Abstract

Background

Heavy alcohol consumption causes alcoholic liver disease and is a causal factor of many types of liver injuries and concomitant diseases. It is a true systemic disease that may damage the digestive tract, the nervous system, the heart and vascular system, the bone and skeletal muscle system, and the endocrine and immune system, and can lead to cancer. Liver damage in turn, can present as multiple alcoholic liver diseases, including fatty liver, steatohepatitis, fibrosis, alcoholic cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma, with presence or absence of hepatitis B or C virus infection. There are three scarring types (fibrosis) that are most commonly found in alcoholic liver disease: centrilobular scarring, pericellular fibrosis, and periportal fibrosis. When liver fibrosis progresses, alcoholic cirrhosis occurs. Hepatocellular carcinoma occurs in 5% to 15% of people with alcoholic cirrhosis, but people in whom hepatocellular carcinoma has developed are often co‐infected with hepatitis B or C virus.

Abstinence from alcohol may help people with alcoholic disease in improving their prognosis of survival at any stage of their disease; however, the more advanced the stage, the higher the risk of complications, co‐morbidities, and mortality, and lesser the effect of abstinence. Being abstinent one month after diagnosis of early cirrhosis will improve the chance of a seven‐year life expectancy by 1.6 times. Liver transplantation is the only radical method that may change the prognosis of a person with alcoholic liver disease; however, besides the difficulties of finding a suitable liver transplant organ, there are many other factors that may influence a person's survival.

Ultrasound is an inexpensive method that has been used for years in clinical practice to diagnose alcoholic cirrhosis. Ultrasound parameters for assessing cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease encompass among others liver size, bluntness of the liver edge, coarseness of the liver parenchyma, nodularity of the liver surface, size of the lymph nodes around the hepatic artery, irregularity and narrowness of the inferior vena cava, portal vein velocity, and spleen size.

Diagnosis of cirrhosis by ultrasound, especially in people who are asymptomatic, may have its advantages for the prognosis, motivation, and treatment of these people to decrease their alcohol consumption or become abstinent.

Timely diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease is the cornerstone for evaluation of prognosis or choosing treatment strategies.

Objectives

To determine the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for detecting the presence or absence of cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease compared with liver biopsy as reference standard.

To determine the diagnostic accuracy of any of the ultrasonography tests, B‐mode or echo‐colour Doppler ultrasonography, used singly or combined, or plus ultrasonography signs, or a combination of these, for detecting hepatic cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease compared with liver biopsy as a reference standard, irrespective of sequence.

Search methods

We performed searches in The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register, The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies Register, The Cochrane Library (Wiley), MEDLINE (OvidSP), EMBASE (OvidSP), and the Science Citation Index Expanded to 8 January 2015. We applied no language limitations.

We screened study references of the retrieved studies to identify other potentially relevant studies for inclusion in the review and read abstract and poster publications.

Selection criteria

Three review authors independently identified studies for possible inclusion in the review. We excluded references not fulfilling the inclusion criteria of the review protocol. We sent e‐mails to study authors.

The included studies had to evaluate ultrasound in the diagnosis of hepatic cirrhosis using only liver biopsy as the reference standard.

The maximum time interval of investigation with liver biopsy and ultrasonography should not have exceeded six months. In addition, ultrasonography could have been performed before or after liver biopsy.

Data collection and analysis

We followed the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy.

Main results

The review included two studies that provided numerical data regarding alcoholic cirrhosis in 205 men and women with alcoholic liver disease. Although there were no applicability concerns in terms of participant selection, index text, and reference standard, we judged the two studies at high risk of bias. Participants in both studies had undergone both liver biopsy and ultrasonography investigations. The studies shared only a few comparable clinical signs and symptoms (index tests).

We decided to not perform a meta‐analysis due to the high risk of bias and the high degree of heterogeneity of the included studies.

Authors' conclusions

As the accuracy of ultrasonography in the two included studies was not informative enough, we could not recommend the use of ultrasonography as a diagnostic tool for liver cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease. In order to be able to answer the review questions, we need diagnostic ultrasonography prospective studies of adequate sample size, enrolling only participants with alcoholic liver disease.

The design and report of the studies should follow the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy. The sonographic features, with validated cut‐offs, which may help identify clinical signs used for diagnosis of fibrosis in alcoholic liver disease, should be carefully selected to achieve maximum diagnostic accuracy on ultrasonography.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Male; Liver Cirrhosis, Alcoholic; Liver Cirrhosis, Alcoholic/diagnostic imaging; Liver Diseases, Alcoholic; Liver Diseases, Alcoholic/complications; Prospective Studies; Ultrasonography

Plain language summary

Ultrasonography for diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease

Background Heavy alcohol consumption causes alcoholic liver disease and may lead to a number of other concomitant diseases. Alcohol may damage the function of body organs and can cause cancer. Liver damage due to excessive alcohol consumption is usually presented as fatty liver (build‐up of fats in the liver), steatohepatitis (inflammation of the liver with concurrent fat accumulation in the liver), fibrosis (fibrous degeneration), alcoholic cirrhosis (scarring of the liver), and hepatocellular carcinoma (most common type of liver cancer). When liver fibrosis progresses, alcoholic cirrhosis occurs.

Abstinence from alcohol may help people with alcoholic disease to improve their health at any stage of their disease; however, the more advanced the stage, the higher the risk of complications, co‐morbidities (presence of other diseases), and mortality (death), and lesser the effect of abstinence. Abstinence from alcohol one month after diagnosis of early cirrhosis will improve the chance of a seven‐year life expectancy by 1.6 times. Liver transplantation (replacement of a diseased liver) is the only radical method that may change the prognosis of a person with alcoholic liver disease; however, besides the difficulties of finding a suitable liver transplant organ, there are many other factors that may influence a person's survival after transplantation.

Ultrasound is an inexpensive method that has been used for years in clinical practice to diagnose alcoholic cirrhosis. Ultrasound parameters for assessing cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease encompass among others liver size, bluntness of the liver edge, coarseness of the liver parenchyma (part of the liver that filters blood to remove toxins), nodularity (unevenness) of the liver surface, size of the lymph nodes (small glands that filter lymph) around the hepatic artery (which supplies oxygenated blood to the liver), irregularity and narrowness of the inferior vena cava (which carries blood from the lower body to the heart), portal vein velocity, and spleen size.

Diagnosis of cirrhosis by ultrasound, especially in people who have no symptoms, may have its advantages for the prognosis, motivation, and treatment of these people to decrease their alcohol consumption or become abstinent.

Timely diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease is important for evaluation of prognosis or choosing treatment strategies.

Aim The primary review aim was to determine the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound for detecting the presence or absence of cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease compared with liver biopsy (where a small needle is inserted into the liver to collect a sample, which is then examined in a laboratory) as reference standard (i.e., the best available test). The secondary aim of the review was to determine the diagnostic accuracy of any of the ultrasound tests, B‐mode (a two‐dimensional ultrasound image display composed of bright dots representing the ultrasound echoes) or echo‐colour Doppler ultrasound (a colour ultrasound image showing blood flow through the liver), used singly or combined, or plus ultrasound signs, or a combination of these, for detecting hepatic cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease compared with liver biopsy as a reference standard.

Methods We searched the medical literature to retrieve studies for the review to 8 January 2015.

Results We identified two studies; one from 1985, performed in France, and the other from 2013, performed in South Korea. We could not analyse the data as the two studies with 205 participants in total were very different and they shared only a few clinical signs and symptoms for assessment of cirrhosis. We considered the studies at high risk of bias (the quality of the evidence was low).

Funding One of the two studies was sponsored by a grant from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea.

Conclusions The review authors cannot recommend the use of ultrasound as a diagnostic tool for liver cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease as the obtained study data were insufficient for analysis. Diagnostic ultrasound prospective studies with a large number of people and similar signs and features on ultrasound imaging are needed to establish how good the test is in detecting cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings'. 'Ultrasonography for diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease.

| Review question | What is the accuracy of ultrasonography for diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease? | |||

| Population | Men and women, over 16 years old, and diagnosed with alcoholic liver disease, following study authors' statements. | |||

| Settings | Participants could have been hospitalised or managed as outpatients. | |||

| Numbers of studies, participants, and participants with the target disease | 2 studies (reported in 3 publications); 205 participants contributed with data for the review analysis, out of which 142 participants with the target disease. | |||

| Study design | Prospective cohort study design with consecutive participants enrolled. | |||

| Index tests | Ultrasonography (in B‐mode and Doppler imaging) signs (singly or combined). | |||

| Reference standards | Liver biopsy. Laparoscopic liver biopsy and percutaneous liver biopsy. |

|||

| Study limitations | Studies at high risk of bias. No report of cut‐off values. | |||

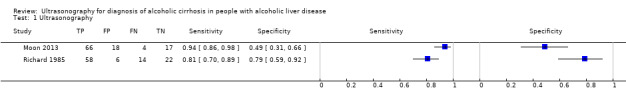

| Test | Studies | Participants | Sensitivity* (95% CI) | Specificity* (95% CI) |

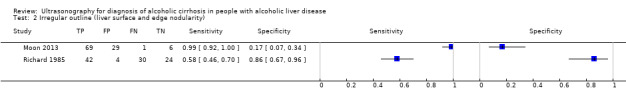

| *Irregular outline Liver surface and edge nodularity | 2 | 205 | 0.58 (0.46 to 0.70) 0.99 (0.92 to 1.00) |

0.86 (0.67 to 0.96) 0.17 (0.07 to 0.34) |

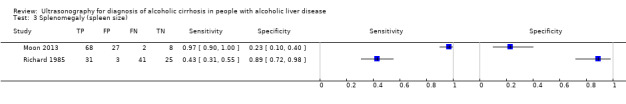

| *Splenomegaly Spleen size |

2 | 205 | 0.43 (0.31 to 0.55) 0.97 (0.90 to 1.00) |

0.89 (0.72 to 0.98) 0.23 (0.10 to 0.40) |

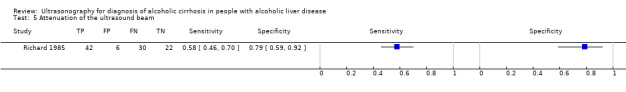

| Attenuation of the ultrasound beam | 1 | 100 | 0.58 (0.46 to 0.70) | 0.79 (0.59 to 0.92) |

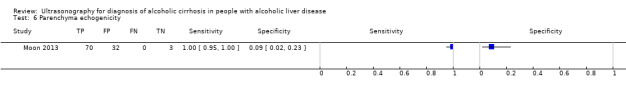

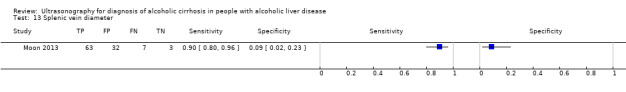

| Parenchyma echogenicity | 1 | 105 | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.00) | 0.09 (0.02 to 0.23) |

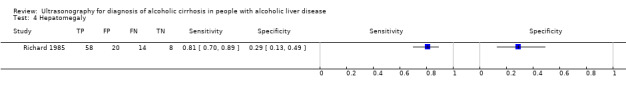

| Hepatomegaly | 1 | 100 | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.89) | 0.29 (0.13 to 0.49) |

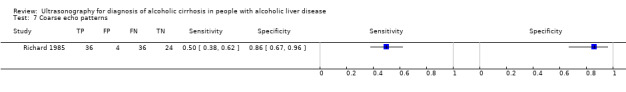

| Coarse echo patterns | 1 | 100 | 0.50 (0.38 to 0.62) | 0.86 (0.67 to 0.96) |

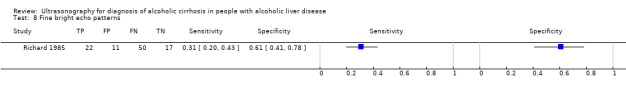

| Fine bright echo patterns | 1 | 100 | 0.31 (0.20 to 0.43) | 0.61 (0.41 to 0.78) |

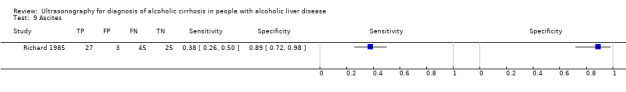

| Ascites | 1 | 100 | 0.38 (0.26 to 0.50) | 0.89 (0.72 to 0.98) |

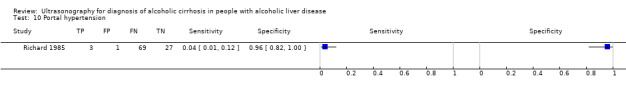

| Portal hypertension | 1 | 100 | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.12) | 0.96 (0.82 to 1.00) |

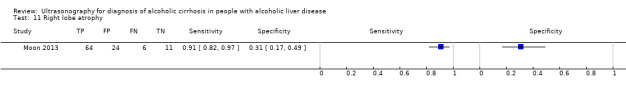

| Right lobe atrophy | 1 | 105 | 0.91 (0.82 to 0.97) | 0.31 (0.17 to 0.49) |

| Splenic vein diameter | 1 | 105 | 0.90 (0.80 to 0.96) | 0.09 (0.02 to 0.23) |

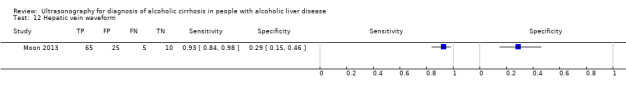

| Hepatic vein waveform | 1 | 105 | 0.93 (0.84 to 0.98) | 0.29 (0.15 to 0.46) |

| Ultrasound signs combined | 1 | 100 | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.89) | 0.79 (0.59 to 0.92) |

| Ultrasound sign score | 1 | 105 | 0.94 (0.86 to 0.98) | 0.49 (0.31 to 0.66) |

|

Conclusions: as the accuracy of the listed ultrasonography features in the 2 included studies, singly or as a score, was not sufficiently informative, we cannot recommend the use of ultrasonography as a diagnostic tool for liver cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease. CI: confidence interval. | ||||

*Similar tests evaluated by the two studies are presented in one row in the table with their individual sensitivities and specificities. As we could not perform a meta‐analysis due to the risk of bias and heterogeneity, there were no pooled results.

As one of the studies used combined ultrasound signs (hepatomegaly, irregular outline, coarse echo patterns, fine bright echo patterns, attenuation of the ultrasound beam, splenomegaly, ascites, portal hypertension) (Richard 1985), and the other study used them as a score (liver surface and edge nodularity, parenchyma echogenicity, spleen size, right lobe atrophy, splenic vein diameter, hepatic vein waveform) (Moon 2013), we presented their individual sensitivities and specificities.

Background

Alcohol consumption is a worldwide problem. Every year approximately 2.5 million people die of it; 320,000 of them are young people between 15 and 29 years of age. Based on estimates for 2004, alcohol was responsible for almost 4% of all deaths in the world (WHO 2010).

Heavy alcohol consumption causes alcoholic liver disease and is a causal factor of many types of liver injuries and concomitant diseases. It is a true systemic disease that may damage the digestive tract, the nervous system, the heart and vascular system, the bone and skeletal muscle system, and the endocrine and immune system, and can lead to cancer (WHO 2010; Rocco 2014).

Liver damage in turn, can present as multiple alcoholic liver diseases, including fatty liver, steatohepatitis, fibrosis, alcoholic cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma, with presence or absence of hepatitis B or C virus infection (Brunt 1974; Bruha 2012; Testino 2014). There are three scarring types (fibrosis) that are most commonly found in alcoholic liver disease: centrilobular scarring, pericellular fibrosis, and periportal fibrosis. When liver fibrosis progresses, alcoholic cirrhosis occurs. Hepatocellular carcinoma occurs in 5% to 15% of people with alcoholic cirrhosis, but people in whom hepatocellular carcinoma has developed are often co‐infected with hepatitis B or C virus (MacSween 1986; Jaurigue 2014).

Abstinence from alcohol may help people with alcoholic disease in improving their prognosis of survival at any stage of their disease; however, the more advanced the stage, the higher the risk of complications, co‐morbidities, and mortality, and lesser the effect of abstinence (Borowsky 1981). Being abstinent one month after diagnosis of early cirrhosis will improve the chance of a seven‐year life expectancy by 1.6 times (Verrill 2009). Liver transplantation is the only radical method that may change the prognosis of a person with alcoholic liver disease; however, besides the difficulties of finding a suitable liver transplant organ, there are many other factors that may influence a person's survival (Iruzubieta 2013; Singal 2013).

Cochrane systematic reviews of randomised clinical trials of pharmacological interventions used for reducing alcohol consumption such as acamprosate, benzodiazepines, naltrexone, gamma‐hydroxybutyrate, baclofen (derivative of gamma‐aminobutyric acid), and anticonvulsants versus placebo or another drug in alcohol‐dependent people have studied the benefits and harms of these interventions for alcohol reduction or withdrawal (Amato 2010; Leone 2010; Minozzi 2010; Rösner 2010a; Rösner 2010b; Liu 2013; Pani 2014). However, the conclusions, despite showing some potential tendency of alcohol reduction or promotion of abstinence, lack the desired robustness of evidence as the performed randomised clinical trials for alcohol withdrawal with the suggested drug interventions may fail in quality, be of insufficient sample size, be too heterogeneous, or lack sufficient evidence for benefits. Without diminishing nutritional and supportive management of people with alcoholic liver disease, complete abstinence from alcohol seems still to be the only recommended form of hepatoprotection.

Ultrasound is an inexpensive method that has been used for years in clinical practice to diagnose alcoholic cirrhosis (Rockey 2009; O'Shea 2010). Ultrasound parameters for assessing cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease encompass among others liver size, bluntness of the liver edge, coarseness of the liver parenchyma, nodularity of the liver surface, size of the lymph nodes around the hepatic artery, irregularity and narrowness of the inferior vena cava, portal vein velocity, and spleen size (Nishiura 2005).

In a series of 1604 people with alcoholic liver disease diagnosed on liver biopsy or clinically confirmed diagnosis, 608 (38%) people had developed alcoholic cirrhosis (Naveau 1997). Diagnosis of cirrhosis by ultrasound, especially in people who are asymptomatic, may have its advantages for the prognosis, motivation, and treatment of these people to decrease their alcohol consumption or become abstinent (O'Shea 2010).

Timely diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease is the cornerstone for evaluation of prognosis or choosing treatment strategies in these people.

Target condition being diagnosed

Cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease

People with alcoholic liver disease are at risk of developing liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. This risk is considered higher in people who are binge drinkers, people with increased serum alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels, and in people with severe alcohol hepatitis on liver biopsy (Bouchier 1992). Cirrhosis may have symptoms and signs of liver disease, and cirrhosis may vary from one person to another. In general, people with alcoholic liver disease see a doctor when symptoms and signs from the complications of cirrhosis have already developed (O'Shea 2010). Physicians should attempt to motivate people to stop drinking. Indirect evidence of alcohol abuse can be collected through questionnaires about drinking habits, through information received from family members, and through running laboratory tests (O'Shea 2010).

Hepatic fibrosis may develop as a result of weekly alcohol consumption of seven to 13 beverages for women (one beverage = 12 g of alcohol) and 14 to 27 beverages for men over the course of five or more years (Savolainen 1993; Becker 1996). The risk ratio of progression of fibrosis to cirrhosis increases significantly with a daily consumption of 20 to 40 g of ethanol in women and more than 80 g of ethanol in men (Sherlock 1997; O'Shea 2010).

The liver is the main site of alcohol metabolism acting through two hepatic enzymes, alcohol dehydrogenase and cytochrome P‐450 (CYP) 2E1. Increased alcohol intake disrupts metabolic liver function, and, as a result, alcoholic liver disease develops (Stewart 2001).

METAVIR is the most widely used scoring system for interpretation of liver biopsy results based on the stage of fibrosis where F0 indicates no fibrosis, F1 indicates portal fibrous expansion (mild fibrosis), F2 indicates thin fibrous septa emanating from portal triads (significant fibrosis), F3 indicates fibrous septa bridging portal triads and central veins (severe fibrosis), and F4 indicates cirrhosis (Table 2).

1. Semi‐quantitative histopathological scoring systems for progression of fibrosis to cirrhosis. Conversion grid for the stages of hepatic fibrosis*.

| Stage of fibrosis | ||||||

| METAVIR | Knodell | Ishak | Kleiner | Desmet | Brunt | Batts‐Ludvig |

| F0 | F0 | F0 | F0 | F0 | F0 | F0 |

| F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 |

| F1 | F1 | F2 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 |

| F2 | F3 | F3 | F2 | F2 | F2 | F2 |

| F3 | F3 | F4 | F2 | F3 | F3 | F3 |

| F4** | F4 | F5 | F3 | F4 | F4 | F4 |

| F4** | F4 | F6 | F4 | F4 | F4 | F4 |

METAVIR, Knodell, Ishak, Kleiner, Desmet, Brunt, and Batts‐Ludvig scoring systems are used to classify fibrosis (and steatosis) due to alcoholic liver disease. For references, please see review text. *Adapted from Goodman 2007.

**As the focus of our review is on alcoholic cirrhosis alone, for discrepancies in classification of cirrhosis, we have used the last two rows of the table (shaded).

F: stage of hepatic fibrosis. F0: no fibrosis; F1: portal fibrous expansion; F2: thin fibrous septa emanating from portal triads; F3: fibrous septa bridging portal triads and central veins; F4: cirrhosis. Clinically significant fibrosis is generally defined as F2 or greater on the METAVIR scale from F0 to F4 with F4 being cirrhosis. Clinically significant fibrosis is defined as Ishak fibrosis stage F3 to F6, and cirrhosis defined as Ishak fibrosis F5 or F6.

Michalak 2003 validated the reproducibility of the METAVIR score using a slightly modified METAVIR score, that is, the portal tract/septal fibrosis score, to investigate the amount of fibrosis and study the influence of centrilobular fibrosis and portal tract/septal fibrosis in alcoholic chronic liver disease. The amount of portal tract/septal fibrosis in people with alcoholic chronic disease was greater than the amount of centrilobular fibrosis in the control group of people with viral chronic hepatitis disease, which suggested that portal tract/septal fibrosis was more frequent in alcoholic chronic liver disease than in viral chronic hepatitis. However, centrilobular fibrosis forms with the advance of fibrosis in cirrhosis. The prognostic value of the METAVIR fibrosis score in alcoholic liver disease still needs to be established (Michalak 2003).

In Table 2, we have included other widely used systems for classification of fibrosis in people with alcoholic liver disease (Knodell 1981; Desmet 1994; Ishak 1995; Brunt 1999; Kleiner 2005; Haque 2010). However, as the focus of our review is on alcoholic cirrhosis alone, for discrepancies in classification of cirrhosis, we refer the readers to the last two rows of the table (shaded).

Index test(s)

Ultrasonography is used in clinical practice for diagnosis of cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease as it allows investigation of the hepatic tissue through the generation of ultrasonic waves. B‐mode and Echo‐colour Doppler ultrasonography seem to be the most often used methods for diagnosis of cirrhosis. There are some other new ultrasound‐based methods, such as ultrasound‐based elastography, acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI), and supersonic shear imaging.

Ultrasonic patterns obtained at ultrasonography investigation in B‐mode are usually classified as positive or negative considering signs used in different combinations and defined as indices, for example, parenchymal (liver surface, volume, edge, and texture), extrahepatic (spleen volume, presence of ascites), and vascular (diameter of portal and spleen veins). Hepatic fibrosis produces abnormal echo patterns on ultrasound scanning. Much higher attenuation is observed at examination of the liver of people with steatosis compared to the liver of people with hepatic fibrosis (Bamber 1979; Saverymuttu 1986).

Vascular (Doppler) indices, such as Doppler perfusion index, hepatic transit time, portal vein congestive index, and various ratios analysing different blood vessels, are used indirectly for detection of portal hypertension and cirrhosis (Ersoz 1999; Hizli 2010; Ivashkin 2011a).

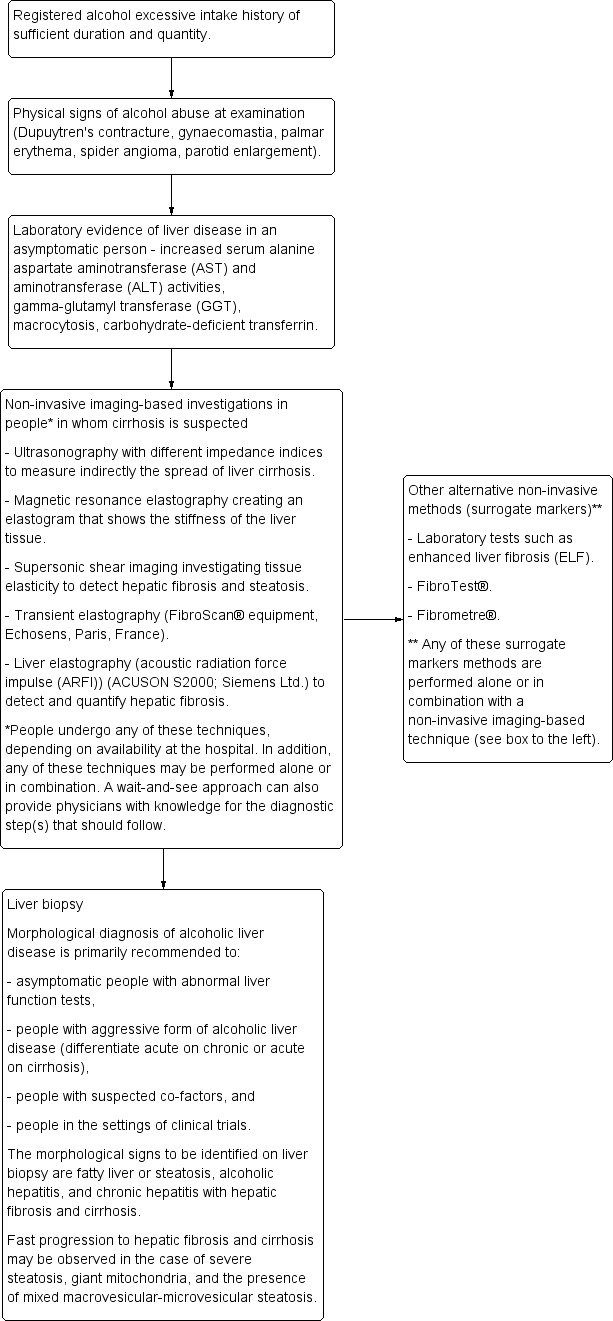

Clinical pathway

Figure 1 presents the clinical pathway in the diagnosis of alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

1.

Clinical pathway in the diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease.

Alternative test(s)

Different methods to assess liver fibrosis have been developed since 1990. Most of them are aimed at quantifying the elasticity or viscoelasticity of the liver tissue. There are two common elements in every elasticity imaging method: a force or stress is applied on the liver tissue and the obtained mechanical response is measured.

ARFI (ACUSON S2000; Siemens Ltd.) is a non‐invasive imaging technique that can detect and quantify hepatic fibrosis. The ARFI technology is also called liver ultrasound elastography (Iyo 2009). ARFI imaging is faster than conventional methods as ARFI uses higher frequencies that are comparable to those used in colour Doppler imaging. The images have greater contrast and the boundary of the focal lesions are better defined compared with conventional ultrasonography imagining techniques (Iyo 2009).

Supersonic shear imaging investigates tissue elasticity to detect hepatic fibrosis and steatosis. It is based on velocity estimation of a shear wave, generated by a radiation force (Bercoff 2004).

Magnetic resonance elastography combines magnetic resonance imaging with sound waves to create a visual map (elastogram) showing the stiffness of the liver tissue. It is used primarily to detect hardening of the liver caused by different types of liver diseases, including those of alcoholic aetiology (Yin 2007).

Transient elastography is another non‐invasive method for assessment of hepatic fibrosis (Gómez‐Domínguez 2006; Pavlov 2015), which measures hepatic fibrosis through the stiffness of the hepatic parenchyma. Transient elastography measures the speed of propagation of the elastic wave through the hepatic parenchyma: the stiffer the tissue, the faster the shear wave propagates the obtained hepatic stiffness, expressed as a median value in kiloPascals (kPa).

Other alternative non‐invasive tests (apart from venepuncture) are laboratory tests such as aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio, platelet count, prothrombin index, hyaluronic acid, and enhanced liver fibrosis score (Crespo 2012; Liu 2012). All of these tests are used as surrogate markers for staging of hepatic fibrosis. In addition, different combinations of biochemical tests such as FibroTest® and Fibrometre® are used for diagnosis and staging of hepatic fibrosis in people with alcoholic liver disease (Morra 2007; Poynard 2007; Poynard 2008; Angulo 2009).

Rationale

Liver biopsy has so far been considered the standard method for detection of hepatic fibrosis and its staging, using different semi‐quantitative morphological scores on liver tissue samples with a size of no more than 1 to 2 cm3 (Table 2). One advantage of liver biopsy is that it may give diagnostic information for concurrent liver diseases (Poulsen 1979; Ismail 2011). However, there are a number of disadvantages with liver biopsy. It is invasive, and it may have potential risks to the person such as punctures of abdominal organs and haemorrhage. Liver biopsy can be painful, time‐consuming, and stressful for the person (Grant 1999; O'Shea 2010; Ivashkin 2011b). The risk of haemorrhage and death after a percutaneous liver biopsy is especially higher in people with a platelet count of 60,000 per mm3 or less (Seeff 2010). Transjugular liver biopsy seems a safer alternative for people with low platelet counts or clotting abnormalities. The small size of the tissue samples, either obtained transcutaneously or via the transjugular route, may also lead to sampling errors.

The technical possibilities of the ultrasonography equipment and the individual experience of the investigator performing the ultrasonography are the main factors influencing the precision of the ultrasound examination. Consensus on using ultrasonography as a non‐invasive method for diagnosis of cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease seems not to have been established, despite being widely used instead of, or together with, other non‐invasive techniques (Shiha 2009). When a person presents with clinical symptoms (e.g., ascites, encephalopathy, oesophageal bleeding) of cirrhosis, neither liver biopsy nor ultrasonography are needed. However, in case of insufficient or unclear expression of clinical signs, a wait‐and‐see approach, ultrasonography, or other alternative non‐invasive tests may be considered before arranging a liver biopsy investigation (Figure 1). As cirrhosis is a main prognostic variable with impact on survival of people with alcoholic liver disease, it is important to detect cirrhosis, assess the risk of complications, and encourage abstinence of drinking alcohol (Leong 2012; Singal 2013; Testino 2014).

This review aimed to meta‐analyse data from studies on the diagnosis of cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease and to assess the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography in detecting the presence of cirrhosis compared with liver biopsy as reference standard, following Cochrane methodology (SRDTA Handbook).

We did not identify any meta‐analysis or systematic review on the use of ultrasonography for defining the presence of cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease. A Cochrane systematic diagnostic test accuracy review on ultrasonography in detecting cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease compared with liver biopsy does not exist either. Therefore, we conducted this review.

Objectives

To determine the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for detecting the presence or absence of cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease compared with liver biopsy as reference standard.

Secondary objectives

To determine the diagnostic accuracy of any of the ultrasonography tests, B‐mode or Echo‐colour Doppler ultrasonography, used singly or combined, or plus ultrasonography signs, or a combination of these, for detecting hepatic cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease compared with liver biopsy as a reference standard, irrespective of sequence.

In case of discrepancies in the results, we planned to explore heterogeneity analysing:

-

liver biopsy as the reference standard:

different grade of inflammation (amount of ongoing inflammation and necrosis) according to the liver biopsy (below two grades compared to two or greater grades of activity);

different lengths of liver biopsy sample (shorter than 15 mm compared to 15 mm or longer) or number of portal tracts (fewer than six compared to six or more), as reported in the studies;

percutaneous liver biopsy versus transvenous (transjugular) liver biopsy versus laparoscopic liver biopsy;

different technical characteristics of the ultrasonography equipment (e.g., different transducers, different wave lengths);

different skills of the operator as stated by the authors;

complete abstinent (teetotalers) or non‐abstinent study participants (as defined in the included studies).

In addition, we attempted to identify the most accurate ultrasonographic tests and indices for diagnosis of cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Diagnostic cohort study designs and diagnostic case‐control study designs that assessed alcoholic cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease through ultrasonography and liver biopsy, irrespective of language or publication status, or whether data were collected prospectively or retrospectively. We planned to include randomised clinical trials or controlled clinical studies had they fulfilled the inclusion criteria of our review protocol.

We included studies published as full paper articles, in the form of abstracts published in conference proceedings, or presented as posters if any of these were identified with the searches.

We also considered studies if they had included participants with different aetiologies of liver disease.

Participants

Participants of any sex and ethnic origin, over 16 years old, and diagnosed with alcoholic liver disease, following study authors' statements. The participants could have been hospitalised or managed as outpatients.

The diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease in the study participants should have been established based on registered history of excessive alcohol intake of sufficient duration and quantity together with clinical evidence of liver disease expressed with physical signs at examination and followed by laboratory evidence of liver disease. To ascertain the diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease and study the presence or absence of cirrhosis, both ultrasonography and liver biopsy should have been performed, irrespective of the sequence.

We planned to also include participants if suspected of having non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease, in addition to diagnosed alcoholic liver disease.

We did not consider for inclusion people diagnosed with alcoholic liver disease and having a concomitant liver disease such as chronic hepatitis C virus infection, chronic hepatitis B virus infection, autoimmune liver disease, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. We extracted data on study participants with alcoholic liver disease alone whenever such data were available in the study report or whenever we could obtain the data required for the review through personal communication with study authors. In the latter case, we disregarded some of the data presented in the publication and used the data provided by the study authors through personal communication.

Index tests

Ultrasonography in any mode.

As we expected that study authors would have used different measurements, signs, and combinations of signs for assessment of cirrhosis by ultrasonography with different techniques and mode, we did not specify these here in advance. However, we considered parenchymal, vascular, and extrahepatic ultrasonographic signs as different index tests.

Target conditions

There are five stages of liver fibrosis by METAVIR (Table 2):

F0 = no fibrosis;

F1 = mild fibrosis;

F2 = significant fibrosis;

F3 = severe fibrosis;

F4 = cirrhosis.

The target condition is the presence of cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease, defined using the METAVIR score.

Thus, we dichotomised the fibrosis estimated by the METAVIR score as follows: we considered people with a METAVIR score of F4 as 'diseased' and people with a METAVIR score of F0 plus F1 plus F2 plus F3 as 'non‐diseased'.

Reference standards

Liver biopsy.

Liver biopsy could have been obtained by percutaneous needle techniques with needles 1.4 to 1.6 mm (16 to 18 gauge) in diameter, transjugular method, or surgical specimens including laparoscopy (Kuntz 2008; Ivashkin 2011b).

Liver biopsy is the only existing reference standard for diagnosing hepatic cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease. Specimens of liver tissue with a length of at least 15 mm and at least six portal tracts are among the factors that can provide reliable morphological diagnosis of cirrhosis (Bedossa 2003; Colloredo 2003; Rockey 2009).

If liver biopsy samples were reported with any of the semi‐quantitative scores, that is, METAVIR (Michalak 2003), Knodell (Franciscus 2007), Ishak (Franciscus 2007), Kleiner (Kleiner 2005), Scheuer (Regev 2002), Brunt (Brunt 1999), or Batts‐Ludwig (Haque 2010), we planned to use a conversion grid for hepatic fibrosis staging adapted after Goodman 2007 to only unify results for hepatic cirrhosis on liver biopsy (Table 2). METAVIR has already been validated for staging alcoholic cirrhosis (Michalak 2003).

Search methods for identification of studies

We combined electronic searches with reading references of identified studies of possible interest.

Electronic searches

We searched The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register, The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies Register (hbg.cochrane.org/specialised‐register), The Cochrane Library (Wiley), MEDLINE (OvidSP), EMBASE (OvidSP), and Science Citation Index EXPANDED (de Vet 2010). Appendix 1 shows the search strategies with the time spans of the searches. We applied no language limitations.

Searching other resources

We also screened references of the retrieved studies to identify other potentially relevant studies for inclusion in our review. We considered extracting data from studies presented in an abstract or poster form, or from grey literature only if data for our review could be found.

Data collection and analysis

We followed the guidelines provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy.

Selection of studies

Three review authors (CP, MP, and EL) independently identified studies for possible inclusion in the review. While reading titles or abstracts, or both, of the identified studies, we excluded references with a study design not fulfilling the inclusion criteria of our review protocol. We retrieved the full text of the remaining references. During this second selection stage, we grouped together multiple publications of one study fulfilling the inclusion criteria, and then we screened these publications for complimentary data and we checked them for discrepancies. Whenever we were in doubt, CP, GC, or DN wrote e‐mails to study authors.

The studies that we included should have evaluated ultrasound in the diagnosis of hepatic cirrhosis using only liver biopsy as the reference standard.

The maximum time interval of investigation with liver biopsy and ultrasonography should not have exceeded six months. In addition, ultrasonography could have been performed before or after liver biopsy.

Data extraction and management

Three review authors (CP, GC, and MP) independently extracted data following the protocol. There were no disagreements between review authors extracting the data.

The data needed for the conductance of this systematic review were study origin, year and language of publication, study design, participants' epidemiological and laboratory characteristics, definition of alcoholic liver disease as defined by the authors of the individual studies considered for inclusion, technical failures in undertaking liver biopsy and ultrasonography, cirrhosis estimated by morphological score and ultrasonography, and information related to the QUADAS‐2 items for evaluation of the risk of bias of the studies (Whiting 2011).

In order to provide data for our analyses, the studies had to provide data that could help us calculate the true positive, false positive, true negative, and false negative diagnostic values of ultrasonography for diagnosing cirrhosis.

If information on any of the true positive, false positive, true negative, and false negative diagnostic test values or results were missing, we contacted the authors of the included studies in order to obtain missing information. We also contacted authors if other types of information needed for this review were missing, especially when the publication was in the form of an abstract or poster presentation.

We used Excel and Review Manager 5 to add data required for statistical analyses (RevMan 2014).

Assessment of methodological quality

Design flaws in test accuracy studies can produce biased results (Lijmer 1999; Whiting 2004; Rutjes 2006). In addition, evaluation of study results is quite often impossible due to incomplete reporting (Smidt 2005).

To limit the influence of different biases, four review authors (CP, GC, MP, and DN), in pairs or independently of one another, assessed the bias risk of the included diagnostic test accuracy studies, using QUADAS‐2 domains (Whiting 2011). A fifth review author (ET) was to act as an arbitrator in case of disagreements between the authors assessing the bias risk of the studies. We contacted study authors if information on methodology was lacking in order to assess correctly the risk of bias of the studies.

Appendix 2 shows the adopted items that served the purposes of our review in addressing the participant spectrum, index test, target condition, reference standard, and flow and timing, and which answers also reflect the general quality of the included studies.

We classified studies at low risk of bias if all answers to the signalling questions of the four domains and applicability were positive. We classified the studies at high risk of bias if at least one answer to the signalling questions of the four domains and applicability was either negative or unclear (Jüni 1999; Whiting 2005).

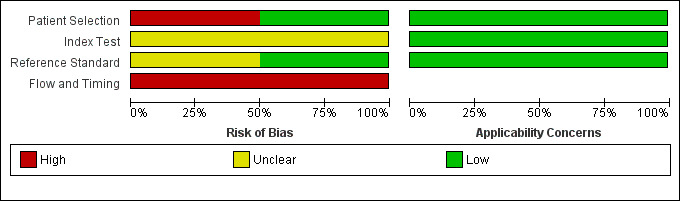

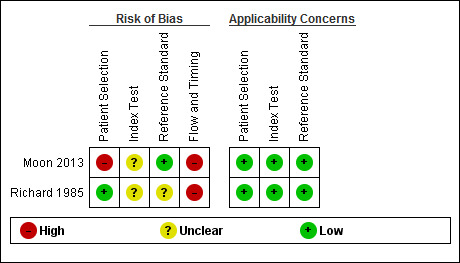

We used tabular and graphical displays to summarise QUADAS‐2 assessments.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

We carried out the analyses following Chapter 10 (Analysing and Presenting Results) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy (Macaskill 2010). We used Review Manager 5 software for analyses and plots (RevMan 2014).

When we had assembled the majority of our studies, we planned to map the individual index tests or index test indices in the individual studies and on the basis thereof determine which to select for meta‐analyses. We built two‐by‐two tables of ultrasonography performance (true positive, true negative, false positive, false negative) for each primary study and for each index test (ultrasonography mode) and for the pre‐defined target condition (cirrhosis). We estimated sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR+ and LR‐), positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). First, we performed a graphical descriptive analysis of the included studies: we reported forest plots (sensitivity and specificity separately, with their 95% CIs) and we planned to provide a graphical presentation of the studies in the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) space (sensitivity plotted against 1 ‐ specificity). Second, we planned to perform a meta‐analysis. Where case studies provided dichotomised data using a common cut‐off, we planned to use the bivariate model and to provide the estimate of the summary operating point (the point with mean sensitivity and mean specificity). Otherwise, we intended to use the hierarchical summary ROC (HSROC) model and to provide a summary ROC curve (Macaskill 2010). We planned to perform all analyses for each test separately.

In case of undetermined ultrasonography results, we planned to follow the intention‐to‐diagnose approach following which we intended to add uninterpretable test results as false positive or false negatives, depending on the liver biopsy result. In this way, we hoped to avoid potential overestimation of diagnostic test accuracy of ultrasonography (Schuetz 2012).

We planned to use the pooled estimates obtained from the fitted models to calculate summary estimates of likelihood ratios. We intended to assess the probability of ultrasonography to rule in or to rule out hepatic cirrhosis by considering the estimates of likelihood ratios. A high LR+ (usually greater than 10) means that there is a large increase in post‐test probability, starting from pre‐test probability. A low LR‐ (usually lower than 0.1) means that there is a large decrease in post‐test probability, starting from pre‐test probability (Schoenfeld 1999). Likelihood ratio estimates can be used in clinical practice to calculate post‐test probabilities for individual people, starting from patient‐specific pre‐test probabilities.

We planned to perform direct and indirect comparisons between the index tests by adding co‐variates to the bi‐variate or HSROC model (Macaskill 2010). In case of inconsistency of the results obtained through direct and indirect comparisons, we intended to report both results; otherwise, we planned to report one of the results, depending on the availability of comparisons.

One review author (GC) planned to perform all statistical analyses using SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Investigations of heterogeneity

We did not expect that the ultrasonographic tests and indices used for diagnosis of cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease would cause additional heterogeneity to those already mentioned in Secondary objectives.

Whenever possible, we planned to evaluate the effect of the pre‐specified sources of heterogeneity on the accuracy estimates by adding some relevant co‐variates to the bivariate model (Secondary objectives).

Sensitivity analyses

If possible, depending on number of studies with low risk of bias, we planned to assess the effect of risk of bias of the included studies on the diagnostic accuracy by performing a sensitivity analysis, excluding studies with high or unclear risk of bias, and perform a separate sensitivity analysis excluding unblinded studies.

We classified a study with high risk of bias if judged as high risk of bias or unclear risk of bias in at least one of the domains of QUADAS‐2 (Appendix 2).

We also planned to perform a sensitivity analysis of studies with data received from study authors.

Assessment of reporting bias

We planned to create a funnel plot to investigate reporting bias visually, using the statistical method suggested by Deeks et al. (Deeks 2005).

Results

Results of the search

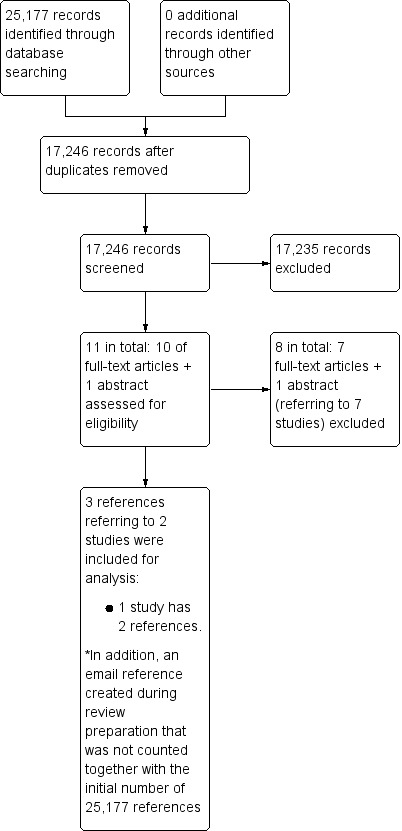

We identified 25,177 references through electronic searches of The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register (119 references), The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Diagnostic Test Accuracy Register (26 references), The Cochrane Library (487 references), MEDLINE (OvidSP) (5927 references), EMBASE (OvidSP) (14,266), and Science Citation Index Expanded (4352 references). We identified no additional studies by searching other sources. After exclusion of duplicates, 17,246 references remained. Having performed two selections, we found that 17,235 were irrelevant references. Eleven references seemed to fulfil the inclusion criteria. However, we had to exclude eight of these references referring to seven studies, and thus three references describing two studies remained for inclusion in our review. We extracted data for the two‐by‐two tables from two studies; one published as a full‐text article (Richard 1985), and the other provided individual participant data through personal correspondence, which created a new reference (Moon 2013). The Richard 1985 study was performed in France, and the Moon 2013 study was performed in South Korea and was sponsored by a grant from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. We did not contact the authors of the French study because of the old year of publication. We contacted by e‐mail two of the study investigators of the Korean study (KM Moon and SK Baik) (see Notes of the Characteristics of included studies and Excluded studies) in order to clarify if the three publications identified shared the same study participants. As a result, we received incomplete individual participant data on 105/173 participants in an Excel file. The authors expressed their regret for losing part of the data due to technical problems. This happened after publication of their article (Moon 2013).

Six of the seven excluded studies (referred to above) could have been included in our review had it been possible to extract data for the two‐by‐two table with the available data (Saverymuttu 1986; Joseph 1991; Ferral 1992; Gaiani 1997; Aubè 1999; Colli 2003) (see Characteristics of excluded studies table). We contacted the authors of three studies (Ferral 1992; Aubè 1999; Colli 2003), and received two replies (see Excluded studies). We did not contact authors of two studies as the studies were old (Saverymuttu 1986; Joseph 1991). The study by Gaiani 1997 included too few participants (see Characteristics of excluded studies table). The remaining study was Kim 2013, and through personal communication with two of the study authors of the Moon 2013 study, we were told that the Moon 2013 and Kim 2013 studies shared the same participants.

No studies were awaiting classification.

Figure 2 shows the reference flow.

2.

Study flow diagram.

Characteristics of included studies

We have summarised the characteristics of the two included studies in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Study design

The two included studies were prospective cohort single‐centre studies (Richard 1985; Moon 2013) (Characteristics of included studies table).

Funding

Richard 1985 did not provide any data and Moon 2013 was supported by a grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI10C2020).

Participants

Richard 1985 included only participants with alcoholic liver disease, while Moon 2013 included a heterogeneous group of participants with alcoholic liver disease, viral hepatitis, and cryptogenic hepatitis. However, through personal communication, we obtained individual participant data for only people with alcoholic liver disease (Moon 2013). No participants were suspected of having non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease in addition to the alcoholic liver disease they were diagnosed with. The two studies included hospitalised participants of both sexes. The participants' mean age in Richard 1985 was 55.6 years (57.4 years for men and 53.8 years for women), and in Moon 2013, the participants' mean age was 50.5 years (51.1 years for men and 44.0 years for women).

The number of participants with alcoholic liver disease in the two studies was 205. Richard 1985 included 128 participants with alcoholic liver disease, out of which 72 had alcoholic cirrhosis on liver biopsy, and Moon 2013 sent us individual participant data on 105 participants with alcoholic liver disease, and among them, 70 had alcoholic cirrhosis. Therefore, there were 142 participants with fibrosis stage F4 (i.e., alcoholic cirrhosis). All of these participants underwent both the index test (ultrasonography) and the reference standard (liver biopsy).

The study by Moon 2013 also compared the accuracy of ultrasonography versus transient elastography in terms of the degree of hepatic fibrosis.

Richard 1985 did not sufficiently report the definition of the diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease; the study authors wrote that the included participants had been drinking 80 g of alcohol per day for no less than one month before hospitalisation. Moon 2013 provided only general characteristics of the participants with cirrhosis.

Richard 1985 performed liver biopsy after ultrasonography in 100/128 participants, but they did not specify the time interval. Moon 2013 performed liver biopsy within one day after ultrasonography in 105 of the participants following the individual participant data received by Moon through personal communication.

Liver biopsy morphological scoring systems

Richard 1985 did not describe the morphological scoring systems, and Moon 2013 used METAVIR fibrosis scoring system (F0 to F4).

Grade of inflammation

Moon 2013 did not report the level of inflammation. Richard 1985 reported the presence of steatosis in study participants, but the data reported did not allow us to assess the grade of steatosis or level of inflammation.

Length of liver biopsy specimen and number of portal tracts

Moon 2013 excluded participants with liver biopsy specimen lengths less than 15 mm or less than six portal tracts from the analysis. However, we do not know how many of these excluded participants had alcoholic cirrhosis. Richard 1985 provided no information.

Type of liver biopsy

Richard 1985 used laparoscopic liver biopsy in 62 participants and percutaneous liver biopsy in 38 participants. Moon 2013 did not report this information.

Study information on the index test ‐ ultrasonography

Richard 1985 evaluated the following eight ultrasonography signs in combination and each one individually: volume of the liver, irregular outline, coarse echo patterns, fine bright echo patterns, attenuation of the ultrasound beam, splenomegaly, ascites, and portal hypertension. The ultrasonograph used was real‐time ultrasound equipment with a 3.5 MHz convex probe (Toshiba). One operator performed one ultrasonography examination per participant. They used B‐mode ultrasonography.

Moon 2013 developed an ultrasonographic scoring system (USSS) based on six ultrasonography B‐mode and Doppler imaging features, used in clinical practice. These features were liver surface and edge nodularity, parenchyma echogenicity, presence of right lobe atrophy, spleen size, splenic vein diameter, and abnormality of hepatic waveform, to evaluate hepatic cirrhosis. Based on the evaluation of each of the six features (with values of 0, 1, and 2), they produced a total score for prediction of liver cirrhosis. The ultrasonograph used was the Prosound alpha10 (Aloka, Tokyo, Japan), with a 3.5 MHz convex probe. There was one operator who performed all ultrasonography examination to determine the USSS.

Neither study reported follow‐up.

The common signs used by Richard 1985 and Moon 2013 were irregular outline (which corresponds to liver surface and edge nodularity in Moon 2013) and splenomegaly (which corresponds to spleen size in Moon 2013). However, coarse echo patterns, fine bright echo patterns, and attenuation of the ultrasound beam are three signs unified in one by Moon 2013 and described as parenchyma echogenicity. This is why, we present the signs in separate.

Methodological quality of included studies

Figure 3 and Figure 4 summarise the methodological quality in the included studies. The overall risk of bias of both Moon 2013 and Richard 1985 was high. However, there were no applicability concerns.

3.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns graph: review authors' judgements about each domain presented as percentages across included studies.

4.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns summary: review authors' judgements about each domain for each included study.

Findings

Two studies that provided numerical data regarding alcoholic cirrhosis in men and women with alcoholic liver disease fulfilled the inclusion criteria of our review. We could use the data of 205 participants for our analysis. Although there were no applicability concerns in terms of participants selection, index text, and reference standard, we judged the two studies to be at high risk of bias (low quality of evidence). Our analyses of the data showed that the studies shared only a few comparable clinical signs and symptoms, and the results of the studies were heterogeneous. These were the reasons not to perform a meta‐analysis.

Participants in both studies had undergone both liver biopsy and ultrasonography investigations. The authors of the two studies presented their results separately for each ultrasonographic feature, as well as combined in an overall sensitivity and specificity. The two studies shared only three of the investigated features (see Table 1). A visual comparison of the sensitivity and specificity results showed substantial differences. The specificities obtained by Moon 2013 (from 9% to 31% for six features and 49% overall specificity) were much lower than the obtained specificities by Richard 1985 (from 29% to 96% for eight features and 79% overall specificity). The same was also observed for the three common ultrasonography features reported separately as well as the specificity of the overall ultrasonography results. In general, the ultrasonographic features investigated by Moon 2013 had low specificity and higher sensitivity (90% to 100%, overall sensitivity 94%) than by Richard 1985 (from 4% to 81%, overall sensitivity 81%).

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this review, we aimed to determine the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography in B‐mode or Doppler imaging for detecting the presence or absence of liver cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease compared with liver biopsy as reference standard, irrespective of sequence. We also attempted to determine the diagnostic accuracy of any of the ultrasonography features. We planned to explore heterogeneity regarding liver biopsy, ultrasonography equipment and indices used, operator skills, or study participants.

We included two studies that provided numerical data regarding alcoholic cirrhosis in men and women with alcoholic liver disease. Our review was based on 205 participants. We judged both of these studies at high risk of bias due to flow and timing (Richard 1985; Moon 2013), and due to participant selection (Moon 2013). Participants in both studies had undergone both liver biopsy and ultrasonography investigations.

Data for ultrasonography were not available for one participant in Richard 1985 study, but we could not determine how many participants lacked data on ultrasonography in the Moon 2013 study.

A meta‐analysis was not possible due to the very low number of studies (i.e., two).

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

Despite that we searched the literature systematically for all published studies on ultrasonography versus liver biopsy for alcoholic cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease and that no one else so far has attempted to systematically collect the evidence on the use of the ultrasonography technique as a first‐line diagnostic tool following clinical guidelines, we now should consider these points as weaknesses in title formulation. At the time when we developed our idea for this review, we built it on the assumption that liver fibrosis develops differently due to the different aetiological factors causing the liver injury. Following the research of Verrill and colleagues, being abstinent from alcohol for one month after diagnosis of early cirrhosis will improve the chance of a seven‐year life expectancy by 1.6 times in people with alcoholic liver disease (Verrill 2009). Furthermore, the prevalence of cirrhosis in heavy drinkers is still not well known. The volume of the liver may be affected much more during alcohol abuse, and its dimension, among other ultrasound parameters, would depend on the cause of the liver disease (Richard 1985; O'Shea 2010; Moon 2013). However, uniform assessment of the extent of liver damage on ultrasonographic image by radiologists is not easy to achieve due to the subjective assessment of a large number of indices and signs. All this can affect the diagnostic accuracy of the ultrasound imaging technique in diagnosing cirrhosis, and this could also have been an obstacle for study investigators to perform studies assessing the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography using the same or similar sets of signs and features. Hence, we have chosen to address the diagnostic test accuracy of ultrasonography in only people with alcoholic liver disease.

We found only two studies that heterogeneous results and we could not pool the data. We found a number of studies that at first selection fulfilled our inclusion criteria, but we could not separate the data on alcoholic cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease from the data of cirrhosis that was due to various aetiologies of the liver disease. We also found other studies that of ultrasonography for detection of fibrosis, but liver biopsy was not the reference standard.

The information provided in the studies and through personal correspondence was not sufficient to fill in lacking knowledge on whether alcoholic cirrhosis can be identified by using signs or combinations of signs on ultrasonography.

Applicability of findings to the review question

Despite the relevance of the review question, we could not present any findings since we only identified two studies.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

As the accuracy of the listed ultrasonography features in the two included studies, singly or as a score, was not sufficiently informative, we cannot recommend the use of ultrasonography as a diagnostic tool for liver cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease.

Implications for research.

In order to answer the review questions, we need diagnostic ultrasonography prospective studies of adequate sample size, enrolling only participants with alcoholic liver disease. The design and report of the studies should follow the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (The STARD statement). The sonographic features, with validated cut‐off values, which may help to identify hepatic signs used for diagnosis of cirrhosis in alcoholic liver disease should be carefully selected in order to achieve consensus among radiologists and maximum diagnostic accuracy on ultrasonography.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sarah Louise Klingenberg, Denmark, for drafting search strategies, and Mirella Fraquelli, Italy and Agostino Colli, Italy, for useful comments. We thank Kyoung Min Moon and Soon Koo Baik for providing us with some of their individual participant data regarding their study (Moon 2013). Peer reviewers: contact editors from The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group: Mirella Fraquelli, Italy; Agostino Colli, Italy. Contact editor from The UK Diagnostic Accuracy Reviews Editorial Team: anonymous.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| Database | Time span | Search strategy |

| Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register | January 2015. | (ultrason* or ultrasound* or echograph* or echotomograph* or doppler* or B‐mode or B‐scan or grey*scale) AND ((hepatic or liver) and (fibrosis or cirrhosis)) |

| Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Diagnostic Test of Accuracy Studies Register | January 2015. | (ultrason* or ultrasound* or echograph* or echotomograph* or doppler* or B‐mode or B‐scan or grey*scale) AND ((hepatic or liver) and (fibrosis or cirrhosis)) |

| The Cochrane Library | Issue 12 of 12, 2014. | #1 MeSH descriptor: [Ultrasonography] explode all trees #2 (ultrason* or ultrasound* or echograph* or echotomograph* or doppler* or B‐mode or B‐scan or grey*scale) #3 #1 or #2 #4 MeSH descriptor: [Liver Cirrhosis] this term only #5 ((hepatic or liver) and (fibrosis or cirrhosis)) #6 #4 or #5 #7 #3 and #6 |

| MEDLINE (OvidSP) | 1946 to January 2015. | 1. exp Ultrasonography/ 2. (ultrason* or ultrasound* or echograph* or echotomograph* or doppler* or B‐mode or B‐scan or grey*scale).mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] 3. 1 or 2 4. exp Liver Cirrhosis/ 5. ((hepatic or liver) and (fibrosis or cirrhosis)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] 6. 4 or 5 7. 3 and 6 |

| EMBASE (OvidSP) | 1974 to January 2015. | 1. exp echography/ 2. (ultrason* or ultrasound* or echograph* or echotomograph* or doppler* or B‐mode or B‐scan or grey*scale).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] 3. 1 or 2 4. exp liver cirrhosis/ 5. exp liver fibrosis/ 6. ((hepatic or liver) and (fibrosis or cirrhosis)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] 7. 4 or 5 or 6 8. 3 and 7 |

| Science Citation Index Expanded | 1900 to January 2015. | #3 #2 AND #1 #2 TS=((hepatic or liver) and (fibrosis or cirrhosis)) #1 TS=(ultrason* or ultrasound* or echograph* or echotomograph* or doppler* or B‐mode or B‐scan or grey*scale) |

Appendix 2. QUADAS‐2

| Domain | Participant selection | Index test | Reference standard | Flow and timing |

| Description |

Describe methods of participant selection: describe included participants (prior testing, presentation, intended use of index test, and setting): The studies that fulfil the inclusion criteria of this review should have included participants of any sex and ethnic origin, > 16 years old, and diagnosed with alcoholic liver disease. The participants could have been hospitalised or managed as outpatients. The diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease had to be established based on registered history of excessive alcohol intake of sufficient duration and quantity together with clinical evidence of liver disease expressed with physical signs at examination and followed by laboratory evidence of liver disease. We excluded other causes of liver disease such as viral hepatitis, autoimmunity, metabolic diseases, and toxins. To ascertain the diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease and study the presence of cirrhosis, both ultrasonography and liver biopsy had to be performed, irrespective of the sequence. |

Describe the index test and how it was conducted and interpreted: Ultrasonography for diagnosing cirrhosis, conducted before or after liver biopsy. |

Describe the reference standard and how it was conducted and interpreted: Liver biopsy with ≥ 6 portal tracts or length of liver biopsy specimen > 15 mm was considered adequate in establishing cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease. The morphological interpretation of the liver biopsy samples was reported with semi‐quantitative scores such as METAVIR, Knodell, Ishak, Kleiner, Scheuer, Brunt, or and Batts‐Ludvig (see Table 1). |

Describe any people who did not receive the index test(s) or reference standard (or both) or who were excluded from the 2 x 2 table (refer to flow diagram): describe the time interval and any interventions between index test(s) and reference standard: As early cirrhosis may reverse with time in abstinent people, but mild to moderate fibrosis may evolve to cirrhosis in non‐abstinent people, we excluded participants if the time interval between diagnostic liver biopsy and ultrasonography investigations was > 6 months. |

| Signalling questions: yes/no/unclear |

Was a consecutive or random sample of participants enrolled? Yes: all consecutive participants or random sample of people with diagnosed alcoholic liver disease were enrolled in the study. No: selected participants were not included. Unclear: insufficient data were reported to permit a judgement. |

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes: ultrasonography test results were interpreted without knowledge of the results of the liver biopsy. No: ultrasonography results were interpreted with knowledge of the results of the liver biopsy. Unclear: insufficient data were reported to permit a judgement. |

Is the reference standard likely to classify the target condition correctly? Yes: if participants have undergone liver biopsy and the liver tissue specimen was deemed adequate for confident histological assessment. No: the liver tissue specimen was not deemed adequate for confident histological assessment. Unclear: insufficient data were reported to permit a judgement. |

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes: the interval between the ultrasonography and liver biopsy was ≤ 6 months. No: the interval between the ultrasonography test and liver biopsy was > 6 months. Unclear: insufficient data were reported to permit a judgement. |

|

Was a patient‐control design avoided? Yes: patient‐control design was avoided. No: patient‐control design was not avoided. Unclear: insufficient information was reported to permit a judgement. |

If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? Yes. No. Unclear: it is not reported or not clearly described. |

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes: liver biopsy results were interpreted without knowledge of the results of the ultrasonography test. No: liver biopsy results were interpreted with the knowledge of the results of the ultrasonography test. Unclear: insufficient data were reported to permit a judgement. |

Did all participants receive the reference standard? Yes: all participants underwent the reference standard, liver biopsy. No: not all participants underwent liver biopsy. Unclear: insufficient data were reported to permit a judgement. |

|

|

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? Yes: the study avoided inappropriate exclusions (e.g., difficult to diagnose participants, failure at liver biopsy, failure on ultrasonography). No: the study excluded participants inappropriately. Unclear: insufficient data were reported to permit a judgement. |

Did all participants receive the same reference standard? Yes: all participants received the same reference standard (i.e., liver biopsy). No: not all participants received the same reference standard (i.e., liver biopsy). Unclear: insufficient data were reported to permit a judgement. |

|||

|

Were all participants included in the analysis? Yes: all participants meeting the selection criteria (selected participants) were included in the analysis, or data on all the selected participants were available so that a 2 x 2 table including all selected participants could be constructed. No: not all participants meeting the selection criteria were included in the analysis or the 2 x 2 table could not be constructed using data on all selected participants. Unclear: insufficient data were reported to permit a judgement. | ||||

| Risk of bias: high/low/unclear |

Could the selection of participants have introduced bias? High risk of bias: yes, if the selection of participants could have introduced bias. Low risk of bias: no, if the selection of participants could not have introduced bias. Unclear risk of bias: insufficient data on participant selection were reported to permit a judgement on the risk of bias. |

Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? High risk of bias: if the answer to the signalling questions on the conduct or interpretation of the index test was 'no'. Low risk of bias: if the answer to the signalling questions on the conduct or interpretation of the index test was 'yes'. Unclear risk of bias: if the answers to the 2 signalling questions on the conduct or interpretation of the index test was either 'unclear' or any combination of 'unclear' with 'yes' or 'no'. |

Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? High risk of bias: if the answer to the signalling questions on the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation was 'no'. Low risk of bias: if the answer to the signalling questions on the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation was 'yes'. Unclear risk of bias: if the answers to the 3 signalling questions on the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation was either 'unclear' or any combination of 'unclear' with 'yes' or 'no'. |

Could the participant flow have introduced bias? High risk of bias: if the answer to the signalling questions on flow and timing was 'no'. Low risk of bias: if the answer to the signalling questions on flow and timing was 'yes'. Unclear risk of bias: if the answers to the 4 signalling questions on flow and timing was either 'unclear' or any combination of 'unclear' with 'yes' or 'no'. |

| Concerns regarding applicability: high/low/unclear |

Are there concerns that the included participants do not match the review question? High concern: there was high concern that the included participants did not match the review question. Low concern: there was low concern that the included participants did not match the review question. Unclear concern: if it was unclear. |

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differed from the review question? High concern: there was high concern that the conduct or interpretation of the ultrasonography test differed from the way it was likely to be used in clinical practice. Low concern: there was low concern that the conduct or interpretation of the ultrasonography test differed from the way it was likely to be used in clinical practice. Unclear concern: if it was unclear. |

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? High concern: all participants did not undergo liver biopsy for cirrhosis. Low concern: all participants underwent liver biopsy for cirrhosis. Unclear concern: if it is unclear. |

‐ |

Data

Presented below are all the data for all of the tests entered into the review.

Tests. Data tables by test.

| Test | No. of studies | No. of participants |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Ultrasonography | 2 | 205 |

| 2 Irregular outline (liver surface and edge nodularity) | 2 | 205 |

| 3 Splenomegaly (spleen size) | 2 | 205 |

| 4 Hepatomegaly | 1 | 100 |

| 5 Attenuation of the ultrasound beam | 1 | 100 |

| 6 Parenchyma echogenicity | 1 | 105 |

| 7 Coarse echo patterns | 1 | 100 |

| 8 Fine bright echo patterns | 1 | 100 |

| 9 Ascites | 1 | 100 |

| 10 Portal hypertension | 1 | 100 |

| 11 Right lobe atrophy | 1 | 105 |

| 12 Hepatic vein waveform | 1 | 105 |

| 13 Splenic vein diameter | 1 | 105 |

1. Test.

Ultrasonography.

2. Test.

Irregular outline (liver surface and edge nodularity).

3. Test.

Splenomegaly (spleen size).

4. Test.

Hepatomegaly.

5. Test.

Attenuation of the ultrasound beam.

6. Test.

Parenchyma echogenicity.

7. Test.

Coarse echo patterns.

8. Test.

Fine bright echo patterns.

9. Test.

Ascites.

10. Test.

Portal hypertension.

11. Test.

Right lobe atrophy.

12. Test.

Hepatic vein waveform.

13. Test.

Splenic vein diameter.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Moon 2013.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Prospective cohort study. | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Following the published article Moon 2013, 230 participants (187 men, 43 women; aged (mean ± standard deviation) 50.4 ± 9.5 years) with chronic liver disease; 173 with alcoholic liver disease, and 111 with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Prospectively measured and analysed: age, sex, height, weight, aetiology of cirrhosis, Child class, albumin, total bilirubin, prothrombin time, platelet count, liver stiffness measurement by transient elastography, and 6 ultrasound features (liver surface and edge nodularity, parenchyma echogenicity, right lobe atrophy, spleen size, splenic vein diameter, and hepatic vein waveform). All participants were studied using the 2 non‐invasive methods: transient elastography (FibroScan; Echosens, Paris, France) with a 3.5 MHz M probe and ultrasound (Prosound α10; Aloka, Tokyo, Japan) with a 3.5 MHz convex probe. Hospitalised. From October 2007 to February 2011, 230 participants admitted to the Wonju College of Medicine University Hospital with chronic liver disease who underwent liver biopsy were included in this study. |

||

| Index tests | USSS combining 6 representative sonographic indices in predicting cirrhosis. The USSS produced a combined score for nodularity of the liver surface and edge, parenchyma echogenicity, presence of right‐lobe atrophy, spleen size, splenic vein diameter, and abnormality of the hepatic vein waveform. The USSS score was evaluated against liver biopsy results. The study authors measured 13 ultrasonography features and the authors analysed each feature against the degree of hepatic fibrosis. They used a USSS cut‐off value of 6 for the diagnosis of overt cirrhosis, with sensitivity of 89.2% and specificity of 69.4%. Moon 2013 et al. suggested a cut‐off ≥ 6 for diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis by USSS. Ultrasound (Prosound α10; Aloka, Tokyo, Japan) with a 3.5 MHz convex probe. |

||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Alcoholic liver cirrhosis (111 participants); liver biopsy (METAVIR scoring system: F0 to F4). | ||

| Flow and timing | Liver biopsy was performed within 1 day after ultrasonography. | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | We received incomplete individual participant data, i.e., on 105/173 participants, by e‐mail. The authors expressed their regret for losing part of the data after publication of their article due to technical problems (Moon 2013). | ||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Yes | ||

| Was a case‐control design avoided? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | No | ||

| High | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test All tests | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | No | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | No | ||

| High | |||

Richard 1985.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Prospective cohort study design. | ||