Cnesterodon

comprises 10 valid species occurring in the major river basins of South America. Recent ichthyofaunistic studies in the Ivaí River basin, upper Paraná River system, suggested the existence of a possible new species, which was identified as Cnesterodon sp. based on morphological characters. Currently, the use of molecular tools has proved to be fundamental in aiding phylogenetics and cataloging biodiversity; therefore, in this study, we molecularly characterize a possible new species of Cnesterodon from the Ivaí River basin encoding the mitochondrial genes Cytochrome c Oxidase, subunit I (COI), and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2). The genetic differences found showed that this species really differs from the other Cnesterodon species, indicating that it is a distinct species, which is possibly already in serious danger of extinction since its habitat often suffers from human exploitation and its distribution is restricted to only two sites in the upper Ivaí River basin, but it has disappeared in one of them.

Keywords: Atlantic Forest, COI, endangered species, endemic species, ND2

Introduction

Cnesterodon Garman 1895 comprises 10 valid species, in addition to the 2 putative new species from the Rio Grande do Sul1 and 1 from the Paraná2,3 states in Brazil. In the latter, a remarkable fish endemism is found in the upper Paraná River system, which represents one of the largest freshwater hydrographic regions in South America.4 A very representative case is the Ivaí River basin, an important left-bank tributary of the Paraná River located entirely in the Paraná State in Brazil. In this state, 11 of 21 (52.4%) of all endemic species of the upper Paraná River basin are exclusively found in the Ivaí River basin.3 In the last two decades, several taxonomic studies with fish populations from the Ivaí River basin resulted in the discovery and description of new endemic species,5–10 as well as several other putative new species like Cnesterodon sp.2,3

All species of Cnesterodon are endemic to South America and distributed in the upper Araguaia, Uruguay, and Parana-Paraguay river basins, and in coastal drainages from São Paulo State to Argentina, as well as in small basins in western Argentina.11–14 Given the high degree of endemism, at least eight species have a restricted geographic distribution in a few river basins.11–14 They are viviparous fish with sizes ranging from 4 to 5 cm, popularly known as “barrigudinhos” or “guarus,”11,15 classified in the category of small-size fishes, the group of fishes most endangered in Brazilian territory.”16 In fact, some species of Cnesterodon already are listed in threat categories by International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) mainly in the Atlantic Forest biome.16,17

Cnesterodon hypselurus described from the Paranapanema River basin in the upper Paraná River system is mainly diagnosed by the presence of a dark brown longitudinal band along both flanks as an autapomorphy.18 The species is endemic to streams in the Paraná State and its distribution is restricted to the Cilada and Lambari rivers (both tributaries of the Capivari River), part of the Itararé River basin, an unnamed tributary of the Guaricanga River, and a first-order stretch of the Arroio do Gica Stream, both tributaries of the Tibagi River basin.11,12,18–22

Shibatta et al19 proposed that C. hypselurus was threatened with extinction in the Tibagi River basin due to the high degree of degradation, entering only in 2014 on the Official National List of Endangered Fauna Species—Aquatic Fishes and Invertebrates23 and subsequently in 2018 in the Brazilian Red Book of Endangered Species.17 However, the species is no longer classified under any threat category in the most recent document published by the Brazilian government (see Portaria do Ministério do Meio Ambiente N° 148 of June 7, 2022).24

Until recently, only C. hypselurus was known from the upper Paraná River system; however, Frota et al,2 in their study on fish inventory in the Ivaí River basin, suggested the existence of a possible new species of Cnesterodon, which was identified as Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí inhabits only the upper section of this basin.1,2,25 Later, in a recent catalog of freshwater fish from the Paraná State, Reis et al3 maintained the species as possibly new in the Ivaí River basin. Morphologically, the absence of a very prominent dark brown longitudinal band along body sides (longitudinal band along body faint) and the presence of dark bars on sides of body vertically short, mostly confined to midline, covering less than four scales in a transverse row, never extending to dorsal and ventral profiles distinguishes it from C. hypselurus.

Molecular tools are becoming prominent in aiding phylogenetics and cataloging biodiversity, contributing to the correct identification of species when the real biodiversity cannot be detected by traditional taxonomy and systematic methods based only on morphology.26–30 In fact, to contribute to knowledge regarding the diversity of species of Cnesterodontini, molecular methods have been used for the correct delimitation of species, discovering hidden biodiversity and, promising phylogeographic and phylogenetic advances for this tribe, for example.31,32 Among the markers used, mitochondrial markers, such as Cytochrome c Oxidase subunit I (COI), proposed by Hebert et al,33 have become a powerful tool in identifying individuals, also assisting in the identification of cryptic species, with complex taxonomies, or poorly studied.30,33 The NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2), has also proven to be a promising marker to identify variation in distinct lineages, as well as haplotypic variation.34,35

Given the limited morphological evidence available to characterize the new species, this study aims to molecularly characterize the population of Cnesterodon from the Ivaí River basin using the mitochondrial genes COI and ND2. Our conclusions can reaffirm the importance of the correct taxonomic identification to suppress the shortfalls of biodiversity, as well as the contribution to the understanding of phylogenetic relationships of this group and to evaluate the real diversity in Cnesterodon, which may help future conservation projects for small-sized fishes.

Material and Methods

Sample collection

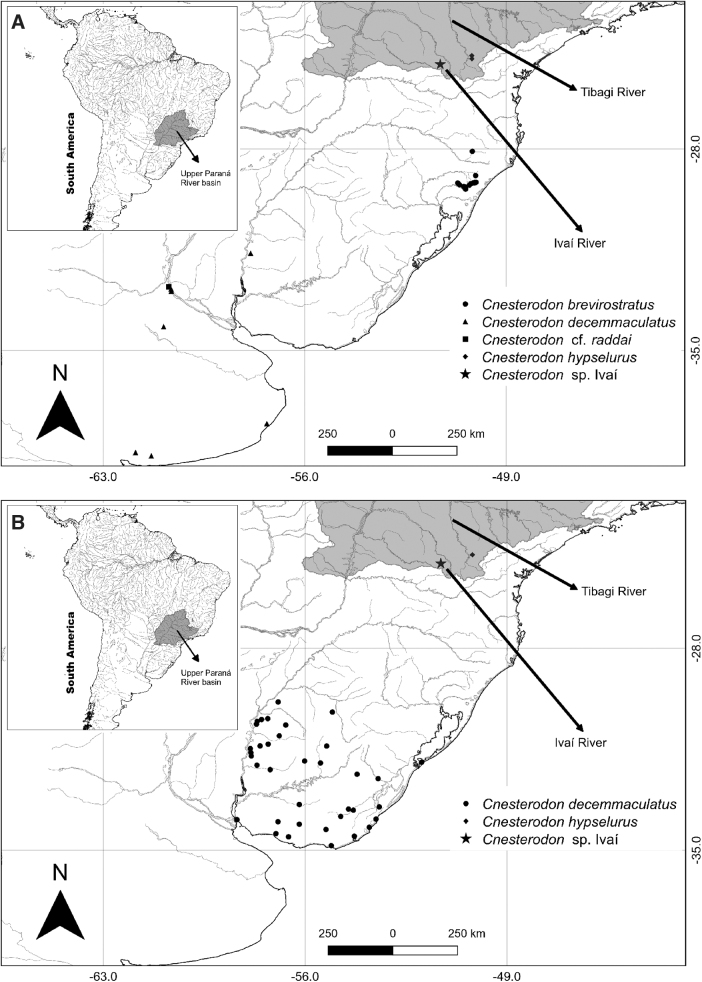

Specimens identified as C. hypselurus (NUP 15659, Lajeado Maria Leme Stream, −24.7594444, −50.2002778 [n = 10] and NUP 20200, Santa Terezinha River, −24.8694444, −50.1958333, Tibagi River basin [Fig. 1], upper Paraná River system [n = 10]) and Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí (NUP 15429, unnamed stream, tributary of the São Francisco River, −25.0644444, −51.2944444, Ivaí River basin [Fig. 1], upper Paraná river system [n = 5]) were collected using electrofishing. Afterward, the specimens were anesthetized according to the protocols of resolution 1000/2012 of the Federal Council of Veterinary Medicine.

FIG. 1.

Geographical distribution of samples analyzed in this study. (A) Partial sequences from the COI gene (Supplementary Table S1). (B) Partial sequences from the ND2 gene (Supplementary Table S2). COI, Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I; ND2, NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2.

The individuals were fixed in 92 GL alcohol and deposited in the Ichthyological Collection of the Núcleo de Pesquisas em Limnologia, Ictiologia e Aquicultura da Universidade Estadual de Maringá (NUP), Maringá, Brazil. The sampling was carried out with a favorable decision (002/2012 and 5680160117) from the Ethical Conduct Committee on the Use of Animals in Experimentation (CEUA) of UEM and a permanent license for collection and transport of zoological material SISBIO (ICMBio), process n. 14028-1 of December 10, 2008 to Weferson J. da Graça.

Molecular analysis

For the extraction of genetic material, from muscle tissue samples of the specimens, the Promega® DNA extraction kit was used, following the manufacturer's guidelines. The quantification of DNA occurred through electrophoresis in 1% agarose gel, by comparison with DNA λ of known concentration. The COI and NADH Dehydrogenase Subunit 2 (ND2) genes were partially amplified, with COI using the primer pair indicated by Ivanova et al36 for fish: H7152 (5′ CAC CTCA GGG TGT CCG AAR AAY CAR AA 3′) and L6448-F1 (5′ TCA ACC AAC CAC AAA GAC ATT CGG CAC 3′) and ND2 with the primer pair indicated by Park et al37: t-Met (5′ AAG CTA TCG GGC CCA TAC CC 3′) and C-Tpr (5′ CTG AGG GCT TTG AAG GCC C).

The amplification reactions occurred in the ProFlex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) system thermal cycler, making up a total volume of 25 μL, containing 10 ng of template DNA, Tris-KCl (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.4 and 50 mM KCl), MgCl2 (1.5 mM), 2.5 μM of each primer, dNTP (0.1 mM each), and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase. The temperatures used in PCR were as proposed by Ivanova et al,36 initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, 94°C for 30 s, hybridization at 52°C for 40 s, and elongation at 72°C for 1 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 52°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 1 min. PCR products were visualized on 1% agarose gel, purified with polyethylene glycol-NaCl (PEG-NaCl),38 and subsequently sequenced using the Big Dye Terminator kit, and nucleotide sequence determination occurred on an ABI 3500 automated sequencer in the ACTGene Molecular Analysis laboratory.

The sequences obtained in this study were edited using the BioEdit 7.2 program.39 Subsequently, the sequence identity was verified with GenBank (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) using the “Blastn” tool and they were aligned by the ClustalW 1.6 algorithm40 implemented in the MEGA X v.10.2.4 program.41 DNA sequences of the COI and ND2 gene from other Cnesterodon species were obtained from GenBank and Bold Systems and added to the analysis, these being COI (Fig. 1A): Cnesterodon decemmaculatus (n = 17); Cnesterodon cf. raddai (n = 4); and Cnesterodon (n = 68; deposited with the genus only, referred to here as Cnesterodon brevirostratus based on genus distribution12,13) and ND2 (Fig. 1B): C. hypselurus (n = 1) and C. decemmaculatus (n = 99). Fundulus heteroclitus was used as an outgroup (GenBank accession No.; COI: MT456014; ND2: KJ878751) (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

MEGA X v.10.2.4 was used to calculate gene distances between all species evaluated using the Kimura-2-Parameter (K2P) nucleotide substitution model. To construct the gene trees, identical haplotypes were excluded using the online tool ElimDupes (https://hcv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/HCV/ToolsOutline.html). The dendrogram was constructed using the maximum likelihood estimation method on the RAxML online server (https://raxml-ng.vital-it.ch/#) with the substitution matrix HKY + G for COI and the substitution matrix TN93+I for ND2 with 100 bootstrap. The best evolutionary model was estimated by MEGA X v.10.2.4. The Poisson Tree Processes (PTP) online server (https://species.h-its.org) was used for species delimitation, using the ND2 molecular marker.

Access to the genetic heritage of the species was authorized by the National System for Management of Genetic Heritage and Associated Traditional Knowledge (SisGen) under the registration number A3708EB. The sequences obtained were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MZ544717–MZ544721 (COI) and OP369308–OP369311 (ND2).

Results

Partial sequences of the COI gene (575 bp) were obtained from 3 specimens of C. hypselurus and 2 of Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí, and 2 haplotypes identified for C. hypselurus and 1 for Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí, together with those in the databases, total 32 haplotypes, with the haplotype Hap_28 having the greatest number of representatives, with a total of 16 specimens. The haplotypes Hap_4, Hap_8, and Hap_9 were shared between C. decemmaculatus and C. brevirostratus, while Hap_7 was shared between C. cf. raddai and C. brevirostratus (Supplementary Table S3). Considering the sequences obtained in this study, the final alignment showed 38 informative parsimony sites and counted 38 polymorphic sites. K2P genetic distance values are presented in Table 1 and ranged from 3.84% (between C. decemmaculatus and C. cf. raddai) to 8.19% (between C. cf. raddai and C. hypselurus). The distance obtained between C. hypselurus and Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí was ∼7.76%.

Table 1.

Interspecific and Intraspecific Kimura-2-Parameter Distances for Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí., Cnesterodon hypselurus, Cnesterodon decemmaculatus, Cnesterodon cf. raddai, Cnesterodon brevirostratus, and Fundulus heteroclitus for the COI Gene

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | Intraspecific | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) F. heteroclitus | n/c | |||||

| (2) Cnesterodon Ivaí | 22.51 | 0 | ||||

| (3) C. hypselurus | 24.50 | 7.76 | 0.12 | |||

| (4) C. decemmaculatus | 23.75 | 4.44 | 7.92 | 2.76 | ||

| (5) C. cf. raddai | 25.10 | 4.94 | 8.19 | 3.84 | 0 | |

| (6) C. brevirostratus | 23.52 | 4.22 | 7.26 | 3.85 | 4.83 | 2 |

Values are represented in percentage.

n/c: Cases in which it was not possible to estimate evolutionary distances.

COI, Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I.

For the ND2 gene, partial sequences were obtained from two specimens of C. hypselurus and two of Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí with 909 bp. Two haplotypes were identified as C. hypselurus and two as Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí, together with those in the databases, total 30 haplotypes, with haplotype Hap_13 presenting the highest number of individuals, with a total of 13 specimens. Haplotypes were not shared between different species (Supplementary Table S4). The final alignment showed 89 informative parsimony sites and counted 92 polymorphic sites. K2P genetic distance values are presented in Table 2 and range from 8.18% (between C. decemmaculatus and Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí) to 12.37% (between C. hypselurus and C. decemmaculatus). The distance obtained between C. hypselurus and Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí was ∼12.06%. Interspecific distance values (Tables 1 and 2) ranged around the 2% threshold, with C. decemmaculatus having the greatest variation for COI (2.7%) and ND2 (0.58%).

Table 2.

Interspecific and Intraspecific Kimura-2-Parameter Distances for Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí, Cnesterodon hypselurus, Cnesterodon decemmaculatus, and Fundulus heteroclitus for the ND2 Gene

| (1) | (2) | (3) | Intraspecific | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) F. heteroclitus | n/c | |||

| (2) Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí | 68.55 | 0.02 | ||

| (3) C. hypselurus | 63.61 | 12.06 | 0.04 | |

| (4) C. decemmaculatus | 64.55 | 8.18 | 12.37 | 0.06 |

Values are represented in percentage.

n/c: Cases in which it was not possible to estimate evolutionary distances.

ND2, NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2.

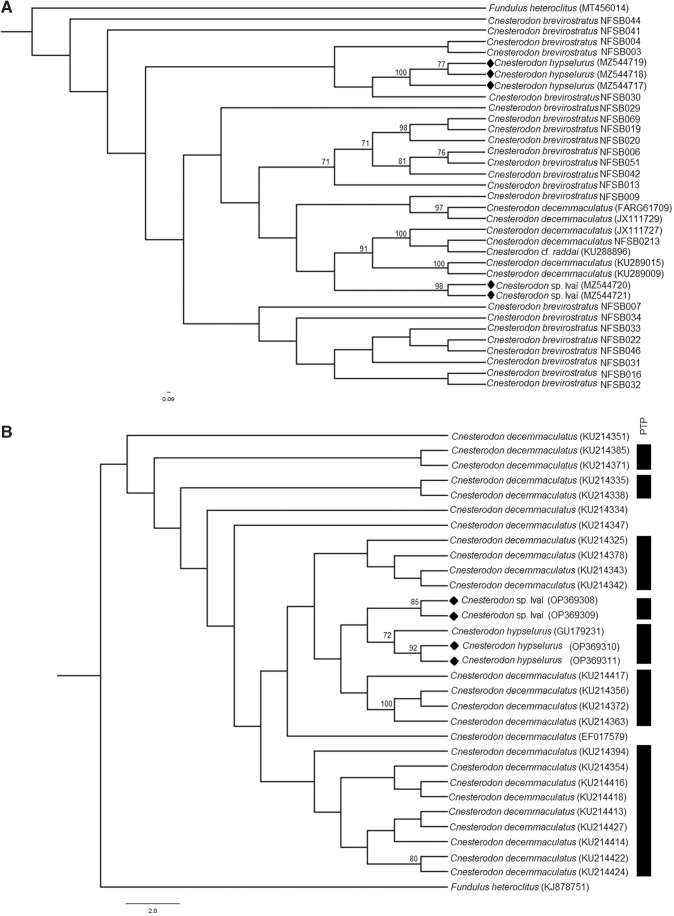

According to the gene tree obtained using the maximum likelihood, for the COI region, Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí was closer to a large cluster formed by most Cnesterodon, C. decemmaculatus, and C. cf. raddai and more distant from the cluster formed by C. hypselurus (Fig. 2A). For the ND2 region, the possible new species from the Ivaí river basin was close to C. hypselurus, but the PTP species delimitation test recognized them as different species (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Maximum likelihood dendrogram showing the relationships among the unique haplotypes of Cnesterodon, with 100 bootstrap resamples. Support values evidenced >70%. Sequences obtained in this work are identified with a black diamond. (A) Partial sequences from the COI gene. (B) Partial sequences from the ND2 gene and the species delimited by the PTP test. PTP, Poisson Tree Processes.

Discussion

Molecular results allowed the identification of a new species of Cnesterodon in the Ivaí River basin, considering the genetic distance values presented between the specimens analyzed and the species delimitation test. Furthermore, the relationships verified in the COI gene tree indicate that this new species is more distant from C. hypselurus, the only species recorded in the upper Paraná River system until then than from species in other river basins.

The genetic distance values with the COI gene between the most morphologically different species, that is, Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí and C. decemmaculatus and C. cf. raddai, were around 4.0%–5.0%. These values represent the lowest found for the species analyzed in this work and are lower than that found among Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí and C. hypselurus, that is, morphologically closer species that inhabit the upper Paraná River system.

The ND2 gene showed the best result in the species delimitation test with PTP, identifying a total of seven possible species. This is probably due to the fact that the values of genetic distances were higher for this molecular marker. In addition, a deep phylogenetic discussion is not possible with our data; however it is possible to verify that C. decemmaculatus is a species complex, as it did not form a monophyletic group in our results (Fig. 2A, B). C. brevirostratus was also not recovered with a monophyletic clade in our results (Fig. 2A); this shows that a taxonomic and phylogenetic reanalysis with all species of Cnesterodon is necessary to better understand the phylogenetic relationships and the species diversity in the genus.

The evolutionary biogeography of Cnesterodontini is closely related to several alternative episodes of dispersal and extinction of ancestral lineages, mainly in the geological boundaries between the drainages of the La Plata River system, including the upper and lower Paraná, Iguaçu, and Uruguay.31,42 Thus, despite the lower morphological proximity, Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí probably has a greater degree of ancestry with other species outside the upper Paraná River system, as its ancestor may have reached the upper Ivaí River basin by successive dispersal due to headwater captures in mountain ranges in southern South America.25,29,42

In addition, more distant ancestors between Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí and C. hypselurus could have gone extinct in the upper Paraná River basin due to climatic changes over geological time, which resulted in a substantial contraction of tropical climates to lower latitudes, further reducing the amount of habitat available and promoting rigorous climatic conditions for neotropical fish.25,43,44 In fact, in the most recent review of the spatial distribution patterns of the fish community in the Ivaí River basin, Frota et al25 proposed that there is a strong interaction with the geoclimatic variables along the basin, which most likely results in niche- and dispersal-based processes acting together to explain the spatial fish distribution patterns in the basin and, consequently, the evolutionary processes.

In biogeographic aspects, there are higher rates of turnover among the upper Ivaí River basin and the other sections of the basin probably due to inadequate dispersal capacity and environmental preference to suitable locations in its headwaters.25 These patterns of fish metacommunities found in the Ivaí River basin help to explain the high rate of endemism in the basin, especially in its upper section, where populations of Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí are probably governed by species triage due to geoclimatic characteristics and limited by dispersal due to the accentuated dendritic network of this section.25 In this context, isolated fish populations in headwaters are expected to be highly structured genetically,45 promoting local speciation,46 restriction, and rarity in mountain streams from the upper Ivaí River basin over time.47

Several studies have been using DNA barcode with sequences of the COI gene for species identification, for example.27,28,30,48–50 Considering the 2% divergence threshold as the cutoff value for species delimitation proposed by Hebert et al,33 sequences with genetic distance values above this threshold can be considered distinct species. For specimens of C. hypselurus, the divergence was only 0.12%, ∼65 times smaller than the divergence between the specimens of Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí and C. hypselurus (7.76%).

Comparing our findings with Bingpeng et al,51 the mean interspecific distance values 31 times higher than the mean intraspecific distance, obtaining species differentiation by means of the COI gene; it can be stated that Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí and C. hypselurus are distinct species, different from the others studied in this work. Regarding intraspecific variation, Cnesterodon e C. decemmaculatus showed the highest distance values, above the 2% threshold, suggesting possible misidentification of the specimens available in the databases for C. decemmaculatus and the presence of different species in the group identified only as Cnesterodon.

Freshwater environments face unprecedented anthropogenic threats, such as fisheries exploitation, pollution, unnatural invasion of invasive species, and global climate changes52–54 entailing threats to aquatic biodiversity worldwide and especially in the Ivaí River basin, for example.55 In that regard, when it comes to biodiversity conservation, the correct identification of species is crucial for monitoring and management, especially regarding the identification of a new taxon. Despite specimens of Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí having been collected within a municipal preservation area, the park's surroundings suffer strong human pressure due to deforestation and land use for agriculture, as it is possible that pesticides and other contaminants are introduced into the stream.

The first known specimens of Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí were captured in 2003 (seven specimens) and 2007 (two specimens) in the Mlot River by Graça WJ, but in 2014 surveys at the same site, specimens of this species were not found. In addition, the Mlot River has been heavily silted up due to deforestation, in addition to agricultural impacts and unregulated ecotourism in its waterfall. Therefore, it is very likely that the population of Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí has suffered harmful impacts and, in a more pessimistic scenario, no longer occurs in the Mlot River.

Additional sampling in other streams in the region with the same characteristics as the Mlot River was conducted, but without success in capturing new specimens. Considering that several species of Cnesterodon (e.g., Cnesterodon carnegiei, Cnesterodon iguape, and Cnesterodon omorgmatos) and other Cnesterodontini are listed in the Red Book of the Brazilian Fauna Threatened with Extinction,17 applying the criteria established by the IUCN categories and criteria (IUCN Standards and Petitions Subcommittee, 2022)56 and in case the species is described in the future without additional population data, Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí should be evaluated as Critically Endangered (CR), because its distribution is restricted to only two sites in the upper Ivaí River basin, and it has disappeared in one of them.

Moreover, despite being in a protected municipal area, it suffers strong anthropic pressures in the surrounding area (as cited above in the discussion). There is no record of any other population in similar environments in the region, and few mature individuals have been captured.

If our findings materialize in the description of Cnesterodon sp. Ivaí, another species of the genus could be in serious danger of extinction. Unfortunately, this is an expected fact since the occurrence of the largest numbers of endangered cnesterodontins is really in the Atlantic Forest in sites of modest-sized aquatic environments invariably with restricted geographic distributions.16 This context has been emphasized in potential locations17 in the conservation status assessments of Brazilian freshwater fish species with populations in highly degraded and fragmented landscapes like the Atlantic Forest.16,17

Taking into account the importance of good species delimitation to management proposals and environmental conservation, even more so for endemic and endangered species, in this study, we praise that genetic tools are an interesting way to help in difficulties encountered by other techniques. In conclusion, considering that species classification is critical, one can state that the species of Cnesterodon are an interesting group for integrative analysis involving cytogenetic and molecular data, as well as complementary taxonomic analysis, which could support more refined hypotheses involving evolutionary approaches and phylogenetic relationships, allowing a better theoretical framework about fish diversification in threatened freshwater ecosystems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to Francisco Alves Teixeira (Nupélia), Wladimir Marques Domingues (Nupélia), and Rodrigo Junio da Graça (Nupélia) for their aid in the field trip; to Marli Cristina Campos (Nupélia) for cataloging the vouchers; and to Nupélia and PEA for the logistic support.

Authors' Contributions

W.J.G. and A.F. conceived investigations and collected the specimens. J.P.M.-S., A.V.O., B.S., and G.G. designed and performed the molecular analyses. All authors interpreted the data and wrote the article.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This study was financed by Fundação Araucária (SETI-PR)—Convenant 199/2013, 471/2013 and process number 10558/2016 (002/2017-FA-UEM) to W.J.G. and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—CNPq, Grant/Award Number: 305200/2018-6 and 307089/2021-5 (W.J.G.) and 141236/2019-1 (J.P.M.-S.).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Bertaco VA, Ferrer J, Carvalho FR, et al. Inventory of the freshwater fishes from a densely collected area in South America—A case study of the current knowledge of Neotropical fish diversity. Zootaxa 2016;4138(3):401–440; doi: 10.11646/ZOOTAXA.4138.3.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frota A, Deprá GC, Petenucci LM, et al. Inventory of the fish fauna from Ivaí River basin, Paraná State, Brazil. Biota Neotrop 2016;16(3):e20150151; doi: 10.1590/1676-0611-BN-2015-0151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reis RB, Frota A, Deprá GC, et al. Freshwater fishes from Paraná State, Brazil: An annotated list, with comments on biogeographic patterns, threats, and future perspectives. Zootaxa 2020;4868(4):451–494; doi: 10.11646/ZOOTAXA.4868.4.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borges PP, Dias MS, Carvalho FR, et al. Stream fish metacommunity organisation across a Neotropical ecoregion: The role of environment, anthropogenic impact and dispersal-based processes. PLoS One 2020;15(5):e0233733; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Graça WJ, Pavanelli CS. Characidium heirmostigmata, a new characidiin fish (Characiformes: Crenuchidae) from the upper rio Paraná basin, Brazil. Neotrop Ichthyol 2008;6(1):53–56; doi: 10.1590/s1679-62252008000100006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roxo FF, Zawadzki CH, Troy WP. Description of two new species of Hisonotus Eigenmann & Eigenmann, 1889 (Ostariophysi, Loricariidae) from the rio Paraná-Paraguay basin, Brazil. Zookeys 2014;395:57–78; doi: 10.3897/zookeys.395.6910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tencatt LFC, Britto MR, Pavanelli CS. A new species of Corydoras Lacépède, 1803 (Siluriformes: Callichthyidae) from the upper rio Paraná basin, Brazil. Neotrop Ichthyol 2014;12(1):89–96; doi: 10.1590/S1679-62252014000100009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zawadzki CH, Roxo FF, da Graca WJ. Hisonotus pachysarkos, a new species of cascudinho from the rio Ivai basin, upper rio Parana system, Brazil (Loricariidae: Otothyrinae). Ichthyol Explor Freshw 2016;26(4):373–383. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reis RB, Frota A, Fabrin TMC, et al. A new species of Cambeva (Siluriformes, Trichomycteridae) from the Rio Ivaí basin, Upper Rio Paraná basin, Paraná State, Brazil. J Fish Biol 2020;96(2):350–363; doi: 10.1111/jfb.14204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dias AC, Zawadzki CH. Hypostomus hermanni redescription and a new species of Hypostomus (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) from Upper Paraná River Basin, Brazil. Neotrop Ichthyol 2021;19(2):e200093; doi: 10.1590/1982-0224-2020-0093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lucinda PHF. Family Poeciliidae. In: Check List of the Freshwater Fishes of South and Central America. (Reis RE, Kullander SO, Ferraris CJ, Jr. eds.) EDIPUCRS: Porto Alegre, 2003; pp. 555–581. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lucinda PHF. Systematics of the genus Cnesterodon Garman, 1895 (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae: Poeciliinae). Neotrop Ichthyol 2005;3(2):259–270; doi: 10.1590/s1679-62252005000200003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lucinda PHF, Litz T, Recuero R. Cnesterodon holopteros (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae: Poeciliinae), a new species from the Republic of Uruguay. Zootaxa 2006;1350(1):21–31; doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.1350.1.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aguiler G, Mirand JM, Azpelicuet MLM. A new species of Cnesterodon (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae) from a small tributary of arroyo Cuñá-Pirú, río Paraná basin, misiones, Argentina. Zootaxa 2009;2195(1):34–42; doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.2195.1.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Malabarba L, Carvalho Neto P, Bertaco V, et al. Tramandaí River Basin Fish Identification. Ed. Via Sapiens: Porto Alegre; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Castro RMC, Polaz CNM. Small-sized fish: The largest and most threatened portion of the megadiverse neotropical freshwater fish fauna. Biota Neotrop 2020;20(1):e20180683; doi: 10.1590/1676-0611-BN-2018-0683 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Red Book of the Brazilian Fauna Threatened with Extinction: Volume VI-Fishes. ICMBio/MMA: Brasília; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lucinda PH, Garavello JC. Two new species of Cnesterodon Garman, 1895 (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae) from the Upper Rio Parana drainage. Comun do Mus Ciencias e Tecnol da PUCRS Ser Zool 2000;13(2):119–138. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shibatta O, Orsi M, Bennemann S, et al. Diversity and Distribution of Fishes in the Tibagi River Basin. In: The Tibagi River Basin. (Medri ME, Bianchini E, Shibatta OA, Pimenta JA. eds.) M.E. Medri: Londrina, 2002; pp. 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lucinda PHF, Reis RE. Systematics of the subfamily Poeciliinae Bonaparte (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae), with an emphasis on the tribe Cnesterodontini Hubbs. Neotrop Ichthyol 2005;3(1):1–60; doi: 10.1590/s1679-62252005000100001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Langeani F, Castro RMC, Oyakawa OT, et al. Diversidade da ictiofauna do Alto Rio Paraná: Composição atual e perspectivas futuras. Biota Neotrop 2007;7(3); doi: 10.1590/s1676-06032007000300020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. da Silva JFM, Jerep FC, Bennemann ST. New record and distribution extension of the endangered freshwater fish Cnesterodon hypselurus (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae) in the upper Paraná River basin, Brazil. Check List 2015;11(6):1811; doi: 10.15560/11.6.1811 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Official National List of Species of Fauna Threatened with Extinction—Fish and Aquatic Invertebrates. MMA Ordinance No. 445, of December 17, 2014. Official Journal of the Union 2014;245:126–130. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ministry of Environment (MMA). Ordinance No. 148, of June 7, 2022. Official Journal of the Union 2022;108:74–163. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Frota A, Ganassin MJM, Pacifico R, et al. Spatial distribution patterns and predictors of fish beta-diversity in a large dam-free tributary from a Neotropical floodplain. Ecohydrology 2022;15(2):e2376; doi: 10.1002/eco.2376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bickford D, Lohman DJ, Sodhi NS, et al. Cryptic species as a window on diversity and conservation. Trends Ecol Evol 2007;22(3):148–155; doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hubert N, Hanner R, Holm E, et al. Identifying Canadian freshwater fishes through DNA barcodes. PLoS One 2008;3(6):e2490; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ward RD, Hanner R, Hebert PDN. The campaign to DNA barcode all fishes, FISH-BOL. J Fish Biol 2009;74(2):329–356; doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2008.02080.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morais-Silva JP, De Oliveira AV, Fabrin TMC, et al. Geomorphology influencing the diversification of fish in small-order rivers of neighboring basins. Zebrafish 2018;15(4):389–397; doi: 10.1089/zeb.2017.1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pereira LHG, Castro JRC, Vargas PMH, et al. The use of an integrative approach to improve accuracy of species identification and detection of new species in studies of stream fish diversity. Genet 2021;149(2):103–116; doi: 10.1007/S10709-021-00118-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ramos-Fregonezi AMC, Malabarba LR, Fagundes NJR. Population genetic structure of Cnesterodon decemmaculatus (Poeciliidae): A freshwater look at the Pampa biome in Southern South America. Front Genet 2017;8:214; doi: 10.3389/fgene.2017.00214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thomaz AT, Carvalho TP, Malabarba LR, et al. Geographic distributions, phenotypes, and phylogenetic relationships of Phalloceros (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae): Insights about diversification among sympatric species pools. Mol Phylogenet Evol 2019;132:265–274; doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2018.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hebert PDN, Cywinska A, Ball SL, et al. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 2003;270(1512):313–321; doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dowling TE, Martasian DP, Jeffery WR. Evidence for multiple genetic forms with similar eyeless phenotypes in the blind cavefish, Astyanax mexicanus. Mol Biol Evol 2002;19(4):446–455; doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kavalco KF, Pazza R, Brandão KDO, et al. Comparative cytogenetics and molecular phylogeography in the group Astyanax altiparanae—Astyanax aff. bimaculatus (Teleostei, Characidae). Cytogenet Genome Res 2011;134(2):108–119; doi: 10.1159/000325539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ivanova NV, Zemlak TS, Hanner RH, et al. Universal primer cocktails for fish DNA barcoding. Mol Ecol Notes 2007;7(4):544–548; doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01748.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Park LK, Brainard MA, Dightman DA, et al. Low levels of intraspecific variation in the mitochondrial DNA of chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta). Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol 1993;2(6):362–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rosenthal A, Coutelle O, Craxton M. Large-scale production of DNA sequencing templates by microtitre format PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 1993;21(1):173–174; doi: 10.1093/nar/21.1.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hall TA. BIOEDIT: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 1994;22(22):4673–4680; doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, et al. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol 2018;35(6):1547–1549; doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Frota A, Morrone JJ, da Graça WJ. Evolutionary biogeography of the freshwater fish family Anablepidae (Teleostei: Cyprinodontiformes), a marine-derived Neotropical lineage. Org Divers Evol 2020;20(3):439–449; doi: 10.1007/s13127-020-00444-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tedesco PA, Oberdorff T, Lasso CA, et al. Evidence of history in explaining diversity patterns in tropical riverine fish. J Biogeogr 2005;32(11):1899–1907; doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01345.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Albert JS, Carvalho TP. Neogene Assembly of Modern Faunas. In: Historical Biogeography of Neotropical Freshwater Fishes. (Albert JS, Reis RE. eds.) University of California Press: City of Berkeley, CA, 2011; pp. 118–136; doi: 10.1525/california/9780520268685.003.0007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Thomaz AT, Christie MR, Knowles LL. The architecture of river networks can drive the evolutionary dynamics of aquatic populations. Evolution 2016;70(3):731–739; doi: 10.1111/evo.12883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Carvajal-Quintero J, Villalobos F, Oberdorff T, et al. Drainage network position and historical connectivity explain global patterns in freshwater fishes' range size. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116(27):13434–13439; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1902484116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Frota A, Pacifico R, da Graça WJ. Selecting areas with rare and restricted fish species in mountain streams of Southern Brazil. Aquat Conserv Mar Freshw Ecosyst 2021;31(6):1269–1284; doi: 10.1002/aqc.3566 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mabragaña E, de Astarloa JMD, Hanner R, et al. DNA barcoding identifies argentine fishes from marine and brackish waters. PLoS One 2011;6(12):e286655; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pereira LHG, Maia GMG, Hanner R, et al. DNA barcodes discriminate freshwater fishes from the Paraíba do sul River Basin, São Paulo, Brazil. Mitochondrial DNA 2011;22(Suppl 1):71–79; doi: 10.3109/19401736.2010.532213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pereira LHG, Pazian MF, Hanner R, et al. DNA barcoding reveals hidden diversity in the Neotropical freshwater fish Piabina argentea (Characiformes: Characidae) from the Upper Paraná Basin of Brazil. Mitochondrial DNA 2011;22(Suppl 1):87–96; doi: 10.3109/19401736.2011.588213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bingpeng X, Heshan L, Zhilan Z, et al. DNA barcoding for identification of fish species in the Taiwan strait. PLoS One 2018;13(6):e0198109; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Allen DJJ, Smith KGG, Darwall WRT. The Status and Distribution of Freshwater Biodiversity in Indo-Burma. IUCN: Cambridge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Barlow J, França F, Gardner TA, et al. The future of hyperdiverse tropical ecosystems. Nature 2018;559(7715):517–526; doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0301-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Azevedo-Santos VM, Frederico RG, Fagundes CK, et al. Protected areas: A focus on Brazilian freshwater biodiversity. Divers Distrib 2019;25(3):442–448; doi: 10.1111/ddi.12871 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Garcia TD, Strictar L, Muniz CM, et al. Our everyday pollution: Are rural streams really more conserved than urban streams? Aquat Sci 2021;83(3):47; doi: 10.1007/s00027-021-00798-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. IUCN Standards and Petitions Committee. Guidelines for Using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria. Version 15.1. Standards and Petitions Committee: Cambridge; 2022. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.