Abstract

Cancer stem cells (CSCs), accounting for only a minor cell proportion (< 1%) within tumors, have profound implications in tumor initiation, metastasis, recurrence, and treatment resistance due to their inherent ability of self-renewal, multi-lineage differentiation, and tumor-initiating potential. In recent years, accumulating studies indicate that CSCs and tumor immune microenvironment act reciprocally in driving tumor progression and diminishing the efficacy of cancer therapies. Extracellular vesicles (EVs), pivotal mediators of intercellular communications, build indispensable biological connections between CSCs and immune cells. By transferring bioactive molecules, including proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids, EVs can exert mutual influence on both CSCs and immune cells. This interaction plays a significant role in reshaping the tumor immune microenvironment, creating conditions favorable for the sustenance and propagation of CSCs. Deciphering the intricate interplay between CSCs and immune cells would provide valuable insights into the mechanisms of CSCs being more susceptible to immune escape. This review will highlight the EV-mediated communications between CSCs and each immune cell lineage in the tumor microenvironment and explore potential therapeutic opportunities.

Keywords: cancer stem cells, extracellular vesicles, exosomes, immune cells, tumor microenvironment

Introduction

Cancer stem cells (CSCs), also known as tumor initiating (propagating) cells, despite constituting a relatively small population of the tumor cells, play a pivotal role in fueling tumor growth due to their self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation ability (1–4). This concept, introduced several decades ago, has stimulated extensive studies aimed at decoding the clinical observations through CSCs (5–9). Patients who show initial partial or complete remission through anti-cancer treatments by chemotherapy or radiation may eventually experience tumor relapse or metastasis, conditions that tend to be markedly intractable owing to the increased resistance to therapies (10, 11). This phenomenon is likely attributed to CSCs’ resilience against the therapeutic regimens. Besides, CSCs also contribute to intratumoral heterogeneity (ITH) by differentiating to all kinds of cancer cells with different phenotypic features, some of which can disseminate to other parts of the body (12–14).

CSCs intricately interact with cancer supporting cells especially immune cells in the tumor ecosystem, sculpting a conducive niche and employing mechanisms for immune evasion and immunosuppression, including activating immune escape pathways and suppressing antigen processing and presentation proteins (15). CSCs also overexpress programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) on the cell surface, an incredibly important immune checkpoint protein that counteract the antitumor immune response (16, 17). Unraveling how CSCs engage with cancer-associated immune cells is gaining increasing attention, as these interactions hold considerable potential as immunotherapeutic targets.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are small lipid bilayered membrane vesicles composing of two main subgroups, exosomes and microvesicles (MVs) (18–20). These vesicles range in size from a few tens of nanometers to multiple micrometers (21, 22). Secreted by all cell types, EVs are responsible for the transfer of functional biological cargos including nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids between cells, mediating critical intercellular communication (23, 24). EVs are irreplaceably involved in modulating various innate and adaptive immune processes including antigen presentation, activation of T cells and B cells (25–27). Within the tumor ecosystem, EV-mediated communication is preferentially characterized by EVs produced by CSCs being internalized by other cells, a process integral for the dissemination of CSC-specific traits, which is essential for shaping the tumor immune microenvironments. For example, pancreatic CSC-derived EVs carry agrin protein to increase YAP activation to promote tumor cell proliferation (28). EVs from colorectal CSC could transfer metastatic properties to the non-CSCs via miR-200c (29). CSC-derived EVs are likely to interact with immune cells enriched in the CSC niche, including MHC-II expressing macrophages and programmed cell death 1 (PD1) positive T cells, potentially promoting tumor progression through immunosuppression (30). Conversely, immune cell-derived EVs enhance CSC stemness and propagation (31–33). The reciprocal transfer of EVs between CSCs and immune cells operate in concert to create a tumor-supporting niche.

In this review, we will summarize and discuss the recent findings on the biological functions of CSC-derived EVs, with a focus on their immunological role through engagement with various types of tumor-associated immune cells, and how EV-mediated interactions between CSCs and immune cells contribute to shaping the tumor immune microenvironments.

Overview of CSCs

ITH is a major obstacle in cancer treatment, leading to aggressive tumor growth and treatment failures (34–36). Elucidating the sources of ITH is of great significance to overcome therapy resistance. ITH present in two forms, spatial heterogeneity, which involves the unequal distribution of tumor subpopulations across different regions, and temporal heterogeneity, which refers to genetic diversity within a tumor over time (34, 37). Technological advances such as multiregional sampling, liquid biopsy, single-cell sequencing, and spatial transcriptome provide insights into decoding the intricate compositions of ITH (38–40). Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of various types of tumors have uncovered distinct subpopulations of tumor cells, each characterized by varying levels of differentiation and stemness (41–44). Of note, various driving forces are emerging to be responsible for ITH, encompassing genome instability and clonal evolution (45, 46), metabolic adaptation (47), epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (48) as well as environmental factors such as hypoxia (49) and inflammation (50). Among these, the existence of CSCs plays a pivotal role in the development and maintenance of ITH (13, 51).

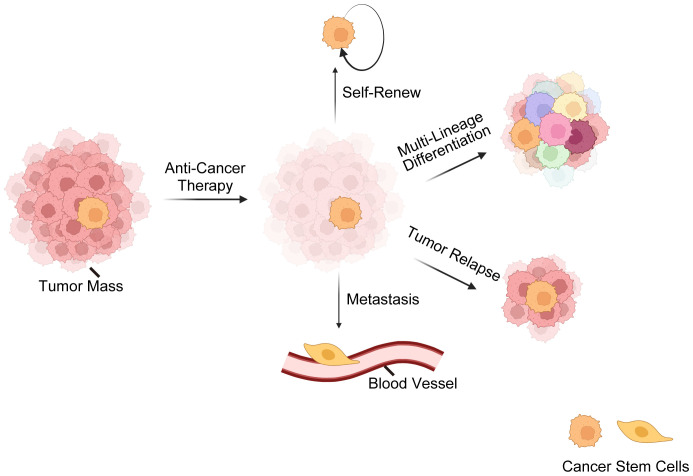

Here comes the concept of CSCs, a subset of tumor cells capable of self-renewal, tumor-initiating, multi-lineage differentiation, therapy-resistance, metastasis, relapse, etc. (7, 52–54) ( Figure 1 ). The CSC theory posits that tumors are hierarchically structured, with CSCs at the top (7, 55–57). Nevertheless, recent findings (2, 13, 58) have revealed that CSCs and non-CSCs are dynamic and can transition between states in response to specific stimuli, complicating tumor eradication. Initially identified in hematological malignancies, CSCs are now recognized in various solid cancers (59–62). Three hypotheses explain CSC origins (63, 64): transformation of non-cancerous stem cells through a series of oncogenic mutations (65), acquisition of pluripotency by progenitor cells (66), and dedifferentiation of differentiated cells (67).

Figure 1.

Overview of cancer stem cells (CSCs). This illustration delineates the fundamental characteristics of CSCs, encompassing their resilience against standard anti-cancer treatments. CSCs possess a remarkable ability for self-renewal, ensuring the perpetuation of the cancer cell population. CSCs are also capable of multi-lineage differentiation, which contributes to the cellular complexity and heterogeneity of tumors. Furthermore, CSCs are often implicated in tumor relapse due to their ability to remain dormant and then re-initiate tumor growth. Lastly, their role in metastasis is underscored by their potential to disseminate and form new tumors at distant sites, which is a hallmark of advanced cancer stages. These CSC characteristics are critical for understanding tumor behavior and developing targeted therapeutic strategies.

Certain surface markers such as CD133, CD44, epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM), and intracellular markers such as aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) have been identified for CSCs (68–72). ALDH is an enzyme mediating aldehyde detoxification, which is assessed by the ALDEFLUOR assay, is instrumental in drug resistance (73–75). However, these markers are not solely specific to CSCs, and some CSCs don’t exhibit these markers at all (9, 76, 77). Moreover, CSCs typically constitute less than 1% of the tumor mass, and such scarcity further complicates their isolation and identification (77).

Besides markers, the characterization of CSCs requires surrogate functional assays (78–80). Current well-known surrogate methods include in vitro tumorsphere formation and in vivo limiting-dilution tumorigenicity assays (81–83). In vitro tumorsphere formation assay evaluates the ability of cells to grow and form spheres in a three-dimensional, anchorage-independent culture environment (84, 85). In vivo limiting-dilution tumorigenicity assay, which tests the tumor-initiating capacity of cells by transplanting them into immunocompromised mice and observing tumor formation, is considered the gold standard for CSC research (86, 87).

CSCs contribute to therapy resistance through several mechanisms (88–90), including high levels of multi-drug efflux ATP-binding cassette transporters, slow-cycling state, enhanced DNA repair capacity, apoptosis evasion, immune-privileged property, etc. Furthermore, EMT activation is tightly associated with the formation of CSCs (91). Consequently, CSCs consist of heterogenous subtypes occupying different locations and exhibiting varied EMT characteristics within the primary tumor (92, 93), further complicating their therapy resistance.

Additionally, it is important to emphasize that CSCs have been found to actively reshape the tumor microenvironment into immunosuppressive state, facilitating their own growth and proliferation while evading the therapeutic elimination (15, 94, 95). This interaction is significantly mediated by EVs, powerful cell-cell communicators that plays a crucial role in modulating the immune microenvironment (96). Through EVs, CSCs transferring a diverse array of biological cargos to surrounding or distant immune cells, eliciting immunosuppressive responses that protects CSCs and fosters tumor progression (28).

The landscape of EVs: classifications and molecular constituents

EVs are lipid-bilayer membrane structures secreted by virtually all living cells, encompassing two main subtypes, exosomes and MVs, whose sizes ranging from about 50 nm to 5 µm (97, 98) ( Figure 2 ). EVs contain cellular bioactive components like proteins, lipids, metabolites, and nucleic acids, reflecting their cell of origin and functioning as mediators of intercellular communication (99, 100). EVs perform multifaceted functions including waste disposal, signal cargo delivery to alter recipient cell physiology, and mediating interactions between cells and extracellular matrix (101–105). Furthermore, they can also facilitate long-distance communication via blood or lymph (106, 107). Separating different EV subtypes is challenging due to overlapping properties, with methods like differential centrifugation, size-exclusion chromatography, and immunoprecipitation used in combination to improve specificity (108).

Figure 2.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs). EVs encapsulate a diverse array of bioactive molecules, including surface proteins, cytosolic proteins, nucleic acids (both DNA and RNA), metabolites, lipids, and peptides. EVs are classified into exosomes and microvesicles based on origin of formation and their size.

Exosomes stand out as the most well-studied subtype of EVs with a size ranging between 40–160nm, primarily due to their unique biogenesis, small size, and specific molecular content (109). Exosomes play a pivotal role in cellular communication and cancer research. Originating from endosomal compartments within cells, they carry an array of biomolecules which reflect their cellular origin and can influence recipient cell behavior. This makes them key players in tumor progression and ideal for targeted drug delivery and biomarker discovery in cancer diagnostics and therapeutics (110–112). Their small size, specific content, and stability in bodily fluids enhance their potential, making them promising candidates in the medical and scientific exploration of cancer.

Contrasting with exosomes, which originate from endosomal pathways, MVs are formed by budding directly off the plasma membrane and are generally larger, with sizes spanning from 200–5000 nm (97, 113). MVs refer to a diverse group of membrane-derived vesicles, including microparticles, oncosomes, or ectosomes, and is less characterized EV subtype whose cargo trafficking mechanisms are still under investigation (114). Besides functional cargos as RNAs, proteins, lipids, and metabolites, MVs could also mediate the transfer of mitochondria between cells (115), which boosts ATP production in the recipient cells. Studies have shown that cancer cell-derived MVs participate in tumor progression (116, 117), while MVs from radiation treated cancer cells exert antitumor effect through immunogenic death pathway (118). These findings suggest a promising functional role of MVs in cancer therapeutics.

CSC-derived EVs in oncogenic events

EVs generated from CSCs are instrumental in enhancing tumorigenesis, advancing metastasis, and fostering therapy resistance across various types of cancers by transferring associated vicious traits indicative of donor cell (29, 119–122) ( Table 1 ). Colorectal CSCs secrete EVs enriched with glycoprotein CD147 can subsequently trigger signaling pathways associated with tumorigenesis in recipient cancer cells (128). Besides, miR-200c in EVs from colorectal CSCs could convey metastatic traits to accelerate tumor progression (29). In triple-negative breast cancer, CSCs release EVs that can stimulate specific cancer-associated fibroblasts and remodel endothelial cells, accelerating invasiveness and preparing distant metastatic niches (129). Lung CSCs could transfer their strong metastatic properties to the whole tumor mass through exosomal lncRNA Mir100hg/miR-15a-5p/glycolysis pathway (130). Gastric CSCs induce tumor cells to gain malignant and metastatic behaviors and stemness features via EVs internalization (131), possibly due to a gastric CSCs marker gene DCLK1, which could transfer the migratory property to the recipients (132). Melanoma CSCs secrete EVs that enhance metastatic ability of non-stem cancer cells via miRNA-592, which activates the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway (125). Breast CSC-derived EVs carry ARRDC1-AS1 to promote breast cancer malignancy by modulating miR-4731–5p/AKT1 axis to foster tumor growth and aggressiveness (123). In addition, CSCs secrete certain tumor suppressors out the cells by EVs. Acute myeloid leukemia stem cells secrete more miR-34c-5p out to attenuate senescence through RAB27B-mediated exosome trafficking (133).

Table 1.

CSC-derived EVs in oncogenic events.

| Cancer type | EV cargo | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | ARRDC1-AS1 | Promote the malignant progressive phenotypes via the miR-4731–5p/AKT1 axis. | (123) |

| miR-197 | Promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition thus increase BC cells proliferation and metastasis | (124) | |

| HNSCC | _ | EVs have a selective impact on specific immune cells to modulate anti-cancer immune response | (30) |

| Pancreatic cancer | Agrin protein | Promote YAP activity via LRP-4 to contribute to tumor progression | (28) |

| Melanoma | miR-592 | Increase the metastatic ability of MPCs via miR-592/PTPN7/MAPK axis | (125) |

| Colorectal cancer | miR-200c | Enhance invasion, metastasis and stemness associated with PI3K/Akt/mTOR activation | (29) |

| Ovarian cancer | _ | Promote the migration ability and pro-tumorigenic phenotype MSCs | (126) |

| NSCLC | APE1 shRNA | Reverse Erlotinib resistance of NSCLC via inhibiting IL-6/STAT3 signaling | (127) |

HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.Symbol “-” indicates that the corresponding study did not specify the function at the EV cargo level, but rather at the whole EV level.

EMT and angiogenesis are essential mechanisms of tumor metastasis (134, 135), with CSC-derived EVs engage in the regulation of these processes. Renal CSC-derived exosomes, carrying miR-19b-3p, trigger EMT in renal tumors and enhance distant metastasis (136). EVs from glioma CSCs containing vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) significantly boost angiogenesis and increase vascular permeability in brain endothelial cells, indicating significant contribution of CSC-derived EVs to the tumor’s vascular development (137, 138).

CSC secretome and immune modulation

The concept of secretome, now updated to extend beyond merely proteins, have led to the recognition of EVs as the nanostructured/microstructured secretome, composing a complex assembly of bioactive molecules with significant implications for intracellular communications and dynamics inside the tumor microenvironment (TME) (139–141). Furthermore, CSC secretome covers a diverse spectrum of bioactive molecules released out of cells, including various soluble factors like growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and proteins (142–144). Delineating the roles these secretome compositions play on immune interactions will provide an integrated understanding of crosstalk between CSC and immune cells, setting the stage for the subsequent sections that focus on the specific roles of EVs in this interplay.

CSC secretome has profound impact on tumor growth and TME modulation ( Table 2 ). Secretome profiles of melanoma CSCs include proteins enriched with cell proliferation, cell survival and negative regulation of apoptosis (145). Breast CSCs actively secrete CXCL1, a chemokine that plays a crucial role in stimulating their proliferation and enhancing their capacity for self-renewal, contributing significantly to the progression and aggressiveness of breast cancer (146). Glioma CSCs generate and release immune cytokines such as soluble colony-stimulating factor (sCSF-1), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, C-C motif chemokine 2 (CCL2), VEGF, macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 (MIC-1), and galectin-3 into TME, contributing to the suppression of innate immunity characterized by the induction of immunosuppressive macrophages and regulatory T cells and effector T cell apoptosis (147, 148). CSCs release macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), which binds with C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2) presenting on myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSCs), leading to production of arginase 1, thereby suppressing CD8+ T cells (150). Also, previous studies revealed that the glioma CSCs could trigger B7-H4 expression in both tumor and immune cells through IL6-STAT3 pathway activation and stimulate PD-L1 expression within the TME (147, 149). These cytokines, chemokines and immune checkpoint proteins work synergistically to lead to immunosuppression.

Table 2.

Biological functions of CSC secretome.

| Donor cell | Secreted molecules | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma CSCs | Proteins related to cell proliferation and survival | Sustain cell survival, while Theo supplement induce CSC differentiation | (145) |

| Breast CSCs | CXCL1 | Stimulate CSC proliferation and enhance self-renewal | (146) |

| Glioma CSCs | sCSF-1, TGF-β1, CCL2, VEGF, MIC-1, galectin-3 |

Induce phenotypes of Treg and immunosuppressive macrophage, and stimulate effector T cell apoptosis | (147–149) |

| MIF | Suppress CD8+ T cell activity | (150) |

Exploring EV-mediated interactions between CSCs and immune cells in the TME: implications for tumor immunity

The TME is a complex and dynamic battlefield consisting of cancer cells, CSCs and cancer supporting cells, serving as a critical zone for the interplay between immune cells and CSCs ( Figure 3A ). This environment is a hub where diverse immune cells from both innate and adaptive immune systems converge (151, 152). Dendritic cells (DCs) are key in antigen presentation and the initiation of immune responses, while macrophages, also involved in antigen presentation, display ambiguous effects on tumors by either fostering or inhibiting their growth. MDSCs predominantly suppress immune activity, facilitating tumor immune evasion. Natural killer (NK) cells, adept at autonomously destroying cancer cells, and neutrophils, whose impact on cancer can vary from hindering to promoting tumor progression. In terms of the T cell population, subsets including cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are directly responsible for recognizing and eradicating cancer cells, highlighting their critical role in antitumor immunity. T helper 17 (Th17) cells, a subset of CD4+ helper T cells, known for their secretion of interleukin-17 (IL-17), exhibit a dual role in cancer by either promoting inflammation that can support tumor growth or recruiting effector T cells, NK cells and DCs into TME that enhance antitumor responses.

Figure 3.

Crosstalk between CSCs and immune cells through EVs within tumor microenvironment (TME). (A) TME composition. The tumor ecosystem encompasses a diversity of cell types including cancer cells, CSCs, immune cells, and non-cellular component like extracellular matrix and blood vessels, all of which are integral to TME. (B) The effect of EVs on CSCs and immune cells. These EVs transport biological signals that prime immune cells to undergo various functional alterations such as immunosuppressive phenotype acquisition, cytotoxicity inhibition and DC activation, and in turn, immune cells exert certain influence on CSCs such as promotion of growth and metastasis. CSC, cancer stem cell. NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps. DC, dendritic cell. MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell. Some elements in Figures 1 – 3 were created with BioRender.com.

Mounting evidence have shown that EVs released by cancer cells, especially CSCs, are capable in modulating both innate and adaptive immune responses, thereby facilitating to establish pro-tumorigenic and pro-metastatic immune niches through their interactions with various immune cell types within TME (153–156). Understanding the diverse functions and interactions of these immune cells with CSCs through EVs provides insight into the complex nature of cancer and opens avenues for innovative therapeutic strategies ( Figure 3B , Table 3 ).

Table 3.

EV communications between CSCs and immune cells.

| Donor cell | Recipient cell | EV cargo | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glioblastoma CSCs | Macrophages | STAT3 pathway components | Induce M2 macrophage phenotype | (157) |

| Oral CSCs | Macrophages | lncRNA UCA1 | Induce M2 macrophage phenotype | (158) |

| HNSCC | M2 macrophage and PD1+ T cells | — | Promote immune evasion | (30) |

| Macrophages | Pancreatic CSCs | miR-21–5p | Promote CSC stemness | (33) |

| Macrophages | Ovarian CSCs | IL-6, IL-10 | Promote CSC proliferation | (31) |

| Colon CSCs | DCs | Activate T cell proliferation | (159) | |

| Renal CSCs | DCs and T cells | HLA-G | Inhibit DC maturation and T cell function | (160) |

| Colon CSCs | Neutrophils | Tri-phosphate RNAs | Sustain neutrophil survival and recruit them to advance cancer progression | (161) |

| Melanoma CSCs | Neutrophils | — | Increase pro-tumor effect of neutrophils | (162) |

| MDSCs | Ovarian, breast and pancreatic CSCs | — | Promote CSC stemness and propagation | (163–165) |

| MDSCs | Colorectal CSCs | S100A9 | Promote CSC stemness and survival | (32) |

| Esophageal CSCs | T cells | OGT | Increase PD-1 in T cells to be immunosuppressive | (166) |

| HNSCC CSCs | PD1+ T cells | — | Promote immune escape | (30) |

| Brain CSCs | T cells | tenascin-C | Inhibit T cell-induced immune response | (167) |

| Colorectal CSCs | T cells | miRNA-146a-5p | Decrease CD8+ T cell infiltration | (168) |

| Glioma CSCs | T cells | — | Inhibit T cell proliferation, activation and Th1 cytokine production | (169) |

Symbol “-” indicates that the corresponding study did not specify the function at the EV cargo level, but rather at the whole EV level.

Macrophage

Tumor-associated macrophages are a diverse group of macrophages usually originating from circulating monocytes, recruited to TME (170). In some solid tumors, macrophages can constitute more than 50% of the tumor mass (171, 172), and the abundance of infiltrated macrophages usually associated with distinct clinical prognosis (173). Contrary to the notion of them being a homogenous population, macrophages exhibit a wide range of behaviors and characteristics, influenced by the specific type, stage, and immune context of the tumors they infiltrate (174). This variability extends to their roles, which are generally categorized into two subpopulations: classically activated (M1 or M1-like) and alternatively activated (M2 or M2-like) macrophages (175). Macrophages engage in mutual interactions with tumor cells and other cells like platelets, neutrophils, and various T cells, while also suppressing NK and CD8+ T cell activation. These interactions present numerous targets for therapies aimed at promoting an anti-tumor response (176). Emerging research has unveiled intricate communication pathways involving CSC-derived EVs that orchestrate a complex interplay with macrophages in various cancer types, profoundly supporting the immunosuppressive microenvironment and tumor progression (30, 157, 158).

CSC-derived EVs promote macrophage to exhibit M2 phenotype. Glioblastoma CSC-generated exosomes (GDEs) preferentially target monocytes to promote their conversion into immunosuppressive M2 macrophages within TME, a process characterized by upregulated PD-L1 expression due to the components of the STAT3 pathway carried by these GDEs (157). Oral squamous CSC-derived small EVs transport the lncRNA UCA1 which, by sequestering miR-134, modulates the PI3K/AKT pathway via LAMC2 to drive macrophages toward an immunosuppressive M2 phenotype, thus promoting tumor growth and inhibiting T-cell function (158). CSC-derived EVs in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) specifically interact with M2 macrophages and PD1+ T cells, crucial immune constituents enriched in CSC niche, contributing to immunosuppression landscape that impedes effective HNSCC therapy (30).

The EV communication routes can be bidirectional and reciprocal between CSCs and macrophages, with M2 macrophage-derived EVs enhancing the tumorigenic potential of pancreatic CSCs. This enhancement is mediated through the transfer of miR-21–5p, which suppresses KLF3 expression to promote stemness (33). Furthermore, activated M2 macrophages promote ovarian CSC propagation through IL-6 and IL-10 cytokine secretion in TME (31).

DC

DCs, as professional antigen-presenting cells, play a pivotal role in the immune response within the TME. They are essential in capturing foreign antigens and presenting them to T cells via multiple ways including direct, cross-presentation and cross-dressing (177), thereby activating the adaptive immune system to mount an effective killing against tumors. Specifically, EVs also have the capacity to deliver tumor antigens to DCs, a phenomenon known as cross-dressing, which has garnered significant recent attention in research (178). DCs can activate T cell proliferation by co-culture with colon CSC-derived exosomes, possibly due to the increased ratio of IL-12 to IL-10 (159).

However, the cargo of CSC-derived EVs not only transfer tumor antigens for immune activation but deliver a diversity array of functional cargo that actively hinder DC function as well. A study focusing on renal CSC-derived EVs, particularly those expressing CD105, significantly disrupt the maturation of monocyte-derived DCs and the activation of T cells. Notably, this disruption is more pronounced than the situations in non-stem tumor cells. This immune escape effect is largely attributed to the expression of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-G by the CSCs, which is then packaged and released by EVs (160).

Neutrophil

Neutrophils are pivotal immune cells within TME that exhibit both tumor-inhibiting and tumor-promoting actions, including the stimulation of tumor growth, angiogenesis, tissue invasion, and metastasis. Neutrophils can also undermine the immune system’s response to cancer by recruiting regulatory T cells and suppressing the activity of natural killer cells, highlighting their significance as potential therapeutic targets in the treatment of cancer (179, 180). Colorectal CSC-derived exosomes carry tri-phosphate RNAs which are capable of inducing the expression of IL-1β in neutrophils, sustaining their prolonged survival through a pattern recognition-NF-κB signaling axis (161). The primed neutrophils are subsequently attracted to the TME by CXCL1 and CXCL2, advancing the progression of colorectal cancer (161).

As the hallmarks of protumor N2 neutrophils, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are networks composed of extracellular DNA fibers decorated with granule proteins that are released by neutrophils, which can trap and kill foreign pathogens (181–183). In recent years, it has been acknowledged that NETs play a tumor-promoting role in cancer and facilitate the progression and metastasis by trapping cancer cells (184, 185). The secreted factors or EVs of melanoma CSCs increase the formation of NETs, which in turn reinforce the stemness properties of CSCs (186). NETs are implicated in enhancing CSC-like features and fostering the transition to EMT state in breast cancer (162).

MDSC

As immunosuppressive cells, MDSCs represent a heterogeneous population of immature cells recognized for their capacity to impede T cell responses and facilitate the advancement of cancer (187, 188).

MDSCs have the ability of increasing CSC population and promoting stemness properties. MDSCs could induce the formation of CSCs, sustain their survival and propagation, and enhance the metastatic growth of tumors (189). MDSCs could increase stemness of ovarian CSCs by inducing miRNA101 expression in CSCs (163). For breast cancer, elevated stem-like properties were observed with the IL-6-STAT3 pathway activation in MDSCs, and the degree of MDSC infiltration positively correlated with the number of CSCs (165). In pancreatic cancer, activation of pSTAT3 in MDSC could increase CSC population and promote EMT (164).

Current studies suggest that EVs originating from MDSCs and CSCs could serve as mutual catalysts, amplifying each other’s functional capabilities in a reciprocal manner. In colorectal cancer, MDSCs also sustain the survival and stemness of CSCs due to the exosomal S100A9 released from MDSCs (32). Glioma CSC-derived exosomes promote the presence of monocytic MDSCs, by stimulated the expression of arginase-1 and IL-10 in immature CD14+ monocytes (169).

T cell

In immune defense against cancer, T cells, particularly CTLs, also cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, are critical for cancer detection and eradication. CD4+ T cells support this process by promoting the activation and growth of CD8+ T cells and can sometimes directly target tumor cells themselves, thus also playing a vital role in the efficacy of cancer immunotherapies (190).

CSC-derived EVs contribute to immune evasion in cancer by suppressing T cell functions. Renal CSC-derived EVs have been proven to significantly hinder T cell activation and proliferation, primarily owing to HLA-G secretion, contrast to EVs from non-stem renal cancer cells (160). The investigation into the impact of EVs derived from esophageal CSCs on T cell dynamics revealed that EVs overload O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (O-GlcNAc transferase, OGT). Upon uptake by neighboring CD8+ T cells, OGT within these EVs leads to an increased expression of PD-1 in the T cells, and shield CSCs from immune-mediated destruction, thereby contributing to the immune evasion (166). In HNSCC, CSC-derived EVs specifically interact with PD1+ T cell, suggesting a direct involvement in modulating T cell behavior which plays a crucial role in cancer immune evasion mechanism (30). In addition, extracellular matrix protein tenascin-C in EVs from brain CSCs can inhibit T cell immunity (167). For colorectal CSCs, miRNA-146a-5p in their exosomes has a notable impact on the distribution of T cells in cancer patients. Specifically, patients with higher levels of serum exosomal miR-146a-5p showed fewer number of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells (168)

CSC-derived exosomes have a selective impact on different T cell subtypes. In glioma, EVs from CSCs suppress activation, proliferation, and Th1 cytokine production in effector T cells, while regulatory T cells remain largely unaffected. Notably, these exosomes enhance the proliferation of CD4+ T cells, illustrating their complex role in modulating immune responses in glioma (169). However, the effects of exosomes released by CSCs on other subsets of T helper cells such as Th17 cells have yet to be understood.

Developing EV-based anti-cancer immunotherapeutic strategies

EVs are favored for therapeutic delivery due to their superior biocompatibility and ability to penetrate biological barriers (191, 192). These years, EVs have been developed as targeted delivery systems to disrupt CSC functions by transporting RNA-based therapeutics into CSCs. EVs can be engineered to carry siRNAs that target key signaling pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin in liver cancer, leading to the suppression of CSC proliferation (193). In non-small cell lung cancer, EVs delivering APE1 shRNA have demonstrated potential in overcoming drug resistance (127). Furthermore, EVs designed to silence genes can reduce resistance to sorafenib treatments in liver cancer, promising to enhance patients’ clinical outcomes (194).

Notably, researchers have been making persistent efforts to develop engineered EVs as immunotherapeutic strategies to combat immunosuppressive state fueling by cancer cells and immune cells (159, 195–198). Xu et al. has developed a bispecific EVs (BsEVs) engineered from DCs that target tumor antigen CD19 on tumor cells and block the PD-1 checkpoint, thus bolstering cancer immunotherapy (197). These BsEVs show remarkable tumor-homing capabilities and can substantially remodel the tumor’s immune landscape, demonstrating their potential in personalized and versatile cancer treatments. Innovatively, chimeric exosomes, produced by M1 macrophage-tumor hybrid cells, naturally targeting to lymph nodes and tumors, enhancing T cell response, and overcoming immunosuppression. This dual-action immunostimulatory exosome strategy can alleviate tumors and enhance survival in animal studies and shows potential in personalized immunotherapy, especially when used with PD-1 inhibitors (199). Moreover, a dual-functional exosome delivery system that employs bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes loading with galectin-9 siRNA and the immunogenic cell death trigger oxaliplatin, promises to enhance immunotherapy. This system aims to achieve win-win idea of both counteracting the immunosuppressive actions of M2 macrophages and simultaneously improving tumor targeting (200).

However, the immunotherapeutic approaches using EVs to target CSCs is still in its early stage and requires further in-depth and comprehensive research. Naseri et al. established a DC-based therapeutic strategy using colon CSC-derived exosomes as antigen sources, aiming to increase proliferation and activation of T cells specifically for killing CSCs (159). Besides leverage EVs for support, disrupting the interactions of CSC-derived EVs with macrophages emerges as a potential therapeutic choice. Colon CSC-derived exosomes, containing molecules like IL-6, p-STAT3, TGF-β1, and beta-catenin, are known to promote the generation of cancer-associated fibroblasts and M2 macrophages. Ovatodiolide, a bioactive compound, has been found to reduce these harmful components in exosomes, consequently weakening chemotherapy resistance (201). This suggest that ovatodiolide could serve as an effective agent against colon cancer through disrupting the exosomal supply CSCs provide to immunosuppressive cells.

Future directions for targeting CSCs and the tumor immune microenvironment are pointed to be focused on integrating EVs with cutting-edge cancer therapeutic strategies, such as differentiation therapy and synthetic lethality, aiming to provide more effective and precise cancer treatments. Differentiation therapy is an innovative approach that exploits the plasticity of CSCs by inducing them to differentiate into less malignant, more differentiated cells, making them more susceptible to cytotoxic drugs (202, 203). Acting as biocompatible natural carriers, EVs are promising to be engineered to deliver differentiation-inducing and immune activating molecules to target CSCs and immune microenvironment, thereby synergistically eliminating refractory CSC pool. Synthetic lethality (SL) is defined as the simultaneous inactivation of two genes lead to cell death, whereas the loss of either gene alone is not lethal (204, 205). A prime example is the use of PARP inhibitors in combination with BRCA1/2 mutations, which results in the targeted death of cancer cells (206). Multifunctional engineered EVs present a promising delivery mechanism for SL-based therapy, as co-delivering multiple therapeutic agents that target separate pathways essential CSC survival and immune responding within the same EVs can enhance the efficacy of SL approaches. To conclude, EV-based therapies offer a versatile and targeted approach to treating cancer by addressing both CSCs and the tumor immune microenvironment.

Discussion

CSCs have been recognized as crucial targets in oncology due to their irreplaceable roles in tumor growth, metastasis, and the potential for developing more effective cancer therapies by disrupting CSC-specific pathways. The interaction between CSCs and immune cells significantly influences cancer progression, offering therapeutic avenues to modify the immune environment and exploit immune cells for CSC eradication. EVs, as masters of intercellular communication, not only shed light on the complex dynamics of cell interactions but also offer platforms for bioengineering as cutting-edge immunotherapeutic tools, harnessing their natural communication ability to modulate immune responses and precisely combat against CSCs. Specifically, compared with EVs derived from non-malignant stem cell such as mesenchymal stem cells which are known for regenerative and anti-inflammatory properties (207, 208), CSC-derived EVs possess superior cancer therapeutic capacities due to their inherent tumor-targeting specificity, tumor immune modulation activity, and higher uptake efficiency by cancer cells (209). These characteristics makes CSC-derived EVs exceptionally advantageous as potential mediators for cancer therapeutic payload delivery.

In this review, we have provided current research on EV-mediated communications of CSCs with individual subtype of immune cells in a wide spectrum of cancers. In terms of clinical translation, it is noteworthy that preclinical investigations into ovatodiolide have highlighted its potential as a disruptor of the deleterious feedback loop between CSCs and immunosuppressive macrophages, heralding an augmentation in the therapeutic efficacy for patients with colon cancer undergoing chemotherapy.

Despite the advancements discussed in our review, it is critical to emphasize that our understanding of the interactions between CSCs, EVs, and immune cells is still in its infancy. Especially understudied are the roles of NK cells, Th17 cells, and B cells in this tripartite communication, which is surprising given their crucial roles in the immune response to cancer. Take NK cells for example, as cytotoxic lymphocytes in the innate immune system, they possess the ability to eliminate cells infected by viruses or cancer cells (210). NK cells are powerful in cancer immunotherapy because of being able to swiftly attack cancer cells, thereby boosting both the immediate and long-term immune defense against tumors (211, 212). Previous studies (213–216) have found that while CSCs with reduced MHC-I expression and certain CSC markers can activate NK cells’ cytotoxic functions, leading to their effective elimination in various cancers, CSCs also employ numerous mechanisms to suppress NK cell-mediated immune responses, such as downregulating activation ligands or entering a dormant state to evade detection. This intricate dynamic between NK cells and CSCs suggests a potential role for EVs in mediating their interactions. Recognizing this, we advocate for a concerted effort to deepen the investigation into CSC-EV-immune cell interactions. Furthermore, the field of CSC research necessitates to advance precise isolation techniques that consider the heterogeneity of CSCs, including the development of comprehensive identification strategies including refined cell surface markers. Timely initiation of preclinical and clinical trials, grounded in laboratory findings, is imperative to substantiate the therapeutic efficacy and expedite the translation of research into improving patient survival and quality of life.

Author contributions

YJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CZ: Writing – review & editing. WY: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. XL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department Fundamental Research Funds for the Provincial Universities (No. JYT2024002), Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Hebei North University (No. BSJJ202401), and GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2021A1515110820) to XL.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Nassar D, Blanpain C. Cancer stem cells: basic concepts and therapeutic implications. Annu Rev Pathol. (2016) 11:47–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012615-044438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Batlle E, Clevers H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nat Med. (2017) 23:1124–34. doi: 10.1038/nm.4409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ohta Y, Fujii M, Takahashi S, Takano A, Nanki K, Matano M, et al. Cell-matrix interface regulates dormancy in human colon cancer stem cells. Nature. (2022) 608:784–94. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05043-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paul R, Dorsey JF, Fan Y. Cell plasticity, senescence, and quiescence in cancer stem cells: Biological and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol Ther. (2022) 231:107985. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clevers H. The cancer stem cell: premises, promises and challenges. Nat Med. (2011) 17:313–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beck B, Blanpain C. Unravelling cancer stem cell potential. Nat Rev Cancer. (2013) 13:727–38. doi: 10.1038/nrc3597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kreso A, Dick JE. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell. (2014) 14:275–91. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marks PW, Witten CM, Califf RM. Clarifying stem-cell therapy's benefits and risks. N Engl J Med. (2017) 376:1007–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1613723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clara JA, Monge C, Yang Y, Takebe N. Targeting signalling pathways and the immune microenvironment of cancer stem cells - a clinical update. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2020) 17:204–32. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0293-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cojoc M, Mabert K, Muders MH, Dubrovska A. A role for cancer stem cells in therapy resistance: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Semin Cancer Biol. (2015) 31:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li Y, Rogoff HA, Keates S, Gao Y, Murikipudi S, Mikule K, et al. Suppression of cancer relapse and metastasis by inhibiting cancer stemness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2015) 112:1839–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424171112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meacham CE, Morrison SJ. Tumour heterogeneity and cancer cell plasticity. Nature. (2013) 501:328–37. doi: 10.1038/nature12624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prasetyanti PR, Medema JP. Intra-tumor heterogeneity from a cancer stem cell perspective. Mol Cancer. (2017) 16:41. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0600-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Steinbichler TB, Savic D, Dudas J, Kvitsaridze I, Skvortsov S, Riechelmann H. Cancer stem cells and their unique role in metastatic spread. Semin Cancer Biol. (2020) 60:148–56. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Prager BC, Xie Q, Bao S, Rich JN. Cancer stem cells: the architects of the tumor ecosystem. Cell Stem Cell. (2019) 24:41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu Y, Chen M, Wu P, Chen C, Xu ZP, Gu W. Increased PD-L1 expression in breast and colon cancer stem cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. (2017) 44:602–4. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hsu JM, Xia W, Hsu YH, Chan LC, Yu WH, Cha JH, et al. STT3-dependent PD-L1 accumulation on cancer stem cells promotes immune evasion. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:1908. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04313-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stahl PD, Raposo G. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes and microvesicles, integrators of homeostasis. Physiol (Bethesda). (2019) 34:169–77. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00045.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wortzel I, Dror S, Kenific CM, Lyden D. Exosome-mediated metastasis: communication from a distance. Dev Cell. (2019) 49:347–60. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Couch Y, Buzas EI, Di Vizio D, Gho YS, Harrison P, Hill AF, et al. A brief history of nearly EV-erything - The rise and rise of extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. (2021) 10:e12144. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ratajczak MZ, Ratajczak J. Extracellular microvesicles/exosomes: discovery, disbelief, acceptance, and the future? Leukemia. (2020) 34:3126–35. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-01041-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Niel G, Carter DRF, Clayton A, Lambert DW, Raposo G, Vader P. Challenges and directions in studying cell-cell communication by extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2022) 23:369–82. doi: 10.1038/s41580-022-00460-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jeppesen DK, Fenix AM, Franklin JL, Higginbotham JN, Zhang Q, Zimmerman LJ, et al. Reassessment of exosome composition. Cell. (2019) 177:428–445 e418. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mashouri L, Yousefi H, Aref AR, Ahadi AM, Molaei F, Alahari SK. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis, and mechanisms in cancer metastasis and drug resistance. Mol Cancer. (2019) 18:75. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0991-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buzas EI, Gyorgy B, Nagy G, Falus A, Gay S. Emerging role of extracellular vesicles in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. (2014) 10:356–64. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Robbins PD, Morelli AE. Regulation of immune responses by extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Immunol. (2014) 14:195–208. doi: 10.1038/nri3622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lindenbergh MFS, Stoorvogel W. Antigen presentation by extracellular vesicles from professional antigen-presenting cells. Annu Rev Immunol. (2018) 36:435–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ruivo CF, Bastos N, Adem B, Batista I, Duraes C, Melo CA, et al. Extracellular Vesicles from Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells Lead an Intratumor Communication Network (EVNet) to fuel tumour progression. Gut. (2022) 71:2043–68. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tang D, Xu X, Ying J, Xie T, Cao G. Transfer of metastatic traits via miR-200c in extracellular vesicles derived from colorectal cancer stem cells is inhibited by atractylenolide I. Clin Transl Med. (2020) 10:e139. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gonzalez-Callejo P, Guo Z, Ziglari T, Claudio NM, Nguyen KH, Oshimori N, et al. Cancer stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles preferentially target MHC-II-macrophages and PD1+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment. PloS One. (2023) 18:e0279400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Raghavan S, Mehta P, Xie Y, Lei YL, Mehta G. Ovarian cancer stem cells and macrophages reciprocally interact through the WNT pathway to promote pro-tumoral and Malignant phenotypes in 3D engineered microenvironments. J Immunother Cancer. (2019) 7:190. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0666-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Y, Yin K, Tian J, Xia X, Ma J, Tang X, et al. Granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote the stemness of colorectal cancer cells through exosomal S100A9. Adv Sci (Weinh). (2019) 6:1901278. doi: 10.1002/advs.201901278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chang J, Li H, Zhu Z, Mei P, Hu W, Xiong X, et al. microRNA-21–5p from M2 macrophage-derived extracellular vesicles promotes the differentiation and activity of pancreatic cancer stem cells by mediating KLF3. Cell Biol Toxicol. (2022) 38:577–90. doi: 10.1007/s10565-021-09597-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dagogo-Jack I, Shaw AT. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2018) 15:81–94. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lauko A, Lo A, Ahluwalia MS, Lathia JD. Cancer cell heterogeneity & plasticity in glioblastoma and brain tumors. Semin Cancer Biol. (2022) 82:162–75. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gavish A, Tyler M, Greenwald AC, Hoefflin R, Simkin D, Tschernichovsky R, et al. Hallmarks of transcriptional intratumour heterogeneity across a thousand tumours. Nature. (2023) 618:598–606. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06130-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang J, Cazzato E, Ladewig E, Frattini V, Rosenbloom DI, Zairis S, et al. Clonal evolution of glioblastoma under therapy. Nat Genet. (2016) 48:768–76. doi: 10.1038/ng.3590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Math M, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. (2012) 366:883–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rodriguez-Meira A, Buck G, Clark SA, Povinelli BJ, Alcolea V, Louka E, et al. Unravelling intratumoral heterogeneity through high-sensitivity single-cell mutational analysis and parallel RNA sequencing. Mol Cell. (2019) 73:1292–1305 e1298. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lewis SM, Asselin-Labat ML, Nguyen Q, Berthelet J, Tan X, Wimmer VC, et al. Spatial omics and multiplexed imaging to explore cancer biology. Nat Methods. (2021) 18:997–1012. doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01203-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Patel AP, Tirosh I, Trombetta JJ, Shalek AK, Gillespie SM, Wakimoto H, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science. (2014) 344:1396–401. doi: 10.1126/science.1254257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Neftel C, Laffy J, Filbin MG, Hara T, Shore ME, Rahme GJ, et al. An integrative model of cellular states, plasticity, and genetics for glioblastoma. Cell. (2019) 178:835–849 e821. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ocasio JK, Babcock B, Malawsky D, Weir SJ, Loo L, Simon JM, et al. scRNA-seq in medulloblastoma shows cellular heterogeneity and lineage expansion support resistance to SHH inhibitor therapy. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:5829. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13657-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. van Galen P, Hovestadt V, Wadsworth Ii MH, Hughes TK, Griffin GK, Battaglia S, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals AML hierarchies relevant to disease progression and immunity. Cell. (2019) 176:1265–1281 e1224. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bakhoum SF, Landau DA. Chromosomal instability as a driver of tumor heterogeneity and evolution. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. (2017) 7. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a029611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Raynaud F, Mina M, Tavernari D, Ciriello G. Pan-cancer inference of intra-tumor heterogeneity reveals associations with different forms of genomic instability. PloS Genet. (2018) 14:e1007669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Badr CE, Silver DJ, Siebzehnrubl FA, Deleyrolle LP. Metabolic heterogeneity and adaptability in brain tumors. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2020) 77:5101–19. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03569-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Scheel C, Eaton EN, Li SH, Chaffer CL, Reinhardt F, Kah KJ, et al. Paracrine and autocrine signals induce and maintain mesenchymal and stem cell states in the breast. Cell. (2011) 145:926–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Terry S, Engelsen AST, Buart S, Elsayed WS, Venkatesh GH, Chouaib S. Hypoxia-driven intratumor heterogeneity and immune evasion. Cancer Lett. (2020) 492:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lujambio A, Akkari L, Simon J, Grace D, Tschaharganeh DF, Bolden JE, et al. Non-cell-autonomous tumor suppression by p53. Cell. (2013) 153:449–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hong D, Fritz AJ, Zaidi SK, Van Wijnen AJ, Nickerson JA, Imbalzano AN, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cells contribute to breast cancer heterogeneity. J Cell Physiol. (2018) 233:9136–44. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Plaks V, Kong N, Werb Z. The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell. (2015) 16:225–38. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vlashi E, Pajonk F. Cancer stem cells, cancer cell plasticity and radiation therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. (2015) 31:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Taniguchi S, Elhance A, Van Duzer A, Kumar S, Leitenberger JJ, Oshimori N. Tumor-initiating cells establish an IL-33-TGF-beta niche signaling loop to promote cancer progression. Science. (2020) 369. doi: 10.1126/science.aay1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Clarke MF, Dick JE, Dirks PB, Eaves CJ, Jamieson CH, Jones DL, et al. Cancer stem cells–perspectives on current status and future directions: AACR Workshop on cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. (2006) 66:9339–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vermeulen L, Sprick MR, Kemper K, Stassi G, Medema JP. Cancer stem cells–old concepts, new insights. Cell Death Differ. (2008) 15:947–58. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shibue T, Weinberg RA. EMT, CSCs, and drug resistance: the mechanistic link and clinical implications. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2017) 14:611–29. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gupta PB, Fillmore CM, Jiang G, Shapira SD, Tao K, Kuperwasser C, et al. Stochastic state transitions give rise to phenotypic equilibrium in populations of cancer cells. Cell. (2011) 146:633–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chen J, Li Y, Yu TS, Mckay RM, Burns DK, Kernie SG, et al. A restricted cell population propagates glioblastoma growth after chemotherapy. Nature. (2012) 488:522–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Driessens G, Beck B, Caauwe A, Simons BD, Blanpain C. Defining the mode of tumour growth by clonal analysis. Nature. (2012) 488:527–30. doi: 10.1038/nature11344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Schepers AG, Snippert HJ, Stange DE, Van Den Born M, Van Es JH, Van De Wetering M, et al. Lineage tracing reveals Lgr5+ stem cell activity in mouse intestinal adenomas. Science. (2012) 337:730–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1224676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jones CL, Inguva A, Jordan CT. Targeting energy metabolism in cancer stem cells: progress and challenges in leukemia and solid tumors. Cell Stem Cell. (2021) 28:378–93. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bjerkvig R, Tysnes BB, Aboody KS, Najbauer J, Terzis AJ. Opinion: the origin of the cancer stem cell: current controversies and new insights. Nat Rev Cancer. (2005) 5:899–904. doi: 10.1038/nrc1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dang HT, Budhu A, Wang XW. The origin of cancer stem cells. J Hepatol. (2014) 60:1304–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pattabiraman DR, Weinberg RA. Tackling the cancer stem cells - what challenges do they pose? Nat Rev Drug Discovery. (2014) 13:497–512. doi: 10.1038/nrd4253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hen O, Barkan D. Dormant disseminated tumor cells and cancer stem/progenitor-like cells: Similarities and opportunities. Semin Cancer Biol. (2020) 60:157–65. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Walcher L, Kistenmacher AK, Suo H, Kitte R, Dluczek S, Strauss A, et al. Cancer stem cells-origins and biomarkers: perspectives for targeted personalized therapies. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:1280. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Shigdar S, Qiao L, Zhou SF, Xiang D, Wang T, Li Y, et al. RNA aptamers targeting cancer stem cell marker CD133. Cancer Lett. (2013) 330:84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nguyen PH, Giraud J, Chambonnier L, Dubus P, Wittkop L, Belleannee G, et al. Characterization of biomarkers of tumorigenic and chemoresistant cancer stem cells in human gastric carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. (2017) 23:1586–97. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Han J, Won M, Kim JH, Jung E, Min K, Jangili P, et al. Cancer stem cell-targeted bio-imaging and chemotherapeutic perspective. Chem Soc Rev. (2020) 49:7856–78. doi: 10.1039/D0CS00379D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Nimmakayala RK, Leon F, Rachagani S, Rauth S, Nallasamy P, Marimuthu S, et al. Metabolic programming of distinct cancer stem cells promotes metastasis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. (2021) 40:215–31. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-01518-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Bu J, Zhang Y, Wu S, Li H, Sun L, Liu Y, et al. KK-LC-1 as a therapeutic target to eliminate ALDH(+) stem cells in triple negative breast cancer. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:2602. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38097-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lu J, Ye X, Fan F, Xia L, Bhattacharya R, Bellister S, et al. Endothelial cells promote the colorectal cancer stem cell phenotype through a soluble form of Jagged-1. Cancer Cell. (2013) 23:171–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kurani H, Razavipour SF, Harikumar KB, Dunworth M, Ewald AJ, Nasir A, et al. DOT1L is a novel cancer stem cell target for triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. (2022) 28:1948–65. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Tang DG. Understanding and targeting prostate cancer cell heterogeneity and plasticity. Semin Cancer Biol. (2022) 82:68–93. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zhou BB, Zhang H, Damelin M, Geles KG, Grindley JC, Dirks PB. Tumour-initiating cells: challenges and opportunities for anticancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. (2009) 8:806–23. doi: 10.1038/nrd2137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Agliano A, Calvo A, Box C. The challenge of targeting cancer stem cells to halt metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol. (2017) 44:25–42. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Dosch JS, Ziemke EK, Shettigar A, Rehemtulla A, Sebolt-Leopold JS. Cancer stem cell marker phenotypes are reversible and functionally homogeneous in a preclinical model of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. (2015) 75:4582–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Witt AE, Lee CW, Lee TI, Azzam DJ, Wang B, Caslini C, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell-specific function for the histone deacetylases, HDAC1 and HDAC7, in breast and ovarian cancer. Oncogene. (2017) 36:1707–20. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Jiao X, Velasco-Velazquez MA, Wang M, Li Z, Rui H, Peck AR, et al. CCR5 governs DNA damage repair and breast cancer stem cell expansion. Cancer Res. (2018) 78:1657–71. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Sun L, Huang C, Zhu M, Guo S, Gao Q, Wang Q, et al. Gastric cancer mesenchymal stem cells regulate PD-L1-CTCF enhancing cancer stem cell-like properties and tumorigenesis. Theranostics. (2020) 10:11950–62. doi: 10.7150/thno.49717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lai Y, Wang B, Zheng X. Limiting dilution assay to quantify the self-renewal potential of cancer stem cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Methods Cell Biol. (2022) 171:197–213. doi: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2022.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Yu H, Zhou L, Loong JHC, Lam KH, Wong TL, Ng KY, et al. SERPINA12 promotes the tumorigenic capacity of HCC stem cells through hyperactivation of AKT/beta-catenin signaling. Hepatology. (2023) 78:1711–26. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Johnson S, Chen H, Lo PK. In vitro tumorsphere formation assays. Bio Protoc. (2013) 3. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Gwynne WD, Shakeel MS, Wu J, Hallett RM, Girgis-Gabardo A, Dvorkin-Gheva A, et al. Monoamine oxidase-A activity is required for clonal tumorsphere formation by human breast tumor cells. Cell Mol Biol Lett. (2019) 24:59. doi: 10.1186/s11658-019-0183-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Vaillant F, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE. Jekyll or Hyde: does Matrigel provide a more or less physiological environment in mammary repopulating assays? Breast Cancer Res. (2011) 13:108. doi: 10.1186/bcr2851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Pinto MT, Ribeiro AS, Conde I, Carvalho R, Paredes J. The chick chorioallantoic membrane model: A new in vivo tool to evaluate breast cancer stem cell activity. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 22. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Gottesman MM, Fojo T, Bates SE. Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP-dependent transporters. Nat Rev Cancer. (2002) 2:48–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. (2005) 5:275–84. doi: 10.1038/nrc1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Li Y, Wang Z, Ajani JA, Song S. Drug resistance and Cancer stem cells. Cell Commun Signal. (2021) 19:19. doi: 10.1186/s12964-020-00627-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Lambert AW, Weinberg RA. Linking EMT programmes to normal and neoplastic epithelial stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer. (2021) 21:325–38. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00332-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Bocci F, Gearhart-Serna L, Boareto M, Ribeiro M, Ben-Jacob E, Devi GR, et al. Toward understanding cancer stem cell heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2019) 116:148–57. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1815345116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Zhao Y, Li ZX, Zhu YJ, Fu J, Zhao XF, Zhang YN, et al. Single-cell transcriptome analysis uncovers intratumoral heterogeneity and underlying mechanisms for drug resistance in hepatobiliary tumor organoids. Adv Sci (Weinh). (2021) 8:e2003897. doi: 10.1002/advs.202003897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Alvarado AG, Thiagarajan PS, Mulkearns-Hubert EE, Silver DJ, Hale JS, Alban TJ, et al. Glioblastoma cancer stem cells evade innate immune suppression of self-renewal through reduced TLR4 expression. Cell Stem Cell. (2017) 20:450–461 e454. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. He X, Smith SE, Chen S, Li H, Wu D, Meneses-Giles PI, et al. Tumor-initiating stem cell shapes its microenvironment into an immunosuppressive barrier and pro-tumorigenic niche. Cell Rep. (2021) 36:109674. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Buzas EI. The roles of extracellular vesicles in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. (2023) 23:236–50. doi: 10.1038/s41577-022-00763-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Van Niel G, D'angelo G, Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2018) 19:213–28. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Jeppesen DK, Zhang Q, Franklin JL, Coffey RJ. Extracellular vesicles and nanoparticles: emerging complexities. Trends Cell Biol. (2023) 33:667–81. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2023.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Yu W, Hurley J, Roberts D, Chakrabortty SK, Enderle D, Noerholm M, et al. Exosome-based liquid biopsies in cancer: opportunities and challenges. Ann Oncol. (2021) 32:466–77. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.01.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Zeng Y, Qiu Y, Jiang W, Shen J, Yao X, He X, et al. Biological features of extracellular vesicles and challenges. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2022) 10:816698. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.816698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Takahashi A, Okada R, Nagao K, Kawamata Y, Hanyu A, Yoshimoto S, et al. Exosomes maintain cellular homeostasis by excreting harmful DNA from cells. Nat Commun. (2017) 8:15287. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Pegtel DM, Gould SJ. Exosomes. Annu Rev Biochem. (2019) 88:487–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Yokoi A, Villar-Prados A, Oliphint PA, Zhang J, Song X, De Hoff P, et al. Mechanisms of nuclear content loading to exosomes. Sci Adv. (2019) 5:eaax8849. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax8849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Cheng L, Hill AF. Therapeutically harnessing extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. (2022) 21:379–99. doi: 10.1038/s41573-022-00410-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Dixson AC, Dawson TR, Di Vizio D, Weaver AM. Context-specific regulation of extracellular vesicle biogenesis and cargo selection. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2023) 24:454–76. doi: 10.1038/s41580-023-00576-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Cocucci E, Meldolesi J. Ectosomes and exosomes: shedding the confusion between extracellular vesicles. Trends Cell Biol. (2015) 25:364–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Lenzini S, Bargi R, Chung G, Shin JW. Matrix mechanics and water permeation regulate extracellular vesicle transport. Nat Nanotechnol. (2020) 15:217–23. doi: 10.1038/s41565-020-0636-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Cocozza F, Grisard E, Martin-Jaular L, Mathieu M, Thery C. SnapShot: extracellular vesicles. Cell. (2020) 182:262–262 e261. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Yokoi A, Ochiya T. Exosomes and extracellular vesicles: Rethinking the essential values in cancer biology. Semin Cancer Biol. (2021) 74:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Andaloussi SEL, Mager I, Breakefield XO, Wood MJ. Extracellular vesicles: biology and emerging therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. (2013) 12:347–57. doi: 10.1038/nrd3978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Han C, Yang J, Sun J, Qin G. Extracellular vesicles in cardiovascular disease: Biological functions and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol Ther. (2022) 233:108025. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.108025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Takahashi Y, Takakura Y. Extracellular vesicle-based therapeutics: Extracellular vesicles as therapeutic targets and agents. Pharmacol Ther. (2023) 242:108352. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Xu R, Greening DW, Zhu HJ, Takahashi N, Simpson RJ. Extracellular vesicle isolation and characterization: toward clinical application. J Clin Invest. (2016) 126:1152–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI81129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Clancy JW, Schmidtmann M, D'souza-Schorey C. The ins and outs of microvesicles. FASEB Bioadv. (2021) 3:399–406. doi: 10.1096/fba.2020-00127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. D'Souza A, Burch A, Dave KM, Sreeram A, Reynolds MJ, Dobbins DX, et al. Microvesicles transfer mitochondria and increase mitochondrial function in brain endothelial cells. J Control Release. (2021) 338:505–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.08.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Buentzel J, Klemp HG, Kraetzner R, Schulz M, Dihazi GH, Streit F, et al. Metabolomic profiling of blood-derived microvesicles in breast cancer patients. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22. doi: 10.3390/ijms222413540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Risha Y, Susevski V, Huttmann N, Poolsup S, Minic Z, Berezovski MV. Breast cancer-derived microvesicles are the source of functional metabolic enzymes as potential targets for cancer therapy. Biomedicines. (2021) 9. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9020107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Wan C, Sun Y, Tian Y, Lu L, Dai X, Meng J, et al. Irradiated tumor cell-derived microparticles mediate tumor eradication via cell killing and immune reprogramming. Sci Adv. (2020) 6:eaay9789. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aay9789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Al-Sowayan BS, Al-Shareeda AT, Alrfaei BM. Cancer stem cell-exosomes, unexposed player in tumorigenicity. Front Pharmacol. (2020) 11:384. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Chang CH, Pauklin S. Extracellular vesicles in pancreatic cancer progression and therapies. Cell Death Dis. (2021) 12:973. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-04258-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Tsunedomi R, Yoshimura K, Kimura Y, Nishiyama M, Fujiwara N, Matsukuma S, et al. Elevated expression of RAB3B plays important roles in chemoresistance and metastatic potential of hepatoma cells. BMC Cancer. (2022) 22:260. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09370-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Naghibi AF, Daneshdoust D, Taha SR, Abedi S, Dehdezi PA, Zadeh MS, et al. Role of cancer stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in cancer progression and metastasis. Pathol Res Pract. (2023) 247:154558. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2023.154558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Li M, Lin C, Cai Z. Breast cancer stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles transfer ARRDC1-AS1 to promote breast carcinogenesis via a miR-4731–5p/AKT1 axis-dependent mechanism. Transl Oncol. (2023) 31:101639. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2023.101639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Li L, Xiong Y, Wang N, Zhu M, Gu Y. Breast cancer stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles affect PPARG expression by delivering microRNA-197 in breast cancer cells. Clin Breast Cancer. (2022) 22:478–90. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2022.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Zhang Y, Chen Y, Shi L, Li J, Wan W, Li B, et al. Extracellular vesicles microRNA-592 of melanoma stem cells promotes metastasis through activation of MAPK/ERK signaling pathway by targeting PTPN7 in non-stemness melanoma cells. Cell Death Discovery. (2022) 8:428. doi: 10.1038/s41420-022-01221-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Vera N, Acuna-Gallardo S, Grunenwald F, Caceres-Verschae A, Realini O, Acuna R, et al. Small extracellular vesicles released from ovarian cancer spheroids in response to cisplatin promote the pro-tumorigenic activity of mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. (2019) 20. doi: 10.3390/ijms20204972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Tang CH, Qin L, Gao YC, Chen TY, Xu K, Liu T, et al. APE1 shRNA-loaded cancer stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles reverse Erlotinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer via the IL-6/STAT3 signalling. Clin Transl Med. (2022) 12:e876. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Lucchetti D, Colella F, Perelli L, Ricciardi-Tenore C, Calapa F, Fiori ME, et al. CD147 promotes cell small extracellular vesicles release during colon cancer stem cells differentiation and triggers cellular changes in recipient cells. Cancers (Basel). (2020) 12. doi: 10.3390/cancers12020260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Gonzalez-Callejo P, Gener P, Diaz-Riascos ZV, Conti S, Camara-Sanchez P, Riera R, et al. Extracellular vesicles secreted by triple-negative breast cancer stem cells trigger premetastatic niche remodeling and metastatic growth in the lungs. Int J Cancer. (2023) 152:2153–65. doi: 10.1002/ijc.34447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Shi L, Li B, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Tan J, Chen Y, et al. Exosomal lncRNA Mir100hg derived from cancer stem cells enhance glycolysis and promote metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma through mircroRNA-15a-5p/31–5p. Cell Commun Signal. (2023) 21:248. doi: 10.1186/s12964-023-01281-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Zhao H, Jiang R, Zhang C, Feng Z, Wang X. LncRNA H19-rich extracellular vesicles derived from gastric cancer stem cells facilitate tumorigenicity and metastasis via mediating intratumor communication network. J Transl Med. (2023) 21:238. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-04055-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Carli ALE, Afshar-Sterle S, Rai A, Fang H, O'keefe R, Tse J, et al. Cancer stem cell marker DCLK1 reprograms small extracellular vesicles toward migratory phenotype in gastric cancer cells. Proteomics. (2021) 21:e2000098. doi: 10.1002/pmic.202000098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Peng D, Wang H, Li L, Ma X, Chen Y, Zhou H, et al. miR-34c-5p promotes eradication of acute myeloid leukemia stem cells by inducing senescence through selective RAB27B targeting to inhibit exosome shedding. Leukemia. (2018) 32:1180–8. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0015-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Altorki NK, Markowitz GJ, Gao D, Port JL, Saxena A, Stiles B, et al. The lung microenvironment: an important regulator of tumour growth and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. (2019) 19:9–31. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0081-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Lu W, Kang Y. Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer progression and metastasis. Dev Cell. (2019) 49:361–74. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Wang L, Yang G, Zhao D, Wang J, Bai Y, Peng Q, et al. CD103-positive CSC exosome promotes EMT of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: role of remote MiR-19b-3p. Mol Cancer. (2019) 18:86. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0997-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Bao S, Wu Q, Sathornsumetee S, Hao Y, Li Z, Hjelmeland AB, et al. Stem cell-like glioma cells promote tumor angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res. (2006) 66:7843–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Treps L, Perret R, Edmond S, Ricard D, Gavard J. Glioblastoma stem-like cells secrete the pro-angiogenic VEGF-A factor in extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. (2017) 6:1359479. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2017.1359479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Inal JM, Kosgodage U, Azam S, Stratton D, Antwi-Baffour S, Lange S. Blood/plasma secretome and microvesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2013) 1834:2317–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Busatto S, Zendrini A, Radeghieri A, Paolini L, Romano M, Presta M, et al. The nanostructured secretome. Biomater Sci. (2019) 8:39–63. doi: 10.1039/C9BM01007F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Madden EC, Gorman AM, Logue SE, Samali A. Tumour cell secretome in chemoresistance and tumour recurrence. Trends Cancer. (2020) 6:489–505. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Ranganath SH, Levy O, Inamdar MS, Karp JM. Harnessing the mesenchymal stem cell secretome for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Cell Stem Cell. (2012) 10:244–58. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]