Abstract

Epidemiological evidence implicates excess adipose tissue in increasing cancer risk. Despite a steeply-rising global prevalence of obesity, how adiposity contributes to transformation (stage a non-tumorigenic cell undergoes to become malignant) is unknown. To determine the factors in adipose tissue that stimulate transformation, we used a novel ex vivo system of visceral adipose tissue (VAT)-condition medium-stimulated epithelial cell growth in soft agar. To extend this system in vivo, we used a murine lipectomy model of ultraviolet light B (UVB)-induced, VAT-promoted skin tumor formation. We found that VAT from mice and obese human donors stimulated growth in soft agar of non-tumorigenic epithelial cells. The difference in VAT activity was associated with fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2) levels. Moreover, human and mouse VAT failed to stimulate growth in soft of agar in cells deficient in FGFR-1 (FGF2 receptor). We also demonstrated that circulating levels of FGF2 were associated with non-melanoma tumor formation in vivo. These data implicate FGF2 as a major factor VAT releases to transform epithelial cells – a novel, potential pathway of VAT-enhanced tumorigenesis. Strategies designed to deplete VAT stores of FGF2 or inhibit FGFR-1 in abdominally obese individuals may be important cancer prevention strategies as well as adjuvant therapies for improving outcomes.

Introduction

The carcinogenic impact of having excess adipose tissue is profound but exactly how adiposity affects carcinogenesis hasn’t been fully uncovered (1, 2). This is a significant issue, since 38% of American adults and 17% of children are obese (3), and U.S. obesity rates are predicted to hit 42% by 2050 (4). Moreover, obesity is overtaking tobacco use as the number one preventable risk factor for cancer (5). Adipose tissue does not merely store energy as fat. It is metabolically active, secreting large numbers of adipokines, cytokines, and growth factors (6, 7). Obesity and/or high-fat diets (HFDs) alter adipose tissue metabolic and endocrine functions by elevating plasma free fatty acids and pro-inflammatory adipokines and cytokines, increasing adipocyte size, and stimulating immune cell infiltration (8, 9). Although mechanistic insights have informed the roles of systemic inflammation, endocrine disruption, and adipose tissue dysfunction, such as macrophage infiltration and increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, in cancer progression (10–13), they fall short of explaining the epidemiological link between obesity and increased cancer incidence (14, 15). This manuscript will address this knowledge gap by demonstrating how adipose tissue can influence cell transformation (post-initiation steps or stages a cell undergoes to become malignant).

Many of the changes observed in adipose tissue in obesity preferentially influence visceral adipose tissue (VAT, around internal organs); as opposed to subcutaneous adipose tissue found underneath the skin (10–12, 16). Although VAT has been extensively explored as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, hypertension and type-2 diabetes (17), emerging epidemiology demonstrates an association between VAT and cancer risk. Visceral adiposity is independently and positively associated with cancer risk in older men (14). Large waist circumferences and waist-to-hip ratios - indicators of VAT, are strongly associated with colon and breast cancer risk (15, 18–22).

Animal models have linked VAT in HFD-fed mice to skin and colon cancer by showing a reduction in tumors with surgical removal of VAT (23, 24). Our previous studies have demonstrated that parametrial adipose tissue removal in HFD-fed mice inhibited ultraviolet B (UVB)-induced formation of squamous cell carcinomas by 75–80% when compared to sham-operated control mice (24). Parametrial adipose tissue is the largest visceral fat pad in female mice and closest analog to human omental adipose tissue, the fat pad implicated in cardiovascular disease, hypertension and diabetes. Links between VAT and cancer at distant sites (skin and breast), suggest a systemic mechanism. Other groups have hypothesized that leptin, glucose, insulin and inflammatory cytokines - systemic markers of obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation, may contribute to tumor promotion as well (8).

Here we set out to investigate which factors released by VAT are responsible for increasing cancer risk. To achieve this, we performed gain- and loss-of-function studies together with animal- and cell-based tests to demonstrate a potentially novel function of VAT-secreted factors for stimulating epithelial cell transformation. We utilized our previously published model of HFD-promoted, UVB-induced skin tumor formation (24), to study the systemic effects of visceral adiposity in vivo. We also developed a novel system to determine the ability of factors released and filtered from VAT to stimulate cell transformation of non-transformed but transformation-capable JB6 P+ (epidermal) and NMuMG (mammary epithelial) cells. The mouse Balb/c epidermal, JB6 P+ cell line has been utilized as well-characterized in vitro model for neoplastic transformation for tumor promoters (25–36). These cells and NMuMG cells, are non-tumorigenic (they fail to form tumors when injected into immunocompromised mice) (37). We measure their transformation following promoter stimulation using an anchorage-independent proliferation assay, in which only transformed cells can grow to form colonies (37). When cells from colonies are isolated, they form tumors when injected into mice (37). Using this assay, we found that FGFR-1 is critical for adipose tissue-stimulated transformation of skin and mammary epithelial cells and that FGF2 is one of the critical players in FGFR-1 driven transformation.

The rationale for investigating both skin and breast cancer is that, first, they are among the most common cancers. Second, epidemiological evidence implicates VAT in increasing pre- and post-menopausal breast cancer (18–21). There is conflicting evidence with regard to obesity and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC). Only two of several studies have demonstrated positive association between obesity and NMSC (38, 39). There is speculation the positive association occurs mainly in countries with low UVR exposure, assuming the impact of higher UVR is greater than obesity’s (38), and based on obese individuals spending less time in the sun (40). Adding to the complexity, HFDs, which can increase VAT, increase NMSCs (41, 42). Our mechanistic animal studies will help clarify the relationship between VAT and NMSC risk. Despite the weak epidemiological data, experimental skin carcinogenesis has been used for a century to provide information on the development of epithelial tumors in response to environmental insults -- it relates very well to other squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) models and has contributed to a better understanding of human epithelial cancers in general. Therefore, our findings may inform on the systemic effects of VAT on other epithelial cancers more highly associated with obesity.

Our finding that VAT-derived factors stimulate cell transformation through FGFR-1 provides a novel mechanistic link between visceral adiposity and associated tumor formation. Discovery of such non-invasive biomarkers of VAT-associated tumor formation could enable the identification of individuals that might be at an increased risk of cancer.

Results

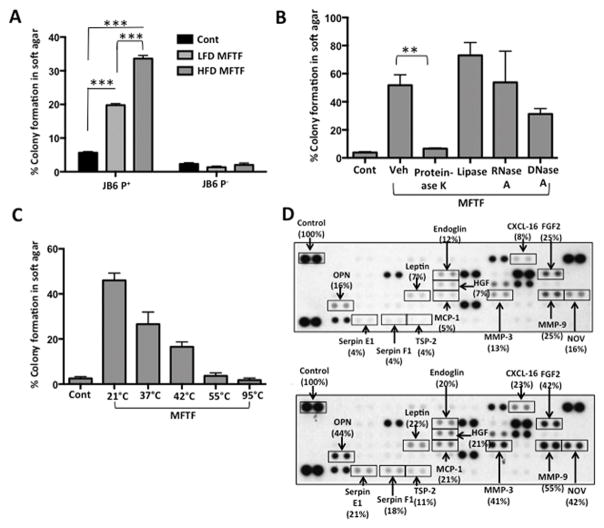

Fat tissue filtrate from high-fat diet-fed mice stimulates JB6 P+ cell transformation

To directly test whether VAT from mice fed different diets could differentially promote cell transformation, animals were kept on either a LFD (10% Kcal from fat) or HFD (60% Kcal from fat) for 4 weeks, after which visceral adipose tissue (VAT) was harvested to generate a filtered VAT-conditioned medium (mouse fat tissue filtrate; MFTF). MFTF (200 μg/ml) significantly stimulated JB6 P+ cell growth, measured as percent colony formation in soft agar; however, HFD MFTF stimulated significantly more transformation compared with LFD MFTF (Figure 1A). HFD MFTF treatment stimulated cell transformation in JB6 P+ but not JB6 P− mouse epithelial cells in culture (Fig. 1A). JB6 P− cells are 1000× less sensitive to tumor promoters compared with JB6 P+ cells and lack the initiation events (activated pro-1 and pro-2) needed for transformation (43). Thus, molecular events that occur in JB6 P+ cells in response to MFTF are candidates for mediating tumor promotion, but not complete carcinogenesis.

Figure 1. Mouse fat tissue filtrate stimulates JB6 P+ cell transformation.

SKH-1 mice (n=5/group) were fed either a HFD or LFD for four weeks. Visceral (parametrial and epididymal) adipose tissue was removed to make a filtered conditioned medium (MFTF). (A) Percentage of clones growing in soft agar (% colony formation) significantly increases in JB6 P+ cells cultured with MFTF compared no treatment (control; Cont). No significant change in the percentage of colony formation in soft agar is observed in JB6 P− cells cultured with MFTF. (B) JB6 P+ colonies growing in soft agar with HFD MFTF is significantly inhibited with proteinase K, but not with lipase, RNase A, or DNase A. (C) JB6 P+ colonies growing in soft agar decrease as MFTF is exposed to increasing temperatures for 30 minutes prior to treating the cells in agar. (D) Protein Profiler angiogenesis array of fat tissue filtrates of LFD-fed mice (top panel) and HFD-fed mice (bottom panel). HFD selectively upregulated protein levels of several key adipokines, hormones, and growth factors in MFTF, vs. those seen in MFTF of LFD-fed mice (boxed proteins). Dot intensity was analyzed by ‘Image J’ software. Data are labeled as the percent of the control (reference) dots located in the upper left hand corner of the arrays. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. of values from triplicate. Statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA (*p<0.05, **p<0.01).

To probe what fraction of VAT possessed transforming activity, HFD MFTFs were treated with either RNase, DNAse, lipase or proteinase (Figure 1B). Incubation with proteinase K inhibited the effect of the HFD MFTF on JB6 P+ growth in soft agar to baseline levels (Figure 1B), while the remaining treatments had no effect. Furthermore, a 30 min exposure of HFD MFTF to heat at 37°C, 42°C, 55°C, or 95°C attenuated colony formation progressively (Figure 1C), consistent with a thermal protein denaturation curve. Together, these data demonstrate that the primary transformational activity of MFTF is found in the protein fraction of the isolate.

To identify the proteins in HFD MFTF associated with transforming activity, angiogenesis and adipokine protein profiler arrays were used to determine differences in the abundance of proteins in MFTF generated either from LFD- or HFD-fed mice. Several proinflammatory adipokines and growth factors were induced in the VAT with 4 weeks of HFD feeding (Figure 1D). These include osteopontin (OPN), Serpin E1, Serpin F1, leptin, thrombospondin-2 (TSP-1), endoglin, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), monocyte-chemoattractant protein-1, CXCL-16, fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2; fibroblast growth factor basic), matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and nephroblastoma overexpressed (NOV). These proteins constitute a candidate list of potential tumor promoting signals released from VAT under conditions of HFD-feeding.

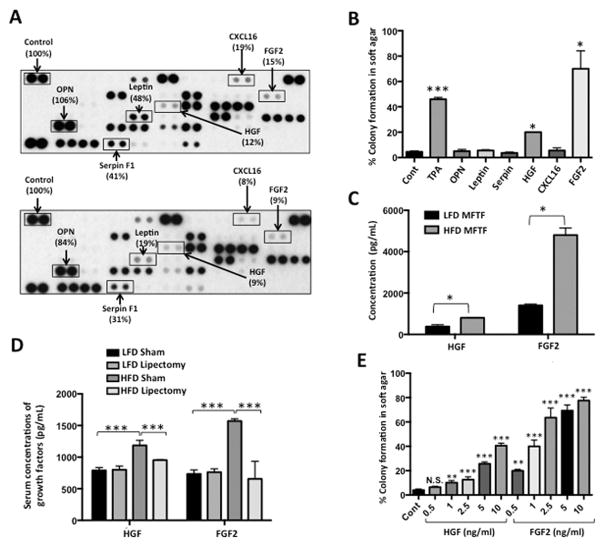

Lipectomy reduces transformation-stimulating serum growth factors in HFD-fed mice

To elucidate the role of VAT on skin tumor promotion in vivo, serum proteins were compared in HFD-fed mice that were either sham-operated or lipectomized (parametrial adipose tissue was removed after two weeks of HFD feeding). Lipectomized mice had significantly less UVB-induced tumors compared with sham-operated mice (24) and had reduced serum levels of several measured pro-inflammatory adipokines and growth factors compared with the sham-operated mice (Figure 2A). These data suggest that the analyzed proteins are of VAT origin and contribute to tumor formation. Adipokines and growth factors were further screened for transforming activity in the JB6 P+ in vitro assay if they were induced with HFD-feeding in VAT (Figure 1D) and they were also reduced in the serum of lipectomized mice compared to sham-operated mice (Figure 2A). The proteins that met both these criteria included OPN, Serpin F1, leptin, HGF, CXCL16 or FGF2. Only JB6 P+ cells cultured with HGF or FGF2 (10 ng/ml) in soft agar showed significant colony formation, compared to baseline (Figure 2B). In addition to protein arrays, to quantify HGF and FGF2 in the MFTF and serum of lipectomized mice, we performed ELISAs. Lipectomy prevented the increase in serum HGF and FGF2 stimulated by HFD-feeding (Figure 2C), suggesting that the increase in circulating HGF and FGF2 from HFD was derived from VAT. HFD significantly increased both HGF and FGF in VAT however, FGF2 protein was 6× higher than HGF protein (4800 pg/ml FGF2 vs. 802 pg/ml HGF). Performing a dose response using recombinant HGF and FGF2 protein starting at 10 ng/ml and titrating down, we found that the concentration of HGF present in VAT was insufficient to transform cells. FGF2 was able to stimulate transformation at concentrations that were present in both LFD and HFD VAT. The dose of FGF2 required to stimulate transformation was not mitogenic in liquid cultures of cells suggesting that FGF2 has a direct effect on transformation that is independent of proliferation (Supplemental Figure 1). These data suggest that FGF2 in MFTF is a primary driver of JB6 P+ transformation.

Figure 2. Lipectomy reduces transformation-stimulating serum growth factors in HFD-fed mice.

(A) SKH-1 mice were fed either a HFD or LFD for two weeks, and half the mice had their parametrial adipose tissue removed or received a sham operation (n=20/group). After 33 weeks of UVB exposure, serum was isolated. Protein Profiler angiogenesis array of pooled sera of HFD-fed sham-operated mice (top panel) and HFD-fed lipectomized mice (bottom panel). HFD-fed mice that had the surgical removal of parametrial adipose tissue showed a decrease in several proinflammatory proteins in the circulation. Boxed proteins were those found to be both reduced with lipectomy and induced in the MFTF with HFD (Figure 1D). Dot intensity was analyzed by ‘ImageJ’ software. Data are labeled as the percent of the control (reference) dots located in the upper left hand corner of the arrays. (B) Proteins found in (A) were tested for their transforming activity in the soft agar assay. HGF (10 ng/ml) and FGF2 (10 ng/ml) significantly stimulated colony formation in soft agar. 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA, 10 ng/ml) was used as a positive control. (C) HGF and FGF2 levels in MFTF from Figure 1A and D were quantified by ELISA. HFD feeding increases the levels of both HGF and FGF2. (D) SKH-1 mice were treated as described in (A). Serum was isolated and analyzed for HGF and FGF2 by ELISA. (E) Dose response of HGF and FGF2 on JB6 P+ cell transformation. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. of values from triplicates and statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA (B–E) followed by a Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons (D) (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

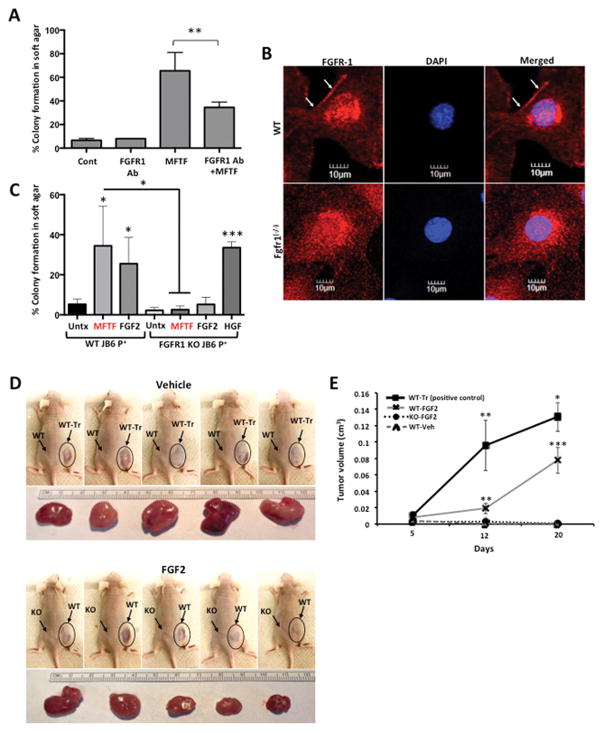

A role for the FGF2-FGFR-1 axis in cell transformation

To determine the respective contribution of FGF2 signaling to the transforming activity of MFTF, JB6 P+ were incubated with an antibody antagonist of the tyrosine kinase FGF2 receptor 1 (FGFR1 Ab). Inhibiting FGFR-1 tyrosine kinase receptor activity significantly attenuated MFTF-stimulated transformation by 48% (Figure 3A). These data suggest that signaling through FGFR1 is required for optimal MFTF-stimulated transformation. Therefore, we used CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to generate JB6 P+ FgfR1 knockout (KO) cells that lack all splice variants of FGFR1, and we hypothesized that this KO would attenuate FGF2-stimulated transformation (Figure 3B, Supplemental Figure 2). Clonal JB6 P+ FgfR1 KO lines were screened for FGFR1 function and loss of both alleles was validated by Sanger sequencing (Supplemental Figure 2). FgfR1 KO cells displayed no difference in proliferation rate compared to wild-type (WT) cells, formed colonies in response to HGF, but failed to form colonies above background levels when cultured with either FGF2 or MFTF (Figure 3C). To determine if FGF2 promotes in vivo tumorigenicity, WT or FgfR1 KO JB6 P+ cells were injected subcutaneously. The following day, mice were dosed with FGF2 or vehicle daily for 7 consecutive days and the formation of subcutaneous (s.c) tumors was evaluated. WT JB6 P+ cells that were transformed in vitro with VAT were injected s.c. as a positive control. Figure 3D demonstrates that WT JB6 P+ cells fail to form tumors in vehicle-injected mice, but proliferate and are tumorigenic in mice injected with FGF2. Histological analysis of the s.c. tumors revealed polygonal neoplastically transformed cells and immunofluorescence revealed positive Ki67 staining (Supplemental Figure 3). The latency of tumor development is longer for WT JB6 P+ cells transformed by FGF2 in vivo compared with WT JB6 P+ cells that were transformed prior to injection (WT-Tr). FGF2 injected in vivo failed to induce tumorigenicity in FgfR1 KO JB6 P+ cells. These data indicate that FGF2 signals specifically through FGFR1 to stimulate cell transformation.

Figure 3. Knockout of FGFR-1 in JB6 P+ cells inhibits the effect of mouse fat tissue filtrate on transformation in vitro.

(A) HFD MFTF-stimulated JB6 P+ cell transformation is partially dependent on FGF2 signaling through the fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 (FGFR-1). Cells were treated with a fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 (FGFR1) neutralizing antibody (Ab) (2 μg/ml) and then treated with MFTF. Growth in soft agar was measured after 14 days. (B) FGFR-1 immunofluorescence (red) in WT JB6 P+ cells and Fgfr1 (−/−) JB6 P+ cells. Specific staining of FGFR-1 is localized to the cell membrane in the WT cells as indicated by white arrows. Membrane FGFR-1 is absent in the KO cells. Images were taken at 40X magnification. Details of generation of the FGFR-1 KO are in Supplemental Figure 2. (C) JB6 P+ cells deficient in FGFR1 fail to grow in soft agar above baseline when cultured with FGF2 and MFTF in soft agar. Percentage of clones growing in soft agar (% colony formation) significantly increases in JB6 P+ cells deficient in FGFR1 cultured with HGF compared no treatment (Untx). (D) Nude mice were subcutaneously inoculated with either WT or FgfR1 KO JB6 P+ cells. A JB6 P+ transformed clone (WT-Tr) was injected as a positive control. The following day, FGF2 (200 mg/kg) or vehicle was injected i.p. once per day for 7 consecutive days. Photos show subcutaneous (s.c.) carcinomas induced by FGF2. (E) Growth rates of s.c. tumors formed by WT or FgfR1(−/−) (KO) JB6 P+ cells injected into Nude mice (n=5) that were either injected with saline (vehicle; Veh) or FGF2. A JB6 P+ transformed clone (WT-Tr) was injected as a positive control. The tumor was monitored everyday and tumor volume was recorded on day 5, 12, and 20. Volume of the tumor was calculated using the formula: V = length x width2 x 0.5. Tumors from FGF2-treated mice inoculated with WT cells are compared to tumors from Veh-treated mice inoculated with WT cells (p<0.01 at 12 days and p<0.001 at 20 days), and tumors from Veh-treated mice inoculated with WT-Tr cells (p<0.01 at 12 days and p<0.05 at 20 days). Data are presented as mean ± S.D. of values from triplicates and statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons (A) (*p<0.05, **p<.001, ***p<.0001).

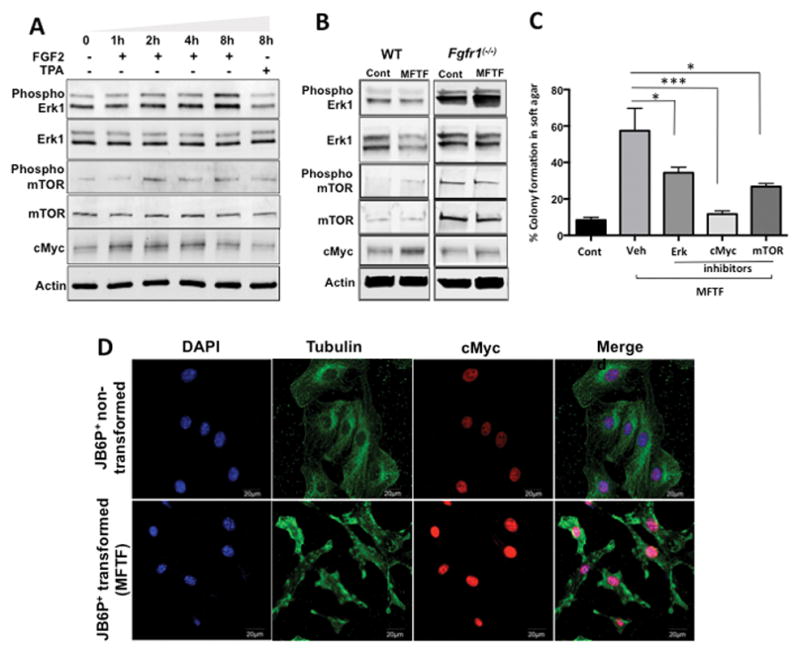

cMYC activity is required for optimal MFTF transforming capacity and cMyc protein is stably overexpressed in transformed cells

To determine the downstream mechanisms of FGF2 signaling responsible for MFTF-induced transformation, cellular lysates of JB6 P+ cells treated with FGF2 (2.5 ng/ml) were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against phospho-ERK, ERK, phospho-mTOR, mTOR, and cMyc. Phospho-ERK was induced at 2, 4 and 8 hours following FGF2 treatment (Figure 4A). Phosphorylation of mTOR was optimally induced 2 hours post-treatment and declined at 4 hours and 8 hours post-treatment, but never returned to baseline (Figure 4A). Lastly, FGF2 stimulated a time-dependent induction of cMyc (Figure 4A). These data demonstrate the activation of ERK, mTOR and cMYC by FGF2. The expression levels of these proteins were examined at 8 h following MFTF stimulation in WT and FGFR-1 KO JB6 P+ cells. FGFR-1 KO cells had higher baseline levels of ERK1 and mTOR whereas baseline levels of cMYC were similar to WT cells. When cells were stimulated with MFTF, there were no changes in protein expression of phospho-ERK, phospho-mTOR, mTOR in both cell lines at 8 h. Unlike WT cells, FGFR-1 KO JB6 P+ cells failed to induce cMYC protein expression in response to MFTF suggesting that cMYC may be a driver of MFTF stimulated transformation (Figure 4B). Inhibiting cMYC, activity in JB6 P+ cells with a pharmacological inhibitor that blocks the cMYC-MAX (myc-associated factor X) interaction significantly attenuated MFTF transforming activity (Figure 4C). Both ERK and mTOR inhibitors also significantly attenuated MFTF transforming activity although to a lesser extent (Figure 4C). To further understand the importance of cMYC in transformation, we compared cMYC protein in non-transformed JB6 P+ cells to MFTF-transformed JB6 P+ cells. MFTF-transformed JB6 P+ cells lines were generated by isolating colonies from soft agar. Transformed cells demonstrated higher cMYC nuclear expression compared to non-transformed cells (Figure 4D). Overall, these data suggest a role for cMYC in VAT-stimulated transformation.

Figure 4. cMYC activity is required for optimal MFTF transforming capacity and cMYC protein is stably overexpressed in transformed cells.

(A) JB6 P+ cells were treated with FGF2 (2.5 ng/ml) for indicated time intervals and protein expression was analyzed by western blot. Phosphorylation of Erk1 and mTOR is upregulated and cMyc increases in a time dependent manner. Actin was used as a loading control. (B) WT JB6 P+ cells and Fgfr1 (−/−) JB6 P+ cells were treated with MFTF (150 μg/ml) for 8 hours. Actin was used as a loading control. At this dose and time of MFTF there was no change in ERK and mTOR activity. cMYC was induced in WT cells but not KO cells. (C) Inhibition of cMyc, mTOR and Erk1 activity by pharmacological inhibitors significantly attenuates MFTF-stimulated JB6 P+ colony formation in agar. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. of values from triplicates and statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA (*p<0.05, **p<.001, ***p<.0001). (D) cMYC immunofluorescence (red) in JB6 P+ cells and JB6 P+ cells transformed with MFTF. MFTF transformed JB6 P+ cells have a higher expression of cMYC compared with non-transformed cells. Transformed JB6 P+ cells are obtained by isolating a colonies from soft agar and growing the cells in liquid culture. These cells were passaged several times for 28 days and maintained a high expression of cMYC. Images were taken at 40X magnification.

Transforming activity of human fat tissue filtrate is associated with FGF2 levels and is dependent on FGFR-1

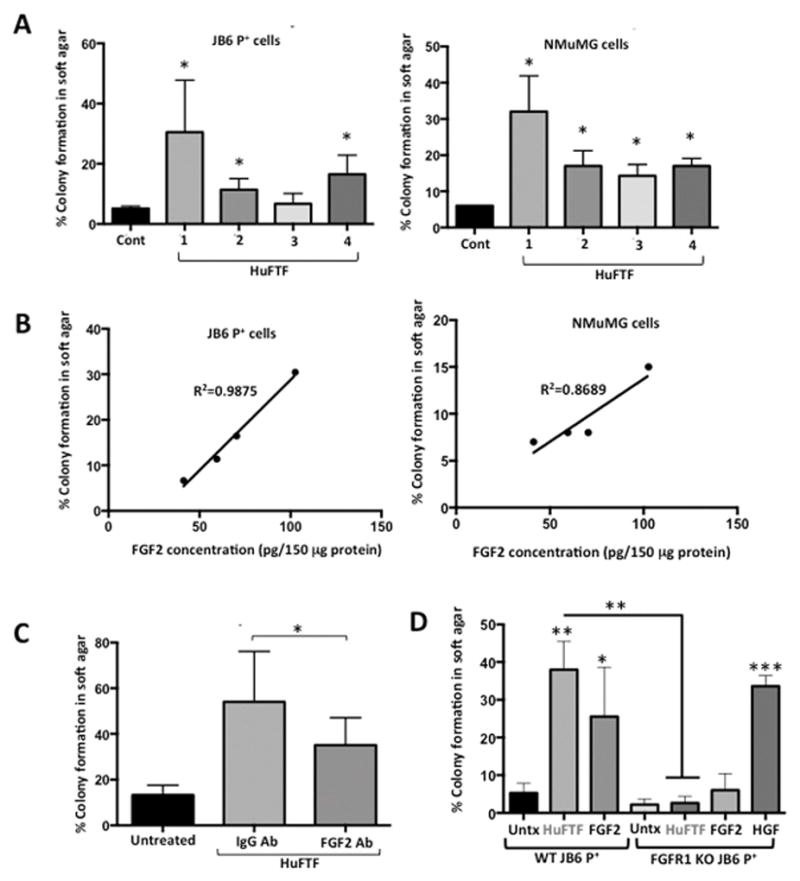

To translate the studies from our mouse VAT model to a human system, human fat tissue filtrates (HuFTF) from VAT of cancer-free, obese human subjects undergoing hysterectomy were generated to determine if human VAT stimulates cell transformation. In addition to using JB6 P+ cells, we also tested transforming activity in NMuMG (mammary epithelial) cells. Like JB6 P+ cells, NMuMG cells are pre-neoplastic and do not exhibit anchorage-independent growth in soft agar. Cells were incubated in agar with 150 μg/ml of HuFTF and scored for colony formation. HuFTF stimulated cell transformation of both JB6 P+ and NMuMG epithelial cells (Figure 5A). There was variability in the transforming activity between donors but the overall relative transforming activity of each sample was similar between JB6 P+ cells and NMuMG cells (Figure 5A). In JB6 P+ cells, transformation stimulated by HuFTFs was strongly associated with FGF2 levels in these filtrates (R2=0.9875; Fig. 5B) based on the soft agar assay and growth factor ELISAs. In NMuMG cells, transformation was only modestly associated with FGF2 in the HuFTFs (R2=0.8689; Fig 5B). We investigated the role of HuFTF-derived FGF2 by immunodepletion of FGF2 from the filtrate (using an antibody against FGF2) and measured the transforming activity. FGF2-immunodepleted HuFTF-transforming activity was significantly reduced, but not completely attenuated, compared with that of HuFTF containing FGF2 (Figure 5C). HuFTF had no additional transforming activity above background levels in JB6 P+ FgfR1 KO cells (Figure 5D). These data demonstrate the translational relevance of our prior mouse experiments and show that HuFTF transforming activity is not only specific to skin epithelial cells but also applicable to mammary epithelial cells. Furthermore, human VAT-derived FGF2 activation of FGFR-1 signaling is a driver of transformation.

Figure 5. Transforming activity of human fat tissue filtrate is associated with FGF2 levels and is dependent on FGFR-1.

Fat tissue filtrates were made from human visceral adipose tissue (HuFTF) from four donors undergoing hysterectomy. (A) Percentage of clones growing in soft agar (% colony formation) significantly increases in JB6 P+ and NMuMG cells cultured with HuFTF from donors 1, 2, and 4 compared no treatment (control; Cont). (B) HuFTF with higher concentrations of FGF2 are more potent at stimulating cell transformation. (C) Immunodepletion of FGF2 in HuFTF significantly attenuates JB6 P+ colony formation in soft agar. (D) JB6 P+ cells deficient in FGFR1 fail to grow in soft agar above baseline when cultured with FGF2 and HuFTF in soft agar. Percentage of clones growing in soft agar (% colony formation) significantly increases in JB6 P+ cells deficient in FGFR1 cultured with HGF compared no treatment (Untx). Data are presented as mean ± S.D. of values from triplicates and statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA (*p<0.05, **p<.001, ***p<.0001).

Discussion

Despite the number of epidemiological studies that demonstrate obesity increases cancer risk, the mechanism is unknown. Obesity-driven cancers are expected to rise over the next 20 years (44) however, not all obese individuals get cancer. Understanding how obesity influences cancer onset and identifying biomarkers of risk will allow us to identify targets for prevention and determine which individuals would benefit most from weight loss. Our previous studies demonstrated that VAT enhances the development of UVB-induced skin tumors in mice (24). Herein, we describe a potential mechanism for visceral adiposity-induced carcinogenesis. We demonstrate that circulating FGF2 from VAT is positively associated with UVB-induced tumor formation in mice, and that VAT-stimulated transformation of epithelial cells is dependent on the presence of the primary receptor for FGF2, FGFR1.

Historically, cancer research has focused on how genetic mutations and/or the amplification or deletion of genes cause cancer. This work on the internal causes of cancer mainly considers cells in isolation. However, in addition to these intrinsic risks, extrinsic risk factors such as HFDs and obesity influence oncogenesis by modifying the hormones, growth factors and inflammatory mediators in the cellular microenvironment (8). Excess adiposity is associated with the elevation of estrogen, insulin, and leptin accelerating the proliferation of both cancerous and non-cancerous cells and stimulating metabolic dysfunction (45–49). In addition to hormones, elevated cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) are key features of adipose tissue dysfunction and may play a role in chronic inflammation and immune dysfunction associated with obesity (50). Proper immune surveillance is critical for preventing skin cancer. Individuals on immune suppressive agents are at a 65–100 fold higher risk for skin squamous cell carcinomas (51). Therefore, the increase in carcinomas we observe in our mouse model of visceral adiposity could be a result of immune dysfunction. It is well established that inflammation is involved in the progression of cancer (52), however the precise role of these and other pro-inflammatory factors and hormones are not well understood. Moreover, in our model, TNF-α was not induced in the VAT with HFD-feeding and IL-6 and leptin, which were induced, did not stimulate epithelial cell transformation (37). Herein, we demonstrate VAT may be a driver of cancer by releasing FGF2, a non-classical adipokine and pro-inflammatory mediator.

FGF2 is a member of the fibroblast growth factor family that comprises various growth factors involving twenty-two different genes that regulate embryonic development and growth, tissue regeneration, and angiogenesis. FGF2, specifically, regulates cell growth, differentiation and angiogenesis in several tissues, and stimulates wound healing in the skin (53). However, the doses of FGF2 in our model of adipose tissue-stimulated transformation have no significant effect on proliferation (Supplemental Figure 1). Previous research shows that FGF2 is overexpressed in several different types of cancer, including pancreatic cancer, endometrial cancer, prostate cancer, melanoma, renal cell carcinoma and lung cancer (54–58). Similar to our study, FGF2 has also been shown to stimulate the transformation of pre-neoplastic cells to a malignant phenotype (59, 60). The gene that encodes a receptor for FGF2, Fgfr1, is amplified in head and neck cancers (61), squamous cell carcinomas of the lung (62), at least 9% of breast cancers (63, 64), colorectal cancer (65) and renal cell carcinoma (66). Additionally, in breast cancer, this amplification is associated with poor prognosis (67) and drives endocrine therapy resistance (68). In skin, Fgfr3 mutations are associated with benign skin tumors in both mice and humans (69). Fgfr2 and Fgfr4 SNPs have no effect on skin cancer risk in caucasians (70). Mutations and SNPs in Fgfr1 have not been studied in the context of NMSC.

Our work hypothesizes that HFD VAT releases FGF2, making this growth factor potentially available to distant sites – an event that is reflected in elevated serum levels of FGF2 that can be potently inhibited by lipectomy (Figure 2). FGF2 has been shown to be synthesized and secreted by adipocytes (71) and play a role in adipogenesis, a program which determines the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into adipocytes. Disruption of the Fgf2 gene activates the adipogenic program in mesenchymal marrow stromal stem cells, suggesting that FGF2 is a negative adipogenic factor (72). Contrary to this, in vitro cell culture studies demonstrate that FGF2 stimulates adipocyte differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells (73), and marrow-derived stem cells (74) and FGF2 can induce de novo adipogenesis when supplied with basement membrane (75). Lee et al. found that the discrepancies in the literature may be explained by the concentration of FGF2 used (76). FGF2 enhanced adipocyte differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells at concentrations lower than 2 ng/ml and suppressed at concentrations higher than 10 ng/ml (76). In contrast to our study, the mice fed a HFD had lower levels of adipose tissue-derived FGF2 compared with mice fed a LFD, differences that may be due to the experimental design. In the Lee et al. study, C57BL/6 mice were fed for 9 weeks and the HFD provided 60% kcal from lard fats whereas in our study, SKH-1 mice were fed for 4 weeks and the HFD provided 60% kcal from corn oil. Any of these variables have the potential influence the kinetics of adipogenesis and therefore, FGF2 levels.

FGF2 is produced in and secreted from tissues other than VAT. Although sera FGF2 is mainly derived from VAT in our animal model, many tissues such as the skin (77), heart (78), liver (79) and lungs (80), as well as subcutaneous adipose tissue (81) can produce FGF2 and could contribute to sera FGF2 in humans. In one study that examined 6 obese men, FGF2 was found in the subcutaneous adipose tissue as well as the VAT (81). In a future study, it would be of interest to compare the impact of gastric bypass surgery (weight loss in all adipose tissue depots) on sera FGF2 compared to the impact of liposuction (subcutaneous adipose tissue removal).

FGF2 is heparin bound in the extracellular matrix acting mainly in a paracrine manner (82) however, studies suggest that FGF2 from tissue can enter the circulation (83–85). Hao et. al. demonstrated that high plasma FGF2 levels correlate with adipose tissue mass in 62 subjects (84) and Kuhn et al. demonstrated that serum FGF2 is significantly elevated in both obesity and morbidly obese subjects (BMI 40+) (83). Although these studies do not provide direct evidence that blood FGF2 is derived from adipose tissue, given the biological function of FGF2 in adipose tissue, it’s association with excess adiposity, and the reduction of serum FGF2 following lipectomy, it is plausible that FGF2 derived from adipose tissue could enter the circulation and be a key play in tumor promotion at distant sites. In obese human males, one study demonstrated that the only cell type in VAT that expresses FGF2 protein is the adipocyte (81). In contrast, we demonstrate that FGF2 protein is expressed in both the adipocyte and the stromal vascular fraction of VAT from HFD-fed mice (Supplemental figure 4). It is also attractive to speculate that FGF2 may not be the only factor released from adipose tissue that stimulates tumor promotion. Antibody neutralization of FGF2 significantly attenuated, but did not completely eliminate the transforming activity of HuFTF that was observed with the FGFR-1 KO cells. This suggests that other secreted FGFs, such as FGF1, or other factors that signal through FGFR-1 may be playing a role. We found that FGF1 stimulates JB6 P+ cell transformation, but other FGFs (FGF18, FGF21) that mainly bind with other FGF receptors (FGFR-2, FGFR-3, and FGFR-4) fail to stimulate transformation (Supplemental figure 4). Determining the relative contribution of FGF-2 and FGF-1 from VAT in vivo and discovering other factors from VAT that could activate FGFR-1 will be the subject of future investigations.

Targeting receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) for cancer therapy faces challenges due to receptor redundancy and the development of RTK resistance (86). Therefore understanding the downstream mechanisms of MFTF-stimulated transformation is critical for determining additional targets for chemoprevention. FGF2 and FGFRs have been shown to activate a cascade of downstream signaling pathways that have an established role in carcinogenesis. These include mitogen activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK), PI3K/AKT/mTOR and cMYC signaling pathways (76, 87, 88). ERK is activated in UVB-induced skin cancer (89). The PI3K/AKT signaling axis stimulates protein synthesis and cell proliferation by activating mTOR at downstream leading to the development of breast cancer (90). cMyc upregulation is associated with several cancer types (including breast and skin) as it plays a critical role in a wide range of functions including cell proliferation, differentiation and progression through different phases of cancer (91–93). We focused our current study on ERK, cMYC, and mTOR pathways because these proteins are involved in obesity-driven cancers (94–97) and dietary restriction has been shown to inhibit mTOR and ERK signaling and MYC protein expression (98–100). FGF2 stimulated the phosphorylation of Erk1 and mTOR and increased cMYC protein expression. In this study, inhibitors of Erk1, cMYC and mTOR all significantly reduced MFTF-stimulated transformation, indicating that these downstream signaling pathways are involved in MFTF-stimulated transformation. Interestingly, cMYC induction was observed in WT JB6 P+ cells, but not FGFR-1 KO JB6 P+ cells, indicating that cMYC activity may be critical for malignant transformation. cMYC was also stably overexpressed in MFTF transformed cells. Therefore, FGF2 in VAT may be interacting through FGFR-1 on epithelial cells to induce downstream signaling of cMYC to stimulate transformation. While cMYC has traditionally been a difficult drug target to modulate, bromodomain inhibitors have been shown to epigenetically regulate cMYC expression in cancer (101). Exploring how these drugs may prevent adiposity-associated tumor formation and determining a cMYC signature in adiposity-associated tumors provides an attractive area for future study.

In summary, we demonstrated that VAT from HFD-fed mice and HuFTF transforms non-tumorigenic epithelial cells. The differences in VAT activity between LFD- and HFD-fed mice and human donors were associated with FGF2 levels. Moreover, human and mouse VAT failed to stimulate transformation in cells deficient in FGFR-1 (FGF2 receptor). We also demonstrated that circulating levels of FGF2 were associated with non-melanoma tumor formation in vivo. These data therefore suggest FGF2 stimulation of FGFR-1 as a previously unappreciated link between VAT and cell transformation. This key finding begins to inform how HFDs and/or visceral adiposity elevate cancer risk, previously suggested only via epidemiological studies (14, 15). To determine a causal relationship, future studies will examine if FGF2 administration will prevent lipectomy from attenuating HFD-stimulated tumor promotion in our UVB-induced skin cancer model. Strategies designed to deplete VAT stores of FGF2 in abdominally obese individuals or inhibit FGFR-1 signaling may be important cancer prevention strategies as well as adjuvant therapies for improving outcomes following skin or breast cancer diagnosis.

Methods

Cell culture and reagents

JB6 P+ and JB6 P− cells (mouse skin epithelial cells) were obtained from the American type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and were free from mycoplasma contamination. Cells were grown in MEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% FBS and antibiotics. NMuMG cells were received as a kind gift from Dr. Richard Schwartz (MSU) and were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. Pharmacological inhibitors against cMyc, mTOR and Erk1 were purchased from EMD Millipore, USA. Tivantinib was purchased from APExBIO (Houston, TX). FGFR-1 Ab for immunofluorescence was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). FGF2 Ab was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). Antibodies: p-mTOR (Cell Signaling Technology #2974), mTOR (Cell Signaling Technology #2983), c-Myc (Cell Signaling Technology #5605), p-Erk1 (Cell Signaling Technology #4370), Erk1 (Cell Signaling Technology #9102), Actin (Sigma #A5060), HGF (Abcam #ab-83760), FGF2 (Santa Cruz #sc-365106), FGFR1 (R&D Systems #MAB765), Anti-Rabbit 2nd Ab (Li-Cor #926–32213), Anti-Mouse 2nd Ab (Li-Cor #926–32212).

Animal Models

Healthy inbred female SKH1 mice (6/8 weeks) were kept at environmentally controlled conditions in polypropylene cages, allowed free drinking water and basal diet ad libitum. All animal protocols were approved by the IACUC at MSU. Animals of equal age, size and body weight were chosen randomly for each experimental group. Animals were kept either on LFD containing 10 kcal of fat (D11012202) or HFD containing 60 kcal of fat (60% kcal form corn oil D11012204, Research Diets, Inc. NJ). At the end of experimental period mice were humanely sacrificed using carbon dioxide and blood and adipose tissue samples were collected. For the lipectomy study, SKH-1 mice (8 weeks, n=20) were kept on either a LFD or HFD for 2 weeks prior to lipectomy. Two weeks after lipectomy, animals were exposed to UVB (15 mJ/cm2) twice per week for 33 weeks. Tissues and serum were collected and tumors were analyzed as previously described (24). For the in vivo tumorigenicity/xenograft study, male nude mice (8 weeks, n=5) were subcutaneously inoculated with either WT or FgfR1 KO JB6 P+ cells (1.8×106/0.2ml/mouse) in the right and left flanks (one injection per side). The following day, FGF2 (200 μg/kg) or vehicle was injected i.p. once per day for the next 7 days. Tumors were measured with calipers on days 5, 12 and 20 and mice were sacrificed 21 days post injection. Tumor volume was assessed by investigators blinded to the experimental groups.

Anchorage independent colony formation assay in soft agar

Colony formation assays were performed in 12-well plates with either 1,000 JB6 P+ cells/ well or 1,500 NMuMG cells/ well in 0.6 ml of 0.3% soft agar with or without fat tissue filtrate (FTF), growth factors and inhibitors on top of a 0.75 ml base layer of 0.5% agar. Cells in plate were allowed to settle for 30 minutes and cultured for up to 2 weeks (JB6 P+ cells) or 5 weeks (NMuMG cells). At the end of the incubation period, cells were stained with 0.01% crystal violet, and colonies were counted in ‘Cytation 3 cell imaging multi-mode reader’ (BioTek Instruments, Inc., USA).

Preparation of fat tissue filtrates

100 mg of adipose tissue was gently homogenized in an equal volume of serum free MEM on ice for 30 sec using Tissue Ruptor (Qiagen Hilden, Germany) on medium speed. Homogenates were filtered through hanging 15-mm wide 0.4 μm filter insert (Millicell, cat# MCHT06H48) in to a six well plate previously filled with 400 μl serum free MEM and incubated on a rocker at RT for 1 hr to allow small molecules and proteins to diffuse into the medium while removing lipids and macromolecules. After incubation filtrates were centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 5 min and the supernatant was collected and filtered through 0.4 μm syringe filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and protein concentrations were quantified using BCA assay. 200 μg/ml concentration of mouse fat tissue filtrates (MFTF) and 150 μg/ml concentration of human fat tissue filtrates (HuFTF) were used for respective experiments.

Treatment of cells in soft agar

For analysis of heat induced inactivation of MFTF, samples were pre-incubated at 4°C, 37°C, 55°C and 95°C, respectively, for 30 min and then added to the top layers of agar containing JB6 P+ cells. For assessment of protein- and lipid- specific activity of MFTF, samples were pre-incubated with proteinase K (1μg/ml) (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) or lipase (5 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) at 37°C for 30 min before using the samples for soft agar assay. Activity of DNA and RNA in the MFTF were analyzed by adding either DNase (1μg/ml) (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) or RNase (1μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis) into the top layers of soft agar with cells and MFTF. Pharmacological inhibitors against cMyc, mTOR, Erk1, FGFR-1 and c-MET (tivantinib) were added directly into the top layers of soft agar containing cells and MFTF or HuFTF. For neutralization of FGFR1 activity, cells were pre-incubated with monoclonal FGFR1 neutralizing antibody (2–3 μg/ ml) in 37°C for 1h before platting them in soft agar for further experiments.

Isolation of adipocytes and the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) from mouse adipose tissue

Adipocytes and non-adipocyte cells (SVF) from mouse fat were isolated using the protocol mentioned earlier with some minor modifications (102). Fresh adipose tissue was obtained from mice, minced into small pieces and immediately placed in fresh physiological saline solution (PSS; 0.9% NaCl). Fats were digested in 1ml of 1mg/ml collagenase Type1 (Worthington Biochemical Co. Lakewood, NJ) in PSS and incubated at 37°C for 30 min followed by centrifugation for 5 min at 300 rpm in RT. Using a syringe with a 23G needle SVF rich fraction was removed without disturbing the upper adipocyte layer. SVF and adipocyte rich fractions were placed separately in new tube. SVF and adipocytes were washed twice with cold PSS and cell pellets were recovered by centrifuging for 10 min at 300 rpm.

Protein Profiler Arrays

Measurement of mouse adipokines and growth factors from fat tissue filtrates was performed using the Mouse Angiogenesis Antibody Array kit (R&D Systems Cat# ARY015). By comparing the signal intensities, relative expression levels of cytokines were determined and quantified by densitometry using ‘ImageJ’ software (NIH).

Western Blot

2.8X105 cells were plated in 60-mm culture dishes and allowed to grow for 48 hr before treatment. The cells were treated with either MFTF (at 300 μg/ml dose) or FGF2- 2.5 ng/ml for indicated period of time. After treatment, cells were harvested, washed, and lysed in RIPA buffer pH 7.4, supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Proteins were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with either 5% nonfat milk solution or 4% BSA and then incubated with the appropriate primary antibody for overnight at 4°C, followed by 1 hr incubation with fluorochrome tagged secondary antibody. Bands were visualized by LI-COR Odyssey classic image scanner (Lincoln, Nebraska).

Immunodepletion assay

2 μg affinity purified monoclonal FGF2 antibody was added to 100–150 μl of fat tissue filtrates and incubated for 16 hr in 4°C under gentle agitation. 50 μl protein G-coupled Agarose beads were added in to the solution and the slurry was gently mixed followed by further incubation for 5 hr in 4°C under gentle agitation. Supernatants were collected after centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 30 sec and used for further experiments.

Quantification of HGF and FGF2

Concentrations of HGF and FGF2 were measured in both mouse and human adipose tissue and in mouse sera. HGF and FGF2 were quantified by ELISA according to the manufacturer protocol using ‘R&D Systems Quantikine ELISA kit’ (Cat# DHG00 and Cat# DFB50).

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded fat tissue sections from mice were de-paraffinised and incubated with antigen retrieval buffer for 1 min at 95°C. Sections were blocked in 4% BSA for 1 hr at RT and then treated either with control mouse IgG or with primary mouse monoclonal anti-FGF2 or anti-HGF antibody (1:100) overnight at 4°C, followed by secondary anti-mouse antibody labeled with HRP. After brief washing, slides were stained for 30 sec using 3,3-diaminobenzidine as substrate. Nuclei were stained with hematoxylin (Harris) for 30 sec. Images were acquired with a Nikon digital camera attached on an Olympus microscope at 400X magnification.

Generation of FGFR1 knockout cells

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing was used to generate Fgfr1 homozygous knockout JB6 P+ cells (Fig. S2). Three gRNAs were selected to target exons 5, 7 and 10 of the mouse Fgfr1 gene (ENSMUSG00000031565). Oligo duplexes for gRNA templates were annealed and cloned into pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (PX458), a gift from Feng Zhang (Addgene plasmid # 48138), as previously described (103). JB6 P+ were electroporated (1,300V, 30ms, single pulse) with 3 gRNA plasmids using a Neonâ Nucleofector (ThermoFisher Scientific). 48 hr later cells were trypsinized and resuspended in dPBS + 0.1% BSA for cell sorting. Single cells that were GFP (+) and propidium iodide (−), were sorted and isolated in a 96-well plate, using a BD Influx sorter (BD Biosciences-US). Clonal lines were expanded and screened by PCR and functional soft agar assay to identify desired genotypes and phenotypes. Clonal line #4, used for experiments in this study, was sequenced at all 3 exons to determined exact genomic modifications (Fig. S2).

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 15 min, blocked with 4% BSA for 1 hour and permeabilized with 0.2% PBS-T for 10 min. Cells were was incubated overnight with primary FGFR-1 antibody (1:400 dilution) at 4°C followed by incubation in secondary Anti-rabbit (1:200 dilution) for 1 hour at room temperature. Photographs were taken at 40X magnification in Olympus Fluoview 1000.

Animal study approval

All mice used in this study received humane care that adheres to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication, 1996 edition), and the protocol was approved by the IACUC and Animal Care Program of Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI.

Study approval for human samples

The Rutgers-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School Institutional Review Board approved the protocol “Determining the Impact of Human Fat on Cancer Development” on October 16th, 2015. Informed consent was obtained from candidates before undergoing gynecologic surgery. Intra-abdominal visceral (omental and parametrial) adipose tissue was obtained, and samples were de-identified to investigators at Michigan State University.

Statistics

For in vitro experiments, 3 biological and/or 3 technical replicates were used to ensure adequate power to detect a significant change in growth in soft agar. All animal experiments were performed using at least 5 mice. The number of mice selected per group for in vivo studies is anchored in statistical power analysis, whereby historical data from key experimental endpoints are utilized to gauge anticipated mean values and biological variation within a particular experimental group. The experimental endpoints used included tumor number (for UV experiments) and tumor volume (for xenograft studies). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Two-way ANOVA was used to compare among groups followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. For all statistical tests, 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 level of confidence was accepted for statistical significance.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support for work

National Institutes of Health grant R00 CA177868, Michigan State University start-up funds, Breast Cancer Research Program, under Award No. W81XWH-15-1-0453 and the 2016 AACR-Incyte Corporation NextGen Grant for Transformative Cancer Research, Grant Number 16-20-46-LUNT.

We acknowledge the MSU Investigative HistoPathology Laboratory, Amy S. Porter, HT(ASCP) QIHC and Kathleen A. Joseph, HT (ASCP) QIHC. We would also like to thank Dr. Karen Liby (MSU) for her consultation and providing antibodies, Dr. Richard Neubig (MSU) and Dr. Matthew Bernard (MSU) for his consultation and assistance with experimental design and Dr. Dalen Agnew (MSU) for his consultation on tumor pathology. J.J.B is funded by National Institutes of Health grant R00 CA177868, Michigan State University start-up funds. S.Y.L is funded by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, through the Breast Cancer Research Program, under Award No. W81XWH-15-1-0453 and the 2016 AACR-Incyte Corporation NextGen Grant for Transformative Cancer Research, Grant Number 16-20-46-LUNT.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

D.C. designed research studies, conducted experiments, acquired and analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. V.B. conducted experiments, B.B. conducted experiments. T.K. provided human adipose tissue, designed experiments, reviewed manuscript. H.H. provided human adipose tissue, designed experiments, reviewed manuscript. D.G. provided human adipose tissue, designed experiments, reviewed manuscript. E.Y.D. performed experiments, acquired data and analyzed data for CRISPR studies. S.Y.L. designed experiments, reviewed manuscript. J.J.B. oversaw research, designed research studies, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc)

References

- 1.Renehan AG, Zwahlen M, Egger M. Adiposity and cancer risk: new mechanistic insights from epidemiology. Nature reviews Cancer. 2015;15(8):484–98. doi: 10.1038/nrc3967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nunez NP, Perkins SN, Smith NC, Berrigan D, Berendes DM, Varticovski L, et al. Obesity accelerates mouse mammary tumor growth in the absence of ovarian hormones. Nutrition and cancer. 2008;60(4):534–41. doi: 10.1080/01635580801966195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. Jama. 2010;303(3):242–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill AL, Rand DG, Nowak MA, Christakis NA. Infectious disease modeling of social contagion in networks. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6(11):e1000968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ligibel JA, Alfano CM, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Burger RA, Chlebowski RT, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement on obesity and cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(31):3568–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, Walsh K. Obesity, adiponectin and vascular inflammatory disease. Current opinion in lipidology. 2003;14(6):561–6. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200312000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg KK, Madsen HO, Garred P, Wiseth R, Gunnes S, Videm V. The additive contribution from inflammatory genetic markers on the severity of cardiovascular disease. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 2009;69(1):36–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Font-Burgada J, Sun B, Karin M. Obesity and Cancer: The Oil that Feeds the Flame. Cell Metab. 2016;23(1):48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Obesity and the role of adipose tissue in inflammation and metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):461S–5S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.461S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samaras K, Botelho NK, Chisholm DJ, Lord RV. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue gene expression of serum adipokines that predict type 2 diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(5):884–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fried SK, Bunkin DA, Greenberg AS. Omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues of obese subjects release interleukin-6: depot difference and regulation by glucocorticoid. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1998;83(3):847–50. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nature reviews Immunology. 2011;11(2):85–97. doi: 10.1038/nri2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iyengar NM, Zhou XK, Gucalp A, Morris PG, Howe LR, Giri DD, et al. Systemic Correlates of White Adipose Tissue Inflammation in Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(9):2283–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy RA, Bureyko TF, Miljkovic I, Cauley JA, Satterfield S, Hue TF, et al. Association of total adiposity and computed tomographic measures of regional adiposity with incident cancer risk: a prospective population-based study of older adults. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39(6):687–92. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2013-0360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore LL, Bradlee ML, Singer MR, Splansky GL, Proctor MH, Ellison RC, et al. BMI and waist circumference as predictors of lifetime colon cancer risk in Framingham Study adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(4):559–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibrahim MM. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: structural and functional differences. Obesity reviews: an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2010;11(1):11–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vague J. The degree of masculine differentiation of obesities: a factor determining predisposition to diabetes, atherosclerosis, gout, and uric calculous disease. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1956;4(1):20–34. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/4.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connolly BS, Barnett C, Vogt KN, Li T, Stone J, Boyd NF. A meta-analysis of published literature on waist-to-hip ratio and risk of breast cancer. Nutrition and cancer. 2002;44(2):127–38. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC4402_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaudet MM, Carter BD, Patel AV, Teras LR, Jacobs EJ, Gapstur SM. Waist circumference, body mass index, and postmenopausal breast cancer incidence in the Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort. Cancer causes & control: CCC. 2014;25(6):737–45. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hajian-Tilaki KO, Gholizadehpasha AR, Bozorgzadeh S, Hajian-Tilaki E. Body mass index and waist circumference are predictor biomarkers of breast cancer risk in Iranian women. Medical oncology. 2011;28(4):1296–301. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Z, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Rosner B, et al. Waist circumference, waist:hip ratio, and risk of breast cancer in the Nurses’ Health Study. American journal of epidemiology. 1999;150(12):1316–24. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schapira DV, Clark RA, Wolff PA, Jarrett AR, Kumar NB, Aziz NM. Visceral obesity and breast cancer risk. Cancer. 1994;74(2):632–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940715)74:2<632::aid-cncr2820740215>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huffman DM, Augenlicht LH, Zhang X, Lofrese JJ, Atzmon G, Chamberland JP, et al. Abdominal obesity, independent from caloric intake, accounts for the development of intestinal tumors in Apc(1638N/+) female mice. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013;6(3):177–87. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu YP, Lou YR, Bernard JJ, Peng QY, Li T, Lin Y, et al. Surgical removal of the parametrial fat pads stimulates apoptosis and inhibits UVB-induced carcinogenesis in mice fed a high-fat diet. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(23):9065–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205810109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang D, Li J, Gao J, Huang C. c-Jun/AP-1 pathway-mediated cyclin D1 expression participates in low dose arsenite-induced transformation in mouse epidermal JB6 Cl41 cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;235(1):18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu FJ, Tseng TH, Lee WJ, Yen CC, Yin YF, Liao CW, et al. Promoting neoplastic transformation of humic acid in mouse epidermal JB6 Cl41 cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2006;162(3):249–58. [Google Scholar]

- 27.He Z, Cho YY, Liu G, Ma WY, Bode AM, Dong Z. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase regulation of JB6 Cl41 cell transformation promoted by epidermal growth factor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(29):26435–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303859200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amstad PA, Liu H, Ichimiya M, Chang S, Berezesky IK, Trump BF. bcl-2 enhancement of malignant transformation in mouse epidermal JB6 cells. Mol Carcinog. 1997;20(2):231–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199710)20:2<231::aid-mc10>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong Z, Lavrovsky V, Colburn NH. Transformation reversion induced in JB6 RT101 cells by AP-1 inhibitors. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16(4):749–56. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.4.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong Z, Birrer MJ, Watts RG, Matrisian LM, Colburn NH. Blocking of tumor promoter-induced AP-1 activity inhibits induced transformation in JB6 mouse epidermal cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(2):609–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith JS, Jr, Wey HE, Leikauf GD, Baxter CS. JB6 murine epidermal cell lines sensitive and resistant to 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced transformation exhibit differential arachidonic acid metabolism in response to TPA and the calcium ionophore A23187. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13(2):189–92. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ben-Ari ET, Bernstein LR, Colburn NH. Differential c-jun expression in response to tumor promoters in JB6 cells sensitive or resistant to neoplastic transformation. Mol Carcinog. 1992;5(1):62–74. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940050111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain AK, Shimoi K, Nakamura Y, Sano M, Tomita I. Effect of tea on 12-O tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13 acetate (TPA) induced promotion of transformation in JB6 mouse epidermal cells. Indian J Cancer. 1989;26(2):92–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakamura Y, Gindhart TD, Winterstein D, Tomita I, Seed JL, Colburn NH. Early superoxide dismutase-sensitive event promotes neoplastic transformation in mouse epidermal JB6 cells. Carcinogenesis. 1988;9(2):203–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/9.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith BM, Gindhart TD, Colburn NH. Extracellular calcium requirement for promotion of transformation in JB6 cells. Cancer research. 1986;46(2):701–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Srinivas L, Colburn NH. Preferential oxidation of cell surface sialic acid by periodate leads to promotion of transformation in JB6 cells. Carcinogenesis. 1984;5(4):515–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/5.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernard JJ, Lou YR, Peng QY, Li T, Vakil PR, Ding N, et al. Parametrial fat tissue from high fat diet-treated SKH-1 mice stimulates transformation of mouse epidermal JB6 cells. Journal of carcinogenesis & mutagenesis. 2014;5(183):2157–518. doi: 10.4172/2157-2518.1000183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Courneya KS, Katzmarzyk PT, Bacon E. Physical activity and obesity in Canadian cancer survivors: population-based estimates from the 2005 Canadian Community Health Survey. Cancer. 2008;112(11):2475–82. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahl WJ, Glore S, Garrison P, Oakleaf K, Johnson SD. Basal cell carcinoma and lifestyle characteristics. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34(6):398–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb04440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pothiawala S, Qureshi AA, Li Y, Han J. Obesity and the incidence of skin cancer in US Caucasians. Cancer causes & control: CCC. 2012;23(5):717–26. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9941-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ibiebele TI, van der Pols JC, Hughes MC, Marks GC, Green AC. Dietary fat intake and risk of skin cancer: a prospective study in Australian adults. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2009;125(7):1678–84. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ibiebele TI, van der Pols JC, Hughes MC, Marks GC, Williams GM, Green AC. Dietary pattern in association with squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: a prospective study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(5):1401–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colburn NH, Wendel EJ, Abruzzo G. Dissociation of mitogenesis and late-stage promotion of tumor cell phenotype by phorbol esters: mitogen-resistant variants are sensitive to promotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1981;78(11):6912–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arnold M, Pandeya N, Byrnes G, Renehan AG, Stevens GA, Ezzati M, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to high body-mass index in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(1):36–46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71123-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hursting SD, Lavigne JA, Berrigan D, Perkins SN, Barrett JC. Calorie restriction, aging, and cancer prevention: mechanisms of action and applicability to humans. Annu Rev Med. 2003;54:131–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.54.101601.152156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yakar S, Nunez NP, Pennisi P, Brodt P, Sun H, Fallavollita L, et al. Increased tumor growth in mice with diet-induced obesity: impact of ovarian hormones. Endocrinology. 2006;147(12):5826–34. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI, Trudeau ME, Koo J, Madarnas Y, et al. Fasting insulin and outcome in early-stage breast cancer: results of a prospective cohort study. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20(1):42–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miyoshi Y, Funahashi T, Kihara S, Taguchi T, Tamaki Y, Matsuzawa Y, et al. Association of serum adiponectin levels with breast cancer risk. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(15):5699–704. Aba, insulin resistance, and endometrial cancer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dutta D, Ghosh S, Pandit K, Mukhopadhyay P, Chowdhury S. Leptin and cancer: Pathogenesis and modulation. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(Suppl 3):S596–600. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.105577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1821–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chockalingam R, Downing C, Tyring SK. Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinomas in Organ Transplant Recipients. J Clin Med. 2015;4(6):1229–39. doi: 10.3390/jcm4061229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S, Sandur SK, Pandey MK, Sethi G. Inflammation and cancer: how hot is the link? Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72(11):1605–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ortega S, Ittmann M, Tsang SH, Ehrlich M, Basilico C. Neuronal defects and delayed wound healing in mice lacking fibroblast growth factor 2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(10):5672–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu M, Hu Y, He J, Li B. Prognostic Value of Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF) in Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. PloS one. 2016;11(1):e0147374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cronauer MV, Hittmair A, Eder IE, Hobisch A, Culig Z, Ramoner R, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor levels in cancer cells and in sera of patients suffering from proliferative disorders of the prostate. Prostate. 1997;31(4):223–33. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19970601)31:4<223::aid-pros3>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakamoto T, Chang CS, Li AK, Chodak GW. Basic fibroblast growth factor in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer research. 1992;52(3):571–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marshall FF. Impact of serum basic fibroblast growth factor on prognosis in human renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2002;168(2):877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kornmann M, Beger HG, Korc M. Role of fibroblast growth factors and their receptors in pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1998;17(2):169–75. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199808000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weber TJ, Shankaran H, Wiley HS, Opresko LK, Chrisler WB, Quesenberry RD. Basic fibroblast growth factor regulates persistent ERK oscillations in premalignant but not malignant JB6 cells. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2010;130(5):1444–56. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Quarto N, Talarico D, Sommer A, Florkiewicz R, Basilico C, Rifkin DB. Transformation by basic fibroblast growth factor requires high levels of expression: comparison with transformation by hst/K-fgf. Oncogene Res. 1989;5(2):101–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Freier K, Schwaenen C, Sticht C, Flechtenmacher C, Muhling J, Hofele C, et al. Recurrent FGFR1 amplification and high FGFR1 protein expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) Oral Oncol. 2007;43(1):60–6. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weiss J, Sos ML, Seidel D, Peifer M, Zander T, Heuckmann JM, et al. Frequent and focal FGFR1 amplification associates with therapeutically tractable FGFR1 dependency in squamous cell lung cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(62):62ra93. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elbauomy Elsheikh S, Green AR, Lambros MB, Turner NC, Grainge MJ, Powe D, et al. FGFR1 amplification in breast carcinomas: a chromogenic in situ hybridisation analysis. Breast cancer research: BCR. 2007;9(2):R23. doi: 10.1186/bcr1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ahmad I, Iwata T, Leung HY. Mechanisms of FGFR-mediated carcinogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823(4):850–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sato T, Oshima T, Yoshihara K, Yamamoto N, Yamada R, Nagano Y, et al. Overexpression of the fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 gene correlates with liver metastasis in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2009;21(1):211–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tsimafeyeu I, Demidov L, Stepanova E, Wynn N, Ta H. Overexpression of fibroblast growth factor receptors FGFR1 and FGFR2 in renal cell carcinoma. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011;45(3):190–5. doi: 10.3109/00365599.2011.552436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jang M, Kim E, Choi Y, Lee H, Kim Y, Kim J, et al. FGFR1 is amplified during the progression of in situ to invasive breast carcinoma. Breast cancer research: BCR. 2012;14(4):R115. doi: 10.1186/bcr3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Turner N, Pearson A, Sharpe R, Lambros M, Geyer F, Lopez-Garcia MA, et al. FGFR1 amplification drives endocrine therapy resistance and is a therapeutic target in breast cancer. Cancer research. 2010;70(5):2085–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Logie A, Dunois-Larde C, Rosty C, Levrel O, Blanche M, Ribeiro A, et al. Activating mutations of the tyrosine kinase receptor FGFR3 are associated with benign skin tumors in mice and humans. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(9):1153–60. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nan H, Qureshi AA, Hunter DJ, Han J. Genetic variants in FGFR2 and FGFR4 genes and skin cancer risk in the Nurses’ Health Study. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:172. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mydlo JH, Kral JG, Macchia RJ. Preliminary results comparing the recovery of basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) in adipose tissue and benign and malignant renal tissue. J Urol. 1998;159(6):2159–63. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63298-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xiao L, Sobue T, Esliger A, Kronenberg MS, Coffin JD, Doetschman T, et al. Disruption of the Fgf2 gene activates the adipogenic and suppresses the osteogenic program in mesenchymal marrow stromal stem cells. Bone. 2010;47(2):360–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kakudo N, Shimotsuma A, Kusumoto K. Fibroblast growth factor-2 stimulates adipogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;359(2):239–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neubauer M, Fischbach C, Bauer-Kreisel P, Lieb E, Hacker M, Tessmar J, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor enhances PPARgamma ligand-induced adipogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells. FEBS Lett. 2004;577(1–2):277–83. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kawaguchi N, Toriyama K, Nicodemou-Lena E, Inou K, Torii S, Kitagawa Y. De novo adipogenesis in mice at the site of injection of basement membrane and basic fibroblast growth factor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(3):1062–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim S, Ahn C, Bong N, Choe S, Lee DK. Biphasic effects of FGF2 on adipogenesis. PloS one. 2015;10(3):e0120073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grazul-Bilska AT, Luthra G, Reynolds LP, Bilski JJ, Johnson ML, Adbullah SA, et al. Effects of basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) on proliferation of human skin fibroblasts in type II diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2002;110(4):176–81. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Itoh N, Ohta H. Pathophysiological roles of FGF signaling in the heart. Front Physiol. 2013;4:247. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pan RL, Xiang LX, Wang P, Liu XY, Nie L, Huang W, et al. Low-molecular-weight fibroblast growth factor 2 attenuates hepatic fibrosis by epigenetic down-regulation of Delta-like1. Hepatology. 2015;61(5):1708–20. doi: 10.1002/hep.27649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Matsui R, Brody JS, Yu Q. FGF-2 induces surfactant protein gene expression in foetal rat lung epithelial cells through a MAPK-independent pathway. Cell Signal. 1999;11(3):221–8. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(98)00070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gabrielsson BG, Johansson JM, Jennische E, Jernas M, Itoh Y, Peltonen M, et al. Depot-specific expression of fibroblast growth factors in human adipose tissue. Obes Res. 2002;10(7):608–16. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Steringer JP, Muller HM, Nickel W. Unconventional secretion of fibroblast growth factor 2--a novel type of protein translocation across membranes? J Mol Biol. 2015;427(6 Pt A):1202–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kuhn MC, Willenberg HS, Schott M, Papewalis C, Stumpf U, Flohe S, et al. Adipocyte-secreted factors increase osteoblast proliferation and the OPG/RANKL ratio to influence osteoclast formation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;349(2):180–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hao RH, Guo Y, Dong SS, Weng GZ, Yan H, Zhu DL, et al. Associations of Plasma FGF2 Levels and Polymorphisms in the FGF2 Gene with Obesity Phenotypes in Han Chinese Population. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19868. doi: 10.1038/srep19868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Larsson A, Skoldenberg E, Ericson H. Serum and plasma levels of FGF-2 and VEGF in healthy blood donors. Angiogenesis. 2002;5(1–2):107–10. doi: 10.1023/a:1021588227705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Regad T. Targeting RTK Signaling Pathways in Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2015;7(3):1758–84. doi: 10.3390/cancers7030860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lepique AP, Moraes MS, Rocha KM, Eichler CB, Hajj GN, Schwindt TT, et al. c-Myc protein is stabilized by fibroblast growth factor 2 and destabilized by ACTH to control cell cycle in mouse Y1 adrenocortical cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;33(3):623–38. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lau MT, So WK, Leung PC. Fibroblast growth factor 2 induces E-cadherin down-regulation via PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MAPK/ERK signaling in ovarian cancer cells. PloS one. 2013;8(3):e59083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bowden GT. Prevention of non-melanoma skin cancer by targeting ultraviolet-B-light signalling. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(1):23–35. doi: 10.1038/nrc1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Baselga J. Targeting the phosphoinositide-3 (PI3) kinase pathway in breast cancer. Oncologist. 2011;16(Suppl 1):12–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-S1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sarveswaran S, Chakraborty D, Chitale D, Sears R, Ghosh J. Inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase selectively triggers disruption of c-Myc signaling in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(8):4994–5006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.599035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang X, Farrell AS, Daniel CJ, Arnold H, Scanlan C, Laraway BJ, et al. Mechanistic insight into Myc stabilization in breast cancer involving aberrant Axin1 expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(8):2790–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100764108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Adhikary S, Eilers M. Transcriptional regulation and transformation by Myc proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(8):635–45. doi: 10.1038/nrm1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li HJ, Che XM, Zhao W, He SC, Zhang ZL, Chen R, et al. Diet-induced obesity promotes murine gastric cancer growth through a nampt/sirt1/c-myc positive feedback loop. Oncol Rep. 2013;30(5):2153–60. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Malley CO, Pidgeon GP. The mTOR pathway in obesity driven gastrointestinal cancers: Potential targets and clinical trials. BBA Clin. 2016;5:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vucenik I, Stains JP. Obesity and cancer risk: evidence, mechanisms, and recommendations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1271:37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Binai NA, Damert A, Carra G, Steckelbroeck S, Lower J, Lower R, et al. Expression of estrogen receptor alpha increases leptin-induced STAT3 activity in breast cancer cells. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2010;127(1):55–66. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu Y, Duysen E, Yaktine AL, Au A, Wang W, Birt DF. Dietary energy restriction inhibits ERK but not JNK or p38 activity in the epidermis of SENCAR mice. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22(4):607–12. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.4.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Garratt M, Nakagawa S, Simons MJ. Comparative idiosyncrasies in life extension by reduced mTOR signalling and its distinctiveness from dietary restriction. Aging Cell. 2016;15(4):737–43. doi: 10.1111/acel.12489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nakamura KD, Duffy PH, Lu MH, Turturro A, Hart RW. The effect of dietary restriction on myc protooncogene expression in mice: a preliminary study. Mech Ageing Dev. 1989;48(2):199–205. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(89)90051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Delmore JE, Issa GC, Lemieux ME, Rahl PB, Shi J, Jacobs HM, et al. BET bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy to target c-Myc. Cell. 2011;146(6):904–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]