Abstract

Background

Digital patient monitoring (DPM) tools can facilitate early symptom management for patients with cancer through systematic symptom reporting; however, low adherence can be a challenge. We assessed patient/healthcare professional (HCP) use of DPM in routine clinical practice.

Materials and Methods

Patients with locally advanced/metastatic lung cancer or HER2-positive breast cancer received locally approved/reimbursed drugs alongside DPM, with elements tailored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, on the Kaiku Health DPM platform. Patient access to the DPM tool was through their own devices (eg, laptops, PCs, smartphones, or tablets), via either a browser or an app on Apple iOS or Android devices. Coprimary endpoints were patient DPM tool adoption (positive threshold: 60%) and week 1-6 adherence to weekly symptom reporting (positive threshold: 70%). Secondary endpoints included experience and clinical impact.

Results

At data cutoff (June 9, 2022), adoption was 85% and adherence was 76%. Customer satisfaction and effort scores for patients were 76% and 82%, respectively, and 83% and 79% for HCPs. Patients spent approximately 10 minutes using the DPM tool and completed approximately 1.0 symptom questionnaires per week (completion time 1-4 minutes). HCPs spent approximately 1-3 minutes a week using the tool per patient. Median time to HCP review for alerted versus non-alerted symptom questionnaires was 19.6 versus 21.5 hours. Most patients and HCPs felt that the DPM tool covered/mostly covered symptoms experienced (71% and 75%), was educational (65% and 92%), and improved patient-HCP conversations (70% and 83%) and cancer care (51% and 71%).

Conclusion

The DPM tool demonstrated positive adoption, adherence, and user experience for patients with lung/breast cancer, suggesting that DPM tools may benefit clinical cancer care.

Keywords: digital patient monitoring, patient-reported outcomes, lung cancer, breast cancer, symptom monitoring, eHealth

Digital patient monitoring tools can facilitate early symptom monitoring and management for cancer through systematic symptom reporting; however, low adherence can be a challenge. This study assessed patient and healthcare professional use of such tools in routine clinical practice.

Implications for Practice.

Adherence to digital health solutions over time is a challenge. We conducted a real-world study to assess patient adoption and adherence, and patient and healthcare professional (HCP) user experience of digital patient monitoring (DPM) for patients with lung/breast cancer in routine clinical practice. Our results showed that patient adoption of the DPM tool and adherence to weekly symptom reporting was high, and that most patients and HCPs had a positive user and care impact experience. This suggests that our DPM tool may facilitate symptom detection in outpatient clinics and improve early management and clinical cancer care.

Introduction

Poorly controlled disease- and treatment-related symptoms can impact negatively on clinical outcomes and quality of life (QoL) in patients with cancer1-3; eg, nausea and vomiting, the most frequently reported symptoms from chemotherapy, can significantly affect patients’ daily lives and consequently can lead to treatment discontinuation.4,5 Early symptom management can improve QoL, depression, mood, and overall survival versus standard care.6,7 However, patients typically only report symptoms during scheduled clinic visits. This may affect accuracy and details of reporting due to recall bias and difficulties in memorizing symptoms, challenges in the healthcare professional (HCP)-patient relationship, and the patient’s emotional state.8-10 In addition, the rising incidence and prevalence of cancer coupled with shortages of HCPs and longer intervals between hospital visits, potentially leading to reduced/less frequent HCP-patient contact time, may result in fewer symptoms being reported.11-14

Digital patient monitoring (DPM; remote patient monitoring) tools that enable patients with cancer to self-report disease-/treatment-related symptoms and QoL in a structured way, alert HCPs about critical symptoms, communicate directly with HCPs, and access self-management and support materials, have been investigated in clinical trials and introduced into clinical practice.15,16 The broad introduction of DPM tools into practice across different cancer indications and treatment lines is now recommended in the ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline.17 Properly implemented, these types of DPM tools can support improved patient-centered care by enabling higher congruence between symptoms being reported and addressed during clinic visits.18 DPM tools have also been shown to improve overall survival, QoL, treatment duration, and psychosocial outcomes, and to reduce symptom burden, including rates of severe and/or serious adverse events (AEs), the need for dose changes, and healthcare resource utilization by reducing emergency room visits and hospitalizations.19-36 Furthermore, some reports have suggested that they could facilitate risk prediction for future AEs.37-39

Studies of eHealth tools have shown challenges from low adherence over time.40 For DPM tools to be successfully integrated into practice and used in evidence generation, it is important to understand HCP and patient adoption, adherence, and user experience. We describe results from a real-world evidence study designed to assess adoption, adherence, and user experience of a DPM tool with tailored content for patients with lung/breast cancer in routine clinical practice. The content was tailored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd (Basel, Switzerland) based on learnings from a previous pilot study, and hosted on the Kaiku Health (Helsinki, Finland) DPM platform.27 Selected clinics were provided with access to the Kaiku Health DPM platform, which is a Class IIa active medical device both under the Medical Devices Directive according to Rule 10 (current at time of writing) and under the Medical Devices Regulation according to Rule 11.41,42 Patient access to the DPM tool was through their own devices (eg, laptops, PCs, smartphones, or tablets), either via a browser or via an app on Apple iOS or Android devices. HCPs (providers from routine practice) accessed the tool with the appropriate hospital devices used in their routine work. Patients could use the tool to report their health and wellbeing using predefined disease- and treatment-specific symptom/health-related QoL (HRQoL) questionnaires in DPM modules; view a dashboard of reported symptoms; receive reminders, notifications, and instructions related to reporting of predefined metrics; access patient materials such as self-management support instructions for selected mild/moderate symptoms43-46; and send messages and attachments to their care team. Relevant symptoms for the symptom questionnaires were selected based on the drug’s/drug class’s AE profile of the disease’s symptoms. The selection was refined in a discussion process with physicians, nurses, and patient groups. Symptoms covered by the DPM tool are listed in Supplementary Table S1. HCPs could use the tool to assign patients to predefined and individualized modules; receive, input, and view individual patient symptom reports; access an automated triage view of incoming symptom reports; and send messages and attachments to patients.

Methods

Recruitment and Participants

HCPs and patients were recruited from 10 clinics across Estonia, Finland, Greece, Norway, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden between March 2021 and June 2022. Eligibility criteria are shown in the Supplementary Materials.

The DPM Tool

Patients were prompted weekly to complete a symptom questionnaire in the DPM tool or could report their symptoms on an ad hoc basis. HCPs received daily digest emails about new patient reports; if a patient reported a new grade 3 symptom or ≥2-grade change in any symptom, an additional email notification was sent within 15 minutes of the patient’s report. Notifications of symptom reports were sent to HCPs in order to prioritize review and management, based on a composite grading approach.47 It was recommended to assign an HCP per site to monitor the dashboard daily on workdays. Patients and HCPs used the DPM tool for up to 15 months for symptom reporting and management; HRQoL data were collected up to week 18 (based on median duration of first-line cancer immunotherapy treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer/first-line HER2-targeted treatment in advanced breast cancer).

Data Collection and Analysis

The coprimary endpoints were patient adoption of the DPM tool (percentage of patients who accepted the invitation from their HCP to use the tool) and adherence to weekly symptom self-reporting in weeks 1-6. Patient adoption was considered positive if ≥60%, based on previous studies.36,48-52 Data on the number of patients adopting DPM were extracted from the DPM tool. HCPs completed a questionnaire for every patient who was offered the tool but declined. Adherence was considered positive if ≥70% patients (based on previous studies48,50-53) logged in to the tool weekly in weeks 1-6 of use. Data were collected from the tool, and patients who dropped out of the study for reasons unrelated to the tool or who did not complete a symptom questionnaire for >4 weeks were excluded from the analysis. Other collected adherence data per patient were adherence over complete use time; duration of use in weeks; time spent using the tool, completing the symptom questionnaire, and using self-management or educational materials per week; number of logins, questionnaires completed, and messages between HCPs and patients per week; and time spent by HCPs on the tool per patient per week.

Secondary endpoints included perceived DPM tool user experience, clinical impact, patient communication and self-efficacy, and HRQoL. HCP and patient user experience were assessed via tool experience questionnaires at week 6. A net promoter score (NPS) >11 was considered a positive user experience for HCPs and patients, based on the pilot study.27 Clinical impact in terms of how the DPM tool helped HCPs and patients to become better informed, have better conversations, and improve care, as well as the estimated symptom coverage of the tool, was measured using an HCP care impact questionnaire and patient experience questionnaire at week 6.

Data on patient and HCP DPM user characteristics were collected using questionnaires at week 0.

Methods for collecting and analyzing symptom alert and HRQoL data are shown in the Supplementary Materials.

Ethical Considerations

This research was conducted in full conformance with the International Society of Pharmacoepidemiology Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practice and the laws and regulations of the country in which the research was conducted. Depending on local regulations, the research plan and relevant supporting information were approved by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee at the participating site. Patient data were anonymized. All participants provided written informed electronic consent upon logging in to the DPM tool for the first time.

Results

Patient Adoption of the DPM Tool and Adherence to Weekly Symptom Reporting

At data cutoff (June 9, 2022), 153 patients were enrolled (mean: 15 per clinic) and had provided data for up to 15 months. Eighty-nine patients used Roche-created DPM modules, with the remaining 64 using generic Kaiku-created modules. The DPM tool was adopted by 85% of patients. Mean patient adherence to weekly symptom reporting in the first 6 weeks was 76%; in subsequent 6-weekly intervals, mean adherence ranged between 77% and 81% (Fig. 1). Both adoption and adherence were above the threshold for positive endpoints (60% and 70%, respectively); therefore, the study met its coprimary endpoints.

Figure 1.

Patient adherence to symptom self-reporting over time. Patient numbers (n) represent the number of patients who were expected to complete a symptom questionnaire in the respective study week.

Characteristics of Questionnaire Respondents

Of the 153 patients enrolled, 146 responded to a questionnaire regarding patient characteristics; 96 (66%) had stage IV cancer. The proportion with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0, 1, 2, and 3 was 39% (n = 57), 51% (n = 75), 8% (n = 11), and 2% (n = 3), respectively.

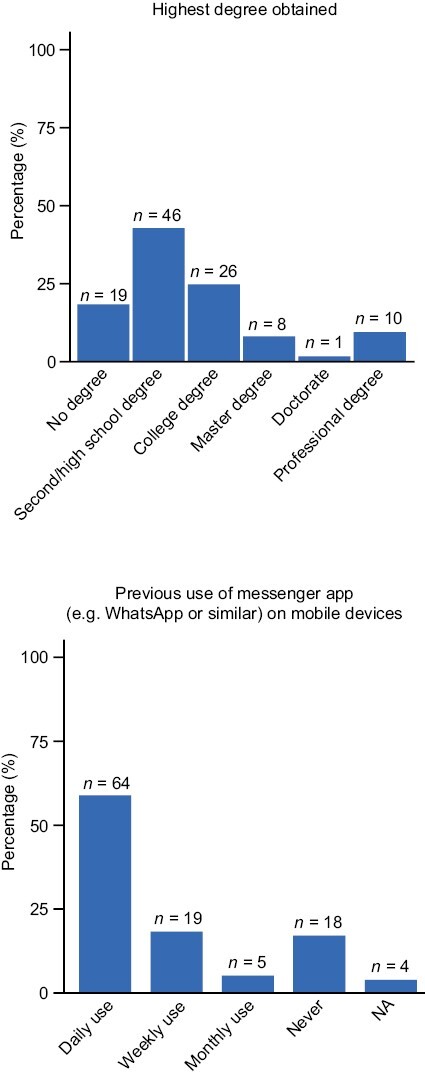

A total of 110 patients completed the DPM tool experience questionnaire at week 6. Of these respondents, 61 (55%) were male, and 91 (83%) had at least a secondary/high school degree (Fig. 2). Most patients (68 [62%]) were 60 years of age or over; 26 (24%) were 50-59, 11 (10%) were 40-49, and 5 (5%) were 30-39. Most of the patient users (106 [96%]) owned a tablet/mobile phone with internet connection, with 64 (58%) and 19 (17%) using messenger apps (eg, WhatsApp or similar) daily and weekly, respectively (Fig. 2), and 43 (39%) having used a similar DPM tool previously.

Figure 2.

Patient education and previous messenger app usage. Abbreviation: NA: not applicable.

Of the 70 HCPs enrolled, 30 completed the HCP characteristics and onboarding experience questionnaire at week 0. Eleven (37%) were between 40 and 49 years of age, 9 (30%) were <40, and 10 (33%) were ≥50; 8 (27%) had previous experience with DPM tools. Sixty-seven percent of HCPs indicated that a physician/nurse had been assigned to monitor the dashboard on a daily basis. In 60% of these cases, it was a nurse (Supplementary Fig. S1).

User Experience

In addition to the 110 patients who provided data on user experience, 24 HCPs also completed a DPM tool experience questionnaire at week 6. Most patients and HCPs were satisfied/very satisfied with the tool, with customer satisfaction (CSAT) scores of 76% and 83%, respectively (Fig. 3). They also found the tool easy/very easy to use (customer effort scores [CES] were 82% and 79%, respectively) (Fig. 3). Both CSAT and CES scores were higher for doctors versus nurses (CSAT: 100% vs. 75%; CES: 83% vs. 78%). NPS scores for patients and HCPs were positive (22 and 33, respectively) (Fig. 3). Further investigation of NPS scores also showed a difference between nurses and doctors (19 vs. 62, respectively).

Figure 3.

Patient and HCP user experience. Abbreviations: CES: customer effort score; CSAT: customer satisfaction score; HCP: healthcare professional; NPS: net promoter score.

HCPs received ~1 hour of online eTraining for the DPM tool. Most HCPs agreed/strongly agreed that this was well structured and easy to follow (n = 28/30 [93%]), that they were satisfied with the overall onboarding experience (29/30 [97%]), that they felt confident about using the tool (24/30 [80%]), and that they knew where to find instructions and/or whom to contact for help/advice on using the tool (28/30 [93%]).

Clinical Practice Use

Patients spent a median of 10 minutes (range 5-33) per week logged in to the DPM tool across all modules. The median number of symptom questionnaires completed by patients per module was ~1.0 per week, each of which took a median of 1-4 minutes to complete. The median number of symptom questionnaires completed per week was similar across ECOG performance status and patient age groups. The median time to complete symptom questionnaires was higher in the group of patients ≥60 years versus 50-59 years, and in those with an ECOG performance status of 1 or 2 versus 0.

HCPs spent an average of 1-3 minutes per patient on the tool each week. For most clinics, nurses were the primary users of the DPM tool. The median time to HCP review for non-alerted symptom questionnaires was 21.5 hours; alerted symptom questionnaires, which accounted for ~25% of all questionnaires, were reviewed by HCPs in a median of 19.6 hours (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Perceived Clinical Impact

After 6 weeks of use, the majority of patients and HCPs felt that using the DPM tool helped them to be better informed about the disease and patient care (n = 71/110 [65%] and 22/24 [92%], respectively); improved conversations between patients and their care team (77/110 [70%] and 20/24 [83%]); and improved cancer care (56/110 [51%] and 17/24 [71%]) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Perceived clinical impact of the DPM tool by HCPs and patients after 6 weeks of use. Abbreviations: DPM: digital patient monitoring; HCP: healthcare professional.

Overall, 75% of HCPs and 71% of patients considered the symptom questionnaires to fully/mostly cover the symptoms experienced during the first 6 weeks of DPM use. A total of 47% of patients who reported their symptoms were not fully covered contacted their HCP team about such symptoms. HCPs mostly learned about symptoms not covered by the questionnaire via phone calls, during clinic visits, or via messages in the DPM tool.

Impact on HRQoL

Exploratory HRQoL analyses of data from 45 patients who answered the questionnaire at baseline and weeks 6, 12, and 18 using the Wilcoxon signed rank test for non-normally distributed data demonstrated that the HRQoL summary score was significantly improved at weeks 12 (P = .046) and 18 (P = .042) versus baseline. They also showed that the HRQoL global health status and symptom control score were significantly improved at week 12 (P = .01 and P = .025, respectively) versus baseline, but not at week 6 (P = .52 and P = .23, respectively) or week 18 (P = .16 and P = .079, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 3). Lower numbers for individual symptom burden were reported over time, but this was mostly not statistically significant due to limited data.

Discussion

In this real-world study of a DPM tool for patients with lung/breast cancer, the coprimary endpoints of patient adoption of the DPM tool and adherence to symptom self-reporting at week 6 were met, confirming that the tool is an acceptable and desirable solution for patients. Our DPM tool’s adoption rate observed in this study (85%) is slightly higher than that observed in previous publications for similar DPM tools, where the reported adoption rates were in the range of 60%-75%.36,48-52 The observed adherence in this study (76%-81%), however, is within the range of weekly adherence rates from previous studies of the Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) reporting of similar DPM tools (70%-85%).48,50-53 One consideration that could potentially affect adherence is the frequency of the symptom questionnaires. In our study, patients were prompted to complete a questionnaire weekly. Changing the frequency of prompts to once every other week/once per month could improve adherence in patients who do not want to answer the same questions every week; however, this may increase the risk that some symptoms might not be reported.8 In addition, the DPM tool assessed in this study included modules that were disease- and treatment-specific. Treatment-specific DPM tools (eg, those for immunotherapy/targeted therapy for multiple cancer types) may be considered more useful than disease-specific DPM tools (eg, those only for breast cancer) in clinical practice as they allow use of the tool across different cancer sites. This could also further improve adoption and adherence of DPM tools.

The user experience of the DPM tool was positive for both patients and HCPs, which was confirmed by the high CSAT, CES, and NPS scores. As the time point of questionnaire administration was the same for all patients (after 6 weeks of DMP tool use) and the questions focused on the satisfaction with the DPM service/tool, we do not expect an impact from the start of drug treatment. However, nurses had consistently lower scores than doctors, which could be indicative of the increased workload for nurses caring for patients using the DPM tool, as nurses were the primary users of the tool at most of the participating sites. Alternatively, the poor integration between the DPM tool and electronic health records may have caused lower scores from nurses who are responsible for maintaining patient records. On the other hand, doctors may have been more committed to using the DPM tool, with more awareness of the difficulties of patient-doctor communication in standard clinical practice.

Time spent using the tool for patients and for HCPs per patient each week was low, as was the time required to complete a symptom questionnaire. The time measurements obtained in this study suggest that the burden on patients and HCPs of using the DPM tool is low. In addition, there was no significant difference between the numbers of questionnaires completed by patients across all ECOG performance status and age groups, which indicates that the DPM tool is suitable for a broad patient population, although the time to complete a symptom questionnaire was slightly higher in older patients and patients with worse performance status.

The small time difference between alerted and non-alerted symptom reviews by HCPs (21.5 vs. 19.6 hours) is likely due to the fact that most clinics performed triage each morning and that patients with new symptoms would often contact the clinic themselves rather than waiting for HCP review of the DPM alerts, per the usual care construct. Consistent with previous reports,54 this suggests that alerting critical symptoms to HCPs versus patients does not impact the utility of a DPM tool.

Most patients and HCPs agreed that the DPM tool had a positive clinical impact by helping them to be better informed about the disease and care, to have better conversations between patients and their care team, and to improve cancer care. Exploratory analyses also demonstrated a benefit in terms of HRQoL, with the DPM tool resulting in significantly improved HRQoL summary scores at weeks 12 and 18 versus baseline, and significantly improved HRQoL global health status and symptom control score at week 12 versus baseline. Improvements in HRQoL scores with DPM use in this study are consistent with other studies demonstrating an increase in QoL in patients using DPM tools based on the EQ-5D-5L, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT), or the QLQ-C30 questionnaire instruments, versus no DPM tool use.19,21,23,55-57 To better describe the impact of our DPM tool on HRQoL over time, we have recently begun a clinical trial in which patients will be randomized into a DPM arm and a non-DPM “control” arm.58

The analyses presented here have several strengths. Being a real-world study, the data collected are reflective of adoption, adherence, and user experience in routine clinical practice in populations of patients with different cancer diagnoses and treatments. In addition, the usage data were collected from the tool’s analytics wherever possible, both to reduce the number of questions to be answered by HCPs and patients and to circumvent perception biases.

Study limitations include the possibility of incomplete data collection via questionnaires with a likely decrease in questionnaire respondents and completeness over time as shown in similar studies,53,55 due to the nature of the project setting and patient population and the potential bias on adoption rates caused by preselection of patients by HCPs. Furthermore, our study lacked a control group and included low sample sizes, which in particular limits the interpretation of HRQoL results (<1/3 patients completed HRQoL questionnaires at all timepoints). Finally, our study did not formally assess the impact of the DPM modules on patient outcomes, eg, overall survival, progression-free survival, or AEs; however, this will be the focus of a future randomized controlled trial (NCT05694013) by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, which is currently being conducted.

Conclusion

Overall, our results demonstrated positive adoption, adherence, and user experience for patients with lung or breast cancer using a DPM tool alongside locally approved and reimbursed drugs. These results suggest that adoption of DPM tools into routine clinical practice is both feasible and can have a positive effect on clinical cancer care.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at The Oncologist online.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland. Research support in the form of third-party medical writing assistance for this manuscript, furnished by Katie Wilson, BSc, of Health Interactions, was provided by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland.

Contributor Information

Edurne Arriola, Medical Oncology Department, Hospital del Mar, Barcelona, Spain.

Jana Jaal, Department of Hematology and Oncology, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia.

Anne Edvardsen, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Akershus University Hospital, Lørenskog, Norway.

Maria Silvoniemi, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Turku University Hospital, Turku, Finland.

António Araújo, Department of Medical Oncology, Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Santo António, Porto, Portugal; UMIB - Unit for Multidisciplinary Research in Biomedicine, ICBAS - School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal.

Anders Vikström, Pulmonary Clinic, University Hospital, Linköping, Sweden.

Eleni Zairi, Medical Oncology Department, St. Luke’s Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece.

Mari Carmen Rodriguez-Mues, Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Clínico Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Marco Roccato, Program Manager Office (PMO), Kaiku Health, Helsinki, Finland.

Sophie Schneider, Pharma Personalised Healthcare, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland.

Johannes Ammann, Global Product Development Medical Affairs, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland.

Funding

This study was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Conflict of Interest

All authors received research support in the form of third-party medical writing assistance from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Edurne Arriola reported consulting/advisory relationships with Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim, and honoraria from Roche, MSD, BMS, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Guardant Health, and Takeda. Jana Jaal reported research funding from Roche, and consulting/advisory relationships with MSD and AstraZeneca. Anne Edvardsen reported research funding from Roche. Maria Silvoniemi reported a consulting/advisory relationship with Roche. Antonio Araujo reported research funding from Roche. Anders Vikström reported consulting/advisory relationships with Merck, BMS, MSD, and Pfizer, and honoraria from MSD, AstraZeneca, Roche, and BMS. Eleni Zairi and Mari Carmen Rodriguez-Mues: Authors declare no other competing interests. Marco Roccato is an employee of Kaiku Health. Sophie Schneider is an employee of F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG, with ownership interests. Johannes Ammann is an employee of F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG, with ownership interests.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: M.R., J.A. Provision of study material or patients: E.A., J.J., A.E., M.S., A.A., A.V., E.Z., M.C.R.-M. Collection and/or assembly of data: E.A., J.J., A.E., M.S., A.A., A.V., E.Z., M.C.R.-M., S.S. Data analysis and interpretation: E.A., A.E., M.S., M.R., S.S., J.A. Manuscript writing and final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Data Availability

For up-to-date details on Roche’s Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see here: https://go.roche.com/data_sharing. Pseudonymized, individual patient level data are made available to qualified researchers by request from the corresponding author (johannes.ammann@roche.com). Anonymized records for individual patients across more than one data source external to Roche cannot, and should not, be linked due to a potential increase in risk of patient reidentification.

References

- 1. Kim J-EE, Dodd MJ, Aouizerat BE, et al. A review of the prevalence and impact of multiple symptoms in oncology patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(4):715-736. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cleeland CS. Cancer-related symptoms. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2000;10(3):175-190. 10.1053/srao.2000.6590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(17):1714-1768. 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hilarius DL, Kloeg PH, van der Wall E, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in daily clinical practice: a community hospital-based study. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(1):107-117. 10.1007/s00520-010-1073-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van Laar ES, Desai JM, Jatoi A.. Professional educational needs for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): multinational survey results from 2388 health care providers. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(1):151-157. 10.1007/s00520-014-2325-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742. 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):834-841. 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stull DE, Kline Leidy N, Parasuraman B, et al. Optimal recall periods for patient-reported outcomes: challenges and potential solutions. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(4):929-942. 10.1185/03007990902774765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sneeuw KC, Aaronson NK, Sprangers MA, et al. Comparison of patient and proxy EORTC QLQ-C30 ratings in assessing the quality of life of cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(7):617-631. 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00040-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gouveia L, Lelorain S, Brédart A, et al. Oncologists’ perception of depressive symptoms in patients with advanced cancer: accuracy and relational correlates. BMC Psychol. 2015;3(1):6. 10.1186/s40359-015-0063-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mendoza TR, Dueck AC, Bennett AV, et al. Evaluation of different recall periods for the US National Cancer Institute’s PRO-CTCAE. Clin Trials. 2017;14(3):255-263. 10.1177/1740774517698645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Society of Clinical Oncology. The state of cancer care in America, 2016: a report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(4):339-385. 10.1200/JOP.2015.010462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Limb M. Shortages of radiology and oncology staff putting cancer patients at risk, college warns. BMJ. 2022;377:o1430. 10.1136/bmj.o1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Cancer Over Time. 2023. Accessed March 2023. https://gco.iarc.fr/overtime/en

- 15. Warrington L, Absolom K, Conner M, et al. Electronic systems for patients to report and manage side effects of cancer treatment: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(1):e10875. 10.2196/10875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aapro M, Bossi P, Dasari A, et al. Digital health for optimal supportive care in oncology: benefits, limits, and future perspectives. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(10):4589-4612. 10.1007/s00520-020-05539-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Di Maio M, Basch E, Denis F, et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee. The role of patient-reported outcome measures in the continuum of cancer clinical care: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(9):878-892. 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ruland CM, White T, Stevens M, et al. Effects of a computerized system to support shared decision making in symptom management of cancer patients: preliminary results. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(6):573-579. 10.1197/jamia.M1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565. 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(2):197-198. 10.1001/jama.2017.7156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Denis F, Lethrosne C, Pourel N, et al. Randomized trial comparing a web-mediated follow-up with routine surveillance in lung cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(9):djx029. 10.1093/jnci/djx029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Denis F, Basch E, Septans AL, et al. Two-year survival comparing web-based symptom monitoring vs routine surveillance following treatment for lung cancer. JAMA. 2019;321(3):306-307. 10.1001/jama.2018.18085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fjell M, Langius-Eklöf A, Nilsson M, et al. Reduced symptom burden with the support of an interactive app during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer - a randomized controlled trial. Breast. 2020;51:85-93. 10.1016/j.breast.2020.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kolb NA, Smith AG, Singleton JR, et al. Chemotherapy-related neuropathic symptom management: a randomized trial of an automated symptom-monitoring system paired with nurse practitioner follow-up. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1607-1615. 10.1007/s00520-017-3970-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mir O, Ferrua M, Fourcade A, et al. Intervention combining nurse navigators (NNs) and a mobile application versus standard of care (SOC) in cancer patients (pts) treated with oral anticancer agents (OAA): results of CapRI, a single-center, randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15_suppl):2000-2000. 10.1200/jco.2020.38.15_suppl.200032315272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Degenhardt T, Harbeck N, Fasching PA, et al. Documentation patterns and impact on observed side effects of the CANKADO ehealth application: an exploratory analysis of the PreCycle trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15_suppl):2083-2083. 10.1200/jco.2020.38.15_suppl.2083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schmalz O, Jacob C, Ammann J, et al. Digital monitoring and management of patients with advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer treated with cancer immunotherapy and its impact on quality of clinical care: interview and survey study among health care professionals and patients. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(12):e18655. 10.2196/18655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fann JR, Hong F, Halpenny B, Blonquist TM, Berry DL.. Psychosocial outcomes of an electronic self-report assessment and self-care intervention for patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2017;26(11):1866-1871. 10.1002/pon.4250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Børøsund E, Cvancarova M, Moore SM, et al. Comparing effects in regular practice of e-communication and web-based self-management support among breast cancer patients: preliminary results from a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(12):e295. 10.2196/jmir.3348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rasschaert M, Vulsteke C, De Keersmaeker S, et al. AMTRA: a multicentered experience of a web-based monitoring and tailored toxicity management system for cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(2):859-867. 10.1007/s00520-020-05550-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hough S, McDevitt R, Nachar VR, et al. Chemotherapy remote care monitoring program: integration of SMS text patient-reported outcomes in the electronic health record and pharmacist intervention for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17(9):e1303-e1310. 10.1200/OP.20.00639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Velikova G, Absolom K, Warrington L, et al. Phase III randomized controlled trial of eRAPID (electronic patient self-Reporting of Adverse-events: Patient Information and advice)—an eHealth intervention during chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15_suppl):7002-7002. 10.1200/jco.2020.38.15_suppl.7002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mooney K, Iacob E, Wilson CM, et al. Randomized trial of remote cancer symptom monitoring during COVID-19: impact on symptoms, QoL, and unplanned health care utilization. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15_suppl):12000-12000. 10.1200/jco.2021.39.15_suppl.12000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berry DL, Hong F, Halpenny B, et al. Electronic self-report assessment for cancer and self-care support: results of a multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(3):199-205. 10.1200/JCO.2013.48.6662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maguire R, McCann L, Kotronoulas G, et al. Real time remote symptom monitoring during chemotherapy for cancer: European multicentre randomised controlled trial (eSMART). BMJ. 2021;374:n1647. 10.1136/bmj.n1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mooney KH, Beck SL, Wong B, et al. Automated home monitoring and management of patient-reported symptoms during chemotherapy: results of the symptom care at home RCT. Cancer Med. 2017;6(3):537-546. 10.1002/cam4.1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Iivanainen S, Ekström J, Kataja VV, et al. Electronic patient-reported outcomes (ePROs) and machine learning (ML) in predicting the presence and onset of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapies. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15_suppl):e14058. 10.1200/jco.2020.38.15_suppl.e14058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Iivanainen SME, Ekstrom J, Kataja V, Virtanen H, Koivunen J.. Predicting the onset of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) in immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapies using a machine learning (ML) model trained with electronic patient-reported outcomes (ePROs) and lab measurements. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(4_suppl):S1057. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.1488 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Iivanainen SME, Ekstrom J, Kataja V, et al. A combination model of electronic patient-reported outcomes (ePROs) and lab measurements in prediction of immune related adverse events (irAEs) and treatment response of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapies. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(4_suppl):S1068. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.1523 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pratap A, Neto EC, Snyder P, et al. Indicators of retention in remote digital health studies: a cross-study evaluation of 100,000 participants. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:21. 10.1038/s41746-020-0224-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. EUR-Lex. Council directive of 20 June 1990 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to active implantable medical devices. 2020. Accessed March 2023. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:01990L0385-20071011&from=EN

- 42. EUR-Lex. Regulation (EU) 2020/561 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2020 amending Regulation (EU) 2017/745 on medical devices, as regards the dates of application of certain of its provisions. 2020. Accessed March 2023. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32020R0561&from=EN

- 43. Bana M, Ribi K, Kropf-Staub S, et al. Development and implementation strategies of a nurse-led symptom self-management program in outpatient cancer centres: the Symptom Navi© Programme. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;44:101714. 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.101714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bana M, Ribi K, Kropf-Staub S, et al. Implementation of the Symptom Navi © Programme for cancer patients in the Swiss outpatient setting: a study protocol for a cluster randomised pilot study (Symptom Navi© Pilot Study). BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e027942. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kropf-Staub S, Sailer Schramm M, Preusse-Bleuer B, et al. Flyer to improve self-management of symptoms for patients with cancer – evaluation of feasibility and comprehensibility of the Symptom Navi. Pflege. 2017;30(3):151-160. 10.1024/1012-5302/a000518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bana M, Ribi K, Peters S, et al. Pilot testing of a nurse-led basic symptom self-management support for patients receiving first-line systemic outpatient anticancer treatment: a cluster-randomized study (Symptom Navi Pilot Study). Cancer Nurs. 2021;44(6):E687-E702. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Basch E, Becker C, Rogak LJ, et al. Composite grading algorithm for the National Cancer Institute’s Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). Clin Trials. 2021;18(1):104-114. 10.1177/1740774520975120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ruland CM, Andersen T, Jeneson A, et al. Effects of an internet support system to assist cancer patients in reducing symptom distress: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(1):6-17. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31824d90d4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tran C, Dicker A, Leiby B, et al. Utilizing digital health to collect electronic patient-reported outcomes in prostate cancer: single-arm pilot trial. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(3):e12689. 10.2196/12689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yount SE, Rothrock N, Bass M, et al. A randomized trial of weekly symptom telemonitoring in advanced lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(6):973-989. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Duman-Lubberding S, van Uden-Kraan CF, Jansen F, et al. Feasibility of an eHealth application “OncoKompas” to improve personalized survivorship cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(5):2163-2171. 10.1007/s00520-015-3004-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Melissant HC, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Lissenberg-Witte BI, et al. “Oncokompas,” a web-based self-management application to support patient activation and optimal supportive care: a feasibility study among breast cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(7):924-934. 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1438654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Denis F, Viger L, Charron A, et al. Detection of lung cancer relapse using self-reported symptoms transmitted via an internet web-application: pilot study of the sentinel follow-up. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(6):1467-1473. 10.1007/s00520-013-2111-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Billingy NE, Tromp V, Becker A, et al. Patient-reported symptom monitoring improves health-related quality of life in lung cancer patients: the SYMPRO-Lung trial. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(7_suppl):S1352. 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.07.311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Iivanainen S, Alanko T, Peltola K, et al. ePROs in the follow-up of cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a retrospective study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145(3):765-774. 10.1007/s00432-018-02835-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pfeifer MP, Keeney C, Bumpous J, et al. Impact of a telehealth intervention on quality of life and symptom distress in patients with head and neck cancer. J Community Support Oncol. 2015;13(1):14-21. 10.12788/jcso.0101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Basch E, Schrag D, Henson S, et al. Effect of electronic symptom monitoring on patient-reported outcomes among patients with metastatic cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;327(24):2413-2422. 10.1001/jama.2022.9265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Iivanainen S, Baird AM, Balas B, et al. Assessing the impact of digital patient monitoring on health outcomes and healthcare resource usage in addition to the feasibility of its combination with at-home treatment, in participants receiving systemic anticancer treatment in clinical practice: protocol for an interventional, open-label, multicountry platform study (ORIGAMA). BMJ Open. 2023;13(4):e063242. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

For up-to-date details on Roche’s Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see here: https://go.roche.com/data_sharing. Pseudonymized, individual patient level data are made available to qualified researchers by request from the corresponding author (johannes.ammann@roche.com). Anonymized records for individual patients across more than one data source external to Roche cannot, and should not, be linked due to a potential increase in risk of patient reidentification.