Abstract

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is responsible for maintaining brain homeostasis through nutrient delivery and waste removal for the central nervous system (CNS). Here, we demonstrate extensive CSF flow throughout the peripheral nervous system (PNS) by tracing distribution of multimodal 1.9-nanometer gold nanoparticles, roughly the size of CSF circulating proteins, infused within the lateral cerebral ventricle (a primary site of CSF production). CSF-infused 1.9-nanometer gold transitions from CNS to PNS at root attachment/transition zones and distributes through the perineurium and endoneurium, with ultimate delivery to axoplasm of distal peripheral nerves. Larger 15-nanometer gold fails to transit from CNS to PNS and instead forms “dye-cuffs,” as predicted by current dogma of CSF restriction within CNS, identifying size limitations in central to peripheral flow. Intravenous 1.9-nanometer gold is unable to cross the blood-brain/nerve barrier. Our findings suggest that CSF plays a consistent role in maintaining homeostasis throughout the nervous system with implications for CNS and PNS therapy and neural drug delivery.

Cerebrospinal fluid unites the nervous system by extending beyond the central nervous system into peripheral nerves.

INTRODUCTION

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is primarily produced by the choroid plexus located within the ventricles of the brain and bathes the tissues of the central nervous system (CNS) via low pressure pulsatile flow. CSF is continuously produced (approximately 0.5 liters per day in humans), providing physical cushioning and suppling nutrients, while points of CSF efflux from the system are vital for removing waste (1–10). In essence, the CSF flow system is critical for maintaining homeostasis within nervous tissues. Outside of the ventricular system, CSF is physically contained within the subarachnoid space (SAS) of the brain and spinal cord, a space created between inner two meningeal layers: the pia and arachnoid mater (4). The outermost meningeal layer, the dura, contains venous sinuses and lymphatics, functioning as a site of egress and immune surveillance of CSF (2, 6, 11–14). Peripheral nerves have similar multilayer connective tissue compartments contiguous with the CNS meninges at the peripheral root attachment zones (RAZ). The epineurium (similar to the dura) bundles multiple nerve fascicles, which are each enclosed by the perineurium (similar to the arachnoid). This enclosed region contains the endoneurium, a loose connective tissue space filled with a fluid similar in composition to CSF. The endoneurium contains bundled axons in a fluid-filled space creating an ideal environment for nerve function. However, the origin of endoneurial fluid (ENF) is debated (15, 16). Previous dye tracing studies identified accumulation of tracers at the subarachnoid angle, a “cul-de-sac” formed by CNS meninges, where peripheral nerves emerge from the CNS (4, 17–19). These studies helped establish patterns of CSF flow, and some studies suggested that flow may extend to the peripheral nervous system (PNS) but did not alter the overall conclusion of CSF restriction to the CNS (2, 10, 15, 17–20).

In this study, we traced CSF flow from sites of production in the CNS to peripheral nerves in live mice. We infused gold nanoparticles into the lateral cerebral ventricle and demonstrated gold delivery to distal peripheral nerves, including to the axoplasm of distal sciatic neurons. Peak distribution of nanogold delivered as a single intracerebral ventricular (ICV) bolus was size, time, and concentration dependent. CNS structures were labeled within minutes, while delivery to distal sciatic nerves peaked between 4 and 6 hours postinfusion. Electron microscopy confirmed nanogold delivery from the cerebral ventricle to the axoplasm of distal peripheral nerves. Our results support a contiguous and continuous CSF flow system from the CNS to the distal ends of peripheral nerves, a function likely integral in sustaining peripheral nerves through delivery of nutrients and removal of waste.

RESULTS

Ventricular infusion of gold nanoparticles demonstrates CSF flow to peripheral nerves

Gold nanoparticles were infused as a bolus into CSF of the lateral cerebral ventricles to trace CSF flow patterns in live mice to determine whether CSF can flow to peripheral nerves under physiological conditions. We selected nanogold to map CSF flow because of several notable advantages as a tracer: (i) It is available in a wide range of sizes; (ii) nanogold has low osmolality to enhance flow; (iii) enhanced gold staining methods allow increased sensitivity of detection by both light and electron microscopy. Initial experiments used 1.9-nm gold, which has an overall particle size of 3.5 nm, and is similar in size to nutrients and proteins typically found in CSF such as glucose (1.5 nm), albumin (~3.2 to 3.8 nm), cystatin C (3 to 12 nm), and brain derived neurotrophic factor (~3.5 nm) (21–24). Our “large particle” tracer was 15-nm gold with an overall particle size of 20 to 30 nm which is just above the size of immunoglobulin G at 15 nm, one of the largest proteins found in CSF (25–29). In contrast, adeno-associated virus at 25 nm is usually excluded by the blood-brain barrier (BBB)/blood-nerve barrier (BNB) unless leakage is induced, or neurotropic selected serotypes are used (30–32). Recent CSF flow studies using both gold and other nanoparticles have shown restricted movement within the CNS for particles of 20 to 40 nm compared to 3 to 5 nm, further supporting our size selections (5, 6, 33, 34). Therefore, 1.9-nm gold would be small enough to potentially transverse the BBB/BNB, while 15-nm gold particles should be mostly excluded.

To ensure our experimental design and probe faithfully traced CSF flow, we assessed whether infused nanogold distribution recapitulated established CSF flow patterns within the CNS. To do this, 1.9-nm nanogold was infused via a fine cannula within the lateral ventricle of a sedated mouse at a rate demonstrated to maintain physiologic distribution within the CNS (Fig. 1, A to J, and figs. S1 and S2) (5, 7, 35, 36). Following infusion, we harvested and analyzed CNS tissues (brain and spinal cord) immediately following 1.9-nm probe infusion (0 hours), a time for which ICV-injected tracer flow patterns have been well documented (fig. S2) (1, 18, 19, 37). Autometallography was used to enhance infused gold particles within CNS and PNS tissues for histologic examination (GoldEnhance, Nanoprobes Inc., Yaphank, NY). The gold enhancement generates black gold aggregates visible by light and electron microscopy to assess CSF flow in the CNS and PNS (Fig. 1). Gold labeling was seen on the apical surface of the ependymal cells lining the ventricle and of the choroid plexus as well as along the Foramen of Monro connecting the lateral and third ventricle (fig. S2, A and B). During infusion, nanogold traveled to the dorsal third ventricle with robust labeling of the ependymal cells and choroid plexus (fig. S2B). Molecules injected into the CSF spaces are known to flow between the arachnoid and pia matter in the SAS of the CNS (4, 8, 10). We observed clear labeling of the meninges of the brain and the optic nerve, a cranial nerve that is considered part of the CNS (fig. S2C). From the third ventricle, nanogold traversed the cerebral aqueduct (fig. S2D) to the fourth ventricle and then to the central canal of the spinal cord (fig. S2E). These data demonstrate that nanogold follows previously established CSF flow patterns within the CNS (4, 8–10).

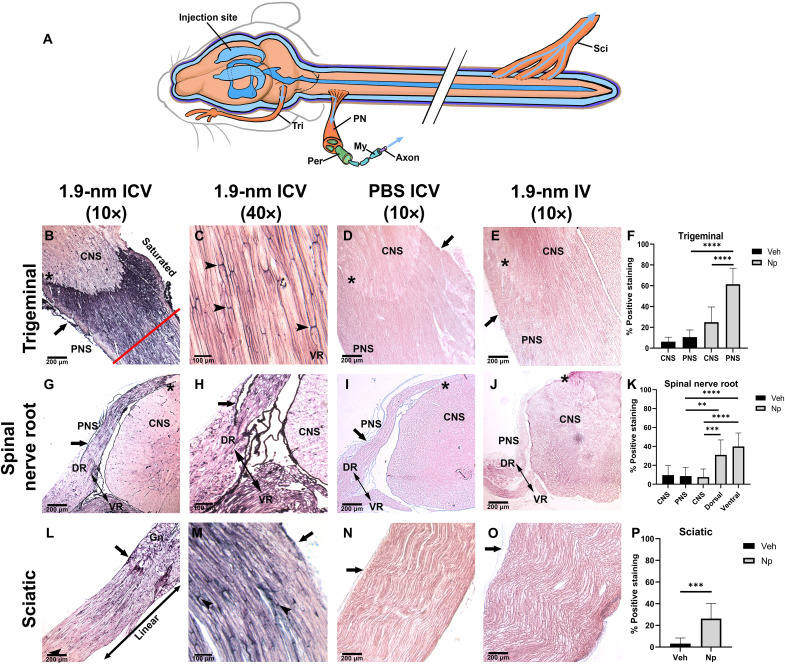

Fig. 1. CSF-infused nanoprobe travels to peripheral nerves.

Peripheral nerves were collected 4 and 6 hours after infusion of nanoprobe (B, C, G, H, L, and M), IV infusion (E, J, and O), and ICV of PBS (D, I, and N). Sections from the trigeminal nerve [(B) to (E)], spinal cord [(G) to (J)], and sciatic nerve [(L) to (O)] were developed with GoldEnhance for visualization; enhanced gold appears as black precipitate. Average nanogold (Np) staining of PNS compared to the CNS and PBS (Veh) controls (F, K, and P). CNS-PNS transition is marked by “*” in all panels. (A) Schematic of established CSF reservoirs; peripheral nerve (PN), axon (Ax), myelin (My), perineurium (Peri), and endoneurium (Endo). [(B) and (C)] Trigeminal nerve 4 hours after nanoprobe injection. (B) Staining is enhanced at the CNS-PNS transition. Perineurium is demarcated by closed arrow in all panels; arrowheads mark nodes of Ranvier. (C) High magnification of trigeminal endoneurial staining. (D) PBS-injected control. (E) Trigeminal nerve from IV animal 6 hours after nanoprobe infusion. [(F) and (G)] Cervical spinal nerve roots (NR)(double-sided arrow) showing dorsal root (DR) and ventral root (VR) from nanoprobe-infused animals. Closed arrow marks the subarachnoid angle of the dorsal root. (G) High-magnification image of subarachnoid angle. (H) Spinal cord from PBS-injected control. (I) Spinal cord from IV-injected animal 6 hours postnanoprobe infusion. Sciatic nerve taken at the ganglion 4 hours after nanoprobe injection (L) and high magnification 6 hours after nanoprobe injection (M). (N) PBS-injected control sciatic nerve. (O) Sciatic nerve from IV-injected animal 6 hours after nanoprobe infusion. (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001). Panels have a minimum N = 4.

CSF flow was assessed by observation of nanogold distribution patterns in peripheral nerves, namely, the trigeminal, spinal, and sciatic nerves (Methods, experimental details, and supplementary figures available online). Sections of peripheral nerves (trigeminal, cervical spinal nerve root, and sciatic) harvested 6 hours after nanogold ICV infusion show nanogold distribution from the CSF of the CNS to peripheral nerves (Fig. 1, B, C, G, H, L, and M). Control tissues from phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) ICV-infused animals (Fig. 1, D, I, and N) show only background staining after gold enhancement (Fig. 1, F, K, and P). Substantial deposition of nanogold was seen in the perineurium of peripheral nerves (Fig. 1, B, G, L, and M, arrows), and deposition was observed within the endoneurium, resulting in distinctive labeling of the nodes of Ranvier compared to control tissues (Fig. 1, C, L, and M, arrowheads). To control for vascular influence on nervous system staining, we performed intravenous (IV) injections with the same amount of nanogold used for ventricular injections. We then harvested the corresponding tissues at 6 hours post-IV injection to the vascular system, the same time point used for PNS staining analysis (Fig. 1, E, J, and O). No nanogold staining above background was seen in peripheral nerves in IV nanogold-injected animals (Fig. 1, D, E, I, J, N, and O). Low-magnification images of trigeminal nerve (Fig. 1B) and nerve roots emerging from the spinal cord (Fig. 1, G and H) showed significant labeling of the peripheral nerve compared to minimal nanogold deposition within the CNS parenchyma (Fig. 1, F, K, and P). Differential staining intensity between peripheral nerve roots compared to brain (Fig. 1B, asterisk) and spinal cord (Fig. 1G, asterisk) in nanogold-infused tissues clearly demarcates the transition between CNS and PNS. Higher-magnification imaging of cervical nerve roots revealed a lack of gold deposition at the subarachnoid angle. Rather, probe deposition was seen accumulating at the transition from CNS to PNS, known as the RAZ, before flowing into the endoneurium surrounding individual axons (Fig. 1, B, C, G, H, L, and M). Sciatic nerve staining showed the highest concentration of gold in the perineurium (Fig. 1, L and M), with clear labeling of endoneurium and nodes of Ranvier observed at 6 hours postinfusion versus clear controls (Fig. 1, D, E, I, J, N, and O). Quantification of enhanced gold staining was determined by black pixel intensity using the Aperio ImageScope software, allowing identification of saturated (Fig. 1B, red line) from linear (Fig. 1L, marked linear), and background areas of staining set by PBS control tissues (Fig. 1, D, I, and N) confirmed higher probe deposition in the PNS compared to the CNS in all tissues (Fig. 1, F, K, and P).

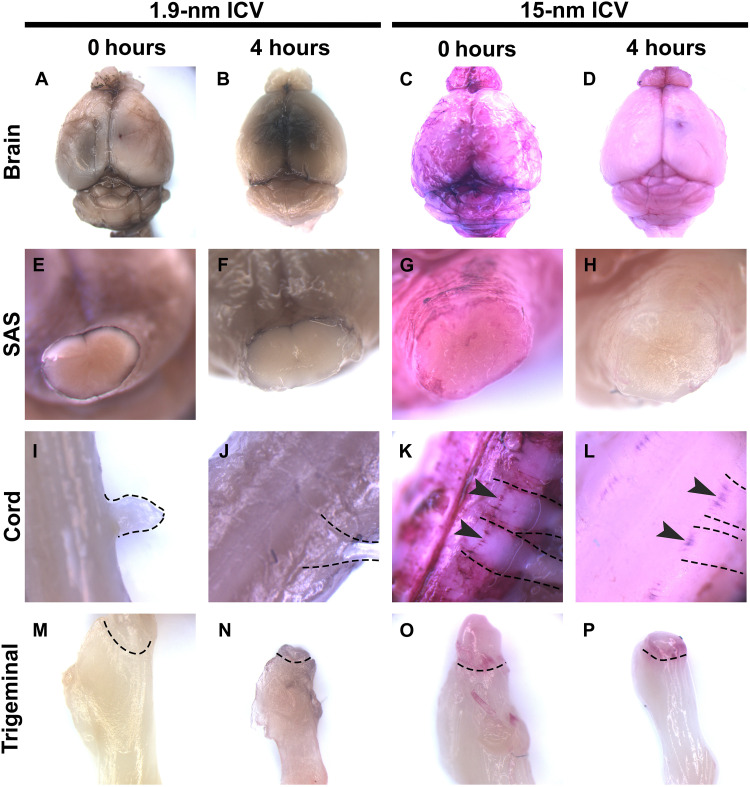

Differential probe deposition patterns reveal size dependence of CSF solute transport

Previous studies defining meningeal lymphatics within the dura used 15-nm fluorescent Q-dots, while studies defining glymphatics used a variety of tracers ranging from 2 to 3 nm to >32 nm. However, these studies did not assess transit to peripheral nerves (5, 6). Early studies on CSF flow used large particles such as India Ink, to evaluate flow into peripheral nerves (18, 19). To assess the effect of particle size on nanogold transport from CNS to PNS, we infused 1.9- and 15-nm nanogold into the lateral cerebral ventricle of mice as described above and analyzed probe deposition patterns in brain, spinal cord, and trigeminal nerve 0 and 4 hours after infusion without gold-enhanced staining (Fig. 2). Note that 1.9-nm gold solution is black, while 15-nm nanogold solution is red via light microscopy without enhancement. Development of tissue sections with gold-enhanced staining results in black deposits via light microscopy for both sizes of nanogold tracer. At 0 hours postinfusion, overall levels of staining within the brain and SAS of transected spinal cord were similar for both nanogold sizes (Fig. 2 A, C, E, G, I, and K) versus PBS-infused controls (fig. S3). However, by 4 hours postinfusion, the amount of 15-nm nanogold was reduced compared to 0 hours postinfusion, demonstrating clearance from the CNS (Fig. 2, C versus D, and G versus H and K versus L). In contrast, infused 1.9-nm nanogold was retained within the whole brain with visible darkening of the parenchyma by 4 hours postinfusion (Fig. 2, A versus B). The 1.9-nm gold was also retained better within the spinal cord 4 hours postinfusion (Fig. 2, Eversus F and I versus J ). Both 0 and 4 hours infused 1.9-nm axial view spinal cords show an almost uniform staining, continuing into peripheral nerves (Fig. 2, I and J), whereas 0 hours infused 15-nm nanogold spinal cord axial views show accumulation of tracer around emerging peripheral nerve roots (Fig. 2K). By 4 hours postinfusion, spinal cord parenchyma has mostly cleared of 15-nm nanogold with areas of tracer accumulation at roots of emerging peripheral nerves remaining (Fig. 2L). This phenomenon was described in early CSF tracer studies as “cuffing” (18, 19). Analysis of emergent trigeminal nerves shows evidence of 1.9-nm nanogold darkening of the nerve by 4 hours postinfusion (Fig. 2, M versus N). In 15-nm nanogold-infused tissues, the trigeminal nerve shows cuffing at both 0 and 4 hours postinfusion (Fig. 2, O and P).

Fig. 2. Larger probe forms cuffing at CNS-PNS transitions.

Aurovist 1.9- or 15-nm probes were infused into the lateral cerebral ventricle of fully anesthetized mice. CNS and PNS tissues were harvested 0 hours or 4 hours after probe infusion and imaged without gold enhancement. Whole brains were imaged with 1.9 nm (A) 0 hours or (B) 4 hours postinfusion. Brains infused with 15-nm probe for (C) 0 hours or (D) 4 hours. SAS of the brain stem following 1.9-nm probe infusion for (E) 15 min or (F) 4 hours. The SAS of brainstems following 15-nm probe infusion of (G) 0 hours or (H) 4 hours. Spinal cords with protruding nerve roots from animals injected with 1.9 nm (I) 0 hours or (J) 4 hours postinfusion. Spinal cords with protruding nerve roots from animals injected with 15-nm nanoprobe (K) 0 hours or (L) 4 hours postinfusion. Dotted lines mark nerve roots. Arrowheads mark ink cuffs. Trigeminals (M) 0 hours or (N) 4 hours postinfusion of 1.9-nm nanoprobe. Trigeminals (O) 0 hours or (P) 4 hours after 15-nm nanoprobe infusion. Dotted lines mark ink cuffs. Panels have a minimum N = 3.

We sectioned and performed enhanced gold staining on 1.9- and 15-nm nanogold-infused tissues for more sensitive localization of infused nanogold (Fig. 3). CNS tissue sections from 1.9- and 15-nm ICV animals with enhanced gold staining showed very similar nanogold distribution at 0 hours as was seen in whole tissues (Fig. 3, A, C, E, and G). At 0 hours postinfusion, both sizes of nanogold were primarily located in meningeal layers with minimal staining of parenchyma. By 4 hours postinfusion, 1.9-nm nanogold was well distributed throughout the parenchyma of brain and spinal cord with staining maintained in meninges (Fig. 3, B and F). Larger 15-nm nanogold showed minimal distribution within the parenchyma of brain and spinal cord with clearing of meningeal layers for both tissues by 4 hours (Fig. 3, D and H). We next examined peripheral nerves isolated 4 hours postinfusion with 1.9- and 15-nm nanogold. The 1.9-nm infused trigeminal, cervical dorsal/ventral nerve roots continuing into the brachial plexus and the sciatic nerve all showed areas of saturated nanogold staining as seen previously (Fig. 3, I to M). Only the trigeminal nerves of 15-nm infused animals showed trace amounts of gold staining near the CNS to PNS transition (Fig. 3N). Neither spinal roots nor sciatic nerves of 15-nm infused animals showed staining above PBS-infused control background at 4 hours (Fig. 3, O to R, and fig. S4). These results indicate size restriction of CSF nanogold distribution in peripheral nerves.

Fig. 3. CSF flow route is dependent on probe size.

The 1.9- or 15-nm nanogold tracers were infused into the lateral cerebral ventricle of fully anesthetized mice. CNS and PNS tissues were harvested 15 min or 4 hours after probe infusion and processed with GoldEnhance. Coronal sections of brain from animals injected with 1.9 nm (A) 0 hours or (B) 4 hours postinfusion. Coronal sections of brain from animals injected with 15-nm nanoprobe (C) 15 min or (D) 4 hours postinfusion. Arrowheads mark positively staining brain tissue. Spinal cords from animals injected with 1.9 nm (E) 0 hours or (F) 4 hours postinfusion. Spinal cords with protruding nerve roots from animals injected with 15-nm nanoprobe (G) 0 hours or (H) 4 hours postinfusion. Arrowheads mark meninges. “*” marks CNS to PNS transition in all images. (I) Trigeminal nerve from 1.9-nm infused animals. High-magnification image of (J) dorsal nerve root and (K) ventral nerve root from (L). (L) Spinal nerve roots from 1.9-nm nanoprobe-infused animals. (M) Sciatic nerve from 1.9-nm nanoprobe-infused animal. (N to R) Peripheral nerves taken from animals 4 hours after 15-nm nanoprobe infusion. “*” marks CNS to PNS transition in all images. (N) Trigeminal nerve from 15-nm infused animals. High-magnification image of (O) dorsal nerve root and (P) ventral nerve root from (Q). (Q) Spinal nerve roots from 15-nm nanoprobe-infused animals. (R) Sciatic nerve from 15-nm nanoprobe-infused animal. Gn, ganglion. Panels have a minimum N = 3.

Nanogold infused into the CSF transits the length of peripheral nerves

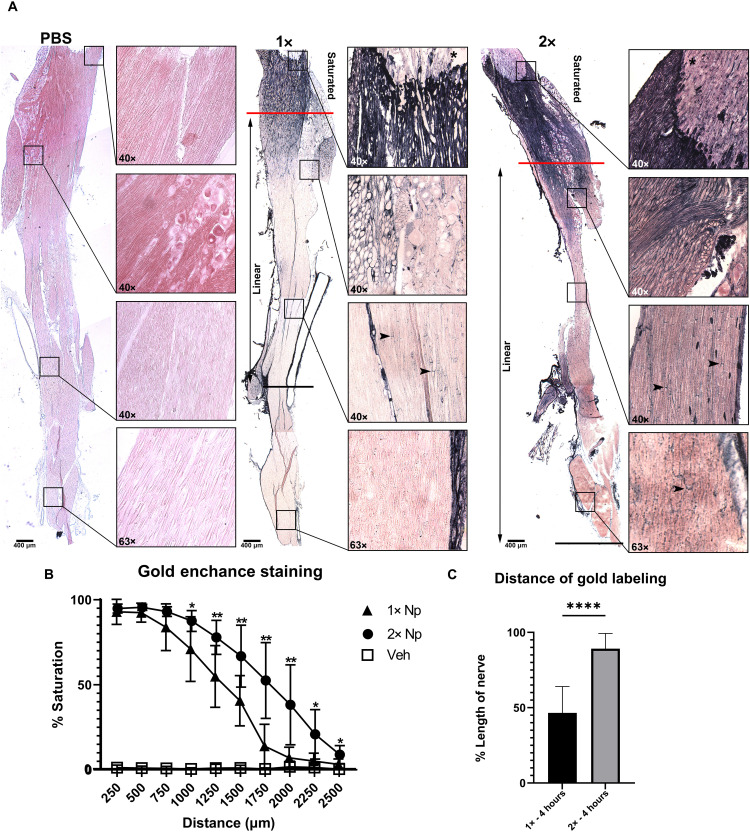

Our initial studies demonstrated extensive distribution of 1.9-nm nanogold in proximal regions of endoneurium but did not show nanogold distribution throughout an entire peripheral nerve. To increase sensitivity of detection, we performed injections with 1× and 2× concentrations of nanoprobe in a 10-μl infusion bolus with PBS-infused tissues as controls. In previous gold-enhanced staining, we stained for one quarter of the manufacturer’s suggested staining time to avoid excessive saturation, allowing for improved morphological assessment. To test for complete distribution of nanogold throughout the trigeminal nerve, we enhanced staining for the recommended 20 min. Whole trigeminal nerves (from CNS junction at the brain following the maxillary nerve branch to where it innervates the cheek) were assessed from 1× and 2× concentration nanogold-infused versus PBS-infused control animals (Fig. 4). Probe deposition within the perineurium traversed the entire length of the trigeminal nerve in both 1× and 2× concentrations. Doubling the concentration of nanoprobe infused into animals doubles the distance of probe deposition within the endoneurium (identified by labeling for the nodes of Ranvier) extending throughout the entire dissected trigeminal nerve (Fig. 4, A and C). In addition, 2× nanogold-infused animals had significantly larger “saturated” staining zones defined by the maximum number of strong positive pixel values measured by the Aperio ImageScope software. Following the saturated staining was a linear decrease in staining intensity extending to the end of the dissected trigeminal nerves. Trigeminals from 1× nanogold-infused animals reached background staining levels well before the end of the nerves (Fig. 4B). Collectively, these results indicate that visualization of CSF flow is concentration dependent, allowing for identification of nodal labeling to the distal ends of trigeminal nerves.

Fig. 4. CSF flow of nanogold is concentration dependent.

The 1 mg (1×) and 2 mg (2×) of nanogold was infused into the lateral cerebral ventricle. Trigeminal nerves were harvested 4 hours after infusion and stained with gold enhancement for 20 min. The 5× images were placed together to show the distance of saturated staining (red line) [(A) and (B)]. The distance of CSF flow was determined by measuring the distance for the last nodal labeling seen from the transition marked by a black line [(A) and (C)]. The linear zone marks the decrease in concentration of nanoprobe from the end of the saturated zone to the last nodal labeling seen [(A) and (B)]. For each concentration, 40× and 63× inlays show representative staining at four distances. (A) PBS-infused nerves only exhibit background staining through the length of the nerve. (B) The saturated zone on 1× concentration nerves reaches approximately 750 μm from the transition, and the last nodal staining was seen on average halfway along the nerve. The saturated zone on 2× concentration nerves was on average 1000 μm from the transition. (C) Nodal staining was seen for the length of the 2× nerve. Unpaired t test was performed to determine statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ****P < 0.0001) Panels have a minimum N = 4.

CSF flow from CNS to peripheral nerves is contiguous and continuous

CSF flow within the CNS is known to be a slow, low-pressure system when compared to the vascular system (8, 9, 38), which would suggest that CSF-driven distribution of nanogold may require substantially longer times than IV distribution. Thus, we next sought to determine the effect of time on CSF nanogold flow within peripheral nerves. We performed a time course analysis to determine peak staining intensity for peripheral nerves following a bolus of 1.9-nm gold at 1× concentration infused into the lateral ventricle with PNS and associated CNS tissues harvested at 0, 2, 4, or 6 hours postinfusion (Fig. 5). Figure S6 shows pixel intensity quantification of nanogold distribution and confirms that increased distance from the infusion site results in decreased maximal staining, requiring increased time for peak staining. The highest concentrations of nanogold were seen within the CNS structures. The brain and spinal meninges label immediately following infusion (Figs. 3, A and E, and 5G and fig. S2). However, staining within peripheral nerves varied based on distance from the infusion site (Fig. 5 and fig. S6). The highest staining within peripheral nerves is seen within the skull, proximal to the injection site, diluting as it flowed distally beyond the spinal nerve roots, with the lowest intensity of the nerves assessed seen in the sciatic nerves (Fig. 5 and figs. S6 and S7). Trigeminal nerve staining initiated by 0 hours postinfusion and peaked at 2 to 4 hours postinfusion (Fig. 5, B to F, and fig. S6). The transition from CNS to PNS (measured by 0 to 200 μm from the start of the transition) reached its maximum by 2 hours, while the endoneurial staining (measured by 200 to 400 μm from the start of the transition) did not equilibrate with the transitional labeling until 6 hours postinfusion (Fig. 5, B to F, and fig. S6). Spinal nerve roots began labeling 0 hours postinfusion albeit at a lower level than the trigeminal (Fig. 5, G, K, and Q to T). The most significant change in nerve root staining was seen between 2 and 4 hours postinfusion (Fig. 5K and fig. S6B), exhibiting peak nanogold staining at 4 hours postinfusion (Fig. 5, G to K, and fig. S6). The cervical nerve root and each consecutive nerve root get a lesser initial concentration leading to a lower overall staining intensity, like that seen in the sciatic nerve (Fig. 5 and figs. S6 and S7). Figure S7 (A to E) shows an additional series of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar nerve roots progressing down the spinal cord with additional examples of peak staining times increasing with distance from the infusion site. Staining of distal sciatic nerve also peaked at 4 to 6 hours, similar to the lumbar roots which combine to form the sciatic nerve (Fig. 5, J to P and Q to T). The 1× nanogold infusion peaks between 4 and 6 hours. Doubling (2×) the concentration of nanogold infusion shortens the time of peak sciatic staining to between 2 and 4 hours postinfusion (fig. S7, F and G). Peak staining intensity of spinal nerve roots decreased with distance from the infusion site, suggesting continual dilution and efflux of nanogold over time and distance traveled from the infusion site (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. CSF flows through peripheral nerves in a time- and distance-dependent manner.

The 1.9-nm nanogold. Tracer was infused into cerebral lateral ventricle. CNS and PNS tissues were harvested 0, 2, 4, or 6 hours postinfusion, and then cryosections were GoldEnhanced. (A) Schematic of gold diffusion through central and PNS tissues; intensity of black is representative of relative amounts of nanogold and depicts progressive dilution of probe. (B to F) Trigeminal nerves from animals (B) 0 hours, (C) 2 hours, (D) 4 hours, or (E) 6 hours after nanoprobe injection. (G to K) Cervical spinal nerve roots of Aurovist-injected animals (G) 0 hours, (H) 2hours, (I) 4 hours, or (J) 6 hours postinjection; an “*” marks the transition from CNS to PNS in all panels. (L to P) Sciatic nerves of Aurovist-injected animals (L) 0 hours, (M) 2 hours, (N) 4 hours, or (O) 6 hours postinjection. Gn, ganglion. [(F), (K), and (P)] Average positive pixel density measured in trigeminal (F), spinal nerve root (K), and sciatic nerve (P) at each time point. (Q to T) Overall staining at each time point was quantified and compared in each tissue. Trigeminal nerve had the highest overall staining seen at each time point. Unpaired t test was performed to determine statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and **** P < 0.0001). Panels have a minimum N = 4. ns, not significant.

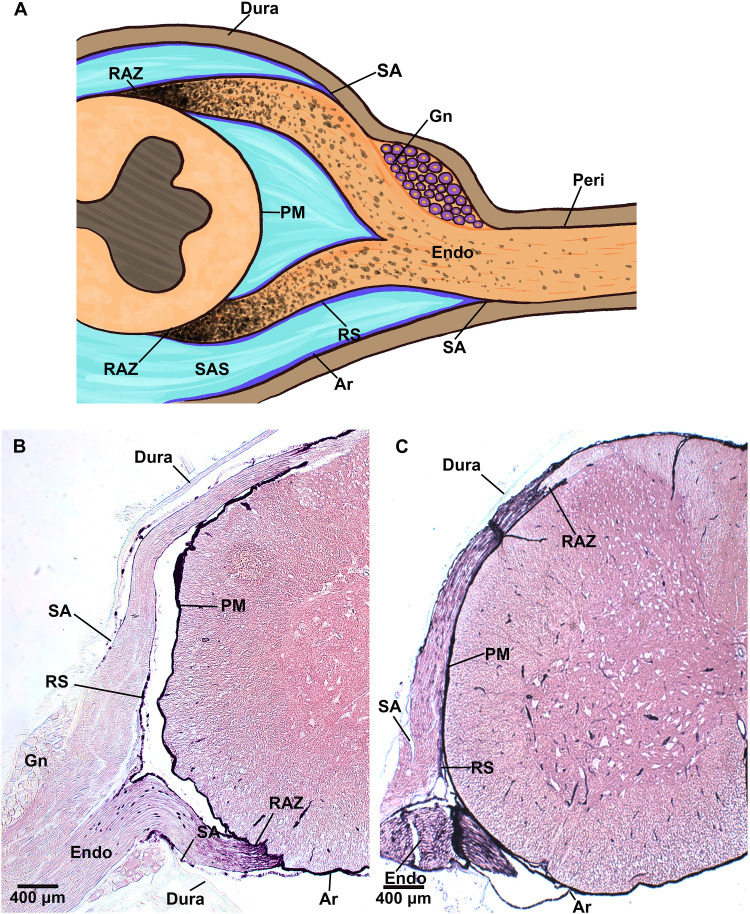

Nanogold transits from CNS to PNS at the RAZ

The presence of ENF with similar composition to CSF has been suggestive of CSF flow to peripheral nerves, but CSF flow to the PNS has not been conclusively demonstrated (15–20). Multiple theories have been advanced for where the CSF would transit into peripheral nerves—the most prominent suggestions being the junction of the subarachnoid angle or the RAZ (Fig. 6A) (4, 16, 18, 19, 39). Nanogold distribution patterns at the CNS to PNS junction reflect the route of CSF solute transport. Therefore, we examined the deposition of 1.9-nm nanogold at spinal nerve roots as they emerge from the spinal cord at 0 and 6 hours after ICV infusion (Fig. 6, B and C). Nanogold staining always initiated and extended from the RAZ although the meninges of the spinal cord were saturated with nanogold (Fig. 6, B and C).

Fig. 6. CSF solute enters PNS at nerve RAZ.

The 1.9-nm nanogold tracer was infused into the lateral cerebral ventricle of fully anesthetized mice. CNS and PNS tissues were harvested (A) 0 hours or (B) 6 hours postinfusion and processed with GoldEnhance. (C) Schematic of CNS/PNS spinal junction with structures labeled as PM, pia mater; Ar, arachnoid mater; DM, dura mater; SA, subarachnoid angle; RS, root sheath; Endo, endoneurium/endoneurial region; Gn, ganglion.

The junction of CNS to PNS is apparent where the trigeminal nerve (PNS) emerges from the brainstem via the pons (CNS) and where the spinal nerve roots (PNS) branch from the spinal cord (CNS). At the CNS/PNS transition, nanogold accumulated in both cranial peripheral nerves and spinal nerves (Fig. 7). At the cranial CNS/PNS transition, increasing gold accumulation over time was indicated by black gold deposits at cells jutting into the CNS, where the demarcation (red line) between CNS and PNS is most clear at 2 to 6 hours postinfusion (Fig. 7, A to H). At the junction between peripheral nerve and the brain, nanogold distribution into the PNS appears to start at the outside edges of the nerve and fills in more toward the center of the nerve with increasing time; this is especially apparent in comparing trigeminal junctions between 0- and 2-hour tissues (Fig. 7, A and B and E and F). Endoneurial labeling was seen peripheral to the staining at the transition at 0 hours (Figs. 5B and 7, A and E). More distal portions of the peripheral nerve body (beyond the initial accumulation point) continue to fill over time as the nerve body becomes saturated with nanoprobe (Fig. 7, E to H, and fig. S6). Probe distribution at the spinal nerve roots reveals the RAZ as the route of probe entry into spinal nerves. Similar patterns of staining in the trigeminal were seen at the spinal CNS/PNS transition (Fig. 7, I to P). Here, individual axons emerging from the spinal cord parenchyma to the rootlet are darkly stained compared to the adjacent CNS parenchyma in both dorsal and ventral nerve roots. We observe heightened nanogold distribution along cells of the PNS compared to the CNS parenchyma. Quantification of nanogold staining showed a consistent trend for ventral roots to stain more than dorsal roots across all times and samples but did not reach statistical significance (fig. S8).

Fig. 7. CSF solute accumulates in PNS at CNS/PNS junction.

The 1.9-nm nanogold tracer was infused into the cerebral lateral ventricle. PNS tissues were collected at 0 hours, 2, 4, or 6 hours postinfusion, and then cryosections were GoldEnhanced. (A to D) Trigeminal nerves from animals (B) 0 hours, (C) 2 hours, (D) 4 hours, or (E) 6 hours after nanoprobe injection; gold accumulates at CNS-PNS transition as demarcated with red dotted line. (E to H) Low-magnification images of trigeminal nerves (E) 0 hours, (F) 2 hours, (G) 4 hours, or (H) 6 hours after nanoprobe injection. CNS to PNS junction is demarcated by “*.” (I to L) Dorsal thoracic nerve root from animals (I) 0 hours, (J) 2 hours, (K) 4 hours, or (L) 6 hours after nanoprobe injection after ventricular injection. Probe is concentrated in nerve roots. Closed arrow marks CNS meninges and PNS connective tissue coverings. (M to P) Ventral spinal nerves roots (M) 0 hours, (N) 2 hours, (O) 4 hours, or (P) 6 hours after nanoprobe injection. Nanogold is present within the endoneurium, revealing nodes of Ranvier (open arrowheads). Panels have a minimum N = 4.

Nanogold efflux from the CNS post-ICV infusion follows established patterns for CSF outflow

To further validate our CSF tracing results, we evaluated probe deposition in established CSF efflux spaces previously described (7, 11, 40, 41). Tracers are generally cleared from the CNS through the lymphatic and circulatory systems, with ultimate clearance occurring via kidney filtration and concentration in the bladder for excretion (2, 7). We observed ICV-infused nanogold distribution followed expected distribution patterns within the CNS (fig. S2). Nanogold clearance from nervous tissues also followed the expected path in cervical lymph nodes of animals shortly after ICV infusion (Fig. 8, A to D) but with delayed kinetics versus IV-infused nanogold (Fig. 8, E to H). IV-infused animals had clear bladders and kidneys within an hour, with minimal residual nanogold seen in cervical lymph nodes and spleen by 6 hours (Fig. 8, E to H). In contrast, animals receiving ICV infusion of nanogold had substantial quantities of nanogold in cervical lymph nodes, spleen and kidney, and had black bladders from the concentrated gold after 6 hours (Fig. 8, A to D). These data show that nanogold is cleared from the nervous system in the same manner as previous CSF efflux studies (2, 7, 10).

Fig. 8. Nanoprobe clearance is delayed in nanogold-injected animals.

CSF is thought to be effluxed from the CNS predominately through the lymphatic system with subsequent efflux to the vascular system; final clearance from the body occurs through excretion in the urinary system. To assess clearance of nanogold from the CSF, C57BL/6 mice were injected with 1.9-nm nanogold tracer (0.1 mg/μl) into the ICV (A to D), IV (E to H) through the tail vein, compared to animals injected with an equal volume of PBS into the lateral cerebral ventricle (I to L). Tissues were harvested at 6 hours postinfusion, cyrosectioned, and GoldEnhanced. (A) Lymph nodes (LN), (B) spleen [red pulp (RP) and white pulp (WP)], (C) kidney, and bladder (D) of tissues from ICV-infused animals. (E) Lymph nodes, (F) spleen, (G) kidney, and bladder (H) of tissues from IV-infused animals. (I) Lymph nodes, (J) spleen, (K) kidney, and bladder (L) of tissues from animals infused with PBS into lateral cerebral ventricle. Panels have a minimum N = 4.

Electron microscopy demonstrates CSF-infused nanogold delivery to peripheral nerve layers including delivery to axoplasm of peripheral nerves

Gold-enhanced staining for light microscopy generates dark deposits that can obscure histologic detail, making precise identification of labeled cells difficult. Therefore, we used transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for morphological cell identification and ultrastructural localization of nanogold distribution within peripheral nerves (Figs. 9 and 10). EM microscopy of peripheral nerve axoplasm showed delivery of nanogold tracer infused into the CSF of brain ventricles, including within axoplasm of distal sciatic nerves (Fig. 10, E to J). Nanogold within axoplasm was localized on neurofilaments and within mitochondria of neurons. Following enhancement, gold deposit sizes, identified by TEM, vary based on the amount of nanogold present. Perineurial fibroblasts (PF) of the trigeminal nerve were identified by the lack of a basement membrane. The trigeminal perineurial fibroblasts contained sufficient nanogold that a minimal enhancement for EM resulted in extremely large deposits and numerous small to medium deposits creating a nearly continual “river” of intracellular nanogold, compared to adjacent perineurial cells (Fig. 9, B and C, and fig. S9A). Perineurial cells, identified by the presence of a basement membrane, did contain nanogold but at lower levels compared to fibroblasts (Fig. 9, B and C, and fig. S9, A to C). Analysis of distal lumbar nerve roots (Fig. 9F) and the sciatic nerve (Fig. 9G) showed the same overall staining pattern as trigeminal (Fig. 9E) but with less nanogold found overall. The most obvious difference was the lack of extremely large gold deposits in the PF of the sciatic nerve root, likely due to dilution and efflux of the nanogold bolus as it flows distally (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 9. Electron microscopy identifies CSF flows in the connective tissue coverings of peripheral nerves.

(A) Schematic of peripheral nerve (PN) that contains multiple fascicles enclosed by the perineurium (Per), which bundles multiple axons (Ax) and their surrounding Schwann cells (Sch); individual axons are located within the endoneurium (En). (B) Cross section of trigeminal nerve 4 hours after infusion of 2-mg gold nanoprobe into the cerebral lateral ventricle. Nanogold is visible as black particles in fibroblasts (white outline; arrow) within the perineurium of the trigeminal after gold enhancement; an adjacent a perineurial cell (black outline; open arrowhead) contains little gold. (C) Trigeminal perineurial fibroblast (white outline; arrow) with large nanogold deposits. (D) Endoneurial fibroblasts (arrow) in the lumbar nerve root with intracellular nanogold visible following gold enhancement (arrowhead). (E to G) Endoneurial nanogold located in the endoneurial space surrounding myelinated (My) and unmyelinated (Unmy) axons of (E) trigeminal, (F) lumbar nerve root, and (G) sciatic nerves. The endoneurial space is demarcated with dashed lines. Nanogold deposition is seen among collagen fibers in the endoneurium [(F) and (G)].

Fig. 10. CSF penetrates Schwann cells, down to the axonal level.

(A) Schematic of peripheral nerve (PN) that contains multiple fascicles enclosed by the perineurium (Per), which bundles multiple axons (Ax) and their surrounding Schwann cells (Sch). Arrowheads mark examples of nanogold labeling in all panels. Examples of nanogold located in the Schwann cell (open arrowheads) and axon (closed arrowheads). (B to D) Nanogold found in the cytoplasm of Schwann cells found in the trigeminal [(B) and (C)] and Sciatic nerve (D). (E to J) Nanogold infused into the CSF of mice is found at the axonal level, located among the neurofilament of trigeminal nerves [(E) and (F)], lumbar nerve roots [(H) and (K)], and sciatic nerves [(G), (I), (J), (L), and (M)]. Halo’s produced by electron refraction was used to verifying nanogold within peripheral axons [(H) to (J)] and corresponding halos (K to M).

The highest overall levels of nanogold within endoneurium were found in the fluid-filled endoneurial space (Fig. 9, E to G), with clear deposition in association with the collagen fibrils (Fig. 9, F and G, and fig. S10). Tissue and cellular components of endoneurium include small blood vessels, endoneurial fibroblasts, macrophage and mast cells of the immune system, and Schwann cells wrapped around axons. Schwann cells had the most intracellular nanogold (Fig. 10, B to D). Nanogold deposition in nonmyelinating Schwann cells was sparse compared to that in myelinating Schwann cells (fig. S12). As in the perineurium, endoneurial fibroblasts contained abundant nanogold deposits (Fig. 9, E to G). Nanogold was also found within endoneurial macrophages (fig. S13) as well as in a variety of intracellular/extracellular vesicles, including extracellular vesicles seen within endoneurial blood vessels (fig. S14). EM revealed a similar nanogold association with extracellular matrix structures in the spinal cord as well (fig. S11). EM of control neural tissues exhibited no nanogold staining (fig. S15). Smaller gold deposits were routinely confirmed by electron reflection to differentiate gold particles from normal dark structures (Fig. 10, H to J and K to M). Overall, the EM results agree with the light microscopy staining patterns, providing in-depth characterization of nanogold localization within peripheral nerves (Figs. 1 to 6 and fig. S16).

DISCUSSION

Interest in the CSF system has grown with a series of discoveries in recent years, with research revealing previously unknown roles for CSF in the health and homeostasis of CNS tissues (5, 6, 14, 42–44). The nervous system lacks traditional lymphatics and is protected by the BBB, restricting the free movement of molecules (45, 46). CSF provides physical cushioning while delivering nutrients and removing waste for CNS tissues (12). Conversely, little is known of the mechanisms maintaining peripheral nerve homeostasis. The prevailing understanding that CSF flow is restricted within the CNS was established by a variety of vital dye studies using tracers of varying sizes, which were unable to be enhanced for more sensitive detection (1, 4, 5, 37, 47, 48). These studies provided the basis for the current dogma, inherent in the name CSF, that limits CSF flow and function to bounds set by the meninges of the brain and spinal cord without substantial contribution to PNS maintenance and function (4, 8, 49).

The nervous system has traditionally been segregated into distinct central and peripheral components. However, our work demonstrates the interconnectedness of the nervous system through the continuity of CSF flow from CNS into peripheral nerves and suggests an important role for CSF in PNS maintenance (8, 50). This is exemplified by the contiguous distribution of CSF-infused nanogold tracer from the lateral ventricle to CNS meninges as well as to PNS perineurium, endoneurium, and axoplasm of distal peripheral nerves (diagramed in Fig. 1A). The perineurium exhibits the quickest and most intense staining in the peripheral nerve where perineurial fibroblasts contain an abundance of intracellular nanogold visible as large, intracellular gold deposits (Figs. 5 and 9, B and C). The more abundant perineurial cells, however, contain far less intracellular nanogold, likely due to the known barrier function of perineurial cells that limit free transport into and out of the endoneurium (Fig. 9, B and C, and fig. S9). We further show ICV-infused nanogold flows into ENF spaces of the PNS, which exhibited abundant extracellular nanogold deposition, specifically in the loose collagen fiber matrix where ENF is found (Figs. 1, 3 to 7, and 9, E to G). Retained within the endoneurium by the “blood-nerve” barrier, ENF is similar in composition to CSF and is thought to maintain proper pressure regulation for peripheral nerve health. However, the site of ENF production is not well defined (15, 17–20, 51–53). The proximal to distal staining gradients of ICV-infused nanogold and the presence of nanogold in the free-flowing spaces of the endoneurium demonstrate the continuity of the CSF flow system from CNS to PNS and identify CNS-derived CSF as a source for ENF. Further, accumulations of nanogold were routinely observed at the nodes of Ranvier, and Schwann cells exhibited a high degree of intracellular nanogold (Figs. 1, C, L, and M, 4 and 10). The nodes of Ranvier are a site for ionic influx required for the generation of action potentials and are a site of nutrient transporters. Accumulation of nanogold at the nodes suggests the importance of CSF in the propagation of signals down axons along the entire length of peripheral nerves (Fig. 4) (54). Moreover, localization of nanogold in the endoneurium, including nodes of Ranvier, highlights a possible role for CSF in nutrient delivery and waste clearance in peripheral nerves. The presence of ICV-infused nanogold in the axoplasm of peripheral nerves, including axons of the distal sciatic nerve, supports this proposition (Figs. 9 and 10). Schwann cells likely aid in nutrient delivery to axons from the endoneurial space. CSF solutes may gain access to axons through the nodes of Ranvier and Schmidt Lanterman clefts, resulting in gold detection within peripheral axons. Nanogold deposition within peripheral axons suggests that CSF flow in the periphery may be integral for peripheral axon maintenance.

Our results reveal that 1.9-nm gold infused into CSF enters the PNS through the RAZ rather than at the subarachnoid angle, in contrast to observations in previous studies (Figs. 1 to 7) (18, 19). At the RAZ, nanogold is observed to accumulate starting at the edges of the nerve, suggesting continuity between the transition and the SAS (Figs. 5 and 7). Loading at the RAZ appears to be required for flow into the endoneurium, as staining in the endoneurium is only seen distal to a labeled transition (Fig. 7, A to H). Axons emerging from the CNS to the PNS are contiguous across the transition from CNS to PNS within the RAZ. However, the CNS to PNS transition entails a key switch in the myelinating cell type from oligodendrocytes in the CNS to Schwann cells in the PNS (50). The low levels of nanogold in CNS tissues and the cellular staining identified spanning the RAZ suggest that the change in myelinating cells may play a role in entry of CSF solutes into peripheral nerves. The RAZ additionally creates a size-restrictive barrier where larger 15-nm gold formed a “cuff” at the transition in both the trigeminal and spinal nerve roots but was unable to enter the PNS in any appreciable amount (Fig. 2). This apparent size restriction likely explains the similar cuff originally observed by Brierley (Figs. 2, K, L, O, and P, and 4) (19). Unlike previous studies, however, the small size of the 1.9-nm gold enables its entry into the PNS (Figs. 1 to 10). Size restriction is likely to be an important feature controlling particle flow within the nervous system as evinced by similar size restrictions reported for the BBB/BNB, glymphatic systems, and other potential flow barriers (5, 55–57).

The presence of nanogold in the endoneurium identifies endoneurial space as the site of CSF flow from the CNS to the PNS. The endoneurium is bound by the perineurium and consists of a loose fluid-filled connective tissue space surrounding Schwann cells and axons of peripheral nerves. Such a “packed” structure would help explain the slow time and size-dependent process of CSF-infused nanogold distribution in peripheral nerves (Figs. 2, 3, 5, and 7). CNS structures label the most intensely the quickest (Figs. 2 and 3 and fig. S2). However, the distribution of nanogold to the PNS is a slower process, with staining dependent on distance from infusion site (Figs. 5 and 7 and figs. S6 and S7). Although the precise mode of peripheral nanogold transport remains to be determined, it is probable that peripheral CSF flow is driven by both convective and pulsatile fluid flow, a model mirrored by what is known of central CSF flow (4, 9, 10, 38). The hydrostatic gradient from CNS to PNS likely drives convective fluid flow from the SAS of the CNS to the endoneurium along peripheral nerves (15, 58). Thus, the endoneurium may be functionally analogous to the SAS of the CNS in supporting CSF flow through peripheral nerves. In addition, the close proximity of peripheral nerves to blood vessels may aid in propagating CSF along peripheral nerves. We must point out that acute surgical procedures in the brain can alter CSF flow and efflux routes in the CNS (59, 60). Our infusion model was validated by ICV infusion at varying concentrations and durations, in both sexes and in both inbred C57BL/6 and CD1 outbred strains of mice (Fig. 1 and fig. S1). The patterns of gold staining observed were consistent across a multitude of animals and cohorts. One must take into account the possibility of tracer movement during fixation and histologic analysis as has been shown in the glymphatic system (59). The nanogold used in our study cannot be fixed so much is lost during histological processing. Therefore, nanogold staining in fixed sections likely underrepresents the amount of nanogold present in the unprocessed tissues. The ability of the nanoprobe to be used for micro-CT imaging represents an interesting possibility for live imaging to gain a more accurate picture of CSF flow dynamics within the entirety of the nervous system.

The presence of a contiguous CSF flow route from the CNS along peripheral nerves has far-reaching implications for peripheral nerve health and neuropathologies. In the CNS, CSF is known to provide cells with a variety of molecules involved in neural metabolism and maintenance and in eliminating waste from neuronal cells (5, 7, 61). A unified CSF flow system encompassing the entire nervous system allows CSF to function consistently to deliver nutrients, remove waste, and provide physical cushioning for all neural tissues. Given the low CSF pressures associated with the neural system, small alterations in CSF production or flow in the CNS would have outsized effects on the health of peripheral nerves. Furthermore, our results suggest that infusion into the CSF compartment may be an efficacious method for direct delivery of drugs and therapeutic agents to peripheral nerves—reliant on the ability to enter the peripheral nerves through the RAZ. We found that in IV-infused animals, nanogold was never detectable beyond the barrier of the perineurium, whereas ICV infusion resulted in direct delivery to the endoneurium of peripheral nerves down to peripheral axons (Figs. 1 and 10, E to M). Therefore, we expect that the development of drugs capable of spanning the central to PNS transition through the observed CSF flow system could be a clinically viable route for slow-release drug delivery to peripheral nerves. The identification of central CSF influence on the PNS and more specifically peripheral axons indicates an interconnectedness of the nervous system that was previously unidentified. This discovery could revolutionize the way we view and treat nervous disorders.

METHODS

Animals

C57BL/6 mice (6 weeks to 5 months) were acquired from Charles River and the Jackson Laboratory. CD1+ mice (5 to 12 weeks) were obtained from the University of Florida (UF) breeding facility and maintained in the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-inspected UF rodent vivarium. Injections were performed in both inbred (C57BL/6) and outbred (CD1+) strains to assess potential variation between strains. Both male and female mice were used to assess variations due to gender; mice were randomly assigned to experimental and control groups. No appreciable differences in nanogold distribution were seen in either strain or sex. All cohorts had a minimum of four animals. For nanogold-infused animals, the success of the infusion was confirmed by histology of the injection site. Animals where the infusion was not within the lateral cerebral ventricle were excluded from test cohorts. All procedures and procedural spaces were approved by the University of Florida’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #202103495 to E.W.S.).

Pre- and postprocedural care

Mice were given pre- and postprocedural analgesia to mitigate pain. Mice were anesthetized, and sufficient depth of anesthetic plane was ensured by loss of foot pedal reflex for all procedures. Procedural sites were denuded by shaving and disinfected by triple scrubbing with iodine and 70% ethanol. All procedural surfaces were sterilized with an approved sterilant. All surgical instruments were sterilized by autoclave before use. Mice were allowed to recover from anesthesia on a heated surface to maintain physiological body temperature. Recent reports have indicated that CSF production rates and subsequent flow rates are influenced on the basis of whether animals are anesthetized and differ with different anesthetics (36, 62). We observe CNS to PNS flow in both fully anesthetized and awake mice. In our experiments, mice at 0-hour time point (harvested directly following ICV injection) exhibit the beginnings of nanogold transition from CNS to PNS in the trigeminal nerve. Mice at all other time points (2, 4, and 6 hours) were allowed to fully recover from anesthesia.

Surgical procedures (infusions)

Ventricular CSF injections

To assess CSF flow patterns, nanogold (Aurovist, Nanoprobes Inc., Yaphank, NY) was infused into the lateral cerebral ventricle of C57BL/6 and CD1+ mice fully anesthetized with Avertin [250 mg/kg, intraperitoneal (IP) delivery]. To access the cerebral lateral ventricle, a mid-sagittal skin incision was made to expose the bregma. A 0.1-mm bur hole was made into the skull, and a 32-gauge canula was then inserted and immobilized in the right ventricle at the following coordinates relative to the bregma: 1 mm lateral, 0 mm antero-posterior, and 2 mm subcranial. Following cannulation, 1.9-nm gold (0.1 mg/μl), 15-nm gold (0.1 mg/μl), or PBS was then continuously infused into the lateral cerebral ventricle using a syringe pump (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) via a Hamilton syringe (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV) connected to the canula with polyethylene tubing at a rate of 1 μl/min. For standard injections (and unless otherwise specified), injections were carried out over 10 min to deliver a total of 1 mg of nanogold (1/40 the manufacturer’s suggested amount for IV administration). For low-volume injections, 2.5 μl of nanogold (0.4 mg/μl) was delivered over 2.5 min for a total of 1 mg nanogold at a flow rate of 1 μl/min.

For negative controls, central and peripheral neural tissues were harvested from either PBS-infused animals or from noninjected animals C57BL/6 or CD1+ mice. For PBS-infused control cohort, PBS was infused into the lateral ventricle of anesthetized mice as described above at flow rate of 1 μl/min; mice were euthanized at 0, 2, 4, or 6 hours postinfusion.

Vascular injections

To assess the contribution of the vascular flow to nanoprobe deposition in neural tissues, a 31-gauge needle was used to perform a bolus injection of 1 mg of nanogold into the tail vein of fully anesthetized mice. Following both cerebral ventricular and vascular injections, animals were euthanized by overdose of Avertin (500 to 800 mg/kg, IP route) and subsequent intracardiac perfusion with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS.

Histology and microscopic analysis

Tissue harvest and processing

For all animals, brains, cranial nerves, spinal cords (with nerve roots), and peripheral nerves (trigeminal and sciatic nerves) were harvested directly following intracardiac perfusion. Tissues were then drop-fixed overnight at 4°C in either 4% PFA in PBS or in Trump’s fixative for light microscopy or electron microscopy, respectively.

Light microscopy

For light microscopy, after 4% PFA fixation, tissues were cryopreserved by sucrose gradient to 30% sucrose (in PBS) and then embedded and frozen in Tissue-Tek optimal cutting temperature Compound (Sakura, Torrance, CA). All tissues were obtained at 5-μm thickness using a Leica CM 1859 cryostat (Leica, Germany) and stored at −20°C until use. Autometallography (GoldEnhance LM, Nanoprobe, Yaphank, NY) was used to enhance infused gold particles within tissues to assess nanogold deposition patterns in tissue sections following manufacturer’s instructions. Unless otherwise indicated, tissues were developed with the enhancing solution for 5 min. Tissue sections were coverslipped with Vectashield Antifade Mounting Media (Vector Laboratories, Newark, CA). Sections were analyzed via light microscopy (Leica DM5500 B, Leica Microsystems, Germany). Images were captured with a Hamamatsu C7780 camera (Hamamatsa, Japan). Enhanced tissue sections were analyzed by a neuropathologist for blinded review.

Electron microscopy

For electron microscopy analysis, harvested tissues were postfixed by immersion in Trump’s fixative [containing 4% PFA and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate containing 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, and 0.25% NaCl (pH 7.24)] (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) overnight at 4°C. Fixed tissue was processed with the aid of a Pelco BioWave Pro laboratory microwave (Ted Pella, Redding, CA). Samples were washed in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.24), postfixed with buffered 2% OsO4 overnight at 4°C, water-washed, and then dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (25% through 100% with 5 to 10% increments) followed by 100% anhydrous acetone. Dehydrated samples were infiltrated with Araldite/Embed [Electron Microscopy Sciences (EMS), Hatfield, PA] and Z6040 embedding primer (EMS, Hatfield, PA) in increments of 3:1, 1:1, 1:3 anhydrous acetone:Araldite/Embed followed by 100% Araldite/Embed. Semithick sections (500 nm) were stained with toluidine blue. Ultrathin sections were collected on carbon-coated Formvar 100 mesh grid (EMS, Hatfield, PA) and poststained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate and lead citrate (EMS, Hatfield, PA). Sections were processed with GoldEnhance EM Plus (Nanoprobe, Yaphank, NY) following the manufacturer’s instructions to enhance nanogold. Sections were examined with a FEI Tecnai G2 Spirit Twin TEM (FEI Corp., Hillsboro, OR), and digital images were acquired with a Gatan UltraScan 2k x 2k camera and Digital Micrograph software (Gatan Inc., Pleasanton, CA). Electron reflection was used to confirm the presence of gold versus nonreflective native structures. Developed tissue sections were analyzed by a neuropathologist for blinded review.

Statistical analysis and data preparation

Sample size determination

To ensure statistically significant data collection while minimizing the use of animals, cohort size was determined by a combination of initial pilot studies to assess variability and two methods of statistical analysis for each experiment based on the pilot results. First, cohorts must satisfy a power analysis at 80% power that allows determination of an effect size (Cohen’s “d”) set at a minimum of 70% at a significance level of 0.05. Second, Mead’s resource equation was used to ensure that the selected cohort sizes will exceed a confidence interval of more than 20 df in their error component to ensure adequate cohort size. Cohort size was adjusted for the use of two strains (C57BL6 and CD1) and both sexes. All statistical calculations were performed with G Power software from Heinrich Heine University, Germany. A minimum n = 15 met the statistical requirements for each previous test condition to achieve a P value of 0.05 across all three variables. We set a minimum cohort size of 10 animals per test condition to ensure our desired rigor with respect to test condition alone. For many figures, examples are shown from single batches showing statistics for the batch shown with the absolute minimum N = 3 allowed. If a given batch had less than three animals excluded for missing the ICV during infusion, then the successful infusions would still be used for the overall cohort analyses.

Randomization

Cohorts were randomized by both strain and sex across all experiments. Data were collected on all animals by ear tag number and subsequently analyzed for strain and sex differences. No significant difference was seen for either sex or strain used.

Blinding

Samples were prepared for analysis with only ear tag numbers for identification. Analysis was performed blind and subsequently decoded by tag number to assess results and statistical differences for test condition, sex, and strain.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The only animals excluded from analysis were animals where the gold infusion clearly missed the lateral ventricle upon dissection. All other animals were analyzed and included in statistical calculations.

Statistical analysis

A minimum of three biological and three technical batches were used due to limitations in animal processing to ensure a full cohort of 10 animals for statistical analysis of image quantification. Trigeminal nerves, cervical spinal nerve roots, and sciatic nerves were sectioned and imaged for quantification following gold-enhanced staining with a 5-min enhancement time, as previously described. Distances of 0 to 200 μm and 200 to 400 μm from the transition were outlined using the Aperio ImageScope software (Leica Biosystems). The area of 0 to 200 μm (where 0 is at the CNS-PNS transition) was used to denote staining at the transition, whereas the area of 200 to 400 μm was used to assess endoneurial staining proximal to the transition. Then, the percent positive staining for each region was computed using the Aperio Positive Pixel Count program (Aperio, Vista, CA, USA). The Positive Pixel count program was configured to detect the purple/black color from the enhancement stain (ImageScope, Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA, USA). The total number of purple/black pixels (positive) divided by the total number of all pixels (positive + negative) was represented as a percent positive staining for all tissues. The percent positive staining values of all batches (biological and technical) at each time point were averaged by distance or by the distances combined. For the analysis of saturated staining, the total number of strong positive pixels was divided by the total number of pixels (positive + negative). Unpaired t test was performed to determine statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001).

All statistical and graphical representations were created using GraphPad Prism version 9. Final images were assembled using Adobe Photoshop with only white balance corrections across images performed on original TIF image files.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Alvarado and N. Machi of the University of Florida, Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research, Electron Microscopy Core RRID:SCR_019146 and Cytometry/Cell and Tissue Analysis Core RRID:SCR_019119.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) RO1 DK 121117 awarded to E.W.S. A.P.L. and A.V.V. are supported by NIDDK T32 DK074367 awarded to E.W.S.

Author contributions: All authors made critical comments related to the intellectual content of the manuscript. Conceptualization: A.P.L., A.V.V., J.E.P., J.V.A.-C., D.E.B.M., O.G.F., W.A.D., A.T.Y., and E.W.S. Methodology: A.P.L., A.V.V., J.E.P., D.E.S., W.A.D., and E.W.S. Investigation: A.P.L., A.V.V., J.E.P., D.E.S., J.V.A.-C., O.G.F., A.T.Y., and E.W.S. Visualization: A.P.L., A.V.V., D.E.S., E.A.S., and E.W.S. Validation: A.P.L., A.V.V., J.E.P., J.V.A.-C., D.A.M., O.G.F., A.T.Y., W.A.D., and E.W.S. Resources: A.P.L., J.E.P., G.A.J.B., and E.W.S. Formal analysis: A.P.L., D.E.S., and E.W.S. Data curation: A.P.L. Project administration: A.P.L. and E.W.S. Supervision: A.P.L., W.A.D., and E.W.S. Funding acquisition: E.W.S. Writing—original draft: A.P.L., A.V.V., J.E.P., A.T.Y., E.A.S., and E.W.S. Writing—review and editing: A.P.L., A.V.V., A.T.Y., G.A.J.B., and E.W.S.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Correspondence and requests for material should be addressed to E.W.S. at escott@ufl.edu.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S16

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Weed L., Studies on cerebro-spinal fluid. No. IV: The dual source of cerebro-spinal fluid. J. Med. Res. 31, 93–118.11 (1914). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proulx S., Cerebrospinal fluid outflow: A review of the historical and contemporary evidence for arachnoid villi, perineural routes, and dural lymphatics. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 78, 2429–2457 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louveau A., Plog B., Antila S., Alitalo K., Nedergaard M., Kipnis J., Understanding the functions and relationships of the glymphatic system and meningeal lymphatics. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 3210–3219 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakka L., Coll G., Chazal J., Anatomy and physiology of cerebrospinal fluid. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 128, 309–316 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iliff J., Wang M., Liao Y., Plogg B., Peng W., Gundersen G., Benveniste H., Vates G., Deane R., Goldman S., Nagelhus E., Nedergaard M., A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 147ra111 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louveau A., Smirnov I., Keyes T., Eccles J., Rouhani S., Peske D., Derecki N., Castle D., Mandell J., Lee K., Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 523, 337–341 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma Q., Ineichen B. V., Detmar M., Proulx S. T., Outflow of cerebrospinal fluid is predominantly through lymphatic vessels and is reduced in aged mice. Nat. Commun. 8, 1434 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.A. C. Guyton, J. E. Hall, Textbook of Medical Physiology (E. Saunders, ed. 11, 2005), pp. 764–767.

- 9.Johanson C., Duncan J., Klinge P., Brinker T., Stopa E., Silverberg G., Multiplicity of cerebrospinal fluid functions: New challenges in health and disease. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 5, 10 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmussen M. K., Mestre H., Nedergaard M., Fluid transport in the brain. Physiol. Rev. 102, 1025–1151 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh L., Zakharov A., Johnston M., Integration of the subarachnoid space and lymphatics: Is it time to embrace a new concept of cerebrospinal fluid absorption? Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2, 6 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weller R. O., Sharp M. M., Christodoulides M., Carare R. O., Møllgård K., The meninges as barriers and facilitators for the movement of fluid, cells and pathogens related to the rodent and human CNS. Acta Neuropathol. 135, 363–385 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rustenhoven J., Drieu A., Mamuladze T., de Lima K. A., Dykstra T., Wall M., Papadopoulos Z., Kanamori M., Salvador A. F., Baker W., Lemieux M., da Mesquita S., Cugurra A., Fitzpatrick J., Sviben S., Kossina R., Bayguinov P., Townsend R. R., Zhang Q., Erdmann-Gilmore P., Smirnov I., Lopes M. B., Herz J., Kipnis J., Functional characterization of the dural sinuses as a neuroimmune interface. Cell 184, 1000–1016.e27 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papadopoulos Z., Herz J., Kipnis J., Meningeal lymphatics: From anatomy to central nervous system immune surveillance. J. Immunol. 204, 286–293 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizisin A., Weerasuriya A., Homeostatic regulation of the endoneurial microenvironment during development, aging and in response to trauma, disease and toxic insult. Acta Neuropathol. 121, 291–312 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weerasuriya A., Mizisin A., The blood-nerve barrier: Structure and functional significance. Methods Mol. Biol. 686, 149–173 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pettersson C., Sheaths of the spinal nerve roots: Permeability and structural characteristics of dorsal and ventral spinal nerve roots of the rat. Acta Neuropathol. 85, 129–137 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brierley J., The penetration of particulate matter from the cerebrospinal fluid into the spinal ganglia, peripheral nerves, and perivascular spaces of the central nervous system. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 13, 203–215 (1950). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brierley J., Field E., The connexions of the spinal sub-arachnoid space with the lymphatic system. J. Anat. 82, 153–166 (1948). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pettersson C., Drainage of molecules from subarachnoid space to spinal nerve roots and peripheral nerve of the rat: A study based on Evans blue-albumin and lanthanum as tracers. Acta Neuropathol. 86, 636–644 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonald N. Q., Lapatto R., Rust J. M., Gunning J., Wlodawer A., Blundell T. L., New protein fold revealed by a 2.3-Å resolution crystal structure of nerve growth factor. Nature 354, 411–414 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lou H., Kim S.-K., Zaitsev E., Snell C. R., Lu B., Loh Y. P., Sorting and activity-dependent secretion of BDNF require interaction of a specific motif with the sorting receptor carboxypeptidase e. Neuron 45, 245–255 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhirde A. A., Hassan S. A., Harr E., Chen X., Role of albumin in the formation and stabilization of nanoparticle aggregates in serum studied by continuous photon correlation spectroscopy and multiscale computer simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 16199–16208 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrer M. L., Duchowicz R., Carrasco B., de la Torre J. G., Acuna A. U., The conformation of serum albumin in solution: A combined phosphorescence depolarization-hydrodynamic modeling study. Biophys. J. 80, 2422–2430 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hainfeld J., Slatkin D., Focella T., Smilowitz H., Gold nanoparticles: A new x-ray contrast agent. Br. J. Radiol. 79, 248–253 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gekle M., Renal tubule albumin transport. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67, 573–594 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuda N., Lu H., Fukata Y., Noritake J., Gao H., Mukherjee S., Nemoto T., Fukata M., Poo M.-M., Differential activity-dependent secretion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor from axon and dendrite. J. Neurosci. 29, 14185–14198 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perlenfein T. J., Murphy R. M., Expression, purification, and characterization of human cystatin C monomers and oligomers. Protein Expr. Purif. 117, 35–43 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan Y. H., Liu M., Nolting B., Go J. G., Gervay-Hague J., Liu G.-Y., A nanoengineering approach for investigation and regulation of protein immobilization. ACS Nano 2, 2374–2384 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foust K. D., Nurre E., Montgomery C. L., Hernandez A., Chan C. M., Kaspar B. K., Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 59–65 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen W., Yao S., Wan J., Tian Y., Huang L., Wang S., Akter F., Wu Y., Yao Y., Zhang X., BBB-crossing adeno-associated virus vector: An excellent gene delivery tool for CNS disease treatment. J. Control. Release 333, 129–138 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McIntosh N. L., Berguig G. Y., Karim O. A., Cortesio C. L., De Angelis R., Khan A. A., Gold D., Maga J. A., Bhat V. S., Comprehensive characterization and quantification of adeno associated vectors by size exclusion chromatography and multi angle light scattering. Sci. Rep. 11, 3012 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan S., Yang P. H., DeFreitas D., Ramagiri S., Bayguinov P. O., Hacker C. D., Snyder A. Z., Wilborn J., Huang H., Koller G. M., Gold nanoparticle-enhanced X-ray microtomography of the rodent reveals region-specific cerebrospinal fluid circulation in the brain. Nat. Commun. 14, 453 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jessen N. A., Munk A. S. F., Lundgaard I., Nedergaard M., The glymphatic system: A beginner’s guide. Neurochem. Res. 40, 2583–2599 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reaux A., De Mota N., Skultetyova I., Lenkei Z., El Messari S., Gallatz K., Corvol P., Palkovits M., Llorens-Cortès C., Physiological role of a novel neuropeptide, apelin, and its receptor in the rat brain. J. Neurochem. 77, 1085–1096 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hablitz L. M., Vinitsky H. S., Sun Q., Stæger F. F., Sigurdsson B., Mortensen K. N., Lilius T. O., Nedergaard M., Increased glymphatic influx is correlated with high EEG delta power and low heart rate in mice under anesthesia. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav5447 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quincke H., Zur Physiologie der Cerebrospinalfluessigkeit. Arch. Anat. Physiol. Wiss Med. 153–177 (1872). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mestre H., Tithof J., Du T., Song W., Peng W., Sweeney A. M., Olveda G., Thomas J. H., Nedergaard M., Kelley D. H., Flow of cerebrospinal fluid is driven by arterial pulsations and is reduced in hypertension. Nat. Commun. 9, 4878 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCabe J. S., Low F. N., The subarachnoid angle: An area of transition in peripheral nerve. Anat. Rec. 164, 15–33 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boulton M., Flessner M., Armstrong D., Hay J., Johnston M., Determination of volumetric cerebrospinal fluid absorption into extracranial lymphatics in sheep. Am. J. Physiol. 274, R88–R96 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoon J.-H., Jin H., Kim H. J., Hong S. P., Yang M. J., Ahn J. H., Kim Y.-C., Seo J., Lee Y., McDonald D. M., Nasopharyngeal lymphatic plexus is a hub for cerebrospinal fluid drainage. Nature 625, 768–777 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lohela T. J., Lilius T. O., Nedergaard M., The glymphatic system: Implications for drugs for central nervous system diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 763–779 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mazzitelli J. A., Smyth L. C., Cross K. A., Dykstra T., Sun J., Du S., Mamuladze T., Smirnov I., Rustenhoven J., Kipnis J., Cerebrospinal fluid regulates skull bone marrow niches via direct access through dural channels. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 555–560 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Møllgård K., Beinlich F. R., Kusk P., Miyakoshi L. M., Delle C., Plá V., Hauglund N. L., Esmail T., Rasmussen M. K., Gomolka R. S., A mesothelium divides the subarachnoid space into functional compartments. Science 379, 84–88 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brightman M., Reese T., Junctions between intimately apposed cell membranes in the vertebrate brain. J. Cell Biol. 40, 648–677 (1969). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reese T., Karnovsky M., Fine structural localization of a blood-brain barrier to exogenous peroxidase. J. Cell Biol. 34, 207–217 (1967). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steer J. C., Horney F., Evidence for passage of cerebrospinal fluid among spinal nerves. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 98, 71–74 (1968). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quincke H., Gunn J., Abstract of a lecture on pernicious anæmia. Edinb. Med. J. 22, 1087–1098 (1877). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.L. N. Telano, S. Baker, Physiology, cerebral spinal fluid, in StatPearls [StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2024]. [PubMed]

- 50.Fraher J., The transitional zone and CNS regeneration. J. Anat. 194, 161–182 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kristensson K., Olsson Y., The perineurium as a diffusion barrier to protein tracers. Acta Neuropathol. 17, 127–138 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shanthaveerappa T., Bourne G., The perineural epithelium of sympathetic nerves and ganglia and its relation to the pia arachnoid of the central nervous system and perineural epithelium of the peripheral nervous system. Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat. 61, 742–753 (1963). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Söderfeldt B., The perineurium as a diffusion barrier to protein tracers. Acta Neuropathol. 27, 55–60 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poliak S., Peles E., The local differentiation of myelinated axons at nodes of Ranvier. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 968–980 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kadry H., Noorani B., Cucullo L., A blood–brain barrier overview on structure, function, impairment, and biomarkers of integrity. Fluids and Barriers of the CNS 17, 69 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong A. D., Ye M., Levy A. F., Rothstein J. D., Bergles D. E., Searson P. C., The blood-brain barrier: An engineering perspective. Front. Neuroeng. 6, 7 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mathiisen T. M., Lehre K. P., Danbolt N. C., Ottersen O. P., The perivascular astroglial sheath provides a complete covering of the brain microvessels: An electron microscopic 3D reconstruction. Glia 58, 1094–1103 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Myers R., Rydevik B., Heckman H., Powell H., Proximodistal gradient in endoneurial fluid pressure. Exp. Neurol. 102, 368–370 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mestre H., Mori Y., Nedergaard M., The brain’s glymphatic system: Current controversies. Trends Neurosci. 43, 458–466 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pla V., Bork P., Harnpramukkul A., Olveda G., Ladron-de-Guevara A., Giannetto M. J., Hussain R., Wang W., Kelley D. H., Hablitz L. M., A real-time in vivo clearance assay for quantification of glymphatic efflux. Cell Rep. 40, 111320 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spector R., Snodgrass S. R., Johanson C. E., A balanced view of the cerebrospinal fluid composition and functions: Focus on adult humans. Exp. Neurol. 273, 57–68 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu G., Mestre H., Sweeney A. M., Sun Q., Weikop P., Du T., Nedergaard M., Direct measurement of cerebrospinal fluid production in mice. Cell Rep. 33, 108524 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S16