Abstract

Nanomaterial advancements have driven progress in central and peripheral nervous system applications such as tissue regeneration and brain-machine interfacing. Ideally, neural interfaces with native tissue should seamlessly integrate, a process which is often mediated by the interfacial material properties. Surface topography and material chemistry are significant extracellular stimuli that can influence neural cell behavior to facilitate tissue integration and augment therapeutic outcomes. This review characterizes topographical modifications, including micropillars, microchannels, surface roughness, and porosity, implemented on regenerative scaffolding and brain-machine interfaces. Their impact on neural cell response is summarized through neurogenic outcome and mechanistic analysis. We also review the effects of surface chemistry on neural cell signaling with common interfacing compounds like carbon-based nanomaterials, conductive polymers, and biologically inspired matrices. Finally, the impact of these extracellular mediated neural cues on intracellular signaling cascades is discussed to provide perspective on the manipulation of neuron and neuroglia cell microenvironments to drive therapeutic outcomes.

Keywords: Surface topography, Substrate chemistry, Cell signaling, Neurogenesis, Neural Interfaces

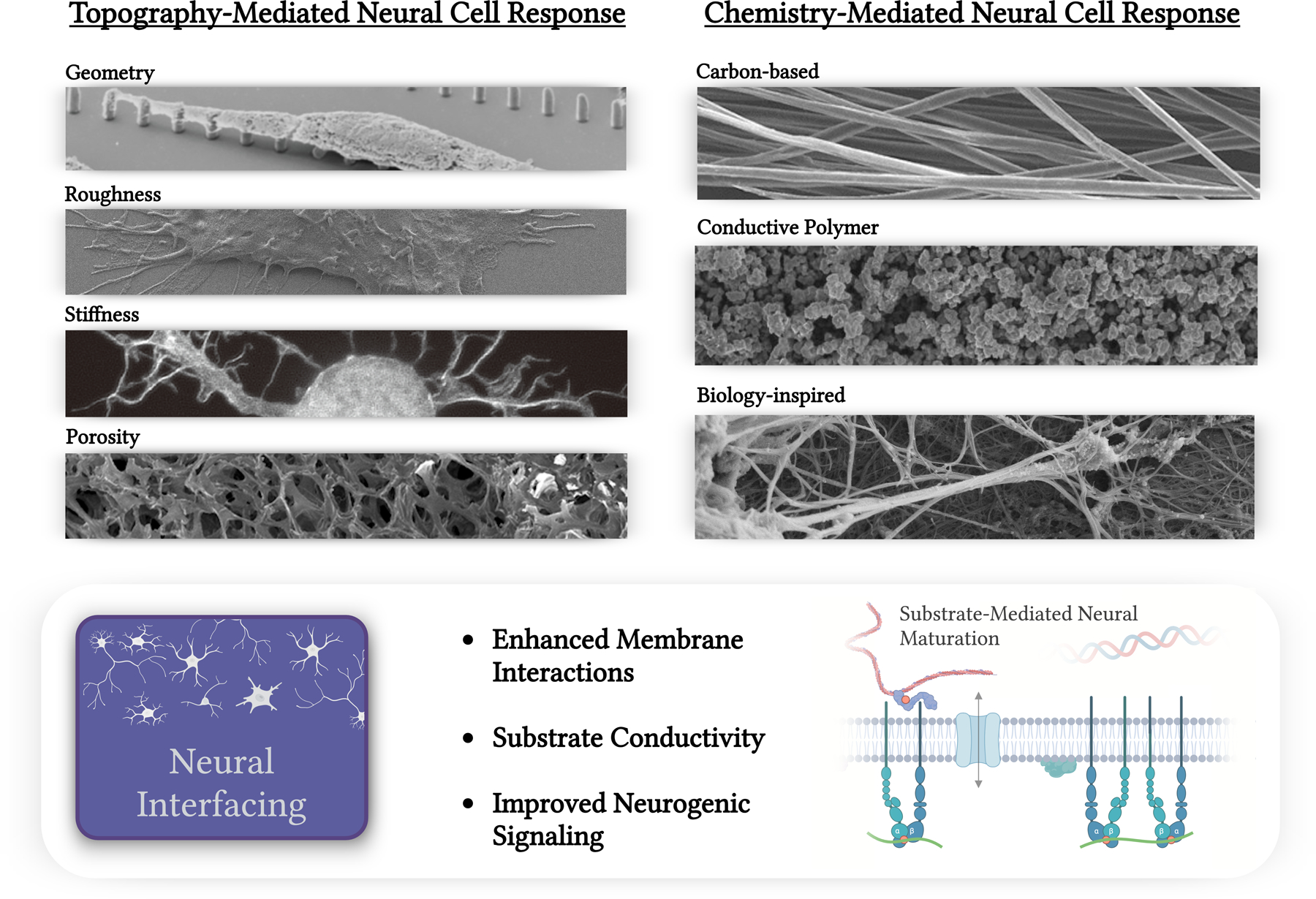

Graphical Abstract

Surface topography and material chemistry are significant extracellular stimuli that influence neural cell behavior to facilitate tissue integration and augment therapeutic outcomes. This review characterizes topographical modifications and surface chemistry on neural cell signaling to improve neural interface outcomes. The impact of extracellular mediated cues on intracellular signaling cascades provides perspective on the manipulation of neural microenvironments to drive therapeutic success.

1.0. Introduction:

The central and peripheral nervous systems (CNS and PNS, respectively) are complex networks having electrophysiological and biochemical signals that dictate sensory, motor, and visceral processes. Studying the functional relationships of CNS neurons and neuroglia is essential to understanding region-specific neural behavior and how it changes across normal and abnormal physiological conditions. Initially, neural interface technologies were utilized as tools for research to decode spatiotemporal function of CNS tissue [1–5]. As mapping experiments became more complex and region-specific activity was uncovered, numerous neural interface applications arose including an increased attention to chronic interfacing therapies and neural regeneration efforts [6–8]. Since then, neural interface technologies have grown considerably, focusing on the seamless reintegration of neural tissue into implanted substrates to facilitate therapeutic outcomes that include nervous tissue regeneration and the restoration of sensory and motor function. Although the relationship between neurons and neuroglia allows for remarkable tissue plasticity and function, innate neuroprotective mechanisms can frustrate therapeutic modalities such as tissue regeneration and brain-machine interfaces (BMI) [9–11]. The success of these therapies relies on the proliferation, maturation, and integration of neurons/neuroglia onto engineered constructs implanted within the native tissue. In recent years, complex nanomaterial development and surface engineering techniques have been the focus of neural interface engineering to improve upon conventional materials that lack bioactivity and chronic interfacing properties. Substrate topography and chemistry can significantly influence the behavior of interfacing neural cells by manipulating the tissue microenvironment. Consequently, the development of interfacing materials capable of optimizing biocompatibility and the therapeutic outcome has increased dramatically. Although neural regenerative engineering and BMI interfacing may differ in application, their interface requirements are not mutually exclusive and oftentimes benefit from similar surface engineering techniques that encourage neural cell recruitment and healthy tissue reintegration.

For tissue regeneration applications, the regeneration and reintegration of neural tissue rely on a scaffold’s biochemical, bioelectrical, and biomechanical characteristics which should mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM) (Figure 1). Scaffolds interact with the cellular microenvironment to proliferate, differentiate, and reintegrate cells as functional members of the surrounding native tissue. Several design considerations can minimize cell death, decrease inflammation, and maximize cell penetration. Substrate nanotopography is a powerful tool to manipulate and guide cell signaling through extracellular cues and guidance. The surface properties and modifications of scaffolding materials, such as surface roughness, porosity, and micropillar/microgroove formation, have all been shown to manipulate cell behavior to achieve enhanced therapeutic outcomes [17–21]. In addition to topographical alterations, interface chemistry impacts stability and biocompatibility due to the direct molecular-level interactions at the membrane/ECM surface. Although less characterized, the chemical structure of interfacing surfaces elicits varying levels of surface receptor expression which impacts membrane protein compositions, ion concentration gradients, and potential intracellular cascade activation [22–24].

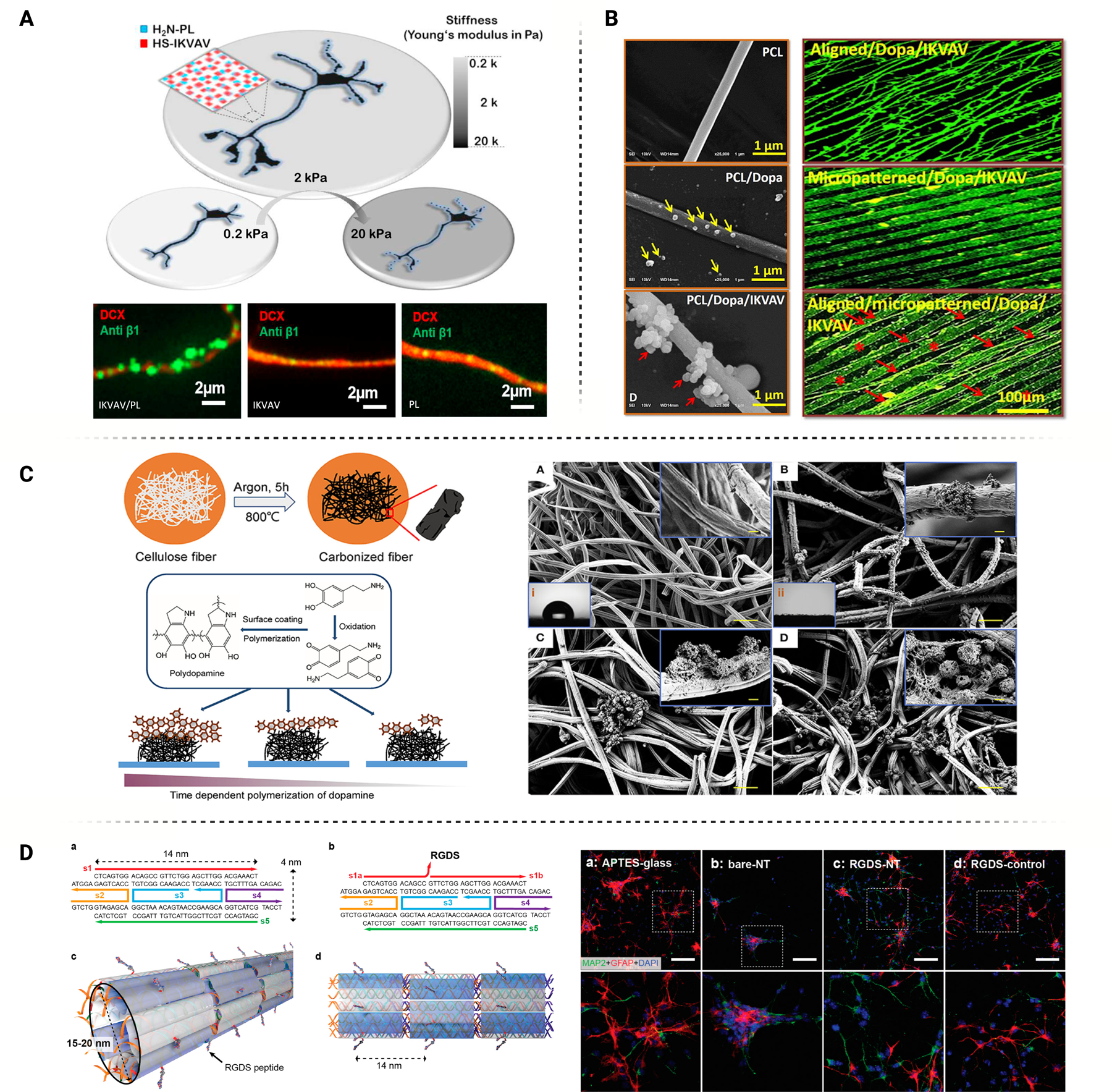

Figure 1.

Summary of physical modifications to neural interfaces including porosity [12], geometry [13], stiffness [14], and roughness. All cited categories are from works adapted to this figure under the Creative Commons license (CC BY 3.0 or 4.0). Additional chemical substrate modifications are categorized into carbon-based [15], conductive polymer [16], or biologically-inspired chemistries. All cited categories are from works adapted to this figure under the Creative Commons license (CC BY 3.0 or 4.0). Neural interface applications discussed within include brain machine interfacing and CNS/PNS regenerative scaffolding.

Implanted BMI electrodes for stimulating and recording nearby neurons aim to achieve neural reintegration while simultaneously minimizing innate immune reactions. Electrophysiological recordings rely on detecting spatiotemporal variations in ionic concentrations generated by neurogenic cells. A healthy device-tissue interface will enhance the signal-to-noise (SNR) ratio for recorded signals, reduce power consumption for stimulation, and increase the functional longevity of the device. For many invasive BMI applications, the foreign body response (FBR) continues to frustrate chronic phase interfacing through reactive tissue encapsulation. Neuroglia are driven to the interface of BMI devices through the compounded impact of insertion trauma, microenvironmental inflammatory signaling, mechanical mismatch, and poor device interface properties. The accumulation of reactive neuroglia physically and electrically isolates the device, negatively impacting its stability and signal quality [25, 26]. Surface topography and chemistry can increase adhesion and enhance electrogenic cell behavior while reducing the recruitment of reactive neuroglia, enabling healthy interfaces. By modulating protruding nanostructures and promoting focal adhesion site formation, the cleft between the device and cell membrane is strengthened and the seal resistance of the surrounding tissue is enhanced [27]. In addition, chemical modifications such as incorporating carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and conductive polymers (CPs) can regulate the response of neurons/neuroglia through receptor-specific molecular interactions and electrochemical reactions during signal transduction [28]. An increasing number of in vivo electrophysiology studies are incorporating surface engineering and material chemistry into probe design, targeting both the functional (electrode sites) and non-functional areas, to minimize the immune response and enhance neural proliferation at the implant site. However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, these studies have primarily been in animals s. Further research and development are needed to advance surface topography and chemistry modifications into human studies and evaluate their ability to enhance the chronic performance of BMIs.

Since surface topography and chemistry can have a significant influence on neural cell behavior, this review article summarizes the progress in developing surface-mediated neurogenic cues for regenerative and BMI applications. We also summarize mechanistic studies involving high-resolution transcriptomic analysis that characterize neural cell response through signaling cascades that impact neurogenesis and electrogenic function.

2.0. Etched and Patterned Nano/Micro-Topography:

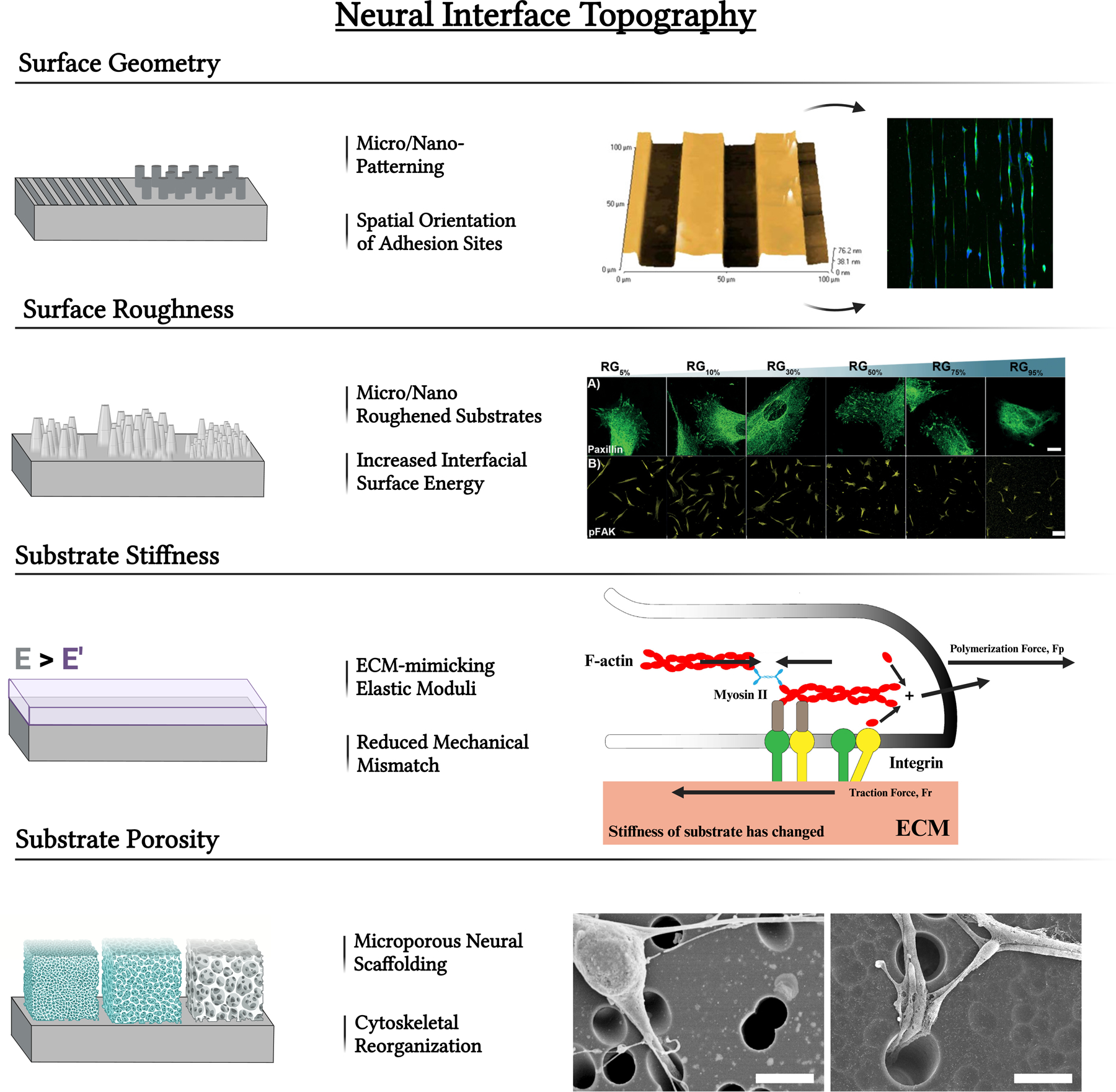

Manipulating substrate geometry is an effective way to influence cell response as the brain’s microenvironment is sensitive to external forces and stimulation. Strategies to reduce neuroinflammation are especially important as inflammation can prevent the desired neural integration and regeneration, including neural proliferation and differentiation. Well-studied surface modifications include roughness, micropillars, microgrooves, pores, and stiffness variability (Figure 2). The impact these topographies have on cellular behavior can be evaluated through neural viability, maturation, and inflammation. In addition, mechanistic studies are conducted to elucidate the specific cellular mechanisms and pathways responsible for the changes in neural behavior.

Figure 2.

Neural interface modifications including the alteration of substrate geometry using micro/nano-patterning techniques. These can result in microgrooves, microchannels, micropillars, or other modifications that impact the spatial orientation of adhesion sites. Figure adapted with permission from Pardo-Figuerez et al. [29] under the Creative Commons license (CC BY 3.0 or 4.0). Alteration of interfacial energy by altering surface roughness also impacts neural cell response. Figure adapted from [30] under the Creative Commons license (CC BY 3.0 or 4.0). Neural cell interactions may also be impacted by altering surface porosity for network growth. Figure adapted from [31] under the Creative Commons license (CC BY 3.0 or 4.0). Substrate stiffness similar to native tissue ECM can facilitate a superior device-tissue integration. Figure adapted from [32] under the Creative Commons license (CC BY 3.0 or 4.0).

2.1. Surface Geometry:

2.1.1. Micropillars:

Micropillar topography features structures having high aspect ratio are capable of directing change in stem cell and neural cell behavior through contact and nano compressive characteristics. Arrays of micropillars interact with cell networks to induce and regulate cell adhesion through mechanotransduction via the formation of focal adhesion complexes [33]. Depending on the array design, these adhesions can deform/elongate the nuclear envelope, promote radial migration, and enhance cellular organization based on the control of spacing in the array. Functionalization of micropillar topographies can direct differentiation of stem cells into cell lineage termination and has achieved regulation of proliferation and cell fate through the Ca2+ ion-dependent Wnt signaling [34].

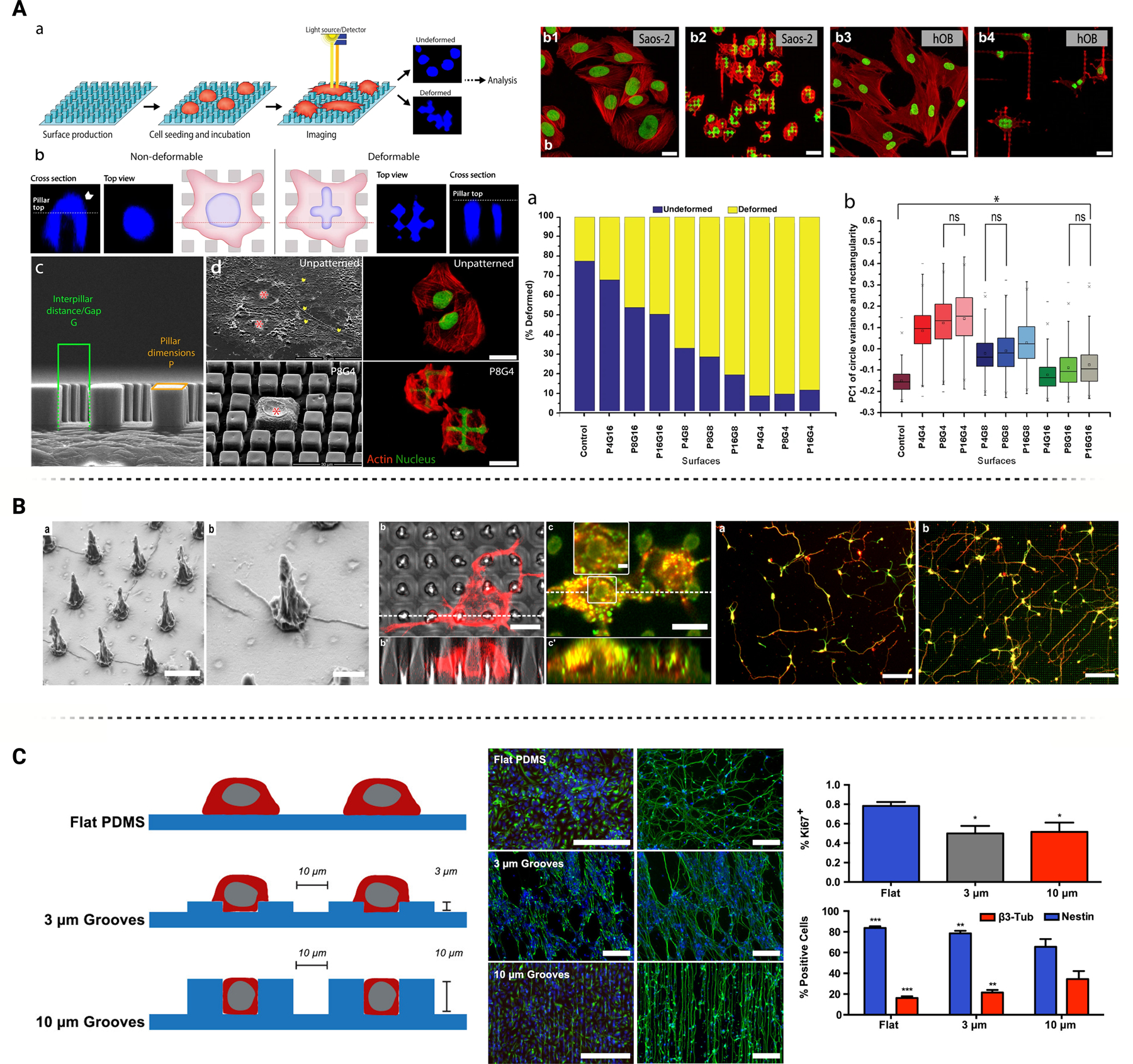

Several studies investigated the mechanism of micropillar topography interaction with the cell interface, permitting operational control of adhesion and subsequent signaling of the cellular network. Doolin et al. studied the interaction of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) through micropillar assays, and the effect of spacing and height on mechanotransductive responses through the cell-surface interface [35]. Over three weeks, MSCs within micropillar arrays displayed mechanical deformation as the adhesion to the substrate directed cell mobility, cytoskeletal deformation forces, and the forces acting on the nucleus for elongation. Narrowing of array spacing resulted in robust MSC infiltration from 2D culture to the array; actin expression in the formation of focal adhesions was increased. Adhesion to micropillar arrays have also demonstrated a significant contribution to nuclear deformation which has been implicated in enhanced differentiation, proliferation, and migration of cells [36, 37] (Figure 3A). Micropillar arrays facilitate a high rate of binding to fibronectin in the ECM, giving rise to greater cell mobility mechanisms. Cellular mobility plays a significant role in developing cell signaling networks and tissue formation. In the context of neural networks, characterized by their plastic structure, cellular mobility emerges as a dominant factor and exerts a profound influence in the formation of intracellular signaling pathways. Activation of mechanosensing pathways to cell stretching, like that observed in the stretch-activated ion channel PIEZO1, has a significant influence on matrix mechanical signal transduction and also impacts neural stem cell or neuroglia differentiation lineages [38].

Figure 3.

Modifications to neural interface surface geometries including micropillars and etched microgroove/microchannels demonstrate key influence on neural cell behavior. (A) Micropillar induced nuclear deformations over patterned surfaces demonstrate heightened nuclear elasticity and actin activity over Saos-2 cells compared to unpatterned topographies. Figure adopted with permission from Ermis et al. [37] under the Creative Commons license (CC BY 3.0 or 4.0). (B) PH3T micropillar geometries combined with light excitation demonstrate critical upregulation of key neuronal markers MAP2 and TUJ1. Figure adopted with permission from Milos et al. [40] under the Creative Commons license (CC BY 3.0 or 4.0). (C) PDMS microchannels modulate neuronal-linked epigenetic factors at different key depths and channel widths, as well as significant impact on NOTCH pathway capabilities. Surface topographies promote neural lineage and maturation amongst neural stem cell cultures. Figures adopted with permission from Milos et.al. [47]

Micropillar interaction with neural cells can also facilitate intracellular signaling pathway activity. Cutarelli et al. observed the impact of micropillar silicon substrates in inducing adhesion and differentiation of pluripotent stem cells to promote cortical cell maturation [39]. These substrates produced radial migration distinctive of cortical progenitor maturation in vivo. Expression of SOX2 and Nestin were unaffected by micropillar culture, while neuronal marker beta III tubulin was downregulated which indicated sustained stem cell multipotency. Differentiation experiments demonstrated culture upregulation of MAP2 and CUX1 mature neuron markers and increased regulation of beta III tubulin promoting differentiation signaling from stem cells to cortical progenitors. Milos et al. investigated how neuronal cell growth could be modulated through an interface with micropillar substrate topography [40]. Micropillar arrays fabricated of semiconducting polymer, P3HT (Figure 3B), coupled with light excitation resulted in an accumulation of charge (Ca2+ ions) along the cell membrane interface. The resulting interfacial electric field can affect downstream pathways for neuronal functions in growth and differentiation. Local charge density resulted in increased intracellular calcium levels and influenced calmodulin interactions and protein kinase C phosphorylation. Dependent on the material utilized, the geometry of a nanopillar substrate may also influence downstream differentiation of stem cells including the ability to upregulate specific gene markers in Tuj1 and MAP2 pathways for neural-typical differentiation as well as the inhibition of astrocyte activation.

Liang et al. performed a comprehensive study in which a piezoelectric poly (vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) nanopillar array was fabricated through hot pressing, creating an array with hexagonal bases that would taper up to a round column. Fourteen days of rat bone marrow stem cell culture on nanopillar arrays induced neurite outgrowth and natural elongation, indicative of neural differentiation and maturation. Although the focus of this study was ultrasound stimulation, noteworthy findings emerged in the absence of ultrasound. Under 0 W of ultrasound stimulation, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) results at 21 days of incubation revealed a differential expression of the Tuj1 gene, indicating potential early-stage differentiation. This suggests that the unique geometry of the nanopillar, leading to the inherent narrowing of cell morphology albeit higher pseudopod count in adhesion to the substrate, facilitated material deformation, subsequently elucidating a piezoelectric discharge. This local electric field discharge likely activated calcium-dependent voltage channels, thereby regulating the NFkB protein complex [41]. NFkB protein complex activation can play a significant role in the functionalization of neural-like cells and is an influencing factor of neurite outgrowth within ganglion neurons [42].

Astrocyte and neuroglial cell formation have been the subject of several studies investigating the regulatory role of micro/nanopillar substrate geometry. Nanopillar PVDF arrays lead to a downregulation of GFAP astrocyte markers compared to tissue culture plates and natural films [43]. The decrease in GFAP protein expression indicates a reduction in astrocyte formation from seeded stem cells. To elucidate the mechanism behind the downregulation of neuroglial formation, researchers explored the activation of Wnt-mediated cellular pathway, which is calcium-dependent and strongly associated with neural differentiation through electrical stimulation. Activation of Wnt pathway may subsequently trigger Notch pathway activation as a downstream mechanism [44].

In addition, astrocyte and neuroglia respond to the mechanical tension exerted by the pillar geometry upon seeding. The surface tension generated by the pillar geometry restricts cell motility and narrows cell morphologies. This unique characteristic enables the influx of ions through dependent channels, as well as the activation of underlying pathways including Hippo, integrin signaling, and the transcription factor Yes-associated protein (YAP)/TAZ. Therefore, the interaction between glial cell adhesion complexes and nanopillar substrates may regulate the formulation of glial cells through mechanosensing activation of YAP/TAZ [45, 46].

2.1.2. Microgroove/Microchannels:

Microchannel surface modification entails etching longitudinal grooves aligned through the substrate; the resulting topography can influence cell behavior due to defined regions of peaks and valleys. These surfaces provide a degree of alignment that may regulate the drive for neural differentiation from stem cell pluripotency, and enhance proliferation through surface interactions [48]. Moreover, microchannels have been used as nerve guidance conduits (NGCs) to promote nerve growth and guide axonal extension after peripheral nerve injuries. NGCs offer an alternative to invasive surgical procedures like autografts, as they can mimic in vivo nerve situations [49]. These beneficial interface interactions are valuable for neural-based cell therapies and can facilitate a microenvironment for neural system functionalization.

Numerous studies have effectively highlighted the cellular mechanisms involved in microchannel interfaces to explore adherence mechanisms and how this topography influences differentiation, proliferation, and various life cycle functions. Microchannel interfaces may influence neural cell behavior, including neurite alignment, cell maturation, differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) into neural stem cells (NSCs), mechanotransduction on cell shape, and modulation of epigenetic markers [50]. Hsu. et al. observed NSC interactions with microchannel textured substrates of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and the mechanisms through which resulting surface impacted differentiation capacity and functional cell behavior (Figure 3C). Enhanced alignment, particularly with channels having 10 μm ridge/grove width, was achieved. As channel depth was increased, the expression of epigenetic factors AcH3, AcH4, and H3K9me3 was upregulated, often associated with the expression of neurogenic markers NeuroD and BDNF. Significant expression of these markers is associated with nuclear envelope elongation through mechanotransduction following the adhesion of NSCs to the substrate interface, which plays a significant role in ordering intracellular signals among neural networks due to the complex interactions with cell ECM. Finally, a knockdown assay isolated the Notch pathway activation independent of cell-cell contact, and microchannel surface topography was observed to downregulate the Notch pathway [47]. Microgroove topography affects the differentiation potential of neural stem cells, as evidenced by its influence on the Notch signaling pathway through geometric sensing. Notch signaling target genes were altered through the activation of histone deacetylase (HDAC). Histone deacetylation signaling in parallel with topographic-induced epigenetic modulation enhanced the potential for stem cell neuronal differentiation. Additionally, proliferation could be affected by the epigenetic factor Ki67+, demonstrating similar results with the downregulation of proliferation over larger microchannel surface interactions [51].

Microgroove topographies have also demonstrated control of the signaling and function of neuroglia. Singh et al. explored the morphological and biochemical responses of astrocytes interacting with micro-grooved topographies. Modified microgroove surfaces having varying depths resulted in decreased proliferation compared to smooth surfaces which may result from nuclear elongation and subsequent chromatin condensation. Additionally, in exploring the signaling mechanism of topographically induced astrocyte behavior, this study quantified a differential expression in calcium ion concentration. Neuroglia signal transduction has been demonstrated to occur through calcium ion channel activity. Therefore, heightened activity of calcium signaling pathways may influence astrocyte cell behavior, including cellular function especially in contributing to complex neural networks. However, further studies are required to understand this effect [52, 53].

Geometrical alignment of multiple microchannels has allowed observation of interfacial interactions of multiple neural populations with high reliability and measurement via state-of-art sensing techniques. Novel microfabrication procedures can integrate microgroove architectures in microfluidic systems with multielectrode arrays (MEAs), field-effect transistors (FETs), and chemical sensors, enabling the simultaneous stimulation and recording of neural populations to monitor cellular interactions [54], and information flow via synapses [55].

Microgroove channels have been demonstrated as a powerful tool for neural regenerative engineering, particularly through nerve interfacing and repair. Musick et al. used a soft multichannel neural electrode interface between sciatic nerve cells within rats over three months and demonstrated regeneration and electrical measurement potential in mice spinal cord injury (SCI) models. At 2, 8, and 12 weeks post-implantation, histological imaging demonstrated regeneration of the sciatic nerve showing both myelinated and unmyelinated axons, Schwann cells, and connective tissue surrounding the implant indicative of neural regeneration capacity through the surface interface. Researchers observed the formation of an artificial fascicular structure between the regenerating neurons and the microchannel array, as well as heavy collagen and connective tissue along the channel walls indicative of the potential for neural cell adhesion. Chronic recording was studied through the sciatic nerve by observing the conductance of electrical signaling through the microchannel array up to 3 months following the operation. Electrophysiological recording revealed action potential firing was synchronous to the gait cycle of the animal. Increased spike rate over time was attributed to neuronal maturation through the miniature nerve fascicle development and axon myelination. A parallel microchannel (110 × 120 μm2 with a wall thickness of 50 μm and length of 50 mm) allowed directional maturation of regenerating neurons to allow for nerve repair and the quality electrical signal conduction through the sciatic nerve to conduct a gait cycle [56]. Similar observations have been repeated through several different in vitro studies including microchannel arrays cultured with dorsal root ganglion cells [57] and cortical cells [58]. In vivo studies with sciatica nerve deformities [59] demonstrated ideal adhesion of neural cells as well as increased ordered neurite growth and extension. The parallel alignment of microchannels allows for ordering neural cell outgrowth and maturation into potential regenerative repair. Additionally, high throughput electrical stimulation to cultured neural cells [58] or electrical action potential observation in vivo would further quantify the maturation of nerve repair [59] with microchannel electrode arrays demonstrating high-quality resolution in recording electrical activity through nerve fascicles across the sciatic nerve.

Aligned microchannels have also emerged as a promising approach for developing artificial NGCs to address peripheral nerve injuries. NGCs can incorporate micro- or nanopatterns with repeated ridges and grooves that are embedded in biocompatible flexible materials such as PDMS and SU-8 following microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) fabrication techniques [60]. These structures are rolled to form 3D designs with longitudinal channels that mimic the microarchitecture of the endoneurium tube, thereby facilitating axonal growth, nerve guidance, and subsequent regeneration. Park et al. presented a biodegradable NGC with tunable microchannel sizes with the ability to align the regrowth of nerve fibers and recruited host stem cells for enhanced functional regeneration [61]. In their study, micropatterned poly(L-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) (PLCL) sheets were utilized in conjunction with stem-cell recruitment factors (substance P, SP) to create a conducive environment for nerve regeneration and proliferation. The multichannel NGC device was evaluated both in vitro, by assessing the spatial guidance of PC12 cells, and in vivo, by examining the regrowth of injured rat sciatic nerve. The results demonstrated a significant improvement in regeneration outcomes. Shelly et al. explored the control of neuronal cell polarity through micropatterned strips of semaphorin 3A placed in a microchannel substrate design. Undifferentiated neurons exposed to Sema3A in a microchannel design exhibited polarization of neural cells into dendrites through the suppression of axonal development. Elevation of the cGMP/PKG signaling pathway was observed through FRET signaling and was hypothesized to downregulate the activity of cAMP and PKA signaling pathways which play a significant role in the axonal development via LKB1 and GSK3-B phosphorylation. Additionally, in vivo assays in cortical neurons seeded with Sema3A downregulation in microchannels resulted in polarization defects and reduced growth length of neural cells [62]. Microfluidic technology introduces unique capabilities for exploring neural cell signaling by providing greater control of cell fate and functionalization through the cell-substrate interaction and tunable functionalization. This nuanced approach holds great promise in advancing our understand of neural signaling and opens new avenues for precise interventions in cellular behavior and functional outcomes.

2.2. Surface Roughness:

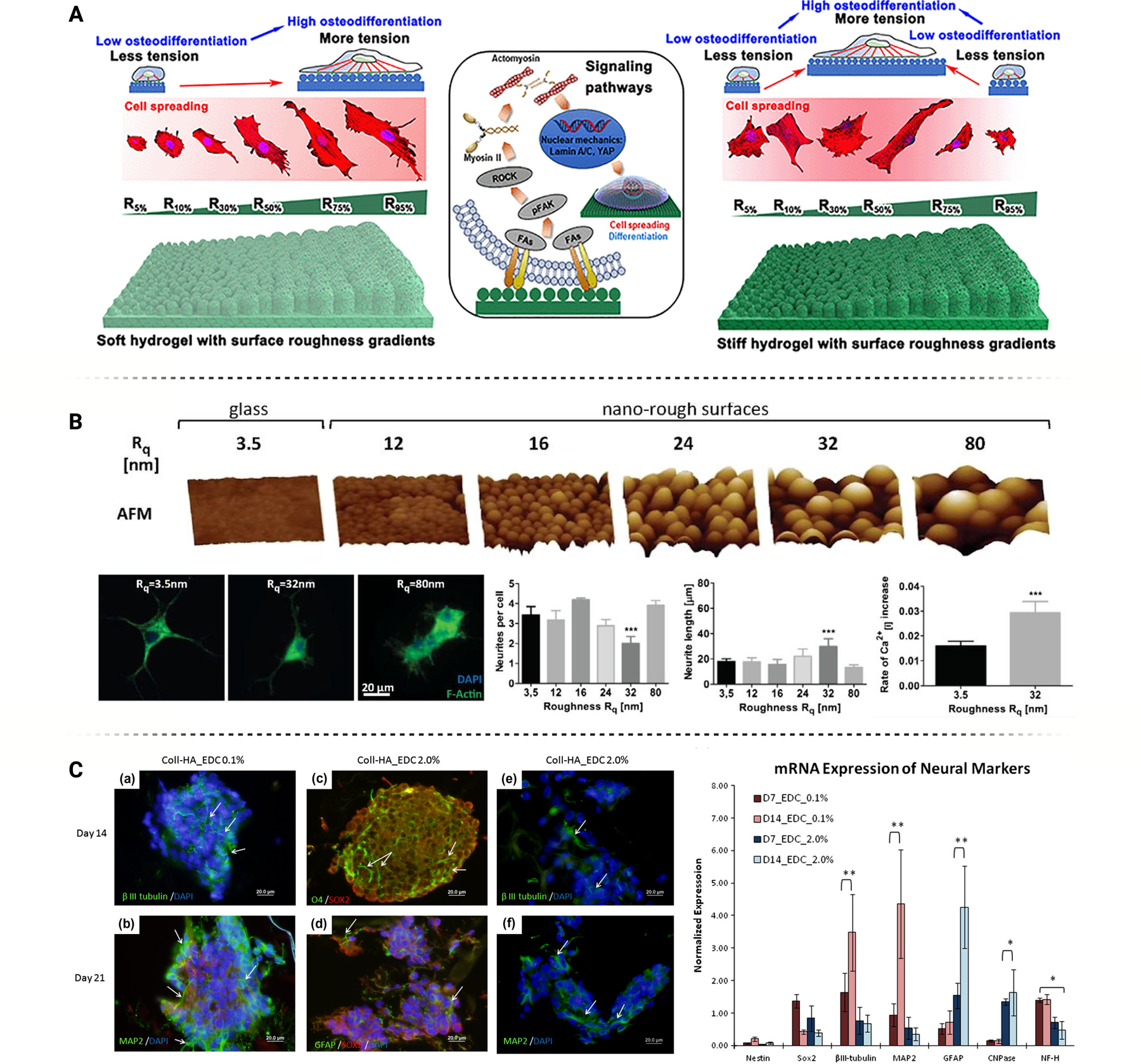

Surface roughness describes the quantifiable deviations in normal vectors across a microtopography. The roughness indicates the measure of micro (and nano)-irregularities across the material interface [63]. Rough surface topography typically encourages cell adhesion through the entrapment of fibrin on the contact interface, leading to a greater interface energy-driven proliferative effect among adhered cells. Topographical roughness along a surface creates a region of high interfacial energy with increased wettability and can lead to improvements in cellular adhesion [64, 65]. In the interaction between substrate topography and cellular environment, the adsorption of proteins has been studied as a potential adhesion region for the cell-substrate interface (Figure 4A). Interfacial energy drives protein adhesion and is proportional to the contact area with the substrate [66]. Driven by a change in interfacial adhesive energy and interface protein adsorption, surface roughness modification can augment neural cell proliferation, differentiation, and innate function. Characterization of this interface and the signaling mechanisms between cells and roughened surface should demonstrate the associated cell-substrate interactions and the mechanism through which this interface interacts and drives cellular function [67].

Figure 4.

(A) Soft and stiff hydrogels, each with the same surface roughness gradients, differentially impact cellular behavior. Figure adapted from Hou et al. [55] with permission. (B) Surfaces with an optimal stochastic nanoroughness, Rq = ~ 23 nm, induce increased neuronal differentiation and longer neurite outgrowth, as compared to smooth surfaces, Rq = ~ 3.5 nm. Figure adapted from Blumenthal et al. [65] under Creative Commons License (CC BY 3.0 or 4.0). (C) Hydrogel stiffness, controlled through concentration of crosslinking agent (EDC), influences stem cell differentiation towards different neural lineages. Figure adapted from Her et al. [83] with permission.

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is a crucial component of cellular adhesion and ECM interactions when interfacing with the topography of a surface. Several research groups have demonstrated the capability of cellular components to sense and facilitate adhesion complexes based on varying nano-scaled roughness among different cell types. Schwartz et al. demonstrated the impact of FAK complex formation of osteoblasts on differentiated micro-rough titanium substrates, inducing the growth factor TGF-B1 for differentiation modulation [68]. Similarly, Deligianni et al. reported comparable adhesion profile results through the attachment of human bone marrow cells onto hydroxyapatite substrates with varying roughness gradients [69]. Although using different cell types, the findings offer a practical explanation for modulation of the adhesion profile through surface roughness, with both studies observing greater cell viability and proliferation rates through an increased adherence at higher roughness values in substrates such as silicon. Researchers hypothesize that the correlation between FAK phosphorylation and favorable adhesion to a nano-roughened substrate is due to surface contact angle and wettability and thus the interfacial energy of a substrate surface. Fan et al. supported this hypothesis with primary substantia nigra neurons cultured on silicon substrates etched to variable roughness gradients [70]. Through tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunostaining and SEM imaging analysis, surfaces with average roughness ranges of 20–30 nm yielded greater cell viability and improved adherence behavior; neuronal cells were able to recognize and migrate based on the magnitude of surface roughness. Cell membrane activity tended towards maximizing interfacial contact area and contact strain between the surface and the cell. In addition to viability control, surface roughness can influence various cellular functions such as inducing neural differentiation pathways and intracellular signaling for functional management.

Several studies investigated the impact of surface roughness on cell-substrate interactions and the mechanism through which stem cells can be induced to differentiate into neural cells. As reported in Pan et al., gene upregulation of ISL1, NeuroD1, and NeuroG1 were observed in evaluating induced pluripotent stem cells seeded onto nano-rough PDMS substrates with RT-PCR, indicating neuronal differentiation after eight days in culture [71]. Increased interfacial energy and adherence profiles allowed neural-induced differentiation by aligning focal adhesion complexes. By providing efficiently aligned anchor points, cytoskeleton and nuclei elongation provided the necessary mechanical tension to alter gene expression through nuclear deformation [36]. In the rearranging of cell nuclear structure, increased expression of the nuclear matrix protein lamin A/C, especially in early differentiation stages, showed a correlation between cellular mechanosensing of nanotopographical cues and epigenetic changes that occur as a cell undergoes differentiation.

Interestingly, the findings presented by Brunetti et al. contradict the prevailing trend of augmented neurogenesis on nano-roughened substrates. Despite this discrepancy, the study highlighted neural cell sensitivity to nanoscale roughness and its importance on FAK activation. Immunohistochemical analysis of Vinculin and Golgi complex of SH-SY5Y cells cultured on nano-roughened gold substrates provided valuable insights into the potential for focal adhesion and cellular viability, respectively. Notably, cellular adhesion and nanoscale roughness were inversely correlated, and roughened substrates demonstrated decreased neuronal polarization and Golgi apparatus functionality through randomized unordered focal adhesion profiles [72]. One plausible explanation for this observation is the adverse impact of nonspecific protein adsorption due to increased substrate wettability. Dysregulated laminin and fibronectin adsorption could result in poor ECM layer formation, impairing neuron adhesion complex functionalization. Hence, careful consideration should be given to the material composition of nano-roughened substrates, as deviations from the general trend of neurogenesis may be due to other factors that alter substrate binding affinity.

Topographical modifications have demonstrated the ability to alter the immune response through microglia and astrocyte formation, which play a vital role in the foundation of immunomodulatory effects of neural immune cells and the development of healthy neural networks. Unlike smooth surfaces, nano-roughened surfaces supporting microglia in vivo and in vitro have exhibited higher induced M2 phagocytic activity indicative of healing mechanism activation [73]. Additionally, higher antioxidant activities, decreased inflammatory markers, and increased anti-inflammatory effects were observed in rough surfaces compared to smoother surface conditions. The inflammatory polarization of primary microglia was observed on smooth substrates compared to roughened groups with cellular adhesion molecule (L1) conjugated to the surface. These modified surfaces activated anti-inflammatory markers such as CD206, CD209, CD163 and the upregulation of Arg-1, Il-10, and TGF B-1 (M2 polarization). Limiting focal adhesion capabilities on a rough surface would demonstrate decreased microglial coverage mediating attachment and spreading microglial cells [74]. Astrocyte interactions determined by topographical roughness are also determined through the mechanical responsiveness of cells concerning topographical roughness. At root mean square roughness (Rq) values of 32 nm, a notable shift in astrocyte behavior towards migratory patterns was observed, accompanied by the reduction in the astrocyte forming factor, evident through discernible morphological changes within cell culture (Figure 4B). Knockdown of mechanosensing pathways that allow for neuron-astrocyte interactions such as Piezo 1, TRPC, and TRPC 6 negated the impact of nanotopography, highlighting the significance of mechanoresponsive receptor expression in neuroglia [75].

Surface roughness also plays an important role when designing neural implants. Traditionally, metals such as gold (Au), platinum (Pt), platinum-iridium (Pt-Ir), and titanium (Ti) are used to fabricate microelectrode arrays for recording electrophysical activity due to their high biocompatibility [76, 77]. Pt, in particular, is regarded as the preferred metal for neural implants owing to its excellent electrochemical stability, impermeability, and corrosion resistance [78]. However, metallic electrodes exhibit certain limitations. The substantial mismatch in Young’s modulus (E) between Pt (154–172 GPa [79]) and neural tissue (0.6–15.2 kPa for human brain [80, 81]) is believed to contribute to tissue inflammation at the implant site, resulting from shear between the metal and surrounding tissue during motion [82]. While the substrate material is commonly identified as the problem, efforts have been directed towards modifying the electrode material to improve neural attachment through increased surface roughness, hence establishing a more favorable interface. Another limitation arises as electrodes are scaled down to match the size of individual neurons, aiming to achieve higher spatial resolution and density. This reduction in size leads to an increase in the charge per unit area that must pass through the electrode for stimulation, and an increase in impedance which negatively impacts recordings [83, 84].

To address both limitations, surface roughening through coatings or modification of the metallic layer has shown promise in enhancing tissue integration and reducing impedance by increasing the electrochemically active area [85–87]. While inorganic coatings like platinum black (Pt-black) [84, 88], titanium nitride (TiN) [89, 90], and iridium oxide (IrOx) [91, 92] have demonstrated improved charge transfer capability and impedance levels, no reports are found on their positive effect on cell attachment or proliferation. In contrast, organic coatings such as CNTs and conductive polymers (e.g., PEDOT) have shown enhanced electrochemical performance and improved neural interfaces, as they can be functionalized to influence biological responses. A comprehensive discussion on organic coatings will be provided in the subsequent sections of this review.

2.3. Substrate Stiffness:

The stiffness of a material surface has considerable influence over intracellular chemical signal production. Neural cells are particularly sensitive to changes in these microenvironmental cues considering their native ECM is comprised of a soft matrix of glycosaminoglycans, proteoglycans, glycoproteins, and low levels of fibrous proteins [93]. The stiffness of brain ECM is 1–3.5kPa, which is substantially softer by several orders of magnitude than most materials used to construct nervous system interfaces [78]. This mechanical discrepancy has been a significant research focus, spurring the development of materials that reduce this mechanical mismatch. Additional work has characterized the cellular mechanisms most impacted by changes in substrate stiffness (Figure 4C). These mechanisms can dictate neurite outgrowth, adhesion quality, synapse formation, and neuroglia behavior at the surface interface which are essential for neuro-regenerative and interfacing applications [94].

The recognition of substrate stiffness plays a pivotal role in modulating essential intracellular signals through the formation of adhesion complexes and activation of FAK. Nonreceptor tyrosine kinase assumes a critical role in mechanosensing, orchestrating integrin and talin interactions between a cell and its microenvironment [95]. FAK complexes have been established as vital mediators in interfacing between cells and the ECM environment, and can respond to changes in microenvironment characteristics including the nano-stiffness of a material. By altering cell adhesion capabilities, several downstream signaling pathways may in turn be activated, subsequently inducing characteristic changes in cell behavior, such as alterations in proliferation rates and differentiation capabilities [96]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the capability of variable substrate stiffness modulating FAK activation in neural cells. Ozgun et al. illustrated this phenomenon in the differentiation of neuroblastomas (SH-SY5Y) across polyacrylamide gels of different stiffness (0.1, 1, and 50 kPa) [97]. The markers p-FAK and Tuj1 indicated neural-like development, which was increased on softer substrates closely resembling natural ECM stiffness. The abundance of p-FAK markers, especially in neuroblastoma culture on soft hydrogels, signifies strengthened focal adhesion and integrin binding interactions, creating strong binding interactions that stimulate neural maturation. FAK activation may also contribute to further downstream pathway signaling, thereby exerting diverse effects on neural cell functionalization. Zhang et al. further elucidated the modulation of FAK activation in PC12 cells over PDMS substrates with varying stiffness to observe cytoskeletal structure, viability, and the influence of matrix stiffness on drug delivery related effects [98]. PDMS stiffness was controlled by altering the ratio of base and curing agent (46.7, 5.3, and 0.1 kPa), creating diverse ECM environments equivalent to collagenous bone, mammary tumor, and adult brain parenchyma, respectively. PC12 cells, when interacting with substrates of varying stiffness, exhibited substantial alterations in neural-like phenotypes including adhesion profile, viability, and cytoskeletal structure. The number and size of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions complexes underwent significant modifications with decreasing stiffness, with the 0.1 kPa substrate promoting the highest state of these adhesion profiles among the cytoskeleton.

The mechanistic effect of neural cell activation on substrate stiffness was explored through RNA transcriptome analysis activation of FAK and related downstream pathways. Through the use of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene Ontology (GO) term analysis, researchers observed differentially expressed genes in related categories of cellular and biological processes contributing to the structural realignment of neural cells on softer substrates. Genes such as EGFR, KRAS, SYT6, and PRKCA exhibited differential expression across varying substrate rigidity, indicating signal transducer activity and the activation of significant neural processes. Downstream activation of the EGFR/P13K/AKT pathway was found to be differentially expressed across variable stiffness environments. This signaling pathway, known for its role in regulating neural cell phenotype and cytoskeletal rearrangement following mechanosensing, provides additional insight into the mechanism behind neural cell behavior given substrate topographical cues. Similarly, Saha et al. demonstrated the capability of substrate rigidity to modulate the signaling of neural stem cells and the adhesion capability of focal interfaces as well as the interactions between bsp-RGD - αvβ3 integrin through the interactions of hydrogel substrates [99]. Neural stem cells cultured on moduli most similar to the physiological stiffness of brain tissue (500 Pa) exhibited a heightened level of neuronal marker beta III tubulin, indicating neural differentiation when compared to hydrogels of varying stiffness profiles (100 – 10,000 Pa).

YAP/TAZ is a master regulator for mechanotransduction and serves as a downstream body in the neural signal propagation from several membrane bound protein signaling pathways including FAK and RhoA, acting to provide nuclear response to substantial stimuli [100]. Regulation of several cell functions can be modulated through this body including cellular homeostasis, proliferation, and cellular differentiation [101, 102]. In response to microenvironment stiffness, YAP/TAZ can be modulated to influence transcriptional machinery which is done through Hippo signaling pathway including the RhoA and LATS1/2 signaling bodies [103]. A mechanical stimulus from a substrate interface may then phosphorylate YAP/TAZ, leading to transduction into the nucleus for phenotypic modification. Particularly in softer substrates, increased focal adhesion may increase upstream RAP2 signaling which in turn influences activity of RhoA, MST1/2, and LATS1/2 to modulate YAP/TAZ. In addition to being regulated primarily through RhoA, YAP/TAZ signaling may also be influenced by various other bodies responding to substrate interfacing [104]. Regulation of this transcriptional effector has demonstrated key control in modulating stem cell fate and influencing neural lineages through substrate interfacial stimuli. Musah et al. reported on the regulation of YAP over hydrogel substrates of variable stiffnesses 0.7–10 kPa, highlighting its impact on stem cell pluripotency and neural-like differentiation [105]. Notably, the formation of focal adhesions along stiff hydrogels promoted long-term stem cell renewal over a 2-week period. Conversely, on compliant soft surfaces, increased f-actin adhesion activity and subsequent depletion of YAP increased transcriptional activity, pushing greater differentiation into neural-like lineages. Inhibiting YAP activity, expedited and enhanced differentiation into neural-like lineages more efficiently than conventional differentiation methods. Differentiation was characterized through differential gene expression of NEUROG2, NEUROD1, SLC17A6, and analysis of electrophysiological functional attributes, revealing traces of spontaneous postsynaptic currents along differentiated cells. Similarly, Engler et al. observed the positive influence of collagen-coated substrates with modulus mimicking brain tissue (Ebrain ∼ 0.1–1 kPa) on the ability of MSCs to differentiate towards neural lineages [106]. Activation of adhesion complexes drove YAP signaling modulation, allowing for the regulation of neural-like development through substrate-cell interfacing. The capability to promote neural cell activity based on YAP/TAZ signaling activity and cell stiffness has allowed for several innovative approaches in neural tissue engineering. Biomedical applications could benefit from the control over YAP/TAZ signaling, particularly for neural systems where the response of cells to mechanical stimuli, such as stiffness, can have significant control over this signaling system and offer a consideration towards substrate design in influencing neural cell behavior.

Neuroglial cells are significantly impacted by substrate stiffness. A study conducted by Blaschke et al. evaluated the functional effects of microglia cultured on surfaces of varying stiffness [107]. Primary rat microglia were grown on PDMS substrates with stiffnesses similar to physiological (0.6 – 1.0 kPa) and supraphysiological (1.2 MPa) values. Soft substrates led to increased proliferative capacity of microglia and M2 polarization, as seen by increased BrdU uptake and increased CD206 expression, respectively. To elucidate response mechanisms to substrate stiffness, microglia were treated with DID to block stretch-dependent chloride channels, which have been shown to control microglial activation. CD206 expression was completely inhibited, indicating that stretch-dependent chloride channels are a primary mechanism in which soft substrates trigger microglia’s anti-inflammatory state. Furthermore, a study conducted by Hu et al. investigated the impact of matrix stiffness on astrocyte phenotype, specifically in regards to scar formation [108]. Notably, astrocytes in the soft matrix had upregulated GFAP and IL-1β expression, suggesting that matrix stiffness mediates astrocyte phenotype and activation. More specifically, matrix softening activated astrocytes into their reactive phenotype, which leads to the formation of glial scars. On the other hand, matrix stiffening reverts astrogliosis, triggering the astrocytes to revert back to their native phenotype. Mechanistic studies revealed that these phenotype shifts in response to matrix stiffness are mediated by YAP activity. Specifically, a decrease in YAP activity is associated with reactive astrogliosis along with an upregulation of GFAP. As illustrated by these studies, substrate stiffness should be a significant consideration when designing interfacing biomaterials due to the complex influence this characteristic has on glial cell binding, neural proliferation, and synaptic strength.

For penetrating neural interfaces that disrupt healthy tissue during implantation to the target region, an ongoing debate exists on probe material stiffness. The implanted probe, or foreign body, elicits an immune response cascade and formation of a surrounding glial scar sheath [109]. This scar increases the distance between the electrode sites and the neuronal processes, degrading achievable SNR for electrophysiological recordings. Traditional rigid penetrating materials such as silicon, glass, or carbon fiber have been shown to exacerbate the immune response at the targeted site [110]. Recent reports suggest that the use of ‘soft’ and flexible probe materials with reduced Young’s modulus (< 10 GPa) can mitigate the severity and size of glial encapsulation post-surgery, enabling long-term interface stability [111–113]. The mechanical trauma and large difference in mechanical stiffness between the implant and tissue can greatly impact the ability to record from neurons near the device-tissue interface over time [9, 114]. With advancements in thin film fabrication techniques such as MEMS, flexible polymeric probes with integrated MEAs have been developed, commonly utilizing polyimide and poly(p-xylylene) (Parylene C) as backbone materials.

Parylene C, a widely used bioinert thermoplastic polymer, has found extensive applications as a tissue-engineering scaffold and as an electrically insulating coating and substrate for neural stimulation and recording applications, including an investigational device used in clinical trials [115–117]. While Parylene can be used as a coating on solid and rigid electrodes, flexible microfabricated Parylene C-based MEAs have gained popularity for invasive stimulation and recording applications in the nervous system. This popularity stems from its apparent reduction of neural immune cell binding and favorable adhesion properties for neuron binding in vitro [118]. In vivo, the performance of the material becomes more complex as invasive devices penetrate through healthy tissue, triggering immune response. Lo et al. suggested that long term gliosis resulting from mechanical trauma and stiffness differences could be mitigated by smaller, more flexible Parylene C-based MEAs, although their study involved only sham devices without electrodes [119]. Other studies have demonstrated acute and chronic implantation of functional Parylene C MEAs. One study demonstrated a decrease in neural loss in targeted implantation area from 40% to 12–17% when comparing rigid silicon probes with soft Parylene C probes [26]. Similar to the findings of Lo et al., safe implantation of mechanically compliant probes often requires the use of stiff introducer or biodegradable polymer coating [111, 113, 120]. The ability to apply polymeric coatings on top of Parylene substrates opens avenues for further modification, such as a drug delivery vector or composite for more nuanced interfacing dynamics [121, 122].

Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) derivatives have been explored extensively beyond tissue interfacing applications. Standalone PEG systems are stiffer than neural tissue (~2 MPa) and have not demonstrated significant promise in vivo as a viable solution to maximizing tissue integration and decreasing adverse neuroglial reactions [123, 124]. PEG-based hydrogels have been developed to improve mechanical properties of PEG. PEGDA (PEG-diacrylate) is formed when the PEG chain ends are functionalized with acrylate groups and crosslinked to create a covalently linked hydrogel network. PEGDA stiffness down to ~300 Pa can be achieved by the soluble implementation of alloc-presenting monomers; through the alteration of the allyl-to-acrylate molar ratio, the reduced stiffness PEGDA falls within the range of neural tissue to significantly improve neural cell growth and neurite extension [125].

Hydrogels consist of a 3D network of hydrophilic polymer chains and can be derived from both synthetic and natural materials. They have tunable structural, chemical, and mechanical properties, and strong biocompatibility depending on the specific material [126–128]. This versatility allows hydrogels to be modified, and as a result, they are commonly used to interface with the CNS. Hydrogel polymerization is oftentimes leveraged as a step to incorporate electrochemical elements without compromising the mechanical characteristics of the scaffold. The blending of hydrogel polymers around electroactive elements creates interpenetrating polymer networks (IPNs) that provide enhancements to hydrogel electrochemical properties while typically preserving interface biocompatibility [129, 130]. Unique instances of polymer blends that include crosslinked and linear chains may entangle to form semi-IPNs which, in the case of conductive polymers, leads to the synthesis of conductive polymer hydrogels (CPHs) [131, 132]. In other cases, electrochemical composite hydrogels may be synthesized by physically suspending conductive elements such as nanoparticles, nanotubes, etc. in a percolation network to enhance electrical conductivity [133–135]. This methodology can be applied across a wide variety of conductive fillers while preserving the primary advantages of hydrogel-based interfaces including the reduced reactive tissue recruitment caused by interface mechanical mismatch.

Matrigel scaffolds have also been utilized as a cell binding membrane for neural interfacing applications including regenerative scaffolds and microelectrode coatings. Impressive neuro-proliferative effects have been observed using Matrigel as a basement membrane for growth in vitro [136]. Shen et al. also demonstrated that Matrigel-based composite microelectrode coatings could serve as a viable interfacing material for stimulation and recording while diminishing glial cell response. Matrigel-COL1 composite coatings were able to decrease adjacent GFAP, Tau1, NF, and CS56 staining while increasing localized NeuN+ signal [137]. While the mechanical and neurogenic properties of Matrigel lend themselves towards promising scaffold systems in the CNS, its chemical composition warrants further consideration. Since Matrigel is an ECM excretion from Englebreth-Holm-Swarm tumors in mice, the reconstituted basement membrane will have innate composition variability [138]. Although most proteins within the Matrigel ECM are structurally relevant (laminin, COL IV, enactin), there are detectable levels of intracellular proteins that will inevitably interact with interfacing cells in vitro or in vivo depending on the experimental application. Therefore, the experimental results gathered from Matrigel-based interfacing studies should be approached with caution due to the variability guaranteed by its composition heterogeneity [139].

Despite significant progress in developing various designs for ‘soft’ penetrating probes, several challenges still need to be addressed to establish long-term, stable BMI. For a more comprehensive discussion on flexible penetrating neural interfaces and the challenges associated with their fabrication and implantation, the reader is referred to the reviews by Weltman et al. and Thielen et al., respectively [109, 110].

2.4. Porous Substrates:

The porosity of a substrate also impacts the differentiation and proliferation of cells. Overall porosity and individual pore size can be controlled and their impact on various neural cell types, including neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes have been studied [140, 141] (Figure 5A). Porous substrates offer a three-dimensional (3D) microenvironment that mimics the ECM, thereby providing structural support, facilitating nutrient transport, and promoting cell-to-cell interactions. While hydrogels have primarily been the focus of porosity related research due to their inherent porosity, porous scaffolds and microporous membranes fabricated from polymers, silks, glass, and metals have also shown great promise. We refer readers to the reviews on material selection and fabrication for porous interfaces from Maksoud et al. and Wen et al. [142, 143]. In addition, comprehensive gene analysis has been applied to determine the specific porosity-dependent pathways that impact cellular behavior. These endeavors enable researchers to design materials with a modified porosity to enhance neural cell interactions with the substrate and desired outcomes.

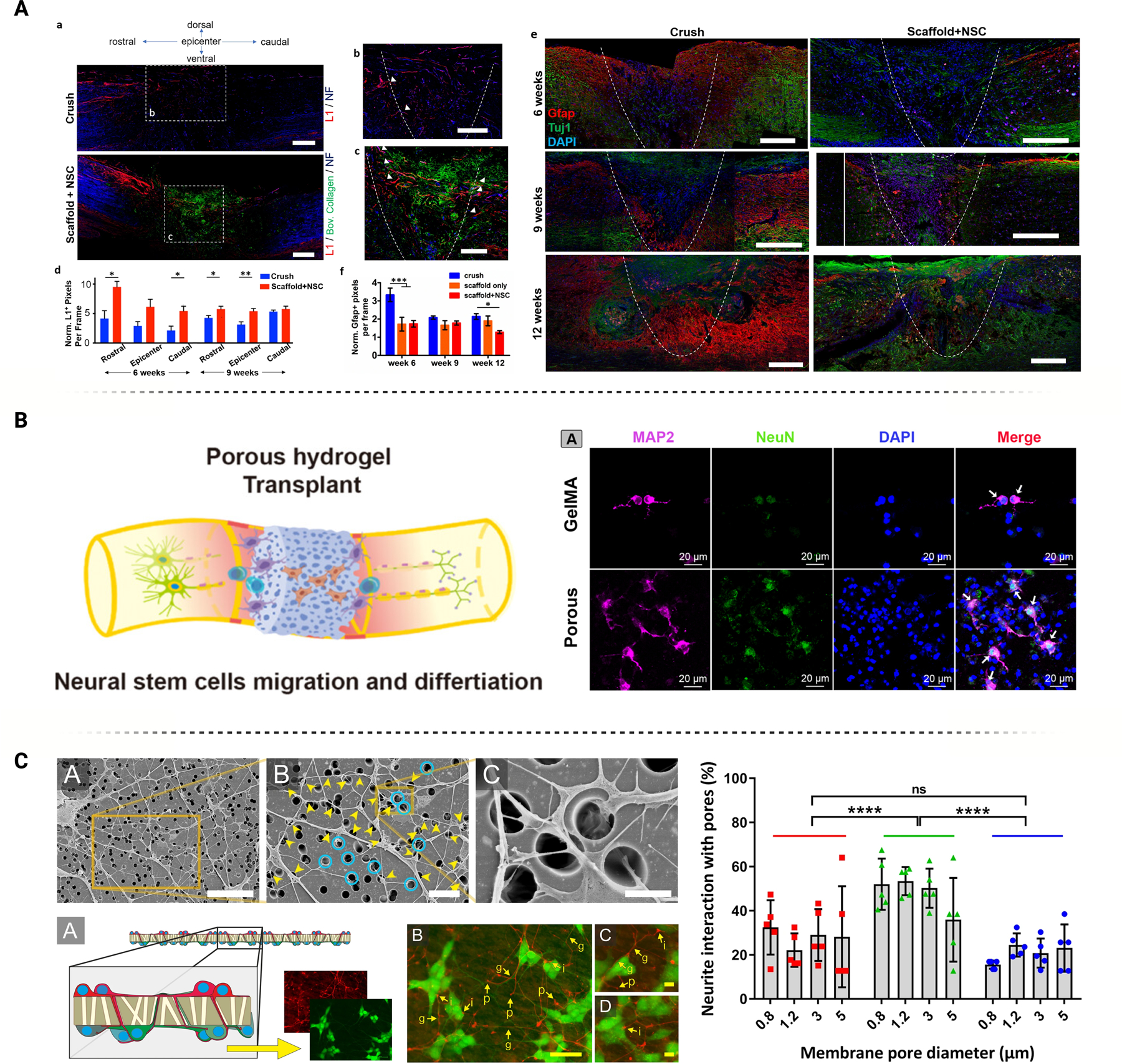

Figure 5.

Porosity, including individual pore size and overall material porosity, can impact neural behavior in a variety of different ways. (A) Porous collagen scaffolds deliver neural stem cells to lesion sites of spinal cord injuries, improving axonal elongation and reducing astrogliosis. Figure adapted from Kourgiantaki et al. [121] under Creative Commons License (CC BY 3.0 or 4.0). (B) GelMA hydrogel with inner connective pores enables cell infiltration, in turn promoting NSC differentiation. Figure adapted from Shi et al. [58] with permission. (C) Neurons can interact with the pores in many ways, including entering the pore itself, crossing over it, or skirting around the edge. Pore diameter can impact these interactions. Figure adapted from George et al. [21] under Creative Commons License (CC BY 3.0 or 4.0).

Many studies investigated the effect of hydrogel porosity on neural cell differentiation and maturation. Shi et al. compared the behavior of NSCs encapsulated in porous and non-porous GelMA hydrogels. In vitro testing revealed that the NSCs in the porous hydrogel migrated further, indicating better cellular infiltration, and exhibited higher viability than in the non-porous counterpart. The porous hydrogel also promoted better differentiation of the NSCs into mature neurons, as seen by the upregulated levels of NeuN and MAP2 (Figure 5B). A deeper analysis revealed that these NSCs specifically differentiated into mature motor neurons given the upregulation of motor neuron progenitor genes, ISLET1, MAP2, and HB9. In vivo implantation of porous hydrogels into rat SCI models demonstrated better functional recovery, diminished inflammatory response, and reduced systematic apoptosis. The porous hydrogel also improved endogenous NSC activation and proliferation while enhancing neurogenesis and neuronal differentiation. Notably, the porous hydrogel had a faster degradation rate than the non-porous version. This degradation may result from a enahnced material exchange rate across the pores or the loss of the agent responsible for inner pore foaming. While faster degradation may be considered a disadvantage for specific applications, improved neuronal differentiation and maturation can be achieved. In fact, enhanced formation of cell lineage and faster hydrogel degradation may signify an advantage to promote the complete reintegration of new tissue [68].

In addition to regenerative applications, porous hydrogels have been used to study the intricacies of neural circuits. Yan et al. developed highly porous and biocompatible hydrogels that effectively modeled highly complex three-dimensional neural networks. A polyacrylic acid/polyvinyl alcohol/polyethylene glycol (PAA/PVA/PEG) hydrogel was designed to serve as an in vitro model that would mimic brain tissue and support neuronal growth. Interestingly, low expressions of GFAP revealed that the hydrogel was astrocyte-resistant, likely due to the highly hydrophilic nature of the hydrogel. However, Tuj1 staining and SEM imaging demonstrated that the porous hydrogel enabled adhesion and differentiation of the neurons and promoted neurite outgrowth and the formation of interactive and complex 3D networks. The biological validity of these neuronal networks was confirmed through recording of spontaneous action potentials and optogenetic stimulation, resulting in frequency-dependent electrical spikes. These results suggest that this porous hydrogel can be used as a model for functional 3D neural network activity, however the lack of neuroglia recruitment limits in vivo translatability [144].

Pore size is a critical factor that can significantly influence cellular behavior. Li et al. conducted a thorough study to determine how different pore sizes affected the differentiation of neural cells, including neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes, using methacrylamide chitosan (MAC) mixed with porogen D-mannitol. To evaluate neural progenitor stem cell (NPSC) differentiation, the hydrogels were cultured in cell-specific differentiation media. Beta III tubulin, RIP, and GFAP IHC confirmed lineage-specific differentiation. Interestingly, while the porous groups produced significantly higher counts of desired cell types than control groups, there was no significant difference in population proportion for different pore sizes (Figure 5C). Additionally, the total cell count decreased with increased porosity, which may indicate that the pores limit NPSC proliferation while promoting differentiation [145].

To elucidate the mechanisms behind enhanced differentiation, Li et al. investigated oxygen diffusion rates in hydrogels of different pore sizes. The results demonstrated that higher porosity was associated with faster oxygen diffusion, creating a more favorable microenvironment that increased cell survival and differentiation. Overall, this study further demonstrated that porous networks improve not only neurogenesis, but also oligodendrogenesis and astrogenesis. However, there was no significant correlation between pore size and neural differentiation [145]. The limited range of pore sizes used (4060 ± 160 to 7600 ± 1550 µm2) may explain this observation. A wider range of pore sizes is likely necessary to observe significant differences in cellular behavior. When using hydrogels for nerve tissue engineering, porosity and pore size can impact cell migration. Specifically, pores with diameters less than 2 µm can inhibit migration. Smaller pores also restrict diffusion, limiting cell survival and differentiation [145, 146]. Another study by Nguyen et al. investigated the anti-inflammatory effects of porous hydrogels on murine BV2 microglia. Specifically, they created hydrogels composed of fucoidan, sodium alginate, and gelatin (SaGFu) with pore diameters varying from 60 – 100 μm and observed that larger pore size better supported microglial growth. Additionally, the anti-inflammatory effect of these hydrogels was determined by measuring the release of several bioactive substances, namely NO, PGE2, and ROS, following microglial activation by LPS stimulation. Results demonstrated that the SaGFu hydrogels could effectively inhibit the production of these inflammatory substances, with the most porous hydrogels having the most significant inhibitory effect. Mechanistic analysis revealed inhibition of NF-κB p65 activation and translocation into the nucleus, which plays a vital role in inflammation and in many neural diseases and disorders [147].

Hydrogel substrates and coatings also have unique drug delivery capabilities, avoiding the complexity of incorporating engineered micro/nanofluidic channels. Porous materials, such as hydrogels, offer an advantage when designing BMI applications and devices, as anti-inflammatory agents can be embedded into the matrix to enhance the tissue-neural interface by reducing the tissue immune response at the implant site. For instance, Huang et al. proposed a novel aerosol jet printing technique to accurately deploy anti-inflammatory nanogels on a flexible polyimide neural probe, constituting a 3D nanocarrier-based interface [148]. The coating, composed of amphiphilic silicone-modified chitosan and natural antioxidant OPC agent, mimicked the physical properties of brain, which alleviated tissue edema at acute phase. Furthermore, this 3D nanocarrier-based membrane reduced tissue trauma in the chronic stages, which decreased the population of activated glia and astrocytes at the implant site and prolonged neuronal survival by 28 days.

Aside from hydrogels, other scaffolds can be modified to control neural differentiation and proliferation, including synthetic sources like poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA) or natural materials such as collagen to mimic the composition of native ECM [149, 150]. Yuan et al. designed double-layer collagen membranes to treat spinal cord injuries. Unequal pore sizes were incorporated to maximize cell adhesion area within the inner compartment (100 μm) and minimize scar tissue formation on the outer contact layer (10 μm). NSC-seeded scaffolds implanted into rat SCI models displayed significantly improved functional recovery four weeks post-op [151]. Furthermore, Ganguly et al. studied how a nanoporous substrate can attenuate the astrocytic response after brain electrode implantation, which often results in a glial scar. Specifically, they cultured rat cortical neurons on anodic aluminum oxide (AAO) surfaces with varying pore sizes (nonporous control, small pore surface with an average pore size of 21.1 ± 2.3 nm, and a large pore surface with an average pore size of 90.3 ± 3.5 nm). Viability assays revealed that the small pore surfaces promoted adhesion and survival of the astrocytes, while the large pore surfaces negatively impacted viability. Focal adhesion number and distribution were evaluated using EGFP fluorescence, suggesting that surfaces with small and no pores (control) had similar numbers of focal adhesions, whereas surfaces with larger pores exhibited significantly more focal adhesions. Additionally, the small pore case had more peripheral focal adhesions than central adhesions, which suggests that peripheral adhesions are responsible for increased cell adhesion. Conversely, the large pore case had more central focal adhesions and the nonporous control had an equal distribution of peripheral and central focal adhesions. These results suggest that astrocytes prefer surfaces with smaller pores rather than larger pores as seen by their improved viability and adhesion [152]. This contrasts with neurons and microglia, which have been observed to exhibit improved behavior on surfaces with larger pores [146, 147]. Given that neural networks rely on the interconnected behavior between these neural cells, the pore size of any therapeutic interface must be carefully evaluated to determine a size that will effectively modulate neural behavior overall, rather than focusing on one specific cell type.

Substantial progress has been made to identify the cellular pathways and mechanisms enhanced by porous substrates. Jin et al. investigated the differences between porous and permeable membranes for human embryonic stem cell (hESC) growth and differentiation. Through a global gene expression profiling analysis, the study revealed that hESCs grown on porous membranes exhibited upregulation of several ECM genes (collagen type XI ɑ1, laminin ɑ3 and ɣ1, and catenin ɑ1, δ1, and β1), integrin, and collagen genes (integrin β1, β5, and ɑV, and collagen type XII ɑ1, type XVI ɑ1, and type XI ɑ1). The heightened expression of cadherin-1 and connective tissue growth factors suggested an upregulation of cell–cell interactions. Furthermore, matrix metallopeptidase (MMP) family proteins along with CD44 were also increased, suggesting enhanced cell–cell and cell–ECM interactions. The upregulation of catenin, collagen, and integrin genes indicated the initiation of Wnt signaling pathway by chemical and topographical properties of the porous membrane substrates. This was corroborated by the detection of translocation of β-catenin into the nucleus along with the upregulation of MMP proteins, which are directly activated by Wnt/β-catenin signaling [153].

Porous substrates were combined with micropillars to create surface morphologies resembling ECM. Wei et al. introduced a nanocomposite structure consisting of biocompatible copolymer poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) nanofibers on PDMS micropillars. The authors employed conventional microfabrication to produce PDMS slabs followed by electrospinning of PLGA nanofibers. The nanocomposite surface was visually evaluated after a 48-h culture of human glioblastoma cells, revealing improved cell morphology compared to the control group cultured on PDMS pillars alone. Moreover, astrocyte proliferation on the nanocomposite exhibited cell morphologies similar to those observed in vivo, as opposed to the control group cultured on flat PDMS. The results were further evaluated through calcium imaging, which demonstrated higher signal amplitudes in primary hippocampal neurons cultured on the nanocomposite substrate (0.038 ± 0.004 DF/F) compared to those on the PDMS control (0.016 ± 0.001 DF/F) [154].

3.0. Synthetic and Biological-Based Substrate Chemistry:

Apart from surface geometry and profile, surface chemistry of topographically modified substrates can play an important role in influencing cell behavior and fate. Cell-to-substrate interactions can drive the success or failure of the intended function of the interfacing material. For instance, a regenerative tissue approach may require an interfacing material with cell-recognizable surface chemistries to enhance cellular proliferation while discouraging inflammatory behavior. In brain stimulation and recording, more complex surface chemistries must be implemented to maximize the functional efficacy of the device interfacing with biological tissue. The significant range of applications that involves direct contact between neural tissue and the foreign body increases the opportunity for novel interface nanomaterial development.

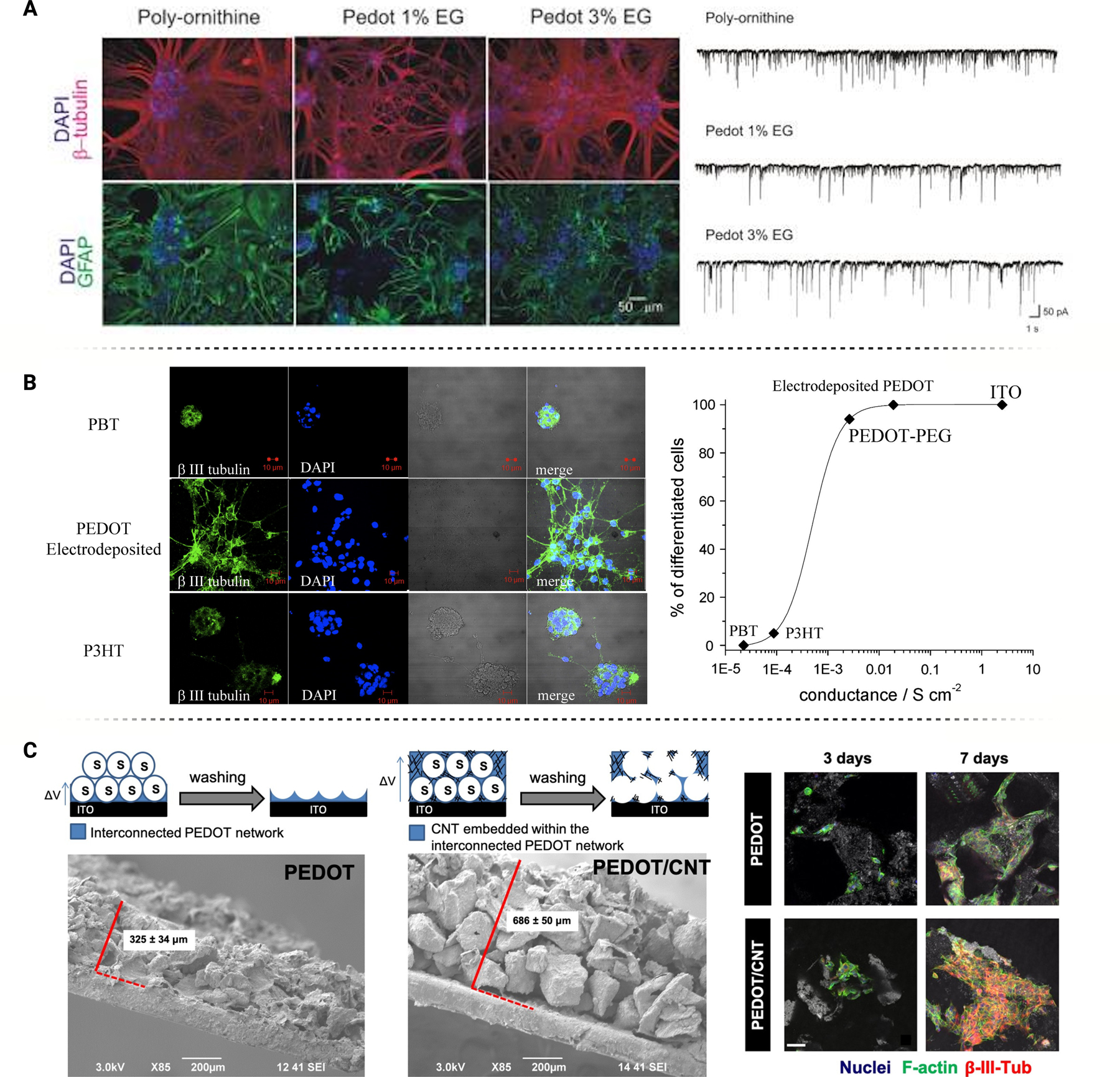

Typically, neural tissue health must be maintained regardless of other specifications required of the interfacing materials. Optimal tissue health may be difficult to achieve based on the types of materials chosen for neural cell interfacing. With a growing interest in nanomaterial coatings and composite-based scaffoldings, it is important to classify and organize the families of materials being studied and their effects on downstream signaling in native neuron populations. Due to the invasive nature of BMI applications, it is also crucial to consider neuroglia recruitment towards these interfaces and how their behavior influences overall tissue health. High-resolution transcriptomic analysis in recent years has driven deeper understanding of these downstream effects resulting from substrate interfacing dynamics. These substrates and scaffolds include carbon-based, polymer-based, and biologically-inspired materials that all uniquely influence neural cell interactions at the tissue interface (Figure 6). The transcriptomic analysis of these interactions has been beneficial in elucidating the cellular mechanisms activated within the scope of individual studies. However, a complete review of these findings may provide a comprehensive insight into the effects of interface material chemistry and neural cell behavior.

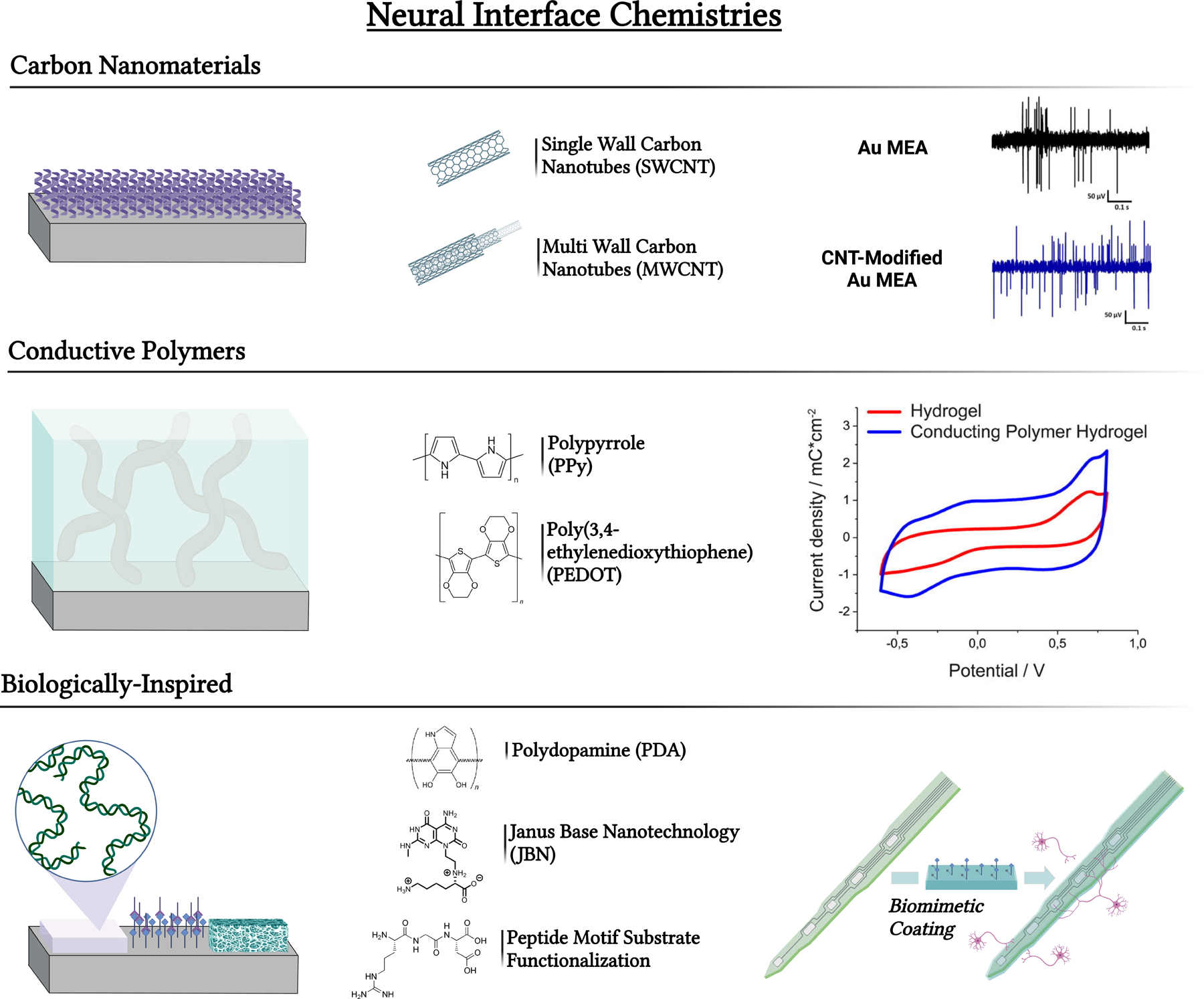

Figure 6.

Common neural interface chemistries can impact therapeutic outcomes depending on conductivity, bioactivity, toxicity, etc. Chemical composition alone can influence cell behavior which can further impact the therapeutic success of the interface. Common interface chemistries include carbon nanomaterials, conductive polymers, and biologically inspired materials. Figures adapted with permission from Vafaiee et al. and Kleber et al., respectively [132, 155].

3.1. Carbon Nanomaterials/Coatings:

Carbon nanomaterials, particularly carbon nanotubes (CNTs), have gained significant attention for their favorable properties, including high surface aspect ratio, robust strength, and high electrical conductivity. In addition, their tunable surface chemistry allows for functional modifications at tissue interfaces. However, recent work has documented the disparity in experimental results regarding the cytotoxicity of carbon nanomaterials, including impurities and long-term oxidative stress. Therefore, it is essential to consider the acute and chronic implications of carbon nanomaterial interactions at bio-interfaces, including the inevitable internalization of these materials through natural processes such as endocytosis or pinocytosis. Especially for chronic-term interfacing, the integration or internalization of carbon nanomaterials require additional consideration due to their lack of degradability, leading to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and natural inflammatory responses [156, 157]. Therefore, the beneficial signaling interactions between carbon nanomaterial interfaces and neural cells should be closely characterized and the cautions associated with acute and chronic phase interfacing be elucidated.

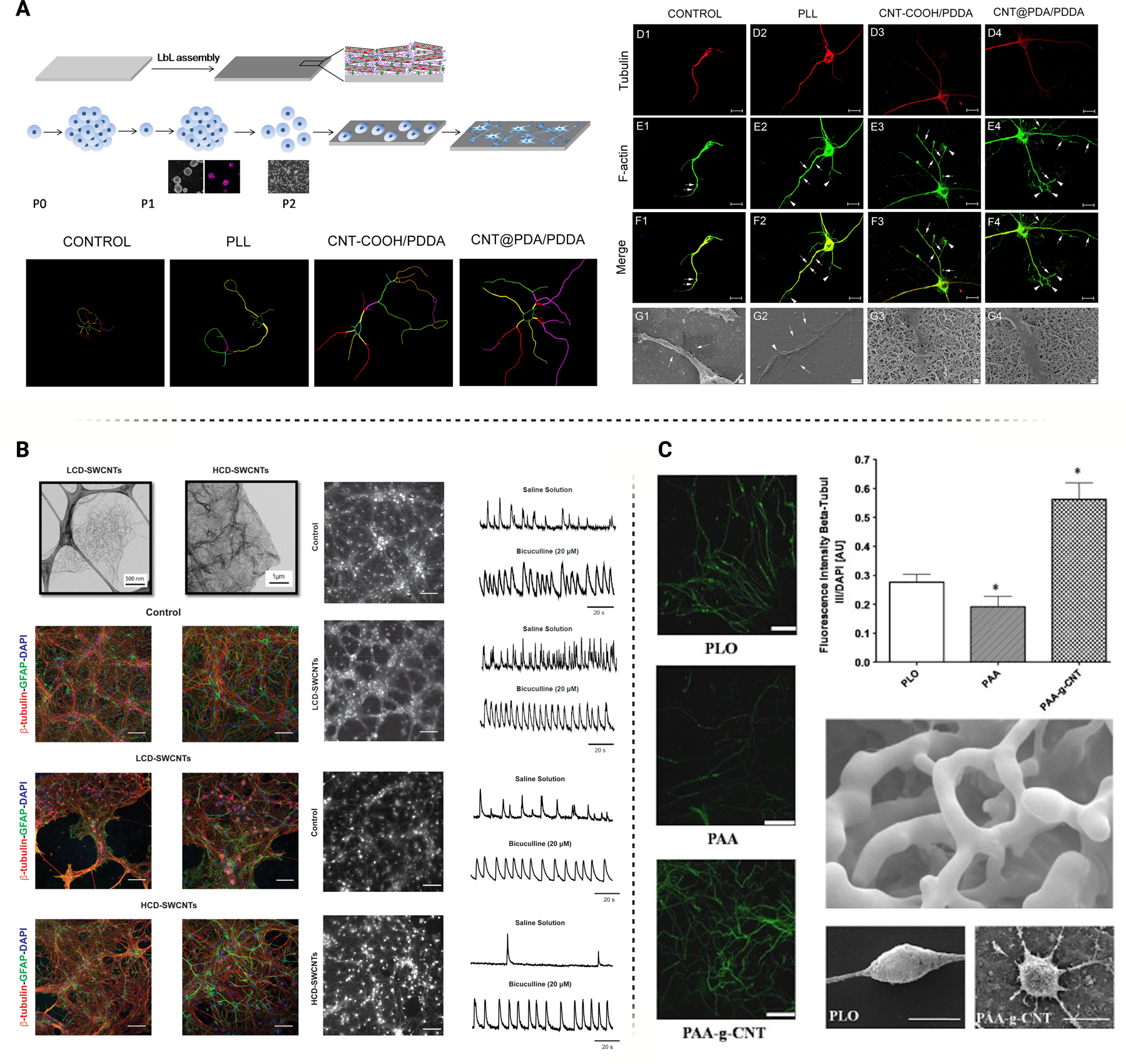

A few studies investigated the cellular mechanisms during neural cell interfacing with CNT surfaces due to their positive influence on proliferation and differentiation. Shao et al. performed RNAseq on NSCs grown on CNT nanocomposites composed of multi-walled CNTs (MWCNTs) and poly(dimethyldiallylammonium chloride) (PDDA). In vitro IHC and electrochemical analysis demonstrated significant neurite outgrowth and electrophysiological maturation (Figure 7A). Differentially expressed gene analysis was performed on enriched biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions to elucidate the mechanisms governing this response. Adhesion-mediated processes were significantly upregulated including cell-substrate, cell-matrix, and cell-cell interactions. Differential gene expression indicated that integrin-mediated adhesion was a primary actuator for increased binding activity. Increased binding affinity to modified substrates typically increased membrane stress caused by cell-substrate mediated junctions [158]. The implication of integrin involvement is unsurprising, as multiple studies have discussed the importance of integrin-mediated adhesion on cellular development and maturation, particularly with nanoscale-modified substrates. With respect to non-bonding interactions, Mondal et al. recently characterized interfacing mechanics involved in CNT binding with adhesion proteins secreted from canine-induced pluripotent stem cells, revealing multiple non-bonding interactions such as hydrogen bonding, salt-bridge, π-cation, and π-π stacking interactions [159]. Cytoskeletal reorganization was observed following CNT binding which manifested actin-filament-based movement and cell contraction. This filament-based reorganization was also responsible for biological processes induced by CNT composite binding, including the myelination processes during NSC differentiation. Neuron ensheathment, myelination, and myelin maintenance were differentiation expressed in gene ontology (GO) analysis. Gap junction activity was also significantly regulated compared to the control, demonstrating the enhanced cell-to-cell activity encouraged by CNT binding. Apart from the specialized binding sites encouraged by CNTs, upregulated matrix secretion activity was also apparent based on GO term analysis. These results agree with previous studies that found significant upregulation of cell-secreted adhesion proteins induced by carbon nanomaterial binding [160]. These results demonstrate a synergistic benefit of synthetic scaffolding that encourages the natural secretion of adhesion-mediating proteins such as laminin, fibronectin, and collagen [160].

Figure 7.

A) Neural stem cell behavior may be actuated through interfacing with CNT composite scaffolds, improving adhesion, viability, neurite outgrowth, and differentiation. Figure adapted with permission from Shao et al. [158] B) Standalone CNT films can impact the development of neural networks and augment signal transduction. The degree of crosslinking between CNTs also impact the strength of the neural circuitry. Figure adapted from Barrejòn et al. with permission [164] C) Poly(acrylic acid) modified with CNTs demonstrate similar improvements in neural viability and neurite outgrowth. Figure adapted with permission from Chao et al. [165]

KEGG analysis can highlight crucial signaling regulatory processes that mediate the communication between binding dynamics and cellular response, like proliferation, differentiation, and cell fate. Recent studies investigated the involvement of FAK as a significant regulatory gateway for downstream signaling during neural cell development. FAK is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase highly expressed in mammalian cells and its innate activity regulates neurite outgrowth and synaptic plasticity. FAK activation also leads to Src binding, which results from integrin-induced signal transduction [161]. Since the proliferative effects of CNT substrates are mainly classified as an integrin-dependent process, FAK activation becomes a significant contributor to the downstream activation of cytoskeletal rearrangement and differentiation pathways like MAPK/ERK, PI3K/AKT, and WNT. The crosstalk between these downstream signaling pathways and FAK activation is well documented, and these differentiation pathways can induce neurite outgrowth, neural excitability, synaptic plasticity, and neural maturation [162–165] (Figure 7B and 7C). FAK is also a known regulator of the Rho GTPase family, a group of guanine nucleotide-binding proteins functioning as binary molecular switches that regulate cell growth cycle, cytokinesis, and cell-cell/cell-matrix interactions. The Rho GTPase family, particularly RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42, can augment many cellular processes, particularly neural cell development and maturation [166, 167]. CNT’s ability to increase binding affinity with neural cells encourages innate bioactivity partially due to the stimulation of FAK through integrin-mediated adhesion and the natural secretion of adhesion proteins.