Abstract

Influenza A virus uses cellular protein transport systems (e.g., CRM1-mediated nuclear export and Rab11-dependent recycling endosomes) for genome trafficking from the nucleus to the plasma membrane, where new virions are assembled. However, the detailed mechanisms of these events have not been completely resolved, and additional cellular factors are probably required. Here, we investigated the role of the cellular human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Rev-binding protein (HRB), which interacts with influenza virus nuclear export protein (NEP), during the influenza virus life cycle. By using small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and overexpression of a dominant negative HRB protein fragment, we show that cells lacking functional HRB have significantly reduced production of influenza virus progeny and that this defect results from impaired viral ribonucleoprotein (vRNP) delivery to the plasma membrane in late-stage infection. Since HRB colocalizes with influenza vRNPs early after their delivery to the cytoplasm, it may mediate a connection between the nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery and the endosomal system, thus facilitating the transfer of vRNPs from nuclear export to cytoplasmic trafficking complexes. We also found an association between NEP and HRB in the perinuclear region, suggesting that NEP may contribute to this process. Our results identify HRB as a second endosomal factor with a crucial role in influenza virus genome trafficking, suggest cooperation between unique endosomal compartments in the late steps of the influenza virus life cycle, and provide a common link between the cytoplasmic trafficking mechanisms of influenza virus and HIV.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza A virus is a highly contagious respiratory pathogen responsible for up to 0.5 million deaths annually (43). Seasonal epidemics are punctuated by rare but recurring pandemics, and recently, highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses have caused human infections with high fatality (∼60%) (42). These threats, along with the potential emergence of an influenza virus strain with both high transmissibility and high pathogenicity, emphasize the importance of controlling influenza viruses to promote global health. To achieve this, more detailed knowledge of how viruses replicate and interact with their hosts is needed. Any essential replication mechanism or host molecule interaction could be exploited for use in the development of novel prevention or intervention strategies. Recent studies have revealed that host molecules are required for influenza virus genome transport to newly forming virions (2, 10). Here, we aimed to clarify the mechanisms of influenza virus genome trafficking further.

Viral ribonucleoprotein (vRNP) complexes are the genetic elements of influenza virus, and their incorporation into budding virions is a prerequisite for the formation of infectious viruses. vRNPs are composed of individual negative-sense viral RNAs (vRNA) associated with viral nucleoprotein (NP) and the heterotrimeric polymerase complex (PB2, PB1, and PA). A set of eight vRNPs, representing the eight unique genome segments, is required for an influenza A virus to be infectious. Upon infection, vRNPs within virions are released from endosomes and transported to the nucleus, where they serve as templates for the production of viral protein-encoding mRNAs and positive-sense cRNAs. Subsequently, the cRNAs serve as templates for vRNA synthesis. In late-stage infection, new vRNPs are assembled in the nucleus and must undergo both nuclear export and transport across the cytoplasm to gain access to the viral budding sites at the plasma membrane.

Influenza virus utilizes cellular protein trafficking systems to facilitate the journey of vRNPs from the nucleus to the plasma membrane. vRNP nuclear export ensues through the coordinated actions of the M1 matrix protein (which associates with vRNP), the cellular CRM1 nuclear export receptor, and the viral nuclear export protein (NEP) (6, 11, 22–24, 27, 31, 35, 38, 40). NEP encodes a nuclear export signal, binds CRM1 and M1, and is thought to bridge the complex between M1-vRNP and the cellular nuclear export machinery (1, 27, 31). After nuclear export, vRNPs accumulate at the microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) (2, 24), where they associate with the cellular Rab11 GTPase, a major component of recycling endosomes (2, 10). vRNPs are later observed in punctate foci that colocalize with Rab11 in the peripheral cytoplasm and are transported to the cell surface in a manner dependent on Rab11 GTPase activity (2, 10); microtubules also may be involved in this process (2, 24). Near the plasma membrane, the vRNP foci coalesce and dissociate from Rab11 for their presumed incorporation into budding virions (10). While it is clear that cellular protein trafficking systems are necessary for influenza virus genome transport, additional unknown cellular factors likely contribute to this process.

Previously, the influenza virus NEP was shown to interact with the cellular human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Rev-binding protein (HRB) in a yeast two-hybrid system (31), but its role in the influenza virus life cycle was not examined. HRB contains a putative Arf GTPase-activating protein (GAP) domain at its N terminus (7, 33), regulates cellular endocytic processes (7, 8, 17, 33, 37), and may be a component of the nuclear pore complex (NPC) (12, 13, 29). We hypothesized that HRB contributes to influenza vRNP trafficking through effects on either nucleocytoplasmic transport or vesicular transport systems. By using a combination of small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated protein knockdown and coimmunofluorescence analyses, we found that HRB is critical for the efficient production of influenza virus progeny and is involved in mediating vRNP transport to the plasma membrane. Our results highlight the complex nature of influenza vRNP trafficking and suggest interplay between multiple endocytic compartments in vRNP delivery to cell surface sites of influenza virus formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and infections.

Transformed human embryonic kidney cells (293), human lung carcinoma cells (A549), Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (MDCK), human cervical adenocarcinoma cells (HeLa), baby hamster kidney cells (BHK), and Cercopithecus aethiops kidney fibroblast cells (CV-1) were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 in the following media: Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (293 and CV-1), DMEM containing 5% FBS (BHK), a 1:1 mixture of DMEM and Ham's F-12 nutrient mixture supplemented with 10% FBS (A549), minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 5% newborn calf serum (MDCK), or MEM supplemented with 10% FBS (HeLa). All media contained 50 units/ml of penicillin and 50 μg/ml of streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Influenza virus A/WSN/33 (H1N1) (WSN) was generated by using plasmid-based reverse genetics as described previously (28), and virus stock amplification and plaque assays were performed in MDCK cells. Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV; strain Indiana), vaccinia virus (VV; strain Ankara; a kind gift from Paul Ahlquist, University of Wisconsin—Madison), and adenovirus 5 (Ad5; strain McEwen; a kind gift from Paul Kinchington, University of Pittsburgh) stock virus amplifications and plaque assays were performed in BHK, CV-1, and A549 cells, respectively. For multicycle growth experiments after siRNA treatment, cells grown in 24-well plates were infected with 100 PFU of the indicated virus by direct inoculation of the culture medium. Supernatants were collected from influenza virus- and VSV-infected cells at 48 h and 24 h, respectively, and virus titrations were performed in MDCK or BHK cells. To harvest VV or Ad5, infected monolayers were scraped into the overlying media at 48 h, and the mixtures were subjected to three consecutive freeze-thaw cycles followed by centrifugation to clear insoluble debris. The resultant supernatants were subjected to virus titration in CV-1 or A549 cells for VV and Ad5, respectively. For similar experiments after plasmid transfection, cells in 12-well plates were inoculated with 200 PFU of WSN, and supernatants were harvested at 72 h for plaque assays in MDCK cells. For immunofluorescence and immunoblot experiments, cells were infected with WSN as described in the figure legends.

siRNAs, plasmids, and transfections.

siRNA transfections were performed as previously described (10). The final concentration of all siRNAs in the culture medium was 20 nM, and siRNA transfections were allowed to proceed for 48 h before subsequent plasmid transfections or virus infections. The following siRNAs were used: an extensively validated nontargeting siRNA (AllStars Neg; Qiagen, Valencia, CA; catalog no. 1027281), a previously described siRNA targeting influenza virus NP mRNA (NP-1496; synthesized by Qiagen) (14), a previously described siRNA targeting the human AGFG1 (HRB) gene (synthesized by Qiagen) (36, 45), and a validated mixture of siRNAs targeting essential host survival genes (Death Control; Qiagen catalog no. SI04381048).

To generate the HRB dominant negative mutant, total RNA was isolated from A549 cells using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen), and poly(A) RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase and an oligo(dT) primer (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturers' instructions. A segment of the AGFG1/HRB gene corresponding to amino acids 361 to 562 (ΔN360) was amplified from the resultant cDNA using gene-specific primers with 5′ XhoI and 3′ HindIII overhangs and was inserted in frame with enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the pEGFP-N1 vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA), producing the pΔN360-GFP plasmid. The plasmid expressing NEP fused to enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) was created by first PCR amplifying YFP (Clontech) with 5′ NotI and 3′ BglII overhangs and then inserting the product into the pCAGGS/multiple-cloning site (MCS) (18, 30) backbone. The WSN NEP open reading frame lacking the stop codon was then amplified by using 5′ EcoRI and 3′ NotI overhangs and inserted upstream and in frame with YFP in pCAGGS/MCS to produce pNEP-YFP. All plasmids were sequenced to confirm proper fragment insertion. Primer sequences are available upon request. For viral replication studies, 293 cells were transfected with plasmid DNAs by the calcium phosphate precipitation method using a calcium phosphate transfection kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. All other plasmid transfections were performed with the TransIT LT1 transfection reagent (Mirus Bio, Madison, WI).

Cell viability assay.

Cell viability was determined by assaying total intracellular ATP with the CellTiter-Glo kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's recommendations, with some modifications. Briefly, at the times indicated in Fig. 1, triplicate cultures of siRNA-treated 293 cells in 24-well dishes were lysed directly with 100 μl of Glo lysis buffer (Promega) for 15 min at room temperature. Subsequently, 50 μl of the resultant lysate was mixed with an equal volume of CellTiter-Glo reagent, and luminescence was read directly using a Tecan microplate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Switzerland).

Fig. 1.

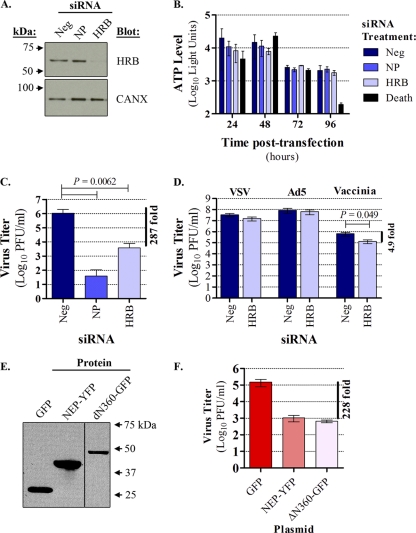

HRB perturbation interferes with influenza virus growth. (A) 293 cells were transfected with a validated, nontargeting commercial negative-control siRNA (AllStars Neg; referred to as “Neg” in the figure), siRNA targeting influenza virus NP mRNA (NP), or siRNA targeting HRB, and total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with mouse anti-HRB or rabbit anticalnexin (CANX; loading control) antibody. (B) Cell viability was measured using the CellTiter-Glo assay. 293 cells were transfected with siRNAs as described for panel A, except that a cell death-inducing siRNA mixture (Death) was also included. The data are represented as an average luciferase reading ± standard deviation (SD) for triplicate transfections. (C) Cells were transfected with siRNAs as described for panel A and were superinfected with influenza virus A/WSN/33 (WSN). At 48 h postinfection, supernatants were assayed for infectious virus by plaque assay in MDCK cells. The data shown are a compilation of three independent experiments, in which triplicate transfections were performed for each siRNA, and are represented as an average ± SD. A paired Student t test was used to compare replication in AllStars Neg siRNA-treated cells versus either NP or HRB siRNA treatments, and the P value is indicated above the graph. (D) 293 cells were transfected with AllStars Neg or HRB siRNA as described and infected with VSV, Ad5, or vaccinia virus. Infectious viruses from each condition were quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Paired Student t tests were performed to compare replication between the siRNA treatment conditions for each virus, and significant P values are indicated above the graph. Data are represented as means of triplicate transfections from two independent experiments ± standard errors of the means. (E) 293 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing GFP, NEP-YFP, or ΔN360-GFP, and expression levels were determined by immunoblot analysis of whole-cell lysates with anti-GFP antibodies at 48 h posttransfection. (F) At 48 h posttransfection, plasmid-transfected cells were superinfected with influenza virus WSN, and the level of infectious virus in supernatants was assayed by plaque assay in MDCK cells after 72 h. Data are represented as an average of triplicate infections performed for each transfection condition ± SD.

Minireplicon assay.

In vitro viral polymerase activity in siRNA or plasmid-transfected 293 cells was compared using a dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 48 h after siRNA transfection, triplicate cultures in 24-well plates were transfected with a plasmid expressing a firefly luciferase reporter under the control of the influenza virus WSN neuraminidase (NA) terminal genome sequences (pPolWSNNA F-Luc; 0.025 μg), together with the protein expression plasmids pCAGGS-PB2, pCAGGS-PB1, pCAGGS-PA, and pCAGGS-NP, which express the WSN polymerase complex proteins (0.25 μg each) (20, 28). Cells were also cotransfected with an internal control plasmid (0.025 μg) expressing Renilla luciferase regulated by the herpes simplex virus 1 thymidine kinase promoter (pGL.74; Promega), which exhibits basal transcriptional activation in mammalian cells. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured 48 h after plasmid transfection by using the Tecon microplate reader. The level of viral gene expression was determined after normalization to the level of cellular gene expression from the same sample (firefly luciferase light units/Renilla luciferase light units). This produced a ratio indicative of specific effects on viral polymerase activity; the average ratio for triplicate reads is reported.

Immunological assays.

Coimmunofluorescence and immunoblotting were performed as described previously (10). The following primary antibodies were used: monoclonal mouse anti-HRB antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; catalog no. sc-166651; used at a 1:100 dilution for immunofluorescence and a 1:500 dilution for immunoblotting), polyclonal rabbit anticalnexin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology catalog no. sc-11397; used at a 1:5,000 dilution for immunoblotting), mouse anti-GFP antibody (Clontech catalog no. 632375; used at a 1:20,000 dilution for immunoblotting), a previously described polyclonal rabbit antiserum against influenza vRNPs (R528; used at a 1:5,000 dilution for immunoblotting and a 1:2,500 dilution for immunofluorescence) (26), polyclonal rabbit antiactin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology catalog no. sc-10731; used at a 1:1,000 dilution for immunoblotting), a previously described rabbit antiserum against influenza virus NEP (R5023; used at a 1:200 dilution for immunofluorescence) (27), and a previously described monoclonal mouse antibody that recognizes influenza virus NP in the form of vRNP (MAb 3/1; used at a 1:1,000 dilution for immunofluorescence) (10). For secondary detection in immunoblot analysis, we used horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies, including goat anti-rabbit (Invitrogen; 1:2,000) and goat anti-mouse (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL; 1:2,000) antibodies. Proteins were detected with the Lumi-Light PLUS Western blotting substrate (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), Kodak Biomax XAR film, and a Konica Minolta SRX-101A X-ray film developer. Alexa Fluor (AF) 546-conjugated goat anti-mouse and AF 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies were used for secondary detection in immunofluorescence analyses (Invitrogen; 1:1,000). Where indicated in the figure legends, nuclei were stained with 0.4 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 (Invitrogen), or cells were treated with 20 ng/ml of leptomycin B (LMB) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or an equivalent volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). All fluorescence images were captured with a Zeiss LSM 510 META point-scan laser microscope system, as previously described (10). Images were exported as TIFF files and cropped using Adobe CS4 software but were otherwise unaltered.

RESULTS

HRB expression and function are essential for efficient influenza virus production.

HRB is a critical host factor in the HIV life cycle, and both siRNA-mediated knockdown of HRB expression and overexpression of a C-terminal fragment of the HRB protein (ΔN360) strongly impair HIV replication (45). To determine whether HRB is involved in the influenza virus life cycle, we examined the effect of reducing HRB expression or overexpressing the HRB ΔN360 fragment on influenza virus A/WSN/1933 (H1N1) (WSN) multicycle growth in 293 cells. HRB-specific siRNA treatment resulted in efficient protein knockdown without affecting a nontargeted cellular protein (calnexin [CANX]). Parallel transfections with nontargeting control siRNA (AllStars Neg) or siRNA targeting influenza virus NP mRNA did not result in knockdown of either HRB or CANX (Fig. 1 A). Further, cells treated with siRNA targeting HRB exhibited no major differences in cellular morphology (data not shown) or viability (Fig. 1B) compared to cells treated with nontargeting or NP-specific siRNA controls over a 96-h time course. This was in contrast to cells treated with death-inducing siRNAs, in which clear morphological changes consistent with cytotoxicity (data not shown) and a sharp reduction in viability at the 96-h time point (Fig. 1B) were observed. Because these data indicated that prolonged reduction in HRB expression was not detrimental to cell viability, we next tested the effects of the HRB siRNA on multicycle influenza virus growth. HRB siRNA induced a statistically significant (P = 0.0062), 287-fold reduction in the WSN titer relative to cells treated with the AllStars Neg control siRNA (Fig. 1C). This result was highly reproducible and observed in three independent experiments. Moreover, similar treatments did not cause a reduction in vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) or adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) replication and led to only a minor reduction in vaccinia virus replication (Fig. 1D). Therefore, while cells exhibiting significantly reduced HRB expression remained viable, they did not support the efficient production of progeny influenza viruses.

To corroborate these findings, we assessed multicycle growth in cells overexpressing the HRB ΔN360 protein fragment fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP), which was previously shown to act in a dominant negative manner (36). We used GFP alone as a negative control and influenza virus NEP fused to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) as a positive control, as our earlier work indicated that NEP overexpression impairs influenza virus replication (data not shown). We observed abundant levels of all plasmid-expressed proteins (Fig. 1E) and efficient transfection efficiency, with fluorescence in at least 75% of cells under all conditions by 48 h posttransfection (data not shown). Plasmid-transfected cells were infected with influenza virus WSN at this time, and at 72 h postinfection (hpi) cells expressing either NEP-YFP or ΔN360-GFP exhibited greater than 200-fold reductions in WSN titers relative to cells expressing only GFP (Fig. 1F). Taken together, our results show a critical dependence of influenza virus on HRB expression and function for the generation of infectious virus particles.

HRB knockdown does not impair influenza virus entry or viral gene expression.

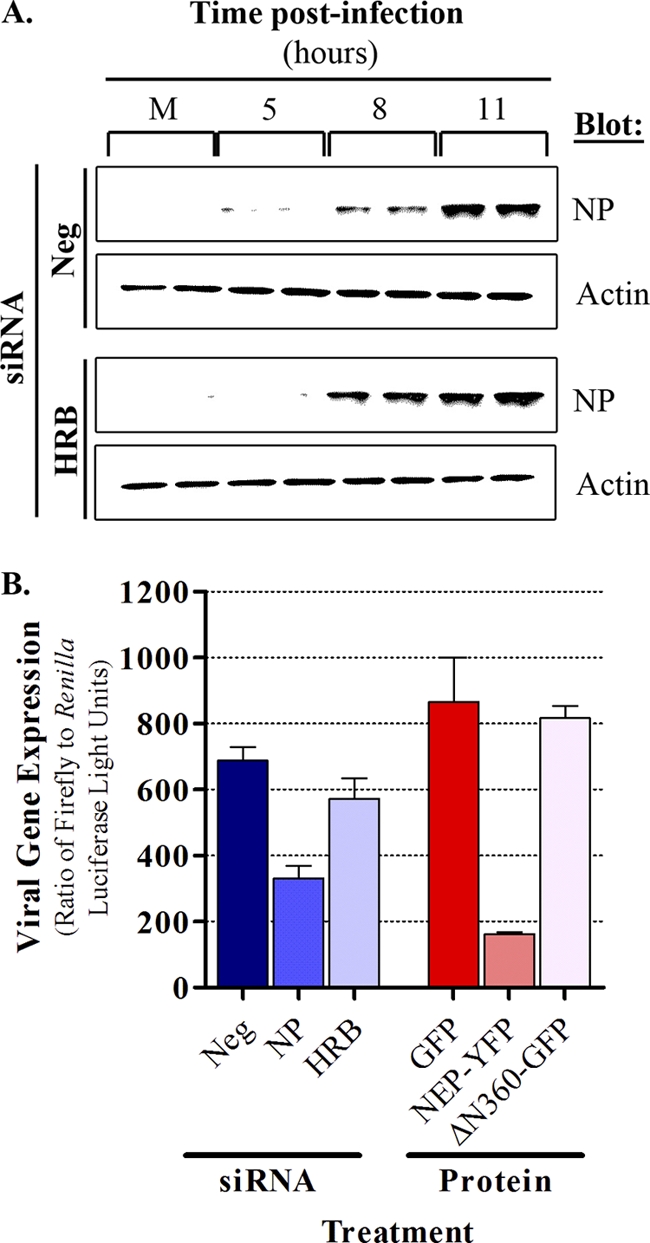

HRB interacts with adaptor-related protein complex 2 (AP2), which is involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis (37), and EPS15, a mediator of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) endocytosis (8), and is a regulator of clathrin-dependent endocytosis and endocytic sorting (7, 17, 33). Because influenza virus enters cells through a clathrin-dependent endocytosis mechanism (19) and virus entry depends on EGFR signaling (9), we wondered whether HRB knockdown might impair influenza virus entry. To test this, we assessed viral gene expression in WSN-infected cells after HRB or AllStars Neg control siRNA treatments. Cells treated with either siRNA and subjected to immunofluorescence staining with an NP-specific antibody exhibited comparable numbers of infected cells and similar fluorescence signals at 6 hpi (data not shown). Consistent with this finding, we saw no differences in influenza virus NP expression at 8 or 11 hpi (Fig. 2 A). These results suggest that HRB knockdown does not impair influenza virus entry or gene expression and that HRB functions at a later stage in the influenza virus life cycle.

Fig. 2.

HRB is not required for early events in the influenza virus life cycle. (A) siRNA-treated 293 cells were mock infected or infected with influenza virus WSN at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 3 PFU per cell, and total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with rabbit polyclonal antibody R528 (against influenza vRNP) or rabbit antiactin antibody (loading control) at different times after infection. siRNA treatments are indicated to the left, time points are shown at the top, and antibodies are to the right. Duplicate samples were prepared for each infection condition at each time point. (B) 293 cells were transfected with AllStars Neg (referred to as “Neg” in the figure), NP- or HRB-specific siRNAs, or plasmids expressing GFP, NEP-YFP, or ΔN360-GFP and were subsequently transfected with plasmids for the influenza virus WSN minireplicon assay. Viral gene expression levels were quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Data are represented as average ratios of firefly (viral)/Renilla (cellular) gene expression from triplicate transfections ± SD. M, Mock.

To further determine whether the disruption of HRB expression or function interferes with viral polymerase activity, we evaluated the effects of HRB siRNA treatment or overexpression of the ΔN360-GFP fragment in a minireplicon system, which provides an overall representation of the efficiency of vRNA, cRNA, and mRNA production. Cells were treated with siRNAs or plasmids expressing fluorescently tagged proteins, as described above, and were transfected with plasmids encoding the WSN polymerase complex proteins (PB2, PB1, PA, and NP) and a viral segment encoding a reporter firefly luciferase gene. Using this assay, we detected a minimal effect on viral reporter gene expression with HRB-specific siRNA and no effect with overexpression of ΔN360-GFP (Fig. 2B). This was in contrast with strong reductions in viral reporter gene expression observed with either NP-specific siRNA or NEP-YFP protein expression. Together, these data imply that HRB functions in the late stage of influenza virus infection and is not involved in regulating influenza virus entry, polymerase activity, or protein expression.

HRB and NEP partially codistribute in the cytoplasm during influenza virus infection.

Although HRB interacts with NEP in a yeast two-hybrid system, an association in the context of influenza virus infection has not been demonstrated. In uninfected cells, HRB exhibits juxtanuclear and punctate cytoplasmic localization, with occasional low-level accumulation in the nucleus (7, 33). This distribution pattern is distinct from the generally diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic profile of NEP (6, 11, 22, 40). To determine whether influenza virus infection induces changes in the HRB staining pattern, and to specifically address whether HRB and NEP associate in influenza virus-infected cells, we performed coimmunofluorescence analysis of WSN-infected A549 cells.

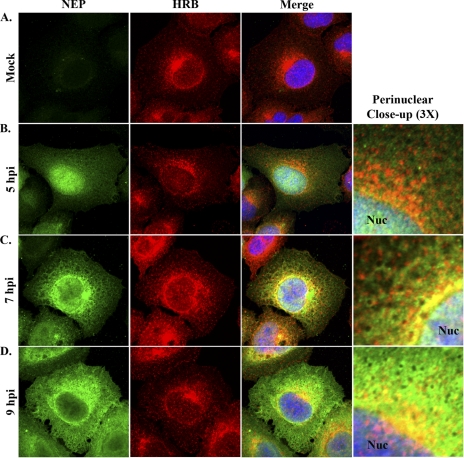

As in previous reports (7, 33), HRB in mock-infected cells was observed in peripheral cytoplasmic foci and accumulated in the perinuclear region, with occasional diffuse localization in the nucleus (Fig. 3 A). The overall HRB distribution pattern in WSN-infected cells was comparable to that of mock-infected cells at all time points (Fig. 3B to D). At 5 hpi, NEP exhibited prominent nuclear localization, with some diffuse staining in the cytoplasm and no colocalization with HRB (Fig. 3B). By 7 hpi, NEP began to accumulate in the perinuclear region of the cytoplasm and partially colocalized with HRB immediately adjacent to the nucleus (Fig. 3C). Of note, NEP also exhibited a mesh-like cytoplasmic staining pattern that was reminiscent of cellular cytoskeletal filaments (Fig. 3C); this localization pattern has not been described previously. By 9 hpi, NEP nuclear levels were consistently reduced, perinuclear levels were increased, and partial codistribution with HRB occurred near the nuclear membrane (Fig. 3D). Thus, our data reveal novel details about the localization of NEP in late-stage infected cells and suggest that NEP and HRB may interact in the perinuclear region.

Fig. 3.

HRB and NEP distribution in influenza virus-infected cells. A549 cells were mock infected (A) or infected with influenza virus WSN (MOI, 3) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 5 (B), 7 (C), and 9 (D) hpi. Permeabilized cells were stained with rabbit polyclonal antiserum against influenza virus NEP (R5023) and a mouse monoclonal antibody against HRB, combined with AF 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit and AF 546-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies and Hoechst 33258. Individual NEP (green) and HRB (red) staining patterns are shown for each time point, along with a merged panel including Hoechst nuclear staining. A 3× zoom highlighting the perinuclear region from the merged panels is shown in panels B to D. Nuc, nucleus.

HRB and vRNP colocalize at the MTOC in influenza virus-infected cells.

We previously demonstrated that cytoplasmic influenza vRNPs undergo multistage trafficking following nuclear export (10). Specifically, vRNPs initially accumulate at the MTOC, are cotransported with Rab11 through the cytoplasm in punctate foci, and accumulate at the plasma membrane in late-stage infected cells. Since the HRB localization pattern in infected cells mirrors that of vRNPs (Fig. 3), we hypothesized that HRB colocalizes with vRNPs to promote trafficking. To test this hypothesis, we examined the HRB spatiotemporal distribution pattern in relation to influenza vRNPs in WSN-infected A549 cells.

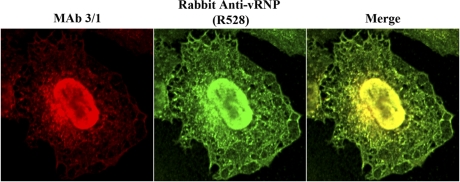

To detect vRNPs by immunofluorescence analysis in influenza virus-infected cells, we previously used a mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb 3/1) against influenza virus NP that exhibits a punctate cytoplasmic staining pattern and nearly completely colocalizes with cytoplasmic vRNA (10). Because we could not use MAb 3/1 with mouse anti-HRB (also a MAb) for indirect coimmunofluorescence analyses, we needed a compatible antibody that could identify vRNPs. The R528 rabbit polyclonal antiserum (used in Fig. 2A) was generated against purified influenza vRNPs and has been used to identify NP by immunofluorescence (26). Therefore, we tested whether R528 could detect influenza vRNPs by performing coimmunofluorescence with MAb 3/1. Both antibodies exhibited nearly identical staining patterns, recognizing NP in the nucleus and accumulating at the MTOC and in punctate foci in the peripheral cytoplasm (Fig. 4). Because MAb 3/1 is known to recognize vRNPs, we interpret these results to indicate that R528 also identifies trafficking vRNPs in the cytoplasm of influenza virus-infected cells.

Fig. 4.

Polyclonal rabbit anti-vRNP antibody (R528) identifies influenza vRNPs with specificities similar to that of monoclonal antibody 3/1. A549 cells were infected with WSN at an MOI of 3 PFU per cell and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 9 hpi. Permeabilized cells were stained with R528 and monoclonal antibody 3/1 (MAb 3/1), combined with AF 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (green) and AF 546-conjugated goat anti-mouse (red) antibodies. Individual and merged staining patterns are shown.

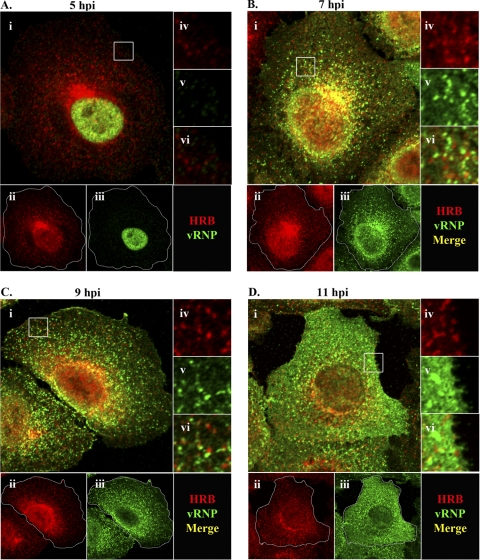

To assess the relationship between HRB and vRNP during infection, we next used R528 with mouse anti-HRB in coimmunofluorescence analysis. Similar to previous results (Fig. 3), HRB was primarily juxtanuclear at 5 and 7 hpi (Fig. 5 A and B). At 5 hpi, vRNPs were restricted to the nucleus and, as such, did not colocalize with the predominantly cytoplasmic HRB (Fig. 5A). Upon export from the nucleus at 7 hpi, vRNPs colocalized with HRB in the MTOC region (Fig. 5B, panel i). Some vRNPs could also be seen en route to the plasma membrane in close proximity to HRB (Fig. 5B, panel vi). At 9 hpi, vRNPs were distributed throughout the peripheral cytoplasm and near the plasma membrane and no longer prominently colocalized with HRB at the MTOC (Fig. 5C). By 11 hpi, vRNPs were observed in abundance near the plasma membrane, and although some HRB was also dispersed in this region, no specific colocalization with vRNP was observed (Fig. 5D, panels ii and vi). These data suggest a potential interaction between HRB and vRNP in the MTOC region and indicate that HRB is not a component of transport complexes that deliver vRNPs to the plasma membrane.

Fig. 5.

vRNP and HRB spatiotemporal dynamics in influenza virus-infected cells. A549 cells were infected with influenza virus WSN (MOI, 3) and harvested at 5 (A), 7 (B), 9 (C), or 11 (D) hpi. Cells were stained with rabbit anti-vRNP (R528) and mouse anti-HRB antibodies, followed by AF 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (green) and AF 546-conjugated goat anti-mouse (red) antibodies. Representative staining profiles are shown, with the specific time points indicated at the top. For each panel, panel i shows a merged image of HRB and vRNP, and individual staining profiles are shown in panels ii and iii, respectively. In panel ii, white traces indicate the plasma membrane boundaries. Individual and merged stainings are also shown for enlargements (3×) of boxed regions from panel i: iv, HRB; v, vRNP; and vi, Merge. A staining key is shown in the lower right corner of each panel.

HRB does not directly mediate vRNP nuclear export.

HRB associates with the cellular nuclear export factor CRM1 (29) and influenza virus NEP (31), both of which are required for influenza vRNP nuclear export (27, 31). Indeed, the NEP nuclear export signal is required for its association with HRB in the yeast two-hybrid assay (31). To clarify whether HRB participates in vRNP nuclear export by facilitating an interaction between vRNP-M1-NEP complexes and CRM1, we examined HRB, NEP, and vRNP distribution in cells treated with leptomycin B (LMB), a specific inhibitor of CRM1. We reasoned that if HRB is required to bridge the interaction between vRNP-M1-NEP and CRM1, then LMB treatment may result in HRB nuclear accumulation and colocalization with vRNP or NEP.

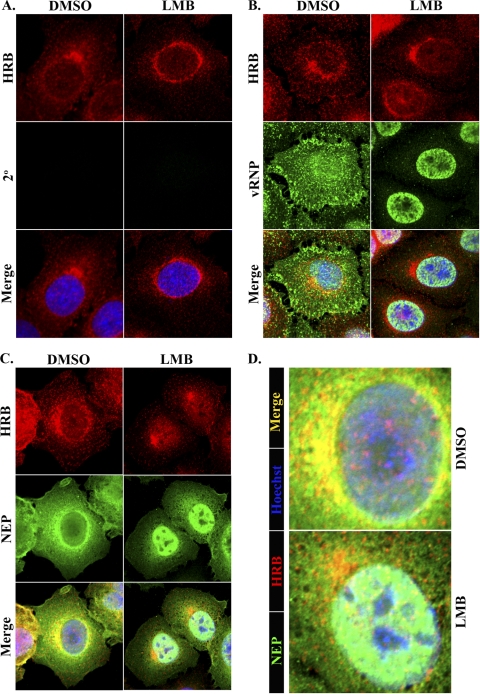

In mock-infected cells treated with LMB, we observed little to no accumulation of HRB in the nucleus, and the HRB distribution pattern was similar to that observed in DMSO-treated control cells, except that LMB treatment frequently resulted in more evenly distributed HRB around the periphery of the nucleus (Fig. 6 A). This indicates that HRB does not shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm in a CRM1-dependent manner. In influenza virus-infected cells, LMB treatment induced nearly complete vRNP nuclear retention and significantly increased the nuclear levels of NEP in most cells, consistent with previous findings (11, 22, 24, 40), but it did not cause HRB nuclear accumulation (Fig. 6B and C). As a consequence of vRNP nuclear accumulation and HRB cytoplasmic localization, vRNPs and HRB did not colocalize in the presence of LMB (Fig. 6B). LMB treatment also reduced colocalization between HRB and NEP in the perinuclear region, although some cytoplasmic forms of NEP persisted and low levels of colocalization could be observed at the MTOC (Fig. 6D). These data argue against a role for HRB in mediating interactions that promote influenza vRNP nuclear export and imply that the HRB promotes cytoplasmic, rather than nuclear, activities of influenza virus.

Fig. 6.

Leptomycin B (LMB) does not induce HRB nuclear accumulation. A549 cells were mock infected or infected with influenza virus WSN (MOI, 3), and at 4 hpi they were treated with LMB and further incubated with LMB for 5 h, followed by fixation in paraformaldehyde. (A) DMSO (control)- and LMB-treated mock-infected cells were stained with monoclonal mouse anti-HRB and AF 546-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies. Infected, DMSO- or LMB-treated cells were stained as described in the legend to Fig. 5 (B) or Fig. 3 (C), respectively. All cells were counterstained with Hoechst 33258. Individual HRB (red) and vRNP or NEP (green) panels are shown, along with a merged panel including Hoechst. (A to C) Drug treatments are shown at the top, and specific stains are indicated to the left. (D) Enlarged images of the merged panels in panel C, highlighting HRB and NEP distribution around the periphery of the nucleus. A color key is shown at the left, and drug treatments are shown at the right.

HRB knockdown provokes aberrant vRNP cytoplasmic trafficking in late-stage infection.

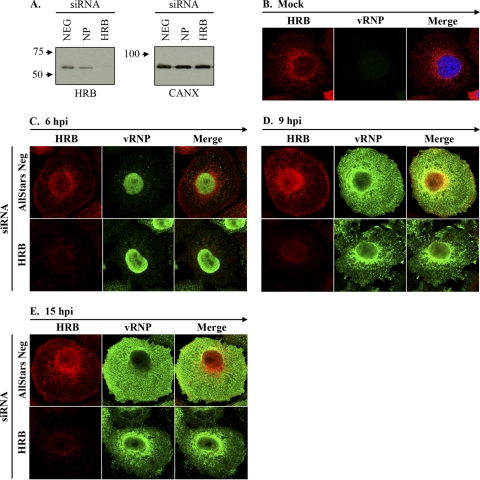

Our results excluded a role for HRB in influenza virus entry and polymerase activity and suggested that HRB may function in vRNP cytoplasmic transport but not vRNP nuclear export. To directly test this possibility, we assessed vRNP trafficking in HRB siRNA-treated cells by using coimmunofluorescence of HRB and vRNPs. 293 cells were not suitable for these studies because of their low cytoplasmic volume and weak adherence properties, and HRB siRNA treatments in A549 cells induced insufficient knockdown of HRB protein expression to impair influenza virus growth (data not shown). However, we observed efficient and specific reduction in HRB protein expression in HeLa cells (Fig. 7 A). Although influenza virus undergoes abortive infection in this cell type, the blocks occur principally at the levels of virus entry and viral budding (15). Therefore, we used HeLa cells as an alternative model system to examine influenza vRNP trafficking in the absence of abundant HRB protein expression. Of note, nontargeting siRNA-treated mock-infected HeLa cells exhibited HRB distribution similar to that observed in untreated A549 cells, with juxta- or perinuclear accumulation accompanied by punctate foci in the peripheral cytoplasm (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

HRB knockdown causes retention of vRNP in the perinuclear region. (A) Total cell lysates from AllStars Neg (referred to as “Neg” in the figure), NP, and HRB siRNA-treated HeLa cells at 48 h posttransfection were subjected to immunoblot analysis with mouse anti-HRB or rabbit anti-CANX (loading control). (B) Negative-control siRNA-treated HeLa cells were mock infected and subjected to staining with mouse anti-HRB and rabbit anti-vRNP (R528), followed by AF 546-conjugated goat anti-mouse and AF 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies. (C to E) HeLa cells treated with either negative control (AllStars Neg) or HRB siRNA were infected with influenza virus WSN (MOI, 5) and fixed at 6, 9, and 15 hpi. Cells were stained as described for panel B. Individual HRB (red) and vRNP (green) staining profiles, as well as merged images, are shown for each condition. siRNA treatments are shown to the left, and time points and stains are indicated at the top of each panel.

By 6 h after influenza virus infection, cells in both siRNA treatments exhibited prominent nuclear vRNP staining, despite appreciable differences in the level of HRB protein expression (Fig. 7C). This result confirms our previous finding that the lack of HRB does not impair influenza virus uptake or inhibit viral gene expression. At 9 hpi, HeLa cells treated with nontargeting siRNAs exhibited vRNPs in the perinuclear region and scattered throughout the cytoplasm, with some vRNP accumulation near the plasma membrane (Fig. 7D). At the same time point in HRB siRNA-treated cells, vRNPs accumulated in the perinuclear region, exhibiting tight association with the nuclear membrane, and were only minimally observed in the peripheral cytoplasm or at the plasma membrane. The effect of siRNA-mediated HRB knockdown was even more pronounced at 15 hpi (Fig. 7E). No obvious differences in vRNP nuclear export were observed for either siRNA transfection condition at any time point (Fig. 7C to E). These data suggest that cells with minimal HRB expression remain competent for vRNP nuclear export but are impaired in their ability to transport vRNP complexes from the perinuclear region to the plasma membrane.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have implicated the cellular CRM1 nuclear export and Rab11 recycling endosome pathways in influenza vRNP transport from the nucleus to plasma membrane sites of virion formation (2, 10, 11, 22, 27, 40). However, the detailed mechanisms of vRNP trafficking and the requirement for additional cellular cofactors remain to be illuminated. Here, we identified a second cellular endosomal factor integral to vRNP intracellular transport, the HRB Arf GAP. Our results clearly indicate that HRB expression and function are essential for efficient production of influenza virus progeny and implicate HRB in regulating vRNP trafficking from the perinuclear region to the plasma membrane. Since HRB has a role in both nucleocytoplasmic and endosomal trafficking, we suggest that HRB operates as a linker between these systems in influenza virus-infected cells to facilitate vRNP cell surface delivery and formation of infectious virus particles.

Upon its discovery, HRB was hypothesized to contribute to nucleocytoplasmic trafficking due to its ability to bind HIV Rev and facilitate Rev function (3, 8, 13), its interaction with the nuclear export receptor CRM1 (12, 29), and the presence of multiple nucleoporin-like phenylalanine-glycine (FG) repeats in its C terminus (13). Given these observations and the identification of HRB as an interaction partner for influenza virus NEP (31)—a known associate of CRM1 and an integral mediator of influenza vRNP nuclear export—we considered the potential for HRB to affect vRNP nuclear export to be important. However, several lines of evidence argue against this possibility. First, HRB exhibited exclusively cytoplasmic distribution in most cells (infected and mock infected) and did not consistently accumulate in the nucleus after influenza virus infection. Second, LMB treatment did not increase HRB nuclear accumulation in either mock-infected or infected cells, indicating that HRB does not traffic through the CRM1-dependent nuclear export pathway, which is required for influenza vRNP nuclear export (27). Most importantly, siRNA-mediated knockdown of HRB protein expression had no effect on vRNP nuclear export and instead induced accumulation of vRNPs in the perinuclear region. These observations strongly imply that HRB does not regulate vRNP nuclear export but rather participates in an early event in the vRNP cytoplasmic trafficking mechanism.

The tight association of vRNPs with the outer periphery of the nucleus in HRB siRNA-treated cells suggests that HRB may be involved in the release of vRNPs from CRM1-RanGTP nuclear export complexes. CRM1 associates with cargo in the nucleus in a RanGTP-dependent manner, and cargo-CRM1-RanGTP complexes are transported to the cytoplasm through the nuclear pore complex (NPC) (32). On the cytoplasmic face of the NPC, RANBP1 and RANBP2 cooperate to facilitate RanGTP hydrolysis to RanGDP, thereby inducing the disassociation of RanGDP and CRM1 and the release of cargo into the cytoplasm (16). Importantly, expression of a mutant Ran protein deficient in GTP hydrolysis results in CRM1 accumulation at the nuclear periphery (16). HRB preferentially accumulates at the periphery of the nucleus, contains a putative GTPase-activating protein (GAP) domain in its N terminus (33), and interacts with CRM1 (29). In influenza virus-infected cells, it is therefore conceivable for HRB to interact with CRM1 and RanGTP-associated vRNP nuclear export complexes, possibly assisted by interactions with NEP, to promote RanGTP hydrolysis following their transit across the NPC. A lack of HRB expression could then result in the accumulation of unhydrolyzed RanGTP at the nuclear periphery and the failure of CRM1 and vRNP to dissociate from the perinuclear region in late-stage infection. This concept is consistent with our observations for HRB-specific siRNA-treated, influenza virus-infected cells, where vRNPs were abundantly retained at the periphery of the nucleus. The HRB GAP domain is predicted to affect Arf GTPases, and to our knowledge no Arf GAP is known to influence RanGTP. However, other GAPs exhibit broad specificity against multiple small GTPases (4, 21, 39, 44). The verification of authentic HRB GAP activity and identification of HRB-targeted small GTPases will be necessary to clarify the potential role of HRB in modulating RanGTP at the nuclear membrane.

HRB may also facilitate other protein-protein interactions that promote vRNP recruitment to cytoplasmic transport complexes. In addition to its N-terminal putative Arf GAP domain, HRB contains multiple linear protein interaction motifs, including an established VAMP7 binding domain, a consensus clathrin binding motif and three consensus AP2 appendage binding motifs, multiple FG repeats typical of nucleoporins, and four C-terminal asparagine-proline-phenylalanine (NPF) motifs, which mediate interactions with proteins containing an EPS15 homology (EH) domain (8, 33, 36). Several EH domain-containing proteins (e.g., EHD1, EHD3, and EHD4) associate with endocytic recycling compartments containing Rab11 (25). Therefore, HRB could recruit vRNPs to Rab11 cytoplasmic transport complexes through coordinated interactions with NEP-associated vRNPs and an EH domain-containing protein. In support of this idea, we observed colocalization between HRB and both vRNPs and NEP at the MTOC, the site of initial vRNP-Rab11 association, immediately after vRNP nuclear export. Additional studies are required to define the specific components of influenza vRNP nuclear export and cytoplasmic trafficking complex intermediates.

In summary, we identified HRB as a novel host factor involved in an early step in influenza virus cytoplasmic genome transport. HRB was previously implicated in the HIV life cycle, facilitating the cytoplasmic trafficking of Rev-directed viral RNAs by promoting their release from the perinuclear region. Influenza virus and HIV genomes both use the CRM1 pathway for nuclear export (27, 29, 31); however, this is the first study to implicate a common cytoplasmic trafficking strategy for the genomes of these two viruses. Since influenza virus, unlike HIV, does not use the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) for new virion production (5, 34, 41), it will be interesting to delineate the point of divergence between the influenza virus and HIV genome trafficking mechanisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Susan Watson for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Public Health Service research grants, by a grant-in-aid for Specially Promoted Research from the Ministries of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, and by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Health and by ERATO (Japan Science and Technology Agency).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Akarsu H., et al. 2003. Crystal structure of the M1 protein-binding domain of the influenza A virus nuclear export protein (NEP/NS2). EMBO J. 22:4646–4655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amorim M. J., et al. 2011. A Rab11- and microtubule-dependent mechanism for cytoplasmic transport of influenza A virus vRNA. J. Virol. 85:4143–4156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bogerd H. P., Fridell R. A., Madore S., Cullen B. R. 1995. Identification of a novel cellular cofactor for the Rev/Rex class of retroviral regulatory proteins. Cell 82:485–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bowzard J. B., Cheng D., Peng J., Kahn R. A. 2007. ELMOD2 is an Arl2 GTPase-activating protein that also acts on Arfs. J. Biol. Chem. 282:17568–17580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruce E. A., et al. 2009. Budding of filamentous and non-filamentous influenza A virus occurs via a VPS4- and VPS28-independent pathway. Virology 390:268–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bui M., Wills E. G., Helenius A., Whittaker G. R. 2000. Role of the influenza virus M1 protein in nuclear export of viral ribonucleoproteins. J. Virol. 74:1781–1786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chaineau M., Danglot L., Proux-Gillardeaux V., Galli T. 2008. Role of HRB in clathrin-dependent endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 283:34365–34373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Doria M., et al. 1999. The eps15 homology (EH) domain-based interaction between eps15 and hrb connects the molecular machinery of endocytosis to that of nucleocytosolic transport. J. Cell Biol. 147:1379–1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eierhoff T., Hrincius E. R., Rescher U., Ludwig S., Ehrhardt C. 2010. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) promotes uptake of influenza A viruses (IAV) into host cells. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eisfeld A. J., Kawakami E., Watanabe T., Neumann G., Kawaoka Y. 2011. RAB11A is essential for influenza genome transport to the plasma membrane. J. Virol. 85:6117–6126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Elton D., et al. 2001. Interaction of the influenza virus nucleoprotein with the cellular CRM1-mediated nuclear export pathway. J. Virol. 75:408–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Floer M., Blobel G. 1999. Putative reaction intermediates in Crm1-mediated nuclear protein export. J. Biol. Chem. 274:16279–16286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fritz C. C., Zapp M. L., Green M. R. 1995. A human nucleoporin-like protein that specifically interacts with HIV Rev. Nature 376:530–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ge Q., et al. 2003. RNA interference of influenza virus production by directly targeting mRNA for degradation and indirectly inhibiting all viral RNA transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:2718–2723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gujuluva C. N., Kundu A., Murti K. G., Nayak D. P. 1994. Abortive replication of influenza virus A/WSN/33 in HeLa229 cells: defective viral entry and budding processes. Virology 204:491–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kehlenbach R. H., Dickmanns A., Kehlenbach A., Guan T., Gerace L. 1999. A role for RanBP1 in the release of CRM1 from the nuclear pore complex in a terminal step of nuclear export. J. Cell Biol. 145:645–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khwaja S. S., et al. 2010. HIV-1 Rev-binding protein accelerates cellular uptake of iron to drive Notch-induced T cell leukemogenesis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120:2537–2548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kobasa D., Rodgers M. E., Wells K., Kawaoka Y. 1997. Neuraminidase hemadsorption activity, conserved in avian influenza A viruses, does not influence viral replication in ducks. J. Virol. 71:6706–6713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lakadamyali M., Rust M. J., Zhuang X. 2004. Endocytosis of influenza viruses. Microbes Infect. 6:929–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li C., et al. 2010. Reassortment between avian H5N1 and human H3N2 influenza viruses creates hybrid viruses with substantial virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:4687–4692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu K., Li G. 1998. Catalytic domain of the p120 Ras GAP binds to RAb5 and stimulates its GTPase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 273:10087–10090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ma K., Roy A. M., Whittaker G. R. 2001. Nuclear export of influenza virus ribonucleoproteins: identification of an export intermediate at the nuclear periphery. Virology 282:215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martin K., Helenius A. 1991. Nuclear transport of influenza virus ribonucleoproteins: the viral matrix protein (M1) promotes export and inhibits import. Cell 67:117–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Momose F., Kikuchi Y., Komase K., Morikawa Y. 2007. Visualization of microtubule-mediated transport of influenza viral progeny ribonucleoprotein. Microbes Infect. 9:1422–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Naslavsky N., Caplan S. 2011. EHD proteins: key conductors of endocytic transport. Trends Cell Biol. 21:122–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Neumann G., Castrucci M. R., Kawaoka Y. 1997. Nuclear import and export of influenza virus nucleoprotein. J. Virol. 71:9690–9700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Neumann G., Hughes M. T., Kawaoka Y. 2000. Influenza A virus NS2 protein mediates vRNP nuclear export through NES-independent interaction with hCRM1. EMBO J. 19:6751–6758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Neumann G., et al. 1999. Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:9345–9350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Neville M., Stutz F., Lee L., Davis L. I., Rosbash M. 1997. The importin-beta family member Crm1p bridges the interaction between Rev and the nuclear pore complex during nuclear export. Curr. Biol. 7:767–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Niwa H., Yamamura K., Miyazaki J. 1991. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 108:193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. O'Neill R. E., Talon J., Palese P. 1998. The influenza virus NEP (NS2 protein) mediates the nuclear export of viral ribonucleoproteins. EMBO J. 17:288–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pemberton L. F., Paschal B. M. 2005. Mechanisms of receptor-mediated nuclear import and nuclear export. Traffic 6:187–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pryor P. R., et al. 2008. Molecular basis for the sorting of the SNARE VAMP7 into endocytic clathrin-coated vesicles by the ArfGAP Hrb. Cell 134:817–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rossman J. S., Jing X., Leser G. P., Lamb R. A. 2010. Influenza virus M2 protein mediates ESCRT-independent membrane scission. Cell 142:902–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sakaguchi A., Hirayama E., Hiraki A., Ishida Y., Kim J. 2003. Nuclear export of influenza viral ribonucleoprotein is temperature-dependently inhibited by dissociation of viral matrix protein. Virology 306:244–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sanchez-Velar N., Udofia E. B., Yu Z., Zapp M. L. 2004. hRIP, a cellular cofactor for Rev function, promotes release of HIV RNAs from the perinuclear region. Genes Dev. 18:23–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schmid E. M., et al. 2006. Role of the AP2 beta-appendage hub in recruiting partners for clathrin-coated vesicle assembly. PLoS Biol. 4:e262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shimizu T., Takizawa N., Watanabe K., Nagata K., Kobayashi N. 2011. Crucial role of the influenza virus NS2 (NEP) C-terminal domain in M1 binding and nuclear export of vRNP. FEBS Lett. 585:41–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tomoda T., Kim J. H., Zhan C., Hatten M. E. 2004. Role of Unc51.1 and its binding partners in CNS axon outgrowth. Genes Dev. 18:541–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Watanabe K., et al. 2001. Inhibition of nuclear export of ribonucleoprotein complexes of influenza virus by leptomycin B. Virus Res. 77:31–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Watanabe R., Lamb R. A. 2010. Influenza virus budding does not require a functional AAA+ ATPase, VPS4. Virus Res. 153:58–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. World Health Organization (WHO) 21 April 2011, posting date. Global alert and response: cumulative number of confirmed human cases of avian influenza A/(H5N1) reported to World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/country/cases_table_2011_04_21/en/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 43. World Health Organization (WHO) April 2009, posting date. Fact sheet no. 211. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs211/en [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xiao G. H., Shoarinejad F., Jin F., Golemis E. A., Yeung R. S. 1997. The tuberous sclerosis 2 gene product, tuberin, functions as a Rab5 GTPase activating protein (GAP) in modulating endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 272:6097–6100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yu Z., et al. 2005. The cellular HIV-1 Rev cofactor hRIP is required for viral replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:4027–4032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]