Abstract

SUMOylation is a form of post-translational modification shown to control nuclear transport. Krüppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) is an important mediator of cell proliferation and is primarily localized to the nucleus. Here we show that mouse KLF5 is SUMOylated at lysine residues 151 and 202. Mutation of these two lysines or two conserved nearby glutamates results in the loss of SUMOylation and increased cytoplasmic distribution of KLF5, suggesting that SUMOylation enhances nuclear localization of KLF5. Lysine 151 is adjacent to a nuclear export signal (NES) that resembles a consensus NES. The NES in KLF5 directs a fused green fluorescence protein to the cytoplasm, binds the nuclear export receptor CRM1, and is inhibited by leptomycin and site-directed mutagenesis. SUMOylation facilitates nuclear localization of KLF5 by inhibiting this NES activity, and enhances the ability of KLF5 to stimulate anchorage-independent growth of HCT116 colon cancer cells. A survey of proteins whose nuclear localization is regulated by SUMOylation reveals that SUMOylation sites are frequently located in close proximity to NESs. A relatively common mechanism for SUMOylation to regulate nucleocytoplasmic transport may lie in the interplay between neighboring NES and SUMOylation motifs.

SUMOylation is a recently identified process by which cellular and viral proteins are post-translationally modified by small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO)2 proteins (1, 2). SUMO is conjugated to proteins by a mechanism that resembles ubiquitination (1-3). SUMOylation occurs at the lysine residue and most proteins are mono-SUMOylated in vivo (1, 2). The target lysine often reside within a consensus motif ψKXE, where Ψ is a large hydrophobic residue; K, lysine; X, any amino acid; and E, an acidic residue that is primarily glutamate (1, 2). SUMOylation contributes to many protein functions, one of which is the regulation of nuclear localization (1, 2).

Nuclear accumulation of a protein is dependent on the balance between nuclear import and export. For the most part, nuclear import and export require transport receptors (4). The main nuclear export receptor is CRM1 (chromosome region maintenance 1) (4, 5). CRM1 binds to and is the receptor for the classic leucine-rich nuclear export signal (NES), which is present in various proteins for their delivery to the cytoplasm (6). NES conforms to the consensus sequence of ϕ-X1-3-ϕ-X1-3-ϕ-X-ϕ (ϕ = Leu, Ile, Val, Met, or Phe, or less frequently, Tyr) (6). The presence of regularly spaced, large hydrophobic residues, especially leucines, is the most important feature of the NES (6).

Many SUMOylated proteins are targeted to the nucleus and SUMOylation is known to regulate nuclear transport (1-3). However, the mechanism by which SUMOylation modulates this important biological event has not been clearly defined. Reports have suggested that SUMOylation facilitates nuclear localization through nuclear import (1-3). In contrast, several recent reports suggested that SUMOylation may also regulate nuclear export (7-10). Although it has been suspected that SUMOylation inhibits nuclear export by masking NESs (2), direct evidence in support of this hypothesis exists only for a viral protein, the adenovirus early region 1B (11)-55K (12). To date, no unified model for how SUMOylation regulates nuclear transport has emerged (13).

Krüppel-like factor 5 (14) is a zinc finger-containing transcription factor that regulates cell proliferation and plays important roles in normal physiology as well as pathophysiology of diseases including atherogenesis and neoplasm (15-25). It is also part of a KLF core circuitry essential to embryonic stem cell renewal (26-29). However, how KLF5 is post-translationally regulated is relatively unclear. Moreover, the mechanism that controls the nuclear localization of KLF5 is completely undefined. Although normally nuclear, recent reports have hinted that KLF5 may be localized to the cytoplasm. For example, in a subset of colorectal tumors with wild type KRAS, KLF5 is heavily localized to the cytoplasm, whereas in tumors carrying mutated KRAS, KLF5 is nuclear (23). In addition, a yeast two-hybrid screen with KLF5 as bait captured several preys that function as transport vesicle proteins, including sorting nexin 3 (30), a traffic protein associated with early endosomes (21). Thus, KLF5 may shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm, which could be associated with distinct functions.

In this report, we determine that KLF5 is SUMOylated in vivo, and this modification occurs at two specific lysine residues, Lys151 and Lys202, in the mouse sequence. We further show that a small fraction of KLF5 is localized to the cytoplasm, including structures that resemble intracellular vesicles. In close proximity to the first SUMOylation site of KLF5 is a putative NES. This leucine-rich NES matches the classic NES consensus, directs a fused GFP to the cytoplasm, binds CRM1, and is inhibited by leptomycin. Moreover, this NES activity is abolished by mutating two critical valine/leucine residues within the consensus sequence. SUMOylation facilitates nuclear localization of KLF5 and inhibits nuclear export by specifically inhibiting the NES. In addition, SUMOylation of KLF5 enhances the ability of KLF5 to stimulate anchorage-independent growth of HCT116 colorectal cancer cells. A survey of proteins that nuclear localizations are facilitated by SUMOylation reveals that SUMOylation sites and NESs are often located in close proximity to each other. This report therefore provides direct evidence that SUMOylation facilitates protein nuclear localization by inhibiting the nuclear export signal adjacent to its target site.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Constructs—KLF5 mutants were constructed with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). SUMOylation site lysine residues were replaced with arginines, and SUMOylation motif glutamate residues were replaced with alanines. The two hydrophobic residues predicted to be crucial for the NES of KLF5 were replaced with alanines. Plasmids expressing GFP fusion proteins were prepared by inserting DNA fragments encoding the indicated KLF5 peptides into the EcoRI-SalI site of pEGFPC1 (Clontech). The amounts of plasmids introduced in the transfection were adjusted for equal amounts of protein expression in the experiments. Plasmids GFP-SUMO-1, HIS-SUMO-1, and pMT3/HA-KLF5 have been described previously (15, 31-33).

SUMOylation Assays—COS-1 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and disrupted in lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Nonidet P-40, 135 mm NaCl, 20 mm N-ethylmaleimide (NEM, Sigma), and complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche)). The lysates were immunoprecipitated with a rabbit HA antibody (Sigma) for 2 h followed by incubation with EZview Red protein G affinity gel (Sigma) for 1 h. The immune complexes were washed with the lysis buffer four times and subjected to Western blotting with a mouse HA (Covance) or GFP (Roche) antibody. Alternatively, the transfected cells were disrupted by boiling in SDS lysis buffer (62.5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 8.75% glycerol, 5% 2-mecaptoethanol) containing NEM, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and aprotinin as described previously (21). Western blot analysis was performed with mouse HA (Covance), HIS (Qiagen), or β-actin (Sigma) antibodies.

Fluorescence Microscopy—COS-1 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. On the following day, cells were fixed with methanol, blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline for 1 h, and incubated overnight with a rabbit HA antibody (Sigma) followed by RRX-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Cells were also stained with Hoechst dye to reveal the nuclei. To inhibit nuclear export, cells were either mock treated or treated for 12 h with 10 ng/ml leptomycin A and B (Sigma) (34-36). For endogenous KLF5 staining, COS-1 cells were fixed with methanol, blocked with 10% horse serum, 3% BSA, and 3% nonfat dry milk for 1 h, and incubated overnight with a rabbit antibody raised against KLF5 (Santa Cruz) and a RRX-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch). For endogenous KLF5 staining after small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown, KLF5 siRNA (Invitrogen) or the corresponding negative control siRNA-transfected DLD-1 cells were fixed with 3% formaldehyde, blocked with 3% BSA and 0.02% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline, and stained with a rabbit KLF5 antibody (CeMines) and an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Molecular Probes). For endogenous co-staining of KLF5 and SNX3, COS-1 cells were fixed with methanol, blocked, and incubated overnight with a rabbit KLF5 antibody (23) and a goat SNX3 antibody (Santa Cruz), followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit and RRX-conjugated donkey anti-goat secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Cells were stained with Hoechst dye to reveal the nuclei. Fluorescence was observed under a LSM 510 laser confocal microscope (Zeiss). For the localization of GFP-LRS proteins, COS-1 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. On the next day, the cells were either mock treated or treated for 16 h with 10 ng/ml leptomycin A and B (34-36). The green fluorescence was viewed under an Eclipse TS100 inverted microscope (Nikon).

Heterokaryon Assay—Heterokaryon assay was performed as described (37-40). Briefly, COS-1 cells were transfected with HA-KLF5. Eight h after transfection, NIH3T3 cells were plated and co-cultured with the transfected COS-1 cells. Fifteen h later, the co-cultured cells were treated for one-half h with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma), which was also present throughout the following steps. Cells were then either treated with 50% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 8000 in the culture medium for 2 min to induce fusion or mock treated as the control. After three washes, the fused cells were cultured for 2 h to allow interkaryon shuttling, and fixed and stained with a chicken anti-HA antibody (Chemicon) and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated donkey anti-chicken secondary antibody. To distinguish between monkey (COS-1) and mouse (NIH3T3) nuclei, the cells were simultaneously stained with Hoechst dye. The murine nuclei were readily identified by their unique punctate pattern of fluorescence as previously described (37-40).

Small Interfering RNA—Stealth Select siRNA against human KLF5 and the corresponding negative control siRNA were obtained from Invitrogen and prepared according to the manufacturer's instruction as described (23). Cells were transfected with the siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent in Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium (Invitrogen). After transfection, the cells were either collected for subcellular fractionation and Western blotting or immunostained with a rabbit anti-KLF5 antibody.

Subcellular Fractionation—COS-1 cells were subjected to subcellular fractionation as described (41). The fractionated proteins were probed with rabbit KLF5 and mouse histone H1 (Upstate), α-tubulin (Sigma), and Na+/K+-ATPase (Millipore) antibodies. DLD-1 cells were subjected to nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation as described (42). The fractionated proteins were probed with rabbit KLF5 and mouse histone H1 (Upstate), and β-actin (Sigma) antibodies.

Immunoprecipitation—To detect binding to nuclear export receptor, COS-1 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. Two days later, cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing phosphatase inhibitors (Active Motif). Immunoprecipitation was performed with a nuclear complex co-IP kit (Active Motif) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, the lysates were blocked with horse serum and EZview protein G affinity gel (Sigma) or protein A-agarose beads (Upstate) by rocking for 2 h, and immunoprecipitated with either a mouse monoclonal CRM1 antibody (BD Transduction Laboratories) or a rabbit GFP antibody (Santa Cruz) overnight followed by incubation with BSA-blocked EZview protein G affinity gel or protein A-agarose beads for 1 h. The immune complexes were washed three times with BSA-containing IP high buffer supplemented with 2 mm NEM, salt, detergent, phosphatase inhibitors, and complete protease inhibitor mixture, and twice with IP high buffer without BSA. The precipitates were immunoblotted with goat anti-GFP (Rockland) and mouse anti-CRM1.

In Vitro SUMOylation and Binding Assays—To detect binding to CRM1 in vitro, COS-1 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. Two days later, cells were lysed, and the GFP fusion proteins were purified by immunoprecipitation with anti-GFP antibody and protein A beads. The immunoprecipitates were extensively washed with 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and 5 mm MgCl2, and resuspended in SUMOylation buffer (LAE Biotech) containing purified SUMO-1, and E1 (SAEI/SAEII) and E2 (Ubc9) enzymes (LAE Biotech). The reactions were rocked at 37 °C for 1 h, followed by incubation for 3 days with rocking at 4 °C. The samples were centrifuged and washed, and the precipitates were resuspended in lysis buffer containing 50 μm GTPγS (Sigma), purified CRM1 (Abnova) and Ran (Sigma) that have been preincubated with 10 mm GTPγS, and rocked at 4 °C overnight. The mixtures were centrifuged, and the pellets were washed three times with the BSA-containing IP high buffer, and twice with the IP high buffer without BSA. Fifty μm GTPγS was supplemented during all washing steps. The samples were immunoblotted with goat anti-GFP and mouse anti-CRM1.

Colony Formation Assay—To determine the transformation potential of KLF5 and its SUMOylation mutants, HCT116 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, and colony formation assay in soft agar was performed as described (43). Colonies were counted 3 weeks later.

RESULTS

KLF5 Is SUMOylated—KLF5 contains two highly conserved sequences that resemble the consensus SUMOylation motif, ψKXE (1, 2) (Fig. 1). We first determined whether KLF5 is SUMOylated in cells. COS-1 cells were co-transfected with HA-tagged KLF5 and GFP-tagged SUMO-1. Cell lysates were prepared in the presence of deSUMOylation inhibitor NEM (1) and immunoprecipitated with a rabbit HA antibody. Immunoblots were then performed on the immunoprecipitates with a mouse HA or GFP antibody (Fig. 2A). Three slow-migrating HA-KLF5 species were detected (Fig. 2A, lane 1, *, +, and ++). These three forms were SUMOylated as confirmed by blotting with the GFP antibody (Fig. 2A, lane 5). The slowest migrating HA-KLF5 (*) was fully SUMOylated, whereas the other two slow-migrating species (+ and ++) were partially SUMOylated (see below). Quantitative analysis of chemiluminescence showed that SUMOylated KLF5 represented on average 7.5 ± 3.8% (n = 4) of total KLF5.

FIGURE 1.

SUMOylation motifs in KLF5. A, a schematic showing the two ΨKXE SUMOylation motifs in KLF5. Shown also is the relative location of the zinc finger DNA binding domain of KLF5. B, conservation of the ΨKXE SUMOylation motifs in KLF5 from various species. The two ΨKXE motifs are located at residues 150-153 and 201-204 of mouse KLF5 (underlined).

FIGURE 2.

SUMOylation of KLF5. A, SUMOylation of KLF5 with GFP-tagged SUMO-1 and identification of the two SUMOylation lysine residues within the ΨKXE motifs. COS-1 cells were co-transfected with GFP-SUMO-1 and one of the following: pMT3/HA-KLF5 (WT), pMT3/HA-KLF5-K151R (K151R), pMT3/HA-KLF5-K202R (K202R), or pMT3/HA-KLF5-K151R/K202R (K151R/K202R). Lysates were immunoprecipitated with a rabbit HA antibody followed by Western blotting with a mouse HA (lanes 1-4) or GFP (lanes 5-8) antibody. B, SUMOylation of KLF5 with His-tagged SUMO-1 and confirmation of the two SUMOylation sites. COS-1 cells were co-transfected with HIS-SUMO-1 and pMT3/HA-KLF5 (WT), pMT3/HA-KLF5-K151R (K151R), pMT3/HA-KLF5-K202R (K202R), or pMT3/HA-KLF5-K151R/K202R (K151R/K202R). The transfected cells were disrupted by boiling in the presence of SDS and NEM and Western blot was performed with a mouse HA, His, or β-actin antibody. C, SUMOylation of endogenous KLF5. Endogenous KLF5 is SUMOylated in the presence (lane 1, HS1) or absence (lane 2) of HIS-SUMO-1 transfection. D, loss in KLF5 SUMOylation by mutation at the two essential glutamate residues within the ΨKXE motifs. COS-1 cells were co-transfected with GFP-SUMO-1 and pMT3/HA-KLF5 (WT), pMT3/HA-KLF5-E153A (E153A), or pMT3/HA-KLF5-E153A/E204A (E153A/E204A). Lysates were immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-HA followed by Western blot with mouse anti-HA (lanes 1-4) or GFP (lanes 5-8). A short exposure of the panel in lanes 5-8 is also shown. In all panels, * represents the di-SUMOylated form of KLF5; + and ++, mono-SUMOylated forms.

As an alternative method to detect SUMOylation of KLF5, we transfected COS-1 cells with HA-KLF5 and His-tagged SUMO-1 and disrupted the cells under denaturing conditions by boiling in the presence of SDS and NEM to preserve SUMOylation (1). Upon Western blotting against HA, SUMOylated KLF5 was apparent in the whole cell lysates (Fig. 2B, lane 1). Due to the smaller His tag, all three SUMOylated forms of KLF5 migrated faster than the three GFP-SUMO-1-modified counterparts although they exhibited a similar relative pattern of migration. These results confirm that KLF5 is SUMOylated.

We next determined whether endogenous KLF5 is SUMOylated. COS-1 cells were either transfected with HIS-SUMO-1 or mock transfected, and the whole cell lysates were blotted with a KLF5 antibody to reveal endogenous KLF5 (Fig. 2C). In cells transfected with His-SUMO-1, SUMOylated endogenous KLF5 was detected (Fig. 2C, lane 1). In mock transfected cells, three slow-migrating forms with slightly faster mobility than those in His-SUMO-1-transfected cells were detected (Fig. 2C, lane 2; *, +, and ++). These represent SUMOylated KLF5 by endogenous SUMO. We estimate that less than 1% of endogenous KLF5 was SUMOylated without SUMO overexpression. This is consistent with the observations that only a small percentage of a given protein, often less than 1%, is SUMOylated at steady state (1). These experiments show that the endogenous KLF5 is also SUMOylated.

Identification of the SUMOylation Sites in KLF5—We next sought to identify the sites of SUMOylation in KLF5. SUMOylation typically occurs at lysine residues within a consensus sequence ψKXE (1, 2). The lysine residues within the consensus SUMOylation motifs of KLF5 are located at amino acid positions 151 and 202 of the mouse sequence (Fig. 1). We substituted each of the two lysine residues with arginine and determined the effect of such mutation on SUMOylation of KLF5. As seen in Fig. 2A, the fully SUMOylated KLF5 (Fig. 2A, lane 1, *) was absent from cells transfected with either K151R or K202R single mutants (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 3, respectively). Instead, a single slow-migrating form of KLF5 remained in each of the single mutant-transfected cells and represented a mono-SUMOylated form of KLF5 (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 3). The slightly different electrophoretic mobility of the two mono-SUMOylated forms was probably due to a branching effect, in which SUMO conjugated closer to the center of a protein causes slower migration of the protein. This has been shown to occur in other SUMOylated proteins (44-46). The substitution of arginines for both lysines (K151R/K202R) completely abolished SUMOylation (Fig. 2A, lanes 4 and 8). Similar results were obtained when cells were co-transfected with the various SUMOylation mutants of KLF5 and His-SUMO-1 (Fig. 2B). These results identified lysine residues 151 and 202 in mouse KLF5 as the sites of SUMOylation.

Reinforcing this conclusion, loss in SUMOylation was fully reproduced by mutations at the two conserved glutamate residues within the ψKXE SUMOylation motifs, Glu153 and Glu204 (Figs. 1 and 2). The E153A mutation, like K151R, abrogated the di-SUMOylated form and one of the two mono-SUMOylated forms of KLF5 (Fig. 2D, lanes 3). The lone SUMOylated form that remained (Fig. 2D, lane 3, +) was also detected when immunoprecipitates were probed with a GFP antibody (Fig. 2D, lane 7, +). Mutation of both glutamate residues, E153A/E204A, like K151R/K202R, completely abolished SUMO-modified KLF5 (Fig. 2D, lanes 4 and 8). These results indicate that the two conserved glutamate residues within the two SUMOylation motifs of KLF5 are necessary for KLF5 to become SUMOylated, confirming that the two motifs represent bona fide sites of SUMOylation in KLF5.

KLF5 Is Localized to Both the Nucleus and Cytoplasm—Similar to other Krüppel-like factors (47), KLF5 was thought to be exclusively localized to the nucleus (48). However, we recently observed that KLF5 is localized to the cytoplasm in a subset of human colorectal cancers (23). In addition, a recent yeast two-hybrid screen for the binding partners if KLF5 identified several proteins are localized to the cytoplasm (21). These results suggest that KLF5 may be localized to the cytoplasm in addition to its predominant and traditional nuclear localization. To investigate this possibility, we performed immunofluorescence microscopy on endogenous KLF5 in COS-1 cells and detected the presence of KLF5 in the cytoplasm in addition to the nucleus in a fraction of the cells (Fig. 3A, arrows). Western blot analysis of fractionated cell extracts confirmed the presence of a small amount of KLF5 in the cytosolic and membrane factions (Fig. 3C, lanes 3 and 4, respectively).

FIGURE 3.

KLF5 is localized to both the nucleus and cytoplasm. A, localization of endogenous KLF5 to the cytoplasm in COS-1 cells. Cells were stained with a rabbit KLF5 antibody and RRX-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Cells were also stained with Hoechst dye to reveal the nuclei. The arrow shows punctate staining of KLF5 in the cytoplasm. B, immunostaining of KLF5 in DLD-1 cells. DLD-1 cells were transfected with siRNA against KLF5 or nonspecific control siRNA and subjected to immunofluorescence microscopy using a rabbit KLF5 antibody and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. The brackets indicate specific punctate localization of KLF5 in the cytoplasm. C, subcellular fractionation of KLF5 in COS-1 cells. Cell lysates were fractionated into nuclear, cytosolic, and membrane fractions. An equal amount of each fraction was subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against KLF5, histone, tubulin, and Na+/K+-ATPase. D, Western blot analysis of KLF5 in DLD-1 cells following transfection with KLF5 siRNA or control siRNA. Cell lysates were divided into cytosolic and nuclear fractions and blotted against KLF5, histone, or actin antibodies.

To lend further support to the cytoplasmic localization of KLF5, endogenous KLF5 is also present in the cytoplasm in a variety of other cell types, including the human colon cancer cell line DLD-1. This is illustrated by the immunostaining result in DLD-1 cells transfected with control siRNA (Fig. 3B, brackets). Subcellular fractionation experiments in these cells indicate that 9.2 ± 1.2% (n = 4) of total endogenous KLF5 was present in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3D, lanes 1-3). The cytoplasmic staining of KLF5 was specific as demonstrated by the significant loss of both nuclear and cytoplasmic KLF5 in DLD-1 cells that had been transfected with KLF5 siRNA (Fig. 3, B and D, lanes 2 and 4). In addition, cytoplasmic localization of endogenous KLF5 was repeatedly observed by immunostaining using two different methods of fixation in a variety of cell lines and with multiple KLF5 antibodies raised from different sources, including two commercial rabbit KLF5 antibodies (from CeMines and Santa Cruz) and two rabbit polyclonal KLF5 antibodies raised in our laboratory. Taken together, these results indicate that the cytoplasmic localization of KLF5 is specific.

We also examined the subcellular localization of exogenous KLF5 in COS-1 cells transfected with HA-KLF5. As seen in the results in Figs. 4A and 7B, similar to endogenous KLF5, HA-KLF5 was found in the cytoplasm of ∼10% of transfected cells. Notably, cytoplasmic KLF5 was heavily distributed to structures resembling intracellular vesicles (Fig. 4B). The largest of these structures had a hollow and circular staining pattern under high magnification, forming individual “rings” (Fig. 4B, arrow-heads). The cytoplasmic signal was not simply an artifact of overexpression or aggregation, because the unique staining pattern was observed in cells that HA-KLF5 was either primarily nuclear (Fig. 4B, top panels) or cytoplasmic (Fig. 4B, bottom panels). Moreover, endogenous KLF5 also displayed a similar punctate localization in the cytoplasm (Figs. 3, A and B, and 5A). Indeed, when present in the cytoplasm, KLF5 partially co-localized with SNX3 (Fig. 5, A and B), a transport vesicle protein localized to early endosomes (49). The morphological and biochemical results therefore suggest that cytoplasmic KLF5 is largely localized to intracellular vesicles.

FIGURE 4.

Localization of KLF5 to vesicle-like structures in the cytoplasm. A, COS-1 cells were transfected with HA-KLF5 and immunostained with a rabbit HA antibody followed by RRX-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Hoechst stain was used to reveal the nuclei. The arrow indicates cytoplasmic staining in some of the cells expressing HA-KLF5. B, localization of HA-KLF5 to vesicle-like structures within the cytoplasm. Two cells exhibiting either largely nuclear distribution (top panels) or extensive cytoplasmic localization (bottom panels) of HA-KLF5 are shown. Progressively higher magnifications of a selected field are shown. Staining of the specific circular structures is indicated by arrowheads.

FIGURE 7.

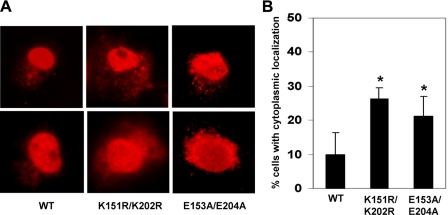

SUMOylation facilitates nuclear localization of KLF5. COS-1 cells were transfected with pMT3/HA-KLF5 (WT), pMT3/HA-KLF5-K151R/K202R (K151R/K202R), or PMT3/HA-KLF5-E153A/E204A (E153A/E204A). Twenty-four h following transfection, cells were fixed and stained with a rabbit HA antibody and RRX-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody. A, images of two representative stained cells are shown for each construct. B, quantification of the percentage of cells exhibiting cytoplasmic staining. Shown are the averages and standard deviations of four independent experiments in which 100 cells were examined per experiment. *, p < 0.05 by two-tailed t test when compared with wild type (WT).

FIGURE 5.

Co-localization of KLF5 and SNX3 in the cytoplasm. COS-1 cells were stained with rabbit KLF5 and goat SNX3 primary antibodies, followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (green) and RRX-conjugated donkey anti-goat (red) secondary antibodies, respectively. Cells were also stained with Hoechst dye to reveal the nuclei. Two cells with substantial cytoplasmic localization of KLF5 (A and B) and one cell with primarily nuclear KLF5 (C) are shown.

The presence of both endogenous and exogenous KLF5 in the cytoplasm of a fraction of cells suggests that KLF5 shuttles between the cytosol and nucleus. To test this possibility, we performed heterokaryon assays between HA-KLF5-transfected COS-1 cells and NIH3T3 fibroblasts. HA-KLF5-transfected COS-1 cells were fused to NIH3T3 fibroblasts, during which de novo protein synthesis was blocked by cycloheximide. Nuclei of the two species (monkey versus mouse) are distinguished by staining with Hoechst dye, in which mouse nuclei exhibit a more punctate pattern of fluorescence (37-40). As seen in Fig. 6A, fusion resulted in the shuttling of HA-KLF5 from the nuclei of COS-1 cells to those of NIH3T3 cells. In contrast, no such shuttling occurred in control cells without fusion (Fig. 6B). In some of the fused cells, a small amount of KLF5 was localized to vesicle-like structures in the cytoplasm (see for example, the right panel in Fig. 6A) similar to those observed for either endogenous or transfected KLF5. However, not all of the fused mouse cells had detectable KLF5 (data not shown). These results are consistent with a dynamic regulation of KLF5 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and variable cytoplasmic levels of KLF5.

FIGURE 6.

Demonstration of nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of KLF5 by heterokaryon assays. A, COS-1 cells were transfected with HA-KLF5 and fused with NIH3T3 cells in the presence of cycloheximide. Following fusion, cells were fixed and stained with a chicken HA antibody and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated donkey anti-chicken secondary antibody. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst dye. Nuclei of murine cells were identified by their distinctive punctuate pattern (arrows). B, cells were treated under identical conditions but without fusion served as control.

SUMOylation Facilitates Nuclear Localization of KLF5—We then investigated whether SUMOylation plays a role in determining the subcellular localization of KLF5. As previously reported, the most direct method to study the function of SUMOylation is mutational elimination of the SUMOylation sites, and yet the assignment of any effects to SUMOylation is more convincing if mutations at another position in the ψKXE SUMOylation motif show similar effects (1). This is because lysines may potentially serve as sites for other modifications, which may complicate functional analysis of SUMOylation. Thus, we included both K151R/K202R and E153A/E204A KLF5 SUMOylation mutants in our studies to rule out the potentially nonspecific effect. As demonstrated in Fig. 7, a higher percentage of cells transfected with either KLF5 mutant exhibited significant cytoplasmic localization when compared with wild type KLF5. In addition, co-transfection with the SUMO E2 enzyme Ubc9 increases nuclear localization of wild type KLF5, but not the SUMOylation-defective K151R/K202R and E153A/E204A mutants (data not shown). These results indicate that one of the functions of SUMOylation in KLF5 is to facilitate its nuclear localization.

Identification of a NES in KLF5 Adjacent to Its SUMOylation Site—In investigating the mechanism by which SUMOylation enhances nuclear localization of KLF5, we noticed that sequences surrounding the two SUMOylation motifs in KLF5 are highly conserved among different species and enriched in leucine residues (Fig. 8, A and B). Particularly, the leucine-rich sequence (LRS) located just before the first SUMOylation motif, designated LRS1, fully matches the typical NES consensus as indicated by the top arrow in Fig. 8A, although other patterns of consensus matching, as illustrated by the bottom arrows in Fig. 8A, are also possible. In contrast, the LRS near the second SUMOylation motif, LRS2, does not fulfill NES consensus in certain species because the hydrophobic nature of a critically spaced isoleucine residue 207 is not completely conserved (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

LRSs near the SUMOylation motifs of KLF5 and their GFP fusion constructs. Alignment of LRS1 (A) and LRS2 (B) from different species. The large hydrophobic residues (Φ) that match the NES consensus are indicated in red. The two SUMOylation motifs (SM) are underlined. Note that LRS2 lacks a conserved isoleucine (Ile207) that is critical for the NES consensus, whereas LRS1 completely matches the consensus regarding both the hydrophobic and spacing requirements as indicated by the top arrow (L/IPYSINMNVFL). Additional potential NESs that resemble the consensus sequence are shown by the two bottom arrows. C, GFP constructs linked to LRS1 or LRS2 and/or their adjacent SUMOylation motifs, SM1 or SM2, respectively. The mutated valine and leucine residues essential for the activity of LRS1 are underlined and the lysine and glutamate residues essential for KLF5 SUMOylation are also indicated (* and +).

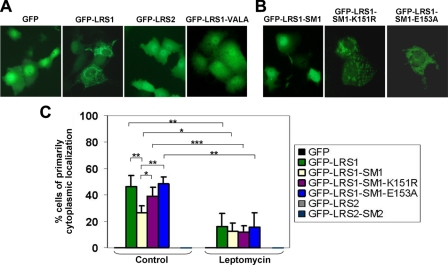

To determine whether LRS1 functions as a NES, we fused it to GFP (GFP-LRS1; Fig. 8C) and determined whether LRS1 can direct GFP from its normal distribution throughout the cell (50) to the cytoplasm. As seen in Fig. 9A, GFP-LRS1 was present largely in the cytoplasm as compared with the diffuse distribution of the GFP control in transfected COS-1 cells. Many of the GFP-LRS1-transfected cells exhibited a punctate pattern in the cytoplasm reminiscent of the localization of KLF5 in the cytoplasm (Figs. 3, 4, 5). In contrast, GFP fused to LRS2 (GFP-LRS2) displayed diffuse localization similar to GFP alone (Fig. 9A). Even peptides containing a longer part surrounding LRS2 could not redirect GFP to the cytoplasm (data not shown). Among thousands of cells counted, the cytoplasmic localization of GFP-LRS1 was not observed in any cell expressing GFP alone or the GFP-LRS2 construct. Consistent with this finding, leptomycin, a highly specific inhibitor of nuclear export (51), significantly reduced the percentage of cells having the primarily cytoplasmic localization of the GFP-LRS1 construct (Fig. 9C).

FIGURE 9.

LRS1 functions as a NES and is inhibited by SUMOylation. A, the construct containing GFP, GFP-LRS1, GFP-LRS2, or GFP-LRS1-VALA (GFP-LRS1-V127A/L129A), which contains mutation at the two residues predicted to be a critical part of the NES, was transfected into COS-1 cells, which were then visualized with an inverted fluorescence microscope. Shown are representative fluorescence images of transfected cells. B, COS-1 cells were transfected with the indicated GFP-LRS1-SM1, GFP-LRS1-SM1-K151R, or GFP-LRS1-SM1-E153A, and visualized with a fluorescence microscope. C, cells were transfected with the various constructs. Twenty-four h following transfection, cells were treated or not with 10 ng/ml leptomycin A and B for an additional 16 h. The percentages of cells with primarily cytoplasmic localization were tabulated. Shown are the averages and standard deviations of four independent experiments in which over 250 cells were examined per experiment. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 by two-tailed t test.

Additional evidence to support that LRS1 functions as a NES was provided by site-directed mutagenesis of LRS1 in the context of both GFP-LRS1 and full-length KLF5. As seen in Fig. 9A, mutation at the two predicted critical residues (Val127 and Leu129) within LRS1 (GFP-LRS1-VALA) abolished the cytoplasmic distribution of GFP-LRS1. Similarly, upon mutation of the same two residues within the full-length KLF5 (Fig. 10A, VALA), there was a significant reduction in the number of cells with cytoplasmic localization of KLF5 when compared with the wild type protein (Fig. 10, B and C). A similar reduction was observed in cells transfected with wild type KLF5 and treated with leptomycin (Fig. 10, B and C; compare WT+LM and WT). Moreover, when the two SUMOylation mutations (Fig. 7A, K151R/K202R and E153A/E204A) were combined with the NES mutation (Fig. 10A, VALA/KRKR and VALA/EAEA), neither construct was capable of significant cytoplasmic localization (Fig. 10, B and C), further confirming that LRS1 is a NES. The fact that all three mutants (VALA, VALA/KRKR, and VALA/EAEA) were expressed at similar levels as the wild type protein but were almost entirely nuclear (Fig. 10, B and C) also indicates that the observed cytoplasmic staining of wild type KLF5 was not simply due to an artifact of overexpression or protein aggregation.

FIGURE 10.

Inactivation of LRS1 by site-directed mutagenesis and inhibition of the cytoplasmic localization of KLF5 by leptomycin treatment. A, a schematic showing the various mutant constructs in the context of HA-KLF5. WT is wild type. VALA contains two point mutations substituting alanines for two residues within LRS1 predicated to be essential for NES activity (Val127 and Leu129). VALA/KRKR and VALA/EAEA are two constructs containing the NES mutation (V127A/L129A) and the two SUMOylation mutations (K151R/K202R and E153A/E204A). Numbers indicate the relative position of the residues mutated, which are marked with X. B, representative images of immunofluorescence studies of COS-1 cells transfected with the indicated constructs. LM is leptomycin. C, quantification of percentages of cells transfected with the various constructs that exhibit significant cytoplasmic staining as revealed by immunofluorescence. Shown are the averages and standard deviations of three independent experiments in which 100 cells were examined in each experiment. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 by two-tailed t test when compared with WT.

Finally, to further validate the NES nature of LRS1, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments on cell lysates from cells transfected with various constructs (Fig. 11, A-C) as well as in vitro binding assays (Fig. 11D). As seen from the results, LRS1, but not LRS2, bound to the nuclear export receptor, CRM1. Taken together, these results provide definitive evidence that LRS1, but not LRS2, is a bona fide NES in KLF5.

FIGURE 11.

Interaction of CRM1 with LRS1. A, CRM1 binds to LRS1. COS-1 cells were transfected with the indicated GFP constructs. Forty-eight h following transfection, lysates were immunoprecipitated with a mouse CRM1 antibody. Western blotting was then conducted on the immunoprecipitates using goat GFP or mouse CRM1 antibodies. B, LRS1 but not LRS2 interacts with CRM1. Lysates from COS-1 cells transfected with the indicated constructs were immunoprecipitated with a rabbit GFP antibody and probed with goat GFP or mouse CRM1 antibodies. Both long and short exposures of the GFP images in the IP panel are provided to demonstrate SUMOylation of GFP-LRS1-SM1. C, endogenous SUMOylation of GFP-LRS1-SM1. Whole lysates from COS-1 cells transfected with the indicated constructs were subjected to Western blotting with a GFP antibody. The lower panel is a short exposure of the image in the upper panel. D, in vitro SUMOylation and CRM1 binding assay. The GFP fusion proteins were purified by immunoprecipitation and in vitro SUMOylated, followed by incubation with purified Ran/GTPγS and CRM1 proteins, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The protein complexes were subjected to Western blotting with GFP and CRM1 antibodies. The asterisk indicates SUMOylated GFP-LRS1-SM1.

SUMOylation of KLF5 Inhibits Its NES Activity—Given the close proximity of LRS1 to the first SUMOylation motif in KLF5 (Fig. 8A), we examined whether the enhanced nuclear localization by SUMOylation was due to inhibition of this NES. We created a construct in GFP in which LRS1 was extended to include the first SUMOylation motif or SM of KLF5 (Fig. 8C, GFP-LRS1-SM1). As seen in Fig. 9, B and C, the cytoplasmic distribution of GFP-LRS1-SM1 was significantly less than its parental construct, GFP-LRS1. In contrast, distribution of the two SUMOylation-null mutants, GFP-LRS1-SM1-K151R and GFP-LRS1-SM1-E153A, were similar to that of GFP-LRS1 and not GFP-LRS1-SM1 (Fig. 9, B and C). The functional role of SUMOylation within the SUMOylation motif in regulating the LRS1 NES is further demonstrated by the finding that SUMOylation could be detected only in cells transfected with the GFP-LRS1-SM1 construct but not any of the other constructs containing GFP or GFP-LRS1 (Fig. 11, B-D). Theses results indicate that SUMOylation of SM1 inhibits the NES activity as directed by LRS1. It is of interest to note that SUMOylation does not reduce the binding of LRS1 to CRM1 (Fig. 11, B-D), suggesting that the inhibitory effect of SUMOylation on NES is either independent of CRM1 binding or requires additional factors.

SUMOylation Enhances the Ability of KLF5 to Stimulate Anchorage-independent Growth in HCT116 Colorectal Cancer Cells—KLF5 has been shown to enhance growth and proliferation of a variety of cell types including colorectal cancer cells (14, 16, 17, 19, 21, 23). We investigated whether SUMOylation regulates this important function of KLF5. Consistent with our recent report (23), the human colon cancer cell line, HCT116, transfected with wild type KLF5 formed more colonies in soft agar compared with vector control (Fig. 12). In contrast, both SUMO-null mutant KLF5 constructs, K151R/K202R (KRKR) and E153A/E204A (EAEA), had a significantly reduced ability to induce colony formation in soft agar when compared with wild type KLF5 (Fig. 12). These results indicate that SUMOylation selectively enhances the ability of KLF5 in stimulating anchorage-independent growth in cancer cells.

FIGURE 12.

SUMOylation enhances the ability of KLF5 to stimulate anchorage-independent growth of HCT116 colorectal cancer cells. HCT116 cells were transfected with vector alone (V), pMT3/HA-KLF5 (WT), pMT3/HA-KLF5-K151R/K202R (K151R/K202R), or pMT3/HA-KLF5-E153A/E204A (E153A/E204A) and colony formation assay in soft agar conducted as previously described (43). Colonies were counted 3 weeks following transfection. A, a representative image of the colonies formed. B, quantitative results of the averages and standard deviations of four independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; and ***, p < 0.001 by two-tailed t test.

DISCUSSION

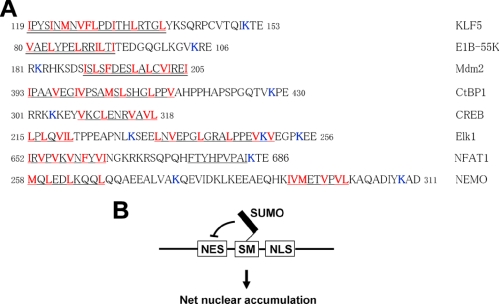

SUMOylation is a relatively newly identified form of post-translational modification that regulates a variety of cellular proteins central to physiology and pathophysiology (1-3). Among the many roles of SUMOylation is the regulation of nuclear localization (39, 52-56). However, the mechanism by which SUMOylation regulates nuclear localization is not well defined (1, 3). Here we show that SUMOylation of KLF5 facilitates its nuclear localization by inhibiting an NES adjacent to one of its two SUMOylation sites. A search for other proteins that nuclear localizations are facilitated by SUMOylation identified many in which a known NES or consensus NES is localized in close proximity to a SUMOylation site (Fig. 13A). In these proteins, mutation of the SUMOylation site adjacent to the NES often leads to cytoplasmic localization. For instance, CtBP1 (C-terminal binding protein 1) with mutation at its SUMOylation site Lys428 adjacent to a classic NES consensus motif (Fig. 13A) is relocalized to the cytoplasm (52). The SUMOylation sites in cAMP responsive element-binding proteins are Lys285 and Lys304 (53). A typical NES sequence is located immediately adjacent to Lys304 (Fig. 13A). Mutation of Lys304 to arginine results in the loss of both SUMOylation and nuclear localization. Lys182 rather than Lys185 is the SUMOylation site for Mdm2 (54). Both wild type Mdm2 and its K185R mutant are localized in nuclei, but the K182R mutant is localized to the cytoplasm (54). Of note, a known NES in Mdm2 is present only a few residues away from the SUMOylation site (Fig. 13A) (57). These observations are consistent with a causal relationship between SUMOylation and regulation of NES.

FIGURE 13.

Summary of regulation of nucleocytoplasmic transport by SUMOylation. A, alignment of various proteins of which nuclear localizations are facilitated by SUMOylation. The known SUMOylation sites that are involved in the regulation of nuclear transport are bolded in blue. The known NES motifs are double underlined and NES consensus sequences are underlined. The leucine or other large hydrophobic residues matching the NES consensus are bolded in red. Numbers are amino acid residue numbers. B, a model for the regulation of nucleocytoplasmic transport by SUMOylation. In this model, SUMOylation inhibits NES adjacent to a SUMOylation site, resulting in a net accumulation of the SUMOylated protein within the nucleus.

Although SUMOylation is not required for most targets to enter the nucleus, it has been shown that SUMOylation either contributes to the efficiency of nuclear transport or regulates nuclear localization of proteins under specific stimuli. For example, although the basal nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of NFAT1 is not affected by SUMOylation, SUMOylation mutants in ionomycin-treated baby hamster kidney cells are localized more to the cytoplasm than the wild type protein (55). Further addition of leptomycin B resulted in exclusive nuclear localization of both wild type and mutant NFAT1, suggesting that SUMOylation is required for NFAT1 nuclear retention (55). Although both Elk1 and the SUMOylation-defective Elk1-K230R/K249R/K254R mutant are primarily nuclear, the mutant exhibits altered kinetics of nuclear export, shuttling more rapidly from HeLa cell nuclei to fused BALB/c cell nuclei in heterokaryon fusion assays (39). NEMO (NF-κB essential modulator)/IKKγ SUMOylation is necessary for DNA damage-induced NF-κB activation. Both wild type NEMO and its SUMOylation-defective K277A/K309A mutant are primarily localized to the cytoplasm and lipopolysaccharide treatment does not alter this localization (56). However, cells treated with DNA damaging agent VP16 show nuclear staining of wild type NEMO, whereas the mutant remains cytoplasmic (56). Thus, SUMOylation may not necessarily be required for nuclear transport but is involved in its regulation in a highly context-dependent manner (1-3).

A common feature for all of the SUMOylated proteins listed above is the presence of a known or predicted NES adjacent to the SUMOylation site (Fig. 13A). Nuclear localization of these proteins is known to be facilitated by SUMOylation. In addition, all of these proteins shuttle between the cytoplasm and nucleus. This relationship would therefore be useful in predicting novel NESs or SUMOylation sites for shuttling proteins.

In the present study, we demonstrate that KLF5 shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm by several assays including immunofluorescence, subcellular fractionation, NES mutagenesis, leptomycin inhibition, and heterokaryon assay. Multiple lines of evidence indicate that the cytoplasmic residence of KLF5 is not due to protein aggregation or an artifact of overexpression. First, both transfected and endogenous KLF5 localize to the cytoplasm. Second, similar to other SUMOylated proteins (11, 52, 54, 55, 58-61), mutation at the KLF5 SUMOylation sites apparently does not introduce overall structural misfolding and functional disruption, as the SUMOylation mutants are still imported into the nucleus (Figs. 7 and 10), bind to CRM1 (Fig. 11), and promote cell growth (Fig. 12). Third, both leptomycin treatment and site-directed mutagenesis of LRS1 diminish the cytoplasmic localization of KLF5 (Fig. 10). The cytoplasmic distribution of the KLF5 SUMOylation mutants is similarly diminished by further mutation at LRS1 (Fig. 10), an effect attributable to inhibition of nuclear export but not expected to be caused by protein aggregation or mutation-induced off-target effects. Fourth, both GFP-LRS1 and KLF5 demonstrate punctuate cytoplasmic localization that is reminiscent of each other. Thus, the localization is unlikely to be random but largely dictated by the specific transport signal embedded in KLF5. Fifth, the localization in cytoplasm is rather specific, with the punctuate staining existing not only in the cells of primarily cytoplasmic KLF5 but also in some cells for which KLF5 is largely nuclear (Fig. 4). These results suggest that the nucleocytoplasmic localization of KLF5 is dynamically regulated. The heterogeneous nature of nucleocytoplasmic distribution has been shown for proteins whose localizations undergo dynamic regulation in, for instance, a growth-dependent manner, upon post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation, or after direct or indirect modulation of their nuclear transport machinery (62-64). Thus, our study presents SUMOylation as one way of regulating the nucleocytoplasmic localization of KLF5.

In the current study, two different types of SUMOylation mutants and a GFP reporter fused to isolated NES and SUMOylation motifs in KLF5 were used to directly test the hypothesis outlined above. This report provides evidence that SUMOylation facilitates nuclear localization by inhibiting a NES adjacent to a SUMOylation site. Relevant evidence was recently obtained for viral protein E1B-55K. The NES of E1B-55K closely borders its SUMOylation site at Lys104 (Fig. 13A) (12). Defects in this NES caused redistribution of E1B-55K from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, which was compensated by the SUMOylation null K104R mutation (12, 13). The two studies support a previous hypothesis that SUMOylation regulates NESs (2) and the hypothesis that a relatively general mechanism by which SUMOylation regulates nuclear localization is by modulating the activity of NES at an adjacent site.

However, at least in principal, a NES does not have to be close to a SUMOylation site in the primary sequence to be regulated by SUMOylation. The SUMOylation site may be close to NES in tertiary structure or after conformational change upon stimulation. Although the first SUMOylation site in KLF5, Lys151, is immediately next to LRS1 and appears to play a major role in regulating NES, the second SUMOylation site, Lys202, is not very far away from NES and may also contribute to the regulation. Be that as it may, the current study favors a relatively common mechanism by which SUMOylation regulates nuclear localization by modulating the activity of NES at a structurally adjacent site.

Results of both in vivo and in vitro binding assays (Fig. 11) suggest that the inhibition of LRS1 activity by SUMOylation does not involve inhibition of CRM1 binding to LRS1 although a definitive assessment is not possible due to the relatively small fraction of proteins that are SUMOylated. However, previous reports have implied that SUMOylation may not reduce CRM1 binding. For instance, SUMOylation enhances the interaction between BPV-E1 and CRM1 (10). RanBP2, a major SUMO ligase thought to be implicated in the regulation of nuclear transport by SUMOylation (1-3), is a docking site and key component for CRM1 during nuclear export and associates with high specificity to CRM1 (65). It remains to be seen whether SUMOylation selects against an active export complex in the majority of cases, as the zinc finger domain of RanBP2 bound exclusively to the inactive form of Ran regarding nuclear export (65, 66).

Based on these results, we propose a model by which SUMOylation regulates nuclear export (Fig. 13B). In this model, SUMOylation is a marker that controls export of nuclear proteins by regulating NES activities. We predict that proteins of which nuclear targeting is regulated by SUMOylation possess an intrinsic ability to shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Evidence suggests that although most nuclear proteins require nuclear localization signals (NLSs) for nuclear import, SUMOylation is not involved in inhibiting NLSs (1, 13). For example, Lys304 is one of the SUMOylation sites of the cAMP responsive element-binding protein and lies within a putative NLS (53). Mutation of Lys304 to arginine, which maintains NLS activity but abolishes SUMOylation, still results in loss in its nuclear localization (53). Both lysines 182 and 185 are located within the NLS of Mdm2 (54). Both wild type Mdm2 and its K185R mutant are localized in the nuclei, but K182R, which retains NLS activity but abrogates SUMOylation, is localized in the cytoplasm (54). If SUMOylation affects nuclear export of a subset of proteins by inhibiting NESs adjacent to their SUMOylation sites but does not impair the function of nearby NLSs, a net effect will be increased nuclear accumulation of the proteins over time. However, other mechanisms by which SUMOylation may facilitate nuclear retention of KLF5 are formally possible by, for example, facilitating the association of KLF5 with other factors or tethering KLF5 to structures within the nucleus.

Although KLF5 is known to regulate proliferation, development, and differentiation, and is involved in neoplastic transformation, how its subcellular localization is regulated is unknown. Herein we show that KLF5 is SUMOylated and localized to both the nucleus and cytoplasm. KLF5 contains a novel NES, which is inhibited by SUMOylation at an adjacent site. KLF5 SUMOylation enhances the nuclear localization and ability to stimulate anchorage independent growth of HCT116 cells. The effect of SUMOylation on KLF5 is distinct from the effect of SUMO or a SUMO E3 ligase, PIAS1, as PIAS1 binds and positively regulates KLF5 independent of SUMOylation (21). Thus, post-translational regulation of KLF5 can occur by either physical interaction or direct SUMOylation. The SUMOylation level of KLF5 is very low and neither the E2 SUMO enzyme, Ubc9, nor any of the three major classes of E3 SUMO ligases such as PIAS1, Pc2, and RanBP2 significantly SUMOylates KLF5 in the cells (data not shown), suggesting a relatively stringent control of KLF5 SUMOylation under normal conditions. Despite this, Ubc9 increases nuclear localization of wild type KLF5 but not the SUMOylation-null K151R/K202R and E153A/E2104A mutants (data not shown), indicating an SUMOylation-dependent increase in KLF5 nuclear localization by Ubc9, reinforcing the observation that SUMOylation enhances nuclear localization of KLF5.

KLF5 signaling may also be regulated in yet unidentified ways. KLF5 partially co-localizes and interacts with SNX3, and may be localized to cytoplasmic vesicles (Fig. 5) (21). SNX3 regulates membrane traffic and is associated with early endosomes through a PX (Phox homology) domain (49). It is the only SNX that may not bind internalized plasma membrane receptors (30). PX domain binds nuclear proteins, which, for instance, show preferential interactions with SNX4 (67). Although not a focus of this study, it would be interesting to determine whether KLF5 requires vesicle transport to mediate signaling.

We have consistently observed higher transforming potentials for KLF5 in a wide variety of non-transformed and transformed cell lines (16, 17, 19, 23). One of the best indicators of malignant growth potential is the ability of cells to proliferate in an anchorage-independent environment (43). This study shows that SUMOylation of KLF5 stimulates anchorage-independent growth in colorectal cancer cell line HCT116. This observation is consistent with other studies (8, 11, 61). SUMOylation is required for cell transformation by E1B-55K (11). Defective SUMOylation impairs PML/RARA-dependent immortalization and disease aggressiveness (61). PML-RARA did not significantly impair differentiation of primary hematopoietic progenitors and its transformed cells grew faster in liquid culture than those transduced with PML/RARA-K160R, a SUMOylation mutant (61). Mutation at the SUMOylation site of TEL is better than wild type at inhibiting colony formation in soft agar by RAS-transformed NIH3T3 cells (8). Thus, SUMOylation is involved in the progression of malignant cell transformation and may represent a “druggable” target in treating certain cancers. This study demonstrates that KLF5, which carries a novel NES, is post-translationally regulated by SUMOylation and localized to both the nucleus and cytoplasm. It provides the first direct evidence that SUMOylation facilitates nuclear localization of KLF5 by regulating adjacent nuclear export signal, which could be a common mechanism by which SUMOylation regulates nucleocytoplasmic transport.

Addendum—During the review of this article, a paper was published that described that SUMOylation of KLF5 alters its transcriptional program (68).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jerry Lingrel, Hans Will, and Anne Dejean for KLF5 cDNA and GFP-SUMO-1 and His-SUMO-1 plasmids.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK52230, DK64399, DK77381, and CA84197. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: SUMO, small ubiquitin-related modifier; BSA, bovine serum albumin; CRM1, chromosome region maintenance 1; GFP, green fluorescence protein; HA, hemagglutinin; IP, immunoprecipitation; KLF5, Krüppel-like factor 5; LRS, leucine-rich sequence; NEM, N-ethylmaleimide; NES, nuclear export signal; siRNA, small interfering RNA; SM, SUMOylation motif; LRS, leucine-rich sequence; NLS, nuclear localization signal; GTPγS, guanosine 5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate.

References

- 1.Johnson, E. S. (2004) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73 355-382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson, V. G., and Rangasamy, D. (2001) Exp. Cell Res. 271 57-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pichler, A., and Melchior, F. (2002) Traffic 3 381-387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terry, L. J., Shows, E. B., and Wente, S. R. (2007) Science 318 1412-1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pemberton, L. F., and Paschal, B. M. (2005) Traffic 6 187-198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kutay, U., and Guttinger, S. (2005) Trends Cell Biol. 15 121-124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sobko, A., Ma, H., and Firtel, R. A. (2002) Dev. Cell 2 745-756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood, L. D., Irvin, B. J., Nucifora, G., Luce, K. S., and Hiebert, S. W. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 3257-3262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter, S., Bischof, O., Dejean, A., and Vousden, K. H. (2007) Nat. Cell Biol. 9 428-435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosas-Acosta, G., and Wilson, V. G. (2008) Virology 373 149-162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Endter, C., Kzhyshkowska, J., Stauber, R., and Dobner, T. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 11312-11317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kindsmuller, K., Groitl, P., Hartl, B., Blanchette, P., Hauber, J., and Dobner, T. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 6684-6689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hay, R. T. (2005) Mol. Cell 18 1-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McConnell, B. B., Ghaleb, A. M., Nandan, M. O., and Yang, V. W. (2007) Bioessays 29 549-557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conkright, M. D., Wani, M. A., Anderson, K. P., and Lingrel, J. B. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res. 27 1263-1270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun, R., Chen, X., and Yang, V. W. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 6897-6900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nandan, M. O., Yoon, H. S., Zhao, W., Ouko, L. A., Chanchevalap, S., and Yang, V. W. (2004) Oncogene 23 3404-3413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghaleb, A. M., Nandan, M. O., Chanchevalap, S., Dalton, W. B., Hisamuddin, I. M., and Yang, V. W. (2005) Cell Res 15 92-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nandan, M. O., Chanchevalap, S., Dalton, W. B., and Yang, V. W. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579 4757-4762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang, Y., Goldstein, B. G., Chao, H. H., and Katz, J. P. (2005) Cancer Biol. Ther. 4 1216-1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du, J. X., Yun, C. C., Bialkowska, A., and Yang, V. W. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 4782-4793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen, C., Benjamin, M. S., Sun, X., Otto, K. B., Guo, P., Dong, X. Y., Bao, Y., Zhou, Z., Cheng, X., Simons, J. W., and Dong, J. T. (2006) Int. J. Cancer 118 1346-1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nandan, M. O., McConnell, B. B., Ghaleb, A. M., Bialkowska, A. B., Sheng, H., Shao, J., Babbin, B. A., Robine, S., and Yang, V. W. (2008) Gastroenterology 134 120-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagai, R., Suzuki, T., Aizawa, K., Shindo, T., and Manabe, I. (2005) J. Thromb. Haemostasis 3 1569-1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shindo, T., Manabe, I., Fukushima, Y., Tobe, K., Aizawa, K., Miyamoto, S., Kawai-Kowase, K., Moriyama, N., Imai, Y., Kawakami, H., Nishimatsu, H., Ishikawa, T., Suzuki, T., Morita, H., Maemura, K., Sata, M., Hirata, Y., Komukai, M., Kagechika, H., Kadowaki, T., Kurabayashi, M., and Nagai, R. (2002) Nat. Med. 8 856-863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang, J., Chan, Y. S., Loh, Y. H., Cai, J., Tong, G. Q., Lim, C. A., Robson, P., Zhong, S., and Ng, H. H. (2008) Nat. Cell Biol. 10 353-360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okita, K., Ichisaka, T., and Yamanaka, S. (2007) Nature 448 313-317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi, K., Tanabe, K., Ohnuki, M., Narita, M., Ichisaka, T., Tomoda, K., and Yamanaka, S. (2007) Cell 131 861-872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takahashi, K., and Yamanaka, S. (2006) Cell 126 663-676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haft, C. R., de la Luz Sierra, M., Barr, V. A., Haft, D. H., and Taylor, S. I. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 7278-7287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fogal, V., Gostissa, M., Sandy, P., Zacchi, P., Sternsdorf, T., Jensen, K., Pandolfi, P. P., Will, H., Schneider, C., and Del Sal, G. (2000) EMBO J. 19 6185-6195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muller, S., Berger, M., Lehembre, F., Seeler, J. S., Haupt, Y., and Dejean, A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 13321-13329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dang, D. T., Zhao, W., Mahatan, C. S., Geiman, D. E., and Yang, V. W. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30 2736-2741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamamoto, T., Gunji, S., Tsuji, H., and Beppu, T. (1983) J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 36 639-645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamamoto, T., Seto, H., and Beppu, T. (1983) J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 36 646-650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buschbeck, M., and Ullrich, A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 2659-2667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinol-Roma, S., and Dreyfuss, G. (1992) Nature 355 730-732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roth, J., Dobbelstein, M., Freedman, D. A., Shenk, T., and Levine, A. J. (1998) EMBO J. 17 554-564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salinas, S., Briancon-Marjollet, A., Bossis, G., Lopez, M. A., Piechaczyk, M., Jariel-Encontre, I., Debant, A., and Hipskind, R. A. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 165 767-773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tao, W., and Levine, A. J. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 6937-6941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guillemin, I., Becker, M., Ociepka, K., Friauf, E., and Nothwang, H. G. (2005) Proteomics 5 35-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bialkowska, A., Zhang, X. Y., and Reiser, J. (2005) BMC Genomics 6 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cox, A. D., and Der, C. J. (1994) Methods Enzymol. 238 277-294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hietakangas, V., Ahlskog, J. K., Jakobsson, A. M., Hellesuo, M., Sahlberg, N. M., Holmberg, C. I., Mikhailov, A., Palvimo, J. J., Pirkkala, L., and Sistonen, L. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 2953-2968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hsu, Y. H., Sarker, K. P., Pot, I., Chan, A., Netherton, S. J., and Bonni, S. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 33008-33018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perdomo, J., Verger, A., Turner, J., and Crossley, M. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 1549-1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shields, J. M., and Yang, V. W. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 18504-18507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi, H., Zhang, Z., Wang, X., Liu, S., and Teng, C. T. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res. 27 4807-4815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu, Y., Hortsman, H., Seet, L., Wong, S. H., and Hong, W. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3 658-666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ogawa, H., Inouye, S., Tsuji, F. I., Yasuda, K., and Umesono, K. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92 11899-11903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yashiroda, Y., and Yoshida, M. (2003) Curr. Med. Chem. 10 741-748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin, X., Sun, B., Liang, M., Liang, Y. Y., Gast, A., Hildebrand, J., Brunicardi, F. C., Melchior, F., and Feng, X. H. (2003) Mol. Cell 11 1389-1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Comerford, K. M., Leonard, M. O., Karhausen, J., Carey, R., Colgan, S. P., and Taylor, C. T. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 986-991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miyauchi, Y., Yogosawa, S., Honda, R., Nishida, T., and Yasuda, H. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 50131-50136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terui, Y., Saad, N., Jia, S., McKeon, F., and Yuan, J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 28257-28265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang, T. T., Wuerzberger-Davis, S. M., Wu, Z. H., and Miyamoto, S. (2003) Cell 115 565-576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Henderson, B. R., and Eleftheriou, A. (2000) Exp. Cell Res. 256 213-224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen, A., Wang, P. Y., Yang, Y. C., Huang, Y. H., Yeh, J. J., Chou, Y. H., Cheng, J. T., Hong, Y. R., and Li, S. S. (2006) J. Cell. Biochem. 98 895-911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gregoire, S., Tremblay, A. M., Xiao, L., Yang, Q., Ma, K., Nie, J., Mao, Z., Wu, Z., Giguere, V., and Yang, X. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 4423-4433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gomez-del Arco, P., Koipally, J., and Georgopoulos, K. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 2688-2697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu, J., Zhou, J., Peres, L., Riaucoux, F., Honore, N., Kogan, S., and de The, H. (2005) Cancer Cell 7 143-153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaffman, A., and O'Shea, E. K. (1999) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15 291-339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Turpin, P., Ossareh-Nazari, B., and Dargemont, C. (1999) FEBS Lett. 452 82-86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gama-Carvalho, M., and Carmo-Fonseca, M. (2001) FEBS Lett. 498 157-163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Singh, B. B., Patel, H. H., Roepman, R., Schick, D., and Ferreira, P. A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 37370-37378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yaseen, N. R., and Blobel, G. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 5516-5521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vollert, C. S., and Uetz, P. (2004) Mol. Cell Proteomics 3 1053-1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oishi, Y., Manabe, I., Tobe, K., Ohsugi, M., Kubota, T., Fujiu, K., Maemura, K., Kubota, N., Kadowaki, T., and Nagai, R. (2008) Nat. Med. 14 656-666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]