Summary

The timing of behavior under natural light-dark conditions is a function of circadian clocks and photic input pathways. Yet a mechanistic understanding of how these pathways collaborate in animals is lacking. Here we demonstrate in Drosophila that the Phosphatase of Regenerating Liver-1 (PRL-1) sets period length and behavioral phase gated by photic signals. PRL-1 knockdown in PDF clock neurons dramatically lengthens circadian period. PRL-1 mutants exhibit allele-specific interactions with the light- and clock-regulated gene timeless (tim). Moreover, we show that PRL-1 promotes TIM accumulation and dephosphorylation. Interestingly, the PRL-1 mutant period lengthening is suppressed in constant light and PRL-1 mutants display a delayed phase under short, but not long, photoperiod conditions. Thus, our studies reveal that PRL-1 dependent dephosphorylation of TIM is a core mechanism of the clock that sets period length and phase in darkness, enabling the behavioral adjustment to changing day-night cycles.

eTOC

Daily behavioral patterns are determined by the integration of internal clocks and the external environment. Kula et al. find that Phosphatase of Regenerating Liver-1 acts on the clock component TIMELESS to set period length in constant darkness as well as behavioral phase under winter-like, but not summer-like, photoperiods.

Introduction

Circadian clocks enable anticipation of environmental transitions driven by the earth's daily rotation [1]. Superimposed on 24 h environmental cycles are seasonal changes in the daily photoperiod (or day length), the result of the earth’s ~23.5° tilt on its axis. A comprehensive understanding of how the clock integrates ecologically relevant sensory cues such as daily light and seasonal changes in photoperiod to ensure appropriate alignment of the clock to the 24 h environment across the year is lacking.

Drosophila genetics has revealed conserved transcriptional feedback loops as the core mechanism of timekeeping in animals [2, 3]. In flies, the bHLH-PAS transcription factor CLOCK (CLK)/CYCLE (CYC) heterodimer binds to E boxes (CACGTG) and activates period (per) and timeless (tim) transcription with a peak around dusk [4]. PER and TIM proteins transit from cytoplasm to the nucleus around midnight [5, 6] where PER inhibits CLK-CYC function [7-9]. This basic feedback loop operates in several organs and tissues.

This core loop is synchronized to light-dark cycles, in part, via CRYPTOCHROME (CRY). CRY is a blue-light photoreceptor that targets TIM for light-dependent degradation[10-13]. Light-mediated TIM degradation during the rising phase of TIM accumulation in the early night simulates delayed dusk, delaying the clock, while TIM degradation during the falling phase of TIM in the late night simulates early dawn to advance the clock.

Phosphorylation state of clock components is rhythmic [14-16] and modifying phosphorylation state can profoundly impact period length. PER and TIM proteins are modified by phosphorylation by kinases such as DBT/CKIδ/ε, SGG/GSK3β, CK2, and NEMO, modulating their localization, function and/or stability [16-21]. In a core subset of pacemaker neurons, TIM is phosphorylated by SGG and CK2 to promote nuclear localization [22, 23]. Phosphatases PP2a and PP1 counteract PER and TIM phosphorylation, respectively [15, 24]. Phosphorylation is implicated in mediating light-triggered TIM degradation [13, 25] as well as in light-independent degradation mediated by SLIMB [26] and Cullin-3 [27]. In fact, mutations in either putative human PER2 phosphorylation sites or the CK1δ kinase can dramatically affect the timing of sleep-wake in individuals with familial advanced sleep phase syndrome, further underscoring the importance of phosphorylation [28-30].

These molecular oscillators function in 150 interconnected neurons to time circadian behavior [2, 31]. In 12h light: 12h dark (LD) conditions, these clocks promote locomotor activity in advance of lights-on, termed morning anticipation, and in advance of lights-off, termed evening anticipation. The ventral lateral neurons (LNv) expressing the neuropeptide PIGMENT DISPERSING FACTOR (PDF) and the posterior dorsal neurons 1 (DN1p) are primarily responsible for morning anticipation while the dorsal lateral neurons (LNd), a single small LNv (sLNv), and the DN1p, contribute to evening anticipation [32-36]. Given their relative exclusive roles, we refer to the PDF+ LNv as the morning (M) cells and the LNd and PDF− sLNv as the evening (E) cells.

While much is known about core clock mechanisms, much less is known about how the clock adjusts to seasonal changes in photoperiod. The phase of locomotor activity depends on photoperiod [37-39]. PDF in the large LNv (lLNv) and the PDF receptor (PDFR) in E cells are important for setting evening phase under long (16:8, 20:4), but not short, photoperiod conditions [40-42]. Manipulations of PDF neuron plasticity alter photoperiod dependent changes in morning locomotor activity [43]. Flies also exhibit photoperiod-dependent network hierarchy. Under constant darkness (DD) and short photoperiod conditions, the pace of the M cell clock sets the phase of both M and E activity peaks, while the pace of the E clock only adjusts the E activity peak, indicating the dominance of the M cells [44]. Under long photoperiods, the pace of the E cell clock sets the M and E phases while speeding the M clock only advances M behavior, indicating the dominance of the E pacemaker [44]. These results are consistent with studies under constant light (LL) and DD where the sLNvs are the dominant pacemakers in DD [32, 33, 45, 46] while the LNd/DN1 are the dominant pacemakers in LL [44, 47-49], although PDF neurons may also contribute to LL period length [44]. There are likely differences in clock neuron properties (core clock components, photic responses, network connectivity) that result in photoperiod-dependent differences in M and E cell function. Yet the molecular and cellular mechanisms mediating these cell-type specific photoperiod dependent changes are unclear. Here we identify a molecular player in this process, a clock-controlled phosphatase, PRL-1, that regulates behavioral phase in a photoperiod dependent manner revealing a molecular pathway mediating the response to seasonal changes in photoperiod.

Results

PRL-1 mRNA is clock regulated specifically in PDF clock neurons

To discover novel components of the circadian clock important for rhythmic behavior, we performed an RNAi screen on 437 cycling and/or enriched genes in PDF neurons [50]. Here we focus on one of the rhythmic genes encoding the protein phosphatase, the Phosphatase of Regenerating Liver-1 (PRL-1). A prior transcriptomic report also identified PRL-1 as cycling from dissected whole brains, although with much lower amplitude than observed in purified clock neurons [51]. To confirm cycling, we isolated PDF+ LNv using fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) and performed quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) to assess PRL-1 transcript level expression. We found a robust (~8-fold) oscillation with a peak around dusk (ZT12), i.e., around the peak time of CLK/CYC-activated transcription [4] (Figure 1A). To determine if this cycling was evident in other clock neurons or in whole heads, we FACS isolated DN1p clock neurons and performed qPCR. We failed to detect any significant time-dependent changes in the expression of PRL-1 mRNA, indicating that clock control of PRL-1 is neuron-specific within the circadian clock neural network (Figure 1B). We also assessed PRL-1 transcript in whole heads where the majority of clock gene expression is derived from the retinal photoreceptors [52]. Here we also failed to identify any significant oscillations (Figure 1C), suggesting that the PRL-1 oscillations may be restricted to PDF+ LNv neurons (Figure 1A). Non-rhythmic transcription factors may have a larger role in regulating PRL-1 transcription outside of the PDF neurons. To address the mechanism of regulation in the LNv, we assessed PRL-1 transcript levels in ClkJrk and per01 mutants and found that PRL-1 levels are very low in ClkJrk and elevated in per01, consistent with the idea that PRL-1 is a CLK-activated gene (Figure 1D). In fact, chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrate that CLK directly binds to the PRL-1 locus, suggesting this regulation is direct [53]. As a cycling phosphatase, PRL-1 may provide a mechanism for cyclical phosphorylation state of core clock proteins.

Figure 1. PRL-1 mRNA cycles in PDF cells but not in DN1 cells or whole heads.

(A-C) qPCR analysis of PRL-1 mRNA expression in adult Drosophila tissues. ZT indicates Zeitgeber time. PRL-1 expression rhythms are detected in (A) FACS-isolated PDF cells (pdfGAL4 UAS-mGFP; p < 0.05), but not in (B) isolated DN1p clock cells (clk4.1GAL4 UAS-mGFP, p = 0.57), or (C) whole head tissue (p = 0.65), as determined using one way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test, n=2. PRL-1 expression in DN1p neurons (B) is ~60% of levels observed in PDF cells (A). (D) PRL-1 mRNA expression in PDF cells in wild-type (wt), per01, and ClkJrk mutants at ZT12, n=2, assessed by Student’s t-test (*** p < .001, * p < .05). All data reported as mean expression levels with error bars indicating SEM. See also Figure S1 and Table S8.

Given the cell-type specificity of PRL-1 regulation, we examined the spatial distribution of PRL-1. As a PRL-1 antibody we developed (see below) did not detect signal above background in whole-mount Drosophila brains, we analyzed the expression of a GAL4 enhancer trap (NP2526) inserted upstream (−457 bp) of the transcription start site for one of the PRL-1 isoforms (RA; Figure S1A). We found that NP2526 drives expression in circadian clock neurons, including the PDF+ LNv (Figure S1B), some LNd (Figure S1C) as well as the optic lobes and other areas of the central brain (data not shown). In addition, we generated a GAL4 line containing ~3 kb of the putative PRL-1 promoter upstream of this start site (PRL-1GAL4; −2807-+2). This PRL-1GAL4 line further validates this expression pattern with activity including PDF neurons (Figure S1D) and a subset of LNd (Figure S1E). We did not observe expression in any DN groups or LPN using either GAL4. However, our FACS data (Figure 1B) as well as the Aerts RNAseq atlas [54] indicate that Prl-1 is expressed in the DN1p group (Aerts cluster 86).

Loss or knockdown of PRL-1 substantially lengthens circadian period

To determine in vivo PRL-1 function, we assessed circadian locomotor activity in flies in which PRL-1 has been disrupted by transposon insertion (PRL-1 LL07771) or knocked down using genespecific RNA interference (RNAi). PRL-1LL07771 bears a PiggyBac transposon insertion in the 5’ untranslated region of the PRL-1 mRNA (Figure S1A). In head extracts, this PRL-1 mutant nearly abolishes PRL-1 transcript levels (Figure S1F), lacks detectable PRL-1 protein and thus is likely a protein null (Figure S1G). We will refer to this allele as PRL-101. We found that period was significantly lengthened in PRL-101 homozygotes (26.6 ± 0.2 h; Table S1; Figure 2, p < 0.001). We also tested a deletion strain, which removes PRL-1 and several flanking genes (Df(2L)BSC278, referred to as PRL-1Df) and it fails to complement this mutant phenotype (Figure 2). The finding that PRL-101/PRL-101 and PRL-101/PRL-1Df exhibit comparable phenotypes is consistent with the notion that PRL-101 is a null or a severe hypomorphic mutant (Figure 2; Table S1). To verify that the observed circadian phenotype is due to insertion of LL07771 in the PRL-1 locus, we isolated five independent precise excision lines and uniformly observed reversion of the period phenotype (Table S2; p < 0.001). To further confirm that the observed mutant phenotype is caused by loss of PRL-1 function, we utilized the available collection of FlyFos constructs from D. pseudoobscura, in which PRL-1 is highly conserved with D. melanogaster (Figure S2) [55]. We find that the D. melanogaster PRL-1 mutant phenotype was fully rescued by the D. pseudoobscura construct FlyFos051244 containing its PRL-1 locus (Table S3). In addition, we used a wild-type D. melanogaster UAS-PRL-1 transgene [56] and rescued the PRL-1 mutant period length phenotype using the panneuronal driver elavGAL4 (Table S3). We also performed tissue-specific knockdown of PRL-1 using two independent RNAi lines (VDRC 45518GD, 107836KK; GD and KK, respectively) targeting distinct regions of the PRL-1 transcript (Figure S1A) using PRL-1GAL4 and observed comparable period lengthening phenotypes as the mutant, validating the GAL4 expression pattern (Table S4). Thus, multiple independent mutant, RNAi, and rescue analyses indicate an important role for a cycling phosphatase in determining period length in Drosophila.

Figure 2. PRL-1 mutant flies exhibit a long period phenotype.

Representative double-plotted locomotor activity profiles of individual males over 4 days LD followed by 7 days constant darkness (DD). Period and rhythmic power determined from DD data using Chi-squared periodogram analysis. (A) w1118: n = 38, (B) PRL-101/+: n= 27, (C) PRL-101/PRL-101: n= 23, (D) PRL-1Df/+: n= 51, (E) PRL-1Df/PRL-101: n= 38. Period measurements displayed above panels ± SEM, and comparisons made using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test, *** p < 0.001. See also Figures S1, S2 and Tables S1,S2,S3, and S4.

PRL-1 functions in PDF clock neurons to set period length

To map the sites of PRL-1 function, we applied cell-type specific RNAi knockdown. RNAi knockdown using timGAL4 with two independent lines results in lengthened periods similar to the mutant alleles suggesting that PRL-1 function is required in clock neurons (Table S4). Restricting PRL-1 RNAi to the PDF+ LNv neurons also results in long periods, in some cases even longer than those observed in the mutant (Table S4; pdfGAL4 RNAi vs mutant: p < 0.001, Student’s t-test). In fact, this is among the strongest period lengthening phenotypes induced by RNAi that has been reported in Drosophila, similar to knockdown of the E3 ubiquitin ligase circadian trip [57]. We confirmed the efficacy of transcript knockdown in PDF neurons using qPCR (Figure S1H). We also find that blocking RNAi expression in the PDF+ LNv using pdfGAL80 strongly blocks the period lengthening effects of timGAL4 (Table S4; p < 0.01, Student’s t-test). Thus, specific clock control of PRL-1 in PDF neurons is accompanied by PRL-1 function in these neurons crucial to setting period length. Notably, Prl-1 overexpression in clock neurons also modestly lengthens period (0.4 h compared with GAL4 control, Table S4, p < 0.05), similar to loss vs. gain of function for other circadian genes such as per [58] and CK2alpha [19, 59].

PRL-1 mutants exhibit allele-specific interactions with tim and per

To identify potential core clock molecular targets of PRL-1, we performed genetic interaction experiments focusing on PRL-101 in combination with period-altering missense tim and per alleles. Non-additive genetic interactions are prima facie evidence that two genes operate in a single pathway, consistent with a potential enzyme-substrate relationship. For tim, we examined semi-dominant missense alleles, timS1 [60] and timUL [61] (Figure S3, Table S5). Typically, period altering mutants exhibit multiplicative effects where period effects are lengthened or shortened by a fixed percentage [60]. PRL-1 mutants lengthen period by ~8% over controls and exhibit the expected multiplicative period lengthening effects with timUL, but not timS1. PRL-1 homozygotes in combinations with either timS1 heterozygotes or homozygotes (25.5h-26.5h) exhibited period lengths comparable to PRL-101/PRL-1Df mutants alone (25.8h) and significantly longer than timS1 homozygotes (~21 h; 24% lengthening) or heterozygotes (~22 h; 15-21% lengthening; Table S5). In fact, timS1 fails to shorten period in a PRL-1 mutant background. As timS1 was not previously molecularly characterized, we sequenced the timS1 locus and identified two missense mutations in established functional domains of TIM, resulting in an E846K change in the PER interaction domain and M1284I in the cytoplasmic localization domain (Figure S3) [62].

We also examined genetic interactions with the classical perS and perL alleles. In these cases, we observed modest but significant deviations from the prediction. The effects of PRL-1 loss-of-function is exaggerated in a perS background lengthening period by > 3 h (~19%), while its effects are reduced in a perL background lengthening period by just ~1 h (3-4%; Table S5). Taken together, these data suggest novel interactions between PRL-1, per, and tim.

PRL-1 affects TIM levels and localization in PDF+ sLNv Master Pacemaker Neurons

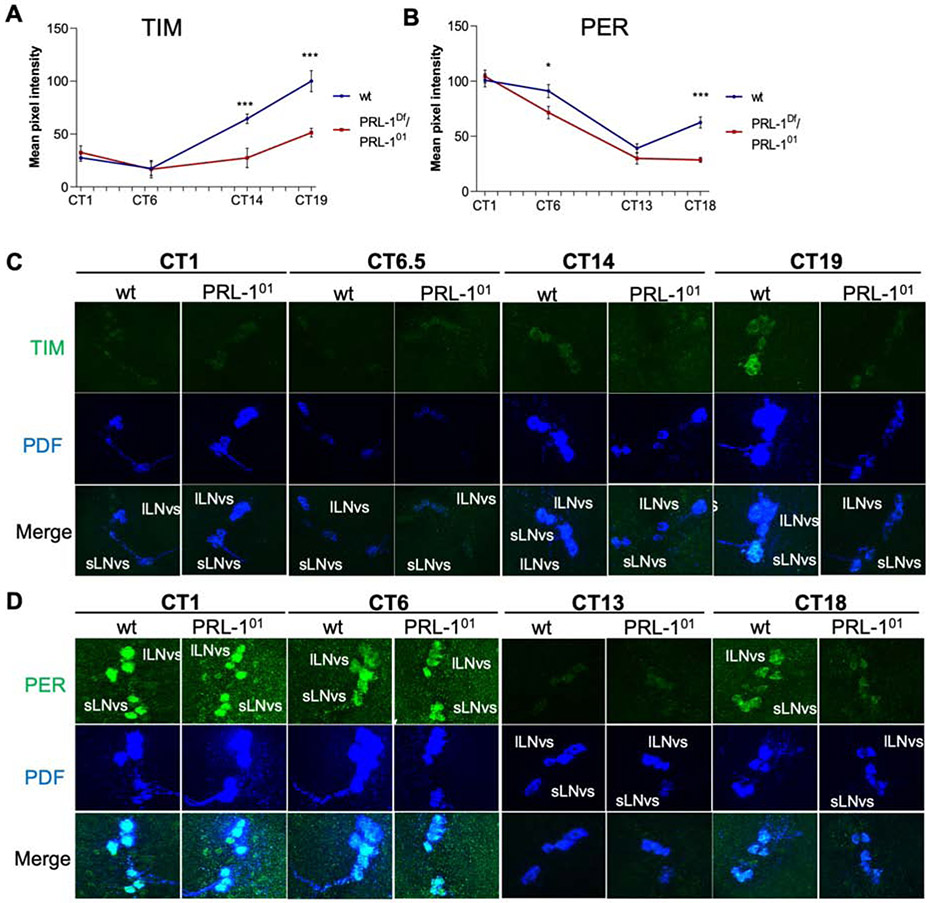

Given the allele-specific genetic interactions with per and tim, we hypothesized that PRL-1 may target and regulate levels of PER and/or TIM proteins, key elements in the negative feedback loop of the Drosophila clock. We assessed PER and TIM levels in the PDF+ sLNv across the first day of DD (DD1) after LD entrainment. We observed that loss of PRL-1 resulted in a ~50% reduction in TIM at Circadian Time (CT) 14 and 19 (Figure 3A,C; p < 0.001). PER levels were also decreased ~50% at CT18 (p < 0.001) in PRL-1 mutants but no significant changes were observed in PER at CT13 between wild-type and PRL-1 mutants (p = 0.18); Figure 3B,D).

Figure 3. PRL-1 more strongly affects TIM accumulation relative to PER in the sLNv.

Quantification (A,B) and representative images (C,D) of clock protein expression in wild-type (wt) vs. PRL-1 mutants (PRL-101/PRL-1Df) in adult Drosophila brains. (A-B) Quantification of TIM (A) and PER (B) levels in sLNv neurons under DD1 conditions. CT indicates circadian time. Plots report average intensity and error bars indicate SEM. Statistical comparisons made using Student’s t test (*** p < .001, * p < .05). Number of cells analyzed: (A) CT1: 49-56, CT6.5: 24-25, CT14: 29-47, CT19: 37-5; (B) CT1: 57-85, CT6: 50-59, CT13: 60-49, CT18: 63-62. (C-D) Representative images showing (C) TIM or (D) PER (green) with PDF (blue), and merged images in co-labeled sLNv and lLNv neurons in wild-type and PRL-1 mutants. See also Figures S3 and S4 and Table S5.

We also assessed timed TIM and PER nuclear localization across the subjective night when PER and TIM transition from cytoplasm to nucleus (CT17-24; Figure S4) [5, 6, 63]. PER/TIM protein nuclear entry occurs at a well-defined time window and is thought to be an important determinant of circadian period [64]. As expected, we observed increasing nuclear localization in the late night vs. early night in wild-type flies for TIM (Figure S4A, B; CT23 v. CT17; X2 test, p<0.001) and for PER (Figure S4C,D; CT24 v. CT20; p<0.001). We did not observe any significant difference in TIM subcellular localization between wild-type and PRL-1 mutants at CT17 or CT19, when TIM is predominantly cytoplasmic (Figure S4A, B, p >= 0.55). Later during the subjective night (CT21 and CT23) while we observed TIM transitioning to the nucleus in wild-type, we found that TIM remained predominantly cytoplasmic in PRL-1 mutants (Figure S4A, B; X2 test, p<0.001). As PRL-1 mutants display a ~2 h longer circadian period we expect a ~2 h delay in molecular oscillations. Our finding that TIM localization at CT23 in PRL-1 mutants is comparable to wild-type 4 h earlier at CT19 suggests that the TIM effects are larger than expected and not merely through the effects of PRL-1 on circadian period.

At CT20, PER subcellular localization was indistinguishable between wild-type and PRL-1 mutants (Figure S4C,D, X2 test, p = 0.75). However, by CT22 we found that in most wild-type sLNv, PER was distributed in both nucleus and cytoplasm while about half of PRL-1 mutant sLNv still had PER primarily localized to cytoplasm (Figure S4C, middle panel, 4D; X2 test, p < 0.001). Two hours later, at CT24, the vast majority of wild-type cells displayed PER localized in cytoplasm/nucleus or nucleus (Figure S4C; X2, p < 0.001). On the other hand, only about 70% of PRL-1 sLNv showed cytoplasmic/nuclear PER localization and in 30% of cells PER was still cytoplasmic, which is comparable to wild-type distributions 2 h earlier at CT22 (p < 0.001). Thus the 2 h shift in the timing of PER nuclear localization roughly mirrors the 2 h period lengthening in PRL-1 mutants, suggesting effects on PER may be indirect via the clock (i.e., any clock regulated process should be shifted by this amount). Thus, during the early and late night periods, respectively, loss of PRL-1 has effects on TIM, but not PER, levels (early night) and nuclear localization rhythms (late night).

PRL-1 associates with and dephosphorylates TIM

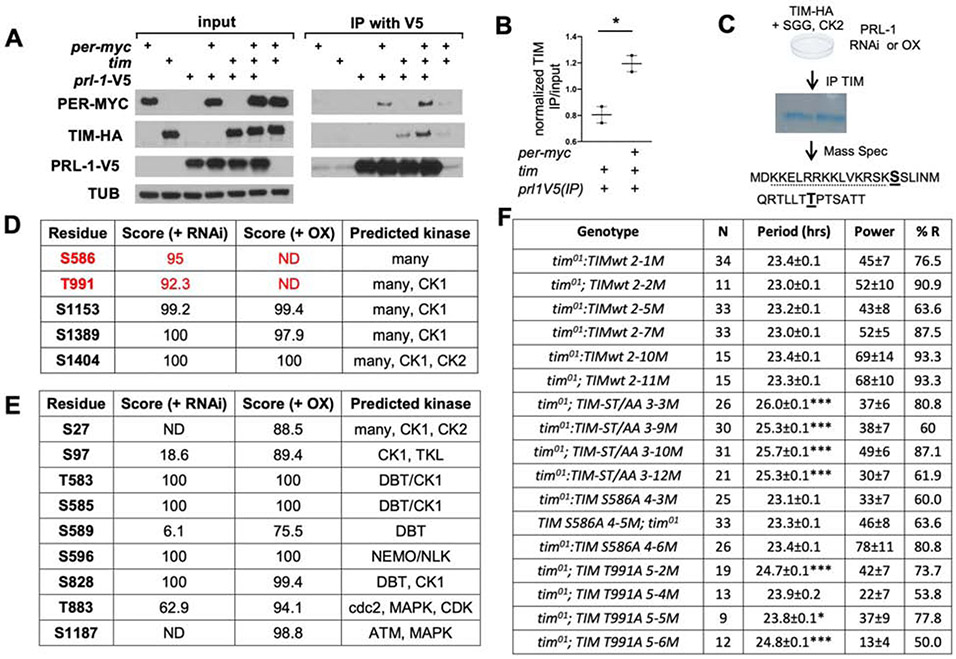

We next asked if the effects of PRL-1 on TIM and/or PER are direct. To investigate whether PRL-1 forms a complex with PER/TIM proteins, epitope-tagged PER-MYC, TIM-HA and PRL-1-V5 were transiently transfected into Drosophila S2 cells and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-V5 beads to pull down PRL-1. We found that PRL-1 co-immunoprecipitated with both PER and TIM when co-expressed (Figure 4A). We did observe an increase in PRL-1/TIM coimmunoprecipitation with PER co-expression (p < 0.05; Fig. 4B); however, a more systematic assessment will be needed to substantiate this result.

Figure 4. PRL-1 interacts with PER and TIM in S2R+ cells and selectively dephosphorylates TIM.

(A) Western blot analyses of Drosophila S2R+ cell extracts transfected with the constructs indicated. Extracts assayed directly (left panels) or immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-V5 (right panels) followed by blotting with anti-MYC, anti-TIM, anti-V5 or anti-TUBULIN (TUB). (B) Quantification of TIM IP/ input levels, comparing co-transfection of tim-HA with Prl-1-V5 alone vs. Prl-1-V5 and per-MYC, n= 2. (C) Schematic of IP and mass spectrometry (MS) analysis performed on S2 cells transfected with TIM-HA, GSK3β, and CK2, in the presence of PRL-1 knockdown (RNAi) or overexpression (OX). Two putative PRL-1 dephosphorylation sites identified on TIM using this analysis indicated in bold. Dotted line represents TIM nuclear localization signal (NLS) sequence. (D-E) Probability scores (max 100) for phosphorylation of specific residues in TIM (D) or PER (E), as determined from MS data using PhosphoRS [95]. (C) List of differentially phosphorylated sites in TIM protein in PRL1 OX vs. RNAi. n=2, data shown for one experiment. Peptide coverage 42.9 (RNAi) and 40.8 (OX) for this experiment. (D) No PER sites identified as dephosphorylated by PRL-1 using a similar approach, peptide coverage 34.1 (RNAi) and 44.0 (OX), n=1. (F) DD locomotor rhythmicity analysis in tim01 mutants containing wild-type (wt) or phosphosite mutant TIM rescue constructs. ST/AA strains contain both the S586A and T991A mutation. ‘N’ indicates number of flies analyzed; ‘%R’ refers to percentage of rhythmic flies. Period and power shown as average ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significant difference between wt and phosphosite mutant rescue (* p< 0.05,***p < 0.001). See also Figures S3 and S5.

To determine if PRL-1 can dephosphorylate either PER or TIM, we co-transfected TIM-HA and established TIM kinases, SGG [22, 23] and CK2 [20, 22, 65]. In the case of PER, we co-transfected PER-MYC with the established PER kinase DBT [66-68]. In each case, cells transfected with either PRL-1 for overexpression or depleting PRL-1 using PRL-1 RNAi were analyzed to assess PRL-1 dependent effects (Figure 4C, Figure S5 for PRL-1 knockdown assessment). PER or TIM were immunoprecipitated and then subjected to mass spectrometry. In the case of TIM, we identified 5 phosphorylation sites of which 2 were absent in a PRL-1 dependent manner (Figure 4D). One site (S586) is immediately adjacent to the TIM nuclear localization signal, S586, while the second site, T991, is close to PER interacting domain (Figure 4D, Figure S3). In the case of PER, we identified 9 phosphorylation sites (Figure 4E), several of which have been identified as DBT phosphorylation sites by consensus prediction and/or subsequent experimental testing [68-70] or are sites for other known circadian kinases [16]. Of note, a number of these sites were increased in phosphorylation (i. e., S27 and S1187) in the presence of PRL-1 suggesting that PER is not a direct target of PRL-1 dephosphorylation. Despite a larger number of identified phosphorylation sites on PER, none of them were dephosphorylated in a PRL-1 dependent manner. As there are other kinases that can phosphorylate PER (e.g., NEMO[16]), we cannot rule out the possibility that PER is an in vivo PRL-1 substrate. Nonetheless, these experiments support the idea that TIM is a direct substrate of PRL-1.

To determine the function of TIM phospho-sites, we generated transgenic flies using a tim construct harboring S586A and/or T991A mutations (double ST/AA or single S/A, T/A) under control of the tim promoter. In a tim01 background, independent insertions of wild-type tim rescue with a ~24 h period while independent inserts of tim transgenes bearing mutations of both sites to non-phosphorylatable alanines (ST/AA) and the T/A site significantly lengthens circadian period (Figure 4F). The notion that enhancing phosphorylation (e.g., by loss of PRL-1, in this case, or mutation to a phosphomimic E or D) and blocking phosphorylation (by mutation to alanine) result in similar period-altering phenotypes is not unprecedented [59].

PRL-1 functions mediate phase responses to light pulses during the middle of the night

Given the allele-specific genetic interactions with timS1 and the role of TIM in mediating phase responses to short light pulses [12, 71-74], we performed anchored phase response curve (PRC) experiments in PRL-1 mutants in which short light pulses of light are delivered at different times at night under LD conditions and the subsequent phase change is assessed under constant conditions. Wild-type Drosophila may contain two natural tim alleles with differential light sensitivity, and we confirmed that both our wild-type strain and the PRL-1 mutant contain the more light sensitive short-length isoform (s-tim) [75]. After delivering 15 min light pulses to wild-type and PRL-1 mutants, both late night phase advances and early night delays were roughly normal except in a narrow midnight window (ZT19-20). Where wild-type flies show little shift or a modest phase advance as expected during this window, PRL-1 mutants display surprisingly large phase delays (~8 h, Figure S6A). Other long period mutants such as timUL, dbtL, and perL, do not show this phenotype, indicating generic period length is not responsible for the phenotype [61, 76, 77]. Examination of the slope of the phase transition curve indicates the wild-type and PRL-1 slopes are comparable (wild-type 1.2; Prl-1 mutant 0.9) and consistent with a Type I PRC (Figure S6B) [78]. Interestingly, PRL-1 mutants do not show a significant phase shift phenotype on the first day after the light pulse (Figure S6C). However, they display robust phase delays on days 2 and 3 after the LP (Figure S6C). These delayed responses to light pulses have been termed “after effects” [79] and might be due to neural network responses after the acute phase change [80, 81]. Nonetheless, these data suggest that PRL-1 functions specifically during the middle of the night to mediate phase responses to light.

PRL-1 effects on period and phase are suppressed by constant light and in long photoperiods

Given the strongly altered response to light pulses we decided to examine whether the PRL-1 mutant phenotype also altered the response to constant light (LL). Constant light suppresses rhythmicity in wild-type flies, but not in cry photoreceptor mutants [82]. For the cry mutant condition, we used trans-heterozygotes of a cry knockout allele (cry01; [83]) and a missense mutant that disrupts the FAD binding pocket critical for CRY photoresponses (cryb; [11]). We confirmed that cryb/cry01 trans-heterozygotes, unlike their wild-type counterparts, are robustly rhythmic in LL with near 24-25 h periods (Table S6). PRL-1 mutants in a cry+ background exhibit LL induced arrhythmicity (Table S6). Under DD conditions, PRL-1; cry double mutants have a recessive long period (26.4 h) (Figure 5, Table S6), which is comparable to PRL-1 mutants in a wild-type background. Thus, loss of cry function per se does not impact nor is epistatic to the PRL-1 mutant DD phenotype similar to perS [11]. However, in LL in a cry mutant background, loss of PRL-1 fails to lengthen period and in fact, the period is comparable to or modestly shorter than cry single mutants (Figure 5, Table S6, p < 0.001). Thus, the PRL-1 period lengthening phenotype is suppressed by constant light.

Fig 5. PRL-1 effects on period are absent under LL.

Representative double-plotted activity profiles of PRL-1; cry double mutants vs. single mutant controls under 12H light:12H dark (LD) followed by either 7 days DD or 7 days LL as indicated. A) cryb/cry01, B) PRL-1Df/PRL-101, C) PRL-101/+; cryb/cry01, D) PRL-1Df/PRL-101; cryb/cry01. Number of flies examined DD/LL: A) 51/48, B) 35/22, C) 24/19, D) 58/32. See also Figure S6 and Table S6.

To determine if this light-dependence extended to more ecologically relevant conditions and in flies with an intact CRY photoreceptor, we examined PRL-1 mutant behavior under short (winter-like) and long (summer-like) photoperiods. While Drosophilids are thought to have evolved from tropical areas [84], natural populations of D. melanogaster have been collected from Northern latitudes such as Umeå, Sweden (latitude 63 degrees N) [85]. Here, flies were subjected to 6L:18D (winter; for example January 19th in Umeå) or 18L:6D (summer; for example May 13th in Umeå). Wild-type flies adjust the phases of morning and evening behavior depending on the times of lights-on and lights-off. Under short photoperiods, PRL-1 mutants display a delay of both morning and evening activity phase in comparison to controls (Figure 6A; Table S7). However, under 12L:12D and 18L:6D morning anticipation is not evident and is likely masked by the lights-on peak (Figure 6B,C). When we examined morning onset in DD1, we found that the onset of morning activity is delayed in 6:18 and 12:12 conditions (Table S7). However, when we examined evening phase (onset of activity) under 12:12 and 18:6, we found that PRL-1 mutants were indistinguishable from wild-type controls (Fig 6B,C). This was surprising given that petL mutants still display a delayed evening phase and pers mutants exhibit advanced evening phase in 12:12 LD cycles [86, 87]. Thus, PRL-1 is necessary for setting evening behavioral phase in a photoperiod dependent manner, indicating an essential role in seasonal adaptation.

Figure 6. PRL-1 mutants display delayed phases of morning and evening activity under winter, but not summer photoperiods.

Normalized group average activity profiles for (A) wild-type, (B) PRL-1Df/+, and (C) PRL-101/ PRL-1Df mutant flies in either 6L:18D (winter), 12:12 (intermediate), or 18L:6D (summer) photoperiods as indicated. Red arrows indicate morning onset of activity for conditions/genotypes in which morning anticipatory behavior detected (see Table S7). Blue arrows indicate time of evening activity offset (for 6L:18D) or onset (for 12L:12D and 18L:6D). Error bars indicate SEM. n= 36 to 153 per genotype. See also Figure S6 and Table S7.

Knockdown of human PRL-1 orthologs lengthens circadian period

To determine if the function of PRL-1 is evolutionarily conserved in mammals, we also used siRNA to knock down expression of mammalian PRL-1 orthologs (PTP4a1, PTP4a2, and PTP4a3) in human osteosarcoma U2OS cells expressing a circadian Per2∷luc reporter (Figures 7A,B; Figure S7). Notably, PTP4a1 mRNA has been shown to exhibit rhythmic expression in many mammalian tissues including the SCN[88], brainstem, liver, and kidney, while PTP4a2 shows rhythmic expression in the liver, lung and SCN and PTP4a3 expression cycles in the heart (CircaDB; [89]). These findings suggest clock control is a conserved feature of these phosphatases. In U2OS cells expressing the Per2∷luc reporter, we observe robust period lengthening of luminescence rhythms using siRNA targeting the mammalian clock component Cry2 (Figures 7A,B, S7). Notably, knockdown of any individual PTP4a ortholog using siRNA did not alter period length. However, siRNA knockdown of all three PTP4a genes substantially lengthens period (~26h) (Figures 7A,B, S7), indicating the function of this phosphatase is widely conserved in setting period length.

Figure 7. Knockdown of human PRL-1 orthologs in U2OS cells lengthens period of per2∷luc rhythms.

A) Traces of luciferase reporter activity in mammalian U2OS cells expressing Per2∷luc, assayed for 6 days after synchronization. Cells transfected with siRNAs as indicated. B) Quantification of period length in transfected U2OS per2∷luc cells, as determined using LumiCycle analysis software (Actimetrics) from Day 1.5-4.5; n=4 for all samples except siCry2 (n=3) ( *** one-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s post-hoc test, p < 0.001). See also Figure S7 and Table S8.

Discussion

Here we have identified a novel circadian clock gene PRL-1 that mediates the behavioral response to changes in photoperiod. Circadian regulation of this phosphatase provides a mechanism for mediating rhythmic phosphorylation, a widely conserved feature of circadian clocks. Reduction or loss-of-function in PRL-1 can induce potent effects on circadian period length even larger than those caused by reduction of canonical clock genes. These effects are widely conserved evident even in human cells. PRL-1 selectively dephosphorylates and suppresses the accumulation of the light sensitive clock component TIM. PRL-1 affects behavioral phase in short but not long photoperiods, revealing a novel mechanism for appropriate timing across ecologically relevant photoperiods.

Our data suggest PRL-1 plays an especially important role in setting period length comparable to or exceeding those of the canonical core clock components. RNAi knockdown of PRL-1 with two independent RNAi lines results in among the strongest RNAi-induced period-altering phenotypes seen in Drosophila with period lengths exceeding 28 hours (Table S5). Interestingly, period effects are smaller in the putative null allele of PRL-1 (~26 h) and with broader (e.g., timGAL4) PRL-1 knockdown suggesting that PRL-1 may have distinct and even antagonistic period setting roles in different clock neurons. The other clock genes with RNAi effects comparable to PRL-1 are the regulatory beta subunit of the protein kinase CK2 [90] and the E3 ubiquitin ligase circadian trip [57], further highlighting the role of post-translation modifications in determining period length.

Several lines of evidence support the model that TIM is an in vivo target of PRL-1. PRL-1 mutants exhibit non-additive effects with a tim allele, timS1, suggesting PRL-1 and tim function within the same pathway. Non-additive genetic interactions with specific alleles can reflect functional, even direct biochemical, interactions e.g., such as between per and tim [77] and between per and Dbt [76]. Simple additive effects on period length with timUL flies probably reflects the fact that TIMUL is stable and exhibits prolonged nuclear localization [61]; therefore stabilizing effects of timUL are not counteracted by the destabilizing effects of PRL-1 mutation during the rising phase of TIM accumulation. Loss of PRL-1 results in substantially reduced and delayed nuclear accumulation of TIM during the first day of DD. These effects are much larger than those simply predicted based on the lengthened period and much larger than effects on PER, suggesting a selective effect on TIM in vivo. Using PRL-1 overexpression and knockdown in clock-less Drosophila S2 cells, we found that PRL-1 dephosphorylates TIM but not PER. Given that PRL-1 mRNA expression peaks around dusk, we propose that PRL-1 accumulation during the early night results in TIM dephosphorylation, stabilization, and nuclear localization.

Strikingly, period lengthening is evident even after siRNA knockdown of all three highly conserved human orthologs of PRL-1, PTP4a-1, −2, and −3, in human U2OS cells, suggesting a widely conserved role in period determination. Like fly PRL-1, mammalian orthologs of PRL-1 also undergo rhythmic expression in many tissues [88, 89]. PTPs may also function via TIM. Mammalian TIM interacts with CRY1 as well as PER1/2 [91], is involved in CLOCK-BMAL1 repression of CLOCK-BMAL1 activation and sets period length. Mutation of human TIMELESS also results in familial advanced sleep phase syndrome perhaps via altered light responses [92]. Thus, PTP4 action may similarly function to regulate TIM in mammals.

The connection between PRL-1 and photosensitive TIM suggested that PRL-1 may function to mediate clock responses to light. PRL-1 mutants exhibit a light dependent and CRYindependent period phenotype. To examine rhythms in LL, we examined PRL-1 mutant period length in a cry mutant background in which flies exhibit free-running rhythms. These flies retain their long periods in DD. On the other hand, in LL they exhibit period lengths comparable to their PRL-1+ controls. Thus, light can act independently of CRY photoreception to compensate for the PRL-1 mutant period lengthening. We hypothesize that signaling through the visual system could accomplish this.

The finding of LL dependent period phenotypes led us to examine the role of PRL-1 in mediating behavioral adaptations to seasonal changes in photoperiod. PRL-1 mutants display delayed morning and evening activity phases under short (6:18) photoperiods. In contrast, they have no alteration of evening activity phase under long (18:6) photoperiods. These photoperiods approximate those that would be experienced by wild Drosophila melanogaster at more extreme latitudes (e.g. >55° N; see[93]). We hypothesize that PRL-1 defines a molecular pathway through which the clock adjusts behavioral phase in response to different photoperiods.

The phenomenon of photoperiod-dependent network hierarchy suggests that M and E cells differ in their core clock properties, responses to light, and/or their network connectivity. We hypothesize that PRL-1 represents such a specialization of M cell clocks that enables the appropriate behavioral adjustments to different photoperiods. PRL-1 exhibits robust PDF neuron specific cycling and PRL-1 knockdown selectively in PDF neurons substantially lengthens period. The finding of period phenotypes in DD and not LL is also consistent with M cell specific function [47, 48]. Our findings of photoperiod dependent effects in PRL-1 mutants could reflect enhanced coupling between LNv and CRY-negative DN1p in short photoperiod, consistent with prior findings of light intensity dependent sLNv-DN1p coupling [36]. Under this model, selective PRL-1 dependent changes in M cell phase are propagated to E cells in a photoperiod dependent manner as observed for other M cell specific changes [44]. Of note, other core clock components have been identified with differential functions between M and E cells [94], including those involved in TIM phosphorylation [22], suggesting a wider role for specialized core clock components in M and E cells. It will be of interest to determine if M or E cell specific mechanisms also function to control behavioral adaptations to different photoperiods and, if so, how they work with respect to PRL-1.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Ravi Allada (r-allada@northwestern.edu).

Materials Availability

Drosophila strains and antibodies generated in this study are available upon request.

Data and Code Availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data generated in this study are available through the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [96] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD020986.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Drosophila strains

Drosophila strains were raised and maintained on standard agar food at 22° to 25° C in light:dark conditions. Behavior and immunofluorescence experiments were performed using adult males, while most FACS sorting experiments used an equal mix of male and female adults. pdfGAL4 [45], Clk4.1GAL4 [34, 35], elavGAL4 [97], timGAL4-62 [98], pdfGAL80 [32], per01 [99], perS [99], perL [99], tim01 [100], timS1 [60], timUL [61], cryb [11], cry01 [83], ClkJrk [101], and UAS-PRL-1 [56] have been described previously. Df(2L) BSC278, UAS-mGFP, and w1118 iso31 were obtained from Bloomington Drosophila stock center (BDSC; Bloomington, IN). PRL1{LL07771-Pbac}and pGAWB{NP2526} were obtained from the Drosophila genetics resource center (DGRC; Kyoto). PRL-1 RNAi and UAS-dcr2 strains were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center (VDRC; Vienna).

Cell lines.

U2OS cells (ATCC) stably transduced with the Per2-luciferase reporter [102] were grown in regular Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Corning; MT10013CV) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin. All cells were grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere and regularly checked to be mycoplasma-free. The sex of U2OS cells is female. The cell line is regularly authenticated by measuring luminescence levels using the Lumicycle luminometer (Actimetrics). The clonal lines are morphologically indistinguishable and represent the average period length from parental cell line as described [102]. Drosophila Schneider 2 cells (S2-R+) (Drosophila Genomics Resource Center), which are derived from Oregon R late embryonic stage male tissue, were cultured in Schneider’s medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1X Penicillin-Streptomycin-Glutamine at 25°C

METHOD DETAILS

Generation and genotyping of fly strains

To generate PRL-1GAL4 strains, the BAC 21C10 genomic clone (Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute) was used as a PCR template to amplify a PRL-1 promoter region. The construct used to produce PRL-1GAL4 encompassed a 2.8kb region upstream of the transcription start site of PRL-1-RA and PRL-1-RC isoforms (EcoR1-BamH1). This PCR fragment was cloned into pPTGAL4 plasmid using standard procedures. Transgenic flies were obtained by injecting the yw flies (BestGene, Inc). For tim transgenic strains, PCR mutagenesis was performed using an existing construct containing 4.3 Kb of tim upstream region fused to tim cDNA [103]. Wild-type and phospho-mutant constructs were then subcloned into pCaSpeR4 and injected into tim01 embryos (Bestgene, Inc.). PRL-101 excision lines were established through excision of the LL07771 P element using standard procedures, which yielded 5 independent precise excision strains [104, 105]. Precise excisions and non-excised controls were verified by assessing 3xP3-DsRed epifluorescence, which is associated with the LL07771 insertion, followed by genomic PCR and sequencing. Genotyping of tim isoforms (s-tim, ls-tim) in wild-t6ype and PRL-1 mutant strains was performed as described in [106].

Behavioral activity monitoring

Drosophila locomotor behavioral assays were performed as described previously [107, 108]. Briefly, strains and crosses were raised at 25° C and approximately 0-8 day old adult males were loaded into Drosophila activity monitors (Trikinetics). For initial RNAi behavioral screen, 437 genes were chosen based on their previous identification as cycling (1.8 fold expression difference over 3-4 LD timepoints) or enriched in PDF-positive LNv neurons (>= 2 fold increase over elavGAL4) [50]. For PRL-1 complementation assays, PRL-101 and PRL-1Df strains were used as mothers in the heterozygous control crosses to ensure that these strains did not harbor period altering mutations on the X chromosome. Behavioral assays were performed for 5 days Light:Dark conditions (LD) followed by 7 days constant darkness (DD). Daily LD activity patterns were analyzed from 12L:12D (standard), 6L:18D (winter-like), and 18L:6D (summer-like) photoperiods. For short (6L:18D) and long (18L:6D) photoperiod assays, flies were raised at 12L:12D conditions and the lights-off time was advanced or delayed by 6 H on the day of behavior loading. Morning and evening phase assessments under LD were determined similarly to [107] with some modifications. Data were normalized and averaged from the last two days of light:dark conditions to allow for phase adjustment to altered photoperiod regimes. For morning onset phase assessments, the largest two-hour increase in activity of individual flies was determined over ZT 18-24 for 12L:12D conditions, while a larger window (ZT 14-24) was considered for 6L:18D conditions. Phase was not determined for conditions in which morning anticipatory behavior was not observed using previous established methods [107].For evening phase assessment, evening onset was measured by determining the largest two-hour activity increase in individuals over the last 7 hours of light phase for 12L:12D and the last 12 hours of light phase for 18L:6D. For 6L:18D conditions, we determined the timing of evening offset by identifying the largest 2 hour decrease in individual activity between ZT 7-13.5. For DD1 morning phase, individual fly activity profiles were smoothed with a low-pass Butterworth filter to remove periodicities < 4hr [109]. The morning peaks from the smoothed profile were identified as local maxima, and onset values were calculated as the time of the day when 50% of the peak activity was attained prior to the peak time, which was previously shown as a reliable indicator of phase [110]. The time windows considered for DD1 morning peak varied depending on photoperiod: for 6L:18D, ZT 15-CT 3 and for 12L:12D, ZT 20-CT6. Free-running rhythmicity analysis was performed over 7 days constant darkness (DD) or constant light (LL) using Chi-squared periodogram analysis (Actimetrics) as previously described [107]. Power measurements indicate chi-squared rhythmic power minus significance (0.01), and rhythmic flies are defined as those with power measurements >= 10.

FACS and qPCR

GFP positive cells were sorted from adult Drosophila brains and subject to qPCR as described previously [107, 108], with PDF+ LNv neurons labeled by pdfGAL4 UAS-mGFP and DN1p neurons labeled by clk4.1GAL4 UAS-mGFP. The following primers were used to quantify PRL-1 mRNA expression: F1: ACAAGGCATTACCGTCAAGG, R1: AAGCCCAATTCAATCAGTGC. Expression was normalized to calmodulin as described before [108]. RNA was extracted from whole fly heads using RNeasy Mini kit following manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen). 200 ng of total RNA were reverse transcribed using oligoT7 primer and SuperScript III (Invitrogen).

Immunostaining

PER, TIM, and PDF immunostaining was performed as described previously [107]. Mouse anti-PDF (1:800, DSHB), rabbit anti-PER (1:8000) [111], and rat anti-TIM (1:4000) [25] were used as primary antibodies. The following secondary antibodies were used: anti-mouse Alexa594 (1:800, Invitrogen), anti-rabbit Alexa488 (1:800, Invitrogen), and anti-rat Alexa488 (1:800, Invitrogen) for co-labeling of PDF and PER or PDF and TIM. Brains were imaged on Nikon E800 laser-scanning confocal microscope using a 60x A 1.4 N. A. objective with laser. Channels were scanned sequentially. Confocal Z-stacks were analyzed in NIH ImageJ. Sample sizes in the legends indicate number of cells examined per genotype. Randomly chosen background measurement from each imaged brain hemisphere was subtracted from PER/TIM fluorescence intensities for cells in that hemisphere.

Light pulse experiments

Anchored phase response curve assessments were performed similar to previous reports [112, 113]. Adult males were maintained in activity monitors for 4 days under standard 12:12 LD conditions. On the fifth day LD, a 15 minute light pulse (~1600 lux) was performed at indicated time-points on the last dark phase before release to DD. Phase difference was quantified on day 2 and 3 of DD between light-pulsed and non-pulsed controls run in parallel experiments. Phase differences were then averaged between experiments.

PRL-1 antibodies

A full length PRL-1 fragment (SpnI-KpnI) was subcloned into 6xHisTag containing pQE-80L vector. Protein expression was induced with IPTG (Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside) following manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen). Purified PRL-1 protein from bacterial cells was used to immunize guinea pigs (Cocalico Biologicals).

S2 cell transfection and immunoprecipitation

S2R+ cells were transiently transfected using Effectene (Qiagen) according to manufacturers’ instructions. For each transfection, combinations of 0.5 μg pAct-3xFlag-6xHis-per-6xmyc [114], pAct-tim-3xHA[115], pAct-prl-1-V5 were used. PRL-1 cDNA clone RE55984 (DGRC, Indiana) was used for PCR amplification and whole-length PRL-1 cDNA fragment was subcloned with NotI and XbaI into pAc-V5 vector. The cloning was verified by restriction digest and sequencing of the insert. Appropriate amount of empty control plasmid, pAc-V5/His was added to each transfection to complete the total amount transfected vectors to 1.5 μg. Two days after transfection, cells were harvested, washed in PBS and homogenized in EB2 solution (20Mm Hepes pH 7.5, 100mM KCl, 5% glycerol, 5mM EDTA, 1mM DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100, 25mM NaF, 0.5mM PMSF) with the addition of complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2 and 3 (Sigma). 1/14th of lysates were separated for input analysis. The rest of the extracts were incubated with 30μl anti-V5 agarose resin (Sigma) for 4 hours at 4°C with gentile rotation. After a 10 min wash with EB2 solution, bound proteins were eluted by incubating the beads in 2X SDS sample buffer for 5 min at 100°C. Inputs and eluates were subjected to immunoblotting using 4-15% SDS polyacrylamide gels in the presence of following antibodies with indicated dilutions: mouse anti-TUBULIN (DSHB), 1:10000; mouse anti-V5 (Invitrogen), 1:5000; mouse anti-c-MYC 9E10 (Sigma), 1:3000, and guinea pig anti-TIM 1:3000 [116]. Appropriate HRP-conjugated IgG secondary antibodies were used at a 1:2000 dilution (GE Healthcare). Quantitation of TIM levels after PRL-1 immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed using densitometry analysis (ImageJ). To control for exposure time, protein measurements were divided by the averaged of all samples within blots. IP protein levels were divided by input/tubulin, followed by subtraction of IP background (no PRL-1). Relative TIM levels were determined for tim, PRL-1 cotransfection versus per, tim, PRL-1 cotransfection (n=2). Statistical comparisons were made using Student’s t-test.

Mass Spectrometry for Phosphopeptide Analysis

To test if TIM and/or PER are substrates of PRL-1, we transfected S2 cells with kinases under an inducible metallothionein promoter, GSK3β and CK2 in the case of TIM and DBT in case of PER, epitope tagged clock components PER and TIM, and either PRL-1 or PRL-1 dsRNA each driven by the Act5C promoter (Effectene transfection reagent, Qiagen). PRL-1 RNAi was synthesized as in [117] using the following primers spanning a full length PRL-1 cDNA following T7 based transcription: T7_F1 TAATACGACTCACTATAGGATGAGCATCACCATGCGTCAA, T7_R1 TAATACGACTCACTATAGGTTGCACAGAACATGAATT. Two days after transfection, kinase expression was induced with 500 μM copper sulfate for 20 hours. Cells were treated with MG132 to prevent protein degradation, and cycloheximide to stop de novo protein synthesis, and harvested 4 hours later. PER or TIM were subjected to immunoprecipitation using agarose beads and extracts were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels. PER or TIM bands were excised and subjected to mass spectrometry to identify changes in phosphorylation sites at the Northwestern Proteomics core. Data processing was carried out in Proteome Discoverer v. 1.4. LCMS raw files were searched against the Drosophila SwissProt database using the Sequest algorithm and a 1% FDR cutoff was applied at the peptide level. The PhosphoRS algorithm was used to qualitatively predict phosphorylation sites by comparing experimental spectra with theoretical values and assigning a probability score for each potential site [95]. Only sites with 75% or better localization probability were considered for further analysis.

siRNA and Luminescence Analysis in U2OS cells

siRNAs were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (PTP4A1, s15362, s15363, 104653, 114351, 114353; PTP4A2, s581, s582, s583; PTP4A3, s22005, s22006, s22007; CRY2, s3537; Silencer Select Negative Control #1 siRNA; PTP4A1/2/3, s15363, s583, s22007). Negative control transfections received 37.5 nM of Silencer Select, while CRY1 and CRY2 received 12.5 nM of a single siRNA. For single knockdowns of PTP4A2 and PTP4A3, 12.5 nM for 3 different siRNAs per gene were used (37.5 nM total). For PTP4A1, 5 different siRNAs were used at 12.5 nM (62.5 nM total). For triple knockdown of PTP4A 1/2/3, 12.5 nM of a single siRNA per target gene was used (37.5 nM total). U2OS cells stably transduced with the Per2-luciferase reporter [102] were synchronized with dexamethasone (100 nM, Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes. Following synchronization, 1 mL of lumicycle media (phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 0.5% FBS, 352.5 ug/ml sodium bicarbonate, 10 mM HEPES (Life Technologies), 2mM LGlutamine, 25 units/ml penicillin, 25 ug/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies), and 0.1 mM luciferin potassium salt (Biosynth) and 0.5 mL of transfection complexes (Opti-MEM containing 37.5 nM of each siRNA and 3.75 μL of lipofectamine RNAiMax reagent). Two days posttransfection, lumicycle medium was changed and the dishes were covered with sterile glass coverslips, sealed with sterile vacuum grease, and placed into the Lumicycle luminometer (Actimetrics). Luminescence levels were measured every 1 min for 5 d or more. Lumicycle circadian data analysis program (Actimetrics) was used to analyze recorded bioluminescence data. In brief, data was detrended by subtraction of a best fit line (first order polynomial) and, subsequently, were fit to a sine wave to obtain circadian parameter such as rhythm period length. Statistically significant differences in period length were examined via one-way ANOVA.

Gene Expression Analysis in U2OS Cells

siRNA or mock transfected U2OS cells were collected after 2 or 7 days post synchronization/transfection for RT-qPCR analysis. RNA was isolated using Trizol (ThermoFisher) and reverse transcription of 0.5 ug of RNA was performed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on CFX384 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) by using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Endogenous controls against GAPDH (human) was used for normalization. The sequences for qPCR primers were as follows: GAPDH-F, TGTTCGTCATGGGTGTGAAC; GAPDH-R, CTAAGCAGTTGGTGGTGCAG; CRY2-F, GCCGGCTTAACATTGAACGA; CRY2-R, ACAGATGCCAGTAGACAGAGTCC PTP4A1-F, CCGGCTGTATGATTAGGCCA; PTP4A1-R, ACACCACAGAATTGAGGAATATGT PTP4A2-F, GGAGTGACGACTTTGGTTCG; PTP4A2-R; TGGCCAATCTAGAACGTGGA PTP4A3-F, ACACATGCGCTTCCTCATCA; PTP4A3-R, TCAGGTCCTCAATGAAGGTGC.

QUANTIFICATION AND STASTICAL ANALYSIS

Stastical analysis was performed using Prism (Graphpad). For analysis of mRNA cycling in Drosophila tissues, Drosophila behavioral comparisons of multiple strains, luciferase rhythms, and U2OS gene expression rhythms, one-way ANOVA was used followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. For behavioral, immunostaining, and immunoblotting comparisons of two conditions, Student’s t-test was used. Significance was defined as P< 0.05. Details of statistical methods used for each experiment can be found in Method Details and Figure Legends.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti PDF | DSHB | C7 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti PERIOD | [111] | N/A |

| Rat polyclonal anti TIMELESS | [25] | N/A |

| Guinea Pig polyclonal anti PRL-1 | This paper | N/A |

| Mouse monoclonal anti TUBULIN | DSHB | E7 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti V5 | Invitrogen | 2F11F7 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti c-MYC 9E10 | Sigma | M4439 |

| Guinea Pig polyclonal anti TIMELESS | [116] | N/A |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Biological Samples | ||

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Deposited Data | ||

| Mass Spectrometry data | This paper | PRIDE: PXD020986 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| D. mel: S2R+ cells | Drosophila Genomics Resource Center | S2R+ |

| Human: U2OS cells | ATCC | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| D. mel: Df(2L) BSC278 | Flybase | BDSC #23663 |

| D. mel: Prl101; PiggyBac LL07771{3xP3DsRed} | DGRC | Kyoto #142132 |

| D. mel: PRL-1 enhancer trap; GawB{NP2526} | DGRC | Kyoto #112951 |

| D. mel: PRL-1 GD RNAi | VDRC | Vienna #45518 |

| D. mel: PRL-1 KK RNAi | VDRC | Vienna #107836 |

| D. mel: PdfGAL4 | [45] | N/A |

| D. mel: Clk4.1GAL4 | [34,35] | BDSC #36316 |

| D. mel: elavGAL4 | [97] | BDSC #458 |

| D. mel: timGAL4 | [98] | N/A |

| D. mel: pdfGAL80 | [32] | N/A |

| UAS-dcr2 on II | VDRC | Vienna #60008 |

| UAS-dcr2 on III | VDRC | Vienna #60009 |

| UAS-prl1 | [56] | N/A |

| D. mel: Prl101 PiggyBac LL07771 excisions | This paper | N/A |

| FlyFos Prl-1 strain | This paper | N/A |

| D. mel: PRL-1 GAL4 | This paper | N/A |

| TIM-STwt | This paper | N/A |

| TIM-S586A | This paper | N/A |

| TIM-T991A | This paper | N/A |

| TIM-ST/AA | This paper | N/A |

| D. mel: per01 | [99] | N/A |

| D. mel: ClkJrk | [101] | N/A |

| D. mel: iso31 W1118 | Flybase | BDSC 5905 |

| D. mel: tim01 | [100] | N/A |

| D. mel: cry01 | [83] | N/A |

| D. mel: cryb | [11] | N/A |

| D. mel: timS1 | [60] | N/A |

| D. mel: timUL | [61] | N/A |

| D. mel: perS | [99] | N/A |

| D. mel: perL | [99] | N/A |

| D. mel: UAS-mGFP | Flybase | BDSC #5137 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Table. | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| D. Pseudo: FF051244 | [55] | N/A |

| D. mel: BAC 21C10 | BacPac Resources | CH321:21C10 |

| Software and Algorithmse | ||

| Prism | GraphPad | |

| Fiji | ImageJ, NIH | |

| Clocklab | Actimetrics | |

| LumiCycle | Actimetrics | |

| Other | ||

Highlights.

Loss of PRL-1 in PDF clock neurons dramatically lengthens circadian period

PRL-1 dephosphorylates TIM promoting its nuclear accumulation

PRL-1 mutant period lengthening is suppressed in constant light

PRL-1 mutants display delayed phase under short, but not long, photoperiods

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, VDRC, DGRC, Drs. Amita Sehgal, Michael Young, and Leslie Saucedo for fly stocks and Marco Gallio and Michael Alpert for comments on the manuscript. BestGene, Inc. generated transgenic flies. Cell sorting was performed by Flow Cytometry Core Facility at Northwestern University. Proteomics services were performed by the Northwestern Proteomics Core Facility, generously supported by NCI CCSG P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center and the National Resource for Translational and Developmental Proteomics supported by P41 GM108569. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01NS106955 and DARPA grant D12AP00023. The content of the information does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the Government, and no official endorsement should be inferred.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Mohawk JA, Green CB, and Takahashi JS (2012). Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. 35, 445–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allada R, and Chung BY (2010). Circadian organization of behavior and physiology in Drosophila. Annu Rev Physiol 72, 605–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubowy C, and Sehgal A (2017). Circadian Rhythms and Sleep in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 205, 1373–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.So WV, and Rosbash M (1997). Post-transcriptional regulation contributes to Drosophila clock gene mRNA cycling. Embo J 16, 7146–7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtin KD, Huang ZJ, and Rosbash M (1995). Temporally regulated nuclear entry of the Drosophila period protein contributes to the circadian clock. Neuron 14, 365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shafer OT, Rosbash M, and Truman JW (2002). Sequential nuclear accumulation of the clock proteins period and timeless in the pacemaker neurons of Drosophila melanogaster. J Neurosci 22, 5946–5954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang DC, and Reppert SM (2003). A novel C-terminal domain of Drosophila PERIOD inhibits dCLOCK:CYCLE-mediated transcription. Curr Biol 13, 758–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darlington TK, Wager-Smith K, Ceriani MF, Staknis D, Gekakis N, Steeves TD, Weitz CJ, Takahashi JS, and Kay SA (1998). Closing the circadian loop: CLOCKinduced transcription of its own inhibitors per and tim. Science 280, 1599–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu W, Zheng H, Houl JH, Dauwalder B, and Hardin PE (2006). PER-dependent rhythms in CLK phosphorylation and E-box binding regulate circadian transcription. Genes Dev 20, 723–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emery P, So WV, Kaneko M, Hall JC, and Rosbash M (1998). CRY, a Drosophila clock and light-regulated cryptochrome, is a major contributor to circadian rhythm resetting and photosensitivity. Cell 95, 669–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanewsky R, Kaneko M, Emery P, Beretta B, Wager-Smith K, Kay SA, Rosbash M, and Hall JC (1998). The cryb mutation identifies cryptochrome as a circadian photoreceptor in Drosophila. Cell 95, 681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koh K, Zheng X, and Sehgal A (2006). JETLAG resets the Drosophila circadian clock by promoting light-induced degradation of TIMELESS. Science 312, 1809–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naidoo N, Song W, Hunter-Ensor M, and Sehgal A (1999). A role for the proteasome in the light response of the timeless clock protein. Science 285, 1737–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edery I, Zwiebel LJ, Dembinska ME, and Rosbash M (1994). Temporal phosphorylation of the Drosophila period protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91, 2260–2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sathyanarayanan S, Zheng X, Xiao R, and Sehgal A (2004). Posttranslational regulation of Drosophila PERIOD protein by protein phosphatase 2A. Cell 116, 603–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiu JC, Ko HW, and Edery I (2011). NEMO/NLK phosphorylates PERIOD to initiate a time-delay phosphorylation circuit that sets circadian clock speed. Cell 145, 357–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price JL, Blau J, Rothenfluh A, Abodeely M, Kloss B, and Young MW (1998). double-time is a novel Drosophila clock gene that regulates PERIOD protein accumulation. Cell 94, 83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kloss B, Rothenfluh A, Young MW, and Saez L (2001). Phosphorylation of period is influenced by cycling physical associations of double-time, period, and timeless in the Drosophila clock. Neuron 30, 699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin JM, Kilman VL, Keegan K, Paddock B, Emery-Le M, Rosbash M, and Allada R (2002). A role for casein kinase 2alpha in the Drosophila circadian clock. Nature 420, 816–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akten B, Jauch E, Genova GK, Kim EY, Edery I, Raabe T, and Jackson FR (2003). A role for CK2 in the Drosophila circadian oscillator. Nat Neurosci 6, 251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu W, Houl JH, and Hardin PE (2011). NEMO kinase contributes to core period determination by slowing the pace of the Drosophila circadian oscillator. Curr Biol 21, 756–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Top D, Harms E, Syed S, Adams EL, and Saez L (2016). GSK-3 and CK2 Kinases Converge on Timeless to Regulate the Master Clock. Cell Rep 16, 357–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinek S, Inonog S, Manoukian AS, and Young MW (2001). A Role for the Segment Polarity Gene shaggy/GSK-3 in the Drosophila Circadian Clock. Cell 105, 769–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang Y, Sathyanarayanan S, and Sehgal A (2007). Post-translational regulation of the Drosophila circadian clock requires protein phosphatase 1 (PP1). Genes Dev 21, 1506–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeng HK, Qian ZW, Myers MP, and Rosbash M (1996). A light-entrainment mechanism for the Drosophila circadian clock. Nature 380, 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grima B, Lamouroux A, Chelot E, Papin C, Limbourg-Bouchon B, and Rouyer F (2002). The F-box protein slimb controls the levels of clock proteins period and timeless. Nature 420, 178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo F, Cerullo I, Chen X, and Rosbash M (2014). PDF neuron firing phase-shifts key circadian activity neurons in Drosophila. eLife 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toh KL, Jones CR, He Y, Eide EJ, Hinz WA, Virshup DM, Ptacek LJ, and Fu YH (2001). An hPer2 phosphorylation site mutation in familial advanced sleep phase syndrome. Science 291, 1040–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Y, Padiath QS, Shapiro RE, Jones CR, Wu SC, Saigoh N, Saigoh K, Ptacek LJ, and Fu YH (2005). Functional consequences of a CKIdelta mutation causing familial advanced sleep phase syndrome. Nature 434, 640–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shanware NP, Hutchinson JA, Kim SH, Zhan L, Bowler MJ, and Tibbetts RS (2011). Casein kinase 1-dependent phosphorylation of familial advanced sleep phase syndrome-associated residues controls PERIOD 2 stability. J Biol Chem 286, 12766–12774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beckwith EJ, and Ceriani MF (2015). Communication between circadian clusters: The key to a plastic network. FEBS Lett 589, 3336–3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoleru D, Peng Y, Agosto J, and Rosbash M (2004). Coupled oscillators control morning and evening locomotor behaviour of Drosophila. Nature 431, 862–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grima B, Chelot E, Xia R, and Rouyer F (2004). Morning and evening peaks of activity rely on different clock neurons of the Drosophila brain. Nature 431, 869–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang L, Chung BY, Lear BC, Kilman VL, Liu Y, Mahesh G, Meissner RA, Hardin PE, and Allada R (2010). DN1(p) circadian neurons coordinate acute light and PDF inputs to produce robust daily behavior in Drosophila. Curr Biol 20, 591–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, Liu Y, Bilodeau-Wentworth D, Hardin PE, and Emery P (2010). Light and temperature control the contribution of specific DN1 neurons to Drosophila circadian behavior. Curr Biol 20, 600–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chatterjee A, Lamaze A, De J, Mena W, Chelot E, Martin B, Hardin P, Kadener S, Emery P, and Rouyer F (2018). Reconfiguration of a Multi-oscillator Network by Light in the Drosophila Circadian Clock. Curr Biol 28, 2007–2017 e2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Majercak J, Sidote D, Hardin PE, and Edery I (1999). How a circadian clock adapts to seasonal decreases in temperature and day length. Neuron 24, 219–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shafer OT, Levine JD, Truman JW, and Hall JC (2004). Flies by night: Effects of changing day length on Drosophila's circadian clock. Curr Biol 14, 424–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Menegazzi P, Vanin S, Yoshii T, Rieger D, Hermann C, Dusik V, Kyriacou CP, Helfrich-Forster C, and Costa R (2013). Drosophila clock neurons under natural conditions. J Biol Rhythms 28, 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshii T, Wulbeck C, Sehadova H, Veleri S, Bichler D, Stanewsky R, and Helfrich-Forster C (2009). The neuropeptide pigment-dispersing factor adjusts period and phase of Drosophila's clock. J Neurosci 29, 2597–2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlichting M, Menegazzi P, Lelito KR, Yao Z, Buhl E, Dalla Benetta E, Bahle A, Denike J, Hodge JJ, Helfrich-Forster C, et al. (2016). A Neural Network Underlying Circadian Entrainment and Photoperiodic Adjustment of Sleep and Activity in Drosophila. J Neurosci 36, 9084–9096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schlichting M, Weidner P, Diaz M, Menegazzi P, Dalla Benetta E, Helfrich-Forster C, and Rosbash M (2019). Light-Mediated Circuit Switching in the Drosophila Neuronal Clock Network. Curr Biol 29, 3266–3276 e3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petsakou A, Sapsis TP, and Blau J (2015). Circadian Rhythms in Rho1 Activity Regulate Neuronal Plasticity and Network Hierarchy. Cell 162, 823–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stoleru D, Nawathean P, de la Paz Fernandez M, Menet JS, Ceriani MF, and Rosbash M (2007). The Drosophila circadian network is a seasonal timer. Cell 129, 207–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Renn SC, Park JH, Rosbash M, Hall JC, and Taghert PH (1999). A pdf neuropeptide gene mutation and ablation of PDF neurons each cause severe abnormalities of behavioral circadian rhythms in Drosophila. Cell 99, 791–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stoleru D, Peng Y, Nawathean P, and Rosbash M (2005). A resetting signal between Drosophila pacemakers synchronizes morning and evening activity. Nature 438, 238–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murad A, Emery-Le M, and Emery P (2007). A subset of dorsal neurons modulates circadian behavior and light responses in Drosophila. Neuron 53, 689–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Picot M, Cusumano P, Klarsfeld A, Ueda R, and Rouyer F (2007). Light activates output from evening neurons and inhibits output from morning neurons in the Drosophila circadian clock. PLoS Biol 5, e315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cusumano P, Klarsfeld A, Chelot E, Picot M, Richier B, and Rouyer F (2009). PDF-modulated visual inputs and cryptochrome define diurnal behavior in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci 12, 1431–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kula-Eversole E, Nagoshi E, Shang Y, Rodriguez J, Allada R, and Rosbash M (2010). Surprising gene expression patterns within and between PDF-containing circadian neurons in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 13497–13502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hughes ME, Grant GR, Paquin C, Qian J, and Nitabach MN (2012). Deep sequencing the circadian and diurnal transcriptome of Drosophila brain. Genome Res 22, 1266–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeng H, Hardin PE, and Rosbash M (1994). Constitutive overexpression of the Drosophila period protein inhibits period mRNA cycling. Embo J 13, 3590–3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abruzzi KC, Rodriguez J, Menet JS, Desrochers J, Zadina A, Luo W, Tkachev S, and Rosbash M (2011). Drosophila CLOCK target gene characterization: implications for circadian tissue-specific gene expression. 25, 2374–2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davie K, Janssens J, Koldere D, De Waegeneer M, Pech U, Kreft L, Aibar S, Makhzami S, Christiaens V, Bravo Gonzalez-Blas C, et al. (2018). A Single-Cell Transcriptome Atlas of the Aging Drosophila Brain. Cell 174, 982–998 e920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ejsmont RK, Sarov M, Winkler S, Lipinski KA, and Tomancak P (2009). A toolkit for high-throughput, cross-species gene engineering in Drosophila. Nat Methods 6, 435–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pagarigan KT, Bunn BW, Goodchild J, Rahe TK, Weis JF, and Saucedo LJ (2013). Drosophila PRL-1 is a growth inhibitor that counteracts the function of the Src oncogene. 8, e61084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lamaze A, Lamouroux A, Vias C, Hung HC, Weber F, and Rouyer F (2011). The E3 ubiquitin ligase CTRIP controls CLOCK levels and PERIOD oscillations in Drosophila. 12, 549–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang Z, and Sehgal A (2001). Role of molecular oscillations in generating behavioral rhythms in Drosophila. Neuron 29, 453–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin JM, Schroeder A, and Allada R (2005). In vivo circadian function of casein kinase 2 phosphorylation sites in Drosophila PERIOD. J Neurosci 25, 11175–11183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rothenfluh A, Abodeely M, Price JL, and Young MW (2000). Isolation and analysis of six timeless alleles that cause short- or long-period circadian rhythms in Drosophila. Genetics 156, 665–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rothenfluh A, Young MW, and Saez L (2000). A TIMELESS-independent function for PERIOD proteins in the Drosophila clock. Neuron 26, 505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saez L, and Young MW (1996). Regulation of nuclear entry of the Drosophila clock proteins period and timeless. Neuron 17, 979–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee C, Parikh V, Itsukaichi T, Bae K, and Edery I (1996). Resetting the Drosophila clock by photic regulation of PER and a PER- TIM complex. Science 271, 1740–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harms E, Kivimae S, Young MW, and Saez L (2004). Posttranscriptional and posttranslational regulation of clock genes. J Biol Rhythms 19, 361–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meissner RA, Kilman VL, Lin JM, and Allada R (2008). TIMELESS is an important mediator of CK2 effects on circadian clock function in vivo. J Neurosci 28, 9732–9740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kloss B, Price JL, Saez L, Blau J, Rothenfluh A, Wesley CS, and Young MW (1998). The Drosophila clock gene double-time encodes a protein closely related to human casein kinase Iepsilon. Cell 94, 97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cyran SA, Yiannoulos G, Buchsbaum AM, Saez L, Young MW, and Blau J (2005). The double-time protein kinase regulates the subcellular localization of the Drosophila clock protein period. The Journal of Neuroscience 25, 5430–5437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kivimae S, Saez L, and Young MW (2008). Activating PER repressor through a DBT-directed phosphorylation switch. PLoS Biol 6, e183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garbe DS, Fang Y, Zheng X, Sowcik M, Anjum R, Gygi SP, and Sehgal A (2013). Cooperative interaction between phosphorylation sites on PERIOD maintains circadian period in Drosophila. PLoS Genet 9, e1003749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yildirim E, Chiu JC, and Edery I (2015). Identification of Light-Sensitive Phosphorylation Sites on PERIOD That Regulate the Pace of Circadian Rhythms in Drosophila. Mol Cell Biol 36, 855–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Myers MP, Wager-Smith K, Rothenfluh-Hilfiker A, and Young MW (1996). Light-induced degradation of TIMELESS and entrainment of the Drosophila circadian clock. Science 271, 1736–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hunter-Ensor M, Ousley A, and Sehgal A (1996). Regulation of the Drosophila protein timeless suggests a mechanism for resetting the circadian clock by light. Cell 84, 677–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Suri V, Qian Z, Hall JC, and Rosbash M (1998). Evidence that the TIM light response is relevant to light-induced phase shifts in Drosophila melanogaster. Neuron 21, 225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang Z, Emerson M, Su HS, and Sehgal A (1998). Response of the timeless protein to light correlates with behavioral entrainment and suggests a nonvisual pathway for circadian photoreception. Neuron 21, 215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sandrelli F, Tauber E, Pegoraro M, Mazzotta G, Cisotto P, Landskron J, Stanewsky R, Piccin A, Rosato E, Zordan M, et al. (2007). A molecular basis for natural selection at the timeless locus in Drosophila melanogaster. Science 316, 1898–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rothenfluh A, Abodeely M, and Young MW (2000). Short-period mutations of per affect a double-time-dependent step in the Drosophila circadian clock. Curr Biol 10, 1399–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rutila JE, Zeng H, Le M, Curtin KD, Hall JC, and Rosbash M (1996). The timSL mutant of the Drosophila rhythm gene timeless manifests allele-specific interactions with period gene mutants. Neuron 17, 921–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Winfree AT (1980). The geometry of biological time, (New York: Springer Verlag; ). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pittendrigh C, Bruce V, and Kaus P (1958). ON THE SIGNIFICANCE OF TRANSIENTS IN DAILY RHYTHMS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 44, 965–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lamba P, Bilodeau-Wentworth D, Emery P, and Zhang Y (2014). Morning and evening oscillators cooperate to reset circadian behavior in response to light input. Cell Rep 7, 601–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Roberts L, Leise TL, Noguchi T, Galschiodt AM, Houl JH, Welsh DK, and Holmes TC (2015). Light evokes rapid circadian network oscillator desynchrony followed by gradual phase retuning of synchrony. Curr Biol 25, 858–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Emery P, Stanewsky R, Hall JC, and Rosbash M (2000). A unique circadianrhythm photoreceptor. Nature 404, 456–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dolezelova E, Dolezel D, and Hall JC (2007). Rhythm defects caused by newly engineered null mutations in Drosophila's cryptochrome gene. Genetics 177, 329–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]