The first description of the enlarged heart of athletes came in 1899, based only on physical examination with percussion, but later recognized by quantitative chest radiology (1). Over the past 40 years, imaging (largely with echocardiography) has provided a direct assessment of “athlete's heart” (2–12), which describes physiologic cardiac adaptations associated with physical training, often in the context of competitive sports.

Cardiac dimensional alterations in athletes have been the focus of many cross-sectional studies characterizing chamber size (ventricles, left atrium, and aorta) and also left ventricular (LV) wall thickness (2–12). Early M-mode studies suggested certain morphologic alterations were related to type of sport and/or training regimen (i.e., isotonic [running] vs. isometric [weightlifting]). The first hypothesis that isometric sports would induce increased LV wall thickness while isotonic sports are associated with ventricular cavity enlargement created initial interest in this area of investigation (13), but ultimately proved to be much more complex than originally anticipated (14). Indeed, LV chamber enlargement has been shown to be a common adaptation to training, most impressive with endurance sports (e.g., distance running and swimming, cycling, cross-country skiing, and rowing) (2–6,8) but reversible with cessation of systematic conditioning (9–11).

Ultimately, a vast literature has evolved defining the structural and functional features of the trained athlete heart (4,400 publications in PubMed). At the forefront of this effort has been Dr. Pelliccia's group at the Institute of Sports Medicine and Science (Rome) who over 25 years have meticulously assembled and tabulated echocardiographic data in thousands of highly trained and elite athletes, many at the Olympic level (6,7,9,10,14). These data, largely using absolute cavity and wall thickness measurements not indexed to body size (most applicable to the clinical environment) have been instrumental in developing many modern principles of the heart in athletes. These investigators continue to define this area of research with the accompanying study of >1,000 Olympic athletes.

An early prominent echocardiographic observation in elite rowers and cyclists was an increased absolute ventricular septal thickness, mimicking hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) (6). The possibility that young highly trained high school, college, or even Olympic/professional athletes could harbor potentially lethal heart diseases susceptible to sudden death has been a major topic within cardiovascular medicine (15–18). Therefore, another important application of echocardiography has been distinguishing benign athlete's heart from several pathologic cardiac conditions associated with the potential for sudden death or disease progression (8,11,15–18).

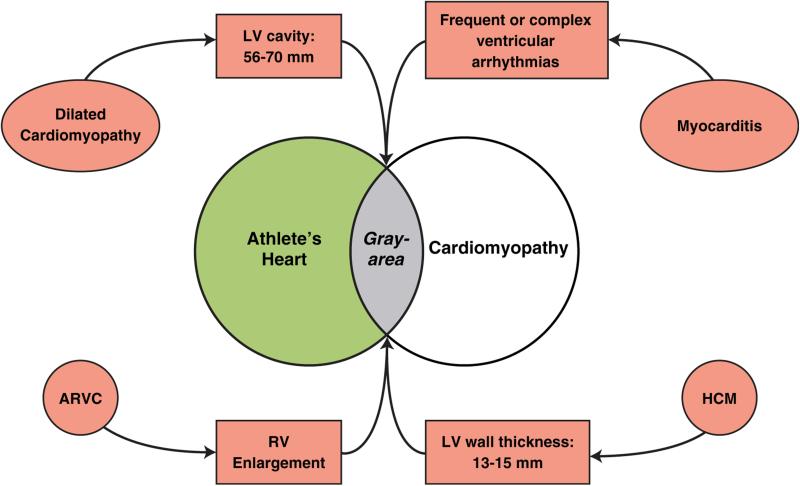

Pathologic conditions for which echocardiographic (or cardiac magnetic resonance) reference values overlap with physiologic athlete's heart include HCM, dilated cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) (Figure 1), each of which are known to be important causes of sudden death in young people and athletes (18), and for which disqualification from intense sports is justified to create a safer athletic field (18). Such differential diagnoses can represent major clinical dilemmas, given that athlete's heart is regarded as benign without the development of cardiac symptoms or arrhythmic risk, and itself would not justify disqualification from competitive sports (18). However, overdiagnosis of cardiac disease in athletes can have the paradoxic effect of unnecessary removal from competitive sports, with substantial loss of psychologic investment in (and enjoyment of) competition, reduced quality of life, and even lost economic opportunities (18).

FIGURE 1. Differential Diagnosis Between Athlete's Heart and Cardiac Disease.

Overlap between physiologic LV hypertrophy and pathologic conditions is shown in gray. ARVC = arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LV = left ventricular; RV = right ventricular.

In the case of HCM, differential diagnosis with athlete's heart most frequently arises when LV wall thickness is in the ambiguous “gray zone” of overlap between extreme expressions of athlete's heart and the mild HCM phenotype, of 13 to 15 mm (12 to 13 mm in women) (7,8,10,11,18).

In such instances, diagnosis can often be resolved by applying noninvasive markers. HCM is favored with LV end-diastolic cavity <45 mm, identification of a pathogenic sarcomere mutation or family history of HCM, unusual LV wall thickness patterns including noncontiguous segmental hypertrophy, abnormal LV filling/relaxation, particularly marked left atrial enlargement, or late gadolinium enhancement on contrast cardiac magnetic resonance. Athlete's heart is more likely when LV cavity is enlarged (≥55 mm) (10), peak VO2 is >110% of expected, or when LV thickness or mass decreases with short periods of deconditioning (9–11) (Figure 1).

In this issue of iJACC, D'Ascenzi et al. (19) from Rome have studied a unique cohort of Olympic-level competitors and revisited the differential diagnosis of athlete's heart and cardiac disease. They have addressed the reliability of an ARVC diagnosis in individuals with remodeling and enlargement of the right ventricular (RV) chamber caused by long periods of systematic endurance training.

This is an important objective, because adaptive changes in RV geometry and function induced by high-level physical activity remain incompletely characterized, and specific RV dimensions diagnostic of ARVC in athletes are not currently available. However, RV remodeling patterns correlate with exercise subtype: endurance athletics (e.g., competitive swimming, running) are characterized by RV elongation and dilation, whereas isometric physical activities (e.g., power weight lifting, rowing) induce little change in RV structure (20), reminiscent of changes reported in LV morphology with training many years ago (13).

Mechanisms that account for these differences are not entirely known, although increased cardiac output during aerobic activity greatly expands end-diastolic RV volume. Compared with the LV, the RV is a noncompacted structure with increased compliance, and its shape is sensitive to loading conditions (21).

In their report, D'Ascenzi et al. (19) leveraged their unique access to Olympic athletes to document RV cavitary enlargement in up to one-third, most marked associated with endurance sports. Their findings in the RV outflow tract long-axis were consistent across RV measurements in other views, expanding on previously reported findings in smaller cohorts (22,23). On the basis of these data, it is also apparent that RV enlargement is more common in trained athletes than in the general population (24), substantiating that enlarged RV dimension alone is unlikely to be a reliable diagnostic criterion for ARVC in elite athletes. However, because impaired RV systolic function is associated with ARVC, it is possible that the combination of RV dilation and systolic dysfunction could be a useful diagnostic marker for ARVC.

Despite the rigor and completeness of the D'Ascenzi et al. (19) data, the failure for criteria to emerge from this cohort delineating ARVC from athlete's heart is perhaps not surprising (25). Indeed, a high false-positive rate for the diagnosis of ARVC in athletes is to be expected, given not only the overlap in RV dimensions between athlete's heart and ARVC, but also the large proportion of Olympic athletes who exhibit echocardiographic morphological findings often evident in documented ARVC, including rounded RV apex, and prominent RV trabeculations and moderator band.

Overall, the contribution from D'Ascenzi et al. (19) expands the current understanding of RV remodeling patterns in elite athlete subgroups (26), by providing a robust dataset showing that RV elongation and cavitary dilation can be anticipated as part of the athlete's heart clinical profile. However, the differential diagnosis of athlete's heart and ARVC remains a difficult clinical problem. To achieve greater clarity there is a need for future studies defining RV morphology in athletes: linked to outcome and including those with a confirmed ARVC diagnosis as an internal reference (27). Availability of such data would provide greater confidence for distinguishing physiological RV enlargement from ARVC, and aid in screening athlete populations for cardiovascular disease with imaging.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Bradley A. Maron has received research funding from Gilead Sciences; and has received support from the National Institutes of Health (K08HL111207.01AL), American Heart Association (15GRNT25080016), and the Cardiovascular Medical Research and Education Fund.

Footnotes

Dr. Barry J. Maron has reported that he has no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Editorials published in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging or the American College of Cardiology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Henschen S. Skilanglauf und skiwettlauf. Eine medizinische sportstudie. Mitt Med Klin Upsala (Jena) 1899;2:15–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huston P, Puffer JC, MacMillan RW. The athletic heart syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1985;315:24–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198507043130106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pluim BM, Zwinderman AH, van der Laarse A, van der Wall EE. The athlete's heart. A meta-analysis of cardiac structure and function. Circulation. 2000;101:336–44. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauser AM, Dressendorfer RH, Vos M, Hashimoto T, Gordon S, Timmis GC. Symmetric cardiac enlargement in highly trained endurance athletes: a two-dimensional echocardiographic study. Am Heart J. 1985;109:1038–44. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maron BJ. Structural features of the athlete heart as defined by echo-cardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;7:190–203. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelliccia A, Maron BJ, Spataro A, Proschan MA, Spirito P. The upper limit of physiologic cardiac hypertrophy in highly trained elite athletes. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:295–301. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101313240504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pelliccia A, Maron MS, Maron BJ. Assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy in a trained athlete: differential diagnosis of physiologic athlete's heart from pathologic hypertrophy. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;54:387–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maron BJ, Pelliccia A. The heart of trained athletes: cardiac remodeling and the risks of sports, including sudden death. Circulation. 2006;114:1633–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.613562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelliccia A, Maron BJ, De Luca R, Di Paolo FM, Spataro A, Culasso F. Remodeling of left ventricular hypertrophy in elite athletes after long-term deconditioning. Circulation. 2002;105:944–9. doi: 10.1161/hc0802.104534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caselli S, Maron MS, Urbano-Moral JA, Pandian NG, Maron BJ, Pelliccia A. Differentiating left ventricular hypertrophy in athletes from that in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:1383–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maron BJ, Pelliccia A, Spirito P. Cardiac disease in young trained athletes. Insights into methods for distinguishing athlete's heart from structural heart disease, with particular emphasis on hyper-trophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1995;91:1596–601. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.5.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelliccia A, Culasso F, Di Paolo FM, Maron BJ. Physiologic left ventricular cavity dilation in elite athletes. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:23–31. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-1-199901050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morganroth J, Maron BJ, Henry WL, Epstein SE. Comparative left ventricular dimensions in trained athletes. Ann Intern Med. 1975;82:521–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-82-4-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelliccia A, Spataro A, Caselli G, Maron BJ. Absence of left ventricular wall thickening in athletes engaged in intense power training. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72:1048–54. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90861-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maron BJ, Haas TS, Ahluwalia A, Murphy CJ, Garberich RF. Demographics and epidemiology of sudden deaths in young competitive athletes: from the United States National Registry. Am J Med. 2016 Apr 1; doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.02.031. E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maron BJ. Historical perspectives on sudden deaths in young athletes with evolution over 35 years. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:1461–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corrado D, Basso C, Pavei A, Michieli P, Schiavon M, Thiene G. Trends in sudden cardiovascular death in young competitive athletes after implementation of a preparticipation screening program. JAMA. 2006;296:1593–601. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.13.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maron BJ, Udelson JE, Bonow RO, et al. Eligibility and disqualification recommendations for competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities: Task Force 3: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and other cardiomyopathies, and myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2362–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Ascenzi F, Pisicchio C, Caselli S, Di Paolo FM, Spataro A, Pelliccia A. RV remodeling in Olympic athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2016;9:XXX–XXX. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiner RL, Baggish AL. Exercise-induced cardiac remodeling. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;54:380–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maron BA. Targeting neurohumoral signaling to treat pulmonary hypertension: the right ventricle coming into focus. Circulation. 2012;126:2806–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.149534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D'Ascenzi F, Pelliccia A, Corado D, et al. Right ventricular remodeling induced by exercise training in competitive athletes. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17:301–7. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Andrea A, Riegler L, Golia E, et al. Range of right heart measurements in top-level athletes: the training impact. Int J Cardiol. 2013;164:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawut SM, Barr RG, Lima JA, et al. Right ventricular structure is associated with the risk of heart failure and cardiovascular death: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) – right ventricle study. Circulation. 2012;126:1681–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.095216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaidi A, Ghani S, Sharma R, et al. Physiological right ventricular adaptation in elite athletes of African or Afro-Caribbean origin. Circulation. 2013;127:1783–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:685–713. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marcus FL, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the task force criteria. Circulation. 2010;121:1533–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.840827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]