Abstract

Mitochondria are critical for cellular ATP production; however, recent studies suggest that these organelles fulfill a much broader range of tasks. For example, they are involved in the regulation of cytosolic Ca2+ levels, intracellular pH and apoptosis, and are the major source of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Various reactive molecules that originate from mitochondria, such as ROS, are critical in pathological events, such as ischemia, as well as in physiological events such as long-term potentiation, neuronal-vascular coupling and neuronal-glial interactions. Due to their key roles in the regulation of several cellular functions, the dysfunction of mitochondria may be critical in various brain disorders. There has been increasing interest in the development of tools that modulate mitochondrial function, and the refinement of techniques that allow for real time monitoring of mitochondria, particularly within their intact cellular environment. Innovative imaging techniques are especially powerful since they allow for mitochondrial visualization at high resolution, tracking of mitochondrial structures and optical real time monitoring of parameters of mitochondrial function. Among the techniques discussed are the uses of classic imaging techniques such as rhodamine-123, the highly advanced semi-conductor nanoparticles (quantum dots), and wide field microscopy as well as high-resolution multi-photon imaging. We have highlighted the use of these techniques to study mitochondrial function in brain tissue and have included studies from our laboratories in which these techniques have been successfully applied.

1. INTRODUCTION

Mitochondria play critical roles in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis. For example, mitochondria are not only an important source of cellular energy (ATP) but they also maintain intracellular Ca2+ levels within closely defined ranges for the mediation of signaling, control of neuronal excitability and synaptic function. In the intact brain a tight metabolic coupling exists between the vascular substrate supply of both oxygen (O2) and glucose and the metabolic needs of brain tissue, most importantly neurons and glial cells. This coupling exists following even a small increase in brain metabolic demand, such as sensory or visual stimulation evoking a neuronal response in sensory and visual cortex, respectively. The tight sequence of events occurring after neuronal stimulation include an initial O2 dip in areas of high O2 demand (i.e., those areas primarily stimulated), and a later large O2 increase associated with wide-field arterial vasodilation. These events are tightly correlated with mitochondrial activity through the production of signaling molecules such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).

Neurons within the brain are highly vulnerable to metabolic disturbances; therefore, impairment of mitochondrial ATP generation clearly threatens the viability of both neurons and glial cells, the function of neuronal networks, and consequently normal brain function. De-regulation of cytosolic Ca2+ levels by failure of mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering, and/or release of sequestered Ca2+ present within mitochondria (Biscoe and Duchen, 1990; Kulik and Ballanyi, 1998) contributes to the severe damage of brain tissue in response to glutamate excitotoxicity or metabolic insults, such as cerebral stroke. Similarly, an abnormally increased generation of ROS by mitochondria (such as during ischemia/reperfusion) also threatens neuronal viability, since the multiple ROS buffering mechanisms can be overwhelmed. The resulting oxidative damage of cell membranes, structural and regulatory proteins or redox modulation can, as a consequence, lead to abnormal activity of various ion channels (Chan, 1996, 2001).

Another threatening event for cell viability is the mitochondrial permeability transition (mPT), which occurs in response to mitochondrial Ca2+ overload during excitotoxicity or anoxia/ischemia, elevated cellular ROS levels or adenine nucleotide depletion (Crompton, 1999). The mPT is characterized by a nonspecific increase in the permeability of the inner mitochondrial membrane, loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential (?? m), possible rupture of the outer membrane, and severe mitochondrial swelling. When the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening is transient, the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondrial intermembrane space may activate downstream caspases 9 and 3 and lead to programmed cell death or apoptosis. If the opening is prolonged, mitochondrial content becomes depleted, inducing rapid necrosis (Lipton, 1999; Lipton and Nicotera, 1998; Majno and Joris, 1995).

In view of these diverse mitochondrial functions and their integration into various cellular signaling pathways it is not surprising that alterations in mitochondrial physiology are currently being considered as pivotal events in several neurodegenerative diseases. For example, chronic dysfunction of complex I is being considered as a potential cause of Parkinson’s disease (Schulz and Beal, 1994), complex II dysfunction seems to mediate Huntington’s disease (Cooper and Schapira, 1997), complex IV dysfunction is considered the most frequent disturbance in Leigh disease (Dahl, 1998), and acute inhibition of complex IV (chemical hypoxia) prevents the utilization of O2. Furthermore, increased levels of ROS released from malfunctioning and/or stressed mitochondria, together with changes in ROS defense and scavenging, are considered to be involved in the generation of Alzheimer’s disease (Behl and Moosmann, 2002) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Kong and Xu, 1998).

Many pharmacological tools have been used to study mitochondrial physiology and pathophysiology. These tools have been widely applied in isolated mitochondrial preparations and have in turn contributed to the elucidation of several mitochondrial parameters (e.g., electron transport chain function, membrane potential, free radical formation). However, the combination of pharmacological tools and imaging techniques when applied to intact cells, ex-vivo brain slices or more recently in vivo, are extremely important techniques to derive findings of mitochondrial physiology and in addition supply information about spatial distribution and temporal dynamics. Especially powerful are modern imaging techniques that allow for the visualization of single mitochondria, the tracking of mitochondrial structures and the optical real time monitoring of specific parameters of mitochondrial function, all possible now within intact cells, to increase our knowledge regarding mitochondrial physiology.

In this review, we summarize the tools that are currently available for the study of mitochondrial function and dysfunction. Due to our interest in mitochondrial physiology and the role of mitochondria in hypoxia/ischemia mediated neuronal injury, we have applied a range of techniques to both cell culture preparations and brain slices to further address our interests. Most of our work has been performed on various in vitro preparations of the mammalian brain, but the techniques and tools presented here are by no means restricted to neuronal tissue or vertebrate preparations. We have discussed (using examples) throughout the review the relative approaches of in vitro versus in vivo applications. These comparisons are critical to gain a complete understanding of mitochondrial function and dysfunction.

2. Mitochondrial Physiology

2.1 ATP production and brain activity

Brain function is critically dependent on a continuous supply of O2. Although the brain accounts for only 2% of the body mass, it is responsible for 20% of total O2 consumption and 25% of the body’s energy stores. The critical energy source in the brain is adenosine triphosphate (ATP), produced from adenosine diphosphate (ADP) by substrate-level phosphorylation. Glucose is considered the major source of energy following its metabolism during glycolysis and subsequent oxidative phosphorylation. The majority of ATP in the brain (> 95%) is produced by oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria (Fig. 1). In contrast, glycolysis alone in the cytoplasm contributes to only 1–5% of ATP production (Erecinska and Silver, 1989).

Figure 1. Mitochondrial physiology and pharmacological tools for the selective targeting of mitochondrial function.

A) Mitochondria are descendents of prokaryotic “bacteria”, and therefore have the typical double-layered membrane surrounding the inner matrix space. An enlarged schematic view of a section of the mitochondrial membrane (green box) and its respiratory complexes is shown in the following panel.

B) Schematic representation of the four complexes of the respiratory chain and the mitochondrial ATP synthase (F0F1 ATPase, complex V). Complexes I, III and IV are involved in proton pumping and thus the generation of the inwardly directed proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane. Also, the main components of the mPTP are shown: ANT, CPD and VDAC. For clarity, only a small part of the outer mitochondrial membrane is shown.

C) Summary of drugs targeting the individual respiratory complexes as well the F0F1 ATPase. Mitochondrial uncouplers act as protonophores and collapse the proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane. CsA can prevent the assembly of the various subunits forming the mPTP.

The concentration of ATP is maintained under steady-state conditions in the presence of an adequate supply of O2 and substrates. However, the rate of ATP production may vary among brain regions, cell types and cellular compartments depending on the activity of the region (for review see: (Erecinska and Silver, 1989)). For example, brain regions such as the basal ganglia, thalamus, brain stem and spinal cord show strong cytochrome oxidase staining (which indicates the presence of mitochondria and areas of ATP production) especially in areas containing tonically active neurons. On a cellular level, neurons are more intensely stained compared to glial cells. Within single neurons mitochondrial density in the dendrites is higher than in other areas such as axons or cell bodies. In addition, mitochondria in the dendrites show a dark cytochrome oxidase staining (Wong-Riley, 1989). A direct correlation was reported between the distribution of cytochrome oxidase and Na+/K+-ATPase (probably to maintain energy dependent electrochemical gradients) (Hevner et al., 1992). Overall, axons were found to have lower levels of cytochrome oxidase. These regional differences in ATP production, as indicated by cytochrome oxidase staining, suggest that mitochondria are dynamic and therefore able to rapidly adjust enzyme levels and/or increase in number to satisfy local energy demands in response to physiological as well as pathological conditions (Brines et al., 1995; Wong-Riley, 1989).

Since ATP diffusion within the cells is relatively slow due in part to the tortuosity of the diffusion path through the cellular structures, which include microtubules, filaments and organelles (Ames, 2000; Jones, 1986), it has been suggested that the strategic distribution of ATP synthesis sites may overcome the limitations of diffusion. For example, hexokinase, which requires ATP for glucose phosphorylation in order to initiate glycolysis, is preferentially associated with mitochondria, possibly to gain rapid access to ATP generated by oxidative phosphorylation (da-Silva et al., 2004; Jones, 1986; Wilson, 2003). In addition, glycolytic enzymes have been found to be associated with the plasma membrane, suggesting that ATP produced by glycolysis contributes in part to the maintenance of ion transport, in particular at the Na+/K+ATPase complex (Ames, 2000).

Neuronal and glial function is critically dependent on the maintenance of electrochemical gradients across membranes. Maintenance of the electrochemical gradient largely depends on the Na+/K+ ATP-ase activity and requires approximately 60% of the ATP produced. Therefore when energy production is impaired (e.g., during hypoxia), a rapid loss in ionic homeostasis occurs (Hansen, 1985; Müller and Somjen, 2000; Somjen et al., 1992). For example, the postsynaptic potential in hippocampal slices starts to decrease when ATP is lowered by 15% within 2 min following the initiation of hypoxia (Lipton and Whittingham, 1982). Interventions that limit ATP depletion or that can restore ATP levels to baseline after energy deprivation result in long-term protection of mitochondria and prevent neuronal degeneration (Galeffi et al., 2000; Kass and Lipton, 1982; Riepe et al., 1997). This has formed the premise of the development of several neuroprotective strategies.

2.2 Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation

Mitochondria constitute the major source of superoxide (·O2−) and other ROS within cells, generating approximately 85% of total cellular ·O2−, via aberrant O2 reactions (Boveris and Chance, 1973; Dröge, 2002). During the process of electron transport in mitochondrial complexes I-IV, approximately 2–5% of electrons escape to react directly with readily diffusible O2, resulting in the production of ·O2− at complexes I and III (Boveris and Chance, 1973). During enhanced mitochondrial activity or respiratory chain inhibition (see Fig. 1C for a summary of inhibitors), either chronic or acute, the generation of ·O2− may markedly increase, causing oxidative damage, which is assumed to underlie many neurodegenerative diseases. In addition to mitochondrial ·O2− production, various cytosolic oxidases such as xanthine oxidase and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) oxidase, generate the remaining 15% of cellular ·O2− (Boveris and Chance, 1973; Dröge, 2002).

Once generated, ·O2− is converted both spontaneously and by various forms of superoxide dismutase (SOD) to H2O2 (Cadenas and Davies, 2000). H2O2 may react further, forming the reactive hydroxyl radical (OH·) in the presence of Fe2+ (Dean et al., 1997; Lipton and Nicotera, 1998). Alternatively, ·O2− may react with nitric oxide (NO) to form peroxynitrite (ONOO−) (Lipton and Nicotera, 1998).

Since in most instances, the levels of H2O2 are intrinsically lower in brain than the levels critical for inducing oxidative neuronal damage, H2O2 may act as a physiological, highly permeable signaling molecule, leading to a wide array of signaling functions both between cells as well as to the extracellular environment and adjacent blood vessels. These functions also include neuronal-glial interactions and long-term potentiation (Atkins and Sweatt, 1999; Chan, 2001, 2004; Kamsler and Segal, 2003, 2003; Knapp and Klann, 2002; Serrano and Klann, 2004; Thiels et al., 2000; Yermolaieva et al., 2000). The physiological role of ROS (along with O2 and NO) also extends to the control of vascular tone in the brain, which is tightly modulated by metabolic activity within neurons (Demchenko et al., 2002).

Under normal physiological circumstances cellular H2O2 as well as other ROS are scavenged by the various cellular antioxidants, particularly catalase and the glutathione (GSH) system (Chan, 1996). However, these defense systems may not be capable of keeping up with pathologically enhanced ROS generation resulting from acute or chronic mitochondrial dysfunction. Thus, during both ischemia and reperfusion, for example, excess ROS escape into the interstitial fluid (Lei et al., 1998). The resulting oxidative stress, which is based on the sudden imbalance of oxidizing and reducing agents, may cause both direct and indirect damage to secondary cellular targets. The severity of damage depends on the ROS or reactive nitrogen species (RNS) involved. While ·O2− and H2O2 are less reactive, OH· and ONOO− are considered extremely reactive (Chan, 1996; Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1984; Lipton, 1999). Cellular damage arises from the oxidation of macromolecules such as proteins, membrane lipids and somatic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) (Chan, 1996). Thus not only cellular cytoarchitecture but also function and cytosolic signaling are impaired. For example, ONOO− mediates the nitrosylation of tyrosine and cysteine sulfhydryls, thereby severely disturbing tyrosine phosphorylation-mediated signaling (Martin et al., 1990) as well as sulfhydryl-mediated redox sensing (Lipton et al., 2002; Lipton and Nicotera, 1998).

In view of the deleterious effects of increases in ROS and RNS, various attempts have been made to reduce or even prevent cellular oxidative damage, through the administration of radical scavengers, blocking of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) or overexpression of cellular self-defense systems. Administration of the free radical scavenger a-tocopherol rescued 75% of hippocampal neurons during 5 min global ischemia in gerbils (Hara et al., 1990) while SOD and catalase were found to be neuroprotective in a gerbil model of repeated ischemia (Truelove et al., 1994). In the same models, inhibition of lipid peroxidation was found to reduce neuronal damage (Hara and Kogure, 1990; Truelove et al., 1994). Also the reduction in damage caused by ONOO− by either inhibition or knockout of inducible NOS exerted neuroprotection in an MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) model of parkinsonism in mouse substantia nigra (Liberatore et al., 1999). Overexpression of MnSOD in transgenic mice and the resulting decrease in ·O2− levels reduced lipid peroxidation, protein tyrosine nitration and decreased the cortical infarct volume following middle cerebral artery occlusion (Keller et al., 1998).

2.3 Ca2+ buffering

Mitochondria are able to sequester large amounts of Ca2+ via a uniporter (Gunter and Pfeiffer, 1990; Thayer and Miller, 1990) whenever the uptake of Ca2+ into the cell is greater than the efflux (Nicholls and Akerman, 1982). In resting cells, the concentration of Ca2+ in the cytosol has been estimated in the range of <100 nM to 300 nM (Carafoli, 1987; Cobbold and Rink, 1987; Crompton, 1985; Fiskum, 1985; Rasmussen and Barrett, 1984). The ‘set-point’ or cytosolic concentration at which Ca2+ is accumulated in mitochondria has been determined to be ~500 nM (Nicholls and Scott, 1980), yet depending on the cell type it may also be much lower, as has been shown for hypoglossal motoneurons (von Lewinski and Keller, 2005). Mitochondria thus act as temporary sinks (in addition to endoplasmic reticulum [ER]) to protect cells from toxic Ca2+ levels before releasing the Ca2+ into the cytosol (Nicholls, 1985, 1986). Their large Ca2+ storage capacity is achieved by the formation of a tricalcium phosphate complex (Ca3[PO4]2), which is osmotically inactive and does not interfere with ?? m. Formation of the complex is facilitated by alkaline pH of the matrix space and is quickly resolved upon mitochondrial uncoupling (by, e.g., protonophores) and the resulting proton influx into the matrix space (Nicholls and Chalmers, 2004).

Transportation of Ca2+ across the inner mitochondrial membrane utilizes the electrochemical potential and occurs in place of H+ transport and ATP synthesis, thereby uncoupling electron transport from ATP synthesis (Gunter and Pfeiffer, 1990). However, electron transport occurs during this time in order to maintain the electrochemical gradient. Following its sequestration into mitochondria, Ca2+ is then slowly released into the cytosol via a Na+/Ca2+ exchanger or Na+ independent efflux mechanism leading to a plateau in intracellular Ca2+ (Gunter and Pfeiffer, 1990).

2.4 pH effects

Mitochondrial function modulates the cytosolic pH of the host cell, thereby potentially modulating cell function and neuronal excitability, due to the proton pumping required for energy generation (Fig. 1B). Mitochondrial uncoupling by protonophores in muscle and snail neurons results in a transient increase in cytosolic pH (alkalinization) followed by an acidification (Buckler and Vaughan-Jones, 1998; Kaila et al., 1989; Meech and Thomas, 1980). While the acidification reflects a sarcolemmal H+ conductance induced by the incorporation of the protonophore into the cell membrane, the initial alkalinization reflects proton influx via the protonophore into the mitochondrial compartment (Kaila et al., 1989). Under physiological conditions, rapid changes in mitochondrial activity are indicated by high amplitude fluctuations of ?? m [blinking of mitochondria see Fig. 2D and (Buckman and Reynolds, 2001; Müller et al., 2005; Vergun and Reynolds, 2004)]. These rapid ?? m changes, which reflect variations of the proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane could, especially in spatially confined cellular compartments such as dendrites and axons, result in localized cytosolic pH changes (pH microdomains) around mitochondrial clusters or filaments. The pH changes could then affect nearby located membrane channels and regulatory/structural proteins.

Figure 2. Fluorescence-labeling of mitochondria reveals their organization in single neurons.

A) Fluorescent labeling of mitochondria was achieved by transfection with CFPs targeted to cytochrome oxidase. Shown is a 3-dimensional reconstruction of a cultured neuron that was isolated from the medullary respiratory center (pre-Bötzinger complex) of a juvenile mouse. Note the long mitochondrial filaments, their high density in the soma region, their irregular distribution within the dendrites, and the accumulation of mitochondria in the synaptic terminals (arrows). Mitochondria were visualized by a custom-built 2-photon laser scanning microscope (Müller et al., 2003) at 800 nm excitation wavelength using a 63x 0.9 NA IR-optimized objective (Zeiss Achroplan), a pixel resolution of 250 nm/pixel and a pixel dwell time of 10 μs/pixel. Fluorescence intensity is coded in an 8-bit (256 level) pseudo-color mode ranging from black (low intensity = 0) to red (high intensity = 255) (Müller M. unpublished data).

B, C) Individual mitochondria within the dendrites of respiratory neurons. Mitochondria were labeled by Rh123 (5 μg/ml, 30 min), which reports changes in ?? m and were scanned at a resolution of 60 nm/pixel. Exposing the cell shown in panel C to the complex I inhibitor rotenone (25 μM) induced high amplitude ?? m oscillations in some of the mitochondria. The changes in ?? m for those mitochondria indicated by the arrows are plotted in panel D (Müller M. unpublished data).

D) ? ? m oscillations (“blinking”) upon administration of rotenone. Note the irregular ?? m changes occurring in the 5 mitochondria marked by the arrows in panel C and the subsequent loss of ?? m indicating complete mitochondrial depolarization as well as the irreversible effect of rotenone (Müller M. unpublished data).

Various ion channels are modulated by changes in pH. Among those are voltage-gated Na+ and Ca2+ channels which are activated by alkalosis and blocked by acidosis (Tombaugh and Somjen, 1996, 1997) and which may critically affect cellular function and excitability. Mitochondria-mediated cytosolic pH changes have also been reported to be involved in mitochondria-mediated apoptosis, with cytosolic acidosis promoting cytochrome c-mediated activation of caspases (Matsuyama et al., 2000).

Mitochondrial function itself is also modulated by changes in intracellular pH. The distribution of protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane (low in the matrix space and high in cytosol) contributes to the negative ?? m. It also defines the availability of the phosphate anion, which is required for the formation of the tricalcium phosphate complex in the matrix and thus the mitochondrial storage of Ca2+ (Nicholls and Chalmers, 2004). Therefore, changes in cytosolic pH may directly affect the ?? m.

During ischemia/reperfusion in which massive cellular Ca2+ loading occurs, pronounced cytosolic acidosis leads to increases in mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. This is based on the increased uptake of inorganic phosphate (HPO42−) driven by the proton motive force across the inner mitochondrial membrane (Kristian et al., 2001). It is via this larger mitochondrial Ca2+ load that acidosis favors the opening of the mPTP (Kristian et al., 2001) and thus paves the way for irreversible cell damage and cell loss. Such pH-mediated distortion of mitochondrial function could contribute to the glucose paradox of cerebral ischemia, i.e., the fact that the outcome of cerebral stroke is worse for patients suffering from diabetes mellitus and hyperglycemia, in spite of the apparent benefit which hyperglycemia should provide in anoxic conditions (Schurr et al., 2001).

2.5 Mitochondrial organization and clustering

In each eukaryotic cell mitochondria are abundant and may occupy as much as 10–20% of cellular volume (Bereiter-Hahn, 1990; Müller et al., 2005), with the mitochondrial content being dependent on cell type and its energy demand. In a direct electron microscopic comparison of mitochondrial content in various regions of the rat brain, neurons were found to contain a higher mitochondrial density (17.3%) than astrocytes (11.0%) and oligodendrocytes (11.3%) (Pysh and Khan, 1972). Similar to the cellular content of mitochondria their subcellular distribution is quite heterogeneous. Mitochondria tend to accumulate near high-energy requiring regions, such as pre-synaptic terminals (Fig. 2A), suggesting directed motility and clustering according to energy needs. Most textbooks still depict mitochondria as free floating, bean-shaped organelles, a situation that has been found in electron micrographs of liver tissue and which has been propagated by the preparation of ultra-thin tissue sections and the resulting two-dimensional images obtained by this technique (Skulachev, 2001). However, it is now clear that mitochondria show a considerable degree of higher-level organization, forming linked mitochondrial arrangements, directed towards strategic locations within a cell. For example, in various tissues mitochondria were found to be organized in long mitochondrial filaments (also being referred to as mitochondrial chains, or tubules) or to have formed irregularly shaped mitochondrial clusters (Amchenkova et al., 1988; Dedov and Roufogalis, 1999; Müller et al., 2005). Examples of such mitochondrial filaments and clusters are shown in Fig. 2.

Studies from our laboratory have found that mitochondrial filaments are mostly in dendritic processes, while mitochondrial clusters dominate the soma region (Müller et al., 2005). High resolution electron tomography of single cortical, striatal, cerebellar and hippocampal mitochondria revealed synaptic and dendritic mitochondria to be mostly of globular shape, axonal mitochondria to be cigar-shaped, and somatic mitochondria to be of either shape (Perkins et al., 2001).

Within mitochondrial clusters or chains the single mitochondria are not simply physically attached, but they are indeed functionally coupled. Such coupling has been reported for mitochondria in fibroblasts, cardiomyocytes, astrocytes, sensory neurons and striated muscle (Amchenkova et al., 1988; Skulachev, 2001). Localized laser bleaching in neurons isolated from the respiratory brain stem center also demonstrated this concept of coupling. In these cells the highly localized (1 μm2) illumination of up to 12 μm long mitochondrial filaments resulted in the irreversible loss of ?? m (as probed by rhodamine 123 (Rh123) fluorescence) over the entire length of the filaments, including the non-illuminated parts. In contrast, other mitochondrial filaments that were located nearby were not affected (Müller et al., 2005). Thus, mitochondrial coupling is a dynamic process, and time lapse recordings of single labeled mitochondria demonstrating fusion and fission of the various mitochondrial structures can be observed occasionally under physiological as well as pathophysiological conditions (De Vos et al., 2005; Lewis and Lewis, 1914; Müller et al., 2005). For example, hypoxic conditions were found to promote the fusion of mitochondria (Bereiter-Hahn, 1990). The functional coupling of mitochondria requires the fusion of their inner and outer membranes, and it is apparently achieved by the involvement of various mitochondrial proteins located within these membranes, which cooperate to form a common fusion apparatus (Hales and Fuller, 1997; Yaffe, 2003).

Mitochondria also develop close connections with cytoskeletal components, such as microtubules, actin filaments and intermediate filaments. These interactions are involved in the anchoring of mitochondria as well as their transport and motility inside cells, thereby offering the unique possibility to adjust the subcellular spatial distribution of mitochondria to a cell’s current metabolic demands, particularly in terms of growth and development and other plastic changes in the cellular structure (Ligon and Steward, 2000; Morris and Hollenbeck, 1995; Müller et al., 2005).

The mechanisms that control mitochondrial movements and determine their subcellular distribution are only poorly understood. In addition to our findings that increased cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels reversibly arrest mitochondrial transport (Müller et al., 2005), others have reported that neurotoxic concentrations of glutamate (Rintoul et al., 2003) and NO formation (Rintoul et al., 2006) arrest mitochondrial movements in forebrain neurons. Even though the detailed molecular events have yet to be clarified, the loss of ?? m seems to play a central role in such impairment of mitochondrial transport (Rintoul et al., 2006). Hence it simply could be a local shortage of ATP that inhibits mitochondrial movements, since ATP is required to drive the molecular motors along microtubules. Also high local concentrations of Ca2+, either resulting from e.g., glutamate-mediated Ca2+ influx or released from dysfunctioning mitochondria (Kulik and Ballanyi, 1998; Müller and Ballanyi, 2003) could be responsible for the arrest of mitochondrial movements by impairing cytoskeletal integrity (van Rossum and Hanisch, 1999).

The variability of mitochondrial distribution and their polymorphism is associated with heterogeneous functional responses. The membrane potentials of mitochondria within a single cell are not uniform, as was revealed by 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) labeling (Smiley et al., 1991). Also their sensitivity to Ca2+-mediated stress differs. Synaptic mitochondria obtained from rat cortex are more sensitive to Ca2+ overload and undergo the mPT earlier than their nonsynaptic counterparts (Brown et al., 2006). Also the expression of certain mitochondrial ion channels, e.g., the BK-type KCa channels, was found in only a subset of cerebellar Purkinje cells, most notably in perinuclear mitochondria (Douglas et al., 2006). Such subcellular heterogeneity may prove to have important implications for the characteristic damage patterns of neurodegenerative diseases and the selective vulnerability among neurons in the brain.

3. Pharmacological Tools

3.1 Inhibitors of mitochondrial respiration

The respiratory chain consists of a number of enzyme complexes designated as: complex I (NADH-ubiquinol oxidoreductase); II (succinate-ubiquinol oxidoreductase); III (ubiquinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase); and IV (cytochrome c oxidase), in which reduction/oxidation reactions occur (Fig. 1B). ATP is produced separately by the protein cluster ATP synthase, sometimes termed complex V or F0F1 ATPase using the proton gradient as an energy source (for a more detailed review, please see (Balaban, 1990; Senior, 1988) ).

Compounds that inhibit the respiratory chain at various target points (Fig. 1C) have contributed to the understanding of the oxidative phosphorylation process and proton transport. Site-specific inhibitors of the electron transport chain prevent the passage of electrons by binding to a component of the chain, hence blocking the oxidation/reduction reactions critical to mitochondrial function and therefore indirectly inhibiting ATP synthesis.

3.1.1 Complex I inhibitors

Complex I (NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase) inhibitors include over sixty different families of various compounds. Among complex I inhibitors are: pesticides; insecticides of natural origins such us rotenone and piericidin A; synthetic drugs and neurotoxins such as Amytal (barbiturates); and the toxic synthetic compound, MPP+ (1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium). These compounds act at or close to the ubiquinone (Q) reduction site. Many of these inhibitors have structural similarities with Q, suggesting perhaps a common binding site.

Natural rotenone is the most widely used inhibitor of complex I and belongs to the rotenoids, a family of isoflavonoids extracted from Laguminosae plants. Based on its mechanism of action, rotenone is classified as a semiquinone antagonist, together with Amytal. The protein subunits ND1 and ND4 are involved in the binding of rotenone to complex I (Degli Esposti, 1998). Rotenone inhibits complex I by interfering with the electron transfer from the Fe-S cluster to the flavin mononucleotide (FMN)-a group (Albracht et al., 2003), thereby preventing the utilization of NADH as a substrate. In contrast, the electron flow resulting from the oxidation of succinate is unimpaired, because the electrons in this case enter through ubiquinol (QH2), which is beyond the site of rotenone inhibition.

Piericidins are produced by various Streptomyces strains and have contributed extensively to the understanding of the enzymatic properties of complex I. Piericidin A binds at two sites within complex I, thereby powerfully inhibiting electron transfer within this complex. The tight binding of piericidin A to complex I essentially prevents its displacement by rotenone and Amytal (Degli Esposti, 1998). Complex I inhibitors are probably the most widely used in the large variety of inhibitor studies because complex I is the largest and most complicated electron transfer complex. The structures of its 43 subunits have yet to be characterized. In addition, complex I is the respiratory enzyme most likely to be affected by mitochondrial DNA mutations and to be involved in human disease, since 40% of human mitochondrial DNA encodes for 7 subunits of complex I (Walker, 1995), while the remaining 36 subunits are encoded by the nuclear genome.

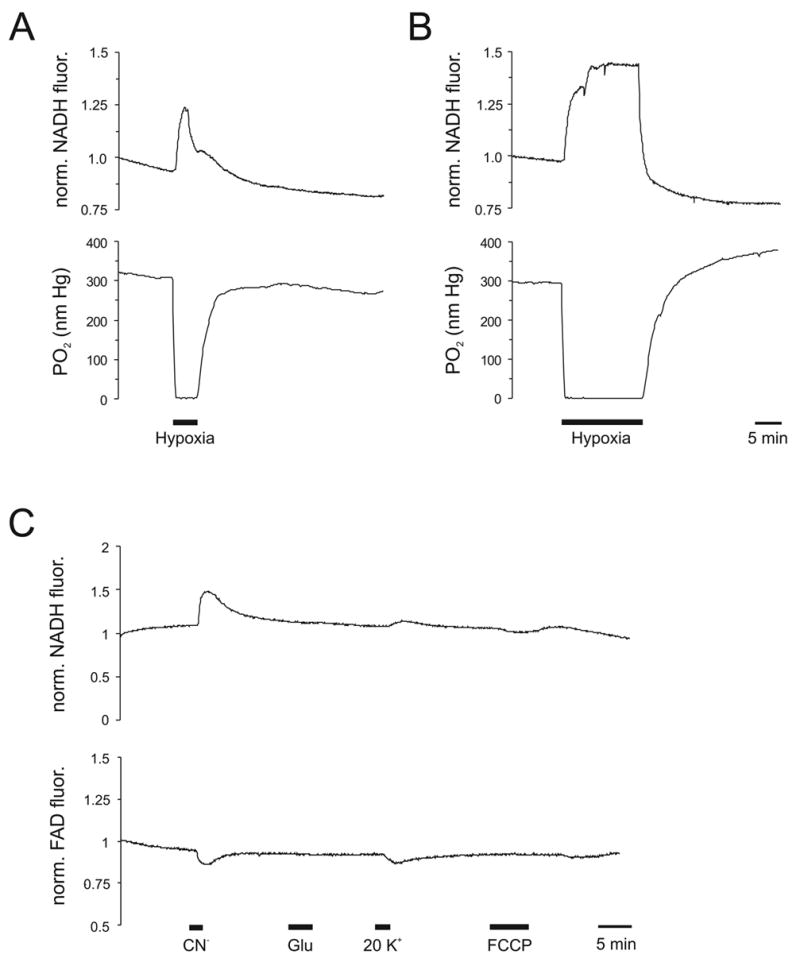

Diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) binds to the FMN-compound thereby inhibiting complex I between the NADH binding site and the Fe-S-clusters. However, DPI does not specifically target mitochondria, as it also blocks various oxidases (Li and Trush, 1998). We found that the application of DPI to acute hippocampal slices facilitated the onset of hypoxic spreading depression (hSD) similar to rotenone. Interestingly, the administration of DPI induced a decrease in NADH autofluorescence and an increase in flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) levels suggesting that mitochondrial respiration was stimulated. This effect, however, was probably caused independently of the inhibition of complex I by DPI (Gerich et al., 2006).

In brain preparations, rotenone has been one of the most widely used inhibitors to study the role of the electron transport chain in the production of ROS. Inhibition of complex I by rotenone (10–1000 nM) in isolated brain synaptosomes caused an increase in H2O2 after complex I activity was inhibited by 16% (Sipos et al., 2003). These results suggest that complex I itself could be the site of ROS formation in inhibited mitochondria, as well as in mitochondria with defective complex I. However, the application of rotenone for this purpose has given different results depending on the preparation and the substrate used. In the presence of the substrates pyruvate and glutamate, rotenone increases H2O2 production in brain mitochondria (Votyakova and Reynolds, 2001). This increase was inhibited if succinate was used as a substrate instead.

The application of rotenone may have different effects on ROS production when it is applied to intact neuronal cells or tissue under conditions that increase free radical formation, such as exposure to glutamate or cerebral ischemia. In cultured hippocampal neurons, rotenone (3 μM) in combination with oligomycin (2 μM), for example, lowered free radical formation after N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) exposure (Luetjens et al., 2000). In vivo intracerebral infusion of rotenone (10 μM) inhibits ROS formation in the hippocampus during transient global ischemia. However, if succinate is administered with rotenone, ROS are still produced. The administration of succinate, which fuels the respiratory chain by bypassing complex I through activation of complex II, is able to overcome the rotenone-induced inhibition of ·O2− production that is probably occurring at complex III after ischemia (Piantadosi and Zhang, 1996).

Respiratory substrates and electron transport chain inhibitors also modulate mPTP opening, which in turn has dramatic consequences on respiration. For example, much higher Ca2+ loads are required to open the pore when electrons are provided to complex II rather than to complex I. In the presence of succinate and rotenone, the load of Ca2+ required to induce mitochondrial depolarization and swelling was three to four times higher than when mitochondria were incubated with glutamate and malate (Leverve and Fontaine, 2001).

3.1.2 Complex II inhibitors

In contrast to complex I only a small number of agents are available which can specifically inhibit complex II. Malonate, which is structurally similar to succinate, is a competitive inhibitor of succinate dehydrogenase, the critical enzymatic component of complex II. Other inhibitors of complex II include the fungicide carboxin, which is now considered a major environmental hazard, because of its extremely high affinity for mammalian succinate dehydrogenase. Additionally, 2-thenoyltrifluoroacetate (TTFA) is a classical inhibitor for the Q reduction site of complex II, but is used primarily for in vitro assays of complex II in isolated mitochondria (Barja and Herrero, 1998; Sun et al., 2005).

The compound 3-NPA (3-nitropropionic acid) is an irreversible inhibitor of succinate dehydrogenase (Coles et al., 1979). 3-NPA was tested in hippocampal slices and found to cause extracellular zinc accumulation, indicating the release of zinc from intracellular sites (Wei et al., 2004). Inhibition of complex II has been used to model the pathology of Huntington’s disease, and the inhibition of complex II by 3-NPA has demonstrated increased vulnerability of striatal neurons by causing irreversible membrane depolarization. In contrast, cholinergic interneurons were hyperpolarized (Saulle et al., 2004). Additionally, 3-NPA (in the presence of dopamine) can lead to enhanced NMDA-mediated long-term potentiation in striatum, suggesting increased sensitivity to complex II antagonists (but not complex I) in this region (Calabresi et al., 2001).

3.1.3 Complex III inhibitors

Electron flow in complex III (cytochrome c oxydoreductase) can be blocked by either the antibiotic antimycin A, which is produced by streptomyces, or myxothiazol. Antimycin A binds at the QI sites (internal Q, in proximity to the matrix), and inhibits the electron transfer from semiquinone to QI (Lai et al., 2005), whereas myxothiazol binds at external Q0 (in proximity to the intermembrane space). Antimycin A and myxothiazol have both been used to study the catalytic activity and structural characteristics of complex III (Miyoshi, 1998; Rieske et al., 1967).

The inhibition of the electron transport chain at complex III can also lead to ROS generation (Barja, 1999). The activity of complex III can be impaired in various conditions, such as exposure to hypoxia and in aging. During hypoxia, for example, complex III is inhibited at both the QI and Qo sites. In aged rats, the application of antimycin A (47 μM) and myxothiazol (9 μM) in submitochondrial particles isolated from the heart identified a defect in the ubiquinol (QH2) binding site (Q0) in complex III that may lead to increased ROS formation in aging cardiac mitochondria (Moghaddas et al., 2003). The application of antimycin A to isolated heart mitochondria induced an increase in H2O2 production in mitochondria respiring on complex I and complex II substrates. However, only when mitochondria were respiring on glutamate or pyruvate/malate, was rotenone fully able to suppress the ability of antimycin A to produce H2O2. This result suggests that complex III is the principal site of ROS production, and that rotenone blocks the primary flow of electrons into complex III (Chen et al., 2003).

To test the effect of complex III inhibition that is observed during hypoxia, antimycin A (3 μM) was applied to acutely dissociated CA1 pyramidal neurons (Lai et al., 2005). Antimycin A decreased Na+ currents and subsequently neuronal excitability, possibly through H2O2 production, and increased activity of protein kinase C (PKC). In cultured hippocampal neurons antimycin A (10 μM) increased ROS production, but blocked the ability of NMDA to produce a further increase in ROS, indicating that inhibition of complex III due to cytochrome c release may be implicated in ROS production and cell death after an excitotoxic insult (Luetjens et al., 2000). Although antimycin A and myxothiazol have been shown to induce an increase in ROS in a variety of tissues using a range of approaches, the ability of complex III to produce ROS and ROS-induced cell damage remains to be explicitly proven.

Mitochondrial populations demonstrate different degrees of sensitivity to respiratory chain inhibition and thus ROS formation. For example, synaptic and non-synaptic mitochondria have different susceptibilities to injury induced by antimycin A. In isolated brain mitochondria oxidizing glutamate and malate, the application of antimycin A (1 μM) resulted in an increase in H2O2, which was not inhibited by rotenone (1 μM). Instead, rotenone induced an additional production of H2O2 (Votyakova and Reynolds, 2001). Antimycin A (5–50 nM) has also been applied to synaptosomes to determine the threshold of complex III inhibition in order to produce ROS in synaptic mitochondria. In one study, 70% inhibition of complex III was required to induce an increase in H2O2 formation, indicating that in synaptic mitochondria ROS production from complex III is less relevant to physiological or pathological conditions than from complex I, where only 16% inhibition by rotenone is sufficient to induce a significant increase in ROS formation (Sipos et al., 2003).

3.1.4 Complex IV inhibitors

Under normal physiological conditions, electrons in complex IV are donated to O2, which is subsequently reduced to water (Babcock, 1999). Cyanide (CN−), azide (N3−) and carbon monoxide (CO) inhibit complex IV (cytochrome oxidase) by blocking the transfer of electrons from complex IV to O2. CN− and N3− react with the ferric form of heme a3, while CO reacts with the ferrous form of heme a3 (Berg et al., 2002). This inhibition causes chemical hypoxia by preventing the utilization of O2. Azide has been used in the development of models of chronic Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Kaal et al., 2000; Szabados et al., 2004). Sodium azide administered to rats at 45 mg/kg/day caused both cognitive deficits and histopathological changes similar to changes caused by Alzheimer’s disease (Szabados et al., 2004), while the administration of up to 100 μM azide caused dose dependent death in motoneurons (Kaal et al., 2000). A concentration of 30 μM was lethal to motoneurons as compared to the survival of 44% of interneurons at the same concentration (Kaal et al., 2000). In contrast, many interneurons are spared in the hippocampus following global ischemia, even though hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells are severely damaged (Freund et al., 1990). Thus, the chemical hypoxic effects of azide mimic global ischemia.

CN− has also been used extensively to study mechanisms involved in neurodegeneration and cell death, since it is rapid acting and neurotoxic, but also partially reversible. CN− initiates a series of reactions leading to cell death, which include release of K+ from mitochondria and efflux from neurons (Liu et al., 2003) and the enhancement of NMDA receptor function with a subsequent increase in cytosolic Ca2+ (Patel et al., 1992; Sun et al., 1997). The mobilized Ca2+ stores then can enhance the generation of free radicals, which secondarily cause lipid peroxidation (Gunasekar et al., 1996). CN− also causes the release of Ca2+ and cytochrome c from mitochondria (Liu et al., 2003; Müller and Ballanyi, 2003). Depending on the cell type and degree of insult, the application of CN− can lead to apoptosis or necrosis. For example, the application of CN− (400 μM) to primary cortical neurons caused apoptosis, whereas exposure of the same concentration of CN− to mesencephalic neurons caused necrosis (Prabhakaran et al., 2002). Since mitochondria are the primary target of CN− they respond within a few seconds with a major depolarization (Fig. 3). Also, the transport of mitochondria, which occurs along cytoskeletal tracks such as microtubules and actin filaments, is reversibly halted in the presence of CN− (Müller et al., 2005). The mechanisms involved in the arrest of mitochondrial movements have not yet been identified, though candidate events include local ATP shortage, loss of ?? m, cytosolic Ca2+ changes, and protein phosphorylation (see also section 2.5) (Müller et al., 2005; Rintoul et al., 2006; Rintoul et al., 2003).

Figure 3. Continuous monitoring of ?? m in single neurons and in acute tissue slices.

A) Rh123 labeled mitochondria within a cultured respiratory neuron. Note the increase in background fluorescence and the loss of structural labeling, as the cells are exposed to CN− (1 mM). Images were taken with a two-photon laser-scanning microscope using a 63x objective and a pixel resolution of 250 nm/pixel (Müller M. unpublished data).

B) Time course of the changes in rhodamine fluorescence (normalized to pre-treatment baseline conditions) quantified in three regions of interest within the cytosol (arrow 1) and two mitochondrial clusters (arrows 2, 3) of the cell shown in panel A. Note the opposite changes in cytosolic and mitochondrial compartments. As the mitochondria depolarize in response to CN−, Rh123 is released into the cytosol. Accordingly, cytosolic fluorescence markedly increases (black trace) while the fluorescence intensity of the mitochondrial structures decreases (blue and red traces). Upon washout of CN− the mitochondria regain their ?? m and the Rh123 fluorescence returns to pre-treatment baseline conditions (Müller M. unpublished data).

C) Measurement of Rh123 fluorescence in bulk-loaded slices. Using the appropriate filter sets, Rh123-fluorescence was monitored in combination with NADH autofluorescence, thereby obtaining changes in ?? m (Rh123) as well as mitochondrial respiration ([NADH]) and important details on mitochondrial dysfunction. Rh123-fluorescence and autofluorescence was captured with a highly sensitive CCD camera (QE, PCO) using a 40x 0.75NA water mmersion objective (Zeiss Achroplan) and quantified within a region of interest in stratum radiatum of an acute rat hippocampal slice. Note that in response to 1 mM CN−, 500 μM glutamate and 1 μM FCCP, NADH fluorescence consistently increased at a steeper rate and reached its plateau earlier than Rh123 fluorescence, indicating that upon inhibition of mitochondrial respiration the ?? m can at least partially be maintained for a limited period of time (Müller M. unpublished data).

CN− has also been used to study the differential response of hippocampal cells to chemical hypoxia by examining changes in membrane potential (Englund et al., 2001). The application of CN− (2 mM) to CA1 neurons causes hyperpolarization in cells with less negative resting membrane potential, and transient depolarization in cells with more negative resting membrane potential, indicating that CN− activates K+ channels. Applied to interface hippocampal slices, 1 mM CN− (as well as 2 mM azide) trigger spontaneous spreading depression episodes despite the presence of O2 (Gerich et al., 2006). Activation of KATP channels by CN− was found in dorsal vagal neurons, where KATP channels were activated independent of ATP depletion – obviously as a direct consequence of impaired mitochondrial metabolism or mitochondrial depolarization (Müller et al., 2002). However, a loss of membrane potential or massive Ca2+ influx did not occur in these cells even during prolonged CN− induced chemical anoxia (Müller and Ballanyi, 2003). CN− has also been shown to increase voltage-dependent Na+ currents in CA1 hippocampal cells (Hammarström and Gage, 1998).

The inhibition of mitochondria in motoneurons has been implicated in the neurodegenerative disorder amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and hypoxia may be a causative factor. CN− was used to investigate the underlying vulnerability of these cells to hypoxia, compared to more resistant cell types such as dorsal vagal neurons. The application of CN− to patch clamped motoneurons in brainstem slices caused cellular influx of Na+ and increases in cytosolic Ca2+ levels as a result of: 1) Ca2+ release from mitochondria, 2) slowing of Ca2+ clearance rates from the cytosol and 3) elevated firing rate induced by secondary Ca2+ influx (Bergmann and Keller, 2004). The observed vulnerability of the motoneurons to mitochondrial impairment is suggested to be in part due to their low buffering capacity of cytosolic Ca2+, high-energy requirements and an increase in electrical excitability during hypoxia (Bergmann and Keller, 2004). From these studies, it is evident that the toxicity of CN− varies considerably across various cell types in the central nervous system.

3.2 Mitochondrial uncoupling by protonophores

A number of compounds (both exogenous and endogenous) exist that interfere with the flow of protons (H+) produced by mitochondria. Under normal physiological circumstances, the transport of electrons between mitochondrial complexes I-IV provides energy to transfer protons (H+) across the inner membrane (Fig. 1B). The resulting electrochemical gradient, expressed as the ΔΨm (−150 to −180 mV) (Mitchell, 1966), is vital to both ATP production and Ca2+ accumulation and is therefore essential to the maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis. Dissipation of the proton gradient results in the cessation of ATP energy production (uncoupling) while electron and proton transport continues unabated (and may even be increased, due to the positive feedback from ADP).

Endogenous protonophores (uncoupling proteins) act to uncouple ATP synthesis from electron transport and are found in the inner membrane of mitochondria. Thermogenin or uncoupling protein 1 (UCP-1) lowers ΔΨm and increases the permeability of the inner mitochondrial membrane to H+ in order to generate heat in brown adipose tissue (Klingenberg and Echtay, 2001). Uncoupling proteins, particularly uncoupling protein 2 (UCP-2), may also play a significant role in the regulation of brain metabolism and intracellular signaling, particularly in terms of the modulation of ROS generation. For example, UCPs may modulate the formation of ·O2− and as a result H2O2 through their uncoupling activity (Casteilla et al., 2001; Negre-Salvayre et al., 1997). In addition, UCP-2 may be induced as a protective stress signal following neuronal injury. This was demonstrated in wild-type mice in which lesioning of the entorhinal cortex resulted in the expression of UCP-2 and activated caspase-3 immunoreactivity. Lesions in mice overexpressing UCP-2, however, resulted in a lower number of activated caspase-3 cells compared to wild-type animals (Bechmann et al., 2002). The overexpression of UCP-2 has also been shown to reduce neuronal damage following oxygen-glucose deprivation in cultured cortical neurons and following middle-cerebral artery occlusion in mice overexpressing the UCP-2 protein. UCP-2 is suggested to exert its protection by lowering ROS release and preventing the activation of both mPT and capase-3 (Mattiasson et al., 2003).

Drugs such as carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP), carbonyl cyanide p-trifluromethoxy-phenylhydrazone (FCCP) and 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) shuttle protons from the intermembrane space back into the mitochondrial matrix, thereby diverting protons from the ATP synthase (Fig. 1B, C). This diversion of protons causes mitochondrial depolarization, which increases the rate of respiration, thereby short-circuiting the ?? m and uncoupling electron transport from ATP synthesis (Duchen, 1999). The unique effects of the different types of protonophores (i.e., compounds acting as either channels or carrier molecules to shuttle protons across membranes) on mitochondria have allowed for the various functions of mitochondria to be further investigated. DNP, CCCP, and FCCP have been the most widely used protonophores for this purpose and therefore are described in more detail below.

DNP is produced as a result of the addition of H+ to 2,4-dinitrophenate. DNP is lipophilic and uncouples oxidative phosphorylation from ATP production by shuttling protons back into the mitochondrial matrix, thereby directly decreasing the ΔΨm (Loomis and Lipmann, 1948). Since the ΔΨm controls the influx of Ca2+ into mitochondria (Gunter et al., 1994), it has been suggested that Ca2+ influx is decreased as a result of uncoupling. Mitochondrial uncouplers such as DNP (and CCCP, FCCP; see below) have been used extensively to elucidate the mechanism of disruption of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, in particular the relationship to mitochondrial ΔΨm following excessive glutamate stimulation. In the presence of glutamate, the addition of 300 μM DNP to granule cells from rat cerebellum induced mitochondrial depolarization, increases in [Ca2+]i and a sharp decrease in intracellular ATP (compared to glutamate alone). Following the removal of DNP, the [Ca2+]i rapidly recovered to baseline levels (Khodorov et al., 2002).

Although prolonged uncoupling leads to the collapse of the ΔΨm and depletion of ATP stores, temporary uncoupling by DNP is suggested to have little effect on both the ΔΨm and ATP levels (Kaim and Dimroth, 1999). Because of this finding, DNP has been investigated for its neuroprotective properties following cerebral ischemia. In a study conducted by Korde and colleagues (2005), the administration of DNP following transient focal cerebral ischemia was found to reduce infarct volume compared to vehicle-treated animals. The mechanisms of neuroprotection by DNP were shown to be the attenuation of both Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria (only in the ischemic penumbra) and a decrease in ROS formation in both the penumbra and core tissue (Korde et al., 2005). In a separate study, rats were treated with DNP prior to a striatal injection of quinolinic acid followed by mitochondrial isolation. DNP was shown to attenuate increases in mitochondrial Ca2+ as well as ROS formation induced by quinolinic acid. In addition, DNP also improved mitochondrial function as indicated by an increase in O2 consumption compared to treatment with TNP (2,4,6-trinitrophenol, a DNP analog, which cannot uncouple intact mitochondria) prior to quinolinic acid injection (Korde et al., 2005).

CCCP is a weak acid with lipophilic properties. It acts to uncouple mitochondria by dispelling the H+ gradient and releasing Ca2+ that has been sequestered in mitochondria. CCCP has been used to show that mitochondria play a role in buffering Ca2+ loads in neurons (Werth and Thayer, 1994). Following depolarization (by superfusion of 50 mM K+) in dorsal root ganglion neurons, the application of CCCP caused a sharp increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ (during the plateau phase of the Ca2+ transient), suggesting mitochondrial release by uncoupling. In comparison, the application of CCCP to resting cells elicited a much smaller increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+(Werth and Thayer, 1994), which was followed by a gradual decline to baseline levels while CCCP was still present. CCCP has also been used to examine mitochondrial buffering of Ca2+ in cortical neurons (White and Reynolds, 1995) and cerebellar granule cells (Budd and Nicholls, 1996; Kiedrowski and Costa, 1995).

FCCP is an analog of CCCP and also causes a collapse in the H+ gradient across the mitochondrial membrane. Dissipation of the proton gradient causes not only inhibition of ATP synthesis but also the reversal of the ATP synthase, which then results in the hydrolysis of ATP since the equilibrium of the ATP synthase is predicated by both the ATP/ADP.P1 ratio and the ΔΨm. The application of FCCP (1 μM) causes a significant decrease in ATP content in cortical synaptosomes (Tretter et al., 1997) as well as in astrocytes (Juthberg and Brismar, 1997). Because of this, oligomycin (which blocks the mitochondrial ATP synthase without affecting the ΔΨm) has been used regularly in conjunction with FCCP to counter the effect of ATP depletion by FCCP (eg. (Storozhevykh et al., 2001; Villalba et al., 1994).

FCCP also acts to inhibit the uptake of Ca2+ into mitochondria by causing the Na+/Ca2+ gradient along the mitochondrial membrane to collapse (Budd and Nicholls, 1996; Gunter and Pfeiffer, 1990; Prehn et al., 1994; White and Reynolds, 1996). The application of FCCP (750 nM) to cultured forebrain neurons has been shown to cause a reversible collapse of ΔΨm using the fluorescent dye JC-1 (White and Reynolds, 1996). In comparison to CCCP, which elicits a further increase in Ca2+ during the plateau phase following depolarization (Werth and Thayer, 1994), the application of FCCP does not alter Ca2+ levels (Khodorov et al., 1996).

The use of FCCP has demonstrated the dependence of ROS production (H2O2) on mitochondrial ΔΨm and the NADH redox state in the presence of NADH-linked substrates (malate and glutamate or α-ketoglutarate). In a study conducted in isolated mitochondria, H2O2 production decreased concomitantly with a reduction in ΔΨm (produced by 0–80 nM FCCP) in the presence of the NADH-linked substrates. However, the application of 80 nM FCCP, which caused maximum reduction of the ΔΨm still resulted in 30% of the maximal ROS (H2O2) production (Starkov and Fiskum, 2003).

The administration of FCCP (1 μM) to cultured rat hippocampal neurons has been shown to cause mitochondrial generation of ·O2− equivalent to that produced by lethal concentrations of NMDA (300 μM). However, no neurotoxicity was evident from the application of FCCP alone at 1 μM or higher (10 μM) or even over longer periods of exposure (1 μM for 20 min). The co-administration of FCCP (1 μM) with 100 μM NMDA did not increase the amount of ·O2− generation but did lead to increased neurotoxicity (Sengpiel et al., 1998). The administration of only 100 μM NMDA caused a decrease in cell viability. These results suggest that although the generation of ·O2− is associated with NMDA toxicity, ·O2− production alone is insufficient to cause neuronal degeneration. It is, however, known that ·O2− can react rapidly with NO (produced by endothelium, macrophages, neutrophils and brain synaptosomes) following excessive stimulation of the NMDA receptor to form ONOO−, which does cause neurotoxicity (Beckman et al., 1990; Lipton et al., 1993).

FCCP has also been used to examine the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering in excitotoxic cell death. When FCCP (750 nM) is applied to forebrain neurons in the presence of glutamate (100 μM) and glycine (10 μM), mitochondrial membrane depolarization is enhanced compared to the application of glutamate and glycine alone (Stout et al., 1998). In addition, the [Ca2+]i is increased with the co-application of FCCP compared to stimulation by glutamate and glycine alone. Despite the increases in [Ca2+]i, the transient inhibition of mitochondrial function prevented glutamate induced cell death, which demonstrates that the uptake of Ca2+ by mitochondria is a requirement of excitotoxicity. Specifically, FCCP is suggested to have prevented the generation of ROS induced by glutamate (Stout et al., 1998). In a separate study, the co-application of FCCP (1μM) with glutamate (0.5 mM) to spinal cord motor and non-motor neurons blocked Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria. FCCP was also shown to directly prevent the increase in ROS generated by glutamate exposure as indicated by a decrease in dihydrorhodamine-123 (DHR123) fluorescence (Urushitani et al., 2001). Unlike CCCP, FCCP may also act on non-mitochondrial Ca2+ stores (Jensen and Rehder, 1991; Ruben et al., 1991). For example, the application of FCCP to Helisoma (snail) neurons in which the mitochondria had been depleted of their Ca2+ stores was found to cause an indefinite increase in intracellular Ca2+ (Jensen and Rehder, 1991).

3.3 Inhibition of mitochondrial ATP synthase

F1F0 ATP synthase transforms energy from the proton electrochemical gradient into the phosphoric acid anhydride bond of ATP (Kaim and Dimroth, 1999; Mitchell, 1961). The F1F0 ATP synthase is located within the inner mitochondrial membrane and protrudes into the matrix space. It consists of the catalytic F1 part and the F0 subunit, which spans the inner mitochondrial membrane and forms a proton channel (Fig. 1B) (for details on the complex interaction of the two subunits see: (Elston et al., 1998; Stock et al., 2000)). Under normal physiological circumstances the H+ ions, which are transported out of the mitochondria via electron transport, then reenter the mitochondrial matrix through the F0 channel of the F1F0ATP synthase (complex V), to generate ATP (Fig. 1B).

Inhibition of the F1F0ATP synthase can be achieved either directly or indirectly. Indirect inhibition of the ATP synthase occurs in response to mitochondrial uncouplers, which collapse the proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane and hence deprive ATP synthase of its driving force. Under these conditions the enzyme complex may reverse its direction of operation, hydrolyzing ATP rather than synthesizing it. This response is assumed to stabilize the ? ? m, prevent mitochondrial swelling and thus assure mitochondrial function (Duchen, 1999; Nicholls and Budd, 2000), for at least as long as glycolysis can keep up with the increased ATP demand.

Direct inhibition of the ATP synthase can be achieved by the antibiotics oligomycin and venturicidin, as well as by the covalently binding inhibitors N,N’-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCCD) and dibutylchloromethylin chloride (Cain et al., 1977; Penefsky, 1985). All of these compounds interact with the F0 subunit and block the proton flux across the inner mitochondrial membrane (Penefsky, 1985). As a result of the decreased H+ conductance in response to these ATP-synthase inhibitors, mitochondria become hyperpolarized (as indicated by the monitoring of ?? m by e.g., Rh123) (Duchen and Biscoe, 1992; Schuchmann et al., 2000).

Four independent inhibitory sites have been identified recently for the catalytic F1 complex of the ATP-synthase. These sites can be targeted by a variety of covalent inhibitors, non-hydrolysable substrate analogs as well as the natural inhibitor protein IF1 [for review see: (Gledhill and Walker, 2005)]. Under physiological conditions the latter inhibitor protein prevents ATP hydrolysis by the catalytic F1 subunit. IF1 binds to the F1 complex in a 1:1 stoichiometry when cytosolic/mitochondrial acidification occurs in response to metabolic insults or mitochondrial uncoupling (Gledhill and Walker, 2005; Walker, 1994).

The mitochondrial fluorescence marker rhodamine 6G, as well as other structurally related lipophilic cations, can block the F1 subunit (Gledhill and Walker, 2005), which may prove problematic when these dyes are used as mitochondrial markers. This binding may explain the known impairment of mitochondrial respiration by higher concentrations of these mitochondrial markers (see section 5.1.) (Emaus et al., 1986; Scaduto and Grotyohann, 1999).

Since the ATP synthase is not directly linked to the respiratory chain, its inhibition by either of the above-mentioned compounds leaves mitochondrial respiration intact. Therefore, ATP synthase inhibition is an elegant approach to block mitochondrial ATP synthesis, avoiding interference with either mitochondrial respiration per se or maintenance of the ?? m. Other mitochondrial functions such as Ca2+ sequestration, also remain intact. It should be kept in mind, however, that under these conditions glycolysis remains the only source available for ATP production, which, depending on the cell type, its specific ATP demand, glycolytic capacity and glucose availability, may be insufficient to ensure undisturbed cell function.

When performing experiments on mitochondrial function, inhibition of ATP synthase may be desirable when protonophores are applied. In the presence of protonophores alone, ATP synthase may revert to the reversed mode, leading to the hydrolysis of ATP, and thereby worsening the metabolic status of the cell, since the cell also utilizes ATP derived from glycolysis (Duchen, 1999; Nicholls and Budd, 2000). Therefore, oligomycin should be applied to prevent the reversal of the ATP synthase in combination with protonophores to elucidate the true tissue response to mitochondrial depolarization. Although oligomycin is the most widely used compound to inhibit ATP synthase, we occasionally found that it precipitated in experiments performed with carbogen-aerated solutions and at temperatures in the physiological range (35–36°C), questioning its ability to penetrate into tissues.

In other studies, oligomycin was used to assess the effects of the ATP synthase on ΔΨm during focal cerebral ischemia (Takeda et al., 2004). Following the onset of ischemia, the time taken for anoxic depolarization (or hSD) to occur (indicated by a negative extracellular DC voltage deflection) in oligomycin treated rats was shorter than in the control group. The rapid decrease in ΔΨm prior to extracellular DC voltage deflection in the oligomycin group was attributed to a decrease in the mitochondrial proton pump following tissue O2 depletion. This finding suggests that the ΔΨm cannot be maintained without the reversed functioning of the ATP synthase. However, the extracellular DC potential following ischemia was lower in the control group, suggesting that the reversed functioning of the ATP synthase caused depletion in ATP, which compromised the DC potential (Takeda et al., 2004).

The application of oligomycin has also been used to investigate the relationship between mitochondrial ROS production, the NAD(P)H redox state and membrane potential in isolated brain mitochondria. Inhibition of the ATP synthase by the administration of oligomycin resulted in an increase in ROS generation and reduction of the NAD(P)H redox state, indicating that ROS generation is redox regulated (Starkov and Fiskum, 2003).

Oligomycin has often been used in conjunction with other mitochondrial inhibitors or protonophores to investigate various functions of mitochondria. For example, the co-administration of oligomycin (10 μM) with rotenone (5 μM) following stimulation with glutamate and glycine in cultured neurons caused a significant increase in mitochondrial membrane depolarization (measured using the fluorescent dye JC-1) compared to the application of glutamate alone (there was no significant membrane depolarization following oligomycin and rotenone treatment alone either). In addition, these inhibitors potentiated glutamate-induced increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations by blocking mitochondrial function and therefore Ca2+ uptake. However, in contrast to FCCP (750 nM), which significantly blocked neuronal toxicity as a result of glutamate stimulation, oligomycin and rotenone enhanced toxicity and caused irreversible inhibition of mitochondrial function (Stout et al., 1998).

It has also been shown that the addition of oligomycin to granule cells treated with glutamate and either DNP or CN− eliminates the [Ca2+]i plateau produced by DNP or CN−. In parallel experiments, the addition of DNP or CN− significantly potentiated the decrease in intracellular ATP following glutamate stimulation, whereas treatment with oligomycin weakened the effect produced by DNP and CN− (Khodorov et al., 2002).

3.4 Inhibitors of mitochondrial permeability transition (mPT)

The induction of the mPT represents the opening of a non-specific (voltage sensitive) proteinaceous pore. The mPTP has a diameter that allows molecules up to a molecular weight of ~1500 D to equilibrate across the mitochondrial membrane. Several proteins have been implicated in the formation and/or regulation of the mPTP. These include a voltage dependent anion channel (VDAC), intermembrane protein (creatinine kinase), adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT), cyclophilin D (CPD), and the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor, which are located in the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes (Fig. 1B, C). Furthermore, Bcl2 family proteins located in the outer membrane are involved either directly or indirectly (Crompton, 1999). The induction of mPT is facilitated by anoxia, loss of ATP, depletion of NAD(P)H, increased production of ROS, and dissipation of the negative ?? m (Almeida and Bolanos, 2001; Halestrap et al., 1997; Kristian, 2004; Simbula et al., 1997). In turn, the induction of mPT can lead to the uncoupling of the electron respiratory chain, the collapse of ?? m, as well as the efflux of both small molecules (Ca2+ and NAD+/NADH) and small proteins from the mitochondria (Halestrap et al., 2002).

Depending on the cell condition mPT has also been associated with the initiation of cell death, which can occur either by necrosis or apoptosis. Cells will undergo death by necrosis if the induction of mPT is associated with the depletion of ATP and disruption of the integrity of the plasma membrane, indicating loss of mitochondrial function. In contrast, if ATP levels are maintained, a more regulated induction of mPT may activate the apoptotic process over hours to days, which requires ATP formation for many of the programmed cell death states (Kroemer et al., 1998; Murphy et al., 1999).

The induction of mPT can be inhibited by endogenous factors, such as an elevated NAD(P)H/NAD(P) ratio; high levels of ADP or ATP; extramitochondrial Mg2+ and highly negative ?? m; and by pharmacological agents such as cyclosporin A (CsA), rasagiline, minocycline, and melatonin (Jemmerson et al., 2005). The ability of the immunosuppressive agent CsA to prevent or delay the induction of mPT was first postulated in in vivo and in vitro studies, where the application of CsA prevented both cell damage and the dissipation of ?? m induced by ischemia (Kroemer et al., 1998). CsA interferes with the induction of mPT by binding to cyclophilin D in the mitochondrial matrix. This binding prevents the interaction of cyclophilin D with ANT and the conversion of ANT into a pore (Crompton, 1985; Woodfield et al., 1998).

Cyclosporin A has been used in various preparations to further investigate the roles and regulation of the mPT. In isolated mitochondria, the induction of mPT is usually determined by detecting the absorbance decrease associated with mitochondrial swelling, using a spectrophotometer. Studies using isolated liver mitochondria have shown that CsA (0.5 μM) inhibits the release of GSH and the large amplitude swelling induced by Ca2+ (70 μM) and Pi (3 mM). Consequently, CsA also prevents the depletion of ATP, and the oxidation and release of NAD+ and NADP+ (Reed and Savage, 1995).

The ability of CsA to inhibit mPT is dependent on Ca2+ concentrations within the particular mitochondrial population. For example, CsA is less effective at preventing mitochondrial swelling induced by Ca2+ and Pi in brain mitochondria, as compared to liver mitochondria (Kristal and Dubinsky, 1997). In purified brain mitochondria CsA (1 μM) blocked mitochondrial swelling induced by Ca2+ (0.3 μmol/mg protein), but larger Ca2+ concentrations (0.6 μmol/mg protein) overcame CsA inhibition in the striatum. In contrast, the application of ADP (100 μM), another potent mPT blocker was able to block the Ca2+ induced mitochondrial swelling and depolarization in both types of mitochondria (Brustovetsky et al., 2003). ADP inhibits mitochondrial swelling probably by binding to multiple sites involved in the formation of the mPTP, such as the ANT, CsA binding protein and the Ca2+ uniporter (Brustovetsky et al., 2003; Brustovetsky and Dubinsky, 2000). In addition, the protocol used for mitochondrial isolation could alter the effect of CsA on mPT induction. For example, if digitonin is added to the buffer during the mitochondrial isolation to dissolve synaptosomes, the Ca2+ induced mitochondrial swelling is rendered insensitive to CsA inhibition.

To monitor the induction of mPT in cell culture or in situ, changes in ?? m were measured using fluorescent dyes such as tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester (TMRE), JC-1 and Rh123 that can be selectively loaded in the mitochondria (see 5.1 for a more detailed discussion of these probes). CsA (1 or 25 μM) administered with ADP prevented Ca2+ –induced mitochondrial swelling in cultured astrocytes loaded with JC-1 (Kristal and Dubinsky, 1997). In cultured oligodendrocyte progenitor cells loaded with TMRE, CsA and its analogue methylvaline-4- CsA (5–10 μM) were able to prevent ?? m dissipation and cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations induced by glutamate agonists (Smaili and Russell, 1999). In contrast, in hippocampal slices in which mitochondria were loaded with rhodamine-123, CsA (10 μM) failed to prevent slow mitochondrial depolarization during seizure-like activity indicating that mPT did not contribute to the seizure-associated mitochondrial depolarization (Kovacs et al., 2002). This result suggested that mitochondrial depolarization may not always be indicative of mPT induction.

The induction of the mPT can be more suitably monitored in living neurons with a voltage independent method by measuring fluorescence changes in calcein-loaded mitochondria. Selective mitochondrial labeling can be achieved after quenching calcein fluorescence in the cytoplasm with 1 mM CoCl 2 (Gillessen et al., 2002), Intact mitochondria are impermeable to cobalt and therefore retain calcein fluorescence; however, during induction of mPT, Co2+ enters the mitochondria and quenches calcein fluorescence. Since this technique is specific for mPTP, it is often used in parallel with mitochondrial voltage sensitive dyes to validate mPTP opening (Mironov et al., 2005). This method demonstrated that mPT induced by Mg2+or by ammonia in cultured astrocytes double labeled with calcein and TMRE, can be prevented indirectly with compounds that reduce ROS formation such as SOD (25 U/ml), vitamin E (250 μM), and Fe2+chelator deferoxamine (DFX, 40 μM), suggesting a role for ROS in the induction of mPT (Rao and Norenberg, 2004).

The induction of mPT by microtubule-acting drugs (taxol and nocodazole) was confirmed using the calcein/Co2+ imaging technique in cultured brain stem pre-Bötzinger complex neurons and in isolated brain mitochondria (Mironov et al., 2005). Apparently, the drugs’ mechanisms involved modification of the interaction between the microtubule and the outer mitochondrial membrane (Mironov et al., 2005). Interestingly, another mPTP blocker 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) (100 μM) was more effective than CsA in reducing the dissipation of ?? m induced by nocodazole in intact cells (Mironov et al., 2005). 2-APB prevents Ca2+ induced mPTP in non-synaptosomal brain mitochondria, in the presence of physiological concentrations of ATP (3 mM) and Mg2+. Under these conditions, 2-APB prevents the transition from a low to high conductance of mPTP and reduces Ca2+-induced release of cytochrome c and pyridine nucleotide from the mitochondria (Chinopoulos et al., 2003)

4. Fluorescence-labeling of mitochondria

4.1 MitoTracker® probes

MitoTracker® probes demonstrate binding to and fluorescent labeling of mitochondria. These probes mainly serve to mark mitochondrial structures, without yielding detailed functional information regarding dynamic changes in mitochondrial metabolism or membrane potential (Poot et al., 1996). MitoTracker® dyes are available for various excitation and emission wavelength ranges, spanning from green to orange to red, and have been used by us for both one- and multiphoton excitation (see the manufacturer’s webpage for details on the chemical structure: http://probes.invitrogen.com/handbook/print/1202.html). Due to their rapid membrane permeability, mitochondrial labeling is easily performed by simple cell/tissue incubation. MitoTracker® dyes label functional mitochondria only, since their specific accumulation partly depends on an intact ?? m. Once reaching the mitochondria they bind covalently to peptidergic sulfhydryl groups (Buckman et al., 2001).

One advantage of the MitoTracker® dyes is that they are considered to be less sensitive to photobleaching than the rhodamine derivatives, since they are robust fluorescent chromophores (Poot et al., 1996). Furthermore, they are stable during fixation, and are therefore valuable tools for double-label immunofluorescent studies (Stamer et al., 2002; Wozniak et al., 2005).

In addition, MitoTracker® dyes can be used to determine the mitochondrial content of a cell. This approach was used to verify that Alzheimer’s disease is correlated with a reduction of mitochondrial mass as determined in postmortem temporal lobe tissue (de la Monte et al., 2000). As demonstrated in primary cultures of forebrain neurons and astrocytes as well as endothelial and fibroblast cell lines, mitochondrial depolarization (induced by either uncoupling or respiratory chain inhibition) may interfere with MitoTracker® labeling, suggesting that the labeling remains partially dependent on mitochondrial integrity (Buckman et al., 2001; Poot et al., 1996). Nevertheless, these probes are effective tools for the tracking of mitochondria or the determination of cellular mitochondrial content, as has been shown in cultured rat hippocampal neurons and chick retinal ganglion cells (Stamer et al., 2002). MitoTracker® compounds have even been used in in vivo studies. Intracerebral injection of MitoTracker® green and a redox-sensitive MitoTracker® (MitoTracker® red CM-H2XRos) was used in animal models of neurodegenerative disorders to localize and quantify the generation of mitochondrial free radical production in rat striatal neurons after ischemia, elevated Fe2+ levels and application of 3-NPA (Kim et al., 2002).

4.2 Transfection with fluorescent proteins