a cluster analysis study. Brain J Neurol. 2009;132:2932–2946. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seelaar H, Rohrer JD, Pijnenburg YAL, et al. Clinical, genetic and pathological heterogeneity of frontotemporal dementia: a review. J. Neurol. Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:476–486. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.212225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duval C, Bejanin A, Piolino P, et al. Theory of mind impairments in patients with semantic dementia. Brain. 2012;135:228–241. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haacke EM, Cheng NYC, House MJ, et al. Imaging iron stores in the brain using magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;23:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rouault TA, Cooperman S. Brain iron metabolism. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13:142–8. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Reuck J, Deramecourt V, Cordonnier C, et al. Detection of microbleeds in post-mortem brains of patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a 7.0-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging study with neuropathological correlates. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:1355–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ward RJ, Crichton RR, Taylor DL, et al. Iron and the immune system. J Neural Transm. 2010;118:315–28. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0479-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Connor JR, Boeshore KL, Benkovic SA, et al. Isoforms of ferritin have a specific cellular distribution in the brain. J Neurosci Res. 1994;37:461–5. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490370405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ridolfi E, Barone C, Scarpini E, et al. The role of the innate immune system in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration: an eye on microglia. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/939786. 939786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boccardi M, Sabattoli F, Laakso MP, et al. Frontotemporal dementia as a neural system disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borroni B, Brambati SM, Agosti C, et al. Evidence of white matter changes on diffusion tensor imaging in frontotemporal dementia. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:246–51. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agosta F, Scola E, Canu E, et al. White Matter Damage in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration Spectrum. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22:2705–2714. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Josephs KA. Frontotemporal dementia and related disorders: deciphering the enigma. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:4–14. doi: 10.1002/ana.21426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leh SE, Ptito A, Chakravarty MM, et al. Fronto-striatal connections in the human brain: a probabilistic diffusion tractography study. Neurosci Lett. 2007;419:113–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nioche C, Cabanis EA, Habas C. Functional Connectivity of the Human Red Nucleus in the Brain Resting State at 3T. Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:396–403. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eslinger PJ, Moore P, Antani S, et al. Apathy in frontotemporal dementia: behavioral and neuroimaging correlates. Behav Neurol. 2012;25:127–36. doi: 10.3233/BEN-2011-0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Halabi C, Halabi A, Dean DL, et al. Patterns of striatal degeneration in frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27:74–83. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31824a7df4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macfarlane MD, Jakabek D, Walterfang M, et al. Striatal Atrophy in the Behavioural Variant of Frontotemporal Dementia: Correlation with Diagnosis, Negative Symptoms and Disease Severity. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0129692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Representative slice in bvFTD subject showing regions of interest where phase is measured in a) superior frontal gyrus medial to superior frontal sulcus (SFG) b) the precentral gyrus just anterior to central sulcus GM, and central sulcus CSF(PCG) c) the globus pallidus(GP:1,2), putamen(PUT:3,4) and caudate nucleus(CAU: 5,6), insula (IN:7,8), and frontal white matter(FWM:9,10) d) anterior cingulate with adjacent medial frontal lobe (AC) e) temporal pole (TP) f) dentate nucleus(DN) g) red nucleus (RN: 1,2), substantia nigra (SN:3,4) and h) head and body of hippocampus(HP).