Abstract

Objectives

Increasing depressive symptoms have become an urgent public health concern worldwide. This study aims to explore the correlation between personality traits and changes in depressive symptoms before and after the COVID-19 outbreak and to examine the gender difference in this association further.

Methods

Data were obtained from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS, wave in 2018 and 2020). A total of 16,369 residents aged 18 and above were included in this study. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to examine whether personality traits were associated with changes in depressive symptoms. We also analyzed whether there was an interaction effect of gender and personality traits on depressive symptoms.

Results

Conscientiousness, extroversion, and agreeableness are negatively associated with depressive symptoms, while neuroticism and openness are positively related. Gender moderates the relationship between personality traits and depressive symptoms. Compared to men, women have demonstrated a stronger association between neuroticism (OR = 0.79; 95 % CI = 0.66, 0.94), conscientiousness (OR = 1.40; 95 % CI = 1.15, 1.69), and persistent depressive symptoms.

Limitations: Given its longitudinal study design, it is insufficient to draw a causal inference between personality traits and depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

Personality traits and their various dimensions are correlated with changes in depressive symptoms. Persistent depressive symptoms are positively related to neuroticism and negatively associated with conscientiousness. Women demonstrate a stronger association between personality traits and persistent depressive symptoms. Thus, in Chinese adults' mental health intervention and prevention programs, personality and gender-specific strategies should be considered, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Depressive symptoms, Personality traits, Gender, Chinese adults

1. Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 has further aggravated depressive symptoms in the public (Santomauro et al., 2021; Zang et al., 2022). With approximately 350 million individuals worldwide suffering from depressive symptoms, the widespread prevalence of depressive symptoms is undoubtedly a major public health issue (Wu et al., 2022). Based on Global Burden of Disease (GBD) data a study showed that the number of cases of depressive symptoms increased from 172 million to 25,8 million from 1990 to 2017 (Liu et al., 2020). To make it even more severe, the prevalence of depressive symptoms in China is blooming along with economic growth and lifestyle changes, posing a considerable challenge to development. Emerging evidence has indicated that depressive symptoms have become the leading cause of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) in China. For example, a nationally representative study among Chinese adults noted that depression and depressive symptoms jointly contribute to 14.7 % of total personal expected medical spending, with depression and depressive symptoms accounting for 6.9 % and 7.8 %, respectively, which is roughly triple the impact of obesity and overweight on health care costs reported in the previous study (Hsieh and Qin, 2018). Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to the risk factors of depressive symptoms in the Chinese population and to provide targeted recommendations for promoting mental health.

Personality traits, such as cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects, are essential in increasing the propensity for psychopathological states, such as depressive symptoms (Kocjana et al., 2021). It has been found that personality is associated with the occurrence, recurrence, severity of symptoms, and duration of depression (Fournier et al., 2017; Hayward et al., 2013). The most widely acknowledged personality theory is the Five Factor Model (neuroticism, extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness are included as the five factors) established in the 1980s (Clark and Watson, 1999; Markon et al., 2005). Numerous studies have revealed that there is a correlation between personality trait subtypes and changes in depressive symptoms, and many researchers have pointed out that neuroticism has the strongest correlation with depressive symptoms (Elliot et al., 2019; van Eeden et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2021). Specifically, people with high neuroticism are more susceptible to depressive symptoms (Meng et al., 2020; Navrady et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2019). Previous research has also exposed that personality traits such as high levels of neuroticism, low levels of extraversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness are associated with the prognosis of depressive symptoms (Shokrkon and Nicoladis, 2021). In addition, relevant studies have revealed that changes in personality traits have an impact on changes in depressive symptoms (Naragon-Gainey and Watson, 2014). However, some researchers believe that personality traits are a relatively stable structure, so the relationship between personality traits and depressive symptoms has not yet reached a unified conclusion (Panaite et al., 2020; Segerstrom, 2019).

Gender may be a moderator in the relationship between personality traits and depressive symptoms. According to previous studies, there is a higher incidence of episodic stress and emotional distress in women during daily life, and women are prone to depressive symptoms when facing negative experiences (Dalgard et al., 2006; Hyde et al., 2008). Thus, compared to men, women may have a stronger relationship between personality and depressive symptoms. Although many biological, sociological, and psychological theories have attempted to explain gender differences in depressive symptoms and their relationship to the personality (Goncalves Pacheco et al., 2019; Salk et al., 2017), the moderator role of gender in the relationship between personality and depressive symptoms remains unclear.

The research hypothesis contains the following two points: First, personality traits as well as their dimensions are related to depressive symptoms. Second, there is an interactive effect between gender and personality traits with depressive symptoms. Specifically, the association between neuroticism and depressive symptoms would be stronger in women than in men.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources and sample composition

The data are all collected from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), which is a nationally representative annual longitudinal data funded and approved by the Institute of Social Science Survey (ISSS) of Peking University (Xie and Hu, 2014). In-person interviews and computer-assisted online interviews are adapted for CFPS (Xie and Lu, 2015). Multi-stage probability proportional-to-size sampling method was used and all household members were interviewed in each family. Besides, strict quality control is carried out by experienced professional teams in project development and investigation, including data sorting and database construction to ensure data quality (Xie and Hu, 2014).

The CFPS data assigned each interviewee a unique identification number (ID number) that is consistent across years of surveys, so we constructed panel data for 2018 and 2020 for each investigator by using the ID number. The inclusion criteria of this study were: 1) individuals aged 18 and above, and 2) individuals who had completed the CFPS survey in both 2018 and 2020. The exclusion criteria were: 1) the age was under 18 in 2018, and 2) the variables of interest in this study were missing. We obtained 16,369 respondents who were fully surveyed in 2018 and 2020 as the sample for this study after screening and matching using unique identification numbers. In addition, our study has requested permission from ISSS to utilize the data.

2.2. Outcome variable: changes in depressive symptoms from 2018 to 2020

We used the changes in depressive symptoms of each respondent from 2018 to 2020 in our panel data as the outcome variable. One of the most widely used self-evaluation scales, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES—D—8) questionnaire, created by Radloff, was utilized in the 2018 and 2020 CFPS surveys to measure probable depression (Radloff, 1977). CFPS started using simplified CES—D—8 in 2018 to shorten investigation time and improve the response rate. Previous studies have illustrated that the 8-item CES-D scale has good reliability and validity in screening for depression (Briggs et al., 2018a, Briggs et al., 2018b; Cai et al., 2021). The detail of the 8-item CES-D scale is presented in Appendix table 1.

Respondents reported their depressive symptoms over the past week, with the options for each question ranging from 0 to 3 (0 = rarely, 1 = little, 2 = occasionally, and 3 = often). Negative questions were assigned a score of 0 to 3, and positive questions were assigned a score of 3 to 0. The total CES—D—8 score ranged from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. In this study, the 80th percentile (8 points) of the 8-item CES-D was used as a cutoff point to assess whether participants were at high risk for depressive symptoms. It has demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity in previous research (Briggs et al., 2018b; Bulut et al., 2021; Feeney and Kenny, 2022; Radloff, 1977). Thus, we divided the total scores of respondents into two categories based on their scores, healthy (≤8) or depressive symptoms (>8), to assess the proportion of residents with mental health issues and those who are at risk of depression. The internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach's alpha) of the whole scale in our study was 0.77, and the results were considered credible.

Then, according to the changes in depressive symptoms scores in 2018 and 2020, we divided the outcomes of all samples into four groups: a persistently healthy group without depressive symptoms (healthy group; stayed healthy in both 2018 and 2020), a group that recovered from depression (depression-recovery group; depressed in 2018 but healthy in 2020), a group with newly-onsite depression or recurrent depression (depression-onsite group; healthy in 2018 but depressed in 2020), and a group with persistent depression (persistent-depression group; depressed in 2018 and 2020). The detail of the four categories is in Appendix table 2. To increase the robustness of the results, the difference between the depressive symptoms scores in 2018 and 2020 was directly used as a continuous variable for regression analysis.

2.3. Primary independent variables: Personality traits

Personality data using the same BFI-S scale for all individuals over the age of 15 was collected in our panel data. The scale contains 15 items (each item has a score of 1–5) and is a simplified version of the personality measurement scale based on BFI-44, designed by Gerlitz et al. (Gerlitz and Schupp, 2005; Hahn et al., 2012), which has been proven to have good validity and reliability (Gerlitz and Schupp, 2005; Hahn et al., 2012). The BFI-S scale is shown in Appendix table 3. Studies have demonstrated that this scale is a scientific and credible scoring method for complete reliability and validity analysis (Qiong and Liping, 2020). The internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach's alpha) of the whole scale in this study was 0.73. According to previous studies, we divided all items into five dimensions reflecting personality characteristics (Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Openness, Neuroticism, and Agreeableness), and calculated the total score of each dimension as five main continuous independent variables.

2.4. Potential confounders

The following demographic and socioeconomic characteristics were incorporated into our study: region (West/Central/East/Northeast); residency (urban/rural); gender (female/male); age (18–30 years old/30–45 years old/>45 years old); marital status (married/unmarried); current employment status (employed/unemployed); education (primary school/middle school/high school/college degree or above); chronic diseases (yes/no); self-reported health status (poor/fair/good); self-evaluated income status (low or low-middle income/middle income/middle-high income/high income); smoking (yes/no); alcohol abuse (yes/no). These variables were included in this study because they are associated with depressive symptoms in previous studies (Adan et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2021).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Stata version 15.0 was used for data analysis. Change in depressive symptoms is the dependent variable, and personality traits in the baseline are our independent variables. We treated Socio-demographic variables in the baseline are confounding variables. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the distribution of subjects and used Cramer's V coefficient to explore whether each independent variable had a statistically significant correlation with changes in depressive symptoms. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify whether independent variables especially personality traits were associated with changes in depressive symptoms, and multiple linear regression was used for the robustness test. The interaction effect of gender on the relationship between personality traits and depressive symptoms was also examined. The statistical significance level (α) was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Sociological-demographic characteristics of the sample

The final sample consists of 16,369 residents, with the majority of participants from the East. The median age of the residents was 48 years old, and their mean age was 47.64 years old (SD = 14.9). The majority of the residents in this survey (52.35 %) came from rural areas, while the remaining 47.65 % were from urban areas. The respondents were mainly married, employed, and without chronic diseases, representing most of China's population. The self-assessed health status of most people was fair (44.47 %). Respondents with middle (49.23 %) and low-middle (18.05 %) incomes make up more than half of the sample. Most of the respondents did not smoke (69.44 %) or drink alcohol (83.52 %). In 2018, the percentages of healthy and depressed individuals were 81.25 % and 18.75 %, respectively. Compared with 2018, there were fewer mentally healthy people (79.13 %) and more depressed people (20.87 %) in 2020 (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| N (%) | Male | Female | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | 0.004 | |||

| Northeast | 2352 (14.37) | 1093 | 1259 | |

| East | 5688 (34.75) | 2894 | 2794 | |

| West | 4409 (23.95) | 1911 | 2009 | |

| Central | 3920 (26.94 | 2272 | 2137 | |

| Residency | <0.001 | |||

| Urban | 8569 (47.65) | 4184 | 4385 | |

| Rural | 7800 (52.35) | 3986 | 3814 | |

| Age | 0.039 | |||

| 18–30 | 1873 (11.44) | 923 | 950 | |

| 30–45 | 4678 (28.58) | 2269 | 2409 | |

| >45 | 9818 (59.98) | 4978 | 4840 | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 1384 (84.57) | 6821 | 7023 | |

| Unmarried | 2525 (15.43) | 1349 | 1176 | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Unemployed | 3607 (22.04) | 1230 | 2377 | |

| Employed | 1276 (77.69) | 6940 | 5822 | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| Primary school | 6295 (38.46) | 2739 | 3556 | |

| Middle school | 4986 (30.46) | 2707 | 2279 | |

| High school | 3946 (24.11) | 2150 | 1796 | |

| College degree or above | 1142 (6.98) | 574 | 568 | |

| Chronic diseases | <0.001 | |||

| No | 1364 (83.36) | 6919 | 6727 | |

| Yes | 2723 (16.64) | 1251 | 1472 | |

| Self-reported health status | <0.001 | |||

| Poor | 4320 (26.39) | 1893 | 2427 | |

| Fair | 7280 (44.47) | 3647 | 3633 | |

| Good | 4769 (29.13) | 2630 | 2139 | |

| Self-evaluated income status | 0.001 | |||

| Low | 1555 (9.5) | 708 | 847 | |

| Low-middle | 2954 (18.05) | 1444 | 1510 | |

| Middle | 8058 (49.23) | 4103 | 3955 | |

| Middle-high | 2149 (13.13) | 1107 | 1042 | |

| High | 1653 (10.1) | 808 | 845 | |

| Smoking | <0.001 | |||

| No | 11,366(69.44) | 3474 | 7892 | |

| Yes | 5003 (30.56) | 4696 | 307 | |

| Alcohol abuse | <0.001 | |||

| No | 13,671(83.52) | 5807 | 7864 | |

| Yes | 2698 (16.48) | 2363 | 335 | |

| Depression status (2018) | <0.001 | |||

| Depression | 3070 (18.75) | 1256 | 1814 | |

| Healthy | 13,299(81.25) | 6918 | 6381 | |

| Depression status (2020) | ||||

| Depression | 3417 (20.87) | 1473 | 1944 | |

| Healthy | 12,952(79.13) | 6697 | 6255 |

3.2. Binary correlations of independent variables with depressive symptoms

Table 2 displays the results of the correlation between control variables and changes in depressive symptoms. We found that gender, chronic diseases, and self-reported health status significantly correlated (P < 0.05) with changes in residents' depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Analysis results of risk factors on depression status.

| Healthy group | Depression -recovery group |

Depression- onsite group |

Persistent -depression group |

P-value | Cramer's V | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | <0.001 | 0.06 | ||||

| Northeast | 1648 | 210 | 264 | 230 | ||

| East | 4222 | 482 | 544 | 440 | ||

| West | 2784 | 496 | 609 | 520 | ||

| Central | 2739 | 371 | 489 | 321 | ||

| Township | <0.001 | 0.09 | ||||

| Urban | 6301 | 712 | 878 | 678 | ||

| Rural | 5092 | 847 | 1028 | 833 | ||

| Gender | <0.001 | 0.1 | ||||

| Male | 6035 | 662 | 878 | 595 | ||

| Female | 5358 | 897 | 1028 | 916 | ||

| Age | ||||||

| 18–30 | 1387 | 155 | 222 | 109 | <0.001 | 0.05 |

| 30–45 | 3366 | 416 | 540 | 356 | ||

| >45 | 6640 | 988 | 1144 | 1046 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 9842 | 1272 | 1555 | 1175 | <0.001 | 0.08 |

| Unmarried | 1551 | 287 | 351 | 336 | ||

| Working status | ||||||

| Unemployed | 2437 | 368 | 421 | 381 | 0.003 | 0.03 |

| Employed | 8956 | 1191 | 1485 | 1130 | ||

| Education | <0.001 | 0.09 | ||||

| Primary school | 3884 | 745 | 864 | 802 | ||

| Middle school | 3584 | 443 | 550 | 409 | ||

| High school | 3017 | 283 | 391 | 255 | ||

| College degree or above | 908 | 88 | 101 | 45 | ||

| Chronic diseases | <0.001 | 0.14 | ||||

| No | 9855 | 1238 | 1480 | 1073 | ||

| Yes | 1538 | 321 | 426 | 438 | ||

| Self-reported health status | <0.001 | 0.17 | ||||

| Bad | 2318 | 510 | 700 | 792 | ||

| General | 5296 | 662 | 805 | 517 | ||

| Good | 3779 | 387 | 401 | 202 | ||

| Self-evaluated income status | <0.001 | 0.08 | ||||

| Low | 853 | 188 | 255 | 259 | ||

| Low-middle | 1893 | 288 | 411 | 362 | ||

| Middle | 5892 | 731 | 845 | 590 | ||

| Middle-high | 1595 | 185 | 207 | 162 | ||

| High | 1160 | 167 | 188 | 138 | ||

| Smoking | <0.001 | 0.04 | ||||

| No | 7740 | 1219 | 1311 | 1096 | ||

| Yes | 3653 | 340 | 595 | 415 | ||

| Alcohol abuse | <0.001 | 0.06 | ||||

| No | 9303 | 1433 | 1606 | 1329 | ||

| Yes | 2090 | 126 | 300 | 182 | ||

| Personality traits | 11,393 | 1559 | 1906 | 1511 | ||

| Conscientiousness | <0.001 | 0.04 | ||||

| Extraversion | <0.001 | 0.05 | ||||

| Openness | 0.004 | 0.04 | ||||

| Neuroticism | <0.001 | 0.06 | ||||

| Agreeableness | <0.001 | 0.05 |

3.3. Multi-nominal logistic analysis for the relationship between personality and changes in depressive symptoms

Table 3 presents the results of the multi-nominal logistic analysis assessing the related factors for depressive status. With confounding variables controlled, every personality dimension was significantly associated with changes in depressive symptoms. Specifically, conscientiousness (OR = 0.87; 95 % CI = 0.79,0.95), extroversion (OR = 0.77; 95 % CI = 0.71,0.82), and agreeableness (OR = 0.83; 95 % CI = 0.75,0.92) were protective factors, while neuroticism (OR = 1.41; 95 % CI = 1.29,1.54) and openness (OR = 1.27; 95 % CI = 1.17,1.37) were risk factors for persistent depressive symptoms. The results were similar to the depression-recovery group and depression-onsite group. The results of the robustness test are similar to multi-nominal logistic regression (Appendix Table 1).

Table 3.

Results of multinominal logistic regression of risk factors for depressive status.

| Depression-recovery group |

Depression-onsite group |

Persistent-depression group |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| ORa (95 % CI) | ORa (95 % CI) | ORa (95 % CI) | |

| Region (Ref: East) | |||

| Northeast | 1.09 (0.91,1.31) | 1.24 (1.05,1.45)⁎⁎ | 1.22 (1.02,1.46)⁎ |

| Central | 1.15 (0.99,1.33) | 1.36 (1.18,1.55)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.07 (0.91,1.25) |

| West | 1.37 (1.19,1.58)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.53 (1.34,1.74)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.53 (1.32,1.77)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Residency (Ref: Urban) | |||

| Rural | 1.22 (1.08,1.37)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.21 (1.08,1.34)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.17 (1.03,1.33)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Gender (Ref: Male) | |||

| Female | 1.48 (1.28,1.71)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.33(1.16,1.51)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.86 (1.58,2.18)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Age (Ref: 18–30) | |||

| 30–45 | 1.11 (0.91,1.36) | 0.91 (0.77,1.09) | 1.27(1.01,1.60)⁎ |

| >45 | 0.93 (0.76,1.14) | 0.81 (0.68,0.97) ⁎ | 1.14 (0.91,1.43) |

| Marital status (Ref: Married) | |||

| Unmarried | 1.91 (1.63,2.25)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.46 (1.25,1.70)⁎⁎⁎ | 2.42 (2.06,2.84)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Work conditions (Ref: Unemployed) | |||

| Employed | 1.09 (0.95,1.25) | 1.06 (0.93,1.21) | 1.27 (1.10,1.47)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Education (Ref: primary) | |||

| Middle school | 0.76 (0.66,0.88)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.74 (0.65,0.83)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.71(0.62,0.82)⁎⁎⁎ |

| High school | 0.58 (0.49,0.69)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.62 (0.53,0.72)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.54 (0.45,0.64)⁎⁎⁎ |

| College degree or above | 0.63 (0.48,0.83)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.53 (0.41,0.69)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.32 (0.22,0.46)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Chronic diseases (Ref: No) | |||

| Yes | 1.43 (1.25,1.65)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.15 (1.00,1.33)⁎ | 1.63 (1.42,1.87)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Self-reported health status (Ref: Good) | |||

| Poor | 3.18 (2.68,3.77)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.79 (1.55,2.07)⁎⁎⁎ | 5.24 (4.34,6.32)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Fair | 1.79 (1.53,2.10)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.34 (1.18,1.52)⁎⁎⁎ | 2.21 (1.84,2.66)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Self-evaluated income status (Ref: Low) | |||

| Low-middle | 0.74 (0.60,0.92)⁎⁎ | 0.77 (0.64,0.92)⁎⁎ | 0.74 (0.61,0.89)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Middle | 0.63 (0.52,0.76)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.54 (0.46,0.63)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.41 (0.34,0.49)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Middle-high | 0.57 (0.45,0.71)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.47 (0.38,0.58)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.40 (0.32,0.50)⁎⁎⁎ |

| High | 0.64 (0.50,0.81)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.52 (0.42,0.65)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.38 (0.30,0.49)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Smoking (Ref: No) | |||

| Yes | 1.07 (0.91,1.25) | 1.12 (0.97,1.28) | 1.26 (1.06,1.49)⁎⁎ |

| Alcohol abuse (Ref: No) | |||

| Yes | 0.91 (0.76,1.09) | 0.94 (0.80,1.09) | 0.84 (0.70,1.02) |

| Personality Traits | |||

| Conscientiousness | 0.86 (0.78,0.95)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.91 (0.83,0.99)⁎ | 0.87 (0.79,0.95)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Extraversion | 0.90 (0.84,0.97)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.90 (0.85,0.96)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.77 (0.71,0.82)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Openness | 1.13(1.05,1.22)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.11 (1.04,1.19)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.27 (1.17,1.37)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Neuroticism | 1.38 (1.26,1.50)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.27 (1.18,1.37)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.41 (1.29,1.54)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Agreeableness | 0.83 (0.75,0.92)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.85 (0.77,0.92)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.83 (0.75,0.92)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Con. | 0.08 (0.05,0.15)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.21 (0.13,0.35)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.05 (0.03,0.09)⁎⁎⁎ |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Compared to the healthy group (N = 11,393).

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

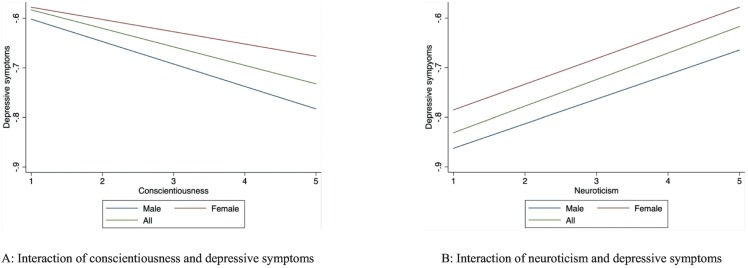

3.4. The interactive effects of gender and personality traits on depressive symptoms

Table 4 and Fig. 1 show the regression results after introducing the interaction of gender and personality on depressive symptoms. In the persistent depressive symptoms group, significant interaction effects were observed for gender*neuroticism (OR = 0.79; 95 % CI = 0.66, 0.94) and gender*conscientiousness (OR = 1.40; 95 % CI = 1.15, 1.69). Compared with men, women demonstrate a stronger association between neuroticism, conscientiousness, and persistent depressive symptoms.

Table 4.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis results with interactions.

| Depression-recovery group |

Depression-onsite group |

Persistent-depression group |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| ORa (95 % CI) | ORa (95 % CI) | ORa (95 % CI) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1.52 (1.36,1.70)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.31 (1.19,1.45)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.88 (1.67,2.12)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Personality traits | |||

| Conscientiousness | 0.88 (0.75,1.02) | 0.81 (0.71,0.95)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.67 (0.58,0.78)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Extraversion | 0.89 (0.80,0.99)⁎ | 0.90 (0.82,0.96)⁎ | 0.73 (0.66,0.82)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Openness | 1.05 (0.93,1.17) | 1.11 (1.00,1.31)⁎ | 1.17 (1.03,1.33)⁎ |

| Neuroticism | 1.43 (1.26,1.63)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.36 (1.22,1.46)⁎⁎⁎ | 1.78 (1.55,2.04)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Agreeableness | 0.76 (0.65,0.88)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.82 (0.72,0.95)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.82 (0.71,0.96)⁎⁎ |

| Gender*Conscientiousness | 0.92 (0.76,1.12) | 1.17 (0.98,1.39) | 1.40 (1.15,1.69)⁎⁎⁎ |

| Gender*Extraversion | 1.01 (0.87,1.16) | 1.01 (0.89,1.15) | 1.08 (0.93,1.24) |

| Gender*Openness | 1.00 (0.86,1.17) | 0.90 (0.79,1.03) | 0.93 (0.79,1.09) |

| Gender*Neuroticism | 1.03 (0.87,1.22) | 0.98 (0.84,1.13) | 0.79 (0.66,0.94)⁎⁎ |

| Gender*Agreeableness | 1.14 (0.94,1.40) | 1.00 (0.85,1.21) | 1.01 (0.83,1.23) |

| Con. | 0.20 (0.10,0.40)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.26 (0.15,0.46)⁎⁎⁎ | 0.24 (0.13,0.45)⁎⁎⁎ |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Compared to the healthy group (N = 11,393).

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

Fig. 1.

The interaction effects of gender and personality traits on changes in depressive symptoms (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

In this longitudinal analysis, we investigate the association between personality traits and changes in depressive symptoms in Chinese adults. Our results show that conscientiousness and neuroticism are related to persistent depressive symptoms. The findings also suggest that women demonstrate a stronger association between personality traits and changes in depressive symptoms than men.

Firstly, our findings suggest a positive correlation between neuroticism, openness, and changes in depressive symptoms, which aligns with previously reported studies. It is well-established that individuals with high neuroticism are more prone to sadness, anxiety, self-consciousness, and vulnerability and are more likely to experience negative emotions (Guo et al., 2020). Neuroticism is also an independent predictor of depressive symptoms and anxiety (Van Loey et al., 2014). In general, those with high neuroticism may be more prone to experience stressful events and have a poor capacity to regulate their negative emotions (Xu et al., 2020). Generally, openness is divided into six narrow-band aspects: Fantasy, Aesthetics, Feelings, Actions, Ideas, and Values (McCrae et al., 2005). Researchers have found that individuals who score well on Feelings experience a broader range of positive and negative emotions, including perhaps feelings related to depression. People with Fantasies are likely to experience and report depression because their idealized state of reality differs significantly from their actual state, leading to feelings like disappointment or sadness (Khoo and Simms, 2018). Consequently, a well-regulated and relatively conservative personality may partially protect individuals from the increased risk of depressive symptoms.

According to this study's findings, less conscientious, extroverted, and agreeable are associated with fewer depressive symptoms, which is in harmony with the previous studies. Moreover, it appears that conscientiousness is inversely related to depressive symptoms. Since being conscientious implies stronger self-regulation and the capacity to regulate emotions, it may lower the risk of internalizing problems (Smith et al., 2017). Researchers have hypothesized that highly conscientious people are more likely to adhere to social norms and public health recommendations concerning health behaviors (Roberts et al., 2009). This implies that low conscientiousness may affect improvement in depressive symptoms (Tabala et al., 2020). Extroversion indicates better interpersonal relationships and positive emotions, suggesting that people experience less stressful events and experience more positive feelings (Chen et al., 2020).

Spinhoven et al. demonstrated that a lack of positive emotionality as one of the most important facets of extraversion is related to depressive symptoms (Spinhoven et al., 2014). Previous research has presented that people with higher agreeableness have a more heightened sense of trust and willingness to cooperate and tend to be more humble and able to help others (Tulin et al., 2018). High agreeableness can make people adapt to new environments and constant changes, which may help reduce stress and avoid depressive symptoms (Kim et al., 2016). In this study, five dimensions of personality traits were significantly associated with changes in depressive symptoms from 2018 to 2020. Previous studies revealed that personality traits are at least somewhat malleable and may even predict depression years in advance, making them an attractive method of identifying individuals at risk (Klein et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2021).

Additionally, we find that all five personality factors were significantly associated with those whose depressive symptoms worsened, possibly because these individuals experienced depressive episodes. There is some evidence that personality traits are a relatively stable structure, whereas depressive symptoms have persistent fluctuations and instability, so the relationship between them is unstable (Prenoveau et al., 2011). Depression is so prevalent among those in the mental health world that Seligman once described it as the ‘common cold’ of the psychology (Seligman, 1973). Thus, researchers, healthcare professionals, and the public should be aware that personality traits may continue to influence individuals for a long time therefore ongoing surveillance and services are needed.

What makes this study particularly interesting is that gender plays a moderator role in the relationship between neuroticism, conscientiousness, and persistent depressive symptoms. This is highly consistent with the findings of Grav et al., although their study only found a significant interaction of gender with neuroticism on depressive symptoms (Grav et al., 2012). Specifically, we find that women are more likely to maintain depressive symptoms, which strongly agrees with previous evidence. It is possible for negative emotionality to lead to depression through several pathways (Hyde et al., 2008). Explanations from prior studies suggest that women are higher in negative emotionality from early childhood (Hyde and Mezulis, 2020). Temperament and stress interaction may also play a role, with girls and women experiencing more stress than boys and men, beginning in early adolescence (Sherman et al., 2016). Additionally, women are more likely to express their distress and seek out external help, and they are more inclined to receive mental health treatment for depression symptoms (Kapfhammer, 2022). Thus, healthcare providers, researchers, and government officials must develop personalized strategies to guide mental health treatment.

From our findings, the confounding variables we included are all related to depressive symptoms. First, rural areas are significantly associated with depressive symptoms, which is consistent with the findings of Tomita et al. (Chen et al., 2021; Tomita et al., 2017). Perhaps this is because rural residents have limited access to social resources and opportunities in comparison with urban residents (Hu et al., 2018). In addition, among the subgroups who are persistently depressed, younger and middle-aged people are more likely to suffer. It could be related to the fact that younger adults are more likely to report worrying about interpersonal relationships, school/work, and finances (Li et al., 2021; Wuthrich et al., 2015), and specific negative events such as unemployment are associated with depression (Han et al., 2022; Zhong et al., 2018). Finally, residents' self-rated health status significantly correlates with depressive symptoms. Relevant clinical studies have demonstrated that people with a history of illness are more likely to develop mental illness (Bogdan et al., 2020). This is highly consistent with our findings. Therefore, better understanding the difference between the risk factors of depressive symptoms will help in developing more specific, personalized interventions to improve mental health.

4.1. Implications

To the authors' knowledge, this study is one of the few comprehensive longitudinal studies about the relationship between personality traits and depressive symptoms. Our findings indicate that five dimensions of personality traits are all associated with changes in depressive symptoms. Thus, better knowledge of the relationship between personality traits and depressive symptoms might be helpful for the development of more effective prevention and intervention strategies. This study provides preliminary evidence for the interaction effects of gender and personality traits on depressive symptoms among Chinese adults. It is suggested that female Chinese adults with higher neuroticism and lower conscientiousness may be regarded as a high-risk group for depressive symptoms.

Additionally, because the CES-D measures a wide variety of mood states, these findings apply to mood states that may not meet the criteria for major depression. Still, they are nonetheless significant to overall mental health. Therefore, this study calls for continued mental health research, screening, and treatment, especially among high-risk populations.

4.2. Limitations

First, although it is a follow-up study, it is insufficient to determine a causal relationship between personality traits and depressive symptoms. Second, potential confounding factors, such as life events, were not measured or adjusted for in the analysis. Third, the data came from residents' self-assessments, and there are certain inaccuracies in the self-assessment of health and depressive symptoms, as well as personality traits measurements, which may affect the stability of the results. Moreover, this survey only asked whether the subject had a chronic disease or not, and it was impossible to further divide the disease groups and perform further analyses. The CES—D—8 is a screening tool rather than a clinical diagnostic method, so the prevalence of depression was probably somewhat overestimated in this study. Research on similar topics should use clinical diagnostic measurements, if possible, to increase the credibility of the findings among clinicians.

Furthermore, recently published literature on the psychological impact caused by the COVID-19 pandemic on people's mental health has shown increased depressive and anxiety symptoms, so this statement needs some consideration in our study (Santomauro et al., 2021). Finally, previous research indicated that seasonal differences in mood and depressive symptoms affect a large percentage of the general population (Tonetti et al., 2007; Wirz-Justice et al., 2019). Unfortunately, we did not have access to the monthly data, which should be considered in the future research plan.

5. Conclusions

Five factors of personality traits are all associated with changes in depressive symptoms. Neuroticism is positively related to those with persistent depressive symptoms, while conscientiousness is negatively related. Gender moderates the relationship between personality traits and depressive symptoms. Specifically, women demonstrate a stronger association between personality traits and changes in depressive symptoms than men.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

TW drafted the manuscript. QL was responsible for research instrument development and data analysis. HL, QS, FY, BZ and FA was involved revising the manuscript. WJ and JG were involved in the design of this study. All authors were involved in writing the manuscript and approve of its final version.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Number: 72174007) to Weiyan Jian.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University, Beijing, China. All participants gave written consent after being informed to the aim of the survey and their rights to refuse to participate.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to report.

Acknowledgements

This study would like to thank those who voluntarily participant in this research, especially respondents who give their valuable information.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.085.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary tables

Data availability

This data comes from China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), which has obtained permission for data use. The data sources are as follows: http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/sjzx/gksj/index.htm

References

- Adan A., Navarro J.F., Forero D.A. Personality profile of binge drinking in university students is modulated by sex. A study using the alternative five factor model. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;165:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan A., Barnett C., Ali A., AlQwaifly M., Abraham A., Mannan S., Ng E., Bril V. Chronic stress, depression and personality type in patients with myasthenia gravis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020;27:204–209. doi: 10.1111/ene.14057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs R., Carey D., O'Halloran A.M., Kenny R.A., Kennelly S.P. Validation of the 8-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale in a cohort of community-dwelling older people: data from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2018;9:121–126. doi: 10.1007/s41999-017-0016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs R., Carey D., O'Halloran A.M., Kenny R.A., Kennelly S.P. Validation of the 8-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale in a cohort of community-dwelling older people: data from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2018;9:121–126. doi: 10.1007/s41999-017-0016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulut N.S., Yorguner N., Akvardar Y. Impact of COVID-19 on the life of higher-education students in Istanbul: relationship between social support, health-risk behaviors, and mental/academic well-being. Alpha Psychiatry. 2021;22:291–300. doi: 10.5152/alphapsychiatry.2021.21319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Kong W., Lian Y., Jin X. Depressive symptoms among Chinese informal employees in the digital era. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Qiu L., Ho M.-H.R. A meta-analysis of linguistic markers of extraversion: positive emotion and social process words. J. Res. Pers. 2020;89 doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Huang Y., Riad A. Gender differences in depressive traits among rural and urban Chinese adolescent students: secondary data analysis of nationwide survey CFPS. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L.A., Watson David. In: Temperament: A New Paradigm for Trait Psychology. Pervin L.A., John O.P., editors. Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dalgard O.S., Dowrick C., Lehtinen V., Vazquez-Barquero J.L., Casey P., Wilkinson G., Ayuso-Mateos J.L., Page H., Dunn G., Grp O. Negative life events, social support and gender difference in depression - a multinational community survey with data from the ODIN study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006;41:444–451. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot A.J., Gallegos A.M., Moynihan J.A., Chapman B.P. Associations of mindfulness with depressive symptoms and well-being in older adults: the moderating role of neuroticism. Aging Ment. Health. 2019;23:455–460. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1423027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney J., Kenny R.A. Hair cortisol as a risk marker for increased depressive symptoms among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychoneuroendocrino. 2022;143 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2022.105847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier J., Jones N., Chase H., Cummings L., Graur S., Phillips M. Personality dysfunction in depression and individual differences in effortful emotion regulation. Biol. Psychiatry. 2017;81:S336–S337. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.02.897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlitz J.Y., Schupp J. 2005. Zur Erhebung der Big-Five-basierten Persönlichkeitsmerkmale im SOEP. DIW Research Notes 4. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves Pacheco J.P., Silveira J.B., Cock Ferreira R.P., Lo K., Schineider J.R., Azevedo Giacomin H.T., San Tam W.W. Gender inequality and depression among medical students: a global meta-regression analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019;111:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grav S., Stordal E., Romild U.K., Hellzen O. The relationship among neuroticism, extraversion, and depression in the HUNT Study: in relation to age and gender. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012;33:777–785. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.713082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P., Cui J., Wang Y., Zou F., Wu X., Zhang M. Spontaneous microstates related to effects of low socioeconomic status on neuroticism. Sci. Rep. 2020;10 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72590-7. Uk. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn E., Gottschling J., Spinath F.M. Short measurements of personality – validity and reliability of the GSOEP Big Five Inventory (BFI-S) J. Res. Pers. 2012;46:355–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2012.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z., Shen M., Liu H., Peng Y. Topical and emotional expressions regarding extreme weather disasters on social media: a comparison of posts from official media and the public. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2022;9 doi: 10.1057/s41599-022-01457-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward R.D., Taylor W.D., Smoski M.J., Steffens D.C., Payne M.E. Association of five-factor model personality domains and facets with presence, onset, and treatment outcomes of major depression in older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2013;21:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C.-R., Qin X. Depression hurts, depression costs: the medical spending attributable to depression and depressive symptoms in China. Health Econ. 2018;27:525–544. doi: 10.1002/hec.3604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H., Cao Q., Shi Z., Lin W., Jiang H., Hou Y. Social support and depressive symptom disparity between urban and rural older adults in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2018;237:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde J.S., Mezulis A.H. Gender differences in depression: biological, affective, cognitive, and sociocultural factors. Harv.Rev.Psychiatry. 2020;28:4–13. doi: 10.1097/hrp.0000000000000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde J.S., Mezulis A.H., Abramson L.Y. The ABCs of depression: integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychol. Rev. 2008;115:291–313. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.115.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapfhammer H.-P. Somatic symptoms in depression. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2022;8:227–239. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.2/hpkapfhammer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo S., Simms L.J. Links between depression and openness and its facets. Personal. Ment. Health. 2018;12:203–215. doi: 10.1002/pmh.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.E., Kim H.N., Cho J., Kwon M.J., Chang Y., Ryu S., Shin H., Kim H.L. Direct and indirect effects of five factor personality and gender on depressive symptoms mediated by perceived stress. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D.N., Kotov R., Bufferd S.J. In: Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. NolenHoeksema S., Cannon T.D., Widiger T., editors. 2011. Personality and depression: explanatory models and review of the evidence; pp. 269–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocjana G.Z., Kavčičb T., Avseca A. Resilience matters: explaining the association between personality and psychological functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2021;21 doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Sun H., Xu W., Ma W., Yuan X., Niu Y., Kou C. Individual social capital and life satisfaction among Mainland Chinese adults: based on the 2016 China Family Panel Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.Q., He H.R., Yang J., Feng X.J., Zhao F.F., Lyu J. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;126:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon K.E., Krueger R.F., Watson D. Delineating the structure of normal and abnormal personality: an integrative hierarchical approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005;88:139–157. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae R.R., Costa P.T., Martin T.A. The NEO-PI-3: a more readable revised NEO Personality Inventory. J. Pers. Assess. 2005;84:261–270. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8403_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng W., Adams M.J., Reel P., Rajendrakumar A., Huang Y., Deary I.J., Palmer C.N.A., McIntosh A.M., Smith B.H. Genetic correlations between pain phenotypes and depression and neuroticism. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020;28:358–366. doi: 10.1038/s41431-019-0530-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naragon-Gainey K., Watson D. Consensually defined facets of personality as prospective predictors of change in depression symptoms. Assessment. 2014;21:387–403. doi: 10.1177/1073191114528030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navrady L.B., Adams M.J., Chan S.W.Y., Ritchie S.J., McIntosh A.M. Genetic risk of major depressive disorder: the moderating and mediating effects of neuroticism and psychological resilience on clinical and self-reported depression. Psychol. Med. 2018;48:1890–1899. doi: 10.1017/s0033291717003415. Major Depressive Disorder, W. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaite V., Rottenberg J., Bylsma L.M. Daily affective dynamics predict depression symptom trajectories among adults with major and minor depression. Affect.Sci. 2020;1:186–198. doi: 10.1007/s42761-020-00014-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenoveau J.M., Craske M.G., Zinbarg R.E., Mineka S., Rose R.D., Griffith J.W. Are anxiety and depression just as stable as personality during late adolescence? Results from a three-year longitudinal latent variable study. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2011;120(4):832–843. doi: 10.1037/a0023939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiong W., Liping G. Application of simplified personality scale in large-scale comprehensive surveys in China. Research World. 2020:53–58. doi: 10.13778/j.cnki.11-3705/c.2020.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L.S. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts B.W., Smith J., Jackson J.J., Edmonds G. Compensatory conscientiousness and health in older couples. Psychol. Sci. 2009;20:553–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salk R.H., Hyde J.S., Abramson L.Y. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol. Bull. 2017;143:783–822. doi: 10.1037/bul0000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santomauro D.F., Mantilla Herrera A.M., Shadid J., Whiteford H.A., Ferrari A.J. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398:1700–1712. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom S.C. Between the error bars: how modern theory, design, and methodology enrich the personality-health tradition. Psychosom. Med. 2019;81:408–414. doi: 10.1097/psy.0000000000000701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman M.E. Psychology Today. Vol. 7. 1973. Fall into helplessness; p. 43-&. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman B.J., Vousoura E., Wickramaratne P., Warner V., Verdeli H. Temperament and major depression: how does difficult temperament affect frequency, severity, and duration of major depressive episodes among offspring of parents with or without depression? J. Affect. Disord. 2016;200:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shokrkon A., Nicoladis E. How personality traits of neuroticism and extroversion predict the effects of the COVID-19 on the mental health of Canadians. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K.A., Barstead M.G., Rubin K.H. Neuroticism and conscientiousness as moderators of the relation between social withdrawal and internalizing problems in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017;46:772–786. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0594-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinhoven P., Elzinga B.M., van Hemert A.M., de Rooij M., Penninx B.W. A longitudinal study of facets of extraversion in depression and social anxiety. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2014;71:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabala K., Wrzesinska M.A., Stecz P., Makosa G., Kocur J. Correlates of respiratory admissions frequency in patients with obstructive lung diseases: coping styles, personality and anxiety. Psychiatr. Pol. 2020;54:303–316. doi: 10.12740/PP/OnlineFirst/109823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita A., Vandormael A.M., Cuadros D., Di Minin E., Heikinheimo V., Tanser F., Slotow R., Burns J.K. Green environment and incident depression in South Africa: a geospatial analysis and mental health implications in a resource-limited setting. Lancet Planet. Health. 2017;1:e152–e162. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30063-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonetti L., Barbato G., Fabbri M., Adan A., Natale V. Mood seasonality: a cross-sectional study of subjects aged between 10 and 25 years. J. Affect. Disord. 2007;97:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulin M., Lancee B., Volker B. Personality and social capital. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2018;81:295–318. doi: 10.1177/0190272518804533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eeden W.A., van Hemert A.M., Carlier I.V.E., Penninx B.W., Spinhoven P., Giltay E.J. Neuroticism and chronicity as predictors of 9-year course of individual depressive symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;252:484–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loey N.E., Oggel A., Goemanne A.-S., Braem L., Vanbrabant L., Geenen R. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and neuroticism in relation to depressive symptoms following burn injury: a longitudinal study with a 2-year follow-up. J. Behav. Med. 2014;37:839–848. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9545-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A.L., Craske M.G., Mineka S., Zinbarg R.E. Neuroticism and the longitudinal trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms in older adolescents. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2021;130:126–140. doi: 10.1037/abn0000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirz-Justice A., Ajdacic V., Rossler W., Steinhausen H.C., Angst J. Prevalence of seasonal depression in a prospective cohort study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019;269:833–839. doi: 10.1007/s00406-018-0921-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Jin S., Guo J., Zhu Y., Chen L., Huang Y. The economic burden associated with depressive symptoms among middle-aged and elderly people with chronic diseases in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19 doi: 10.3390/ijerph191912958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuthrich V.M., Johnco C.J., Wetherell J.L. Differences in anxiety and depression symptoms: comparison between older and younger clinical samples. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:1523–1532. doi: 10.1017/s1041610215000526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Hu J.W. An introduction to the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) Chin.Sociol.Rev. 2014;47:3–29. doi: 10.2753/Csa2162-0555470101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Lu P. The sampling design of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) Chin. J. Sociol. 2015;1:471–484. doi: 10.1177/2057150X15614535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C., Xu Y., Xu S., Zhang Q., Liu X., Shao Y., Xu X., Peng L., Li M. Cognitive reappraisal and the association between perceived stress and anxiety symptoms in COVID-19 isolated people. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Sun H.Y., Zhu B., Yu X., Niu Y.L., Kou C.G., Li W.J. The prevalence of depressive symptoms and its determinants among adults in mainland China: results from a national household survey. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;281:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S., Eisenman D., Han Z. Temporal dynamics of public emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic at the epicenter of the outbreak: sentiment analysis of weibo posts from wuhan. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23 doi: 10.2196/27078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang X., Li B., Zhao L., Yan D., Yang L. end-to-end depression recognition based on a one-dimensional convolution neural network model using two-Lead ECG signal. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 2022;42:225–233. doi: 10.1007/s40846-022-00687-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Q.-Y., Gelaye B., VanderWeele T.J., Sanchez S.E., Williams M.A. Causal model of the association of social support with antepartum depression: a marginal structural modeling approach. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018;187:1871–1879. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Feng L., Hu C., Pao C., Xiao L., Wang G. Associations among depressive symptoms, childhood abuse, neuroticism, social support, and coping style in the population covering general adults, depressed patients, bipolar disorder patients, and high risk population for depression. Front. Psychol. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables

Data Availability Statement

This data comes from China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), which has obtained permission for data use. The data sources are as follows: http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/sjzx/gksj/index.htm