Abstract

Introduction

During storage, packed red blood cells undergo a series of physical, metabolic, and chemical changes collectively known as the red blood cell storage lesion. One key component of the red blood cell storage lesion is the accumulation of microparticles, which are submicron vesicles shed from erythrocytes as part of the aging process. Previous studies from our laboratory indicate that transfusion of these microparticles leads to lung injury, but the mechanism underlying this process is unknown. In the present study, we hypothesized that microparticles from aged packed red blood cell units induce pulmonary thrombosis.

Materials and Methods

Leukoreduced, platelet-depleted, murine packed red blood cells (pRBCS) were prepared then stored for up to 14 days. Microparticles were isolated from stored units via high-speed centrifugation. Mice were transfused with microparticles. The presence of pulmonary microthrombi was determined with light microscopy, Martius Scarlet Blue, and thrombocyte stains. In additional studies microparticles were labeled with CFSE prior to injection. Murine lung endothelial cells were cultured and P-selectin concentrations determined by ELISA. In subsequent studies, P-selectin was inhibited by PSI-697 injection prior to transfusion.

Results

We observed an increase in microthrombi formation in lung vasculature in mice receiving microparticles from stored packed red blood cell units as compared with controls. These microthrombi contained platelets, fibrin, and microparticles. Treatment of cultured lung endothelial cells with microparticles led to increased P-selectin in the media. Treatment of mice with a P-selectin inhibitor prior to microparticle infusion decreased microthrombi formation.

Conclusions

These data suggest that microparticles isolated from aged packed red blood cell units promote the development of pulmonary microthrombi in a murine model of transfusion. This pro-thrombotic event appears to be mediated by P-selectin.

Keywords: RBC microparticles, P-selectin, endothelial activation, pulmonary thrombus

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic injury is a leading cause of death in our military and civilian populations.1 Hemorrhagic shock accounts for a third of trauma-related mortality, and a significant proportion of these deaths are considered potentially preventable with expeditious treatment.2–6 The current standard of care for exsanguinating hemorrhage is to obtain hemostasis and transfuse blood products.7–9 Blood transfusion in equal ratios of plasma and packed red blood cells, termed “balanced” or “damage control resuscitation,” aims to correct the physiological derangements of hemorrhagic shock in multiple ways.10–13 First, intravascular hypovolemia is restored while limiting exposure to crystalloid fluids. Second, transfused red blood cells (RBC) replenish the capacity for oxygen delivery to hypoxic tissues. Third, plasma transfusion addresses the coagulopathy associated with uncontrolled hemorrhage.

Despite these benefits, the transfusion of blood products may also expose its recipients to harm. Recent studies indicate that the duration of red blood cell storage prior to transfusion is been associated with increased mortality.14,15 The red blood cell storage lesion, consisting of a series of structural, metabolic, and biochemical changes that occur within packed red blood cell units (pRBCs) over time has been implicated in a host of transfusion-related complications.16,17 Microparticles are one key element of the red blood cell storage lesion, and refer to submicron vesicles shed from the aging erythrocytes.17–19 Previously dismissed as nonfunctional cellular debris, microparticles have now been demonstrated to play integral roles in cell-to-cell signaling and certain disease states.20–22 In recent studies, our laboratory has demonstrated that microparticles isolated from aged pRBCs contribute to a hypercoagulable state in transfusion recipients23 as well as the pathogenesis of transfusion-related lung inflammation, in part due to activation of endothelial cells.17,20,24,25

In the current study, we hypothesized that microparticles isolated from aged pRBC units promote thrombotic events in a murine model of transfusion that may, in turn, lead to lung inflammation. Our data indicates that transfusion of microparticles leads to the formation of platelet and fibrin-rich microthrombi within the pulmonary vasculature. We demonstrate that microparticles promote secretion of P-selectin from lung endothelial cells. P-selectin inhibition attenuated the formation of microthrombi after microparticle transfusion, suggesting that microparticles isolated from aged pRBC units promote thrombotic sequelae through a P-selectin-dependent mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal housing and preparation

Male C57BL/6-strain mice aged eight to ten weeks were obtained from a local vendor (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). All mice were acclimated to a 12-hour light-dark cycle for at least one week in our animal housing facility (Medical Sciences Building, Cincinnati, OH), and fed a standard laboratory diet and water ad libitum. Mice weighed 21 to 30 grams prior to experimentation. We focused on male mice primarily in order to reduce gender-related variability in the development of the storage lesion. Specifically, mouse gender has been shown to play a role in various RBC-related characteristics, including ability to withstand mechanical stress, membrane integrity, and predilection for hemolysis during the storage period.26–28 By excluding female mice from serving as blood donors and microparticle recipients, we aimed to remove any potentially confounding variables from our experimental model. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in accordance with their animal use guidelines.

Microparticle collection protocol

Microparticles were isolated from aged pRBC units stored using previously described murine blood banking protocols.17,20 Briefly, fresh whole blood was harvested from mice through open cardiac puncture, and immediately added to citrate phosphate double dextrose (CP2D) anticoagulant solution in a 1:7 ratio. Anticoagulated whole blood was centrifuged at 2,000 gravity (g) for 15 minutes in order to separate the cellular components. The platelet-rich plasma and leukocyte-rich buffy coat were removed, and the RBC pellet was suspended in isotonic phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in a 1:10 ratio. The RBCs were again centrifuged at 2000 g for 15 minutes, and the supernatant fraction was again discarded. This second washing process is performed to remove any residual platelet fragments from the isolated RBC pellet. These RBCs are then added to additive solution-3 (AS-3), a blood storage solution, in a 2:9 ratio as per standard blood banking practice, and stored at 4°C in light-protected conditions with gentle agitation.

Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that murine pRBCs accumulate biochemical, structural, and metabolic changes at an increased rate as compared to human pRBCs.29 As current US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations allow human pRBC units to be stored up to 42 days30, our murine pRBC units were stored for a 14-day period based on previous studies from our lab.29 At the end of the storage period, microparticles were isolated from the aged pRBC units through serial centrifugation. First, the pRBC unit was spun at 2,000 g for 10 minutes to separate the cellular and microparticle-rich supernatant. The supernatant fraction was again centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 minutes to purify the microparticle-rich supernatant from subcellular debris. The remaining supernatant was centrifuged at 20,000 g for 30 minutes to isolate the microparticle pellet. Isolated microparticles were suspended in either endothelial cell culture medium (for in vitro experiments) or PBS (for in vivo experiments). While previous experiments from our laboratory indicate that microparticles isolated through this serial centrifugation protocol appear to be more than 90% erythrocyte-derived, characterization of microparticles by flow cytometry may not fully capture the nature of the microparticles isolated from aged packed red blood cell units and these samples may also contain unknown quantities of platelet and leukocyte-derived microparticles as well.16,17,23

Murine model of transfusion

To determine whether microparticles isolated from aged pRBC units contribute to the formation of pulmonary microthrombi, mice were anesthetized under inhaled isoflurane, then transfused with microparticles derived from 1 ml of mouse blood (10.7±1.1 x 106 microparticles23) through penile vein injection. Control mice were injected with an equivalent volume (200 μl) of PBS vehicle. Lungs were harvested following incubation periods of 1, 4, 8, and 24 hours and fixed with paraformaldehyde.

In separate experiments, microparticles were labelled using carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE). CFSE is a green-fluorescent dye that covalently couples to lysine residues, allowing identification through immunofluorescence and flow cytometry techniques.31 To determine the presence of pRBC-derived microparticles within pulmonary vasculature following transfusion, CFSE-labelled microparticles were suspended in saline vehicle and intravenously transfused as previously described. An equivalent volume of saline vehicle was given to control mice. Lungs were harvested after 1, 4, 8, and 24-hour incubation periods, and deparaffinized lung sections were analyzed for presence and quantity of green-fluorescent microparticles.

Pulmonary histology analysis

Staining of lung sections was performed to analyze the phenotypic differences between the control and experimental groups. Specifically, hematoxylin and eosin (H/E) staining was used to evaluate differences in murine pulmonary vasculature. Immunohistochemical staining for thrombocyte-specific antigen (anti-CD41, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used to determine the presence of platelet aggregates. Martius Scarlet Blue (MSB) staining was used to determine the presence of mature fibrin strands.

The concentration of CFSE-labelled microparticles within lung sections was quantified under immunofluorescent microscopy. Eight random captures of each slide were taken at the lowest magnification using imaging software ZEN version 1.1.2.0 on Axio Imager M2 microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany). Light microscopy was similarly used to analyze murine lungs stained with H/E, thrombocyte-specific antigen, and MSB.

Endothelial cell model

Primary murine lung microvascular endothelial cells (MLEC) isolated from pathogen-free C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Cell Biologics (Chicago, IL). MLECs were grown to confluent monolayers in mouse endothelial cell medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cultured cells were then treated with microparticles isolated from 1 ml of murine blood suspended in cell medium for one hour. Cells treated with culture medium only served as a negative control. After the treatment period, cellular supernatant was collected. Preabsorbed P-selectin ELISA kits were used to quantify secreted P-selectin levels per manufacturer protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

P-selectin inhibition

PSI-697 [2-(4-chlorophenylmethyl)-7,8,9,10-tetrahydro-3-hydroxybenzo[h]quinoline-4-carboxylic acid] is a molecular P-selectin inhibitor that has been shown to attenuate the thrombotic effects of P-selectin in small animal models (MedChem Express, Monmouth Junction, NJ).32,33 In order to determine whether microparticle-associated pulmonary microthrombi formation was mediated by P-selectin, mice were anesthetized under inhaled isoflurane, then intraperitoneally injected with PSI-697 (40 mg/kg) suspended in PBS (100 μl). After a 15-minute observation period, mice were intravenously transfused with microparticles derived from 1 ml of mouse blood suspended in PBS (200 μl). Mice were sacrificed after one hour and lung samples were harvested and fixed in paraformaldehyde for histological analysis. For control mice, lungs were harvested from mice injected with saline vehicle prior to microparticle transfusion, and mice were injected with PSI-697 followed by PBS transfusion.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation where appropriate. Two-tailed Students t-test was used to compare groups. Significance was defined prior to analysis as P-values less than 0.05. SigmaPlot version 13.0 was used for statistical computation (Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

Microparticles contribute to pulmonary microthrombus formation

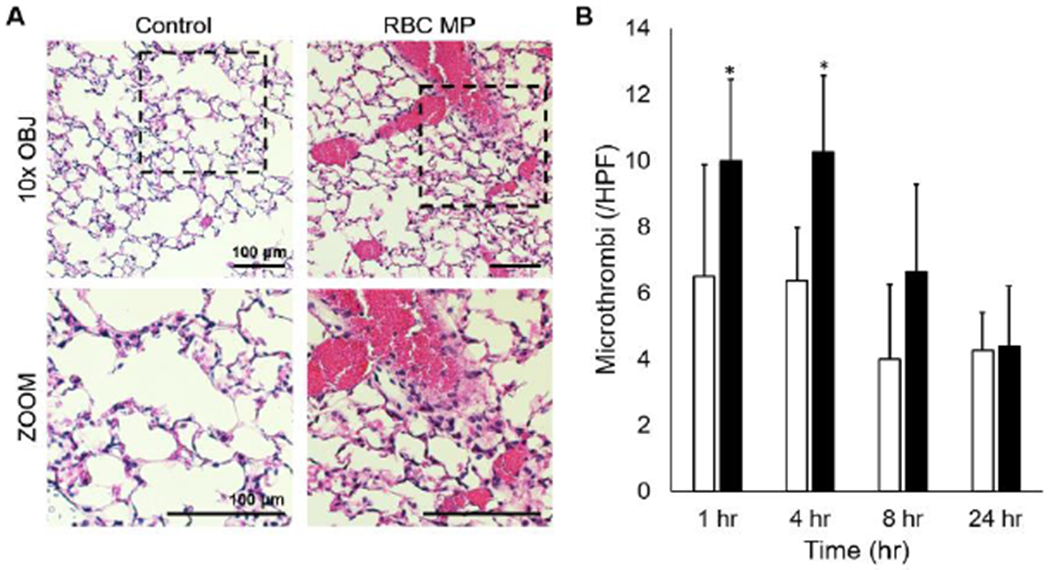

Mice transfused with microparticles isolated from aged pRBC units demonstrated increased pulmonary vessel congestion as observed under H/E staining as compared with mice injected with saline vehicle (Figure 1a). Differences in number of affected vessels per high-powered field (HPF) were greatest at one hour (10.0 vs 6.5 vessels/HPF) and four hours (10.3 vs 6.4 vessels/HPF) after transfusion (p<0.05 each). These differences resolved after eight hours (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(A) Representative photomicrographs demonstrating differences in murine lung vasculature between mice transfused with microparticles stored pRBC units (RBC MP) as compared to an equivalent volume of saline vehicle (control). (B) Quantification of the number of microthrombi observed per high-powered field at one and four hours after transfusion. *p<0.05 compared with control, n=8 at each time point.

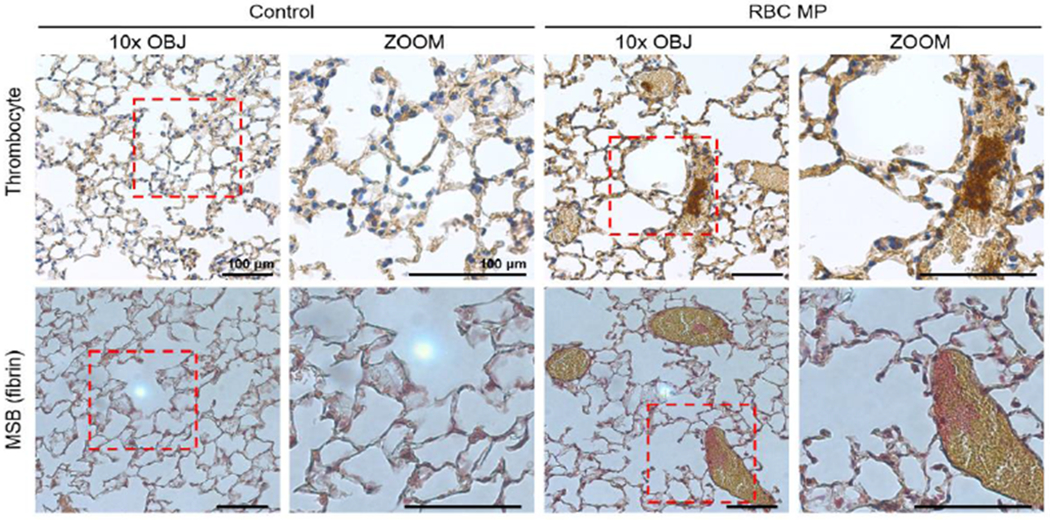

Immunohistochemical staining for thrombocytes demonstrated the presence of platelet aggregates within these congested vessels and MSB staining revealed pulmonary fibrin deposition (Figure 2), indicating that thrombi were present in these vessels.

Figure 2.

Representative photomicrographs from lung of mice transfused with red blood cell-derived microparticles (RBC MP) or saline vehicle (control). Immunohistochemical staining revealed the presence of platelet aggregates (top, dark brown) within these vessels. Martius Scarlet Blue (MSB) staining (bottom) revealed the presence of mature fibrin deposits (red).

Microparticles are present within pulmonary vasculature following transfusion

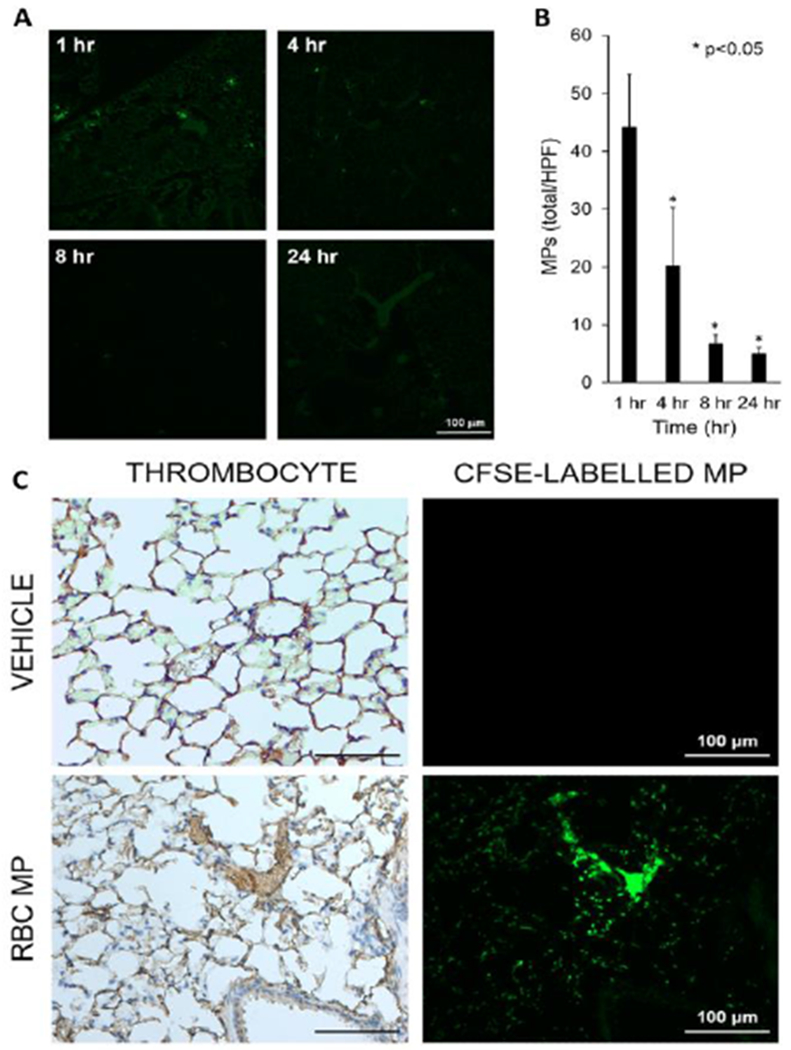

To determine if microparticles isolated from aged pRBC units were present within the pulmonary vasculature, microparticles were covalently labelled with CFSE, then transfused into mice. Microparticles were present in lungs within 1 hour after injection (44.1±9.2 microparticles/HPF) and in decreasing amounts at four, eight, and 24 hours (Figure 3A and 3B). Mice transfused with an equivalent volume of saline vehicle demonstrated no CFSE at any time point.

Figure 3.

(A) Mice were injected with CFSE-labelled microparticles (green) isolated from murine packed red blood cell units. The presence of microparticles within pulmonary vasculature was confirmed through immunofluorescent microscopy. (B) Mice transfused with microparticles had the greatest number of microparticles per high-powered field at one hour, followed by a temporal decrease in quantity over 24 hours. *p<0.05 compared with one hour, n=8 at each time point. (C) Representative lung sections after staining with anti-thrombocyte stain (left) and immunofluorescence microscopy (right) demonstrated the presence of microparticles (green) within these microthrombi.

In order to determine if microparticles from stored pRBC units were present in microthrombi in the pulmonary vasculature, mice were injected with CFSE-labelled microparticles. Mice treated with microparticles isolated from aged pRBC units again demonstrated microthrombus formation within the lungs (Figure 3C). The same deparaffinized lung sections were visualized under immunofluorescence for CFSE-labelled microparticles. Visualization of the images indicated that there are microparticle aggregates within the microthrombi (Figure 3C). Immunofluorescence examination of isolated microparticles prepared for transfusion demonstrated that CFSE-labelled microparticles did not aggregate prior to transfusion (data not shown).

P-selectin inhibition attenuates the formation of pulmonary microthrombi

Our data indicates that transfusion with microparticles isolated from stored pRBC units leads to the formation of microthrombi in the pulmonary vasculature. One potential mechanism for induction of microthrombi is direct activation of platelets by microparticles. ELISA for PF4 has been used in both laboratory and clinical settings for the detection of platelet activation.34–36 In order to test for direct platelet activation, we drew fresh whole blood from donor mice, then added either microparticles or vehicle to the fresh whole blood in a 1:5 ratio. After incubation, we determined serum PF4 concentrations by ELISA. There were no significant differences between the two groups (data not shown). These results indicate that microparticles do not directly activate platelets in an ex vivo setting.

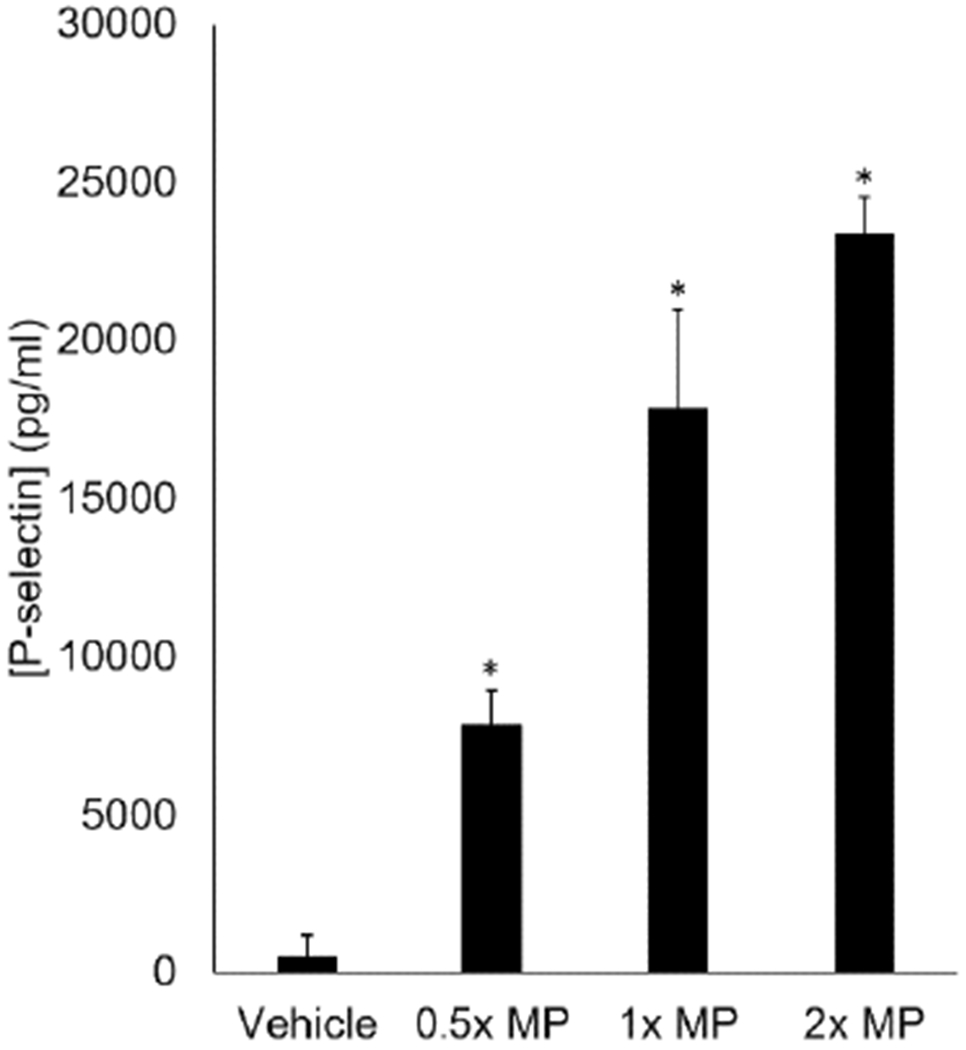

Previous studies from our laboratory demonstrate that microparticles isolated from stored pRBC units activate aspects of the inflammatory response in endothelial cells, including upregulation of E-selectin, ICAM, and IL-6.20,25 P-selectin is an important mediator of platelet recruitment and aggregation and may be released from alpha-granules of platelets or Weibel-Palade bodies of endothelial cells37. As our data indicate that platelets are not directly activated by microparticles, we hypothesized that microparticles from stored pRBC units led to P-selectin release from endothelial cells. To test this hypothesis, cultured murine lung endothelial cells were treated with microparticles isolated from aged pRBC units and P-selectin levels in cell culture media determined. Microparticle treatment led to a dose-dependent increase in P-selectin release from cultured murine lung endothelial cells (Figure 4). There was no P-selectin present in isolated microparticles or cell culture media (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Red blood cell derived microparticles promote the release of P-selectin from murine lung microvascular endothelial cells in a dose-response fashion. *p<0.05 compared with control, n=8.

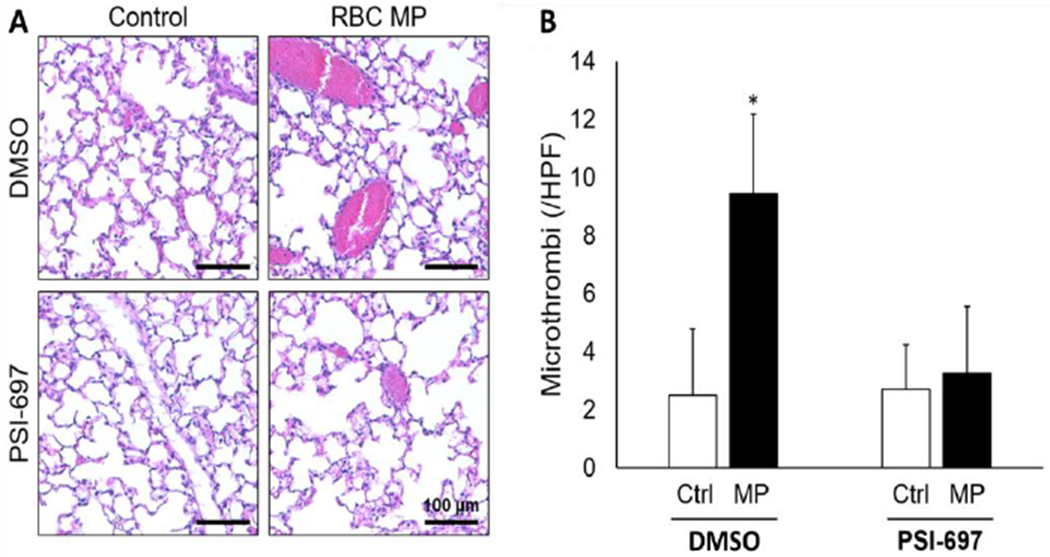

To determine whether P-selectin mediated the thrombogenic effect of microparticles isolated from aged pRBC units in vivo, mice were pretreated with PSI-697, a novel inhibitor of P-selectin32, prior to microparticle transfusion. Mice treated with vehicle served as controls and demonstrated a greater number of affected vessels after microparticle transfusion (Figure 5A and 5B). Comparatively, mice pretreated with PSI-697 demonstrated decreased pulmonary microthrombi after microparticle transfusion (Figure 5A and 5B). These results indicate that endothelial cells secrete P-selectin in response to microparticle exposure in vitro, and P-selectin inhibition attenuates the thrombogenic effect of microparticle transfusion in vivo.

Figure 5.

(A) Representative photomicrographs from lungs from mice treated with microparticles isolated from pRBC units (RBC MP) or normal saline (control) with or without the P-selectin inhibitor PSI-697 or vehicle (DMSO). (B) Quantification of microthrombi in lungs from mice treated with pRBC microparticles (MP) or normal saline (ctrl) with or without the P-selectin inhibitor PSI-697 or vehicle (DMSO). *p<0.05 vs control.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrate that the transfusion of microparticles from stored pRBC units leads to the development of pulmonary microthrombi. These microthrombi are composed of platelets and insoluble fibrin agglomerates and contain pRBC-derived microparticles. We also found that microparticles stimulate the release of P-selectin from cultured lung endothelial cells, and that inhibition of P-selectin attenuates microparticle-associated microthrombus formation, indicating that these microthrombi are facilitated by P-selection.

Microparticles isolated from aged pRBC units are bioactive mediators implicated in the development of transfusion-associated complications.17,18,20,24 Our data demonstrate that the transfusion of microparticles isolated from aged pRBC units promotes the development of congested pulmonary vessels. Special staining techniques revealed the presence of fibrin and platelet aggregates within these dilated vessels. Given that platelets and fibrin mesh are the primary components of venous clot38, this indicates that pulmonary vascular congestion is secondary to microthrombus formation. The presence of microparticles within microthrombi is also demonstrated through immunofluorescent labelling techniques. Taken together, this series of experiments suggests that microparticles derived from aged pRBC units have the potential for promoting thrombotic complications within the transfusion recipient.

This thrombogenic effect appears to be mediated by the adhesion molecule P-selectin. P-selectin is the largest of the selectin-class adhesion molecules, and is expressed constitutively within platelets and endothelial cells.39,40 Both cell types synthesize and store P-selectin within alpha granules and Weibel-Palade bodies, respectively. Once these cells become activated, their degranulation results in the rapid release of P-selectin into the bloodstream.41–43 Circulating P-selectin then alters the local hemostatic equilibrium through platelet aggregation44, leukocyte recruitment45,46, upregulation of monocyte tissue factor expression47, and tissue factor accumulation within developing thrombi.48 From a clinical perspective, P-selectin plays a role in the pathogenesis of several thrombotic diseases, including acute ischemic stroke, sickle cell crises, deep venous thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism.49–52

Our data indicate that microparticles isolated from aged pRBC units act as a stimulus for the release of P-selectin from cultured lung microvascular endothelial cells. Microparticles have previously been shown to promote a dysregulated endothelial activation response in mice, as evidenced by upregulation of adhesion molecules and inflammatory cytokines.20 Other studies have implicated endothelial activation as a mechanism for the development of venous thromboembolic events.53,54 By linking these two events through P-selectin secretion, our study provides additional information about the complex interactions between aged pRBC units, host endothelium, and mediators of coagulation.

The thrombotic effect of microparticle transfusion may be potentially counteracted in three separate ways. First, patients receiving aged pRBC units could be administered prophylactic doses of anticoagulation. While heparin has been shown to attenuate P-selectin-mediated adhesion in cancer cells, heparin prophylaxis is contraindicated in a bleeding patient.55–58 Second, microparticles themselves could be removed via cell washing prior to transfusion. This has been shown to curtail the pro-inflammatory response in mice, suggesting that the procoagulant effects may also be decreased.59 Washing pRBC units prior to transfusion in an emergent situation, however, may prove difficult from the standpoint of logistics. Third, the vesiculation of microparticles within the aged pRBC units can be reduced through treatment with amitriptyline.24 Inhibition of acid sphingomyelinase (ASM) stabilizes the erythrocyte lipid membranes, preventing the release of microparticles. Moreover, transfusion-associated acute lung injury is reduced by inhibiting ASM in stored pRBC units.24 Future investigations may elucidate the effect of ASM inhibition on transfusion-associated pulmonary microthrombus formation.

There are several potential limitations to this study and thus our findings should be interpreted with caution. These experiments were carried out in a murine model of blood banking and transfusion and thus our results may not reflect the human condition. Although we have previously characterized the process of human and murine packed red blood cell storage as well as aspects of the in vitro behavior of murine and human microparticles derived from stored packed red blood cells and found evidence of many similarities, there are important biological differences between the species that must be taken into account when considering the ramifications of our findings17,24,29,60. In addition, the nature and fate of circulating microparticles after trauma and transfusion remain incompletely understood. A recent study in patients undergoing massive transfusion after trauma demonstrated increases in circulating erythrocyte, endothelial cell, and leukocyte-derived microparticles after injury.61 A follow-up study from the same group demonstrated similar results in injured patients regarding microparticle phenotypes in circulation after trauma and blood transfusion.62 Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that the concentration of microparticles within stored human pRBC units exceeds that of murine pRBCs24, and that microparticles impact the recipient in a dose-dependent fashion.17 Therefore, patients who are transfused older units of pRBCs are exposed to high concentrations of microparticles, especially during massive transfusion. The contribution of pulmonary microthrombi to organ failure after trauma and transfusion is currently unknown, but a previous autopsy study determining the immunohistochemical distribution of von Willebrand factor (vWF) and platelet CD61 factor found a high rate of suspected thrombosis in vessels after acute trauma, suggesting that pulmonary microthrombi may occur after severe trauma in humans.63

CONCLUSION

The interactions between aged pRBC units, host endothelium, and mediators of coagulation are an area of ongoing investigation. In the current study, we demonstrate that that microparticles isolated from aged pRBC units contribute to the development of pulmonary microthrombi following transfusion. Microparticles act as a stimulus for the release of P-selectin from endothelial cells. Future studies may focus on methods to reduce or remove microparticles within the aging pRBC unit, in order to improve patient outcomes and reduce transfusion-related complications.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Transfusion of older red blood cells is associated with increased mortality.

Red blood cells develop a complex storage lesion as they age.

Red blood cell microparticles cause pulmonary thrombosis in murine model.

This thrombosis appears to be mediated by P-selectin.

Acknowledgments

Grants and Financial Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 GM107625 (TAP) and T32 GM008478-24 (YK).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presentation: Portions of this work were presented at the American Surgical Congress in Las Vegas, NV (Feb 8, 2017) and ACS Committee on Trauma in Cleveland, OH (May 12, 2017).

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rhee P, Joseph B, Pandit V, et al. Increasing trauma deaths in the United States. Ann Surg. 2014;260(1):13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans JA, van Wessem KJ, McDougall D, Lee KA, Lyons T, Balogh ZJ. Epidemiology of traumatic deaths: comprehensive population-based assessment. World J Surg. 2010;34(1):158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruen RL, Jurkovich GJ, McIntyre LK, Foy HM, Maier RV. Patterns of errors contributing to trauma mortality: lessons learned from 2,594 deaths. Ann Surg. 2006;244(3):371–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kauvar DS, Lefering R, Wade CE. Impact of hemorrhage on trauma outcome: an overview of epidemiology, clinical presentations, and therapeutic considerations. J Trauma. 2006;60(6 Suppl):S3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sauaia A, Moore FA, Moore EE, et al. Epidemiology of trauma deaths: a reassessment. J Trauma. 1995;38(2):185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart RM, Myers JG, Dent DL, et al. Seven hundred fifty-three consecutive deaths in a level I trauma center: the argument for injury prevention. J Trauma. 2003;54(1):66–70; discussion 70-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubick MA. Current concepts in fluid resuscitation for prehospital care of combat casualties. US Army Med Dep J. 2011:18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holcomb JB, Tilley BC, Baraniuk S, et al. Transfusion of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1:1:1 vs a 1:1:2 ratio and mortality in patients with severe trauma: the PROPPR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(5):471–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy CH, Hess JR. Massive transfusion: red blood cell to plasma and platelet unit ratios for resuscitation of massive hemorrhage. Curr Opin Hematol. 2015;22(6):533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cap AP, Pidcoke HF, Spinella P, et al. Damage Control Resuscitation. Mil Med. 2018;183(suppl_2):36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borgman MA, Spinella PC, Holcomb JB, et al. The effect of FFP:RBC ratio on morbidity and mortality in trauma patients based on transfusion prediction score. Vox Sang. 2011;101(1):44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borgman MA, Spinella PC, Perkins JG, et al. The ratio of blood products transfused affects mortality in patients receiving massive transfusions at a combat support hospital. J Trauma. 2007;63(4):805–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makley AT, Goodman MD, Belizaire RM, et al. Damage control resuscitation decreases systemic inflammation after hemorrhage. J Surg Res. 2012;175(2):e75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeSantis SM, Brown DW, Jones AR, et al. Characterizing red blood cell age exposure in massive transfusion therapy: the scalar age of blood index (SBI). Transfusion. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones AR, Patel RP, Marques MB, et al. Older Blood Is Associated With Increased Mortality and Adverse Events in Massively Transfused Trauma Patients: Secondary Analysis of the PROPPR Trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;73(6):650–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang AL, Kim Y, Seitz AP, Schuster RM, Lentsch AB, Pritts TA. Erythrocyte-Derived Microparticles Activate Pulmonary Endothelial Cells in a Murine Model of Transfusion. Shock. 2017;47(5):632–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belizaire RM, Prakash PS, Richter JR, et al. Microparticles from stored red blood cells activate neutrophils and cause lung injury after hemorrhage and resuscitation. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214(4):648–655; discussion 656-647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoehn RS, Jernigan PL, Chang AL, Edwards MJ, Pritts TA. Molecular mechanisms of erythrocyte aging. Biol Chem. 2015;396(6-7):621–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koch CG, Figueroa PI, Li L, Sabik JF 3rd, Mihaljevic T, Blackstone EH. Red blood cell storage: how long is too long? Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(5):1894–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang AL, Kim Y, Seitz AP, Schuster RM, Lentsch AB, Pritts TA. Erythrocyte Derived Microparticles Activate Pulmonary Endothelial Cells in a Murine Model of Transfusion. Shock. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chironi GN, Boulanger CM, Simon A, Dignat-George F, Freyssinet JM, Tedgui A. Endothelial microparticles in diseases. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;335(1):143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hargett LA, Bauer NN. On the origin of microparticles: From “platelet dust” to mediators of intercellular communication. Pulm Circ. 2013;3(2):329–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim Y, Xia BT, Jung AD, et al. Microparticles from stored red blood cells promote a hypercoagulable state in a murine model of transfusion. Surgery. 2018;163(2):423–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoehn RS, Jernigan PL, Japtok L, et al. Acid Sphingomyelinase Inhibition in Stored Erythrocytes Reduces Transfusion-Associated Lung Inflammation. Ann Surg. 2017;265(1):218–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim Y, Abplanalp WA, Jung AD, et al. Endocytosis of Red Blood Cell Microparticles by Pulmonary Endothelial Cells is Mediated By Rab5. Shock. 2018;49(3):288–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeVenuto F, Wilson SM. Distribution of progesterone and its effect on human blood during storage. Transfusion. 1976;16(2):107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanias T, Gladwin MT. Nitric oxide, hemolysis, and the red blood cell storage lesion: interactions between transfusion, donor, and recipient. Transfusion. 2012;52(7):1388–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raval JS, Waters JH, Seltsam A, et al. Menopausal status affects the susceptibility of stored RBCs to mechanical stress. Vox Sang. 2011;100(4):418–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makley AT, Goodman MD, Friend LA, et al. Murine blood banking: characterization and comparisons to human blood. Shock. 2010;34(1):40–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.en. United States Food and Drug Administration. Workshop on Red Cell Stored in Additive Solution Systems. Bethesda, MD: April 25, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyons AB. Analysing cell division in vivo and in vitro using flow cytometric measurement of CFSE dye dilution. J Immunol Methods. 2000;243(1–2):147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bedard PW, Clerin V, Sushkova N, et al. Characterization of the novel P-selectin inhibitor PSI-697 [2-(4-chlorobenzyl)-3-hydroxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydrobenzo[h] quinoline-4-carboxylic acid] in vitro and in rodent models of vascular inflammation and thrombosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324(2):497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Myers DD Jr., Henke PK, Bedard PW, et al. Treatment with an oral small molecule inhibitor of P selectin (PSI-697) decreases vein wall injury in a rat stenosis model of venous thrombosis. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44(3):625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chowdhury SM, Kanakia S, Toussaint JD, et al. In vitro hematological and in vivo vasoactivity assessment of dextran functionalized graphene. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gurney D, Lip GY, Blann AD. A reliable plasma marker of platelet activation: does it exist? Am J Hematol. 2002;70(2):139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warkentin TE. How I diagnose and manage HIT. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andre P P-selectin in haemostasis. Br J Haematol. 2004;126(3):298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aleman MM, Walton BL, Byrnes JR, Wolberg AS. Fibrinogen and red blood cells in venous thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2014;133 Suppl 1:S38–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonfanti R, Furie BC, Furie B, Wagner DD. PADGEM (GMP140) is a component of Weibel-Palade bodies of human endothelial cells. Blood. 1989;73(5):1109–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stenberg PE, McEver RP, Shuman MA, Jacques YV, Bainton DF. A platelet alpha-granule membrane protein (GMP-140) is expressed on the plasma membrane after activation. J Cell Biol. 1985;101(3):880–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burger PC, Wagner DD. Platelet P-selectin facilitates atherosclerotic lesion development. Blood. 2003;101(7):2661–2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunlop LC, Skinner MP, Bendall LJ, et al. Characterization of GMP-140 (P-selectin) as a circulating plasma protein. J Exp Med. 1992;175(4):1147–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michelson AD, Barnard MR, Hechtman HB, et al. In vivo tracking of platelets: circulating degranulated platelets rapidly lose surface P-selectin but continue to circulate and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(21):11877–11882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frenette PS, Johnson RC, Hynes RO, Wagner DD. Platelets roll on stimulated endothelium in vivo: an interaction mediated by endothelial P-selectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(16):7450–7454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Denis CV, Andre P, Saffaripour S, Wagner DD. Defect in regulated secretion of P-selectin affects leukocyte recruitment in von Willebrand factor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(7):4072–4077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Forlow SB, McEver RP, Nollert MU. Leukocyte-leukocyte interactions mediated by platelet microparticles under flow. Blood. 2000;95(4):1317–1323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Celi A, Pellegrini G, Lorenzet R, et al. P-selectin induces the expression of tissue factor on monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(19):8767–8771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Falati S, Liu Q, Gross P, et al. Accumulation of tissue factor into developing thrombi in vivo is dependent upon microparticle P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 and platelet P-selectin. J Exp Med. 2003;197(11):1585–1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antonopoulos CN, Sfyroeras GS, Kakisis JD, Moulakakis KG, Liapis CD. The role of soluble P selectin in the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2014;133(1):17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cherian P, Hankey GJ, Eikelboom JW, et al. Endothelial and platelet activation in acute ischemic stroke and its etiological subtypes. Stroke. 2003;34(9):2132–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inami N, Nomura S, Kikuchi H, et al. P-selectin and platelet-derived microparticles associated with monocyte activation markers in patients with pulmonary embolism. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2003;9(4):309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsui NM, Borsig L, Rosen SD, Yaghmai M, Varki A, Embury SH. P-selectin mediates the adhesion of sickle erythrocytes to the endothelium. Blood. 2001;98(6):1955–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bovill EG, van der Vliet A. Venous valvular stasis-associated hypoxia and thrombosis: what is the link? Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:527–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lopez JA, Chen J. Pathophysiology of venous thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2009;123 Suppl 4:S30–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stevenson JL, Varki A, Borsig L. Heparin attenuates metastasis mainly due to inhibition of P- and L-selectin, but non-anticoagulant heparins can have additional effects. Thromb Res. 2007;120 Suppl 2:S107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Varki NM, Varki A. Heparin inhibition of selectin-mediated interactions during the hematogenous phase of carcinoma metastasis: rationale for clinical studies in humans. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2002;28(l):53–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang JG, Geng JG. Affinity and kinetics of P-selectin binding to heparin. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90(2):309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wei M, Gao Y, Tian M, Li N, Hao S, Zeng X. Selectively desulfated heparin inhibits P-selectin-mediated adhesion of human melanoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2005;229(1):123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Belizaire RM, Makley AT, Campion EM, et al. Resuscitation with washed aged packed red blood cell units decreases the proinflammatory response in mice after hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(2 Suppl 1):S128–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoehn RS, Jernigan PL, Chang AL, et al. Acid Sphingomyelinase Inhibition Prevents Hemolysis During Erythrocyte Storage. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;39(1):331–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Matijevic N, Wang YW, Wade CE, et al. Cellular microparticle and thrombogram phenotypes in the Prospective Observational Multicenter Major Trauma Transfusion (PROMMTT) study: correlation with coagulopathy. Thromb Res. 2014;134(3):652–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matijevic N, Wang YW, Holcomb JB, Kozar R, Cardenas JC, Wade CE. Microvesicle phenotypes are associated with transfusion requirements and mortality in subjects with severe injuries. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:29338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Quan L, Ishikawa T, Zhao D, et al. Immunohistochemistry of von Willebrand factor in the lungs with regard to the cause of death in forensic autopsy. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2009;11 Suppl 1:S294–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]