ABSTRACT

Advances in diabetes medication and population aging are lengthening the lifespans of people with diabetes mellitus (DM). Older patients with diabetes mellitus often have multimorbidity and tend to have polypharmacy. In addition, diabetes mellitus is associated with frailty, functional decline, cognitive impairment, and geriatric syndrome. Although the numbers of patients with frailty, dementia, disability, and/or multimorbidity are increasing worldwide, the accumulated evidence on the safe and effective treatment of these populations remains insufficient. Older patients, especially those older than 75 years old, are often underrepresented in randomized controlled trials of various treatment effects, resulting in limited clinical evidence for this population. Therefore, a deeper understanding of the characteristics of older patients is essential to tailor management strategies to their needs. The clinical guidelines of several academic societies have begun to recognize the importance of relaxing glycemic control targets to prevent severe hypoglycemia and to maintain quality of life. However, glycemic control levels are thus far based on expert consensus rather than on robust clinical evidence. There is an urgent need for the personalized management of older adults with diabetes mellitus that considers their multimorbidity and function and strives to maintain a high quality of life through safe and effective medical treatment. Older adults with diabetes mellitus accompanied by frailty, functional decline, cognitive impairment, and multimorbidity require special management considerations and liaison with both carers and social resources.

Keywords: Frailty, Multimorbidity, Polypharmacy

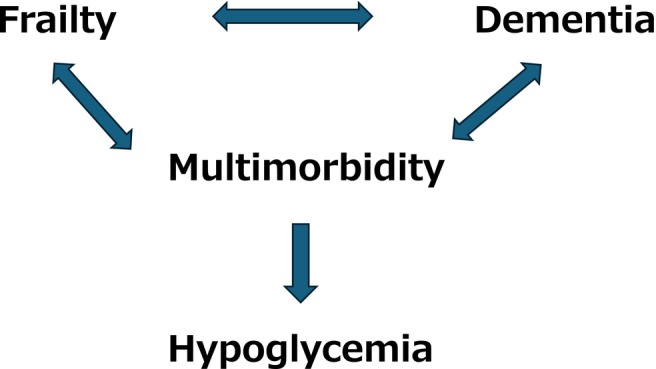

Frailty, dementia, and multimorbidity are associated with each other and lead to a high risk of hypoglycemia.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) is increasing worldwide, especially in the older population. In particular, type 2 diabetes mellitus is more common than type 1 in older adults. This specific type of diabetes mellitus manifests as hyperglycemia due to a deterioration of insulin secretion and elevated insulin resistance of varying degrees. These two conditions tend to progress with aging, increasing the number of older adults living with diabetes mellitus 1 . One study estimated that the prevalence of diabetes mellitus peaks in individuals in their late 70s in high‐income countries 2 . Advances in the treatment and management of diabetes mellitus, particularly type 2, have led to the longer survival of individuals with diabetes mellitus. Consequently, the population of older adults with diabetes mellitus and other long‐term conditions is growing. While diabetes management primarily focuses on avoiding diabetes‐related complications through glycemic control, the approach becomes more complex in frail older adults with multimorbidity, cognitive impairment, and functional decline. In this population, the merits of lowered glycemic levels often decrease while the risks of severe hypoglycemia increase. The clinical guidelines of several academic societies have begun to recognize the importance of setting lower limits for glycemic control to prevent severe hypoglycemia and to maintain quality of life (QOL) 3 . However, glycemic control targets are still based on expert consensus rather than on robust clinical evidence.

Given the global increase in the older population, it is imperative to understand the characteristics of older patients with diabetes mellitus and to develop effective management strategies for this population. However, older patients, especially those older than 75 years old, are often underrepresented in the randomized controlled trials conducted to test treatments, resulting in limited clinical evidence for this population. Therefore, a deeper understanding of the characteristics of older patients is essential for their personalized management. For older adults with diabetes mellitus, a geriatric perspective is often practical, useful, and, above all, helpful for patients. A geriatric perspective in diabetes mellitus management does not overly focus on single diseases but instead considers the overall management of multimorbidity while taking into account patients’ functional status and social circumstances.

MULTIMORBIDITY AND POLYPHARMACY

Multimorbidity is usually defined as the coexistence of two or more chronic diseases 4 . It is associated with an elevated risk of death and disability, reduced QOL, and high utilization of health care services and increased costs 5 . One study reported that more than 90% of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus exhibit multimorbidity 6 , which has been associated with a significantly higher risk of hypoglycemia and adverse drug reactions 7 . In multimorbid individuals, polypharmacy and reduced organ function are at least partly associated with the increased risk of hypoglycemia. Indeed, a study in Europe showed that older people with type 2 diabetes mellitus and multimorbidity experience more adverse drug reactions and higher mortality, mainly due to medication‐associated acute kidney injury (AKI) 8 .

Polypharmacy, often defined as the use of more than five prescription medications, is prevalent among older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus due to multimorbidity. Multimorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus patients are often taking multiple antidiabetic agents for glycemia control and also require several additional medications to manage comorbidities such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular disease. Polypharmacy is found at high frequencies in older patients 9 . A recent systematic review found a 64% prevalence of polypharmacy in older patients with diabetes 10 , which was associated with poor glycemic control, increased risk of hypoglycemia, and other adverse health outcomes such as falls, syncope, hospitalization, and death 11 . Furthermore, the presence of diabetes–multimorbidity combinations is associated with disability in middle‐aged and older adults 12 .

It is not very practical and sometimes even harmful to implement the combined treatment of single diseases in multimorbid older adults. The management of older adults with multimorbidity exhibits increased complexity. Clinicians require a personalized approach for this population, and clinical guidelines have suggested considering multimorbidity when setting glycemic control targets for older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus 13 , 14 , because older multimorbid patients are likely to develop organ damage due to reduced renal function and to have adverse drug reactions due to drug interactions. However, in reality, a study reported that older and multimorbid patients achieved even lower glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels than the non‐multimorbid population, possibly due to treatment 15 , which could increase the risk of severe hypoglycemic events.

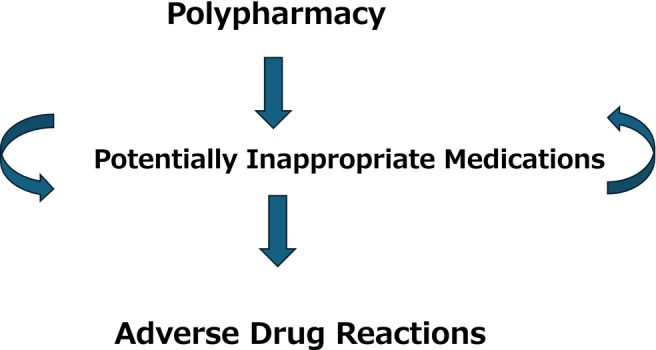

Potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) are medications that should be avoided due to their high risk of adverse drug reactions. Polypharmacy is often associated with the prescription of PIMs, which have been linked to adverse health outcomes such as all‐cause hospital admissions, emergency room visits, and fractures in older adults with diabetes 16 . Studies have reported a prevalence of PIM prescriptions ranging from 24.9% to 39.6% in older patients with diabetes 17 , 18 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Polypharmacy and adverse drug reactions.

While several clinical practice guidelines advocate for the deprescription of glucose‐lowering agents in older patients with complex backgrounds, such as frailty, multimorbidity, or dementia, particularly those residing in institutional settings, recommendations supported by high‐level clinical evidence have not yet been provided 19 . Further accumulation of data is warranted.

COGNITIVE DYSFUNCTION AND DEMENTIA

Diabetes mellitus has been identified as one of the modifiable risk factors for dementia 20 . The relative risk has been reported to be 1.5 (95% confidence interval: 1.3–1.8). Although the mechanism underlying the relationship between diabetes mellitus and dementia is still unclear 21 , 22 , several hypotheses have been proposed 23 . One is the possibility that hyperglycemic conditions and insulin resistance both affect amyloid‐β metabolism and tau phosphorylation, thereby exacerbating Alzheimer's disease brain pathology. Furthermore, it has been pointed out that diabetes mellitus increases chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, which may lead to neurodegeneration. Diabetes mellitus also worsens vascular lesions due to arteriosclerosis, which may lead to cognitive decline associated with cerebrovascular disorders 22 .

The association between glycemic control levels and dementia incidence also remains to be elucidated. Randomized control studies have not shown the ability of lower glycemic levels to reduce dementia risk 24 . However, several observational studies support a U‐ or J‐shaped association between HbA1c levels and dementia incidence 25 , 26 , 27 . These studies suggest that an HbA1c level of around 7% seems to be associated with a low dementia risk, although the results regarding the appropriate levels of HbA1c are not entirely consistent.

The reasons for the U‐ or J‐shaped associations between dementia risk and glycemic levels are not clearly understood. Intensive glycemic control via medication may induce hypoglycemia, which is a risk factor for dementia, potentially offsetting the protective effects of therapy. Further research is warranted.

Cognitive impairment is associated with poor adherence to therapy, leading to difficulties in performing self‐care, which often make the therapeutic management more challenging. Therefore, some guidelines, including those of the American Diabetes Association and Endocrine Society, recommend relaxing the glycemic targets for older patients with dementia 28 , 29 . Once dementia is diagnosed, formal and informal care should be considered, and specific medication indications may be explored, including cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine.

FUNCTIONAL DECLINE

A systematic review concluded that diabetes mellitus was a risk factor for mobility disability and disability of both instrumental and basic activities of daily living (ADLs) 30 . The consequences of a decline in ADL in older adults with diabetes mellitus can be significant and multifaceted. Functional decline may lead to poor self‐care and predispose the patients to poor disease control or hypoglycemia. A greater level of dependency was identified as a risk factor for hypoglycemia 31 . Some clinical guidelines recommend that overtreatment be avoided in older adults with a functional decline 3 . An ADL decline is also a risk factor for falls 32 , which could cause further functional declines. Difficulty in performing ADL restricts social activities, which may lead to social isolation. Moreover, functional decline restricts patients’ ability to perform essential tasks of daily life, which may lead to reduced QOL 33 .

FRAILTY AND GERIATRIC SYNDROME

Frailty and sarcopenia are age‐related conditions. Frailty is characterized by a reduced physiological reserve 34 , whereas sarcopenia is defined as age‐associated loss of muscle mass and power 35 . Type 2 diabetes mellitus has been linked to both conditions 36 . A recent meta‐analysis reported prevalences of prefrailty and frailty in older adults (aged 60 years and above) with diabetes of 20.1% and 49.1%, respectively 37 . Frailty in older people with diabetes has been associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including death, hospitalization, emergency department visits, and disability 38 . Older adults with diabetes mellitus reportedly have a higher risk of fractures, with sarcopenia cited as a contributing factor to falls that lead to fractures 39 .

There are several possible reasons why frailty and sarcopenia may predispose diabetes 36 . Insulin resistance is increased in diabetes. It is often thought that, under insulin resistance conditions, protein anabolism may be reduced, leading to a fall in muscle synthesis. Furthermore, mitochondrial function is impaired in diabetic patients, resulting in decreased muscle performance. Moreover, chronic inflammation and oxidative stress associated with diabetes promote the development of sarcopenic frailty.

Frailty in older people with diabetes has been associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including death, hospitalization, emergency department visits, and disability 40 , 41 .

While some reports suggest that the incidence of frailty is associated with poor blood glucose control 42 , 43 , a low glycemic state may also pose a risk for frailty 44 , and hypoglycemic episodes are another risk factor 45 .

The evidence regarding the optimal glycemic levels in frail older adults with diabetes is limited 46 . In a subanalysis of the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACOORD) study, intensive glycemic control was found to be ineffective in preventing diabetic complications and death among frail subjects 47 . This finding may support the relaxing of glycemic control levels in frail older adults. Furthermore, deintensification of glycemic control in a nursing home population did not lead to increased emergency department visits, hospitalizations, or mortality 48 . This suggests that deintensification of glycemic control to avoid overtreatment may be considered in institutionalized frail older adults with diabetes mellitus.

However, a study from the UK Biobank demonstrated that higher HbA1c levels were associated with higher mortality in frail individuals, which may contradict the possible recommendation of relaxed glycemic control levels in this population 49 . This study also indicated that HbA1c levels lower than 40 mmol/mol (~5.9%) were associated with higher mortality in frail older individuals, suggesting the importance of avoiding overtreatment in this population.

Geriatric syndrome encompasses a group of multifactorial health conditions rooted in biological aging and multimorbidity, although its specific contributors have not been strictly defined 50 . The conditions considered part of geriatric syndrome typically include falls, cognitive impairment, urinary incontinence, and dizziness. Polypharmacy is often associated with geriatric syndrome because medications are frequently prescribed to manage its symptoms 51 , and it has been linked to a diminished QOL 52 . Geriatric syndrome typically involves multiple organ systems. Because frailty is often associated with functional decline and cognitive impairment, there is significant overlap between frailty and geriatric syndrome, despite their distinctions, and they mutually interact in complex ways, leading to adverse health outcomes.

COMPREHENSIVE GERIATRIC ASSESSMENTS

Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) is a thorough, multidimensional process involving various disciplines aimed at identifying the medical, social, and functional needs of older adults. It facilitates the development of integrated care plans tailored to meet those needs 53 . CGA has shown positive outcomes in terms of survival among acutely unwell hospitalized older individuals, irrespective of the presence of diabetes mellitus 54 . Additionally, evidence suggests a reduction in unplanned admissions among frail, community‐dwelling older adults 55 . The CGA process helps to provide holistic and patient‐centered care by understanding social support networks, identifying caregiver strain, addressing family dynamics, assessing social determinants of health, and promoting social engagement and it aims to optimize outcomes and to enhance the overall well‐being of older adults.

As noted previously, older patients with diabetes mellitus often present with multimorbidity, reduced ADLs, and cognitive decline 56 . They may also have geriatric syndrome and frailty. CGA is expected to be effective in addressing the needs of this population 57 . However, while promising, the evidence supporting the effectiveness of CGA specifically in older individuals with diabetes mellitus is not yet sufficient, warranting further research.

HYPOGLYCEMIA

Cognitive impairment, dementia, renal impairment, and sulfonylurea use 58 , as well as multimorbidity, are all risk factors for hypoglycemia, with an increased number of comorbidities associated with higher risk 7 . Hypoglycemia, in turn, increases the risk of dementia incidence 59 and frailty 45 (Figure 2). More importantly, severe glycemic events have been associated with greater fear and lower QOL in patients with diabetes mellitus 60 .

Figure 2.

Association of hypoglycemia with frailty, dementia, and multimorbidity.

Older adults tend to have less awareness of 61 and worse recovery from 62 hypoglycemia due to age‐associated physiological changes, which may increase harms. Several studies reported that hypoglycemia in older adults was associated with severe clinical consequences and increased risk of death 63 , 64 .

Recent clinical guidelines recommend avoiding diabetes overtreatment to prevent hypoglycemia by setting lower limits for glycemia levels in older patients with complex backgrounds, although discrepancies exist regarding individualized HbA1c targets 3 . The Endocrine Society recommends HbA1c targets between 8.0% and 8.5% for individuals with declined ADLs in two or more domains, moderate‐to‐severe dementia, end‐stage illness, or residence in long‐term care facilities 29 . A study of multimorbid older patients with diabetes reported that overtreatment (lower HbA1c values than guideline recommendations) was associated with higher mortality 65 . Although further studies are warranted, glycemic control levels in multimorbid frail older subjects, particularly those in long‐term care facilities, should be carefully considered, balancing the benefits of pharmacotherapy with the risks of severe hypoglycemia.

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Adequate glycemic control is required to prevent diabetes mellitus‐related complications at all ages. However, intensive treatment may be less beneficial in frail older patients with complex backgrounds and predispose vulnerable patients to hypoglycemia.

Several guidelines recommend individualized glycemic control levels based on patients’ health backgrounds 3 . However, the definitions of patient background categories and the recommended HbA1c levels are not entirely consistent. Moreover, these recommendations are currently primarily based on expert opinions, and additional clinical evidence is required to support them.

Metformin is a first‐line medication at any age. Because sufficient renal function is needed to clear this drug, dose titration is required in older subjects with reduced renal function 66 . An unrecognized renal functional decline may induce lactic acidosis, which is a rare but severe adverse event. Regular monitoring of kidney function is required.

Dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4) inhibitors are recommended for the treatment of frail older adults with diabetes mellitus at high risk of hypoglycemia 67 due to the low risk of these agents inducing hypoglycemia. DPP‐4 inhibitors are weight‐neutral, which may also be advantageous for populations with a low body weight. However, the clinical guidelines of the American College of Physicians recently recommended against the use of DPP‐4 inhibitors due to a lack of evidence for reducing all‐cause mortality and cardiovascular events 68 . This recommendation applied to the general long‐standing type 2 diabetes mellitus population with an HbA1c level around 8% despite usual care with metformin and lifestyle modification. Further consideration of metformin use is warranted in frail older adults with renal functional decline whose condition complicates the use of metformin.

Sodium‐glucose transporter‐2 (SGLT‐2) inhibitors have beneficial effects on cardiometabolic and renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Recent studies suggest that SGLT‐2 inhibitors may be tolerated by frail older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus who have obesity‐based frailty 69 , 70 . However, there is limited evidence for anorexic, malnourished older adults with frailty. Frailty is a heterogeneous condition, ranging from sarcopenic obesity‐based phenotypes to anorexic, malnourished phenotypes with less muscle mass and lower body weight. Weight‐neutral hypoglycemic agents may be more suitable for those with the anorexic, malnourished phenotype 71 .

Glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1) receptor agonists also have several beneficial effects in the general population with diabetes mellitus, and several lines of evidence have indicated their efficacy and tolerance in the older population 72 , 73 . However, the evidence is currently very limited in frail older adults 70 . This drug category sometimes causes initial nausea and other gastrointestinal symptoms, which may necessitate caution in anorexic, malnourished patients with frailty.

Long‐acting sulfonylureas are defined as PIMs by several screening tools, including the STOPP/START 74 and Beers 75 criteria, because of a high risk of hypoglycemia. Prescribers should balance the merits of glycemia lowering with the risk of hypoglycemia by contemplating each patient's background and also consider alternatives to these medications.

Insulin therapy for frail multimorbid older patients with cognitive impairment requires particular caution because it is associated with hypoglycemia. On the other hand, the weight gain observed with insulin therapy, while often considered unfavorable, might be useful in undernourished frail patients. Complex therapeutic regimens with multiple daily injections could be considered after trying simpler combinations including basal insulin plus oral agents. Complex regimens may lead to poor adherence, not only because injections are missed, but also because excessive insulin doses might be administered. Education of caregivers as well as patients themselves would also be required.

Complex pharmacotherapy sometimes leads to a large burden in frail older adults with multimorbidity and cognitive impairment, which may reduce these patients’ QOL 76 . The aim of the treatment should be carefully reviewed with assessment of patients’ capacity and consideration of their opinions.

NONPHARMACOTHERAPY

Frailty, as discussed previously, can manifest as a spectrum from undernutrition to overnutrition. Therefore, dietary therapy should be tailored to individual needs 77 . Adequate protein intake is recommended to prevent sarcopenia in older individuals with diabetes, as well as in the general population 78 . Too stringent a diet may accelerate muscle loss and malnutrition.

Exercise is crucial for glycemic management in diabetes and also promotes muscle hypertrophy. Resistance training typically enhances muscle mass, strength, and performance in older individuals with diabetes 78 . Although the effects of aerobic training on body composition have been less studied in older patients with diabetes, one study did report positive outcomes 79 while a systematic review reported effects on glucose metabolism 80 .

Combining nutritional therapy with exercise is more effective for increasing muscle strength and improving physical function. Such multifactorial interventions have been reported to improve physical function in elderly patients with diabetes 81 , 82 .

COORDINATION OF CARE AND USE OF SOCIAL RESOURCES

Public long‐term care insurance systems have been established in some countries, including Japan, and care services are provided according to the level of care needs of the individual 83 . Coordination of care has been associated with positive outcomes, including a reduced risk of hospitalization and emergency room visits for DM 84 . A Korean study showed that good continuity of care reduced avoidable hospitalizations and diabetes‐related complications 85 . In addition, social and economic situations often affect the management of diabetes mellitus. For example, living alone is sometimes associated with poor nutrition and medication adherence, necessitating comprehensive assessments. It is important to establish an individualized care delivery with the collaboration of official and unofficial care providers. The appropriate use of social resources in older frail patients with functional decline should be based on multidisciplinary and collaborative assessments.

CONCLUSION

Improvements in diabetes medications and aging of the population are leading to the longer survival of people with diabetes mellitus. Although the worldwide population with frailty, dementia, disability, and/or multimorbidity is increasing, the evidence supporting the safe and effective treatment of these populations is still lacking. QOL is also one of the top priorities in the treatment of these people but the associated evidence remains poor.

The personalized management of older adults with diabetes mellitus is urgently required to maintain a high QOL and to ensure safe and effective medical treatment. Older adults with diabetes mellitus and frailty, functional decline, cognitive impairment, and multimorbidity require special management considerations and liaison with both carers and social resources.

DISCLOSURE

The author declares no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Morley JE. The elderly type 2 diabetic patient: Special considerations. Diabet Med 1998; 15(Suppl 4): S41–S46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018; 138: 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Christiaens A, Henrard S, Zerah L, et al. Individualisation of glycaemic management in older people with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines recommendations. Age Ageing 2021; 50: 1935–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moffat K, Mercer SW. Challenges of managing people with multimorbidity in today's healthcare systems. BMC Fam Pract 2015; 16: 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev 2011; 10: 430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chiang JI, Furler J, Mair F, et al. Associations between multimorbidity and glycaemia (HbA1c) in people with type 2 diabetes: Cross‐sectional study in Australian general practice. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e039625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCoy RG, Lipska KJ, Van Houten HK, et al. Association of cumulative multimorbidity, glycemic control, and medication use with hypoglycemia‐related emergency department visits and hospitalizations among adults with diabetes. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3: e1919099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chinmayee A, Subbarayan S, Myint PK, et al. Diabetes mellitus increases risk of adverse drug reactions and death in hospitalised older people: The SENATOR trial. Eur Geriatr Med 2024; 15: 189–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Strehblow C, Smeikal M, Fasching P. Polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy in octogenarians and older acutely hospitalized patients. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2014; 126: 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Quiñones AR, Markwardt S, Botoseneanu A. Diabetes‐multimorbidity combinations and disability among middle‐aged and older adults. J Gen Intern Med 2019; 34: 944–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Noale M, Veronese N, Cavallo Perin P, et al. Polypharmacy in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes receiving oral antidiabetic treatment. Acta Diabetol 2016; 53: 323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Remelli F, Ceresini MG, Trevisan C, et al. Prevalence and impact of polypharmacy in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Aging Clin Exp Res 2022; 34: 1969–1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. American diabetes association standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Section 6. Glycemic targets. Diabetes Care 2019; 42: S61–S70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Japan Diabetes Society/Japan Geriatrics Society Joint Committee on Improving Care for Elderly Patients with Diabetes . Glycemic targets for elderly patients with diabetes. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2016; 16: 1243–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCoy RG, Lipska KJ, Van Houten HK, et al. Paradox of glycemic management: Multimorbidity, glycemic control, and high‐risk medication use among adults with diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2020; 8: e001007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lu Wang S, Chen J, Yang Y, et al. Associated adverse health outcomes of polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications in community‐dwelling older adults with diabetes. Front Pharmacol 2023; 14: 1284287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oktora MP, Alfian SD, Bos HJ, et al. Trends in polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) in older and middle‐aged people treated for diabetes. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2021; 87: 2807–2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Faquetti ML, Frey G, Stämpfli D, et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications among newly treated patients with type 2 diabetes in UK primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2024; 90: 1376–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Christiaens A, Henrard S, Sinclair AJ, et al. Deprescribing glucose‐lowering therapy in older adults with diabetes: A systematic review of recommendations. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2023; 24: 400–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020; 396: 413–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bellia C, Lombardo M, Meloni M, et al. Diabetes and cognitive decline. Adv Clin Chem 2022; 108: 37–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Umegaki H. Type 2 diabetes as a risk factor for cognitive impairment: Current insights. Clin Interv Aging 2014; 9: 1011–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Umegaki H, Hayashi T, Nomura H, et al. Cognitive dysfunction: An emerging concept of a new diabetic complication in the elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2013; 13: 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tuligenga RH. Intensive glycaemic control and cognitive decline in patients with type 2 diabetes: A meta‐analysis. Endocr Connect 2015; 4: R16–R24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crane PK, Walker R, Hubbard RA, et al. Glucose levels and risk of dementia. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 540–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moran C, Lacy ME, Whitmer RA, et al. Glycemic control over multiple decades and dementia risk in people with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Neurol 2023; 80: 597–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang K, Zhao S, Lee EK, et al. Risk of dementia among patients with diabetes in a multidisciplinary, primary care management program. JAMA Netw Open 2024; 7: e2355733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. American Diabetes Association . Older adults: Standards of medical Care in Diabetes‐2020. Diabetes Care 2020; 43(Suppl 1): S152–S162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. LeRoith D, Biessels GJ, Braithwaite SS, et al. Treatment of diabetes in older adults: An Endocrine Society* clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019; 104: 1520–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wong E, Backholer K, Gearon E, et al. Diabetes and risk of physical disability in adults: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2013; 1: 106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. De Decker L, Hanon O, Boureau AS, et al. Association between hypoglycemia and the burden of comorbidities in hospitalized vulnerable older diabetic patients: A cross‐sectional, population‐based study. Diabetes Ther 2017; 8: 1405–1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shao L, Shi Y, Xie XY, et al. Incidence and risk factors of falls among older people in nursing homes: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2023; 24: 1708–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bourdel‐Marchasson I, Helmer C, Fagot‐Campagna A, et al. Disability and quality of life in elderly people with diabetes. Diabetes Metab 2007; 33: S66–S74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cesari M, Calvani R, Marzetti E. Frailty in older persons. Clin Geriatr Med 2017; 33: 293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cruz‐Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019; 48: 601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Umegaki H. Sarcopenia and frailty in older patients with diabetes mellitus. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2016; 16: 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kong LN, Lyu Q, Yao HY, et al. The prevalence of frailty among community‐dwelling older adults with diabetes: A meta‐analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2021; 119: 103952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013; 381: 752–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sarodnik C, Bours SPG, Schaper NC, et al. The risks of sarcopenia, falls and fractures in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Maturitas 2018; 109: 70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Castro‐Rodríguez M, Carnicero JA, Garcia‐Garcia FJ, et al. Frailty as a major factor in the increased risk of death and disability in older people with diabetes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016; 17: 949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li CL, Stanaway FF, Lin JD, et al. Frailty and health care use among community‐dwelling older adults with diabetes: A population‐based study. Clin Interv Aging 2018; 13: 2295–2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zaslavsky O, Walker RL, Crane PK, et al. Glucose levels and risk of frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016; 71: 1223–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kalyani RR, Tian J, Xue QL, et al. Hyperglycemia and incidence of frailty and lower extremity mobility limitations in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60: 1701–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Abdelhafiz AH, Peters S, Sinclair AJ. Low glycaemic state increases risk of frailty and functional decline in older people with type 2 diabetes mellitus ‐ evidence from a systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2021; 181: 109085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chao CT, Wang J, Huang JW, et al. Hypoglycemic episodes are associated with an increased risk of incident frailty among new onset diabetic patients. J Diabetes Complications 2020; 34: 107492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. O'Neil H, Todd A, Pearce M, et al. What are the consequences of over and undertreatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in a frail population? A systematic review. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab 2024; 7: e00470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nguyen TN, Harris K, Woodward M, et al. The impact of frailty on the effectiveness and safety of intensive glucose control and blood pressure‐lowering therapy for people with type 2 diabetes: Results from the ADVANCE trial. Diabetes Care 2021; 44: 1622–1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Niznik JD, Zhao X, Slieanu F, et al. Effect of deintensifying diabetes medications on negative events in older veteran nursing home residents. Diabetes Care 2022; 45: 1558–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hanlon P, Jani BD, Butterly E, et al. An analysis of frailty and multimorbidity in 20,566 UK biobank participants with type 2 diabetes. Commun Med (Lond) 2021; 1: 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Neumiller JJ, Munshi MN. Geriatric syndromes in older adults with diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2023; 52: 341–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Umegaki H, Nagae M, Komiya H, et al. Clinical significance of geriatric conditions in acute hospitalization. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2023; 23: 50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang YC, Lin MH, Wang CS, et al. Geriatric syndromes and quality of life in older adults with diabetes. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2019; 19: 518–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Parker SG, McCue P, Phelps K, et al. What is comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA)? An umbrella review. Age Ageing 2018; 47: 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ellis G, Gardner M, Tsiachristas A, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 9: CD006211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Briggs R, McDonough A, Ellis G, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for community‐dwelling, high‐risk, frail, older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2022; 5: CD012705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vu HTT, Nguyen TTH, Le TA, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in older patients with diabetes mellitus in Hanoi, Vietnam. Gerontology 2022; 68: 1132–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Araki A, Ito H. Diabetes mellitus and geriatric syndromes. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2009; 9: 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hermann M, Heimro LS, Haugstvedt A, et al. Hypoglycaemia in older home‐dwelling people with diabetes‐ a scoping review. BMC Geriatr 2021; 21: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gómez‐Guijarro MD, Álvarez‐Bueno C, Saz‐Lara A, et al. Association between severe hypoglycaemia and risk of dementia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2023; 39: e3610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Núñez M, Díaz S, Dilla T, et al. Epidemiology, quality of life, and costs associated with hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes in Spain: A systematic literature review. Diabetes Ther 2019; 10: 375–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Matyka K, Evans M, Lomas J, et al. Altered hierarchy of protective responses against severe hypoglycemia in normal aging in healthy men. Diabetes Care 1997; 20: 135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Meneilly GS, Cheung E, Tuokko H. Altered responses to hypoglycemia of healthy elderly people. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994; 78: 1341–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Davis SN, Duckworth W, Emanuele N, et al. Effects of severe hypoglycemia on cardiovascular outcomes and death in the veterans affairs diabetes trial. Diabetes Care 2019; 42: 157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zoungas S, Patel A, Chalmers J, et al. Severe hypoglycemia and risks of vascular events and death. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 1410–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Christiaens A, Baretella O, Del Giovane C, et al. Association between diabetes overtreatment in older multimorbid patients and clinical outcomes: An ancillary European multicentre study. Age Ageing 2023; 52: afac320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sambol NC, Chiang J, Lin ET, et al. Kidney function and age are both predictors of pharmacokinetics of metformin. J Clin Pharmacol 1995; 35: 1094–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Avogaro A, Dardano A, de Kreutzenberg SV, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors can minimize the hypoglycaemic burden and enhance safety in elderly people with diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2015; 17: 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Qaseem A, Obley AJ, Shamliyan T, et al. Newer pharmacologic treatments in adults with type 2 diabetes: A clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2024; 177: 658–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Aldafas R, Crabtree T, Alkharaiji M, et al. Sodium‐glucose cotransporter‐2 inhibitors (SGLT2) in frail or older people with type 2 diabetes and heart failure: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Age Ageing 2024; 53: afad254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kutz A, Kim DH, Wexler DJ, et al. Comparative cardiovascular effectiveness and safety of SGLT‐2 inhibitors, GLP‐1 receptor agonists, and DPP‐4 inhibitors according to frailty in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2023; 46: 2004–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sinclair AJ, Pennells D, Abdelhafiz AH. Hypoglycaemic therapy in frail older people with type 2 diabetes mellitus‐a choice determined by metabolic phenotype. Aging Clin Exp Res 2022; 34: 1949–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Meneilly GS, Roy‐Duval C, Alawi H, et al. Lixisenatide therapy in older patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on their current antidiabetic treatment: The GetGoal‐O randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2017; 40: 485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gilbert MP, Bain SC, Franek E, et al. Effect of liraglutide on cardiovascular outcomes in elderly patients: A post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2019; 170: 423–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. O'Mahony D, O'Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: Version 2. Age Ageing 2015; 44: 213–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel . American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS beers criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019; 67: 674–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sayyed Kassem L, Aron DC. The assessment and management of quality of life of older adults with diabetes mellitus. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab 2020; 15: 71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Tamura Y, Omura T, Toyoshima K, et al. Nutrition management in older adults with diabetes: A review on the importance of shifting prevention strategies from metabolic syndrome to frailty. Nutrients 2020; 12: 3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hashimoto Y, Takahashi F, Okamura T, et al. Diet, exercise, and pharmacotherapy for sarcopenia in people with diabetes. Metabolism 2023; 144: 155585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Vieira ER, Cavalcanti FADC, Civitella F, et al. Effects of exercise and diet on body composition and physical function in older hispanics with type 2 diabetes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 8019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Bouaziz W, Vogel T, Schmitt E, et al. Health benefits of aerobic training programs in adults aged 70 or over: A systematic review. Presse Med 2017; 46: 794–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Rodriguez‐Mañas L, Laosa O, Vellas B, et al. Effectiveness of a multimodal intervention in functionally impaired older people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019; 10: 721–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Houston DK, Neiberg RH, Miller ME, et al. Physical function following a long‐term lifestyle intervention among middle aged and older adults with type 2 diabetes: The look AHEAD study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018; 73: 1552–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Okamoto S, Komamura K. Towards universal health coverage in the context of population ageing: A narrative review on the implications from the long‐term care system in Japan. Arch Public Health 2022; 80: 210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Northwood M, Shah AQ, Abeygunawardena C, et al. Care coordination of older adults with diabetes: A scoping review. Can J Diabetes 2023; 47: 272–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Jung HW, Lee WR. Association between initial continuity of care status and diabetes‐related health outcomes in older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A nationwide retrospective cohort study in South Korea. Prim Care Diabetes 2023; 17: 600–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]