Abstract

Objective:

The symptoms and prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia contribute to the public’s negative reactions toward individuals with AD dementia and their families. But what if, using AD biomarker tests, diagnosis was made before the onset of dementia, and a disease-modifying treatment was available? This study tests the hypotheses that a “preclinical” diagnosis of AD and treatment that improves prognosis will mitigate stigmatizing reactions.

Methods:

A sample of U.S. adults were randomized to receive one vignette created by a 3x2x2 vignette-based experiment that described a person with varied clinical symptom severity (Clinical Dementia Rating stages 0 (no dementia), 1 (mild), or 2 (moderate)), AD biomarker test results (positive vs negative), and disease-modifying treatment (available vs not available). Between-group comparisons were conducted of scores on the Modified Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (FS-ADS).

Results:

The sample of 1,817 adults had a mean age two years younger than that of U.S. adults but was otherwise similar to the general adult population. The response rate was 63% and the completion rate was 96%. In comparisons of randomized groups, mild and moderate symptoms of dementia evoked stronger reactions on all FS-ADS domains compared to no dementia (all p<0.001). A positive biomarker test result evoked stronger reactions on all but one FS-ADS domain (negative aesthetic attributions) compared to a negative biomarker result (all p<0.001). Disease-modifying treatment had no measurable influence on stigma (all p>0.05).

Conclusions:

The stigmas of dementia spill over into preclinical AD, and availability of treatment does not alter that stigma. Translation of the preclinical AD construct from research into practice will require interventions that mitigate AD stigma to preserve the dignity and identity of individuals living with AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s biomarkers, Preclinical Alzheimer’s, stigma, treatment

1.0. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is among the most feared diseases of aging. As a result, patients experience notable stigma. This stigma sometimes leads people to patronize, stereotype, isolate, or discriminate against individuals with AD (Batsch and Mittelman, 2012; Corner and Bond, 2004; Werner and Giveon, 2008). Stigma can also discourage individuals with cognitive symptoms from seeking diagnosis, hinder patients’ quality of life, and discourage participation in AD research (Alzheimer’s Association National Plan Milestone Workgroup et al., 2014; Anderson and Egge, 2014; Connell et al., 2007). These reactions are in part a consequence of the public’s expectations of the course of disease, in other words, the prognosis: AD patients experience progressive and untreatable cognitive impairments that cause disability. A similarly designed vignette-based experiment as this study found that this prognosis, not the diagnostic label, intensifies stigmatizing reactions (Johnson et al., 2015).

One way to reduce AD stigma could be to discover disease-modifying treatments that improve the prognosis. AD is currently undergoing this transformation. Advances in AD biomarkers – biological markers of disease such as amyloid and tau – are allowing earlier identification of the disease in persons with mild or even no cognitive impairment (Jack et al., 2018). AD may be diagnosed in a preclinical stage that is defined by the presence of AD biomarkers and the absence of impairment. Biomarker advances are also helping researchers to discover novel targets to develop and test therapies. The goal of these advances is to validate a biomarker-based diagnosis of AD that is treated with disease-modifying treatments that slow or prevent the onset of cognitive and functional impairments.

Recently (albeit controversially), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved aducanumab (Aduhelm; Biogen), a drug that targets amyloid. The intervention strategy relies on a biomarker test to diagnose AD early in the disease and then to prescribe a disease-modifying treatment (Lopez et al., 2019; “November 6, 2020,” 2020; Sperling et al., 2014).

Diagnosis and treatment before the onset of Mild Cognitive Impairment (also known as Mild Neurocognitive Disorder) or dementia caused by AD—that is, in a preclinical stage—might mitigate the stigma associated with progressive disability. Yet, at the same time, the success of this approach depends on mitigating stigma: individuals must be willing to seek out diagnosis early in the disease process, but, as observed in persons with clinical AD, stigma is a barrier to seeking care (Alzheimer’s Association National Plan Milestone Workgroup et al., 2014). Will the stigma associated with MCI and dementia caused by AD spill over to persons in the preclinical stage? If so, it will also be necessary to reduce stigma to ensure that it is not a barrier to care and that these individuals maintain quality of life.

This study examines how a preclinical diagnosis of AD and disease-modifying treatments affect stigma. We conducted an online experiment with a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults to examine: 1) whether a disease-modifying treatment for AD would change the stigma the general public ascribes to persons with AD (hereafter, “public stigma”); and 2) whether dementia symptoms and a positive biomarker test result cause more stigma than no symptoms or a negative biomarker result. The results of this study can help to translate the emerging construct of preclinical AD from research into clinical practice.

1.1. General framework for stigma

The conceptual framework for the design of this study is informed by Link and Phelan’s (2001) theory of stigma, modified labeling theory (Link et al., 1989), and the social-cognitive model of stigma (Corrigan, 2007, 2006). The conceptual framework contains four assumptions: 1) a signal, such as a diagnostic label, marks someone as a potential target of negative reactions; 2) the signal prompts others to apply negative stereotypes—that is, cognitive frameworks that give meaning to signals; 3) these stereotypes evoke emotions such as pity or fear; 4) these emotions drive damaging behaviors, like discrimination, ostracism, and paternalism.

Recently published scholarship on public stigma of AD underscores its insidious nature as a cross-cultural phenomenon (Hagan and Campbell, 2021; Lee et al., 2021; Nguyen and Li, 2020; Rewerska-Juśko and Rejdak, 2020; Werner and Kim, 2021). This work raises the concern that a biomarker-based definition of AD could shift the character of the stigma associated with AD, which could negatively affect individuals diagnosed early and their families (Ronchetto and Ronchetto, 2021; Rosin et al., 2020). This has been observed in cancer, where a preclinical diagnosis can be associated with stigma (Scherr et al., 2017) and receiving treatment for that diagnosis can also be stigmatizing (Kenen et al., 2007).

Understanding of a condition as chronic versus terminal may also affect stigma. Advances in cancer research and care, for example, have transformed how the public understands some kinds of cancer. They are chronic rather than terminal conditions (Nakash et al., 2020).

Moreover, because stigma is influenced heavily by stereotypes, the public’s expectations about how the disease affects individuals is an essential element of stigma. Mental illness, for instance, is similar to AD insofar as both are expected to have cognitive, emotional, and mental impacts on individuals. Yet, stigma of these conditions differs in terms of the specific qualities ascribed to these diagnoses; whereas mental illness evokes worries of danger and violence, these qualities are notably absent in AD stigma(Stites et al., 2018).

The present study builds upon our prior work that focused on understanding how a disease’s perceived prognosis or course contributes to stigma (Johnson et al., 2015). Jones (1984) highlights course as one of six underlying dimensions of stigma and defines it as the “pattern of change over time” persons associate with a condition (p. 24). Subsequent research has primarily studied course not as a dimension of stigma but as a dependent variable, asking: how does manipulating the perceived cause or controllability of a stigmatized condition affect persons’ perceptions of the condition’s course? In this study, we adopt Jones’ framework and examine how changing the course of AD affects stigma. This builds on prior studies that showed prognosis of AD intensifies stigmatizing reactions. This study examines whether this is also true in individuals who have biomarkers of AD but do not have cognitive impairment.

We examined how AD biomarker test results, treatment for AD, and symptoms of cognitive impairment would operate as signals triggering negative reactions. First, we hypothesized that a positive biomarker test result would intensify public stigma as compared to a negative biomarker test result. This hypothesis was informed by Link and Phelan’s (2001) theory of stigma (Link and Phelan, 2001). As a condition, AD exhibits the five interrelated components that Link and Phelan (2001) argue are important for claiming that a characteristic is stigmatized. Alzheimer’s is a 1) human difference that 2) people associate with negative attributes such as poor hygiene and disruptiveness in social situations (Stites et al., 2018; Werner et al., 2011, 2010). These associations lead persons to 3) separate persons with and without Alzheimer’s into “us” versus “them” categories. For instance, research into “anticipatory dementia” describes significant distress among some older adults that normal memory problems associated with aging are an indication of dementia (Cutler and Hodgson, 1996; French et al., 2012). This indicates that people make distinctions between “us”—older adults who sometimes face memory lapses—and “them”—those with a feared Alzheimer’s diagnosis. We expected that an AD biomarker test result would operate as a factor contributing to this distinction between “us” (negative test result) versus “them” (positive test result).

We hypothesized that availability of a treatment that slowed AD would mitigate public stigma as compared to when no disease-modifying treatment was available. Few studies have examined how stigma associated with an untreatable, terminal disease is affected by the advent treatment. Treatment might alleviate stigma, or alternatively, negative attitudes about the disease, its causes, and the persons it affects might keep stigma societally entrenched. In HIV, studies have shown availability of treatments have changed but not ultimately eliminated stigma of that disease. One study showed that after 12 months on treatment, individuals’ experiences of internalized stigma decreased by half, and they disclosed their HIV status to a significantly greater number of family members (i.e., from a median of two family members to a median of three at follow-up) (Pulerwitz et al., 2010). Another study focused on public stigma of HIV found that distribution of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa was associated with some features of stigma decreasing while others increased. For example, researchers found social distancing of persons living with HIV decreased after a treatment was available, but anticipated stigma due to increased social contact was heightened (Chan and Tsai, 2016).

Given that the first goal of the U.S. National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease is to diagnosis persons with AD before the onset of symptoms and then prevent or delay the onset of dementia (Alzheimer’s Association National Plan Milestone Workgroup et al., 2014), we tested how dementia symptoms impact stigma. We expected that both mild and moderate clinical symptoms would produce relatively more stigma than no symptoms. This hypothesis seems intuitive, but this is the first study to our knowledge to quantify and characterize differences in stigma between no symptoms and gradations of dementia symptoms. As an extension of how stereotypes are understood to operate in the stigma experience generally (Corrigan, 2007, 2006) and of data on symptom attribution in AD specifically (Johnson et al., 2015; Stites et al., 2018, 2016), stigma can be understood as the over-attribution and misattribution of characteristics about the disease in ways that inaccurately and prejudicially impact on individuals with AD. For example, due to stigma, a person with mild memory problems might be assumed to have severe memory problems. Thus, while we expected any symptoms would result in greater stigma than no symptoms, we needed to discover whether AD stigma would differ between persons with mild versus moderate symptoms. The results of this analysis have potentially significant implications for preclinical AD, where persons with no symptoms might progress to show mild stage symptoms.

2.0. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is a vignette-based experiment. The study flow from invitation through analysis is shown in Figure 1. Data collection occurred between June 11 and July 3, 2019.

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram: Study flow through analysis

Note. The comprehension item confirmed respondents accurately understood the educational information on use of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Respondents were given two opportunities to select the correct choice. Those who failed on the second attempt were excluded.

*Demographic quota – Population-based allocations were used for race, ethnicity, gender, education achievement.

2.2. Setting and Participant Eligibility

Adults able to read English were invited at random from a large research panel maintained by Qualtrics that mirrored census representation in the United States. The response rate was 63%. The completion rate was 96%.

Randomly invited panel members who consented to complete the survey were first asked to provide demographic data. These data were used to establish a sampling frame defined by population-based quotas for race, ethnicity, gender, and educational achievement. If the demographic profile was full, the individual was not eligible to proceed. If the demographic profile was associated with a not-yet filled sampling frame, the participant was able to proceed.

Next, participants were asked to complete a comprehension item. Participants read a paragraph about AD biomarker testing and then answered a fact-based question (e-Appendix A). They were given two opportunities to answer correctly. Participants who failed the second attempt were excluded (n=272).

2.3. Vignettes

Simple randomization was used to assign participants to one of 72 vignettes created by a 3x2x2 factorial design. All participants were shown a vignette that described a fictional person who presented for a new patient visit at a memory center with an adult daughter. Vignettes varied across three factors: clinical symptom severity, AD biomarker test result, and whether a disease-modifying treatment for AD was available.

The patient’s symptoms were described as consistent with the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Scale, a validated informant and patient interview assessing the participant’s cognition and functioning, scores of 0 (none), 1 (mild) or 2 (moderate) (Hughes et al., 1982). The CDR uses six domains: memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care.

The vignette described that the patient undergoing a “brain scan test” for an AD biomarker to determine whether memory problems were caused by AD. The scan result was reported in the vignette as either ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ for an AD biomarker. This result conforms to FDA labels for PET biomarker tests that measure brain amyloid.

The doctor explained that a disease-modifying treatment for AD was or was not available. The treatment was described one that “could slow the progression of the disease.”

The stimuli were balanced by age (60, 70, or 80 years old) and gender (man or woman) to counterbalance effects that could be attributed to these characteristics. We opted a priori to not manipulate the fictional patient’s race but rather to use data from this study to inform a future study that will experimentally manipulate multiple signals related to race-based discrimination. Vignette samples for the conditions describing mild stage dementia and positive biomarker without treatment available, a cognitively unimpaired state with negative biomarker and treatment available, and others are presented in the e-appendix.

2.4. Measurements

AD public stigma was assessed using a modified Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (FS-ADS) (Werner et al., 2011). Some items on the original instrument were adapted for understandability and relevance (Johnson et al., 2015). The modified FS-ADS is the only validated scale that specifically measures AD stigma. It does so across a range of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral attributions consistent with Link and Phelan’s (2001) theory of stigma, modified labeling theory (Link et al., 1989), and the social-cognitive model of stigma (Corrigan, 2007, 2006).

The modified FS-ADS has seven domains: Structural Discrimination, or the extent to which the participant believed that the person described in the vignette should worry about encountering discrimination by insurance companies or employers and was excluded from voting or medical decision making; Negative Severity Attributions, or the extent to which the participant believed that the person described in the vignette would be expected to have certain symptoms like speaking repetitively or suffering incontinence; Negative Aesthetic Attributions, or the extent to which the participant believed that the person described in the vignette should be expected to have poor hygiene, neglected self-care, and appear in other ways that provoke negative judgments; Antipathy, or the extent to which the participant believed that the person described in the vignette evoked feelings of disgust or repulsion; Support, or the extent to which the participant expected that others would feel concern, compassion, or willingness to help the person described in the vignette; Pity, or the extent to which the participant expected that others would feel sympathy, sadness, or pity toward the person described in the vignette; and Social Distance, or the extent to which the participant expected that person described in the vignette would be ignored or have social relationships limited by others. The overall internal consistency of the adapted form appeared similar to that of the original scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91) (Werner et al., 2011), with Cronbach alphas for all individual domains being above 0.80, suggesting “better than good” internal reliability, except for the Pity scale, which had a score of 0.77, suggesting “good” internal reliability. Responses were recorded on a 5-point scale arranged on the screen horizontally from left to right, and analyzed by domain using an established method (Johnson et al., 2015). Higher scores indicated stronger endorsement. Basic demographic data were collected using U.S. Census categories. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania approved all procedures involving human subjects.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

A formal calculation using data on the smallest between-group mean difference on the FS-ADS (Stites et al., 2016) and a Type I error rate (alpha) of 0.05 (2-sided) showed a sample of 1,800 participants would be sufficient to maintain at least 95% statistical power in estimations of main study effects. Means and proportions were used to characterize the sample. Normal 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and Fisher’s exact test of proportions were used to compare the sample to general population (“American Community Survey (ACS),” n.d.). ANOVA, Kruskal Wallis, and ordered logistic regression (OLR) were used to test for between-group differences on FS-ADS domains and produced similar results. Cohen’s d and common odds ratios (ORs) from OLR were used to report effects sizes. The ORs provide an estimate of the average probability of higher scores in a group compared to the referent and offer a robust effect size estimate in skewed data (Liu et al., 2017).

Analyses were balanced for participant age, gender, and race and also for the person described in the vignette for age and gender. Statistical tests were two-sided. P-values corrected for multiple comparisons in the ANOVA using Tukey HSD. Those ≤0.002 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed in Stata 16 (College Station, TX).

3.0. Results

3.1. Respondent Characteristics

In the sample of 1,817, the mean age was 46 years (95%CI, 46 to 47), which is two years younger than the mean of the U.S. adult population (Table 1). About half of participants were female (52.3% [95%CI, 50.0 to 54.6]), most self-identified as White (77.9% [95%CI, 75.9 to 79.7]), and most had beyond a high school education (59.3% [95%CI, 57.0 to 61.5]). These percentages similar to the U.S. adult population (all p≥0.05). All demographics were balanced across study conditions.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Sample of General Adult Public (N=1,817)

| Respondent Characteristic | Sample (N=1,817) | U. S. General Adult Population |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (95%CI) | 46.4* (45.6 to 47.1) | 48.4 |

| Females, % (95%CI) | 52.3 (50.0 to 54.6) | 51.6 |

| Race / Ethnicity, % (95%CI) | ||

| White | 77.9 (75.9 to 79.7) | 78.0 |

| African American | 11.6 (10.2 to 13.1) | 12.6 |

| Other | 10.6 (9.2 to 12.1) | 9.4 |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 17.8 (16.1 to 19.7) | 16.2 |

| Education, % (95%CI) | ||

| High School/GED or Less | 40.7 (38.5 to 43.0) | 39.5 |

| Some College or 2-year Degree | 28.3 (26.2 to 30.4) | 28.2 |

| 4-year College Degree | 21.0 (19.2 to 23.0) | 20.6 |

| Professional Degree | 10.0 (8.7 to 11.4) | 11.6 |

Note. Column percentages may not total 100 due to rounding. General population data from U.S. Census Bureau.

Reported past or current primary caregiver of a person with Alzheimer’s disease. The definition of “caregiver” provided was having “a formal or informal role providing care to a relative or friend 18 years or older to help them take care of themselves. Caregiving may include help with the physical and emotional wellbeing of a person who was diagnosed with or believed to have Alzheimer’s disease.”

Respondents were asked how much time they personally spent with a person with AD dementia; response options ranged in frequency and intensity from “rarely or never” to “every day for many hours.”

Respondents were also asked to rate the degree the condition described in the vignette had a biologic origin, psychologic origin, was a part of typical aging, and was a mental illness from “not at all” (1) to “a very great extent” (5).

Alzheimer’s disease knowledge scale. Maximum possible score = 30.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

3.2. Clinical Symptom Severity: Mild and Moderate Stages of Dementia versus Cognitively Unimpaired

More participants in the condition describing mild stage dementia worried about structural discrimination (OR, 2.3 [95%CI, 1.9 to 2.8]) and endorsed greater expectations of social distance (OR, 3.0 [95%CI, 2.4 to 3.7]) as compared to the cognitively unimpaired condition (Table 2). More participants in the condition with mild stage dementia endorsed harsher judgements of symptoms (OR, 9.7 [95%CI, 7.7 to 12.2]), harsher aesthetic judgements (OR, 2.7 [95%CI, 2.0 to 3.5]), more antipathy (OR, 2.6 [95%CI, 2.0 to 3.0]), more support (OR, 1.7 [95%CI, 1.4 to 2.1]), and more pity (OR, 3.9 [95%CI, 3.2 to 4.8]) compared with the cognitively unimpaired condition.

Table 2.

Between-group comparisons of modified Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (FS-ADS) based on Alzheimer’s disease (AD) biomarker test result, treatment availability, and clinical symptom severity in sample of general adult public (N=1,817)

| FS-ADS Domain | Estimate Name | Positive Biomarker Testa (n=912) | No Treatment Availableb (n=906) | Mild Clinical Symptomsc (n=606) | Moderate Clinical Symptomsc (n=607) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Discrimination | OR (95%CI) | 2.63*** (2.23 to 3.11) | 1.11 (0.95 to 1.30) | 2.28*** (1.87 to 2.79) | 2.31*** (1.89 to 2.83) |

| Significance (p-value, Cohen’d) | <0.001, 0.55 | P=0.11, 0.07 | <0.001, 0.43 | <0.001, 0.44 | |

| Negative Severity Attributions | OR (95%CI) | 1.53*** (1.30 to 1.79) | 0.96 (0.82 to 1.13) | 8.66*** (6.91 to 10.86) | 9.70*** (7.72 to 12.19) |

| Significance (p-value, Cohen’d) | <0.001, 0.23 | P=0.40, 0.04 | <0.001, 0.74 | <0.001, 0.80 | |

| Negative Aesthetic Attributions | OR (95%CI) | 1.08 (0.90 to 1.30) | 0.96 (0.80 to 1.16) | 6.90*** (5.28 to 9.01) | 2.66*** (2.01 to 3.50) |

| Significance (p-value, Cohen’d) | p=0.53, 0.03 | P=0.59, 0.03 | <0.001, 0.52 | <0.015, 0.17 | |

| Antipathy | OR (95%CI) | 1.56*** (1.32 to 1.83) | 1.04 (0.89 to 1.23) | 2.59*** (2.11 to 3.17) | 2.45*** (2.00 to 3.01) |

| Significance (p-value, Cohen’d) | <0.001, 0.16 | P=0.59, 0.02 | <0.001, 0.35 | <0.001, 0.32 | |

| Support | OR (95%CI) | 1.31*** (1.11 to 1.54) | 1.00 (0.86 to 1.18) | 1.71*** (1.40 to 2.08) | 1.72*** (1.42 to 2.10) |

| Significance (p-value, Cohen’d) | p<0.001, 0.16 | P=0.97, 0.0 | <0.001, 0.31 | <0.001, 0.34 | |

| Pity | OR (95%CI) | 2.07*** (1.76 to 2.43) | 1.02 (0.87 to 1.20) | 3.73*** (3.04 to 4.59) | 3.90*** (3.18 to 4.80) |

| Significance (p-value, Cohen’d) | <0.001, 0.40 | P=0.72, 0.01 | <0.001, 0.68 | <0.001, 0.70 | |

| Social Distance | OR (95%CI) | 1.55*** (1.32 to 1.83) | 1.05 (0.89 to 1.24) | 3.07*** (2.49 to 3.79) | 2.96*** (2.41 to 3.65) |

| Significance (p-value, Cohen’d) | <0.001, 0.22 | p=0.48, 0.03 | <0.001, 0.49 | <0.001, 0.46 |

Note. OR = odds ratio from ordered logistic regression. 95%CI = 95% confidence interval of OR. Exact P-values corrected for multiple comparisons in the ANOVA using Tukey HSD.

Reference group = Negative biomarker test result.

Reference group = Disease-modifying treatment available.

Reference group = No clinical symptoms.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Comparisons of the condition with moderate stage dementia to the cognitively unimpaired condition showed similar results. All analyses were balanced for treatment availability and biomarker test result.

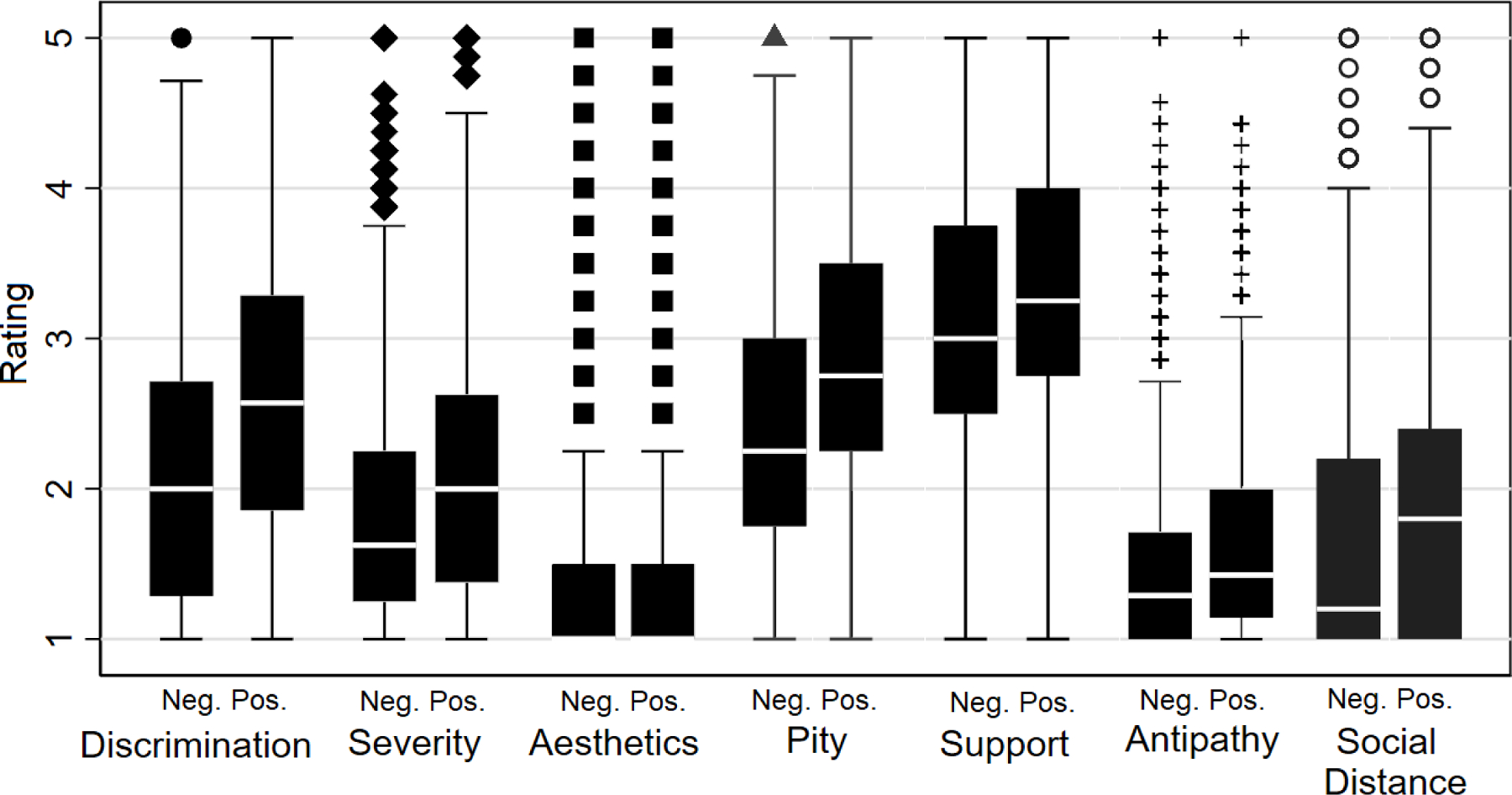

3.3. Biomarker Test Result: Positive versus Negative

Median scores on six of seven FS-ADS domains were higher in the positive biomarker condition than in the negative biomarker condition (Figure 2). More participants worried about structural discrimination in the positive biomarker condition as compared to the negative biomarker condition (OR, 2.6 [95%CI 2.2 to 3.1]). Equivalently, about 905 of 912 (99.2% [95%CI, 98.4 to 99.7]) individuals endorsed higher scores on the structural discrimination index in the positive biomarker condition compared to 348 of 905 (38.5% [95%CI, 35.3 to 41.7]) in the negative biomarker condition.

Figure 2.

Box plot of domain distributions on Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (FS-ADS) by biomarker test result.

Neg. = A negative Alzheimer’s disease biomarker test. Pos. = A positive Alzheimer’s disease biomarker test.

Legend: point = outlier, defined as a value more than 1.5 times the lower or upper quartile; upper and lower whiskers = maximum and minimum values, respectively, excluding outliers; top and bottom of rectangle = upper and lower quartiles, respectively; and white horizontal line = median value.

More participants rated the person in the vignette’s dementia symptoms as more severe in the biomarker positive condition than in the negative biomarker condition (OR, 1.5 [95%CI, 1.3 to 1.8]). In addition, more people expected the person in the vignette would be distanced in his or her social relationships in the biomarker positive condition than in the negative biomarker condition (OR, 1.6 [95%CI, 1.3 to 1.8]).

Participants expressed stronger emotional reactions in the positive biomarker condition as compared to the negative biomarker condition. They endorsed greater antipathy (OR, 1.6 [95%CI, 1.3 to 1.8]), pity (OR, 2.1 [95%CI, 1.8 to 2.4]), and support (OR, 1.3 [95%CI, 1.1 to 1.5]) in the positive biomarker as compared to the negative biomarker condition.

All analyses were balanced for clinical symptom severity and treatment availability.

3.4. Availability of Disease-Modifying Treatment

The general public’s reactions on each of FS-ADS domains were similar in the condition in which a disease-modifying treatment was available as when a disease-modifying treatment was not available. Analyses were balanced for clinical symptom severity and biomarker test result (all p>0.05).

3.5. Availability of Disease-Modifying Treatment in Positive Biomarker Test Result Condition

We hypothesized that a disease-modifying treatment would cause, on average, lower FS-ADS scores. We found treatment caused no statistically measurable differences in FS-ADS scores (all p>0.05). To examine the anticipated future of diagnosis and treatment in AD wherein a positive biomarker test result leads to prescription of a disease-modifying treatment, we performed a sub-analysis that compared the treatment availability conditions in only biomarker-positive vignettes.

In the condition where the person in the vignette had a positive AD biomarker result, 30% more respondents worried about structural discrimination if there was no disease-modifying treatment available than if a disease-modifying treatment was available (OR, 1.3 [95%CI 1.04 to 1.7], Table 3). However, endorsement of discrimination did not reach the criterion for statistical significance that was adjusted for multiple comparisons (P=0.007). No other differences were observed. Analyses were balanced for clinical symptom severity.

Table 3.

Between-group comparisons of adult public’s reactions on modified Family Stigma in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (FS-ADS) in conditions when Alzheimer’s disease (AD) treatment is available versus not available for the person in vignette with positive biomarker test result (N=906)

| FS-ADS Domain | Estimate Name | No Treatment Available (n=906) |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Discrimination | OR (95%CI) | 1.31* (1.05 to 1.64) |

| Significance (p-value, Cohen’d) | p=0.018, 0.16 | |

| Negative Severity Attributions | OR (95%CI) | 0.95 (0.76 to 1.19) |

| Significance (p-value, Cohen’d) | p=0.67, 0.05 | |

| Negative Aesthetic Attributions | OR (95%CI) | 0.98 (0.75 to 1.27) |

| Significance (p-value, Cohen’d) | p=0.86, 0.0 | |

| Antipathy | OR (95%CI) | 0.99 (0.79 to 1.25) |

| Significance (p-value, Cohen’d) | p=0.96, 0.01 | |

| Support | OR (95%CI) | 0.92 (0.74 to 1.16) |

| Significance (p-value, Cohen’d) | p=0.49, 0.03 | |

| Pity | OR (95%CI) | 0.92 (0.73 to 1.15) |

| Significance (p-value, Cohen’d) | p=0.46, 0.04 | |

| Social Distance | OR (95%CI) | 1.01 (0.80 to 1.27) |

| Significance (p-value, Cohen’d) | p=0.95, 0.0 |

Note. Reference group = AD treatment not available. OR = odds ratio from ordered logistic regression. 95%CI = 95% confidence interval.

Analyses balanced for clinical symptom severity.

Exact P-values corrected for multiple comparisons in the ANOVA using Tukey HSD.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

4.0. Discussion

We report the results from an online factorial design experiment in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults to discover how a pre-clinical diagnosis of AD and disease-modifying treatments would change public stigma. Our work builds upon the understanding that the poor prognosis of dementia drives stigma and that stigma associated with dementia is an impediment to seeking care and wellbeing (Alzheimer’s Association National Plan Milestone Workgroup et al., 2014). The results of this study suggest the stigma experienced in clinical AD extends to the preclinical stages – described as cognitively unimpaired and AD biomarker-positive. Stigma therefore will likely impede care in the preclinical stage, just as it does during later stages of AD, when clinical symptoms are present.

4.1. Hypotheses

We hypothesized that the availability of a disease-modifying treatment would cause, on average, lower FS-ADS scores. We found treatment availability caused no statistically measurable differences in FS-ADS scores in either the main comparisons or in a sub-analysis that compared the treatment availability conditions in only biomarker-positive vignettes. The consistency of the results across the two approaches to analysis as well as the rigor of our experimental design suggest that availability of a disease-modifying treatment will have little effect on public stigma of AD.

This result is disappointing. Because the expectation of worsening prognosis drives AD stigma (Johnson et al., 2015), it was reasonable to expect a treatment that would modify the trajectory of disease course might also modify the stigma it precipitates. Our data do not, however, support this. A hypothesis based on this result might be that treatability is one (perhaps minor) component of AD that could lead to stigma, and its mitigating effects may be outweighed by other components of AD that contribute to stigma. In stigma of HIV, for example, the effect of improved prognosis is likely outweighed by enduring stereotypes of sexual looseness, homosexuality, and IV drug use, among others. Another hypothesis might include the possibility that how a treatment is described may impact its efficacy for mitigating stigma—consider “prevention of disease progression” vs “cure” or simply “prevention”. Nonetheless, our findings suggest the availability of disease-modifying therapies will not abate public stigma. This interpretation is consistent with the advent of combination of antiretroviral therapies that maximally suppress the HIV virus and stop the progression of HIV disease, where HIV stigma remains a serious problem and correlate of treatment non-adherence (Earnshaw et al., 2013).

We also hypothesized that a positive biomarker test result would lead to higher FS-ADS scores than would a negative biomarker test result. We found support for this hypothesis. The positive biomarker condition evoked stronger reactions on all but one FS-ADS domain (negative aesthetic attributions) as compared to the negative biomarker condition (all p<0.001). There was no observed difference in negative aesthetic attributions. This makes intuitive sense, as a biomarker test result alone should not affect a person’s appearance.

The affirmative findings for structural discrimination, symptom severity, social distance, antipathy, pity, and support are worrisome. They suggest that individuals for whom a positive versus negative biomarker result is known may be negatively impacted in a variety of ways. The fact these results arise from comparisons of positive versus negative results is also notable. Some prior research in HIV showed that individuals who had not been tested and those tested but who did not know their results held significantly more negative attitudes about testing than individuals who were tested, particularly people who knew their test results (Kalichman, 2003). While these findings were only evaluated in individuals who tested negative for HIV, their findings suggest that availability of a test result may impact stigma. Thus, knowing how availability of AD biomarker testing impacts on AD public stigma may be informative to research outreach efforts.

We also found support for our hypothesis that stigma would intensify with the presence but not the severity of clinical symptoms of dementia. In comparisons of randomized groups, mild and moderate stages of dementia evoked similarly stronger reactions on all FS-ADS domains compared to the cognitively unimpaired condition (all p<0.001). In AD, once a person has clinical symptoms, whether mild or moderate stage dementia, the stigma experience is similar and much greater than if they had no dementia. This is consistent with prior studies showing that AD stereotypes – fixed and oversimplified ideas that can obscure details – involve symptoms (Johnson et al., 2015; Stites et al., 2018, 2016). Thus, the presence of symptoms – independent of their severity – evoke stereotypic judgments or reactions to an individual. We discuss practical implications of this finding below.

4.2. Interpretation in Context of Existing Literature

Our findings are similar to the results from studies on how knowledge of AD biomarker status affects cognitively unimpaired older adults. Cognitively unimpaired individuals who learned they had an “elevated” amyloid PET scan result through their participation in AD research reported more worries about their future and their cognitive abilities than people who learn a “not elevated” result; they also reported concerns about how others, such as family, friends and co-workers, would treat them in light of the “elevated” result (Largent et al., 2021, 2020).

Additionally, our findings build on the results of a study of public stigma in AD that showed expectations of a worsening prognosis were a key driver of stigmatizing reactions (Johnson et al., 2015). The present study suggests that these reactions would not be mitigated by therapies that would improve the prognosis. This raises a key question about what interventions, then, would mitigate stigma towards persons with AD. We explore answers to this question in the next section.

4.3. Practical Implications

Our findings suggest the stigma of clinical AD will spill over to individuals who learn positive AD biomarker results; moreover, disease-modifying therapies are unlikely to mitigate these effects. Reducing public stigma of AD is important for facilitating the success of Alzheimer’s prevention research, which often requires learning an AD biomarker result (Alzheimer’s Association National Plan Milestone Workgroup et al., 2014), and when that research is successful in identifying a disease-modifying therapy, promoting uptake of care. Successfully reducing stigma may require multi-level interventions that happen through patient-provider interactions in clinical and research settings as well as policy and public campaigns.

Our study offers insight into the types of reactions and interactions that individuals living with preclinical AD will encounter and suggests that stigma of AD is not likely to resolve with discovery of disease-modifying therapies. Other interventions will be needed. Patient-provider interactions in clinical and research settings are one of the earliest opportunities to address AD stigma, as this is when biomarker test results are often being returned to individuals. Brief interventions can help address common consequences of AD stigma, such as isolation and social withdrawal, interpersonal stress, depression, and threats to personal identity such as loss of dignity and the internalization of stereotypes. Interventions that personalize the experience, ask specific and tailored questions, support dignity through language, help patients and caregivers access self-care, and foster engagement can be powerful clinical tools in helping address AD stigma (Stites and Karlawish, 2018).

We found that both mild and moderate stages of AD dementia resulted in similarly greater stigma than no symptoms, which is consistent with the theoretical understanding of stigma as being based in over-attribution and misattribution of characteristics. This finding is relevant to preparing for the translation of the preclinical AD construct from research into routine practice. While the finding is expected – given it is consistent with theoretical understanding of stigma as being based in over-attribution and misattribution of characteristics – it shows that stigma resultant from mild symptoms was generally similar to that resultant from moderate symptoms. This suggests that individuals living with preclinical AD are likely to experience an increase in stigma with the appearance of symptoms. Moreover, the stigma they experience should be appreciated by clinicians as being equivalent to that placed upon individuals in more severe stages of disease. Clinicians may need to directly address stigma associated with symptoms as patients progress from cognitively unimpaired to impaired.

Successfully addressing public beliefs and behaviors that contribute to AD stigma may involve large-scale public campaigns. Efforts to reduce AD stigma through education and messaging may be most effective if they target specific attributions. We found, for example, that expectations a person would be distanced and isolated from social relationships showed a more than 55% increase in the positive vs negative biomarker conditions (OR=1.55, Cohen’s d=0.22). This finding lends itself to media messaging that can address these types of instrumental concerns about dementia and, more specifically, draw public attention to the consequences of social isolation and offer suggestions for confronting it. Because mass media messaging campaigns can have unintended consequences, such as making it seem like all individuals with AD are severely impaired (Cho and Salmon, 2007; Hoyt et al., 2014; Puhl et al., 2013), empirically informed campaigns with ongoing evaluation are fundamental to the appropriateness and success of such efforts.

Public policy changes may be able to help reduce public stigma, or at the least, protect persons living with AD from discriminatory and predatory practices. We found, for example, that worries about structural discrimination showed a more than doubling of odds in the positive vs negative biomarker conditions (OR=2.63, Cohen’s d=0.55). A key change to public policy that could potentially improve the wellbeing of persons living with AD biomarkers would be extending the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA) (“Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008,” n.d.) to biomarker results. Currently GINA offers certain protections against gene-based discrimination, but no comparable protections extend to biomarker testing results (Arias et al., 2018; Largent et al., 2021).

Research on cancer and other conditions suggests that, because advances in diagnosis and treatment can change how a person is impacted by the disease, stereotypes and stigma associated with the disease can also shift (Knapp et al., 2014; Nakash et al., 2020). How advances in diagnosis and treatment will change AD stigma over time is an empirical question that warrants tracking as new advances are translated into routine care as some interventions aimed at mitigating stigma may become obsolete while new challenges may also emerge.

4.4. Robustness of Results and Limitations

In this study, we measured multiple domains of stigma and used multiple complementary approaches to analysis. Our findings are consistent. Cell sizes between groups were equal or similar. To check that differences in group sizes did not impact our conclusions, we conducted weighted analyses and found the results to be similar. Moreover, our sample appears representative of the English-speaking U.S. population based on basic demographic characteristics. However, post-randomization, 9.6% of those who identified as Latino dropped out compared to only 2.3% of those who identified otherwise. A similar pattern was observed for race, where 10.0% of those who identified as a race other than White dropped out while only 2.3% of those who identified as White did. These patterns may be because our survey was offered only in English. Thus, while our sample was demographically similar to the broader U.S. population along key dimensions such as race, education, and gender, this is unlikely to be the case for language. While disparities in dropout were observed based on race and ethnicity, overall dropout from the study was minimal (<4%).

Strengths of this study include that the sample was invited at random from a large national panel and that the large sample of over 1800 respondents had a demographic composition fairly consistent with that of the nation’s general adult population. The response rate was 63% and completion rate was 96%. Moreover, the design of our study permitted us to control for potential confounding from both respondent characteristics and the vignette character’s age and gender. Nonetheless, reactions of the public may differ based on personal characteristics, such as being identified with certain races, ethnicities, or socio-economic groups (Stites et al., 2018, 2016). In addition, we did not vary the race or ethnicity of the person in the vignette. Thus, it’s unknown how varying the person’s race and ethnicity would modify the results we found in our study. Lastly, while we piloted tested the vignettes for readability and authenticity, it is possible that some respondents did not recognize all possible implications of the content.

4.5. Future Research

The current study focused on characterizing the main effects of biomarker test result, treatment availability, and symptom severity on stigma, as measured by the FS-ADS. In addition, given its relevance to the emerging construct of preclinical AD, we also examined the treatment-availability condition in biomarker-positive cases. We found treatment had no measureable effect on stigma. Future studies will be essential for investigating how observer (respondent) and patient characteristics such as age and gender moderate the effects reported in this study. Moreover, our analyses of study attrition showed demographic patterns in groups that prematurely discontinued participation. This warrants future study. Given the increasing diversity of older Americans, underrepresentation of minorities in AD research, and elevated risk of dementia borne by Black-, African- and Latino-Americans, future studies should evaluate the impact of race and ethnicity on AD stigma.

The general public remains is largely naive to the varied pathologies that fall under the umbrella of dementia with Alzheimer’s being the most commonly recognized cause of dementia. We found in a prior study that the features of stigma most often associated with stigma of AD notably did not include some of the behavior symptoms associated with other causes of dementia and focused heavily on cognitive symptoms (Stites et al., 2018). Given the conflation between “Alzheimer’s” and “dementia” in the general public, we hypothesize that stereotypes associated with dementia are likely to conform closely to those of AD. However, as public understanding of the pathologies and clinical presentations that fall under the umbrella of dementia increase, we might expect the public’s preconceived notions of dementia to also evolve. This would be a relevant area for future study, as understanding how the public’s perceptions might be changing over time may be helpful for informing public campaigns.

Use of preclinical diagnostic labels in AD and other conditions has gained momentum with advances in gene and biomarker technologies. The extension of diagnostics from clinical to preclinical applications raises questions about how – as shown in the current study – stigma associated with clinical conditions may spill over to impact individuals diagnosed in preclinical stages of disease. The implications of this phenomenon are key for understanding individuals’ willingness to seek care and for their quality of life post-diagnosis. It is notable that in some cases the preclinical diagnosis has stigma associated with it (Scherr et al., 2017) and that the treatment associated with that diagnosis also has stigma associated with it (Kenen et al., 2007). Thus, ongoing research in this area is essential for understanding both the effects of emerging preclinical conditions as well as their treatments.

Our study focused on a definition of disease-modifying therapy as one that slows the disease. Based on our understanding of the literature and our study’s results, stigma can shift but does not disappear with introduction of disease-modifying therapies. However, if a disease can be eradicated or near eradicated, stigma associated with the disease can also dissipate, as the disease fades from collective memory (Dougan, 2020). This underscores the need for ongoing research to investigate how the particular nature of scientific advances can shape the patient and family experience of AD stigma.

4.6. Conclusion

This study shows that the stigma of AD, which reflects the stigma of dementia, spills over into preclinical AD. We are unable to conclude that the availability of treatment will alter that stigma. These findings have important implications on the future of advances in AD diagnosis and treatment. They suggest that translation of the preclinical AD construct from research into routine practice will require interventions that mitigate AD stigma to promote the uptake of treatment and preserve the dignity of individuals living with preclinical AD.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

An experimental vignette-based survey of general US public

A biomarker-based “pre-dementia” diagnosis caused stigma

Treatment at this stage of AD did not reduce stigma

The stigma of dementia may spill over to persons with pre-dementia diagnosis

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jordyn Crossan for her assistance organizing materials, and Nina Miller for her assistance with graphics.

Support.

This work was supported by grants from the Alzheimer’s Association (AARF-17-528934), the University of Pennsylvania Alzheimer’s Disease Center (NIA P30 AG 010124), and the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America (No grant #). This publication is the result of work conducted by the CDC Healthy Brain Research Network. The CDC Healthy Brain Research Network is a Prevention Research Centers program funded by the CDC Healthy Aging Program-Healthy Brain Initiative. Efforts were supported in part by cooperative agreement U48 DP - 005053. The views of this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Stites was supported by the National Institute on Aging (1K23AG065442). Dr. Largent was supported by the National Institute on Aging (K01AG064123) and the Greenwall Faculty Scholars Program (No grant #).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Human Participant Protection

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania approved all procedures involving human subjects.

Credit Author Statement

S. Stites wrote the initial draft of the article. S. Stites, J. Karlawish, and A. Krieger conducted and interpreted the analyses. All authors contributed to conceptualizing and writing the article.

Contributor Information

Shana D. Stites, Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatrics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Jeanine Gill, University of Pennsylvania, Perelman School of Medicine, Division of Geriatrics, Philadelphia, PA.

Emily A. Largent, Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Kristin Harkins, University of Pennsylvania, Perelman School of Medicine, Division of Geriatrics, Philadelphia, PA.

Pamela Sankar, University of Pennsylvania, Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy, Philadelphia, PA.

Abba Krieger, University of Pennsylvania, Wharton School of Business, Department of Statistics, Philadelphia, PA.

Jason Karlawish, Penn Memory Center, Departments of Medicine, Medical Ethics and Health Policy, and Neurology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association National Plan Milestone Workgroup, Fargo KN, Aisen P, Albert M, Au R, Corrada MM, DeKosky S, Drachman D, Fillit H, Gitlin L, Haas M, Herrup K, Kawas C, Khachaturian AS, Khachaturian ZS, Klunk W, Knopman D, Kukull WA, Lamb B, Logsdon RG, Maruff P, Mesulam M, Mobley W, Mohs R, Morgan D, Nixon RA, Paul S, Petersen R, Plassman B, Potter W, Reiman E, Reisberg B, Sano M, Schindler R, Schneider LS, Snyder PJ, Sperling RA, Yaffe K, Bain LJ, Thies WH, Carrillo MC, 2014. 2014 Report on the Milestones for the US National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement 10, S430–452. 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.08.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s vaccine shows promise in Phase II trial, n.d.. European Pharmaceutical Review. URL https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/news/156676/alzheimers-vaccine-shows-promise-in-phase-ii-trial/ (accessed 10.29.21).

- American Community Survey (ACS) [WWW Document], n.d. The United States Census Bureau. URL https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs (accessed 4.28.20).

- Anderson LA, Egge R, 2014. Expanding efforts to address Alzheimer’s disease: The Healthy Brain Initiative. Alzheimers Dement 10, S453–S456. 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.05.1748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias JJ, Tyler AM, Oster BJ, Karlawish J, 2018. The Proactive Patient: Long-Term Care Insurance Discrimination Risks of Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers. J. Law. Med. Ethics 46, 485–498. 10.1177/1073110518782955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batsch NL, Mittelman MS, 2012. World Alzheimer Report 2012. Overcoming the stigma of dementia. http://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2012.

- Chan BT, Tsai AC, 2016. Trends in HIV-related Stigma in the General Population During the Era of Antiretroviral Treatment Expansion: An Analysis of 31 Sub-Saharan African Countries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 72, 558–564. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Salmon CT, 2007. Unintended Effects of Health Communication Campaigns. Journal of Communication 57, 293–317. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00344.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Scott Roberts J, McLaughlin SJ, 2007. Public opinion about Alzheimer disease among blacks, hispanics, and whites: results from a national survey. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 21, 232–240. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181461740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corner L, Bond J, 2004. Being at risk of dementia: Fears and anxieties of older adults. Journal of Aging Studies 18, 143–155. 10.1016/j.jaging.2004.01.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, 2007. How Clinical Diagnosis Might Exacerbate the Stigma of Mental Illness. Social Work 52, 31–39. 10.1093/sw/52.1.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, 2006. Mental Health Stigma as Social Attribution: Implications for Research Methods and Attitude Change. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 7, 48–67. 10.1093/clipsy.7.1.48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler SJ, Hodgson LG, 1996. Anticipatory Dementia: A Link Between Memory Appraisals and Concerns About Developing Alzheimer’s Disease. The Gerontologist 36, 657–664. 10.1093/geront/36.5.657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougan G, 2020. Opinion: How we lost our collective memory of epidemics [WWW Document]. University of Cambridge. URL https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/collectivememory (accessed 10.29.21). [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM, 2013. HIV Stigma Mechanisms and Well-Being Among PLWH: A Test of the HIV Stigma Framework. AIDS Behav 17, 1785–1795. 10.1007/s10461-013-0437-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food & Drug Administration, 2020. November 6, 2020: Meeting of the Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting Announcement [WWW Document]. FDA. URL https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/november-6-2020-meeting-peripheral-and-central-nervous-system-drugs-advisory-committee-meeting (accessed 1.14.21).

- French SL, Floyd M, Wilkins S, Osato S, 2012. The Fear of Alzheimer’s Disease Scale: a new measure designed to assess anticipatory dementia in older adults: Anticipatory dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 27, 521–528. 10.1002/gps.2747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 [WWW Document], n.d.. National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). URL https://www.genome.gov/24519851/Genetic-Information-Nondiscrimination-Act-of-2008 (accessed 7.21.17). [Google Scholar]

- Hagan RJ, Campbell S, 2021. Doing their damnedest to seek change: How group identity helps people with dementia confront public stigma and maintain purpose. Dementia 147130122199730. 10.1177/1471301221997307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt CL, Burnette JL, Auster-Gussman L, 2014. “Obesity Is a Disease”: Examining the Self-Regulatory Impact of This Public-Health Message. Psychological Science 25, 997–1002. 10.1177/0956797613516981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL, 1982. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry 140, 566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, Holtzman DM, Jagust W, Jessen F, Karlawish J, Liu E, Molinuevo JL, Montine T, Phelps C, Rankin KP, Rowe CC, Scheltens P, Siemers E, Snyder HM, Sperling R, Contributors, 2018. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 14, 535–562. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R, Harkins K, Cary M, Sankar P, Karlawish J, 2015. The relative contributions of disease label and disease prognosis to Alzheimer’s stigma: A vignette-based experiment. Social Science & Medicine 143, 117–127. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EE, 1984. Social Stigma: The Psychology of Marked Relationships. W. H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, 2003. HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary HIV counselling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sexually Transmitted Infections 79, 442–447. 10.1136/sti.79.6.442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenen RH, Shapiro PJ, Hantsoo L, Friedman S, Coyne JC, 2007. Women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutations Renegotiating a Post-Prophylactic Mastectomy Identity: Self-Image and Self-Disclosure. Jrnl of Gene Coun 16, 789–798. 10.1007/s10897-007-9112-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp S, Marziliano A, Moyer A, 2014. Identity threat and stigma in cancer patients. Health Psychol Open 1, 2055102914552281. 10.1177/2055102914552281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Largent EA, Harkins K, van Dyck CH, Hachey S, Sankar P, Karlawish J, 2020. Cognitively unimpaired adults’ reactions to disclosure of amyloid PET scan results. PLoS ONE 15, e0229137. 10.1371/journal.pone.0229137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Largent EA, Stites SD, Harkins K, Karlawish J, 2021. ‘That would be dreadful’: The ethical, legal, and social challenges of sharing your Alzheimer’s disease biomarker and genetic testing results with others. Journal of Law and the Biosciences 8, lsab004. 10.1093/jlb/lsab004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SE, Hong M, Casado BL, 2021. Examining public stigma of Alzheimer’s disease and its correlates among Korean Americans. Dementia 20, 952–966. 10.1177/1471301220918328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening EL, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP, 1989. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review 54, 400–423. 10.2307/2095613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC, 2001. Conceptualizing Stigma. Annual Review of Sociology 27, 363–385. 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Shepherd BE, Li C, Harrell FE, 2017. Modeling continuous response variables using ordinal regression: Modeling continuous response variables using ordinal regression. Statistics in Medicine 36, 4316–4335. 10.1002/sim.7433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Lopez C, Tariot PN, Caputo A, Langbaum JB, Liu F, Riviere M, Langlois C, Rouzade-Dominguez M, Zalesak M, Hendrix S, Thomas RG, Viglietta V, Lenz R, Ryan JM, Graf A, Reiman EM, 2019. The Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative Generation Program: Study design of two randomized controlled trials for individuals at risk for clinical onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 5, 216–227. 10.1016/j.trci.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakash O, Granek L, Cohen M, David MB, 2020. Association Between Cancer Stigma, Pain and Quality of Life in Breast Cancer. Psychology, Community & Health 8, 275–287. 10.5964/pch.v8i1.310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T, Li X, 2020. Understanding public-stigma and self-stigma in the context of dementia: A systematic review of the global literature. Dementia 19, 148–181. 10.1177/1471301218800122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl R, Luedicke J, Lee Peterson J, 2013. Public Reactions to Obesity-Related Health Campaigns. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 45, 36–48. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Michaelis A, Weiss E, Brown L, Mahendra V, 2010. Reducing HIV-Related Stigma: Lessons Learned from Horizons Research and Programs. Public Health Rep 125, 272–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rewerska-Juśko M, Rejdak K, 2020. Social Stigma of People with Dementia. JAD 78, 1339–1343. 10.3233/JAD-201004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronchetto F, Ronchetto M, 2021. Biological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and the issue of stigma. JGG 69, 195–207. 10.36150/2499-6564-N327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosin ER, Blasco D, Pilozzi AR, Yang LH, Huang X, 2020. A Narrative Review of Alzheimer’s Disease Stigma. JAD 78, 515–528. 10.3233/JAD-200932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherr CL, Bomboka L, Nelson A, Pal T, Vadaparampil ST, 2017. Tracking the Dissemination of a Culturally Targeted Brochure to Promote Awareness of Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer among Black Women. Patient Educ Couns 100, 805–811. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Karlawish J, Donohue M, Salmon DP, Aisen P, 2014. The A4 Study: Stopping AD Before Symptoms Begin? Science Translational Medicine 6, 228fs13–228fs13. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stites SD, Johnson R, Harkins K, Sankar P, Xie D, Karlawish J, 2016. Identifiable Characteristics and Potentially Malleable Beliefs Predict Stigmatizing Attributions Toward Persons With Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia: Results of a Survey of the U.S. General Public. Health Communication 1–10. 10.1080/10410236.2016.1255847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stites SD, Karlawish J, 2018. Stigma of Alzheimer’s disease dementia: considerations for practice. Practical Neurology. [Google Scholar]

- Stites SD, Rubright JD, Karlawish J, 2018. What features of stigma do the public most commonly attribute to Alzheimer’s disease dementia? Results of a survey of the U.S. general public. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 14, 925–932. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner P, Giveon SM, 2008. Discriminatory behavior of family physicians toward a person with Alzheimer’s disease. International Psychogeriatrics 20. 10.1017/S1041610208007060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner P, Goldstein D, Buchbinder E, 2010. Subjective Experience of Family Stigma as Reported by Children of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Qualitative Health Research 20, 159–169. 10.1177/1049732309358330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner P, Goldstein D, Heinik J, 2011. Development and Validity of the Family Stigma in Alzheimerʼs Disease Scale (FS-ADS): Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders 25, 42–48. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f32594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner P, Kim S, 2021. A Cross-National Study of Dementia Stigma Among the General Public in Israel and Australia. JAD 83, 103–110. 10.3233/JAD-210277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.