Abstract

The 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of Klebsiella spp., including Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae, Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis, Klebsiella oxytoca, Klebsiella planticola, Klebsiella terrigena, and Klebsiella ornithinolytica, were characterized, and the feasibility of using ITS sequences to discriminate Klebsiella species and subspecies was explored. A total of 336 ITS sequences from 21 representative strains and 11 clinical isolates of Klebsiella were sequenced and analyzed. Three distinct ITS types—ITSnone (without tRNA genes), ITSglu [with a tRNAGlu (UUC) gene], and ITSile+ala [with tRNAIle (GAU) and tRNAAla (UGC) genes]—were detected in all species except for K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis, which has only ITSglu and ITSile+ala. The presence of ITSnone in Enterobacteriaceae had never been reported before. Both the length and the sequence of each ITS type are highly conserved within the species, with identity levels from 0.961 to 1.000 for ITSnone, from 0.967 to 1.000 for ITSglu, and from 0.968 to 1.000 for ITSile+ala. Interspecies sequence identities range from 0.775 to 0.989 for ITSnone, from 0.798 to 0.997 for ITSglu, and from 0.712 to 0.985 for ITSile+ala. Regions with significant interspecies variations but low intraspecies polymorphisms were identified; these may be targeted in the design of probes for the identification of Klebsiella to the species level. Phylogenetic analysis based on ITS regions reveals the relationships among Klebsiella species similarly to that based on 16S rRNA genes.

The genus Klebsiella is generally classified into seven species and subspecies, including Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae, Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis, Klebsiella oxytoca, Klebsiella planticola, Klebsiella terrigena, and Klebsiella ornithinolytica (30, 40). Pathogenic Klebsiella strains belonging to K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae and K. oxytoca are known to cause hospital-acquired infections such as septicemia, pneumonia, and urinary tract and soft tissue infections (35, 36, 39). As a cause of nosocomial infection due to gram-negative bacteria, Klebsiella ranks next to Escherichia coli, accounting for 8% of endemic hospital infections and 3% of epidemic outbreaks (3, 41). Recently, strains of K. planticola and K. terrigena, initially regarded as “environmental” isolates, were also isolated from human clinical specimens and animals (6, 42). Meanwhile, the appearance of multiresistant strains among clinical Klebsiella isolates, especially those producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs), which show resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins, has been increasing over the past several years (10, 31). Frequencies as high as 40% have been reported in some regions, and the available data suggest a further increase in the incidence of ESBL-producing isolates (10, 23, 31, 34). Therefore, nosocomial-infection surveillance is necessary in order to collect data that can be used in the prevention and control of Klebsiella infection (8, 20).

In clinical microbiology laboratories, Klebsiella strains are currently identified by using automated instruments based on classical biochemical tests such as the Vitek and API systems. Identification to the species level is often difficult, because some of the species share similar biochemical profiles (11, 26). For example, K. planticola and K. terrigena are generally misidentified as K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae or K. oxytoca in most automated-instrument identification systems (42). Also, K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae and K. oxytoca cannot be differentiated by classical phenotypic approaches (5, 21, 28). However, a recent study by Hansen et al. suggested that it is possible to differentiate K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae from K. oxytoca with 18 biochemical tests (16). A number of DNA-based methods for the detection of pathogenic Klebsiella spp. have been developed, including PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis based on the gyrA gene (18), fluorescent in situ hybridization and real-time PCR based on the 16S rRNA gene (19), and fluorescent in situ hybridization based on the ESBL gene for detection of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae (31).

The rRNA genes (16S, 23S, and 5S) are ideal candidates for bacterial identification and evolutionary studies, because they are highly conserved within the species (15). The major disadvantage of these sequences is that the “variable” regions are not sensitive enough to allow clear differentiation of closely related microorganisms (32). The 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequence, which is not subject to the same selective pressure as the rRNA genes and consequently has a 10-times-greater evolution rate, appears to be able to overcome the apparent limitation of rRNA genes (2, 14). Sequence and length polymorphisms found in the ITS are increasingly being used as tools for bacterial species and subspecies identification (17, 27, 29, 37), typing (25, 37), and evolutionary studies (1, 12, 33). Gürtler et al. reported that ITS sequence analysis is complementary to the 16S rRNA gene for phylogenetic analysis (13). A PCR method based on ITS sequences has been developed for the detection and identification of K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae (22, 24). Information related to ITS regions in Klebsiella is still lacking, with only 1 ITS sequence from K. oxytoca and 21 ITS sequences from nine K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae strains available in GenBank.

In this study, we sequenced 336 ITS sequences from 21 representative strains and 11 clinical isolates covering all seven Klebsiella species and subspecies. Three distinct ITS types—ITSnone (without tRNA genes), ITSglu [with the tRNAGlu (UUC) gene], and ITSile+ala [with tRNAIle (GAU) and tRNAAla (UGC) genes]—were detected. The sequence and length polymorphisms of the ITS regions were analyzed. Phylogenetic analyses based on ITS regions were also carried out. This is the first detailed assessment of ITS regions in the genus Klebsiella. Sequences in the ITS regions with significant interspecies variations and low intraspecies polymorphisms may be targeted to develop probes for the identification of Klebsiella strains to the species or subspecies level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and cultivation conditions.

The Klebsiella strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains were grown in LB medium at 37°C overnight with shaking.

TABLE 1.

The three ITS types and intraspecies identities

| Species and straina | ITSnone

|

ITSglu

|

ITSile+ala

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (bp) | Intraspecies identity | Size (bp)e | Intraspecies identity | Size (bp)e | Intraspecies identity | |

| K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae | ||||||

| ATCC 10031b | 198 | /c | 343 | / | 427, 435 | /, 0.958 |

| NCTC5056 | 198 | 0.984 | 343, 351 | 0.994, 0.937 | 427, 498 | 0.988, 0.813 |

| NCTC204 | 198 | 0.984 | 343, 351 | 1.000, 0.943 | 427 | 0.990 |

| CMCC46102 | 198 | 0.979 | 343 | 0.991 | 427, 434, 437 | 0.985, 0.956, 0.945 |

| CMCC46112 | 194 | 0.949 | 343, 352 | 0.991, 0.931 | 424, 436 | 0.967, 0.949 |

| CMCC46109 | 198 | 0.984 | 343 | 0.991 | 427 | 0.990 |

| CMCC46108 | 198 | 0.984 | 343, 351 | 0.991, 0.940 | 427 | 0.988 |

| ACCC10084 | 198 | 0.979 | 339, 352 | 0.970, 0.940 | 424, 436 | 0.967, 0.947 |

| G1746 | 198 | 0.979 | 337, 343, 351 | 0.976, 0.997, 0.940 | 429 | 0.972 |

| G1747 | 198 | 0.984 | 339 | 0.979 | 422, 429 | 0.971, 0.974 |

| G1748 | 198 | 0.984 | 343, 351 | 0.988, 0.985 | 427, 498 | 0.990, 0.809 |

| G1749 | 198 | 0.979 | 343 | 0.991 | 429 | 0.974 |

| G1750 | 198 | 0.984 | 343 | 0.982 | 427 | 0.985 |

| G1751 | 194 | 0.949 | 339, 352 | 0.934, 0.967 | 427, 495 | 0.989, 0.805 |

| G1752 | 198 | 0.969 | 343 | 0.982 | 429 | 0.969 |

| G1753 | 198 | 0.984 | 343 | 0.979 | 427 | 0.988 |

| G1754 | 198 | 0.994 | 339, 343 | 0.973, 0.994 | 426 | 0.953 |

| G1756 | 198 | 0.994 | 343, 351 | 0.991, 0.948 | 427 | 0.985 |

| K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae | ||||||

| ATCC 11297b | 198 | / | 343 | / | 427 | / |

| CMCC46110 | 198 | 1.000 | 343 | 0.997 | 427 | 1.000 |

| CCM5792 | 198 | 0.994 | 339, 343 | 0.979, 0.991 | 429, 498 | 0.979, 0.819 |

| K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis | ||||||

| ATCC 13884b | N/Ad | N/A | 343 | / | 498 | / |

| CMCC46111 | N/A | N/A | 343 | 1.000 | 498 | 1.000 |

| K. oxytoca | ||||||

| ATCC 49473b | 206 | / | 352 | / | 512 | / |

| ATCC 700324 | 206 | 0.985 | 352 | 0.988 | 512 | 0.984 |

| ATCC 49334 | 206 | 0.961 | 351, 352 | 0.867, 0.991 | 508, 510 | 0.912, 0.962 |

| CCM1900 | 206 | 0.961 | 351, 352 | 0.870, 0.980 | 508, 510 | 0.912, 0.968 |

| G1755 | 206 | 1.000 | 352 | 0.988 | 509, 511 | 0.982, 0.925 |

| K. terrigena CCM3568b | 232 | / | 376, 388 | /, 0.948 | 540, 542 | /, 0.974 |

| K. planticola CCM4428b | 232 | / | 379 | / | 535, 542 | /, 0.928 |

| K. ornithinolytica | ||||||

| ATCC 31898b | 233 | / | 379 | / | 539 | / |

| CCM4873 | 232 | 0.995 | 379 | 0.997 | 539 | 0.983 |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; NCTC, National Collection of Type Cultures, United Kingdom; CCM, Czech Collection of Microorganisms, Czech Republic; CMCC, National Center for Medical Culture Collection, China; ACCC, Agricultural Culture Collection of China; The strains with G numbers are clinical isolates from the General Hospital of Tianjin Medical University, Tianjin, China.

Representative strain for interspecies variation and phylogenetic analysis.

/, the ITS was used as the reference for the calculation of identity levels.

N/A, not applicable; K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis has no ITSnone.

Two or three different sizes were detected for one type of ITS.

DNA isolation.

Genomic DNA from each strain was extracted from 1.0 ml of the overnight culture (approximately 109 CFU) using the Tiangen DNA extraction kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd., China) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Amplification of ITS regions.

Primers wl-5793 (5′-TGT ACA CAC CGC CCG TC-3′) and wl-5794 (5′-GGT ACT TAG ATG TTT CAG TTC-3′), designed based on the most conserved sequences at the end of the 16S rRNA gene and at the beginning of the 23S rRNA gene in Klebsiella, respectively, were used to amplify ITS regions from all Klebsiella strains. The PCR mixture used contained 1× PCR buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3]), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1.0 U Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Biotechnology [Dalian] Co. Ltd., China), 10 nM each primer, and 100 ng of the DNA template in a final volume of 50 μl. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. An aliquot (2 μl) of PCR products was run in an agarose gel to check for amplified fragments.

Cloning and sequencing.

PCR amplicons were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, MA) and transformed into Escherichia coli DH5-α. Transformants, indicated by white colonies on an ampicillin plate containing isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal), were selected randomly. Plasmid DNA was isolated by the conventional alkaline-lysis method, digested with EcoRI, and visualized on agarose gels to confirm the insertion. The presence of the correct insert was verified by sequencing using an ABI 3730 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Seven to 16 transformants per strain were examined in order to reveal all possible amplicons.

Sequence analysis.

Multiple-sequence alignment of ITS sequences was carried out with the CLUSTAL W program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/). The identity level was calculated using BioEdit software (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/page2.html). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method and plotted with the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software package (version 3.1; http://www.megasoftware.net). Bootstrap analysis was carried out based on 1,000 replicates.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Klebsiella ITS sequences were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers EU623084 to EU623419.

RESULTS

Amplification of the ITS.

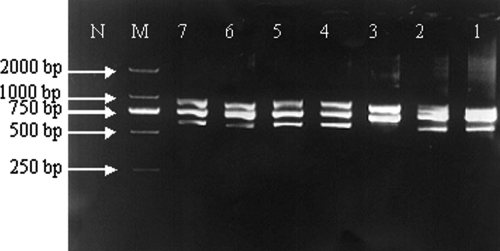

To design the primers for the PCR amplification of Klebsiella ITS regions, all the available 16S and 23S rRNA gene sequences of the genus in the the Ribosomal Data Project (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/) and NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) databases, including 102 16S rRNA gene sequences and 31 23S rRNA gene sequences, were downloaded. Based on the most conserved regions in the 16S and 23S rRNA genes, primers wl-5793 (5′-TGT ACA CAC CGC CCG TC-3′) and wl-5794 (5′-GGT ACT TAG ATG TTT CAG TTC-3′) were designed. The primers were used to amplify ITS regions from all 32 Klebsiella strains used in this study. PCR products with estimated sizes of 550, 750, and 900 bp (including 152-bp 16S rRNA and 209-bp 23S rRNA gene sequences) were detected from all K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae, K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae, K. oxytoca, K. terrigena, K. planticola, and K. ornithinolytica strains tested, and PCR products with estimated sizes of 750 and 900 bp were detected from K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis strains (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Amplification of Klebsiella ITS regions. Lanes: 1, K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae ATCC 10031; 2, K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae ATCC 11297; 3, K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis ATCC 13884; 4, K. terrigena CCM3568; 5, K. planticola CCM4428; 6, K. oxytoca ATCC 49473; 7, K. ornithinolytica ATCC 31898; M, DL2000 ladder; N, no template.

Sequence analysis.

PCR products were cloned into E. coli, and 7 to 16 clones per Klebsiella strain were sequenced in order to reveal all possible amplicons. A total of 336 sequences were obtained, and the ITS regions were analyzed using tRNA-ScanE software (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE/). Three distinct ITS types were identified: ITSnone (without tRNA genes), ITSglu [with the tRNAGlu (UUC) gene], and ITSile+ala [with the tRNAIle (GAU) and tRNAAla (UGC) genes] (Table 1). In agreement with the PCR results, the three ITS types were found in all Klebsiella species and subspecies except for K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis, which has only ITSglu and ITSile+ala. Each type of tRNA gene [tRNAGlu (UUC), tRNAIle (GAU), and tRNAAla (UGC) genes] shares 99% DNA identity within the genus.

Length polymorphisms were detected in all three ITS types; ITSile+ala was the most variable and ITSnone the least variable (Table 1). For ITSnone, 198 bp was the primary size in K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae and K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae, and 194 bp was detected in a few cases due to the deletion of four bases (TGAA) at nucleotides (nt) 178 to 181; 206 bp was detected in K. oxytoca; and 232 or 233 bp was found in K. terrigena, K. planticola, and K. ornithinolytica. For ITSglu, 343 bp was predominantly found in K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae, K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae, and K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis, and sizes as much as 9 bp different (337, 339, 351, and 352 bp) were also detected. The size of ITSglu was 351 and/or 352 bp in K. oxytoca, 376 and 388 bp in K. terrigena, and 379 bp in both K. planticola and K. ornithinolytica. Interestingly, 43 base variations were found between 351- and 352-bp ITSglu in K. oxytoca, indicating different origins for the two sequences. For ITSile+ala, 427 bp was predominantly detected in K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae and K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae, and sizes as much as 10 bp different (422, 424, 426, 429, 434, 435, 436, and 437 bp) were also detected in some cases. In addition, ITSile+ala sequences of 498 or 495 bp are also present in K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae strains NCTC5056, G1748, and G1751 and in K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae strain CCM5792 due to the insertion of 70 bp at nt 153. ITSile+ala sequences of 498 bp in K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis, 508 to 512 bp in K. oxytoca, and 535 to 542 bp in K. terrigena, K. planticola, and K. ornithinolytica were also detected.

Intraspecies conservation of ITS regions.

Apart from insertions or deletions, ITS sequences are highly conserved within the species/subspecies, with identity levels ranging from 0.961 to 1.000 for ITSnone, 0.967 to 1.000 for ITSglu, and 0.968 to 1.000 for ITSile+ala (Table 1). Insertion and/or deletion of nucleotide blocks is the cause for lower identity levels (less than 0.910) in some cases, except for ITSglu in K. oxytoca, in which the low identity (0.870) between the ITSglu sequences of 351 and 352 bp was due to the 43-bp variations.

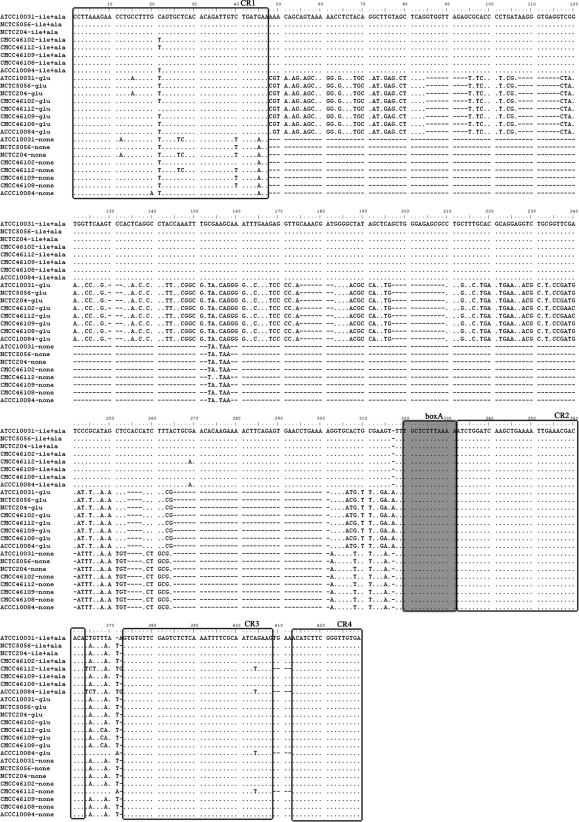

The alignment of 24 sequences representing all amplicons of the three ITS types from eight representative K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae strains revealed four conserved regions located at the first 47 nt (CR1), between nt 332 and 363 (CR2), between nt 373 and 408 (CR3), and between nt 413 and 429 (CR4) (Fig. 2). The four conserved regions and the conserved boxA region also exist in other Klebsiella species (data not shown), indicating that they are conserved within the genus.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the nucleotide sequences of ITSnone, ITSglu, and ITSile+ala from eight representative K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae strains. Each sequence is labeled with the strain number and ITS type. Dots represent nucleotides conserved in all ITS sequences. Dashes indicate gaps that have been inserted to produce optimal sequence alignment. The antiterminator (boxA) sequences are boxed and shaded. Conserved regions are boxed and labeled with CR numbers.

Interspecies variations of ITS regions.

The ITS sequences from reference strains K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae ATCC 10031, K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae ATCC 11297, K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis ATCC 13884, K. oxytoca ATCC 49473, K. planticola CCM3568, K. terrigena CCM4428, and K. ornithinolytica ATCC 31898, representing each of the species or subspecies, were examined for interspecies variations. Pairwise alignment of ITS sequences revealed identity levels between species ranging from 0.775 to 0.989 for ITSnone (Table 2), 0.798 to 0.997 for ITSglu (Table 3), and 0.712 to 0.985 for ITSile+ala (Table 4). The identity levels among K. pneumoniae subspecies (0.817 to 0.997) and among K. terrigena, K. planticola, and K. ornithinolytica (0.891 to 0.994) are relatively higher, as expected, since the members in each of these groups are closely related (9). In general, the identity levels of ITS sequences among species or subspecies are lower than those of 16S rRNA gene sequences (0.966 to 0.986) (4).

TABLE 2.

Interspecies identities of ITSnone

| Speciesa | Level of ITSnone sequence identityb with:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae | K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae | K. oxytoca | K. terrigena | K. planticola | |

| K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae | |||||

| K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae | 0.989 | ||||

| K. oxytoca | 0.902 | 0.893 | |||

| K. terrigena | 0.784 | 0.775 | 0.828 | ||

| K. planticola | 0.784 | 0.775 | 0.828 | 0.943 | |

| K. ornithinolytica | 0.784 | 0.775 | 0.828 | 0.948 | 0.987 |

The sequences from representative strains (marked with note reference b in Table 1) were used to calculate identities.

Sequence identity values of ≥0.986 are shown in boldface type.

TABLE 3.

Interspecies identities of ITSglu

| Speciesa | Level of ITSglu sequence identityb with:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae | K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae | K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis | K. oxytoca | K. terrigena | K. planticola | |

| K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae | ||||||

| K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae | 0.994 | |||||

| K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis | 0.997 | 0.997 | ||||

| K. oxytoca | 0.906 | 0.906 | 0.909 | |||

| K. terrigena | 0.798 | 0.798 | 0.801 | 0.854 | ||

| K. planticola | 0.810 | 0.810 | 0.812 | 0.855 | 0.949 | |

| K. ornithinolytica | 0.815 | 0.815 | 0.817 | 0.860 | 0.944 | 0.994 |

The sequences from representative strains (marked with note reference b in Table 1) were used to calculate identities.

Sequence identity values of ≥0.986 are shown in boldface type.

TABLE 4.

Interspecies identities of ITSile+ala

| Speciesa | Level of ITSile+ala sequence identity with:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae | K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae | K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis | K. oxytoca | K. terrigena | K. planticola | |

| K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae | ||||||

| K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae | 0.985 | |||||

| K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis | 0.817 | 0.825 | ||||

| K. oxytoca | 0.771 | 0.775 | 0.882 | |||

| K. terrigena | 0.712 | 0.714 | 0.812 | 0.841 | ||

| K. planticola | 0.715 | 0.717 | 0.817 | 0.869 | 0.891 | |

| K. ornithinolytica | 0.716 | 0.717 | 0.838 | 0.841 | 0.898 | 0.922 |

The sequences from representative strains (marked with note reference b in Table 1) were used to calculate identities.

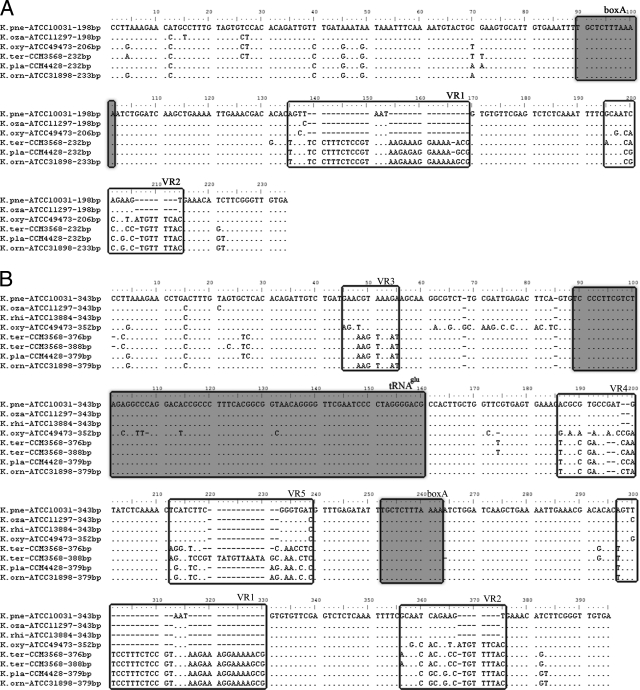

Several regions with high levels of interspecies variation were identified in each ITS type (Fig. 3A to C). Two variable regions, VR1 (135 to 169 nt) and VR2 (195 to 214 nt), located between the boxA region and the 23S rRNA gene, were found in ITSnone (Fig. 3A). Five variable regions, VR1 (297 to 330 nt) and VR2 (356 to 375 nt) between the boxA region and the 23S rRNA gene, VR3 (45 to 55 nt) between the 16S rRNA gene and the tRNA gene, and VR4 (186 to 200 nt) and VR5 (212 to 239 nt) between the tRNA gene and the boxA region, were found in ITSglu. Six variable regions, VR1 (453 to 483 nt) and VR2 (513 to 528 nt) between the boxA region and the 23S rRNA gene, VR3 (50 to 71 nt) between the 16S rRNA gene and the tRNA gene, and VR4 (154 to 229 nt), VR5 (232 to 258 nt), and VR6 (342 to 359 nt) between the tRNA gene and the boxA region, were found in ITSile+ala. Notably, all three ITS types share the same VR1 and VR2 sequences.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the nucleotide sequences of ITSnone (A), ITSglu (B), and ITSile+ala (C) from representative strains of Klebsiella species or subspecies. Each sequence is labeled with the strain number and the length. The tRNA and boxA sequences are boxed and shaded. Variable regions are boxed and labeled with VR numbers. K. pne, K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae; K. oza, K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae; K. rhi, K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis; K. oxy, K. oxytoca; K. ter, K. terrigena; K pla, K. planticola; K. orn, K. ornithinolytica.

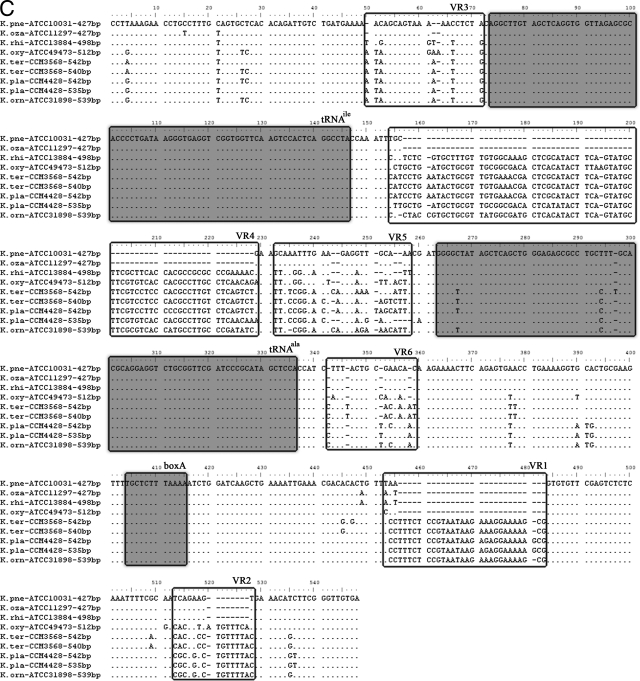

Phylogenetic analysis.

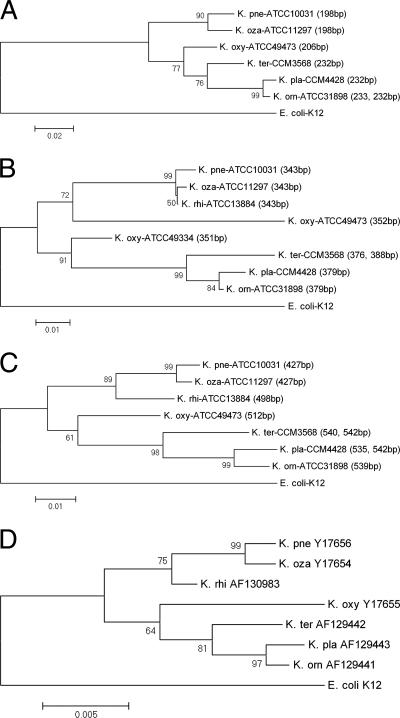

Three phylogenetic trees were constructed based on the ITSnone, ITSglu, and ITSile+ala sequences of Klebsiella, respectively (Fig. 4A to C). In all cases, K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae, K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae, and K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis form one branch, while K. terrigena, K. planticola, and K. ornithinolytica form another branch, as in the tree constructed on the basis of 16S rRNA genes (Fig. 4D). The ITSnone-based tree reveals not only topology but also bootstrap values similar to those of the 16S rRNA gene tree, except for the absence of ITSnone in K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis (Fig. 4A). However, the positions of K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae differ in the ITSglu and 16S rRNA gene trees. In the ITSglu tree, K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae is close to K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis, while in the 16S rRNA gene tree, it is close to K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae. Also, K. oxytoca clusters with the K. pneumoniae group based on the 352-bp sequence but with the K. terrigena group based on the 351-bp ITSglu sequence (Fig. 4B). The latter grouping is similar to that of the trees constructed based on the 16S rRNA gene, ITSnone, and ITSile+ala, further indicating that the two ITSglu sequences originated from different ancestors and that the 351-bp sequence is more conserved in Klebsiella. The ITSile+ala tree (Fig. 4C) fits well with the 16S rRNA gene tree; therefore, the ITSile+ala sequences may be a useful tool for phylogenetic delineation of genetic relationships in Klebsiella.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic relationships of Klebsiella species inferred from the alignments of ITSnone (A), ITSglu (B), and ITSile+ala (C) in comparison with those inferred from 16S rRNA gene sequences (D). E. coli K12 is employed as the outer group reference. For each of the species or subspecies, the representative strain identified in Table 1 is used. Species and subspecies are abbreviated as explained in the legend to Fig. 3. (A to C) For ITSnone, the ITSglu sequence of E. coli K12 excluding the tRNA gene is used. The length of each selected sequence is given in parentheses. (D) GenBank accession numbers for the 16S rRNA gene sequences of K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae, K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae, K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis, K. planticola, K. terrigena, K. oxytoca, and K. ornithinolytica are given to the right of the species or subspecies abbreviation. Bootstrap values were calculated from 1,000 trees. Each number on a branch indicates the percentage of trees in which the node was supported. Bar, percent sequence divergence.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we conducted an analysis of Klebsiella ITS regions and identified three types of ITS sequences: ITSnone, ITSglu, and ITSile+ala. ITSglu and ITSile+ala are commonly found in gram-negative bacteria (14, 38), but ITSnone is rarely found. We further searched all available genome sequences of Enterobacteriaceae, covering Escherichia coli, Citrobacter koseri, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Enterobacter sakazakii, Serratia spp., Yersinia spp., Erwinia carotovora subsp. atroseptica, and Edwardsiella spp., and ITSnone was found in none of the genomes. Therefore, Klebsiella appears to be the only exception in the family. The maintenance of ITSnone in Klebsiella (found in all Klebsiella spp. except for K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis) is puzzling, because the presence of any sequence without functional genes is evolutionarily disadvantageous. ITSnone was also found in a few gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, and Bacillus cereus) and gram-negative (Vibrio parahaemolyticus) bacteria (5).

The copy number of rrn operons was not studied. However, the detection of multiple (two to five) ITS sequences indicates the presence of multiple copies of the ITS regions in Klebsiella. As revealed by the partial genome sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae (http://genome.wustl.edu/genome.cgi?GENOME=Klebsiella%20), there are eight rrn operons located at equivalent loci, including three ITSile+ala sequences of 426 bp, 435 bp, and 499 bp, four ITSglu sequences of 343 bp, and one ITSnone sequence of 198 bp, consistent with our findings.

Due to the difficulties in obtaining strains of K. terrigena, K. planticola, and K. ornithinolytica, which are rarely isolated from the environment, only one or two strains from each of these species were examined in this study. Therefore, it is necessary to examine more strains of these species in future studies upon availability. However, based on the high intraspecies conservation observed in the ITS regions of K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae, K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae, and K. oxytoca, it is expected that the ITS types and sequences are also conserved in the other three species.

Recently, due to their close relationships to Klebsiella species, Enterobacter aerogenes and Calymmatobacterium granulomatis were also included in the genus Klebsiella and named Klebsiella mobilis and Klebsiella granulomatis, respectively (7, 9). Therefore, the ITS regions of K. mobilis and K. granulomatis remain to be investigated.

Sequence and length polymorphisms of ITS regions have been increasingly used as tools for the identification of bacterial species and/or subspecies. Our separate study showed that K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae and K. oxytoca, which are the most frequently isolated pathogenic Klebsiella species, can be discriminated confidently by a microarray using species-specific capture probes based on the variable regions of ITS sequences (unpublished data).

In conclusion, this study reveals that Klebsiella ITS sequences are highly conserved within the species or subspecies, while sufficient variations are present to allow differentiation between most of the species.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program) (2006BAK02A14, 2006AA06Z409, and 2006AA020703).

We thank Jinying Chen for supplying the clinical isolates.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 August 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antón, A. I., A. J. Martinez-Murcia, and F. Rodriguez-Valera. 1998. Sequence diversity in the 16S-23S intergenic spacer region (ISR) of the rRNA operons in representatives of the Escherichia coli ECOR collection. J. Mol. Evol. 4762-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry, T., G. Colleran, M. Glennon, L. K. Dunican, and F. Gannon. 1991. The 16S/23S ribosomal spacer region as a target for DNA probes to identify eubacteria. PCR Methods Appl. 151-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biedenbach, D. J., G. J. Moet, and R. N. Jones. 2004. Occurrence and antimicrobial resistance pattern comparisons among bloodstream infection isolates from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1997-2002). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 5059-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boye, K., and D. S. Hansen. 2003. Sequencing of 16S rDNA of Klebsiella: taxonomic relations within the genus and to other Enterobacteriaceae. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292495-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer, S. L., V. R. Flechtner, and J. R. Johansen. 2001. Is the 16S-23S rRNA internal transcribed spacer region a good tool for use in molecular systematics and population genetics? A case study in cyanobacteria. Mol. Biol. Evol. 181057-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brisse, S., D. Milatovic, A. C. Fluit, J. Verhoef, and F. J. Schmitz. 2000. Epidemiology of quinolone resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella oxytoca in Europe. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1964-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter, J. S., F. J. Bowden, I. Bastian, G. M. Myers, K. S. Sriprakash, and D. J. Kemp. 1999. Phylogenetic evidence for reclassification of Calymmatobacterium granulomatis as Klebsiella granulomatis comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 491695-1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordery, R. J., C. H. Roberts, S. J. Cooper, G. Bellinghan, and N. Shetty. 2008. Evaluation of risk factors for the acquisition of bloodstream infections with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species in the intensive care unit; antibiotic management and clinical outcome. J. Hosp. Infect. 68108-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drancourt, M., C. Bollet, A. Carta, and P. Rousselier. 2001. Phylogenetic analyses of Klebsiella species delineate Klebsiella and Raoultella gen. nov., with description of Raoultella ornithinolytica comb. nov., Raoultella terrigena comb. nov. and Raoultella planticola comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51925-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García San Miguel, L., J. Cobo, A. Valverde, T. M. Coque, S. Diz, F. Grill, and R. Canton. 2007. Clinical variables associated with the isolation of Klebsiella pneumoniae expressing different extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13532-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonçalves, E. R., and Y. B. Rosato. 2002. Phylogenetic analysis of Xanthomonas species based upon 16S-23S rDNA intergenic spacer sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52355-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gürtler, V. 1999. The role of recombination and mutation in 16S-23S rDNA spacer rearrangements. Gene 238241-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gürtler, V., Y. Rao, S. R. Pearson, S. M. Bates, and B. C. Mayall. 1999. DNA sequence heterogeneity in the three copies of the long 16S-23S rDNA spacer of Enterococcus faecalis isolates. Microbiology 1451785-1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gürtler, V., and V. A. Stanisich. 1996. New approaches to typing and identification of bacteria using the 16S-23S rDNA spacer region. Microbiology 1423-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutell, R. R., N. Larsen, and C. R. Woese. 1994. Lessons from an evolving rRNA: 16S and 23S rRNA structures from a comparative perspective. Microbiol. Rev. 5810-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen, D. S., H. M. Aucken, T. Abiola, and R. Podschun. 2004. Recommended test panel for differentiation of Klebsiella species on the basis of a trilateral interlaboratory evaluation of 18 biochemical tests. J. Clin. Microbiol. 423665-3669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeng, R. S., A. M. Svircev, A. L. Myers, L. Beliaeva, D. M. Hunter, and M. Hubbes. 2001. The use of 16S and 16S-23S rDNA to easily detect and differentiate common Gram-negative orchard epiphytes. J. Microbiol. Methods 4469-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonas, D., B. Spitzmuller, F. D. Daschner, J. Verhoef, and S. Brisse. 2004. Discrimination of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Klebsiella oxytoca phylogenetic groups and other Klebsiella species by use of amplified fragment length polymorphism. Res. Microbiol. 15517-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurupati, P., C. Chow, G. Kumarasinghe, and C. L. Poh. 2004. Rapid detection of Klebsiella pneumoniae from blood culture bottles by real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 421337-1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, S. Y., S. Kotapati, J. L. Kuti, C. H. Nightingale, and D. P. Nicolau. 2006. Impact of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species on clinical outcomes and hospital costs: a matched cohort study. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 271226-1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, Y., B. J. Mee, and L. Mulgrave. 1997. Identification of clinical isolates of indole-positive Klebsiella spp., including Klebsiella planticola, and a genetic and molecular analysis of their beta-lactamases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 352365-2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, Y., C. Liu, W. Zheng, X. Zhang, J. Yu, Q. Gao, Y. Hou, and X. Huang. 2008. PCR detection of Klebsiella pneumoniae in infant formula based on 16S-23S internal transcribed spacer. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 125230-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livermore, D. M., and N. Woodford. 2006. The beta-lactamase threat in Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter. Trends Microbiol. 14413-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopes, A. C., J. F. Rodrigues, M. B. Clementino, C. A. Miranda, A. P. Nascimento, and M. A. de Morais Júnior. 2007. Application of PCR ribotyping and tDNA-PCR for Klebsiella pneumoniae identification. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 102827-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maggi, R. G., B. Chomel, B. C. Hegarty, J. Henn, and E. B. Breitschwerdt. 2006. A Bartonella vinsonii berkhoffii typing scheme based upon 16S-23S ITS and Pap31 sequences from dog, coyote, gray fox, and human isolates. Mol. Cell. Probes 20128-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monnet, D., and J. Freney. 1994. Method for differentiating Klebsiella planticola and Klebsiella terrigena from other Klebsiella species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 321121-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mora, D., G. Ricci, S. Guglielmetti, D. Daffonchio, and M. G. Fortina. 2003. 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer region sequence variation in Streptococcus thermophilus and related dairy streptococci and development of a multiplex ITS-SSCP analysis for their identification. Microbiology 149807-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakagawa, T., T. Uemori, K. Asada, I. Kato, and R. Harasawa. 1992. Acholeplasma laidlawii has tRNA genes in the 16S-23S spacer of the rRNA operon. J. Bacteriol. 1748163-8165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakanishi, S., T. Kuwahara, H. Nakayama, M. Tanaka, and Y. Ohnishi. 2005. Rapid species identification and partial strain differentiation of Clostridium butyricum by PCR using 16S-23S rDNA intergenic spacer regions. Microbiol. Immunol. 49613-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orskov, I. 1984. Genus V. Klebsiella, p. 461-465. In N. R. Krieg and J. G. Holt (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 1st ed. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD.

- 31.Palasubramaniam, S., S. Muniandy, and P. Navaratnam. 2008. Rapid detection of ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in blood cultures by fluorescent in-situ hybridization. J. Microbiol. Methods 72107-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palys, T., L. K. Nakamura, and F. M. Cohan. 1997. Discovery and classification of ecological diversity in the bacterial world: the role of DNA sequence data. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 471145-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pérez Luz, S., F. Rodriguez-Valera, R. Lan, and P. R. Reeves. 1998. Variation of the ribosomal operon 16S-23S gene spacer region in representatives of Salmonella enterica subspecies. J. Bacteriol. 1802144-2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterson, L. R. 2008. Antibiotic policy and prescribing strategies for therapy of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: the role of piperacillin-tazobactam. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14(Suppl. 1)181-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Podschun, R., S. Pietsch, C. Holler, and U. Ullmann. 2001. Incidence of Klebsiella species in surface waters and their expression of virulence factors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 673325-3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Podschun, R., and U. Ullmann. 1998. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11589-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Regassa, L. B., K. M. Stewart, A. C. Murphy, F. E. French, T. Lin, and R. F. Whitcomb. 2004. Differentiation of group VIII Spiroplasma strains with sequences of the 16S-23S rDNA intergenic spacer region. Can. J. Microbiol. 501061-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roth, A., M. Fischer, M. E. Hamid, S. Michalke, W. Ludwig, and H. Mauch. 1998. Differentiation of phylogenetically related slowly growing mycobacteria based on 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer sequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36139-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahly, H., R. Podschun, and U. Ullmann. 2000. Klebsiella infections in the immunocompromised host. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 479237-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakazaki, R., K. Tamura, Y. Kosako, and E. Yoshizaki. 1989. Klebsiella ornithinolytica sp. nov., formerly known as ornithine-positive Klebsiella oxytoca. Curr. Microbiol. 18201-206. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stamm, L. V., H. L. Bergen, and R. L. Walker. 2002. Molecular typing of papillomatous digital dermatitis-associated Treponema isolates based on analysis of 16S-23S ribosomal DNA intergenic spacer regions. J. Clin. Microbiol. 403463-3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westbrook, G. L., C. M. O'Hara, S. B. Roman, and J. M. Miller. 2000. Incidence and identification of Klebsiella planticola in clinical isolates with emphasis on newborns. J. Clin. Microbiol. 381495-1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]