Abstract

Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (t-MN) account for approximately 10-15% of all myeloid neoplasms and are associated with poor prognosis. Genomic characterization of t-MN to date has been limited in comparison to the considerable sequencing efforts performed for de novo myeloid neoplasms. Until recently, targeted deep sequencing (TDS) or whole exome sequencing (WES) have been the primary technologies utilized and thus limited the ability to explore the landscape of structural variants and mutational signatures. In the past decade, population-level studies have identified clonal hematopoiesis as a risk factor for the development of myeloid neoplasms. However, emerging research on clonal hematopoiesis as a risk factor for developing t-MN is evolving, and much is unknown about the progression of CH to t-MN. In this work, we will review the current knowledge of the genomic landscape of t-MN, discuss background knowledge of clonal hematopoiesis gained from studies of de novo myeloid neoplasms, and examine the recent literature studying the role of therapeutic selection of CH and its evolution under the effects of antineoplastic therapy. Finally, we will discuss the potential implications on current clinical practice and the areas of focus needed for future research into therapy-selected clonal hematopoiesis in myeloid neoplasms.

Keywords: clonal hematopoiesis, therapy-related, myeloid neoplasm, therapy selected, acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Advances in anti-neoplastic therapy have led to more prolonged cancer survival overall. Still, an increased risk of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (t-MN) remains, leading to an increased focus on understanding the genetic and environmental contributors to t-MN. t-MN are a well-recognized and heterogeneous group of clonal disorders occurring after treatment with anti-neoplastic therapy and have been demonstrated to clinically manifest along the spectrum of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), or myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDS/MPN) with characteristic clinical features [1-3]. t-MN have been shown to develop 3-8 years following conventional chemotherapeutics and often carry a worse prognosis than the primary malignancy that preceded them [4]. Recently, in the treatment of cancers like hematological malignancies, the overall 10- and 20-year survival rates have increased substantially [5], arising from the development of new therapeutic options [6, 7]. The improvements in treating these primary malignancies more broadly have led to the estimation that there will be 18 million cancer survivors in 2022 in the United States alone [8, 9]. As patients live longer, the risk for t-MN is projected to increase [7, 10-13]. t-MN currently comprise 10-20% of all malignant myeloid diseases [8, 14]. The prognosis of t-MN is significantly worse compared to de novo disease, with a median survival of 8 months after diagnosis and 5-year survival rates at less than 10%, further highlighting the need for enhanced focus on determining the underlyjng mechanisms and individual risk for t-MN development [4, 15-17]

Clonal hematopoiesis (CH) has been identified as a precursor to myeloid malignancies [18-22], and it has been demonstrated that t-MN is more likely to manifest in patients with antecedent clonal hematopoiesis [17, 18, 23-25]. CH is the expansion of a single population of blood cells with an advantageous somatic mutation(s) without readily identifiable clinical manifestation [26, 27]. Across all cancer patients, CH has been observed in ~25% of cancer patients, with mutations in leukemia-specific driver genes being present in 5% of these [28, 29]. Additionally, it is essential to note that the prevalence of CH varies widely after different modalities of treatment, and characterizations of the relationships between therapeutics and the development of t-MN will be discussed further during the discussion of t-MN related genomics. CH is a heterogeneous condition with different mutations conferring different growth dynamics in the face of selective pressures and may evolve from an asymptomatic state into an aggressive malignancy [3, 21, 24-26]. Unfortunately, some of these clonal populations are associated with several health issues, not limited to t-MN [4, 16, 18, 30, 31]. Many investigators have thus directed their attention toward understanding the relationship of CH with cancer therapy and whether therapies induce clonal hematopoiesis or solely provide selective pressure for fit clones. This question remains a topic of active investigation.

t-MN can arise from a broad spectrum of background treatments, including cytotoxic chemotherapy, ionizing radiation, immunosuppressive therapy, or after prolonged exposure to an environmental carcinogen. Historically, individual therapies have been associated with unique genomic abnormalities. Alkylating agents have been associated with deletions on 5q and 7q, which have been observed in 76% of all t-MN cases in patients with an abnormal karyotype [16, 32]. Foundational genetic karyotyping work described that 5-20% of patients with therapy-related AML exhibited genetic rearrangements in the form of translocations around bands 11q23 and 21q22 [33-35], which are associated with topoisomerase inhibitor therapy. However, given the genomic complexity and idiosyncratic mutational burden that distinct chemotherapies may introduce, comprehensive analyses of the breadth and resolution of copy number abnormalities and structural variation have been limited by studies focusing primarily on whole exome sequencing or targeted sequencing data [36-38]. In this review, we will further discuss the genetics of t-MN, the role of clonal hematopoiesis on their development, and describe the findings resulting from whole genome sequencing, which aids in characterizing the interaction between intrinsic and extrinsic factors in the development of t-MN.

A study conducted by Takahashi et al. discovered an increased risk for those with clonal hematopoiesis to develop into t-MN, evidenced, in part, by the presence of CH within peripheral blood samples in 74% of t-MN patients prior to primary cancer treatment, and the observation that the incidence of t-MN was four times higher in patients with pre-existing clonal hematopoiesis compared to those without it [3]. An increased risk of t-MN development due to CH has been corroborated in several other studies [23, 39-41], demonstrating that CH is a critical element in the development of t-MN. It can also be seen, through investigations by Ok et al., that the genetic alterations underlying t-MN are distinct when compared to de novo myeloid malignancies [42]. The main question has been whether chemotherapy may introduce driver events that lead to t-MN or if it merely acts as a selection bottleneck for CH with advantageous mutations. Furthermore, chemotherapy exposure can select and eventually increase the genomic complexity of CH clones, potentially leading to the perpetuation of chemotherapy-resistant cell populations and a higher subsequent risk of developing t-MN following cancer-directed therapy [39, 43, 44]. Before this is addressed, it is crucial to explore the fundamental characteristics of CH in order to provide additional context to its relevance in discussions on the development of t-MN.

Genomics of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms

To date, characterization of the genomic contributors to the development of t-MN has primarily included TDS and WES. Several characteristic genetic abnormalities have been identified in the nearly 90% of patients with t-MN [45]. In this section, we will discuss the prior literature describing the genomic landscape of t-MN.

Dating back to the use of karyotyping to characterize gross chromosomal aneuploidies, deletions within chromosomes 5 and 7 have been observed as recurrent events in t-MN. In a study conducted by Shih et al., it was observed that within a cohort of 12 patients with TP53 mutations, 83% of patients had either monosomy 5 or deletions within chromosome 5, with half also showing a concurrent loss of regions of chromosome 7 [45]. Historically, alkylating agents are associated with an increase in chromosome 5 or 7 aberrations in patients presenting with t-MN [46-49]. It has been hypothesized that the G-C-rich regions of these chromosomes are targeted explicitly for methylation of O6 guanines, which results in DNA breaks and subsequent deletions or truncations [50]. Consequently, a loss of part, or all, of Chromosomes 5 or 7 has been postulated as a potential driver of t-MN pathogenesis [46]. However, these observations have been mainly based on cytogenetic technologies that miss the breadth and depth of chemotherapy-induced mutational events.

Other gene-treatment interactions have been identified in t-MN with numerous studies linking topoisomerase II (TOP2) inhibitors to fusions and translocations of 11q23, the MLL (KMT2A) locus [51-53]. By blocking the ligation step of DNA replication, therapeutics targeting TOP2 induce single and double-strand breakages and cell death [54, 55]; however, cells that repair these breakages might survive and, during repair, accumulate translocations. If these translocations occur within the MLL gene, a critical regulator of HOX gene expression [56-58], they confer an increased risk of developing a secondary malignancy [53, 59-61]. In support of this, a study by Cho et al., which aimed at characterizing the genetic origins of t-MN, found that 11q23 cytogenic abnormalities were the most observed genetic aberration among 14 patients with cytogenic abnormalities [62].

Several hypotheses have been posited that provide a mechanism by which mutations resulting from TOP2 inhibitors could directly lead to the development of t-MN. During mutational events within the MLL gene, it has been postulated that fusion events may occur, which are one of the most prominent drivers of leukemia [46, 63]. From this, only fusion events that conferred a selective advantage as an oncogene would be carried on, which has been demonstrated to lead to leukemias [54, 64]. Explanation or reasoning for the enrichment of MLL rearrangements with TOP2 inhibition is unknown thus far, as the mechanism by which MLL fusion contributes to leukemias as a driver event has yet to be characterized. While studies into TOP2 inhibitor-induced translocations and genetic aberrations provided some insight into a potential mechanism for the development of t-MN, it also paved the way for further investigations into other critical genetic regions postulated to have a role in t-MN development as well.

Apart from aneuploidies and structural variations, some single nucleotide variants in driver genes are enriched in t-MN. TP53 mutations have been observed to be present with significantly higher frequency in t-MN than in de novo myeloid neoplasms and are hypothesized to be critically important in disease pathogenesis [42, 45, 65]. In the previously mentioned study by Shih et al., TP53 mutations were the most common genetic anomaly, occurring in 21% of 38 patients presenting with t-MN [45]. In another, conducted by Ok et al., TP53 mutations were observed at a rate of 35.7% within t-MDS and 33.3% within t-AML. More notably, these were significantly increased within these patients when compared with de novo disease, with a 17.7% increase observed within MDS and a 12.8% increase within AML [42]. Additionally, increases in the frequency of TP53 mutations have been observed consistently within t-MN at higher frequencies when compared to de novo malignancies [25, 38, 65, 66]. Furthermore, recent evidence has suggested that TP53 is an integral component in the development of t-MN [67].

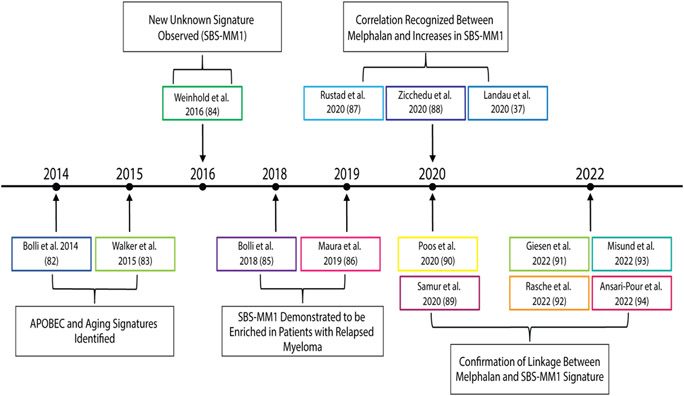

While findings from previous sequencing efforts are significant and have provided a foundation for the genomic landscape of t-MN, there have been some limitations. For instance, while de novo AML can more easily be characterized by targeted deep sequencing and conventional cytogenetics due to their relative genomic simplicity, these techniques are limited in their ability to identify the extent of genomic complexity in t-MN [19, 68]. Additionally, many endogenous and exogenous mutational processes leave evidence of their activity across the genomes of exposed cells, known as mutational signatures [69, 70]. Certain chemotherapies cause distinct DNA damage in preferred base sequence contexts that can be linked to a discrete period of clinical exposure [71]. For example, platinum-based drugs are associated with the single base substitution signatures SBS31 and SBS35 [72-74], and melphalan is associated with SBS-MM1 [37, 75, 76]. Figure 1 provides a timeline that chronicles the discovery of the melphalan SBS-MM1 signature. Others, such as 5-fluorouracil, ganciclovir (SBSA), temozolomide (SBS11), and ionizing radiation (SBS2 and SBS13), have all similarly been linked to several characteristic mutational signatures [77-80]. Therefore, the measurement of mutational signatures serves as unique markers of specific chemotherapy and can assist in characterizing the evolution of t-MN following cancer therapy. WGS has thus emerged as an essential tool to fully understand the relationship between t-MN and their preceding cancer therapies [81].

Figure 1. Timeline of investigations into the development of the SBS-MM1, a predominant signature associated with t-MN development: 2014-present.

A temporal depiction of the timeline from the first description of APOBEC and aging signature identified in 2014 through the first new unknown signature, later termed SBS-MM1, observed in 2016 and the explosion of literature in recent years demonstrating the correlation between SBS-MM1 and melphalan exposure. Abbreviations: APOBEC = apolipoprotein B editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide; SBS = single base substitutions. [37, 82-94]

Prior studies of the genomic landscape of t-MN have been compiled in Table 1, which divides prominent studies into relevant categories for future characterizations of t-MN. Table 1 also includes the background conditions of patients that develop t-MN, as secondary leukemias resulting from the treatment of antecedent hematologic malignancies, including myeloid neoplasms have been well documented [95-97]. Of these, a landmark study published by Wong and colleagues included a WGS analysis of 22 cases of t-MN [65]. Here, it was demonstrated that t-MN had a similar mutational burden to de novo AML. However, not all cytotoxic chemotherapies cause measurable mutagenic activity, and notably, these samples came from patients with a low incidence of treatment with agents that have known and measurable mutagenic profile (i.e., platinum, melphalan, temozolomide). In fact, Pich et al. further analyzed these genomes in conjunction with additional samples. They showed, adjusting for treatment, that the t-MN arising from individuals exposed to platinum chemotherapies did indeed have a higher mutational burden than t-MN without such exposure [38]. Importantly, it was demonstrated that positively selected genes (i.e., driver genes) were not likely to have been directly introduced by platinum therapy and seemed to predate the exposure. Similar findings related to temozolomide were seen in a pediatric cohort sequenced by Bertrums et al. [98].

Table 1.

Compiled table of various sequencing efforts to characterize t-MN

| STUDY | YEAR | TOTAL # OF PATIENTS |

BACKGROUND CONDITION (# WHEN SPECIFIED) |

METHOD PERFORMED |

CITATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLEVEN ET AL. | 2015 | 95 | MDS (60); CML (3); AML (32) | TDS | [99] |

| VOSO ET AL. | 2015 | 37 | HL (7); nHL (12); Breast (13); Combination of Breast and other (5) | TDS | [100] |

| WONG ET AL. | 2015 | 22 | AML; MDS | TDS; WGS | [65] |

| TAKAHASHI ET AL. | 2017 | 112 | Primary Lymphoma | TDS; MBS | [3] |

| GILLIS ET AL. | 2017 | 13 | Solid Tumor; Lymphoma; MM | TDS; WES | [101] |

| NISHIYAMA ET AL. | 2018 | 13 | MDS (9); AML (2); CMML (2) | TDS | [102] |

| BERGER ET AL. | 2018 | 18 | MDS | TDS; WES | [103] |

| SCHWARTZ ET AL. | 2019 | 62 | Hematologic; Bone/Soft Tissue; Brain | WES; RNA-Seq; WGS | [104] |

| SINGHAL ET AL. | 2019 | 129 | Hematologic; Breast; Prostate | TDS | [105] |

| KUZMANOVIC ET AL. | 2020 | 266 | Breast; Prostate; Lymphoma | TDS | [106] |

| SCHWARTZ ET AL. | 2021 | 84 | N/S | WES; RNA-Seq; WGS | [107] |

| COORENS ET AL. | 2021 | 20 | Solid Tumor | TDS; WGS | [108] |

| VOSO ET AL. | 2021 | 15 | CLL | TDS | [110] |

| LIU ET AL. | 2021 | 196 | MDS (108); AML (88) | TDS | [109] |

| PATEL ET AL. | 2021 | 109 | Various (N/S) | TDS | [111] |

| BERTRUMS ET AL. | 2022 | 24 | ALL (5) | TDS; WGS | [98] |

| CLAERHOUT ET AL. | 2022 | 64 | Breast, AML, MDS | TDS | [112] |

| DIAMOND ET AL. | 2022 | 40 | Hematologic Malignancies; Solid tumors | TDS; WGS | [81] |

| SHAH ET AL. | 2022 | 342 | N/S | TDS | [113] |

Abbreviations: WES = Whole Exome Sequencing, TDS = Targeted Deep Sequencing, MBS = Molecular Barcode Sequencing, RNA-Seq = RNA Sequencing, WGS = Whole Genome Sequencing, ALL = Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia, AML = Acute Myeloid Leukemia, MDS = Myelodysplastic Syndrome, HL = Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, nHL = Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, CMML = Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia,

Therapeutic Selection Pressures on Clonal Hematopoiesis

Recently, the mechanisms, characteristics, and frequency of somatic mutations and the tendency of these to accumulate gradually within the genome have been well-characterized [114-116]. Additionally, strong correlations have been established between mutations and aging [114], with data suggesting that nearly half of the somatic mutations are acquired during the aging process [117, 118]. While somatic mutations, especially within the context of a lifespan, are prevalent and mostly harmless [119], their effects can vary widely based on their location within the genome and the specific gene they impact [115]. To expand upon this idea, somatic mutations occurring in critical regulatory regions of the genome have been observed to possess the capacity to perpetuate into larger populations due to selective pressures inducing their proliferation. This, in essence, describes the mechanism from which clonal hematopoiesis is derived. In greater detail, CH has been shown to occur with mutations in genes, such as DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1, or the previously discussed TP53 genes [120], and/or with mosaic chromosomal alterations. These alterations lead to the expansion of the clone into a significantly larger percentage of the population due to an acquired competitive advantage [1, 121, 122]. Moreover, the combination of mutations and mosaic chromosomal alterations (clonal populations with gene mutations and copy number variants) was associated with the highest risk of progression to leukemia compared to either alone [123].

Antecedent clonal hematopoiesis has been repeatedly demonstrated as a risk factor for the development of t-MN [17, 18, 23-25]. The association has fueled multiple investigations into specific gene-treatment interactions. A quintessential study examining the evolution of CH under cancer therapy was the aforementioned study performed by Wong and colleagues. The investigators identified that many TP53 mutations that were clonally present in t-MN genomes could be detected at low frequency (variant allele frequency [VAF] 0.003-0.7%) in prior samples predating the exposure to therapy [65], suggesting that they had expanded under the selective pressures of chemotherapy. A Tp53 heterozygous null mouse model further demonstrated positive selection for Tp53 aberrant hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) after chemotherapeutic treatment [65]. These results, among others, led to the acceptance of the model of t-MN being a result of therapeutic selection pressure on clones with mutations conferring a survival advantage [46, 102].

Since Wong and colleagues demonstrated that TP53 mutations predated chemotherapy exposure, further large-scale efforts have been made to characterize the selective forces and gene-therapy relationships between CH and anti-cancer therapies [81]. In a targeted sequencing study of 8,810 cancer patients undergoing various therapies, Bolton and colleagues elaborated on variants preferentially selected by specific treatments using a VAF cutoff of 2%. Following therapy, there was a general increase in frequencies of CH with DNA-damage response mutations (TP53, CHEK2, and PPM1D), providing evidence of their advantage under selective pressure. Specifically, platinum and TOP2 therapies have been demonstrated to be most strongly correlated with the development of CH with putative driver genes, with increased mutations occurring in critical TP53, CHEK2, and PPM1D genes. Out of 35 patients in this cohort who went on to develop t-MN and had paired CH and t-MN samples, more than half had TP53 mutations, and >70% of those mutations were present at the time of CH testing. Interestingly, Bolton and colleagues challenged the notion that selection was the only effect of chemotherapy on CH by demonstrating an increase in additional somatic events, including aneuploidies or mutations in familiar leukemic drivers, including NRAS, KRAS, and FLT3 in sequential samples and resultant t-MN. This concept has tremendous importance in understanding the multiple routes CH may take toward expansion into malignancy [25].

Mutations in DNA damage response genes have since been interrogated for evolution under selective pressure. In sequencing data of peripheral blood samples with t-MN, PPM1D variants have appeared at an increased frequency [29, 40]. In a considerable DNA sequencing effort conducted by Hsu et al., PPM1D mutations were observed in 20% of 156 t-MDS patients, with only TP53 mutations being more prevalent (VAF cutoff of 0.4) [124]. PPM1D has been identified as having a vital role in regulating p53, demonstrating that mutations within this region would have similar effects to TP53 mutations and can predispose one to the development of t-MN [125]. Recently, Hsu et al. investigated the increased rates of PPM1D mutations within t-MN patients [124]. A strong relationship was confirmed between platinum chemotherapeutics [126] and the proliferation and expansion of PPM1D mutations within the genome.

Immunomodulatory agents have also emerged as essential arbiters of selective pressure on myeloid cells. In a recent study by Sperling et al., the role of lenalidomide treatment in selecting somatic TP53 mutations was analyzed within a cohort of 416 patients with multiple myeloma (MM), demonstrated through TP53 DNA sequencing efforts [127]. Lenalidomide specifically degrades CK1α [128], which has been demonstrated to activate p53 and lead to subsequent apoptosis [129]. Due to this, Sperling et al. investigated whether mutated TP53 cells would inherit the ability to bypass these apoptotic mechanisms and gain a selective advantage under lenalidomide treatment. Through mouse models mimicking patient cohorts with TP53 mutations, it was seen that the increased potency of lenalidomide induced an increase in apoptosis of wild-type TP53 cells compared to the mutated TP53 cells [127]. However, the study must be interpreted within the context of the concomitant effects of high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplant (HDM/ASCT), a ubiquitous concurrent therapy in multiple myeloma. For example, in the recent DETERMINATION study of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without HDM/ASCT, 2.7% of patients in the transplant arm developed t-MN compared to 0% with the lenalidomide combination only [130]. This suggests that further mutation from mutagenic chemotherapy and/or chemotherapy-induced alteration of the immune microenvironment is a critical factor in t-MN development.

It has become clear that even as cancer therapies shift away from cytotoxics and towards immunotherapeutics, t-MN has remained an ever-present specter. There are reports of an increased incidence of t-MN following treatment with CAR-T cellular therapy [131-133]. Recent studies have explored the relationship between CAR-T therapy and relapse, which has revealed striking correlations between induction of treatment and subsequent t-MN development [134, 135]. These examples of immune modulation/depletion leading to downstream t-MN reveal the delicate interplay between CH and immune checks. Exogenous forces – cytotoxic or otherwise – may favor the expansion of t-MN from precursors populations with proliferative or survival advantages. It has been shown that, following profound damage to the hematopoietic compartment, as in ASCT, unique clonal dynamics shape reconstitution with evidence that remarkably few ancestors repopulate the marrow [136-139]. In analyses of the unintended effects of chemotherapy, the immunosuppressive effects of various chemotherapies are well characterized and corroborated [140-142]. Additionally, inflammation responses are also observed within studies on the consequences of chemotherapies, which can affect the efficacy of the treatment, decrease immune system capabilities, and ultimately lead to worsened prognoses, particularly in hematological malignancies in which immune response plays a critical role [143-145]. Furthermore, recent investigations have indicated that novel therapies such as peptide receptor radionucleotide therapy and poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor therapy have recently been associated with t-MN development [146, 147].

Disparate Routes to t-MN Progression: Selection vs. Acquisition

Despite the plethora of evidence for the selective effects of chemotherapy on CH, some chemotherapies do indeed cause an increase in the mutational burden on resultant t-MN. Though it has been summarized here that single nucleotide mutations in driver genes exist in CH prior to the administration of chemotherapy, Diamond et al. sought to answer whether complex driver events might be introduced by mutagenic therapy. The authors included patients that had undergone ASCT as melphalan is delivered in an abbreviated time window and because the therapy is myeloablative, supporting that only the most advantageous CH mutations should confer the ability to survive exposure.

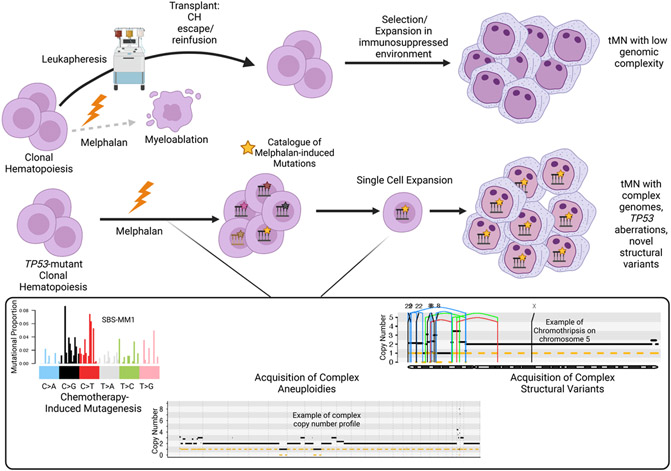

In line with prior evidence [38], all patients with previous platinum exposure had a resultant platinum-associated mutational signature within the t-MN genome. However, only a minority of patients exposed to high-dose melphalan had a corresponding SBS-MM1 melphalan-associated mutational signature [76, 148]. Through multiple lines of evidence, including a demonstration of CH in pre-chemotherapy apheresis products, the authors proposed that this differential presence of melphalan-induced mutagenesis was due to the ability of CH to escape direct exposure to myeloablative melphalan via the leukapheresis procedure. The reinfusion model corroborates the importance of the selective forces of chemotherapy: direct exposure to an exogenous agent is not needed to provoke t-MN progression, but cytotoxic effects on the immune system can create a background for CH to dominate, which is demonstrated in Figure 2. Conversely, t-MN that had evidence of chemotherapy-induced mutagenesis (i.e., SBS-MM1) did indeed have higher mutational burdens, increased incidence of complex cytogenetics, chromosomal aneuploidies, and complex structural variants with novel and recurrent drivers (i.e., SMARCA4). Using novel chemotherapy barcoding approaches, significant chromosomal gains and structural variants were seen to have been acquired after chemotherapy exposure and late in tumor evolution. This finding indicates that while cytotoxic therapy does indeed provide a selective force on prior CH, it can also lead to the acquisition of driver events.

Figure 2. Trajectories for Expansion and Transformation of Clonal Hematopoiesis Following High-Dose Melphalan and Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation.

CH may escape exposure to melphalan via leukapheresis and be autologously reinfused into an immunosuppressed recipient. The resultant t-MN bears a genomic profile similar to de novo AML and t-MN exposed to less/non-mutagenic therapies. Alternatively, fit CH clones (i.e., TP53-mutated) may survive exposure and accrue complex genomic drivers. Inset left: Single nucleotide variants will be accrued in a specific and predictable context (i.e., the mutational signature SBS-MM1). Inset center: example of a complex t-MN genome with multiple aneuploidies across each chromosome separated by vertical hatched lines. The horizontal solid black line represents the total copy number, and the horizontal hatched line represents copy number. Inset right: Example of a chromothripsis event on chromosome 5 in t-MN. The vertical lines represent structural variants breakpoints: blue = inversion, green = tandem duplication; red = deletion; black = translocation.

In addition to findings by Diamond and colleagues, research conducted by Sridharan et al., in which MM patients’ progenitor and stem cells were collected prior to autologous transplant, has uncovered that TP53 or RUNX1 mutations were present in HSCs prior to the onset t-MN. It was observed that TP53 mutations were harbored at a high rate in HSCs and ultimately became the dominant cell population within t-MN developed in these patients years later. From this, Sridharan and colleagues concluded that HSCs could act as reservoirs for leukemia-initiating cells, and provides further evidence favoring an alternate route for t-MN expansion that is largely unrelated to chemotherapeutic selection [149].

Summary and future implications

From the evidence presented within this review, it is clear that much is left to uncover regarding the origins of clonal hematopoiesis and its role in developing therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. Technological advances, like WGS, provide the opportunity to gain crucial insight into these questions and uncover the mechanisms by which these phenomena occur in order to shape future treatment plans and improve the otherwise dire prognosis associated with t-MN. WGS technology has increased the capacity to identify complex and novel t-MN driver events and helped illuminate the selection of CH from specific chemotherapies. It is now understood that certain chemotherapies have particular interactions and relationships with specific genes, but also that CH may evolve into t-MN without direct exposure of the cells to chemotherapy through reinfusion into a patient after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant. Furthermore, it has been presented that certain chemotherapies can introduce genomic complexity and driver events, leading to the formation of the novel concept of t-MN acting as a heterogenous entity with multiple routes of CH leading to progression. These findings provide relevance to recent findings by Diamond et al. and raise questions about the role of chemotherapies on the immune microenvironment and t-MN expansion. There remains much to understand regarding the role that immunosuppression and inflammatory responses play in the development of therapy-selected CH expansion and t-MN. Additionally, the direct effect of these factors on clonal populations and the mode by which they integrate into the previously demonstrated therapy-selection hypothesis presents itself as a critical target of future research on the expansion of CH and the development of t-MN. Moving forward, it is critical to identify the particular subset of patients that demonstrate a pre-disposition or affinity towards the development of t-MN, as this information is not yet known. Additionally, it is essential to thoroughly characterize the triad of the immune system, leukemic precursors, and exogenous selective forces to understand how to tailor current and emerging therapies to patients and their specific risk for t-MN development.

Highlights.

Therapy related myeloid neoplasms (t-MN) make up 10-20% of myeloid malignancies

Clonal hematopoiesis (CH) occurs at high frequency in t-MN

Whole genome sequencing characterizes complexity of t-MN genetic alterations

Triad of CH, chemotherapy selection and immune response contributes to t-MN

Acknowledgments:

We’d like to thank the Myeloma Genomic and Taylor lab members for providing helpful feedback.

Funding:

This work was supported by funding from the Edward P. Evans Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (1K08CA230319) to Dr. Taylor.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interest: Diamond: Janssen: IDMC; Medscape: Honoraria; Sanofi: Honoraria. Landgren: Adaptive: Honoraria; Binding Site: Honoraria; BMS: Honoraria; Cellectis: Honoraria; Amgen: Honoraria; Janssen: Honoraria; Celgene: Research Funding; Janssen: Other: IDMC; Janssen: Research Funding; Takeda: Other: IDMC; Amgen: Research Funding; GSK: Honoraria. Taylor: Karyopharm: Honoraria. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References:

- [1].McNerney ME, Godley LA, Le Beau MM, Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms: when genetics and environment collide, Nature Reviews Cancer 17(9) (2017) 513–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Singh ZN, Huo D, Anastasi J, Smith SM, Karrison T, Le Beau MM, Larson RA, Vardiman JW, Therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome: morphologic subclassification may not be clinically relevant, American journal of clinical pathology 127(2) (2007) 197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Takahashi K, Wang F, Kantarjian H, Doss D, Khanna K, Thompson E, Zhao L, Patel K, Neelapu S, Gumbs C, Preleukaemic clonal haemopoiesis and risk of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms: a case-control study, The lancet oncology 18(1) (2017) 100–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kayser S, Doehner K, Krauter J, Koehne C-H, Horst HA, Held G, von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Wilhelm S, Kuendgen A, Goetze K, The impact of therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia (AML) on outcome in 2853 adult patients with newly diagnosed AML, Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 117(7) (2011) 2137–2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pulte D, Jansen L, Brenner H, Changes in long term survival after diagnosis with common hematologic malignancies in the early 21st century, Blood cancer journal 10(5) (2020) 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lübbert M, Suciu S, Hagemeijer A, Rüter B, Platzbecker U, Giagounidis A, Selleslag D, Labar B, Germing U, Salih HR, Decitabine improves progression-free survival in older high-risk MDS patients with multiple autosomal monosomies: results of a subgroup analysis of the randomized phase III study 06011 of the EORTC Leukemia Cooperative Group and German MDS Study Group, Annals of hematology 95(2) (2016) 191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, Cancer survivorship issues: life after treatment and implications for an aging population, Journal of Clinical Oncology 32(24) (2014) 2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Churpek JE, Larson RA, The evolving challenge of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, Best practice & research Clinical haematology 26(4) (2013) 309–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, Stein K, Mariotto A, Smith T, Cooper D, Gansler T, Lerro C, Fedewa S, Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012, CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 62(4) (2012) 220–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].De Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, Alfano CM, Padgett L, Kent EE, Forsythe L, Scoppa S, Hachey M, Rowland JH, Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care, Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 22(4) (2013) 561–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Howlader N, Noone A-M, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse S, Kosary C, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2010, National Cancer Institute; (2014). [Google Scholar]

- [12].De Roos AJ, Deeg HJ, Onstad L, Kopecky KJ, Bowles EJA, Yong M, Fryzek J, Davis S, Incidence of myelodysplastic syndromes within a nonprofit healthcare system in western Washington state, 2005–2006, American journal of hematology 85(10) (2010) 765–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hulegårdh E, Nilsson C, Lazarevic V, Garelius H, Antunovic P, Ranged Derolf Å, Möllgård L, Uggla B, Wennström L, Wahlin A, Characterization and prognostic features of secondary acute myeloid leukemia in a population-based setting: A report from the S wedish A cute L eukemia R egistry, American journal of hematology 90(3) (2015) 208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman JW, WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, International agency for research on cancer; Lyon: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Larson RA, Le Beau MM, Therapy-related myeloid leukaemia: a model for leukemogenesis in humans, Chemico-biological interactions 153 (2005) 187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Smith SM, Le Beau MM, Huo D, Karrison T, Sobecks RM, Anastasi J, Vardiman JW, Rowley JD, Larson RA, Clinical-cytogenetic associations in 306 patients with therapy-related myelodysplasia and myeloid leukemia: the University of Chicago series, Blood 102(1) (2003) 43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Elena C, Gallì A, Bono E, Todisco G, Malcovati L, Clonal hematopoiesis and myeloid malignancies: clonal dynamics and clinical implications, Current Opinion in Hematology 28(5) (2021) 347–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jaiswal S, Ebert BL, Clonal hematopoiesis in human aging and disease, Science 366(6465) (2019) eaan4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].C.G.A.R. Network, Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia, New England Journal of Medicine 368(22) (2013) 2059–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Malcovati L, Tauro S, Gundem G, Van Loo P, Yoon CJ, Ellis P, Wedge DC, Pellagatti A, Clinical and biological implications of driver mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes, Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 122(22) (2013) 3616–3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Nangalia J, Massie CE, Baxter EJ, Nice FL, Gundem G, Wedge DC, Avezov E, Li J, Kollmann K, Kent DG, Somatic CALR mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms with nonmutated JAK2, New England Journal of Medicine 369(25) (2013) 2391–2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Reddy A, Zhang J, Davis NS, Moffitt AB, Love CL, Waldrop A, Leppa S, Pasanen A, Meriranta L, Karjalainen-Lindsberg M-L, Genetic and functional drivers of diffuse large B cell lymphoma, Cell 171(2) (2017) 481–494. e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Steensma DP, Clinical implications of clonal hematopoiesis, Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Elsevier, 2018, pp. 1122–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Genovese G, Kähler AK, Handsaker RE, Lindberg J, Rose SA, Bakhoum SF, Chambert K, Mick E, Neale BM, Fromer M, Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence, New England Journal of Medicine 371(26) (2014) 2477–2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bolton KL, Ptashkin RN, Gao T, Braunstein L, Devlin SM, Kelly D, Patel M, Berthon A, Syed A, Yabe M, Cancer therapy shapes the fitness landscape of clonal hematopoiesis, Nature genetics 52(11) (2020) 1219–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jan M, Ebert BL, Jaiswal S, Clonal hematopoiesis, Seminars in hematology, Elsevier, 2017, pp. 43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bowman RL, Busque L, Levine RL, Clonal hematopoiesis and evolution to hematopoietic malignancies, Cell stem cell 22(2) (2018) 157–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Park SJ, Bejar R, Clonal hematopoiesis in cancer, Experimental hematology 83 (2020) 105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Coombs CC, Zehir A, Devlin SM, Kishtagari A, Syed A, Jonsson P, Hyman DM, Solit DB, Robson ME, Baselga J, Therapy-related clonal hematopoiesis in patients with non-hematologic cancers is common and associated with adverse clinical outcomes, Cell stem cell 21(3) (2017) 374–382. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Abdelhameed A, Pond GR, Mitsakakis N, Brandwein J, Chun K, Gupta V, Kamel-Reid S, Lipton JH, Minden MD, Schimmer A, Outcome of patients who develop acute leukemia or myelodysplasia as a second malignancy after solid tumors treated surgically or with strategies that include chemotherapy and/or radiation, Cancer 112(7) (2008) 1513–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Quintás-Cardama A, Daver N, Kim H, Dinardo C, Jabbour E, Kadia T, Borthakur G, Pierce S, Shan J, Cardenas-Turanzas M, A prognostic model of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome for predicting survival and transformation to acute myeloid leukemia, Clinical Lymphoma Myeloma and Leukemia 14(5) (2014) 401–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rowley JD, Golomb HM, Vardiman J, Nonrandom chromosomal abnormalities in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia in patients treated for Hodgkin disease and non-Hodgkin lymphomas, Blood 50(5) (1977) 759–770. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Super H, McCabe NR, Thirman MJ, Larson RA, Le Beau MM, Pedersen-Bjergaard J, Philip P, Diaz MO, Rowley JD, Rearrangements of the MLL gene in therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia in patients previously treated with agents targeting DNA-topoisomerase II, (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Schoch C, Kern W, Schnittger S, Hiddemann W, Haferlach T, Karyotype is an independent prognostic parameter in therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia (t-AML): an analysis of 93 patients with t-AML in comparison to 1091 patients with de novo AML, Leukemia 18(1) (2004) 120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wu S, Powers S, Zhu W, Hannun YA, Substantial contribution of extrinsic risk factors to cancer development, Nature 529(7584) (2016) 43–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Alexandrov LB, Kim J, Haradhvala NJ, Huang MN, Tian Ng AW, Wu Y, Boot A, Covington KR, Gordenin DA, Bergstrom EN, The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer, Nature 578(7793) (2020) 94–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Landau HJ, Yellapantula V, Diamond BT, Rustad EH, Maclachlan KH, Gundem G, Medina-Martinez J, Ossa JA, Levine MF, Zhou Y, Accelerated single cell seeding in relapsed multiple myeloma, Nature communications 11(1) (2020) 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Pich O, Cortes-Bullich A, Muiños F, Pratcorona M, Gonzalez-Perez A, Lopez-Bigas N, The evolution of hematopoietic cells under cancer therapy, Nature communications 12(1) (2021) 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Warren JT, Link DC, Clonal hematopoiesis and risk for hematologic malignancy, Blood 136(14) (2020) 1599–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Gibson CJ, Lindsley RC, Tchekmedyian V, Mar BG, Shi J, Jaiswal S, Bosworth A, Francisco L, He J, Bansal A, Clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes after autologous stem-cell transplantation for lymphoma, Journal of Clinical Oncology 35(14) (2017) 1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Mouhieddine TH, Sperling AS, Redd R, Park J, Leventhal M, Gibson CJ, Manier S, Nassar AH, Capelletti M, Huynh D, Clonal hematopoiesis is associated with adverse outcomes in multiple myeloma patients undergoing transplant, Nature communications 11(1) (2020) 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ok CY, Patel KP, Garcia-Manero G, Routbort MJ, Fu B, Tang G, Goswami M, Singh R, Kanagal-Shamanna R, Pierce SA, Mutational profiling of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia by next generation sequencing, a comparison with de novo diseases, Leukemia research 39(3) (2015) 348–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Corces-Zimmerman MR, Hong W-J, Weissman IL, Medeiros BC, Majeti R, Preleukemic mutations in human acute myeloid leukemia affect epigenetic regulators and persist in remission, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(7) (2014) 2548–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ding L, Ley TJ, Larson DE, Miller CA, Koboldt DC, Welch JS, Ritchey JK, Young MA, Lamprecht T, McLellan MD, Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing, Nature 481(7382) (2012) 506–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Shih AH, Chung SS, Dolezal EK, Zhang S-J, Abdel-Wahab OI, Park CY, Nimer SD, Levine RL, Klimek VM, Mutational analysis of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myelogenous leukemia, Haematologica 98(6) (2013) 908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Heuser M, Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms: does knowing the origin help to guide treatment?, Hematology 2014, the American Society of Hematology Education Program Book 2016(1) (2016) 24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].McDiarmid MA, Oliver MS, Roth TS, Rogers B, Escalante C, Chromosome 5 and 7 abnormalities in oncology personnel handling anticancer drugs, Journal of occupational and environmental medicine (2010) 1028–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Sandoval C, Pui C-H, Bowman LC, Heaton D, Hurwitz CA, Raimondi SC, Behm FG, Head DR, Secondary acute myeloid leukemia in children previously treated with alkylating agents, intercalating topoisomerase II inhibitors, and irradiation, Journal of clinical oncology 11(6) (1993) 1039–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Ji Z, Zhang L, Peng V, Ren X, McHale C, Smith M, A comparison of the cytogenetic alterations and global DNA hypomethylation induced by the benzene metabolite, hydroquinone, with those induced by melphalan and etoposide, Leukemia 24(5) (2010) 986–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mamuris Z, Prieur M, Dutrillaux B, Aurias A, The chemotherapeutic drug melphalan induces breakage of chromosomes regions rearranged in secondary leukemia, Cancer genetics and cytogenetics 37(1) (1989) 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Pedersen-Bjergaard J, Christiansen D, Desta F, Andersen M, Alternative genetic pathways and cooperating genetic abnormalities in the pathogenesis of therapy-related myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia, Leukemia 20(11) (2006) 1943–1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Pedersen-Bjergaard J, Andersen M, Andersen M, Christiansen D, Genetics of therapy-related myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia, Leukemia 22(2) (2008) 240–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Leone G, Fianchi L, Pagano L, Voso MT, Incidence and susceptibility to therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, Chemico-biological interactions 184(1–2) (2010) 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Cowell IG, Austin CA, Mechanism of generation of therapy related leukemia in response to anti-topoisomerase II agents, International journal of environmental research and public health 9(6) (2012) 2075–2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Chen W, Qiu J, Shen Y, Topoisomerase IIα, rather than IIβ, is a promising target in development of anti-cancer drugs, Drug discoveries & therapeutics 6(5) (2012) 230–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Azarova AM, Lyu YL, Lin C-P, Tsai Y-C, Lau JY-N, Wang JC, Liu LF, Roles of DNA topoisomerase II isozymes in chemotherapy and secondary malignancies, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104(26) (2007) 11014–11019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Felix CA, Secondary leukemias induced by topoisomerase-targeted drugs, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Gene Structure and Expression 1400(1-3) (1998) 233–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Pedersen-Bjergaard J, Radiotherapy-and chemotherapy-induced myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia. A review, Leukemia research 16(1) (1992) 61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Le H, Singh S, Shih SJ, Du N, Schnyder S, Loredo GA, Bien C, Michaelis L, Toor A, Diaz MO, Rearrangements of the MLL gene are influenced by DNA secondary structure, potentially mediated by topoisomerase II binding, Genes, Chromosomes and Cancer 48(9) (2009) 806–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Felix CA, Kolaris CP, Osheroff N, Topoisomerase II and the etiology of chromosomal translocations, DNA repair 5(9–10) (2006) 1093–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Armstrong SA, Staunton JE, Silverman LB, Pieters R, den Boer ML, Minden MD, Sallan SE, Lander ES, Golub TR, Korsmeyer SJ, MLL translocations specify a distinct gene expression profile that distinguishes a unique leukemia, Nature genetics 30(1) (2002) 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Cho HW, Choi YB, Yi ES, Lee JW, Sung KW, Koo HH, Yoo KH, Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms in children and adolescents, Blood research 51(4) (2016) 242–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Barabé F, Kennedy JA, Hope KJ, Dick JE, Modeling the initiation and progression of human acute leukemia in mice, Science 316(5824) (2007) 600–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Krivtsov AV, Twomey D, Feng Z, Stubbs MC, Wang Y, Faber J, Levine JE, Wang J, Hahn WC, Gilliland DG, Transformation from committed progenitor to leukaemia stem cell initiated by MLL–AF9, Nature 442(7104) (2006) 818–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Wong TN, Ramsingh G, Young AL, Miller CA, Touma W, Welch JS, Lamprecht TL, Shen D, Hundal J, Fulton RS, Role of TP53 mutations in the origin and evolution of therapy-related acute myeloid leukaemia, Nature 518(7540) (2015) 552–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Martínez-Jiménez F, Muiños F, Sentís I, Deu-Pons J, Reyes-Salazar I, Arnedo-Pac C, Mularoni L, Pich O, Bonet J, Kranas H, A compendium of mutational cancer driver genes, Nature Reviews Cancer 20(10) (2020) 555–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Hiwase D, Hahn C, Tran ENH, Chhetri R, Baranwal A, Al-Kali A, Sharplin K, Ladon D, Hollins R, Greipp P, TP53 mutation in therapy-related myeloid neoplasm defines a distinct molecular subtype, Blood (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Tyner JW, Tognon CE, Bottomly D, Wilmot B, Kurtz SE, Savage SL, Long N, Schultz AR, Traer E, Abel M, Functional genomic landscape of acute myeloid leukaemia, Nature 562(7728) (2018) 526–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV, Bignell GR, Bolli N, Borg A, Børresen-Dale A-L, Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer, Nature 500(7463) (2013) 415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Nik-Zainal S, Alexandrov LB, Wedge DC, Van Loo P, Greenman CD, Raine K, Jones D, Hinton J, Marshall J, Stebbings LA, Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers, Cell 149(5) (2012) 979–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Pich O, Muiños F, Lolkema MP, Steeghs N, Gonzalez-Perez A, Lopez-Bigas N, The mutational footprints of cancer therapies, Nature genetics 51(12) (2019) 1732–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Kucab JE, Zou X, Morganella S, Joel M, Nanda AS, Nagy E, Gomez C, Degasperi A, Harris R, Jackson SP, A compendium of mutational signatures of environmental agents, Cell 177(4) (2019) 821–836. e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Poon SL, McPherson JR, Tan P, Teh BT, Rozen SG, Mutation signatures of carcinogen exposure: genome-wide detection and new opportunities for cancer prevention, Genome medicine 6(3) (2014) 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Liu X, Fagotto F, A method to separate nuclear, cytosolic, and membrane-associated signaling molecules in cultured cells, Science signaling 4(203) (2011) pl2–pl2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Kaplanis J, Ide B, Sanghvi R, Neville M, Danecek P, Coorens T, Prigmore E, Short P, Gallone G, McRae J, Genetic and chemotherapeutic causes of germline hypermutation, bioRxiv (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Maura F, Weinhold N, Diamond B, Kazandjian D, Rasche L, Morgan G, Landgren O, The mutagenic impact of melphalan in multiple myeloma, Leukemia 35(8) (2021) 2145–2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Li B, Brady SW, Ma X, Shen S, Zhang Y, Li Y, Szlachta K, Dong L, Liu Y, Yang F, Therapy-induced mutations drive the genomic landscape of relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Blood 135(1) (2020) 41–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Geddes BA, Paramasivan P, Joffrin A, Thompson AL, Christensen K, Jorrin B, Brett P, Conway SJ, Oldroyd GE, Poole PS, Engineering transkingdom signalling in plants to control gene expression in rhizosphere bacteria, Nature communications 10(1) (2019) 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Kocakavuk E, Anderson KJ, Varn FS, Johnson KC, Amin SB, Sulman E, Lolkema MP, Barthel FP, Verhaak RG, Radiotherapy is associated with a deletion signature that contributes to poor outcomes in patients with cancer, Nature genetics 53(7) (2021) 1088–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Lõhmussaar K, Oka R, Valle-Inclan JE, Smits MH, Wardak H, Korving J, Begthel H, Proost N, van de Ven M, Kranenburg OW, Patient-derived organoids model cervical tissue dynamics and viral oncogenesis in cervical cancer, Cell Stem Cell 28(8) (2021) 1380–1396. e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Diamond B, Ziccheddu B, Maclachlan K, Taylor J, Boyle E, Ossa JA, Jahn J, Affer M, Totiger TM, Coffey D, Chemotherapy Signatures Map Evolution of Therapy-Related Myeloid Neoplasms, bioRxiv (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Bolli N, Avet-Loiseau H, Wedge DC, Van Loo P, Alexandrov LB, Martincorena I, Dawson KJ, Iorio F, Nik-Zainal S, Bignell GR, Heterogeneity of genomic evolution and mutational profiles in multiple myeloma, Nature communications 5(1) (2014) 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Walker BA, Wardell CP, Murison A, Boyle EM, Begum DB, Dahir NM, Proszek PZ, Melchor L, Pawlyn C, Kaiser MF, Johnson DC, Qiang YW, Jones JR, Cairns DA, Gregory WM, Owen RG, Cook G, Drayson MT, Jackson GH, Davies FE, Morgan GJ, APOBEC family mutational signatures are associated with poor prognosis translocations in multiple myeloma, Nat Commun 6 (2015) 6997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Weinhold N, Ashby C, Rasche L, Chavan SS, Stein C, Stephens OW, Tytarenko R, Bauer MA, Meissner T, Deshpande S, Clonal selection and double-hit events involving tumor suppressor genes underlie relapse in myeloma, Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 128(13) (2016) 1735–1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Bolli N, Maura F, Minvielle S, Gloznik D, Szalat R, Fullam A, Martincorena I, Dawson KJ, Samur MK, Zamora J, Genomic patterns of progression in smoldering multiple myeloma, Nature communications 9(1) (2018) 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Maura F, Bolli N, Angelopoulos N, Dawson KJ, Leongamornlert D, Martincorena I, Mitchell TJ, Fullam A, Gonzalez S, Szalat R, Genomic landscape and chronological reconstruction of driver events in multiple myeloma, Nature communications 10(1) (2019) 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Rustad EH, Yellapantula V, Leongamornlert D, Bolli N, Ledergor G, Nadeu F, Angelopoulos N, Dawson KJ, Mitchell TJ, Osborne RJ, Timing the initiation of multiple myeloma, Nature communications 11(1) (2020) 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Ziccheddu B, Biancon G, Bagnoli F, De Philippis C, Maura F, Rustad EH, Dugo M, Devecchi A, De Cecco L, Sensi M, Integrative analysis of the genomic and transcriptomic landscape of double-refractory multiple myeloma, Blood advances 4(5) (2020) 830–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Samur MK, Roncador M, Aktas-Samur A, Fulciniti M, Bazarbachi AH, Szalat R, Shammas MA, Sperling AS, Richardson PG, Magrangeas F, High-dose melphalan significantly increases mutational burden in multiple myeloma cells at relapse: results from a randomized study in multiple myeloma, Blood 136 (2020) 4–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Poos AM, Giesen N, Catalano C, Paramasivam N, Huebschmann D, John L, Baumann A, Hochhaus J, Mueller-Tidow C, Sauer S, Comprehensive Comparison of Early Relapse and End-Stage Relapsed Refractory Multiple Myeloma, Blood 136 (2020) 1.32430499 [Google Scholar]

- [91].Giesen N, Paramasivam N, Toprak UH, Huebschmann D, Xu J, Uhrig S, Samur M, Bähr S, Fröhlich M, Mughal SS, Comprehensive genomic analysis of refractory multiple myeloma reveals a complex mutational landscape associated with drug resistance and novel therapeutic vulnerabilities, Haematologica (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Rasche L, Schinke C, Maura F, Bauer MA, Ashby C, Deshpande S, Poos AM, Zangari M, Thanendrarajan S, Davies FE, The spatio-temporal evolution of multiple myeloma from baseline to relapse-refractory states, Nature communications 13(1) (2022) 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Misund K, Hofste op Bruinink D, Coward E, Hoogenboezem RM, Rustad EH, Sanders MA, Rye M, Sponaas A-M, van der Holt B, Zweegman S, Clonal evolution after treatment pressure in multiple myeloma: heterogenous genomic aberrations and transcriptomic convergence, Leukemia (2022) 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Ansari-Pour N, Samur M, Flynt E, Gooding S, Towfic F, Stong N, Estevez MO, Mavrommatis K, Walker B, Morgan G, Whole-genome analysis identifies novel drivers and high-risk double-hit events in relapsed/refractory myeloma, Blood (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Boddu P, Kantarjian HM, Garcia-Manero G, Ravandi F, Verstovsek S, Jabbour E, Borthakur G, Konopleva M, Bhalla KN, Daver N, Treated secondary acute myeloid leukemia: a distinct high-risk subset of AML with adverse prognosis, Blood advances 1(17) (2017) 1312–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Talati C, Goldberg AD, Przespolewski A, Chan O, Al Ali N, Kim J, Famulare C, Sallman D, Padron E, Kuykendall A, Comparison of induction strategies and responses for acute myeloid leukemia patients after resistance to hypomethylating agents for antecedent myeloid malignancy, Leukemia research 93 (2020) 106367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Short NJ, Venugopal S, Qiao W, Kadia TM, Ravandi F, Macaron W, Dinardo CD, Daver N, Konopleva M, Borthakur G, Impact of frontline treatment approach on outcomes in patients with secondary AML with prior hypomethylating agent exposure, Journal of hematology & oncology 15(1) (2022) 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Bertrums EJ, Huber AKR, de Kanter JK, Brandsma AM, van Leeuwen AJ, Verheul M, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Oka R, van Roosmalen MJ, de Groot-Kruseman HA, Elevated mutational age in blood of children treated for cancer contributes to therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, Cancer discovery (2022) candisc. 0120.2022–1-28 11: 12: 19.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Cleven AH, Nardi V, Ok CY, Goswami M, Dal Cin P, Zheng Z, Iafrate AJ, Abdul Hamid MA, Wang SA, Hasserjian RP, High p53 protein expression in therapy-related myeloid neoplasms is associated with adverse karyotype and poor outcome, Modern Pathology 28(4) (2015) 552–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Voso M, Fabiani E, Zang Z, Fianchi L, Falconi G, Padella A, Martini M, Li Zhang S, Santangelo R, Larocca L, Fanconi anemia gene variants in therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, Blood cancer journal 5(7) (2015) e323–e323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Gillis NK, Ball M, Zhang Q, Ma Z, Zhao Y, Yoder SJ, Balasis ME, Mesa TE, Sallman DA, Lancet JE, Clonal haemopoiesis and therapy-related myeloid malignancies in elderly patients: a proof-of-concept, case-control study, The lancet oncology 18(1) (2017) 112–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Nishiyama T, Ishikawa Y, Kawashima N, Akashi A, Adachi Y, Hattori H, Ushijima Y, Kiyoi H, Mutation analysis of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, Cancer Genetics 222 (2018) 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Berger G, Kroeze LI, Koorenhof-Scheele TN, de Graaf AO, Yoshida K, Ueno H, Shiraishi Y, Miyano S, van den Berg E, Schepers H, Early detection and evolution of preleukemic clones in therapy-related myeloid neoplasms following autologous SCT, Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 131(16) (2018) 1846–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Schwartz JR, Ma J, Walsh MP, Chen X, Lamprecht T, Kamens J, Newman S, Zhang J, Gruber TA, Ma X, Comprehensive genomic profiling of pediatric therapy-related myeloid neoplasms identifies Mecom dysregulation to be associated with poor outcome, Blood 134 (2019) 1394. [Google Scholar]

- [105].Singhal D, Wee LYA, Kutyna MM, Chhetri R, Geoghegan J, Schreiber AW, Feng J, Wang PP-S, Babic M, Parker WT, The mutational burden of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms is similar to primary myelodysplastic syndrome but has a distinctive distribution, Leukemia 33(12) (2019) 2842–2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Kuzmanovic T, Patel BJ, Sanikommu SR, Nagata Y, Awada H, Kerr CM, Przychodzen BP, Jha BK, Hiwase D, Singhal D, Genomics of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, Haematologica 105(3) (2020) e98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Schwartz JR, Ma J, Kamens J, Westover T, Walsh MP, Brady SW, Robert Michael J, Chen X, Montefiori L, Song G, The acquisition of molecular drivers in pediatric therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, Nature communications 12(1) (2021) 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Coorens TH, Collord G, Lu W, Mitchell E, Ijaz J, Roberts T, Oliver TR, Burke G, Gattens M, Dickens E, Clonal hematopoiesis and therapy-related myeloid neoplasms following neuroblastoma treatment, Blood 137(21) (2021) 2992–2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Voso MT, Pandzic T, Falconi G, Denčić-Fekete M, De Bellis E, Scarfo L, Ljungström V, Iskas M, Del Poeta G, Ranghetti P, Clonal haematopoiesis as a risk factor for therapy-related myeloid neoplasms in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia treated with chemo-(immuno) therapy, British journal of haematology (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Liu Y-C, Illar GM, Al Amri R, Canady BC, Rea B, Yatsenko SA, Geyer JT, Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms with different latencies: a detailed clinicopathologic analysis, Modern Pathology 35(5) (2022) 625–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Patel AA, Rojek AE, Drazer MW, Weiner H, Godley LA, Le Beau MM, Larson RA, Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms in 109 patients after radiation monotherapy, Blood advances 5(20) (2021) 4140–4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Claerhout H, Vranckx H, Lierman E, Michaux L, Boeckx N, Next generation sequencing in therapy-related myeloid neoplasms compared to de novo myeloid neoplasms, Acta Clinica Belgica 77(3) (2022) 658–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Shah MV, Mangaonkar AA, Begna KH, Alkhateeb HB, Greipp P, Nanaa A, Elliott MA, Hogan WJ, Litzow MR, McCullough K, Therapy-related clonal cytopenia as a precursor to therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, Blood cancer journal 12(7) (2022) 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Vijg J, Somatic mutations and aging: a re-evaluation, Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 447(1) (2000) 117–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Martincorena I, Campbell PJ, Somatic mutation in cancer and normal cells, Science 349(6255) (2015) 1483–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Pleasance ED, Cheetham RK, Stephens PJ, McBride DJ, Humphray SJ, Greenman CD, Varela I, Lin M-L, Ordóñez GR, Bignell GR, A comprehensive catalogue of somatic mutations from a human cancer genome, Nature 463(7278) (2010) 191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr, Kinzler KW, Cancer genome landscapes, science 339(6127) (2013) 1546–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Milholland B, Auton A, Suh Y, Vijg J, Age-related somatic mutations in the cancer genome, Oncotarget 6(28) (2015) 24627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Martincorena I, Somatic mutation and clonal expansions in human tissues, Genome Medicine 11(1) (2019) 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Buscarlet M, Provost S, Zada YF, Barhdadi A, Bourgoin V, Lépine G, Mollica L, Szuber N, Dubé M-P, Busque L, DNMT3A and TET2 dominate clonal hematopoiesis and demonstrate benign phenotypes and different genetic predispositions, Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 130(6) (2017) 753–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Evans MA, Sano S, Walsh K, Cardiovascular disease, aging, and clonal hematopoiesis, Annual review of pathology 15 (2020) 419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].King KY, Huang Y, Nakada D, Goodell MA, Environmental influences on clonal hematopoiesis, Experimental hematology 83 (2020) 66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Gao T, Ptashkin R, Bolton KL, Sirenko M, Fong C, Spitzer B, Menghrajani K, Ossa JEA, Zhou Y, Bernard E, Interplay between chromosomal alterations and gene mutations shapes the evolutionary trajectory of clonal hematopoiesis, Nature communications 12(1) (2021) 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Hsu JI, Dayaram T, Tovy A, De Braekeleer E, Jeong M, Wang F, Zhang J, Heffernan TP, Gera S, Kovacs JJ, PPM1D mutations drive clonal hematopoiesis in response to cytotoxic chemotherapy, Cell Stem Cell 23(5) (2018) 700–713. e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Deng W, Li J, Dorrah K, Jimenez-Tapia D, Arriaga B, Hao Q, Cao W, Gao Z, Vadgama J, Wu Y, The role of PPM1D in cancer and advances in studies of its inhibitors, Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 125 (2020) 109956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Zhou J, Kang Y, Chen L, Wang H, Liu J, Zeng S, Yu L, The drug-resistance mechanisms of five platinum-based antitumor agents, Frontiers in pharmacology 11 (2020) 343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Sperling AS, Guerra VA, Kennedy JA, Yan Y, Hsu JI, Wang F, Nguyen AT, Miller PG, McConkey ME, Barrios VAQ, Lenalidomide promotes the development of TP53-mutated therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, Blood (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Krönke J, Fink EC, Hollenbach PW, MacBeth KJ, Hurst SN, Udeshi ND, Chamberlain PP, Mani D, Man HW, Gandhi AK, Lenalidomide induces ubiquitination and degradation of CK1α in del (5q) MDS, Nature 523(7559) (2015) 183–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Schneider RK, Ademà V, Heckl D, Järås M, Mallo M, Lord AM, Chu LP, McConkey ME, Kramann R, Mullally A, Role of casein kinase 1A1 in the biology and targeted therapy of del (5q) MDS, Cancer cell 26(4) (2014) 509–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Richardson PG, Jacobus SJ, Weller EA, Hassoun H, Lonial S, Raje NS, Medvedova E, McCarthy PL, Libby EN, Voorhees PM, Triplet Therapy, Transplantation, and Maintenance until Progression in Myeloma, New England Journal of Medicine (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Cordeiro A, Bezerra ED, Hirayama AV, Hill JA, Wu QV, Voutsinas J, Sorror ML, Turtle CJ, Maloney DG, Bar M, Late events after treatment with CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor modified T cells, Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 26(1) (2020) 26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Schubert M-L, Schmitt M, Wang L, Ramos C, Jordan K, Müller-Tidow C, Dreger P, Side-effect management of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, Annals of oncology 32(1) (2021) 34–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Bhoj VG, Arhontoulis D, Wertheim G, Capobianchi J, Callahan CA, Ellebrecht CT, Obstfeld AE, Lacey SF, Melenhorst JJ, Nazimuddin F, Persistence of long-lived plasma cells and humoral immunity in individuals responding to CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy, Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 128(3) (2016) 360–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Saini N, Neelapu SS, CAR Treg cells: prime suspects in therapeutic resistance, Nature medicine 28(9) (2022) 1755–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Alkhateeb HB, Mohty R, Greipp P, Bansal R, Hathcock M, Rosenthal A, Murthy H, Kharfan-Dabaja M, Bisneto Villasboas JC, Bennani N, Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms following chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, Blood cancer journal 12(7) (2022) 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Parmar H, Gertz M, Anderson EI, Kumar S, Kourelis TV, Microenvironment immune reconstitution patterns correlate with outcomes after autologous transplant in multiple myeloma, Blood advances 5(7) (2021) 1797–1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Dijkgraaf EM, Heusinkveld M, Tummers B, Vogelpoel LT, Goedemans R, Jha V, Nortier JW, Welters MJ, Kroep JR, van der Burg SH, Chemotherapy Alters Monocyte Differentiation to Favor Generation of Cancer-Supporting M2 Macrophages in the Tumor MicroenvironmentEffect of Chemotherapy on Tumor Microenvironment, Cancer research 73(8) (2013) 2480–2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Biasco L, Pellin D, Scala S, Dionisio F, Basso-Ricci L, Leonardelli L, Scaramuzza S, Baricordi C, Ferrua F, Cicalese MP, In vivo tracking of human hematopoiesis reveals patterns of clonal dynamics during early and steady-state reconstitution phases, Cell stem cell 19(1) (2016) 107–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Sun J, Ramos A, Chapman B, Johnnidis JB, Le L, Ho Y-J, Klein A, Hofmann O, Camargo FD, Clonal dynamics of native haematopoiesis, Nature 514(7522) (2014) 322–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].Rasmussen L, Arvin A, Chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression, Environmental health perspectives 43 (1982) 21–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].Morrison VA, Immunosuppression associated with novel chemotherapy agents and monoclonal antibodies, Clinical infectious diseases 59(suppl_5) (2014) S360–S364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [142].Hersh EM, Whitecar JP Jr, McCredie KB, Bodey GP Sr, Freireich EJ, Chemotherapy, immunocompetence, immunosuppression and prognosis in acute leukemia, New England Journal of Medicine 285(22) (1971) 1211–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Vyas D, Laput G, Vyas AK, Chemotherapy-enhanced inflammation may lead to the failure of therapy and metastasis, OncoTargets and therapy 7 (2014) 1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].van der Most RG, Currie AJ, Robinson B, Lake RA, Decoding dangerous death: how cytotoxic chemotherapy invokes inflammation, immunity or nothing at all, Cell Death & Differentiation 15(1) (2008) 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [145].Smith AK, Conneely KN, Pace TW, Mister D, Felger JC, Kilaru V, Akel MJ, Vertino PM, Miller AH, Torres MA, Epigenetic changes associated with inflammation in breast cancer patients treated with chemotherapy, Brain, behavior, and immunity 38 (2014) 227–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [146].O'Malley DM, Oza AM, Lorusso D, Aghajanian C, Oaknin A, Dean A, Colombo N, Weberpals JI, Clamp AR, Scambia G, Clinical and molecular characteristics of ARIEL3 patients who derived exceptional benefit from rucaparib maintenance treatment for high-grade ovarian carcinoma, Gynecologic Oncology 167(3) (2022) 404–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [147].Singh A, Mencia-Trinchant N, Griffiths EA, Altahan A, Swaminathan M, Gupta M, Gravina M, Tajammal R, Faber MG, Yan L, Mutant PPM1D-and TP53-Driven hematopoiesis populates the hematopoietic compartment in response to peptide receptor radionuclide therapy, JCO Precision Oncology 6 (2022) e2100309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [148].Rustad EH, Yellapantula VD, Glodzik D, Maclachlan KH, Diamond B, Boyle EM, Ashby C, Blaney P, Gundem G, Hultcrantz M, Revealing the impact of structural variants in multiple myeloma, Blood cancer discovery 1(3) (2020) 258–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [149].Sridharan A, Schinke CD, Georgiev G, Da Silva Ferreira M, Thiruthuvanathan V, MacArthur I, Bhagat TD, Choudhary GS, Aluri S, Chen J, Stem cell mutations can be detected in myeloma patients years before onset of secondary leukemias, Blood advances 3(23) (2019) 3962–3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]