Abstract

Hypoxia plays an important role in vascular development through hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) accumulation and downstream pathway activation. We sought to explore the in vitro response of cultures of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), human endothelial progenitor cells (hEPCs), and human umbilical cord vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) to normoxic and hypoxic oxygen tensions. We first measured dissolved oxygen (DO) in the media of adherent cultures in atmospheric (21% O2), physiological (5% O2), and hypoxic oxygen conditions (1% O2). In cultures of both hEPCs and HUVECs, lower oxygen consumption was observed when cultured in 1% O2. At each oxygen tension, feeder-free cultured hESCs and iPSCs were found to consume comparable amounts of oxygen. Transport analysis revealed that the oxygen uptake rate (OUR) of hESCs and iPSCs decreased distinctly as DO availability decreased, whereas the OUR of all cell types was found to be low when cultured in 1% O2, demonstrating cell adaptation to lower oxygen tensions by limiting oxygen consumption. Next, we examined HIF-1α accumulation and the expression of target genes, including VEGF and angiopoietins (ANGPT; angiogenic response), GLUT-1 (glucose transport), BNIP3, and BNIP3L (autophagy and apoptosis). Accumulations of HIF-1α were detected in all four cell lines cultured in 1% O2. Corresponding upregulation of VEGF, ANGPT2, and GLUT-1 was observed in response to HIF-1α accumulation, whereas upregulation of ANGPT1 was detected only in hESCs and iPSCs. Upregulation of BNIP3 and BNIP3L was detected in all cells after 24-h culture in hypoxic conditions, whereas apoptosis was not detectable using flow cytometry analysis, suggesting that BNIP3 and BNIP3L can lead to cell autophagy rather than apoptosis. These results demonstrate adaptation of all cell types to hypoxia but different cellular responses, suggesting that continuous measurements and control over oxygen environments will enable us to guide cellular responses.

Keywords: oxygen, embryonic stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells, human umbilical cord vein endothelial cells, angiogenesis

during growth, oxygen is a primary participant in metabolic processes involving ATP, supplying energy for cellular functions. Although single-celled organisms can rely on the diffusion of oxygen, larger multicellular organisms have evolved a vascular system for transporting molecular oxygen to maintain sufficient oxygen levels for cellular functions while, at the same time, having the ability to respond to hypoxic conditions (20). Although atmospheric oxygen is typically 21%, physiological oxygen levels (normoxia) in adult and embryonic cells typically range from 2 to 12% (14, 60). Hypoxia occurs when oxygen falls below normal physiological levels, leading to insufficient ATP generation, which prevents cellular activities from occurring. Central to hypoxia tolerance is a hypometabolic state characterized by a reduction in oxygen consumption (2). Oxygen conservation relies on a rapid, reversible metabolic switch from carbohydrate oxidation to anaerobic glycolysis (32, 47). Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), a heterodimeric transcription factor composed of HIF-1α or HIF-2α and HIF-1β subunits, plays an essential role in the maintenance of oxygen homeostasis (55); activation of HIF proteins in response to hypoxia stimulates a transcriptional program that promotes erythropoiesis, glycolysis, apoptosis, and angiogenesis (9, 22, 24, 56).

The regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia is an important component of the homeostatic control mechanisms that link cardiopulmonary-vascular oxygen supplies to metabolic demand in local tissue (26). During development, proliferation and tube formation by endothelial cells (ECs) occur within hypoxic regions (12, 34). Recently, the delineation of the molecular mechanisms of angiogenesis has revealed a critical role for HIF-1α in the regulation of growth factors and various aspects of angiogenesis (26).

For many years, immortalized and primary vascular ECs were used as in vitro models to study human vascular development and regeneration. Human umbilical cord vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) have played a major role in the development of the vascular biology field by providing a critical in vitro model for insights into cellular and molecular events (5, 8, 13, 37, 66). Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) can mature into functional ECs and form blood vessels and are being isolated to understand the fundamental biology of their regulation as a population and their therapeutic potential for vascular regeneration (3, 41, 43, 58). In the past decade, the isolation of both adult and embryonic stem cells has provided opportunities to study their vascular differentiation and development, as well as their regenerative capabilities. Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), derived from the inner cell mass of a developing blastocyst, are capable of differentiating into all cell types of the body. Specifically, hESCs have the capability to differentiate and form blood vessels de novo in a process called vasculogenesis (18, 19, 35, 65). Recently, human somatic cells have been reprogrammed into cells that have comparable pluripotency to hESCs (38, 45, 62, 69). This cell type, called an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC), was shown to have the potential to differentiate into hematopoietic cells and ECs (11).

The cellular fate of stem cells (SCs) is regulated by their microenvironment (7). So far, the effect of hypoxia on hESCs or hEPCs has mainly been studied either by culturing the cells in an environment of low oxygen levels (15, 46, 51) or by genetically enforcing HIF-1α expression to study molecular pathways (29, 30). Advances in sensor technology offer the opportunity to perform online measurement and analysis of the dynamics of dissolved oxygen (DO) in the media of adherent cultures, to analyze the microenvironment generated by the cells, and to correlate it with gene regulation.

In this study, we took a first step toward linking the dynamics of DO levels to cellular responses. We explored the immediate responses to hypoxia of hESCs, iPSCs, hEPCs, and HUVECs in regard to the vasculogenesis/angiogenesis process. We first measured DO in the media of adherent cultures in atmospheric (21% O2), normoxic (5% O2), and hypoxic oxygen conditions (1% O2). We then estimated the oxygen flux in each case by approximating the oxygen levels throughout the culture media with a linear profile. We also computed the oxygen uptake rate (OUR) per cell, using the total oxygen flux and measuring cell density directly. Last, we analyzed cell responses to hypoxia via the expression of HIF-1α and target genes, including VEGF, angiopoietins ANGPT1 and ANGPT2 (angiogenesis); GLUT-1 (metabolism); BCL-2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3; autophagy); and Bnip3-like protein X (BNIP3L; apoptosis). All analyses were based on comparing HUVECs with hEPCs, and hESCs with iPSCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

All cells were cultured in humidified incubators (37°C) in atmospheres maintained with 5% CO2. Media for hESCs and iPSCs were changed every day, whereas other cells had media changed every other day.

Human pluripotent stem cells.

Both hESCs and human iPSCs were used; human ESC line H9 (passages 27–40; WiCell Research Institute, Madison, WI) and human iPSC line MP2 [passages 35–45; kindly provided by Dr. Linzhao Cheng (38)] were grown on an inactivated mouse embryonic feeder layer (Globalstem, Rockville, MD) in growth medium consisting of 80% ES-DMEM/F12 (Globalstem) supplemented with 20% knockout serum replacement and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; both from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at concentrations of 4 and 10 ng/ml for hESCs and iPSCs, respectively. Both cell lines were routinely examined for pluripotent markers using immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometry analysis for TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81, SSEA4, and Oct4. Before the start of each experiment, cells were passaged with 1 mg/ml type IV collagenase (Invitrogen) and then seeded on plates coated with Matrigel (BD Science, San Jose, CA) for feeder-free culturing. Conditioned Medium (Globalstem), used as the growth medium, was supplemented with the same bFGF concentrations as in feeder layer cultures.

Human EPCs.

Human umbilical cord CD31+ CD45− EPCs (passages 3–10; NDRI, Philadelphia, PA) were cultured in dishes coated with type I collagen (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) in endothelial growth medium (EGM; PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany) supplemented with 1 ng/ml VEGF165 (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Human EPCs were passaged every 3–4 days with 0.05% trypsin (Invitrogen).

HUVECs.

HUVECs (passages 1–6; PromoCell) were cultured in EGM and passaged every 3–4 days with 0.05% trypsin (Invitrogen).

Oxygen Measurements

DO was measured noninvasively using a commercially available sensor dish reader (SDR; PreSens, Regensburg, Germany) capable of reading DO levels from an immobilized fluorescent patch on a six-well plate (Oxo-Dish OD-6; PreSens). The plates are sterilized and calibrated by the manufacturer for consistency in measurements. All measurements were performed in a controlled environment within an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 and were taken every 5 min. Collected data were exported for analysis into Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and GraphPad Prism (4.02; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Hypoxic experiments were performed in a hermetically sealed, humidified modular incubator chamber (Billups-Rothenberg, Del Mar, CA). Low oxygen concentrations (1 and 5%) were obtained by flushing the chamber with an appropriate gas mixture (a 1% O2-5% CO2-N2 balance and a 5% O2-5% CO2-N2 balance, respectively) for 3 min at 3 psi and three times every 30 min at the beginning of each experiment. Afterward, the chamber was flushed once daily to avoid slight changes in control oxygen concentrations due to consumption of oxygen by the cells. Humidity within the chamber was maintained during the experiments by placing on the chamber bottom a plastic petri dish containing 10 ml of sterile water. To accommodate the SDR within the chamber, the chamber wall was modified to allow a data cable to pass through. Cells were counted by sampling a small portion of the cell suspension, followed by their trypsinization into single cells. Known numbers of cells in colonies were then seeded onto Oxo-Dishes and placed on the SDR. This procedure allowed us to maintain cells in colonies while passaging and seeding approximately known cell concentrations.

For DO reading and gene analysis experiments, all cell types were allowed to attach in atmospheric oxygen for 24 h, and the cell medium was aspirated and replaced with 6 ml of medium before being cultured in atmospheric, normoxic, and hypoxic oxygen concentrations. This excessive volume of media was used to prevent media depletion throughout the experiments. DO readings were taken for 72 h without disturbing the system, and the cells were counted at the end of each experiment. Gene analysis was performed on cells using the exact same conditions, at different time intervals of the cultures as indicated below. The culture media used in these studies were buffered with sodium bicarbonate, which maintains a pH of around 7.2 in an environment with 5% CO2.

Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR

Two-step RT-PCR was performed on hESCs, iPSCs, hEPCs, and HUVECs that were cultured for 24, 48, and 72 h in 21, 5, and 1% O2. Total RNA was extracted by using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA was quantified using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer, and the samples were validated for having no DNA contamination. RNA (1 μg per sample) was transcribed using the reversed transcriptase M-MLV and oligo(dT) primers (both from Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. We used the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix and Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions for VEGF, GLUT-1, ANGPT1, ANGPT2, BNIP, BNIP3L, β-ACTIN, and HPRT1. The TaqMan PCR step was performed with an Applied Biosystems StepOne real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The relative expressions of VEGF, GLUT-1, ANGPT1, ANGPT2, BNIP, and BNIP3L were normalized to the amount of HPRT1 or β-ACTIN in the same cDNA by using the standard curve method described by the manufacturer. For each primer set, the comparative computerized tomography method (Applied Biosystems) was used to calculate the amplification differences between the different samples. The values for experiments were averaged and graphed with standard deviations.

Flow Cytometric Analysis (Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting)

For cell cycle analysis, cells were initially exposed to atmospheric, 5%, and 1% O2 tensions for 24 h (16, 21, 33, 36). They were then collected with trypsin and washed once with PBS. Cells were fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol overnight at 4°C. Triton X-100 (0.1%) and RNase A (100 μg/ml; Qiagen, Valencia, CA) were added for a final concentration of 106 cells/ml, and cells were incubated in the solution for 2 h at 37°C before being stained with 50 μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 15 min at 37°C. To avoid clumping, cells were strained through a 40-μm cell strainer. Cell cycles were analyzed with the BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer, reading the signals detected by FL2. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software version 7.5 to determine the frequencies of each cell cycle phase.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed using 3.7% formaldehyde fixative for 15 min and washed with PBS. For staining, cells were permeabilized with a solution of 0.05% Triton-X for 10 min, washed with PBS, and incubated for 1 h with anti-human HIF-1α (1:250; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells were rinsed twice with PBS and incubated with anti-mouse IgG Cy3 conjugate (1:50; Sigma Aldrich) for 1 h, rinsed with PBS, and incubated with 4–6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1:1,000; Roche Diagnostics) for 10 min. Coverslips were rinsed once more with PBS and mounted with fluorescent mounting medium (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). The immunolabeled cells were examined using fluorescence microscopy (Olympus BX60).

Graphs and Statistics

All oxygen measurements were performed on triplicate samples (n = 3), with triplicate readings of each sample for each data point. Real-time RT-PCR was also performed on triplicate samples (n = 3) with triplicate readings. Graphs for DO in atmospheric O2 were plotted with standard deviation (SD), using DO data points every 24 h throughout the experiment. Variations in the OUR values were estimated by calculating the minimum and maximum possible uptake rates from the SDs in the cell number and oxygen flux, and a graph for the OUR was plotted with SD error bars. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests were performed where appropriate (GraphPad Prism 4.02). Significance levels were determined between atmospheric oxygen and 5 or 1% O2 and were set at P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001 as indicated. All graphical data are reported.

RESULTS

DO in Cultures of HUVECs, hEPCs, hESCs, and iPSCs

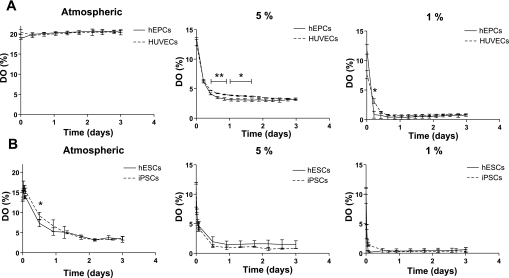

We measured the levels of DO along adherent cultures of HUVECs, hEPCs, hESCs, and iPSCs in tissue culture incubator conditions, e.g., atmospheric oxygen (20% O2). HUVECs and hEPCs were seeded on Oxo-Dishes at 0.1 × 106 cells/well. Before DO measurements were performed for hESCs and iPSCs, three different cell seeding densities were tested, and the minimum cell density necessary to observe a significant amount of oxygen consumption was found to be 1.5 × 106 cells/well. These cell concentrations allowed DO measurements to be made over a period of up to 3 days. Representative output data of DO from each culture medium can be found in Supplemental Fig. 1. (Supplemental data for this article is available online at the American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology website.) We found that DO levels of both HUVECs and hEPCs remained constant at ∼19–20% along the culture period (Fig. 1A, left). DO levels of hESCs and iPSCs decreased along the culture period, and these two cell types were found to be comparable in terms of total oxygen consumption when cultured in 20% O2 (Fig. 1B, left). To measure DO levels in hypoxic conditions, we seeded hEPCs and HUVECs on Oxo-Dishes at 0.1 × 106 cells/well, whereas hESCs and iPSCs were seeded at 1.5 × 106 cells/well. After cell attachment (of hEPCs and HUVECs) and colony formation (of hESCs and iPSCs) was allowed in atmospheric oxygen, cultures were placed within a hypoxic chamber, flushed multiple times with the appropriate gas mixture, and placed within the incubator. Triplicate readings of media without cells were taken simultaneously as a control (data not shown). Small deviations were observed in control DO levels, about ±1% at each oxygen tension, due to the sensitivity of the sensors and the high cell density of hESCs and iPSCs. Measurements of media alone showed equilibrium with gas phase within about 12 h in both 5 and 1% O2 for all media types. Furthermore, during the initial equilibrium period, oscillations in DO were observed. These oscillations are most likely due to temperature fluctuations caused by the lower temperature of the gas mixture (∼25°C), used to flush the chamber multiple times at the beginning of each experiment (see Supplemental Fig. 2). DO levels in hEPCs reached equilibrium within 12 h and remained at 3.4 and 0.7% throughout the culture in 5 and 1% O2, respectively (Fig. 1A, middle and right). DO levels in HUVEC cultures reached equilibrium with the oxygen exposure levels within 12 h. However, throughout the 72-h culture period, DO levels were sustained in the case of 1% O2 exposure (0.5 to 1%), whereas they decreased slightly over the culture period at 5% O2 exposure, and DO levels reached ∼3% (Fig. 1A, middle and right). In hESC and iPSC cultures, a pronounced decrease was observed in DO levels. Both cell types followed a similar trend where, after about 12 h, DO readings fell below 1.5 and 0.4% in cultures of 5 and 1% O2, respectively (Fig. 1B, middle and right).

Fig. 1.

Dissolved oxygen (DO) levels in normoxic and hypoxic cultures of human umbilical cord vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), human endothelial progenitor cells (hEPCs), human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). A: sensor readings of DO levels in the media of HUVECs and hEPCs cultured in atmospheric, 5%, and 1% O2. B: sensor readings of DO levels in the media of hESCs and iPSCs cultured in atmospheric, 5%, and 1% O2. Values are means ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

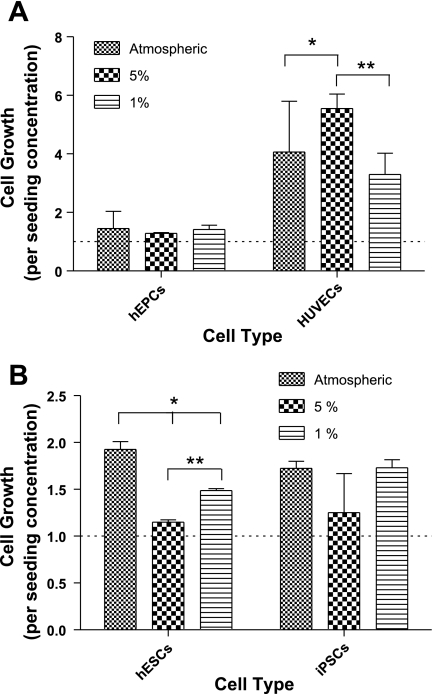

Cell Growth in Atmospheric, 5%, and 1% O2 Concentrations

Cells were then counted at the end of each culture period. In general, the cell growth of HUVECs was significantly higher than that of hEPCs (Fig. 2A). No significant difference in cell growth of hEPCs at the three different oxygen concentrations could be detected, although we detected a noticeable increase in HUVECs grown in 5% O2 compared with HUVECs grown in atmospheric oxygen or 1% O2 (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Cell growth in normoxic and hypoxic cultures of HUVECs, hEPCs, hESCs, and iPSCs. A: cell growth normalized to initial cell seeding after 72 h of culturing HUVECs and hEPCs in atmospheric, 5%, and 1% O2. B: cell growth normalized to initial cell seeding after 72 h of culturing hESCs and iPSCs in atmospheric, 5%, and 1% O2. Values are means ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

We observed a decrease in cell growth rate of hESCs cultured in 5% O2 compared with hESCs cultured in atmospheric O2. When cultured in 1% O2, hESCs grew faster than in 5% O2 but slower than in atmospheric oxygen (Fig. 2B). No difference in cell growth was observed in iPSCs cultured in 5% or 1% O2 compared with iPSCs cultured in atmospheric oxygen (Fig. 2B). We found the growth of hESCs and iPSCs cells to be comparable to each other (Fig. 2B).

Modeling DO Levels and Consumption Rates

In the present experiments, the DO levels in the cell cultures were controlled indirectly through the partial oxygen pressure in the chamber (CO2, concentration of oxygen in the medium; Po2, partial pressure of oxygen in the chamber). Assuming equilibrium at the liquid-gas interface, we can calculate the DO levels by using Henry's law and approximating the solubility of oxygen by that in water:

| (1) |

where xO2 is the molar fraction of oxygen in the liquid and H is the Henry's law constant for oxygen in water at 37°C: H = 5.2 × 104 atm. In all of the experiments, but particularly in those performed at relatively low oxygen pressures in the chamber (1 and 5%), we observed measurable differences in the oxygen levels between the equilibrium value at the gas-liquid interface and the DO level at the oxygen sensors, located at the bottom surface where the cells attached to the plate. In fact, this difference in oxygen levels allows us to estimate the instantaneous OUR during the experiments. Consider the schematic view of the system in Supplemental Fig. 3a1. Given that a typical cell size, d <50 μm, is much smaller than the thickness of the liquid layer, h = 0.62 cm, we can simplify the problem to the one-dimensional transport of oxygen through a uniform layer, incorporating the OUR as a boundary condition for the oxygen flux at the bottom surface, y = a (Supplemental Fig. 3a2). Neglecting the transient behavior and assuming that the oxygen concentration remains steady, the mass transport equation inside the liquid phase (Supplemental Fig. 3a3) then becomes

| (2) |

with boundary conditions C* = CO2(h) = xO2/Vm (Vm = 18 cm3/mol is the molar volume of water), and CO2(0) = C0, where C0 is the concentration measured at the bottom surface. The diffusivity of oxygen in medium is approximated by that in water at 37°C: DO2 = 3.35 × 10−5 cm2/s. The instantaneous molar flow rate of oxygen at the bottom surface, normalized by the cell count (and thus, the OUR per cell) is then given by

| (3) |

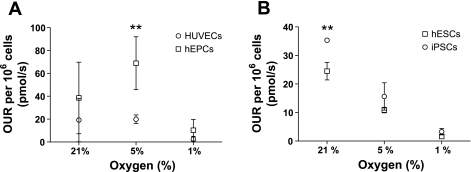

where ϕ is the cell density in cells per centimeter square. The previous equation also assumes that population changes are slow enough that we can approximate the evolution as a quasi-equilibrium of the oxygen flux to the instantaneous number of cells in the substrate. Table 1 presents a summary of the calculations. Oxygen flux calculations showed the OUR of hEPCs to be higher than that of HUVECs at every oxygen tension. Oxygen uptake rates decreased for both cells when cultured at 1% O2 (Fig. 3A).

Table 1.

Oxygen flux in HUVECs, hEPCs, hESCs, and iPSCs

| Control | |||

| Po2, % | Atmospheric | 5 | 1 |

| xo2 | 4 × 10−6 | 9.6 × 10−7 | 1.9 × 10−7 |

| C*, μM | 224 | 53 | 11 |

| HUVECs | |||

| C0, μM | 150 ± 4.0 | 23 ± 1.5 | 6.5 ± 1.0 |

| Po2, % | 20 | 3 | 0.85 |

| ϕ, cells/cm2 × 10−4 | 4.0 ± 2.0 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 1.0 |

| OUR, pmol/106 cells | 19.2 | 19.9 | 2.5 |

| hEPCs | |||

| C0, μM | 152.0 ± 2.0 | 26.0 ± 4.0 | 5.5 ± 1.5 |

| Po2, % | 20 | 3.4 | 0.74 |

| ϕ, cells/cm2 × 10−4 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.05 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| OUR, pmol/106 cells | 38.5 | 68.9 | 10.3 |

| hESCs | |||

| C0, μM | 45.3 ± 130.6 | 14.8 ± 7.2 | 5.2 ± 5 |

| Po2, % | 3.2 | 1.6 | 0.4 |

| ϕ, cells/cm2 × 10−4 | 30.0 ± 1.3 | 17.9 ± 0.4 | 23.5 ± 0.2 |

| OUR, pmol/106 cells | 24.4 | 10.8 | 1.5 |

| iPSCs | |||

| C0, μM | 31.8 ± 0.67 | 8.5 ± 0.3 | 3.05 ± 3 |

| Po2, % | 3.7 | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| ϕ, cells/cm2 × 10−4 | 26.7 ± 4.0 | 19.5 ± 6.5 | 21.3 ± 5.6 |

| OUR, pmol/106 cells | 35.3 | 15.6 | 3.3 |

Oxygen flux was estimated from the difference between the equilibrium dissolved oxygen (DO) level at the liquid-gas interface and that level measured by the sensors at the bottom surface of the culture for human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), human endothelial progenitor cells (hEPCs), human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Oxygen uptake rate (OUR) per cell was computer by normalizing the oxygen flux with the measured cell density (ϕ). xo2, molar fraction of oxygen in liquid; C0, concentration of oxygen in medium at bottom of chamber; C*, boundary condition (see text for details).

Fig. 3.

Oxygen uptake rate (OUR) analysis. OUR, normalized per cell, is shown in HUVEC and hEPC cultures (A) and in hESC and iPSC cultures (B) in atmospheric, 5%, and 1% O2. Values shown are means ± SD. **P < 0.01.

On the other hand, we observed that changes in oxygen tensions strongly influenced the OUR of both hESCs and iPSCs. The oxygen deprivation in cultures of hESCs and iPSCs decreased the oxygen consumption rate of both types of cell as a result of adaptation to hypoxic conditions. No significant difference in the OUR was observed between hESCs and iPSCs (Fig. 3B).

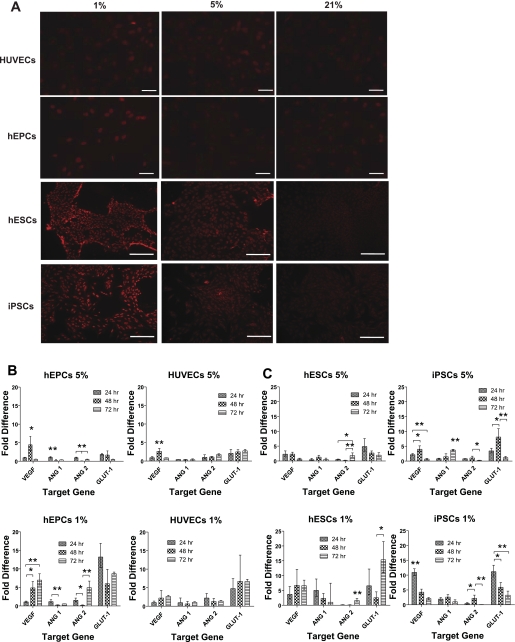

Regulation of Hypoxic Target Genes

Because HIF-1α was demonstrated to target important genes involved in angiogenesis and glycolysis (26, 47), we analyzed its upregulation in the various cultures. First, HIF-1α accumulation was determined 5 h after the start of the cultures (protein expression), whereas target gene regulation was determined after 24, 48, and 72 h (mRNA regulation). Immunofluorescence staining of HIF-1α revealed nuclear localization and background expression levels in all cell lines cultured in atmospheric oxygen. Upregulation of HIF-1α was detectable in hEPCs only when cultured in 1% O2, whereas it was detected in HUVECs, hESCs, and iPSCs in both 5 and 1% O2 (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Hypoxic target gene regulation. A: immunofluorescence staining of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) HUVECs, hEPCs, hESCs, and iPSCs cultured in atmospheric, 5%, and 1% O2 for 5 h. Scale bars, 100 μm. B and C: relative changes in target gene expression from their expression in atmospheric O2 in hEPCs and HUVECs (B) and in hESCs and iPSCs (C) cultured in 5 and 1% O2. Values are means ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Figure 4B shows gene regulation of hEPCs and HUVECs cultured in 5 and 1% O2. In 5% O2 conditions, upregulation of GLUT-1 was observed after 24 h in both hEPCs and HUVECs (2.0- and 1.8-fold, respectively), but whereas it remained upregulated over the 3 days of culture in HUVECs, it decreased in hEPCs. In both cell types, upregulation of VEGF was observed only after 48 h. No upregulation was detected for either ANGPT1 or ANGPT2 in the two cell types. In 1% O2, higher upregulation of GLUT-1 was observed in both cell types, whereas it remained around 6.7-fold in HUVECs throughout the 72 h of culture and decreased from 13.2-fold after 24 h in hEPCs. An increase in VEGF expression was observed in both cell types, reaching a maximum of 6.9-fold in hEPCs and 2.6-fold in HUVECs by the end of the culture period. Interestingly, ANGPT2 was also upregulated 4.9-fold in hEPCs cultured for 72 h in 1% O2. Only slight upregulation of ANGPT2 was detected in HUVECs cultured in 1% O2 for 24 h, but this diminished by the end of the culture period.

Figure 4C shows gene regulation of hESCs and iPSCs cultured in 5 and 1% O2. In 5% O2 conditions, we observed upregulation in hESCs of both GLUT-1 and VEGF after 24 h (4.8- and 2.3-fold, respectively); this diminished over the culture period. In iPSCs, peaks in GLUT-1 and VEGF expression were observed after 48 h (8.1- and 3.9-fold, respectively). A 3.7-fold upregulation of ANGPT1 was observed after 72 h only in iPSC cultures. In 1% O2 conditions, we observed upregulation in iPSCs of VEGF, GLUT-1, and ANGPT1 (10.9-, 11.1-, and 1.9-fold, respectively) within 24 h; this decreased by the end of the culture period. In hESCs, upregulation of GLUT-1, VEGF, and ANGPT1 was observed within 24 h (6.5-, 3.6-, and 5.0-fold, respectively); but whereas expression of ANGPT1 decreased throughout the culture period, expression of VEGF increased after 48 h (reaching 6.7-fold), and expression of GLUT-1 increased throughout the culture period, reaching 15.3-fold by the end of the culture period.

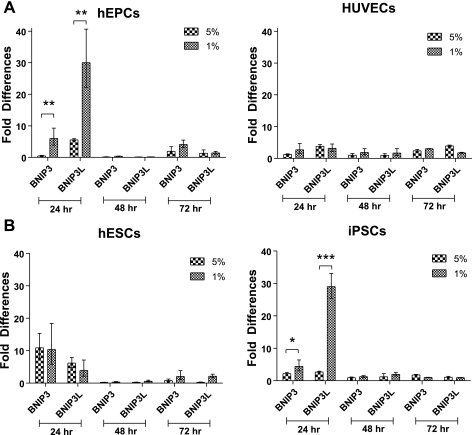

Autophagy, Apoptotic Genes, and Cell Cycle Arrest

The severity of the hypoxia determined whether cells became apoptotic or adapted to hypoxia and survived. We therefore examined the upregulation of the autophagy gene of the BCL-2 family, BNIP3 (70), and the proapoptotic gene BNIP3L, also of the BCL-2 family. Upregulation of BNIP3 was observed in both hEPCs and HUVECs cultured in 5% O2, which fluctuated after 48 h but remained increased after 72 h (Fig. 5A, left and right). However, after 24 h of culture in 1% O2 conditions, BNIP3 and BNIP3L were highly upregulated in hEPCs and slightly upregulated in HUVECs, but their expression decreased throughout the culture period (Fig. 5A). We observed upregulation in the expression of both genes in hESCs and iPSCs cultured in either 5 or 1% O2 concentrations for 24 h (although to various levels). These elevated expression levels decreased throughout the culture period in both cell types and both culture conditions (Fig. 5B). To examine the cell cycle, we performed flow cytometric analysis after 24 h of culture in atmospheric, 5%, and 1% oxygen. No apoptotic cells could be detected in any of the cell types cultured in any of the culture conditions (Supplemental Fig. 4). Tables 2 and 3 show quantification analysis of the different cell cycle phases. A decrease in the portion of cells in the G2 phase was observed in hESCs (cultured in 5 and 1% O2) and HUVECs (cultured in 5% O2). G1- and S-phase frequencies of these cell types were observed to increase in both 1 and 5% O2 tensions. Particularly, significant increases were observed in the portion of hESCs in the G1 phase in 5% O2 and the portion of HUVECs in the G1 phase in 1% O2. A noticeable increase was also observed in the portion of hEPCs in the S phase when cultured in 1% O2.

Fig. 5.

Autophagy and apoptotic genes. Relative changes in BNIP3 and BNIP3L upregulation from their expression in atmospheric O2 in HUVECs, hEPCs, hESCs, and iPSCs when cultured in 5 and 1% O2. Values are means ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Table 2.

Frequencies of cell cycle phase in hEPCs and HUVECs cultured in different oxygen concentrations for 24 h

| hEPCs |

HUVECs |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atmospheric O2 | 5% O2 | 1% O2 | Atmospheric O2 | 5% O2 | 1% O2 | |

| G1 | 62.9 | 48.4 | 40.4 | 30.0 | 27.1 | 44.5 |

| S | 8.9 | 9.2 | 29.8 | 8.6 | 13.2 | 10.4 |

| G2 | 28.4 | 41.6 | 30.0 | 60.1 | 58.4 | 44.5 |

Cell cycle phases in HUVECs and hEPCs analyzed from representative flow cytometry data using FlowJo software and presented as frequencies from the entire cell population examined.

Table 3.

Frequencies of cell cycle phase in hESCs and iPSCs cultured in different oxygen concentrations for 24 h

| hESCs |

iPSCs |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atmospheric O2 | 5% O2 | 1% O2 | Atmospheric O2 | 5% O2 | 1% O2 | |

| G1 | 30.7 | 50.5 | 36.3 | 41.0 | 48.7 | 48.3 |

| S | 27.1 | 33.2 | 34.2 | 42.9 | 25.7 | 27.8 |

| G2 | 41.9 | 16.3 | 28.5 | 15.0 | 26.0 | 23.9 |

Cell cycle phases in hESCs and iPSCs analyzed from representative flow cytometry data using FlowJo software and presented as frequencies from the entire cell population examined.

DISCUSSION

The development of the vasculature, an oxygen delivery system, directly depends on subtle differences in tissue oxygen levels, ensuring that resident cells maintain proper metabolic activity. Cultures of HUVECs have been shown to maintain nearly all features of native ECs, such as EC-specific markers and VEGF signaling pathways, making them a good tool for the study of ECs. In addition, culturing HUVECs on Matrigel in a hypoxic environment results in the formation of tubelike structures that resemble tube formation in vivo, providing evidence for blood vessel recruitment to tissues under ischemic stress (44). Overexpression of HIF-1α in EPCs promoted their differentiation, proliferation, and migration and ultimately increased angiogenesis at ischemic sites (29, 30). The hEPCs used in the current study are umbilical cord hEPCs isolated from outgrowth clones expanded and are characterized by the positive expression of cell-surface antigens CD31, CD141, CD105, CD144, von Willebrand factor (vWF), and Flk-1, and the negative expression of hematopoietic-cell surface antigens CD45 and CD14 (28, 39, 50, 64, 67). Despite the similarities in their surface protein expressions, hEPCs and HUVECs show differences in proliferation, migration, and differentiation capabilities (27, 63). Therefore, to examine cellular responses of vascular cells to various oxygen tensions, we chose to compare these two cell types.

A growing body of evidence demonstrates that cultures in hypoxic conditions improve pluripotency and reprogramming while maintaining normal karyotyping (15, 49, 68). In the current study we were drawn by the vascular differentiation potential of hESCs and human iPSCs (11, 23). Zandstra and colleagues (46, 51) recently applied controlled oxygen microenvironments to suspension cultures of differentiated ESCs to enhance the generation of the hemogenic mesoderm and its derivatives via HIF-1α/VEGF pathway activation. The human iPSC line used in the current study, MP2, was derived from human fibroblasts and has been demonstrated to express undifferentiated hESC markers and to be induced to differentiate into the derivatives of the three embryonic germ layers in both teratoma formation and embryoid body formation assays (38). Therefore, we compared hESCs and human iPSCs responses to various oxygen tensions in regard to the vasculogenesis/angiogenesis process.

The fulfillment of the potential of SCs to advance our understanding of signaling pathways that regulate human vascular development and regeneration depends on the ability to culture them in vitro in conditions similar to their native surroundings. Thus we cultured HUVECs, hEPCs, hESCs, and iPSCs in 5 and 1% O2, corresponding to physiological and hypoxic conditions. These results were compared with conventional cultures in atmospheric oxygen (20% O2). We found that DO levels did not change significantly in either hEPC or HUVEC cultures in atmospheric oxygen. When cultured in 5% O2, DO levels of hEPC cultures equilibrated at around 3%, which was sustained throughout the culture period. In HUVECs, DO levels decreased along the culture, reaching 3%. After 12 h, in the case of hypoxia, DO levels of both hEPCs and HUVECs equilibrated with the exposure concentration. DO levels decreased sharply in cultures of hESCs and iPSCs at all oxygen concentrations, most likely due to high cell seeding density. The total oxygen consumption of these two cell types was found to be comparable throughout the culture period at every oxygen tension. DO measurements at the cellular level showed substantial difference from control oxygen levels. This implies that DO levels should be monitored online and controlled to maintain desired oxygen concentrations at the cellular level without altering other parameters such as shear stress or soluble factors. For instance, using larger volumes of medium for this purpose may still result in oxygen gradients throughout the culture medium with oxygen tension being lowest at the cell microenvironment. On the other hand, stirring medium continuously will generate shear stress that may damage cell membrane or initiate cellular responses that should be considered as well. However, desired oxygen concentrations can be achieved at cellular level by continuous monitoring and setting the partial pressure of oxygen inside the culture chamber to a higher value accounting for the oxygen gradients across the culture medium and cell responses.

During the initial equilibration period in hypoxic experiments, oxygen is released from the culture medium to the gas phase, which requires flushing of culture chamber multiple times. The volume of medium used (6 ml/well) accompanied with the low solubility and diffusivity of oxygen in the medium led to 12 h of initial equilibration period. On the other hand, temperature fluctuations due to relatively low temperature of flushed gas mixture also prolonged the equilibration time. These effects should be considered especially in studies examining the immediate effects of hypoxia on cells before the equilibrium point is reached.

The differences between oxygen exposure levels (in the air) and DO levels in the medium and differences in cell growth revealed a collective response to changes in oxygen levels. It also raised the question whether the OUR is regulated by oxygen levels in the single-cell microenvironment. Therefore, we took a transport modeling approach to determine oxygen flux based on sensor readings and cell numbers. In general, the observed OURs at atmospheric conditions were consistent with previously reported values, ∼0.03–0.4 nmol/s per 106 cells (1, 10, 40). Oxygen flux calculations showed that the OUR of all cell types decreased when cultured in 1% O2, suggesting adaptation to low oxygen levels. In cultures of both hEPCs and HUVECs, no overall correlation existed between oxygen fluxes and DO availability. The only significant difference between the two cell types was observed at 5% O2, which can be due to the differences observed in proliferation rates that affect cell-to-cell contact and therefore may affect the OUR. In the case of hESCs and iPSCs, oxygen flux calculations showed that both cell types had very similar aerobic metabolic activities. Clearly, oxygen availability strongly regulated the OUR of both hESCs and iPSCs, and these two cell types were found to adapt to low oxygen tensions in terms of their OURs. In general, the cell growth rate of all cell types was not significantly altered when cultured in hypoxic conditions for 72 h. The HUVEC growth rate was found to be higher when cultured in 5% O2, whereas hESCs grew slower in these conditions. Human ESCs cultured at low oxygen tensions showed a slower cell growth rate compared with hESCs cultured at atmospheric oxygen. Although the control oxygen was maintained at 5 or 1%, DO measurements revealed that oxygen tension at the cellular level is equilibrated at 1.5 and 0.4%, respectively. Recent studies (25, 48) have demonstrated that hematopoietic stem cells are located at very lowly oxygenated regions of bone marrow, and when cultured at very low oxygen tensions (0.01–1.7%), they tend to return to Go phase and remain quiescent. Our findings for hESCs are in good agreement with these studies, suggesting that exposing hESCs to very low oxygen tensions slows their growth. It also should be noted that the iPSCs used in this study were derived using SV40 large T-antigen vector, which was suggested to contribute to an increased level of abnormal karyotypes (38). Although this may attribute to the slight variations observed in cell growth, both oxygen consumption and aerobic metabolic activities of hESCs and iPSCs were found to be comparable, suggesting similar cellular responses of both cell types.

To correlate the sensor reading, cell growth, and oxygen fluctuation with the mechanistic involvement of HIF-1α, we examined its expression and target gene regulation. It may be that a relatively long equilibration period of oxygen delays the accumulation of HIF-1α but not likely the regulation of its target genes. We therefore examined gene regulation at time intervals over the entire culture period. Slight upregulation of HIF-1α in hEPCs and HUVECs cultured in 5% O2 correlated with mild upregulation of downstream glucose transport (GLUT-1) and angiogenesis (VEGF) genes. When cultured in 1% O2, the accumulation of HIF-1α within 5 h resulted in a higher upregulation of GLUT-1 and VEGF, but to different extents in hEPCs and HUVECs. In addition, we detected upregulation of another angiogenic gene, ANGPT2, to a lesser level in HUVECs after 24 h and to a higher level in hEPCs after 72 h of culture in 1% O2. These results may correlate to a previous study that demonstrated an increase in ANGPT2 expression in pulmonary artery ECs exposed to 1% O2 (31) and collectively may indicate the hypoxic regulation of ANGPT2 in the vasculature. In the case of hESCs and iPSCs, culture in 5% O2 resulted in higher upregulation of both GLUT-1 and VEGF and even induced upregulation of ANGPT2 in iPSCs after 72 h. When hESCs and iPSCs were cultured in 1% O2, HIF-1α accumulation resulted in upregulation of GLUT-1 and VEGF in both cell types, which decreased along the culture period of iPSCs while increasing in hESCs. ANGPT1 was upregulated in both cell types after 24 h and decreased along the culture period, whereas ANGPT2 was only slightly upregulated in iPSCs after 48 h. Although HIF-1α regulation of these genes has been well established (57), other factors in the culture can affect their expression and need further investigation.

A number of studies have shown that HIF-1α promotes apoptosis via induction of several proapoptotic target genes, including the BCL-2 family members of proapoptotic factors BNIP3 and BNIP3L (6, 52, 53, 59, 61). However, the exact mechanism promoting apoptosis is not yet known (9, 22, 24). In contrast, some recent studies have demonstrated that BNIP3 (70), or both BNIP3 and BNIP3L (4), mediates autophagy in hypoxic cells, which leads to cell survival. Upregulation of both BNIP3 and BNIP3L was detected in all cell types at the end of 24 h of culture in hypoxic conditions. However, we found that they returned to their normal expression levels at the end of the culture period. This correlates to a similar cell growth rate for each cell type in hypoxic conditions and in atmospheric conditions and to no evidence of apoptosis, as demonstrated by cell cycle analysis after 24 h. In agreement with recent studies (4, 42), our data also support the suggestion that hypoxia-inducible BNIP3 and BNIP3L do not induce apoptosis in HUVECs, hEPCs, hESCs, and iPSCs. On the other hand, the relatively significant differences observed in the growth rates of hESC and HUVEC cultures at varying oxygen conditions could have been caused by cell cycle arrest. Some studies have shown that hypoxic conditions induce cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 (54) or G1/S (17) transitions. Quantification of cell cycle analysis revealed a considerable increase in the portion of hESCs in the G1 phase when cultured in 5% O2 and an increase in the portion of HUVECs in the G1 phase in the case of 1% O2 exposure. These findings are in agreement with the observed decrease in growth rates of these cultures, suggesting a cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase. Quantification of the cell cycle did not provide additional information beyond an increase of hESCs in the G1 phase, which correlates to an observed decrease in their growth rate at 5% O2, indicating cell cycle arrest. Our results demonstrate that although all cell types examined, including vascular primary cells, adult progenitors, and pluripotent SCs, adapt to a hypoxic environment with no evidence of apoptosis, different cellular responses occur at different oxygen concentrations during their culture in vitro. We therefore conclude that although a biomimetic approach is desirable to recapitulate developmental events and to induce differentiation pathways of human stem cells, online monitoring and continuous control over microenvironmental oxygen levels are required to generate targeted cellular responses.

GRANTS

This research was partially supported by National Cancer Institute Grant U54CA143868, an American Heart Association-Scientist Development grant, and a March of Dimes-O'Conner Starter Scholar Award (both to S. Gerecht).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Prof. Linzhao Cheng and Prashant Mali for the iPSCs and Prof. Gregg L. Semenza for critical review of an earlier version of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen JW, Khetani SR, Bhatia SN. In vitro zonation and toxicity in a hepatocyte bioreactor. Toxicol Sci 84: 110–119, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews MT. Genes controlling the metabolic switch in hibernating mammals. Biochem Soc Trans 32: 1021–1024, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T, Kalka C, Pastore C, Silver M, Kearne M, Magner M, Isner JM. Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ Res 85: 221–228, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellot G, Garcia-Medina R, Gounon P, Chiche J, Roux D, Pouyssegur J, Mazure NM. Hypoxia-induced autophagy is mediated through hypoxia-inducible factor induction of BNIP3 and BNIP3L via their BH3 domains. Mol Cell Biol 29: 2570–2581, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bevilacqua MP, Gimbrone MA., Jr Inducible endothelial functions in inflammation and coagulation. Semin Thromb Hemost 13: 425–433, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruick RK. Expression of the gene encoding the proapoptotic Nip3 protein is induced by hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 9082–9087, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burdick JA, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Engineered microenvironments for controlled stem cell differentiation. Tissue Eng Part A 15: 205–219, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns MP, DePaola N. Flow-conditioned HUVECs support clustered leukocyte adhesion by coexpressing ICAM-1 and E-selectin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H194–H204, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmeliet P, Dor Y, Herbert JM, Fukumura D, Brusselmans K, Dewerchin M, Neeman M, Bono F, Abramovitch R, Maxwell P, Koch CJ, Ratcliffe P, Moons L, Jain RK, Collen D, Keshert E. Role of HIF-1alpha in hypoxia-mediated apoptosis, cell proliferation and tumour angiogenesis. Nature 394: 485–490, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho CH, Park J, Nagrath D, Tilles AW, Berthiaume F, Toner M, Yarmush ML. Oxygen uptake rates and liver-specific functions of hepatocyte and 3T3 fibroblast co-cultures. Biotechnol Bioeng 97: 188–199, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi KD, Yu J, Smuga-Otto K, Salvagiotto G, Rehrauer W, Vodyanik M, Thomson J, Slukvin I. Hematopoietic and endothelial differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 27: 559–567, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Covello KL, Simon MC. HIFs, hypoxia, and vascular development. Curr Top Dev Biol 62: 37–54, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies PF. Overview: temporal and spatial relationships in shear stress-mediated endothelial signalling. J Vasc Res 34: 208–211, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Souza N. Too much of a good thing. Nat Methods 4: 386, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ezashi T, Das P, Roberts RM. Low O2 tensions and the prevention of differentiation of hES cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 4783–4788, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ezhilarasan R, Mohanam I, Govindarajan K, Mohanam S. Glioma cells suppress hypoxia-induced endothelial cell apoptosis and promote the angiogenic process. Int J Oncol 30: 701–707, 2007 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner LB, Li Q, Park MS, Flanagan WM, Semenza GL, Dang CV. Hypoxia inhibits G1/S transition through regulation of p27 expression. J Biol Chem 276: 7919–7926, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerecht-Nir S, Dazard JE, Golan-Mashiach M, Osenberg S, Botvinnik A, Amariglio N, Domany E, Rechavi G, Givol D, Itskovitz-Eldor J. Vascular gene expression and phenotypic correlation during differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Dev Dyn 232: 487–497, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerecht-Nir S, Ziskind A, Cohen S, Itskovitz-Eldor J. Human embryonic stem cells as an in vitro model for human vascular development and the induction of vascular differentiation. Lab Invest 83: 1811–1820, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giaccia AJ, Simon MC, Johnson R. The biology of hypoxia: the role of oxygen sensing in development, normal function, and disease. Genes Dev 18: 2183–2194, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goda N, Ryan HE, Khadivi B, McNulty W, Rickert RC, Johnson RS. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha is essential for cell cycle arrest during hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol 23: 359–369, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greijer AE, van der Wall E. The role of hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) in hypoxia induced apoptosis. J Clin Pathol 57: 1009–1014, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanjaya-Putra D, Gerecht S. Vascular engineering using human embryonic stem cells. Biotechnol Prog 25: 2–9, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris AL. Hypoxia—a key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nat Rev Cancer 2: 38–47, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hermitte F, Brunet de la Grange P, Belloc F, Praloran V, Ivanovic Z. Very low O2 concentration (0.1%) favors G0 return of dividing CD34+ cells. Stem Cells 24: 65–73, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirota K, Semenza GL. Regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 59: 15–26, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingram DA, Mead LE, Moore DB, Woodard W, Fenoglio A, Yoder MC. Vessel wall-derived endothelial cells rapidly proliferate because they contain a complete hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells. Blood 105: 2783–2786, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingram DA, Mead LE, Tanaka H, Meade V, Fenoglio A, Mortell K, Pollok K, Ferkowicz MJ, Gilley D, Yoder MC. Identification of a novel hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells using human peripheral and umbilical cord blood. Blood 104: 2752–2760, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang M, Wang B, Wang C, He B, Fan H, Guo TB, Shao Q, Gao L, Liu Y. Angiogenesis by transplantation of HIF-1 alpha modified EPCs into ischemic limbs. J Cell Biochem 103: 321–334, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang M, Wang B, Wang C, He B, Fan H, Shao Q, Gao L, Liu Y, Yan G, Pu J. In vivo enhancement of angiogenesis by adenoviral transfer of HIF-1alpha-modified endothelial progenitor cells (Ad-HIF-1alpha-modified EPC for angiogenesis). Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40: 2284–2295, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelly BD, Hackett SF, Hirota K, Oshima Y, Cai Z, Berg-Dixon S, Rowan A, Yan Z, Campochiaro PA, Semenza GL. Cell type-specific regulation of angiogenic growth factor gene expression and induction of angiogenesis in nonischemic tissue by a constitutively active form of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Circ Res 93: 1074–1081, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JW, Tchernyshyov I, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab 3: 177–185, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krick S, Eul BG, Hanze J, Savai R, Grimminger F, Seeger W, Rose F. Role of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in hypoxia-induced apoptosis of primary alveolar epithelial type II cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 32: 395–403, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee YM, Jeong CH, Koo SY, Son MJ, Song HS, Bae SK, Raleigh JA, Chung HY, Yoo MA, Kim KW. Determination of hypoxic region by hypoxia marker in developing mouse embryos in vivo: a possible signal for vessel development. Dev Dyn 220: 175–186, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levenberg S, Golub JS, Amit M, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Langer R. Endothelial cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 4391–4396, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li C, Issa R, Kumar P, Hampson IN, Lopez-Novoa JM, Bernabeu C, Kumar S. CD105 prevents apoptosis in hypoxic endothelial cells. J Cell Sci 116: 2677–2685, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Libby P. Multiple mechanisms of thrombosis complicating atherosclerotic plaques. Clin Cardiol 23, Suppl 6: VI-3–VI-7, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mali P, Ye Z, Hommond HH, Yu X, Lin J, Chen G, Zou J, Cheng L. Improved efficiency and pace of generating induced pluripotent stem cells from human adult and fetal fibroblasts. Stem Cells 26: 1998–2005, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mead LE, Prater D, Yoder MC, Ingram DA. Isolation and characterization of endothelial progenitor cells from human blood. In: Current Protocols in Stem Cell Biology New York: Wiley Interscience, chapt. 2, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mehta G, Mehta K, Sud D, Song JW, Bersano-Begey T, Futai N, Heo YS, Mycek MA, Linderman JJ, Takayama S. Quantitative measurement and control of oxygen levels in microfluidic poly(dimethylsiloxane) bioreactors during cell culture. Biomed Microdevices 9: 123–134, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melero-Martin JM, Khan ZA, Picard A, Wu X, Paruchuri S, Bischoff J. In vivo vasculogenic potential of human blood-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Blood 109: 4761–4768, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mellor HR, Harris AL. The role of the hypoxia-inducible BH3-only proteins BNIP3 and BNIP3L in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 26: 553–566, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murayama T, Asahara T. Bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells for vascular regeneration. Curr Opin Mol Ther 4: 395–402, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagata D, Mogi M, Walsh K. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling in endothelial cells is essential for angiogenesis in response to hypoxic stress. J Biol Chem 278: 31000–31006, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Okita K, Mochiduki Y, Takizawa N, Yamanaka S. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol 26: 101–106, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niebruegge S, Bauwens CL, Peerani R, Thavandiran N, Masse S, Sevaptisidis E, Nanthakumar K, Woodhouse K, Husain M, Kumacheva E, Zandstra PW. Generation of human embryonic stem cell-derived mesoderm and cardiac cells using size-specified aggregates in an oxygen-controlled bioreactor. Biotechnol Bioeng 102: 492–507, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papandreou I, Cairns RA, Fontana L, Lim AL, Denko NC. HIF-1 mediates adaptation to hypoxia by actively downregulating mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell Metab 3: 187–197, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parmar K, Mauch P, Vergilio JA, Sackstein R, Down JD. Distribution of hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow according to regional hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 5431–5436, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prasad SM, Czepiel M, Cetinkaya C, Smigielska K, Weli SC, Lysdahl H, Gabrielsen A, Petersen K, Ehlers N, Fink T, Minger SL, Zachar V. Continuous hypoxic culturing maintains activation of Notch and allows long-term propagation of human embryonic stem cells without spontaneous differentiation. Cell Prolif 42: 63–74, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prater DN, Case J, Ingram DA, Yoder MC. Working hypothesis to redefine endothelial progenitor cells. Leukemia 21: 1141–1149, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Purpura KA, George SH, Dang SM, Choi K, Nagy A, Zandstra PW. Soluble Flt-1 regulates Flk-1 activation to control hematopoietic and endothelial development in an oxygen-responsive manner. Stem Cells 26: 2832–2842, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ray R, Chen G, Vande Velde C, Cizeau J, Park JH, Reed JC, Gietz RD, Greenberg AH. BNIP3 heterodimerizes with Bcl-2/Bcl-X(L) and induces cell death independent of a Bcl-2 homology 3 (BH3) domain at both mitochondrial and nonmitochondrial sites. J Biol Chem 275: 1439–1448, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reiling JH, Hafen E. The hypoxia-induced paralogs Scylla and Charybdis inhibit growth by down-regulating S6K activity upstream of TSC in Drosophila. Genes Dev 18: 2879–2892, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmaltz C, Hardenbergh PH, Wells A, Fisher DE. Regulation of proliferation-survival decisions during tumor cell hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol 18: 2845–2854, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Semenza GL. Life with oxygen. Science 318: 62–64, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 3: 721–732, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Semenza GL. Vascular responses to hypoxia and ischemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30: 648–652, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shi Q, Rafii S, Wu MH, Wijelath ES, Yu C, Ishida A, Fujita Y, Kothari S, Mohle R, Sauvage LR, Moore MA, Storb RF, Hammond WP. Evidence for circulating bone marrow-derived endothelial cells. Blood 92: 362–367, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shoshani T, Faerman A, Mett I, Zelin E, Tenne T, Gorodin S, Moshel Y, Elbaz S, Budanov A, Chajut A, Kalinski H, Kamer I, Rozen A, Mor O, Keshet E, Leshkowitz D, Einat P, Skaliter R, Feinstein E. Identification of a novel hypoxia-inducible factor 1-responsive gene, RTP801, involved in apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol 22: 2283–2293, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Simon MC, Keith B. The role of oxygen availability in embryonic development and stem cell function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9: 285–296, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sowter HM, Ratcliffe PJ, Watson P, Greenberg AH, Harris AL. HIF-1-dependent regulation of hypoxic induction of the cell death factors BNIP3 and NIX in human tumors. Cancer Res 61: 6669–6673, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131: 861–872, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tepper OM, Capla JM, Galiano RD, Ceradini DJ, Callaghan MJ, Kleinman ME, Gurtner GC. Adult vasculogenesis occurs through in situ recruitment, proliferation, and tubulization of circulating bone marrow-derived cells. Blood 105: 1068–1077, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Timmermans F, Plum J, Yöder MC, Ingram DA, Vandekerckhove B, Case J. Endothelial progenitor cells: Identity defined? J Cell Mol Med 13: 87–102, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang L, Li L, Shojaei F, Levac K, Cerdan C, Menendez P, Martin T, Rouleau A, Bhatia M. Endothelial and hematopoietic cell fate of human embryonic stem cells originates from primitive endothelium with hemangioblastic properties. Immunity 21: 31–41, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamada T, Fan J, Shimokama T, Tokunaga O, Watanabe T. Induction of fatty streak-like lesions in vitro using a culture model system simulating arterial intima. Am J Pathol 141: 1435–1444, 1992 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yöder MC, Mead LE, Prater D, Krier TR, Mroueh KN, Li F, Krasich R, Temm CJ, Prchal JT, Ingram DA. Redefining endothelial progenitor cells via clonal analysis and hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell principals. Blood 109: 1801–1809, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoshida Y, Takahashi K, Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Hypoxia enhances the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 5: 237–241, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318: 1917–1920, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang H, Bosch-Marce M, Shimoda LA, Tan YS, Baek JH, Wesley JB, Gonzalez FJ, Semenza GL. Mitochondrial autophagy is an HIF-1-dependent adaptive metabolic response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem 283: 10892–10903, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.