Abstract

The protein α-Synuclein (aS) is a synaptic vesicle-associated regulator of synaptic strength and dopamine homeostasis with a pathological role in Parkinson’s disease. The normal function of aS depends on a membrane-associated conformation that is adopted upon binding to negatively charged lipid surfaces. Previously we found that the membrane-binding domain of aS is helical and suggested that it may exhibit an unusual structural periodicity. Here we present a study of the periodicity, topology, and dynamics of detergent micelle-bound aS using paramagnetic spin labels embedded in the micelle or attached to the protein. We show that the helical region of aS completes three full turns every 11 residues, demonstrating the proposed 11/3 periodicity. We also find that the membrane-binding domain is partially buried in the micelle surface and bends toward the hydrophobic interior, but does not traverse the micelle. Deeper submersion of certain regions within the micelle, including the unique lysine-free sixth 11-residue repeat, is observed and may be functionally important. There are no long-range tertiary contacts within this domain, indicating a highly extended configuration. The backbone dynamics of the micelle-bound region are relatively uniform with a slight decrease in flexibility observed toward the C-terminal end. These results clarify the topological features of aS bound to membrane-mimicking detergent micelles, with implications for aS function and pathology.

Keywords: Synuclein, Parkinson’s, amyloid, protein aggregation, membrane-associated proteins, helix periodicity

α-Synuclein (aS) is a highly conserved presynaptic protein that plays a role in synaptic strength maintenance and dopamine homeostasis. Evidence that aS controls synaptic strength comes from neuronal cell line and knockout mouse models (Abeliovich et al. 2000; Murphy et al. 2000; Cabin et al. 2002; Schluter et al. 2003) that display impaired synaptic response to repetitive stimuli and alterations in the number of reserve pool vesicles, suggesting that aS regulates reserve synaptic vesicles called upon when readily releasable vesicles are exhausted. aS may accomplish this in part by interacting with and regulating phospholipase D (PLD) (Jenco et al. 1998; Ahn et al. 2002; Outeiro and Lindquist 2003; Payton et al. 2004), an enzyme with a purported role in vesicular trafficking (Liscovitch et al. 2000). aS also appears to be involved in regulating intracellular dopamine levels at several points of control. Expression of aS alters synaptic membrane permeability to dopamine by interacting with the human dopamine transporter (hDAT), resulting in withdrawal of hDAT from the external membrane (Lee et al. 2001; Wersinger and Sidhu 2003; Wersinger et al. 2003). aS can also block dopamine synthesis by inhibiting tyrosine hydroxylase (Perez et al. 2002). In addition, aS can influence the activity of the vesicular dopamine transporter VMAT2 (Lotharius et al. 2002).

Several distinct conformations are potentially available to aS in vivo, including a free, intrinsically unstructured form (Weinreb et al. 1996) and a highly helical membrane associated form (Davidson et al. 1998). Based on the partial localization of aS to the surface of membranes (McLean et al. 2000; Cole et al. 2002) and synaptic vesicles (Iwai et al. 1995; Jensen et al. 1998) and on its functional association with several membrane-bound proteins such as PLD and hDAT, it is likely that the membrane bound form of the protein mediates its normal function(s). For the case of PLD interactions, this has been directly demonstrated (Payton et al. 2004). The specific form of aS that is responsible for its pathogenic role in vivo remains unclear. The protein is found aggregated into amyloid fibrils in the Lewy body deposits that are a characteristic hallmark of Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Spillantini et al. 1997, 1998). The lipid-free protein can form similar amyloid fibrils in vitro (Hashimoto et al. 1998; Conway et al. 2000; Serpell et al. 2000), suggesting that this form of the protein may be important for in vivo pathogenesis. Thus, it is possible that lipid binding could deplete the pool of aggregation-competent aS in cells. It has also been shown, however, that lipid binding can promote the self assembly of aS (Perrin et al. 2001; Cole et al. 2002; Lee et al. 2002; Jo et al. 2004), suggesting that the membrane-bound state could play a role in generating toxic aggregates. Finally, although an aggregation related toxic gain of function is a popular model for how aS causes neuronal death, it remains possible that perturbations in the normal function of aS contribute to the development of PD, especially considering that aS function is intimately linked to dopamine homeostasis and that PD is a dopamine deficit disorder. In this case the lipid-bound structure of aS could again be expected to mediate the role of the protein in disease.

Because lipid-bound aS may be involved in both the normal and toxic functions of the protein, it is important to know the structure of the protein in this state. Previously, we showed that detergent micelles can be used to effectively mimic the effects of lipid binding on aS (Eliezer et al. 2001) and used NMR spectroscopy to characterize the local structure of aS bound to such lipid-mimetic micelles (Bussell and Eliezer 2003, 2004). We found that the protein is divided into a highly helical lipid-binding N-terminal domain and an unstructured lipid-free C-terminal domain. Based on a mismatch between the apolipoprotein-like 11-residue repeats of the aS primary sequence and the canonical α-helical periodicity of 3.6 residues per turn, we proposed that the helical structure we observed in aS may adopt an altered periodicity, completing three full turns every 11 residues, as had been previously proposed for the protein apolipoprotein A-I (Segrest et al. 1999). Nevertheless, our previous results did not provide a direct measurement of the helical periodicity of the aS structure. Here we use paramagnetic spin labels in combination with NMR to perform such a measurement. Our results confirm the presence of 11/3-periodic helical structure that is partially buried in the membrane surface and does not traverse the membrane interior. We also demonstrate that there are no long-range tertiary contacts between different helical regions of aS and characterize the backbone dynamics of the micelle-bound protein.

Results

Use of paramagnetic reagents

Paramagnetic metal ions or spin labels induce a distance-dependent broadening of NMR signals and provide a tool for monitoring the spatial proximity of individual nuclei within proteins or other molecules to a paramagnetic-containing environment. To probe the proximity of individual sites within detergent micelle-bound aS to the micelle interior, to the aqueous phase, and to other sites within the protein we used a series of paramagnetic reagents, including Mn2+, 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (4-OH-TEMPO), 5- and 16-doxylstearate, and the reactive thiol specific spin label 1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-3-pyrroline-3-methyl methanethiosulfonate (MTSL; Toronto Research Chemicals).

Location of metal ions and spin labels with respect to the micelle

To characterize the location of the free metal ions and spin labels used in our studies with respect to the SDS micelle-forming detergent molecules, we measured the broadening of SDS acyl chain 13C NMR resonances induced in the presence of the various spin labels (data not shown). SDS carbon resonance assignments were based on a previous report (Kragh-Hansen and Riisom 1976) and resonances corresponding to carbons C1, C2, C3, C10, C11, and C12 (numbering from nearest to furthest from the sulfate group) were well resolved, whereas carbons C4–C9 formed a condensed group of resonances that could not be easily distinguished from one another. The observed SDS broadening pattern was consistent with the chemical characteristics of each paramagnetic reagent. Mn2+ selectively broadened resonances C1 and C2 near the micelle surface with a weaker effect on the C4–C9 cluster, consistent with exclusion of charged species from the micelle interior. On the other hand, the amphipathic small molecule 4-OH-TEMPO was found to be situated just below the micelle surface, broadening the C3 and C4–C9 resonances more than those of C1 and C2. However, 4-OH-TEMPO does not completely penetrate the micelle interior as the resonances of C10 throughC12 were relatively unaffected. The doxyl moiety attached to stearate at position 5 embeds deeper within the micelle than 4-OH-TEMPO, selectively broadening the C3 and C4–C9 resonances and having less effect on acyl carbons closer to the surface or further within. As expected, the deepest probe of the micelle interior was 16-doxylstearate, which selectively broadened the resonances of C11 and C12 at the micelle center. Thus the order of the four free paramagnetic reagents as a function of increasing distance from the micelle center is 16-doxylstearate, 5-doxylstearate, 4-OH-TEMPO, Mn2+.

Solvent accessibility of micelle-bound aS

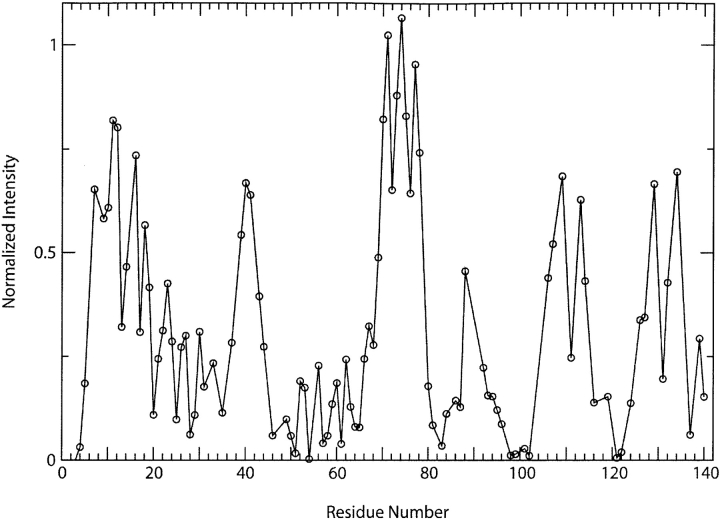

The membrane-associated structure of aS is divided into an N-terminal membrane-binding region and a C-terminal membrane-free tail in the presence of either SDS micelles or lipid vesicles (Eliezer et al. 2001). The majority of the membrane binding region displays NMR Cα chemical shifts and NOEs characteristic of helical structure, except for a small interruption near position 42, suggesting that membrane-bound aS forms a continuous helix with a single break (Bussell and Eliezer 2003). Sequence analysis suggests that this helix resides on the membrane surface and does not traverse the membrane (Davidson et al. 1998). To probe the solvent accessibility of aS bound to detergent micelles we measured the effect of the aqueous phase paramagnetic probe Mn2+ on aS NMR resonance intensities. Figure 1 ▶ shows NMR backbone resonance intensities from a proton–nitrogen correlation spectrum of aS in the presence of Mn2+, normalized by their intensities in the absence of the broadening reagent. Resonances that are weakly or not broadened (values near 1 in the figure) correspond to locations in the protein backbone that are sequestered from the aqueous phase reagent. Within the N-terminal lipid-binding region of the protein (residues 1– ~94) there are three distinct maxima, centered around positions 10, 42, and 74, indicating that these regions are better protected from solvent than the remainder of the domain.

Figure 1.

Effect of the aqueous spin label Mn2+ on NMR backbone resonances of aS. Resonance intensities from a proton–nitrogen correlation spectrum of micelle-bound aS in the presence of 100 μM MnCl2, normalized by resonance intensities in an equivalent spectrum collected in the absence of the spin label, are shown as a function of the corresponding sequence position.

The most striking feature of the data is the region from residues 68 to 79, which is especially well protected from Mn2+-induced broadening, suggesting somewhat deeper burial within the membrane. This stretch of the protein precisely coincides with the sixth of seven tandem 11-mer repeats in aS (Fig. 2 ▶). Importantly, this particular repeat is unique in that it lacks either of the two lysines that are a highly conserved feature of the repeats, and that form a charged boundary between the hydrophobic and hydrophilic faces of the amphipathic aS helix (Bussell and Eliezer 2003). This suggests that these lysines are important for determining the depth at which helical segments “float” on the membrane surface, an idea originally proposed as part of the snorkeling model of Segrest et al. (1992). Also interesting is the protection seen around position 42. This position was identified by us and others as the only location where the structure of lipid-bound aS appears to deviate from its helical geometry (Bussell and Eliezer 2003; Chandra et al. 2003). The current data suggest a burial of a few residues at this location deeper within the membrane, rather than a looping out into the solvent. Tyrosine 39, one of the few aromatic side chains in the lipid-binding region of aS, may play a role in this burial, as well as in the local structural perturbation, as we previously suggested (Bussell and Eliezer 2003). The protection observed around residue 12 does not correlate as clearly with a sequence or structural feature, although the presence of several hydrophobic residues (Phe 4, Met 5, and Leu 8) in the eight N-terminal residues that precede the first of the 11-mer repeats may serve to pull this segment of the protein deeper into the micelle.

Figure 2.

Amino acid sequences of human aS and bS. Differences from the aS sequence are indicated in boldface. The imperfect 11-mer repeat regions are delineated by spaces and the core sequence of each repeat is underlined.

We also observed unexpected protection from solvent in the C-terminal tail of the protein, consisting of the last ~40 residues in the sequence. This segment is not well structured according to NMR chemical shifts and NOEs, and was expected to be highly solvent exposed. In addition, the negative character of this region of the protein might be expected to attract the positively charged metal ions. The effects of Mn2+ in this region, however, may be complicated by several considerations. First is the fact that a significant degree of amide proton exchange is expected in this region due to its poorly structured nature. This leads to a rather weak intensity for many resonances, including positions 106, 107, 109, 129, 132, and 134, even in the absence of spin label. These positions account for much of the apparent protection observed in the C-terminal tail. In addition, it is likely that the concentration of the positively charged Mn2+ ion is greater at the even more highly negatively charged micelle surface and that the C-terminal tail, being free of the surface, may therefore experience a much lower effective spin label concentration. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that some structural feature that is not reflected in chemical shifts or NOEs is responsible for the observed protection, especially in light of recent results suggesting a slow time-scale interaction between the C-terminal tail of aS and the lipid-binding region of the protein (Fernandez et al. 2004). In this regard, it is noteworthy that the broadening data indicate any structure in the C-terminal tail might be divided into two segments, one on either side of position 122. This is to some extent consistent with the Cα chemical shifts in this region (Bussell and Eliezer 2003), which although largely indicative of random coil, show two regions of similar shifts on either side of position 122, and by the dynamics data for both the free state (Bussell and Eliezer 2001) and lipid-bound state (data shown below) of the protein, which suggest a slightly lower mobility at position 122 than on either side.

Helix periodicity of micelle-bound aS

An additional and interesting observation is that throughout the lipid-binding region, there appears to be a three- to four-residue periodicity in the Mn2+ data. This periodicity is generally consistent with typical helical structure, where every third or fourth residue is found on the same face of a helix, and would therefore be better or more poorly shielded from solvent. In previous work, we suggested that the periodicity of the helical structure in lipid-bound aS may deviate from the canonical 3.6 residues per turn (or 18 residues per five full turns) of an α-helix and may instead reflect the 11-residue periodicity of the primary sequence by forming three full turns every 11 residues (Bussell and Eliezer 2003). The periodicity of spin label induced resonance broadening provides us with an opportunity to directly test this hypothesis. However, the effects of Mn2+ were observed to be quite strong, with large intensity differences between resonances from well-protected and poorly protected regions, making it difficult to analyze the underlying periodicity in the data. This may be a result of a high concentration of Mn2+ close to the negatively charged micelle surface, as mentioned above. Therefore, we decided to use micelle-resident spin labels, where the difference in distance between the spin label and either side of a surface bound helix might be expected to be smaller, leading to a more even broadening effect.

Proton–nitrogen correlation spectra of aS bound to micelles in the presence of 5-doxylstearate, 16-doxylstearate, and 4-OH-TEMPO displayed resonance broadening that was more uniform across the lipid-binding domain of aS and that exhibited a three- to four-residue periodicity, as expected (not shown). To evaluate whether the periodicity in the data could be used to discriminate between the two types of helix periodicity being considered (three full turns over 11 residues or five turns over 18 residues) we analyzed resonance intensities as a function of the angle at which each residue would lie on a helical pinwheel diagram for each possible periodicity. For an 11/3 helix, each residue would fall at one of 11 possible azimuthal angles, whereas for a canonical 18/5 helix, 18 such angles are possible. When plotted against the correct periodicity, the broadening data should yield a sine wave, reflecting the oscillation in the distance between each successive helix site and the micelle-resident spin label. If a sine wave is not observed, this implies a mismatch between the periodicity of the data and that of the model. Figure 3 ▶ shows the average intensity of resonances originating from each azimuthal position in an 11/3 and an 18/5 model of the aS lipid-binding domain for each of the three micelle-resident spin labels, 5-doxylstearate, 16-doxylstearate, and 4-OH-TEMPO. All three data sets show a sinusoidal modulation when plotted according to the 11/3 model, whereas no such modulation is seen in plots generated according to the canonical 18/5 model. These results demonstrate that the fundamental periodicity of the helical structure of micelle-bound aS is 11 residues per three full turns. Note that data from the membrane-free unstructured C-terminal region do not correlate to either helical model, consistent with the absence of helical structure in this region (not shown).

Figure 3.

Correlation of the resonance broadening effects of micelle embedded paramagnetic spin labels 5- and 16-doxylstearate and 4-OH-TEMPO with two different periodicities, 11/3 and 18/5, of micelle-bound aS. The average resonance intensity for all residues at each possible helix projection angle for either an 11/3 (left panels) or 18/5 (right panels) periodicity are shown from spectra of micelle-bound aS in the presence of each of the three spin label reagents. Only residues previously determined to adopt helical structure (1–94) are included. A weaker (stronger) intensity at a given projection angle indicates that residues at this position on the helix are on average closer to (further from) the micelle interior. A sinusoidal pattern is expected for a periodicity that corresponds to that of the actual helical structure of micelle-bound aS.

In addition to establishing the periodicity of the helical structure of micelle-bound aS, the analysis above allows us to determine the orientation of the helix with respect to the micelle surface, because those residues closest to the membrane interior will experience the greatest degree of broadening and will fall at the minimum of the sinusoidal curves in Figure 3 ▶. As expected, this minimum occurs for residues that fall at in the middle of the hydrophobic face of the amphipathic helix formed by the aS sequence.

Finally, the phase of the sinusoidal broadening profiles induced by all three micelle embedded spin labels (Fig. 3 ▶) is the same. Spin labels on opposite sides of the helix backbone would induce broadening profiles with the same periodicity but with an opposite relative phase. Therefore, we can conclude that all three spin label moieties lie deeper within the micelle than the aS backbone. Collectively these spin labels probe the region from acyl carbon C12 at the center of the micelle to carbon C4 just below the head group region suggesting that on average, the aS backbone penetrates no deeper into micelles than SDS carbon C4. This result is consistent with a recent ESR study of acyl chain disordering by aS (Ramakrishnan et al. 2003).

Helix curvature of micelle-bound aS

In our working model of lipid-bound aS, the protein binds to the surface of membranes in an α1/3-helical conformation that places its hydrophobic face in continuous contact with the membrane. This would be expected to cause aS to curve in a manner similar to that of other membrane-surface associated helices (Chou et al. 2002). Such curvature, in combination with the difference in the dielectric constant of the hydrocarbon and the aqueous environments, tends to decrease hydrogen bond lengths for regions of the backbone facing the membrane relative to solvent exposed regions. Any such shortening of hydrogen bonds should again reflect the intrinsic periodicity of the helix. Therefore, we investigated the helix curvature of micelle-bound aS by measuring the deviation of NMR amide proton chemical shifts from their expected random coil values. These chemical shifts are sensitive to the length of backbone hydrogen bonds in helices, with longer hydrogen bond lengths leading to smaller (more negative) amide proton chemical shift deviations (Zhou et al. 1992). Figure 4 ▶ shows the amide proton chemical shift deviations of micelle-bound aS plotted as a function of the predicted azimuthal angle for 11/3 and 18/5 helical periodicities. When plotted according to the 11/3 model of the membrane-binding helical region (Fig. 4A ▶) the data show a sinusoidal modulation that is not present when the data are plotted according to the canonical 18/5 helical model (Fig. 4B ▶). This again confirms the 11/3 periodicity of the aS helical structure, and also confirms that this structure curves toward the detergent micelle. The phase of the sinusoidal data also shows that the hydrophobic face of the helical aS structure exhibits the greatest shortening of hydrogen bond lengths, consistent with the expected exposure of this face to the membrane.

Figure 4.

Backbone amide proton chemical shift deviations. The average backbone amide proton chemical shift deviation from the expected random coil value at each possible helix projection angle for either an 11/3 (A) or an 18/5 (B) periodicity are shown. Only residues previously determined to adopt helical structure (1–94) are included. Negative amide proton chemical shift deviations are associated with longer hydrogen bonds and a more hydrophilic environment. Again, a sinusoidal pattern is expected for a periodicity that accurately represents the actual helical structure of the micelle-bound protein.

Topology of micelle-bound aS

In addition to suggesting the presence of 11/3 helical periodicity in micelle-bound aS, our previous results (Bussell and Eliezer 2003) and those of others (Chandra et al. 2003) indicated a single location at sequence positions 42 and 43 where the continuously helical structure of the protein was interrupted. This interruption raised the possibility of a bend, a kink, or even a hairpin between the two helical segments of the protein and of possible interhelix interactions. Although NOE data gave no indication of any long-range tertiary structure, helix–helix packing can involve limited tertiary packing and can be difficult to assess based on NOE data, especially in the current system where chemical shift degeneracy is high. Therefore, to more thoroughly assess the long-range topology of the lipid-binding domain of aS, we created a series of cysteine mutants of C-terminally truncated aS, to which we attached a spin label reagent and evaluated the effects of the spin labels on resonances originating from elsewhere in the micelle-bound protein. Because the broadening effect of a spin label containing an unpaired electron extends to approximately 15 Å, this technique, also known as paramagnetic relaxation enhancement, can be used like a very long range NOE to detect the proximity of protein amide groups to the spin-labeled site (Gillespie and Shortle 1997). Figure 5 ▶ shows plots of resonance intensities (from proton–nitrogen correlation spectra) as a function of sequence position for three different spin-labeled mutants, G31C, H50C, and E83C. The intensities are normalized by the intensity of resonances in spectra of the mutants collected in the absence of the spin label reagents. Each of these plots shows a dramatic attenuation of the signal intensity for resonances originating from residues near the spin-labeled site, with all locations within 10 residues of the labeled sites attenuated by a factor of 2 or more. Ten helical residues span a distance of approximately 15 Å, confirming the expected range at which the spin labels exert strong effects. Although local broadening is clearly observed, there is no evidence for dramatic broadening at sites far removed in sequence from the labeling site. Data from several other mutants (S9C, E20C, S42C, E61C, T72C, and G93C) yield similar results (not shown). Three regions of aS, around positions 6, 40, and 96, appear to be mildly broadened in all of our data sets, irrespective of whether the spin-labeled site is closer to or further from these locations. These sites have in common the property of being adjacent to the only three aromatic residues in the lipid-binding domain of aS, Phe 4, Tyr 39, and Phe 94. Therefore, this effect may be a result of nonspecific hydrophobic interactions between excess free spin label and these aromatic side chains. Because this broadening is not correlated with the location of the covalently attached spin label, it is unlikely to reflect the distance between the labeled site and these three locations. In no case do we see evidence for any broadening that would be consistent with long-range tertiary contacts, indicating that the helical membrane-bound domain of aS is highly extended without any interhelical or other long-range contacts.

Figure 5.

Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement data for three different cysteine mutants of C-terminally truncated detergent micelle-bound aS labeled with the paramagnetic nitroxide spin label MTSL. The intensities of backbone resonances from proton–nitrogen correlation spectra, normalized to those in spectra of spin label-free protein, are displayed as a function of sequence position for each sample. In general, only residues nearby in sequence to the labeling site show significant resonance attenuation, suggesting a lack of long-range tertiary contacts in the protein. The localized attenuation observed around positions 4, 40, and 96 are likely due to nonspecific interactions with free spin label at these positions and are not a result of tertiary interactions.

Backbone dynamics of micelle-bound aS

Backbone motions can influence many of the parameters that we have used here and in previous work to characterize the structural properties of micelle-bound aS. To account for such effects, and because protein dynamics can also play an important role in protein function or dysfunction, we used NMR to characterize the backbone motions of micelle-bound aS on the picosecond to nanosecond time scale by measuring the 15N relaxation rate constants R1 and R2 and the heteronuclear 1H-15N steady-state NOE. The data, shown in Figure 6 ▶, demonstrate that the dynamics of the aS backbone are relatively uniform throughout the lipid-binding domain of the protein. There is evidence for increased motions for the N-terminal six to eight residues as indicated by lower steady-state NOE and R2 values, and there is similarly a large increase in backbone motions past residue 96 indicated by a sharp drop in the same two parameters. There is also evidence that mobility increases significantly in moving from residue 80 to 85, and for somewhat greater flexibility surrounding position 34 in the sequence. Interestingly, there is some evidence in the R2 data for a three-to four-residue periodicity, suggesting that the opposite faces of the amphipathic helical structure may experience slight differences in slower backbone motions. Although this, in principle, provides an additional opportunity to assess the helical periodicity of aS, the effect is too weak to effectively discriminate between the two possible models in this case. We note that the observed variations in the backbone dynamics of the lipid-binding region of aS show no indication of any effect that would significantly alter or compromise the interpretation of the spin-labeling results presented above or our previous NOE- and chemical shift-based analyses. Beyond position 100, the chain is highly flexible, as would be expected for the poorly structured C-terminal tail, although as mentioned above there is an indication for two more flexible regions surrounding a lower mobility site around position 122.

Figure 6.

NMR relaxation parameters for backbone 15N nuclei in micelle-bound aS. R1 (longitudinal relaxation rate), R2 (transverse relaxation rate), and the steady-state heteronuclear 1H-15N NOE are plotted as a function of residue number. The NOE data reflect the presence of relatively faster motions, with values near 1 indicating a lack of motion and smaller values indicating increasing mobility. The R2 data reflect slower motions, with higher values of R2 indicating a greater degree of slower vs. faster motions. The high degree of flexibility of the lipid-free C-terminal tail is easily evident in both the NOE and R2 data. The R1 data are relatively less sensitive than the NOE and R2 measurements.

Discussion

The lipid-bound conformation of aS mediates the normal functions of the protein and may also participate in the self-assembly of aS into amyloid fibrils. We previously showed that this conformation was highly helical, and proposed an unusual 11/3 helix periodicity based on our direct measurements of secondary structure, an analysis of helical wheel projections of aS, and use of the algorithm LOCATE (Jones et al. 1992; Segrest et al. 2002) designed to detect amphipathic lipid-binding helices (Bussell and Eliezer 2003). The proposed periodicity reflects the primary sequence of aS, which contains seven 11-residue amino acid repeats in which side chains with similar charge and hydrophobicity occupy specific positions. When mapped onto a helical wheel with an 11/3 periodicity and viewed along the helix axis, the side chains of each 11-mer repeat map to one of three identifiable domains: the charged/polar face, the hydrophobic/apolar face, or the lysine-rich boundary between the two faces. In this report we find that micelle resident paramagnetic spin labels induce a periodic pattern of broadening in the lipid-binding region of aS that correlates with a helical model possessing 11/3 periodicity, but not with a canonical 18/5 periodicity helical model. This periodicity is also evident, in the absence of any spin labels, in amide proton chemical shift deviations, which reflect variations in hydrogen bond lengths caused by helix curvature, an intrinsic structural feature of the micelle-bound protein. Together, these results provide direct evidence for the presence of 11/3 periodicity in the helical structure of micelle-bound aS.

This evidence is consistent with and complementary to recent results of ESR measurements, which also support an 11/3 periodicity in lipid-bound aS (Jao et al. 2004). While the ESR data probed a relatively limited region of the protein, the NMR data reflect the entire lipid-binding domain. In addition the NMR approach is less likely to perturb either the protein’s structure or its interactions with lipid surfaces since neither modification of the protein’s sequence nor direct attachment of a spin label to the protein are required. The detailed structural parameters associated with this unusual helical periodicity and how they compare with those found in more typical α-helical structure remain to be elucidated, as pointed out also by Jao et al. (2004). In particular it is noteworthy that most helices even in globular proteins are amphipathic, curved, and have a range of periodicities (Blundell et al. 1983). Nevertheless, it appears that the 11/3 periodicity is sufficiently different structurally and functionally to be uniquely suited for a certain type of lipid interaction that is exemplified by aS and the apolipoprotein family, as well as by several other families of reversibly lipid-binding proteins that we identified previously in a protein sequence database search (Bussell and Eliezer 2003).

By using both an aqueous phase spin label and spin labels residing at different depths within the micelle we are also able to provide insights into the depth of penetration of the helical structure of aS into the hydrophobic micelle or lipid bilayer interior, as well as into the determinants of this depth. All three micelle-resident spin labels were shown to be on the same side of the helical aS structure, confirming that this structure resides entirely on the surface of the micelle or bilayer, and does not traverse the hydrophobic interior. Also, by explicitly determining the location of the TEMPO spin label to be nearest to the C3 and C4 carbons of SDS, we show that the protein backbone does not on average settle deeper than this into the hydrophobic interior and therefore remains close to the headgroup region. However, our data also show that not all regions of the protein penetrate beyond the headgroup region to the same extent. In particular the sixth of the seven 11-residue repeats of the protein is submerged deeper below the headgroup region than the remainder of the protein, precluding access by the aqueous spin label reagent Mn2+. This observation is interesting for several reasons. First, this repeat is the only aS repeat that lacks either of the highly conserved lysine residues that are found at the interface between the hydrophobic and hydrophilic faces of the membrane-bound helical structure of the protein. These lysines have been predicted to anchor this class of lipid-binding amphipathic helices (also called type A2 helices) just below the lipid headgroup region by extending upward from the hydrophobic layer below and interacting with negatively charged headgroups (Segrest et al. 1992). This interaction is thought to be partly behind the specificity of aS binding to membranes containing negatively charged lipids (Davidson et al. 1998; Jo et al. 2000; Bussell and Eliezer 2004) and the documented role of electrostatics in such binding (Davidson et al. 1998; Jo et al. 2000). The fact that the only aS repeat lacking interfacial lysines sits deeper below the headgroup region than the remainder of the protein provides significant support for the idea that the lysines play a critical role in determining the penetration depth of helices into membranes (the snorkeling model; Segrest et al. 1992).

Although the absence of lysines in repeat six of aS likely underlies the deeper burial of this repeat in the membrane, the consequences of this burial for the function of the protein and its role in disease are less clear. From the perspective of normal aS function, this repeat lies in the middle of a region that was recently demonstrated to be important for inhibition of PLD2 (Payton et al. 2004), one of the few well-documented functional roles of aS (Jenco et al. 1998; Ahn et al. 2002; Outeiro and Lindquist 2003). This inhibition requires aS to be in its membrane-bound helical conformation, suggesting a direct interaction between helical regions of aS and membrane-associated PLD2 (Payton et al. 2004). Interestingly, PLD2 is also inhibited by β-Synuclein (bS), a closely related homolog of aS, which is, however, missing residues corresponding to aS residues 74–84 (Jenco et al. 1998; Payton et al. 2004). Although these missing residues include part of aS repeat six, the resulting sixth repeat of bS also lacks any interfacial lysines (Fig. 2 ▶), suggesting that it would similarly be submerged more deeply in the membrane than other bS repeats. Therefore, it is possible that the functional interactions between PLD2 and aS or bS depend on the depth of burial of repeat six within the lipid bilayer.

A third interesting feature of aS repeat six is that it corresponds quite closely to a 12-residue stretch of the protein (residues 71–82) that was identified as a potential nucleation site for aggregation of aS into amyloid fibrils (Giasson et al. 2001). Burial of this region in the membrane could have consequences for aS aggregation irrespective of whether aS amyloid fibril formation occurs via the highly unstructured cytoplasmic form of the protein or the lipid-bound form in vivo, a question that remains open. If aggregation occurs from the membrane-associated state, the deeper submersion of repeat six in the membrane would suggest that its role in nucleation would occur in the context of a highly hydrophobic environment, which would significantly alter the relative strengths of the interactions involved. On the other hand in the cytoplasm the lack of charge that apparently leads to submersion of repeat six could play a significant role in driving this region to seek intermolecular interactions in order to escape the polar aqueous environment.

In addition to elucidating structural features of aS such as helical periodicity and depth of burial that are intrinsically related to its interactions with the micelle or lipid surface, our results also shed new light on the global topology of the protein. In earlier work, we posited based on the low dispersion of amide proton chemical shifts in proton–nitrogen correlation spectra that micelle-bound aS was unlikely to adopt a compact globular conformation with tertiary interactions (Eliezer et al. 2001), and this was supported by our inability to observe long-range NOEs (Bussell and Eliezer 2003). By using spin labels attached to different sites in aS, we are now able to directly confirm the highly extended nature of the helical structure of micelle-bound aS. This methodology enables us to observe the approach of any region of the protein to within 15 Å of any of the labeled sites, essentially providing a long-range NOE capability. Our data convincingly demonstrate that at no point do regions of the membrane-binding domain of aS that are distant in sequence approach one another closely in space, confirming the lack of any long-range tertiary interactions and ruling out the possibility of hairpin formation around the one break in the continuously helical structure. This result is again consistent with recently reported ESR studies of lipid-bound aS, which indicated an absence of long-range interactions based on the lineshapes of spin labels attached to various sites in the protein (Jao et al. 2004). The ESR lineshapes, however, are only evaluated in terms of the general environment of the spin label (i.e., surface exposed or buried) and are not directly sensitive to spatial proximity in the way that NMR signal intensities are.

Recently it was also proposed that the break in the helical structure that is evident in NMR data of micelle-bound aS may not exist in the lipid vesicle-bound form of the protein (Jao et al. 2004). This argument was based on ESR data showing a lack of flexibility and membrane interactions at the site of the break in the vesicle-bound state. However, the results we report here for the micelle-bound protein are entirely consistent with these ESR observations, showing that residues 42–44 do not exhibit greater flexibility than the remainder of the protein (Fig. 6 ▶), and that these sites are indeed buried deeper within the membrane than the surrounding regions (Fig. 1 ▶). Therefore, it appears that the micelle- and lipid-bound forms of the protein behave similarly at this location, and that it is premature to conclude that the interruption of the helical structure of aS does not occur in the lipid vesicle-bound state of the protein. We have not characterized the precise nature of this interruption beyond the requirement that it lead to random coil-like Cα chemical shifts and weaker interresidue amide proton NOEs (Bussell and Eliezer 2003), but it appears likely that it is not a flexible loop region, but rather a short and somewhat ordered deviation from helical structure into the membrane interior. It is also worth noting that although a spherical detergent micelle would indeed present a very highly curved surface for interacting with a single long aS helix, we do not as of yet have any information regarding the geometry of the micelle in the aS–micelle complex, and the presence of the protein may cause this geometry to deviate significantly from that of a sphere.

Conclusions

We have provided direct evidence that the helical structure of membrane-bound aS adopts the unusual 11/3 periodicity that we proposed previously. In addition, we have demonstrated that this lipid-associated helical structure does not traverse the membrane interior and is highly extended, lacking any long-range tertiary structure. We also determined that the sixth of the seven 11-residue repeats of aS is submerged more deeply within the membrane than the remainder of the protein, suggesting that interfacial lysines in the other repeats play a key role in positioning the protein on the membrane surface. Finally, our results also indicate that the one break in this extended helical structure is probably ordered and lies deeper within the membrane, and suggest that this break is preserved even when the protein is bound to lipid vesicles. Taken together, these observations considerably improve our view of the structure of lipid-bound aS and bring into focus a number of interesting questions. What is the precise role of the unusual 11/3 helical periodicity in facilitating the reversible lipid interactions of aS and other proteins containing this motif? How does the repetitive and highly extended structure of the lipid-binding domain engage in specific interactions with proteins such as PLD? Is the deeper burial of repeat six functionally significant, and if so, is a functional requirement responsible for the very features that make this repeat an amyloid fibril nucleation site? What is the precise structure adopted at the break in the helical conformation of the lipid-bound protein and what, if any, is its functional role? Future experiments designed to answer these questions are expected to further improve our understanding of the biology and pathology associated with this PD-linked protein.

Materials and methods

Recombinant proteins used in this study were produced and purified as previously described (Bussell and Eliezer 2004). Both full-length aS and truncation constructs consisting of only of the first 102 residues of the human aS sequence were used. In all NMR studies presented here we used 2H-15N doubly isotope labeled protein. NMR samples contained approximately 0.5 mM aS and 40 mM 2H-SDS in PBS at pH 7.4. NMR data were acquired at 40°C on a 600-MHz Varian UNITY spectrometer using a triple resonance probe equipped with pulsed field gradients. Proton–nitrogen correlation spectra (HSQC) were used to monitor spin-label-induced relaxation of protein resonances and one-dimensional proton-decoupled natural abundance carbon spectra were used to monitor spin-label-induced relaxation of SDS acyl carbon resonances. R1, R2, and 1H-15N heteronuclear NOE measurements were performed as previously described for the free protein (Bussell and Eliezer 2001). Spectral widths of 5400 Hz and 1460 Hz with 512 and 128 complex points were used in the proton and nitrogen dimensions respectively. Resonances in crowded spectral regions were excluded from analysis if their heights could not be determined accurately. Amide proton secondary shifts were calculated using random coil values from Wishart et al. (1995).

Free spin label compounds were added to protein samples using concentrated stock solutions and then gently but thoroughly mixed before transfer to the NMR tube. Final concentrations of the four free spin labels were 100 μM MnCl2, 10 μM 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (4-OH-TEMPO), 0.7 mM 5- and 16-doxylstearate. The highly reactive thiol-specific spin label 1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-3-pyrroline-3-methyl methanethiosulfonate (MTSL, Toronto Research Chemicals) was attached to cysteine sites introduced into the aS sequence using site-directed mutagen-esis at positions 9, 20, 31, 42, 50, 61, 72, 83, and 93. Spin labeled protein was prepared by adding a 10-fold excess of spin label to freshly prepared samples of protein. Excess spin label was not removed from the samples, as nonspecific interactions between the spin label and the protein were not anticipated to be significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIA, NIH, grant AG19391 (to D.E.) and by a gift from Herbert and Ann Siegel (to D.E.).

Note added in proof

While this paper was under review two new manuscripts appeared (Ulmer et al. 2004; Bisaglia et al. 2005) describing complementary studies of the structure and dynamics of micelle-bound aS. The results presented are generally consistent with our own findings. Ulmer et al. (2004) use a paramagnetic label at position 87 to detect a proximity between the two helical segments of aS, while our data, especially from samples spin-labeled at positions 72, 61, 20, and 9, do not show significant broadening at locations that would most closely approach them in the apposing helix. This could result from the spin labels adopting orientations that place them too far from the apposing helix, or it could reflect an altered topology in the truncated construct that we used for our PRE measurements. Further efforts will be required to clarify this issue.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.041255905.

References

- Abeliovich, A., Schmitz, Y., Farinas, I., Choi-Lundberg, D., Ho, W.H., Castillo, P.E., Shinsky, N., Verdugo, J.M., Armanini, M., Ryan, A., et al. 2000. Mice lacking α-synuclein display functional deficits in the nigrostriatal dopamine system. Neuron 25 239–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, B.H., Rhim, H., Kim, S.Y., Sung, Y.M., Lee, M.Y., Choi, J.Y., Wolozin, B., Chang, J.S., Lee, Y.H., Kwon, T.K., et al. 2002. α-Synuclein interacts with phospholipase D isozymes and inhibits pervanadate-induced phospholipase D activation in human embryonic kidney-293 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277 12334–12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisaglia, M., Tessari, I., Pinato, L., Bellanda, M., Giraudo, S., Fasano, M., Bergantino, E., Bubacco, L., and Mammi, S. 2005. A topological model of the interaction between α-synuclein and sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles. Biochemistry 44 329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blundell, T., Barlow, D., Borkakoti, N., and Thornton, J. 1983. Solvent-induced distortions and the curvature of α-helices. Nature 306 281–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussell Jr., R. and Eliezer, D. 2001. Residual structure and dynamics in Parkinson’s disease-associated mutants of α-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 276 45996–46003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2003. A structural and functional role for 11-mer repeats in α-synuclein and other exchangeable lipid binding proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 329 763–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2004. Effects of Parkinson’s disease-linked mutations on the structure of lipid-associated α-synuclein. Biochemistry 43 4810–4818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabin, D.E., Shimazu, K., Murphy, D., Cole, N.B., Gottschalk, W., McIlwain, K.L., Orrison, B., Chen, A., Ellis, C.E., Paylor, R., et al. 2002. Synaptic vesicle depletion correlates with attenuated synaptic responses to prolonged repetitive stimulation in mice lacking α-synuclein. J. Neurosci. 22 8797–8807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, S., Chen, X., Rizo, J., Jahn, R., and Sudhof, T.C. 2003. A broken α-helix in folded α-Synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 278 15313–15318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou, J.J., Kaufman, J.D., Stahl, S.J., Wingfield, P.T., and Bax, A. 2002. Micelle-induced curvature in a water-insoluble HIV-1 Env peptide revealed by NMR dipolar coupling measurement in stretched polyacrylamide gel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124 2450–2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole, N.B., Murphy, D.D., Grider, T., Rueter, S., Brasaemle, D., and Nussbaum, R.L. 2002. Lipid droplet binding and oligomerization properties of the Parkinson’s disease protein α-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 277 6344–6352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway, K.A., Harper, J.D., and Lansbury Jr., P.T. 2000. Fibrils formed in vitro from α-synuclein and two mutant forms linked to Parkinson’s disease are typical amyloid. Biochemistry 39 2552–2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, W.S., Jonas, A., Clayton, D.F., and George, J.M. 1998. Stabilization of α-synuclein secondary structure upon binding to synthetic membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 273 9443–9449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliezer, D., Kutluay, E., Bussell Jr., R., and Browne, G. 2001. Conformational properties of α-synuclein in its free and lipid-associated states. J. Mol. Biol. 307 1061–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, C.O., Hoyer, W., Zweckstetter, M., Jares-Erijman, E.A., Subramaniam, V., Griesinger, C., and Jovin, T.M. 2004. NMR of α-synuclein-polyamine complexes elucidates the mechanism and kinetics of induced aggregation. EMBO J. 23 2039–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giasson, B.I., Murray, I.V., Trojanowski, J.Q., and Lee, V.M. 2001. A hydrophobic stretch of 12 amino acid residues in the middle of α-synuclein is essential for filament assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 276 2380–2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, J.R. and Shortle, D. 1997. Characterization of long-range structure in the denatured state of staphylococcal nuclease. I. Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement by nitroxide spin labels. J. Mol. Biol. 268 158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, M., Hsu, L.J., Sisk, A., Xia, Y., Takeda, A., Sundsmo, M., and Masliah, E. 1998. Human recombinant NACP/α-synuclein is aggregated and fibrillated in vitro: Relevance for Lewy body disease. Brain Res. 799 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai, A., Masliah, E., Yoshimoto, M., Ge, N., Flanagan, L., de Silva, H.A., Kittel, A., and Saitoh, T. 1995. The precursor protein of non-A β component of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid is a presynaptic protein of the central nervous system. Neuron 14 467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jao, C.C., Der-Sarkissian, A., Chen, J., and Langen, R. 2004. Structure of membrane-bound α-synuclein studied by site-directed spin labeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101 8331–8336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenco, J.M., Rawlingson, A., Daniels, B., and Morris, A.J. 1998. Regulation of phospholipase D2: Selective inhibition of mammalian phospholipase D iso-enzymes by α- and β-synucleins. Biochemistry 37 4901–4909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, P.H., Nielsen, M.S., Jakes, R., Dotti, C.G., and Goedert, M. 1998. Binding of α-synuclein to brain vesicles is abolished by familial Parkinson’s disease mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 273 26292–26294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo, E., McLaurin, J., Yip, C.M., St. George-Hyslop, P., and Fraser, P.E. 2000. α-Synuclein membrane interactions and lipid specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 275 34328–34334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo, E., Darabie, A.A., Han, K., Tandon, A., Fraser, P.E., and McLaurin, J. 2004. α-Synuclein-synaptosomal membrane interactions: Implications for fibrillogenesis. Eur. J. Biochem. 271 3180–3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.K., Anantharamaiah, G.M., and Segrest, J.P. 1992. Computer programs to identify and classify amphipathic α helical domains. J. Lipid Res. 33 287–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragh-Hansen, U. and Riisom, T. 1976. Complexes of aliphatic sulfates and human-serum albumin studied by 13C nuclear-magnetic-resonance spectroscopy. Eur. J. Biochem. 70 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, F.J., Liu, F., Pristupa, Z.B., and Niznik, H.B. 2001. Direct binding and functional coupling of α-synuclein to the dopamine transporters accelerate dopamine-induced apoptosis. FASEB J. 15 916–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.J., Choi, C., and Lee, S.J. 2002. Membrane-bound α-synuclein has a high aggregation propensity and the ability to seed the aggregation of the cytosolic form. J. Biol. Chem. 277 671–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liscovitch, M., Czarny, M., Fiucci, G., and Tang, X. 2000. Phospholipase D: Molecular and cell biology of a novel gene family. Biochem. J. 345 401–415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotharius, J., Barg, S., Wiekop, P., Lundberg, C., Raymon, H.K., and Brundin, P. 2002. Effect of mutant α-synuclein on dopamine homeostasis in a new human mesencephalic cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 277 38884–38894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean, P.J., Kawamata, H., Ribich, S., and Hyman, B.T. 2000. Membrane association and protein conformation of α-synuclein in intact neurons. Effect of Parkinson’s disease-linked mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 275 8812–8816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, D.D., Rueter, S.M., Trojanowski, J.Q., and Lee, V.M. 2000. Synucleins are developmentally expressed, and α-synuclein regulates the size of the presynaptic vesicular pool in primary hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 20 3214–3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outeiro, T.F. and Lindquist, S. 2003. Yeast cells provide insight into α-synuclein biology and pathobiology. Science 302 1772–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payton, J.E., Perrin, R.J., Woods, W.S., and George, J.M. 2004. Structural determinants of PLD2 inhibition by α-synuclein. J. Mol. Biol. 337 1001–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez, R.G., Waymire, J.C., Lin, E., Liu, J.J., Guo, F., and Zigmond, M.J. 2002. A role for α-synuclein in the regulation of dopamine biosynthesis. J. Neurosci. 22 3090–3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, R.J., Woods, W.S., Clayton, D.F., and George, J.M. 2001. Exposure to long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids triggers rapid multimerization of synucleins. J. Biol. Chem. 276 41958–41962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan, M., Jensen, P.H., and Marsh, D. 2003. α-Synuclein association with phosphatidylglycerol probed by lipid spin labels. Biochemistry 42 12919–12926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluter, O.M., Fornai, F., Alessandri, M.G., Takamori, S., Geppert, M., Jahn, R., and Sudhof, T.C. 2003. Role of α-synuclein in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced parkinsonism in mice. Neuroscience 118 985–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrest, J.P., Jones, M.K., De Loof, H., Brouillette, C.G., Venkatachalapathi, Y.V., and Anantharamaiah, G.M. 1992. The amphipathic helix in the exchangeable apolipoproteins: A review of secondary structure and function. J. Lipid Res. 33 141–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrest, J.P., Jones, M.K., Klon, A.E., Sheldahl, C.J., Hellinger, M., De Loof, H., and Harvey, S.C. 1999. A detailed molecular belt model for apolipo-protein A-I in discoidal high density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 274 31755–31758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrest, J.P., Jones, M.K., Mishra, V.K., and Anantharamaiah, G.M. 2002. Experimental and computational studies of the interactions of amphipathic peptides with lipid surfaces. In Current topics in membranes (eds. S.A. Simon and T.J. McIntosh), p. 330. Academic Press, New York.

- Serpell, L.C., Berriman, J., Jakes, R., Goedert, M., and Crowther, R.A. 2000. Fiber diffraction of synthetic α-synuclein filaments shows amyloid-like cross-β conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97 4897–4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini, M.G., Schmidt, M.L., Lee, V.M., Trojanowski, J.Q., Jakes, R., and Goedert, M. 1997. α-Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388 839–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini, M.G., Crowther, R.A., Jakes, R., Hasegawa, M., and Goedert, M. 1998. α-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with lewy bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95 6469–6473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmer, T.S., Bax, A., Cole, N.B., and Nussbaum, R.L. 2004. Structure and dynamics of micelle-bound human α-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. http://www.jbc.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Weinreb, P.H., Zhen, W., Poon, A.W., Conway, K.A., and Lansbury Jr., P.T. 1996. NACP, a protein implicated in Alzheimer’s disease and learning, is natively unfolded. Biochemistry 35 13709–13715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wersinger, C. and Sidhu, A. 2003. Attenuation of dopamine transporter activity by α-synuclein. Neurosci. Lett. 340 189–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wersinger, C., Prou, D., Vernier, P., Niznik, H.B., and Sidhu, A. 2003. Mutations in the lipid-binding domain of α-synuclein confer overlapping, yet distinct, functional properties in the regulation of dopamine transporter activity. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 24 91–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D.S., Bigam, C.G., Holm, A., Hodges, R.S., and Sykes, B.D. 1995. 1H, 13C and 15N random coil NMR chemical shifts of the common amino acids. I. Investigations of nearest-neighbor effects. J. Biomol. NMR 5 67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, N.E., Zhu, B.Y., Sykes, B.D., and Hodges, R.S. 1992. Relationship between amide proton chemical shifts and hydrogen bonding in amphipathic α-helical peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114 4320–4326. [Google Scholar]