Abstract

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is a neglected tropical disease which contributes to the mortality and morbidity significantly in India and Brazil. This study was planned to compare the trends of incidence, prevalence, death and disability-adjusted life years (DALY) of VL burden in India and Brazil from 1990 to 2019 using Global burden of disease study (GBD) data. The metrics are presented as age-standardized rates per 100,000 inhabitants with their respective uncertainty intervals (95% UI) and relative percentages of change. The decline in the Incidence rate is more in case of India (16.82 cases per 100,000 in 1990 to 0.60 cases in 2019) as compared to Brazil (3.12 cases per 100,000 in 1990 to 2.65 cases in 2019). The annualized rate of change in number of prevalent cases for India is − 0.95 (95% UI − 0.98 to − 0.91) whereas for Brazil it is − 0.06 (95% UI − 0.41 to 0.52). The annualized rate of change in number of DALY for India is − 0.94 (95% UI − 0.96 to − 0.92) whereas for Brazil it is − 0.09 (95% UI − 0.25 to 0.28). The annualized rate of change in number of deaths for India is − 0.93 (95% UI − 0.95 to − 0.92) whereas for Brazil it is increasing i.e. 0.04 (95% UI − 0.12 to 0.51). India achieves significant reduction in the age standardized incidence, prevalence, mortality and DALY of VL as compared to Brazil during the period of 1990 to 2019. A multi-centric study is required to assess bottleneck in the existing strategies of VLSCP in Brazil.

Keywords: Visceral Leishmaniasis, Kala-azar, Incidence, Prevalence, Mortality, DALY

Introduction

Zoonoses are diseases and infections which are naturally transmitted between vertebrate animals and man & Anthroponoses are diseases transmissible from human to human. Visceral Leishmaniasis (VL) or Kala-azar is a zoonotic as well as anthroponotic disease (Hubálek 2003). VL is a neglected tropical disease which contributes to the mortality and morbidity significantly in India and Brazil (Sundar and Chakravarty 2012). In India, it is caused by parasite called Leishmania donovani and transmitted from one person to another by the bite of infected female sand fly known as Phlebotomus argentipes (Muniaraj 2014). The parasites can also be transmitted directly from person to person through the sharing of infected needles which is often the case with the HIV-VL co-infection. In the Americas, the etiological agent is the protozoan Leishmania infantum, which is transmitted through the bite of the phlebotomine Lutzomyia longipalpis, with dogs being its main urban reservoir (Lainson and Shaw 1978).

Annually 50,000 to 90,000 new cases of VL occur globally, among them only 25–45% reported to World Health Organization (WHO). According to the outbreak and mortality potential, VL remains one of the top parasitic diseases. Both India and Brazil have found their places in the list of ten countries which have reported more than 95% of new cases to WHO in 2018 (WHO factsheet 2020). According to the World Bank, India and Brazil belong to lower-middle income economies and upper-middle income economies respectively. In 2017, expenditure of India on health was 3.53% of the Gross Domestic Product, whereas Brazil’s health expenditure in the same year was 9.45% (World Bank 2020). If we look at the state-wise scenario, Kala-azar is endemic in northern and eastern States of India namely Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. 54 districts of these four states have attained endemic region status for kala-azar and few other districts have reported occasional cases as well. The latest estimated figure is 165.4 million population which is under the risk of developing kala-azar in these four states combined (MoHFW, GoI 2020). In the Americas, 12 countries have registered the presence of VL. 90% of these cases are reported in Brazil alone with the case fatality rate being around 7% (da Rocha et al 2018). Until 1990, only the Kala-azar affected and worst hit States used to carry out Kala-azar control activities in India. As the incidence of Kala-azar was soaring in parts of India, the GoI launched a centrally sponsored “Kala-azar Control Program” during 1991 (Kishore et al. 2006). In 2000, the program was further reviewed by an expert committee chaired by the director general of health services, and recommendation was made to incorporate the elimination of Kala-azar from India in the National Health Policy (Thakur et al. 2009) by renaming the same as “National Kala-azar Elimination Programme”. As we shifted our focus to review the existing policies of Brazil, we acknowledged the launch of The Brazilian Visceral Leishmaniasis Surveillance and Control Programme (VLSCP) strategies in early 1990s. This strategy included a considerable number of public health measures like canine serological analysis followed by euthanasia of seropositive dogs, together with chemical control of the vector and diagnostic techniques, early diagnosis and treatment of human cases, and population awareness (da Rocha et al 2018). From the data, it is evident that both the countries (India and Brazil) had significant burden of kala-azar in early 1990s and they have given special emphasis on the control of kala-azar in their country. To the best of our knowledge there is no comparative study available that has assessed trends in the burden of Visceral Leishmaniasis and its control in India and Brazil.

Research question: What is the effect of Visceral Leishmaniasis control programmes in India and Brazil?

Hypothesis: Is there any difference in the effect of Visceral Leishmaniasis control programmes in India and Brazil.

Objective: This study was planned to compare the trends of Visceral Leishmaniasis burden and its control in India and Brazil over past three decades using Global burden of disease study data.

Material and methods

The GBD study offers a powerful resource to understand the changing health challenges facing people across the world in the twenty-first century. Led by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), the GBD study is the most comprehensive worldwide observational epidemiological study to date. By tracking progress within and between countries GBD provides an important tool to inform clinicians, researchers, and policy makers, promote accountability, and improve lives worldwide.

Over the past two decades, the IHME has developed a methodology to quantify the burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors for informing health program and policy-making. GBD regularly provides comparable estimates of the key indicators of disease burden assessment, including the incidence prevalence, mortality and DALYs rate of Visceral Leishmaniasis. The present study utilized the GBD (2019) database to systematically summarize, analyze and compare the Incidence, Prevalence, mortality and DALYs of Visceral Leishmaniasis and its changes since 2019 for India and Brazil.

Data sources

GBD (2019) estimated each epidemiological quantity of interest—incidence, prevalence, mortality, years lived with disability (YLDs), years of life lost (YLLs), and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs)—for 23 age groups; males, females, and both sexes combined; and 204 countries and territories that were grouped into 21 regions and seven super-regions (GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators 2020). Total of 59 different data sources has been used to model the cause of death and 62 different data sources to model both cause of death and disability estimates for Visceral Leishmaniasis in India. The key sources of data to model the cause of death due to Visceral Leishmaniasis in India included Medical certification of cause of deaths of the country and of various states, India vital statistics report, WHO Global Health Observatory reported cases, other surveys on cause of death and published scientific articles (GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators 2020).

Total of 68 different data sources has been used to model the cause of death and 70 different data sources to model both cause of death and disability estimates for Visceral Leishmaniasis in Brazil. The key sources of data to model the cause of death due to Visceral Leishmaniasis in Brazil included Brazil Information system for notifiable disease for various years, Brazil mortality information system, Brazil WHO Leishmaniasis country profile, WHO Global Health Observatory reported cases, other surveys on cause of death and published scientific articles (GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators 2020).

Cause-specific death rates and cause fractions were calculated using the Cause of Death Ensemble model (CODEm) and spatiotemporal Gaussian process regression. A detailed description of CODEm is reported elsewhere (Lozano et al. 2012; Foreman et al. 2012; Murray et al. 2012, 2014). Cause-specific deaths were adjusted to match the total all-cause deaths calculated as part of the GBD population, fertility, and mortality estimates. Deaths were multiplied by standard life expectancy at each age to calculate YLLs. A Bayesian meta-regression modelling tool, DisMod-MR 2.1, was used to ensure consistency between incidence, prevalence, remission, excess mortality, and cause-specific mortality for most causes. Prevalence estimates were multiplied by disability weights for mutually exclusive sequelae of diseases and injuries to calculate YLDs. Uncertainty intervals (UIs) were generated for every metric using the 25th and 975th ordered 1000 draw values of the posterior distribution (GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators 2020).

We have included only a special category of Leishmaniasis in our paper, i.e., Visceral Leishmaniasis. Data sources for the incidence rate, prevalence, Death and DALYs of Visceral Leishmaniasis was extracted from an online tool produced by the IHME which is publicly available called the GHDx (Global Health Data Exchange) query tool (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool) (Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network 2020) Percentage change and annualized rate of change of the estimates is reported.

Results

Overall there is decrease in the Incidence rate of Visceral Leishmaniasis for both India and Brazil, however the decline is more in case of India (16.82 cases per 100,000 in 1990 to 0.60 cases in 2019) as compared to Brazil (3.12 cases per 100,000 in 1990 to 2.65 cases in 2019) (Table 1). The overall percentage decrease in Incidence rate per 100,000 from 1990 to 2019 in case of India and Brazil is 2703.33%and 17.74% respectively. The total number of incident cases due to Visceral Leishmaniasis in India declined from 174,821 cases in 1990 to 8145 cases in 2019; and for Brazil, it decreased slightly from 5275 cases in 1990 to 4983 cases in 2019. The annualized rate of change in number of incident cases for India is − 0.95 (95% UI − 0.98 to − 0.91) whereas for Brazil it is − 0.06 (95% UI − 0.41 to 0.52).

Table 1.

Mortality, incidence, DALY and prevalence rates of visceral Leishmaniasis, percentage change and annualized rates of change (95% UI) between 1990 and 2019 for India and Brazil

| Measure | Metric | # or rate (95% UI) 1990 | # or rate (95% UI) 2019 | % Change | ARC (95% UI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | Brazil | India | Brazil | India | Brazil | India | Brazil | ||

| Incidence | Number | 174,821.93 (110,890.27–252,628.84) | 5274.99 (3900.33–6929.15) | 8145.48 (4719.26–12,830.38) | 4982.85 (3391.81–7179.34) | − 2046.24 | − 5.86 | − 0.95 (− 0.98 to − 0.91) | − 0.06 (− 0.41 to 0.52) |

| Rate | 16.82 (10.69–24.40) | 3.12 (2.31–4.09) | 0.60 (0.35–0.95) | 2.65 (1.80–3.84) | − 2703.33 | − 17.74 | − 0.96 (− 0.98 to − 0.93) | − 0.15 (− 0.48 to 0.35) | |

| Prevalence | Number | 43,705.48 (27,722.57–63,157.21) | 1318.75 (975.08–1732.29) | 2036.37 (1179.82–3207.60) | 1245.71 (847.95–1794.83) | − 2046.24 | − 5.86 | − 0.95 (− 0.98 to − 0.91) | − 0.06 (− 0.41 to 0.52) |

| Rate | 4.20 (2.67–6.10) | 0.78 (0.58–1.02) | 0.15 (0.09–0.24) | 0.66 (0.45–0.96) | − 2700.00 | − 18.18 | − 0.96 (− 0.98 to − 0.93) | − 0.15 (− 0.48 to 0.35) | |

| Death | Number | 18,068.57 (2.47–90,424.02) | 992.05 (0.20–4225.78) | 1206.83 (0.15–6695.22) | 1035.35 (0.30–3983.59) | − 1397.19 | 4.18 | − 0.93 (− 0.95 to − 0.92) | 0.04 (− 0.12 to 0.51) |

| Rate | 1.97 (0.00–9.29) | 0.63 (0.00–2.53) | 0.09 (0.00–0.49) | 0.51 (0.00–2.03) | − 2088.89 | − 23.53 | − 0.95 (− 0.97 to − 0.94) | − 0.18 (− 0.27 to − 0.06) | |

| DALYs | Number | 1,274,643.39 (3006.04–6,649,597.83) | 70,140.84 (106.72–310,324.23) | 79,733.27 (133.61–469,598.71) | 64,094.67 (104.71–262,432.17) | − 1498.63 | − 9.43 | − 0.94 (− 0.96 to − 0.92) | − 0.09 (− 0.25 to 0.28) |

| Rate | 124.11 (0.29–625.70) | 41.55 (0.06–178.89) | 5.88 (0.01–34.45) | 33.63 (0.05–141.34) | − 2010.71 | − 23.55 | − 0.95 (− 0.97 to − 0.94) | − 0.19 (− 0.33 to 0.01) | |

Overall there is decrease in the Prevalence rate of Visceral Leishmaniasis for both India and Brazil, However the decline is more in case of India (4.20 cases per 100,000 in 1990 to 0.15 cases in 2019) as compared to Brazil (0.78 cases per 100,000 in 1990 to 0.66 cases in 2019). The overall percentage decrease in prevalence rate per 100,000 from 1990 to 2019 in case of India and Brazil is 2700.00% and 18.18% respectively. The total number of prevalent cases due to Visceral Leishmaniasis in India declined from 43,705 cases in 1990 to 2036 cases in 2019; and for Brazil it decreased slightly from 1319 cases in 1990 to 1246 cases in 2019. The annualized rate of change in number of prevalent cases for India is − 0.95 (95% UI − 0.98 to − 0.91) whereas for Brazil it is − 0.06 (95% UI − 0.41 to 0.52).

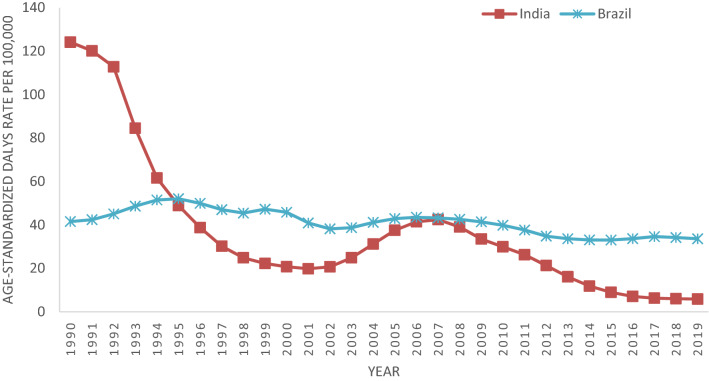

There is decrease in the DALYs rate of Visceral Leishmaniasis for both India and Brazil, However the decline is more in case of India (124.11 DALY per 100,000 in 1990 to 5.88 DALY in 2019) as compared to Brazil (41.55 DALY per 100,000 in 1990 to 33.63 DALY in 2019). The overall percentage decrease in DALY per 100,000 from 1990 to 2019 in case of India and Brazil is 2010.71% and 23.55%, respectively. The total number of DALY due to Visceral Leishmaniasis in India declined from 1,274,643 in 1990 to 79,733 in 2019; and for Brazil it decreased slightly from 70,141 in 1990 to 64,095 in 2019. The annualized rate of change in number of DALY for India is − 0.94 (95% UI − 0.96 to − 0.92) whereas for Brazil it is − 0.09 (95% UI − 0.25 to 0.28).

There is decrease in the death rate of Visceral Leishmaniasis for both India and Brazil, However the decline is more in case of India (1.97 deaths per 100,000 in 1990 to 0.09 deaths in 2019) as compared to Brazil (0.63 deaths per 100,000 in 1990 to 0.51 deaths in 2019). The overall percentage decrease in death rate per 100,000 from 1990 to 2019 in case of India and Brazil is 2088.89% and 23.53% respectively. The total number of death due to Visceral Leishmaniasis in India declined from 18,068 deaths in 1990 to 1206 deaths in 2019; whereas in Brazil it increased from 992 deaths in 1990 to 1035 deaths in 2019. The annualized rate of change in number of deaths for India is − 0.93 (95% UI − 0.95 to − 0.92) whereas for Brazil it is increasing i.e. 0.04 (95% UI − 0.12 to 0.51) (Table 1).

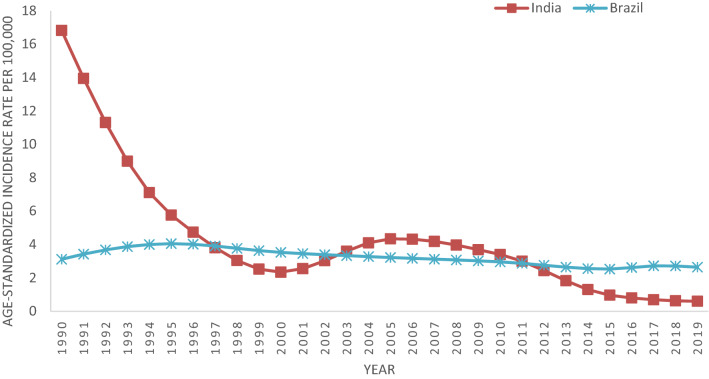

Age Standardized Incidence rates in India continuously fall from 1990 (16.81cases per 100,000) to 2000 (2.34 cases per 100,000), after that it increased till 2005 (4.34 cases per 100,000) and then gradually show declining trends till 2019 (0.60 cases per 100,000). In case of Brazil, incidence rates show a constant trend with slight variation and reached to 2.65 cases in 2019 from 3.12 in 1990 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Age standardized Incidence rates of Visceral Leishmaniasis for India and Brazil from 1990 to 2019

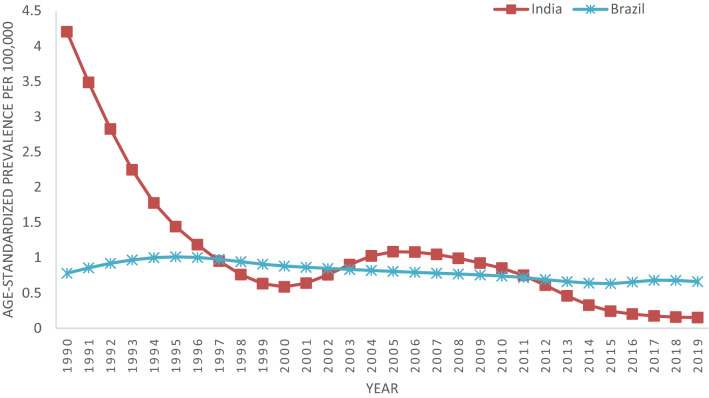

Age standardized prevalence rate in India continuously fall from 1990 (4.20 cases per 100,000) to 2000 (0.59 cases per 100,000), after that it increased till 2005 (1.08 cases per 100,000) and then gradually show declining trends till 2019 (0.15 cases per 100,000). In case of Brazil, incidence rates shows a constant trend with slight variation and reached to 0.66 cases per 100,000 in 2019 from 0.78 cases per 100,000 in 1990 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Age standardized prevalence rates of Visceral Leishmaniasis for India and Brazil from 1990 to 2019

The age-standardized mortality rate due to visceral Leishmaniasis in India was quite high in 1990 (1.97 deaths per 100,000 population) as compared to Brazil (0.63 deaths). In India it declined continuously till 2001; and comes below the mortality rate of Brazil in 1995. After 2001, it increased continuously till 2007 in India, where it reaches 0.65 deaths per 100,000 populations similar to the mortality rate of Brazil for the same year. However after 2007, the mortality rate in India continuously decline and reached to 0.089 deaths per 100,000 populations. From 1990 to 2019, Brazil has seen a slight increase or decrease in the mortality rate and it reached to 0.51 deaths in 2019 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Age standardized mortality rates of Visceral Leishmaniasis for India and Brazil from 1990 to 2019

A similar trend as seen in case of age-standardized mortality rates have been observed for age standardized DALY rate for both India and Brazil. Age Standardized DALY rates in India continuously fall from 1990 (124.1 DALY per 100,000) to 2001 (19.83 DALY per 100,000), after that it increased till 2007 (42.44 DALY per 100,000) and then gradually show declining trends till 2019 (5.88 DALY per 100,000). In case of Brazil, a slight variation in DALY rates over the years has been seen and it reached to 33.63 in 2019 from 41.55 in 1990 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Age standardized DALY rates of Visceral Leishmaniasis for India and Brazil from 1990 to 2019

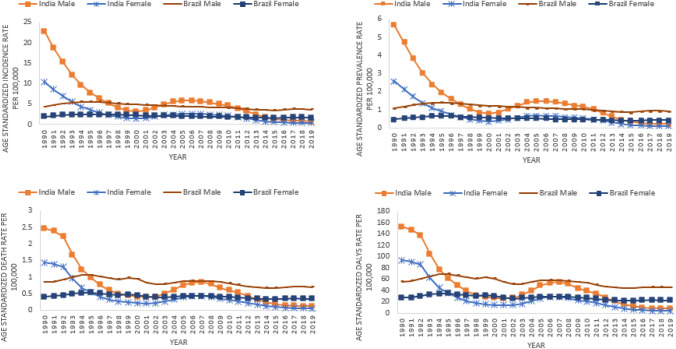

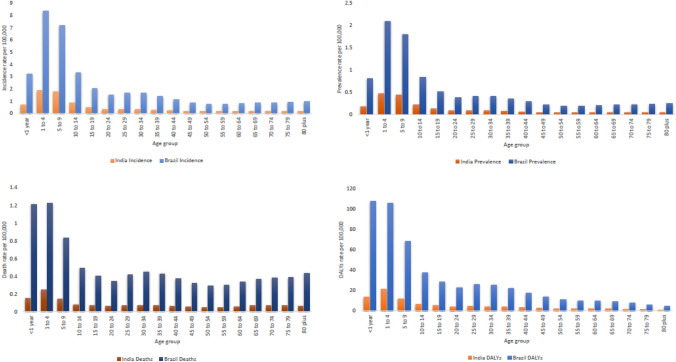

In India as well as Brazil, age standardized incidence, prevalence, mortality and DALY rates of Visceral Leishmaniasis is reported higher in males vis-à-vis females for all years i.e. 1990 to 2019. India has reduced gender based gap in the age standardized incidence, prevalence, mortality and DALY rates since past one decade and maintained approximately equal rates in males as well as females since past six years, whereas Brazil has not able to reduce gender based gap in the age standardized incidence, prevalence, mortality and DALY rates since past three decades (Fig. 5). In India as well as Brazil, higher incidence, prevalence, mortality and DALY rates of Visceral Leishmaniasis is reported in the age groups (< 1 year, 1 to 4 years, 5–9 years and 10–14 years) as compared to the age groups of 15 years and above (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Gender wise trends of Incidence, Prevalence, mortality and DALY rates of Visceral Leishmaniasis for India and Brazil; 1990 to 2019

Fig. 6.

Age wise distribution of Incidence, Prevalence, mortality and DALY rates of Visceral Leishmaniasis for India and Brazil in 2019

Discussion

We have compared the trends of kala-azar burden in India and Brazil from 1990 to 2019 using Global burden of disease study data.

Control of Visceral Leishmaniasis in India

Present study showed that Age Standardized Incidence rates in India continuously fall from 1990 (16.81cases per 100,000) to 2000 (2.34 cases per 100,000), after that it increased till 2005 (4.34 cases per 100,000) and then gradually show declining trends till 2019 (0.60 cases per 100,000). Same trend has been reported for age standardized prevalence rates. This trend may be attributed to government initiative of DDT spray in endemic areas. In 1992, the DDT spray was started second time and continued till 1995 and the effect was persistent up to year 2000 (Thakur et al. 2007). No rounds of DDT spray were carried out until 2006 (Mubayi et al. 2010), Then again, in 2007 DDT spray was started. The effect of DDT may persist from 3 years to as long as up to 7 years with the intensity and duration of spray (Thakur 2007). Another attributable factor might be development of resistance against DDT in phlebotomus argentipes in some endemic areas (Singh et al. 2001; Dhiman et al. 2003).

In India age standardized mortality rates declined continuously till 2001, after that it increased continuously till 2007. However after 2007, the mortality rate in India continuously decline and reached to 0.089 deaths per 100,000 populations. Similar trend has been reported for age standardized DALY rates. This declining trend may be attributed to government’s timely change in the diagnostic as well as treatment modalities of VL. High mortality rate in early 1990s may be attributed to decrease in the cure rate of sodium stibogluconate (SbV) to 81% in late 1980s (Thakur et al. 1991) and the pentamidine to 70–75% (Berman 1997). Because of increase in resistance to two first line antileishmanisis drugs i.e. SbV and pentamadine, amphotericin B and liposomal amphotericin B were started to be used for the treatment of VL in mid 1990s. Amphotericin B had cure rate of 99–100% (Thakur et al. 1993), this leads to continuous decline in mortality rate of VL. Increase in the mortality during the year 2001 to 2007 may be attributed to HIV-VL co-infection. Overall estimated number of HIV cases in four VL endemic states of India namely Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal were 32,767, 3643, 71,428 and 44,091 in 2000 which rose to 68,087, 11,893, 81,417 and 57,319 respectively in 2007 (GBD India Compare Data Visualization, 2017). In Bihar at the Kala-azar Medical Research Centre, Muzaffarpur; the HIV-VL co-infection rate increased from 0.88% in 2000 to 2.18% in 2006 and the number of HIV positive patients rose from 3 to 17 in the same period (WHO 2007), which is corroborated with the increase in VL mortality in the same period. The probability of death or treatment failure of VL in HIV co-infection was estimated to be 67% (Mathur et al. 2006) and 69.8% after 2 year of completion of treatment. HIV infection dramatically increases the risk of progression from asymptomatic infection to VL disease and VL accelerates HIV disease progression (Sinha et al. 2011).

The 4 A’s named as accessibility, affordability, availability and awareness remained the key characteristics where India did sound progress in case of Kala-azar control strategies and execution over the past three decades. During the study period 1990–2019, comprehensive public health measures and strategies like integrated vector management (IVM) and effective as well as efficient interventions like Indoor residual spray, personal prophylaxis, micro-environmental management, etc., were found to contribute largely to the continuous decline in the incidence, prevalence and mortality due to VL. Apart from that, the introduction of rapid diagnosis test kits for the prompt diagnosis of VL even in areas with limited transportation facilities could be considered as the major milestone in fighting the disease. Inclusion of relatively safe oral drugs like Miltefosine for the treatment of VL helped to keep the infection in control. The provision of incentives to VL patients as well as peripheral health workers like ASHA raised the awareness and thus contributed to the decline in new cases in a significant manner. New initiatives like “Kala-azar Mitra (Friend)’ were started in which past treated patients act as a communicator for providing information to the health facilities or health worker regarding new Kala-azar resembling patient (MoHFW, GoI 2015). Various Non-Governmental Organizations like CARE India, Kala-azar Medical Research Centre etc. also specifically working on prevention and control of VL in the endemic zone, which helped in substantial reduction in the burden of VL in India.

Control of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Brazil

In this study constant trend with slight variation has been reported in the age standardized incidence rates of VL which changes from 3.12 cases per 100,000 in 1990 to 2.65 cases in 2019. Similar trend were reported in age standardized prevalence rates of VL which changes from 0.78 cases per 100,000 in 1990 to 0.66 cases in 2019. In urban areas of Brazil, VL primarily transmitted from domestic dogs to people by phlebotomine sand flies (Dye 1996), to eradicate disease in these areas the basis reproduction number (R0) of L. infantum in the dog population should be decreased to < 1. The vectorial capacity of sand fly depends on various entomological parameters such as bite rate in dogs, the life expectancy, vector density and the extrinsic incubation period (Werneck 2014). Brazil has revised VL control strategy in early 1990s and launched The Brazilian Visceral Leishmaniasis Surveillance and Control Programme (VLSCP). The substantially poor impact and penetration of interventions were quite eminent due to the low sensitivity of the diagnostic tests, the long delay between diagnosis and culling, and the low acceptance of culling by dog owners. Different studies have concluded that the treatment of infected dogs cannot be an effective long-term strategy as relapses are quite frequent in such cases, and same dogs become infectious again within a short period of time (Alvar et al. 1994). A recent study conducted by Werneck et al. recommended the modification of the existing delivery of interventions according to the different transmission scenarios, along with the existing strategies of VL control program, while preferably targeting the areas at highest risk. They also emphasized on collective and efficient efforts to solve operational barriers to the adequate implementation of preventive measures (Werneck et al. 2014). A relevant quasi-experimental study conducted by da Rocha et al. on effectiveness of VLSCP pointed out several limitations in the strategies adopted by the VLSCP in the sense that the control interventions were not successful enough in interrupting L. infantum transmission, especially in urban areas (da Rocha et al. 2018).

Conclusion

Visceral Leishmaniasis is a public health problem in India as well as in Brazil. Both the countries have revised their strategies in early 1990s to control VL. India achieves significant reduction in the age standardized incidence, prevalence, mortality and DALY of VL as compared to Brazil during the period of 1990 to 2019. A multi-centric study is required to assess bottleneck in the existing strategies of VLSCP in Brazil. India’s experience can be utilized for the further reduction in the burden of VL in Brazil.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) and the University of Washington for providing the GBD estimates.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: DD, RPJ, Shalini, KB; Formal analysis: DD, RPJ, KB; Methodology: DD, RPJ, KB; Writing-original draft: DD, RPJ, Shalini, KB; Writing-review & editing: DD, RPJ, Shalini, KB.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and material

Data is publicly available on http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool and free to use.

Code availability

None.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Deepak Dhamnetiya, Email: drdeepakdhamnetiya@gmail.com.

Ravi Prakash Jha, Email: ravijha0292@gmail.com.

Shalini, Email: s4shalinii@gmail.com.

Krittika Bhattacharyya, Email: krittikabhattacharyya.federer@gmail.com.

References

- Alvar J, Molina R, San Andre´s M, Tesouro M, Nieto J, Vitutia M, , et al. Canine leishmaniasis: clinical, parasitological and entomological follow-up after chemotherapy. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;88:371–378. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1994.11812879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman JD. Human leishmaniasis: Clinical, diagnostic, and chemotherapeutic developments in the last 10 years. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:684–703. doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Rocha ICM, Dos Santos LHM, Coura-Vital W, da Cunha GMR, Magalhães FDC, da Silva TAM. Effectiveness of the Brazilian Visceral Leishmaniasis Surveillance and Control Programme in reducing the prevalence and incidence of Leishmania infantum infection. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:586. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-3166-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhiman RC, Raghavendra K, Kumar V, Kesari S, Kishore K. Susceptibility status of Phlebotomusargentipes to insecticide in districts Vaishali and Patna. J Commun Dis. 2003;35:49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye C. The logic of visceral leishmaniasis control. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55(2):125–130. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman KJ, Lozano R, Lopez AD, Murray CJ. Modeling causes of death: an integrated approach using CODEm. Popul Health Metr. 2012;10:1. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (2020) Lancet. 2019;396:1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubálek Z. Emerging human infectious diseases: Anthroponoses, Zoonoses, and Sapronoses. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(3):403–404. doi: 10.3201/eid0903.020208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian Council of Medical Research (2017) Public Health Foundation of India, and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD India Compare Data Visualization. ICMR, PHFI, and IHME, New Delhi. http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/india. Accessed 19 Feb 2021

- Kishore K, Kumar V, Kesari S, Dinesh DS, Kumar AJ, Das P, et al. Vector control in leishmaniasis. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:467–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lainson R, Shaw JJ. Epidemiology and ecology of leishmaniasis in Latin-America. Nature. 1978;273:595–600. doi: 10.1038/273595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur P, Samantaray JC, Vajpayee M, Samanta P. Visceral leishmaniasis/human immunodeficiency virus co-infection in India: The focus of two epidemics. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:919–922. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46574-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mubayi A, Castillo-Chavez C, Chowell G, Kribs-Zaleta C, Ali Siddiqui N, Kumar N, et al. Transmission dynamics and underreporting of Kala-azar in the Indian state of Bihar. J TheorBiol. 2010;262:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muniaraj M. The lost hope of elimination of Kala-azar (visceral leishmaniasis) by 2010 and cyclic occurrence of its outbreak in India, blame falls on vector control practices or co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus or therapeutic modalities? Trop Parasitol. 2014;4(1):10–19. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.129143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Ezzati M, Flaxman AD, Lim S, Lozano R, Michaud C, et al. GBD 2010: design, definitions, and metrics. Lancet. 2012;380:2063–2066. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61899-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Ortblad KF, Guinovart C, Lim SS, Wolock TM, Roberts DA, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:1005–1070. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60844-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NVBDCP) (2020) Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, GoI What is the extent of problem of kala-azar in India?. https://nvbdcp.gov.in/index4.php?lang=1&level=0&linkid=474&lid=3749. Accessed on 12 Dec 2020

- National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (2015) Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, GoI Operational Guidelines on Kala-Azar (Visceral Leishmaniasis) Elimination In India—2015. Available at https://nvbdcp.gov.in/Doc/opertional-guideline-KA-2015.pdf. Accessed on 5 Jan 2021

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network (2020) Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

- Singh R, Das RK, Sharma SK. Resistance of sandflies to DDT in Kala-azar endemic districts of Bihar in India. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:793. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha PK, van Griensven J, Pandey K, Kumar N, Verma N, Mahajan R, et al. Liposomal amphotericin B for visceral leishmaniasis in human immunodeficiency virus-coinfected patients: 2-year treatment outcomes in Bihar, India. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:e91–e98. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundar S, Chakravarty J. Recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of kala-azar. Natl Med J India. 2012;25:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur CP. A new strategy for elimination of kala-azar from rural Bihar. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126:447–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur CP, Kumar M, Pandey AK. Evaluation of efficacy of longer durations of therapy of fresh cases of kala-azar with sodium stibogluconate. Indian J Med Res. 1991;93:103–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur CP, Sinha GP, Pandey AK, Barat D, Sinha PK. Amphotericin B in resistant kala-azar in Bihar. Natl Med J India. 1993;6:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur CP, Meenakshi Thakur AK, Thakur S. Newer strategies for the kala-azar elimination programme in India. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129:102–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank (2020). Current health expenditure (% of GDP). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS?name_desc=false. Accessed on 11 Dec 2020

- The World Bank (2020) World Bank Country and Lending Groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed on 11 Dec 2020

- Werneck GL. Visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil: Rationale and concerns related to reservoir control. Rev Saude Publica. 2014;48(5):851–856. doi: 10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048005615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werneck GL, Costa CHN, de Carvalho FAA, Pires e Cruz MdS, Maguire JH, , et al. Effectiveness of insecticide spraying and culling of dogs on the incidence of Leishmaniainfantum infection in humans: a cluster randomized trial in Teresina. Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(10):e3172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020) Leishmaniasis—Fact sheet Updated on March 2020. Geneva. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis. Accessed on 11 Dec 2020

- World Health Organization. (2007) Report of the fifth consultative meeting on leishmania-HIV coinfection, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 20–22 March 2007 (No. WHO/CDS/NTD/IDM/2007.5). World Health Organization

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is publicly available on http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool and free to use.

None.