Conditions covered in systematic reviews

(see Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.090313/-/DC1 for summary of recommendations and clinical considerations)

Infectious diseases

Measles, mumps, rubella

Diphtheria, tetanus, polio, pertussis

Varicella

Hepatitis B

Tuberculosis

HIV

Hepatitis C

Intestinal parasites (Strongyloides and Schistosoma)

Malaria

Mental health and maltreatment

Depression

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Child maltreatment

Intimate partner violence

Chronic and noncommunicable diseases

Diabetes mellitus

Iron-deficiency anemia

Dental disease

Vision health

Women’s health

Contraception

Cervical cancer

Pregnancy

1. Overview: evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees

There are more than 200 million international migrants worldwide,1 and this movement of people has implications for individual and population health.2 The 2009 United Nations Human Development Report3 suggested that migration benefits people who move, through increased economic and education opportunities, but migrants frequently face barriers to local health and social services. In Canada, international migrants are a growing4 and economically important segment of the population (Table 1A).5–8

Table 1A:

Classification of international migration to Canada (2007)*

| Immigration category | Annual migration (no.)†‡ |

|---|---|

| Permanent residents6 | |

| Economic class (business and economic migrants) | 131 000 |

| Family class (family reunification) | 66 000 |

| Humanitarian class (refugees resettled from abroad or selected in Canada from refugee claimants) | 28 000 |

| Others | 11 000 |

| Total | 237 000 |

| Temporary residents6 | |

| Migrant workers | 165 000 |

| International students | 74 000 |

| Refugee claimants (those arriving in Canada and claiming to be refugees)6 | 28 000 |

| Other temporary residents6 | 89 000 |

| Total6 | 357 000 |

| Other migrants | |

| Total irregular migrants,§ not annual migration7 | ~ 200 000 |

| Visitors8 | ~ 30 100 000 |

Reproduced, with permission, from Gushulak et al.5

Numbers rounded to nearest 1000. Total in each category may not match sum of values reported because of rounding.

Unless otherwise indicated.

No official migration status; this population includes those who have entered Canada as visitors or temporary residents and remained to live or work without official status. It also includes those who may have entered the country illegally and not registered with authorities or applied for residence.

Immigrants to Canada are a heterogeneous group. Upon arrival, new immigrants are healthier than the Canadian-born population, both because of immigrant-selection processes and policies and because of sociocultural aspects of diet and health behaviours. However, there is a decline in this “healthy immigrant effect” after arrival.5 In addition, compared with the Canadian-born population, subgroups of immigrants are at increased risk of disease-specific mortality; for example, Southeast Asians from stroke (odds ratio [OR] 1.46, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.00–1.91),9 Caribbeans from diabetes mellitus (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.03–2.32) and infectious diseases (e.g., for AIDS, OR 4.23, 95% CI 2.72–5.74), and immigrant men from liver cancer (OR 4.89, 95% CI 3.29–6.49).10

The health needs of newly arriving immigrants and refugees often differ from those of Canadian-born men, women and children. The prevalence of diseases differs with exposure to disease, migration trajectories, living conditions and genetic predispositions. Language and cultural differences, along with lack of familiarity with preventive care and fear and distrust of a new health care system, can impair access to appropriate health care services.11 Additionally, patients may present with conditions or concerns that are unfamiliar to practitioners.5,10

Many source countries have limited resources and differing health care systems, and these differences may also contribute to health inequalities among migrants.12 In these guidelines, we refer to low-and middle-income countries as “developing.”

Why are clinical guidelines for immigrants needed?

Canadian immigration legislation requires that all permanent residents, including refugees, refugee claimants and some temporary residents, undergo an immigration medical examination. Screening is undertaken to assess the potential burden of illness and a limited number of public health risks. The examination is not designed to provide clinical preventive screening, as is routinely performed in Canadian primary care practice, and it is linked to ongoing surveillance or clinical actions only for tuberculosis, syphilis and HIV infection.5

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care and the US Preventive Services Task Force have produced many high-quality clinical prevention recommendations, but these statements have not explicitly considered the unique preventive needs and implementation issues for special populations such as immigrants and refugees. Evidence-based recommendations can improve uptake and health outcomes related to preventive services, even more so when they are tailored for specific populations.13

How are these guidelines different?

Use of evidence-based methods has yet to substantially affect the field of migration medicine.14 The Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health explicitly aims to improve patients’ health using an evidence-based clinical preventive approach to complement existing public health approaches. In selecting topics, primary care practitioners considered not just the burden of illness but also health inequities and gaps in current knowledge.15 Public health concerns and predeparture migrant screening and treatment protocols were also considered, but these were not the driving force for the recommendations. We implemented evidence-based methods, which included searches for evidence on immigrant preferences and values, as well as incorporating the GRADE approach (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation), to formulate clinical preventive recommendations.16–18 Our evidence reviews synthesized data from around the world, and our recommendations focus on immigrants, refugees and refugee claimants, with special attention given to refugees, women and the challenges of integrating recommendations into primary care. Migrants living without official status are particularly vulnerable, but specific evidence for this population is limited.19 In these guidelines, the “health settlement period” refers to the first five years of residence in Canada for an immigrant or refugee, the time during which loss of the healthy immigrant effect begins to surface.

In recent years, there has been an increase in development of practice guidelines for international migrants.20 Notable publications have included Cultural Competency in Health,21 Immigrant Medicine22 and guidelines for refugees from the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases.23 Many have been designed to address diseases and conditions of public health importance,23–25 and some highlight the importance of psychosocial problems and mental illness, issues of women’s health and chronic noninfectious diseases.21,26,27 Other practice guidelines include strategies to improve communication (e.g., interpreters), responsiveness to sociocultural background (e.g., cultural competence), empowerment (e.g., health literacy), monitoring (e.g., health and access disparities) and strategies for comprehensive care delivery.21

Our recommendations differ from other guidelines because of our insistence on finding evidence for clear benefits before recommending routine interventions. For example, in our guidelines for post-traumatic stress disorder, intimate partner violence and social isolation in pregnancy, we recommend not conducting routine screening, but rather remaining alert. With regard to screening for asymptomatic intestinal parasites, we recommend focusing on serologic testing for high burden of disease parasites, rather than traditional testing of stool for ova and parasites.

How were these guidelines developed?

We followed the internationally recognized Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE; www.agreetrust.org). We selected guideline topics using a literature review, stakeholder engagement and the Delphi process with equity-oriented criteria.15 In May 2007, we held a consensus meeting of experts in immigrant and refugee health to develop a systematic process for transparent, reproducible, evidence-based reviews. The guideline committee selected review leaders from across Canada on the basis of their clinical and evaluation expertise (see Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.090313/-/DC1).

The 14-step evidence review process (Box 1A)16 used validated tools to appraise the quality of existing systematic reviews, guidelines, randomized trials and other study designs. We searched MEDLINE, Embase, the Cochrane Library and other sources for admissible evidence, specifically reviews and related studies, from 1996 to 2010. We identified guidelines developed by other groups but based our recommendations on evidence from primary studies. We identified patient-important outcomes and used the GRADE approach to assess the magnitude of effect on benefits and harms and on quality of evidence. We included both direct evidence from immigrant and refugee populations and indirect evidence from other populations. We downgraded the quality of evidence for indirectness when there was concern that the evidence might not be applicable to immigrant and refugee populations (e.g., because of differences in baseline risk, morbidity and mortality, genetic and cultural factors, and compliance variations). We assessed whether benefits outweighed harms, the quality of evidence, and values and preferences to minimize the potentially negative effects of labelling on patients, families and communities (Table 1B).16–18

Box 1A: Fourteen-step process for evidence reviews used by the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health.

Develop clinician summary table

Develop logic model and key questions

Set the stage for admissible evidence (using search strategy)

Assess eligibility of systematic reviews

Search for data specific to immigrant and refugee populations

Refocus on key clinical preventive actions and key questions

Assess quality of systematic reviews

Search for evidence to update selected systematic reviews

Assess eligibility of new studies

Integrate data from updated search

Synthesize final evidence bank and draft two key clinical actions

Develop table for summary of findings

Identify gaps in evidence and needs for future research

Develop clinical preventive recommendations using GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation)

Adapted, with permission, from Tugwell and others.16

Table 1B:

Basis of recommendations*

| Issue | Process considerations |

|---|---|

| Balance between desirable and undesirable effects | Those with net benefits or trade-offs between benefits and harms were eligible for a positive recommendation |

| Quality of evidence | Quality of evidence was classified as “high,” “moderate,” “low” or “very low” on the basis of methodologic characteristics of available evidence for a specific clinical action |

| Values and preferences | Values and preferences refer to the worth or importance of health state or consequences of following a particular clinical action |

Each of the resulting evidence reviews for priority conditions of the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health provides detailed methods and results concerning the burden of illness for the immigrant populations relative to Canadian-born populations, along with information about effectiveness of screening and interventions, a discussion of clinical considerations, the basis for recommendations and gaps in research.

How should I begin to assess immigrants for clinical preventive care?

Determine each person’s age, sex, country of origin and migration history to tailor preventive care recommendations. In caring for socially disadvantaged populations, sequencing of care using checklists or algorithms can improve both the uptake and the delivery of preventive care13 and allows other members of the primary health care team to participate in the delivery of care. Working with interpreters, cultural brokers, patients’ families and community support networks can support culturally appropriate care.28 Most importantly, clinicians should recognize that the implementation of recommendations (vaccinations, for example) may take three or four visits, a process more akin to the delivery of well-baby care than to an annual examination. Our recommendations are aimed at primary care practitioners, but competencies related to immigrant and cross-cultural care will vary depending on training and experience, and expert support should be sought accordingly.

Which immigrant populations face the most significant health risks?

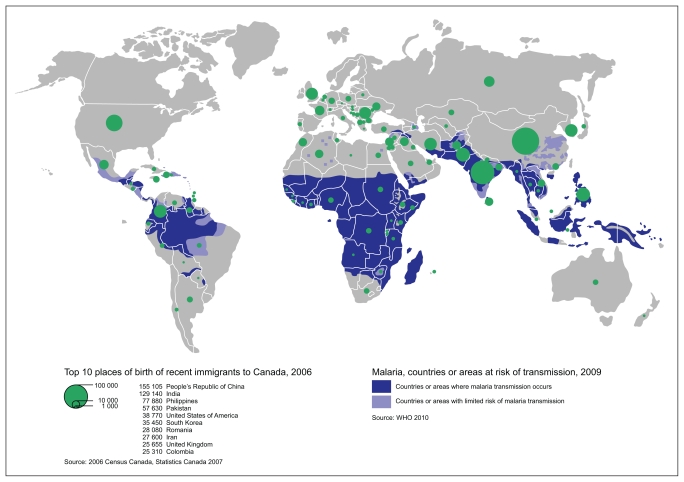

Refugees, who are by definition forcefully displaced, are at highest risk for past exposure to harmful living conditions, violence and trauma. Refugees undergo medical screening before admission to Canada but are protected by law from exclusion on the basis of noninfectious burden of illness (through the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act).29 The health risks of refugees and other migrants vary greatly depending on exposures (e.g., to vectors of disease such as mosquitos), trauma from war, living conditions (e.g., access to water and sanitation), neglect from long periods in refugee camps, susceptibilities (e.g., related to ethnicity and migration stress), social stratification (e.g., race, sex, income, education and occupation) and access to preventive services (e.g., predeparture access to primary care, vaccinations and screening, access to Canadian services and access issues related to linguistic and cultural barriers).

Specifically, refugees are at risk for a rapid decline in self-reported health after arrival (OR 2.31, 95% CI 1.1–4.9), as are low-income immigrants (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.3–1.7) and immigrants with limited English- or French-language proficiency.5,30–35 There is also an increased risk of reporting poor health among immigrants with limited English- or French- language proficiency (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.5–2.7), those facing cost-related barriers to health care (OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.7–4.5),36 low-income immigrants32 and non-European immigrants (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.6–3.3).31

Clinical recommendations

Considering the burden of illness of immigrant populations, the quality of evidence for screening and interventions, and the feasibility of clinicians implementing the recommendations, we have organized our recommendations into four groups: infectious diseases, mental health and physical and emotional maltreatment, chronic and noncommunicable diseases, and women’s health.

Appendix 2 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.090313/-/DC1) summarizes the evidence review and recommendations for each topic, providing specific comments about how the number needed to screen and treat for net benefits would differ for immigrant populations.

Infectious diseases

Many immigrants are susceptible to vaccine-preventable diseases upon arrival in Canada. For example, 30%–50% of new immigrants are susceptible to tetanus,37 32%–54% are susceptible to either measles, mumps or rubella,38 and immigrants from tropical countries are 5–10 times more susceptible to varicella,39 which has serious implications for adult immigrants.

A large proportion (20%–80%) of the immigrants who come from countries where chronic hepatitis B virus infection is prevalent are not immune and have not been immunized. In addition, immigrants are more likely to be exposed to hepatitis B virus40 in their households and during travel to countries where hepatitis B is prevalent. Immigrants from countries where chronic hepatitis B virus infection is prevalent (affecting 2% or more of the population) can benefit from screening and treatment to prevent hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

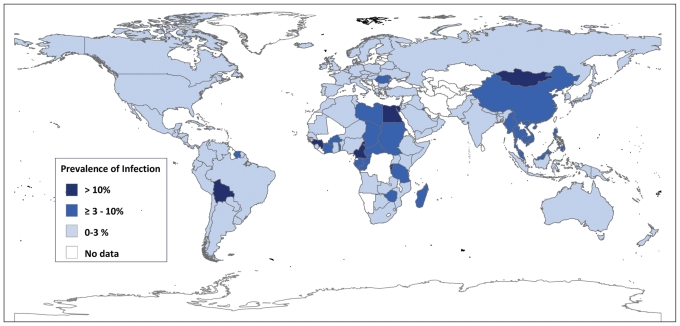

Foreign-born people account for 65% of all active tuberculosis in Canada,41 and screening and treatment for latent tuberculosis remain priorities for immigrants from countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and Central and South America.42 To promote patients’ safety and adherence to therapy, patients must be informed of the risks and benefits of treatment in a culturally and linguistically appropriate manner.43,44 Refugees may already be aware of their HIV-positive status but may have limited knowledge of effective screening and treatment options. HIV-related stigma and discrimination45 put immigrants and refugees at risk for delayed diagnosis and unequal treatment rates for HIV infection. Immigrants are an unrecognized risk group for chronic hepatitis C virus infection and would benefit from early detection and appropriately timed treatment.46

Subclinical strongyloidiasis and schistosomiasis can persist for decades after immigration and, if left untreated, can lead to serious morbidity or death through disseminated disease.47 Serologic tests for these intestinal parasites, rather than traditional stool testing, are recommended.48 Malaria is one of the leading causes of death worldwide,49 and delay in diagnosis and treatment of Plasmodium falciparum may lead to severe disease and even death. Migrant children are especially at risk for malaria and its complications.50

Recommendations for infectious diseases are summarized in Box 1B.

Box 1B: Summary of evidence-based recommendations for infectious diseases*.

Measles, mumps and rubella

Vaccinate all adult immigrants without immunization records using one dose of measles–mumps–rubella vaccine.

Vaccinate all immigrant children with missing or uncertain vaccination records using age-appropriate vaccination for measles, mumps and rubella.

Diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus and polio

Vaccinate all adult immigrants without immunization records using a primary series of tetanus, diphtheria and inactivated polio vaccine (three doses), the first of which should include acellular pertussis vaccine.

Vaccinate all immigrant children with missing or uncertain vaccination records using age-appropriate vaccination for diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus and polio.

Varicella

Vaccinate all immigrant children < 13 years of age with varicella vaccine without prior serologic testing.

Screen all immigrants and refugees from tropical countries ≥ 13 years of age for serum varicella antibodies, and vaccinate those found to be susceptible.

Hepatitis B

Screen adults and children from countries where the seroprevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection is moderate or high (i.e., ≥ 2% positive for hepatitis B surface antigen), such as Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe, for hepatitis B surface antigen, anti-hepatitis B core antibody and anti-hepatitis B surface antibody.

Refer to a specialist if positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (chronic infection).

Vaccinate those who are susceptible (negative for all three markers).

Tuberculosis

Screen children, adolescents < 20 years of age and refugees between 20 and 50 years of age from countries with a high incidence of tuberculosis as soon as possible after their arrival in Canada with a tuberculin skin test.

If test results are positive, rule out active tuberculosis and then treat latent tuberculosis infection.

Carefully monitor for hepatotoxity when isoniazid is used.

HIV

Screen for HIV, with informed consent, all adolescents and adults from countries where HIV prevalence is greater than 1% (sub-Saharan Africa, parts of the Caribbean and Thailand).

Link HIV-positive individuals to HIV treatment programs and post-test counselling.

Hepatitis C

Screen for antibody to hepatitis C virus in all immigrants and refugees from regions with prevalence of disease ≥ 3% (this excludes South Asia, Western Europe, North America, Central America and South America).

Refer to a hepatologist if test result is positive.

Intestinal parasites

Strongyloides: Screen refugees newly arriving from Southeast Asia and Africa with serologic tests for Strongyloides, and treat, if positive, with ivermectin.

Schistosoma: Screen refugees newly arriving from Africa with serologic tests for Schistosoma, and treat, if positive, with praziquantel.

Malaria

Do not conduct routine screening for malaria.

Be alert for symptomatic malaria in migrants who have lived or travelled in malaria-endemic regions within the previous three months (suspect malaria if fever is present or person migrated from sub-Saharan Africa). Perform rapid diagnostic testing and thick and thin malaria smears.

Order of listing considers clinical feasibility and quality of evidence.

Mental health and physical and emotional maltreatment

Mental health care of immigrants has emerged as one of the most challenging areas for clinicians.15 Among refugees, depression commonly co-occurs with post-traumatic stress disorder and other anxiety disorders,51 which can complicate its detection and treatment.28 Conducting a systematic clinical assessment, or using a validated questionnaire in a language in which the patient is fluent,52 is recommended if the clinician practises in an integrated system that links patients with suspected depression to treatment programs with a stepped-care approach. Effective detection and treatment may also require the use of professional interpreters or trained culture brokers (not children or other family members) to identify patients’ concerns, explain illness beliefs, monitor progress, ensure adherence, and address the social causes and the consequences of depression.28 The majority of those who experience traumatic events will heal spontaneously after reaching safety.53,54 Empathy, reassurance and advocacy are key clinical elements of the recovery process. Pushing for disclosure of traumatic events could cause more harm than good.

The children of ethnic minorities, including some recently settled immigrants and/or refugees, are disproportionately over-screened (up to 8.75 times more likely) and over-reported as positive (up to four times more likely) for child maltreatment.55 False-positive reports could result in harm, leading to psychological distress, inappropriate family separation, impaired clinician–patient rapport and legal ramifications associated with the involvement of child protection services.56 Routine screening is not recommended; rather, clinicians should remain alert for maltreatment, either intimate partner violence or child maltreatment.

Recommendations related to mental health and maltreatment, both physical and emotional, are summarized in Box 1C.

Box 1C: Summary of evidence-based recommendations for mental health and physical and emotional maltreatment*.

Depression

If an integrated treatment program is available, screen adults for depression using a systematic clinical inquiry or validated patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9 or equivalent).

Individuals with major depression may present with somatic symptoms (pain, fatigue or other nonspecific symptoms).

Link suspected cases of depression with an integrated treatment program and case management or mental health care.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Do not conduct routine screening for exposure to traumatic events, because pushing for disclosure of traumatic events in well-functioning individuals may result in more harm than good.

Be alert for signs and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (unexplained somatic symptoms, sleep disorders or mental health disorders such as depression or panic disorder).

Child maltreatment

Do not conduct routine screening for child maltreatment.

Be alert for signs and symptoms of child maltreatment during physical and mental examinations, and assess further when reasonable doubt exists or after patient disclosure.

A home visitation program encompassing the first two years of life should be offered to immigrant and refugee mothers living in high-risk conditions, including teenage motherhood, single parent status, social isolation, low socioeconomic status, or living with mental health or drug abuse problems.

Intimate partner violence

Do not conduct routine screening for intimate partner violence.

Be alert for potential signs and symptoms related to intimate partner violence, and assess further when reasonable doubt exists or after patient disclosure.

Note: PHQ-9 = nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

Order of listing considers clinical feasibility and quality of evidence.

Chronic and noncommunicable diseases

People of certain ethnic backgrounds (specifically Latin Americans, Africans and South Asians) face a twofold to fourfold higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus than white people,57 with earlier onset and poorer outcomes. People with hypertension have the most to gain from treatment of obesity, high cholesterol, hypertension and hyperglycemia. Culturally appropriate diabetes education and lifestyle interventions are effective in preventing the disease or improving disease management.58 Iron deficiency is the most common nutritional deficiency in the world,59 and immigrant women60 and children can benefit from screening and supplementation.

Dental disease is often challenging for medical practitioners, but screening and treating pain with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can lead to better outcomes and more effective referrals for oral health care.61 In addition, there is value in recommending twice-daily tooth-brushing with fluoridated toothpaste, as some immigrants may not be familiar with this approach to oral health.62 Loss of vision is the final common pathway for all eye diseases,63 and all immigrants can benefit from having their visual acuity assessed soon after arrival in Canada.

Recommendations for chronic and noncommunicable diseases are summarized in Box 1D.

Box 1D: Summary of evidence-based recommendations for chronic and noncommunicable diseases*.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Screen immigrants and refugees > 35 years of age from ethnic groups at high risk for type 2 diabetes (those from South Asia, Latin America and Africa) with fasting blood glucose.

Iron-deficiency anemia

Women

Screen immigrant and refugee women of reproductive age for iron-deficiency anemia (with hemoglobin).

If anemia is present, investigate and recommend iron supplementation if appropriate.

Children

Screen immigrant and refugee children aged one to four years for iron-deficiency anemia (with hemoglobin).

If anemia is present, investigate and recommend iron supplementation if appropriate.

Dental disease

Screen all immigrants for dental pain. Treat pain with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and refer patients to a dentist.

Screen all immigrant children and adults for obvious dental caries and oral disease, and refer to a dentist or oral health specialist if necessary.

Vision health

Perform age-appropriate screening for visual impairment.

If presenting vision < 6/12 (with habitual correction in place), refer patients to an optometrist or ophthalmologist for comprehensive ophthalmic evaluation.

Order of listing considers clinical feasibility and quality of evidence.

Women’s health

To prevent unintended pregnancy, screening for unmet contraceptive needs should begin soon after a woman’s arrival in Canada. Giving women their contraceptive method of choice (the intrauterine device being the most common contraceptive worldwide, although personal preferences vary), providing the contraceptive method on site and having a good interpersonal relationship all improve contraceptive-related outcomes.64

School vaccination programs vary by province, and immigrant girls and women may miss school programs for human papillomavirus vaccination, depending on their age at the time of arrival. Subgroups of immigrants, most notably South Asian and Southeast Asian women, have substantially lower rates of cervical cytology screening than Canadian-born women.65 Women who have never undergone cervical screening and those who have not had cervical screening in the previous five years account for 60%–90% of invasive cervical cancers. Providing information to patients, building rapport and offering access to female practitioners can improve acceptance of Papanicolau (Pap) testing.66

Finally, newly arrived pregnant women are at increased risk for maternal morbidity.67 We identified social isolation, risks of unprotected or unregulated work environments, and sexual abuse (specifically in forced migrants) as priority areas for research.

Recommendations related to women’s health are summarized in Box 1E.

Box 1E: Summary of evidence-based recommendations for women’s health*.

Contraception

Screen immigrant women of reproductive age for unmet contraceptive needs soon after arrival to Canada.

Provide culturally sensitive, patient-centred contraceptive counselling (giving women their method of choice, having contraception on site and fostering a good interpersonal relationship).

Vaccination against human papillomavirus

Vaccinate 9- to 26-year-old female patients against human papillomavirus.

Cervical cytology

Screen sexually active women for cervical abnormalities by Papanicolaou (Pap) test.

Information, rapport and access to a female practitioner can improve uptake of screening and follow-up.

Order of listing considers clinical feasibility and quality of evidence.

Knowledge translation

We developed a summary of our recommendations and have engaged multiple stakeholders as partners to share these recommendations with their constituencies, including the Public Health Agency of Canada, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, regional health and public health authorities, immigrant community groups and primary care practitioners. These recommendations and their related evidence reviews are available on the CMAJ website (see www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.090313/-/DC1). Forty primary care practitioners from across Canada with experience working with immigrants pilot-tested the recommendations, provided feedback on the presentation format and are helping to promote the guidelines through their networks. Finally, we sought feedback on our recommendations from our immigrant community partners (specifically, the Edmonton Multicultural Health Brokers Cooperative, which represents 16 ethnic communities) and continue to work with our community partners to improve access to health services.

Directions for future research

Immigrant populations are a heterogeneous group. Because of the selection processes that are in place, most immigrants arrive in good health, although some subgroups are at increased risk of chronic and infectious diseases and mental illness. More research is needed on strategies to address barriers to health services, most urgently for refugees, women and other immigrants with low income and language barriers. There is also a need to develop and study interventions for social isolation for pregnant immigrants and refugees. Data remain limited for immigrant children, refugee claimants and nonstatus persons and for many disease areas, including malaria morbidity, post-traumatic stress disorder and interventions for intimate partner violence.

More work must be done to improve immigrants’ access to health services. We hope this evidence-based initiative will provide a foundation for improved preventive health care for immigrant populations.

For a summary of recommendations and clinical considerations, see Appendix 2, at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.090313/-/DC1.

Podcasts for practitioners and additional information for patients can be found at www.ccirhken.ca.

2. Selection of potentially preventable and treatable conditions

Community-based primary health care practitioners see most of the immigrants and refugees who arrive in Canada. This is not only because Canada’s health care system centres on primary care practice, but also because people with lower socioeconomic status, language barriers and less familiarity with the system are much less likely to receive specialist care.68

Guideline development can be costly in terms of time, resources and expertise.69 Setting priorities is critical, particularly when dealing with complex situations and limited resources.70 There is no standard algorithm on who should determine top priorities for guidelines or how this should be done, although burden of illness, feasibility and economic considerations are all important.71 Stakeholder engagement, to ensure relevance and acceptability, and the use of an explicit procedure for developing recommendations are critical in guideline development.72–74 We chose primary care practitioners, particularly those who care for immigrants and refugees, to help the guideline committee in selecting conditions for clinical preventive guidelines for immigrants and refugees, with a focus on the first five years of settlement. A more detailed description of this Delphi process was published previously.15

Methods

We used a modified Delphi consensus process to select 20 high-priority conditions for guideline development.70,75,76 To begin, we identified key health conditions using an environmental scan, literature review and input from key informants from the Canadian Initiative to Optimize Preventive Care for Immigrants national network, a nascent network of immigrant health providers. This initial step identified 31 conditions. During the ranking process, survey participants were invited to list additional conditions. These conditions, if associated with potentially effective clinical preventive actions, were integrated into the pool of conditions for subsequent ranking.

We developed priority-setting criteria that emphasized inequities in health, building on a process developed for primary care guidelines affecting disabled adults.70,77 Importance or burden of illness is often used for setting priorities, usefulness or effectiveness is frequently used, and disparity is now a well-recognized component of many public health measures.78 We defined our criteria as importance, usefulness and disparity:

Importance: Conditions that are the most prevalent health issues for newly arriving immigrants and refugees; conditions with a high burden of illness (e.g., morbidity and mortality).

Usefulness: Conditions for which guidelines could be practically implemented and evaluated. Such guidelines refer to health problems that are easy to detect, for which the means of prevention and care are readily available and feasible, and for which health outcomes can be monitored.

Disparity: Conditions that might not be currently addressed or that are poorly addressed by public health initiatives or illness-prevention measures that target the general population.

We (H.S., K.P., M.R., L.N.) purposively selected 45 primary care practitioners, including family physicians and nurse practitioners, recently or currently working in a setting serving recent immigrants and refugees. We sampled clinical settings from 14 urban centres across Canada to ensure in-depth experience with a variety of migrants. The settings also covered a range of health service funding models: community health centres (centres locaux de services communautaires in Quebec), refugee clinics, group and solo practices, and ethnic community practices. We aimed to select practitioners with substantial experience, academic expertise or local leadership roles who were willing to commit to offering future input into guideline development and dissemination.

Immigrant and refugee health is a new subdiscipline. The skills, knowledge and experience that define expertise have not yet been determined, and there are no examinations, certification or developed courses that can be used as a proxy for expertise. We believed that contextual knowledge, experience arising from engaged care of immigrants and refugees in Canada, and related work experience in international health were important factors in determining expertise. As a measure of expertise, we adapted a formula used by Médecins Sans Frontières. This criterion combines work with Médecins Sans Frontières in developed countries and in the field. Our criterion for experience was set at seven years or more and included all work in developing countries. It was calculated as number of years of experience with migrants in Canada + (2 × years of experience working in developing countries).

As prompts for decision-making, we asked our practitioner panel to make choices based on the defined criteria, imagining that the guidelines under development might be used at a clinic serving new immigrants or by physicians who do not often see immigrant and refugee patients. Just as clinical practice does, these criteria challenged practitioners to make choices based on competing demands.

This first round of the Delphi survey aimed to ensure that we had the appropriate health conditions under consideration and to begin developing some consensus as to priorities. Participants were asked to rank the 31 conditions identified initially and to propose conditions that were not on the initial list. We chose an a priori cut-off of 80% consensus for inclusion in the top 20. In the second round, we presented an unranked, modified version of this list, excluding all conditions that had already reached 80% consensus and adding newly proposed conditions. The remaining conditions to be included in the top 20 were determined by overall ranking in the second round. This list was reviewed by the codirectors of the Edmonton Multicultural Health Brokers Co-operative (www.mchb.org/OldWebsite2008/default.htm), a group representing over 16 ethnic communities that had initially requested preventive health guidance relevant for immigrant communities. In addition, the panel of experts who would be developing the guidelines reviewed the list. Then, during the final round, we requested approval, through a simple agree/disagree vote, of the process and the resulting list of priorities, with one-on-one interviews to resolve concerns in the two months following the ranking process.

Consent to participate in the Delphi survey was determined by completion of a questionnaire. Demographic questions elicited personal, professional and practice characteristics of the study participants. With each round, we sent to participants (by email) an explanation of the process to date, the priority-setting criteria, instructions for filling out the survey and a link to the SurveyPro survey. Telephone follow-up was used to maximize response rate. We used Microsoft Excel for the analysis.

Results

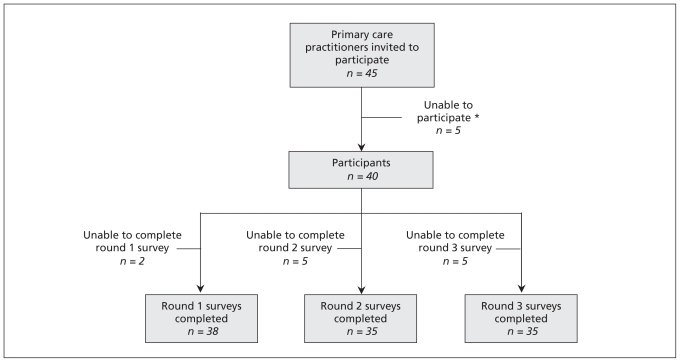

Ninety per cent (40/45) of the selected practitioners agreed to participate. Four of the five participants who chose not to participate cited reasons of leave of absence or sabbatical leave, and the fifth cited workload. Ninety-five per cent of the consenting participants completed the first round of the survey, and 88% completed the second and third rounds (Figure 2A). The first two rounds of the Delphi consensus process took place between Mar. 5 and May 31, 2007.

Figure 2A:

Participant sampling and response rate. *One person was on sabbatical, three were on a leave of absence and one cited workload. Adapted, with permission, from Swinkels and associates.15

The 40 participants consisted of 35 physicians and five nurse practitioners or nurses with expanded roles. Participants were predominantly women and had been in practice for an average of 14 years. They worked an average of 16 hours per week with immigrants and refugees. More than 80% spoke two or more languages (Table 2A).

Table 2A:

Demographic characteristics of 40 participants in Delphi consensus process*

| Characteristic | No. (%) of participants† |

|---|---|

| Sex, female (n = 40) | 25 (62) |

| Age, yr, mean | 42.5 |

| Length of practice, yr, mean | 14.0 |

| Province of practice (n = 40) | |

| British Columbia | 7 (18) |

| Prairies (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba) | 4 (10) |

| Ontario | 17 (42) |

| Quebec | 8 (20) |

| Maritime (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador) | 4 (10) |

| Type of practice (n = 39) | |

| Solo | 2 (5) |

| Group (excluding those in a community health centre) | 19 (49) |

| Community health centre | 18 (46) |

| Level of cross-cultural exposure and expertise | |

| Experience working with immigrants or refugees, mean, yr | 7.5 |

| Medical experience in low- and middle- income countries (n = 39) | 25 (64) |

| ≥ 7 years’ experience (criteria adapted from Médecins Sans Frontières) (n = 40) | 26 (65) |

| Bilingual (n = 40) | 33 (82) |

| Speaks more than 2 languages (n = 40) | 17 (42) |

Adapted, with permission, from Swinkels and associates.15

Except where indicated otherwise.

The average length of experience working with refugees and immigrants in Canada was 7.5 years; 64% of participants had some experience working in developing countries, with a median overseas duration of 16 (range 1–120) months. Thirty-one per cent of primary care practitioners self-identified as being an immigrant or refugee; of the remainder, 38% self-identified as being the child of an immigrant or refugee (of the 35 practitioners who responded to this optional question).

Forty-five per cent of participants identified themselves as having had prior training in the field, which included accredited tropical medicine courses, designated rotations during residency, work exposures before becoming a health care practitioner, and conferences or self-directed studies in multicultural or cross-cultural medicine.

The refugees and immigrants with whom most practitioners interacted came from all parts of the world; using an average of straight ranking (1 to 6) of regions, south and central Africa was estimated as the most frequent source region of immigrants for these practitioners. Children formed, on average, 30% of clientele, and women, 41%. Seventy-one per cent of migrants were estimated to have been in Canada less than five years, and 73% were involuntary migrants. Involuntary migrants included refugee claimants, so-called Convention Refugees and internally displaced persons (although this is not really an issue for Canada).

Box 2A lists the top 20 conditions for which practitioners identified a current need for guidelines on the basis of our criteria. In the first round, 80% consensus was reached to include 11 conditions. Eighty per cent consensus was also reached to exclude three conditions from the process: Chagas disease, colon cancer and prostate cancer. Three well-defined and unique conditions were proposed for the second round of ranking: osteoporosis, contraception and vision screening. The nine conditions selected in the second round were based on average ranking (Box 2A).

Box 2A: High-priority conditions.

Abuse and domestic violence*

Anxiety and adjustment disorder*

Cancer of the cervix

Contraception

Dental caries, periodontal diseases*

Depression*

Diabetes mellitus*

Hepatitis B*

Hepatitis C

HIV/AIDS*

Intestinal parasites*

Iron-deficiency anemia*

Malaria

Measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio and Hib disease

Pregnancy screening

Syphilis

Torture and post-traumatic stress disorder*

Tuberculosis*

Varicella (chicken pox)

Vision screening

Conditions identified by consensus in first round (the rest were selected in the second round).

The list of top 20 conditions was reviewed and approved, with one modification, by the panel of key experts who would be developing the guidelines: routine vaccine-preventable diseases were considered a single priority, with tetanus, diphtheria and polio combined with measles, mumps and rubella for the purposes of guideline development. As a final step, we sent the 20 identified conditions to survey participants for approval and discussion; all 35 people who participated in this round approved (i.e., 88% of the 40 original participants).

Discussion

Refugees and many immigrants may have poor or deteriorating health, because of conditions experienced before, during or after arrival to Canada. A health care system that is poorly adapted to their needs compounds this situation, resulting in further marginalization. Our Delphi consensus process used practitioners’ years of field experience strategically to identify preventable and often unrecognized clinical care gaps that can result from such majority-system biases.

An overarching goal of our guideline development project was to supplement guidelines that exist for the general Canadian population79 by focusing on health inequities. We therefore selected a high proportion of practitioners who work with refugees, a particularly vulnerable subgroup of immigrants prone to disparities. Using practitioners to select conditions ensured both that the needs of the future guideline-users were given priority and that conditions presenting serious clinical challenges, but that might be under-represented in the literature, were included. In working with perceived needs of practitioners, we risked a reporting bias: overemphasizing popular stereotypes (e.g., the importance of infectious diseases), underemphasizing unrecognized or emerging conditions (e.g., vitamin D deficiency)80 and loss of precision in terms of specific populations (e.g., our list does not fully reflect the greatest needs of children).81 Also, by deliberately selecting participants who work with refugees, we risked falsely stereotyping the health status of all immigrants by overemphasizing refugee-specific conditions and, conversely, by underemphasizing common heath risks, such as hypertension, that affect all immigrants.

The Delphi process generated 20 conditions for guideline development that reflected the needs and priorities of primary care practitioners working with immigrants and refugees. Although immigrant screening has historically focused on infectious diseases,82 the conditions selected by survey participants extended across a spectrum of diseases, including infectious disease, dentistry, nutrition, chronic disease, maternal and child health, and mental health. Mental health conditions were rated particularly high, and all four of the proposed mental health conditions reached 80% consensus in the first round of the Delphi survey. Four infectious diseases and three chronic diseases also reached 80% consensus. The inclusion of dental caries and periodontal disease in the top 11 conditions is notable, reflecting important cultural, as well as socioeconomic, barriers that refugees and immigrants face in access to dental care.83 This range of conditions suggests that immigrant and refugee medicine covers the full spectrum of primary care. Although infectious disease continues to be an important area of concern, we are now seeing mental health and chronic diseases as key considerations for recently arriving immigrants and refugees.

Take-home messages

Preventable and treatable, but often-neglected, health conditions were selected for the development of guidelines for immigrant populations made vulnerable because of health system bias. Criteria that emphasized addressing inequities in health helped in identifying gaps in clinical care. This evidence-based guideline initiative marks the evolution of immigrant and refugee medicine from a focus on infectious diseases to a more inclusive consideration of such chronic diseases as mental illness, dental disease, diabetes mellitus and cancer. We hope that this practitioner engagement process will improve the practicality of the evidence-based guidelines, help practitioners who already to work in the area to target and streamline their efforts, and encourage new practitioners to enter this challenging and interesting discipline.

For the complete description of the Delphi consensus process, see www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.090290.

3. Evaluation of evidence-based literature and formulation of recommendations

A variety of methods are used for developing clinical guidelines and practice recommendations.84 We used the recently developed approach of moving away from recommendations classified by letters and numbers to the simplified classification system recommended by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group85 and applied this to clinical preventive actions. Our guideline development process followed the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) instrument (www.agreetrust.org), which is recognized internationally as providing best-practice criteria for evidence-based guideline development.

We developed our recommendations on the basis of a pre-specified process overseen by the guideline committee of the Canadian Collaboration on Immigrant and Refugee Health. Defining a methods process ensured that each guideline was developed in a systematic, reproducible manner and was based on the best evidence available. This process was based on existing guidelines, including the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) handbook on developing clinical practice guidelines84 and the ADAPTE framework for adapting existing guidelines.86 Our process emphasized identifying immigrant- and refugee-specific evidence on efficacy and population characteristics from guidelines, systematic reviews and primary studies. When immigrant- and refugee-specific evidence was unavailable, we used specific criteria, adapted from the Cochrane Handbook,87 to judge how this evidence applied to our intended target population.

Conditions considered most important by practitioners caring for immigrants and refugees in Canada were assigned to groups of content experts, who were asked to develop evidence reviews with clinical conclusions for recent immigrants and refugees to Canada using a logic model and following a structured 14-step process. The guidelines focus on clinical care gaps84 during the “health settlement period,” which we define as the first five years of residence in a new country for an immigrant or refugee. This is the period during which health practitioners are likely to have initial contact with this population and the time during which stressors from a person’s country of origin and country of settlement are most likely to manifest. Immigrants and refugees are thus grouped together by this organizing period of resettlement; however, the heterogeneity, complexities and differences between and within these groups were recognized throughout the process.

In our process, we emphasized making clinically relevant recommendations and establishing an extension to existing guidelines rather than a replacement or revision.

Methods

We used the AGREE checklist to guide the overall development process: a panel of experts and a guideline committee set the scope and purpose of the guidelines, and stakeholders were engaged to select priority conditions and to merge recommendations. To ensure rigour and applicability, we developed 14 standardized steps (described below and summarized in Box 1A in section 1 of this article, above). The guideline committee and other guideline experts and practitioners provided feedback to improve clarity of presentation. We accepted funding only from university and government sources, to ensure editorial independence. Here we describe the steps in our standardized evidence review.

Step 1: Develop clinician summary table

A standardized clinician summary template was used in setting the framework for each selected condition. During subsequent steps, this clinician summary table was used to focus development of the preventive guidelines, on the basis of the condition’s prevalence in the population of interest, population-specific clinical considerations (e.g., stigma and awareness of screening and treatment options), clinical actions upon migration, screening tests, screening interval or timing, and treatment.

Step 2: Develop logic model and key questions

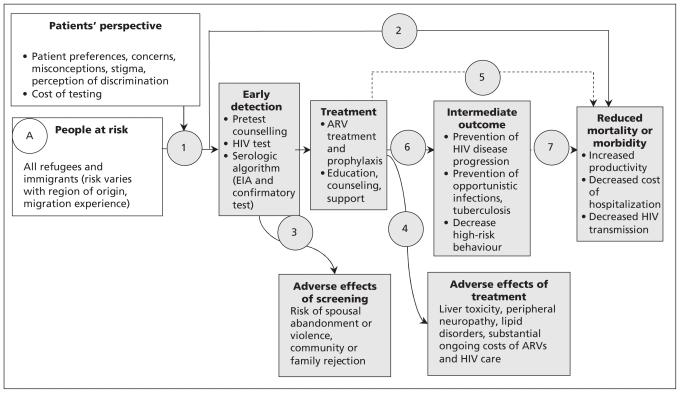

Our logic model, which illustrates a plausible causal pathway for each guideline, was adapted from the US Preventive Services Task Force,88 with the addition of a box to consider patient perspectives (for an example, see Figure 3A). The logic model outlines the population of interest (immigrants and refugees); the intervention (i.e., screening); the target condition; adverse effects of screening, diagnosis and treatment; treatment options and outcomes; and the link between treatment and reductions in morbidity and mortality. The model illustrates how identification of the condition can be expected to lead to treatment and reduced morbidity and mortality in the population of interest. This logic model identified the need to consider whether intermediate outcomes would be accepted as the basis for the recommendations, and if so, the strength of association between intermediate and clinical outcomes. For example, high-risk behaviour is an intermediate outcome in reducing morbidity and mortality from HIV.

Figure 3A:

Sample logic model for HIV (adapted from US Preventive Services Task Force).88 Open rectangles designate the potential screening population and patient factors to be considered; shaded rectangles designate interventions and related outcomes; and circles and numbers provide points in the evidence chain that were used to develop the search questions. Note: ARV = antiretroviral, EIA = enzyme immunoassay.

Review group leaders were asked to use this logic model to define the PICO (population, intervention, comparison and outcome) format for each clinical action. These elements guided the search for evidence.

Step 3: Set the stage for admissible evidence

We followed the process used by the US Preventive Services Task Force and the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care to focus on evidence most critical to making a recommendation.84 We began with searches of specific guidelines and systematic reviews for the target population of immigrants and refugees, to document the current state of direct evidence. We extended these searches to capture evidence from the general population. The search strategy was modelled on that used by the Cochrane Collaboration89 and was conducted by one of two clinical librarians. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, PreMEDLINE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, Embase, CINAHL, National Guideline Clearing House and the CMA Infobase. We also searched the databases and publications of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, the US Preventive Services Task Force, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization. We asked authors to create flow charts of their searches, using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)90 framework as a template.

Step 4: Assess eligibility of systematic reviews

Two members of the review group independently reviewed the search strategies, abstracts and relevant full-text articles on the basis of the inclusion criteria and specified outcomes of interest.

Data from each eligible systematic review were extracted and documented in a table with the following headings: author and year, objective, number and types of studies included, setting, participants, intervention and findings. If no eligible systematic review was found, then the review group team searched for the next best available study (randomized controlled trials, observational studies) that addressed the question.

Step 5: Search for data specific to immigrant and refugee populations

A tailored search process was used to gather information on population-specific considerations relevant to immigrants and refugees in the following areas:

baseline risk (prevalence) versus the Canadian general population

rate of clinically important beneficial and harmful outcomes (e.g., mortality, morbidity)

genetic and cultural factors (e.g., knowledge, attitudes, practices, cultural preferences, dietary preferences)

compliance variation (e.g., physicians’ and patients’ adherence to recommendations)

Step 6: Refocus on key clinical preventive actions and key questions

After reviewing the literature and available evidence, review group teams were asked to focus on the most relevant clinical action(s) and immigrant and refugee subpopulation(s) and to select three or fewer candidate recommendations with added value over and above existing guidelines.

Step 7: Assess quality of systematic reviews

For each recommendation, all relevant systematic reviews were compared to ensure consistency among findings. If the conclusions of the systematic reviews were consistent, the most recent review was selected. Any inconsistencies in reviews were explicitly addressed: reasons for inconsistencies, including the evidence base or the interpretation, were explored, and the most appropriate systematic review was selected, considering the purposes of these guidelines.

The most relevant systematic reviews were then assessed for quality to ensure they met the four criteria assessed in the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (formerly the Health Development Agency) critical appraisal tool for evidence-based briefings or reviews of reviews:91 systematicity (the review must apply a consistent and comprehensive approach), transparency (the review must be clear about the processes involved), quality (the review must have appropriate methods and analysis) and relevance (the review must be relevant in terms of focus; i.e., populations, interventions, outcomes and settings).

Step 8: Search for evidence to update selected systematic reviews

To find new primary studies published since the selected systematic review, a search was conducted using the same approach as in step 3.

Step 9: Assess eligibility of new studies

As in step 4, two reviewers independently screened for relevant studies and then assessed each study for eligibility. Each relevant study was summarized to describe study design, the clinical intervention, details about length of intervention and follow-up, outcomes, population characteristics and data analysis.

For studies evaluating the effectiveness or safety of treatment or screening, the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group’s data collection checklist92 and the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale93 for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses were used to assess study limitations.

Step 10: Integrate data from updated search

Any new relevant and eligible studies that could modify or substantially strengthen the conclusions of the “reference” systematic review were assessed and added to the worksheet.

Step 11: Synthesize final evidence bank and draft two key clinical actions

The review group teams synthesized the evidence from the updated systematic reviews, explicitly incorporating clinical considerations and value judgments specific to immigrant and refugee populations to draft preferably no more than two key clinical actions, targeting (where necessary) specific populations or regions.

Step 12: Develop table for summary of findings

Both desirable and undesirable effects of the intervention were summarized, in both absolute and relative terms, for each patient-important outcome using the summary-of-findings table format adopted by the Cochrane Collaboration.94 The quality for each outcome was assessed using the items specified by the GRADE Working Group (indirectness, consistency, precision, reporting bias and study limitations) (Box 3A). Observational studies that met these five criteria were upgraded if they also met one of three additional criteria (dose–response, influence of confounding variables, large effect).85 A separate table was developed for each clinical action or question. For dichotomous outcomes, relative risks or odds ratios were extracted from the reference systematic review (or next best available study). Number needed to treat for one person to benefit was calculated as 1/(control event rate × [1 – relative risk]). The control event rate was taken from the control group of the reference systematic review or best available study.

Box 3A: Grades of evidence of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group (www.gradeworkinggroup.org).

High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate.

Step 13: Identify gaps in evidence and needs for future research

The review group teams identified gaps in the literature and outlined recommendations for future research on such topics as implementation, inequalities and vulnerable groups, cost-effectiveness and implications of applying the recommendations in health care settings.

Step 14: Develop clinical preventive recommendations

For each condition, the guideline committee reviewed the clinician summary table, the logic model and the summary-of-findings tables and met with the review group leader to clarify details. Then, for each key clinical action, the guideline committee discussed each of the issues in the GRADE system (see Table 1B in section 1 of this article, above):16–18 the balance between desirable and undesirable effects (the relative importance of burden, benefits and harms), quality of the available evidence, and values and preferences. We explicitly decided not to use cost and feasibility in judging the basis of the recommendation because we did not have sufficient confidence in the data. Rather than report the strength of the recommendation as weak or strong, the guideline committee chose to make the recommendation only in the event of net benefits and to report the basis for the recommendation, to provide clinicians with key information to consider when selecting or discussing the preventive recommendation with a patient. The guideline committee took votes if the agreement was not unanimous, and the majority prevailed.

Discussion

This 14-step process was useful for ensuring sufficient uniformity among the transdisciplinary teams for each condition. Specifically, this systematic approach enabled the review group teams to meet the requirements of the GRADE quality-assessment process and the steering group to apply the GRADE recommendation process. These steps were also designed to conform with AGREE, the current quality standard for guidelines. We worked with each review group leader and team to ensure we met the 23 AGREE criteria in six domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity and presentation, applicability and editorial independence.16

Take-home messages

We combined the AGREE best-practice framework, the current quality standard for guidelines, with the recently developed GRADE approach to quality assessment to develop evidence-based clinical preventive guidelines for immigrants and refugees to Canada. Here, we have documented the systematic approach used to produce the evidence reviews and apply the GRADE approach. The 14-step approach included building on evidence from previous systematic reviews, searching for and comparing evidence between general and specific immigrant populations, and applying the GRADE criteria for making recommendations. The basis of each recommendation (balance of benefit and harm, quality of evidence, values) is stated explicitly to ensure transparency.

For a more complete description of the evaluation of the literature and formulation of recommendations, see www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.090289.

4. Measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus and polio

Vaccination is one of the most beneficial and cost-effective measures for preventing disease.95,96 Before routine vaccination, the annual burden of measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus and polio in the United States and Canada was considerable. The incidence of and mortality from these diseases have been reduced sustantially: by more than 99% for measles, rubella, diphtheria and polio, by more than 95% for mumps, and by more than 92% for pertussis and tetanus relative to annual morbidity and mortality before introduction of the corresponding vaccines.97 Despite these successes, the recent outbreaks of pertussis in California, outbreaks of mumps in the United States and Canada in 2005–2006 and the ongoing transmission of polio in the past five years, with recent spread to Tajikistan, highlight the need to maintain high levels of herd immunity and to identify and vaccinate susceptible groups so that outbreaks can be prevented.98,99 Almost 20% of the Canadian population is foreign born,100 and in the past 30 years the majority of these people (more than 70%) have originated from countries where vaccination coverage may be suboptimal or where several of the childhood vaccines that are routine in Canada are not part of the national vaccination schedule.101 Immigrants are therefore likely to be an unrecognized group at risk for childhood vaccine-preventable diseases. We conducted an evidence review to guide primary care practitioners in the need to assess and update childhood vaccination in the immigrant population. The recommendations of the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health on updating vaccines are outlined in Box 4A.

Box 4A: Recommendations from the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health: vaccine-preventable diseases.

| Measles, mumps and rubella | Diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus and polio |

| Vaccinate all adult immigrants without immunization records using one dose of measles–mumps–rubella vaccine. | Vaccinate all adult immigrants without immunization records using a primary series of diphtheria, tetanus and inactivated polio vaccine (three doses), the first of which should include acellular pertussis vaccine to also protect against pertussis. |

| Vaccinate all immigrant children with missing or uncertain vaccination records using age-appropriate vaccination for measles, mumps and rubella. | Vaccinate all immigrant children with missing or uncertain vaccination records using age-appropriate vaccination for diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus and polio. |

| Basis of recommendations | Basis of recommendations |

| Balance of benefits and harms | Balance of benefits and harms |

| Childhood vaccination programs have dramatically decreased the incidence of and associated mortality from measles, mumps, rubella and congenital rubella (absolute difference of 95.9%–99.9% in reduction of cases and 100% in reduction of deaths). Serious adverse events, including autism (relative risk 0.92, 95% confidence interval 0.68–1.24), are not significantly associated with measles–mumps–rubella vaccine. Mumps and rubella are not part of routine vaccination programs in most source countries of origin for the majority of new immigrants. A large proportion of adult immigrants may be susceptible to rubella (20%–30%) and at risk for having a child with congenital rubella syndrome. | Childhood vaccination programs have dramatically decreased the incidence of and associated mortality from diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus and polio (absolute difference of 92.9%–99.9% in reduction of cases and 99.2%–100% in reduction of deaths) relative to the prevaccination period, without associated increases in serious adverse events. A large proportion of adult immigrants are susceptible to tetanus (40%–50%) and diphtheria (about 60%), and the proportion susceptible increases for both with increasing age. To prevent individual morbidity and mortality and to prevent outbreaks, susceptible individuals must be identified and vaccinated. |

| Quality of evidence | Quality of evidence |

| High | High |

| Values and preferences | Values and preferences |

| The committee attributed more value to preventing the risk of outbreaks and the individual burden due to these diseases and less value to the cost of vaccination. | The committee attributed more value to preventing the risk of outbreaks and the individual burden due to these diseases and less value to the cost of vaccination. |

Methods

We used the 14-step method developed by the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health16 (summarized in section 3 of this article, above). We considered the epidemiology of measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus and polio in immigrant populations and defined clinical preventive actions (interventions), outcomes and key clinical questions. We searched MEDLINE (Ovid), MEDLINE InProcess, Embase, CINAHL and the Cochrane Library from Jan. 1, 1950, to Jan. 14, 2010, for studies pertinent to immigrants and from Jan. 1, 1997, to Jan. 14, 2010, for studies pertinent to the general population. Detailed methods, search terms, case studies and clinical considerations can be found in the complete evidence review for this topic (Appendix 3, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.090313/-/DC1).

Results

In the search for systematic reviews and guidelines for immigrants regarding measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus and polio, we identified and screened 242 records, of which none met the eligibility criteria. In the search for systematic reviews and guidelines involving these diseases in the general population, we identified 6293 articles, of which 24 met the eligibility criteria. A search for articles reporting information about admission to hospital and mortality associated with measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus and polio identified 3888 articles (after duplicates were removed), of which 59 were relevant, and one of these was critical for this review97 (Table 4A). In addition, a search for articles about immigrants and measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus and polio identified 1177 articles (duplicates removed), of which 54 were relevant, addressing the following areas: epidemiology, prevaccination screening, knowledge and compliance, treatment and vaccination in the immigrant population.

Table 4A:

Summary of findings for vaccination to prevent rubella and tetanus

| Patient or population: General population |

| Setting: United States |

| Intervention: Vaccination, measles–mumps–rubella or diphtheria–tetanus |

| Comparison: Historical comparisons |

| Source: Roush SW, Murphy DG; Vaccine-Preventable Disease Table Working Group. Historical comparisons of morbidity and mortality for vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States. JAMA 2007;298:2155–63.97 |

| Outcome | Absolute effect | Relative effect | No. of participants (studies) | GRADE quality of evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk for control group (annual average) | Difference with vaccination | ||||

| Rubella | |||||

| Cases, rubella | 47 745 (for 1966–1968) | 47 734 fewer cases (for 2006) | Absolute difference: 99.9% reduction | NA (1) | High*† |

| Cases, congenital rubella syndrome | 152 (for 1966–1969) | 151 fewer cases (for 2006) | Absolute difference: 99.3% reduction | NA (1) | High*† |

| Deaths | 17 (for 1966–1968) | 17 fewer deaths (for 2006) | Absolute difference: 100% reduction | NA (1) | High*† |

| Tetanus | |||||

| Cases | 580 (for 1947–1949) | 539 fewer cases (for 2006) | Absolute difference: 92.9% reduction | NA (1) | High*† |

| Deaths | 472 (for 1947–1949) | 468 fewer deaths (for 2004) | Absolute difference: 99.2% reduction | NA (1) | High*† |

Note: GRADE = Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; NA = not applicable.

Only one study.

Reduction in absolute numbers > 90%.

What is the burden of vaccine-preventable disesases in immigrant populations?

A large proportion of immigrants and refugees, particularly adults, are likely to be susceptible to vaccine-preventable diseases because of underimmunization, waning immunity or both. Underimmunization likely plays an important role, given that vaccine coverage globally ranges from 50% to 90%, that routine childhood vaccination began only in the mid-1970s and that rubella and mumps vaccines are not administered routinely in most developing countries.101 Given the progress in global vaccination coverage, immigrant children and adolescents are more likely than their parents to have received vaccines that are part of the World Health Organization Extended Program on Immunization (measles, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio, bacille Calmette-Guérin), but many may not have received other vaccinations that are part of the routine childhood vaccination program in Canada (mumps, rubella, varicella, Hemophilus influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae). Many immigrants, especially adults, do not have vaccination records, and even when present, more than 50% of such records may not be current according to the host country’s vaccination schedules.38,102 Seroprevalence studies consistently have shown that a large proportion of adult immigrants are susceptible to rubella (about 80%–85% immune but as low as 75%) and tetanus (about 50%–60% immune among those 20–30 years of age, but decreasing with increasing age).37,38,103,104 A higher-than-expected proportion of immigrants are involved in rubella outbreaks, and most reported cases of congenital rubella syndrome and neonatal tetanus have occurred in children born to unimmunized foreign-born mothers.105,106 In adult immigrants, seroprevalence studies of measles (> 95% immune) and mumps (80%–92% immune but as low as 70%) have generally shown adequate antibody levels, with some exceptions.38,107 However, immigrants have not been over-represented in recent measles and mumps outbreaks.98,108 Diphtheria seroprevalence in immigrants is low (range 35%–50%) and generally decreases with age.37,104 To maintain herd immunity in the population, certain threshold levels of antibodies need to be maintained: 91%–94% for measles, 90%–92% for mumps, 83%–85% for rubella, 80%–85% for diphtheria, 80%–85% for polio and 90%–94% for pertussis.109,110 Immigrants likely fall below this threshold for rubella and diphtheria, and a large proportion are also susceptible to tetanus and at risk for the morbidity and mortality associated with this disease.37,38,103,104 Any population in which a large proportion of individuals are susceptible to vaccine-preventable disease will be at risk for disease transmission. High-risk groups must therefore be identified so that targeted vaccination programs can be formulated and implemented.

Does vaccination against specific vaccine-preventable diseases decrease associated morbidity and mortality?

Relative benefits and harms of vaccination

In the prevaccination era, diseases such as measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, smallpox and polio were very frequent and were a major cause of morbidity and mortality. These diseases also had enormous societal and economic costs, including time off school and work, physician visits and admissions to hospital. Childhood vaccination programs have decreased the morbidity from these diseases by more than 92%–99% and mortality by more than 99%.97 Childhood vaccination programs have repeatedly been found to be one of the most cost-effective medical interventions.96

Measles, mumps and rubella

Measle–mumps–rubella vaccine is highly effective against measles and rubella. Almost 100% of individuals are protected against measles after two doses, and more than 95% are protected against rubella after a single dose, with antibodies persisting for at least 15 years.95,111 The effectiveness of mumps vaccine is lower and depends on the vaccine strain used, the time since vaccination and possibly the genotype of the wild type.112 In the recent US outbreaks, the effectiveness of mumps vaccine was estimated to be as low as 64% after one dose and 79% after two doses (Jeryl Lynn strain).112 Measle–mumps–rubella vaccine has been associated with fever (about 5%), febrile convulsions (0.3%), benign thrombocytopenia purpura (< 0.01%), parotitis (rarely) and arthritis (up to 25% in postpubertal women), usually within two weeks of vaccination.111,113,114 The frequency of adverse reactions in seronegative women, however, is higher among those who have never been vaccinated than among revaccinated seronegative women.111 In 1998 Wakefield and colleagues115 published a case series of 12 children with development disorders and chronic gastrointestinal inflammation, which sparked widespread concern that measles–mumps–rubella vaccine was associated with autism. In 2010, The Lancet fully retracted this paper from the published record, after it became clear that several elements of the paper were incorrect. In addition, several subsequent studies have shown no association between measles–mumps–rubella vaccine and autism, including a population-based study of all Danish children born from 1991 to 1998 (> 500 000 individuals) (relative risk 0.92, 95% confidence interval 0.68–1.24).116

Diphtheria, acellular pertussis, tetanus and polio