Abstract

Purpose:

We surveyed healthcare providers to determine the extent to which they discuss transition-to-adulthood topics with autistic patients without intellectual disability.

Methods:

74 healthcare providers in the Philadelphia area reported on the patient age at which they begin transition conversations, topics covered, and provider comfort. We calculated the proportion of providers who endorsed each transition topic, overall and by clinical setting.

Results:

Providers initiated transition-related conversations at a median age of 16 years (IQR: 14, 18), with over half reporting they were “somewhat” or “a little” comfortable with discussions. Nearly all providers discussed at least one healthcare, well-being, and mental health topic, while basic need-related discussions were limited.

Conclusions:

Results suggest providers may delay and feel poorly prepared to provide anticipatory guidance to autistic patients for transition to adulthood. Future efforts to enhance the available resources and preparation available to providers are essential to meet autistic patients’ needs.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, transition to adult care, delivery of healthcare, adolescent health services, quality of life, activities of daily living

Introduction

Despite becoming legally able to make independent decisions regarding healthcare and other basic needs at age 18, autistic adolescents experience barriers to independence and maintaining quality of life during the transition to adulthood [1,2]. Given the complexity of navigating multiple systems when planning for independence, as well as the coinciding end of educational and other services, autistic adolescents and their families may benefit from individualized planning [3,4]. Of particular concern for families during this transition is preparing for health-related independence [5].

Healthcare providers are important resources for autistic adolescents preparing for adulthood. Autistic adolescents have longstanding relationships with their healthcare providers, who often support families through other developmental transitions that engender trust [5]. They are more likely to receive healthcare than neurotypical peers [5–7]. However, autistic adolescents are less likely than peers with other special healthcare needs to receive health- and well-being-related anticipatory guidance [8–10]. By examining healthcare providers’ transition planning practices, we can identify resource needs and approaches to help providers support autistic patients and their families. Our objective was to examine healthcare providers’ behaviors and comfort discussing transition topics with autistic patients without intellectual disability.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of pediatric healthcare providers recruited from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Philadelphia Autism Centers for Excellence. Eligible participants included physicians, advanced practice professionals, psychologists, and social workers who provided medical or mental healthcare to adolescent patients. We recruited from general and subspecialty pediatrics, including adolescent medicine, developmental pediatrics, psychiatry, and neurology. Email recruitment occurred during Spring 2019 (up to three emails/participant). This study was exempt from IRB review.

We administered an anonymous survey using the Research Electronic Data Capture tool (REDCap) [11]. Our prior research and literature review regarding autistic adolescents’ transition to adulthood informed the survey [5,12]. Participants reported demographic and practice characteristics, the proportion of their patients who have diagnosed autism without intellectual disability (hereafter “autistic patients”), the proportion of autistic patients with whom and the age at which they discuss transition, their comfort discussing transition, and who (parent, patient, or self) initiates transition-related conversations. Participants indicated whether they discussed each of 16 transition topics, informed by the Adolescent Life Skills Inventory, a tool to identify readiness for independence [13]. We summarized categorical demographic and practice characteristics using frequencies and percentages. For each transition topic, we reported the proportion of providers endorsing each topic overall and by clinical setting (e.g., outpatient medical, pediatric subspecialty, behavioral health). We classified topics into four higher-level categories: physical health, mental health, well-being, and basic needs. Data were analyzed using SAS (Version 9.3).

Results

We distributed 829 recruitment emails and received 144 responses (17.4% response rate). Table 1 summarizes demographic and practice characteristics for the 74 respondents who provided transition-related care to autistic patients.

Table 1.

Provider Characteristics (N=74).

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 60 (81%) |

| Male | 14 (19%) |

| Age | |

| 25–34 | 20 (27%) |

| 35–44 | 24 (32%) |

| 45–54 | 18 (24%) |

| 55–64 | 9 (12%) |

| >65 | 3 (4%) |

| Clinical Role | |

| Attending Physician | 40 (54%) |

| Fellow Physician | 2 (3%) |

| Social Worker | 5 (7%) |

| Psychiatrist | 1 (1%) |

| Psychologist | 15 (20%) |

| Nurse Practitioner | 4 (5%) |

| Other | 7 (9%) |

| Years in Practice | |

| 0–4 | 17 (23%) |

| 5–10 | 20 (27%) |

| 11–15 | 11 (15%) |

| 16–20 | 8 (11%) |

| >20 | 18 (24%) |

| % of Autistic Patients | |

| <25% | 52 (70%) |

| 26–50% | 15 (20%) |

| 51–75% | 1 (1%) |

| 76–100% | 6 (8%) |

| Clinical Setting a | |

| Outpatient Medical | 31 (42%) |

| Pediatric Subspecialty | 18 (24%) |

| Pediatric Mental / Behavioral Health | 25 (34%) |

Outpatient Medical includes providers whose primary affiliation was Primary Care or Adolescent Medicine; Pediatric Subspecialty includes providers whose primary affiliation was Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Neurology, or other specialty care setting; Mental/Behavioral Health includes providers whose primary affiliation was Psychiatry or other mental health setting.

Transition-related conversations were initiated at a median age of 16 years (IQR: 14, 18). Over half of providers (56.8%) reported being only “somewhat” or “a little” comfortable discussing transition, while 36.5% reported they were “very comfortable” and 6.8% “extremely comfortable.” Most providers (75.7%) reported “often” or “always” initiating conversations; alternatively, providers reported only 12% of parents “often” or “always” did so and autistic patients themselves never or rarely initiated conversations (77.0%).

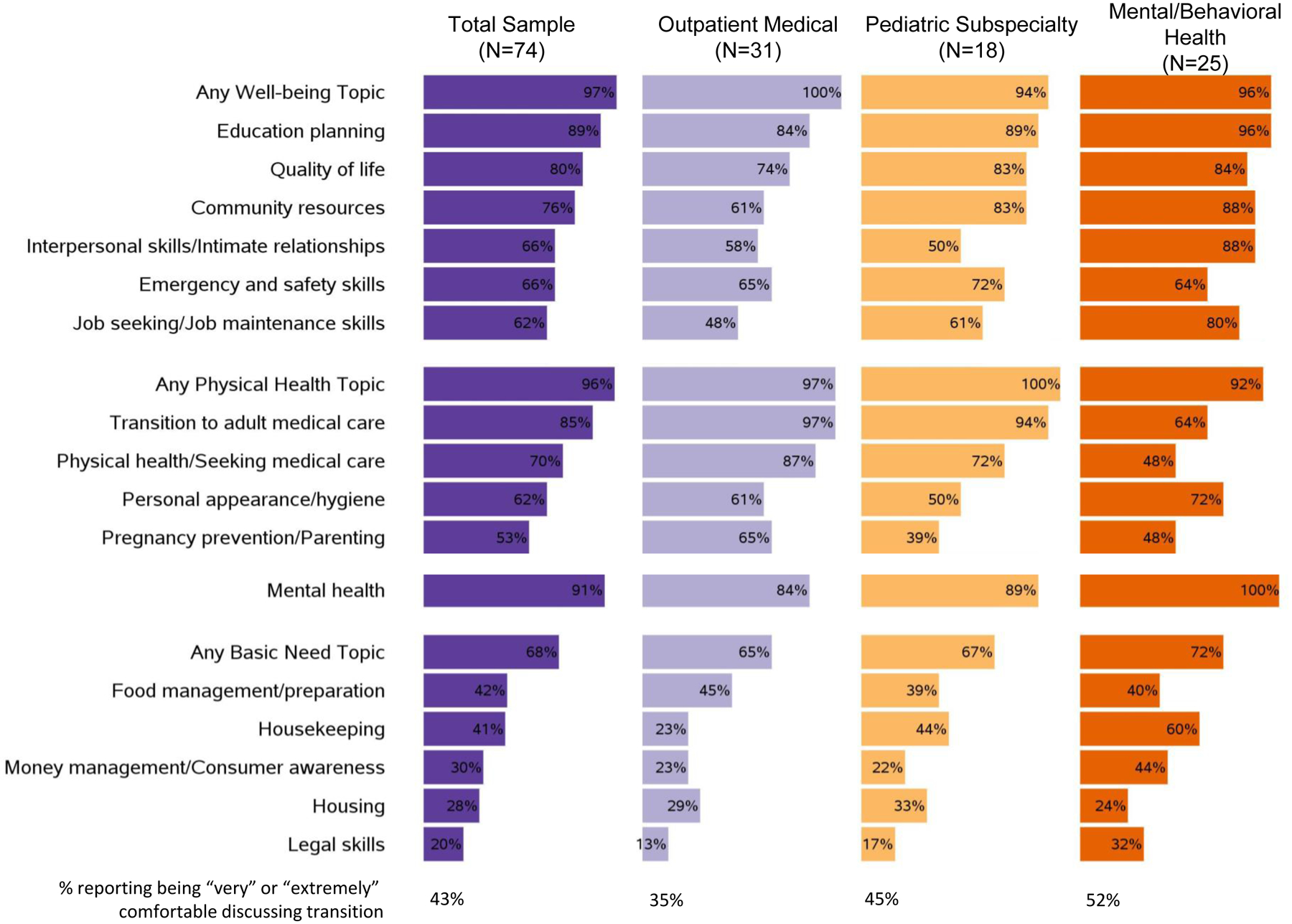

Figure 1 describes the proportion of providers who discussed each transition topic and comfort discussing transition. While nearly all providers discussed at least one well-being (97% overall) and one physical health (96% overall) topic, within these categories, certain topics such as interpersonal skills and pregnancy prevention, were limitedly discussed. Over 90% of providers discussed mental health. A smaller percentage of providers (68% overall) reported discussing basic needs (e.g., housing, food management), with behavioral health providers representing the largest proportion of providers discussing such topics.

Figure 1. Proportion of Providers who Endorsed Each Transition Topic and Comfort Discussing Transition.a.

a Topics are presented in rank order within higher-level category (well-being, physical health, mental health, basic needs) overall and by each clinical setting.

Discussion

We found conversations regarding transition and independence were initiated by providers during mid to late adolescence. Slightly over half of providers endorsed limited comfort initiating discussions. The timing of transition discussions converges with prior research [14], but contrasts with recommendations to begin transition planning in early adolescence [15,16]. This delay limits providers’ ability to prepare patients for independence related to health and well-being and may contribute to perceptions of an abrupt or premature transition to independence [4]. Data suggest pediatric and adult providers fail to implement recommended transition strategies, in part due to practice-based systemic barriers to care and transition planning[14,17], which may contribute to decreases in healthcare engagement following adulthood transition. An urgent need exists to refine the resources available to support earlier and routine discussion of independence.

Basic needs were the least commonly discussed topics across all clinical settings, despite adolescents’ perceived importance of these skills in maintaining health and their desire to build health-related autonomy [18,19]. While tools to support providers with transition planning are in development [20], our results highlight an on-going need to create resources that can be used across clinical settings and among diverse providers to adhere to recommendations and prepare patients for independence.

Our results only reflect provider experiences with autistic adolescents without intellectual disability. We did not inquire about other common comorbidities and did not include patient perspectives. We are currently conducting complementary studies with adolescent and parent dyads, including interviews and a longitudinal cohort study. Further, participating providers may be more comfortable with transition planning than non-responders, about whom we have no information. Results may not generalize to all healthcare settings and providers. However, participants reflected the diversity of clinical settings in which autistic adolescents receive healthcare and in on-going work we are conducting interviews with providers to explore possible differences by professional role.

Given the long-standing and trusting relationship between pediatric healthcare providers and their autistic patients, providers are well-positioned to deliver anticipatory guidance regarding transition to adulthood. However, providers reported limited comfort discussing transition and our on-going research will examine how provider experiences with autistic patients without intellectual disability interacts with their confidence regarding transition. Our results highlight a continued need to develop and disseminate provider resources to support autistic adolescents’ emerging independence, while addressing the structural barriers to successful transition-related care, such as family readiness, termination of services, and challenges accessing adult providers for autistic patients.

Implications and Contribution:

We examined healthcare providers’ discussions of transition to adulthood topics with autistic patients. While providers commonly initiated conversations, they often delayed conversations until later adolescence and focused on limited transition topics. Results highlight a need to develop resources and tools to support providers in preparing autistic patients for adulthood.

Acknowledgements:

We gratefully acknowledge the study participants for their time and willingness to share their experiences and perspectives. Further, we recognize the assistance of clinical leadership at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia care network and the Philadelphia Autism Centers for Excellence for facilitating data collection. We thank Rania Mansour, MPH, Miriam Monahan, OTD, MS OTR/L, CDRS, CDI, Julie Lounds Taylor, PhD, Jessica Hafetz Mirman, PhD, and Patty Huang, MD, for their thoughtful review of the study survey. We appreciate the expertise of Meghan Carey, MPH and Haley Bishop, PhD, for their thoughtful review of this manuscript and the expertise of Kristina B. Metzger, PhD, MPH for her assistance in preparing the manuscript figure. This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health Awards R01HD079398 and R01HD096221 (PI: Curry). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Preliminary results were accepted for presentation at the 2020 International Society for Autism Research annual meeting and the 2020 Pediatric Academic Society (PAS) annual meeting. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, preliminary results were only presented at the virtual PAS meeting.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors have real or perceived potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Cheak-Zamora NC, Teti M, First J. “Transitions are Scary for our Kids, and They’re Scary for us”: Family Member and Youth Perspectives on the Challenges of Transitioning to Adulthood with Autism. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 2015;28:548–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hendricks DR, Wehman P. Transition From School to Adulthood for Youth With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 2009;24:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Richard J, Duncan A. Transition from adolescence to adulthood in those without a comorbid intellectual disability. Interprofessional Care Coordination for Pediatric Autism Spectrum Disorder: Translating Research into Practice, Springer International Publishing; 2020, p. 169–83. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Anderson KA, Sosnowy C, Kuo AA, et al. Transition of Individuals With Autism to Adulthood: A Review of Qualitative Studies. Pediatrics 2018;141:S318–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cheak-Zamora NC, Teti M. “You think it’s hard now … It gets much harder for our children”: Youth with autism and their caregiver’s perspectives of health care transition services. Autism 2015;19:992–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cummings JR, Lynch FL, Rust KC, et al. Health Services Utilization Among Children With and Without Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2016;46:910–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Weiss JA, Isaacs B, Diepstra H, et al. Health Concerns and Health Service Utilization in a Population Cohort of Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2018;48:36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cheak-Zamora NC, Yang X, Farmer JE, et al. Disparities in transition planning for youth with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics 2013;131:447–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Graham Holmes L, Shattuck PT, Nilssen AR, et al. Sexual and Reproductive Health Service Utilization and Sexuality for Teens on the Autism Spectrum. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics : JDBP 2020;41:667–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zablotsky B, Rast J, Bramlett MD, et al. Health Care Transition Planning Among Youth with ASD and Other Mental, Behavioral, and Developmental Disorders. Maternal and Child Health Journal 2020;24:796–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Myers RK, Bonsu JM, Carey ME, et al. Teaching Autistic Adolescents and Young Adults to Drive: Perspectives of Specialized Driving Instructors. Autism in Adulthood 2019;1:202–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Life Skills Inventory: Independent Living Skills Assessment Tool. Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/healthtr/resources/tools/checklists.html.

- [14].Ames JL, Massolo ML, Davignon MN, et al. Transitioning youth with autism spectrum disorders and other special health care needs into adult primary care: A provider survey. Autism 2021;25:731–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bennett AE, Miller JS, Stollon N, et al. Autism Spectrum Disorder and Transition-Aged Youth. Current Psychiatry Reports 2018;20:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hagan JF J, Shaw JS, Duncan PM. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. vol. 34. 4th ed. Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Shattuck PT, Orsmond GI, Wagner M, et al. Participation in social activities among adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder. PLoS ONE 2011;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nicolaidis C, Raymaker DM, Ashkenazy E, et al. “Respect the way I need to communicate with you”: Healthcare Experiences of Adults on the Autism Spectrum. Autism 2015;19:824–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cheak-Zamora NC, Teti M, Maurer-Batjer A. Capturing Experiences of Youth With ASD via Photo Exploration: Challenges and Resources Becoming an Adult. Journal of Adolescent Research 2018;33:117–45. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cheak-Zamora N, Farmer JG, Crossman MK, et al. Provider Perspectives on the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes Autism: Transition to Adulthood Program. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics : JDBP 2021;42:91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]