Genome-wide molecular markers are produced by a bioinformatics pipeline that analyzes pairs of genomic sequences to find primer pairs that amplify indel-containing regions having a targeted amplicon size and size difference.

Abstract

Genetic markers are essential when developing or working with genetically variable populations. Indel Group in Genomes (IGG) markers are primer pairs that amplify single-locus sequences that differ in size for two or more alleles. They are attractive for their ease of use for rapid genotyping and their codominant nature. Here, we describe a heuristic algorithm that uses a k-mer-based approach to search two or more genome sequences to locate polymorphic regions suitable for designing candidate IGG marker primers. As input to the IGG pipeline software, the user provides genome sequences and the desired amplicon sizes and size differences. Primer sequences flanking polymorphic insertions/deletions are produced as output. IGG marker files for three sets of genomes, Solanum lycopersicum/Solanum pennellii, Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Columbia-0/Landsberg erecta-0 accessions, and S. lycopersicum/S. pennellii/Solanum tuberosum (three-way polymorphic) are included.

Genetic differences or DNA polymorphisms between individuals in a population are a primary cause of phenotypic variation. A critical step in characterizing the genetic basis of such phenotypic variation is the development of molecular genetic markers that enable the detection and identification of polymorphisms. Four properties describe a marker: the polymorphism it finds, the assay method used to detect it, the number of alleles identifiable at one locus, and the number of different loci at which alleles can be found. As new assays revealed increasing numbers of DNA polymorphisms, new types of markers were developed to detect them, each with its own acronym, including these common polymorphisms and representative types of markers: single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs [single-strand conformation polymorphism markers]; Orita et al., 1989; Wenzl et al., 2004), insertions/deletions (indels) of varying lengths (sequence-characterized amplified region markers; Paran and Michelmore, 1993; Robarts and Wolfe, 2014), restriction site locations (RFLP markers; Botstein et al., 1980; Konieczny and Ausubel, 1993; Vos et al., 1995; Miller et al., 2007), tandem repeat counts (variable number tandem repeat markers; Nakamura et al., 1987), and differences in polynucleotide repeat counts or lengths (simple sequence repeat [SSR] markers; Weber and May, 1989; Huang et al., 1991; Dietrich et al., 1992; Zietkiewicz et al., 1994). A more complete list of markers and their properties is given in Table I.

Table I. Genetic markers and their properties.

| Year | Acronyma | Nameb | Polymorphismc | Visualization Technique | Codomd | Loci Visualizede | Same asf | Referenceg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | RFLP | Restriction fragment length polymorphism | Variable length of restriction digest fragments | Southern hybridization to random probe | Mostly | One | Botstein et al. (1980) | |

| 1987 | VNTR | Variable number tandem repeat | Variable numbers of tandem repeats of short sequences | Southern hybridization to custom probe | Yes | Variable | Nakamura et al. (1987) | |

| 1989 | SSCP | Single-strand conformation polymorphism | Single-nucleotide polymorphisms and indels | Electrophoretic mobility shift of hybridized probe | Yes | One | Orita et al. (1989) | |

| 1989 | STS | Sequence-tagged site | Any polymorphism | Make tag by sequencing a contig from any marker type | N/A | N/A | Olson et al. (1989) | |

| 1989 | SSR | Simple sequence repeat | Variable numbers of short polynucleotide repeats | PCR using primers for flanking sequence, polyacrylamide gel | Yes | One | STR, SSLP, microsatellites | Weber and May (1989); Jacob et al. (1991) |

| 1990 | RAPD | Random amplified polymorphic DNA | Random presence/absence of primer sites in DNA | PCR with random primers discovered to flank polymorphisms, then gel | No | Many (fingerprinting) | Williams et al. (1990) | |

| 1991 | STR | Short tandem repeat | See SSR | See SSR | Yes | One | SSR, SSLP, microsatellites | Huang et al. (1991) |

| 1992 | SSLP | Simple sequence length polymorphism | See SSR | See SSR | Yes | One | SSR, STR, microsatellites | Dietrich et al. (1992) |

| 1993 | SCAR | Sequence-characterized amplified region | RAPD marker sites and length polymorphic sites | PCR with primers specific to internal or flanking sequence, then gel | Sometimes | One | Indel | Paran and Michelmore (1993) |

| 1993 | CAPS | Cleaved-amplified polymorphic sequence | Restriction site location variation | PCR using primers for unique flanking sequence, then digestion and gel | Yes | One | Konieczny and Ausubel (1993) | |

| 1994 | ISSR | Inter-simple sequence repeat | See SSR | PCR using short primers matching many flanking sequences, polyacrylamide gel | Yes | Many (fingerprinting) | Zietkiewicz et al. (1994) | |

| 1995 | AFLP | Amplified fragment length polymorphism | Variable length of restriction digest fragments | Digest, ligate adapters, PCR with primers partially specific to sequence, gel | Yes | Many (fingerprinting) | Vos et al. (1995) | |

| 1998 | RGA | Resistance gene analog | Plant disease resistance gene polymorphism | PCR with primers specific to disease resistance gene, polyacrylamide gel | Yes | Many (fingerprinting) | Chen et al. (1998); Ellis and Jones (1998); Meyers et al. (1999) | |

| 2001 | SRAP | Sequence-related amplified polymorphism | Indels in exons and introns | PCR, special primers with permissive temperature, polyacrylamide gel | Yes | Many (fingerprinting) | Li and Quiros (2001) | |

| 2004 | DArT | Diversity arrays technology | SNPs and indels | Semirandom sequence microarray hybridization and scanning | Sometimes | Variable | Wenzl et al. (2004) | |

| 2006 | SFP | Single-feature polymorphism | Variation in annealing affinity to 25-bp oligonucleotide | Specific sequence microarray hybridization and scanning | Sometimes | Variable | Borevitz et al. (2003) | |

| 2006 | GEM | Gene expression marker | Gene transcript level variation | Hybridize transcript library to specific sequence microarray, scan | Yes | One | West et al. (2006) | |

| 2007 | RAD | Restriction site-associated DNA | Sequence variation adjacent to restriction sites | Specific sequence microarray hybridization and scanning | No | One | Miller et al. (2007) | |

| – | Indel | Insertion/deletion | Indel | PCR with primers specific to internal or flanking sequence, then gel | Sometimes | One | SCAR | See Rafalski (2002) |

| – | SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism | SNP | Specific sequence microarray hybridization and scanning | Sometimes | One | See Rafalski (2002) |

Commonly used acronym for the marker.

Expanded acronym name.

Description of the polymorphism (and in some cases the visualization technique, which may be closely tied to the marker method).

Codominance status of the marker. N/A, Not applicable.

Number of different loci usually visualized by the marker (one for markers that assess a single locus; many for a fingerprint type of marker).

Other markers that are fundamentally the same type of marker despite having different names.

Reference to the article defining the marker technique and in some cases to the article first using the marker acronym. The marker acronym may have originated later than the invention of the marker technique, and the identification of the polymorphism upon which the marker is based may have occurred earlier than the invention of the technique.

Historically, visualization of polymorphic markers typically used restriction digests, Southern hybridization, and PAGE, augmented later with PCR and agarose gel with ethidium bromide staining, Sanger sequencing, and high-throughput genotyping using microarray technology and next-generation sequencing (NGS). Allele-specific marker assays detect a single allele to provide simple yes/no output, while codominant marker assays are able to detect the two different polymorphic states present in a heterozygote at the target locus. A marker is multiallelic if it is able to discriminate between many different polymorphisms in a population. Finally, a marker assay may visualize allele(s) at a single locus (e.g. used for linkage mapping a locus) or at multiple loci simultaneously (e.g. used for fingerprinting individuals in a population). The different properties of markers make each type useful in particular applications. The uses of markers span a broad range, from simple genotyping in the laboratory to areas as diverse as marker-assisted selection (Li et al., 2015), trait association mapping (Nachimuthu et al., 2015), ecology (Pradhan et al., 2015), synteny studies (Guyon et al., 2010), diversity surveys (Salehi et al., 2015), species authentication (Fu et al., 2015), sex determination (Kafkas et al., 2015), detection of adulterants (Marieschi et al., 2012), ingredient traceability (Ahmed et al., 2015), and forensics (Diegoli, 2015).

Marker assays can vary in scoring complexity. For instance, cleaved-amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS; Konieczny and Ausubel, 1993) markers allow for the characterization of multiallelic polymorphisms but are relatively low throughput, as they require an additional digestion step after PCR amplification. Indel markers (Rafalski, 2002; Shen et al., 2004) are usually described as a pair of PCR primers binding to single-copy (unique in the genome) sites flanking a single small indel whose size ranges from 1 to 100 bp. The assay requires PCR followed by either a high-percentage agarose gel or (especially for very small indels) a high-resolution polyacrylamide gel. As an example of indel marker amplicon sizes, over 100,000 rice (Oryza sativa) genome indel markers were designed by Liu et al. (2015) using an exhaustive genome search for single-copy primers, which were then aligned to sequence reads to identify polymorphic primer pairs in different rice varieties. These markers have amplicon sizes of no more than 300 bp (mean of 218 bp, using a 150- to 300-bp table) and size differences between target genotypes of 6 to 100 bp (mean of 51 bp). While indels make attractive marker targets because of ease of scoring and the absence of a digestion step, the current set of available markers in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), and rice is lacking, because small differences in amplicon sizes often can make resolution of genotyping difficult. Thus, there is a need for more high-throughput markers with easy-to-score length polymorphisms between target genotypes.

Historically, single-locus molecular genetic markers have been developed a few at a time for a specific species and genetically segregating population, often starting with a search for genetic polymorphism using a technique such as random amplification of polymorphic DNA followed by sequencing of amplicons and designing of primers specific to them. With the advent and increasing use of NGS, the number of organisms with sequenced genomes is rising rapidly (Reddy et al., 2015). When genomes (or portions thereof) are available for two or more genetically different but crossable species, subspecies, or accessions, they can be searched in silico for polymorphic regions suitable to make genetic markers to genotype polymorphic regions in progeny.

Custom software tools have been used to develop marker sets from whole-genome data; however, general-use open-access community software for whole-genome marker development is limited. Available tools include the Indel Markers Development Platform (IMDP) for indel markers (Lü et al., 2015), PolyMarker to generate SNP-specific primers around known SNPs (Ramirez-Gonzalez et al., 2015b), the EST SSR Marker Pipeline to find short sequence repeats for designing SSR markers (Sarmah et al., 2012), the CAPS Identifier for CAPS markers (Taylor and Provart, 2006), and a wet-lab-based marker array protocol using unsequenced whole-genome data to make restriction site-associated DNA markers (Miller et al., 2007).

In principle, high-throughput sequencing could be used for genotyping purposes as opposed to PCR-based markers. However, there are several limitations on genotyping by sequencing that make PCR-based marker genotyping an equally efficient and affordable method. NGS is currently suited to generate extensive SNP data, potentially on hundreds to thousands of individuals. However, it can be cost prohibitive due to the computational power needed for demultiplexing and performing parallel alignments and, in some cases, due to a need for extensive bioinformatics support that is not feasible in terms of skills or finances for all laboratories. Making non-reference-based alignments for genome or contig assembly and subsequent marker identification using NGS requires memory resources and computational power that often exceed the resources available (Salzberg et al., 2012; Kleftogiannis et al., 2013). Furthermore, fine-mapping genes from quantitative trait loci, even with NGS as a tool, still requires validation with PCR-based markers. Finally, the generation of a mapping population rapidly with fixed genomic intervals could be done much more quickly through the use of PCR-based markers, rather than preparing multiple sequencing libraries and waiting sometimes months for sequencing data to return and be analyzed.

We present IGG pipeline (IGGPIPE), a command line-based pipeline that uses a search algorithm and common, unique (single-copy) k-mers to sift through multiple target genomes and identify up to thousands of candidate Indel Group in Genomes (IGG) markers, in some cases multiallelic markers, in silico. IGG markers are benchmarked using cultivated tomato and Solanum pennellii as well as Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) accessions Columbia-0 (Col-0) and Landsberg erecta-0 (Ler-0). We further present IGG marker sets polymorphic between S. lycopersicum/S. pennellii, Arabidopsis accessions Col-0/Ler-0, and S. lycopersicum/S. pennellii/Solanum tuberosum (potato) and describe how the latter set is being utilized to develop an S. lycopersicum × Solanum sitiens introgression line population.

RESULTS

Development of IGGPIPE

Identification of Unique k-mers

The premise underlying IGG markers is that k-mers of sufficient size should often occur as a single copy in a genome, and when occurring in conserved locations, they will often occur as a single copy in both (or all) genomes under consideration. We call these common unique k-mers, common to both genomes and unique (single copy) within each genome. We reasoned that common unique k-mers could be used to identify conserved regions within contigs in all species, and by testing for differences in distance between same-contig common unique k-mers among the genomes, we could discover regions containing length polymorphisms flanked by conserved sequences. These polymorphic regions must contain one or more indels, the requirement for designing a length-polymorphic PCR marker. IGGPIPE (Fig. 1A) was built around this concept.

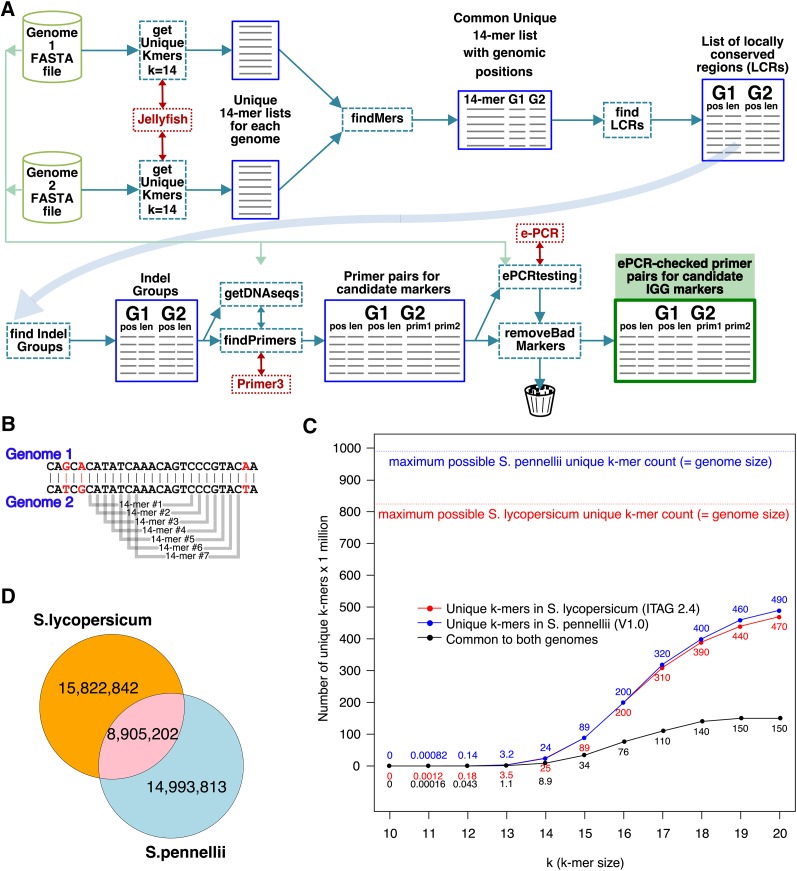

Figure 1.

A, IGGPIPE, an IGG marker-finder software pipeline. Two genome sequences (G1 and G2) are analyzed for common unique k-mers that identify locally conserved regions (LCRs), some of which are polymorphic for length, containing one or more indels between flanking conserved sequences, making them Indel Groups. Primers are designed in the flanking conserved regions and verified with e-PCR to produce candidate IGG markers. Pipeline software is shown in dashed boxes and data in solid boxes. B, A new k-mer starts at each base position. Shown here are seven consecutive 14-mers common to two genomes. C, Number of unique k-mers in S. lycopersicum and closely related S. pennellii as a function of k, and number of unique k-mers common to both species. As k increases, the number of unique k-mers increases, gradually approaching the genome size limit. The common unique k-mer count does not keep increasing, but at some value of k it will reach a peak, here around k = 19 or k = 20. D, With k = 14, S. lycopersicum and S. pennellii have almost 9 million unique k-mers in common between them.

We began by assessing the number of unique k-mers in a genome as a function of k (Fig. 1, B–D). Regardless of the value of k, a genome contains about the same total number of k-mers as nucleotides, since a k-mer starts at every base pair except those less than k from the end of a chromosome or contig (Fig. 1B). Using the S. lycopersicum (tomato) and S. pennellii (a tomato wild relative) genomes (Bombarely et al., 2011; Tomato Genome Consortium, 2012; Bolger et al., 2014), we counted unique k-mers and common unique k-mers for k ranging from 10 to 20 (Fig. 1C). The closely related genomes had about the same number of unique k-mers, and the number common between the two was roughly one-third of the total.

By testing increasing values of k, we found that k = 14 provided 8.9 million common unique k-mers (Fig. 1D) between S. lycopersicum and S. pennellii, and this number was sufficient to produce a few thousand IGG markers at the end of the pipeline, while k = 14 was small enough to reduce computational and memory load to satisfactory levels for our needs.

The identification of conserved regions is complicated by several features of genome architecture, some of which are illustrated in Figure 2A, where each small black line represents a common unique k-mer. One or two k-mers lying on the same genome 1 contig and the same genome 2 contig may not indicate a contiguous length of conserved sequence but may be a random occurrence (for an estimate of the random frequency of occurrence of common unique k-mers, see Supplemental Materials and Methods S1), illustrated by the shaded red boxes (a, b, and e). When there is more than one k-mer, if their ordering in one genome matches the ordering in the other genome, then as the number of such k-mers increases, so too does the likelihood that they lie within a conserved sequence. When a group of at least KMIN (a user-settable parameter typically set to a value from two to four) common unique k-mers has the same ordering on a single contig in each genome, we call the region containing them a locally conserved region (LCR). LCRs are illustrated by shaded blue boxes (c, d, f, g, h, i, and j) in Figure 2A. A group of k-mers in an LCR may encompass regions of equal length in both genomes (c, d, and j), or the lengths may be unequal because the genomes contain indels, whose locations are shown with loop-outs of the DNA (f–i). These LCRs containing indels are the length-polymorphic regions used to generate IGG markers and are shown as shaded blue boxes with borders.

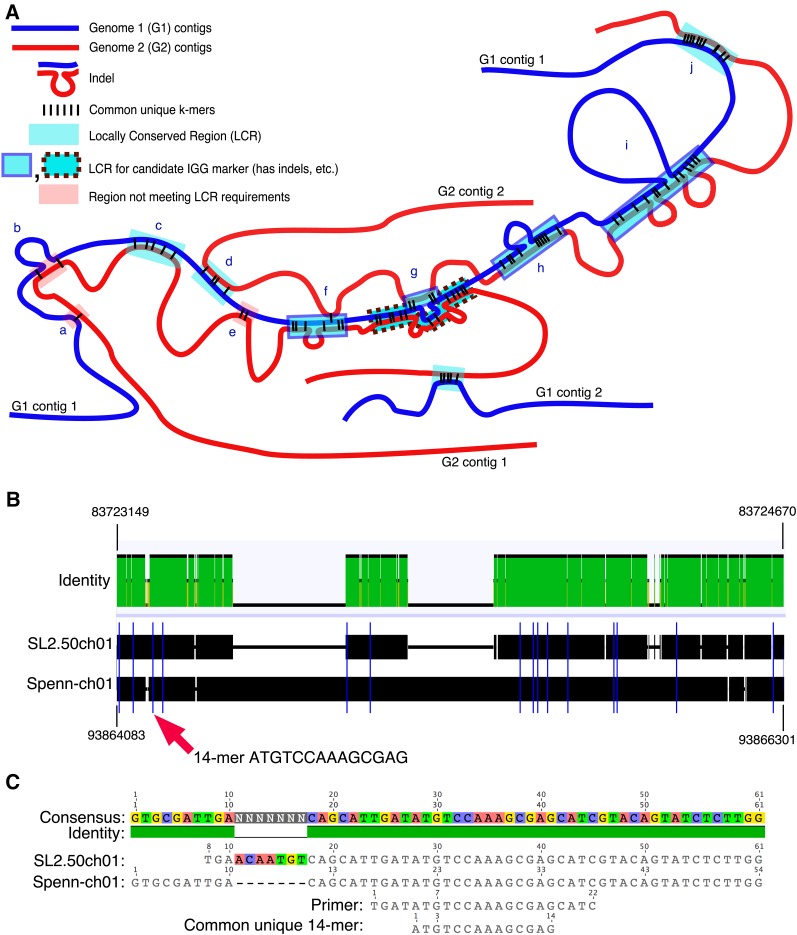

Figure 2.

A, LCRs are regions of paired contigs within the genomes under consideration (here G1 and G2) having a sufficient number and spacing of unique k-mers in common between the contigs. When indels are present within LCRs, they form the basis for creating candidate IGG markers. Common unique k-mers can connect pairs of contigs in many ways. The parameter DMAX is the maximum spacing between two adjacent k-mers of the same LCR, and k-mers farther apart than that are assigned to different LCRs. If the number of k-mers is less than parameter KMIN (here assumed to be 4), the k-mers are assumed to be random common unique k-mers not signifying a conserved region, and no LCR is called for that region (a, b, and e). LCRs may have no indels in them (c, d, and j) or there may be a single indel (b, f, and h) or more than one (i). Different LCRs along a contig of one genome might include different contigs in the other genome (a, b, c, and e versus d). Some LCRs may have one or more random interspersed k-mers connecting a contig pair that is different from the contig pair of the LCR (f). Some regions may have complex overlapping of more than one LCR (g). B, Alignment of S. lycopersicum and S. pennellii genomes in the region of an LCR on chromosome 1. Blue vertical lines are positions of common unique 14-mers. An indel is visible that might provide sufficient length polymorphism for an IGG marker surrounding this area. The red arrow points to one 14-mer whose region is enlarged below. C, Enlargement of the region around the third 14-mer in B, showing a multiple alignment of the S. lycopersicum and S. pennellii genome sequences in this region, the primer generated by IGGPIPE, and the 14-mer itself. Alignments were made with Geneious (Kearse et al., 2012).

Our algorithm for LCR identification, findLCRs, seeks groups of common unique k-mers in consecutive order on the same contig pair and satisfying parameter constraints while ignoring all other common unique k-mers (even if they are interspersed among the group being considered). When such a k-mer group is found, an LCR is called for the group and those common unique k-mers are removed from the pool under consideration. An alignment of part of an LCR and respective common unique k-mers in the tomato SL2.50/ITAG2.4 (Heinz) and S. pennellii V2.0 genomes is shown in Figure 2, B and C.

The LCR algorithm found 72,533 LCRs between the tomato SL2.50/ITAG2.4 (Heinz) and S. pennellii V2.0 genomes using parameter settings that included 1,500-bp maximum k-mer spacing (DMAX) and 400-bp minimum LCR length (LMIN; Table II). The number of common unique k-mers per LCR ranged from two to 642. We tested whether the LCRs truly represented common conserved regions by making a dot plot between the two genomes using the LCRs as data (Supplemental Fig. S1). The plot closely matches a similar dot plot made using data from a whole-genome alignment of the same genomes using the progressiveMauve (Darling et al., 2010) whole-genome aligner (Supplemental Fig. S2), confirming that LCRs include conserved regions found in whole-genome alignments.

Table II. Metrics for four separate runs of IGGPIPE on S. lycopersicum/S. pennellii genomes using four different sets of parameters.

Note how the initial unique k-mer pool (metric unique k-mers) is filtered down at each step of IGGPIPE until finally converging at nonoverlapping validated candidate IGG markers. Each run uses a different marker identifier prefix to distinguish the markers. The IGG markers from these runs are provided (Supplemental Data S1). The metrics k, KMIN, AMIN, AMAX, ADMIN, and ADMAX are all user-specified parameters.

| Metric | Run 1 (A) | Run 2 (B) | Run 3 (C) | Run 4 (D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker identifier prefix (ID_PREFIX) | IGG_HP14A_ | IGG_HP14B_ | IGG_HP14C_ | IGG_HP14D_ |

| Genome 1 | S. lycopersicum SL2.50 | Same | Same | Same |

| Genome 2 | S. pennellii V2.0 | Same | Same | Same |

| k | 14 | Same | Same | Same |

| Genome size (No. of k-mers) | 824/990 Mb | Same | Same | Same |

| Unique k-mers | 24.7/23.9 M | Same | Same | Same |

| Common unique k-mers | 8.9 M | Same | Same | Same |

| Minimum k-mers per LCR (KMIN) | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Minimum amplicon size (AMIN) | 200 | 250 | 300 | 400 |

| Maximum amplicon size (AMAX) | 700 | 800 | 800 | 1,500 |

| Minimum amplicon size difference at AMIN (ADMIN) | 100 | 100 | 200 | 50 |

| Minimum amplicon size difference at AMAX (ADMAX) | 100 | 200 | 200 | 300 |

| LCRs | 102 K | 106 K | 90.4 K | 72.5 K |

| Nonoverlapping Indel Groups | 11 K | 9.2 K | 5.0 K | 32 K |

| Overlapping Indel Groups | 333 K | 31.3 K | 113 K | 250 K |

| Overlapping unvalidated markers | 26.6 K | 11.7 K | 9.3 K | 97.6 K |

| Overlapping e-PCR-validated IGG markers | 21,654 | 9,437 | 7,163 | 91,947 |

| Nonoverlapping e-PCR-validated IGG markers | 5,526 | 3,720 | 2,332 | 16,442 |

Identification of Indel Groups

After LCRs are identified, the next step in the IGG marker pipeline is to examine each LCR’s common unique k-mers to find pairs whose separation distance is unequal in the two (or more) genomes and satisfies user-specified parameters. We use the name Indel Group for the interval between such a k-mer pair. The name includes group because the interval must contain at least one indel but may have more than one. A single LCR can contain more than one Indel Group, each one bounded by a different pair of k-mers. The Indel Group algorithm found 249,635 overlapping Indel Groups within the LCRs between the tomato SL2.50/ITAG2.4 (Heinz) and S. pennellii V2.0 genomes using parameter settings that included amplicon size between 400 and 1,500 bp and amplicon size difference between 50 bp (at 400-bp amplicon size) and 300 bp (at 1,500-bp amplicon size). Counting only one Indel Group from each set of overlapping Indel Groups reduced that total to 31,621 nonoverlapping Indel Groups between these genomes.

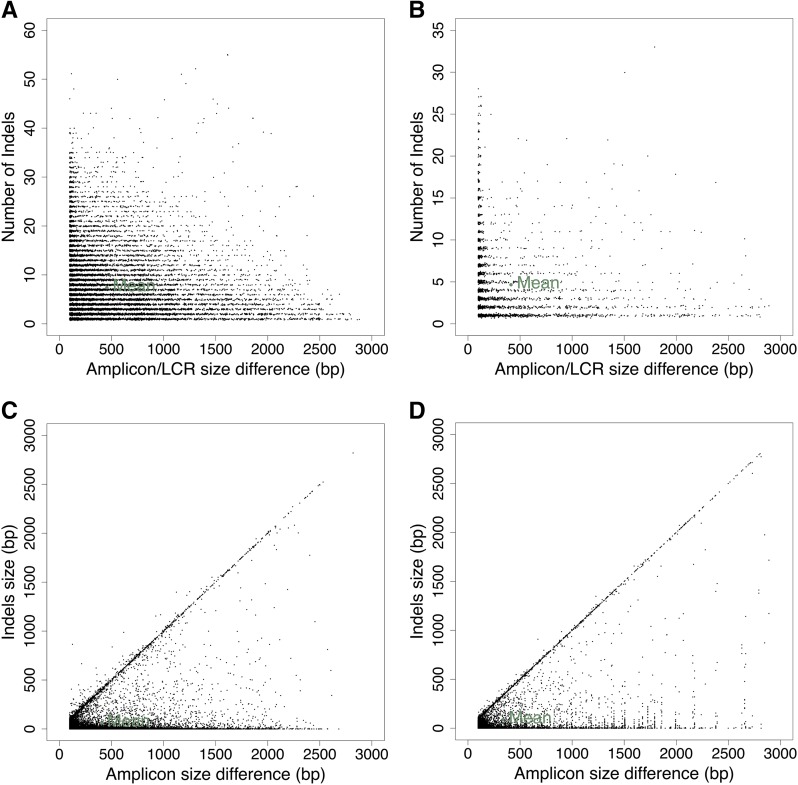

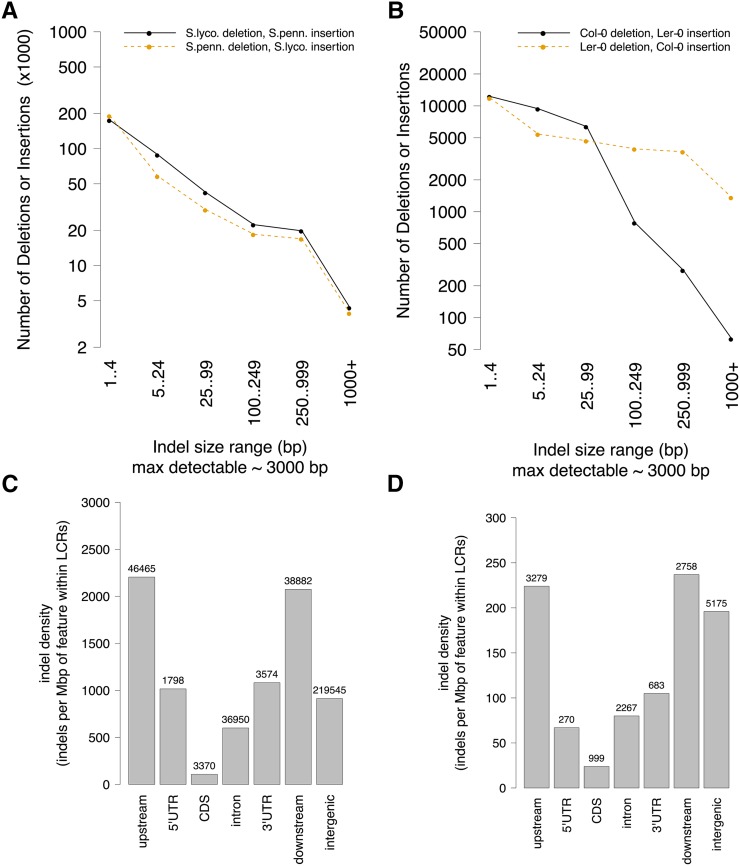

The number of indels within an Indel Group was confirmed to have a broad range (Fig. 3A), and the length of the indels also spans a broad range (Fig. 3C), although concentrated at smaller sizes. The number of indels of different sizes decreases approximately exponentially as the indel length increases (Fig. 4A; Supplemental Fig. S3). Indels within Indel Groups can be found in all of the gene features and intergenic regions (Fig. 4C). The density in coding regions is lowest, followed by intron, intergenic, 5′ untranslated region (UTR), 3′ UTR, and finally upstream and downstream, with approximately equal density. We compared these Indel Group count and density results with those from a similar analysis between Arabidopsis accessions Col-0 and Ler-0, shown side-by-side with tomato in Figures 3, B and D, and 4, B and D. The results are similar, although in Arabidopsis, the densities ranked somewhat differently, with coding regions again lowest, then 5′ UTR, intron, 3′ UTR, intergenic, upstream, and downstream. Another difference between the species is that Ler-0 had a slower rate of decline in the number of deletions of different sizes with increasing deletion length at indel sites, while Col-0 was similar to that seen in tomato (Fig. 4B).

Figure 3.

Characteristics of indels found within Indel Groups, from an IGGPIPE analysis of S. lycopersicum SL2.50/ITAG2.4/S. pennellii V2.0 (k = 14, AMIN = 100, AMAX = 3,000, and ADMIN = ADMAX = 100; A and C) and Arabidopsis accessions Col-0/Ler-0 (k = 13, other parameters are the same; B and D). A and B, Each Indel Group was plotted as a point, where the x axis is the predicted amplicon size difference and the y axis is the number of indels found in the Indel Group after aligning the two sequences. C and D, Similar plot but the y axis is indel size. The 45° line represents Indel Groups containing a single indel that is responsible for the amplicon size difference. Some points lie above the line because a single Indel Group can have deletions in both genomes at different places.

Figure 4.

Additional characteristics of indels found within Indel Groups, from the same analysis cited in Figure 3. A and C, S. lycopersicum SL2.50/ITAG2.4/S. pennellii V2.0. B and D, Arabidopsis accessions Col-0/Ler-0. A and B, The number of indels of different sizes decreases approximately exponentially as the indel length increases. C and D, Density of Indel Group indels within genomic features found in the LCRs containing the Indel Groups. Upstream is defined as within 1,000 bp 5′ of the 5′ UTR, and downstream is within 1,000 bp 3′ of the 3′ UTR of a gene, while intergenic is any position not falling into any of the other categories. CDS, Coding sequence.

Primer Creation

After Indel Groups are identified, IGGPIPE extracts DNA sequence around the pair of common unique k-mers defining each Indel Group and executes Primer3 (Untergasser et al., 2012) to design primers at each of the k-mers, using as Primer3 input the concatenation of the two short DNA sequences, one surrounding each of the two k-mers, omitting the intervening region, which varies between genomes.

In Silico PCR Testing

One of the final IGGPIPE steps is to run the in silico PCR program e-PCR (Schuler 1997) to test each primer pair, eliminating those not having the predicted amplicon sizes or amplifying at multiple loci. An alignment is shown in Figure 2C of a primer sequence, a common unique k-mer sequence, and k-mer and flanking DNA in the tomato and S. pennellii genomes.

IGGPIPE Marker Assessment Testing: Two-Genome Polymorphism Detection

We assessed the performance of IGG markers generated with IGGPIPE in a pairwise, two-genome fashion: first, using the intercrossable species S. lycopersicum and S. pennellii, and second, a within-species evaluation using Arabidopsis accessions Col-0 and Ler-0. Computer resource usage metrics are provided in Table III and Supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

Table III. Metrics for four separate runs of IGGPIPE on S. lycopersicum/S. pennellii genomes using four different values of k and three separate runs on Arabidopsis Col-0/Ler-0 accessions.

All other parameters besides k were unchanged. The metrics k, KMIN, DMIN, AMIN, AMAX, ADMIN, and ADMAX are all user-specified parameters. Three measurements of computer resource usage are provided: central processing unit (CPU) time, memory usage, and number of operating system waits, all gathered with the BSD time utility running on a system with an Intel 2.4-GHz Core 2 Duo CPU, 16-Gb DRAM, and Mac OSX 10.11.4. IGGPIPE memory requirements are modest (but increase with increasing k and increasing genome size), and CPU time increases dramatically with increasing k. For the genomes and parameters shown here, the IGGPIPE software can be run on a personal laptop computer.

| Metric | S. lycopersicum/S. pennellii | Arabidopsis Col-0/Ler-0 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| k | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| Minimum k-mers per LCR (KMIN) | 2 | Same | Same | Same | 4 | Same | Same |

| Minimum k-mer-to-k-mer distance in bp (DMIN) | 10 | Same | Same | Same | 15 | Same | Same |

| Minimum amplicon size (AMIN) | 250 | Same | Same | Same | 400 | Same | Same |

| Maximum amplicon size (AMAX) | 800 | Same | Same | Same | 1,500 | Same | Same |

| Minimum amplicon size difference at AMIN (ADMIN) | 100 | Same | Same | Same | 50 | Same | Same |

| Minimum amplicon size difference at AMAX (ADMAX) | 200 | Same | Same | Same | 300 | Same | Same |

| Genome sizes (No. of k-mers) | 824/990 Mb | Same | Same | Same | 120/118 Mb | Same | Same |

| Total CPU time (BSD time) | 13 min | 27 min | 113 min | 906 min | 6 min | 30 min | 136 min |

| Maximum memory usage (BSD time) | 1.5 Gb | 1.5 Gb | 2.4 Gb | 6.3 Gb | 0.37 Gb | 1.2 Gb | 3.2 Gb |

| Operating system waits (BSD time) | 24 | 180 | 4,204 | 11,357 | 104 | 928 | 5,418 |

| Unique k-mers | 0.18/0.14 M | 3.5/3.2 M | 25/24 M | 89/89 M | 0.70/0.71 M | 6.8/6.9 M | 27/27 M |

| Common unique k-mers | 43 K | 1.1 M | 8.9 M | 34 M | 563 K | 5.7 M | 23 M |

| LCRs | 330 | 42 K | 106 K | 122 K | 10.2 K | 7.6 K | 8.2 K |

| Overlapping Indel Groups | 0 | 835 | 31 K | 209 K | 2.3 K | 66 K | 150 K |

| Overlapping unvalidated IGG markers | 0 | 477 | 12 K | 35 K | 1.6 K | 28 K | 26 K |

| Overlapping e-PCR-validated IGG markers | 0 | 376 | 9,437 | 28,379 | 1,588 | 28,031 | 25,201 |

| Nonoverlapping e-PCR-validated IGG markers | 0 | 295 | 3,720 | 7,665 | 528 | 2,392 | 2,523 |

Assessment in S. lycopersicum and S. pennellii

We applied the IGG marker pipeline to the S. lycopersicum SL2.50/ITAG2.4 chromosome-based genome (Bombarely et al., 2011; Tomato Genome Consortium, 2012) and the new S. pennellii (intercrossable wild relative) V2.0 genome (Bolger et al., 2014). First, four different runs were performed with k varying from 12 to 15 and all other parameters remaining constant (Table III). From these runs, a k-mer size of k = 14 was chosen for further runs, using a balance between the number of IGG markers generated and the total computation time as selection criteria. Next, four more runs were performed, using different parameter settings for each, but all using k = 14 (Table II). The number of overlapping IGG markers generated ranged from 7,163 to 91,947, and the number of nonoverlapping markers ranged from 2,332 to 16,442. In the fourth run (400–1,500/50–300), the number of markers was largest at the minimum difference of 50 bp, decreasing in number up to the maximum possible difference of 1,100 bp (Fig. 5A). The marker density closely matches gene density (Fig. 5C). Markers in the Arabidopsis accessions Col-0 and Ler-0 show similar distribution (Fig. 5B) but a very different density across chromosomes (Fig. 5D). A random selection of 24 IGG markers (two per chromosome) was tested molecularly, and 21 (87.5%) were found to give a single amplicon of the predicted size in each of the two species (Table IV; Fig. 6). Four IGG markers were used to successfully genotype 28 F2 individuals at four loci (Supplemental Fig. S3). Markers cover all chromosomes, with greatest density in the less heterochromatic regions (Supplemental Figs. S4 and S5, A and B). The overlapping and nonoverlapping IGG marker files from all four of these runs are provided (Supplemental Data S1).

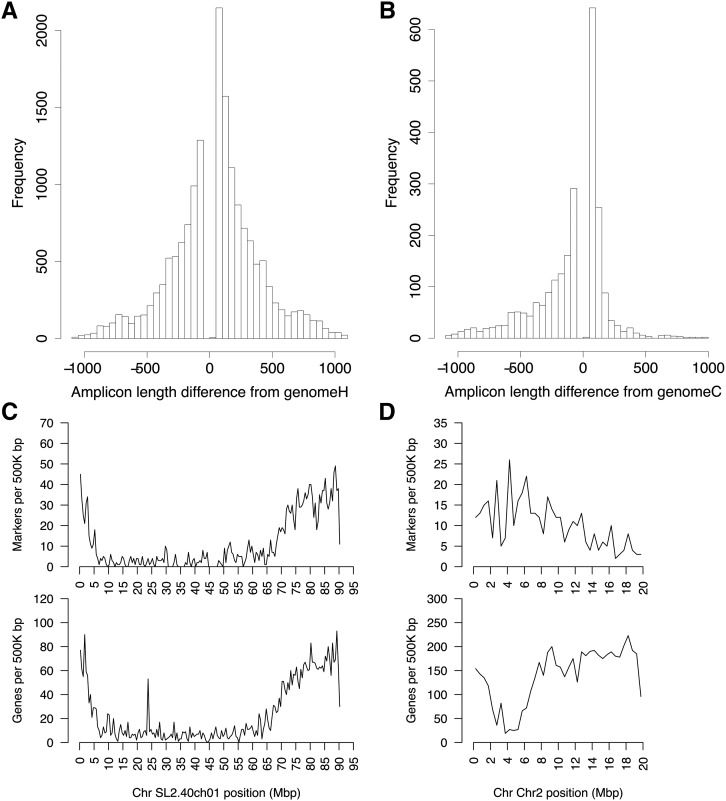

Figure 5.

A and B, Distribution of differences in IGG marker amplicon sizes between the two analyzed genomes, from an IGGPIPE analysis of S. lycopersicum SL2.50/ITAG2.4/S. pennellii V2.0 (k = 14, AMIN = 400, AMAX = 1,500, ADMIN = 50, and ADMAX = 300; A) and Arabidopsis accessions Col-0/Ler-0 (k = 13, other parameters are the same; B). A positive difference means that the S. lycopersicum or Col-0 amplicon is the larger, and a negative difference means that the S. pennellii or Ler-0 amplicon is the larger. C and D, Density of IGG markers (top graphs) and genes (bottom graphs) along a representative chromosome, from the same analysis as above. C, Chromosome 1 of S. lycopersicum. Note the positive correlation. D, Chromosome 2 of Arabidopsis Col-0 accession.

Table IV. IGG markers tested in S. lycopersicum and S. pennellii.

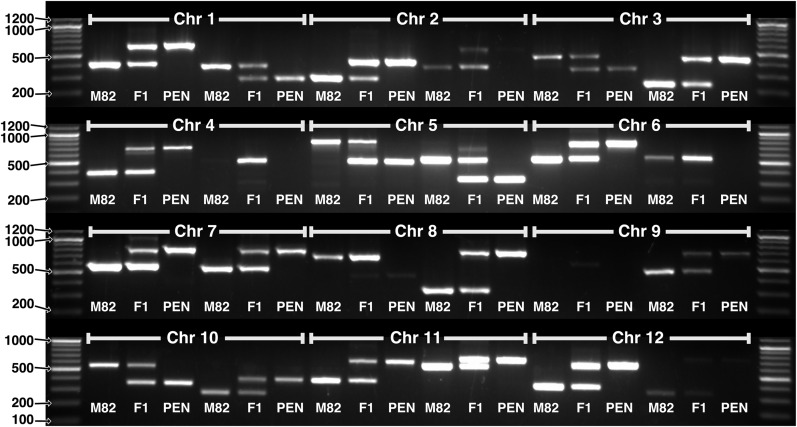

PCR gel results are shown in Figure 6. Out of 24 markers tested, 21 (87.5%) amplified with the predicted amplicon sizes in both species, two failed to amplify in either species, and one did not amplify in S. pennellii.

| No. | IGG IDa | Chrb | Expected Sizec |

Dif Sized | Bandse |

Correct Sizef |

Codomg | Primer Forward (5′–3′) | Primer Reverse (5′–3′) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M82 | PENN | M82/PENN | M82/PENN | |||||||

| 1 | IGG_HP14B_179 | 1 | 405 | 616 | −211 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | GACACTCAGCCTAAGTTGCAG | TACACTGAGGCATCGTCTCC |

| 2 | IGG_HP14A_882 | 1 | 377 | 275 | 102 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | CCTACCTGGGACTCAATCTGT | TCAGTGTATAAGCTTGACCTCCA |

| 3 | IGG_HP14B_1342 | 2 | 281 | 419 | 138 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | ATTATCAGCTCCCAGACCCC | TGAGGATGCTTCATATCGCC |

| 4 | IGG_HP14B_2155 | 2 | 371 | 554 | 183 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | AAGCAGTGGTCGGTGATCAG | CGTTCCACATGACTATCGGAC |

| 5 | IGG_HP14B_2564 | 3 | 467 | 346 | −121 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | TAAAGCTTCCGAGGCCTATG | TTTCACCCTCGTCGAGTCTC |

| 6 | IGG_HP14A_7145 | 3 | 234 | 442 | −208 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | TCGGGTCTGTTCTACTGCTT | CCTCCTGGTGTGTATGGGAG |

| 7 | IGG_HP14B_3418 | 4 | 389 | 681 | 292 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | TTATGCACGTCTCCTCAAGG | GAGAGGTTCTTGGTGGATGAC |

| 8 | IGG_HP14B_3934 | 4 | 495 | 749 | 254 | 0/0 | No/no | No | CGTCCCTTTGTCACGTGTC | GGAGCGTAAATTTGAGCTACTTG |

| 9 | IGG_HP14B_4268 | 5 | 799 | 489 | −310 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | CCCCTAAAGATCTGCTCGAAATC | TGACCACGTTTCCCTTCTAATG |

| 10 | IGG_HP14B_4544 | 5 | 527 | 325 | −202 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | CCTCTGGCAATCTTCAGGTG | TCCTGCCTATTTTGCTTGCTG |

| 11 | IGG_HP14B_4721 | 6 | 531 | 767 | 236 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | ACCAGAGAGAACCCTTGATCC | GCTCTTTCAACTTTGCCTGTG |

| 12 | IGG_HP14B_5488 | 6 | 543 | 741 | 198 | 1/0 | Yes/no | No | TCATAATGGCCAGAAACCCG | CACGCAACAATCAACATTTAGGG |

| 13 | IGG_HP14B_6105 | 7 | 523 | 753 | −230 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | GGCTACCAGTCCTGTCGAG | TTTCGCGCTGATGAACACC |

| 14 | IGG_HP14C_4527 | 7 | 558 | 783 | −225 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | GACAGTGGCGGAGTGAGATA | AAGTACGCTATGGTTCGGGG |

| 15 | IGG_HP14B_6403 | 8 | 670 | 448 | −222 | 1/1 faint | Yes/yes | Yes | AACAACCAGTCAATAAGCTGC | TCAAGGAATCAACTGTGCCTC |

| 16 | IGG_HP14A_15764 | 8 | 329 | 720 | −391 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | AATCTTGATGAGTGTCCGCG | GCACAAAGCGGGTCTAGAAA |

| 17 | IGG_HP14B_7175 | 9 | 790 | 563 | −227 | 0/0 | No/no | No | GACACAGCTGTTAATTGGACATC | CAAAGAAGATGCACGTGGAAC |

| 18 | IGG_HP14A_16708 | 9 | 491 | 697 | −206 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | GTTTGATCCTGCGCACACC | CCAGTTAACAGAGGTAAAAGCCA |

| 19 | IGG_HP14A_17903 | 10 | 555 | 357 | 198 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | ACATTCACACAAACCGCACA | TGTAGCGCTGGTAATGCTTA |

| 20 | IGG_HP14A_18108 | 10 | 282 | 411 | −129 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | ACCGAACTAGCCAGACCAAA | TTTTGCTTTGGTGCTCGTCA |

| 21 | IGG_HP14B_8438 | 11 | 406 | 650 | 244 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | TCATCAGCTTGTTGGGTATGTG | GACGGTGGAGTTGTGATATGG |

| 22 | IGG_HP14A_20373 | 11 | 600 | 703 | −103 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | CGCTTGCCTTCTTCGTTAGA | GACCACGATTCTGCTTTGGT |

| 23 | IGG_HP14B_9081 | 12 | 377 | 646 | −269 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | ACCCTAAGCTGCTGTAGTGC | AACCCGCAGCCTTCAAAAC |

| 24 | IGG_HP14B_9341 | 12 | 331 | 723 | 392 | Faint | Yes/yes | Yes | TCTACAAGCATGCGATCAAGTC | TCAACAAGGAGGCTTTAACCC |

IGGPIPE spreadsheet identifier number for the IGG marker.

Chromosome number.

Expected amplicon sizes in cv M82 (S. lycopersicum) and PENN (S. pennellii).

Expected difference in size of the amplicons.

Number of bands observed for cv M82 and PENN.

Was the observed band size the predicted size?

Was the marker codominant (different amplicon size in both species)?

Figure 6.

Twenty-four IGG markers, two per chromosome at locations within the first or last 15% of each chromosome, were chosen randomly from three different IGGPIPE runs using different sets of parameters and all analyzing the S. lycopersicum (SL2.50/ITAG2.4 pseudomolecules) and S. pennellii (V2.0 pseudomolecules) genomes. In 21 of the 24 markers (87.5%) amplifying S. lycopersicum cv M82, S. pennellii (PEN), and F1 DNA, two bands of the expected amplicon sizes are seen (Table IV), one in each species. In two cases, no band is seen in either species, and in another case, only an S. lycopersicum band is seen.

Assessment in Arabidopsis Accessions Col-0 and Ler-0

Length polymorphisms between Ler-0 and Col-0 accessions can be identified using The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) Search Polymorphisms/Alleles tool at Arabidopsis.org (Lamesch et al., 2012; TAIR, 2015). Unfortunately, many of these markers only allow identification of the presence of a PCR fragment in one accession versus its absence in the other. In those markers where there is a PCR fragment length polymorphism, the size difference is very small. Table V shows the best available polymorphisms found (two per chromosome) for maximum product separation within several hundred markers. All markers have a very small (mean of 37 bp) difference in size.

Table V. Length polymorphism markers for Arabidopsis accessions Col-0 and Ler-0, found with the Polymorphism/Allele search tool at Arabidopsis.org.

| Chra | Polymorphism Name | Col-0 Ab | Ler-0 Ac | Difference in Sized | Primer Forward (5′–3′) | Primer Reverse (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | nga111 | 128 | 162 | 34 | TGTTTTTTAGGACAAATGGCG | CTCCAGTTGGAAGCTAAAGGG |

| 1 | F16J7-TRB | 165 | 114 | 51 | TGATGTTGAGATCTGTGTGCAG | GTGTCTTGATACGCGTCGAT |

| 2 | nga168 | 150 | 135 | 15 | GAGGACATGTATAGGAGCCTCG | TCGTCTACTGCACTGCCG |

| 2 | ciw3 | 230 | 200 | 30 | GAAACTCAATGAAATCCACTT | TGAACTTGTTGTGAGCTTTGA |

| 3 | ciw11 | 180 | 230 | 50 | CCCCGAGTTGAGGTATT | GAAGAAATTCCTAAAGCATTC |

| 3 | nga172 | 162 | 136 | 26 | CATCCGAATGCCATTGTTC | AGCTGCTTCCTTATAGCGTCC |

| 4 | JV30/31 | 195 | 165 | 30 | CATTAAAATCACCGCCAAAAA | TTTTGTTACATCGAACCACACA |

| 4 | nga8 | 154 | 198 | 44 | TGGCTTTCGTTTATAAACATCC | GAGGGCAAATCTTTATTTCGG |

| 5 | ciw8 | 100 | 135 | 35 | TAGTGAAACCTTTCTCAGAT | TTATGTTTTCTTCAATCAGTT |

| 5 | ciw15 | 177 | 120 | 57 | TCCAAAGCTAAATCGCTAT | CTCCGTCTATTCAAGATGC |

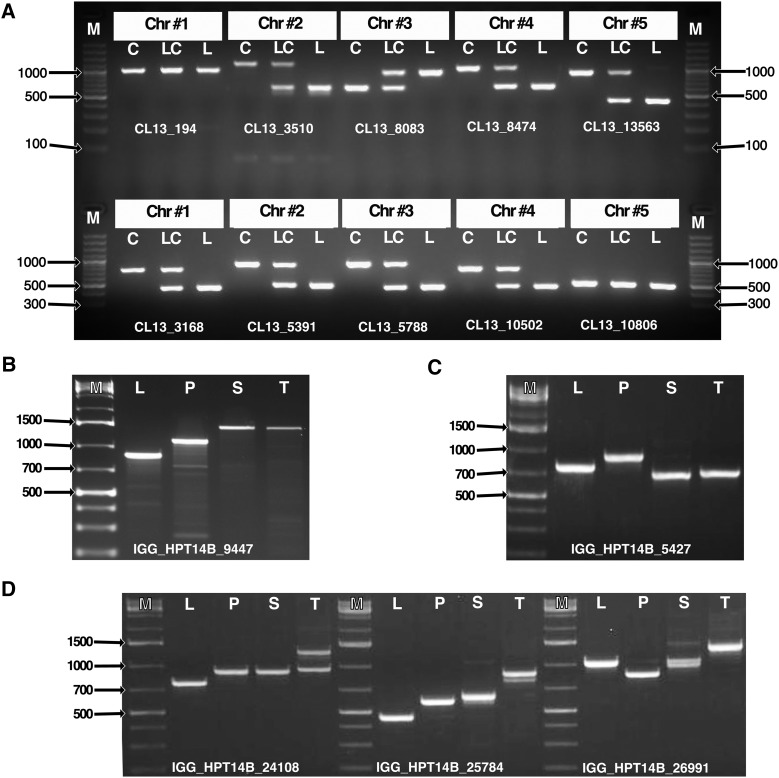

We applied the IGG marker pipeline to the Arabidopsis Col-0 accession TAIR 10 genome (Lamesch et al., 2012) and the Arabidopsis Ler-0 accession V0.7 genome (Gan et al., 2011). Parameter settings included k = 13, amplicon size of 400 to 1,500 bp, and a minimum difference in size between amplicons of 50 to 300 bp. Relative to the interspecies marker run, we predicted that the number of polymorphisms between the two Arabidopsis accessions would be much smaller. However, this marker set contains 28,031 overlapping and 2,072 nonoverlapping IGG markers all confirmed with e-PCR (Table VI; Supplemental Fig. S5, C and D). Ten of these markers were tested experimentally, and eight (80%) had the expected amplicon sizes in the two accessions (Table VII; Fig. 7A). These markers had larger size differences, and differences between the accessions were easier to distinguish compared with the TAIR search polymorphisms/alleles markers in Table V. The entire marker set is provided (Supplemental Data S2).

Table VI. Parameters and statistics for the IGGPIPE run using Arabidopsis accessions Col-0 and Ler-0.

The IGG markers from this run are provided (Supplemental Data S2). The metrics k, KMIN, DMIN, AMIN, AMAX, ADMIN, and ADMAX are all user-specified parameters.

| Metric | Arabidopsis Col-0/Ler-0 |

|---|---|

| Marker identifier prefix (ID_PREFIX) | IGG_CL13_ |

| k | 13 |

| Minimum No. of k-mers per LCR (KMIN) | 10 |

| Minimum LCR k-mer spacing in bp (DMIN) | 30 |

| Minimum amplicon size (AMIN) | 400 |

| Maximum amplicon size (AMAX) | 1,500 |

| Minimum amplicon size difference at AMIN (ADMIN) | 50 |

| Minimum amplicon size difference at AMAX (ADMAX) | 300 |

| Genome size (No. of k-mers) | 120/118 Mb |

| Unique k-mers | 6.8/6.9 M |

| Common unique k-mers | 5.7 M |

| LCRs | 6.2 K |

| Overlapping Indel Groups | 34 K |

| Overlapping unvalidated IGG markers | 14 K |

| Overlapping e-PCR-validated IGG markers | 14 K |

| Nonoverlapping e-PCR-validated IGG markers | 2,072 |

Table VII. IGG markers tested in Arabidopsis accessions Col-0 and Ler-0.

PCR gel results are shown in Figure 7A. Out of 10 markers tested, eight (80%) amplified with the predicted amplicon sizes in both species.

| No. | IGG IDa | Chrb | Expected Sizec |

Dif Sized | Bandse |

Correct Sizef |

Codomg | Primer Forward (5′–3′) | Primer Reverse (5′–3′) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Col-0 | Ler-0 | Col-0/Ler-0 | Col-0/Ler-0 | |||||||

| 1 | IGG_CL13_194 | 1 | 1,033 | 556 | 477 | 1/1 | Yes/no | No | GGGTCAATCATCGGTGTTTTG | TGCATGCCTCTGTTCAACTG |

| 2 | IGG_CL13_3510 | 2 | 1,282 | 655 | 627 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | TTCATCCGACTCAATTGGCG | TCGTTTATTCAGGACAGCTGC |

| 3 | IGG_CL13_8083 | 3 | 643 | 997 | 354 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | AAGAGACAGAGACGGGTTGC | CGTTGACTGAAGCTCAAGGG |

| 4 | IGG_CL13_8474 | 4 | 1,119 | 652 | 467 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | GTAGAATCAGCGAACAATGTAGC | TCAAAACAACAAAATAAGGCCGG |

| 5 | IGG_CL13_13563 | 5 | 956 | 445 | 511 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | GTCGATTAGGTCAACGGCTG | GGTTTGACCCCTTTGCATCG |

| 6 | IGG_CL13_3168 | 1 | 765 | 450 | 315 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | TCTCTTTCGTGGACAGAGCC | TCGCACTTCAATTTCAGACCG |

| 7 | IGG_CL13_5391 | 2 | 883 | 492 | 391 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | GTCAGTAAATTAACACACGTCCG | CGACTGAAAGATGTTGAAATGGG |

| 8 | IGG_CL13_5788 | 3 | 897 | 457 | 440 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | CATCCAGACATAAACATCATGCG | GAGAAGGCACAGCAGACAAG |

| 9 | IGG_CL13_10502 | 4 | 762 | 466 | 296 | 1/1 | Yes/yes | Yes | AATGGATTCCTGCGACGGAG | TCTTCGGATCAGAGCCAAGC |

| 10 | IGG_CL13_10806 | 5 | 507 | 908 | 401 | 1/1 | Yes/no | No | GTCGATTAGGTCAACGGCTG | GGTTTGACCCCTTTGCATCG |

IGGPIPE spreadsheet identifier number for the IGG marker.

Chromosome number.

Expected difference in size of the amplicons.

Was the observed band size the predicted size?

Was the marker codominant (different amplicon size in both accessions)?

Figure 7.

Gel electrophoresis of PCR products of several candidate IGG markers from two IGGPIPE runs. A, Testing primers generated against Arabidopsis accessions Ler-0 and Col-0. PCR product was resolved on 2% gels. M, BioLabs QuickLoad 100-bp ladder; C, Col-0; LC, Ler-0/Col-0 hybrid; and L, Ler-0. Eight of 10 show expected product sizes (Table VII). B to D, PCR products by gel electrophoresis using IGG markers from a triallelic marker run with S. lycopersicum, S. pennellii, and S. tuberosum genomes. M, O’GeneRuler 1Kb Plus ladder; L, S. lycopersicum; P, S. pennellii; S, S. sitiens; and T, S. tuberosum. B, IGG marker B_9447 shows three-way polymorphism between the three genomes of interest, and amplicons are of predicted size (Table IX). In addition, S. tuberosum and S. sitiens share the same allele. C, Marker B_5427 also shows three-way polymorphism between the three genomes of interest. In this case, the S. tuberosum amplicon is closer to 700 bp than the predicted 527 bp. S. lycopersicum and S. pennellii have predicted amplicon sizes. In addition, S. tuberosum and S. sitiens have a very small or zero size difference. D, Markers B_24108, B_25784, and B_26991 also indicate three-way polymorphism between S. lycopersicum, S. pennellii, and S. tuberosum. However, S. sitiens shares an allele with either S. pennellii (B_24108) or S. lycopersicum (B_26991). The presence of multiple bands is observed for select genotypes.

IGGPIPE Marker Assessment Testing: Three-Genome Polymorphism Detection

S. lycopersicum × S. sitiens Introgression Line Development Using IGG Markers

Cultivated tomato (S. lycopersicum) is an economically important crop, but genetic diversity for key agronomic traits needed for growth in a changing climate, such as abiotic stress tolerance, is lacking in the widely used inbred germplasm. Wild relatives such as S. sitiens, endemic to the Atacama Desert of Chile, are of interest because of adaptation to minimal rainfall, cold temperatures, and high soil salinity. Utilization of this genetic variation for breeding purposes can be facilitated by the development of an introgression line population of S. sitiens in the background of cultivated tomato. No reference genome sequence is available for S. sitiens, and the majority of genomic markers available are SNPs (Sim et al., 2012; SolCAP Solanaceae Coordinated Agricultural Project, 2015). Here, we describe how we utilized the IGG pipeline to identify polymorphisms between three genomes that can be useful in cases where populations are developed between species with varying levels of self-incompatibility or where one parent’s genome is unsequenced but a closely related sequenced genome exists.

Prezygotic and postzygotic hybrid incompatibility between cultivated tomato and S. sitiens has made introgression line development a challenge (DeVerna et al., 1990; Pertuzé et al., 2002, 2003; Peters et al., 2012). To aid in the production of S. lycopersicum and S. sitiens hybrids, an interspecific bridging line, F1 S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii, was employed. Hybrids of [S. lycopersicum × S. sitiens] × [S. lycopersicum × S. pennellii] were backcrossed to cultivated tomato. While the majority of the S. sitiens genome was transferred as determined using CAPS markers, repeated backcrossing was needed to eliminate residual background noise and to retain individual introgressed segments. We ran IGGPIPE with three genomes (tomato, S. pennellii, and potato) to develop triallelic markers to genotype these crosses. The S. tuberosum (potato) sequence was used as a stand-in for the unsequenced S. sitiens genome, as the two species share the same chromosomal configuration (Pertuzé et al., 2002; Peters et al., 2012).

The three-genome IGGPIPE analysis used the S. lycopersicum SL2.50/ITAG2.4 (Heinz) genome (Bombarely et al., 2011; Tomato Genome Consortium, 2012), the S. pennellii V1.0 genome (Bolger et al., 2014), and the S. tuberosum (potato) Phureja group clone DM1-3 V4.03 genome (Xu et al., 2011) with parameter settings including k = 14, an amplicon size of 400 to 1,500 bp, and a minimum difference in size between amplicons of 50 to 300 bp. A total of 951 overlapping (278 nonoverlapping) IGG markers were generated that were predicted to display three-way polymorphism between S. lycopersicum, S. pennellii, and S. tuberosum (Table VIII; Supplemental Fig. S6). Of these, 32 markers were selected for further characterization and tested on DNA from the parents of our introgression line population (S. lycopersicum, S. pennellii, and S. sitiens) and S. tuberosum. We found that all 32 amplified in cultivated tomato and S. pennellii, 30 in S. tuberosum, and 28 in S. sitiens, with an annealing temperature of 55°C (success rate of approximately 88%–94%; Table IX). The genetic difference between potato and S. sitiens could explain this result (Pertuzé et al., 2002; Peters et al., 2012). We found that 30 (93.8%) of these 32 markers were triallelic relative to potato, displaying scoreable band differences between cultivated tomato, S. pennellii, and S. tuberosum (Table IX). Some nonspecific amplification was observed for all species tested. For example, of the 28 amplicons from cultivated tomato, four primer pairs yielded two or more bands (Fig. 7B). However, the intensity of these products was considerably lower and overall did not affect parent identification.

Table VIII. Parameters and statistics for two runs, designated A and B, of IGGPIPE using a three-way genome analysis of S. lycopersicum (tomato), S. pennellii, and S. tuberosum (potato).

The introgression line development and three-allele marker testing using S. sitiens, described in the text, used the run B markers. The two runs use a different marker identifier prefix to distinguish the markers. The IGG markers from these runs are provided (Supplemental Data S1). The metrics k, KMIN, DMIN, AMIN, AMAX, ADMIN, and ADMAX are all user-specified parameters.

| Metric | S. lycopersicum/S. pennellii/S. tuberosum Run 1 (A) | S. lycopersicum/S. pennellii/S. tuberosum Run 2 (B) |

|---|---|---|

| Marker identifier prefix (ID_PREFIX) | IGG_HPT14A_ | IGG_HPT14B_ |

| Genome 1 | S. lycopersicum ITAG2.4 | Same |

| Genome 2 | S. pennellii V2.0 | S. pennellii V1.0 |

| Genome 3 | S. tuberosum DM V4.03 | Same |

| k | 14 | 14 |

| Minimum No. of k-mers per LCR (KMIN) | 2 | 4 |

| Minimum LCR k-mer spacing in bp (DMIN) | 5 | 1 |

| Minimum amplicon size (AMIN) | 300 | 400 |

| Maximum amplicon size (AMAX) | 1,500 | 1,500 |

| Minimum amplicon size difference at AMIN (ADMIN) | 50 | 50 |

| Minimum amplicon size difference at AMAX (ADMAX) | 300 | 300 |

| Maximum base pair beyond which k-mer primer extends (EXTENSION_LEN) | 15 | 10 |

| Primer GC clamp | Yes | No |

| Genome sizes (No. of k-mers) | 120/118 Mb | 120/118 Mb |

| Unique k-mers | 24.7/23.9 M | 24.7/23.9 M |

| Common unique k-mers (all three genomes) | 2.8 M | 2.8 M |

| LCRs | 27.9 K | 24.6 K |

| Overlapping Indel Groups | 61 K | 240 K |

| Overlapping unvalidated IGG markers | 18 K | 29 K |

| Overlapping e-PCR-validated IGG markers | 18.2 K | 29.5 K |

| Two distinct alleles (two genomes have same size alleles) | 17,665 | 28,505 |

| Three distinct alleles | 534 | 951 |

| Nonoverlapping e-PCR-validated IGG markers | 5,203 | 5,549 |

| Two distinct alleles (two genomes have same size alleles) | 4,975 | 5,271 |

| Three distinct alleles | 228 | 278 |

Table IX. PCR testing of IGG markers for three-way genome analysis.

A set of 32 IGG markers were selected for PCR testing. DNA from S. lycopersicum (L), S. pennellii (P), S. tuberosum (T), and S. sitiens (S) was amplified and polymorphism was scored. PCR gel results are shown in Figure 7, B to D. N/A, Comparison could not be made because one or more genotypes did not amplify under the conditions tested; No, base pair difference was not easily identified; Yes, base pair difference (on 2% agarose gels) between genotypes was easily identified. *, Did not amplify in S. sitiens.

| Markera | IGG IDb | Polymorphism Type |

Amplicon Sizee |

Primer Forward (5′–3′) | Primer Reverse (5′–3′) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Wayc |

Three-Wayd |

|||||||||||||

| L versus P | L versus T | P versus T | L versus S | P versus S | T = S | LPT | LPS | L | P | T | ||||

| M-1 | IGG_HPT14B_754 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | 991 | 737 | 584 | AGAGAACTTAGTGCAGGCAG | TGCTCTGGGTCTCCTAGTTC |

| M-2* | IGG_HPT14B_926 | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | 1,247 | 1,519 | 765 | TCACAATCATCACGGAGCAAC | ACCACAGCTTCTACGCCTTA |

| M-3 | IGG_HPT14B_1105 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 1,103 | 809 | 682 | TGAAACACGAAAGGAGCTTGT | AGCCGTTCATCAGCAATCAA |

| M-4 | IGG_HPT14B_1608 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | 1,093 | 1,508 | 725 | TACTCGCTCTTCATGACGCT | CTAATTCGCAGCAAATCGAAAC |

| M-5 | IGG_HPT14B_4592 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 943 | 1,121 | 751 | ATTGCATACCCACTGCGAGG | CAGGCGGATGTGTGAGTTAT |

| M-6 | IGG_HPT14B_4936 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 1,327 | 582 | 671 | AAGAGAGGCATTCGAGGGAG | CATGCGCCACGTGTACTC |

| M-7 | IGG_HPT14B_5427 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 792 | 932 | 527 | TGTTGAGGGCTGGTGGATAC | CTGTAGCAGGCTCATCTTAAAAC |

| M-8 | IGG_HPT14B_6347 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 969 | 1,196 | 1,449 | CTCATGGCCACGAATGTCTG | GGTGGTGGCAGTAACGTTTC |

| M-9 | IGG_HPT14B_8121 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 824 | 1,150 | 1,366 | AGAGCCGCCTTTCCTCCTA | TTTCAAGCTGGCATTCGAGC |

| M-10* | IGG_HPT14B_8235 | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | 1,056 | 649 | 885 | TTACCACGTTCTCCAGCAGG | CTCATGAAAACCTCCGACCTG |

| M-11 | IGG_HPT14B_8264 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 898 | 1,097 | 1,358 | GCCGCTACTTCTCGATCAAA | TTGTTCAGGTGCCTCGTG |

| M-12 | IGG_HPT14B_8563 | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | 651 | 430 | 913 | AAAAGGAAGCGCGAGATGAG | CCAGTGGAGCAGGTTACTC |

| M-13* | IGG_HPT14B_8811 | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | 579 | 1,012 | 815 | CAAGGATCTGGCTGGGTAGT | GGTACCCTTGCTCGATTAGATAG |

| M-14 | IGG_HPT14B_8853 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 841 | 1,247 | 1,051 | TCCAACTCCGGACAAAGGT | TCTCACGGTATAAGCAGAGCA |

| M-15 | IGG_HPT14B_9447 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 875 | 1,111 | 1,368 | AGGGCACGTACCAGCATAAA | ATGATGGGATGCTGTCGACA |

| M-16 | IGG_HPT14B_10635 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 963 | 786 | 615 | TAAGCTGTAACGCAATCCCG | CCCTGTGGAGCCAACAAT |

| M-17* | IGG_HPT14B_11038 | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | 1,371 | 1,120 | 907 | TGACAGTTCAAGCCCACAG | GTGAACACTCCCTGACTTTGT |

| M-18 | IGG_HPT14B_15532 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 1,425 | 1,148 | 611 | TTATCTTGCTGTGCTTGCCC | CAAGTTTATGGGGTGGCACA |

| M-19 | IGG_HPT14B_15683 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 464 | 528 | 846 | CGTTTGATGGTTGGTGCGTA | TAGTCTACGCGGCGCATC |

| M-20 | IGG_HPT14B_15777 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | 877 | 718 | 1,225 | GGCACTTGTGAGCAGTATCC | TGCAAGTCGACAGTATCTAACA |

| M-21 | IGG_HPT14B_21272 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 469 | 554 | 899 | GGGATCTTCGCACCTAAATCC | ATTCCGACTGCCTGGTGTTT |

| M-22 | IGG_HPT14B_21501 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | 1,290 | 983 | 765 | CTTCCCTCATCTCGTCGGG | AATGCGTGCAGAAGAAGACG |

| M-23 | IGG_HPT14B_23704 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,034 | 783 | 1,406 | GCGGCGGATTGGGAAATC | CGGCGAGTAGGAGAACTGAG |

| M-24 | IGG_HPT14B_24108 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | 779 | 933 | 1,504 | GCTTATGCGGGTTTGTTAGAAA | CGGTATAACTTCACGGCATTAAG |

| M-25 | IGG_HPT14B_25784 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 463 | 590 | 902 | GCATCTTCTCAACGTACCTCTC | CCAGTTTTACCACCTAAACCGG |

| M-26 | IGG_HPT14B_26897 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 1,393 | 1,104 | 897 | TGTCACCAGCATACTTTGTCA | ACTGATAACTGGGTGAAAGGTG |

| M-27 | IGG_HPT14B_26991 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | 1,051 | 866 | 1,333 | CTGGAAGCAGCAGGTATTCT | GCTCGGATTGCATTCACTTG |

| M-28 | IGG_HPT14B_27175 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 863 | 1,050 | 728 | AGGAGAAGACTGGCGGAAAG | TGGAAAGCACAGAAACAGATGA |

| M-29 | IGG_HPT14B_27897 | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | 972 | 480 | 1,339 | AAGTGCTGGCGTAAATTCAC | AGTGTGTTTGTGAGTGAAGCA |

| M-30 | IGG_HPT14B_28355 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 1,469 | 1,148 | 964 | TGGACCCCTATTGACTTAGTTGT | GTAGGGAGGGGCACATAACC |

| M-31 | IGG_HPT14B_28659 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | 1,234 | 1,026 | 758 | TGGTTGCCTTGGCTTAGAAG | TGAACCACTCAACGCGGG |

| M-32 | IGG_HPT14B_29367 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | 830 | 1,207 | 1,011 | CCTGAATCCCTGAGAATCCCA | AACACTGTTTAGAAGCCGGT |

Marker number used in PCR experiments.

IGGPIPE spreadsheet identifier number for the IGG marker.

Two-way markers have two distinct amplicon sizes in two species.

Three-way markers have three distinct sizes in three species.

Predicted amplicon sizes. S. sitiens has no predicted size due to the absence of a reference genome.

Potato Is a Good Predictor of the Presence of Indels in S. sitiens But Not of Product Size

To determine whether novel S. sitiens markers could be used in introgression line characterization, the 28 S. sitiens primer pairs were scored by whether they displayed two-way polymorphism (S. pennellii and S. sitiens shared allele) or three-way polymorphism (no shared alleles between tomato versus S. pennellii versus S. sitiens), and 20 out of 28 (71.4%) appeared polymorphic between the three parents (e.g. IGG15; Fig. 7C; Table IX). Next, we wanted to test whether S. sitiens and S. tuberosum shared the same allele sizes. We found that only seven markers had a shared allele size with S. sitiens (e.g. IGG15 [Fig. 7C; Table IX] and IGG25784 [Fig. 7D]).

Taken together, these results indicate that it is possible to identify polymorphisms in S. sitiens using potato as a genome reference. Having even a rough de novo S. sitiens genome assembly would likely improve marker success. While our observed failure rate is not ideal for marker design, and far below that observed between S. lycopersicum and S. pennellii, it is quite close to the failure rate of other marker design studies such as those observed for single-copy orthologous genes (Wu et al., 2006), and IGG markers are substantially easier to use than existing CAPS markers. Two sets of IGG markers used in this project are provided (Supplemental Data S3).

Comparative Assessment of IGGPIPE against Other Marker Software

We compared the features and performance of IGGPIPE with two other marker creation tools, IMDP (Lü et al., 2015) and PolyMarker (Ramirez-Gonzalez et al., 2015), that also process whole-genome data in silico (Table X). Markers are discovered by IGGPIPE and IMDP, whereas PolyMarker requires SNPs as input and generates primers. IGGPIPE differs from these algorithms in that it can generate IGG markers having much larger amplicon sizes and size differences, allowing the use of a 1% agarose gel assay instead of higher percentage gels or polyacrylamide gels. IGGPIPE generated 1 order of magnitude more markers with primers in a pair of test species that included tomato than IMDP did using rice cultivars as a test species, while PolyMarker’s SNP marker primers using polyploid wheat (Triticum aestivum) as a test species were similar in number to IGGPIPE, but no PCR testing was done and the majority generated amplicons with size differences of a few base pairs or less. IGGPIPE has a distinct advantage relative to these tools as it allows the user to generate multiallelic markers enabling differentiation between two or more genomes.

Table X. Feature and performance comparison of IGGPIPE and two other in silico marker creation packages, IMDP and PolyMarker.

N/A, Not applicable.

| Feature/Item | IGGPIPE | IMDP | PolyMarker |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | This article | Lü et al. (2015) | Ramirez-Gonzalez et al. (2015) |

| Polymorphism type | Indel groups | Small indels | Small indels |

| Assay method | PCR and agarose 1% gel | PCR and polyacrylamide gel | Kompetitive allele-specific PCR proprietary method and PCR with polyacrylamide gel |

| Codominant | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Multiple alleles detectable? | Yes, can force discovery of multiallelic-only markers | Yes | Yes |

| Input | Two genome sequences | Genome sequences or NGS resequencing data | Reference genome and known SNPs |

| Output | File of IGG markers with positions and primer sequences | Indel markers with primers | Primers for SNP markers |

| Sample run species | S. lycopersicum/S. pennellii | Rice japonica/indica varieties | Polyploid wheat |

| No. of markers from sample run | 87,351 overlapping,16,548 nonoverlapping | 1,042 | 81,587 |

| Mean amplicon size (bp) | 745 (parameters = 400 to 1,500; of nonoverlapping markers) | 159 (of 95 tested markers) | None given, 100 bp mentioned in text |

| Mean amplicon size difference (bp) | 284 (parameters = 50 to 300; of nonoverlapping markers) | 15 (of 95 tested markers) | None given |

| No. of markers tested | 55 (tentative) | 95 | 35 |

| No. of markers work as predicted | 48 (87%; tentative) | 93 (multiple cultivars; 98%) | 28 |

| No. of cultivars tested at one time | 3 | 12 | 38 |

| Open access | Open access | Yes | Yes |

| Platform | Unix-based, tested on OSX | Linux (tested on Ubuntu 64) | BioGem |

| Operating environment | Command line | LONI pipeline processing environment, graphical | Web interface |

| External tools used | Jellyfish, Primer3, e-PCR | MUMmer3, Pindel, Primer3, MFEprimer2, LONI, BWA, samtools, FastQC, QualiMap, Trimmomatic, LAMP (Linux, Apache, MySQL, PHP), LastZ | Primer3, MySQL |

| Language environments used | C++, R, Perl, bash | R, Perl, bash | BioGem, bioruby, Java |

| Installation | Command line installation, install and run guides provided | LONI installation | Install private Web server |

| Additional data provided | Tomato/S. pennellii IGG marker files, Arabidopsis Col-0/Ler-0 IGG marker files | Rice indel marker database on the Web | None |

| Additional utilities provided | Dot plot of markers; convert between tsv, csv, gff3, gtf; merge data between two files based on genomic position overlap/proximity | N/A | N/A |

IGGPIPE is operated from the command line with manually edited user configuration files, whereas IMDP uses a user-friendly graphical tool, LONI (Dinov et al., 2009), and PolyMarker has a user-friendly Web interface. IGGPIPE includes a set of IGG markers in tomato/S. pennellii and Arabidopsis Col-0/Ler-0, and IMDP includes a rice marker public Web-based database (the Rice Indel Marker Database) as part of its release. IGGPIPE includes a utility for annotating markers with information from other genome sources that overlap the markers and can generate files suitable for custom genome browser tracks.

In Silico Marker Identification Using IGGPIPE

IGGPIPE is available as an open-source command line pipeline run via a Mac OSX, Linux-compatible, or Windows/Cygwin terminal interface. It is run from the command line using a make utility and includes detailed installation and run instructions. The only input required to run the pipeline is a FASTA file for each genome to be analyzed. IGGPIPE is available in open source form in the BradyLab/IGGPIPE GitHub (GitHub, 2015) repository at https://github.com/BradyLab/IGGPIPE.

DISCUSSION

IGG markers are similar to common indel markers in that they use a pair of PCR primers binding to regions flanking single-copy sites, but they differ in that the amplified region may be larger and may encompass multiple indels whose lengths may range up to 1,500 bp or more. Testing pairs of known unique primers for amplicon size differences is done within other indel marker programs (Liu et al., 2015; Lü et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2015), but it is normally limited to very short distances and single indel spans. The actual limits on amplicon sizes and size differences are parameters specified when IGGPIPE is run to generate the markers, providing user flexibility while also allowing length limits like those of traditional indel markers to be obtained when desired. IGG markers are of interest because they are built around an abundant source of polymorphism (indels ranging from a few base pairs to several hundred in size), can be scored easily, and have potential for multiallelism. The number of markers found using IGGPIPE depends not only on the degree of polymorphism between the genomes but also on the setting of search parameters, which include minimum and maximum amplicon sizes and minimum difference in their sizes between genotypes. Settings can be optimized to speed post-PCR gel electrophoresis by permitting the use of rapidly prepared 1% agarose gels with easily scoreable large amplicon size differences. The IGGPIPE algorithm is flexible enough to make use of whole-genome sequence data in either fully assembled chromosome form or partially assembled scaffold form, as markers have been generated and tested using both reliable scaffolds and fully assembled genomes. Assemblies with substantial redundancy may not be good data sources for IGGPIPE, as they will result in an absence of unique k-mers in the redundant region and therefore fewer IGG markers, but this is advantageous in that it produces a low marker false-positive rate. Furthermore, the use of assembled genomes with substantial redundancy in addition to scaffold misassembly will have greater false-positive and false-negative rates than assemblies with substantial redundancy alone. Some pipeline steps, such as e-PCR, can be extremely slow when there are hundreds of thousands of scaffolds, so it is recommended that very short scaffolds that are unlikely to contribute markers be removed.

One distinct advantage of the IGGPIPE algorithm is that it is sufficiently flexible to identify multiallelic markers, allowing the differentiation of more than two genomes. A parameter (NDAMIN) specifies the number of distinct amplicon sizes that must be present among the genomes being analyzed in order for a marker to be valid. In the three-way test using tomato, S. pennellii, and potato, we used a value of 2 for this parameter, and the nonoverlapping markers included 239 triallelic and 5,166 biallelic markers. The pipeline has not been tested with more than three genomes, although it is written with no hard limit. A possible use would be to run several dozen related genomes, for instance with several related landraces of a particular species, with NDAMIN set to 5. This would generate markers for loci having at least five distinct alleles among the genomes. A series of such markers could be used as fingerprinting markers. Future IGGPIPE enhancements could include population genomics features such as the assessment of information content at multiallelic loci, which assists in choosing the best markers for studies such as the assessment of population-wide variation. A number of usage cases are illustrated in Table XI.

Table XI. IGGPIPE usage cases.

Parameter values are meant to provide a rough guide to what is reasonable, but other values also can be used. Memory usage increases dramatically with k, so smaller values of k may be runable on a personal computer, while larger values may require servers with more memory. N/A, Not applicable.

| Description | Genomes | FASTA | k | NDA-MIN | LMIN = AMIN | KMIN/DMIN | DMAX = AMAX | ADMIN/ADMAX | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular two-accessions/two-species diploid markers | Two sequenced genomes (accessions or highly syntenic species); at least one can be chromosomal if chromosomal position coordinates are needed | Two FASTA files; if nonchromosomal assembly, remove all small scaffolds | 13…16 | 2 | ≥100 | 2..4/1..10 | AMIN +10 ...5,000 | 1..4,900/ADMIN …4,900 | Each marker’s two primers produce one uniquely sized amplicon in each species |

| Multiaccession/multispecies multiallelic markers | Three (or more) sequenced genomes, say n of them | n FASTA files, one per genome, with unwanted sequences removed | 14…17 | 2..n | “ | “ | “ | “ | There are between NDAMIN and n unique amplicon sizes per marker (NDA column); if fewer than n, some genomes share the same amplicon size |

| Fingerprinting markers | Numerous sequenced genomes, say n of them; perhaps n > 10, but this is untested | n FASTA files | 13…17 | Say 5 | “ | “ | “ | “ | There are between five and n unique amplicon sizes per marker, some species may share; use two or more markers to obtain unique sets of amplicon sizes for each species |

| Two-accessions/two-species polyploid markers | Two good-quality polyploid genomes | Two FASTA files, each containing all subgenomes | 15…17a | 2 | “ | “ | “ | “ | Each marker’s two primers produce one uniquely sized amplicon in each species; marker density is lower because of subgenome similarity |

| Polyploid subgenome markers | One good-quality polyploid genome, chromosomal, not scaffold based | Split into n FASTA files, each with one subgenome; n = number of subgenomes | 15…17b | 2..n | “ | “ | “ | “ | There are between NDAMIN and n unique amplicon sizes per marker (NDA column); if n, each subgenome produces its own unique amplicon size |

| Polyploid (or diploidc) presence/absence marker with control | One good-quality polyploid genome, chromosomal (or diploid genomec) | Two FASTA files, one with target subgenome, one with other subgenomes | 15…17a | 2 | “ | “ | “ | “ | Each marker’s two primers produce one uniquely sized amplicon in the target subgenome and one in one of the other subgenomes |

| Two target regions on different chromosomes, polyploid (or diploidc) | One good-quality polyploid genome, chromosomal (or diploid genomec) | Two FASTA files, one with target 1 chromosome, the other with target 2 chromosomed | “ | 2 (or 3d) | “ | “ | “ | “ | Each marker’s two primers produce one uniquely sized amplicon in target chromosome 1 and one in target chromosome 2 |

| cDNA markers | Two good-quality assembled transcriptomes of accessions or related species | Two FASTA files with transcriptomes; best to remove contigs smaller than LMIN + ADMIN | 12…15 | 2 | “ | “ | “ | “ | Each marker’s two primers when amplifying from a cDNA library produce one uniquely sized amplicon in each species |

| Diploid genotyping markers | One genome with a large database of indels commonly found within it | Two FASTA files, one the main genome, the other the same genome but modified to apply the indels | 13…16 | 2 | “ | “ | “ | “ | Each marker’s two primers produce one uniquely sized amplicon from the main genome and one from the modified genome |

| Identify major structural variation | Two sequenced genomes (accessions or highly syntenic species), both chromosomal, not scaffold based | Two FASTA files, one for each genome | 14…16 | N/A | 100 | 4/1 | 3,000 | 100/100 | make findLCRs clone dotplot.template and edit it Rscript code/R/dotplot.R < myfile > |

Larger k may be needed for more unique k-mers, to increase odds of finding markers that amplify uniquely in only one subgenome.

Larger k may be needed for more unique k-mers, to increase odds of finding markers that amplify uniquely in each subgenome.

The same technique works with diploid genomes, treating one target chromosome as a subgenome, but the density of markers will be lower than with a polyploid, since the chromosomes have less redundancy between them than polyploid subgenomes.

This technique can be combined with the one on the preceding row to generate markers that have a third amplicon that serves as a PCR control, by putting the remaining chromosomes into a third FASTA file and using NDAMIN = 3. The density of markers will be lower.

The method also can be used with polyploid species. The additional redundancy in the genomes means that the value used for k may need to be increased so that a sufficient number of unique k-mers is found. Another twist on polyploid analysis is to separate the subgenomes and run them through IGGPIPE as if they are separate genomes. The resulting markers may be used to distinguish between homeologous chromosomes. Another polyploid technique enables one to find IGG markers where a single primer pair produces one amplicon of unique size for a target chromosome region in one subgenome and a second amplicon of unique size from one chromosome of any of the other subgenomes, permitting a single primer pair PCR to test for the presence of a target region while using the second amplicon as a positive control. Alternatively, multiple genomic locations could be screened simultaneously, effectively allowing a single primer set to behave as a multiplex PCR. If detailed indel information is available for a diploid genome, it can be applied to construct a second genome containing the indels that, when used as IGGPIPE input, would produce markers for genotyping loci. Finally, IGGPIPE could be used to compare and generate complementary DNA (cDNA) IGG markers, using sequenced and assembled cDNA libraries of two related genotypes. Such markers could be used to amplify regions from cDNA libraries.

A strong positive correlation between IGG marker density and gene density is visible in marker/gene plots for tomato (Fig. 5C), where the Pearson correlation of marker density and gene density measured in 5-Mb windows was 0.83. In contrast, in the Arabidopsis Col-0 genome, a negative correlation of −0.34 was observed, and for all chromosomes (except perhaps chromosome 1), the marker density was highest in the heterochromatic regions where gene density was lowest (Fig. 5D). The Arabidopsis analysis was between accessions, whose intergenic regions retain enough sequence identity that LCRs are found within most of the region, and the rapid evolution of polymorphisms in the heterochromatic region likely leads to a high indel density (Fig. 4D; Supplemental Fig. S7). We hypothesize that, between species such as tomato and S. pennellii, intergenic regions have had sufficient time to thoroughly diverge from one another and LCRs can no longer be found throughout a majority of the region, leading to an overall low indel density in these regions (Fig. 4C; Supplemental Fig. S7). Nevertheless, enough LCRs are found in intergenic regions of tomato to cover about 40% of the region, and within those locally conserved regions, indel density is on a par with UTR indel density (Fig. 4C; Supplemental Fig. S7).

IGGPIPE includes the code module alignAndGetIndelsSNPs that extracts DNA sequence around markers, Indel Groups, or LCRs, aligns it, and examines it for indels and SNPs. SNPs, for example, are a rich source of polymorphisms that often are used in genome-wide association studies. The LCR file from the IGGPIPE comparison of the S. lycopersicum SL2.40/ITAG2.3 and S. pennellii V2.0 genomes produced 391,968 putative indels and 2.41 million putative SNPs with parameters that included amplicon size range of 100 to 3,000 bp and amplicon difference of 100 bp.

The LCRs, Indel Groups, and IGG markers themselves also are of use as they are essentially a form of whole-genome alignment. The good match between a dot plot of LCRs produced by the IGGPIPE module dotPlot (Supplemental Fig. S1) and a dot plot of locally colinear blocks produced by progressiveMAUVE (Darling et al., 2010; Supplemental Fig. S2) illustrates the accuracy of the IGGPIPE alignment. Therefore, the data might be useful for other purposes, such as mapping features between the genomes that were analyzed, including translocations or inversions, or even local duplications.

Finally, in the future, the uses of unique k-mers could be extended. Unique k-mers in one genome that do not occur in another genome (genome-unique k-mers) could be used as primer design sites to make allele-specific markers, amplifying only when one particular allele is present. Both genotype-unique and common unique k-mers can be used together to make an alternative type of allele-specific marker that includes a second PCR diagnostic band. The method would be to design three primers, the first at a genome-unique k-mer near the target site in the target genome, the second at a common unique k-mer near the first, and the third at a nearby genome-unique k-mer in the nontarget genome, and then run a three-primer PCR. Combined genotype-unique and common unique k-mers also could be employed as an alternative way of measuring gene expression in an RNA sequencing experiment, by identifying genes containing these k-mers and counting the number of reads containing k-mers found in each gene. This method might prove faster than mapping reads to a reference and could be just as accurate. Finally, k-mers could be used to search for duplicated regions by looking for clustering of k-mers that all occur the same number of times in a genome, and primers designed around these k-mers would amplify the duplicated regions.

CONCLUSION

Common unique k-mers can be used to effectively identify large numbers of groups of one or more adjacent indel polymorphisms in two or more species or populations, flanked by conserved regions where IGG marker primers can be designed to amplify the intervening region, which can be selected for a preferred size range and preferred minimum size difference between species. The method can be extended to use genome-unique k-mers to create allele-specific markers and to create markers that can amplify regions present in specific copy numbers. The method for choosing an Indel Group spanning multiple indels in order to achieve flexibility in amplicon sizes can be extended to any in silico indel marker algorithm as long as contig boundaries are honored. Sets of k-mers present in each genome in varying copy numbers may be useful in whole-genome alignment or copy number analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

IGGPIPE