Abstract

Background

Although readiness to change is associated with mandated partner violence treatment compliance and subsequent violent behavior among male offenders (e.g., Eckhardt et al., 2004; Scott & Wolfe, 2003), our understanding of the factors associated with pretreatment change remains limited. Offender research indicates that individual and dyadic violent behavior are highly variable and that such variability may provide insight into levels of pretreatment change (Archer, 2002; Holtzworth-Monroe & Stuart, 1994).

Aims/Hypotheses

We sought to examine the associations between indicators of change and individual as well as dyadic violence frequency in a sample of male partner violence offenders.

Method

To determine whether severity and perceived concordance in the use of violence among male offenders and their female partners influenced readiness to change at pretreatment, 82 recently adjudicated male perpetrators of intimate partner violence were recruited into the current study and administered measures of readiness to change violent behavior (Revised Safe at Home Scale; Begun et al., 2008) as well as partner violence experiences (Revised Conflict Tactics Scale; Straus et al., 1996).

Results

Analyses revealed an interaction between offender-reported male and female violence in the prediction of pretreatment readiness to change such that greater male violence was associated with greater readiness to change among males who reported that their female partners perpetrated low, but not high, levels of violence. Consistently, greater female violence was associated with lower readiness to change only among the most violent male offenders.

Conclusions and Implications for Clinical Practice

Results provide support for the assertion that the most violent offenders may be the most resistant to partner violence intervention efforts, particularly when they perceive themselves to be victims as well. Enhanced motivational and couples programming may facilitate treatment engagement among the high-risk group of male offenders who report concordant relationship violence.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) results in devastating physical and psychological consequences for female victims and is defined as any threatening, harmful, or coercive acts of physical, sexual, or psychological aggression directed toward a current or past relationship partner (Saltzman et al., 2002). Rates of physical IPV are expectedly enhanced among partner violent offenders, with data suggesting that 20.9% of offenders perpetrate physical acts of IPV in the month prior to treatment engagement (Crane, Hawes, Mandel, & Easton, 2014), a statistic that is comparable to the entire past year prevalence of IPV observed among epidemiological samples (18.3%; Desmarais, Reeves, Nicholls, Telford, & Fiebert, 2012). IPV appears to be a particularly difficult set of behaviors to modify as male perpetrators respond poorly to treatment across various indicators of success, such as treatment enrollment and completion (e.g., Babcock, Green, & Robie, 2004). Research consistently finds that readiness to change is a broad indicator of treatment success among IPV males (Begun et al., 2008; Taft et al., 2004). Insight into the factors associated with readiness to change prior to treatment engagement, however, remains limited. The current study explores individual and dyadic IPV as risk factors for low pretreatment readiness to change among a sample of male IPV offenders.

The construct of readiness to change was derived from the transtheoretical model of intentional behavior change in which IPV offenders would be expected to transition through five normative stages (i.e., precontemplation. contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance) of change as they progress from violent to nonviolent cognition and behavior (Prochaska et al., 1992).1 Readiness to change has been described as an overall recognition of the risks and benefits associated with a target behavior in combination with one’s perceived capability of affecting change (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Therefore, readiness to change IPV is an associated but more global indicator of preparedness than the individual stages of change.

An association exists between IPV outcomes and both the stages of change as well as global readiness to change (e.g., Scott & Wolfe, 2003). Taft and colleagues (2004) found that greater readiness to change was associated with working alliance throughout treatment Eckhardt and colleagues (2004) found that pretreatment readiness to change was directly and positively associated with session attendance among IPV offenders. Another investigation, however, concluded that readiness to change was a non-significant predictor of IPV treatment compliance (Eckhardt et al., 2008). Nevertheless, an association between pretreatment indicators of change and treatment outcomes remains particularly concerning in light of the observation that most IPV offenders enter treatment at earlier stages of change (Eckhardt et al., 2008; Murphy & Eckhardt, 2005).

An examination of the inherent variability in patterns of individual and dyadic IPV may provide a degree of insight into predicting, identifying, and accommodating all levels of pretreatment readiness to change. Research supports a typological structure of perpetrators consistently depicting a continuum of severity in aggression among IPV samples in which greater violence is typically indicative of more pervasive, recalcitrant cognitions and behaviors (e.g., Bender & Roberts, 2007; Holtzworth-Monroe & Stuart, 1994). Thus, while male offenders who perpetrate more, relative to less, severe IPV may be expected to report lower levels of readiness to change, a study by Eckhardt and colleagues (2008) found that the least aggressive cluster of male offenders reported the lowest readiness to change scores. The researchers encouraged future investigations to establish factors that differentiate between offenders with low readiness to change that results from objectively limited use of aggression and low readiness to change that results from denial or minimization despite severe IPV. IPV is one of many behaviors that exists within the relationship context and, therefore, has been increasingly investigated within a relationship systems framework that involves examination of risk factors, proximal precipitants, violent actions, and consequences as exhibited by both members of the dyad (O’Farrell & Fals-Stewart, 2000; Testa & Derrick, 2014). Findings suggest that IPV-related behaviors exhibit a pattern of interdependence among relationship partners (for a review, see Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2010). Nationally representative surveys find that, when present, the most common dyadic configuration of IPV involves concordance in which both male and female partners perpetrate against one another (e.g., Straus, 2006).2 IPV concordant relationships evidence the greatest frequency and severity of violence with an increased risk for serious injury (Whitaker, Haileyses, Swahn, & Saltzman, 2007). Female perpetration raises secondary concerns because it is associated with lower rates of prosocial behavior change among treatment seeking IPV offenders (Crane et al., 2014).

It is not yet known if readiness to change is associated with the dyadic configuration of IPV. Female perpetration may provide a rationale for males in concordant violent relationships to inappropriately diffuse responsibility for violence (e.g., “She hit me too.”) and to deny (e.g., “We’re not violent, that’s just how we both communicate.”) or minimize (e.g., “It doesn’t hurt when she pushes me so it doesn’t hurt when I push her.”) the severity of their own behavior. These cognitive factors are indicative of treatment resistance and have been linked to the severity and chronicity of male perpetration (e.g., Scott & Straus, 2007). Further research is required to determine if female perpetration or patterns of dyadic IPV are associated with readiness to change among male offenders.

The Current Study

We evaluated the association between pretreatment readiness to change and the potential risk factors of individual and dyadic IPV severity, as indexed by violence frequency, using data collected from a sample of male IPV offenders. Based upon initial evidence offered by Eckhardt and colleagues (2008), we anticipated that male violence frequency would be positively associated with readiness to change. Limited by a dearth of previous research, we explored but advanced no a priori hypotheses pertaining to the effects of female violence frequency or the interaction of male and female violence frequency on readiness to change.

Method

Sample

As part of a larger treatment efficacy study, 90 justice-involved individuals were referred for study participation. Participants were deemed eligible for the current study if they were male, over 18 years of age, adjudicated on IPV-related charges within 2 weeks of recruitment, and willing to participate in the study. Eight offenders declined and 82 offenders completed all measures included in the current analyses. The sample is described in greater detail elsewhere (AUTHOR CITATION). Briefly, participants were, on average, 34.0 (SD = 11.8) years old and had been involved in their current relationship for 85.0 (SD = 91.6) months. Twenty-six (31.7%) participants were married at the time of the study and most participants were African American (52.4%) or Caucasian (46.3%).

Procedure

Personnel in an urban Department of Probation in a Midwestern state identified and referred males with IPV-related charges3 to two university-affiliated researchers following the standard battery of procedures performed during probation intake. Participants completed all study-related measures during a single 45–60 minute session in a private office at the probation department. The study was described as a university-based investigation and participants were informed that their responses would be neither provided to legal representatives nor reflected in their terms of probation, within the confines of confidentiality. Recruitment was completed within 6 months. All procedures used in the current study were approved the appropriate Institutional Review Board.

Participants completed informed consent as well as a battery of self-report measures administered in a structured interview format. In addition to sociodemographic items, readiness to change and IPV were assessed using standardized measures. The initial assessment procedure was intentionally designed to be brief, requiring only 15 minutes of the total session.

Measures

Readiness to change

The 35-item Revised Safe at Home Scale (SAH; Begun et al., 2008) is a measure of readiness to change violent behavior and has demonstrated strong psychometric properties (α = .69–.90) in IPV samples (Begun et al., 2008). Items assess general attitudes toward conflict and self-control without directly inquiring about IPV experiences. Participants respond on a scale that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The measure produces scores on 4 subscales that are reflective of the stages of change, including precontemplation (e.g., “It’s no big deal if I lose my temper from time to time”), contemplation (e.g., “I want help with my temper”), preparation/action (e.g., “I have a plan for what to do when I feel upset”), and maintenance (e.g., “I try talking things out with others so that I don’t get into conflicts anymore”). Subscale scores represent the average response of all included items. The subscale scores can be used to calculate a composite readiness to change score by subtracting the early stage score (i.e., precontemplation) from the sum of all late stage scores (i.e. contemplation, preparation/action, and maintenance) consistent with calculations from the original scale (Begun et al., 2003).

Partner violence

With good to excellent psychometric properties (α = .79–.95), the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996) is considered the gold standard assessment for IPV research and was used to assess the experience of past year relationship violence in the current study. Consistent with general administration procedures, participants were asked to rate the frequency of perpetration and victimization on a subset of six physical (i.e., punched or hit; twisted her arm or pulled her hair; pushed or shoved; choked; pushed against a wall; slapped), 2 injury (i.e., she had a sprain, bruise, or small cut; she needed to see a doctor after a fight with you), and 2 sexual (i.e., used threats to make her have sex; used force to make her have sex) IPV items over the past 12 months. Participant responses included 1 (never happened), 2 (happened once), 3 (happened 2–5 times), and 4 (happened 6 or more times). Male responses were recoded 0, 1, 3, and 6, respectively, to reflect frequency of occurrence and summed to calculate separate totals for male and female perpetration. Items demonstrated good internal consistency in the current sample (α = .84). Total perpetration and victimization scores were winsorized at two standard deviations from the mean, which affected the most extreme four perpetration scores and three victimization scores (Reifman and Keyton, 2010).

Data Analysis

To explore the associations of male and female perpetration with readiness to change, and to explore the effects of the interaction between male and female perpetration, we conducted a series of stepwise regression analyses in which male violence and male-reported female violence were entered as main effects in the first step and the interaction term was entered in the second step. Predictors were grand mean centered and regressed onto readiness to change and each stage of change score. Significant interactions were probed using simple slopes analyses at low (i.e., − 1 SD) and high (i.e., +1 SD) levels of violence (Aiken & West, 1991). Preliminary models included control variables on the first step, including offender the number of prior arrests, probation assessed risk level, paternity status, relationship duration, and relationship satisfaction. None of the control variable were significantly predictive of readiness to change and were dropped from the final models.

Results

Nearly three quarters (74.4%) of participants endorsed the use of violence against a partner in the past year with 7 (8.5%) reporting the use of force or coercion to engage in sexual activity. Similar figures emerged for male-reported female perpetration, with 61 (74.4%) participants reporting some form of female-to-male partner violence over the past year. Only 9 (11.0%) participants denied the experience of any violence in their relationship over the past year. Reports of male and female violence were associated (r=.26, p=.02). Participants reported moderate levels of readiness to change ranging from −0.5 to 7.7 (M=3.1, SD=1.7). An examination of individual subscales revealed that average responses on items depicting precontemplation (M=3.6, SD=0.6) were significantly higher than average responses depicting contemplation (M=2.6, SD=0.9), preparation/action (M=2.0, SD=0.5), and maintenance (M=2.1, SD=0.7).

Readiness to Change

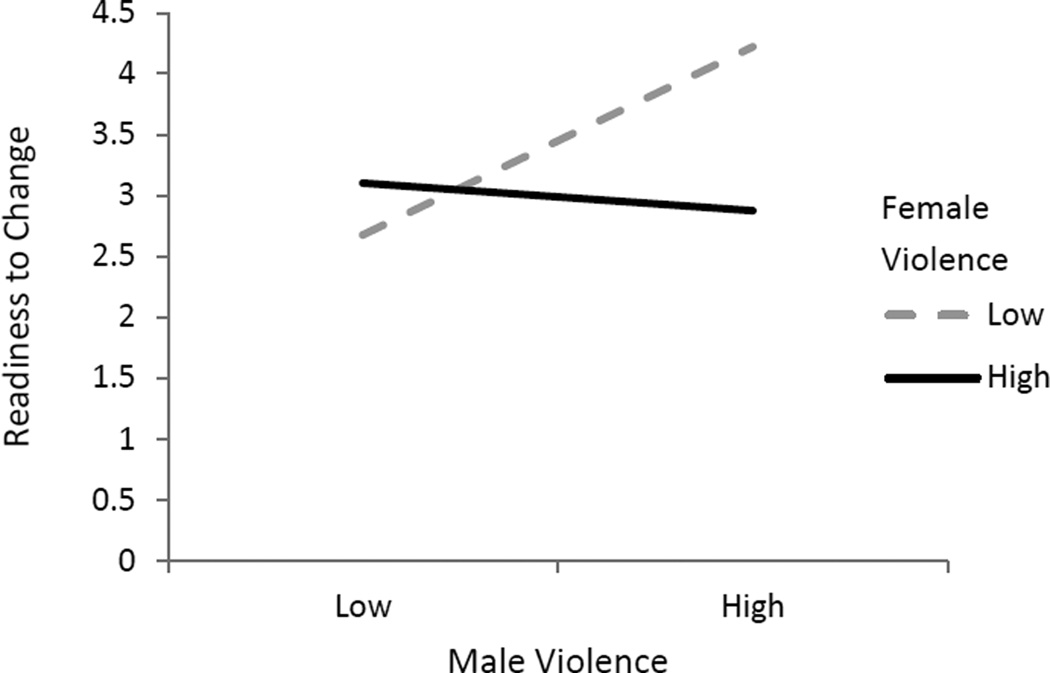

Results revealed no main effects of male (b=.03, SE=.05, p=.52) or female (b=−.02, SE=.02, p=.36) perpetrated violence on composite readiness to change scores among male offenders. These values were, however, qualified by a significant higher order interaction between male and female violence (b=−.01, SE=.01, p=.03). Simple slopes analyses (see Figure 1) revealed that readiness to change decreased as female violence increased only among high violence males (b=−.07, SE=.03, p=.03). Further analyses revealed that readiness to change increased with male violence only among males in relationships with lower female violence (b=.18, SE=.08, p=.03).

Figure 1.

The interaction of male and female perpetrated violence in the prediction of overall readiness to change scores.

Stages of Change

Precontemplation

Although the main effect of male violence was significant (b=−.04, SE=.02, p=.01), this effect was qualified by the significant male-female violence interaction (b=.004, SE=.002, p=.02). Examination of this interaction (see Figure 2) revealed that male violence was significantly, negatively associated with precontemplation at low (b=−.09, SE=.03, p=.001) but not high (b=−.04, SE=.04, p=.27) levels of female violence.

Figure 2.

The interaction of male and female perpetrated violence in the prediction of precontemplation and preparation / action stages of change scores.

Contemplation

A main effect of male violence perpetration emerged in the model predicting contemplation (b=−.06, SE=.02, p=.01), indicating that violent males scored lower on contemplation than less violent males. Female violence and the interaction term failed to reach significance.

Preparation/action

The main effect of male violence (b=.03, SE=.01, p=.04) was again qualified by a significant interaction term (b=−.004, SE=.001, p=.01). Examination of this interaction (See Figure 2) revealed that male violence was significantly, positively associated with preparation/action at low (b=.08, SE=.03, p=.001) but not high (b=.01, SE=.02, p=.60) levels of female violence. Similarly, female violence was significantly, negatively associated with preparation/action at high (b=−.03, SE=.01, p=.002) but not low (b=.01, SE=.01, p=.47) levels of male violence.

Maintenance

A marginal effect suggested that maintenance scores decreased with female violence (b=−.01, SE=.01, p=.09). No other effects in the model were significant.

Discussion

Pretreatment readiness to change and IPV data were collected from a sample of male offenders during their probation intake appointment. Results of this initial analysis into the association between readiness to change IPV behavior and individual as well as dyadic perpetration revealed a complex set of associations. We found that male-reported female IPV moderated the relationship between male IPV and change variables such that male violence was associated with adaptive indicators of change, including greater overall readiness to change, lower precontemplation scores, and high preparation/action scores, but only at low levels of male-reported female violence. Thus, acknowledgment of greater violence was indicative of greater readiness to change among men with relatively non-violent partners, an effect that failed to emerge among men with the most frequently violent partners. We also found that greater male-reported female violence was associated with lower readiness to change and lower preparation/action scores among the most violent male offenders, but not among males reporting low perpetration.

Taken together, results suggest that offenders engaged in relationships characterized by discordant male-only violence evidenced the most promising change profile while offenders engaged in concordant violent relationships may be particularly low in readiness to change, placing them at elevated risk (Scott & Wolfe, 2003). Data suggest that the recognition of one’s own high use of violence may prompt acceptance of the need for change (e.g., Zalmanowitz et al., 2013). These results are consistent with Eckhardt and colleagues (2008), who speculated that the least violent participants may not have viewed their common-couple violence as problematic or in need of change. As indicated by their static readiness to change scores across high and low levels of male violence, offenders with the most violent female partners in the current study may have used perceived female perpetration as justification for persisting with their own aggressive behaviors despite the negative consequences. Future research may evaluate alternative explanations for the observed relationship, such as a greater tendency to perceive victimization among males with low, relative to high, readiness to change.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although attempts were made to minimize participant motivation to positively present themselves, 21 offenders in the current sample denied the use of IPV. It remains possible that participants misrepresented their behavior, that they had not perpetrated violence over the past year, or that their violence was not captured by the set of behaviors included among the physical and sexual violence items from the CTS2. Our analyses did not include psychological IPV. Utilization of the full CTS2 may provide a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between readiness to change and violence type (e.g., physical, sexual, psychological) as well as severity (e.g., minor or severe). It should be noted, however, that the CTS2 has been criticized as a dated measure that may misrepresent female perpetration (for a review, see Hamby, 2014; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2010).

High violence offenders may have overestimated female violence in an effort to blame the female victim or minimize their own culpability. However, research shows that even among offender samples, partner ratings of male and female IPV perpetration demonstrate high reliability (Straus et al., 1996) and that male offenders even underestimate the extent of female perpetration relative to female partner reports (Wupperman et al., 2009).

Although we acknowledge gross variability in overall patterns of concordant or discordant dyadic violence, we were unable to explore the dyadic permutations of motivation (e.g., negative affect, control, self-defense, jealousy; Caldwell et al., 2009) for violence (Johnson & Ferraro, 2000). Given the observed similarities between male and female IPV perpetrators, future investigations may also consider evaluating the current findings among female offenders.

Implications

The current research detected variability in individual and dyadic patterns of violence among male IPV offenders, suggesting that dynamic interventions may be necessary to optimally address partner violence among this heterogeneous group of offenders. Among the most violent participants in the current sample, perceived female perpetration was a risk factor for low pretreatment readiness to change, suggesting that interventions which work toward reducing perceived and expected victimization may facilitate readiness to change among male offenders. Multiple studies have now found that the introduction of motivational interviewing, a set of techniques thought to exert influence over readiness to change, to IPV intervention programs has improved treatment compliance as well as behavioral indicators of programmatic success (e.g., Musser et al., 2008; Taft et al., 2001). The integration of motivational programming or modules that enlist the involvement of female partners, when the dyad is expected to remain intact, into individualized treatment plans may be particularly efficacious for partner violent offenders engaged in concordant violent relationships.

Acknowledgments

The current study was part of a larger investigation (Crane & Eckhardt, 2013). This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (K23 AA021768) and the Clifford B. Kinley Trust, Purdue University.

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Canandaigua Veterans Affairs Medical Center. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Footnotes

At the earliest stage of change, precontemplation, individuals are not currently acting toward or considering the option of behavior change. During the next stage of contemplation, individuals seriously consider the benefits of pursuing efforts to reduce or eliminate their use of IPV. Committing to and practical planning toward nonviolent behavior change occurs during the third stage of preparation. During the fourth stage, action, individuals enact their plan and actively work toward nonviolent behavior. The final stage, maintenance, involves habitualizing and propagating the new nonviolent behavior (Eckhardt, Babcock, & Homack, 2004).

Concordance is a descriptive term in the relationship literature that is used to denote similarity or dissimilarity between partners on a particular characteristic (Mudar, Leonard, & Soltysinski, 2001). Within the context of IPV, concordance refers to a dyadic configuration in which both partners perpetrate high or low levels relationship violence whereas discordant dyads are characterized by high levels of violence perpetrated by only one partner.

IPV-related charges involved any illegal acts of physical aggression committed against a current or past intimate partner and included assault, battery, strangulation, criminal confinement, harassment, as well as invasion of privacy. A technical violation (e.g., violation of a previous protection order or violation of the terms of probation following a previous IPV-related charge) alone was insufficient for inclusion in the current study.

Contributor Information

Cory A. Crane, Department of Psychological Sciences, Purdue University

Robert C. Schlauch, Department of Psychology, University of South Florida

Christopher I. Eckhardt, Department of Psychological Sciences, Purdue University

References

- Aiken L, West S. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander PC, Morris E. Stages of change in batterers and their response to treatment. Violence and Victims. 2008;23:476–492. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in physically aggressive acts between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2002;7:313–351. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Canady BE, Senior A, Eckhardt CI. Applying the transtheoretical model to female and male perpetrators of intimate partner violence: Gender differences in stages and processes of change. Violence and Victims. 2005;20:235–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Green CE, Robie C. Does batterers' treatment work? A meta-analytic review of domestic violence treatment. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;23:1023–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2002.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begun AL, Brondino MJ, Bolt D, Weinstein B, Strodthoff T, Shelley G. The revised Safe At Home Instrument for assessing readiness to change intimate partner violence. Violence and Victims. 2008;23:508–524. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begun AL, Murphy CM, Bolt D, Weinstein B, Strodthoff T, Short L, Shelley G. Characteristics of the Safe at Home instrument for assessing readiness to change intimate partner violence. Research on Social Work Practice. 2003;13:80–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bender K, Roberts AR. Battered women versus male batterer typologies: Same or different based on evidence-based studies? Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2007;12:519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JE, Swan SC, Allen CT, Sullivan TP, Snow DL. Why I hit him: Women's reasons for intimate partner violence. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2009;18:672–697. doi: 10.1080/10926770903231783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Bethea L, King MR, McKeown RE. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9:451–457. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Hawes SW, Mandel DL, Easton CJ. The occurrence of female-to-male partner violence among male intimate partner violence offenders mandated to treatment. Violence and Victims. 2014;29:940–951. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmarais SL, Reeves KA, Nicholls TL, Telford RP, Fiebert MS. Prevalence of physical violence in intimate relationships, Part 2: Rates of male and female perpetration. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:170–198. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton DG. The outcome of court-mandated treatment for wife assault: A quasiexperimental evaluation. Violence and Victims. 1986;1:163–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CI, Babcock J, Homack S. Partner assaultive men and the stages and processes of change. Journal of Family Violence. 2004;19:81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt C, Holtzworth-Munroe A, Norlander B, Sibley A, Cahill M. Readiness to change, partner violence subtypes, and treatment outcomes among men in treatment for partner assault. Violence and Victims. 2008;23:446–475. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.4.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S. Intimate partner and sexual violence research scientific progress, scientific challenges, and gender. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2014;15:149–158. doi: 10.1177/1524838014520723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Stuart GL. Typologies of male batterers: three subtypes and the differences among them. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:476–497. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Ferraro KJ. Research on domestic violence in the 1990s: Making distinctions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:948–963. [Google Scholar]

- Langan PA, Levin DJ. Recidivism of prisoners released in 1994. Federal Sentencing Reporter. 2002;15:58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J. Controversies involving gender and intimate partner violence in the United States. Sex Roles. 2010;62:179–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ménard KS, Anderson AL, Godboldt SM. Gender differences in intimate partner recidivism: A 5-year follow-up. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2008;36:61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mudar P, Leonard KE, Soltysinski K. Discrepant substance use and marital functioning in newlywed couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:130–134. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C, Eckhardt CI. Treating the abusive partner: An individualized, cognitive-behavioral approach. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Musser P, Semiatin J, Taft C, Murphy C. Motivational interviewing as a pre-group intervention for partner violent men. Violence and Victims. 2008;23:539–557. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.5.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Farrell TJ, Fals-Stewart W. Behavioral couples therapy for alcoholism and drug abuse. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;18:51–54. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00026-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifman A, Keyton K. Winsorize. In: Salkind NJ, editor. Encyclopedia of research design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2010. pp. 1636–1638. [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman LE, Fanslow JL, McMahon PM, Shelley GA. Intimate partner violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements: Version 1.0. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Scott K, Straus M. Denial, minimization, partner blaming, and intimate aggression in dating partners. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22:851–871. doi: 10.1177/0886260507301227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KS, Wolfe D. Readiness to change as a predictor of outcome in batterer treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:879–889. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Future research on gender symmetry in physical assaults on partners. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:1086–1097. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS-2) Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Murphy C, Elliott J, Morrel T. Attendance enhancing procedures in group counseling for domestic violence abusers. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2001;48:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Murphy CM, Musser PH, Remington NA. Personality, interpersonal, and motivational predictors of the working alliance in group cognitive-behavioral therapy for partner violent men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:349–354. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Derrick JL. A daily process examination of the temporal association between alcohol use and verbal and physical aggression in community couples. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:127–138. doi: 10.1037/a0032988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Haileyesus T, Swahn M, Saltzman LS. Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:941–947. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wupperman P, Amble P, Devine S, Zonana H, Fals-Stewart W, Easton CJ. Prevalence of violence and substance use among female partner of men in treatment of intimate-partner violence. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 2009;37:75–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalmonowitz SJ, Babins-Wagner R, Rodger S, Corbett BA, Leschied A. The association of readiness to change and motivational interviewing with treatment outcomes in males involved in domestic violence group therapy. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013;28:956–974. doi: 10.1177/0886260512459381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]