Abstract

Pab1 is the major poly(A)-binding protein in yeast. It is a multifunctional protein that mediates many cellular functions associated with the 3′-poly(A)-tail of messenger RNAs. Here, we characterize Pab1 as an export cargo of the protein export factor Xpo1/Crm1. Pab1 is a major Xpo1/Crm1-interacting protein in yeast extracts and binds directly to Xpo1/Crm1 in a RanGTP-dependent manner. Pab1 shuttles rapidly between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and partially accumulates in the nucleus when the function of Xpo1/Crm1 is inhibited. However, Pab1 can also be exported by an alternative pathway, which is dependent on the MEX67-mRNA export pathway. Import of Pab1 is mediated by the import receptor Kap108/Sxm1 through a nuclear localization signal in its fourth RNA-binding domain. Interestingly, inhibition of Pab1’s nuclear import causes a kinetic delay in the export of mRNA. Furthermore, the inviability of a pab1 deletion strain is suppressed by a mutation in the 5′–3′ exoribonuclease RRP6, a component of the nuclear exosome. Therefore, nuclear Pab1 may be required for efficient mRNA export and may function in the quality control of mRNA in the nucleus.

Keywords: mRNA transport, mRNA maturation, poly(A)-tail, nuclear import, nuclear export

INTRODUCTION

In all eukaryotes, continuous exchange of proteins and nucleic acids between the nucleus and the cytoplasm is achieved through parallel, active transport pathways across the nuclear envelope. Nucleocytoplasmic transport occurs through the nuclear pore complex (NPC), a large multiprotein structure, which spans the two layers of the nuclear envelope. Most protein and RNA cargoes are transported across the NPC with the help of soluble receptors, which shuttle continuously between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and undergo regulated cargo binding and release cycles in the two compartments (Mattaj and Englmeier 1998; Görlich and Kutay 1999; Macara 2001; Weis 2003).

A large variety of nucleocytoplasmic transport pathways are mediated by members of the importin-β/karyopherin family of transport receptors. This protein family consists of 14 members in budding yeast, and more than 20 members of this family have been identified in metazoans (Görlich and Kutay 1999; Ström and Weis 2001). Based on the direction of cargo transport, the importin-β/karyopherin family can be further subdivided into importins, which carry substrates into the nucleus, and exportins, which transport substrates out of the nucleus. A critical regulatory event in the cycling of importins and exportins between the nucleus and the cytoplasm is the compartment-specific binding and release of cargo, which is coordinated by the small GTPase Ran. Ran switches between a GDP- and a GTP-bound form, but the two nucleotide states are asymmetrically distributed, with Ran-GTP being highly enriched in the nucleus. This nucleocytoplasmic gradient of RanGTP is established through a spatial separation of the regulators of the Ran cycle. Whereas the Ran guanine nucleotide exchange factor, RCC1, is localized to the nucleus, the RanGTPase-activating protein, RanGAP, is almost exclusively found in the cytoplasm (Mattaj and Englmeier 1998; Görlich and Kutay 1999; Macara 2001; Lei and Silver 2002; Weis 2003). In the nucleus, RanGTP induces the release of cargoes from importins and promotes the binding of substrates to exportins, thus providing positional information to nuclear transport processes (Mattaj and Englmeier 1998; Görlich and Kutay 1999; Macara 2001; Lei and Silver 2002; Weis 2003).

The most extensively studied exportin of the importin-β family is the protein export factor Crm1 (also called Xpo1 in yeast). Xpo1/Crm1 is the receptor for proteins containing leucine-rich nuclear export signals (NES) and directly binds to NES-containing substrates in the presence of RanGTP (Fornerod et al. 1997; Stade et al. 1997; Askjaer et al. 1999; Paraskeva et al. 1999; Maurer et al. 2001). However, the affinity of Xpo1/Crm1 for cargo is generally low (Askjaer et al. 1999; Paraskeva et al. 1999; Maurer et al. 2001), and additional cofactors, such as the RanGTP-binding protein RanBP3, appear to be required to stabilize the interaction between Xpo1/Crm1 and NES substrates (Englmeier et al. 2001; Lindsay et al. 2001). Upon complex formation in the nucleus, Xpo1/Crm1, together with its cargo, translocates across the NPC. In the cytoplasm, the export complex is disassembled through the combined effort of RanBP1 (Yrb1 in yeast) and RanGAP (Rna1 in yeast). GTP hydrolysis by Ran completes the export reaction, and both RanGDP and the empty Xpo1/Crm1 receptor re-enter the nucleus to undergo further rounds of transport (for review, see Mattaj and Englmeier 1998; Görlich and Kutay 1999; Macara 2001; Lei and Silver 2002; Weis 2002, 2003).

Leucine-rich NESs, originally identified in the protein kinase A inhibitor (PKI) and in HIV Rev (Fischer et al. 1995; Wen et al. 1995), have been characterized in numerous proteins, and Xpo1/Crm1 has been implicated in the export of a large variety of substrates out of the nucleus (for review, see Ström and Weis 2001). In metazoans, the characterization of the Xpo1/Crm1 export pathway has been greatly facilitated by the drug leptomycin B (LMB), which specifically binds to and inhibits Xpo1/Crm1 (Fornerod et al. 1997; Fukuda et al. 1997; Kudo et al. 1998). In yeast, mislocalization data in xpo1/crm1 mutant strains have been used to implicate Xpo1/Crm1 in the export of many substrates, including transcription factors (e.g., Yap1 [Yan et al. 1998] and Ace1 [Jensen et al. 2000]), kinases (e.g., Hog1 [Ferrigno et al. 1998]), ribosomal RNA (Moy and Silver 1999; Ho et al. 2000; Stage-Zimmermann et al. 2000; Gadal et al. 2001), SRP RNA (Ciufo and Brown 2000; Grosshans et al. 2001), or mRNA (Stade et al. 1997; but see also Neville et al. 1997). However, in only a few cases was biochemical evidence for a direct interaction between Xpo1/Crm1 and these potential cargoes provided.

Here, we identify the poly(A)-binding protein Pab1 as an export substrate of Xpo1/Crm1 in yeast. Pab1 is an essential, highly conserved protein that binds with high affinity to the poly(A) tail at the 3′-end of mRNAs (Adam et al. 1986; Sachs et al. 1986). Pab1 is a multifunctional protein and appears to be an important mediator of the multiple roles of the poly(A) tail in mRNA biogenesis, stability, and translation (for review, see Caponigro and Parker 1996; Sachs et al. 1997; Zhao et al. 1999). At steady state, Pab1 is found in the cytoplasm of yeast cells; however, it was shown to copurify and interact with the nuclear cleavage factor IA (CF IA), which is required for both mRNA cleavage and polyadenylation (Amrani et al. 1997; Minvielle-Sebastia et al. 1997). Furthermore, Pab1 affects poly(A) tail length regulation in vitro (Amrani et al. 1997; Minvielle-Sebastia et al. 1997; Brown and Sachs 1998) and in vivo (Sachs and Davis 1989; Caponigro and Parker 1995; Brown and Sachs 1998). In the cytoplasm, Pab1 affects both mRNA decay and translation (for review, see Caponigro and Parker 1996; Sachs et al. 1997; Sachs and Varani 2000). The stimulatory effects on translation are mainly mediated through the interaction of Pab1 with the translation initiation factor eIF4G, a subunit of the cap-binding complex eIF4F (Tarun and Sachs 1996; Kessler and Sachs 1998). This contact between the 5′-end and 3′-end of the mRNA leads to the formation of a circular message (Wells et al. 1998) and appears to be critical for the synergistic effects of the cap and the poly(A) tail in translation (for review, see Sachs et al. 1997; Sachs and Varani 2000).

In this study, we show that the localization of Pab1 is highly dynamic and that Pab1 rapidly shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Pab1 can be exported from the nucleus through at least two distinct pathways: one pathway is dependent on XPO1/CRM1, whereas the second pathway requires MEX67 and/or ongoing mRNA export. Pab1 directly binds to Xpo1/Crm1 through an NES located at the amino terminus of Pab1. Import of Pab1 is mediated by the importin Sxm1/Kap108, which binds to Pab1 through a nuclear localization signal in its fourth RNA-binding domain (RRM4). We discuss the function of Pab1 in the nucleus and provide evidence that Pab1 is required for the efficient export of mRNA out of the nucleus.

RESULTS

Pab1 is a major Xpo1/Crm1-interacting protein

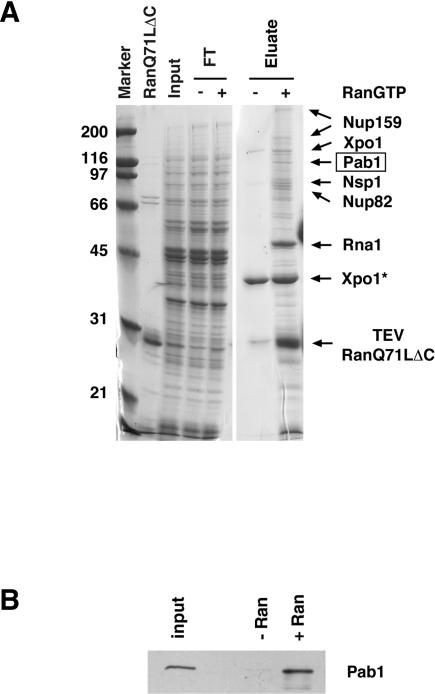

The protein export factor Xpo1/Crm1 has been implicated in a large number of export pathways, but a direct biochemical interaction between Xpo1/Crm1 and putative cargoes has been demonstrated in only few cases (for review, see Ström and Weis 2001). Our previous attempts to purify cargoes of Xpo1/Crm1 from yeast extracts in the presence of the hydrolysis-deficient mutant Gsp1Q71L (RanQ71L) have led to the characterization of the yeast Ran-binding protein Yrb1 (Maurer et al. 2001). Yrb1 shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm but functions as a disassembly factor for Xpo1/Crm1–RanGTP–cargo complexes in the cytoplasm (Bischoff and Gorlich 1997; Kunzler et al. 2000; Maurer et al. 2001). To prevent Yrb1-induced complex disassembly and formation of stable Xpo1/Crm1–Gsp1Q71LGTP–Yrb1 complexes in the extracts, we took advantage of a Ran mutant, which lacks its very carboxyl terminus required for the interaction with Yrb1 (Gsp1Q71LΔC) (Maurer et al. 2001). A functional Xpo1-S-TEV-ZZ fusion protein was generated (see Materials and Methods) and affinity-purified from yeast extracts either in the presence or absence of recombinant Gsp1Q71LΔC, which had been preloaded with GTP. Interacting proteins were eluted from immobilized Xpo1/Crm1 after the second round of affinity purification and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and by mass spectrometry (Fig. 1A; data not shown). In addition to Gsp1Q71LΔC and Xpo1/Crm1 itself, we unambiguously identified the nucleoporins Nup159, Nsp1, and Nup82; the RanGAP, Rna1; and the poly (A)-binding protein, Pab1, as the major Xpo1/Crm1-binding proteins in yeast extracts under these conditions (Fig. 1A). The inter-action between Xpo1/Crm1 and Pab1, Rna1 and the three nucleoporins was greatly enhanced in the presence of Gsp1Q71LΔC-GTP (compare eluates in the presence or absence of Gsp1Q71LΔC-GTP).

FIGURE 1.

(A) Purification of Xpo1/Crm1-interacting proteins. S-TEV-ZZ-tagged Xpo1/Crm1 was tandem affinity-purified from yeast extracts (as described in Materials and Methods) either in the absence or presence of 10 μM Gsp1Q71LΔC preloaded with GTP. Proteins that interacted with immobilized Xpo1/Crm1 were eluted with 1 M MgCl2, and the input, flowthrough (FT), and eluate were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Proteins were identified by MALDI mass spectrometry. Xpo1* corresponds to a degradation product of Xpo1/Crm1. Gsp1Q71LΔC and TEV comigrated and could not be separated on this gel. Molecular mass is given in kilodaltons (kDa). (B) Binding of Pab1 to Xpo1/Crm1 is dependent on the presence of RanGTP. Eluates from protein S beads were analyzed by Western blot using the anti-Pab1 monoclonal antibody 1G1 (Anderson et al. 1993). Based on serial dilutions using recombinant Pab1, we estimate that Pab1 is ~200-fold enriched in purifications performed in the presence of Gsp1Q71LΔC (+Ran) compared to purifications without the addition of Gsp1Q71LΔC (−Ran).

Pab1 is an extremely abundant protein (Adam et al. 1986; Sachs et al. 1986). To analyze further the specificity of the Xpo1/Crm1–Pab1 interaction, we performed Western blot analyses with eluates of the affinity purification using the monoclonal antibody 1G1 (Fig. 1B), which is monospecific for Pab1 (Anderson et al. 1993). Quantitative analysis of these results showed that Pab1 was ~200-fold enriched in purifications performed in the presence of Gsp1Q71LΔC when compared to purifications without the addition of Gsp1Q71LΔC, demonstrating that the binding of Pab1 to Xpo1/Crm1 in yeast extracts is specific and dependent on the presence of RanGTP.

Pab1 shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm

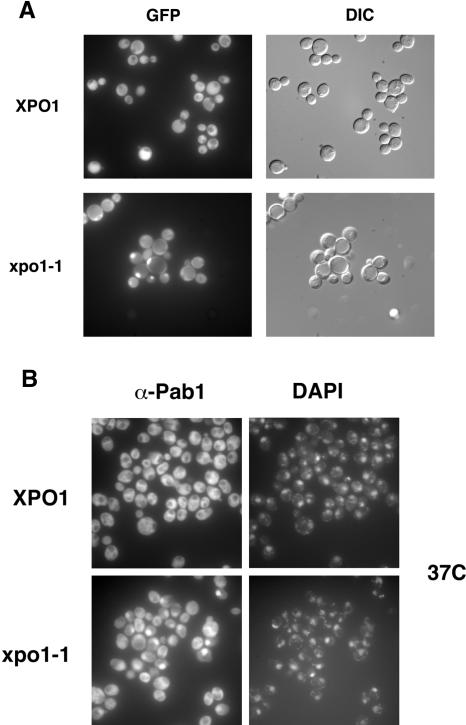

In wild-type cells, Pab1 is located in the cytoplasm and at steady state is excluded from nuclei (Fig. 2). To test whether Pab1 shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm in an XPO1/CRM1-dependent manner, the subcellular localization of Pab1 was analyzed in temperature-sensitive xpo1-1 cells, which are defective for NES-mediated protein export at the nonpermissive temperature (Stade et al. 1997). PAB1 was replaced by a functional PAB1-GFP fusion, and the localization of Pab1-GFP was examined by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2A). After ~20 min at the nonpermissive temperature, Pab1 began to accumulate in nuclei of xpo1-1 cells. However, the mislocalization was not complete, and Pab1 was nuclear in a maximum of 40% of the cells in the population. This ratio did not significantly increase with prolonged incubations at 37°C (data not shown). Identical results were obtained when the distribution of Pab1 was examined by immunofluorescence in XPO1 and xpo1-1 cells using the anti-Pab1 monoclonal antibody 1G1 (Fig. 2B). Similarly, Pab1-GFP accumulated only in a subset of nuclei in the leptomycin B (LMB)-sensitive XPO1/CRM1 allele, crm1-T539C (Neville and Rosbash 1999), upon treatment with LMB (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Pab1 mislocalizes to the nucleus in xpo1-1 cells. (A) Wild-type and xpo1-1 cells expressing functional Pab1-GFP were grown at room temperature and then shifted to 37°C for 40 min. The localization of Pab1-GFP was analyzed by epifluorescence (GFP), and yeast cells were visualized by Nomarski microscopy (DIC). (B) Wild-type and xpo1-1 cells were shifted to 37°C for 40 min, fixed, prepared for immunofluorescence, and analyzed with the anti-Pab1 monoclonal antibody 1G1 (α-Pab1). Nuclear DNA was stained with DAPI, and the signal was visualized by epifluorescence.

The partial mislocalization of Pab1 in xpo1-1 cells suggests that additional or redundant export pathways may exist for Pab1 and/or that Pab1’s import is regulated during the cell cycle. To distinguish between these possibilities, the shuttling of Pab1 was examined in xpo1-1 cells that had been synchronized with α-factor and then shifted to the restrictive temperature at various cell cycle stages. No cell-cycle-dependent change of Pab1’s nuclear localization could be observed in these experiments (data not shown).

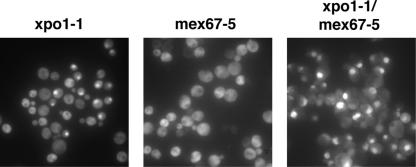

Since Pab1 interacts with poly(A) RNA, we wanted to test whether ongoing mRNA transport is responsible for the partial export of Pab1 in xpo1-1 cells by constructing an xpo1-1 mex67-5 double mutant. Interestingly, xpo1-1 mex67-5 cells are viable, but they display a synthetic growth phenotype and are unable to grow at temperatures higher than 30°C (data not shown). The export defect of Pab1 is greatly exacerbated in the xpo1-1 mex67-5 strain, and Pab1 is nuclear in basically all cells incubated at the nonpermissive temperature (Fig. 3). Therefore, Pab1 can also be exported to the cytoplasm via the MEX67/mRNA export pathway in the absence of XPO1/CRM1 function. Interestingly, Pab1 did not accumulate in nuclei of mex67-5 cells alone (Fig. 3). This suggests that Xpo1 is sufficient to export Pab1 to the cytoplasm when mRNA export is compromised. Furthermore, these results demonstrate that the partial nuclear accumulation of Pab1 in xpo1-1 cells is not an indirect consequence of the mislocalization of poly(A) RNA, which can be observed in this strain.

FIGURE 3.

Pab1 can be exported by two distinct pathways. xpo1-1-expressing Pab1-GFP, mex67-5, and xpo1-1 mex67-5 cells were grown in full medium at room temperature and then shifted to 37°C for 1 h. The localization of Pab in xpo1-1 cells was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. The localization of Pab1 in mex67-5 and in xpo1-1 mex67-5 mutant cells was examined by immunofluorescence.

Taken together, the localization experiments suggest that Pab1 can be exported from the nucleus via at least two distinct pathways: whereas the main export pathway is dependent on XPO1/CRM1, the second route requires MEX67 and/or ongoing mRNA export.

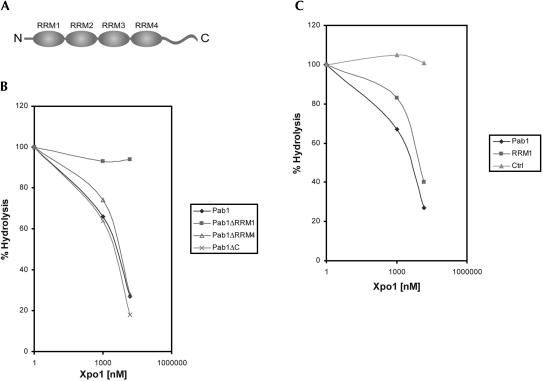

Pab1 binds directly to Xpo1/Crm1

To test whether Pab1 directly binds to Xpo1/Crm1 in vitro, RanGAP protection assays (Görlich et al. 1996; Bischoff and Gorlich 1997; Maurer et al. 2001) were performed (Fig. 4). This assay takes advantage of the observation that RanGTP is protected against RanGAP-stimulated GTP hydrolysis in trimeric exportin–cargo–RanGTP complexes. Therefore, a concentration-dependent inhibition of RanGTP hydrolysis can be used to measure the stability of preformed Xpo1/ Crm1–cargo–RanGTP complexes. Recombinant Pab1, Gsp1-GTP (yeast Ran-GTP), and Xpo1/Crm1 were incubated for 20 min; Rna1 (yeast RanGAP) was added; and the amount of GTP hydrolysis was measured after 2 min. Pab1 inhibited GTP hydrolysis by Gsp1 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). No protection of Gsp1-GTP was observed in the absence of Xpo1/Crm1 (data not shown), demonstrating the formation of a direct complex between Pab1, Xpo1/Crm1, and Gsp1-GTP. The estimated dissociation constant of the trimeric Xpo1/Pab1/Gsp1GTP complex is in the low micromolar range (estimated Kd ~ 2 μM), similar to what has been previously measured for other Xpo1–cargo complexes in yeast (Maurer et al. 2001).

FIGURE 4.

(A) Schematic representation of the domain organization of Pab1. (B) Pab1 binds directly to Xpo1/Crm1. Gsp1 [γ-32P]GTP (80 nM) was incubated with the indicated concentrations of recombinant Xpo1/Crm1 and 15 μM recombinant Pab1 wild-type (Pab1), Pab1 lacking RRM1 (Pab1ΔRRM1), Pab1 lacking RRM4 (Pab1ΔRRM4), or Pab1 lacking the carboxyl terminus (Pab1ΔC) for 15 min on ice. Gsp1 GTPase reactions were started by the addition of 40 nM Rna1, and the amount of hydrolysis was determined by measuring the release of [32P]phosphate using the charcoal method after 2 min. (C) GTPase hydrolysis assays were performed as described in B using 80 nM Gsp1 [γ-32P]GTP and increasing concentrations of Xpo1/Crm1 in the presence of 15 μM either recombinant wild-type Pab1 (Pab1), the RRM1 domain of Pab1 comprising amino acids 15–129 (RRM1), or BSA (Ctrl).

We next attempted to identify the Xpo1-interaction domain in Pab1. The domain structure of Pab1 is comprised of four RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) each consisting of ~90 amino acids, and a less well-conserved carboxy-terminal region (Fig. 4A). Deletion constructs lacking RRM1 (Pab1ΔRRM1), RRM2 (Pab1ΔRRM2), RRM4 (Pab1ΔRRM4), and the carboxy-terminal region (Pab1ΔC); or RRM3, RRM4, and the carboxy-terminal region (Pab1ΔRRM3,4,C) were expressed in Escherichia coli and used in the RanGAP protection assay (Fig. 4B; data not shown). Deletion of RRM2, RRM3, RRM4, or of the carboxy-terminal domain had no or only minor effects on complex formation; however, deletion of RRM1 completely abrogated the interaction with Xpo1/Crm1 (Fig. 4B; data not shown).

Having established that amino acids 9–124 of Pab1 containing RRM1 are necessary for the binding of Pab1 to Xpo1/Crm1, we next wanted to test whether this domain is also sufficient for the interaction. The amino-terminal RRM1 domain was purified from E. coli and incubated together with Xpo1/Crm1 and radiolabeled Gsp1GTP, and GTP hydrolysis was measured upon addition of Rna1. The RRM1 domain was able to protect RanGTP against Ran-GAP-induced hydrolysis comparable to full-length Pab1 (Fig. 4C), and the protection was dependent on the presence of Xpo1/Crm1. We therefore conclude that the amino-terminal RRM1 domain, comprising amino acids 9–124 of Pab1, is both necessary and sufficient to mediate the direct interaction between Pab1 and Xpo1.

Pab1 contains an NES in its amino terminus

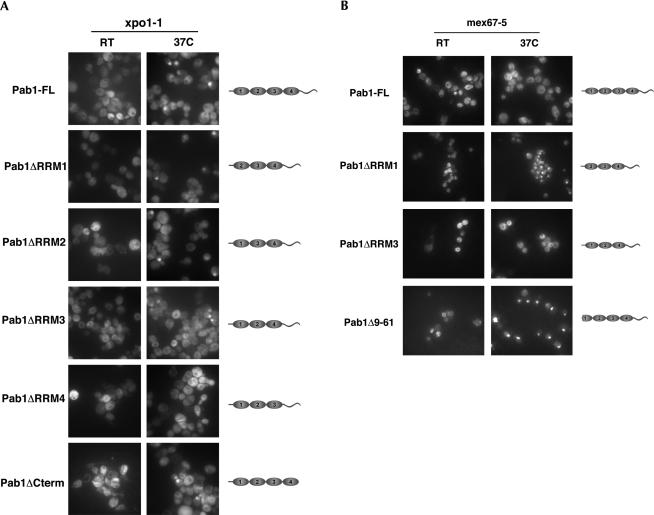

With the identification of the amino terminus of Pab1 as being required for binding to Xpo1/Crm1, it was important to determine whether this domain is necessary for the export of Pab1 out of the nucleus. As previously described, pab1 mutants lacking individual RRMs are viable (Sachs et al. 1987; Kessler and Sachs 1998). We therefore constructed XPO1 and xpo1-1 strains, in which PAB1 was replaced by pab1 mutants lacking either RRM1 (pab1ΔRRM1), RRM2 (pab1ΔRRM2), RRM3 (pab1ΔRRM3), and RRM4 (pab1ΔRRM4) or the carboxy-terminal domain (pab1ΔC), and analyzed the intracellular localization of the different Pab1 variants by immunofluorescence using a monospecific polyclonal anti-Pab antiserum (Fig. 5; data not shown). As expected from the in vitro binding studies, Pab1ΔRRM2, Pab1ΔRRM3, and Pab1ΔC were cytoplasmic at steady state in wild-type cells but accumulated in up to 40% of the nuclei of xpo1-1 cells at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 5A). Of note, Pab1ΔRRM4 remained cytoplasmic in xpo1-1 cells, indicating that RRM4 is required for the import of Pab1 (see below).

FIGURE 5.

(A) xpo1-1 cells expressing full-length Pab1 (Pab1-FL), Pab1ΔRRM1, Pab1ΔRRM2, Pab1ΔRRM3, Pab1ΔRRM4, or Pab1ΔCterm were grown at room temperature (RT) or shifted to 37°C for 1 h, and the localization of the various Pab1 variants was analyzed by immunofluorescence using an anti-Pab1 polyclonal serum. (B) Wild-type and mex67-5 cells expressing either Pab1 wild-type, Pab1ΔRRM1, Pab1ΔRRM3, or a Pab1 mutant lacking amino acids 9–61 (Pab1Δ9–61) were grown at room temperature or shifted to 37°C for 1 h. The localization of Pab1 was visualized by immunofluorescence using a monospecific anti-Pab1 polyclonal serum.

Surprisingly, Pab1ΔRRM1, which is unable to bind to Xpo1/Crm1 in vitro, did not accumulate in the nucleus of wild-type cells, suggesting that the MEX67/mRNA export pathway is dominant under these conditions. We therefore analyzed the localization of various Pab1 truncations also in mex67-5 cells. Whereas Pab1 wild-type, Pab1ΔRRM2, Pab1ΔRRM3, Pab1ΔRRM4, or Pab1ΔC remained cytoplasmic in mex67-5 cells grown at the restrictive temperature, the Pab1ΔRRM1 truncation strongly accumulated in nuclei of these cells (Fig. 5B; data not shown), confirming that XPO1 and MEX67 have redundant functions in the export of Pab1.

Two potential hydrophobic nuclear export sequences located between amino acids 12 and 17 and between amino acids 64 and 69 can be identified in the amino-terminal domain, which is deleted in the Pab1ΔRRM1 mutant used here. To determine if either of these motifs is necessary for the export of Pab1 in mex67-5 cells, additional truncation mutants of Pab1 were constructed, and their subcellular localization was examined by immunofluorescence (Fig. 5B; data not shown). The minimal domain that is required for the export of Pab1 in mex67-5 cells was found to be between amino acids 9 and 61. This is consistent with the conclusion that the Xpo1-dependent export signal of Pab1 is located in the leucine-rich motif found between amino acids 12 and 17.

Pab1 is imported by Kap108/Sxm1

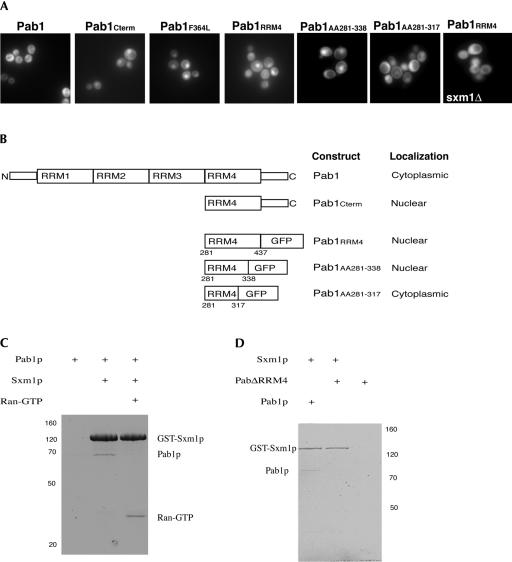

The fact that Pab1ΔRRM4 did not localize to the nucleus in xpo1-1 cells at the nonpermissive temperature suggested that the RRM4 domain is critical for the nuclear import of Pab1. To directly test whether the RRM4 of Pab1 contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS), we generated a fusion between GFP and the RRM4 domain and analyzed its sub-cellular localization. The RRM4-GFP fusion protein strongly accumulated inside nuclei in wild-type cells (Fig. 6A), establishing that the RRM4 domain is not only necessary but also sufficient for the nuclear localization of Pab1. To more precisely map the NLS in RRM4, additional truncations were generated and examined for their localization when fused to GFP (Fig. 6A,B). The shortest sequence that was still efficiently imported into nuclei comprised amino acids 281–338 of Pab1, whereas a GFP fusion with residues 281–317 remained cytoplasmic, indicating that the region containing amino acids 317–338 is critical for the function of the Pab1 NLS (Fig. 6A,B).

FIGURE 6.

(A) The localization of Pab1-GFP, a Pab1 truncation expressing RRM4 and the carboxyl terminus fused to GFP (Pab1Cterm), the Pab1 truncation mutant Pab1F364L (Sachs et al. 1987) fused to GFP, RRM4Pab1-GFP, amino acids 281–338 of Pab1 fused to GFP, and amino acids 281–317 of Pab1 fused to GFP were analyzed by fluorescence in wild-type cells. RRM4Pab1-GFP is no longer localized to the nucleus when expressed in kap108/sxm1 deletion cells. (B) Schematic diagram of the analyzed Pab1 truncation mutants and their subcellular localization. (C) Pab1 binds to Kap108/Sxm1 in vitro. Recombinant Sxm1-GST was incubated with Pab1 either in the absence or presence of RanGTP, and complexes were purified on glutathione beads and analyzed by SDS gel electrophoresis (lanes 2 and 3). Pab1 alone does not bind to glutathione beads (lane 1). (D) The interaction between Pab1 and Kap108/Sxm1 requires RRM4. Recombinant Sxm1-GST was incubated with full-length Pab1 and/or Pab1ΔRRM4. Complexes were purified on glutathione beads and analyzed by SDS gel electrophoresis.

The putative NLS of Pab1 between amino acids 281 and 338 does not contain an obvious classical NLS motif. It was thus important to determine how Pab1 is imported into the nucleus. The RRM4-GFP fusion was expressed in a panel of mutants of known nuclear import receptors, including deletion or temperature-sensitive alleles of KAP95, KAP104, KAP108, KAP111, KAP114, KAP119, KAP121, KAP122, and KAP123. RRM4-GFP was nuclear in all strains except for kap108Δ cells, indicating that Kap108/Sxm1 is the importin for Pab1 (Fig. 6A; data not shown). To determine whether Kap108/Sxm1 interacts with Pab1, Kap108/Sxm1, and Pab1 were expressed in E. coli, purified, and analyzed in pull-down experiments in vitro. We found that Pab1 bound to Kap108/Sxm1 (Fig. 6C). Although the interaction between Pab1 and Kap108/Sxm1 was weak, it was specific as Kap108/Sxm1 did not bind to Pab1ΔRRM4 (Fig. 6D) and the interaction between full-length Pab1 and Kap108/Sxm1 was abolished in the presence of RanGTP (Fig. 6C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the interaction between Pab1 and Kap108/Sxm1 is direct, is regulated by RanGTP, and is dependent on the RRM4 domain and thus provide strong evidence that Kap108/Sxm1 is the nuclear import receptor of Pab1.

Nuclear Pab1 is required for efficient mRNA export

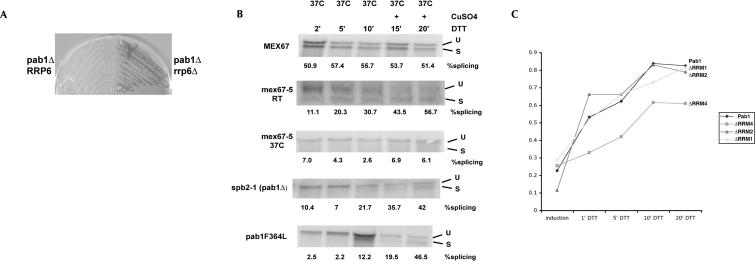

Our experiments established that the localization of Pab1 is highly dynamic and that Pab1 shuttles between the cytoplasm and the nucleus. In contrast to its well-studied role in the cytoplasm, very little is known about the nuclear function(s) of Pab1. Pab1 was previously shown to interact with components of the polyadenylation machinery and to affect polyadenylation in vitro and in vivo (Sachs and Davis 1989; Caponigro and Parker 1995; Amrani et al. 1997; Minvielle-Sebastia et al. 1997; Brown and Sachs 1998). Since the export of Pab1 is dependent on XPO1/CRM1 and MEX67, we wanted to examine whether Pab1 plays a role in mRNA export. Oligo(dT) in situ hybridization experiments were performed in the pab1 deletion strain sbp2-1, which is viable because of an extragenic suppressor mutation in the RPL39 gene (Sachs and Davis 1990). No significant accumulation of poly(A) RNA could be detected in this strain (data not shown). However, in the course of our experiments, we noticed that sbp2-1 cells (pab1Δrpl39-1) show a significant reduction in overall mRNA levels compared to wild-type or rpl39 mutant cells (data not shown). This observation prompted us to test for genetic interactions between PAB1 and RRP6, a component of the nuclear exo-some involved in rRNA and mRNA maturation (Mitchell et al. 1997; Bousquet-Antonelli et al. 2000; Hilleren et al. 2001). A genomic disruption of RRP6 was created in a pab1-deletion strain, which was covered by an URA3-marked plasmid expressing PAB1. Upon counterselection on plates containing 5-fluoro-orotic acid (5-FOA), viable colonies were obtained in the rrp6Δ background but not in cells expressing wild-type RRP6 (Fig. 7A). This demonstrates that the lethality associated with a pab1 deletion can be suppressed by deleting rrp6 and that rrp6Δ is a bypass suppressor of pab1Δ. Interestingly, the reduction of mRNA levels observed in sbp2-1 appears to be suppressed in the pab1Δrrp6Δ double-deletion cells (data not shown), suggesting that one essential function of Pab1 is to protect mRNAs against 3′–5′ exonucleolytic degradation in the nucleus.

FIGURE 7.

(A) Deletion of pab1 is rescued by a deletion of rrp6. RRP6 was deleted in pab1Δ cells covered by a URA3-marked plasmid expressing Pab1. After growth on media containing 5-fluoro-orotic acid (5-FOA), viable colonies are obtained in the rrp6-deletion background but not in cells that are wild type for RRP6. (B,C) Pab1 mutants are deficient for Hac1 mRNA export. Hac1 expression was induced by the addition of copper in the presence of DTT in MEX67, mex67-5, pab1ΔRRM1, spb2-1 (pab1Δ rpl39-1), or in pab1F364L cells (B) and in PAB1, pab1ΔRRM1, pab1ΔRRM2, and in pab1ΔRRM4 cells (C). Samples were collected at the indicated time points, and the kinetics of Hac1 mRNA splicing was monitored by Northern blot analysis. Percent splicing indicates the ratio between the unspliced (U) and the spliced (S) isoform of Hac1 as quantified by PhosphorImager analysis.

Since the oligo(dT) approach relies on the nuclear accumulation of poly(A) RNA, we sought to analyze mRNA export in pab1 mutants by an alternative method. The message for Hac1, a transcription factor important for the unfolded protein response pathway (UPR) (for review, see Patil and Walter 2001), undergoes an unconventional splicing event and is cleaved by the ER-associated endonuclease Ire1 in the cytoplasm (Ruegsegger et al. 2001). Since spliced and unspliced Hac1 mRNA can be easily differentiated by Northern blot analysis, the appearance of the spliced isoform provides a convenient assay to monitor the arrival of Hac1 mRNA in the cytoplasm and thus should be a measure for the kinetics of mRNA export. To establish this assay, we integrated a copper-inducible HAC1 construct into the mRNA export-deficient mex67-5 strain and the corresponding wild-type control. Hac1 mRNA was transcriptionally induced by the addition of copper, and the UPR was activated by the addition of DTT. Samples were collected at various time points after induction and analyzed by Northern blot to measure the extent of Hac1 splicing (Fig. 7B). In wild-type cells, maximum levels of splicing (~50% at 37°C) were reached ~2 min after DTT addition and induction of transcription with copper. In contrast, no splicing of Hac1 mRNA could be observed in mex67-5 cells when mRNA export is inhibited, confirming that Hac1 splicing occurs in the cytoplasm. Identical results were obtained in the mRNA export-deficient nup159-1 strain at the restrictive temperature (data not shown). Intriguingly, the appearance of the spliced isoform was significantly delayed in mex67-5 cells grown at the permissive temperature (Fig. 7B), demonstrating the high sensitivity of the HAC1 export assay since such a delay in export cannot be readily observed with the oligo(dT) assay at the permissive temperature of this mutant.

Having established that this assay can be used to monitor mRNA export, we next examined the kinetics of Hac1 splicing in various pab1 mutant strains (Fig. 7C). A significant kinetic delay of Hac1 splicing was seen in the pab deletion mutant sbp2-1 (pab1Δ rpl39-1) and in pab1-F364L cells (which expresses only the carboxy-terminal moiety of Pab1) (see Fig. 6A) when compared to the isogenic wild-type control (Fig. 7B) or rpl39 deletion cells, which expressed functional Pab1 (data not shown).

The deletion of PAB1 and the pab1-F364L allele have severe effects on translation and on polysome formation (Sachs et al. 1987; Deardorff and Sachs 1997; Kessler and Sachs 1998). Since Hac1 splicing occurs on polysomes (Ruegsegger et al. 2001), it was critical to analyze more specific pab1 alleles that affect nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Pab1. Of specific interest were the export-deficient pab1ΔRRM1 and the import-deficient pab1ΔRRM4 alleles. Notably, both these mutants are fully functional in eIF4G and poly(A) binding and have no significant effects on translation or polysome formation (Kessler and Sachs 1998; data not shown). As a control we also included the pab1ΔRRM2 allele, which lacks the eIF4G-binding domain and is severely compromised in poly(A)-stimulated translation (Kessler and Sachs 1998). No delay in the kinetics of Hac1 splicing could be observed in wild-type cells and in cells expressing either Pab1ΔRRM2 or Pab1ΔRRM1 lacking the Xpo1/Crm1-interaction domain. This indicates that efficient translation and the binding of Pab1 to Xpo1/Crm1 is not required for Hac1 export and splicing. In contrast, a reproducible and significant delay was observed in the constitutively cytoplasmic pab1ΔRRM4 allele (Fig. 7C). This result suggests that the presence of Pab1 in the nucleus is required for the efficient export of Hac1 mRNA to the cytoplasm.

DISCUSSION

Pab1 is an export cargo of Xpo1/Crm1 and shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm

In this study, we have identified the poly(A)-binding protein Pab1 as a substrate for the export receptor Xpo1/Crm1 in budding yeast. Pab1 mislocalizes to the nucleus of cells deficient for Xpo1/Crm1 function and directly binds to Xpo1/Crm1 in a RanGTP-dependent manner. The affinity of recombinant Pab1 for Xpo1/Crm1 is rather low in vitro (estimated Kd ~2 μM). However, Pab1 is an extremely abundant protein (Adam et al. 1986; Sachs et al. 1986), and similar low affinities have been previously measured for other NES-Xpo1/Crm1 complexes (Askjaer et al. 1999; Paraskeva et al. 1999; Maurer et al. 2001). Although the binding of Pab1 to Xpo1/Crm1 in yeast extracts does not depend on RNA as the addition of RNases to purified complexes does not abolish the interaction between these proteins (data not shown), it will be interesting to determine whether poly(A) RNA or additional cofactors such Yrb2 (yeast RanBP3) can strengthen the interaction between Pab1 and Xpo1 in vitro and in vivo.

Pab1 does not mislocalize in every cell upon inactivation of Xpo1/Crm1 and can be exported by at least one additional pathway. This alternative pathway appears to be dependent on mRNA export as Pab1 completely accumulates in nuclei of xpo1-1 mex67-5 double mutant cells. Only when both mRNA export (e.g., through inactivation of mex67-5) and XPO1/CRM1-dependent export are compromised (either in the context of conditional xpo1/crm1 alleles or through mutations in Pab1 that prevent interaction with Xpo1/Crm1), is Pab1 found in the nucleus of all cells in the population. The existence of two distinct export pathways, however, does not explain the stochastic behavior of Pab1, and it remains unclear why individual cells in the population respond differently to the inactivation of Xpo1/ Crm1.

We demonstrate that amino acids 9 to 124, comprising RRM1 of Pab1, are both necessary and sufficient for the RanGTP-dependent binding of recombinant Pab1 to Xpo1/ Crm1. The deletion of this domain of Pab1 also leads to the nuclear mislocalization of Pab1 in mex67-5 cells. Sequence comparisons reveal two potential hydrophobic nuclear export motifs in this region (located between amino acids 12–17 and amino acids 64–69). Based on the crystal structure of human PABP (Deo et al. 1999), the second hydrophobic motif (amino acids 64–69) is probably only partially exposed to solvent. Furthermore, mutational analyses establish that the region containing amino acids 12–17 is required for the export of Pab1 in mex67-5 cells (Fig. 5) and that two leucines at positions 12 and 15 of Pab1 are critical for the exit of Pab1 from the nucleus (Dunn et al. 2005). Although we did not directly confirm whether this short domain alone is sufficient for the interaction with Xpo1/ Crm1 in vitro, we consider it thus very likely that the leucine-rich sequence between amino acids 12 and 17 (“LENLNI”) constitutes the Xpo1/Crm1-dependent NES of Pab1.

Pab1 is imported by Kap108/Sxm1

At steady state, Pab1 is exclusively found in the cytoplasm and is excluded from nuclei. Our export inhibition experiments have revealed that Pab1’s localization is dynamic and that Pab1 rapidly shuttles in and out of the nucleus. In the cytoplasm, Pab1 is stably associated with polysomes (for review, see Sachs et al. 1997), yet upon inactivation of its two export pathways (e.g., in xpo1-1 mex67-5 double mutants), Pab1 accumulates in the nucleus of all cells in <30 min. This dynamic behavior of Pab1 appears to be conserved in evolution since previous reports demonstrated that the orthologs of Pab1 in humans (PABP) and fission yeast (spPABP) shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Afonina et al. 1998; Thakurta et al. 2002).

Pab1 contains a nuclear localization signal in a region between amino acids 281 and 338 comprising the amino terminus of the fourth RNA-binding binding domain. This region of Pab1 is not only necessary for the nuclear accumulation of Pab1, but is also sufficient to direct a GFP-fusion protein into the nucleus of wild-type cells. Import of this domain is dependent on the importin-β-family member Kap108/Sxm1. Furthermore, Pab1 directly binds to Kap108/Sxm1, and this interaction requires the RRM4 domain. These results are consistent with the conclusion that Kap108/Sxm1 serves as an importin for Pab1. Kap108/Sxm1 was originally identified as a suppressor of mutations in PSE1 and KAP123 (Seedorf and Silver 1997) and functions in the import of several RNA-binding proteins including the tRNA processing factor Lhp1 (Rosenblum et al. 1997) and several ribosomal proteins (Rosenblum et al. 1997; Sydorskyy et al. 2003). There is no obvious homology between any of these factors and the NLS domain of Pab1. Since we could not stably express the RRM4 domain of Pab1 in E. coli, we were unable to precisely map the critical residues necessary for Kap108/Sxm1 binding, but it will be now interesting to define the consensus NLS that is required to mediate import through the Kap108/Sxm1 pathway.

The nuclear function of Pab1

An interesting problem that emerges from our studies is to understand the role of Pab1 in the nucleus. Pab1 is a multifunctional protein whose cytoplasmic roles in translation and in mRNA stability have been well characterized. Previous studies have suggested that Pab1 also plays a role in mRNA 3′-end processing in the nucleus, since Pab1 interacts with subunits of the cleavage factor IA (CF IA) (Amrani et al. 1997; Minvielle-Sebastia et al. 1997) and was shown to affect poly(A) length control in vitro (Amrani et al. 1997; Minvielle-Sebastia et al. 1997; Brown and Sachs 1998) and in vivo (Sachs and Davis 1989; Caponigro and Parker 1995; Brown and Sachs 1998). Here, we show that Pab1 also affects the efficiency of mRNA export to the cytoplasm. Although none of the pab1 mutants tested in this study show a poly(A) accumulation phenotype when analyzed by oligo(dT) in situ hybridization (data not shown), we identified pab1 alleles that exhibit a significant kinetic delay in the appearance of Hac1 mRNA in the cytoplasm. Specifically, Hac1 mRNA export is affected in cells expressing Pab1ΔRRM4, which lacks the NLS and is unable to enter the nucleus, but not in cells expressing Pab1ΔRRM1 or Pab1ΔRRM2 that cannot bind to Xpo1/Crm1 or eIF4G, respectively. Since Pab1ΔRRM4 is functional in eIF4G binding and poly(A)-dependent translation (Kessler and Sachs 1998), these mutants allowed us to dissect the nuclear and cytoplasmic functions of Pab1. A role of Pab1 in mRNA export phenotype is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that certain pab1 mutants exhibit a temporal lag before mRNAs enter the mRNA decay pathway (Caponigro and Parker 1995; Morrissey et al. 1999). This observation led to the proposal that Pab1 plays a role in mRNP maturation in yeast (Caponigro and Parker 1995). Furthermore, the Sachs lab reported that the underaccumulation of mRNA, which can be observed in pab1 mutants, arises from an uncharacterized defect in nuclear mRNA metabolism independent of transcription (Morrissey et al. 1999). Recently, it was also demonstrated that overexpression of Pab1 suppresses the mRNA export defect observed in cells that do not express the hnRNP protein Nab2 (Hector et al. 2002).

What is the role of Pab1 in the nuclear export of mRNAs? Based on the interaction with Xpo1/Crm1, we could speculate that Pab1 functions as an export adaptor that mediates the interaction between certain mRNAs and Xpo1/Crm1. However, pab1 mutants that are unable to bind to Xpo1/ Crm1 do not exhibit any mRNA export phenotype, and thus the interaction between Pab1 and Xpo1/Crm1 cannot explain the mRNA export defects observed in pab1 deletion mutants or in xpo1-1 cells. Alternatively, Pab1 may affect mRNA export during 3′-end processing in a manner similar to other mutants defective in polyadenylation, which also exhibit mRNA export defects (Brodsky and Silver 2000; Hilleren et al. 2001; Hammell et al. 2002). A third possibility is that Pab1 is required for the release of mRNAs from the nucleus and/or the site of transcription and that Pab1 is part of the quality control machinery that monitors accurate mRNP assembly or export competence (Bousquet-Antonelli et al. 2000; Hilleren et al. 2001; Zenklusen et al. 2001; Libri et al. 2002; for review, see Jensen et al. 2003). It was recently shown that the nuclear exosome acts to retain transcripts at the site of transcription in mutants that are deficient in mRNA transport or in 3′-end formation (Hilleren et al. 2001; Libri et al. 2002). Interestingly, pab1 mutants have a significant reduction in overall mRNA levels (data not shown); however, no changes in the transcriptional induction of Hac1 or other messages can be observed in these cells (Morrissey et al. 1999; data not shown). This reduction of mRNA is suppressed in the absence of RRP6 (Fig. 7). Furthermore, we demonstrate here that a deletion of RRP6 acts as a bypass suppressor of pab1Δ. Since Rrp6 is a nuclear component of the exosome, these results suggest that Pab1 and the exosome play antagonistic roles in mRNP maturation and that one function of Pab1 in the nucleus is to protect mRNAs against 3′–5′-exonucleolytic degradation and/or to aid with the release of nascent transcripts from the site of transcription. Consistent with a possible function of Pab1 in the release of mRNA is the observation that SSA4 mRNA accumulates at the site of transcription in pab1 mutants in an RRP6-dependent manner (Dunn et al. 2005). We therefore propose that Pab1 is part of the nuclear mRNA quality checkpoint and that Pab1 monitors correct 3′-end formation in the nucleus, which, in turn, is required for efficient mRNA export (Brodsky and Silver 2000; Hilleren et al. 2001; Dower and Rosbash 2002; Hammell et al. 2002; Dower et al. 2004). This function of Pab1 in mRNA export may be conserved as the orthologs of Pab1 in humans (hPABP) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (spPABP) are also shuttling proteins (Afonina et al. 1998; Thakurta et al. 2002) and spPABP was shown to suppress the mRNA export defect of an rae1 nup184 mutant and to facilitate mRNA export in fission yeast (Thakurta et al. 2002).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and yeast strains

The E. coli expression construct for His6-Gsp1Q71LΔC (pKW595) was derived by PCR-mediated mutagenesis from His6-Gsp1Q71L (pKW586) (Maurer et al. 2001) and was cloned into pQE9 via SphI/HindIII. Expression constructs for Pab1-1 (BAS3059), Pab1ΔRRM1 (BAS3221), Pab1ΔRRM2 (BAS3222), Pab1ΔRRM3 (BAS3223), Pab1ΔRRM4 (BAS3224), and Pab1ΔC (BAS3225) were described in Kessler and Sachs (1998) and were kind gifts of A. Sachs. The E. coli expression plasmid for His6-RRM1 (pKW835) was generated from BAS3059 by joining blunted BamHI and SpeI sites to remove amino acids 125–577 of Pab1.

The integration cassette to genomically tag yeast proteins at their carboxyl termini with the S-TEV-ZZ affinity tag (pKW804) was created by replacing the GFP moiety of pAF6-GFP-kanMX (Longtine et al. 1998) with an AscI/PacI fragment coding for the S-TEV-ZZ tag. Yeast expression constructs for wild-type Pab1-1 (BAS3072), Pab1ΔRRM1 (BAS3227), Pab1ΔRRM2 (BAS3228), Pab1ΔRRM3 (BAS3229), Pab1ΔRRM4 (BAS3230), Pab1ΔC (BAS3231) (Kessler and Sachs 1998), and PabF364L (Sachs et al. 1987) were kindly provided by A. Sachs. To generate Pab1-GFP (pKW1162) and Pab1-F364L-GFP (pKW1163), the promoter and coding region of Pab1-1 (BAS 3072) or PabF364L were PCR-amplified, fused in frame with GFP, and cloned into pRS314 (Sikorski and Hieter 1989). Pab1-Cterm-GFP (pKW1164) was constructed by cloning a BamHI/NdeI fragment of pKW1162 into pK1163. Plasmid Pab1Δ9-61 (pKW939) containing the Pab1 promoter and coding region but lacking amino acids 9–61 of Pab1 was obtained by PCR-directed mutagenesis from BAS3072.

The integration construct to genomically replace the HAC1 promoter with the CUP1 promoter (pKW1165) was created by ligating a EcoRI/KpnI PCR fragment of the HAC1 5′-coding region into pPW66R (Dohmen et al. 1994).

The yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. XPO1, xpo1-1 (Stade et al. 1997), MEX67, and mex67-5 (Segref et al. 1997) strains expressing pab1 mutants or Pab1-GFP fusions were created by disrupting the genomic copy of PAB1 using a PCR-generated kanMX cassette in the presence of a covering PAB1 URA3 plasmid (BAS3321, kindly provided by A. Sachs) (Kessler and Sachs 1998). Pab1 expression plasmids were transformed into these shuffle strains and the PAB1 URA3 plasmid was lost by counterselection on 5-fluoro-orotic acid. Genomic PAB1-GFP fusions were generated by PCR-based homologous recombination using a kanMX selection cassette (Longtine et al. 1998). All disruptions were confirmed by PCR and/or Western blot. A heterozygous xpo1-1 mex67-5 diploid strain was created by mating. After sporulation and dissection, haploid xpo1-1 mex67-5 double-mutant cells were selected to obtain LEU+/TRP+ cells and identified by PCR. Strains expressing copper-inducible versions of HAC1 were generated by transforming plasmid pKW1165 linearized with XhoI. Integrants were selected on -URA plates and confirmed by PCR.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains

| Straina | Genotype | Reference |

| KWY120 | xpo1::LEU2 [pRS313 (CEN HIS3) XPO1] | Stade et al. 1997 |

| KWY121 | xpo1::LEU2 [pRS313 (CEN HIS3) xpo1-1] | Stade et al. 1997 |

| KWY460 | xpo1::LEU2 [pRS313 (CEN HIS3) XPO1] PAB1-GFP::kanMX | This study |

| KWY461 | xpo1::LEU2 [pRS313 (CEN HIS3) xpo1-1] PAB1-GFP::kanMX | This study |

| KWY454 | xpo1::LEU2 [pRS313 (CEN HIS3) xpo1-1] pab1::kanMX [pAS414 (CEN TRP1) PAB1-1) | This study |

| KWY456 | xpo1::LEU2 [pRS313 (CEN HIS3) xpo1-1] pab1::kanMX [pAS414 (CEN TRP1) pab1ΔRRM1] | This study |

| KWY481 | xpo1::LEU2 [pRS313 (CEN HIS3) xpo1-1] pab1::kanMX [pAS414 (CEN TRP1) pab1ΔRRM2] | This study |

| KWY482 | xpo1::LEU2 [pRS313 (CEN HIS3) xpo1-1] pab1::kanMX [pAS414 (CEN TRP1) pab1ΔRRM3] | This study |

| KWY483 | xpo1::LEU2 [pRS313 (CEN HIS3) xpo1-1] pab1::kanMX [pAS414 (CEN TRP1) pab1ΔRRM4] | This study |

| KWY484 | xpo1::LEU2 [pRS313 (CEN HIS3) xpo1-1] pab1::kanMX [pAS414 (CEN TRP1) pab1ΔC] | This study |

| MEX67 | mex67::HIS3 [pUN100 (CEN LEU2) MEX67] | Segref et al. 1997 |

| mex67-5 | mex67::HIS3 [pUN100 (CEN LEU2) mex67-5] | Segref et al. 1997 |

| KWY759 | mex67::HIS3 [pUN100 (CEN LEU2) mex67-5] pab1::kanMX [pAS414 (CEN TRP1) pab1ΔPAB1-1] | This study |

| KWY808 | mex67::HIS3 [pUN100 (CEN LEU2) mex67-5] pab1::kanMX [pAS414 (CEN TRP1) pab1ΔRRM1] | This study |

| KWY758 | mex67::HIS3 [pUN100 (CEN LEU2) mex67-5] pab1::kanMX [pAS414 (CEN TRP1) pab1ΔRRM3] | This study |

| KWY809 | mex67::HIS3 [pUN100 (CEN LEU2) mex67-5] pab1::kanMX [pAS414 (CEN TRP1) pab1Δ9-61] | This study |

| KWY610 | mex67::HIS3 [pUN100 (CEN LEU2) mex67-5] xpo1::TRP1 xpo1-1::HIS3] | This study |

| YAS120 | pab::HIS3 [pAS414 (CEN TRP1) pab1-F364L] | Sachs et al. 1987 |

| YAS227 | pab1::HIS3 spb2-1 | Sachs and Davis 1990 |

| KWY908 | pab1::kanMX rrp6::HIS3 | This study |

| KWY709 | mex67::HIS3 [pUN100 (CEN LEU2) mex67-5] CUP1-HAC1::URA3 | This study |

| KWY710 | mex67::HIS3 [pUN100 (CEN LEU2) MEX67] CUP1-HAC1::URA3 | This study |

| KWY712 | pab1::kanMX [pAS414 (CEN TRP1) pab1ΔRRM1] CUP1-HAC1::URA3 | This study |

| KWY786 | pab1::HIS3 [pAS414 (CEN TRP1) pab1-F364L] CUP1-HAC1::URA3 | This study |

| KWY787 | pab1::HIS3 spb2-1 CUP1-HAC1::URA3 | This study |

aAll strains listed except for MEX67 and mex67-5 and their derivatives were derived from W303-A (MATa ura3-1 leu2-3 his3-11,15, trp1-1 ade2-1 can 1-100).

Protein purification and analysis

Yeast extracts were prepared from frozen yeast cells as described (Maurer et al. 2001). Then 6 mL of yeast extract in binding buffer (30 mM HEPES at pH 7.3, 100 mM KOAc, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT) was incubated for 2 h with 250 μL of IgG Sepharose beads either in the presence or absence of 10 μM RanQ71LΔC. Beads were extensively washed with binding buffer and incubated with TEV protease overnight. Mobilized proteins were rebound to 500 μL of S protein agarose beads and incubated for 1.5 h. After several washing steps, proteins were eluted from the beads with 1 M MgCl2 and were separated by SDS-PAGE. Individual bands were cut out and analyzed by MALDI mass spectrometry after trypsin digestion as described (Maurer et al. 2001).

Recombinant Gsp1, Gsp1Q71LΔC, Rna1, Xpo1, Pab1, Pab1ΔRRM1, Pab1ΔRRM2, Pab1ΔRRM3, Pab1ΔRRM4, Pab1ΔC, and Pab1-RRM1 were all expressed as amino-terminal fusions to a His6-tag and purified by metal-affinity chromatography on Ni2+-NTA agarose beads as described (Kessler and Sachs 1998; Maurer et al. 2001).

Ran GTPase hydrolysis assay

GTPase hydrolysis assays were essentially performed as described (Maurer et al. 2001). Briefly, 15 μM the various Pab1 variants were incubated together with 80 nM Gsp1 [γ-32P]GTP and increasing concentrations of Xpo1/Crm1 for 15–20 min on ice. Hydrolysis was started by the addition of 40 nM Rna1. Reactions were stopped exactly after 2 min by the addition of a charcoal mix. The amount of [32P]phosphate release was determined by liquid scintillation counting.

Hac1 maturation assay

Yeast cells expressing HAC1 under the control of the CUP1 promoter were grown to mid-log phase at 30°C in synthetic media containing 2% dextrose. To block mRNA export in the mex67-5 mutant, cells were transferred to the nonpermissive temperature (37°C) for 30 min. Transcription of HAC1 was induced by adding 0.5 mM CuSO4 to the culture. After 10 min of cupper induction, splicing of HAC1 was induced by the addition of 8 mM DTT. Samples were taken at the indicated time points after UPR induction. Total RNA was isolated for Northern blot analysis, and 10–20 μg of total RNA from each time point was separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. The transfer of RNA to a nylon membrane was carried out by capillary blotting in the presence of 10× SSC. The HAC1 probe used in the Northern blot analysis was generated by PCR (5′-oligo: CTGCAGATGTTTAAGACG; 3′-oligo: CCAT CAGAGAACCACGAC). The 281-bp fragment containing exon and intron sequences of HAC1 was then random prime-labeled in the presence of [α-32P]dCTP. Hybridization was carried out at 65°C in Church buffer; wash steps were performed at 65°C in Church wash buffer. Signals were detected using a Phosphor Imager (Molecular Dynamics). The amount of splicing (% splicing) was defined as the ratio of HAC1 spliced and the sum of HAC1 spliced and unspliced multiplied by 100.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Sachs for generously providing various Pab1 reagents including yeast strains, plasmids, and antibodies. We also wish to thank E. Hurt and K. Labib for yeast strains or plasmids. We are grateful to C. Cole for communicating results prior to publication. We thank P. Silver, A. Madrid, and J. Soderholm for their comments on the manuscript and all the members of the Weis lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the Searle Scholars Program and by NIH grant RO1 GM58065 (K.W.).

3Present address: G.W. Hooper Research Foundation, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94143-0552, USA.

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.7291205.

REFERENCES

- Adam, S.A., Nakagawa, T., Swanson, M.S., Woodruff, T.K., and Drey-fuss, G. 1986. mRNA polyadenylate-binding protein: Gene isolation and sequencing and identification of a ribonucleoprotein consensus sequence. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6: 2932–2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonina, E., Stauber, R., and Pavlakis, G.N. 1998. The human poly(A)-binding protein 1 shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 13015–13021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrani, N., Minet, M., Le Gouar, M., Lacroute, F., and Wyers, F. 1997. Yeast Pab1 interacts with Rna15 and participates in the control of the poly(A) tail length in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 3694–3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.T., Paddy, M.R., and Swanson, M.S. 1993. PUB1 is a major nuclear and cytoplasmic polyadenylated RNA-binding protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 6102–6113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askjaer, P., Bachi, A., Wilm, M., Bischoff, F.R., Weeks, D.L., Ogniewski, V., Ohno, M., Niehrs, C., Kjems, J., Mattaj, I.W., et al. 1999. RanGTP-regulated interactions of CRM1 with nucleoporins and a shuttling DEAD-box helicase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19: 6276–6285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff, F.R. and Gorlich, D. 1997. RanBP1 is crucial for the release of RanGTP from importin β-related nuclear transport factors. FEBS Lett. 419: 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet-Antonelli, C., Presutti, C., and Tollervey, D. 2000. Identification of a regulated pathway for nuclear pre-mRNA turnover. Cell 102: 765–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky, A.S. and Silver, P.A. 2000. Pre-mRNA processing factors are required for nuclear export. RNA 6: 1737–1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.E. and Sachs, A.B. 1998. Poly(A) tail length control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae occurs by message-specific deadenylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 6548–6559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caponigro, G. and Parker, R. 1995. Multiple functions for the poly(A)-binding protein in mRNA decapping and deadenylation in yeast. Genes & Dev. 9: 2421–2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1996. Mechanisms and control of mRNA turnover in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 60: 233–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciufo, L.F. and Brown, J.D. 2000. Nuclear export of yeast signal recognition particle lacking Srp54p by the Xpo1p/Crm1p NES-dependent pathway. Curr. Biol. 10: 1256–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, J.A. and Sachs, A.B. 1997. Differential effects of aromatic and charged residue substitutions in the RNA binding domains of the yeast poly(A)-binding protein. J. Mol. Biol. 269: 67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deo, R.C., Bonanno, J.B., Sonenberg, N., and Burley, S.K. 1999. Recognition of polyadenylate RNA by the poly(A)-binding protein. Cell 98: 835–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohmen, R.J., Wu, P., and Varshavsky, A. 1994. Heat-inducible degron: A method for constructing temperature-sensitive mutants. Science 263: 1273–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dower, K. and Rosbash, M. 2002. T7 RNA polymerase-directed transcripts are processed in yeast and link 3′ end formation to mRNA nuclear export. RNA 8: 1888–1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dower, K., Kupperwasser, N., Merrikh, H., and Rosbash, M. 2004. A synthetic A tail rescues yeast nuclear accumulation of a ribozyme-terminated transcript. RNA 10: 686–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, E.F., Hammell, C.M., Hodge, C.A., and Cole, C.N. 2005. Yeast poly(A)-binding protein, Pab1, and PAN, a poly(A) nuclease complex recruited by Pab1, connect mRNA biogenesis to export. Genes & Dev. 19: 90–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englmeier, L., Fornerod, M., Bischoff, F.R., Petosa, C., Mattaj, I.W., and Kutay, U. 2001. RanBP3 influences interactions between CRM1 and its nuclear protein export substrates. EMBO Rep. 2: 926–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrigno, P., Posas, F., Koepp, D., Saito, H., and Silver, P.A. 1998. Regulated nucleo/cytoplasmic exchange of HOG1 MAPK requires the importin β homologs NMD5 and XPO1. EMBO J. 17: 5606–5614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, U., Huber, J., Boelens, W.C., Mattaj, I.W., and Lührmann, R. 1995. The HIV-1 Rev activation domain is a nuclear export signal that accesses an export pathway used by specific cellular RNAs. Cell 82: 475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornerod, M., Ohno, M., Yoshida, M., and Mattaj, I.W. 1997. CRM1 is an export receptor for leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Cell 90: 1051–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, M., Asano, S., Nakamura, T., Adachi, M., Yoshida, M., Yanagida, M., and Nishida, E. 1997. CRM1 is responsible for intracellular transport mediated by the nuclear export signal. Nature 390: 308–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadal, O., Strauss, D., Kessl, J., Trumpower, B., Tollervey, D., and Hurt, E. 2001. Nuclear export of 60S ribosomal subunits depends on Xpo1p and requires a nuclear export sequence-containing factor, Nmd3p, that associates with the large subunit protein Rpl10p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 3405–3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görlich, D. and Kutay, U. 1999. Transport between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15: 607–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görlich, D., Pante, N., Kutay, U., Aebi, U., and Bischoff, F.R. 1996. Identification of different roles for RanGDP and RanGTP in nuclear protein import. EMBO J. 15: 5584–5594. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans, H., Deinert, K., Hurt, E., and Simos, G. 2001. Biogenesis of the signal recognition particle (SRP) involves import of SRP proteins into the nucleolus, assembly with the SRP-RNA, and Xpo1p-mediated export. J. Cell Biol. 153: 745–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammell, C.M., Gross, S., Zenklusen, D., Heath, C.V., Stutz, F., Moore, C., and Cole, C.N. 2002. Coupling of termination, 3′ processing, and mRNA export. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 6441–6457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hector, R.E., Nykamp, K.R., Dheur, S., Anderson, J.T., Non, P.J., Urbinati, C.R., Wilson, S.M., Minvielle-Sebastia, L., and Swanson, M.S. 2002. Dual requirement for yeast hnRNP Nab2p in mRNA poly(A) tail length control and nuclear export. EMBO J. 21: 1800–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilleren, P., McCarthy, T., Rosbash, M., Parker, R., and Jensen, T.H. 2001. Quality control of mRNA 3′-end processing is linked to the nuclear exosome. Nature 413: 538–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.H., Kallstrom, G., and Johnson, A.W. 2000. Nmd3p is a Crm1p-dependent adapter protein for nuclear export of the large ribosomal subunit. J. Cell Biol. 151: 1057–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, T.H., Neville, M., Rain, J.C., McCarthy, T., Legrain, P., and Rosbash, M. 2000. Identification of novel Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteins with nuclear export activity: Cell cycle-regulated transcription factor ace2p shows cell cycle-independent nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 8047–8058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, T.H., Dower, K., Libri, D., and Rosbash, M. 2003. Early formation of mRNP: License for export or quality control? Mol. Cell 11: 1129–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, S.H. and Sachs, A.B. 1998. RNA recognition motif 2 of yeast Pab1p is required for its functional interaction with eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo, N., Wolff, B., Sekimoto, T., Schreiner, E.P., Yoneda, Y., Yanagida, M., Horinouchi, S., and Yoshida, M. 1998. Leptomycin B inhibition of signal-mediated nuclear export by direct binding to CRM1. Exp. Cell Res. 242: 540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzler, M., Gerstberger, T., Stutz, F., Bischoff, F.R., and Hurt, E. 2000. Yeast Ran-binding protein 1 (Yrb1) shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm and is exported from the nucleus via a CRM1 (XPO1)-dependent pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 4295–4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei, E.P. and Silver, P.A. 2002. Protein and RNA export from the nucleus. Dev. Cell 2: 261–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libri, D., Dower, K., Boulay, J., Thomsen, R., Rosbash, M., and Jensen, T.H. 2002. Interactions between mRNA export commitment, 3′-end quality control, and nuclear degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 8254–8266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, M.E., Holaska, J.M., Welch, K., Paschal, B.M., and Macara, I.G. 2001. Ran-binding protein 3 is a cofactor for Crm1-mediated nuclear protein export. J. Cell Biol. 153: 1391–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine, M.S., McKenzie III, A., Demarini, D.J., Shah, N.G., Wach, A., Brachat, A., Philippsen, P., and Pringle, J.R. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14: 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macara, I.G. 2001. Transport into and out of the nucleus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65: 570–594, table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattaj, I.W. and Englmeier, L. 1998. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: The soluble phase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67: 265–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, P., Redd, M., Solsbacher, J., Bischoff, F.R., Greiner, M., Podtelejnikov, A.V., Mann, M., Stade, K., Weis, K., and Schlenstedt, G. 2001. The nuclear export receptor Xpo1p forms distinct complexes with NES transport substrates and the yeast Ran binding protein 1 (Yrb1p). Mol. Biol. Cell 12: 539–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minvielle-Sebastia, L., Preker, P.J., Wiederkehr, T., Strahm, Y., and Keller, W. 1997. The major yeast poly(A)-binding protein is associated with cleavage factor IA and functions in premessenger RNA 3′-end formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 7897–7902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, P., Petfalski, E., Shevchenko, A., Mann, M., and Tollervey, D. 1997. The exosome: A conserved eukaryotic RNA processing complex containing multiple 3′ → 5′ exoribonucleases. Cell 91: 457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey, J.P., Deardorff, J.A., Hebron, C., and Sachs, A.B. 1999. Decapping of stabilized, polyadenylated mRNA in yeast pab1 mutants. Yeast 15: 687–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy, T.I. and Silver, P.A. 1999. Nuclear export of the small ribosomal subunit requires the ran-GTPase cycle and certain nucleoporins. Genes & Dev. 13: 2118–2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville, M. and Rosbash, M. 1999. The NES-Crm1p export pathway is not a major mRNA export route in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 18: 3746–3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville, M., Stutz, F., Lee, L., Davis, L.I., and Rosbash, M. 1997. The importin-β family member Crm1p bridges the interaction between Rev and the nuclear pore complex during nuclear export. Curr. Biol. 7: 767–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paraskeva, E., Izaurralde, E., Bischoff, F.R., Huber, J., Kutay, U., Hartmann, E., Luhrmann, R., and Gorlich, D. 1999. CRM1-mediated recycling of snurportin 1 to the cytoplasm. J. Cell Biol. 145: 255–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil, C. and Walter, P. 2001. Intracellular signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus: The unfolded protein response in yeast and mammals. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13: 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum, J.S., Pemberton, L.F., and Blobel, G. 1997. A nuclear import pathway for a protein involved in tRNA maturation. J. Cell Biol. 139: 1655–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruegsegger, U., Leber, J.H., and Walter, P. 2001. Block of HAC1 mRNA translation by long-range base pairing is released by cytoplasmic splicing upon induction of the unfolded protein response. Cell 107: 103–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, A.B. and Davis, R.W. 1989. The poly(A) binding protein is required for poly(A) shortening and 60S ribosomal subunit-dependent translation initiation. Cell 58: 857–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1990. Translation initiation and ribosomal biogenesis: Involvement of a putative rRNA helicase and RPL46. Science 247: 1077–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, A.B. and Varani, G. 2000. Eukaryotic translation initiation: There are (at least) two sides to every story. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7: 356–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, A.B., Bond, M.W., and Kornberg, R.D. 1986. A single gene from yeast for both nuclear and cytoplasmic polyadenylate-binding proteins: Domain structure and expression. Cell 45: 827–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, A.B., Davis, R.W., and Kornberg, R.D. 1987. A single domain of yeast poly(A)-binding protein is necessary and sufficient for RNA binding and cell viability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7: 3268–3276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, A.B., Sarnow, P., and Hentze, M.W. 1997. Starting at the beginning, middle, and end: Translation initiation in eukaryotes. Cell 89: 831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seedorf, M. and Silver, P. 1997. Importin/karyopherin protein family members required for mRNA export from the nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 8590–8595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segref, A., Sharma, K., Doye, V., Hellwig, A., Huber, J., Lührmann, R., and Hurt, E. 1997. Mex67p, a novel factor for nuclear export, binds to both poly(A)+ RNA and nuclear pores. EMBO J. 16: 3256–3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski, R.S. and Hieter, P. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122: 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stade, K., Ford, C.S., Guthrie, C., and Weis, K. 1997. Exportin 1 (Crm1p) is an essential nuclear export factor. Cell 90: 1041–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stage-Zimmermann, T., Schmidt, U., and Silver, P.A. 2000. Factors affecting nuclear export of the 60S ribosomal subunit in vivo. Mol. Biol. Cell 11: 3777–3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ström, A.C. and Weis, K. 2001. Importin-β-like nuclear transport receptors. Genome Biol. 2: REVIEWS3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sydorskyy, Y., Dilworth, D.J., Yi, E.C., Goodlett, D.R., Wozniak, R.W., and Aitchison, J.D. 2003. Intersection of the Kap123p-mediated nuclear import and ribosome export pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 2042–2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarun Jr., S.Z. and Sachs, A.B. 1996. Association of the yeast poly(A) tail binding protein with translation initiation factor eIF-4G. EMBO J. 15: 7168–7177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakurta, A.G., Ho Yoon, J., and Dhar, R. 2002. Schizosaccharomyces pombe spPABP, a homologue of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pab1p, is a non-essential, shuttling protein that facilitates mRNA export. Yeast 19: 803–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis, K. 2002. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: Cargo trafficking across the border. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14: 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2003. Regulating access to the genome. Nucleocytoplasmic transport throughout the cell cycle. Cell 112: 441–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells, S.E., Hillner, P.E., Vale, R.D., and Sachs, A.B. 1998. Circularization of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Mol. Cell 2: 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen, W., Meinkoth, J.L., Tsien, R.Y., and Taylor, S.S. 1995. Identification of a signal for rapid export of proteins from the nucleus. Cell 82: 463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, C., Lee, L.H., and Davis, L.I. 1998. Crm1p mediates regulated nuclear export of a yeast AP-1-like transcription factor. EMBO J. 17: 7416–7429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenklusen, D., Vinciguerra, P., Strahm, Y., and Stutz, F. 2001. The yeast hnRNP-like proteins Yra1p and Yra2p participate in mRNA export through interaction with Mex67p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 4219–4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J., Hyman, L., and Moore, C. 1999. Formation of mRNA 3′ ends in eukaryotes: Mechanism, regulation, and interrelationships with other steps in mRNA synthesis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63: 405–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]