Abstract

Rationale & Objective

There is limited published research on how autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) impacts caregivers. This study explored how caregivers of individuals with ADPKD perceive the burdens placed on them by the disease.

Study Design

Qualitative study consisting of focus groups and interviews. Discussions were conducted by trained interviewers using semi-structured interview guides.

Setting & Participants

The research was conducted in 14 countries in North America, South America, Asia, Australia, and Europe. Eligible participants were greater than or equal to 18 years old and caring for a child or adult diagnosed with ADPKD.

Analytical Approach

The concepts reported were coded using qualitative research software. Data saturation was reached when subsequent discussions introduced no new key concepts.

Results

Focus groups and interviews were held with 139 participants (mean age, 44.9 years; 66.9% female), including 25 participants who had a diagnosis of ADPKD themselves. Caregivers reported significant impact on their emotional (74.1%) and social life (38.1%), lost work productivity (26.6%), and reduced sleep (25.2%). Caregivers also reported worry about their financial situation (23.7%). In general, similar frequencies of impact were reported among caregivers with ADPKD versus caregivers without ADPKD, with the exception of sleep (8.0% vs 28.9%, respectively), leisure activities (28.0% vs 40.4% respectively), and work/employment (12.0% vs 29.8%, respectively).

Limitations

The study was observational and designed to elicit concepts, and only descriptive analyses were conducted.

Conclusions

These findings highlight the unique burden on caregivers in ADPKD, which results in substantial emotional, social, and professional/financial impact.

Index Words: Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), burden, caregiver, quality of life

Plain-Language Summary.

A qualitative study was conducted to understand the impact of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) on caregivers of children, spouses, or parents with ADPKD. Focus groups with 139 caregivers were conducted in 14 countries to elicit experiences with caregiving and its emotional, social, physical, financial, and productivity impacts. Emotional impacts were the most frequently reported (74%), followed by social impacts (38%). Productivity, financial, and sleep impacts were reported by between 25%-27% of caregivers, followed by physical impacts as reported by 17% of caregivers.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common hereditary kidney disease, affecting over 12 million people worldwide.1,2 ADPKD is characterized by the progressive development of fluid-filled kidney cysts, resulting in increased kidney size.3 Symptoms such as pain, hematuria, and feelings of abdominal fullness typically develop in the third or fourth decade of life, but they can occur at any age.4 Other clinical manifestations and complications related to ADPKD are heterogeneous and may include hypertension, extrarenal cyst formation, cardiovascular disease, and intracranial aneurysm.2,4 An estimated 45%-70% of patients with ADPKD progress to kidney failure in their fifth or sixth decade of life and require dialysis or kidney transplantation, imposing a significant cost burden to both the affected individual and to health care systems.3,5, 6, 7, 8, 9 These serious health consequences of ADPKD have a significant impact on the individual’s health-related quality of life.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15

Family or informal caregivers play an important supportive role for patients with ADPKD throughout the disease process. Spill-over impacts of ADPKD on caregivers increase with more advanced chronic kidney disease, and these impacts have been described via health–economic assessments as indirect costs of ADPKD, which include loss of productivity because of caregiving and incremental health care costs incurred by caregivers.16

The participation of patients and caregivers in developing clinical practice guidelines is increasingly advocated for medicine in general and the management of ADPKD specifically.17,18 Further, the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Polycystic Kidney Disease (SONG-PKD) project engaged individuals with ADPKD, their caregivers, and health care professionals to establish a set of core outcome domains for assessment in ADPKD clinical trials.19 By identifying outcomes that are important to stakeholder groups, including caregivers, the SONG-PKD project aims to improve the quality and relevance of research evidence that will inform treatment decisions in ADPKD.

To gain a better understanding of the burden ADPKD places on caregivers, we conducted a qualitative study with caregivers of ADPKD patients. Discussions covered topics related to physical, emotional, social, and economic impacts and the impact on daily activities. The research was originally conceived as a companion project to investigate ADPKD-related disease burden in adolescents20 with the goal to describe the caregiving burden for parents of children with ADPKD. However, because of participant feedback, the project was expanded to also include caregiving for adult ADPKD patients.

Methods

Design

Focus groups and one-on-one interviews were conducted with caregivers of ADPKD patients in North America, Europe, Australia, Asia, and South America. Eligible caregivers were required to be at least 18 years old and caring for a child or adult diagnosed with ADPKD. The study documents were centrally reviewed and approved by the New England Institutional Review Board.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited through patient foundations, local nephrologist referrals, and advertisements. A participant screener confirmed participant eligibility in the study, and demographic information related to relevant medical/family history was collected from enrolled participants. The study initially was intended to explore the burden for caregivers of children with ADPKD. The scope of discussions was broadened after many participants spontaneously shared experiences from their other caregiving responsibilities for and relationships with ADPKD patients (eg, spouses or parents).

Discussion Process and Content

Participants consented to participate in audio-recorded group discussions or individual interviews. Where acceptable by local laws and customs, discussions were video recorded for subsequent transcription and data collection processing. Facilities with a one-way mirror and back room permitted study personnel in the adjoining room to observe the discussions while remaining unseen.

Discussions with caregivers were conducted in each country’s native language and moderated by trained interviewers using an open-ended, semi-structured discussion guide to allow for in-depth exploration of concepts. In countries where English was the native language, the study lead or designee moderated the individual interviews in person. For interviews conducted in a language other than English, simultaneous interpretation was provided for observing study staff observing in an adjacent room. Caregivers were asked to discuss their experiences caring and to what degree those experiences have impacted their daily lives, physically, emotionally, socially, and economically.

Feedback Analysis

Discussions were transcribed and coded using a qualitative research software program, HyperRESEARCH. The data were deidentified to protect participant confidentiality. A single coder (A.C.P.) captured themes and concepts based on transcript review to assess frequency and saturation of reported concepts. Data were summarized descriptively by themes, concepts, and caregiver relationship. For this study, saturation was defined as the point at which participants in subsequent discussions introduced no new key concepts or themes.

Results

One hundred thirty-nine caregivers of individuals with ADPKD (including 25 caregivers who themselves had a diagnosis of ADPKD) were interviewed in 23 focus groups and 10 one-on-one interviews across 14 countries in North America, South America, Australia, Asia, and Europe. Table 1 describes the location of concept elicitation focus groups and interviews with the number of participants and basic demographics at each location. A majority (66.9%) of the caregivers were female, and the mean age was 44.9 years (range 18-79 years). Caregivers most commonly cared for their spouse (48.9%) or parent with ADPKD (28.8%). A breakdown of the main caregiving relationship by country and sex is provided in Table 1. Participants reporting their main caregiving relationship for a child had an average age of 45.6 years, whereas participants reporting to be a caregiver for a parent had an average age of 35.7 years, and those caring for a spouse had an average age of 50.9 years.

Table 1.

Location and Number of Participants in Concept Elicitation Focus Groups and Interviews

| Region | Country | Number of Caregivers | No. (%) of Caregivers With ADPKD Diagnosis | Main Caregiver Relationship |

Mean Age, y | Number (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | Spouse | Parent | Other | Male | Female | |||||

| North America | Canada | 7 | 3 (43%) | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 41 | 2 (29%) | 5 (71%) |

| United States | 20 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 46 | 6 (30%) | 14 (70%) | |

| South America | Argentina | 10 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 34 | 2 (20%) | 8 (80%) |

| Brazil | 10 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 44 | 2 (20%) | 8 (80%) | |

| Australia | Australia | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 65 | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) |

| Asia | China | 16 | 2 (13%) | 0 | 13 | 3 | 0 | 52 | 5 (31%) | 11 (69%) |

| Japan | 5 | 2 (40%) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 47 | 1 (20%) | 4 (80%) | |

| South Korea | 12 | 2 (17%) | 2 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 54 | 4 (33%) | 8 (67%) | |

| Taiwan | 16 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 0 | 37 | 8 (50%) | 8 (50%) | |

| Europe | Czech Republic | 11 | 3 (27%) | 1 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 45 | 6 (55%) | 5 (45%) |

| Hungary | 4 | 4 (100%) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 30 | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) | |

| Poland | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 48 | 2 (40%) | 3 (60%) | |

| Romania | 5 | 3 (60%) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 43 | 1 (20%) | 4 (80%) | |

| Spain | 16 | 6 (38%) | 3 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 48 | 5 (31%) | 11 (69%) | |

| Total | Global | 139 | 25 (18%) | 23 | 67 | 40 | 9 | 44.9 | 46 (33%) | 93 (67%) |

Abbreviation: ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

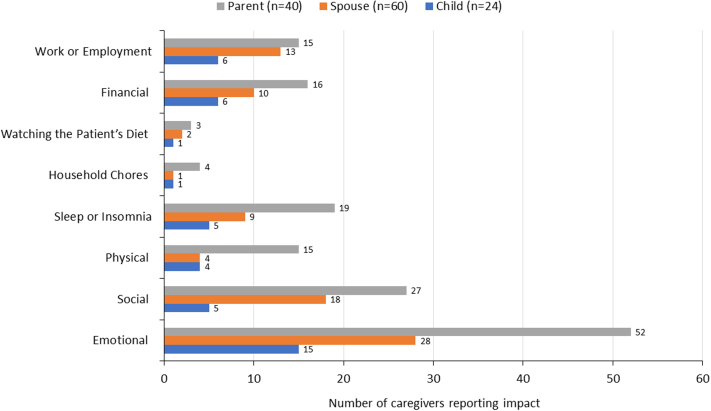

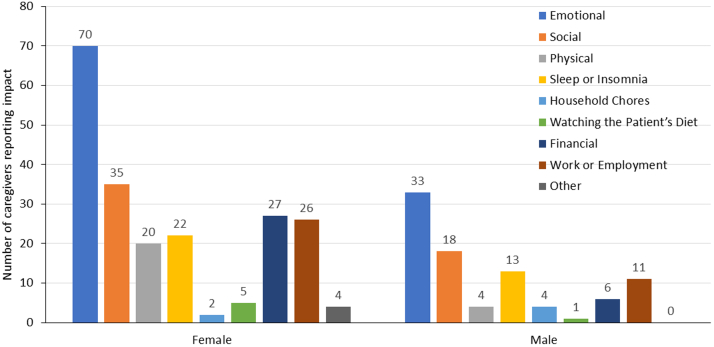

During the discussions, caregivers were asked how caring for people with ADPKD impacted their lives. Reported impacts and burdens were classified into the following domains: emotional, physical, social/leisure, work, financial, and other (sleep/insomnia, household chores, and diet restrictions) (Table 2). Concepts elicited from caregivers regarding the impact and burden of ADPKD are summarized below for each major category, including quotes from caregivers that describe each concept. Frequency of quotes relating to each domain of life are presented in Figs 1 and 2, and sample quotations are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Number of Respondents With Domain of Life Impacted by Caring for People With ADPKD Among Caregivers With and Without ADPKD

|

Domain, n (%) |

All Caregivers N=139 |

Caregivers with ADPKD n=25 | Caregivers without ADPKD n=114 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional | 103 (74%) | 18 (72%) | 85 (75%) |

| Physical | 24 (17%) | 4 (16%) | 20 (18%) |

| Social/leisure activities | 53 (38%) | 7 (28%) | 46 (40%) |

| Work/employment | 37 (27%) | 3 (12%) | 34 (30%) |

| Financial | 33 (24%) | 6 (24%) | 27 (24%) |

| Sleep/insomnia | 35 (25%) | 2 (8%) | 33 (29%) |

| Household chores | 6 (4%) | 2 (8%) | 4 (4%) |

| Watching diet | 6 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 5 (4%) |

Abbreviation: ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

Figure 1.

Number of caregivers reporting impacts for spouse, parent, and child caregiver relationship.

Figure 2.

Cumulative caregiver impacts by sex.

Table 3.

Sample Caregiver Quotations Describing the Impact of Caring for Individuals With ADPKD Across Domains of Life

| Impacted Domain | Quote | Caregiver for | Background |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional | |||

| Stress/anxiety | I feel worried about him if I go out. | Spouse | Wife (age 59 y) providing support for her husband on dialysis. |

| I am worried, but I can do nothing to it. | Spouse | Wife (age 47 y) providing support for her husband. | |

| The real problem are the attacks of pain and the fears, the omnipresent fear. | Sibling | Woman (age 35 y) providing support for her sister. | |

| It is distressing. She also worries about that… We don’t have kids, but if we have them one day… And this is more dangerous for a woman, being pregnant and having… | Spouse | Man (age 46 y) providing support for his girlfriend. | |

| I start to think about, you know, should I be worrying about transplants and organ lists and what family member has my son’s blood type and who am I going to try to tap this time to ask for a kidney, you know, so it’s that kind of stuff that you worry about. Because, as a mother, that’s your job, right. | Child | Mother (age 41 y) providing support for her adolescent son. | |

| Well, it was, uh, it was very, very difficult waiting--awaiting the test results. We knew it was a 50/50 chance, right, and, uh, it was, uh, I consider myself a more or less lucky person. It is tough to swallow not winning that coin toss. Uh, um, and now, I mean, he's still—he’s still a baby, right. He still doesn't talk so it’s very difficult. I mean, on top of having a first child and not really knowing how to handle this thing, right, and like all this potential is worry, especially when it’s baby. He can't talk, right, but ev--every time something was wrong with him it’s always in the back of your mind, what if it--what if it is. | Child | Father (age 27 y) providing support for young son. | |

| You could’ve blown me over with a feather when they told me my kid had PKD. I was shocked. And you go into the state of shock, and you think it’s going to wear off over time but it doesn’t. The shock gets worse, because it compounds into life. And then life compacts into future, and it’s a big cloud. It’s a huge cloud of worry that’s always there, and it’s so frustrating. | Child | Mother (age 40 y) providing support for adolescent daughter. | |

| Guilt/worry | I feel so miserable, I wanted to kill myself because I was so unhappy and frustrated with my life and this could be passed on to my children. | Spouse | Wife (age 46 y) providing support for husband whose mother had just died of ADPKD complications. |

| It is scary, especially when you know that it came from us, I think it is a quite big burden. | Child | Mother (age 41 y) providing support for adolescent son. | |

| Sadness | I am unhappy every day, for my husband is unhappy most of the time, which is a great impact on me. | Spouse | Wife (age 62 y) providing support for husband on dialysis. |

| I already have two children. If I didn’t have any, yes, I would have one. We had the first one, and when we decided to have the second one, the first one was still healthy. That’s why I think that the heartbreak was bigger. I wanted to have five, but with these two I stopped. | Child | Mother (age 38 y) providing support for son and daughter. | |

| Anger, frustration, and irritation | I was pretty mad at that time, blaming him for not taking good care of himself when I was away. | Spouse | Wife (age 43 y) providing support for husband who is awaiting transplant. |

| Angry, because all your advices end up in an empty pocket and even if I want to cheer her up… for me, my advice are unheard and she is the one that is sick. | Spouse | Husband (age 33 y) providing support for wife on dialysis and waiting for transplant. He wanted to donate his kidney but was not a match. Their child also has ADPKD. | |

| Sometimes I’d regret that I didn’t know he has such a disease, otherwise I wouldn’t marry him. It can’t be diagnosed during premarital check-up, and it’s inherited. | Spouse | Wife (age 38 y) providing support for husband. | |

| Nobody asks about us who support the patient. | Parent | Woman (age 31 y) providing support for her mother on dialysis. | |

| Helplessness/hopelessness | The helplessness is horrible. | Spouse | Husband (age 49 y) providing support for wife. |

| It’s too big, so at this point they just kind of...we don’t know what to do. They don’t know what to do because there’s no history. They don’t--they haven't been diagnosing kids so young. | Child | Mother (age 41 y) providing support for adolescent son. | |

| It is waste of time making plans. | Child | Father (age 39 y) providing support for son. | |

| Physical | |||

| Fatigue, exhaustion, and/or lack of energy | You can come back with no energy at all, after a full day at the hospital, and it is no recovering from that. | Spouse | Husband (age 36 y) providing support for wife. |

| So we feel tired, we feel fatigue mentally. | Parent | Woman (age 30 y) providing support for mother. | |

| Weight loss and/or poor appetite | I lost weight, 6 kg in just three months. | Parent | Woman (age 25 y) providing support for mother on dialysis. |

| I lost 7 kg in two weeks, I could not eat and was so afraid of getting a call in the middle of the night. | Parent | Man (age 31 y) providing support for father. | |

| I don’t eat right. You know, I eat once a day, if even that. I don’t have an appetite. | Child | Mother (age 40 y) providing support for son. | |

| Social/leisure activities | |||

| Limited social life | My life has changed drastically. We could not eat out anymore; we could not go to parties, because he would want to eat everything. | Spouse | Wife (age 42 y) providing support for husband. |

| If we go out too much in the same week, she then feels more tired and can’t move because of the backache. So we can’t go out too much. | Spouse | Boyfriend (age 36 y) providing support for girlfriend. | |

| Personal relationships | I don’t have time for that, to meet with friends, sometimes people drop in, but to be quite honest people are afraid. | Spouse | Husband (age 36 y) providing support for wife. |

| As if it were contagious. There is a rejection. | Spouse | Husband (age 40 y) providing support for wife. | |

| Work/Employment | |||

| Difficulty keeping job/functioning at work | I was switched because I had the schedule of 10:30 AM to 7:30 PM and they change it from 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM, precisely to be able to go there and see him. I was like: work, hospital, home…work, hospital, home. It as a triangle and now I say, how could I manage everything?” | Spouse | Wife (age 40 y) providing support for husband on dialysis. |

| Change to work situation | I get to work from home and that’s how I’m able to take care of her as well. | Parent | Son (age 35 y) providing support for mother. |

| I requested a reduced schedule to be able to spend more time with her. | Spouse | Husband (age 33 y) providing support for wife. | |

| Quit job/stopped working | I had to quit my job for taking care of her. My big brother found a job for me, but I told him that I wouldn’t go to work for I had to take care of her. I think I miss so many chances. | Spouse | Husband (age 40 y) providing support for wife. |

| I quit my job last year. | Child | Mother (age 41 y) providing support for son. | |

| Financial | |||

| Financial | Well, once she’s hospitalized, I…things like fees for the hospital, surgery, for example, I do worry about the money. | Parent | Man (age 31 y) providing support for mother. |

| I have to use money out of my savings. | Parent | Man (age 50 y) providing support for mother. | |

Abbreviation: ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

Overall, participants who had a diagnosis of ADPKD themselves reported an equal or lower impact than participants who did not have the diagnosis. Lower impact was reported in the domains of social and leisure activities (28% vs 40%), work and employment (12% vs 30%), and sleep (8% vs 29%). The domain of household chores was the only area where participants with an ADPKD diagnosis felt more impacted (8% vs 3%). A potential reason for this finding may be that caregivers diagnosed with ADPKD have experience with the disease and have accepted their situation and its limitations, whereas ADPKD-related signs and symptoms might impact their ability to perform chores.

Emotional Impact

The most frequently reported burden among caregivers was emotional impact. A majority (74.1%; n = 103) of caregivers stated that their psychological and emotional wellbeing was negatively affected by the responsibility of caring for those with ADPKD. Many caregivers expressed that they lived under constant stress and anxiety for the ADPKD-affected individual’s health status or the risk of worsening health. Most of these caregivers also stated that they worried all the time, which had a substantial impact on their life situation, making it difficult to leave home for work, participate in social and leisure activities, or travel. Caregivers expressed feelings of guilt and worry for having passed the disease to their children or the risk of passing it on to future children. Many caregivers expressed feelings of sadness for the health status of the person with ADPKD as well as for the stress caused in their own everyday lives. A few caregivers expressed feelings of anger, frustration, and irritation, which were related to the person with ADPKD not taking care of him or herself, the total hopelessness of the situation, and/or the fact that there is no cure for this disease. To be able to cope, most caregivers described using patience and handling the situation one day at a time; others simply expressed that they accepted their situation. A few caregivers expressed feelings of helplessness/hopelessness, saying that they had completely surrendered to ADPKD and had stopped making plans for the future.

Physical Impact

Physical problems resulting from caring were reported by 17.3% (n = 24) of participants. The physical impacts reported by caregivers were predominately fatigue, exhaustion, tiredness, and/or lack of energy. Weight loss was a physical impact reported by many of the caregivers and was described as a consequence of constant stress and worry. A few caregivers specifically mentioned that they had poor appetite and did not eat on a regular basis because they worried or did not have time to eat. Several caregivers reported neglecting their own physical health or that they completely stopped exercising because of the constant need for support and care.

Social and Leisure Activities Impact

Many caregivers (38.1%; n = 53) reported that their social and leisure activities had decreased significantly or stopped entirely because they did not have the time to engage in these activities. Taking care of the individual with ADPKD was their number 1 priority, and work and/or household duties were a second priority that consumed their time. Caring for a sick relative was reported to take up most of the caregiver’s time, especially caring for adults with a more advanced stage of ADPKD when dialysis and frequent hospital visits were necessary. A few caregivers reported that they hardly left home except when necessary (eg, grocery shopping or hospital appointments). For many caregivers, their social lives were very limited because of the other person’s condition and the inability to plan for activities like traveling, meeting with friends, eating out, or going to a party. A secondary impact of ADPKD on caregivers’ social lives was related to personal relationships and close friendships. Caregivers reported that friends no longer reached out or engaged in social activities due to the caregiver’s inability to plan and do things spontaneously. Caregivers expressed feelings of sadness, abandonment, and isolation in relation to these impacts.

Work and Employment Impact

Many caregivers reported that caring for a person with ADPKD impacted their work (26.6%; n = 37), leading to difficulties in either keeping a job or functioning during working hours. Work was described as a secondary priority after caregiving, with respondents trying to change their work situation to manage daily routines. For a few caregivers, working part time was an alternative to ensure an income while also providing care. Others reported that they had quit their jobs and had stopped working completely to provide care. Despite caregivers’ struggles to manage their work hours, many appreciated having a job to go to, focusing on something else for a few hours, meeting with colleagues, and keeping up social contacts outside the home.

Financial Impact

Financial impact was related to impacts on work and employment and was voiced by 23.7% (n = 33) of caregivers. The need to reduce work hours or find a part-time job to devote time to caring reportedly decreased overall income. In some cases, when a caregiver quit a job, it had a significant impact on finances. Caregivers were most concerned about the cost of care, and they worried about the availability of government or insurance funding for hospital care and treatment expenses. Many caregivers mentioned that they had to take money from their personal savings to cover health care costs. Adding to the frustration over medical costs, a few caregivers expressed their frustration that there is still “no effective treatment or cure” and that their financing of care for ADPKD might never make a difference to improve the affected individual’s condition.

Sleep, Household Chores, and Diet

Additional impacts mentioned by caregivers included concepts not specified in the interview guide but which emerged during the discussions. Reports under “other impacts” may necessitate further qualitative discussions with caregivers of persons with ADPKD to determine if concept saturation was reached.

Sleeping problems were a commonly reported impact (25.2%; n = 35). Caregivers attributed sleeping problems to worrying about the ADPKD-affected individual’s condition, as well as to frequent nighttime visits to the bathroom or snoring caused by ADPKD (possibly related to heavy pressure from the kidneys). A few caregivers reported taking sleeping pills on a regular basis to ensure they would get a sufficient amount of rest. Sleep disturbances were reported to exert a significant negative impact on physical and mental health and to increase feelings of fatigue during the day.

Caregivers reported that simultaneously being the primary person responsible for taking care of the household and for providing ADPKD-related care (such as medical appointments, dietary changes, providing emotional and physical support for the patient) was a burden.

Four percent of caregivers reported the need to provide a very restricted diet for the person affected by ADPKD. For caregivers of a child with ADPKD, this also involved ensuring that the school could offer a low sodium diet or that lunch was prepared to bring to school. Some caregivers mentioned that the dietary restrictions had an impact on where they could eat when dining outside of the home. In addition to providing a strict diet, some caregivers mentioned that they had to monitor food intake.

Discussion

This study provides insights into the impact of caring for individuals with ADPKD. Caregivers across 14 countries reported substantial effects on their daily lives because of caring for a person diagnosed with ADPKD. In addition to experiencing difficulties in their emotional and social lives, caregivers—especially those caring for adults at advanced stages of disease—lost productivity at work and had problems sleeping. Caregivers with a diagnosis of ADPKD also reported a sense of guilt for passing the disease on to their children.

The most frequently reported impact domain among caregivers was emotional impact, followed by impact on social and leisure activities and lack of sleep. Caregivers also reported that they worried about their financial and work situations and their ability to cover the cost of caring for the person with ADPKD. Physical impact received the fewest endorsements among caregivers. In general, caregivers with ADPKD reported similar frequencies of impact as caregivers without a diagnosis. However, caregivers without an ADPKD diagnosis tended to report impacts on sleep, leisure activities, and work/employment more frequently than caregivers with an ADPKD diagnosis.

Although ADPKD places a burden on caregivers, there is a lack of understanding and limited published research regarding the quality-of-life impact of caregiving in ADPKD as well as a lack of appreciation for the toll of hereditary diseases on informal or family caregivers. The SONG-PKD project has included caregivers in a survey to identify core outcomes in ADPKD but with a focus on health-related outcomes of the disease itself rather than those arising from the experience of caregiving.21 The limited nature of the research on this topic may be due in part to the lack of assessment instruments specific to the condition.

Although we set out to better define the caregiving burden on parents of children and adolescents with ADPKD, participants mostly considered their caregiving relationship with other family members to be primary. This was either because of children not having been formally diagnosed, still in early disease stages with few symptoms, or because caregiving for other family members in advanced disease stages took a priority. The reported impacts of caregiving for the main caregiver relationships (spouse, parent, child) are shown in Fig 1, with emotional impacts being the most commonly listed impact for all relationships.

Caregiving responsibilities in ADPKD, like in other diseases, often decrease predominantly on women, as shown in Fig 2; however, impacts mentioned by male caregivers are similar to those mentioned by female caregivers. Although our study did not specifically distinguish between caregivers by chronic kidney disease status of the patient, the caregiving burden reported in the literature is overall similar to what we found in our study.22 However, due to the hereditary nature of ADPKD, the caregiving impact observed in our study is pronounced in caregivers of younger patients and is also further enhanced by having multiple family members affected by the disease at the same time.

Our study included participants from 14 countries in North America, South America, Asia, Australia, and Europe. There were no regional differences in terms of the frequency of caregiver endorsements of impact domains, which were equally reported and distributed across all regions and countries, suggesting that the impact of ADPKD on caregivers may not be culturally dependent. Despite the global consistency in reported caregiver burden, the only country where we encountered professional dedicated caregivers for ADPKD patients during our research was the United States (specifically, in California), and this type of participant did not report adverse financial or work impacts due to the nature of their caregiver relationship.

The concepts identified in the present study, although obtained from the perspective of the caregiver, exhibit substantial overlap with outcomes identified by the SONG-PKD research group, including the emotional consequences of ADPKD (eg, anxiety, depression, hopelessness), fatigue, social and professional limitations, and financial consequences.21

A limitation of this study is that it was designed to elicit concepts, and as such, only descriptive analyses were conducted. Selection bias may have occurred because caregivers of individuals with more advanced or aggressive ADPKD may have been more likely to participate, as individuals with worse disease would have greater needs and limitations with more impacts on the caregiver’s life. Given that individuals with ADPKD may normalize and under-report their own symptoms,19 it is plausible that caregivers for individuals with earlier-stage disease might also minimize their care-related burdens.

Future research on how the burden of caregiving changes over time as ADPKD progresses from milder to worse manifestations would thus be informative. Similar to how research has shown that the patient experience of ADPKD differs from that of other chronic kidney diseases,19,23 the present study suggests that caregivers may face burdens, such as dietary management or nocturia, that may not be present in other chronic kidney conditions and may arise even in earlier-stage ADPKD. As the disease progresses, the burdens imposed on caregivers of individuals with ADPKD, which affect emotional and mental health, social relationships, sleep, and work and productivity impairment, may be more likely to resemble the multiple burdens raised by the late stages of other chronic kidney diseases and indeed other chronic conditions in general.24, 25, 26 Additionally, it might be useful to document caregiver relationships more formally to better anticipate support that might be needed as the disease progresses and caregiver relationships change over time.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Dorothee Oberdhan, MS, Andrew C. Palsgrove, BA, Jason C. Cole, PhD, and Tess Harris, MA

Authors’ Contributions

research idea and study design: DO; data acquisition: JCC, ACP; data analysis/interpretation: DO, ACP, TH; statistical analysis: DO, ACP; supervision or mentorship: JCC, TH. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. The sponsor participated in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Financial Disclosure

Ms Oberdhan and Mr Palsgrove are employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc (“Otsuka”). Mr Palsgrove and Dr Cole were employed by Covance Market Access Services (“Covance”) during data collection and analysis phases of this project. Covance was hired by Otsuka to conduct this study. Ms Harris is the CEO of the Polycystic Kidney Disease Charity, which has received historical grants from Otsuka UK and fees plus travel and lodging for participation in multidisciplinary medical workshops.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants in this study, without whom this research would not have been possible. The authors also thank Global Outcomes Group (Reston, VA, USA) and BioScience Communications, Inc (New York, NY, USA) for medical writing and editing services, which were funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc.

Peer Review

Received April 22, 2022. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from an Associate Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form October 16, 2022.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

References

- 1.Patel V., Chowdhury R., Igarashi P. Advances in the pathogenesis and treatment of polycystic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18(2):99–106. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283262ab0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman A.B., Devuyst O., Eckardt K.U., et al. Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): executive summary from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2015;88(1):17–27. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chebib F.T., Torres V.E. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: core curriculum 2016. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(5):792–810. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eriksson D., Karlsson L., Eklund O., et al. Health-related quality of life across all stages of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(12):2106–2111. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lentine K.L., Xiao H., Machnicki G., Gheorghian A., Schnitzler M.A. Renal function and healthcare costs in patients with polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(8):1471–1479. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00780110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee H., Manns B., Taub K., et al. Cost analysis of ongoing care of patients with end-stage renal disease: the impact of dialysis modality and dialysis access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40(3):611–622. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.34924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith D.H., Gullion C.M., Nichols G., Keith D.S., Brown J.B. Cost of medical care for chronic kidney disease and comorbidity among enrollees in a large HMO population. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(5):1300–1306. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000125670.64996.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zelmer J.L. The economic burden of end-stage renal disease in Canada. Kidney Int. 2007;72(9):1122–1129. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grantham J.J. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(14):1477–1485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0804458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnawi R.A., Attar R.Z., Alfaer S.S., Safdar O.Y. Is the light at the end of the tunnel nigh? A review of ADPKD focusing on the burden of disease and tolvaptan as a new treatment. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2018;11:53–67. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S136359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rizk D., Jurkovitz C., Veledar E., et al. Quality of life in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease patients not yet on dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(3):560–566. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02410508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miskulin D.C., Abebe K.Z., Chapman A.B., et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and CKD stages 1-4: a cross-sectional study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(2):214–226. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santoro D., Satta E., Messina S., Costantino G., Savica V., Bellinghieri G. Pain in end-stage renal disease: a frequent and neglected clinical problem. Clin Nephrol. 2013;79(suppl 1):S2–S11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suwabe T., Ubara Y., Mise K., et al. Quality of life of patients with ADPKD–Toranomon PKD QOL study: cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:179. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tong A., Rangan G.K., Ruospo M., et al. A painful inheritance-patient perspectives on living with polycystic kidney disease: thematic synthesis of qualitative research. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(5):790–800. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cloutier M., Manceur A.M., Guerin A., Aigbogun M.S., Oberdhan D., Gauthier-Loiselle M. The societal economic burden of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in the United States. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-4974-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boivin A., Currie K., Fervers B., et al. Patient and public involvement in clinical guidelines: international experiences and future perspectives. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(5):e22. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.034835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong A., Tunnicliffe D.J., Lopez-Vargas P., et al. Identifying and integrating consumer perspectives in clinical practice guidelines on autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 2016;21(2):122–132. doi: 10.1111/nep.12579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho Y., Tong A., Craig J.C., et al. Establishing a core outcome set for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: report of the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Polycystic Kidney Disease (SONG-PKD) consensus workshop. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77(2):255–263. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oberdhan D., Schaefer F., Cole J.C., Palsgrove A.C., Dandurand A., Guay-Woodford L. Polycystic kidney disease-related disease burden in adolescents with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: an international qualitative study. Kidney Med. 2022;4(3) doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2022.100415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho Y., Rangan G., Logeman C., et al. Core outcome domains for trials in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: an international Delphi survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76(3):361–373. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alshammari B., Noble H., McAneney H., Alshammari F., O’Halloran P. Factors associated with burden in caregivers of patients with end-stage kidney disease (a systematic review) Healthcare (Basel) 2021;9(9):1212. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9091212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oberdhan D., Cole J.C., Krasa H.B., et al. Development of the Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease Impact Scale: a new health-related quality-of-life instrument. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(2):225–235. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gayomali C., Sutherland S., Finkelstein F.O. The challenge for the caregiver of the patient with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(12):3749–3751. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbertson E.L., Krishnasamy R., Foote C., Kennard A.L., Jardine M.J., Gray N.A. Burden of care and quality of life among caregivers for adults receiving maintenance dialysis: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73(3):332–343. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hopps M., Iadeluca L., McDonald M., Makinson G.T. The burden of family caregiving in the United States: work productivity, health care resource utilization, and mental health among employed adults. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:437–444. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S135372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]