Abstract

Policy Points.

To meaningfully impact population health and health equity, health care organizations must take a multipronged approach that ranges from education to advocacy, recognizing that more impactful efforts are often more complex or resource intensive.

Given that population health is advanced in communities and not doctors’ offices, health care organizations must use their advocacy voices in service of population health policy, not just health care policy.

Foundational to all population health and health equity efforts are authentic community partnerships and a commitment to demonstrating health care organizations are worthy of their communities’ trust.

Keywords: population health, health equity, medicine

Though there is no definitive history of the “population health approach,” 1 relevant methods and practice have been deployed for centuries. Although a common population health lexicon is still in development, 2 in their seminal 2003 paper “What Is Population Health?,” Kindig and Stoddart define the “relatively new term” as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.” 3

More recently, the Interdisciplinary Association for Population Health Science (IAPHS) has firmly placed health equity as a central focus of the field and on the development of a health‐in‐all‐policies agenda to advance equitable health opportunity for all communities. IAPHS notes that population health involves:

an interdisciplinary and multi‐method approach to producing knowledge about: population health levels & disparities; the intertwined & multi‐level causes of health and disease, from genes, to behavior, to social and physical environments; the mechanisms through which health and health disparities are produced; and what policies and practices will improve population health and ameliorate health disparities. 4

According to these definitions health care is but one of the “mechanisms” across many levels that contribute to population health, giving it a necessary yet insufficient role to play in developing (and being part of) the multisector and multilevel solutions that improve the health of populations generally and eliminate unjust, systematic, avoidable inequities in health between groups.

However, the health care system has been relatively late to the field of population health as defined here, and it initially adopted a much narrower approach to the health of populations, an approach dubbed “population health management.” 5 Sparked by medicine's pursuit of “the Triple Aim” 6 (improving individual experiences of care, the health of populations, and cost reduction) and by the contemporaneous and ongoing shift from volume‐based payments to value‐based payments, medical care organizations have focused on the health and outcomes of patient populations defined by a common insurance product as opposed to communities defined by geography or shared sociodemographic characteristics. Although important, IAPHS notes such “health‐improvement strategies tend to be centered around quality of care and individual‐level interventions, leaving out a very important aspect of population health—improving the contexts that make people healthy or sick.” 4

Recently, though, both the commitment to and the focus of medicine's population health efforts have begun to broaden. According to leadership of the group Population Health Leaders in Academic Medicine (PHLAM), the number of population health departments within medical schools leapt from 9 in 2018 to roughly 35 in 2021 (written communication, September 2021). PHLAM notes that the focus of these departments is diverse and runs the gamut from population health management efforts of accountable care organizations to community codeveloped participatory research projects. 7 Medicine's growing focus on population health is mirrored by initiatives to embed population health principles in medical education, 8 , 9 reinforced by regulatory requirements for not‐for‐profit hospitals such as community health needs assessments (CHNA), and enhanced by the growing practice of screening for and intervening on patients’ health‐related social needs (HRSN). 10 However, these efforts are largely siloed, rarely evaluated, and typically untethered from a central, cohesive theory of change and practice.

To help achieve health equity and population health, the health care system must become the best partner it can be in the multisector collaborations necessary to shift underlying structures and systems toward health opportunity for all communities. 11 To become that best partner, health care needs an operationalizable framework that plays to medical care organizations’ strengths, “right‐sizes” their roles and spheres of influence, and connects current health care activities to population health efforts within and across communities.

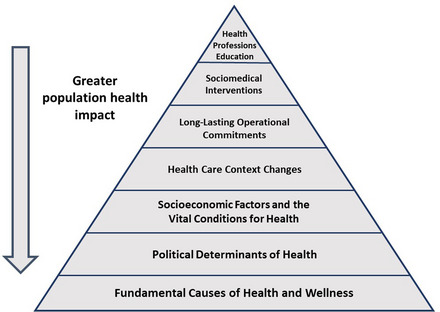

To that end, in this paper we reimagine Frieden's Health Impact Pyramid 12 as a Population Health Impact Pyramid for Health Care to demonstrate how the field of medicine can maximally contribute to the health of populations, not just patients, through specific actions and collaborations. We also suggest recommendations about how the actions described in each tier can be supported through policy changes at federal, state, local, and organizational levels.

A New Framework for Action: The Population Health Impact Pyramid for Health Care

The Health Impact Pyramid as initially proposed by Frieden is a five‐tier framework that ranks public health actions in terms of their population health impact. Actions at the base of the pyramid (addressing socioeconomic factors through broad public health interventions that change a community's context for health, such as ensuring clean water) have the largest impact and require less individual effort, but are often controversial because of the political commitment they require. Public health action in the top tiers is designed to help individuals rather than populations so may have a more modest impact, comparatively, but can contribute to population health when scaled and implemented broadly. Such interventions include counseling and education and direct medical care. Importantly, Frieden claims, a successful strategy deploys actions across all tiers to comprehensively address multiple factors that drive population health.

Frieden's Health Impact Pyramid was itself a reframing of several models that had previously sought to stratify the impact of diverse types of clinical care, from population‐wide interventions through tertiary care, 13 including the pyramid for maternal and child health developed by the US Health Resources and Services Administration. In developing a framework focused entirely on public health actions, Frieden's pyramid provided clarity on the most effective interventions. We see a need to reintegrate health care into that model to provide a framework for action by medical care organizations that want to impact the health of communities, the nation, and the world.

Here we modify the 2010 framework and reinterpret it as a Population Health Impact Pyramid for Health Care to focus on how medicine and medical care organizations can best contribute to population health (Figure 1). As in prior iterations of health impact pyramids, the initiatives in the topmost tier reflect action at the individual action but here are focused on actions and interventions that can be driven or supported by medical professionals, medical care organizations, and health systems to impact the health of communities, not only narrowly defined patient populations. We address these tiers in order of increasing impact and have added two tiers to underscore the importance of the political determinants of health and so‐called fundamental causes of health and wellness.

Figure 1.

Population Health Impact Pyramid for Health Care [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Tier 1: Health Professions Education

When looking to change how medicine addresses a new field, concern, way of interacting with patients, or community need, the first call to action often involves a request that the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) revise its medical school accreditation standards to add mandatory instruction hours on specific topics to undergraduate medical education (UME). Recent such calls include incorporation of antiracism education 14 and training on conflicts of interest. 15 Mandating specific curricula for physician learners on the principles and importance of population health represents “low‐hanging fruit” in terms of complexity of intervention, but in no way ensures that every graduating student is competent or even conversant in the subject matter. However, while such educational activities are far removed from measurable outcomes on population health, they can facilitate the incorporation of future physicians into efforts to improve it.

UME programs are increasingly incorporating elements of population health and social determinants of health education into their curricula on a voluntary basis, but scoping reviews reveal a lack of “accepted tools or practices,” which “limit[s] development of robust learner or program evaluation.” 16 Professional associations have recently released new sets of career‐staged competencies that focus on health care equity in quality improvement and patient safety, 17 telehealth equity, 18 and equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI), 19 broadly. However, such associations do not develop or mandate curricula, leaving institutions themselves to innovate training and evaluation methods to assess the development of the endorsed skills. Accreditors at the graduate medical education level have launched important programs focusing on how “equity matters,” 20 though such efforts have not yet resulted in new accreditation expectations or requirements.

Missing from medical education efforts are two critical factors: a clear, widely accepted delineation of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSA) all medical professionals must have to promote population health, and a faculty with the advanced knowledge and skills to teach those KSAs. Recent calls for academic medicine to develop a career track for “physician–public health practitioners” might eventually fill some of these gaps. 21

Collaboration itself is not an innate skill. We cannot expect medicine as a field to be the best partner it can be unless there are tools and training for the health professionals whose partnering capabilities are necessary to reach population health goals. It is not a core tenet of medical education to understand the value and necessity of multisector partnerships to improve population health on a broad scale. There is, however, a growing focus on the importance of collaboration and team‐based medicine, which could be broadened to teach the critical skills and relationships needed for multisector partnership to improve population health. Formed in 2009 by six health profession organizations, including the organization by which both authors are employed, the Interprofessional Education Collaborative has developed a set of four core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice. 22 Competency 2, revised in 2016, is to “use the knowledge of one's own role and those of other professions to appropriately assess and address the health care needs of patients and to promote and advance the health of populations.”

Tier 2: Sociomedical Interventions

Physicians and clinical care teams can build a population health approach to clinical care through “sociomedical interventions”—namely, integrating patient HRSN and community contexts as formal aspects of the clinical care intake and planning process. When formalized and routinized throughout a medical practice or health system, this intentional and comprehensive approach to understanding medical care in a patient's social context can help ensure medical intervention's effectiveness.

Translating organizational commitments to HRSN screening into effective clinical practice requires a reimagining of team member roles and care processes. For example, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐10) Z‐codes, which allow for the documentation of select HRSNs, are unique in that they do not require an MD or a DO to code them—any member of the care team can assign. Given the growing evidence of the effectiveness of community health workers (CHW) in enhancing health program sustainability and strengthening community‐clinic relationships, 23 , 24 medical care organizations should expand care teams to include professionals whose social and community skill set complements the clinical skill set of providers. Similar evidence points to the benefit of doulas, 25 promotoras, 26 and other community‐based practitioners as well positioned to effectively address social needs.

Formally incorporating lawyers as members of the care team via medical‐legal partnership (MLP) is another proven way to address patients’ health‐harming needs through the legal system, freeing the clinical team to address medical needs. 27 MLPs not only benefit an individual patient's health but can impact local and state policies (see Tier 6: Political Determinants of Health later in this paper) by producing evidence, data, and anecdotes that can be used to advocate for policies that would shift the health context for entire communities. 28 Similarly, some health care organizations are experimenting with medical‐financial partnerships, which provide patients and employees access to financial service professionals to address economic factors that impede health and wellness. 29

Commitments to screen and diagnose patients’ social needs are all for naught without appropriate referral to community assets and resources, and without “closing the loop” to understand whether and why (or why not) social services were accessed. Too often medical care organizations rely on referrals automatically generated via for‐purchase databases and referral software, forgoing the essential work of developing personal relationships with the leaders and clientele of community‐based organizations and partners. Lawyers, CHWs, social workers, promotoras, and others are well positioned to provide “warm referrals,” matching patients and services not solely based on need and availability, but also on the alignment with patient preferences and degree of trust.

Tier 3: Long‐Lasting Operational Commitments

To be effective, health care organizations’ commitments to addressing population health and health equity must exist on multiple levels. While a public statement of leadership support and documentation of organizational intentions are important tone‐setting efforts, such commitments are hollow without commensurate actions.

Health care organizations’ long‐standing difficulty with the collection of valid race, ethnicity, and language (REL) data is well documented. 30 , 31 A similar lack of data across multiple agencies and states revealed itself during the COVID‐19 pandemic with various reports of significantly missing race and ethnicity data for cases and vaccinations. 32 , 33 Unfortunately, REL data are the tip of the iceberg of information we currently do not have and so desperately need to develop hyperlocal, effective population and health equity interventions. Beyond REL, such work requires that we understand individuals’ HRSNs (e.g., food insecurity, access to transportation, level of social support) and can describe the status of the vital conditions 34 for health in their community. Indeed, the lack of all three kinds of data—REL, HRSN, and community‐level social factors—is one of the largest barriers to advancing many of the health care policies described in this paper.

The standardized collection and use of individual HRSN data is not currently a core operational commitment. In a 2017 survey, 88% of hospitals reported screening patients for social risk factors, 10 yet only 1.9% of all US hospital admissions at that time documented such social needs via available Z‐codes. 35 The presence of social needs as documented by Z‐codes has been found to strongly correlate with unplanned readmissions, negative health events, and costs. 36 , 37 Including a more formal diagnosis, as opposed to jumping from screening directly to referral, would allow for an increased ability to understand the relationship at both patient and population levels between social risks and health care outcomes. Such data could also be applied to quality improvement efforts, accelerating the development of the evidence base of clinical processes and protocols that can ensure equitable, high‐quality care for all patient populations. 38 Many medical care organizations are developing “health equity dashboards” as an accountability mechanism that would be enhanced by a stronger commitment to more robust data collection. 39

Beyond community benefit requirements described later (Tier 5: Socioeconomic Factors and the Vital Conditions for Health), per the Affordable Care Act not‐for‐profit hospitals are also required to conduct triennial CHNAs to identify, prioritize, and intervene on health issues of greatest importance to the community. Such requirements, when conducted in true partnership with community members and the multiple sectors that serve them, can not only provide crucial information about local community assets, but can continue the work of demonstrating trustworthiness and building bidirectional communication between and among partners (see Tier 7). CHNAs can also serve as an organizing principle across the clinical (and education and research, if applicable) mission of the medical care organization. Again, CHNAs are often conducted and led by paid consultants, missing an opportunity for health care organizations to partner more authentically with local community members and groups.

Tier 4: Health Care Context Change

Changing the health care context for population health means expanding access, first and foremost. Ample evidence exists that policies such as Medicaid expansion significantly decrease inequities in insurance coverage and access to care, 40 , 41 and telehealth services hold promise to do the same when implemented in ways that intentionally focus on equitable access, use, and quality. 42 , 43

Primary care is associated with increased access as well as better health, 44 yet over the first decade and a half of this century the proportion of adult Americans reporting a usual source of primary care declined across all age groups. 45 Additionally, primary care has an outsized role to play in achieving health care equity given its focus on prevention and primary care providers’ ability to bridge medical care and social care. Frameworks have been proposed to transform primary care education and training in ways that promote health and health care equity. 46 Such efforts are central to changing the context in which health care is provided.

Changing that context also means ensuring that as we move from fee‐for‐service to value‐based purchasing, alternative payment models support rather than undermine population health care equity goals while also helping achieve population health management goals. In part, this means stratifying and risk adjusting performance measures so providers who care for the most socially complex patients are not unjustly penalized for community factors that impact patient health yet are unrelated to clinical quality. It also means, according to experts, multi‐payer alignment to incentivize the elimination of health care inequities (and to provide the resources and technical assistance needed to do so) as well as offering direct payments to community‐based organizations to fund partnerships and collaboration. 47 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has made it clear that promoting health care equity through new, equity‐focused accountable care organization models is a priority, 48 and accreditors like the Joint Commission have recently added health equity standards that require HRSN screening and demographic stratification, among other requirements. 49

Organizational actions related to becoming antiracist, anti‐discriminatory institutions that promote equity, diversity, and belonging are foundational to laying the groundwork for medicine's contribution to health and health care equity. A clinical environment that intentionally works to create equitable opportunities for staff, learners, practitioners, and administrators to advance, contribute, and thrive will contribute directly to health care equity and patient population health. The environment in which medical education occurs is of central importance, and accreditors have been rightfully focused on the clinical learning environment and how it can either clarify or obscure pathways to health care equity. 50

Many of the contextual shifts necessary for medicine to promote population health and health equity rely on political decisions around health care policy that connect the political determinants of health (Tier 6) with health care environments and contexts (Tier 4); the tiers in our pyramid are porous and interrelated. For example, access to clinical services is a bridge between this tier and the vital conditions for health on which it rests (Tier 5) and, of course, is at the mercy of political decisions (Tier 6) as to whether access expands or contracts.

Tier 5: Socioeconomic Factors and the Vital Conditions for Health

To successfully promote population health will require multisector partnerships and community collaborations that involve representatives of all the vital conditions for health 34 : humane housing, meaningful work, and reliable transportation, among others. Our political decisions and determinants (Tier 6) have inequitably distributed across our communities the resources we all need to thrive. In recognition that health care is but one of the basic needs for health and safety, the Association of American Medical Colleges, where both authors are employed, recently added “community collaborations” as a fourth mission through which health can be transformed, giving such partnerships the same import as clinical care, biomedical research, and medical education. 51

The federal government is similarly focused on multisector collaborations as a core component of its action plan to advance equity 52 and racial justice across the government, from the Department of Labor to the Environmental Protection Agency to the Department of Justice. A related effort on federal long‐term recovery and resilience is being coordinated by the US assistant secretary for health. This represents a whole‐of‐government effort, inclusive of health and non‐health sectors, to “cooperatively strengthen the vital conditions necessary for improving individual and community resilience and well‐being nationwide.” 53

Beyond coalitions and partnerships, health care organizations, as stable, well‐resourced institutions that are often among the largest employers in their communities, have a significant role to play and assets to bear on the kind of local, state, and federal work required to ensure the vital conditions for health in all communities. As a local economic engine, medical care organizations can become part of the “health care anchor institution” movement 54 to contribute directly to community economic development. By setting goals for local hiring, prioritizing local businesses in their procurement processes, ensuring living wages and equitable retirement savings programs, and investing a proportion of their discretionary investment portfolio in local businesses, health care institutions can directly contribute to local economic vitality.

One way to ease the path for such “vital conditions” activity is to give such commitments more prominence on tax forms related to not‐for‐profit hospitals’ community benefit requirements. One of us has argued 55 that the current requirement from the Internal Revenue Service captured on Schedule H of Form 990 incentivizes charity care and subsidized health services for patients to a greater extent than actions described in lower, more impactful tiers of our pyramid, which would be more likely to yield greater benefit to the community at large.

Finally, medical care organizations can play a role in fomenting civic engagement—the vital condition for health at the center of that framework. Recently, health care organizations are helping build that engagement via efforts to increase voter registration and civic participation for patients, staff, and communities alike in nonpartisan ways. 56 , 57 , 58

Tier 6: Political Determinants of Health

From redlining to restricting voting access to denying gender‐affirming care, the policy actions that a state or a nation takes can either promote equitable population health or create and maintain unjust differences in health between groups. Thus, the policy choices made at all levels of government and governance will create the social contexts, barriers, and advantages for groups of people that will not only impact but in many cases may determine their health outcomes.

In the words of Daniel Dawes, “the government . . . at every stage of our life, whether through policy or legal actions or inactions, through a complex web of political structures and processes that have been created at the international, federal, state and local levels, impacts our health status.” 59

For the field of medicine and health care organizations, specifically, to demonstrate that they are serious about population health, they must raise their voices and advocate for health and not just health care. Though there are prohibitions on nonprofit health care organizations advocating for specific candidates, no such barrier exists for issue‐focused advocacy. While the American Medical Association has called for individual physicians to “advocate for social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human wellbeing,” 60 and both the Association of American Medical Colleges and the American Hospital Association have formally incorporated health equity into their advocacy agendas, 61 , 62 associations representing health care organizations themselves largely limit their advocacy to issues related to care access, insurance, patient safety and quality, workforce, and affordability of care. While those issues are important from a health care equity and a population health management perspective, they ignore the contexts in which care is provided. Given that medical care contributes roughly 20% to a person's or a community's health, 63 population health advocacy necessarily extends beyond the issues most germane within a hospital's walls.

Physician leaders are particularly effective advocates and spokespeople and thus have an outsized role to play in addressing deleterious and inequity‐producing political determinants. 64 In addition to referring patients to housing services, for example, hospitals could advocate for policies promoting the creation of local affordable housing units. Beyond hosting a farmer's market in a hospital parking lot, health systems can also advocate for zoning changes and subsidies attracting supermarkets to food deserts.

One crucial set of political decisions that impact medicine's and all other sectors’ ability to maximally contribute to population health and health equity is how and what data we collect. From documented undercounting of certain racial and ethnic minority populations in the 2020 Census 65 to political platforms that promise the “government will never again ask American citizens to disclose their race, ethnicity, or skin color on any government form,” 66 to the Office of Management and Budget's only recent movement towards adding a Middle Eastern/North African demographic category for information collected for federal statistical purposes (members of that population must currently self‐identify as white), 67 our actions and inactions around data limit what we can know about our populations and thus how we can most effectively improve their health.

Indeed, many of the efforts in all tiers require a renewed political commitment to robust data collection paired with an on‐the‐ground organizational and operational commitment to gather, report, make available, and use data in ways that amplify and multiply efforts to improve population health, engage communities, and achieve health equity. Those political commitments can involve state and federal legislation that provides requirements and funding for data collection that facilitates population health and health equity improvements. The development of robust and comprehensive data sets that can meaningfully impact health requires complex coordination and a national commitment to avoid piecemeal approaches that render data from disparate sources unable to be compared or combined.

Although the recent creation through executive order of an Equitable Data Working Group 68 is an important acknowledgment of how our lack of data has “cascading effects and impedes efforts to measure and advance equity,” 68 the group's charge focuses squarely on the collection of key demographic variables such as race, gender, ethnicity, income, disability, and so on. Demographic data are crucial to document inequities (so‐called First Generation Health Equity Research). 69 To move to the third‐generation science of solutions, however, will require nation‐wide collection of intervenable social factor data, ideally a core set of measures standardized across communities (with flexibility to develop additional more locally meaningful metrics), complemented by qualitative data to ensure solutions are grounded in community perspective and voice.

Tier 7: Fundamental Causes of Health and Wellness

To have the broadest impact on health equity and population health, medicine must hold an unerring commitment to broaden its field of reference beyond the genetic, molecular, and pathogenic causes of disease to include so‐called fundamental causes, understanding that powerful social conditions well beyond the control of an individual will to a large extent determine the health outcomes for people and populations. It is intentional that we ground the Population Health Impact Pyramid for Health Care in the fundamental causes of disease like classism and racism, not only because of their outsized impact on health, but also because there are few or no actions that medicine can take in a siloed approach that will address these causes. No lab, hospital, care team, or physician can take on this tier alone. Yet the full engagement of the medical field as an engaged, committed, humble, and collaborative partner can have a meaningful and lasting impact on population health and health equity.

Link and Phelan position social conditions such as classism and racism as fundamental causes of disease. 70 These causes are “fundamental” because they control access to crucial resources such as information, money, power, and social capital, and they impact multiple health outcomes through multiple pathways so that when one pathway is blocked there are others through which the fundamental cause can exert influence. Thus, for medicine to promote population health and health equity, health care organizations and the people within them must collectively and actively reject the ways in which racism, classism, homophobia, sexism, and other social factors are reinforced by policy and practice.

The absence of those ‐isms and phobias can be considered a “fundamental cause of wellness” and can be achieved only through authentic community engagement and by institutions with power and privilege demonstrating they are worthy of their communities’ trust.

As noted with the discussion of Tier 4, over the past few years many medical care organizations, including hospitals, health systems, medical schools, and professional associations, have initiated work to become antiracist, 71 defined as “the active process of naming and confronting racism by changing systems, organizational structures, policies and practices and attitudes, so that power is redistributed and shared equitably.” 72 Such efforts highlight the complementary nature of health equity work and longstanding EDI efforts. Although distinct in goals and downstream operationalization, 73 EDI and population health share common, fundamental roots: namely, the social, racial, and economic injustices that manifest themselves in both the lack of workforce diversity (the fundamental causes of racism or classism taking an “education pathway”) and in the existence of unjust differences in health between populations (those same causes taking a “health pathway”). Medicine's efforts to address fundamental causes in and beyond its own house must be an “all‐hands‐on‐deck” affair.

Additionally, there has been increased national recognition that solutions to the fundamental causes at the root of health inequity and poor population health must be grounded in authentic, bidirectional community engagement, broadly defined as the application of institutional resources to address and solve challenges facing communities via collaboration with these communities. 74 Solutions are found in lived experience, not in textbooks. According to the National Academy of Medicine, such collaboration strengthens alliances and partnerships, expands knowledge in all directions, improves health‐focused programs and policies, and in the long term, leads to thriving communities. 75

For such partnerships to grow and sustain, medical care organizations must demonstrate they are worthy of their community's trust. Lack of trust in our medical and scientific organizations is well documented 76 and stems from a combination of historical and contemporary instances of abuse and maltreatment by the health care system, as well as mis‐ and disinformation that undermines the credibility of the field. Tools and resources exist for both individual providers 77 and their organizations 78 to “walk the talk” on trustworthiness, specifically by codeveloping with community partners concrete actions health care and other organizations can take to show they are committed to trustworthy behaviors such as respect, transparency, authenticity, and taking responsibility. Demonstration of trustworthiness is not simply a useful tool or metric but is an essential component that will determine the impact and effectiveness of population health efforts driven by health care institutions. Although in general the majority of Americans report trusting hospitals and universities as institutions, recent polling demonstrates that people trust some sectors more (like fire departments, libraries, and local businesses) to treat people fairly. 79

Implementation and Accountability

Operationalizing this pyramid across health care organizations will require complex, coordinated action across multiple areas, involving partners external to the organization itself. Using the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework as a guide, we offer recommendations for the kinds of process, context, and policy changes required to take multitiered action and increase medicine's contribution to population health. 80

Beginning with the medical care organization itself, EPIS's so‐called Inner Context, leadership must be held accountable for population health metrics, with progress tied to bonuses. These metrics should reflect outcomes important to the organization, to patients, and to local communities and must span pyramid tiers to focus on diverse domains such as learner outcomes, addressing HRSNs, effective equity‐promoting quality improvement projects, anchor investments, and successful advocacy work, to name a few.

At the organization level, institutions must invest in the infrastructure necessary for population health action. First (and to facilitate EPIS’ Bridging Factors like community academic partnerships), this means developing organizational competency for authentic community engagement and partnership. This involves implementing policies and practices for community cogovernance in all population health efforts, “fiscal readiness” 81 to ensure equitable and timely remuneration of community partners for their expertise, and merit and promotion policies that explicitly incentivize relationship building and maintenance as a prioritized goal even when not conducted in service of a research grant or experiential learning activity. A centralized office of community engagement, population health, or health equity led by a team with the relevant population health training and experience, can serve to ensure efforts are coordinated across all departments and offices, recognizing that community engagement is everyone's responsibility. Such an office can serve as the bridge for multisector partnerships given the breadth of the health ecosystem extends far beyond health care.

Similar Inner Context commitments focus on “quality monitoring,” and thus investing in the data infrastructure needed to codevelop and evaluate interventions is paramount. Not only does this mean investing in the collection of REL, HRSN, and community conditions data, but it also means creating a robust strategy to weave disparate data collections together in service of population health. Electronic medical record data, CHNA information, program evaluation metrics, and community benefit details (among others) can be interdigitated and reported together to create a more robust understanding of population health dynamics, institutional efforts, existing partnerships, and more.

EPIS also stresses staffing as a core inner contextual element, so investments in workforce development are also key. These include interprofessional training, a commitment to hiring community‐based practitioners even in the absence of reimbursement, and a deepening commitment to workforce diversity and belonging across all social and demographic characteristics.

These and other medical care organization actions do not exist in a vacuum, and Outer Context factors can either facilitate or hinder organizational efforts. Particularly, the actions of accreditors and health care policymakers play a significant role in catalyzing population health action. It is true that should CMS suddenly demand specific data collections or LCME require new curricular content, the resultant downstream shifts would be relatively swift. However, health care organizations must not wait for facilitative health care policies. They should build the evidence base for such policies in advance, understanding that an authentic population health and health equity strategy benefits clinical, financial, and moral obligations even in the absence of mandates.

Conclusions

In reimagining the influential Health Impact Pyramid, we believe that there is an important and collaborative role for the systems, organizations, and professionals who deliver medical care to improve health equity and the health of all. We do not suggest that medicine should take on additional public health roles or that the expertise gained through health professions education and clinical practice is alone sufficient to implement all actions throughout the pyramid. Instead, the Population Health Impact Pyramid for Health Care allows those people and organizations dedicated to the care of patients to more clearly envision how population health efforts can strengthen their own impact, build the health of their local communities, demonstrate their trustworthiness, and enhance their roles in influencing health outcomes through activities that may not include seeing patients. From individual learning to civic engagement to building an environment that dismantles the fundamental causes of inequity, medicine is part of the prescription to achieve health equity.

References

- 1. Szreter S. The population health approach in historical perspective. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):421‐431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peek CJ, Westfall JM, Stange KC, et al. Shared language for shared work in population health. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(5):450‐457. 10.1370/afm.2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kindig D, Stoddart G. What is population health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):380‐383. 10.2105/ajph.93.3.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. What is population health. Interdisciplinary Association for Population Health Science website. https://iaphs.org/what‐is‐population‐health/. Accessed September 9, 2022.

- 5. Felt‐Lisk S, Higgins P. Exploring the promise of population health management programs to improve health. Mathematica Policy Research. https://www.mathematica.org/publications/exploring‐the‐promise‐of‐population‐health‐management‐programs‐to‐improve‐health. Published August 2011. Accessed October 31, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759‐769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gourevitch MN, Curtis LH, Durkin MS, et al. The emergence of population health in US academic medicine: a qualitative assessment. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192200. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson SB, Fair MA, Howley LD, et al. Teaching public and population health in medical education: an evaluation framework. Acad Med. 2020;95(12):1853‐1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;104:126‐133. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee J, Korba C. Social determinants of health: how are hospitals and health systems investing in and addressing social needs? Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/life‐sciences‐health‐care/us‐lshc‐addressing‐social‐determinants‐of‐health.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed October 31, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Exploring Equity in Multisector Community Health Partnerships: Proceedings of a Workshop . Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2018:112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):590‐595. 10.2105/ajph.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. US Department of Health and Human Services. For a Healthy Nation: Returns on Investment in Public Health. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lawrence E. In medical schools, students seek robust and mandatory anti‐racist training. Washington Post . November 8, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/racism‐medical‐school‐health‐disparity/2020/11/06/6608aa7c‐1d1f‐11eb‐90dd‐abd0f7086a91_story.html. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 15. Medicine Institute of. Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009:436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Doobay‐Persaud A, Adler MD, Bartell TR, et al. Teaching the social determinants of health in undergraduate medical education: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(5):720‐730. 10.1007/s11606-019-04876-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Association of American Medical Colleges . Quality Improvement and Patient Safety Competencies Across the Learning Continuum. AAMC New and Emerging Areas in Medicine Series. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Association of American Medical Colleges . Telehealth Competencies Across the Learning Continuum. AAMC New and Emerging Areas in Medicine Series. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Association of American Medical Colleges . Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Competencies Across the Learning Continuum. AAMC New and Emerging Areas in Medicine Series. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20. ACGME equity matters . Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education website. https://www.acgme.org/what‐we‐do/diversity‐equity‐and‐inclusion/ACGME‐Equity‐Matters/. Accessed September 12, 2022.

- 21. Bibbins‐Domingo K, Fernandez A. Physician–Public Health Practitioners—The Missing Academic Medicine Career Track. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(3):e220949. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.0949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Interprofessional Education Collaborative . Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 update. https://ipec.memberclicks.net/assets/2016‐Update.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- 23. Kangovi S, Mitra N, Grande D, Long JA, Asch DA. Evidence‐based community health worker program addresses unmet social needs and generates positive return on investment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(2):207‐213. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scott K, Beckham SW, Gross M, et al. What do we know about community‐based health worker programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on community health workers. Human Resources for Health. 2018;16(1):39. 10.1186/s12960-018-0304-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gruber KJ, Cupito SH, Dobson CF. Impact of doulas on healthy birth outcomes. J Perinat Educ. 2013;22(1):49‐58. 10.1891/1058-1243.22.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Taverno Ross SE, Barone Gibbs B, Documet PI, Pate RR. ANDALE Pittsburgh: results of a promotora‐led, home‐based intervention to promote a healthy weight in Latino preschool children. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):360. 10.1186/s12889-018-5266-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Beck AF, Henize AW, Qiu TT, et al. Reductions in hospitalizations among children referred to a primary care–based medical‐legal partnership. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(3):341‐349. 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tobin‐Tyler E, Teitelbaum JB. Essentials of Health Justice: A Primer. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29. South E, Venkataramani A, Dalembert G. Building Black wealth—the role of health systems in closing the gap. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(9):844‐849. 10.1056/NEJMms2209521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ng JH, Ye F, Ward LM, Haffer SCC, Scholle SH. Data on race, ethnicity, and language largely incomplete for managed care plan members. Health Aff (Millwood) . 2017;36(3):548‐552. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cowden JD, Flores G, Chow T, et al. Variability in collection and use of race/ethnicity and language data in 93 pediatric hospitals. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7(5):928‐936. 10.1007/s40615-020-00716-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krieger N, Testa C, Hanage WP, Chen JT. US racial and ethnic data for COVID‐19 cases: still missing in action. Lancet. 2020;396(10261):e81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32220-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Krieger N, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Testa C, Hanage WP. Missing again: US racial and ethnic data for COVID‐19 vaccination. Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1259‐1260. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00465-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Milstein B, Payne B, Kelleher C, et al. Organizing around vital conditions moves the social determinants agenda into wider action. Health Affairs Forefront. February 2, 2023. 10.1377/forefront.20230131.673841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Truong HP, Luke AA, Hammond G, Wadhera RK, Reidhead M, Joynt Maddox KE. Utilization of social determinants of health ICD‐10 Z‐codes among hospitalized patients in the United States, 2016‐2017. Med Care. 2020;58(12):1037‐1043. 10.1097/mlr.0000000000001418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bensken WP, Alberti PM, Stange KC, Sajatovic M, Koroukian SM. ICD‐10 Z‐code health‐related social needs and increased healthcare utilization. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(4):e232‐e241. 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bensken WP, Alberti PM, Koroukian SM. Health‐related social needs and increased readmission rates: findings from the nationwide readmissions database. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(5):1173‐1180. 10.1007/s11606-021-06646-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):992‐1000. 10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tsuchida RE, Haggins AN, Perry M, et al. Developing an electronic health record–derived health equity dashboard to improve learner access to data and metrics. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5(Suppl.1):S116‐S120. 10.1002/aet2.10682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Adamson BJS, Cohen AB, Estevez M, et al. Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion impact on racial disparities in time to cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(18 Suppl):LBA1. 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.18_suppl.LBA1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee H, Hodgkin D, Johnson MP, Porell FW. Medicaid expansion and racial and ethnic disparities in access to health care: applying the National Academy of Medicine definition of health care disparities. Inquiry. 2021;58:0046958021991293. 10.1177/0046958021991293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lyles CR, Wachter RM, Sarkar U. Focusing on digital health equity. JAMA. 2021;326(18):1795‐1796. 10.1001/jama.2021.18459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Samuels‐Kalow M, Jaffe T, Zachrison K. Digital disparities: designing telemedicine systems with a health equity aim. Emerg Med J. 2021;38(6):474‐476. 10.1136/emermed-2020-210896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Levine DM, Landon BE, Linder JA. Quality and experience of outpatient care in the United States for adults with or without primary care. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):363‐372. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Levine DM, Linder JA, Landon BE. Characteristics of Americans with primary care and changes over time, 2002‐2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(3):463‐466. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Doubeni CA, Fancher TL, Juarez P, et al. A framework for transforming primary care health care professions education and training to promote health equity. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(4s):193‐207. 10.1353/hpu.2020.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. The MITRE Corporation . Advancing health equity through APMs: guidance for equity‐centered design and implementation. Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network. https://hcp‐lan.org/workproducts/APM‐Guidance/Advancing‐Health‐Equity‐Through‐APMs.pdf. Published 2021. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 48. Medicare Centers for and Services Medicaid. CMS Framework for Health Equity 2022‐2032. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms‐framework‐health‐equity‐2022.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2023.

- 49. Hartnett K. The Joint Commission to add health equity standards to accreditations. Modern Health . August 12, 2022. https://www.modernhealthcare.com/providers/joint‐commission‐add‐health‐equity‐standards‐accreditations. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 50. CLER Evaluation Committee . CLER pathways to excellence: expectations for an optimal clinical learning environment to achieve safe and high‐quality patient care, version 2.0. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pdfs/cler/1079acgme‐cler2019pte‐brochdigital.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed October 31, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Alberti P, Fair M, Skorton DJ. Now is our time to act: why academic medicine must embrace community collaboration as its fourth mission. Acad Med. 2021;96(11):1503‐1506. 10.1097/acm.0000000000004371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. House The White. Executive Order On Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government. January 20, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing‐room/presidential‐actions/2021/01/20/executive‐order‐advancing‐racial‐equity‐and‐support‐for‐underserved‐communities‐through‐the‐federal‐government/. Accessed February 3, 2023.

- 53. Equitable Long‐Term Recovery and Resilience website . https://health.gov/ourwork/national‐health‐initiatives/equitable‐long‐term‐recovery‐andresilience#:~:text=The%20Federal%20Plan%20for%20Equitable,resilience%20and%20well%2Dbeing%20nationwide.Resilience|health.gov. Accessed February 3, 2023.

- 54. Healthcare Anchor Network . https://healthcareanchor.network/. Accessed September 12, 2022.

- 55. Alberti P. The conversation about community health & social determinants has evolved. How we count hospitals’ contributions should follow suit. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/conversation‐community‐health‐social‐determinants‐has‐alberti/. Published July 15, 2019. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 56. Vot‐ER : healthy communities powered by an inclusive democracy. https://vot‐er.org/. Accessed September 12, 2022.

- 57. Civic Alliance. Civic Health Compact. Available at: https://www.civichealthalliance.org/compact. Accessed February 3, 2023.

- 58. Pierce, H . Healthcare Organizations Can Get Out the Vote. MedPage Today. September 20, 2022. Available at: https://www.medpagetoday.com/opinion/second‐opinions/100817

- 59. Dawes DE. The Political Determinants of Health. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 60. AMA declaration of professional responsibility. American Medical Association website. https://www.ama‐assn.org/delivering‐care/public‐health/ama‐declaration‐professional‐responsibility. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 61. Investing in healthier communities. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/advocacy‐policy/investing‐healthier‐communities. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 62.AHA 2022 advocacy agenda. American Hospital Association website. https://www.aha.org/advocacy‐agenda. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 63. County health rankings model. County Health Rankings and Roadmaps website. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore‐health‐rankings/measures‐data‐sources/county‐health‐rankings‐model. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 64. Rock M. The physician's role in political advocacy. Georgetown Med Rev. 2021;5(1). 10.52504/001c.21357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65. US Census Bureau . Census Bureau releases estimates of undercount and overcount in the 2020 census. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press‐releases/2022/2020‐census‐estimates‐of‐undercount‐and‐overcount.html. Published March 10, 2022. Accessed September 12, 2022.

- 66. 12 point plan. Rescue America website. https://rescueamerica.com/12‐point‐plan/. Accessed September 13, 2022.

- 67. Initial Proposals For Updating OMB's Race and Ethnicity Statistical Standards. 88 Fed Reg 5375. January 27, 2023.

- 68. Executive Order on Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government. White House website. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing‐room/presidential‐actions/2021/01/20/executive‐order‐advancing‐racial‐equity‐and‐support‐for‐underserved‐communities‐through‐the‐federal‐government/. Published January 20, 2021. Accessed September 12, 2022.

- 69. Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley‐Matoka M, Fine MJ. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2113‐2121. 10.2105/ajph.2005.077628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;Spec No:80‐94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Addressing and eliminating racism at the AAMC and beyond. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/addressing‐and‐eliminating‐racism‐aamc‐and‐beyond. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 72. American Medical Association and Association of American Medical Colleges . Advancing health equity: a guide to language, narrative and concepts. American Medical Association. http://ama‐assn.org/equity‐guide. Published 2021. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 73. Crews DC, Collins CA, Cooper LA. Distinguishing workforce diversity from health equity efforts in medicine. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(12):e214820. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.4820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wilkins CH, Alberti PM. Shifting academic health centers from a culture of community service to community engagement and integration. Acad Med. 2019;94(6):763‐767. 10.1097/acm.0000000000002711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Aguilar‐Gaxiola S, Ahmed SM, Anise A, et al. Assessing meaningful community engagement: a conceptual model to advance health equity through transformed systems for health; Organizing Committee for Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement in Health and Health Care Programs and Policies. NAM Perspect. 2022;2022:. 10.31478/202202c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Jaiswal J, Halkitis PN. Towards a more inclusive and dynamic understanding of medical mistrust informed by science. Behav Med. 2019;45(2):79‐85. 10.1080/08964289.2019.1619511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Trust in health care. ABIM Foundation website. https://abimfoundation.org/what‐we‐do/rebuilding‐trust‐in‐health‐care. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 78. The principles of trustworthiness . AAMC Center for Health Justice website. https://www.aamchealthjustice.org/resources/trustworthiness‐toolkit. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 79. Alberti P, Piepenbrink S. The state of trustworthiness. AAMC Center for Health Justice website. https://www.aamchealthjustice.org/news/polling/state‐trust. Published December 16, 2021. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 80. The EPIS implementation framework. EPIS website. https://episframework.com/. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 81. Carter‐Edwards L, Grewe ME, Fair AM, et al. Recognizing cross‐institutional fiscal and administrative barriers and facilitators to conducting community‐engaged clinical and translational research. Acad Med. 2021;96(4):558‐567. 10.1097/acm.0000000000003893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]