Abstract

Aim:

Abdominal breathing recently has demonstrated an important role in managing symptoms of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD), improving quality of life, medication adherence, and sleep quality. This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of abdominal breathing on sleep and quality of life in patients with non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux.

Subject and methods:

A Quasi-experimental design was used. A purposive sample of 100 patients was selected from the medical outpatient clinics of Menoufia University Hospital and the outpatient clinics of the National Liver Institute in Menoufia Governorate, Egypt. A Structured interview questionnaire was used to collect data on patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, belly breathing exercise performance and self-reported compliance, GERD symptoms severity and frequency, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, and GERD Health-Related Quality of Life.

Results:

The frequency of GERD symptoms decreased from 26.64 pre-intervention to 17.61 and 9.58, respectively, at two- and four-months post-intervention. Antacid consumption among patients taking it 7 days/week was reduced from 34% pre-intervention to 2% and 0% post-intervention by two and four months, respectively. Good sleepers were 24% pre-intervention then increased to 62% and 90% post-intervention by 2 and 4 months, respectively. Regarding GERD related quality of life, only 1% was satisfied pre-intervention, which increased to 32% and 72% post-intervention by 2 and 4 months, respectively.

Conclusion:

Abdominal breathing offers better therapeutic improvements in all patients’ outcomes such as reduced severity and frequency of GERD symptoms, reduced antacid consumption, increased sleep quality, and increased satisfaction with life quality. Healthcare professionals are encouraged to incorporate abdominal breathing into treatment protocols for patients with non-erosive GERD.

Keywords: Abdominal breathing, non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux, GERD, sleep and life quality

Introduction

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) indicates backflow of stomach and duodenal contents into the esophagus, resulting in gastrointestinal discomfort with esophageal mucosa damage. Causes include an imbalance between factors harming stomach lining as gastric acidity, volume and duodenal contents, and factors defending the esophagus as anti-reflux barriers, esophageal acid clearance, and tissue resistance. 1

Overweight, pregnancy, drinking alcohol, smoking, and Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug (NSAID) are the main risk factors. Although the disease-related provoking symptoms themselves are rarely life-threatening, they devastate all health domains as physical, mental, social and psychological as a result of pain, heartburn, regurgitation, belching, persistent cough, hoarseness, teeth erosion, emotional distress, eating and drinking problems, and bad general overall health. Additionally, nocturnal symptoms are significant contributors to a variety of sleep disorders as poor sleep quality, sleep apnea, lack of sleep, insomnia, snoring, and nightmares. Therefore, GERD is a significant strain on the economic and healthcare systems due to increased work absenteeism, decreased work productivity, higher healthcare consumption, and greater consumption of healthcare resources. 2

GERD symptoms are usually identified, treated, and relieved through Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs). Calculating antacids intake or quitting percent of intake is a measure of condition severity. Although pharmaceutical drugs may reduce the disease symptoms, they also run the risk of those symptoms’ recurrence. Long-term maintenance also may lead to negative side effects such as myocardial infarction, lower bone mineral density, and bone fractures. Surgery, which is advised for serious cases, can considerably lower the likelihood of recurrence, but it is still troubling to wonder about its consequences of bleeding, dyspepsia or even death. 3

Traditionally, lifestyle modification is a non-pharmacological method to overcome this disease through changing diet components, abstaining from alcohol, quitting smoking, decreasing weight, stop eating at least 3 hours before bedtime, elevating bed head, using a different position in bed instead of the right decubitus, turning off the lights when getting into bed, minimizing the awake time before falling asleep, and not interrupting sleep time. Recently, abdominal breathing exercises have been shown to be the more effective technique in managing GERD-related symptoms, enhancing quality of life, medication adherence, and sleep patterns among non-surgical and non-pharmacological modalities. 4

The diaphragm is the primary inspiratory muscle, that contracts and relaxes in dome shape with respiration. Its capacity to elevate and expand the lower rib cage is usually compromised by GERD leading to pathological alterations resulting in a reduction of lower ribs’ transverse diameter during inspiration. Tension within the fascia can cause diaphragmatic dysfunctions with related biomechanical problems, which may affect various bodily functions and musculoskeletal regions. Therefore, abdominal breathing (manual diaphragm release and stretch) aims to release tension in a particular area of the diaphragm and attachments within and around the diaphragm. 5

Also, abdominal breathing increases the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathways in the parasympathetic nervous system, which mediate an antihyperalgesic action. It can strengthen the Crural Diaphragm (CD) tone, raise Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES) pressure, and enhance diaphragm motor function, all of which will increase the antireflux barrier effect and lessen reflux. Patients with GERD may find that deep inhalation exercises greatly reduce their sensations of stomach pain caused by esophageal hyperalgesia. 6

The Crural Diaphragm is a skeletal muscle that, like other striated muscles, can be strengthened by training. The overall objective is always to strengthen these muscles and improve their anti-reflux defenses. Exercises that focus on breathing have been demonstrated to strengthen the gastroesophageal junction. 7

Significance

Annually GERD symptoms are increasing by about 4%, comparable to the rise in obesity frequency. Weekly from 10% to 20% of adults in Western countries and nearly 5% of those in Asia have been diagnosed with GERD symptoms. The prevalence of GERD was reported to be as high as 20% in the Western world with a much lower rate in Asia. Each year, it accounts for more than 5.6 million doctor visits. 8

Conceptual framework

This study is based on Orem’s concept, which emphasizes each person’s capacity for self-care. It is defined as activities practice, that individuals initiate and carry out on their own behalf to maintain life, health, and wellbeing. The model’s fundamental tenet is that people are capable of caring for themselves and taking charge of their health. 9

Orem et al.′s model emphasized that if patients are permitted to take care of themselves to the best of their abilities, they will holistically recover more quickly. The theory selection was based on how well it explained need determination, nursing system design, care delivery planning, initiating, conducting, and managing aiding actions. The current study’s use of this theory allows patients understanding abdominal breathing advantages in relation to GERD as well as how to perform it and also helping in manage and provide self-care in order to maintain and enhance patients’ health-related quality of life. 10

According to Orem, patients will use the planned exercises to resolve current manifestations, prevent complications, enhance sleep quality, and improve all aspects of their lives. The Orem model will be used by the researchers to examine the debilitation process, which began with disease implications and symptoms, designing and performing breathing exercises for the patient (self-care), putting a management plan into place, and finally, evaluating the patient’s outcomes improvement.

Purpose of the study: To evaluate the abdominal breathing effectiveness on sleep and life quality among patients with non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux.

Hypotheses

Patients who apply abdominal breathing exercise will exhibit more identification of GERD-triggering factors.

Patients who apply abdominal breathing exercise will exhibit a reduction of GERD symptoms severity and frequencies compared to pre-application.

Patients who apply abdominal breathing exercise will exhibit reduced antacid consumption compared to pre-application.

Patients who apply abdominal breathing exercise will exhibit improved sleep quality compared to pre-application.

Patients who apply abdominal breathing exercise will exhibit increased satisfaction with their health-related quality of life compared to pre-application.

Methods

Design: Quasi-experimental design.

Setting: Medical outpatient clinics of Menoufia University Hospital and the outpatient clinics of the National Liver Institute in Menoufia Governorate, Egypt.

Inclusion criteria: Male and female patients ≥18 years, meeting the diagnostic criteria of GERD (typical heartburn, acid regurgitation, which can be combined with atypical symptoms of chest pain, belching, or extra-esophageal symptoms as cough and asthma, should have been experienced for at least 6 months). The diagnosis was confirmed by endoscopy or a 24-h esophageal pH-value test. Patients treated by PPI or acid suppressant with symptoms recurrence.

Exclusion criteria: Contraindications of performance of physical exercise or handicap, having metabolic or endocrine disorders, patients with secondary GERD as (surgery, pregnancy, drugs as glucocorticoid), patients have serious chronic diseases as upper gastrointestinal ulcer, or hiatus dysfunction, follow weight reduction program (medications /diet) to prevent conflict with the current intervention.

Sampling: A purposive sampling.

Sample size: The calculated sample size was 109 as the target population with these inclusion and exclusion criteria was 150 patients, 95% level of confidence, 5% acceptable error, and 50% expected outcome. Only 100 (response rate = 91.74%) patients completed follow–up and their results were used in statistical analysis

Data collection tools

Five instruments were used to collect data.

Instrument (I): A structured interview questionnaire was developed by the researchers after an extensive recent literature review to assess patients’ socio-demographic data, patients’ knowledge about GERD-triggering factors, and the number of antacids consumed per week. It is divided into three parts:

Part one: Socio-demographic data: Include seven questions about age, sex, educational level, occupation, residence, associated chronic diseases, unprescribed NSAID consumption, and telephone number.

Part two: GERD-triggering factors assessment questionnaire: This includes 11 questions regarding tea and coffee intake, diet type, eating to bedtime hours, physical activity, tight-fitting clothing, triggering foods and drinks, eating smaller meals and slowing down, elevating bed head, smoked cigarettes /day, and Body Mass Index (BMI) measured in (kg/m2).

Part three: Days of antacid consumption/week: A question about the number of days of antacid consumption/week. The answer was divided into nothing/day all over the week, 1–3 days/ week, 4–6 days/week, and 7 days/ week.

Instrument (II): Abdominal breathing exercises performance checklist and self-reported compliance sheet: Developed by the researchers after an extensive recent related literature review 11 to evaluate patients’ performance and compliance with abdominal breathing exercises. It includes two parts:

Part one: Abdominal breathing exercises performance checklist: This Includes researchers’ demonstration and patient’s re-demonstration of planned exercise procedure steps. The researcher instructed patients to perform the following four steps:

Place one from both hands on the abdomen just below the ribs and the other hand on the chest. Patients can perform this while standing or lying with knees bent as it may be more comfortable.

Inhale deeply from the nose and allow the patient’s tummy to push their hands out as they inhale but keep the chest motionless.

Breathe out through pursed lips to force all air out of the lungs, feel the hand on the abdomen descend, and softly press on the area. Breathe out slowly.

Three to ten times, repeat these steps per day, allowing each breath to be deliberate.

Scoring system: It was comprised of a three-point Likert scale as follows; zero for not done or Fault, one for accurate incomplete performance, and two for accurate complete performance. The total score ranged from 0 to 8 score.

Part two: Self-reported compliance sheet: A question about patient’s compliance with abdominal breathing exercise.

Scoring system: It was comprised of a three-point Likert scale: Zero for not complying at all, one for complying to some extent, and two for completely complying with the learned exercise performance.

Instrument (III): GERD clinical symptoms severity and frequency assessment: Adopted from Velanovich (2007) to assess the severity and frequency of 16 GERD symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation, dysphagia, bad breath, nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain, dyspnea, sore throat, belching, chest pain, chronic cough, hoarseness, globus, tooth erosions, and bloating/ flatulence).

Scoring system: For symptoms severity, it was comprised of a four-point Likert scale: graded 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe. The total score was from 0 to 48. Then divided into (0–16) Mild, (17–33) moderate, and (34–48) severe symptoms. For symptoms frequency, it was comprised of a three-point Likert scale: graded 0 = absent, 1 = occasional (symptoms appear in ˂ 2 days /week), 2 = frequency (symptoms appear in 2–4 days /week), and 3 = very frequent (symptoms appear in >4 days / week). Mean and standard deviations of all items were obtained throughout the study phases.

Instrument (IV): Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI): An international measurement advanced by Buysse et al., as an effective tool to measure the quality and patterns of sleep in the older adult. It has seven subscales: sleep time. latency, disturbances, subjective sleep quality, the efficiency of habitual sleep, sleeping pills use, and the dysfunction of daytime over the last month. The score of sleep quality is obtained via summarizing the seven elements. 12

Scoring system: Each score ranged from zero to three points of which, “three” reflects the negative extreme on the Likert Scale. The total PSQI ranges from 0 (no trouble) to 3 (severe trouble). The worldwide score ranges from 0 to 21. A PSQI total score from (0–7) indicates good sleep quality; from (8–14) average sleep quality, and (15–21) indicates poor sleep quality.

Instrument (V): GERD Health-Related Quality of Life (GERD-HRQL) Scale: This was developed by Velanovich, and contains two parts, the first is heartburn which includes 10 questions and the second is regurgitation which includes six questions. Each question has a Likert scale from 0 to 5, with zero indicating no symptoms, 1 = noticeable but not bothersome, 2 = noticeable and bothersome but not every day, 3 = bothersome daily, 4 = bothersome and affects daily activities, and 5 = incapacitating to do daily activities. A final question about satisfaction level with current health-related quality of life. Its answer has a three-point scale, 2 for satisfied, 1 for neutral and zero for dissatisfied. 13

Scoring system: For the heartburn section, answers to the 10 questions were summed and the score ranged from 0 to 50 score. For the regurgitation section, answers to the six questions were summed up and the score ranged from 0 to 30. Finally, the mean and standard deviations of all items were obtained throughout the study phases.

Validity and reliability

Experts in the fields of medicine, surgery, and family and community health nursing evaluated each tool’s content validity. They were asked to assess the items’ clarity and completeness. The tool was modified to include suggestions. All changes that were suggested were carried out.

To determine the dependability of the created tools, test-retest was utilized. Cronbach’s alpha reliability was 0.94, according to instrument one’s dependability report. Instruments 2, 3, and 4 had coefficient alpha reliability of 0.92, and Instrument five had Cronbach’s alpha reliability of 0.94, all of which point to the tool’s generally acknowledged reliability.

Pilot study: Conducted on 10 patients to test the clarity and applicability of developed tools. The necessary modifications were made accordingly. Data obtained from those patients were not included in the final study.

Ethical considerations

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Formal approval was taken from the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing at Menoufia University. All ethical rules were considered, and patients were informed of their voluntary participation in the study and their liberty to reject. Their privacy and confidentiality were preserved. Patients were informed of the investigation’s purpose and signed an agreement to participate in the study.

Procedure

Patients who had agreed to participate in the study received a brief description of the study purpose from the researchers before any data were collected.

Between January 2023 and March 2023 (pre-assessment phase period), 1-2 days a week from 9 am to 12 pm, the study researchers were present at the gastroenterology and internal medicine clinics to collect the study participants and involve them in belly breathing exercises.

Pretest, implementation, and posttest phases were used to collect data.

Pretest phase

Researchers using all study instruments start gathering information to establish baseline data about patients’ biodemographic, disease-related triggering factors, the number of days of antacid consumption/ week, disease-related clinical symptoms severity and frequency, patient’s sleep quality, and the impact of the disease on health-related quality of life. These items of assessment took about 30–45 min to be completed.

Implementation phase

The researchers prepare the environment so that it is calm and quiet, well- ventilated, and well-lit before the starting exercise performance.

In an appropriate well-prepared room, the researchers gave 20 min for patient’s face-to-face education about the disease’s nature, signs, and symptoms, triggering factors, different management modalities, and drug adherence (30–45 min before a meal) / spreading of dose (morning and evening) to help patients in behavioral change.

Each patient was interviewed at the gastroenterology outpatients’ clinic via scheduling a meeting with them on the same day for his/her follow-up appointment.

To make the technique and the key ideas of each phase clear, the researchers gave each patient a specially created, colorful, illustrated booklet with photographs.

For a further explanation to ensure proper execution of each step, the researchers role-play and videotape the abdominal exercise technique after the researcher’s initial demonstration in front of the patients and before having them re-demonstrate it.

For abdominal breathing, patients were instructed to:

- Free their mind of anything that is straining it out and take a seat as far back on a chair as they can.

- Next, abdominal breathing exercises were performed (around 10–15 patients/day) under the direction of an internal medicine doctor.

- Inhale normally and slowly through the nose while keeping the mouth shut, as done with smelling a flower.

- Slowly exhale through pursed lips. The patient’s one hand at the top of the chest and the other on the abdomen, just below the ribs. Slowly inhale through the nose until the tummy has inflated as far as it can on the hand.

- Retain the other hand on the chest, try exercising at regular intervals throughout the day.

- The patient’s daily breathing will incorporate this approach as it becomes more natural with repeated use.

- For four months, this exercise was performed 2–3 times daily for 15–20 min on an empty stomach or two hours after meals; the duration and intensity of the abdominal breathing exercises could be changed depending on the patient’s stamina.

- Rather than meeting patients in outpatient clinics during their follow-up, researchers contacted them weekly by phone calls to follow their compliance with the exercise.

Post-test phase

The patients were reassessed after two and four months using the same data collection instruments (except part one in the first instrument) then comparisons were done to evaluate the belly breathing effectiveness on sleep and life quality among patients with non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux.

Statistical analysis

Collected data were described using Mean and Standard Deviation (SD) for numerical data and frequency and percentage for categorical data. The McNemar test, extended McNemar test, paired-t-test, and Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used to compare changes in studied parameters throughout the study phases, as appropriate. The Spearman correlation coefficient (Rho) was used to assess the correlation between studied variables. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05. Data management was carried out using STATA/SE version 11.2 for Windows (STATA Corporation, College Station, Texas). 14

Results

Table 1 presents that the Mean age of studied patients was 42.5 years with more than half of them (56%) being female and highly educated (university / above). Also, more than half of them (58%) were physical workers and lived in urban areas but little less than half of them (48%) consumed unprescribed NSAIDs.

Table 1.

Distribution of the studied patients according to their socio-demographic characteristics: (No. = 100).

| Variable | (No. %) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age/ year (Mean ± SD) | 42.56 ± 9.14 | |

| Sex | Male | 44 |

| Female | 56 | |

| Educational level | Elementary / below | 20 |

| Middle education | 24 | |

| University / above | 56 | |

| Occupation | Physical work | 58 |

| Mental work | 14 | |

| No occupation/ housewife | 28 | |

| Residence | Rural | 42 |

| Urban | 58 | |

| Associated chronic diseases (N.= 40) | Diabetes mellitus | 18 |

| Hypertension | 28 | |

| Liver disease | 10 | |

| Unprescribed NSADs consumption | Yes | 48 |

NSADs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Table 2 explains that post-intervention in most of the subjects identified GERD-triggering factors by two and four months compared with pre-intervention in high statistically significant differences at p-value < 0.001. Furthermore, the mean smoked cigarettes decreased from 7.73 in pre-intervention to 5.48 and 3.92 by 2 and 4 months with high statistically significant differences at p-value < 0.001. Also, the Mean BMI of subjects lowered throughout the study phases, from 27.99 pre-intervention to 26.95 and 25.89 respectively post-intervention, with high statistically significant differences at p-value < 0.001.

Table 2.

Distribution of the studied patients according to GERD-triggering factors throughout the study phases (N. = 100).

| Variable (N.= 100) | Pre intervention | Post-intervention by two months | Post-intervention by four months | P1 | P2 | P3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tea intake (cups/day) | <5 | 56 | 72 | 82 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| ≥5 cups/day | 44 | 28 | 18 | ||||

| Coffee intake (cups/day) | ≤2 cups/day | 40 | 60 | 72 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0005 |

| >2 cups/day | 60 | 40 | 28 | ||||

| Diet type | Vegetarian | 16 | 16 | 16 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Non-vegetarian | 84 | 84 | 84 | ||||

| Eating to bedtime hours | <2 | 74 | 38 | 26 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0005 |

| ≥2 | 26 | 62 | 74 | ||||

| Physical activity | Sedentary | 72 | 24 | 16 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| Non-sedentary | 28 | 76 | 84 | ||||

| Tight-fitting clothing | Usually used | 56 | 14 | 6 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| Avoided | 44 | 86 | 94 | ||||

| Triggering foods and drinks | Usually used | 18 | 0 | 0 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.00 |

| Avoided | 82 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| Eat smaller meals and slow down | Yes | 36 | 82 | 96 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0001 |

| No | 64 | 18 | 4 | ||||

| Elevate head of bed | Yes | 18 | 90 | 90 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.00 |

| No | 82 | 10 | 10 | ||||

| Smoked cigarettes/day (N.= 48) | Mean ± SD | 7.73 ± 1.25 | 5.48 ± 0.99 | 3.92 ± 0.85 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Mean ± SD | 27.99 ± 3.71 | 26.95 ± 3.61 | 25.89 ± 3.38 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

BMI: Body Mass Index.

Comparisons were carried out using the paired t-test for quantitative data, and the McNemar test for qualitative data, as appropriate. Significant differences were considered at p < 0.05.

P1: For comparing preintervention data against postintervention by two months.

P2: For comparing preintervention data against postintervention by four months.

P3: For comparing postintervention by 2 months data against postintervention by four months.

Table 3 reports that the Mean score of completely accurate performance of breathing exercises among studied patients raised from 2% in pre-interventions to 40% and 78% by 2 and 4 months respectively, post-interventions with high statistically significant differences at p-value < 0.001. Regarding to patient’s self-reported exercise compliance improvement was seen from 39% by 2 months to 74% by 4 months post-intervention, with high statistically significant differences at p-value < 0.001.

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations of studied patient’s breathing exercise performance checklist and compliance throughout the study phases (No. = 100).

| Breathing exercise (N.= 100) | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention by two months | Post-intervention by four months | P1 | P2 | P3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score (Mean ± SD) | 1.36 ± 2.17 | 6.82 ± 1.27 | 7.64 ± 0.80 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Accurate complete performance | 2 | 40 | 78 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Accurate incompletely performance | 32 | 59 | 21 | |||

| Not done/ Fault | 66 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Patient’s self-reported exercise compliance | Post intervention by two months | Post intervention by four months | P | |||

| To some extent | 61 | 26 | ||||

| Completely compliance | 39 | 74 | ||||

Comparisons were carried out using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for quantitative data, and the McNemar test and extended McNemar test for qualitative data, as appropriate. Significant differences were considered at p < 0.05.

P1: For comparing pre-intervention data against post-intervention by two months.

P2: For comparing pre-intervention data against post-intervention by four months.

P3: For comparing pos-tintervention by 2 months data against post-intervention by four months.

Table 4 confirms that the total mean score of patients’ GERD symptoms frequencies reduced from 26.64 pre-intervention to 17.61 and 9.58 respectively post-intervention by two and four months, with high statistically significant differences at p-value < 0.001. Besides the total mean score of GERD symptoms severity reduced from 26.49 to 19.13 and 12.19 by two and four months post-intervention, with high statistically significant differences at p-value < 0.001.

Table 4.

Means and standard deviations of studied patient’s symptoms severity and frequencies throughout the study phases: (No = 100).

| GERD symptoms | Mean ± SD | P1 | P2 | P3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention by two months | Post-intervention by four months | ||||

| GERD symptoms frequencies | ||||||

| Heartburn | 2.39 ± 0.55 | 1.67 ± 0.68 | 1.09 ± 0.69 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Regurgitation | 2.32 ± 0.75 | 1.57 ± 0.65 | 108 ± 0.60 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Bad breath | 1.85 ± 1.21 | 1.09 ± 0.94 | 0.70 ± 0.80 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Dysphagia | 2.14 ± 0.79 | 1.29 ± 0.62 | 1.16 ± 0.71 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0008 |

| Nausea | 1.60 ± 0.68 | 1.16 ± 0.49 | 1.03 ± 0.52 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0003 |

| Vomiting | 1.24 ± 0.77 | 0.83 ± 0.68 | 0.66 ± 0.70 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Epigastric pain | 1.41 ± 0.57 | 1.07 ± 0.45 | 0.87 ± 0.56 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea | 1.72 ± 0.79 | 1.29 ± 0.62 | 1.08 ± 0.63 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Sore throat | 1.30 ± 0.93 | 0.77 ± 0.55 | 0.40 ± 0.49 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Belching | 1.27 ± 0.53 | 0.80 ± 0.47 | 0.33 ± 0.51 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Chest pain | 1.89 ± 0.76 | 1.23 ± 0.58 | 0.79 ± 0.61 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Chronic cough | 1.83 ± 0.70 | 1.22 ± 0.46 | 0.94 ± 0.55 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Hoarseness | 1.42 ± 0.65 | 0.88 ± 0.43 | 0.59 ± 0.55 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Globus | 1.10 ± 0.78 | 0.70 ± 0.56 | 0.44 ± 0.56 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Tooth erosions | 0.97 ± 0.85 | 0.58 ± 0.57 | 0.30 ± 0.48 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Bloating / Flatulence | 2.19 ± 0.61 | 1.46 ± 0.67 | 0.99 ± 0.73 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total score | 26.64 ± 6.64 | 17.61 ± 5.00 | 9.58 ± 4.26 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| GERD symptoms severity (No. %) total score (0–48) | ||||||

| Total score | 26.49 ± 7.47 | 19.13 ± 5.56 | 12.19 ± 4.73 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Mild (0–16) | 6 | 31 | 83 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Moderate (17–33) | 77 | 69 | 17 | |||

| Severe (34–48) | 17 | 0 | 0 | |||

GERD: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease.

Comparisons were carried out using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for quantitative data, and the extended McNemar test for qualitative data, as appropriate. Significant differences were considered at p < 0.05.

P1: For comparing pre-intervention data against post-intervention by two months.

P2: For comparing pre-intervention data against post-intervention by four months.

P3: For comparing post-intervention by 2 months data against post-intervention by four months.

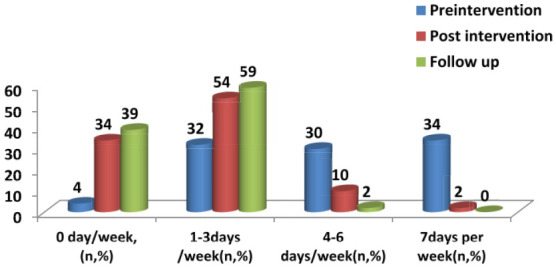

Figure 1 illustrates that antacid consumption among patients taking it 7 days / week was 34% pre-intervention but reduced to 2% and 0% postintervention by two and four months, respectively. Adversely, patients who did not take antacids daily increased from 4% pre-intervention to 34% and 39% postintervention by two and four months, respectively.

Figure 1.

Distribution of studied patients according to antacid consumption days/ week throughout the study phases: (No = 100).

Table 5 shows improvement in sleep quality among studied patients whereas patient’s related sleep suffering decreased from 10.18 pre-intervention to 6.1 and 4.38 post-intervention by two and four months, respectively with a highly statistically significant difference (p < 0.001). On the other meaning, good sleeper was 24% pre-intervention then elevated to 62% and 90% post-intervention by two and four months, respectively with a highly statistically significant difference (p < 0.001).

Table 5.

Means and standard deviations of studied patient’s sleep quality throughout the study phases: (No = 100).

| Pittsburgh sleep quality items (N.= 100) | Mean ± SD | P1 | P2 | P3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention by 2 months | Post-intervention by 4 months | ||||

| Subjective sleep quality | 2.02 ± 0.68 | 1.54 ± 0.73 | 1.4 ± 0.85 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0002 |

| Sleep latency | 1.80 ± 0.85 | 1.02 ± 0.74 | 0.72 ± 0.53 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Sleep duration | 1.58 ± 0.88 | 0.90 ± 0.67 | 0.58 ± 0.61 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Habitual sleep efficiency | 1.84 ± 0.86 | 0.94 ± 0.74 | 0.84 ± 0.73 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Sleep disturbances | 1.62 ± 0.92 | 0.96 ± 0.75 | 0.54 ± 0.67 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Use of sleeping medication | 0.24 ± 0.43 | 0.16 ± 0.37 | 0.04 ± 0.20 | 0.005 | <0.001 | 0.0005 |

| Daytime dysfunction | 1.08 ± 1.00 | 0.58 ± 0.78 | 0.26 ± 0.52 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total score | 10.18 ± 4.40 | 6.1 ± 3.53 | 4.38 ± 2.60 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Good sleep (0–7) | 24 | 62 | 90 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Average sleep (8–14) | 60 | 37 | 9 | |||

| Poor sleep (15–21) | 16 | 1 | 1 | |||

Comparisons were carried out using the paired t-test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for quantitative data, and the extended McNemar test for qualitative data, as appropriate. Significant differences were considered at p < 0.05.

P1: For comparing pre-intervention data against post-intervention by two months.

P2: For comparing pre-intervention data against post-intervention by four months.

P3: For comparing post-intervention by 2 months data against post-intervention by four months.

Table 6 reveals improvement in the heartburn total mean score which decreased from 26.94 pre-intervention to 17.38 and 12.42 respectively by two and four months post-intervention with high statistically significant differences at p-value < 0.001. Additionally, there was a reduction in regurgitation total score from 18.06 pre-intervention to 12.04 and 8.90 respectively post-intervention by two and four months, with a highly statistically significant difference. Regarding GERD patients’ current health-related quality of life, only 1% was satisfied pre-intervention but by two- and four-months post-intervention percent reached 32 and 72 respectively, with a highly statistically significant difference at p-value < 0.001.

Table 6.

Means and standard deviations of studied patient’s GERD health-related quality of life throughout the study phases: (No = 100).

| Studied patient’s GERD health-related quality of life | Mean ± SD | P1 | P2 | P3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention by 2 months | Post-intervention by 4 months | |||||

| How bad is heartburn? | 3.20 ± 0.92 | 2.14 ± 0.98 | 1.26 ± 0.94 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Does heartburn present with lying down? | 2.68 ± 0.55 | 1.56 ± 0.70 | 1.14 ± 0.80 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Does heartburn present with standing? | 2.26 ± 0.69 | 1.46 ± 0.73 | 1.00 ± 0.63 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Does heartburn present with after meals? | 3.28 ± 0.70 | 2.70 ± 0.67 | 2.10 ± 0.61 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Does heartburn change your diet? | 3.48 ± 1.07 | 2.44 ± 0.81 | 1.84 ± 0.79 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Does heartburn wake you from sleep? | 2.64 ± 1.18 | 1.18 ± 1.22 | 0.98 ± 1.14 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0004 | |

| Do you have difficulty in swallowing? | 1.96 ± 1.15 | 1.24 ± 0.86 | 0.76 ± 0.71 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Do you have pain while swallowing? | 2.48 ± 1.00 | 1.60 ± 0.83 | 1.18 ± 0.74 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Do you have gassy or bloating feeling? | 2.66 ± 0.87 | 1.44 ± 0.88 | 0.92 ± 0.63 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Affection of reflux medication on daily life? | 2.30 ± 0.54 | 1.62 ± 0.60 | 1.24 ± 0.55 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Heartburn total score | 26.94 ± 6.26 | 17.38 ± 5.12 | 12.42 ± 4.44 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| How bad is the regurgitation? | 3.30 ± 0.95 | 2.28 ± 0.83 | 1.70 ± 0.70 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Does regurgitation present with lying down? | 3.26 ± 0.56 | 2.20 ± 0.63 | 1.50 ± 0.58 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Does regurgitation present with standing? | 2.12 ± 1.06 | 1.32 ± 0.91 | 0.90 ± 0.73 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Does regurgitation present with after meals? | 3.44 ± 0.86 | 2.46 ± 0.81 | 1.86 ± 0.72 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Does regurgitation change your diet? | 3.38 ± 1.08 | 2.44 ± 0.90 | 2.04 ± 0.78 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Does regurgitation wake you from sleep? | 2.56 ± 1.29 | 1.34 ± 0.98 | 0.90 ± 0.93 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Regurgitation total score | 18.06 ± 4.34 | 12.04 ± 3.50 | 8.90 ± 2.88 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| GERD patient’s current health related quality of life | Satisfied | 1 | 32 | 72 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Neutral | 61 | 68 | 28 | ||||

| Dissatisfied | 38 | 0 | 0 | ||||

GERD: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease.

Comparisons were carried out using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for quantitative data, and the McNemar, and extended McNemar test for qualitative data, as appropriate. Significant differences were considered at p < 0.05.

P1: For comparing pre-intervention data against post-intervention by two months.

P2: For comparing pre-intervention data against post-intervention by four months.

P3: For comparing post-intervention by 2 months data against post-intervention by four months.

Table 7 documents that there was a significant negative correlation between patients’ abdominal breathing compliance and GERD symptoms severity, symptoms frequency, and antacid consumption days /week post-interventions by four months (p = 0.0004, 0.001, and 0.041, respectively). There was a significant positive correlation between patients’ breathing exercise compliance and patients’ sleep quality two months post-intervention (p = 0.007). Patients’ compliance was positively correlated with heartburn and regurgitation scores pre- and two months post-intervention (p ≤ 0.001). Patients’ current health-related quality of life was correlated with patients’ abdominal breathing exercise compliance pre-intervention (p = 0.004)

Table 7.

Correlation between patient’s abdominal breathing exercise compliance and symptoms severity and frequencies, days number of antacid consumption /week, sleep, and life quality throughout the study phases (No = 100).

| Patient’s outcomes | Patient’s compliance with belly breathing exercise | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre intervention | Post intervention by two months | Post intervention by four months | ||||

| Rho | P | Rho | P | Rho | P | |

| GERD symptoms severity | 0.287 | 0.004 | −0.119 | 0.238 | −0.344 | 0.0004 |

| GERD symptoms frequencies | 0.290 | 0.003 | −0.381 | 0.0001 | −0.460 | <0.001 |

| Antacid consumption days /week | 0.335 | 0.0007 | −0.333 | 0.0007 | −0.205 | 0.041 |

| Sleep quality | 0.126 | 0.212 | 0.269 | 0.007 | 0.061 | 0.547 |

| GERD patient’s current health related quality of life | 0.283 | 0.004 | 0.142 | 0.16 | 0.055 | 0.588 |

| Heartburn total score | 0.316 | 0.001 | 0.392 | 0.0001 | 0.072 | 0.476 |

| Regurgitation total score | 0.382 | 0.0001 | 0.373 | 0.0001 | 0.153 | 0.127 |

GERD: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease; Rho: Spearman correlation coefficient; statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

Discussion

Attention has been gained to the devastating negative effect of GERD on all quality-of-life domains whether physical, social, psychological, or spiritual of affected individuals. Meanwhile, abdominal breathing is an effective modality for GERD management that could improve various aspects of the disease and could play an important role in the management of GERD-related symptoms. 15 Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to evaluate the abdominal breathing effectiveness on sleep and life quality among patients with non-erosive gastro esophageal reflux.

The first hypothesis was accepted according to the present study which revealed that post-intervention, most patients improved GERD triggering factors identification by two and four months compared with pre-intervention with high statistically significant differences. This finding was consistent with Yuan et al., who reported that patients who followed all recommended habitual changes experienced significant improvement in lifestyle factors (fast eating, spicy food, very hot foods, drinking tea and coffee, and smoking) after a 6-month follow-up. 16

Also, the present study illustrated that the mean score of completely accurate performance of abdominal breathing exercises among studied patients raised from pre-intervention to two and four months post-interventions. Moreover, the patient’s self-reported exercise compliance significantly increased by four months after intervention. This result was agreed with Xu et al., who reported that the majority of patients in the intervention group demonstrated significantly higher self-efficacy and compliance for better performance of abdominal respiration after 3 months of intervention compared to the non-intervention group. Also, they completed all breathing steps in a correct manner after training. This could be related to the provided patient’s motivation and enthusiasm for self-management, better remission of symptoms, and improvement in psychological distress by researchers. 17

Otherwise, the second hypothesis was proved as the present study stated that the total mean scores of GERD symptoms frequencies and severity were significantly reduced at two- and four-month post-intervention compared with pre-intervention. This finding was supported by a previous study, which reported a significant improvement in signs and symptoms of GERD after practicing breathing exercises compared to pre-intervention. Breathing exercises for two months had a significant effect on decreasing GERD manifestations such as heartburn, chest pain, bitter taste, presence of hoarseness, and sore throat compared to pre-exercise. 18 In addition, Hosseini et al., found that the mean scores of symptom frequency and severity decreased significantly after the intervention. This indicated that diaphragmatic breathing could alleviate symptoms and improve the quality of life among patients who had GERD. 19

Moreover, the current study showed that the mean of patient’s smoked cigarettes and BMI were significantly reduced by two and four months post-intervention compared with pre-intervention. These findings were congruent with Ahmed and Khalil, who found that there was an improvement in the patient knowledge and practices in all aspects of lifestyle factors. Quit smoking was improved and body weight was also decreased with highly statically significant differences between pre/post and follow-up program implementation. This could be related to patients’ commitment to instructions in order to reduce GERD symptoms to feel better and work effectively. 20

The third hypothesis was accepted for antacid consumption, as the current study revealed that the proportion of patients on antacid consumption 7 days/week was 34% pre-intervention but reduced to 2% and 0% post-intervention by two and four months, respectively. In agreement, it was found that 80% of patients in the intervention group significantly reduced antacid consumption compared with pre-intervention. This could be related to the positive effect of diaphragmatic breathing on reducing regurgitation and heartburn sensation, which resulted in patients decreasing their usage of antacid medications. 21

Meanwhile, the fourth hypothesis was accepted as the present study showed that there was a significant improvement in patient sleep quality post-intervention by four months compared to pre-intervention with a highly statistically significant difference. In consistence with this finding, it was stated that at the end of the third month, patients reported that they felt much better with “falling asleep much easier.” This was due to abdominal breathing that could relieve symptoms and promote relaxation which help patients to improve their sleep quality. 22 Additionally, breathing had a positive effect on improving sleep quality and the quality of life of patients with GERD post-intervention with a statistically significant difference. This could be related to breathing exercise that alleviates GERD symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation so, patients can sleep and feel better. 23

Concerning patients’ GERD health-related quality of life, the fifth hypothesis was accepted because the present study showed significant improvements in the total mean scores of both heartburn and regurgitation post-intervention by two and four months compared with pre-intervention. In line with these results, it was reported that after three months of intervention, the total mean scores of heartburn and regurgitation decreased at a significant level in patients who performed breathing exercises. 24 Moreover, GERD health-related quality of life scores significantly improved whereas GERD common symptoms of both heartburn and regurgitation significantly reduced after four weeks of intervention than before. 25 Additionally, a significant decline in gastrointestinal symptoms rating scale and health-related quality of life scores from baseline to the first follow-up and the second follow-up was recorded. This indicated that patient abdominal breathing coaching can effectively reduce symptoms and improve the quality of life of GERD patients. 26

From another point of view, the majority of studied patients were satisfied post-intervention with their current health related quality of life compared to pre-intervention with a highly statistically significant difference. In accordance with this, Ahmadi et al. reported that breathing exercise training significantly improved the quality of life of the patients and the majority of them had greater satisfaction post-intervention compared to before the study. This could be related to abdominal breathing that improved their exercise capacity, respiratory function, and affects positively GERD clinical symptoms. 27

This study confirmed a significant inverse correlation between patient breathing exercise compliance and GERD symptoms severity, frequencies, and antacid consumption at two- and four-month post-intervention. This finding was congruent with Qiu et al., who reported that there was a negative correlation between breathing exercises and GERD symptoms, and acid suppression usage whereas patients who performed breathing exercises had lower mean scores of GERD symptoms severity and frequencies. Moreover, the number of acid suppression usage decreased post-intervention with a statistically significant difference. This was due to abdominal breathing that can improve pressure generated by the lower esophageal sphincter. The possible mechanism behind this is the enhancement of the anti-regurgitation barrier, especially crural diaphragm tension. 7

While there was a significant positive correlation between the patient’s breathing exercise compliance and sleep quality, GERD patient’s current health-related quality of life, heartburn total score, and regurgitation total score post-interventions by two and four months. This result was in agreement with Hosseini et al., who found that there was a positive correlation between breathing exercises and health-related quality of life as there was a reduction in reflux symptoms and increased quality of life in the experimental group after four weeks of practicing diaphragmatic breathing with a statistically significant difference. 19

The main limitations of the present study were the differences in breathing exercise techniques related to the limited guaranteed ability of its quality among studied patients and lack of contradicted studies with this study’s results.

Conclusion

As the study findings revealed, abdominal breathing presenting better therapeutic improvements in all patients’ outcomes as reduction of GERD symptoms severity and frequencies, little anti acid consumption, more sleep quality and more satisfaction with health-related quality of life.

Recommendations

For practice:

- Encourage healthcare professionals, especially nurses to integrate abdominal breathing with the treatment protocols of patients with non-erosive GERD.

- In-service continuous updated training programs about abdominal breathing exercises should be designated and presented in special training sessions to all patients with GERD.

- Study replication with a large probability sample and different geographical area is recommended to confirm abdominal breathing exercise practice efficacy.

For education:

- Awareness enhancement programs regarding GERD-triggering factors through mass media should be disseminated by authorized personnel.

- A manual pamphlet about abdominal breathing exercises should be accessible to healthcare professionals as a reference to be distributed among patients who suffer from GERD.

Footnotes

Author’s contributions: All authors contributed to the study conception, design, and material preparation. Data collection was performed by [AE] and [RT]. Data entry and analysis were carried out by [HB], [HS], and [HE]. The first draft of the manuscript was written by [HM] and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing at Menoufia University.

Availability of data and materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Consent to participate: Informed consent was obtained from all patients. This contains information about the aims of the study and intervention, data required, privacy, and confidentiality. All patients have every right to participate, not participate in, or withdraw from the study at any time.

Code availability: Not applicable.

References

- 1. de Bortoli N, Tolone S, Frazzoni M, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease, functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome: common overlapping gastrointestinal disorders. Ann Gastroenterol 2018; 31(6): 639–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Taraszewska A. Risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms related to lifestyle and diet. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 2021; 72(1): 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roman S, Mion F. Refractory GERD, beyond proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2018; 43: 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fass R, Boeckxstaens GE, El-Serag H, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021; 7(1): 55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nair A, Alaparthi G, Krishnan S, et al. Comparison of diaphragmatic stretch technique and manual diaphragm release technique on diaphragmatic excursion in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomized crossover trial. Pulm Med 2019; 2019: 6364376. DOI: 10.1155/2019/6364376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yu Y, Wei R, Liu Z, et al. Ameliorating effects of transcutaneous electrical acustimulation combined with deep breathing training on refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease mediated via the autonomic pathway. Neuromodulation 2019; 22(6): 751–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Qiu K, Wang J, Chen B, et al. The effect of breathing exercises on patients with GERD: a meta-analysis. Ann Palliat Med 2020; 9(2): 405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boulton KHA, Dettmar PW. A narrative review of the prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Ann Esophagus 2022; 5(7): 7–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9. King IM. A theory for nursing: systems, concepts, process. New York: Wiley, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Orem D, Taylor S, Repenning K. Nursing: concepts of practice. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 1995, [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ali MA, Yasir J, Sherwani RN, et al. Frequency and predictors of non-adherence to lifestyle modifications and medications after coronary artery bypass grafting: a cross-sectional study. Indian Heart J 2017; 69(4): 469–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buysse D, Reynolds C, Monk T, et al. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989; 28(2): 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Velanovich V. The development of the GERD-HRQL symptom severity instrument. Dis Esophagus 2007; 20: 130–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stata Crop. Stata statistical software: release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Halland M, Bharucha AE, Crowell MD, et al. Effects of diaphragmatic breathing on the pathophysiology and treatment of upright gastroesophageal reflux: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2021; 116(1): 86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yuan LZ, Yi P, Wang GS, et al. Lifestyle intervention for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a national multicenter survey of lifestyle factor effects on gastroesophageal reflux disease in China. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2019; 12: 1756284819877788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xu W, Sun C, Lin Z, et al. Evaluation of a self-management program for gastroesophageal reflux disease in China. Gastroenterol Nurs 2016; 39(5): 385–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mahmoud FH, Mahmoud BH, Ammar SA. Effect of practicing deep breathing exercise on improving quality of life of gastroesophageal reflux disease patients. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci 2018; 7(5): 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hosseini A, Shorofi SA, Jackson AC, et al. The effects of diaphragmatic breathing training on the quality of life and clinical symptoms of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a randomized controlled trial. Adv Integr Med 2022; 9(2): 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ahmed Hussein Ahmed H, Hassan Saied Khalil H. Impact of educational program for patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease on lifestyle change and home remedies. Egypt J Nurs Heal Sci 2021; 2(2): 338–362. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ong AM, Chua LT, Khor CJ, et al. Diaphragmatic breathing reduces belching and proton pump inhibitor refractory gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 16(3): 407–416.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu H, Miller K, Arguello E. Effects of Ba-Duan-Jin based deep breathing on multimorbidity: a case study. Int J Physiother Res 2022; 10(4): 4295–4303. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hamasaki H. Effects of diaphragmatic breathing on health: a narrative review. Medicines 2020; 7(10): 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Demirtaş D, Sümbül HE, Kara B. Diaphragmatic breathing exercises reduce reflux symptoms in non-erosive reflux disease. Oman Med J 2019; 26(4): 545–549. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moffa A, Oliveto G, Matteo FD, et al. Modified inspiratory muscle training (m-IMT) as promising treatment for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Acta Otorrinolaringol Engl Ed 2020; 71(2): 65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Venkateswara R, Sreenu T, Siva B, et al. Impact of patient education on quality of life in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Int J Pharm Phytopharm Res 2022; 12(1): 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ahmadi M, Amiri M, Rezaeian T, et al. Different effects of aerobic exercise and diaphragmatic breathing on lower esophageal sphincter pressure and quality of life in patients with reflux: a comparative study. Middle East J Dig Dis 2021; 13(1): 61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]